Do Not Tape Over

Do Not Tape Over: AIDS Activist Videos in the United Kingdom

By Ed Webb-Ingall

Abstract

This article presents a selection of AIDS activist videos to explore the impact of HIV/AIDS on activist methods and artistic production in Britain in the 1980s and early 1990s. It attempts to redress a gap in the history of moving-image production and distribution in the United Kingdom by those who were impacted by HIV/AIDS. It shows that AIDS activist videos employed a multiplicity of approaches to production and distribution, each responding to a specific context or subject position. It explores how such films were made in the context of failures of representation, and an absence of self-expression, in mainstream media; and identifies key differences between AIDS activist production and distribution in the United Kingdom and the United States.

Introduction

This article presents, in chronological order, a selection of AIDS activist videos. It attempts to redress a gap in the history of moving-image production and distribution in the United Kingdom by those who were impacted by HIV/AIDS. The earliest video included here was produced in 1983 and the latest in 1993, after which the evolution of the World Wide Web began to change distribution methods. This special issue of British Art Studies is an opportunity to explore the impact of HIV/AIDS on activist methods and artistic production in Britain in the 1980s and early 1990s.

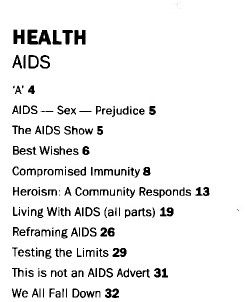

My research began when I noticed a listing in a distribution catalogue published by the community video group Albany Video in 1988, which offered a directory of videos for hire made by community, activist, and campaign groups (fig. 1). The index to the catalogue lists eleven videos under the heading “Health, AIDS”, six of which had been made by artists and community groups in the United Kingdom and five of which had originated in the United States (fig. 2). Following funding cuts, Albany Video had closed its doors by the early 1990s and most of the British videos went out of circulation.1 The precarity of this material was exacerbated by the fact that video as a medium was hard to preserve and take care of. How video was being used at the time by the groups who appear in the catalogue eluded clear classification. Much of it sat between artist or experimental video on the one hand and documentary or activist video on the other, which meant that it struggled to find a home in an archive or institution. Furthermore, the lives of many of those involved in the production of these videos became increasingly vulnerable as a result of their homophobic and life-threatening treatment from mainstream media outlets and the state.

1Before I started looking into the production and distribution of AIDS activist videos in the United Kingdom, I had envisaged footage of mass protests and kiss-ins in public spaces by lesbian and gay groups. The videos I had in mind shared an aesthetic with the wider community and activist video movement that had preceded it. These videos were characterised by shaky hand-held, low-fi and grainy colour images and were recorded from the activist’s perspective, with the camera moving with the cameraperson, often pulled and pushed around by the crowds of which they were part. I imagined such scenes being cut together with interviews with small groups of people in domestic spaces and meeting halls and on street corners, reflecting on their personal experiences with doctors, the police, family members, lovers, colleagues, and so on.2 However, after some preliminary research in archives, discussions with others researching AIDS activism, and correspondence with activists who were there at the time, it became clear that I was recalling footage that had originated in the United States, specifically in New York City. The question then arose: If the AIDS activist videos I had expected were made in the United States, what was going on in the United Kingdom at the same time?

2The British Film Institute (BFI) Mediateque in London currently has 111 videos in its curated selection on HIV and AIDS, predominantly drawn from the BFI National Archive’s broadcast television collections and including current affairs programmes, health campaign films, documentaries, dramas, and artists’ film and video work. None can be classified strictly as independent productions. Twelve are public health videos or public information films. Nine can be classified as alternative productions made by artists and activists from within the community of those impacted by HIV/AIDS. In comparison, the New York Public Library holds the largest collection of AIDS activist videos in the world, with over 600 tapes. This archival project was initiated by the AIDS activist and film-maker Jim Hubbard in the late 1990s, who collected over 2,000 hours of completed works and video footage, most of which was from film-makers in New York City. Reflecting on the archival material he helped collect for the New York Public Library, Hubbard explains how the tapes portray people with AIDS as “neither victims nor pariahs, but as empowered activists taking charge of their health in both the political and medical arenas”. He goes on to note that, while this is not the whole story, “it served as a necessary counterpoint to the relentlessly negative depictions by the mainstream media”.3

3In my correspondence with the United Kingdom-based activist and writer Simon Watney, he explained how the profiles of AIDS activism in the United States and the United Kingdom were radically different because the scale of, and approach to, the epidemic was so different in each country.4 American activism was responding largely to a situation resulting from the absence of socialised medicine and focused on treatment issues, whereas what predominated in the United Kingdom was “prevention activism” and the provision of a corrective to media representations of people with AIDS. Watney’s distinction makes it clear that, while experiences of HIV and AIDS on both sides of the Atlantic share commonalities, AIDS activist videos also needed to respond to the specific context in which they were produced and seen. Similarly, the video artist and writer Stuart Marshall, who made one of the first AIDS activist videos in the world (Kaposi Sarcoma, 1983), drew attention to an important difference in the distribution and exhibition of videos between North America and the United Kingdom and how this impacted the way in which he made and shared videos.5

4In contrast to the networked local cable TV stations in Canada and the United States, there were few options in the United Kingdom for independent producers to access broadcast television. Because of this, Marshall drew on his experience as part of the grassroots video art organisation London Video Arts, through which he programmed informal screenings of artist videos in London outside of traditional arts organisations, to find similarly receptive audiences in gay clubs. Thse ad hoc screening opportunities interested him much more than television because they allowed him to speak to a very specific group about specific interests. He understood that making videos for broadcast television always meant going along with the ideology of the broadcaster and that what was considered gay programming wasn’t actually made for gay people but instead was about them. This voyeuristic and extractive approach, along with the structure of mainstream broadcasting, worked against the possibility of minority groups ever seeing positive images of themselves. Instead, as Marshall states, “As far as I’m concerned, the way that AIDS has been represented by the media is nothing more than a sophisticated form of queer bashing”.6

6The mainstream media’s negative depiction and life-threatening treatment of people with AIDS underscored the need for artists and activists from within the community of those most impacted by HIV and AIDS to create alternative images. For them, this effort was as much about developing modes of self-representation as it was about education and activism. Activists, artists, and campaigners were motivated to produce alternative images of HIV and AIDS so that those experiencing its impact were not simply understood through their illness but, as the feminist writer and theorist of media production Alexandra Juhasz describes it, “as people living with AIDS not dying of AIDS”.7

7The American activist and writer Douglas Crimp wrote about the specific role of video in AIDS activism in the United States in his introductory essay to “AIDS: Cultural Analysis / Cultural Activism”, a special issue of the journal October, in 1987:

8To date, a majority of cultural producers working in the struggle against AIDS have used the video medium. There are a number of explanations for this: Much of the dominant discourse on AIDS has been conveyed through television, and this discourse has generated a critical counter-practice in the same medium; video can sustain a fairly complex array of information; and cable access and the widespread use of VCRs provide the potential of a large audience for this work.8

The video camcorder arrived on the scene at the same time as the HIV/AIDS epidemic. This new technology increased accessibility and allowed for new forms of representation; it was easy to use and democratised video production among not just tech-enthusiasts but also ordinary people. The VHS system was invented by JVC, who in 1984 used their existing VHS-C (compact cassette) system to produce a VHSC camcorder, the first camcorder using the VHS system. This made the production and distribution of videos more straightforward. The VHS-C tapes used the same type of tape as VHS but were shorter (usually 30 to 60 minutes) and contained in a smaller cassette. Prior to this, video recording and playback technology was either low in quality or large and expensive, quite often both. Access to the new video cameras encouraged groups and individuals to create a counter-narrative and alternative to broadcast media. In the words of the film-maker Ellen Spiro in her “Camcorderist’s Manifesto” (1991):

With reference to the urgency of video-making at the time and to future activism and storytelling, the scholar Roger Hallas summarises the three functions of using camcorders for AIDS activism:

- To produce their own news service that could distribute coverage of actions within activist communities and to progressive independent media outlets

- To generate their own archive so that communities affected by the epidemic would not need to rely on commercial news services to write their own history in the future

- To serve as a video witness whose presence might guard against any police misconduct.10

It is clear from the examples I have found that AIDS activist videos made in the United Kingdom employed a multiplicity of approaches to production and distribution, each responding to a specific context or subject position. As Hallas argues, the videos are:

11neither mere ideological critiques of the dominant media representation of the epidemic nor corrective attempts to produce positive images of people living with HIV/AIDS: Rather, I contend, that their significance lies in their ability to bear witness to the simultaneously individual and collective trauma of AIDS.11

The urge to produce and distribute videos that represent the myriad experiences of people with AIDS in the United Kingdom was largely motivated by failures of representation in mainstream media. These AIDS activist video projects are indebted to a history of cultural production that insisted on what Juhasz describes as “the vital significance of self-expression, the politics of self-definition, [and] the power of speaking ‘in our own voice’”.12

12My search began. Using the Albany Video catalogue index as a starting point, I was able to locate three of the videos included in their original listing and subsequently expanded my search to include other similar AIDS activist videos produced around the time of the catalogue’s publication.13 Rather than offer an exhaustive selection, the list that follows includes a collection of videos I was able to access as part of my research, as well as an attempt to bring together different approaches to AIDS activist video production in the United Kingdom.

13Kaposi’s Sarcoma (A Plague and Its Symptoms) (1983)

Kaposi’s Sarcoma (A Plague and Its Symptoms), directed by Stuart Marshall, is about how AIDS was beginning to be represented by mainstream media at the time, in particular medical journalism, and how this portrayal sought to, in Marshall’s words, “destroy the work of gay liberation that had come before, transforming the homoerotic body into a pathologised and morbid body” (fig. 3).14 The video is the earliest record of the production of an AIDS activist video anywhere in the world.

14Marshall went on to produce two other AIDS activist works. Indicating the changing media landscape, they were made for and broadcast on Channel 4: Bright Eyes (1984), a programme described as “one of the first documentary works of AIDS cultural activism”, and Over Our Dead Bodies (1991), which documents and explores the origins of the AIDS activist movement in New York, San Francisco, and London and the exchanges that took place between these cities.15

15

“‘A Plague on You’: AIDS, the Media and the Truth” (1985)

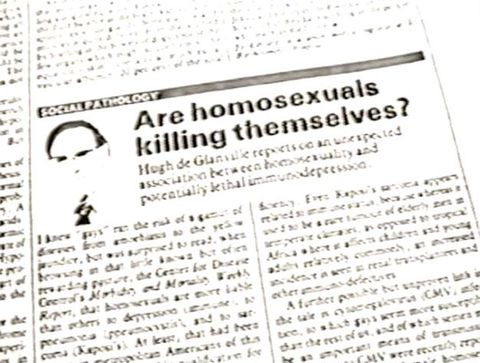

Produced by the Lesbian and Gay Media Group as part of the Open Space strand on BBC2, “‘A Plague on You’” was intended as a corrective to the homophobic broadcasting of the time (fig. 4).16 The Open Space television series supported different community groups in making programmes on specific social issues or concerns. Importantly, these productions were made from within and by the impacted community, with the BBC offering production and technical support.

16The idea for this programme began at an open meeting in April 1985 organised by the Campaign for Homosexual Equality (CHE) and the Labour Campaign for Lesbian and Gay Rights (LCLGR). At the meeting, which was called “to plan a response to the twin medical and political threats posed by the disease of AIDS”, the Lesbian and Gay Media Group was formed.17 The group, which included Stuart Marshall, began to organise its own meetings and it was at one of these that the suggestion to contact BBC Open Space was made. When their application was subsequently accepted, an open meeting, advertised in Capital Gay, was then held at the Fallen Angel pub in Islington, London, at which ideas for a programme began to emerge. Some broad aims were established to, in their words, “expose the lies and distortions of the media, and to show the effect this was having on lesbians and gay men and all people concerned with AIDS”.18

17The programme consists of a series of talking-head interviews with experts from within the community of those impacted by HIV/AIDS, including lesbians, gay men, and health and employment professionals, who explain the impact of various misconceptions of AIDS propagated by mainstream media. The programme attempts to demystify AIDS and provide a corrective to harmful beliefs about it. For example, it explains how AIDS is a transmissible disease rather than a contagious one, and that it is not a “gay plague”.

Through the first-hand experiences of lesbians and gay men, it describes the harmful impact mainstream media is having on their relationships, employment, and physical and mental health. This is intercut with interviews with several Fleet Street journalists, rostrum footage of dramatic newspaper headlines, and excerpts from news stories and panel shows, all of which focus on homophobia in the mainstream press and television. The group summarises the outcomes it hoped the project would achieve:

Reframing AIDS (1987)

Reframing AIDS, directed by Pratibha Parmar, consists of interviews with cultural critics, activists, and media commentators largely from the global majority, as well as with Stuart Marshall, Sue O’Sullivan, and Simon Watney (fig. 5). This video continues the project set out by the Lesbian and Gay Media Group to move the discussion of HIV and AIDS away from the conservative and bigoted positions seen on television and in the press to the personal lived experiences, feelings, and activities of lesbians and gay men speaking openly about how they have been affected and how they are challenging dominant perceptions of AIDS. Parmar summarised her hopes to humanise and highlight the intersecting experiences of those impacted by HIV and AIDS in this video project as follows:

This video project draws parallels between the response to those with HIV/AIDS and prejudice based on racial and social differences. Reframing AIDS is evidence of how the multiplicity of approaches to AIDS activist video gave rise to myriad strategies, created important opportunities, and opened up spaces for communities whose experiences and needs both intersected and differed. As Marshall reflected in his 1991 analysis of approaches to AIDS activism and the production of AIDS activist videos:

This Is Not an AIDS Advertisement (1987)

Made by the video artist Isaac Julien, This Is Not an AIDS Advertisement is a short impressionistic video that plays with the form of a music video (fig. 6).22 It consists of video-manipulated Super 8 sequences, largely of the Grand Canal in Venice and of Julien with his lover. Julien was working at the time as part of the Black workshop Sankofa Film and Video Collective and made the video to centre and celebrate sensuality and sexuality in the face of moralising and puritanical views about homosexuality and AIDS. Bright pink words fill the screen with the title of the video, while the pulsing soundtrack demands that the audience “feel no guilt in your desire”.

22In the spirit of collaboration and activism, photos by Sunil Gupta feature in the video, along with music provided by members of the queer pop group Bronski Beat. Excerpts of this film feature in Parmar’s video Reframing AIDS.

Artists’ production of AIDS activist videos reflects the blurred line between the work of artists and of activist groups at the time. As Tom Folland notes in his writing on AIDS activist video:

23The seemingly opposed agencies of video art and video activism appear to be united when it comes to one political issue: putting an end to the AIDS crisis. While continually less money is being allotted for the research and development of hundreds of promising drugs, gay and AIDS communities have been utilizing video to counsel and promote safer sex, educate, empower and mobilize people.23

Compromised Immunity (1987)

Compromised Immunity, directed by Phillip Timmins, is a video adaptation of a play of the same name by Andy Kirby, which was produced by the Gay Sweatshop as part of the Gay Times Festival in 1986 (fig. 7). It was one of the videos distributed by Albany Video, who also distributed other videos made by under-represented groups using theatre and performance to mediate and explore the representation of their experiences. Rather than directly recording the play, Timmins took advantage of video’s mobility to record on location in a hospital and on the streets of London. He also made use of freeze-frame video techniques, flashbacks, and montage. The video tells the story of Peter Dennett, a heterosexual hospital nurse and Jerry Grimond, who is gay, has AIDS, and has lost his job, home, and lover. Jerry has been given two months to live when he is transferred to the isolation ward of Peter’s hospital, appears outwardly hostile, and is deemed “difficult” by hospital staff. With contrasting prejudices and assumptions about sexuality, AIDS, and each other, the patient and nurse relationship is at first tense and terse. But gradually, through Peter's caring efforts, Jerry’s disillusion and loneliness lessen during his last weeks and a greater understanding grows between them.

The motivation to make a record of the play was that video provided a tangible and less transient mode of representation than theatre. There was an urgency at the time to make a lasting record of the experiences of people whose lives were being treated as expendable. Timmins recalls in an interview how he wanted to redress the balance of representation by looking at the emotional lives of different people who came into contact with AIDS.24

24OUTRAGE! (1991–93)

The film-maker and OUTRAGE! member Mark Harriott began using the newly available portable video technology to document the actions of OUTRAGE!, a British LGBT rights group formed in 1990 that described itself as “a broad-based group of queers committed to radical, non-violent direct action and civil disobedience” (fig. 8).25 In my recent conversation with him, Harriott explained how the work and struggles of OUTRAGE! were largely ignored or misrepresented by the mainstream media. At their early meetings OUTRAGE! members, who knew he had access to a video camera, encouraged him to document their demonstrations, which were taking place almost every week. Harriott recalls one caucus called WIG (“Work It Girl”), which focused on queer visibility in London. The resulting footage is made up of members of OUTRAGE! in drag strutting around London and going into clothing shops asking shopworkers what they thought of drag queens and gender-nonconforming fashion.26

25Footage of the actions captured by Harriott is similar to that of the similar direct-action group ACT UP. Both groups used theatrics to create media spectacles and eye-catching slogans on placards, as well as costumes and large props to make visual statements. Where they differ is that much of the action Harriott recorded is not directly related to AIDS activism but instead focuses on the broader homophobic mistreatment of the lesbian and gay community. This included activities demanding equalisation of the age of consent, the Stop Murder Music campaign against homophobic language in popular dance-hall songs at the time, and protests at the Metropolitan Police’s entrapment of gay men cruising. Mirroring the die-ins seen around the same time, one clip shows protestors lying across a street to stop traffic, arms linked and banners draped over their bodies while others have placards hung around their necks with string. The camera pans across the scene and the frame becomes filled with a police van pulling up. Harriott keeps the camera rolling as he runs with it, moving between different parts of the action. There is a break in the footage, and the next shot shows protestors, arms held behind their backs, being dragged off and loaded into the back of the police van.

The hand-held camcorder footage of OUTRAGE! remains a rare document of the wider social and political context of the fight for lesbian and gay rights during the early years of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Harriott used the video camera to make alternative images of out, proud, and loud lesbians and gay men: The use of camcorders to bear witness was both new and urgent. Juhasz describes this kind of video production as “fighting through video”.27 Hallas reinforces the mimetic properties of these direct-action videos, showing how the bodies of those in front of and behind the camera become implicated in such a way as to remind the viewer of both their strength and their vulnerability:

2728Positioned in the centre of the circle of activists, the camera spins around to catch each new voice that enters the deliberation. The momentum to act is viscerally felt through the embodied immediacy of the camera at that moment … such activism reminds us of the profoundly somatic dimension to bearing witness in which bodily presence has the capacity to produce the kind of extra discursive excess that constitutes the affective and ethical dimensions of magnitude.28

Mouthing Off: Women Speak Out about Safer Sex (1991)

The production of Mouthing Off, made by the Leeds AIDS Advice Group, reflects how AIDS activist videos in the United Kingdom continued to draw on similar production and distribution methods as the community videos that had preceded them (fig. 9). This video was made by and for women impacted by HIV and AIDS and uses collective production to engage in discussion about the different experiences and feelings of the participants, in a way that is reminiscent of feminist consciousness groups in the 1970s. The video is organised around a series of conversations between women sitting in circles in domestic contexts, reflecting on their different experiences and understandings of safer-sex practices. The women, who come from various backgrounds, support one another to explore their individual subject positions. These conversations are intercut with vox pops from the streets, passers-by talking about their understanding of safer-sex practices. Although the video was funded by a local health organisation, it does not give direct didactic information and advice from authority figures: There is no single expert and everyone is treated equally. Its focus on the experiences of women, a group impacted by HIV and AIDS that received less attention in the media, is typical of community video projects and their concern for marginalised groups.29

29

Cock Crazy or Scared Stiff (1992)

Safer-sex tapes made by artists and activists in the early 1990s sought to re-sexualise gay men by redefining sexual acts and sexual pleasure. An example of this tendency was Sunil Gupta’s film Cock Crazy or Scared Stiff (fig. 10). The video shows two young men flirting with each other in a playful and candid back and forth as they discuss and demonstrate how to use condoms and explore safer-sex practices. Through close-ups of their faces and hands we become part of the action. We sit between them on kitchen worktops and splash around with them in the bath. It was filmed with friends in a flat in Brixton, where Gupta lived in the early 1990s.

Gupta has since explained that the finished film was the outcome of an invitation to film cutaways for a longer video about safer sex, funded by the Health Education Authority.30 He went on to describe how the original script had been very wooden, so the cast and crew worked together to adapt it according to their own experiences. While it was shot on Super 8, the commissioners took advantage of video’s capacity for being easily reproduced and distributed, and the finished project was transferred to VHS. Its do-it-yourself aesthetic and hybrid form make it part of this selection of AIDS activist videos produced in the United Kingdom.31 A community of those impacted by AIDS coming together to collaborate on a video is a beautiful example of alternative moving-image works that engage with AIDS—one that exemplifies the intersection of art, education, and activism.32

30About the author

-

Ed Webb-Ingall is a filmmaker and researcher working with archival materials and methodologies drawn from community video. He is a co-founder and project director of the London Community Video Archive and is currently writing a book with the title BFI Screen Stories: The Story of British Video Activism. Previous solo exhibitions include Three Rivers (2025), Peer (2024), Grand Union (2023), Devonshire Collective (2023), South London Gallery (2019), and Focal Point (2018). Group exhibitions include Brent Biennial (2022), MK Gallery (2019), and Invisible Dust (2019). He is a senior lecturer at London College of Communication, University of the Arts London.

Footnotes

-

1

After the Channel 4 / Workshop Franchise funding was withdrawn in the late 1980s, Albany Video continued to make productions for clients and to keep the access workshop open for as long as possible. By 1990 its production arm had closed, leaving only its distribution work, which struggled on for a couple of years in Battersea Studios. Many of the original videos were lost in the move to Battersea. ↩︎

-

2

My impression drew on the aesthetics of similar community-led activist videos produced by community and activist groups at the time. See the London Community Video Archive at https://www.the-lcva.co.uk for examples. ↩︎

-

3

Jim Hubbard, “AIDS Activist Video and the Evolution of the Archive”, 1 February 2018, https://www.jimhubbardfilms.com/writing/aids-activist-video-and-the-evolution-of-the-archive. ↩︎

-

4

Author’s email correspondence with Simon Watney, September 2019. ↩︎

-

5

Stuart Marshall interviewed on Gayblevision, “Gay T.V. in England”, episode 37, aired 4 and 18 July 1983, 29:49, Gayblevision Fonds, Christa Dahl Media Library & Archive, VIVO Media Arts Centre, https://vimeo.com/groups/461954/videos/163477144. This video, thought to be lost, was rediscovered in 2024 by the writer and artist Conal McStravick. ↩︎

-

6

Stuart Marshall interviewed on Gayblevision. ↩︎

-

7

Alexandra Juhasz, AIDS TV: Identity, Community, and Alternative Video (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1995), 46. ↩︎

-

8

Douglas Crimp, Introduction to “AIDS: Cultural Analysis / Cultural Activism”, special issue. October 43 (1987): 14, DOI:10.2307/3397562. ↩︎

-

9

Ellen Spiro, “What to Wear on Your Video Activist Outing (Because the Whole World Is Watching): A Camcordist’s Manifesto”, Independent, May 1991, 22. ↩︎

-

10

Roger Hallas, Reframing Bodies: AIDS, Bearing Witness, and the Queer Moving Image (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2009), 87. ↩︎

-

11

Hallas, Reframing Bodies, 87. ↩︎

-

12

Juhasz, AIDS TV, 33. ↩︎

-

13

The three listed in the Albany Video catalogue were Reframing AIDS (1987), This Is Not an AIDS Advertisement (1987), and Compromised Immunity (1987). ↩︎

-

14

Stuart Marshall interviewed on Gayblevision. ↩︎

-

15

Hallas, Reframing Bodies, 27. ↩︎

-

16

“‘A Plague on You’: AIDS, the Media and the Truth”, Open Space, BBC Community Programme Unit of measurement, Lesbian and Gay Media Group, aired 4 November 1985, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x0sO1qDgxlM. ↩︎

-

17

A pamphlet produced by the Lesbian and Gay Media group in 1985 (Lesbian and Gay Media Group, “‘A Plague on You’”). ↩︎

-

18

Lesbian and Gay Media Group, “‘A Plague on You’”. ↩︎

-

19

Lesbian and Gay Media Group, “‘A Plague on You’”. ↩︎

-

20

Rebecca Close, “Videos for Post-Truth Times: Revisiting the AIDS-Related Work of Pratibha Parmar and Isaac Julien”, ArtAsiaPacific 105 (September–October 2017): 66. ↩︎

-

21

Stuart Marshall, “The Contemporary Political Use of Gay History: The Third Reich”, in How Do I Look? Queer Film and Video, ed. Bad Object-Choices (Seattle, WA: Bay Press, 1991), 68. See also Aimar Arriola, “Touching What Does Not Yet Exist: Stuart Marshall and the HIV/AIDS Archive”, Afterall: A Journal of Art, Context and Enquiry 41 (Spring–Summer 2016): 142–44. ↩︎

-

22

This Is Not an AIDS Advertisement, dir. Isaac Julien, 1987. 10 minutes. https://blackfilmarchive.com/This-is-Not-An-AIDS-Advertisement. ↩︎

-

23

Tom Folland, “Deregulating Identity AIDS, Art and Activism”, in Mirror Machine: Video and Identity, ed. Janine Marchessault (Toronto: YYZ Books, 1995), 228. Other British artists who made video work in this vein were Anna Thew (Eros Erosion, 1989; Cling Film, 1993) and Michael Curran (Amami Se Vuoi, 1994). ↩︎

-

24

Interview with Phillip Timmins by the author, London, October 2019. ↩︎

-

25

“About OutRage!”, OutRage!, https://outrage.org.uk/about/. ↩︎

-

26

Author’s conversation with Mark Harriott, London, December 2019. ↩︎

-

27

Juhasz, AIDS TV, 241. ↩︎

-

28

Hallas, Reframing Bodies, 91–92. ↩︎

-

29

Similar videos include AIDS and You, a series of public information tapes made by the North Manchester Health Authority that ran from 1986 to 1990. ↩︎

-

30

The Health Education Authority was established in 1987 as a special health authority to encourage health education and health promotion, and was largely funded by the UK government’s Department of Health. It was subsequently replaced by the Health Development Agency, which became part of the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). ↩︎

-

31

Author’s conversation with Sunil Gupta, London, December 2019. ↩︎

-

32

Similar videos include The Gay Man’s Guide to Safer Sex (1992) and Getting It Right: Safer Sex for Young Gay Men (1993), both produced by the Terrence Higgins Trust, who worked with the commercial porn director Mike Esser. ↩︎

Bibliography

Arriola, Aimar. “Touching What Does Not Yet Exist: Stuart Marshall and the HIV/AIDS Archive”. Afterall: A Journal of Art, Context and Enquiry 41 (Spring–Summer 2016): 142–44.

Clews, Colin. “1985: Television. ‘A Plague on You’—Gay in the 80s”. 14 January 2019. https://www.gayinthe80s.com/2019/01/1985-television-a-plague-on-you/.

Close, Rebecca. “Videos for Post-Truth Times: Revisiting the AIDS-Related Work of Pratibha Parmar and Isaac Julien”. ArtAsiaPacific 105 (September–October 2017): 66.

Crimp, Douglas. Introduction to “AIDS: Cultural Analysis / Cultural Activism”. Special issue, October 43 (1987): 14. DOI:10.2307/3397562.

Crimp, Douglas. Melancholia and Moralism: Essays on AIDS and Queer Politics. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2004.

Crimp, Douglas, and Adam Rolston. AIDS Demo Graphics. Seattle, WA: Bay Press, 1990.

Epstein, Steven. Impure Science: AIDS, Activism, and the Politics of Knowledge. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996.

Folland, Tom. “Deregulating Identity: Video and AIDS Activism”. In Mirror Machine: Video and Identity, edited by Janine Marchessault, 227–37. Toronto: YYZ Books, 1995.

Gott, Ted. Don’t Leave Me This Way: Art in the Age of AIDS. Canberra: National Gallery of Australia, 1995.

Hallas, Roger. Reframing Bodies: AIDS, Bearing Witness, and the Queer Moving Image. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2009.

Hubbard, Jim. “AIDS Activist Video and the Evolution of the Archive”. Jim Hubbard, 1 February 2018. https://www.jimhubbardfilms.com/writing/aids-activist-video-and-the-evolution-of-the-archive.

Hubbard, Jim. “Biographical/Historical Information, A Short History of AIDS Activist Video”. AIDS Activist Videotape Collection, 1985–2000, The New York Public Library, Manuscripts and Archives, New York, [2002]. https://archives.nypl.org/mss/3622.

International Center of Photography, Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery, and Photographers + Friends United against AIDS. The Indomitable Spirit: Photographers and Artists Respond in the Time of AIDS. New York: Photographers + Friends United Against AIDS, 1990.

Jones, Carolyn. Living Proof: Courage in the Face of AIDS. New York: Abbeville Press, 1994.

Juhasz, Alexandra. AIDS TV: Identity, Community, and Alternative Video. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1995.

Kerr, Ted. “Who Is HIV For?” WSQ: Women’s Studies Quarterly 42, nos. 3–4 (2014): 333–38. DOI:10.1353/wsq.2014.0043.

Marshall, Stuart. “The Contemporary Political Use of Gay History: The Third Reich”. In How Do I Look? Queer Film and Video, edited by Bad Object-Choices, 65–89. Seattle, WA: Bay Press, 1991.

Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky. Epistemology of the Closet. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008.

Spiro, Ellen. “What to Wear on Your Video Activist Outing (Because the Whole World Is Watching): A Camcordist’s Manifesto”. Independent, May 1991, 22.

Watney, Simon. Policing Desire: Pornography, AIDS, and the Media. 3rd ed. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997.

Filmography

Esser, Mike, and Chris Hughes, dirs. Getting It Right: Safer Sex for Young Gay Men. Pride Video Productions, 1993.

Gupta, Sunil, and Laura MacGregor, dirs. Cock Crazy or Scared Stiff. Leicester: Avid Productions, 1991–92.

Harriott, Mark. OUTRAGE! [various tapes]. 1990s.

Julien, Isaac, dir. This Is Not an AIDS Advertisement. 1987. 10 minutes. https://blackfilmarchive.com/This-is-Not-An-AIDS-Advertisement.

Leeds AIDS Advice Group. Mouthing Off: Women Speak Out about Safer Sex. 1991. 35 minutes.

Lesbian and Gay Media Group. “‘A Plague on You’: AIDS, the Media and the Truth”. Open Space. BBC Community Programme Unit. Aired 4 November 1985. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x0sO1qDgxlM.

Lewis, David, dir. The Gay Man’s Guide to Safer Sex. Prod. Mike Esser and Tony Carne, with Terrence Higgins Trust. Pride Video Productions. 1992.

Marshall, Stuart, dir. Bright Eyes. 1984. LUX. SD video, 79 minutes. https://lux.org.uk/work/bright-eyes/.

Marshall, Stuart, dir. Kaposi’s Sarcoma (A Plague and Its Symptoms). Vtape and LUX, 1983. 25 minutes.

Marshall, Stuart, dir. Over Our Dead Bodies, prod. Rebecca Dobbs. Channel 4. Aired 7 August 1991. 50/74 minutes.

North Manchester Health Authority. AIDS and You. 1986–90.

Parmar, Pratibha, dir. Reframing AIDS. Kali Films, 1987. 35 mins. https://vimeo.com/ondemand/reframingaids.

Timmins, Phillip, dir. Compromised Immunity. 1987.

Imprint

| Author | |

|---|---|

| Date | 14 July 2025 |

| Category | Curatorial Essay |

| Review status | Peer Reviewed (Double Blind) |

| License | Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) |

| Downloads | PDF format |

| Article DOI | https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-27/ewebbingall |

| Cite as | Webb-Ingall, Ed. “Do Not Tape Over: AIDS Activist Videos in the United Kingdom.” In British Art Studies: Queer Art in Britain since the 1980s (Edited by Fiona Anderson, Flora Dunster, Theo Gordon and Laura Guy), by Fiona Anderson, Flora Dunster, Theo Gordon, and Laura Guy. London and New Haven: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art and Yale Center for British Art, 2025. https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-27/ewebbingall. |