Exhibitions in Print

Exhibitions in Print

Interview between Sharmini Pereira And Sneha Ragavan

Abstract

Raking Leaves was founded in 2008 in the UK as an independent, non-profit organisation with an aim to publish artist books, with an emphasis on the geopolitical and cultural contexts of South Asia. With a focus on exploring the collaborative potential of artistic practice, of thinking beyond the “art object”, Raking Leaves has consistently pushed the boundaries of how objects and ideas are disseminated, viewed, and engaged with. Some of its publications include, The One Year Drawing Project: May 2005–October 2007 by Muhanned Cader et al. (2008; Pearls by Simryn Gill (2008); Name, Class, Subject by Aisha Khalid (2010); Side by Side by Imran Qureshi (2010); The Incomplete Thombu by T. Shanaathanan (2012); The Speech Writer by Bani Abidi (2012); and the recently published The A–Z of Conflict (2019). The founder and director of Raking Leaves, Sharmini Pereira looks back at her engagement with the artist book as a form, the conditions and contexts of the founding of Raking Leaves in the UK, and its relationship with contemporary cultural and political ecologies, in the following interview with Sneha Ragavan.

Interview

Sneha: What were the specific conditions and contexts that led to the founding of Raking Leaves as an organisation in the UK in 2008?

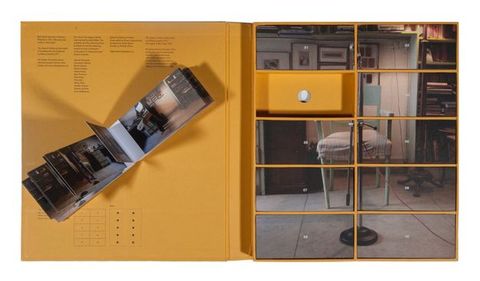

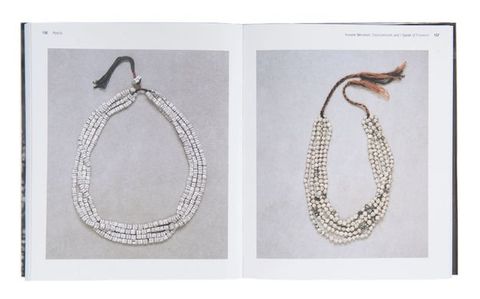

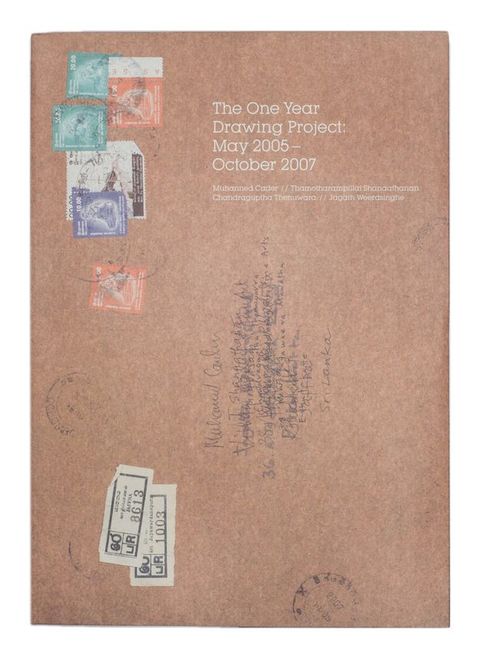

Sharmini: While I was co-curating the first Singapore Biennale in September 2006, I mooted the idea about commissioning art projects in the form of books with artists like Simryn Gill, Bani Abidi, Jagath Weerasinghe, Muhanned Cader and Shahidul Alam, all of whom I was working with at the time. Raking Leaves was borne out of these conversations and a belief that curated books could provide a way for raising awareness about artists living outside of Europe and the USA that did not rely on exhibitions. I invited Simryn Gill to create one of the first book projects because I admired the way she thought about the circulation of ideas through objects (fig. 1). Alongside Gill’s artist’s book, I also had the idea for The One Year Drawing Project and of working with Muhanned Cader, Chandraguptha Thenuwara, T. Shanaathanan and Jagath Weerasinghe on a drawing exchange, which was conceived as a challenge to the workshop-orientated art projects that proliferated in Sri Lanka at the time, in response to funding and discussions about peace and reconciliation (fig. 2). Our first meeting took place in Colombo at Muhanned’s house in 2005. Shanaathanan managed to join us, despite the fact that travel between Jaffna and Colombo was subject to security restrictions. I recall saying goodbye to him with a sense of trepidation as he stepped back into a reality that few of us had any idea about. On reflection, the context of the war in Sri Lanka has thrown a long shadow of influence over Raking Leaves.

In contrast to curatorial work, I had also done more work in the publishing industry working as an editor at a number of different small- and large-scale publishers. I was a trustee of the BookWorks in the UK. So, in many ways, my relationship with the printed form was much more developed compared to that of exhibitions. A trip to the Frankfurt Book Fair in 2005 however made it plain to me that this was an industry dominated by European men—and to be a publisher was not just about having ideas but bank rolling them too. Fortunately, for me, the Prince Claus Fund for Culture came on board as the first funder. And much to my surprise, prior to the launch of Raking Leaves in March 2008, an unexpected telephone call from the Arts Council England (ACE) confirming they wanted to fund Raking Leaves for a three-year period giving me the financial incubation I required. That same year, however, Lehman Brothers went into receivership ushering in a global downturn. Ten years on, while circumstances have changed, securing financial support for more experimental forms of art-making and the context of conflict continues to impact the work many of us are still engaged with.

Sneha: How, if at all, have the changing geopolitical contexts of its shift of base to Sri Lanka affected the mission of Raking Leaves?

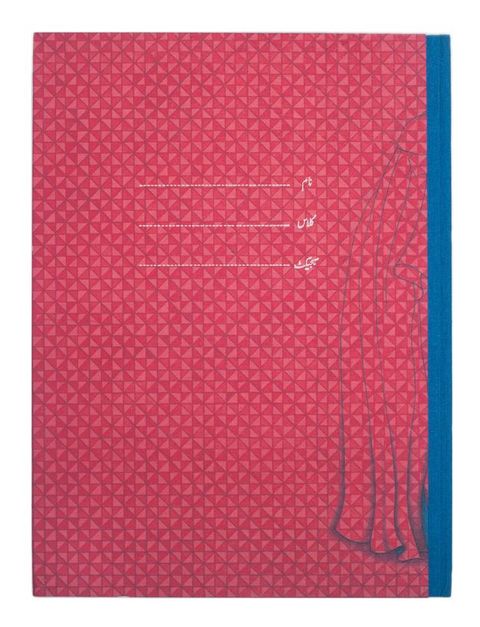

Sharmini: Thanks to ACE funding, I was able to shore up Raking Leaves’ organisational structure and deliver a publishing programme that includes much talked about projects such as The Speech Writer by Bani Abidi (fig. 3), Side by Side by Imran Qureshi, and the award-winning Name Class Subject by Aisha Khalid (fig. 4). In 2010–2011, however, I decided to relocate to Sri Lanka, from where I had been coming and going for over 15 years. While the move required looking for an alternative funding source, it also allowed Raking Leaves to follow its founding mission, which was simply to commission and publish artists’ books. My interest from the start was never to set up an arts organisation which would grow over the years, employing more people and delivering an education programme, etc. This was the type of arts organisation favoured by ACE but not a model particularly suited to publication-based curating. Though my decision was sad, it was absolute and with the move to Sri Lanka, Raking Leaves made it possible, for example, to set up—with T. Shanaathanan and P. Ahilan—the Sri Lanka Archive of Contemporary Art, Architecture and Design in Jaffna, which has been running for over six years. The public benefit and learning opportunities generated by SL Archive over the years is incomparable to the impact of any of Raking Leaves’ publishing projects. Sometimes one’s mission grows as a response to something rather than as a set of objectives that are measurable and quantifiable.

Sneha: Given that Raking Leaves primarily works with the artists’ book, which is, as you have identified, a minor form, where do you locate its role and function in contemporary contexts of art publishing, exhibiting, and viewing?

Sharmini: Prior to setting up Raking Leaves, I was a recipient of grant funding in the UK from ACE. All the funds I received were awarded on the basis of my ethnicity, where my work was counted in statistical terms as secondary. I was categorised as Black Minority Ethnic (BME), a term that conflates and confounds identities of marginalisation in relation to what is construed as the norm—to be white. As pressing as it is to find ways to address inequality, being tagged by a system of subjugation does not allow professionally qualified individuals to compete in an already competitive playing field. Speaking at the Paul Mellon Centre’s conference in 2016, I asked what are the differences between organisations that are supported by RFO funding compared to organisations that are borne out of specific cultural diversity initiatives?1 Projects like Organisation for Visual Arts (OVA), INiVA, Rich Mix, Autograph, for example? Is the perceived difference between such organisations healthy or harmful? Are organisations borne out of cultural diversity initiatives in effect widening the gap between the centre and the periphery? What in turn is being constructed, at an organisational level with regard to certain kinds of narratives? If some professionals are marginalised as different, why can’t the same be said of art forms, the artist’s book being one such example? The conceit of seeing it as such was what I wished to raise in analogy to arts funding in the UK.

1Sneha: What has been Raking Leaves’ relationship to the art market as a site for circulation and sales of your publications? Could you share any instances where it proved to be advantageous, and vice versa, some challenges you encountered.

Sharmini: Art fairs have often included “publishing” sections but these have tended to be restricted to publishers of art journals. The adverts in such journals have always had close ties for the commercial gallery sector, so it’s not surprising to see art fairs accommodating them. Over the last few years, however, the art market has seen the rise of fairs specialising in artist’s books. Printed Matter’s New York Artist Book Fair has led the way on this front and is the biggest. What’s been interesting to see is how places like Sharjah, Singapore, and Hong Kong initiate their own art book fairs. Participating in such events has been hugely beneficial to Raking Leaves in helping to establish a place for artist-led critical publishing projects within an arena that caters to the market. Many museums, mostly in the USA, have turned their attention to acquiring artist books for their collections, recognising the form as something curators, writers, and artists are using to produce work, and therefore something they wish to collect. Alongside the standard editions, Raking Leaves has always produced collector’s editions too. I am seeing collecting institutions buy and collect both. In some cases, institutions and collectors have wanted to buy the original works that were made to create the artist’s books, and more recently, there has been interest in buying materials related to the production process too, such as make ready print sheets and printing proofs.

Sneha: Could you discuss why the concept of “movement” holds significance to the work of Raking Leaves? For instance, one sees movement in, among other aspects, the fact of its publication of books by artists from Asia, while Raking Leaves itself was located in the UK; its shift of base to Sri Lanka; the travelling of the artist books themselves, and more.

Sharmini: When I set up Raking Leaves, I wanted to embrace an art form that lent itself to dissemination, in the way that seeds can be dispersed by the wind, birds, insects etc. Where, in effect, the circulation of an object, in this case a book, was subject to modes of dissemination and reception that were indifferent to the orthodox distribution channels of culture found in exhibitions, art fairs, biennales etc. I’m aware of the inherent idealism in saying this but I think it’s always important to know what you are pushing against and why. I grew up surrounded by books not exhibitions, which were unfamiliar spaces. I therefore came to associate the movement of information and ideas more with the printed form. Copies of the National Geographic with their full bleed, glossy photo-journalist images provided me with my first taste of a world out there. As a child, I also had a copy of a Good News Bible that I treasured because of the tissue-like paper of the pages. As I started to travel and stay in hotels, I was perplexed to find copies of the Bible in the drawer of the bedside table. I have always been tempted to do a project where all Bibles in all hotel rooms would be replaced with Raking Leaves books.

Sneha: There seems to be a consistent effort through your work to complicate the concepts of both region and nation. For instance, you have on previous occasions spoken about South Asia as a fraught category, particularly in the context of the art world and the Indianisation of the region. Could you elaborate?

Sharmini: The category of “South Asia” is a relational term that has been used by many exhibition makers, arts funders, and institutions as a way of focusing on a geographic grouping of countries that excludes seeing them in relation to historic, economic, social, and legal determinants. On a global scale, India occupies one of the largest landmasses in the world, warranting attention on the basis of scale and population alone. Its scale has, however, had the side effect of eclipsing attention from neighbouring countries to the extent that the idea of India has become synonymous with the idea of South Asia, excluding countries such as Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, and Pakistan, who each have complex histories of art that necessitate being looked at on their own terms. The Indianisation of the region cannot be ignored but it can also be countered over time as art worlds, markets, artists, scholars, and exhibitions in the region offer accounts that are not India-centric. I have recently been reading a brilliant exchange between Stuart Hall and David Scott in BOMB Magazine (2005) about the future of critical enquiry. Talking about Scott’s work, Hall says, “in his new book, Conscripts of Modernity, [Scott] proposes not that we give better answers to the old questions, but that the questions themselves are no longer relevant—because they belong to a different ‘problem space’ and need to be radically refashioned.” The category of “South Asia”, in Scott’s terms, can be seen as a “problem space” of a particular point in history and within a particular geopolitical understanding of the region. What we need to do today is ask different questions so that we can overcome the Indianisation that has dominated the region.

Sneha: Language—be it as a site of the operation of power, or of fostering communities and milieus—has been a crucial site of address for several of Raking Leaves’ projects, and in particular the forthcoming book The A–Z of Conflict. Could you say more about why language and translation are such crucial sites of enquiry?

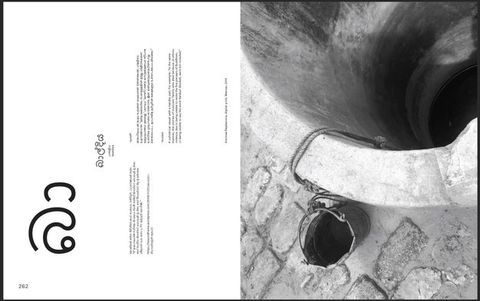

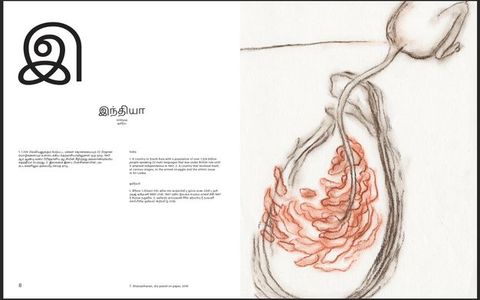

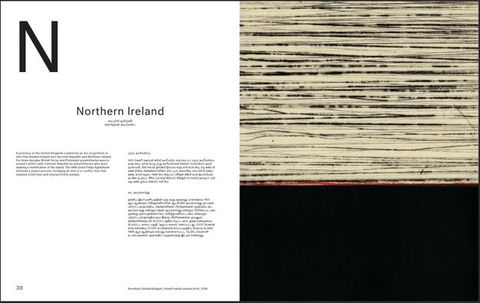

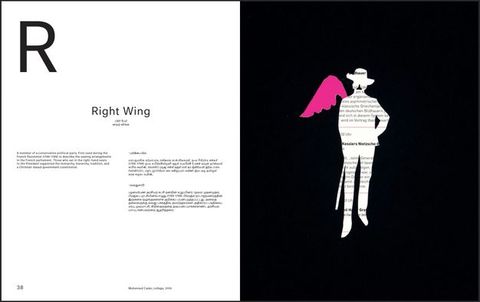

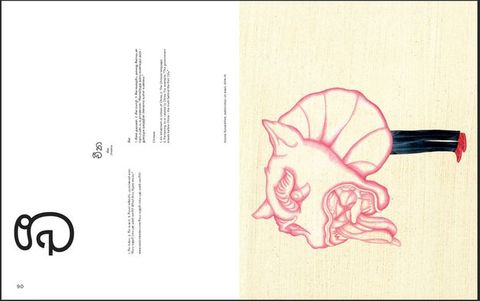

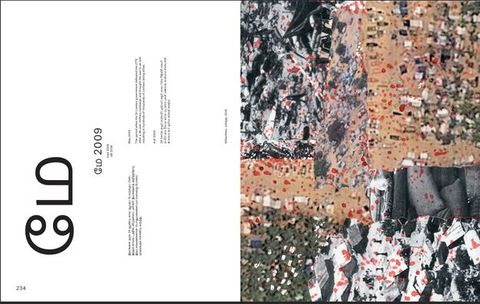

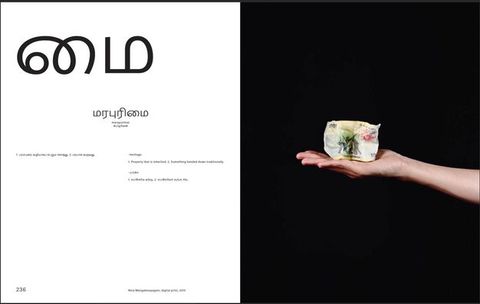

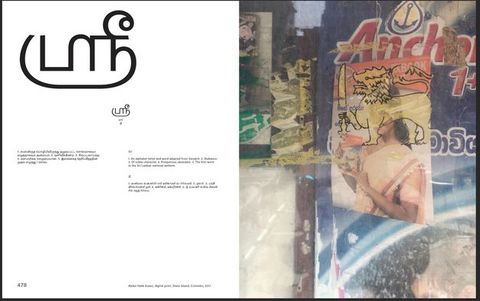

Sharmini: The A–Z of Conflict is the first tri-lingual artist’s book to be published by Raking Leaves (Figs. 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, and 12). The premise of the project set out to explore the extent to which new words had been borne out of conflict or if existing words gained new meanings. Using the format of a children’s ABC book, which juxtaposes letters, words, and images the project has taken five years to create, compile, and edit. In its final form, it is the largest project to date in terms of volume and number of artists. Over 1,000 new artworks were specially commissioned from ten artists: Abdul Halik Azeez, Muhanned Cader, Arjuna Gunarathne, Nina Mangalanayagam, Nillanthan, Anomaa Rajakaruna, T. Shanaathanan, Anushiya Sundaralingam, Chandraguptha Thenuwara, and Kamala Vasuki. A team of 23 editors and translators were also involved plus a designer and an extremely patient printer. What defines the project are the three languages spoken in Sri Lanka: English, Sinhala, and Tamil. The history of conflict in Sri Lanka has been the subject of many important books, plays, films, and art works over the years but few have addressed the role language has played. The A–Z of Conflict, in spite of its size and scale, only starts to scratch the surface about a subject that has contributed on so many levels to where the country finds itself today.

Sneha: How do curated publications or artist books challenge how we think about exhibition practices?

Sharmini: They tend to confound many curators because exhibiting a book-based work has traditionally been something that is seen in a vitrine with an acrylic bonnet over it. The audience cannot touch it, or turn the pages, unlike in a bookshop, where in most cases, these objects have also existed. Tethering books to tables is also another common way to encounter publications within an exhibition space. Ironically, this is how illuminated manuscripts in Europe were dealt with, when literacy did not exist among the masses and those who could read occupied a position of authority and power over the audience, who were there to listen, usually to the contents of a sermon. Tethering books to tables has, thus, always reminded me of the proselytising role books have played historically. Many good exhibition histories however do start to unpack so much important information and I hope in time, there will be people who start to do the same with artists’ books where they start to consider the collaborative nature of the productions, the design decisions, the curatorial motivations, and the funding involved."

About the authors

-

Sharmini Pereira is director and founder of Raking Leaves and co-founder of The Sri Lanka Archive of Contemporary Art, Architecture, and Design. She lives and works in Sri Lanka.

-

Sneha Ragavan is senior researcher and projects lead at Asia Art Archive in India (AAAI), based in New Delhi. She conceptualizes and leads AAAI’s research initiatives on modern and contemporary art, including projects digitizing artists’ archives and creating digital bibliographies of art across multiple languages, and has co-organized seminars and workshops around archiving and educational resources.

Footnotes

-

1

The conference was “Showing, Telling, Seeing: Exhibiting South Asia in Britain, 1900–Now”, held on 30 June–1 July, 2016, at the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, London, https://www.paul-mellon-centre.ac.uk/whats-on/past/showing-telling-seeing-conference. ↩︎

Imprint

| Author | |

|---|---|

| Date | 30 September 2019 |

| Category | Interview |

| Review status | Peer Reviewed (Editorial Group) |

| License | Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) |

| Downloads | PDF format |

| Article DOI | https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-13/pereira-ragavan |

| Cite as | Pereira, Sharmini, and Sneha Ragavan. “Exhibitions in Print.” In British Art Studies: London, Asia, Exhibitions, Histories (Edited by Hammad Nasar and Sarah Victoria Turner). London and New Haven: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art and Yale University Press, 2019. https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-13/pereira-ragavan. |