“More than Friends”

“More than Friends”: Bisexual Perspectives in Roberta M. Graham’s Fallen Angel and Helen Chadwick’s Lofos Nymphon

By Naomi Pearce

Abstract

This article traces Roberta M. Graham’s and Helen Chadwick’s creative and loving friendship through close readings of Graham’s Fallen Angel (1986) and Chadwick’s Lofos Nymphon (1987), exploring how these photographic installations illustrate what Clare Hemmings has described as a “bisexual perspective”. While the discourse around both artists’ work thoroughly documents their male collaborators, their relationship with, and influence on, one another has remained unexamined. When and why does bisexuality disappear, and with what effects? How does partiality and in-betweenness pose problems for the present-day imperative of queer artistic production to be visible? Deploying an embodied approach that draws on interviews with Graham and research on Chadwick’s archive, I narrate my longing for a bisexual genealogy through a series of “scenes” that expose the erotic and ethical terrain that often characterises such queer archival encounters. What insights does a bisexual perspective offer queer art history in its attempts to resist the discipline’s normative, canonising tendencies?

Scene 1: The British Library

It is September 2021: I am sitting in a sound booth in the British Library listening to an oral history interview with the Northern Irish artist Roberta M. Graham. Graham’s speech has a flat affect: memories are recalled in short statements with an economy seemingly shaped less by a reticence to share and more by a discomfort with language. The interviewer, Shirley Read, prompts and probes, as is her duty, willing more elaboration. I am listening as part of my ongoing research into artist communities in Hackney during the 1970s and 1980s, specifically those formed around Beck Road. As Graham remembers her creative and intimate relationships with fellow residents Genesis P-Orridge and Helen Chadwick, her tone shifts slightly, becoming more animated. The time of the tape is 2000, four years after Chadwick’s sudden, tragic early death. “We were best friends”, Graham begins, her voice faltering suddenly.1 In my notebook I draw a horizontal line in pencil, an instinctive gesture that appears to mark the seconds of silence that pass before Read can respond: “Oh, I’m sorry”. I strain to make sense of the sounds, holding my breath during the scramble briefly preceding the clunk of the machine. Whatever passes between the two women next—comfort, a glass of water, apologies, an explanation—is lost. The magnetic tape of the cassette collapses time, and their conversation resumes immediately. Graham continues: “We talked about work all the time, we were great friends, oh more than that”. It is Read’s turn for silence as she stutters, gropes for words, “I don’t know what to ask now”. In this struggle to articulate, I hear the reconfiguration of Graham and Chadwick in Read’s mind: friends become lovers and their (until this moment) presumed heterosexuality falters. “Yes, well, more than that”, Graham continues, “we supported each other”. Grief is palpable in the cadence of her voice. She falls silent again. I hear the muffled static of fabric being folded. I imagine a damp sleeve rubbed against a dripping nose. “Can I stop?” Graham whispers. Another clunk of the machine.

1I stop too, pausing the undulating sound wave of the digital file tracking across my computer screen. With the past receding, I become aware of my ears, hot and prickling inside the cushioned headphones. Dry mouth, clammy palms. Why do I feel like I’m doing something wrong? Alongside my fear of trespassing, intruding hungrily on a stranger’s pain, is a familiar feeling of loss, one that often accompanies queer archival encounters. But my listening elicits bodily pleasures too; flushed with recognition, heartbeat quickening, I stretch out this “fleeting moment” of queer ephemeral evidence, as José Esteban Muñoz encourages, fantasising about the traces of Chadwick and Graham’s relationship left “hanging in the air like a rumour”.2

2Introduction

I begin this article with my bodily responses to listening in the archive because the scene maps some of the erotic and ethical terrain of queer art-historical research. It raises questions about the role and limits of reading biography into the analysis of artworks, the extent to which researchers should narrate their attachments to the material they study, and the kind of knowledge that is produced when they do so. As Julia Bryan-Wilson has argued fiercely, although a queer art history that emphasises “visibility and outing” may have been an important strategy in the past, in our present it is “grossly insufficient”, offering instead the need to explore how artworks “might generate queer meanings—[by] which [she means] hold contradictions, foster discomfort and propel new structures of desire”.3

3Bryan-Wilson’s search for queer meanings guides my engagement with the artworks of Roberta M. Graham and Helen Chadwick. In this article, I study two photographic installations, Graham’s Fallen Angel (1986) and Chadwick’s Lofos Nymphon (1987), attempting to identify a “bisexual perspective” at work. This term, coined by the scholar Clare Hemmings, describes “a way of looking, rather than a thing to be looked at”. Hemming’s use of “perspective”, as opposed to “gaze”, centres bisexuality as contingent on other desires and behaviours constructed in the “formation and maintenance of sexual identity generally”.4 In tracing how bisexuality registers aesthetically, I do not try to fix or essentialise a bisexual perspective but, rather, explore the extent to which these works reproduce bisexual stereotypes such as promiscuity, transgression, and temporal and material flux. Rather than refuse these readings or label these images as “biphobic”, I consider what can be learnt by examining them more closely. As members of the Bi Academic Intervention remind us, “stereotypes are just a shorthand for passing on information”. What is needed is more “analysis of the ways in which meanings accrue; and also—to take the analysis into more actively political realms—what strategies can be used to effect a more useful or enabling range of meanings”.5

4My enquiry is informed by research in Chadwick’s archive and telephone conversations with Graham. These physical encounters, motivated by my own yearning for a bisexual genealogy, follow what Elizabeth Freeman calls the queer activity of “mining the present for signs of undetonated energy from past revolutions”.6 Freeman uses the term “erotohistoriography” to describe what it means to take pleasure in “rubbing up against the past”.7 Unlike desire, which is marked by lack, Freeman argues that erotics “traffic less in belief than in encounter, less in damaged wholes than in intersections of body parts, less in loss than in novel possibility”.8 Rather than seek to restore the past, Freeman’s erotics treat the present as “hybrid”, insisting on “historical consciousness as something intimately involved with corporeal sensations”.9 Alongside my own erotic archival encounters, in which I reach to touch the past, I explore the ways in which an erotohistoriography is staged in both installations through their activation of touch. I analyse these gestures alongside Sara Ahmed’s affective writing on the impressions made by moments of queer contact.10

6Both Fallen Angel and Lofos Nymphon were exhibited at the Photographers’ Gallery in the 1987 group exhibition The Body Politic: Re-presentations of Sexuality (figs. 1 and 2). Although Chadwick physically appears in Graham’s photographs, her presence goes unacknowledged in both the description of the work and responses to the exhibition. I realised it was Chadwick only because I recognised her jewellery: those distinctive silver rings. This absence disappoints me, especially since the heterosexual collaborations of Chadwick and Graham are thoroughly documented both by the artists themselves and in the critical discourse around their works—most famously perhaps in Chadwick’s Piss Flowers (1991–92), sculptures that were co-created with her partner, David Notarius. When and why does bisexuality disappear, and with what effects? And how does this partiality pose problems for the present-day imperative of queer artistic production to be visible in order to have meaning and political impact?

In a talk at the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in 2016 to mark the thirtieth anniversary of Chadwick’s exhibition Of Mutability, friends and peers including Louisa Buck, Cathy de Monchaux, and Marina Warner gathered on stage to pay tribute to the artist and discuss her legacy. During the questions session, audience members asked the panel about Chadwick’s relationship with her female peers. De Monchaux answered, “I’m not aware she was a group player. I think she had enough thoughts in her own head to need to belong to a collective”.11 Later, Louisa Buck clarified, “she wasn’t uncollegiate, but she very much ploughed her own furrow”.12 This narrative of solitary production, of collaboration as evidence of some kind of lack, tells a familiar art-historical story in which the creative process is articulated in asocial terms. Linda Nochlin famously critiqued the “individual-glorifying” substructure on which art history rests.13 She called for a dismissal of biography, for gender to be removed from the equation in order for the myth of male genius to be overcome: “the language of art is, more materially, embodied in paint and line on canvas or paper, in stone or clay or plastic or metal—it is neither a sob-story nor a confidential whisper”.14 Are there other ways of listening to a whisper? Why does it have to be either/or? In contrast, throughout this article I attend to Chadwick and Graham’s relationship in the spirit of “getting lost” within a network of sexual and social relations, to reframe their work and relationship in terms of a “queer relationality”, as charted by Muñoz, that is geared towards a collectivity able to imagine a future beyond our negative present.15 Rather than keep Chadwick and Graham’s relationship outside of their art, to dismiss it as erotic fun, I read their intimate bodily knowledge as an integral engine for their work—a method, if you will—and thus worthy of attention.

11As Clare Hemmings, Merl Storr, Michael du Plessis, and others have argued, queer theory has been inattentive to bisexuality.16 During the 1980s and early 1990s, a reclamation of “queer” unfolded simultaneously alongside an increased awareness of bisexual identity and politics. As noted in Cherry Smyth’s pamphlet Lesbians Talk about Queer Notions, “one of the founding aims of Queer Nation [an LGBTQ activist organisation established in New York City] was to incorporate bisexuals into the lesbian and gay movement”.17 And yet, despite my desire to argue for bisexuality’s queer credentials, to make them “touch”, in writing Chadwick and Graham as queer art history, a heterosexist hegemony is carried into this special issue. Both Chadwick and Graham lived with male partners; they were not socially or creatively embedded within a queer community. Despite sexuality being an important and often discussed subject in their works, neither artist publicly declared their attraction to, nor their relationships with, women. Hemmings’s spatial configuration of bisexuality is also useful here; her observation that “bisexual subjectivity is historically and culturally formed almost exclusively in lesbian, gay or straight spaces” points to how a lack of a bisexual home may be understood as contributing to the “partiality bisexuals commonly experience”.18 Like Hemmings, I do not seek to resolve this partiality, to try to make it whole, but instead explore what writing through illegitimacy and ambivalence can offer art history, a discipline that is so reliant on visibility logics that serve to commodify and categorise. Perhaps the contingency of a bisexual perspective will engender something more indeterminate than queer canonisation.

16Fallen Angel

Roberta M. Graham’s Fallen Angel comprises eight framed photographic panels with accompanying text pieces by the writer Ken Hollings. Described by Graham as a “study of Mary Shelley and the writing of Frankenstein”, the series envisions the act of creation—be it childbirth or the artistic process—as one of deep anxiety, closely linked with pain and death.19 In the first photograph Graham’s body hugs a block of ice (fig. 3). With the stark contrast between her opaque white skin and the translucent glow of frozen water, the ice appears collaged into the frame in post-production. In my telephone conversion with her, Graham clarified that it took four people to drag the ice up the stairs to her flat in Archway, north London, where the shoot took place. The image restages a traumatic moment in Shelley’s life when, following a miscarriage, she was plunged into a bath of ice to staunch the bleeding. In Graham’s retelling, survival is granted by active embrace, not passive immersion.

19

In Frankenstein, Shelley configures lightning as an energy source that enables life. In Fallen Angel, Graham and Hollings write in a statement about the work that lightning is “transformed into the spark of desire itself”.20 With this reorientation, desire keeps the blood flowing and the heart beating, and Graham’s passions are “cooled off” by her icy clinch. In a 1986 interview for CIRCA magazine, the artist references a poem fragment by Percy Bysshe Shelley as additional inspiration for this image, with the veiny surface of the ice mimicking the bodily veins described by Shelley as a place “where busy thought and blind sensation mingle; / To nurse the image of unfelt caresses”.21 Again, Graham is preoccupied with a loving touch. The caresses are longed for but not physically felt, and their image is nursed, as in cared for but also harbouring a feeling characterised by its secret, extended duration.

20In Frankenstein, the doctor gives birth to the monster put together from parts of other bodies. This metabolism harnesses science to transgress a boundary between life and death, and it’s here, in the mingling of objects and states, that horror lies. Like the novel, Fallen Angel stages an excessive instability in a series of dramatic bodily encounters. Graham is the constant connecting figure who moves between and across. She is depicted in bed with a male figure (Ken Hollings) and then with the other female protagonist (Helen Chadwick) (figs. 4 and 5). Many of the objects mobilised, such as eggs and eels, are symbolically gendered, emphasising a distinct binary that is in turn reaffirmed by the images’ black-and-white colouring. This chiaroscuro technique lends the encounters a dramatic sensuality, shielding the bodies depicted while also throwing their curves into sharp relief. I am reminded of the criticism often levelled at bisexuality by queer theorists such as Eve Sedgwick and Lee Edelman, that bisexuality is defined through the opposition of heterosexual–homosexual and thus reinforces rather than troubles this binary.22

22

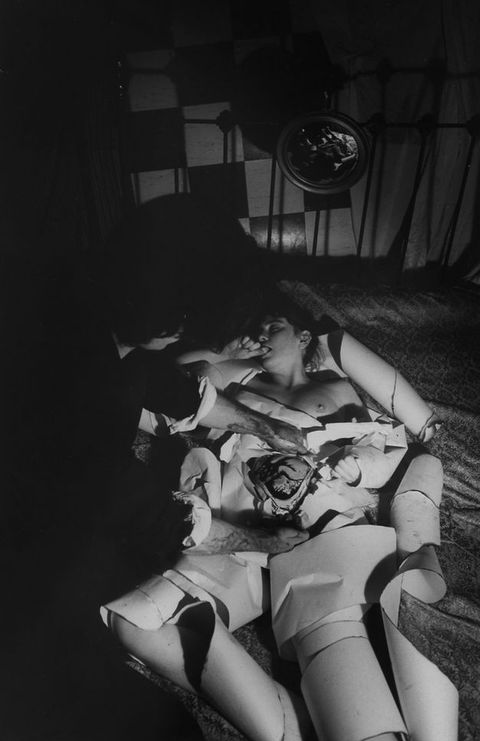

Fallen Angel depicts a series of births. Only one produces an actual foetus, depicted still curled inside the womb, painted or drawn on rolls of paper that wind and wrap around Graham’s prone limbs (fig. 6). The other birth is more ambiguous: in this scene, the fourth photograph in the series, the camera captures Graham and Chadwick together on a bed from above (fig. 5). From our omniscient view we float above the scene, watching Chadwick’s hand press firmly into Graham’s abdomen, their naked bodies entwined in tension amid crumpled sheets. A red umbilical cord (the spark of desire?) crackles through the centre of the frame, connecting the two women, its source stemming from Chadwick’s fingertips. Graham’s fist clenches, as though gripped by pain, ecstasy, or some other sensation, while her other hand claws at Chadwick’s forearm. Meanwhile, Chadwick crouches, head bowed, staring into Graham’s crotch, her lips pressed together; a confident pose, the kind one might make when a lover’s orgasm is in one’s grasp.

This photograph, like all the images in the exhibited Fallen Angel series, is hand-tinted. Graham worked as a retoucher after college, fixing “tiny little things” in photographs for an advertising agency.23 Despite its being a “horrible job”, the work informed her approach to image-marking.24 In the context of Fallen Angel, this fiddly and time-consuming process can be interpreted as an expression of care. I’m compelled to read the labour and attention Graham imbues in this image as proof of her attachment to Chadwick. During our telephone conversation, I asked if she was happy with my reading of Fallen Angel as an act of bisexual self-portraiture? “Yes”, she replied. With these words, I felt my shoulders relax. I breathed. What did I breathe? A sigh of relief. As my stomach settled, I became aware of how tightly I had been holding this artwork, how I had longed for Graham to affirm my speculations and feared their disavowal. Until this moment on the phone, the pleasure of my engagement with Fallen Angel was motivated by what Caroline Evans and Lorraine Gamman have referred to as “subcultural competencies”, a phrase they use to describe the lesbian viewer’s thrill at detecting lesbian pleasure in a mainstream location.25 As Reina Lewis elaborates, the pleasure produced in this looking “does not reside in the representation, but in the activity of decoding it”.26 I knew I had recognised something bisexual about Fallen Angel despite its failure to come into focus when it was exhibited at the Photographers’ Gallery thirty-two years earlier.

23“Naked Girls” Looking

“Old, wrinkled, fat, unglamorous” was how one reviewer described the bodies on display in the exhibition The Body Politic: Re-presentations of Sexuality during that wet summer of 1987.27 Staged at the Photographers’ Gallery and curated by Alexandra Noble in collaboration with Ten.8 magazine, The Body Politic sought to extend and reflect debates about representation and sexuality. Featuring fifteen artists and including four new commissions, the exhibition elicited largely critical responses from the British press, varying from lukewarm dismissal to heated disgust. It was “oblique”, too “self-indulgent”, nothing more than “pseudo-intellectual pap”.28 Criticism was levied at the presentation’s theoretical framing: “In this welter of semiological verbiage the photographs tend to vanish; they simply cannot bear the weight of assertion and analysis”.29 Other aspects vanished too. As the exhibition statement written by Noble acknowledged, “invisibility has certainly affected the presentation of homosexual and lesbian relationships”.30 Although Emmanuel Cooper, writing for the Gay Times, took the work seriously, describing the exhibition as a “lively, if at times uneven show” and attending positively to contributions by Rosy Martin, Sunil Gupta, Diana Blok, and Emily Andersen, like the straight press he too had reservations about the nudity on display, concluding that “the use of the naked body as a subject for ‘revealing all’ is not sufficient in the late '80s”.31 Missing from Cooper’s analysis are Barbara Kruger, Roberta M. Graham, Helen Chadwick, Mitra Tabrizian, and Susan Trangmar. Of these works, only Graham and Chadwick’s feature nudity and, as such, I assume his critique was directed at their contributions. Elsewhere, another reviewer dismissively read Chadwick and Graham in Fallen Angel as nothing more than “naked girls”.32 Nudity here is framed as a distraction, lacking meaning or depth.

27The use of “girl” also implies an immaturity, a notion associated with bisexuality as conceived in the psychoanalytic works of Freud, where it is considered the universal state of all infants, a sexuality out of which to mature. This understanding of bisexuality is briefly referenced (although not in relation to Fallen Angel) in the essay by Anne Williams included in a special issue of Ten.8 published to coincide with the exhibition. Williams focuses on the activation of the gaze, drawing on Laura Mulvey’s influential essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” (1975) to map out “relations of looking” within the exhibition.33 The works “confound the gaze”, Williams writes, offering instead an “ambivalence of viewpoint”.34 Thinking with Williams’s ambivalence, what if the lack of declaration regarding Chadwick and Graham’s relationship was motivated by a desire to resist the viewer’s voyeuristic gaze? Across all eight photographs of Fallen Angel, none of the figures address the anticipated viewer at all; instead, their eyes turn inwards or remain fixed on one another.

33This way of looking—oscillating between relational and introspective—diverges from the American photographer Honey Lee Cottrell’s description of the lesbian gaze, which hinges on the demands made by the look and the direction it travels: “while your heterosexual woman model might compel the rest of the world to look at her, a lesbian was addressing you”.35

35Although none of the figures in Fallen Angel address us, they do not seek our attention either. Graham constructs a hermetic space in the photographs, a feeling emphasised by how the bodies touch. In six of the eight images, two figures appear—their hands clasped or their legs entwined. In the sixth image, Graham cradles Hollings’s limp body in a pose reminiscent of Michelangelo Buonarroti’s La Madonna della Pietà (1498–99), a marble sculpture depicting the Virgin Mary holding the mortal body of Jesus Christ (figs. 7 and 8). This repetition of more than one figure in relation, making contact, is one of the defining tropes of what I interpret as Graham’s bisexual perspective.

At first glance, Cottrell’s emphasis on how a lesbian looks at the viewer shares qualities with Hemmings’s bisexual perspective. However, there is a key distinction, as Hemmings clarifies: “in this context, the bisexual I/eye does not see itself reflected back in the object of its gaze, but foregrounds bisexuality in its various forms and functions, whatever the final form of the object”.36 Unlike Cottrell’s lesbian gaze, a bisexual perspective anticipates misrecognition and remains inconsistent; it mutates, perhaps much like Frankenstein’s monster. Fallen Angel harnesses this mutating gaze by mobilising and moving across different bodies, refusing ultimately to settle on any one object or form.

36Temporal Fissures

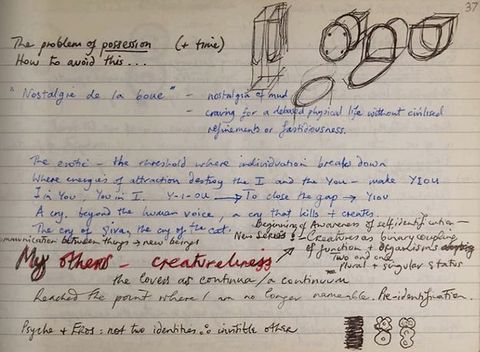

It is tempting to read a linear narrative into the image sequence; birth does indeed follow sex (although, of course, not always). However, rather than presenting a progressive series of events, the photographs offer a choreography of cyclical return, of bodies connecting, disentangling, and coming together again. In the seventh photograph a third kind of touch occurs as Graham’s and Hollings’s bodies fuse into a single body (fig. 9). In Graham’s left hand an eel flops flaccidly from the wine glass, while in Hollings’s right hand an egg is held aloft like an offering. Two heads share one belly button. In its duplicity the image adheres to a biological definition of bisexuality as the presence within an organism of male and female characteristics. It is an image of doubleness rather than of becoming, in which both Graham and Hollings are visible but separate. In the context of Fallen Angel’s desiring bodies, it may also be read as a vision of the erotic fusing that occurs during a sexual encounter. As Chadwick articulated in her notebooks: “The erotic–the threshold where individuation breaks down. Where energies of attraction destroy the I and the You = make YIOU, I in You, You in I, Y-I-OU—to close the gap–YIOU” (fig. 10).37

37

According to Jack Halberstam, the gothic form is characterised by the genre’s dissolution of boundaries. In his writing on Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein Halberstam explores how this troubling in turn generates fear:

38the reading subject (but also the characters and seemingly the writer) of the Gothic is constructed out of a kind of paranoia about boundaries: Do I read or am I written? Am I monster or monster maker? Am I monster hunter or the hunted? Am I human or other? For the modern reader such questions might seem to circle around sexual identity, Who/what do I desire?38

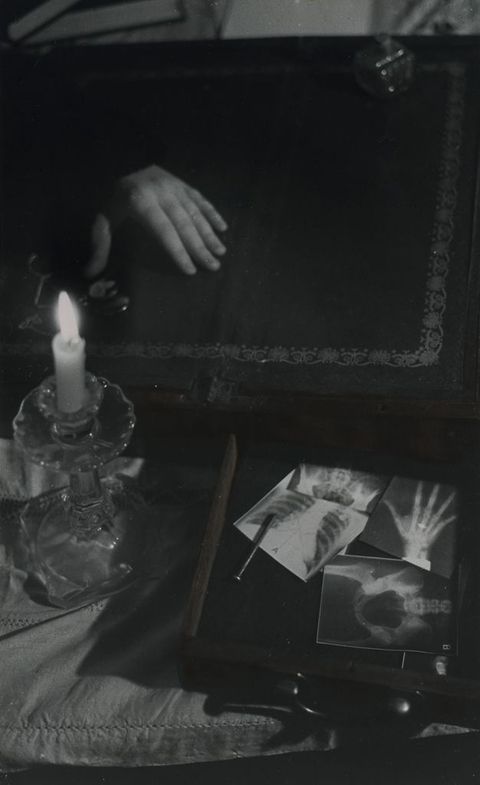

These questions resonate with Graham’s decision to suture her own life and creative process to Shelley’s. It’s not clear who is being read and who is being written, or what is art and what is desire: life collapses into fiction. Freeman’s reading of Frankenstein builds on Halberstam’s to explore how the “temporal fissures” produced by the novel’s epistolary narrative structure combine with the monster’s physical hybridity to capture “the erotics of historical consciousness”.39 These temporal fissures are replicated by Graham’s engagement with the novel and Shelley’s biography as she re-enacts scenes from the author’s life, mingling these with Frankenstein’s scientific and mystical imagery, from X-rays, textbooks, and glass flasks to dead chickens, molten silver, and mortar and pestle (figs. 11 and 12). These references are used playfully, and Graham brings them to touch her own erotic relationships by constructing the temporary fantasy space of Fallen Angel. In the artist’s bedroom, Shelley’s gothic Geneva of epic landscapes and grand mansions meets the modest rented domesticity of Thatcher’s Conservative Britain. An excessive sensual melodrama is produced by this fusion, which is evident in the expressions of angst and dramatic lighting, as well as in the ornate frames, each collaged with an array of materials including resin, crackle finish paint, black netting, and quills of paper. The overall aesthetic appears to revel in the illusion of antique luxury. In this regard, Fallen Angel expresses a “love of the unnatural: of artifice and exaggeration” in the spirit of Susan Sontag’s “camp”.40 Coincidently, Sontag’s essay traces camp’s origins to the eighteenth century, citing gothic novels as an early reference. With hindsight, Graham’s 1987 turn back to the gothic, a style and genre combining romance and horror, anticipates the conflicting feelings of love, fear, and grief that were to characterise the next decade for queer communities, as they came together to ensure their survival, while simultaneously fighting for rights and healthcare during the HIV/AIDS crisis and homophobic legislation such as Section 28.

39Temporal fissures multiply with my own delayed eavesdropping on Graham’s interview and subsequent viewing of Fallen Angel. Freeman’s evocation of camp as “temporally hybrid” resonates with our shared anachronistic engagements.41 Camp, she argues “is a mode of archiving, in that it lovingly, sadistically, even masochistically brings back dominant culture’s junk”, revealing a “fierce attachment to it”.42 This reflects my own desire to make visible the loving friendship of Chadwick and Graham that lies undetonated in Fallen Angel, despite the potentially retrogressive, compromised, and foreclosing effect of its bisexual representation.43 Graham has stated that Frankenstein interested her for the ways in which the narrative makes explicit the sense that you can’t create anything without spawning “monsters at the same time”.44 Arguably, one of the monsters Fallen Angel produces is a stereotypical promiscuous bisexuality—a desire rooted in sex acts, not identity, that moves between men and women but returns to heterosexuality (as it is often assumed a bisexual will). Across the series, Chadwick appears only once, whereas Hollings is depicted multiple times. He is described as a collaborator, whereas Chadwick is uncredited. As though anticipating this criticism, the final image is ambiguous, depicting two figures hands outstretched, their heads out of shot (fig. 12). I look for Chadwick’s rings but there are none. Hollings and Graham are the last figures to touch.

41Queer Collectivity and Bisexual Attachments

If we refuse a linear reading of Fallen Angel, other narratives come into focus. The work simultaneously conjures a space outside of heteronormativity, presenting a polyamorous scenario where lovers are multiple and relationships reproduce creativity and desire but not children. These formulations adhere to a utopian vision of “queerness as collectivity” akin to the kind hoped for by Muñoz, a way of living that dares to “see or imagine the not-yet-conscious”.45 The desires on display conceive of bisexuality as a practice of plural loves, one that does not cohere with either heterosexual or homosexual conceptions of coupledom. This chimes with my own bisexual experience and those of Graham’s contemporaries as documented in Bisexual Lives (1988), the first book by and about the UK bisexual community.46 In the section “Friends”, one interviewer imparts: “I think my bisexuality helps blur the distinctions between friends and lovers. Large amounts of my emotional energy goes out to friends, often much more than to my lovers”.47 In the British Library interview, Graham articulated her relationship with Chadwick as “more than friends”.48 During our conversations the artist elaborated further:

4549Helen and I were partners for five or six years, on and off, but it was on and off and on and off. This was spread out. We were best friends for 17 years, so that was quite a long time. We’d be together for two years, and then we’d not not talk, but not be together, and then we’d get back together, that kind of thing … We’d stay up all night talking, all the time. I think you can see it in the work.49

Something not immediately evident is the second male presence haunting Fallen Angel: Sean Trowbridge, Graham’s long-term partner. Trowbridge was behind the camera throughout the shoot, as Graham recalls: “he’s very good at knowing what I want things to look like”.50 Despite the ability of these images to imagine a transgressive queer relationality, Trowbridge’s presence reorientates the work towards Graham’s bisexual perspective. Following Hemmings, by emphasising this, I make transparent the people of importance in Graham’s life and “the different power relationships that are attached to those forms of desire”.51 Trowbridge’s mechanical gaze may have been directed in accordance with Graham’s storyboards, but his mediation evidences the significance of their relationship in the manifestation of the work. I highlight this as an example of the complex and contradictory dynamics of bisexual investments. These tensions, although present in the imagery of Fallen Angel, are also embedded in the production process itself.

50Scene 2: The Henry Moore Institute

It is September 2023: I am sitting at a desk in the Henry Moore Institute leafing through box 99 from the Papers of Helen Chadwick. I am not alone; the archivist sits at her computer a few feet away. Although she has been helpful and is now busy with her work, I feel her presence as scrutiny.

In my initial email to the archive, I emphasised my interest in viewing materials relating to Chadwick’s Viral Landscapes (1989). Although I mentioned her relationship with Roberta M. Graham, I was indirect, writing somewhat evasively, “I’d love to find any record of their friendship”. The archivist sends back the box list accompanying Chadwick’s papers, a seventy-one-page document that operates as a textual finding aid, the means by which this extensive collection can be navigated. Graham is not referenced. I am not surprised but my heart still sinks. Despite this absence, I do find scribbled references to “eve Roberta” or “R eve” in the pages of Chadwick’s appointment diaries. There are sixteen of these slim volumes dating from 1977 to 1996, each bursting with activity, evidence of Chadwick’s energy for social and work life and the joy she found in her creative practice. The diaries are a mess of blue biro, red and black pen, Tippex, crossings out, arrows, sums. My fingers turn pages that crackle with the impressions of this layered mark-making, each week a whirlwind of teaching, fabrication tests, meetings, private views: art and life enmeshed.

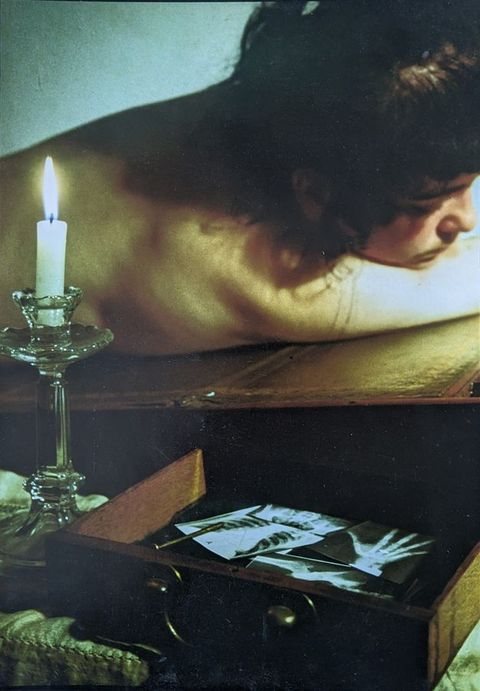

In box 99 I find a version of the second photograph in Fallen Angel in a box of Christmas cards. Graham’s hand has gone from the empty dresser and, in its place, her strong back twists across its surface, chin resting in the dip of her collarbone (fig. 13). The back of the photograph is annotated “For F. From Fallen Angel. With Love, RMG x”: an initialled nickname to signal their intimacy.52 The box also contains Chadwick’s Christmas card lists, the personal and professional contacts that form her network of relations. I look for Graham’s name, judging the women’s closeness by how far up the list it appears. Is she the first one Chadwick thinks of? Is Graham higher up the list than the men? I know I’m engaging in a monstrous kind of scholarship, one spurred by an insecure desire for legitimacy. I don’t stop. I spend an hour looking through the names, trying the decipher Chadwick’s writing, as if these lists might provide the proof I need that she loved her too.

52Lofos Nymphon

In Lofos Nymphon Chadwick inserts herself into a normative tale of marriage and property with a reparative agenda. “Hill of the Nymphs” is a real place—the site of the National Observatory of Athens—but the work’s title also references a street, Odos Nymphon (Road of the Nymphs), on which Chadwick’s maternal great-grandfather built a home for his newlywed daughter. The house was to be passed down to Chadwick’s mother, Angeline, through the maternal family line; however, on leaving Athens in 1946 to marry Chadwick’s father (an English soldier who had been posted to Greece during the Second World War), she forfeited her claim on the property.

Lofos Nymphon consists of five photographs featuring Chadwick and her mother, taken on the balcony of this lost house. These images are projected onto vivid egg-shaped panels coloured with oil paint. At the Body Politic exhibition, they were installed in a temporary hexagonal-shaped structure. In letters to the curator Alexandra Noble, Chadwick argued that this immersive configuration gave the viewer “a much better impression of a panoramic piece than entering from the wings”.53 She wanted Lofos Nymphon to envelop the gallery visitor in a spatial embrace, one that extended the familial intimacy on display (fig. 14). In the photographs the women pose together naked, nymph-like, their bodies set against a backdrop of architectural sites visible from the balcony. As well as mapping the ancient city, the work also charts the movement of the sun. Chadwick begins with an image of the Asteroskopeion—the national observatory of Athens—at dawn and ends with the Pnyx—a historically significant site of public assembly—at dusk.

53

Chadwick wrote an essay to accompany the piece, and the working drafts are among her papers. In the first version she writes that, for a son, the mother “can return as bride + lover” but, for a woman, “to couple female with female, as adults + of the same family, such embraces of love in same-ness are not only difficult, they lie in the realm of the unspoken + the forbidden”.54 By the final (third) draft, the phrase “+ of the same family” is omitted. While the rest of the paragraph focuses on “filial devotion”, with this edit a same-sex desire is brought into the space of the work. Chadwick closes with a description of Lofos Nymphon as a “pre-Oedipal reverie”.55 This psychoanalytic evocation reiterates not only her desire to return to the mother but also that naturally innate primordial bisexuality conceived of by Freud. There is a sense that Chadwick reinforces this configuring, which (as discussed briefly earlier) perpetuates an understanding of bisexuality as immature. Described by the press release as exploring “the sexuality inherent in mother/daughter relationships”, Lofos Nymphon’s dreamy transgressions conjure more than a few of what Michael du Plessis identifies as the “extreme values” carried by bisexuality: “extolled as progressive, ‘chic’, as a panacea, a fantasy, a promised land, mythologised as origin of all desires, or vituperated as reactionary, infantile, regressive, a red herring, a cop-out, a lie, a dead-end street”.56

54I can’t ask Chadwick if a bisexual perspective, shaped by her relationship with Graham, is present in Lofos Nymphon. Even if I could, would this be the right question? It’s not as though bisexuality of a kind, by which I mean the biological definition, isn’t already visible in the work. As Mary Horlock has observed, much of Chadwick’s later work sought to create images and sculptures that troubled and confused the gender binary.57 Chadwick’s library contained several books relating to historical intersex figures, including Michel Foucault’s edition of Herculine Barbin’s memoirs. Marina Warner’s recent writing has speculated as to whether Chadwick, had she lived to our present, might have embraced “the possibility of a non-binary identity”.58 In contrast to this rich discussion, there is scant exploration of how Chadwick’s work troubled the hetero–homo dyad. This absence is in part due to Chadwick’s vocal participation in the discourse around her work. She spoke frankly about her intentions. For example, in one of her last interviews she discussed Piss Flowers: “Obviously, flowers as the bisexual reproductive organs of plants, have both male and female sexual features and that was one of the reasons that I chose this image”.59 I’m interested in what other meanings are hushed or drowned out as a consequence of Chadwick’s clear speaking. Later in the same interview, she reflects insightfully: “meaning is contingent upon so many different things—it is infinitely flexible. If I have a criticism about my work, it is that it is often too mediated, too controlled”.60 I take Chadwick’s desire for more flux or fluidity as an invitation (one loaded with bisexual connotations) to read other pleasures into her work.

57Narrative Cords

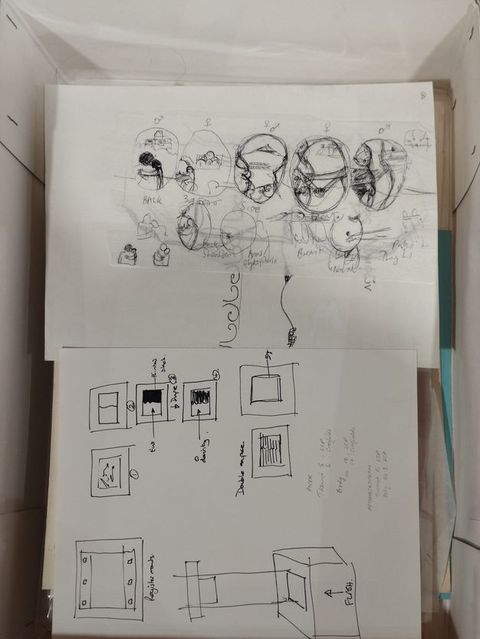

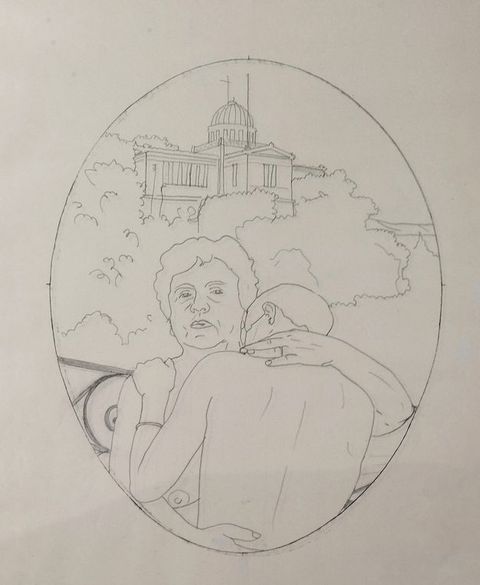

Preparatory drawings for Lofos Nymphon assign a symbol to each of the egg-shaped panels (fig. 15). In her notes Chadwick details her intention—“sex of objects/places”—but doesn’t elaborate on the allocation process.61 At first I think it relates to the Greek gendering of nouns, but the masculine and feminine endings don’t seem to correlate. Then I look for a pattern in the poses; panels featuring breasts and faces are designated female, while the images with more androgynous body parts, such as the first panel, which is dominated by Chadwick’s back and the crown of her cropped hair, are designated male (fig. 16). The third photograph is the only one labelled male and female (fig. 17). Here Chadwick and her mother do not touch; their bodies stand like sentries, framing the view of the Agora (the primary public gathering place for ancient Athenians). The body of Chadwick’s mother, with full breasts and soft stomach, contrasts with the taut torso of her daughter, whose raised arms give her chest an angular shape that resembles firm pectoral muscles, making the body appear less immediately sexed as female. This panel bridges genders. At the Photographers’ Gallery it was the central panel in the panorama, directly facing the entrance, and the first image encountered by a viewer. Here, gendered indeterminacy meets Freeman’s “living historically”, with Chadwick practising a form of erotohistoriography as she brings her naked flesh to touch personal and cultural lost pasts. In embracing her mother, she performs a “not-quite-queer-enough longing” to return to the safety of childhood.62 The balcony’s curling rail is a “narrative cord” (as Chadwick describes it in her essay) reconnecting her mother’s body to her own.63 She may drag them both back to the domestic space, the ancestral home. However, the daily grind of nurture is reimagined as something queerer: it is contemplative, unproductive, sensual.

61

The balcony as narrative cord takes us somewhere else too—back to the umbilical cord that connects Chadwick and Graham in Fallen Angel. It is one of the many conceptual and material references shared by the two installations. From eggs to mothering, these works talk to each other. Perhaps most significant is their shared use of light. Lofos Nymphon belongs to Chadwick’s Lumina series, a body of works created between 1986 and 1988 featuring photographic images slide-projected onto painted surfaces. Just as Fallen Angel reimagines lightning as the spark of desire, in the Lumina series Chadwick is seduced by the coming together of phenomena during the illumination process or, as she put it, the moment when “light touches a surface”.64 Reminiscent of Roland Barthes’s understanding of light as an “umbilical cord” linking the bodies of the photograph to the viewer’s gaze, Chadwick’s projections are intangible but affecting.65 As with Fallen Angel’s suturing of creativity and death, Lofos Nymphon conceives of the haptic connection across time as always threatened by loss. In creating an artwork with light, Chadwick courts what is fleeting; her projected images remain ungraspable or, as she described it, “The work is deliberately insubstantial in terms of its physicality. It doesn’t hardly exist”.66 To willingly ride this line reflects the partiality of a bisexual perspective; rather than see it as lacking something, Chadwick revels in it.

64

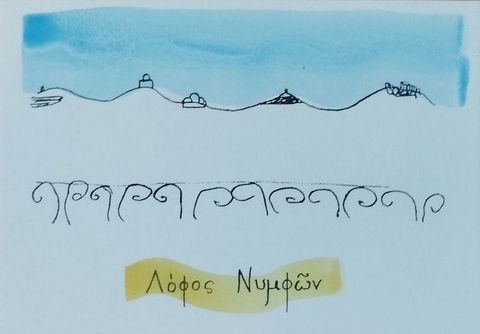

Weaving Loops

Lofos Nymphon sees the body in everything, including the city of Athens itself: arches and domes are anthropomorphised, and the balcony’s curved metal become “Buttocks” in Chadwick’s notes. Eventually this peachy doodle will be transformed into an invitation card, its simple line reproduced in black ink and coloured with a wash of yellow and blue watercolour (fig. 18). This desire brings her body to touch architectural remnants and, in doing so, challenges the patriarchal Western vision of Athens—one that Chadwick understands as denying the city’s “African and archaic roots”.67 As she wilfully demands, “let the monuments be eroticised and the very gender of the city called into question”.68

67

Jo Eadie’s description of bisexuality as a “hybrid” identity resonates with Chadwick’s simultaneous exploration of her gender, sexuality and Greek identity.69 Drawing on Homi K. Bhabha’s use of the term in the context of race and colonialism, Eadie charts how hybridity “supplements dominant terms, and signals their limitations by finding new uses for them”.70 Whereas I interpret Chadwick’s later works—for example, the series Viral Landscapes (1989), with its unbounded dispersal of human cells across the Pembrokeshire coast—as embodying Eadie’s hybrid reimagining more fully, Lofos Nymphon is an awkward first foray into this uncharted territory.

69There is tantalising possibility in the open suggestion of Chadwick’s erotised monuments, an idea she would later develop in an essay for Architecture, Space, Painting, in which she asks: “Why do we feel compelled to read gender, and automatically wish to ‘sex’ the body before us so we can orientate our desire and thus gain pleasure or reject what we see?”71 This question makes clear the erotic stakes of Chadwick’s project: undo the gender binary to reimagine intimacy by cultivating desires based on sensations: the smell, taste, sound of a lover; the feeling of their hair coiled in a crevice of skin.

71Chadwick’s description of desire as a feeling that moves us in certain directions echoes Sara Ahmed’s writing on queer phenomenology and how bodies orientate to find their way in the world. Extending this idea, Ahmed thinks about the “lines that direct us”, be they the ones we inherit from family and social space or the privileges of following heterosexuality’s well-trodden paths.72 Alongside the lines of inheritance depicted in Lofos Nymphon, the installation renders a physical horizon line as well: it bisects the wall, connecting each egg-shaped panel. This line orientates, separating the sky from the land, but is also a nod to the rules of perspective drawing, in which the horizon line is a foundational element. Despite the straightness of Chadwick’s horizon line, and its apparent compliance with the rules of perspective, it does not quite cohere, shifting up and down, moving as it encounters each panel’s new vista or limb. In Ahmed’s writing, lines are metaphors for sexual orientation. She describes her experience of “dramatic redirection” and her decision to follow a different line when she “left the ‘world’ of heterosexuality and became a lesbian”.73 In contrast, Chadwick’s singular line appears to embody the indeterminacy of a bisexual perspective, one that fails to follow a straight path but never encounters Ahmed’s fork in the road either.

72Despite this sense of continuity, the work marks a transitional moment within Chadwick’s career; it is the last time she depicts her body in an artwork. Speaking to Modern Painters in 1994, the artist described her move away from figurative representation as a conscious decision: “it immediately declares female gender and I wanted to be more deft”.74 I interpret this to mean that Chadwick wanted to make her work more robust to the kind of critiques espoused by Marjorie Allthorpe-Guyton in an Art Monthly review of Of Mutability at the ICA, where the critic describes Chadwick’s use of her body as a “problem” that “flies in the face of much recent feminist thought”.75 As discussed earlier, the presence of nudity in The Body Politic distracted many of the critics and no doubt their lack of serious engagement was frustrating for Chadwick. However, I wonder if she had reached another limit. Allthorpe-Guyton’s review is preoccupied with the male gaze, as though any other pleasure-seeking viewer is unimaginable. Perhaps Chadwick was uncomfortable with how her body was being read in general. She had wanted the work to “weave loops, twists and turns around binary categories”, but instead faced responses that reasserted a heterosexual cisgender identity.76 As Ahmed has written elsewhere, “one can be made to feel uneasy by one’s inhabitance of an ideal. One can be made uncomfortable by one’s own comforts”.77

74Going Back (To Conclude)

I ask Graham about Chadwick’s move away from depicting her body. She replies, “she just went in the direction of what she became obsessed with”.78 Her answer makes me reflect on the question. To move away implies a moving on, which in turn imposes a narrative of progress while also overstating an artist’s conscious intention. Graham adds a further thought: “[the work] might have gone back that way”.79 Of course, Chadwick could have returned to depicting her body; the truth is we don’t know. It’s difficult to imagine where Chadwick might have gone because of the historicising of her practice in the wake of her sudden early death. But, as I have tried to reveal through my encounters with Fallen Angel and Lofos Nymphon, it is always possible to go back, to move between, and for one’s desires to remain inconsistent.

78I go back again and again to the archive, to the work. I hold my breath in the sound booth, stroke oily paint swatches on pages of crinkled paper. I sense how Graham and Chadwick touched and am in turn touched by the residues of their activities, their late-night talking. This touching “opens my body up, opens me up”, to borrow Ahmed’s phrase.80 The pleasures offered by these artworks point to—even if they cannot fully embody—what is expansive and relational. They encourage more ways of being with one another. In this sense, Fallen Angel and Lofos Nymphon generate Bryan-Wilson’s articulation of queer meanings outlined at the beginning of this article; both artworks are fraught with contradiction, proposing new structures of desire while simultaneously fostering discomfort.

80Coming to terms with paradoxes such as these feels an inevitable part of writing queer art history. In this endeavour, as Susanne Huber has articulated, “a certain dichotomy between authority on the one side and transgression on the other is evident”.81 And yet, perhaps the bisexual perspectives revealed here offer an indeterminate third option, one that must occupy an ambivalent position of both/and rather than pick sides. In its compilation and editorial framing, this special issue contributes to ongoing efforts in art history to construct a queer canon. Significantly, the word “canon” stems from the Greek kanōn, meaning rule or standard. To be tested against a standard, something must register in the first place. As this article has explored, the bisexual perspectives of Chadwick and Graham failed to do so in the 1980s, and their lack of coherence or visibility feels at odds with the public desires and political struggles that characterise many (but not all) queer experiences of that decade. I want to argue that their failure to meet this standard may be one way of constructing a queer canon that resists art history’s homogenising tendencies. Canons are driven by a conservative impulse to order and legislate, and often serve to consolidate power, but canons can also be orientation devices, means of finding ideas and, of course, each other.

81In the early stages of my research, a brief citation in Marina Warner’s study of Chadwick’s The Oval Court filled me with pleasure on account of its politeness. Warner points to Graham as a potential influence, describing how Chadwick was “looking carefully at the Northern Irish artist”.82 As this article has brought to light, she wasn’t just looking—oh, how they touched!

82Acknowledgements

Thank you to Roberta M. Graham for being so generous and supportive of this work. The archivists Kathryn Tollervey at the Photographers’ Gallery and Errin Hussey at Henry Moore Institute provided helpful assistance during the research phase. Without the creative and loving friendship of Alice Hattrick I would not have been able to write this article; our early archival experiments were my own “lightning spark”. I am also indebted to the editors of this special issue, the team at British Art Studies, and the anonymous readers whose feedback led to important clarifications and additions. Anna Bunting-Branch, Laura Guy, and Ed Webb-Ingall gave me confidence during the development process, and their comments have shaped this article. Finally, thank you to Amy Daniel and Stuart Middleton for their insight and for propelling new structures of desire with me.

About the author

-

Dr Naomi Pearce is a writer and curator. Her research explores the materiality of artistic production and gentrification as they intersect with feminist legacies, death and discourses of desire. She has curated exhibitions and events at the Warburg Institute, Raven Row, Barbican, Matt’s Gallery, and elsewhere. Alongside her criticism for Art Monthly, LA Review of Books, and The White Review, she has written essays for the forthcoming edited volumes Gestures: A Body of Work, edited by Alice Butler, Nell Osborne and Hilary White (Manchester University Press) and Grassroots Artmaking: Political Struggle and Activist Art in the UK, 1960–Present (Bloomsbury). From 2018 to 2022 she was a member of the Rita Keegan Archive Project, whose activities included an exhibition at South London Gallery and the publication Mirror Reflecting Darkly (MIT Press). She was awarded a practice-based PhD, funded by the Scottish Graduate School for Arts & Humanities (SGSAH), at the University of Edinburgh, where she developed her first novel, Innominate (MOIST Books, 2023). She teaches interdisciplinary practice at Aberystwyth University.

Footnotes

-

1

Shirley Read, “Roberta Graham Interviewed by Shirley Read”, Tape 6 (C459/123), 2000, Oral History of British Photography, London. ↩︎

-

2

José Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (New York: NYU Press, 2019), 65. ↩︎

-

3

Julia Bryan-Wilson, “Julia Bryan Wilson in Conversation with Lauren O’Neill-Butler”, November Mag 6 (August 2023), https://www.novembermag.com/content/julia-bryan-wilson. ↩︎

-

4

Clare Hemmings, “Bisexual Theoretical Perspectives: Emergent and Contingent Relationships”, in The Bisexual Imaginary: Representation, Identity and Desire, ed. Bi Academic Intervention (London: Cassell, 1997), 14. ↩︎

-

5

Hemmings, “Bisexual Theoretical Perspectives”, 4. ↩︎

-

6

Elizabeth Freeman, Time Binds: Queer Temporalities, Queer Histories (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010), xvi. ↩︎

-

7

Freeman, Time Binds, xii. ↩︎

-

8

Freeman, Time Binds, 14. ↩︎

-

9

Freeman, Time Binds, 96. ↩︎

-

10

Sara Ahmed, The Cultural Politics of Emotion (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2004), 165. ↩︎

-

11

Cathy de Monchaux in Louisa Buck, mod., “The Legacy of Helen Chadwick”, panel discussion, Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, 9 March 2016, YouTube video, 1:28:34, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cfSYkrGxhEw. ↩︎

-

12

Buck, mod., “The Legacy of Helen Chadwick”. ↩︎

-

13

Linda Nochlin, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?”, ARTnews, January 1971, https://www.artnews.com/art-news/retrospective/why-have-there-been-no-great-women-artists-4201. ↩︎

-

14

Nochlin, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” ↩︎

-

15

Muñoz, Cruising Utopia, 6. ↩︎

-

16

For a brief but comprehensive overview, see Serena Anderlini-D’Onofrio and Jonathan Alexander, “Bisexuality and Queer Theory: An Introduction”, in Bisexuality and Queer Theory: Intersections, Connections and Challenges, ed. Jonathan Alexander and Serena Anderlini-D’Onofrio (Abingdon: Routledge, 2012), 1–19. ↩︎

-

17

Cherry Smyth, Lesbians Talk Queer Notions (London: Scarlet Press, 1992), 33. ↩︎

-

18

Clare Hemmings, Bisexual Spaces: A Geography of Sexuality and Gender (New York: Routledge, 2002), 42; Hemmings, “Bisexual Theoretical Perspectives”, 21. ↩︎

-

19

Roberta M. Graham, “Fallen Angel”, https://robertagraham.com/fallen-angel/. ↩︎

-

20

Roberta M. Graham and Ken Hollings, “Fallen Angel”, artist statement (1986), emailed to author, 17 December 2023. ↩︎

-

21

Percy Bysshe Shelley, “Fragments (To Thirst and Find No Fill …)”, in Lyrics & Shorter Poems, vol. 1 of The Poetical Works of Percy Bysshe Shelley, ed. Ernest Rhys (London: J. M. Dent, 1913), 201. ↩︎

-

22

See Steven Angelides, A History of Bisexuality (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001). Angelides maps this terrain and challenges its construction. ↩︎

-

23

Roberta M. Graham, telephone conversation with author, 14 February 2024. ↩︎

-

24

Graham, telephone conversation with author. ↩︎

-

25

Caroline Evans and Lorraine Gamman, “The Gaze Revisited, or Reviewing Queer Viewing”, in Queer Romance: Lesbians, Gay Men and Popular Culture, ed. Paul Burston and Colin Richardson (London: Routledge, 1995), 35. ↩︎

-

26

Reina Lewis, “Looking Good: The Lesbian Gaze and Fashion Imagery”, Feminist Review 55, no. 1 (Spring 1997), 96, DOI:10.1057/fr.1997.6. ↩︎

-

27

Waldemar Januszczak, “Body and Soul”, Guardian, 22 July 1987, press cutting in Photographers’ Gallery Archive. ↩︎

-

28

Sarah Kent, review of The Body Politic: Re-presentations of Sexuality, Time Out, 22–29 July 1987; Liz Heron, “Anatomy Lessons”, review of The Body Politic, New Statesman, 1 July 1987; and Clive Lancaster, review of The Body Politic, British Journal of Photography, 21 August 1987—all press cuttings in Photographers’ Gallery Archive. ↩︎

-

29

Lancaster, review of The Body Politic. ↩︎

-

30

Alexandra Noble, “The Body Politic: Re-presentations of Sexuality”, press release, Photographers’ Gallery, 1987, Papers of Helen Chadwick, box 37, Henry Moore Institute, Leeds. ↩︎

-

31

Emmanuel Cooper, review of The Body Politic: Re-presentations of Sexuality, Gay Times 106 (July 1987): 71, press cutting in Photographers’ Gallery Archive. ↩︎

-

32

Januszczak, “Body and Soul”. ↩︎

-

33

Laura Mulvey, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema”, Screen 16, no. 3 (Autumn 1975): 6–18. ↩︎

-

34

Anne Williams, “Untitled”, Ten.8 25 (Summer 1987): 11. ↩︎

-

35

Gerard Koskovich, “Honey Lee Cottrell (1946–2015): Lesbian Photographer, Filmmaker and Pioneer of Women’s Erotica, Dies at Age 60”, Feminine Moments, 24 September 2015, https://www.femininemoments.dk/blog/obituary-honey-lee-cottrell-1946-2015/. ↩︎

-

36

Hemmings, “Bisexual Theoretical Perspectives”, 14. ↩︎

-

37

Helen Chadwick, Notebooks (1987–96), Papers of Helen Chadwick, 2003.19/E/8, 37. ↩︎

-

38

Jack Halberstam, Skin Shows: Gothic Horror and the Technology of Monsters (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1995), 36. ↩︎

-

39

Freeman, Time Binds, 96–97. ↩︎

-

40

Susan Sontag, Notes on “Camp” (London: Penguin, 2018), 7. ↩︎

-

41

Freeman, Time Binds, 68. ↩︎

-

42

Freeman, Time Binds, 68. ↩︎

-

43

See Merl Storr, “Editor’s Introduction”, in Bisexuality: A Critical Reader (London: Routledge, 1999), 1–12. ↩︎

-

44

Roberta M. Graham, “Projected Rituals, an Investigation of the Works of Roberta Graham: An Interview with André Stitt”, Circa 28 (May–June 1986): 18. ↩︎

-

45

Muñoz, Cruising Utopia, 21. ↩︎

-

46

Bisexual Lives came out of the second Politics of Bisexuality Conference, held in London at the Lesbian and at Community Centre in 1985. ↩︎

-

47

Off Pink Collective, Bisexual Lives (London: Off Pink Publishing, 1988), https://bistuff.org.uk/bisexual-lives-1988/friends/. ↩︎

-

48

Read, “Roberta Graham Interviewed by Shirley Read”. ↩︎

-

49

Graham, telephone conversation with author. ↩︎

-

50

Graham, telephone conversation with author. ↩︎

-

51

Clare Hemmings and Susan Rudy, “‘I Don’t Know What Gender Is, but I Do, and I Can, and We All Do’: An Interview with Clare Hemmings”, European Journal of Women’s Studies 26, no. 2 (May 2019): 218, DOI:10.1177/1350506819833240. ↩︎

-

52

Christmas card from Roberta M. Graham to Helen Chadwick, Papers of Helen Chadwick, 2003.19, box 99, folder HC: Christmas Cards & Lists, Henry Moore Institute, Leeds. ↩︎

-

53

Correspondence with Alexandra Noble, 25 April 1987, Papers of Helen Chadwick, 2003.19, box 37. ↩︎

-

54

Helen Chadwick, “Lines that Severed, Bind” (first draft), n.d., Papers of Helen Chadwick, 2003.19, box 37. ↩︎

-

55

Chadwick, “Touching Egg” (third draft), n.d., Papers of Helen Chadwick, 2003.19, box 37. ↩︎

-

56

Noble, “The Body Politic”, press release; Michael du Plessis, “Blatantly Bisexual; or, Unthinking Queer Theory”, in RePresenting Bisexualities: Subjects and Cultures of Fluid Desire, ed. Donald E. Hall and Maria Pramaggiore (New York: NYU Press, 1996), 19. ↩︎

-

57

See Mary Horlock, “Between a Rock and a Soft Place”, in Helen Chadwick, ed. Mark Sladen (Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz), 33–46. ↩︎

-

58

Marina Warner, The Oval Court (London: Afterall Books, 2022), 97. ↩︎

-

59

Emma Cocker, “Indifference in Difference: An Interview with Helen Chadwick”, Women’s Art Magazine 71 (August–September 1996): 24. ↩︎

-

60

Cocker, “Indifference in Difference”, 23. ↩︎

-

61

Helen Chadwick, writing and preparatory material for Lofos Nymphon, Papers of Helen Chadwick, 2003.19, box 37. ↩︎

-

62

Freeman, Time Binds, xiii. ↩︎

-

63

Helen Chadwick, “On Loosing [sic] Name and Home” (third draft), Papers of Helen Chadwick, 2003.19, box 37. ↩︎

-

64

Chadwick, quoted in Mark Sladen, “A Red Mirror”, in Helen Chadwick, ed. Mark Sladen (Ostfildern-Ruit: Hatje Cantz), 18. ↩︎

-

65

Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography (New York: Hill & Wang, 1982), 81. ↩︎

-

66

Helen Chadwick, in BBC, Open Space: Artists in Residence, series 11, episode 6, aired 25 April 1988, Community Programme Unit. ↩︎

-

67

Chadwick, “On Loosing Name and Home”. ↩︎

-

68

Chadwick, “On Loosing Name and Home”. ↩︎

-

69

Jo Eadie, “Extracts from Activating Bisexuality: Towards a Bi/Sexual Politics (1993)”, in Bisexuality: A Critical Reader, ed. Merl Storr, 134. ↩︎

-

70

Eadie, Activating Bisexuality, 134. ↩︎

-

71

Helen Chadwick, “Withdrawal: Object, Sign, Commodity”, in Architecture, Space, Painting, ed. Andrew Benjamin (London: Academy Editions, 1992), 71. ↩︎

-

72

Sara Ahmed, Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2006), 12. ↩︎

-

73

Ahmed, Queer Phenomenology, 19. ↩︎

-

74

Chadwick, quoted in Iain Gale, “Helen Chadwick Talking to Iain Gale”, Modern Painters 7, no. 3 (Autumn 1994): 107. ↩︎

-

75

Marjorie Allthorpe-Guyton, “Helen Chadwick: Of Mutability”, Art Monthly 100 (October 1986): 18. ↩︎

-

76

Chadwick, “Withdrawal: Object, Sign, Commodity”, 69. ↩︎

-

77

Ahmed, The Cultural Politics of Emotion, 147. ↩︎

-

78

Graham, telephone conversation with the author. ↩︎

-

79

Graham, telephone conversation with the author. ↩︎

-

80

Ahmed, The Cultural Politics of Emotion, 164. ↩︎

-

81

Susanne Huber, “Unfit Art History: Queering the Study of Art”, De Gruyter Conversations, 7 March 2024, https://blog.degruyter.com/unfit-art-history-queering-the-study-of-art/. ↩︎

-

82

Warner, The Oval Court, 65. ↩︎

Bibliography

Ahmed, Sara. The Cultural Politics of Emotion. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2004.

Ahmed, Sara. Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2006.

Alexander, Jonathan, and Serena Anderlini-D’Onofrio, eds. Bisexuality and Queer Theory: Intersections, Connections and Challenges. Abingdon: Routledge, 2012.

Allthorpe-Guyton, Marjorie. “Helen Chadwick: Of Mutability”. Art Monthly 100 (October 1986): 18–19.

Anderlini-D’Onofrio, Serena, and Jonathan Alexander, eds. “Bisexuality and Queer Theory: An Introduction”. In Bisexuality and Queer Theory: Intersections, Connections and Challenges, edited by Alexander, Jonathan, and Serena Anderlini-D’Onofrio, 1–19. Abingdon: Routledge, 2012.

Angelides, Steven. A History of Bisexuality. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001.

Barthes, Roland. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. New York: Hill & Wang, 1982.

BBC. Open Space: Artists in Residence. Series 11, episode 6. 32 minutes. Community Programme Unit. Aired 25 April 1988.

Bryan-Wilson, Julia. “Julia Bryan Wilson in Conversation with Lauren O’Neill-Butler”. November Mag 6 (August 2023). https://www.novembermag.com/content/julia-bryan-wilson.

Buck, Louisa, moderator. “The Legacy of Helen Chadwick”. Panel discussion, Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, 9 March 2016. YouTube video, 1:28:34. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cfSYkrGxhEw.

Chadwick, Helen. Notebooks (1987–96). Papers of Helen Chadwick, 2003.19/E/8. Henry Moore Institute, Leeds.

Chadwick, Helen. Papers of Helen Chadwick. 2003.19, boxes 37, 99. Henry Moore Institute, Leeds.

Chadwick, Helen. “Withdrawal: Object, Sign, Commodity”. In Architecture, Space, Painting, edited by Andrew Benjamin, 68–73. London: Academy Editions, 1992.

Cocker, Emma. “Indifference in Difference: An Interview with Helen Chadwick”. Women’s Art Magazine 71 (August–September 1996): 22–24.

Cooper, Emmanuel. Review of The Body Politic: Re-presentations of Sexuality. Gay Times 106 (July 1987): 71. Press cutting in Photographers’ Gallery Archive.

du Plessis, Michael. “Blatantly Bisexual; or, Unthinking Queer Theory”. In RePresenting Bisexualities: Subjects and Cultures of Fluid Desire, edited by Donald E. Hall and Maria Pramaggiore, 19–54. New York: NYU Press, 1996.

Eadie, Jo. “Extracts from Activating Bisexuality: Towards a Bi/Sexual Politics (1993)”. In Bisexuality: A Critical Reader, edited by Merl Storr, 119–37. London: Routledge, 1999.

Evans, Caroline, and Lorraine Gamman. “The Gaze Revisited, or Reviewing Queer Viewing”. In A Queer Romance: Lesbians, Gay Men and Popular Culture, edited by Paul Burston and Colin Richardson, 13–56. London: Routledge, 1995.

Freeman, Elizabeth. Time Binds: Queer Temporalities, Queer Histories. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010.

Gale, Iain. “Helen Chadwick Talking to Iain Gale”. Modern Painters 7, no. 3 (Autumn 1994): 106–8.

Graham, Roberta M. “Fallen Angel”. https://robertagraham.com/fallen-angel/.

Graham, Roberta M. “Projected Rituals, an Investigation of the Works of Roberta Graham: An Interview with André Stitt”. CIRCA 28 (May–June 1986): 15–18.

Graham, Roberta M., and Ken Hollings. Artist statement for Fallen Angel. Document (1986) emailed to author, 17 December 2023.

Halberstam, Jack. Skin Shows: Gothic Horror and the Technology of Monsters. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1995.

Hemmings, Clare. Bisexual Spaces: A Geography of Sexuality and Gender. New York: Routledge, 2002.

Hemmings, Clare. “Bisexual Theoretical Perspectives: Emergent and Contingent Relationships”. In The Bisexual Imaginary: Representation, Identity and Desire, edited by Bi Academic Intervention, 14–37. London: Cassell, 1997.

Hemmings, Clare, and Susan Rudy, “‘I Don’t Know What Gender Is, but I Do, and I Can, and We All Do’: An Interview with Clare Hemmings”. European Journal of Women’s Studies 26, no. 2 (May 2019): 211–22. DOI:10.1177/1350506819833240.

Heron, Liz. “Anatomy Lessons”, review of The Body Politic. New Statesman, 1 July 1987, 23–24. Press cutting in Photographers’ Gallery Archive.

Horlock, Mary. “Between a Rock and a Soft Place”. In Helen Chadwick, edited by Mark Sladen, 33–46. Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz, 2004.

Huber, Susanne. “Unfit Art History: Queering the Study of Art”. De Gruyter Conversations, 7 March 2024. https://blog.degruyter.com/unfit-art-history-queering-the-study-of-art/.

Januszczak, Waldemar. “Body and Soul”, Guardian, 22 July 1987. Press cutting in Photographers’ Gallery Archive.

Kent, Sarah. Review of The Body Politic: Re-presentations of Sexuality. Time Out, 22–29 July 1987. Press cutting in Photographers’ Gallery Archive.

Koskovich, Gerard. “Honey Lee Cottrell (1946–2015): Lesbian Photographer, Filmmaker and Pioneer of Women’s Erotica, Dies at Age 60”. Feminine Moments, 24 September 2015. https://www.femininemoments.dk/blog/obituary-honey-lee-cottrell-1946-2015/.

Lancaster, Clive. Review of The Body Politic. British Journal of Photography, 21 August 1987. Press cutting in Photographers’ Gallery Archive.

Lewis, Reina. “Looking Good: The Lesbian Gaze and Fashion Imagery”. Feminist Review 55, no. 1 (Spring 1997): 92–109. DOI:10.1057/fr.1997.6.

Mulvey, Laura. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema”. Screen 16, no. 3 (Autumn 1975): 6–18.

Muñoz, José Esteban. Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity. New York: NYU Press, 2019.

Noble, Alexandra. “The Body Politic: Re-presentations of Sexuality”. Press release, Photographers’ Gallery, 1987. Papers of Helen Chadwick, box 37. Henry Moore Institute, Leeds.

Nochlin, Linda. “From 1971: Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” ARTnews, 30 May 2015. https://www.artnews.com/art-news/retrospective/why-have-there-been-no-great-women-artists-4201/.

Off Pink Collective. Bisexual Lives. London: Off Pink Publishing, 1988. https://bistuff.org.uk/bisexual-lives-1988/.

Read, Shirley. “Roberta Graham Interviewed by Shirley Read”. Tape 6 (C459/123), 2000. Oral History of British Photography, British Library, London.

Shelley, Percy Bysshe. Lyrics & Shorter Poems. Vol. 1 of The Poetical Works of Percy Bysshe Shelley, edited by Ernest Rhys. London: J. M. Dent, 1913.

Sladen, Mark. “A Red Mirror”. In Helen Chadwick, edited by Mark Sladen, 13–32. Ostfildern-Ruit: Hatje Cantz, 2004.

Smyth, Cherry. Lesbians Talk Queer Notions. London: Scarlet Press, 1992.

Sontag, Susan. Notes on “Camp”. London: Penguin, 2018.

Storr, Merl. “Editor’s Introduction”. In Bisexuality: A Critical Reader, 1–12. London: Routledge, 1999.

Warner, Marina. The Oval Court. London: Afterall Books, 2022.

Williams, Anne. “Untitled”. Ten.8 25 (Summer 1987): 11.

Imprint

| Author | |

|---|---|

| Date | 14 July 2025 |

| Category | Article |

| Review status | Peer Reviewed (Double Blind) |

| License | Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) |

| Downloads | PDF format |

| Article DOI | https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-27/npearce |

| Cite as | Pearce, Naomi. “‘More than Friends’: Bisexual Perspectives in Roberta M. Graham’s Fallen Angel and Helen Chadwick’s Lofos Nymphon.” In British Art Studies: Queer Art in Britain since the 1980s (Edited by Fiona Anderson, Flora Dunster, Theo Gordon and Laura Guy), by Fiona Anderson, Flora Dunster, Theo Gordon, and Laura Guy. London and New Haven: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art and Yale Center for British Art, 2025. https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-27/npearce. |