Ecstatic Antibodies

Ecstatic Antibodies: Art, Activism, and HIV/AIDS in “British” Art History

By Theo Gordon

Abstract

Opening at Impressions Gallery of Photography in January 1990, the exhibition Ecstatic Antibodies: Resisting the AIDS Mythology, curated by Tessa Boffin and Sunil Gupta, was a landmark effort to use artistic practices to intervene in the politics of representation of AIDS in the United Kingdom. While Ecstatic Antibodies has since faded from art-historical memory, this article resists the effort to recuperate it into a “canon” of “AIDS art”, reading instead its archival fragments as testifying to the contingent nature of artistic responses to the political crisis of HIV/AIDS in Britain. By charting the development of the exhibition out of the problem space of the late 1980s, its controversial censorship, and the politics of vision and reproduction informing much of the work contained within it, the article contends that the form and fate of Ecstatic Antibodies offers new ways to conceive the history of art and HIV in Britain, and to reconceptualise gay, lesbian, and Black coalition building just prior to the provisional reclamation of the term “queer” in sexual and cultural politics.

“British Art”, HIV, and Contingency

Is there a significant body of art made in the United Kingdom in response to the HIV epidemic? The art critic Charles Darwent has recently suggested that in Britain “it was politeness that equalled death”, arguing that the general unwillingness of artists, aside from Derek Jarman, to declare that they were living with AIDS has created “a strange absence” in gallery displays whereby, in “any museum of modern British art more than 40 years on from the naming of AIDS”, it appears visually that “the epidemic might never have happened”.1 Darwent’s well-meaning commentary is indicative of the historic and ongoing blindnesses that currently inhibit appreciation of the wide and diverse field of artistic responses to HIV/AIDS in Britain. The seminal exhibition of the time that he highlights is the New York-based Nan Goldin’s Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing (1989), and his list of relevant artists centres on individuals, including Jarman, Mario Dubsky, David Robilliard, Andrew Heard, and Rotimi Fani-Kayode; the role of grassroots and group-led work is obscure.

1Meanwhile, “British” work has occupied a marginal and equivocal place in recent European survey exhibitions of art and HIV, in contrast to the still ascendent tendency to privilege American and French production (alongside a smattering of work from Africa). At the 2023 exhibition In the Days of AIDS: Artworks, Narratives, Interweavings at La Musée d’Art Moderne et Contemporain de la Ville de Strasbourg—the most recent exhibition in Europe attempting to assess forty years of art and cultural production informed by HIV—work from the United Kingdom was limited to Jarman’s oft-shown final film, Blue (1993), and to popular music, including Soft Cell’s cover of “Tainted Love” (Non-stop Erotic Cabaret, 1981) and an excerpt of Neneh Cherry’s video for “I’ve Got You under My Skin” from the first Red Hot + Blue (1990) charity album.2 Out of a total of forty artists and collectives represented in Exposées: D’après Ce que le sida m’a fait d’Elisabeth Lebovici at Palais de Tokyo, Paris, in 2023, the curator François Piron included only a selection of Jarman’s late paintings and Black Audio Film Collective’s portrait of Donald Rodney, Three Songs on Pain, Time and Light (1995), as well as recent work by Jesse Darling; among fifty-six other artists, the curators Tommaso Sperreta and Ana María Bresciani included historic work by Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Sunil Gupta, and Tessa Boffin in Every Moment Counts: AIDS and Its Feelings at Henie Onstad Kunstsenter in Høvikkoden, Norway, in 2022; and Raphael Gygax showed contemporary work by Prem Sahib and Edward Thomasson among the forty-four artists he featured in United by AIDS: An Exhibition about Loss, Remembrance, Activism and Art in Response to HIV/AIDS at Migrosmuseum für Gegenwartskunst in Zürich in 2019.3 In his book L’art en sida, 1981–1997 (2021), Thibault Boulvain devotes some space to Gilbert & George and Jarman, while in Ce que le sida m’a fait: Art et activisme à la fin du XXe siècle (2017) Elisabeth Lebovici briefly mentions a handful of artists, including Helen Chadwick, Hamad Butt, and Isaac Julien.4 Across all these projects, in juxtaposition to the space given to American and French work, the overall impression is that the artistic response to HIV in Britain was minor and of minimal international significance.

2In this article I consider an art exhibition, Ecstatic Antibodies: Resisting the AIDS Mythology (1990–93), conceived at the height of the epidemic by the London-based photographers and cultural activists Tessa Boffin and Sunil Gupta. Notably, they chose to show only artists working in Britain, countering the already prevailing cultural dominance of American practices at the time.5 In considering this exhibition in detail, my purpose is not to insist that a range of British work has been neglected, nor to demand its inclusion in a notional canon of “HIV/AIDS art” but rather to explore it in relation to questions that have animated British Art Studies from its outset. To what extent is there a “British art” responding to HIV?6 Or, rather, how might attending to the specificities of the work featured in Ecstatic Antibodies contribute to an understanding of the fundamental contingency of art and visual culture in response to a still unfolding epidemic? In 1992 Simon Watney wrote of the necessary ephemerality of response and strategy in a constantly changing crisis: “one is always trying to connect the past to the present, the short-term to the mid-term, the detail to the whole. Always one is trying to develop effective policies in constantly changing circumstances, and to anticipate future needs. This is what contingency means”.7

5It is this sense of the contingent that I want to draw on, as well as its immensely challenging implications for the writing of art history. In the nebulous crisis of HIV/AIDS, with the grounds and assumptions of treatment, prevention, and care shifting all the time, the social and political meaning and efficacy of works of art and visual culture also constantly shift. As Hamad Butt put it at the time, “what is so remarkable is the symbol-inducing power of this illness and the migrating social consensus about its meaning”.8 Responses essential to a particular moment may therefore easily disappear in the next; the now iconic status of activist graphics by New York-based groups such as the Silence = Death collective and Gran Fury belies the contingency of their emergence. Ecstatic Antibodies emerged out of a very specific moment in the British epidemic, one defined by coalition building between Black, gay, and lesbian artists and by provocative engagement with the politics of vision and forms of image reproduction in the context of campaigns to promote safer sex. It was the vexed and mutating political landscape it entered into, as well as its material constraints, that has informed its obscure status in art history.

8It is worth noting at the outset that HIV provides a challenge to the global turn in art history as a context in which understanding national frameworks is crucial.9 Since the 1980s, scholars such as Watney and Peter Aggleton have insisted, following the example set by the field of epidemiology, that viewing HIV/AIDS as a single uniform epidemic is misleading.10 Rather, the varied prevalence of modes of transmission and availability of treatments across different social, political, and medical contexts means that HIV must be understood, even at a national level, as “a multiplicity of overlapping epidemics evolving with different dynamics in different social circumstances”.11 Artistic responses to HIV are similarly and necessarily conditioned (which is not to say delimited) by the epidemic’s national and local circumstances, and there are clear limitations to surveys that attempt to generalise outside any national frame. Scholarship on HIV in the humanities, including art history, has been remarkably slow to metabolise this fact; the edited collection AIDS and the Distribution of Crises (2020) is an important recent attempt to examine the uneven patterning of the epidemic through globalisation, challenging the prevailing tilt to the United States in European work on HIV/AIDS.12

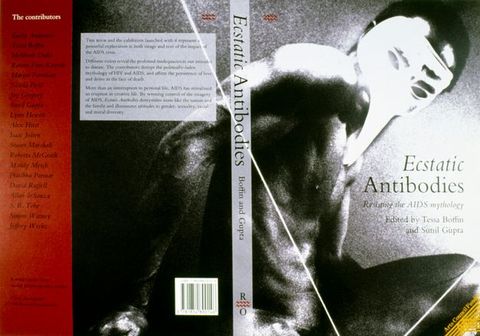

9The dispersed nature of the archival traces of Ecstatic Antibodies are a productive starting point to challenge that tilt. Jackson Davidow has written that Ecstatic Antibodies “was difficult to place—and remains quite overlooked in scholarship”, and I think it is crucial to stay with that difficulty and the challenge of fully recuperating the exhibition’s place.13 Fanned by the controversy of censorship, the exhibition had an extraordinarily lengthy tour, opening at Impressions Gallery of Photography in York in January 1990, who then managed its tour to IKON Gallery in Birmingham, Chapter Arts Centre in Cardiff, Battersea Arts Centre in London, Street Level in Glasgow, La Maison de la Culture Frontenac in Montreal, the Health Authority in Worcester (UK), the Gallery of Photography in Dublin, and finishing at Lighthouse Media Centre in Wolverhampton in 1993.14 Yet, since it closed its doors, understanding what this exhibition actually looked like has proved extremely difficult. Boffin and Gupta deliberately designed the accompanying book, Ecstatic Antibodies, to have an alternative life to the exhibition; eschewing a straightforward catalogue of works, it includes a broader range of critical and creative responses to HIV by the artists and by other writers, interspersed with selected images from the show in black and white plates. The book was very successful, selling out its entire print run and immediately appearing in the footnotes of emergent scholarly and activist texts on the AIDS crisis.15 However, the material constraints and exigencies of cultural activism at the time resulted in a book that has, in a sense, obscured the exhibition’s appearance. The exhibition archive is fractured and incomplete and therefore opens onto how identities were, at the time, being rethought as contingent and provisional and produced through representation.

13

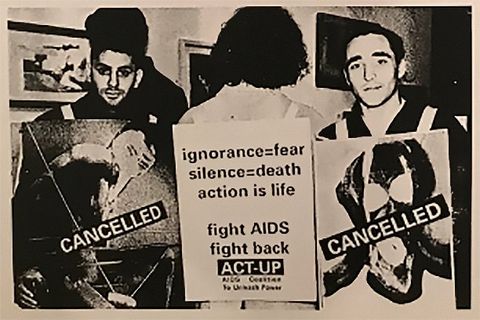

Juxtaposing three photographic traces of perhaps the most subsequently famous image produced for the show, Rotimi Fani-Kayode and Alex Hirst’s “The Golden Phallus”, one Cibachrome print in their epic multimedia installation Metaphysick: Every Moment Counts (1989) dramatises the instability of the archive.16 On 1 November 1989, Elizabeth Fidlon, managing editor at Rivers Oram Press, wrote to Paul Wombell, the director of Impressions, to ask for a template of the cover design for the Ecstatic Antibodies book (fig. 1). “The cover will be a sepia brown with red lettering”, she writes, explaining that they opted not to reproduce “The Golden Phallus” in colour because “we felt the colour transparency was too rich and didn’t allow the impressionistic treatment we want to give the figure”.17 The bleaching effect of the sepia reproduction, in which the white mask and chiaroscuro light picking out the figure’s muscular body appear tonally indistinct in the all-over lustrous surface, is similarly replicated in a photograph by Andy Gardner reproduced in British Journal of Photography in October 1990, showing members of the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) Manchester protesting Salford City Council’s decision to cancel the booking of Ecstatic Antibodies at Viewpoint Gallery of Photography that autumn (fig. 2).18 In this photograph, the left-hand figure wears a haphazardly assembled sandwich board displaying an enlarged paper photocopy of “The Golden Phallus”, its lower section horizontally ridged through its corrugated cardboard base. By cutting out the eponymous phallus, Rivers Oram’s book cover enacts censorship in its form; neither Gardner nor the protesters he photographed performed a similar excision. Finally, Gupta’s colour transparency of “The Golden Phallus” installed at Impressions as part of the exhibition returns the single photograph to its initial context of production and display (fig. 3).

16

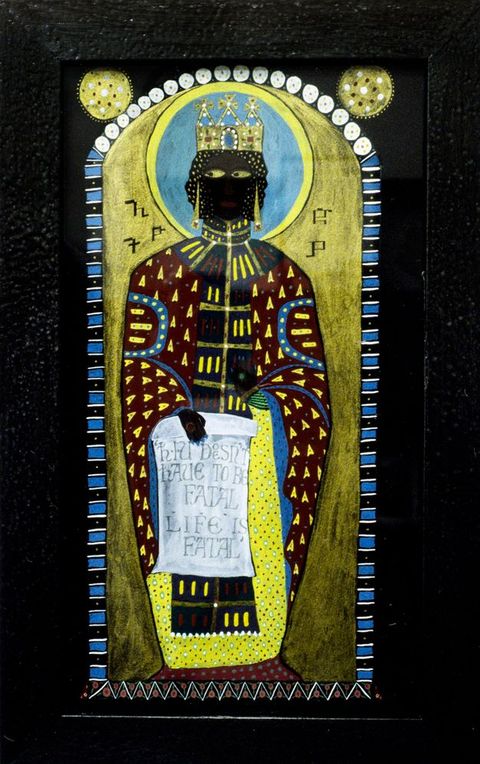

This transparency is filed in Gupta’s slide library at the Gupta+Singh Archive in London and was one that I helped to digitise when working there in 2020.19 It shows “The Golden Phallus” as one of the fragments of Fani-Kayode and Hirst’s Metaphysick, revealing the whole as an epic, intricate, and colourful work and significantly destabilising some subsequent readings of Fani-Kayode’s photography. The studio Cibachrome prints, whose deep tones have been so important to later scholarship, are here interspersed with “praise songs”, ten wooden panels painted in gold gouache, overlaid with sheets of acetate printed with toner showing textual meditations on topics such as William James’s concept of “sciousness”, alternative medicine, and the blues (fig. 4).20 Each praise song begins with a decorative initial, recalling illuminated manuscript traditions from across northern Europe and Coptic Africa. Fani-Kayode and Hirst also include four painted icons, black priest figures bedecked in hybrid Christian and Yoruban iconography revealing an ironic, humorous commentary on the relation between the virus, mortality, and subjective control, for example, “You have to take life more seriously” and “HIV doesn’t have to be fatal / Life is fatal” (figs. 5 and 6). Aware of the book’s monochrome material parameters, for their contribution Fani-Kayode and Hirst opted to print an essay not included in the display and to reproduce a handful of the Cibachrome and silver gelatin prints alongside it, leaving out the praise songs: “The images which are reproduced here are selected from photographs in the exhibition. Bear in mind, however, that the use of colour has been an essential element in the construction of the work. These black and white reproductions can only provide a shadow to tempt or remind”.21 They also refrained from reproducing the icons so as to preserve their intended “gold” quality, stating, “we do not wish to see our gold turned back to lead”.22 Fani-Kayode and Hirst’s refusal to reproduce Metaphysick in print underscores their investment in the auratic quality of its installation. Kobena Mercer has described how, through its subsequent reproduction across various publications and exhibitions, “The Golden Phallus” has become an image that “has acquired a pivotal resonance of its own”.23 It is the final irony that the aura of the original installation is available to us now only in the form of a digitised colour transparency.

19

The pictorial instability of “The Golden Phallus” and the wider exhibition archive is particularly significant in the context of views on representation and identity during this period, particularly in lens-based media. The essays collected in Jonathan Rutherford’s Identity: Community, Culture, Difference, first published in 1990, benchmark how the categorical identity politics of the earlier 1980s, “based on an essentialist notion of a fixed hierarchy of racial, sexual or gendered oppressions”24 and characterised by separatist artistic practice, had begun to give way to an understanding of identity as, in Stuart Hall’s terms, “a ‘production’, which is never complete, always in process, and always constituted within, not outside, representation”.25 Crucial to this newly dynamic view were psychoanalytic and deconstructionist theories of the split, non-identical self, powerfully understood through feminist and postcolonial thought, and inflected by wider neo-Marxist thinking, taking particular inspiration from the Gramsci of the Prison Notebooks, hence Rutherford’s gloss that the “politics of articulation eschews all forms of fixity and essentialism; social, political and class formations do not exist a priori, they are a product of articulation”.26 Even more crucial was how photography, film, and video were being used as speculative spaces of potential, to stage hybrid scenes of encounter, by artists and other cultural workers determined to break out of the rigid constraints and limitations of organising by “personal” identity alone.27 Pratibha Parmar’s work in film and video on Emergence (1986) and Reframing AIDS (1987) is paradigmatic of this impulse; as she commented on the latter work,

2428There are going to be a lot of people who are very surprised that as an Asian woman, I’ve made a film which is looking at AIDS and has not just Black women’s voices but white gay men and white women talking as well. I want to challenge the whole notion of what we as Black lesbian film-makers are supposed to make just by definition of who we are, our identities. People have expectation boundaries of your identity. But we’ve got other things to say, we live in a much broader scenario. Our territory should be as broad as possible.28

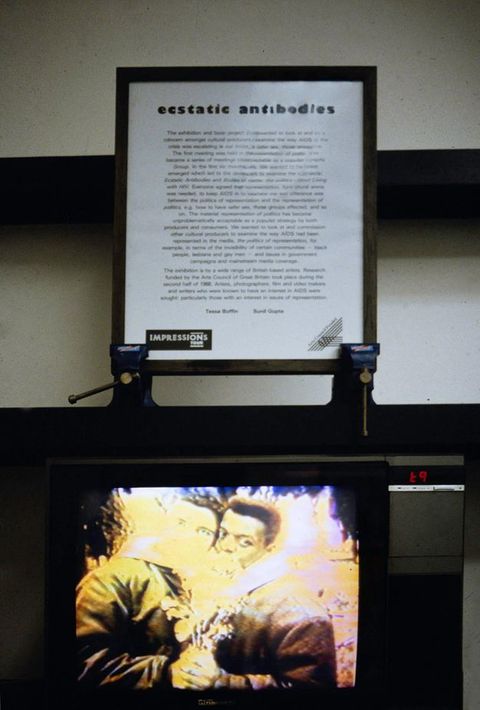

To gaze now into Gupta’s slides of Ecstatic Antibodies on display in York in 1990 is to see a version of a contested past, one defined by effort, tribulation, and censorship, come into focus. The slides show only a handful of the works that were exhibited. A short statement by Boffin and Gupta introducing the exhibition is clamped to a shelf above a television monitor playing Isaac Julien’s important video This Is Not an AIDS Advertisement (1987) (fig. 7). The curators explain that “artists, photographers, film and video makers and writers who were known to have an interest in AIDS were sought” to contribute to the exhibition, “particularly those with an interest in representation”. Boffin and Gupta used the monitor to show five video works, including several already in circulation that had begun to challenge the politics of representation of AIDS, including Parmar’s Reframing AIDS, This Is Not an AIDS Advertisement, and A Plague on You (1985), made by the Lesbian and Gay Media Group for broadcast on BBC Two’s Open Space, alongside two new works: Green Apples (1989) on AIDS and schoolchildren, directed by Emily Andersen and Henrietta Payne, and an early version of Robert Marshall 12′30″ (1991) by Stuart Marshall, a portrait of found footage of the director’s father interwoven with contemporary dialogues on the efficacy of AZT.29

29

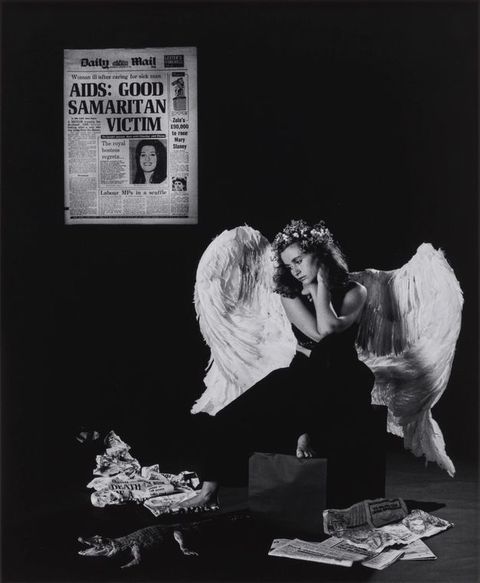

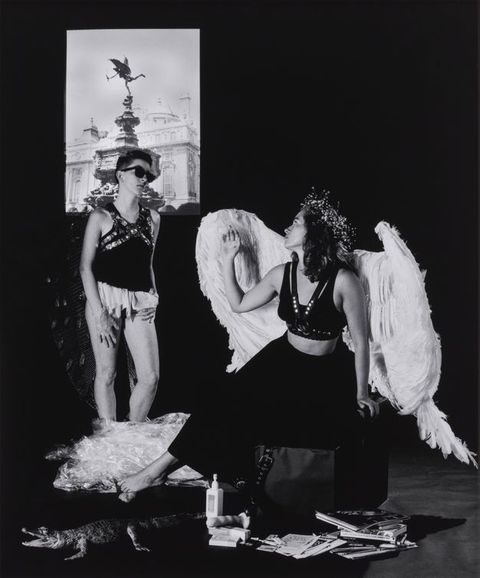

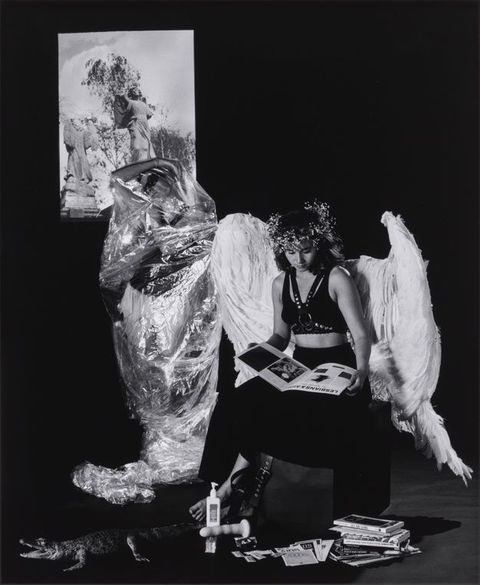

Other transparencies show Boffin’s Angelic Rebels: Lesbians Have Safer Sex (1989), a work delighting in the material seductions of photography and print, which was hung adjacent to David Ruffell’s haunting figurative paintings, made just before his death from AIDS-related complications in June 1989 (figs. 8 and 9). A slide shows the multiple exposures of Joy Gregory’s Fury, Fate and Grace (1989), a work in similar form to her seminal Autoportraits (1989), here a grid of nine “sort of unique” photographs showing, on the bottom row, the three furies; above them, the three fates (Clotho the spinner of the thread of life; Lachesis the measurer of length; and Atropos, the scissors that cut the thread); and, in the top row, the three graces (fig. 10).30 The work is an allegory of mourning, an ascent from fury to grace, with Gregory using her own body to refigure Greek mythology to show black femininity as the maker and marker of its own fates. Gupta’s No Solutions appears in vibrant colour, his sequence contrasting Hindu calendar art in the style of the nineteenth-century painter Raja Ravi Varma, a marker of domestic space in India, alongside silver gelatin prints of Gupta and his boyfriend, Steve Dodd, embracing and stripping naked together in their flat on Bellefields Road in Brixton, against quotes from Autar Singh Paintal, director general of the Indian Council for Medical Research, advocating the banning of Indians having sex with foreign nationals to prevent the spread of HIV. The work dramatises the fraught relationship between the private space of the home and the public space of the nation, the calendar image serving as an ambivalent linchpin of the imagined community. Reflections in the glass frames, held as palimpsestic traces in Gupta’s transparencies, intimate the presence of Al-an deSouza’s photocollage From object of hatred towards the subject of desire (1989), while Emily Andersen’s symbolic triptych of photos and the two curtained-off installations, Nicholas Lowe’s (Safe) Sex Explained (1988) and Lynn Hewitt’s Projections (1989), are not represented at all.

30

My point is that there is not a neat complete representation of the Ecstatic Antibodies exhibition in the archive and that any attempt to account for the importance of both the exhibition and book, then and now, has to begin by reckoning with how identities were beginning to be understood at the time as productions of history, grounded in “the re-telling of the past”, animated by “politics, memory and desire”.31 Hall’s assertion that “cultural identity … is a matter of ‘becoming’ as well as of ‘being’”, that “it belongs to the future as much as to the past”, remains pertinent to our investments in politics, memory, and desire now and to the possible kinds of future we want to create out of the fragments of the past.32 In recent years, the increased normalisation of “queer” as a framing term for cultural projects, funding schemes, and “diversity” initiatives has risked losing sight of its provisional construction as a political response to the pressures and power inequalities of the late 1980s. Ecstatic Antibodies emerged prior to the reappropriation of “queer” as a new organising category for art and cultural politics in Britain, yet in its refusal to silo gay, lesbian, and Black experiences, and its rejection of hegemonic constructions of HIV, it prefigures the expansive aim of queer politics to contest “the overall validity and authenticity of the epistemology of sexuality itself”.33 What follows is not a “comprehensive account” (whatever that might be) of the Ecstatic Antibodies exhibition. First, I set out how the exhibition emerged out of a particular problem space at a particular moment in the British HIV epidemic around 1987, how it developed out of a group working context and along an axis between York and London. I then consider the censorship it faced and how this emerged in reaction to the exhibition’s engagement with the politics of vision (Boffin’s work is the special case study here), and how forms of materiality and mechanical reproduction put to work on the politics of representation were in dialogue with questions of safer sex and the attempt to refashion and differently eroticise sexual behaviour at the height of the epidemic. In pursuing a somewhat disjointed story, moving from the historic context of the exhibition’s emergence to some of the conceptual and material issues that it addressed, I aim to show how Ecstatic Antibodies developed out of a set of problems, to offer possible answers to the seemingly intractable questions of its moment. Both the exhibition, a timely response to difficult circumstance, and its censorship were products of the fundamentally contingent nature of the overlap between AIDS and art. It is in this historical context that I want to reconsider the term “queer” as referring to strategic approach rather than as an inherent identity category and to ask how we can learn from these earlier attempts at problem-solving now.

31

1987: The Problem Space of HIV and Oppositional Cultural Production

Ecstatic Antibodies materialised as a co-production between gay, lesbian, and Black cultural activism in London and the dynamic network of independent photography galleries in the north of England. The key elements of the conjuncture were all in place by 1986.34 In March that year, Margaret Thatcher dissolved the democratically elected Greater London Council (GLC) because of her objection to their (in her view) profligate spending on minority issues using money collected through the local authority rates.35 The GLC, then headed by a leftist faction of Labour under Ken Livingstone, had been a gathering point for artists interested in “issues”- and “identity”-based work, particularly through the Ethnic Minority Unit, committed to antiracist politics as a practice of speaking back to how “race” had been articulated as a discourse of national crisis through the economic turbulence of the 1970s.36 Much ink has been spilled, then and now, on the importance of the GLC as both exceptional in providing rare fiscal support for such community-based work and failing in its inability to negotiate identity politics beyond, in Kobena Mercer’s terms, a “zero-sum game” that unwittingly pitted oppressions against each other in the bid for funding.37 For Sunil Gupta, emerging out of an MA in photography at the Royal College of Art in 1983, “the relationship between local politics and cultural producers was key to the whole Black Arts idea” and was what “eventually saw us at the crossroads of Black photography”, with Reflections of the Black Experience, curated by Monika Baker at Brixton Art Gallery and funded by the GLC, opening just as Thatcher shut the latter down in 1986.38 Rotimi Fani-Kayode, alongside others in the Black Experience show such as Ingrid Pollard, was also part of the constellation of artists supported by local authority work, in his case tutoring in photography for the Inner London Education Authority (ILEA) at adult education institutes in Tower Hamlets, Lambeth, and Putney and Wandsworth, and at Oval House in Kennington.39 The GLC was dissolved just as Baker’s exhibition had gathered Black photographers together, leaving them, as Gutpa describes it, “in the wilderness”, having to regroup and attempt to pitch to other funding bodies such as the Arts Council of Great Britain.40 Ecstatic Antibodies and Autograph ABP emerged out of such efforts, both funded by Barry Lane, the photography officer at the Arts Council of Great Britain.41

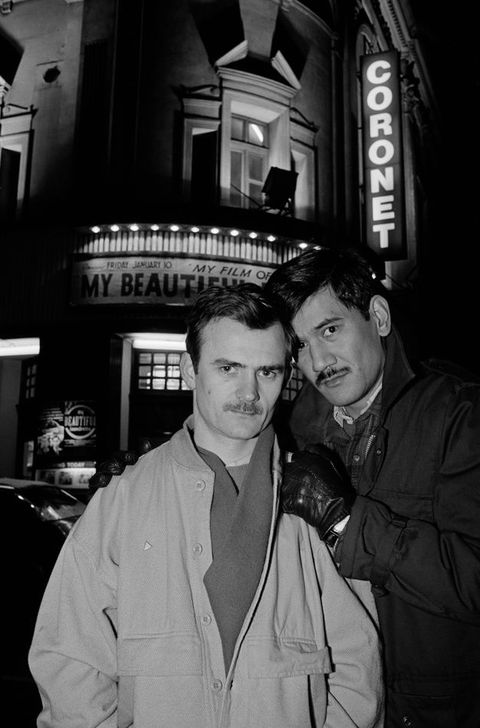

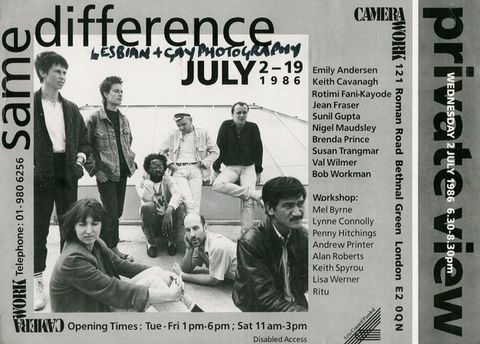

34At the time, Gupta lamented that of the ten photos he showed in Black Experience he had included only one gay picture, of himself and his boyfriend Steve, and that he had “given in to the pressure to marginalise sexual politics in favour of communal politics within the Black framework” (fig. 11).42 Yet, in retrospect, the picture indexes a second key element of the conjuncture, the increasing confidence of artists representing gay experience in their work and the widespread impulse towards coalition and collaboration in response to political pressure. Gupta and Watney had recently worked together on “The Rhetoric of AIDS” (1986), an article for Screen juxtaposing quotations from historians of sexuality, early gay and lesbian studies, and photo theorists with photo reproductions of reporting on AIDS in the European and American press.43 In 1985 Watney began to teach a course on AIDS and representation to his undergraduate students in photographic arts at the Polytechnic of Central London, which at that time included Tessa Boffin (Chris Boot, Jean Fraser, and Jo Spence had also been his students), and in early 1986 he curated a show of student work on AIDS there, one of the first exhibitions anywhere in response to the epidemic.44 Watney would shortly write up his teaching notes as Policing Desire, his foundational book on AIDS and representation. Meanwhile, in July 1986 Gupta and Fraser co-curated Same Difference at Camerawork in Bethnal Green, the first exhibition of out gay and lesbian photographers together, conceived in part as a response to Kate Linker and Jane Weinstock’s Difference: On Representation and Sexuality at the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in 1985 and its psychoanalytically inflected work on sexual difference, which was silent on the question of same-sex desire (fig. 12).45 Same Difference “provide[d] a place to look at our own image” and amassed a wide range of photo practice, from Bob Workman’s photojournalism for Gay News (1972–83), Fani-Kayode’s street and studio work, and Fraser’s staged series But Are There Any in Tower Hamlets? (1985), of lesbians before local landmarks in the borough, to other work by Gupta, Keith Cavanagh, Nigel Maudsley, Brenda Prince, Susan Trangmar, and Val Wilmer.46 By 1986, multiple strands of coalitional work between gay, lesbian, and Black artists had been established, laying the groundwork on which the AIDS and Photography group would build.

42

The final key element was the historical shifts in the AIDS crisis and the government’s response to it in the winter of 1986–87. After five years of “government sloth” and neglect, as grassroots gay activists and healthcare professionals worked to try and forge a coherent approach to the epidemic “from below”, the Tory government began to pay attention to AIDS in 1985 as it became clear that it had “ceased to be a minority problem, or a problem of troublesome minorities”.47 The paradoxes of the subsequent government response were well critiqued by Watney at the time, and directly informed the curatorial frame of Ecstatic Antibodies. Norman Fowler, the health secretary, worked closely with the advertising agency TBWA and another ad man, Sami Harari, alongside the chief medical officer, Donald Acheson, on the “AIDS: Don’t Die of Ignorance” campaign, opting early on to adopt a “general population” focus rather than develop a range of materials directed at different risk groups.48 The result was a campaign that encoded implicit differences between minorities and the “general population”, and did little to address the specific needs of those most devastated by AIDS already (“At the moment the infection is mainly confined to relatively small groups of people in this country. But it is spreading”). As Watney put it, “millions of pounds have been squandered in a face-saving exercise which directs its crude, loud-hailing machinery at nobody in particular, least of all towards those who are in most need of a positive health education programme”.49 In retrospect, in Jeffrey Weeks’s reckoning, the after-effects of the government campaign in tandem with local and community responses does, however, seem to have kept the epidemic on a relatively small scale in the United Kingdom.50 Yet such a perspective was not available at the time, and those excluded from the campaign’s purview—“black Africans, injecting drug users, workers in the sex industry, the “promiscuous”, and above all gay men”—were both rendered hyper-visible as stigmatised carriers of disease and yet also ignored and left to produce community-specific materials.51 The campaign also contributed to a wider crisis of fear and isolation in affected communities, particularly lesbians and gay men.52 Hence Boffin and Gupta’s claim in the introduction to Ecstatic Antibodies that they “wanted to look at and commission other cultural producers to examine the way AIDS has been represented in the media, the politics of representation, in terms of the in/visibility of certain communities—Black people, lesbians and gay men—and issues in government campaigns and mainstream media coverage”.53 It was awareness of the severe limitations and damaging effects of government advertising, together with the burgeoning sophisticated work on photography and the politics of representation by Black, lesbian, and gay artists, that led to the first meetings of the AIDS and Photography group.

47

Bodies of Experience and the AIDS and Photography Group

It is unclear exactly who was present at the first meeting of the group at the London Lesbian and Gay Centre in Farringdon (opened by the GLC in 1985) in September 1987, though it certainly included Simon Watney, Jo Spence, Chris Boot, Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Jean Fraser, Sunil Gupta, and Tessa Boffin, the latter two of whom met each other there for the first time.54 Boot was working at the Photo Co-op in Tooting and took on administration of the subsequent meetings, though Watney remembers it as being very informal, akin to the meetings that were to found Outrage! a few years later in 1990.55 He showed some slides of how AIDS had been represented in the media, the group agreeing that such representations needed challenging through photography and that “as the crisis was escalating in our midst, something ought to be done”.56 The group had no formal constitution, only three initial aims:

5457first, to “support and empower people with AIDS, ARC, and HIV through photography”. Second, to: “address the social and ideological consequences of AIDS throughout photography”. And third, to: “provide a forum for the discussion, initiation, resourcing and co-ordination of AIDS and photography projects”.57

Boffin and Gupta describe how “in the first six months” of regular meetings “a major difference of interest emerged which led to the development of two parallel projects”, Ecstatic Antibodies and Bodies of Experience: Stories about Living with HIV (1989), the latter curated by Boot and Anna Harding. Boot recalls Bodies of Experience as “more education-focused”;58 for Boffin and Gupta, the difference hinged on “the politics of representation and the representation of politics”, with Bodies of Experience tending towards more documentary, photo communication work and Ecstatic Antibodies leaning more into fine art photography and critical representation.59 It would, however, be a mistake to read the opposition of these exhibitions too strongly. Complicating the distinction is that both sets of curators were drawing on the same dynamic set of tools for grappling with the photographic image and its histories and institutions, as set out in such texts as Photography/Politics: One (1979), Thinking Photography (1982), and Photography/Politics: Two (1986), and across the decade in Camerawork and Ten.8 magazines.

58The exhibitions also share a distinct collaborative frame and cast, especially in relation to other practices addressing AIDS at the time. Ecstatic Antibodies included works by some of the first artists to respond to the epidemic in Britain in its video programme, including Stuart Marshall, Isaac Julien, and Pratibha Parmar, yet by 1987 AIDS was beginning to figure, both obliquely and explicitly, in a wide range of other work, for example, David Robilliard’s text-based paintings and Andrew Heard’s pop montages. Derek Jarman had recently completed his Black Paintings series (1986–87), a set of 100 canvases thickly painted in black oil and encrusted with objects from the shoreline at Dungeness, one made each day after his diagnosis as HIV-positive, while the epidemic featured heavily in his films at the time, including The Last of England (1987), War Requiem (1989), and The Garden (1990), and in his bed and barbed wire performance installation at Third Eye Gallery, Glasgow (1989). Helen Chadwick was beginning her Viral Landscapes (1988–89), a set of digital montages of body cells over photographs of the Pembrokeshire coast, inspired in part by Watney’s Policing Desire.60 Leigh Bowery and Michael Clark had experimented with signifiers of AIDS in the costumes for Charles Atlas’s film Hail the New Puritan (1986), and Bowery would shortly use the same polka dot design, recalling the skin marks of Kaposi’s sarcoma, during his important solo window performances at Anthony d’Offay Gallery in 1988; d’Offay would shortly stage Gilbert & George’s For AIDS photostats as a CRUSAID fundraiser in 1989, works critiqued by Watney at the time for their “morbidity” and “gross sentimentality”.61 Watney’s polemical critique of Gilbert & George highlights how the responses of the AIDS and Photography group were set apart by particular commitments to the photographic medium. Jo Spence’s presence at the group’s first meetings is indicative of the nature of their political commitment, using photography in combination with text to unpick the psychic and social formation of subjectivity in ideology. Spence’s approach was informed by the wider neo-Marxist use of continental “theory”, from Althusser to Foucault and Lacan, to understand photography as a site of contestation and struggle, but she wore her interest in theoretical dogma lightly, as in her characteristically accessible suggestion that “if we are to take seriously any notion of telling the story of our illnesses, then we also have to take account of all the other silences that have informed the ways in which our subjectivity was formed and held in place, from childhood onwards”.62 The work in both Bodies of Experience and Ecstatic Antibodies drew on aspects of this political-theoretical approach to photography while retaining also the recognition of humour and accessibility, as the case study of Boffin’s work here will illustrate.

60In Watney’s reckoning, Ecstatic Antibodies was concerned “with interventions in the public domain of ‘art’ photography” and Bodies of Experience with “questions of health promotion and community practice”.63 The exhibitions’ interconnection extended beyond their shared beginnings. Fani-Kayode and Hirst produced photo sequences for both shows, Nothing to Lose for Bodies of Experience and Metaphysick: Every Moment Counts for Ecstatic Antibodies, which Mark Sealy would later combine into the Communion suite (1995) following both their deaths, while Boffin worked at Camerawork in the months leading up to the installation of Bodies of Experience in the gallery in April 1989.64 The exhibition also went on to have an extensive regional tour, accompanied by a local conference programme at each venue.65 Yet the remarkable sensuality of Fani-Kayode and Hirst’s work does highlight the broader lack of interest in sexual pleasure in Bodies of Experience, and its widespread importance to the work in Ecstatic Antibodies. Gupta recalls that early on he, Boffin, and Jean Fraser wanted the latter project to be pro-sex to counter the sex negativity of the “Don’t Die of Ignorance” campaign.66 (Fraser dropped out in the planning stage, supposedly because she lived in north London; the other two lived closer to each other in Brixton and Camberwell.67) The idea of being “ecstatic”, outside or other to the self in pleasure, was crucial to the exhibition’s refusal of reified identity and the government’s vilification of sex, while “antibodies” reads multiple ways at once, as a nod to the immune system and the body’s capacity to defend itself from infection, to the Foucauldian refusal of the subjection of the self through biopolitical control, and cheekily as the “anti” of Bodies of Experience. In retrospect it is the pro-sex, “artistic” bent of Ecstatic Antibodies that divided the two projects as they developed out of their common base.

63Photography through the York–London Axis

The other decisive difference was the opening and tour of Ecstatic Antibodies by Impressions Gallery of Photography, then based on Colliergate within the medieval walls of the city of York.68 Val Williams and Andrew Sproxton founded Impressions in York in June 1972 as the “first specialist photography gallery outside of London”, and only the second in Britain after the Photographers’ Gallery, at a time when the medium was largely excluded from fine art display and British photographic history was obscure.69 From its beginning the gallery worked to support emerging photographers, providing otherwise rare opportunities for exhibition. Impressions was a leader in what Anne McNeill has described as an emergent network of “publicly funded, independent, touring photography galleries”, established across the 1970s and 1980s, that inaugurated “a new beginning for photography” in Britain and included, alongside Impressions and the Photographers’ Gallery, Stills Gallery in Edinburgh, Open Eye in Liverpool, and Street Level in Glasgow (all still open), and F-Stop in Bath, Camerawork in London, Cambridge Darkroom, Montage in Derby, Zone Gallery in Newcastle, Portfolio Gallery in Edinburgh, and Pavilion in Leeds (all since closed). This network, and in particular the northern galleries across Liverpool, Salford, Leeds, York, Newcastle, and the central belt of Scotland, still awaits proper accounting in art history despite their historic importance. As McNeill argues, “without these visionary galleries it’s unlikely that British photography would have developed into the successful and influential medium that it is today”.70 Peter Ride captured this dynamic at the time, noting that even if 1990 “showed a conspicuous lack of high profile national exhibitions” (in contrast to 1989, the medium’s 150th anniversary), the year still showed that “consistent quality from both regional and capital city galleries belied any suggestion that the profile of the photography world was dependent upon blockbusters”.71

68One such quality exhibition produced through this network in 1990 was Ecstatic Antibodies. Boffin, Fraser, and Gupta first pitched the exhibition to Impressions in May 1988, when the gallery was under the directorship of Paul Wombell (1986–94) and interested in practices that “questioned documentary aesthetics of photography”.72 According to Elaine Williams, Wombell wanted to take the show on as part of Impressions’ effort to “promote fine art based photography which constitutes a direct challenge to mass media representation” and also “to prove that such a show could open outside of London” despite the “risk” of the erotics of the displayed work in the eyes of “largely city art galleries dependent on local authority funding”.73 Wombell references here the passing of Section 28 of the Local Government Act in May 1988, the legislative culmination of the general election campaign, tinged with homophobia, that led to Thatcher’s third victory in June 1987 and of Tory attacks on local authority equality policies funded through the rates, as the party increasingly turned to “moral” issues in the climate of economic turbulence following Black Monday. Section 28 both massively galvanised gay and lesbian coalitional work (as Gupta recalls, “suddenly in the mid-80s, we had this law that then brought the gay men and lesbians together”) and severely circumscribed its opportunities for local authority funding.74 It was a direct attack on culture and space as sites for the production and reproduction of subjectivities, “where our personal and collective identities and political confidence are formed and validated”, and was to play a central role in the censorship of Ecstatic Antibodies in Salford, and in perceptions of risk and self-censorship by local-authority-supported galleries and artists for years to come.75 Boffin, Fraser, and Gupta secured Wombell’s efforts to originate and tour the show in November 1988, having won research funding followed by exhibition funding from the Arts Council, outside of the strict remit of Section 28, which applied only to local authority funds.76

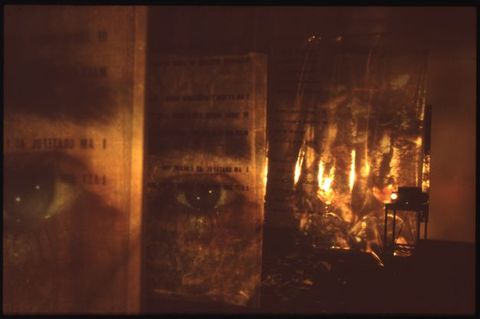

72The exhibition gradually took shape across 1989, with a shifting cast list of contributors testifying to Boffin and Gupta’s London networks and the availability of artists. There was no open call because the curators wanted to approach individuals and groups to ensure that they were “doing diversity” through Black, gay, and lesbian representation.77 Early drafts in 1988 show that they had already conceived of “two main vehicles for the work; an exhibition and a book” to display “a variety of media based work using AIDS as its subject matter”, including “photography, film, video, installation and performance”.78 Projects lost along the way include a collaboration between Boffin and Watney titled “Exclusion Zones”, a photo work based on histories of mass quarantine on Deadman’s Island, next to the Isle of Sheppey on the north Kent coast; Fraser’s contribution, after she left in early 1989; and a joint project by Yve Lomax and Susan Trangmar and a new short video piece by Derek Jarman, both of which, it seems, were never made.79 Projects gained by mid-1989 included Lowe’s (Safe) Sex Explained, part of his graduation show from the Slade School of Fine Art, and new work by David Ruffell, Al-an deSouza, Rotimi Fani-Kayode and Alex Hirst, and Joy Gregory, who had just arrived in London from Manchester School of Art (fig. 13). The line-up of contributors to the book gradually lost Keith Alcorn, David A. Bailey, Richard Dyer, Stuart Hall, and Barbara Smith and gained S. R. Tobe.80 The great shock just before the exhibition opened at Impressions was the sudden death of Fani-Kayode in London on 21 December 1989.81 He and Hirst had already sent the installation instructions for Metaphysick to Impressions, and Hirst followed up with a short obituary statement for Wombell to affix to the wall adjacent to the work, in which he describes Metaphysick as “an altar-screen, an elusive surface between you and another idea of life. It is our vision of living and dying”. This formulation serves more broadly to describe some of the most successful work in Ecstatic Antibodies that attempted to depict new ways of living in the time of HIV and begins to suggest why it courted so much controversy.

77

Vision, Content, and Censorship

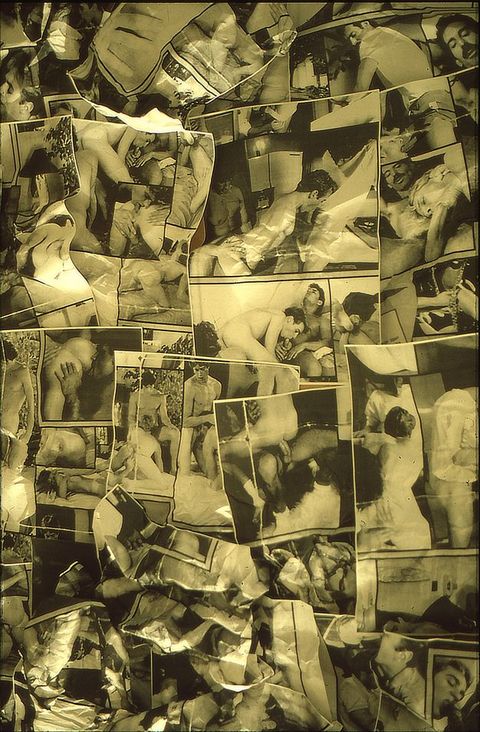

Having established the archival instability of the Ecstatic Antibodies exhibition and its emergence between London and York at a pivotal transitional moment for Black, gay, and lesbian photo practices faced with the burgeoning AIDS crisis and Thatcherite economic and “moral” attacks, I want to spend the remainder of this article focusing on two aspects of the exhibition’s work on sex and sexuality. First, the question of censorship and its fraught relationship with the “content” of the works by Lowe, Gupta, and Boffin that were the cause of controversy, focusing on Boffin’s work in particular; and, second, how the exhibition’s materiality was in dialogue with the print reproduction of imagery of safer sex at the time. Both questions showcase the wider context of vision and representation in which Ecstatic Antibodies was intervening. According to the Yorkshire Evening Press, only four days after the opening of Ecstatic Antibodies on 27 January 1990, “the visitors’ book already contains comments complaining the display is disgusting”.82 The early controversy centred on Lowe’s installation (Safe) Sex Explained, a work exploring the negativity of safer sex as a loss of sexual pleasure. Enclosed in a 24-foot by 8-foot black curtain box, the viewer encountered four suspended acetate and vinyl screens, two printed with lines of text expressing resentment and anger at the necessity for safer sex, lit at either end by two projectors displaying rotating sets of slides of body close-ups and used condoms littering the undergrowth of cruising grounds (fig. 14). Crumpled up photocopy reproductions of gay porn magazines from the 1970s, showing condomless sex, carpeted the floor of the work, representing the world that for Lowe had been lost (fig. 15). This work was critically divisive, with Elaine Williams being “glad to escape” its black box, finding the tone as “angry and resentful” in contrast to the exhibition’s wider emphasis on eroticism; Emmanuel Cooper, by contrast, praised Lowe’s interrogation of the challenge of HIV to the “complex sexual base” of gay men’s identity.83 At Impressions it was the crumpled reproductions of pornography, albeit dimly visible only by the light of the projectors, that caused a visitor to complain to the Conservative member of parliament for the city of York, Conal Gregory, that the exhibition was showing sexually explicit content. The police visited the gallery and requested that (Safe) Sex Explained be moved into an adults-only space, while Stefan Sadofski of Impressions told the Yorkshire Evening Press that one would “have to look fairly hard to see what’s supposed to be offensive” and that “if people are going out looking to be offended they might be”, thereby touching on the question of overdetermination of vision that was so central to the exhibition’s reception.84

82

By early February, Jane Brake, the exhibitions outreach officer at Viewpoint Photography Gallery in Salford had booked Ecstatic Antibodies to show in October 1990, with the approval of the North West Arts Photography subcommittee, the Association of Greater Manchester Authorities (who provided Viewpoint with local authority funding), and Salford city councillors.85 The principal arts officer at the council then got wind from a report by Brake that the police had been in the space at Impressions and enforced the segregation of Lowe’s work. On 20 April the officer held a meeting with Brake and Paul Brownridge, another curator at Viewpoint, in which “she is alleged to have said that she thought parts of the show were pornographic”, expressing concern at the “male nudes” in Gupta’s No Solutions and the “lesbians having oral sex” in Boffin’s Angelic Rebels, and signalling her intention to cancel.86 At a later meeting, the officer announced “a management decision that this was not a suitable exhibition for a family gallery” and cancelled the booking; an angry Brake later told Creative Camera, “Clause 28 was mentioned”.87 Royston Futter of the council explained to Manchester City Life, “we did not want to put our Authority in a position where it might be raided by the police”.88 As we’ve seen, the decision provoked a response from ACT UP Manchester, which included the protest in the gallery photographed by Gardner (despite the gallery workers being unhappy with the cancellation); they also sent protest faxes to Salford council offices and disrupted an arts and leisure committee meeting.89 A Salford councillor explained that “it is considered that the material is not suitable for a council-run public gallery” because of Ecstatic Antibodies’ “content”.90

85

The issue of content is crucial, especially in relation to Angelic Rebels, because it appears that no one could quite agree on what the “content” of these images exactly was. Boffin’s photographs provoked a quite extraordinary degree of confusion in the visual field. In Angelic Rebels, Boffin presents a fantasy-based photo narrative, in which the lesbian angel Melancholia is at first isolated and depressed by reports of AIDS in the tabloid press, before books and essays on safer sex by gay and lesbian writers appear at her feet (figs. 16–20). As she begins to read, a second “safer sex” angel appears behind her, and they embrace as sex toys and lube appear at their feet. Melancholia now becomes an angelic rebel, her head thrown back in abandon as the safer sex angel grips her harness and thigh with latex-gloved hands and nuzzles her head into the angelic rebel’s groin. Salford’s objection hinged on the final photograph showing “lesbians having oral sex”, a reading that Boffin rejected:

91A lot of the work has been badly misread: like a series of five pictures by myself with two women dressed as angels who end up embracing: they said my work was about lesbians having oral sex. I can’t see anyone having oral sex—they’ve both got their clothes on. It’s about lesbians and safer sex.91

Writing to Salford on behalf of Feminists Against Censorship, Sue O’Sullivan similarly contested the “hard core” reading, arguing that “the oral sex you have referred to seems non-existent and the image in question appears to portray a loving and passionate embrace, in an allegory which promotes safer sex”.92 Yet a reproduction of the photograph in the British Journal of Photography following the censorship drew the ire of one Martin J. Dobson of Cheshire, for whom the image appeared provocative of some kind of sexual insanity:

9293The militant sexual activists (of whatever predilection) may conduct business as usual under the banner of “safer sex”; there is no particular reason why the good people of Salford should be laboured with their theatricalities under the thin pretext of “AIDS awareness”, and no amount of exhortation to safer sex will necessarily result in saner sex.93

Finally, the hyperbole of Dobson’s response is in marked contrast to the view of a reporter from the Yorkshire Evening Press, for whom Angelic Rebels “approaches the feelings of loss provoked by AIDS seen through the eyes of a woman and shows a couple wearing angel’s wings with the woman soaring away from the man who clasps her”, a startling misrecognition in which the moment of lesbian climax is written out of sight altogether as vision seeks recourse to binary sexual difference, sentimentality, and mourning.94

94

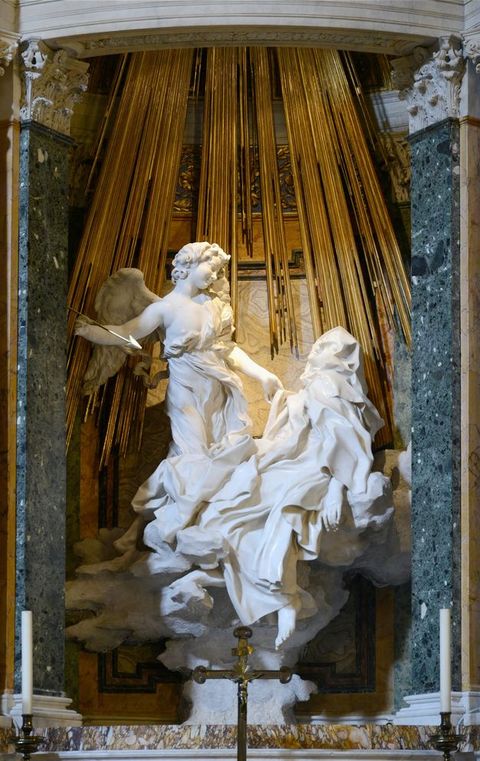

The variety of these responses demonstrates how challenging Boffin’s lesbian embrace was to the protocols of vision at the time, “completely uncompromising”, in the words of Miriam Newman, except of course in the last instance, where lesbian desire is inconceivable and hence invisible.95 The disputes over the content of this photograph demonstrate what Parveen Adams would soon call an image’s “emptiness”, that is, its capacity to be filled in by the (sexual) unconscious of its viewers.96 O’Sullivan suggested that perhaps Salford council found “homosexuality to be pornographic per se”, catching on to their overdetermination of same-sex desire as itself indecent and touching on the wider definitions of obscenity and indecency that were so central to the regulation of pornography in Britain at the time.97 That such confusion should centre on Angelic Rebels is, however, no mere accident. For Boffin was deliberately playing with ascendent feminist debates over the possibility of representing women’s sexuality, of feminine jouissance as both overdetermined and an epistemological limit, debates that she uses to push beyond the boundaries of admissible images of lesbian desire while retaining the authority to masquerade otherwise. The importance of Albrecht Dürer’s Angel of Melancholia (1514) to Angelic Rebels is often cited, but just as significant is Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa (1647–51), especially given its currency in the disputed question of the representation of sexual difference at the time, prompted by Jacques Lacan’s discussion of the statue in Encore (1972–73), his seminar on feminine sexuality (fig. 21). Stephen Heath argued in 1978 that Lacan’s discussion of Teresa is both a theoretical analysis and a practical enactment of the phallic overdetermination of the sight of woman, rendering her as both lack and excess. Lacan’s notorious assertion that “you only have to go and look at the Bernini statue in Rome to understand immediately she’s coming, no doubt about it” enacts the phallocentric predetermination of vision that makes woman, as Heath puts it, “infinitely unknowable, knowable only as different, visibly, certainly that”.98 Jacqueline Rose replied that Lacan’s braggadocio functions to relegate “women outside, against the mastery of his own statement”, as an analytic of the limitations of knowledge as conditioned by castration, “irredeemably an erring”.99

95

Boffin works carefully on this visual instability, flirting with the discourse of difference over Teresa to create a photograph in which the representation of sexual pleasure and climax is irrefutable and disputable all at once. Angelic Rebels clearly emerges from the problem space of 1987, as Boffin took up an established trope in difference theory, in which the sexual content of an artwork was in dispute, to remake it with lesbian desire as its subject, thereby challenging what Mandy Merck described as the “polite silences” of psychoanalytic cultural theorists, “largely unable to theorise homosexuality” because of the dominance of the “total Otherness” of the masculine/feminine division, occluding the sight of other, or same, differences.100 Boffin used the template of Teresa to gesture towards lesbian jouissance, ecstatic sexual pleasure. She inverts the positionality of giver and receiver, the standing angelic rebel’s face tilted upwards in reference to Saint Teresa’s ecstatic gasp, while Bernini’s cherub is displaced to a back projection of the statue of Anteros in Piccadilly Circus, shown in the previous image in the series as the lovers catch sight of each other. Certainly the tension in their embrace—between the firm grip of the safer sex angel on the harness, the angelic rebel’s palm and fingers resting through her spiky hair, her gentle nuzzle into the angelic rebel’s crotch—creates a far more entwined image of physical intimacy than that of Bernini’s Saint Teresa. The strap-on, dildo, and lube that appear at their feet imply possible use, though even Emmanuel Cooper overreads this in his description of “two women meeting and with a range of sexual apparatus such as dildos enjoying the physical side of the union”, as Boffin is careful merely to hint at, not insist on, possible penetration.101 She locates Angelic Rebels within an intertextual field of representations of sexual indeterminacy: the single sparkling glint from the safer sex angel’s wing at lower right recalls the crackled, punched gold patina of the Wilton Diptych (1395–99) and its depiction of sultry androgynous angels, a fragment of which is included here as a back projection (fig. 22). Boffin mobilised the sexual overdetermination of vision that Lacan enacted and located in gazing at Saint Teresa to create a scene of lesbian desire in which the jouissance of safer sex practice could be evoked without recourse to any explicit representation of sex or penetration. It is a historic irony that, for Salford, Boffin’s ambivalent depiction of ecstasy worked too well, for the council’s certainty mimicked Lacan’s, as a positioning of the spectator under the prevailing law (Section 28), in which only one truth, one certainty of vision, could be seen—that of the pornographic, indecent image.

100

Reproduction and the Materials of Safer Sex

Jane Brake commented to Creative Camera that “I’m angry that Salford wasn’t able to have a show about AIDS/HIV. I know it was censored because it contained work by lesbian and gay artists. The reason it was censored was because employees of Salford council were afraid of being prosecuted under Clause 28”.102 Given the exhibition’s focus on the politics of representation of AIDS, the ironies of this in Salford were acute. In the first issue of Versus the Virus, “a quarterly magazine focusing on HIV/AIDS prevention in Lancashire”, published in 1991, Andrew Hobbs describes a study of six straight pornographic magazines, commissioned by Preston and Blackpool Health Promotion Units and undertaken by students at Lancaster University, which found that safer sex, condoms, and dental dams were not mentioned in any one of the 142 erotic narratives printed in the magazines.103 In other words, explicit top-shelf material available in Lancashire’s newsagents did not promote safer sex but was freely available, while Boffin’s work, certainly provocative but not explicit, erotically and humorously advocated for safer sex but was not available for the good people of Salford to see. Feminists Against Censorship argued in 1991 that the overwhelming misogyny of available pornography is due to the censoring effects of the Obscene Publications Act (1959) and “the prudery of the Customs service”, which prevents the production and distribution of more experimental material; they suggest that “alternative feminist and gay publications are likely to be a prime target” should censorship of pornography tighten in Britain: “indeed, they already are”.104 Hobbs recounts how in October 1990 OXAIDS, a voluntary group in Oxford, had produced sexually explicit safer sex material in emulation of Leeds AIDS Advice’s pioneering “Hot ‘n’ Healthy Times”, but ran into trouble with Family Concern, a right-wing pressure group, who angrily sent proofs of material to the local press in complaint of its indecency. For Watney, the censorship of Ecstatic Antibodies was a crucial incidence of a wider concerted effort by politicians and pressure groups to confuse the legal distinction between obscenity and indecency, as established in the Wolfenden Report of 1957. If previously obscenity had “covered sexual imagery, which people might wish to see or read by choice” and indecency “a casual acquaintance with images which you might not have chosen to look at”, with the latter being a criminal offence, then post-Wolfenden strategy attempted to collapse the former into the latter, ignoring the determining role of choice.105 Yet Edward King explains the 1959 Act: “the test of obscenity must be applied to the article as a whole, requiring sexually explicit content to be judged in its context”.106

102The dynamic relationship between content and context was central to the iterative conception of Ecstatic Antibodies. The publicity around the censorship in Salford ultimately won the show more bookings, a crucial aspect of which was an accompanying conference for local statutory and voluntary AIDS workers and wider communities, which took place at several venues across the run including York, Birmingham, Cardiff, Glasgow, Montreal, and Dublin. At Impressions, this included Boffin leading a two-day workshop with students at the College of York and Ripon St John, in which they used photography and photomontage to produce their own safer sex imagery, and the “Re-Viewing AIDS” conference on 3 February 1990 at Ripon St John. Keynote speakers included Nick Partridge from the Terrence Higgins Trust and Simon Watney on AIDS representations, and afternoon workshops were led by Roberta McGrath; Sunil Gupta; Mehboob Dada from the Black AIDS Network, who had recently been producing safer sex graphics for Muslim communities in Bradford; Kate Butcher from Leeds Health Authority; and Graham Alinson from Leeds AIDS Advice. Present at this conference were representatives from over forty AIDS organisations from across Bradford, Durham, Halifax, Harrogate, Huddersfield, Hull, Leeds, Leicester, London, Macclesfield, Manchester, Newcastle upon Tyne, Northallerton, Pontefract, Sheffield, Suffolk, Sunderland, Wakefield, and York. Reviewing this list now, one realises how diverse and little known the history of the response to HIV in Britain is, especially as it was manifest in local and regional organisations, outside the metropolitan areas of London and Edinburgh, which often draw the greatest focus.107 It shows how work on the history of art, visual culture, group organising, and HIV/AIDS in Britain has barely begun (the speculative suggestion of What Would an HIV Doula Do? that “any expression of AIDS-related culture is just a sliver of a sliver of larger conversations about HIV/AIDS” is useful to bear in mind here).108 Like the subsequent conferences, “Re-viewing AIDS” was designed to enable local workers to produce their own imagery and material interventions appropriate to the epidemic as it was playing out in their own local area.

107

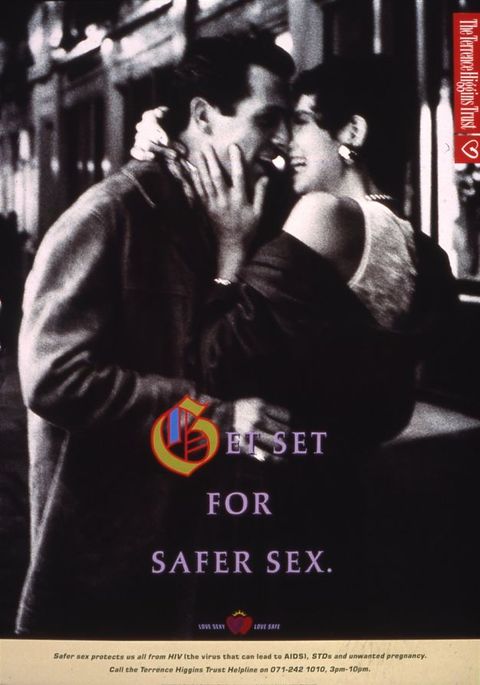

The question of content and context also returns us to the instability of the Ecstatic Antibodies archive and the dynamic relationship between photography and print, as exemplified in the contrast between the material complexity of Fani-Kayode and Hirst’s Metaphysick and the subsequent iconicity and reproducibility of “The Golden Phallus”, with which I began. The shifting context of the state’s response to HIV is important here. While the AIDS and Photography group had first met in response to the 1986–87 British government campaign, by the time Ecstatic Antibodies was preparing for installation there had been a significant shift in attitude to the epidemic. In 1989 the government disbanded the cabinet committee on AIDS and the Health Education Authority’s special AIDS Unit, while parliamentarians and the press frequently denounced AIDS as a homosexual conspiracy.109 The result was a notable shrinkage of material state support for HIV/AIDS education and prevention, an important context in which to understand the materiality of Ecstatic Antibodies. A flyer for the Terrence Higgins Trust’s 1989 “Get Set for Safer Sex” poster campaign, made prior to what Watney has critiqued as its suffocating efforts at respectability in the early 1990s, is illuminating in this regard (fig. 23a–c). The series shows six couples in various states of posed embrace, set against single-line captions that each begin with an illuminated gothic initial. The accompanying text sets out the aim of the campaign to stimulate debate in bars and nightclubs; the third paragraph reads: “A2 size, featuring rich black and white photographs, they are produced and designed to high standards, printed with full colour graphics and on thick art paper. They look great!” The representational emphasis on pleasure in safer sex is matched with investment in the seductive possibilities of the photo surface itself, using materials that are both reproducible and auratic. Thick paper, rich photographs, and full colour are envisioned as doing as much work as the pictorial to incite the practice of safer sex (fig. 24). “Getting Set” for safer sex in this context also refers to typesetting and lithography, the reproduction practices of print that allow for the dissemination of image and text and that provide a wider contextual clue to both the investment in materiality in Ecstatic Antibodies and its subsequent invisibility. The relationship between the work of the Terrence Higgins Trust and the artists in Ecstatic Antibodies at this time is more than anecdotal. Both projects emerged from overlapping networks of photographers, theorists, and activists, notably Watney as a member of both the Health Education Group at the Trust and the AIDS and Photography group, but also as attested by the “Re-viewing AIDS” conference. The varied medieval motifs, from Fani-Kayode and Hirst’s hybrid references to Coptic and Yoruban imagery and European manuscripts to Boffin’s inscription of the Wilton Diptych and the illuminated initial of the “Get Set for Safer Sex” campaign, also indicate a shared drive to pull on and reproduce anew the sacred iconographies of the past to reimagine sex and pleasure and to incite new practices and imaginaries through the reproduction and circulation of images.

109

“Pushed Well Back Out of Public Sight”

In 2004, looking back on the moment of Ecstatic Antibodies, Sunil Gupta reflected that what could have been a cresting tide of cultural activism around HIV/AIDS in Britain quickly dissipated:

110at the end of the 1980s, some colleagues and myself took on the Arts Council and the visual arts galleries to give us space to put on shows that questioned our understanding of HIV issues. We thought we were at the beginning of some radical movement for change here. But it hasn’t turned out like that.110

As we’ve seen, Ecstatic Antibodies emerged out of a very specific moment in the British epidemic and then slipped out of sight into a partial and fractured archive, as the circumstances of HIV continued to mutate rapidly and artists moved on to different concerns. The cultural politics of AIDS shifted in the early 1990s as continued government disengagement from the lived realities of its epidemiology led to the concerted effort to “re-gay” the epidemic in Britain. Following the censorship of his work, Lowe turned away from representations of the body in his practice to work on the Living Proof project, as discussed by Fiona Anderson in this special issue.111 Hirst looked to consolidate Fani-Kayode’s legacy, before his own death in 1992, while Gupta and Boffin continued their own separate curatorial and artistic projects on legacies of colonialism and lesbian representation, before Boffin’s death in 1993. The photos of Esctatic Antibodies held in the Gupta+Singh Archive contain this historicism and contingency in their very form, carrying the tenuous precarity that is the condition of history itself in the ongoing time of HIV. Such precarity has a particular inflection in Britain, testifying to the long-standing paradoxes of the HIV epidemic here as both hyper-visible, drawing out violent homophobia, and socially marginal. As Watney reflected in 2000, the two historic factors informing the “disproportionately small epidemic by European standards” in Britain were “the continued community-based mobilization amongst gay men since the early 1980s, and the government’s introduction of a national network of needle-exchanges since 1986”.112 The result was that, by 2000, there was “no reason why most people should have any particular in-depth understanding of the real history of AIDS in Britain”, with the epidemic and private suffering “pushed well back out of public sight”; indeed, the United Kingdom “was the only country in the developed world” in which “reports of the new combination therapies announced at the 1996 Vancouver AIDS conference were not headline news”.113 In such circumstances, Watney suggests, as “perceptions of the of the real epidemic on our doorsteps drift further and further into the background”, so “archives take on a very special importance”.114 I have argued through Ecstatic Antibodies that any reckoning with the history of “British art” and HIV/AIDS must account for these occlusions: the constant shifting of the political ground, how artists had to adopt provisional tactics in the face of the damaging effects of censorship, and most importantly the diffuse marginality and brute centrality of the epidemic to social and political life in the United Kingdom. The surviving works of art and material traces open onto these historical conditions. It would be all too easy and ignorant not to attend to them.

111Acknowledgements

My special thanks to Sunil Gupta, Charan Singh, Simon Watney, Nicholas Lowe, Joy Gregory, Emily Andersen, Alixe Bovey, Flora Dunster, Tom Powell, Anna Reid, and archivists at the Museum of Science and Media, Bradford, London College of Communication, and Bishopsgate Institute. I am grateful to audiences who heard and commented on earlier drafts of this work at a Paul Mellon Centre research seminar in 2020, the “Queer” “British” “Art” panel at the Association for Art History conference in 2021, and the conference “Grassroots: Artmaking and Political Struggle” at the University of Cambridge / Kettle’s Yard, also in 2021. This research was initially supported by a Research Forum Postdoctoral Fellowship at the Courtauld Institute of Art from 2019 to 2020.

About the author

-

Theo Gordon is Leverhulme Early Career Fellow in History of Art at the University of York, working on a book provisionally titled “Viral Landscapes: Art and HIV/AIDS in the UK”, due in 2026. He has published widely on modern and contemporary art, with essays on Helen Chadwick, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Douglas Crimp, Sunil Gupta, and other artists in journals including Oxford Art Journal, Art History, and InVisible Culture, and reviews regularly for Burlington Contemporary. He is co-author with Flora Dunster of Photography—A Queer History (2024) and editor of We Were Here (2022), a book of Gupta’s essays for Aperture.

Footnotes

-

1

Charles Darwent, “How Did British Artists Respond to the AIDS Crisis?”, Apollo Magazine, 28 November 2022, https://www.apollo-magazine.com/aids-crisis-british-artists. ↩︎

-

2

Estelle Pietrzyk, Aux temps du sida: oeuvres, récits et entrelacs (Strasbourg: La Musée d’Art Moderne et Contemporain de Strasbourg, 2023). The exhibition ran from 6 October 2023 to 4 February 2024. On the important international Red Hot AIDS Benefit series, see Simon Watney, “Short-Term Companions: AIDS and ‘Popular’ Entertainment”, in Practices of Freedom: Selected Writings on HIV/AIDS (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1994), 197–220, and John Carlin, “Groovin’ with the Mix”, Gazette (Montreal), 2 August 1992, https://gmforever.com/inside-story-of-red-hot-dance. ↩︎

-

3

Elisabeth Lebovici and François Piron, eds., Exposées: D’après Ce que le sida m’a fait d’Elisabeth Lebovici (Paris: Palais de Tokyo / Brussels: Fonds Mercator, 2023). The exhibition Exposées ran from 16 February to 14 May 2023; Every Moment Counts ran from 18 February to 22 May 2023. Raphael Gygax and Heike Munder, eds., United by AIDS: An Anthology on Art in Response to HIV/AIDS (Zürich: Migros Museum für Gegenwartskunst and Scheidegger & Spiess, 2019)—this exhibition ran from 31 August to 10 October 2019. ↩︎

-

4

Thibault Boulvain, L’art en sida, 1981–1997 (Dijon: Les Presses du Réel, 2021); Elisabeth Lebovici, Ce que le sida m’a fait: Art et activisme à la fin du XXe siècle, 2nd ed. (Geneva: JRP / Paris: Fondation Antoine de Galbert, 2021). ↩︎

-

5

Sunil Gupta, conversation with the author, 15 January 2020. ↩︎

-

6

Richard Johns, “There’s No Such Thing as British Art”, British Art Studies 1 (2015), DOI:10.17658/issn.2058–5462/issue-01/conversation. ↩︎

-

7

Simon Watney, “Preface”, in Practices of Freedom, xx. ↩︎

-

8

Hamad Butt, “Apprehensions” (1990), in Hamad Butt, Familiars, ed. Stephen Foster and Gilane Tawadros (London: INIVA and John Hansard Gallery, 1995), 43. ↩︎

-

9

George Baker and David Joselit, eds., “A Questionnaire on Global Methods”, October 180 (Spring 2022): 3–80. ↩︎

-

10

Watney makes this point repeatedly in his essays written at the time, for example, “AIDS has to be understood both in its local context, and in relation to the particular moment in time” (Simon Watney, “Silence = Death” (1990), in Practices of Freedom, 179). ↩︎

-

11

Peter Aggleton, “Identity and Audience: Living with HIV Disease”, International Studies in Sociology of Education 6, no. 2 (1996): 216. As Jan Zita Grover wrote in 1991, “AIDS is everywhere different in the problems it raises—in its demographics, epidemiology, finances, politics, service infrastructure, and relation to local religious groups, and in public perceptions of it” (“Reviews: Ecstatic Antibodies: Resisting the AIDS Mythology”, AFTERIMAGE 18, no. 6 (January 1991): 15). ↩︎

-

12

Jih-Fei Cheng, Alexandra Juhasz, and Nishant Shahani, eds., AIDS and the Distribution of Crises (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2020). Jackson Davidow’s PhD thesis, “Viral Visions: Art, Activism and Epidemiology in the Global AIDS Pandemic” (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2019), is one important contribution; see also Theodore (ted) Kerr, ed., “What You Don’t Know About AIDS Could Fill a Museum”, On Curating 42 (2019), https://www.on-curating.org/issue-42.html. ↩︎

-

13

Davidow, “Viral Visions”, 111. ↩︎

-

14

Stefan Sadofski, letter to Allan deSouza [now Al-an deSouza], 18 February 1994, Box 1, Folder 1, IMP/1/208, Museum of Science and Media, Bradford (hereafter IMP/1/208). ↩︎

-

15

Gupta, conversation with the author, 15 January 2020. ↩︎

-

16

Fani-Kayode and Hirst’s use of Cibachrome prints, made by exposing a colour transparency onto reverse colour paper, resulted in the rich deep tones of the images in Nothing to Lose and Metaphysick: Every Moment Counts which, as several critics have noted, is vital to their power. See Mark Sealy, Decolonising the Camera: Photography in Racial Time (London: Lawrence & Wishart, 2019), 227, and Kobena Mercer, “Mortal Coil: Eros and Diaspora in the Photographs of Rotimi Fani-Kayode”, in Travel and See: Black Diaspora Art Practices Since the 1980s (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016), 97–128. ↩︎

-

17

Elizabeth Fidlon, letter to Paul Wombell, 1 November 1989, Box 1, Folder 2, IMP/1/208. ↩︎

-

18

British Journal of Photography, 25 October 1990, Box 2, Folder 1, IMP/1/208. ↩︎

-

19

Since their digitisation, some of the images of Ecstatic Antibodies have been published in D. Mortimer, “Spotlight: Ecstatic Antibodies Thirty Years On”, Wandsworth Art, 28 July 2021, https://wandsworthart.com/spotlight-ecstatic-antibodies-thirty-years-on, and have also featured in Tessa Boffin’s Angelic Rebels (dir. Ania Kaczyńska, 2023), a short film for the Paul Mellon Centre British Art in Motion competition. The images are published here most fully for the first time. ↩︎

-

20

The American psychologist and pragmatist philosopher William James, known for popularising the term “stream of consciousness”, defined “sciousness” as the broader field of consciousness, as opposed to consciousness of self in his Principles of Psychology (1891). ↩︎

-

21

Rotimi Fani-Kayode and Alex Hirst, “Metaphysick: Every Moment Counts”, in Ecstatic Antibodies: Resisting the AIDS Mythology, ed. Tessa Boffin and Sunil Gupta (London: Rivers Oram, 1990), 84. ↩︎

-

22

Ibid. That it has been impossible to conceive the intricacies of Metaphysick as seen in exhibition has led to some critical confusion, for example Bourland’s suggestion that the “icons” of the Cibachrome photographs constituted the “sacred forms that are central to the composition” rather than the four painted figures as an element of the installation in their own right (W. Ian Bourland, Bloodflowers: Rotimi Fani-Kayode and the 1980s (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019), 214. ↩︎

-

23

Kobena Mercer, “Mortal Coil”, 98. ↩︎

-

24

Kobena Mercer, “Welcome to the Jungle: Identity and Diversity in Postmodern Politics”, in Identity: Community, Culture, Difference, ed. Jonathan Rutherford (London: Lawrence & Wishart, 2003), 47. ↩︎

-

25

Stuart Hall, “Cultural Identity and Diaspora”, in Identity, ed. Rutherford, 222. ↩︎

-

26

Jonathan Rutherford, “A Place Called Home: Identity and the Cultural Politics of Difference”, in Identity, ed. Rutherford, 20. ↩︎

-

27

Pratibha Parmar, “Black Feminism: The Politics of Articulation”, in Identity, ed. Rutherford, 101–26. ↩︎

-

28

Pratibha Parmar, in Isaac Julien and Pratibha Parmar, “In Conversation” (1988), in Ecstatic Antibodies, ed. Boffin and Gupta, 96–102. ↩︎

-

29

A Plague on You was first broadcast on BBC 2 on 4 November 1985. The members of the Lesbian and Gay Media Group were Clare Bevan (later producer of Out on Tuesday, 1989–91), Stephanie Chambers, Jeff Cole, Nicola Field, Stuart Marshall, Colin Richardson, and Matt Williams. Green Apples is out of circulation (conversation with Emily Andersen). ↩︎

-

30

Joy Gregory, conversation with the author, 21 July 2023. ↩︎

-

31

Hall, “Cultural Identity and Diaspora”, 224, 232. ↩︎

-

32

Ibid., 225. ↩︎

-

33

Simon Watney, quoted in Cherry Smyth, Lesbians Talk Queer Notions (London: Scarlet Press, 1992), 20. Many of the artists and writers in Ecstatic Antibodies also contributed to Smyth’s book, including Tessa Boffin, Isaac Julien, Pratibha Parmar, and Watney. ↩︎

-

34

I follow Stuart Hall’s use of the terms “problem space” and “conjuncture” in his “Black Diaspora Artists in Britain: Three ‘Moments’ in Post-war History”, History Workshop Journal 61, no. 1 (2006): 1–24. ↩︎

-

35

Thatcher’s hatred of the progressive taxation of the rates system was to be central to her eventual downfall when the poll tax was introduced to replace them in 1989 (in Scotland) and 1990 (in England and Wales). ↩︎

-

36

Stuart Hall, Chas Critcher, Tony Jefferson, John Clarke, and Brian Roberts, Policing the Crisis: Mugging, the State and Law and Order (Birmingham: Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies, 1978); Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies, The Empire Strikes Back: Race and Racism in 70s Britain (London: Routledge, 1982). ↩︎

-

37