Instituting Queer Art in Britain

Instituting Queer Art in Britain

“Conversation Piece” is a British Art Studies series that draws together a group of contributors to respond to an idea, provocation, or question.

-

Theo Gordon

-

Laura Guy

-

Pratibha Parmar

-

Simon Watney

-

Topher Campbell

-

Seán Kissane

-

Owen G. Parry

-

Campbell X

-

Helena Reckitt

-

Dominic Johnson

-

Michael Petry

-

Irene Revell

-

Sunil Gupta

Provocation by

-

Laura GuyReader in Gender, Sexuality and CultureGlasgow School of Art

-

Theo GordonLeverhulme Early Career Fellow in History of ArtUniversity of York

The institutional embrace of queer art in Britain in the last ten years has been a remarkable volte-face, in contrast to the preceding years of indifference to the gradual loosening of social mores and increasing public acceptance of LGBTQIA+ presence and rights, however partial and contested. The first exhibitions of openly “gay art” in the United Kingdom were held in small community-based and community-facing venues and were directly informed by engagement with consciously left-leaning political groupings, as in Emmanuel Cooper’s Art with a Gay Theme (1979) at Late Night Gallery in Earl’s Court, which developed out of his work on “gay art” for Gay Left, or Sunil Gupta and Jean Fraser’s Same Difference (1986) at Camerawork in Bethnal Green. The institutions supporting such work were politically engaged and committed, inspired by socialist thought and often financially supported by funding from local authorities. Prior to the neoliberal burgeoning of the art world and creative industries in the late 1990s, the hegemonic galleries of the time were indifferent or actively hostile to explicitly and politically identified gay and lesbian work. The 1980s witnessed a consolidation of institutional homophobia in Britain on a broad scale. Writing in 1991, Simon Watney observed that, “as public attitudes gradually change over time, it would appear that there has been a consolidation of prejudice at the level of institutional politics, where the subject of homosexuality can be easily exploited, or else ignored as a supposed electoral ‘liability’”.1 The mismatch between broad public opinion and institutional conservatism became entrenched for decades and still remains to be fully reckoned with.

1If 1970s queer culture in Britain could be characterised by the emergence of a public gay and lesbian politics, ushered in through radical Left groups such as the Gay Liberation Front (active in London from 1970 to 1973), the 1980s represented the foreclosure of its promise in many ways. The racialisation of Britain’s economic turbulence and social unrest, cuts in public spending, privatisation, increasingly successful attacks on trade unionism under Conservative policy, and the emergence of the HIV/AIDS epidemic all seemed to conspire to turn the dial definitively away from the liberatory promises of the previous decade.2 Yet, despite these straightened circumstances—or because of them—the 1980s also witnessed a groundswell of lesbian and gay activism in Britain, representing both the continuation of activities from the 1970s and the formation of many new grassroots organisations and projects. In the period bookended by Margaret Thatcher’s premiership, heterogeneous cultural activity associated with gay and lesbian organising took place in settings such as independent magazines and galleries, community centres and darkrooms, art schools and polytechnics, and spaces of local government and political organising, as well as through informal networks of production and distribution. Collective in spirit and left-aligned, this activity was shaped by simultaneous transformations in policy and funding, and overdetermined by tensions between segregated oppositional political groupings, to include gay, lesbian, anti-racist, and workers’ organisations. At the same time an emergent Thatcherite consensus, propagated by the policies of a majority government bolstered by victory in the Falklands War, spread across the decade to pull statutory, civic, and local institutions into its web of fiscal and social conservatism. The introduction of Section 28 into law in 1988 appeared to mark a high point in the resurgence of the New Right, gagging institutions financed by local authority funding from supporting lesbian and gay work. Yet independent cultural production rallied in reaction to it, as it did in light of the scandalously late response of the UK government to HIV/AIDS and the continued police harassment of Black communities, and began to break down barriers between gay, lesbian, and Black artists and collectives.

2In this context gay, lesbian and Black art, and cultural politics in Britain were transformed by the reclamation of the term “queer” in the late 1980s. In dialogue with activism and culture internationally, notably in North America and continental Europe, it was grassroots oppositional cultural production that formed the basis of a queer art in Britain, understood as a set of loose interpersonal and institutional associations, processes, practices, and ideas. The new queer art emerged from a network of community and local authority art spaces, protest movements, and new group formations in daytime and night-time spaces, while the term “queer” was the subject of intense debate, theorised and contested on the pages of popular magazines and academic journals. The change of mood was palpable; Cooper recalled the markedly warmer reception for his The Sexual Perspective between its first and second editions in 1986 and 1994.3 Artistic and cultural institutions in Britain began to respond to the new queer culture partially and fitfully, prompted first by community-based curatorial efforts such as Ecstatic Antibodies: Resisting the AIDS Mythology at Impressions Gallery of Photography in York (1990) and in exhibitions such as Read My Lips at Tramway in Glasgow (1992) and Bad Girls at the Centre for Contemporary Arts (CCA), Glasgow, and the Institute of Contemporary Art, London (1993). From the beginning its political efficacy as an organising term was disputed, yet “queer” was rapidly taken up to account for a whole range of historic and contemporary artistic practices. The thawing of relations between the government and some gay and lesbian rights organisations during John Major’s premiership, culminating in the partial lowering of the age of consent in 1994, was the context for the slow institutionalisation of queer across the decade, at the same time as the increasingly neoliberal economic context was quietly dismantling many grassroots formations, such as community art spaces and HIV/AIDS charities, and causing them to vanish. The AIDS crisis continued to decimate communities of artists, writers, and curators, contributing to cultural erasure.

3The intense dialogue between LGBT trade unionists and the back benches of the Labour Party (gay rights being far from Tony Blair’s interests and concerns) formed the context for New Labour’s policy platform, and on victory in 1997 and especially after winning the second term in 2001 legal reforms came thick and fast: equal age of consent in 2000, equality of adoption in 2002, the repeal of Section 28 in England and Wales and the abolition of the offence of “gross indecency” in 2003, recognition of trans identification in 2004, and civil partnerships in 2005. Devolution in 1998 granted Scotland the power to repeal Section 28 in 2000. In some respects, queer cultural politics also gained in power across this time, as witnessed in the expansion of the Gay and Lesbian Film Festival at the BFI (now BFI Flare), yet avowedly queer exhibitions, such as Michael Petry’s Hidden Histories at Walsall Art Gallery (2004), were few and far between. The cultural reckoning with the effects of the HIV/AIDS epidemic was non-existent, and neoliberal policy continued to increase the economic inequality between north and south and to isolate London from the regions and the devolved nations. The 2008 financial crisis and election of the Coalition government in 2010 entrenched and wildly exacerbated the neoliberal cleavage of queer politics, with David Cameron pursuing gay marriage in 2013 but, through austerity, eradicating the funding for local government and community initiatives for LGBTQIA+ people. The relentless march of austerity, the diversion of political energy into the circus of Brexit since 2016, and the eruption of COVID-19 in 2019 have further entrenched inequalities engendered by decades of neoliberal policy. Trans and gender-nonconforming people are instrumentalised and exploited across the political spectrum, while trans life is policed in unprecedented ways, including by reactionary feminist, gay, and lesbian groups and commentators. Meanwhile, art schools and universities face funding crises, their staff face job precarity and mass redundancy, and courses teaching radical oppositional histories are closed.

The institutional landscape supporting independent art production in the United Kingdom is now unrecognisable compared to the late 1980s; the political and community infrastructures that supported spaces through which “queer” was first formed in Britain have been dismantled by successive governments. As the effects of the breakdown of infrastructure in the United Kingdom—arguably a legacy of Thatcherite policy of the 1980s—become increasingly tangible, we are also witnessing a period of interest in defining and disciplining queer art within Britain. Alongside a host of artistic projects, community-led initiatives, and academic revisitations, there have been major institutional surveys, including Queer British Art 1867–1967 (2017) and Women in Revolt! Art and Activism in the UK 1970–1990 (2023) at Tate Britain, large-scale monographic exhibitions such as Sunil Gupta: From Here to Eternity at the Photographers’ Gallery (2020) and Hamad Butt: Apprehensions at the Irish Museum of Modern Art (2024). Many of these have been important occasions that have made queer cultures available to larger audiences. Yet the imperative towards visibility and the involvement of larger institutions can also betray the delicate and complex community context for some art practices and obscure the decades of queer labour, variously undervalued and unremunerated, that have allowed these practices to continue to exist, often within collections and archives that are informal and extremely precarious. The adoption of the moniker “queer British art” appears to promise or establish a narrative in the history of art, which belies the fragmentary and contested nature of queer cultural production. The rise of institutional “rainbow” initiatives obfuscates historical and ongoing institutional homophobia, persistent for decades and centuries, in the name of diversity and inclusion. Meanwhile, smaller spaces suffer: organisations such as the CCA, Glasgow, which once hosted exhibitions such as Bad Girls and Derek Jarman’s bed installation (as Third Eye Gallery in 1989), are facing the threat of closure.4 What is the cost of canons being established quickly and by large galleries? Do hegemonic institutions, including the academy, thereby centre themselves in the rescue, preservation, and study of grassroots oppositional work? Has “queer” become a marker of coherence and stability, another product label in the culture industry, rather than a radical challenge? Do monographic exhibitions and the ironically late celebration of singular prize-winning artists obscure the political and community context that vitally informed such practices? To what extent is the culture of memorialisation also one of erasure?

4And what might come of a return to the emergence of queer art in Britain at the end of the 1980s, of an examination of and reinvestment in the grassroots and community structures that sustained it? How has working with “queer” in institutional contexts changed or shifted since the late 1980s, and what are the insights and possibilities for institutional work now? Is there potential in this earlier moment, its varied politics and investments, that remains unrealised or undetonated? If all the present moment can yield is the celebration and canonisation of a chosen few artists, is it not a betrayal of the past and its politics, a foreclosure of the disruption and disobedience that “queer” once seemed to promise?

Response by

-

Pratibha ParmarFilm-maker, writer, and activist

Queer Art Response

1

Queer British Art, a category claimed | embraced by the

canon.

Whose canon? Whose narrative?

“British”. A nation state moniker. A contested term.

Empire and its relics are alive in the now.

2

Queer British Art. Queer British Artists. A set of

refusals. A set of capitulations.

Does it refuse commodification?

Is commodification a capitulation?

Is commodification an erasure?

Is commodification a collusion in institutional

sanitisation?

Is there evidence of refusals of institutional

appropriation?

So many questions. So little time for answers. Must Make

the Time.

3

Queer Art gained life | form through radical movements

of people pitting themselves against the pandemic of

egregious violations and acts of violence. Veneration of

a chosen few dismisses | erases decades-long accumulated

unpaid labour of queer artists. They | we who mapped the

broken cartography of queer cultural production. With

our cultural productions.

4

It’s not simple. It’s not a binary. For or against. An

artist friend posed a personal torment. “We, who have

worked on the margins, out in the wilderness of

community venues, we want our work to be seen and

welcome institutional support … BUT does this mean I am

being co-opted?” Does our | their art lose its radical

affront to these circles of cultural control who now at

their convenience see fit to embrace them, their craft?

Marginal invisibility is debilitating and | also why

look a gift horse in the mouth. But what kind of gift

horse is it?

5

Critical optics on institutional methodologies of

appropriation and acceptance is an essential note in the

negotiated dance that queer artists must choreograph.

This twitchy note | this productive tension all too

often missing in a rush to become a commodity. The

evidence is clear. The rush is understandable. The

capitulation is …

6

Where are the refusals to authoritative presumptions of

canon building? I would like to make a list of these.

7

Queer Art is hiding in fragmentary, precarious archival

collections in homes, in shoeboxes languishing in

lock-ups as no resources come forth to rescue,

categorise, and render it visible.

Queer Art is in plain sight in the plants, the flowers,

and the pebbles surrounding Derek Jarman’s cottage.

Queer Art is Nan Goldin challenging Germany’s complicity

in the genocide in Palestine.

Queer Art is my rage at Palestinian children, burnt

alive, and embedded in bombed-out buildings.

8

What are the queer pathways towards freedom?

What does a liberatory queer art practice look like?

Will it answer the young Palestinian girl rescued from a

bombed building, “Uncle, are you walking me to heaven?”

Response by

-

Simon WatneyWriter, activist, and art historian

The Moment of Queer

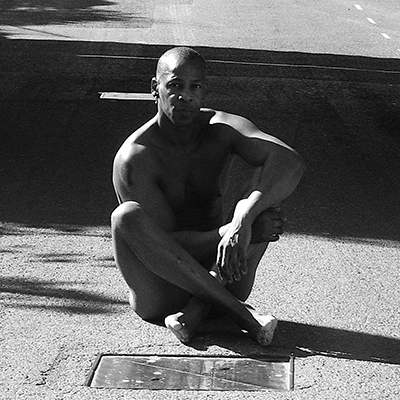

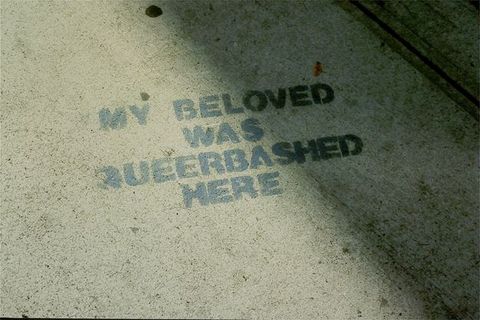

Emmanuel Cooper located The Sexual Perspective, his groundbreaking art-historical exploration of art and homosexuality, firmly in the context of the gay liberation movement and the women’s movement. He identified three aims: first, to explore “how and to what extent the artists’ own awareness of themselves as homosexuals has influenced their work”; second, to ask how, “given the cultural modes and social attitudes of society, artists have achieved both a self-representation and questioning of their sexuality”, reflecting “a growing awareness of the gay identity in contemporary society”; and third, how homosexuality itself has been defined and to whom it has been applied. As far as he was concerned, “just as there is no category ‘women’s art’ there is no question of attempting to define ‘gay art’”.5 In 2017, thirty years after Cooper’s pioneering book, Tate Britain hosted a portmanteau exhibition entitled Queer British Art, 1861–1967. In his foreword the gallery’s director notes how the show “reflects lesbian and gay identities, and ‘queer’ experience more broadly”. Here the sexuality of the artist was not the most important criterion for inclusion; work was selected because it “speaks in some way or other to the experience of sexual difference”. The term “queer” is used “to capture the diversity and ambiguity of its artist-protagonists”.6 This all speaks of a radically depoliticised use of the word “queer”, for which homosexuality is a decidedly secondary consideration. In her “Introduction”, the curator Clare Barlow refers to “the possibilities of queer interpretations: readings of bodies and objects that foreground connections with same-sex or gender variant desires”.7 She regards the show as an opportunity for a new “conversation”, defining queer as “an umbrella term for same-sex desire and gender-variant identities”, with the question of the balance between the two left open. Here the original word simply means “strange” or “eccentric”, while the term “queer” “foregrounds non-conforming sexualities and gender identities but avoids imposing identity labels on people that they themselves would not recognise and have not chosen”.8 It is not, however, the same word heard in the darkness by someone being viciously kicked around on the pavement by homophobic thugs, a permanent reality, as inscribed by Queer Nation’s ephemeral stencil interventions in public space (fig. 1).

5

The emergence of “queer” as a political category available for individual identities and for political mobilisation had very different histories in the United Kingdom and the United States. In Britain the word has a much nastier history than in the United States; here it has been widely used as an insult right up to the present day, and has taken several decades to settle in as an established twenty-first-century identity for the young. Queer has a distinct generational significance in Britain, where it is rarely used by men or women over forty of themselves or one another, and where its use at once identifies you as an activist and/or academic, or as a youngster. For many British gay men it is simply too tainted to be easily recuperated, and there were violent debates at early OutRage! meetings on this very subject in late 1989 and 1990. In a rough telephone survey of older friends of mine who are out gay men over the age of fifty, none reported using the term of themselves or others very often, while a few said that they use it in the company of much younger people, for whom, they recognise, its use is entirely taken for granted. One man described it as “a horrible word, ridiculous—it doesn’t apply to me”, while another thought it to be “used by straights as a badge of honour to show some kind of misguided display of solidarity”. “Dreadful” and “ostracising” were other descriptions of the term, which reminded me forcibly of the hostility of many older campaigners for gay rights towards the emergent Gay Liberation Front (GLF) activism of the early 1970s.

Rather than taking sides in such disputes, we would surely do better to historicise them properly. The courage required to be a member of the Campaign for Homosexual Equality (CHE) was far too easily dismissed by my generation, who failed to appreciate the damage caused by growing up as a despised queer in the 1950s or earlier, just as some of today’s young queers may fail to appreciate the damage done to the first generations of lesbian and gay activists. All this also reminds me of the routine and periodic denunciation of sexual categories as such, often dismissed as mere “labels”, which has always been a distracting strand in the modern lesbian and gay movement since the time of GLF, as if we could all live as self-sufficient individuals without any need for regulatory classifications, sexual or otherwise.

Thus in Britain the term “queer” seems to me to have two distinct phases that may broadly be associated with the twentieth and the twenty-first centuries. Recent use of the term feels entirely uncontroversial to most young people born since around 1990, who take sexual and gender fluidity and diversity entirely for granted, over and above differences of race, class, physical ability, and so on. What cannot be taken for granted is the actual violence and the legal or other types of institutional discrimination in relation to same-sex desire and non-binary gender roles and identities. The challenge, it seems to me, is to not lose sight of the activist energy of the inherited older lesbian and gay movement, its internationalism, and its well-informed targeting of offending institutions from the Church of England to the Commonwealth. Queer politics today seems very good at broadly celebrating diversity but is less focused in relation to the specific sites of active persecution of gay men around the world, ranging from imprisonment to the death sentence, the latter having recently been reintroduced in Uganda, for example.9

9It is very easy to criticise so-called assimilationism, but street-based activism is not always the appropriate means for achieving legitimate social and political goals. Largely as a result of the thankless work of many people, we now have queer geography, queer archaeology, queer art history, and so on, which all mark significant achievements within the academic arena and acknowledge sexual and gender diversity as a universal aspect of human history. These are a great gain for everyone because they involve “living in truth”, as the great Václav Havel described it.10 For a translation into queer terms, we might turn to Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s timely and bracing reminder of the “overarching, hygienic Western fantasy of a world without any more homosexuals in it”,11 which has been actively promoted by Georgia Meloni and many others. We are evidently still very much in what Sedgwick terms “the moment of queer”.12

10All of this may seem to be of political rather than art-historical significance, but queer remains to some extent a contested term and its history is very different in different regions of the anglophone world. Meanwhile its significance as an iconographic category remains far from clear, unlike its enthusiastic reception and use by the social constituencies for whom it evidently provides a primary social identity and the grounds for a lively creative culture ranging from photography to performance art. Unsurprisingly, this culture is itself a site of contestation between those who wish to engage with leading national art institutions involved in funding and display, and those who wish to work exclusively in their own queer space for queer audiences. In this respect the debate today duplicates many aspects of the debates between assimilationists and separatists in the earlier LGBTQ+ movement, but it does so with far higher stakes in the age of Brexit and “Make America Great Again” (MAGA), with rights now under renewed threat. The continuing challenges associated with the recent Queer British Art exhibition have to be thought alongside our responses to such straightened geopolitical circumstances.

Response by

-

Topher CampbellArtist and film-makerRukus! Federation

Towards a Blaquir Arts Movement

Meditation 1

In the height of the devastation of Hurricane Katrina, Kanye West proclaimed, “George Bush doesn’t care about Black people”. Kanye was outraged at the endemic undervaluing of Black lives in the event of devastating death and disaster. The frustration he expressed spoke to how the suffering of Black bodies is invisiblised even in the face of an overwhelming violent act of nature.

In Brazil at the height of government pacification, the policy that sought to eradicate drug gang control of the favelas, twenty-four Black men were massacred in one police raid. What became known as the Jacarezinho massacre revealed how Black and Brown people were being slaughtered regularly by state police.

In the United States “death by cop”, including the inhumane killing of George Floyd in 2020 and many others, became the tipping point that launched Black Lives Matter (#BlackLivesMatter), a global movement. Since then, Black Lives Matter has been systematically undermined, criminalised, and outlawed in the United States and the United Kingdom. The All Lives Matter slogan (#AllLivesMatter) emerged as a counter-narrative to neutralise anti-racism.

In 2025 a bill was introduced in Ghana, and upheld by their Supreme Court, criminalising people who identify as LGBTQ+. If it passes, Ghana will be the thirtieth of fifty-four African countries to enforce a law like this.

In the West, and particularly in the United States, Black trans women are at the forefront of abuse, exploitation, and murder or threat of murder, mostly by Black cis men.

Meditation 2

I reflect on these global perspectives as a Blaquir artist: How do I lean into a paradigm that is inspired by my identities but not entrapped within it? How does my Black body move from a space of being speculated on to a space of speculation and power? For I grew up in a time when white LGBTQ+ culture and mainstream Black culture didn’t care about Black LGBTQ+ people. I have been denied entry, denied resources, and denied a voice in artistic and liberal-minded environments—dismissed as being either “too niche” or “not niche enough”, or because institutions and arts venues saw no value in the work I wanted to create, even as they made space for expressions of Blackness that don’t challenge the status quo.

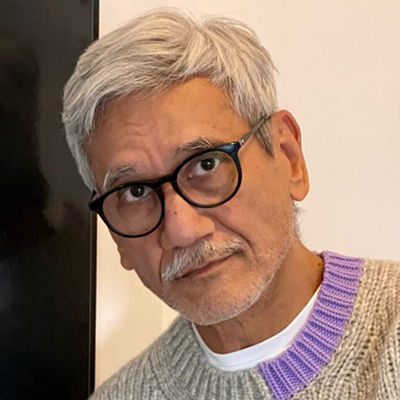

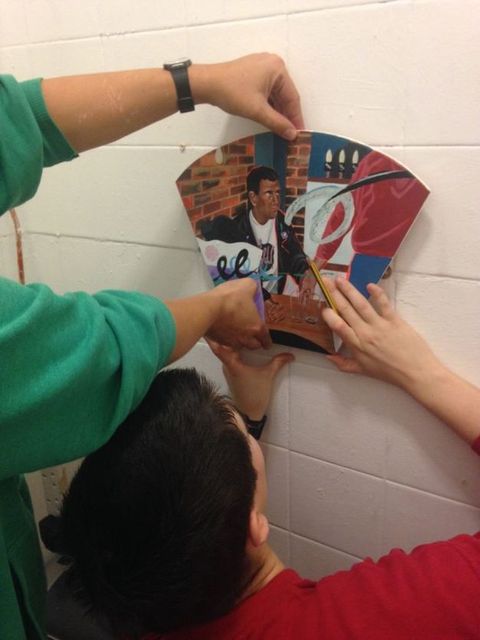

This is why I established rukus! Federation with the photographer Ajamu X. There was nobody thinking across genres of film, performance, visual arts, and the written word, and nobody invested in a conversation about British Blaquir culture that embraced complexity, playfulness, politics, process, aesthetics, and community. rukus! Federation, created by two Blaquir artists, embodies the notion of “Making Difference Work”—a mission title gifted personally by Stuart Hall, and later inscribed on the gallery wall in my 2024 Somerset House exhibition Making a Rukus!, which drew on the federation’s archive (fig. 2). At the same time, it channels a “You can all fuck off” energy inherited from the punk generation, mixed with liberation era roots reggae.

The United Kingdom is not innocent, as evidenced by the ongoing Windrush scandal. A scandal that has torn families apart and ruined lives. A scandal caused by the British Nationality Act 1981, which created first- and second-class citizenship according to place of birth, enforcing Britishness through a colonial lens. At the same time, the notion of a Blaquir history and culture has yet to establish itself in the hearts and minds of British Black culture or mainstream LGBTQ+ and cis-gender white culture. Two observations that speak to how institutional, legal, and cultural forces conspire to erase, undermine, and make invisible Blaquir culture, histories, and identities—for they are entwined.

Recognising that I exist in the cracks between the twin pillars of homophobia and racism, I sought out traditions and lives that matter to me, including the seminal work of Basquiat, Oscar Micheaux, Isaac Julien, Marlon Riggs, and Rotimi Fani-Kayode; the writing of Audre Lorde, Essex Hemphill, James Baldwin, and Samuel R. Delaney; and the practice of abstraction and Afrofuturism. My aesthetic needed to find its roots outside of Eurocentric and white supremacist notions of respectability politics.

Today there is a remarkable resurgence of Black art, but can we yet speak of a Blaquir art movement? Blaquir arts as a distinctive and generative space is still developing. The forming of a Blaquir arts tradition can’t be contained by notions of nationality or place but must be expressed through a diasporic sensibility despite the fact of being born in a specific country. It must also be rooted in our bodies as much as in our minds and spirits. Because, first and foremost, it is our bodies that disturb the peace and inspire fresh creative paradigms.

The question is: who retains, curates, creates, and mediates Blaquir narratives? It’s a question that needs to be interrogated with integrity and authenticity. This is why I am dedicated to working towards a Blaquir arts movement. I feel a burning desire to bear witness to my generation after so many centuries of abuse, deflection and denial inflicted on Blaquir realities. I speak here not only of past incursions but to the possibilities of present and future fabulousness.

Response by

-

Seán KissaneCurator of ExhibitionsIrish Museum of Modern Art (IMMA), Dublin

Queer Programming in Ireland

Situating Ireland in discussions of British art is fraught because of the entangled histories of the two nations. Rather than parsing their differences, I shall briefly outline how queer art and institutions have intersected in Ireland. Queer artists and art were profoundly impacted by the criminalisation of homosexuality, which persisted in Ireland until 1993 (and in Northern Ireland until 1982), fostering a culture of silence that marginalised queer identities. When queer art was exhibited, it was often deeply coded. This status quo remained until the early 1990s, when the first Catholic clerical sex abuse scandals began to erode the church’s authority. At the same time, Ireland’s economy expanded rapidly, reversing creative emigration and increasing investment in culture up to the 2008 financial crisis.

During this period, Dublin’s main publicly funded contemporary art spaces underwent renewal under new directors who all actively incorporated queer artists into their programmes. The first dedicated exhibition of queer art in Ireland, Pride in Diversity (1996), emerged from the artist-led OutArt series, which ran until 2001. That the second and third OutArt exhibitions were hosted by the Royal Hibernian Academy demonstrated that, at least in this case, institutional support for queer art followed artist-led initiatives. However, institutionally curated queer exhibitions have only gained momentum in the past decade.

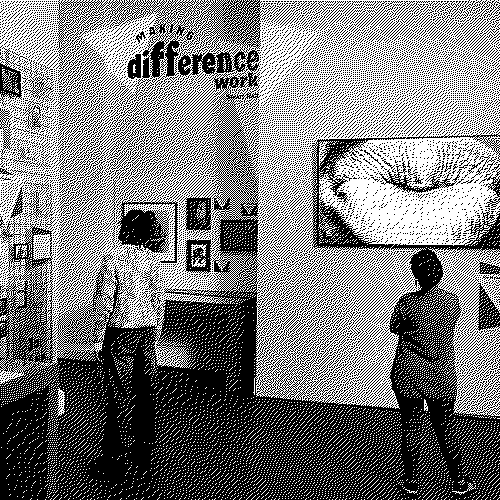

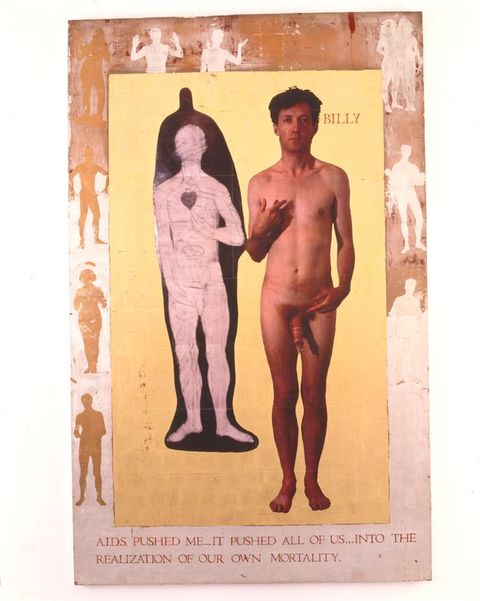

The Irish Museum of Modern Art (IMMA), which opened in 1991, has been a consistent supporter of queer artists. One example is its championing of Billy Quinn. Born in Dublin in 1954, Quinn had been based in New York, producing work that addressed queer identity and the AIDS crisis in a direct and confrontational manner. He returned to Ireland as IMMA’s artist-in-residence from 1995 to 1996, continuing his Icons series. Using the aesthetics of religious iconography, these large works reclaimed the representation of those affected by AIDS, shifting the focus from pathologisation and Catholic moral judgement to individual dignity, identity, and humanity. Billy (1991) is an almost life-size self-portrait of the artist, naked except for a condom (fig. 3). The inscription “AIDS pushed me … it pushed all of us … into the realization of our own mortality” encapsulates the tension between personal grief and collective activism that defined much of Quinn’s work. IMMA acquired three of Quinn’s works for the National Collection, exhibited them nationally and internationally, and featured them regularly in publications—affirming both their artistic significance and their political message. However, programming is shaped by the interests and agendas of an institution’s curators. Queer programming can ebb and flow, with periods of strong support, mentorship, and visibility often aligning with the presence of individuals whose identity position may shape institutional priorities.

Governed by two centrist parties since the 1980s, often with progressive Labour or Green support, Ireland has maintained stability in public policy, while the end of austerity a decade ago has brought consistency and some increases in funding for cultural and educational institutions. Yet public institutions now face mounting challenges as right-wing actors exploit social media to generate outrage, making state-funded spaces vulnerable targets. The threat lies less in government policy itself than in the pressure on governments to appear responsive to individual demands. The challenge is how these institutions sustain their queer programming while navigating an increasingly hostile digital landscape.

Response by

-

Owen G. ParryArtist, writer, and Senior Lecturer in Critical Studies Fine ArtCentral Saint Martins, University of the Arts London

Adrian Street’s Welsh Working-Class “Exotic”

I encountered this photograph of the late ex-coal miner cum Welsh professional wrestler, popstar, and artworld pin-up Adrian Street (1940–2023) rather unexpectedly while on a student trip to Paris in November 2008 (fig. 4). It hung at the doors of the Palais de Tokyo, announcing From One Revolution to Another (2008), an exhibition curated by the English artist Jeremy Deller. Based on elements of Deller and Alan Kane’s Folk Archive (2005) of quirky British artefacts, the show explored the relationship between Britain’s industrial and cultural revolutions and included Street as its charismatic mascot. I am interested in the ways this image tells another story. As a defiantly working-class image in which Street’s queerness is assumed to be an elaborate act, it is also disengaged from the narratives and politics of gay and lesbian liberation of the time. As such it tells a parallel yet distinct story, where queerness is incorporated into a burgeoning neoliberalism precisely at the moment that it finds its liberation in the West but, importantly, not only this.

I call this an encounter because this photograph stirred something in me that was both familiar and strange. I grew up in the south Wales valleys in the 1980s and 1990s, among the ruins of mine closures and in the aftermath of glam rock, which was transmitted via TV and radio into our house, often simultaneously. While I could not immediately put a name to the face or place in this beguiling image, I felt it in my bones: the damp air, the feathers, sequins, coal make-up, peroxide, and the steel toecaps. Seeing this image hung outside one of Paris’s prominent centres for contemporary art also spoke to some as yet unexplored feelings about my own queerness and upward migration through the British class and education system.

I learned from Deller’s show that this was a “revenge photograph”: a “fuck you” to Street’s father, who is featured, and to colliery workers who, according to Street, denigrated and mocked him as a fantasist for his aspiration to leave Bryn-Mawr Colliery to become a wrestling star.13 Street left the colliery for London in the 1960s, wrestling for money in funfairs and modelling for men’s magazines, while setting up gigs and developing his outrageous “exotic” wrestling persona, which he took to the United States in the 1980s and where he remained until his return to Brynmawr in 2018, where he died at the age of eighty-three on 23 July 2023.

13In the world of wrestling Street was a heel, a villain rather than a hero. His signature move in the ring was to pin down his opponents, put make-up on them, and give them a lovely big kiss. Accompanied to the ring by his beloved wife, Linda, Street performed the straight man in sequins, or “sadist in sequins” (as he named his 1986 hit pop song and his 2012 autobiography), deliberately provoking a reaction from the often homophobic wrestling audience, much to Street’s delight. “I was getting far more reaction than I’d ever got just playing this poof”, he noted. “My costumes started getting wilder”.14

14This photograph works to verify Street’s personal mythology, but for Deller it is also one of the single most significant images of twentieth-century Britain, prophetic in the way it foresaw Britain’s economic transition from a centre of heavy coal industry to a global producer of entertainment and services.15 While Street’s flamboyant act has gained him renewed attention in art, little has been said about his “exotic” homosexual gimmick as the vehicle for his success.

15A contradictory figure in terms of queer history, Street apparently mingled with gay men and the Soho underworld and made repeated claims to have invented glam rock, which influenced artists from David Bowie and Marc Bolan to Elton John and Boy George.16 More recently, Street was featured in Out in the Ring (2022), a documentary exploring queer representation across a history of wrestling from the 1940s to the present. While Street’s exaggerated performance engages what I have called elsewhere “fictional realness”, I am struck by how this image poses challenges to the queer archive, which tends to recuperative narratives of liberation that can too easily sanitise, commodify, and eradicate class.17 Street’s life and work are completely devoid of the real-life struggles, politics, and lived experiences of LGBTQ+ folk during this period. A parallel, yet very different story of community and solidarity, is told in the film Pride (2014), a compelling look at the coalitions forged between queer activists and striking coal miners in south Wales in the 1980s. Pride serves as a heartwarming recuperative narrative, which contributes to its mainstream success, but it also eschews the broader complexities of Thatcher’s neoliberal entrepreneurialism and incorporation of queerness into the mainstream, especially when performed by a heteroflexible frontman. Nevertheless, to relegate Street’s contribution to queerbaiting—or to “gay-for-pay”, a legacy of queer exploitation in visual culture—would be to tidy up and straighten out the way class intersects with queerness in complex, often idiosyncratic ways.

16While the coal mine serves as a backdrop to both Street’s and Britain’s past in this image, Street’s “exotic” queer embodiment suggests a future in which queerness may be employed as a tenable gimmick. For Street, his homosexual gimmick is what enabled his spectacular transit from the coal mine to mainstream fame. As James Baldwin once wrote of the gimmick’s fugitive function: it is most certainly a lever “to lift him out, to start him on his way”.18 Sianne Ngai reminds us that “the gimmick strikes us both as working too little (a labour-saving trick) and as working too hard (a strained effort to get our attention)”.19 In Street’s case the gimmick is also what makes his queer performance so spectacularly unconvincing. Unapologetically brash yet sentimental, camp but also straightish, this “revenge pic” refuses to line up neatly with queer history. A homosexual satire, it remains parallel to queer history, exposing its doublings and multiple temporalities. Street’s working-class act is a nagging insistence on queer’s own fugitive possibilities.

18I am not a wrestling fan, but for me as a kid in the 1990s there was a moment: two life-size posters of WWF wrestlers Bret “the Hitman” Hart and The Undertaker framed my bed like two mythic columns. I soon grew out of wrestling but I cannot deny how powerful it was to encounter Street’s photograph at a Paris museum. A revenge image for Street, an economic prophesy for Deller, and some kind of reconciliation with sexuality, education, and class for me. It is a generous image that continues to fascinate and aggravate, effects evoked not so much by the heel’s cue—that is, Street’s deliberate queer farce and the potential maintenance of his audience’s homophobic reaction—but rather in the messy feelings and residues of affect, including shame, that can arise in any recuperation or instituting of sexuality and class. For better and for worse, this photograph demands to be seen otherwise.

Response by

-

Campbell XFilm, TV, and theatre writer and director

The Unbearable Whiteness™ of Seeing

In 1970 Huey P. Newton, one of the co-founders of the Black Panther Party in the United States, gave a speech in which he supported the rights of homosexuals and their relationship to revolutionary struggle:

21We have not said much about the homosexual at all, but we must relate to the homosexual movement because it is a real thing. And I know through reading, and through my life experience and observations that homosexuals are not given freedom and liberty by anyone in the society. They might be the most oppressed people in the society.21

In the same year, the UK Gay Liberation Front was founded by Bob Mellors and Aubrey Walter, inspired after they attended the Black Panthers’ Revolutionary People’s Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia.

Our roots of global LGBTQIA+ liberation have been spearheaded by global majority-descended people. Yet White™–centred creativity, including those by white cis gay men, is put up as the benchmark by which great art is measured. Global majority queer artists are judged by their inherent proximity to those White™ references, practices, and values.

This has consistently been critiqued by global majority artists. In recent years, the response of arts institutions to these critiques is usually a flurry of panic measures to include those who are “othered”. One year the focus might be disability, another year race, another year class or region. However, nothing changes at the core of those art institutions. This takes a toll on the creative output and mental health of those who have been systematically excluded.

We are consistently informed that British arts institutions are doing everything they can to diversify their output and staff. Yet how often do they actively work to dismantle the problematic foundations that those institutions are built on?

For instance, the British Film Institute was formed in 1933 during a decade that saw the British Empire at its peak, exercising colonial control over 25 per cent of the planet and a policy of appeasement towards Nazi Germany. These histories have a resonance for me today in the current government’s complicity with fascist and right-wing positions and in art institutions’ reluctance to publicly call out present-day colonisation and genocide.

The British Film Institute state proudly on their website that they are governed by a royal charter. A royal charter is granted by the British monarch, who is the de facto head of the Church of England. In my view, the charter’s symbolic endorsement of a single faith and of the greatest beneficiaries of empire intrinsically excludes and demotes the perspectives, values, and traditions of people from the global majority. What message does this send to British people descended from ancestors who were trafficked in the transatlantic slave trade and/or colonised, looted from, murdered, deliberately starved?

The reliance of arts institutions on representational optricks has led to inclusion without a truly radical anti-colonial ethos. We are in denial when we claim that any British institution formed when there was legal subjugation of global majority people and discrimination against LGBTQIA+ people can have unshakeable, robust diversity and inclusion policies without addressing the enduring legacies of this oppression. This is structural and systemic. Ancestor Audre Lorde argued that “the master’s tool will never dismantle the master’s house. They may allow us temporarily to beat him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change”.22 Without radical inclusion, UK art institutions will continue to put a diversity and inclusion plaster on the open decaying wound of systemic Whiteness™.

22To have permanent change, all arts institutions need to acknowledge the decades of harm they have caused to global majority disenfranchised artists and creators. They need to “dismantle the master’s house” permanently. They need to rebuild systems that actively support processes and creative products that build and sustain careers of those who are not white cishet middle-class men. They need to repair damage in their historic funding output/systems to global majority descent people in the United Kingdom, marginalised LGBTQIA+ people, white working-class people, and/or disabled people who belong to disenfranchised groups of people in terms of brutal cultural and legal discrimination because of their marginalised religion, sexual orientation, and gender. Repair also includes ending practices that reinforce border policing in terms of nationality/nation that have been complicated by ethnicity and immigration as a result of the legacy of colonisation.

It’s time for less talk and more action. This anti-colonial work of dismantling and unseeing Whiteness™ will be met with an inevitable backlash. However, if we truly want permanent change we will need to overcome our fears—of loss of jobs, familial bonds, comfort. As Sara Ahmed writes in Living a Feminist Life: “If we are not exterior to the problem under investigation, we too are the problem under investigation. Diversity work is messy, even dirty, work”.23 In doing the work I believe it’s possible to build green shoots of community care, compassion, and true global solidarity among those of us who share the same dream.

23Response by

-

Helena ReckittReader in Curating in the Department of ArtGoldsmiths, University of London

An Honest Conversation, Hard to Hold: “Does It Come in Another Colour?” and “Racing Desire” at London’s ICA

When the poet and film curator Ian Iqbal Rashid moved to London from Toronto in 1990, two things struck him about the city’s queer cultural community: first, the abundance and range of spaces and sexual possibilities on offer; and second, the paucity of public discourse about racialised desire.

I met Rashid shortly after he had moved to London, at a literary event featuring British-based South Asian writers that I had organised at the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA), London, where I was deputy and acting head of talks from 1990 to 1997. A couple of years later, in 1993, we co-organised “Racing Desire: Doing It in Colour on Film and Video”, a symposium exploring interracial dynamics that accompanied the film programme Rashid was curating for the ICA’s Cinemateque, “Does It Come in Another Colour?”

Rashid was no stranger to being othered. His 1991 poetry collection Black Markets, White Boyfriends and Other Acts of Elision reflects his experience of being both subject and object of the racialised gaze. In the poem “Another Country” the narrator’s white boyfriend becomes aroused as he watches the colonial Sergeant Merrick whipping Hari Kumar into submission in the 1984 BBC TV series The Jewel in the Crown. Fondling himself as he fantasises about the “imperial wealth” of his lover’s penis, the narrator “closes his eyes and thinks of England”.24

24In London, Rashid devised an artists’ film series that resonated with his experience of hybrid identities and cross-cultural identifications. Wary of expectation that artists from marginalised groups should counter negative or stereotypical depictions, he was drawn to work that was marked by irreverence, questioning, ambiguity, and play.

The ICA’s strong track record for championing queer artists and critical debate was established in the late 1980s through programmes such as the 1988 “Taking Liberties: AIDS and Cultural Politics” symposium, organised by talks director Erica Carter and AIDS activist and critic Simon Watney. The ICA was therefore the obvious London venue to approach, and deputy director of cinema Tim Highsted eagerly accepted Rashid’s curatorial proposal. Highly visible himself as an out gay film programmer, Highsted had organised the landmark 1991 “New Queer Cinema” conference, which featured US film critic B. Ruby Rich, along with the trailblazing producer Christine Vachon and film-maker Todd Haynes. Highsted scheduled Rashid’s series for October 1993, which turned out to be a high point for queer, as well as feminist, programming at the ICA. In the same month the gallery featured Bad Girls, a playful exhibition showing established artists Helen Chadwick, Nan Goldin, and Sue Williams alongside emerging figures Dorothy Cross, Nicole Eisenman, and Rachel Evans. Live art programmes “Fierce” and “Respect”, under the direction of Lois Keidan and Catherine Ugwu, celebrated queer, female, and Black artists. Meanwhile, in its talks programme, Judith Butler lectured on subjection, while queer writers Adam Mars Jones and Gary Indiana were in conversation (the latter reportedly lured for post-talk sex in the toilets by one of the ICA’s queer invigilators).

“Does It Come in Another Colour?”, Rashid’s two-week season for the ICA Cinemateque, staged a predominantly cross-Atlantic dialogue. Billed as “Hysterical, sexy, moving, naughty and ‘incorrect’”,25 the series grouped films into three evening programmes: “Racing Queer”, “Yearning”, and “Other Passions”. Cultural translations and misunderstandings characterised various selections. Evan Dunlap and Adrienne Jenik’s What’s the Difference Between a Yam and a Sweet Potato? (1992) explored tropes of food, skin colour, and erotic play in Caribbean culture. In Vanilla Sex (1992), Cheryl Dunye showed slippages of meaning and nuance across Black and white queer slang. In his already celebrated Looking for Langston (1989), Isaac Julien imaginatively recreated the homoerotic milieu of the Harlem Renaissance. Driven by the conviction that “Black men loving black men is the revolutionary act”, Marlon Riggs’s polyphonic Tongues Untied (1989) depicted the beauty and precarity of Black American queer life and interracial desire. The Body Beautiful (1990), by British Nigerian film-maker Ngozi Onwurah, focused on her relationship with her white mother to examine conventions of female sexuality and desirability (fig. 5). Privilege (1990), the only feature film included, by white US artist Yvonne Rainer, mined intersections of race and gender, sexuality and ageing, with African American actor Novella Nelson playing Rainer’s onscreen double, Yvonne.

25

“Racing Desire”, the accompanying two-day symposium that Rashid and I devised for ICA Talks, also featured a cross-Atlantic line-up. The cultural studies scholar Lola Young considered Hollywood’s foundational preoccupation with “miscegenation” across D. W. Griffith’s controversial oeuvre. The Toronto film-maker Richard Fung presented Looking for My Penis, on stereotypes of passivity and femininity in pornographic depictions of East and South-East Asian men. Richard Dyer spoke on dazzling, yet complex, portrayals of white women in classic Hollywood film, examining how ideals of beauty and purity shape representations of whiteness.

My memory of the event is of a visceral sense of excitement that difficult and taboo issues were being publicly aired. Far from being abstract debates, these discussions grew out of the lived experiences of speakers and audience members alike. I remember the symposium causing me to reflect on my own experience as a white woman who had recently dated a Black woman. Not only had our presence as a mixed-heritage queer couple provoked the predictable curiosity, and sometimes hostility, of straight men, but it had also given me a new sense of being seen by Black women. Yet, for all its irreverence and playfulness, honesty and daring, some conversations that Rashid hoped “Racing Desire” would stimulate proved too hard to hold. A late change to the symposium schedule replaced a conversation between himself and Julien with a preview of Julien’s The Attendant, featuring the prominent academic Stuart Hall as a fantasising museum guard. Instead of the planned conversation with Julien, Rashid invited a white British film-maker to screen his short featuring young Moroccan men and boys performing for his camera in various states of undress.26 While Rashid found the film problematic on many levels, he nonetheless appreciated its honest evocation of exhibitionism and voyeurism. But the candid post-screening discussion of cross-generational and cross-racial desire he had anticipated did not take place. Hostile and affronted, audience members shouted down the film-maker, accusing him of sexual tourism—and worse. Clearly, even in the ICA’s progressive, queer-friendly environment, some conversations were too sensitive to stomach.

26Interviewing Rashid for this article brought home to me the unreliability of memory. Over two online conversations, including one with Highsted, and several follow-up emails, we attempted to recall events that had taken place over thirty years ago. Institutional records were not much help: audio recordings of ICA Talks archived at the British Library remain hard to access following the devastating cyberattack on the library in 2023. It took the personal intervention of past and present ICA workers—the associate curator of artists’ film and moving image Steven Cairns and the former live arts director Lois Keidan, who copied pages from the October 1993 ICA Bulletin—for Rashid and me to piece together our memories.

Looking back, Rashid regards early 1990s London as a “strikingly rare, dynamic and revelatory” time.27 Even if his ICA programme proved to be somewhat volatile and divisive, he recalls a tangible need among artists, organisers, and audiences to ask difficult questions about difference and desire, and their cultural representation.

27Response by

-

Dominic JohnsonProfessor of Performance and Visual CultureQueen Mary University of London

After Betrayal

Britain’s institutions are adept at professing inclusion while practising containment. The challenge is to persist in refusal or rupture: to recognise that institutional intrusion is a stifling embrace, that visibility is not agency, and that there is cachet in remaining illegible, intransigent, and invisible.

The above is a common claim of the queer Left and one I am tempted to affirm (as an avowal of negation) in response to the editors’ useful provocation. However, such a claim falters under the material conditions of real-life application, particularly in the domain of artistic production, curation, and display. Their provocation—and my rehearsed response above—risks conflating visibility and canonicity, presentation and containment, and assumes that queer art always loses its edge when museums, galleries, and universities acknowledge it. What the editors ask is: how is queerness allowed to appear, under what terms, to what extent, and at what costs? They suggest that institutional appearance depoliticises queer work and erases the community-driven networks that often first sustained it. Their provocation displays a familiar scepticism about how queer culture is domesticated into a stable, marketable category and therefore no longer functions as a prompt to disruption and transgression; assumes that recognition obscures rather than honours the past; and presupposes that monographic exhibitions prioritise individual success over collective struggle.

The editors’ concerns are posed in relation to a series of exhibitions of queer art in institutional contexts, including Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, which I curated with Seán Kissane and Gilane Tawadros at the Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin, in 2024–25. It is currently on display at the Whitechapel Gallery, London, for the summer of 2025. Butt was British South Asian, queer, Muslim by upbringing, and HIV-positive. He died of an AIDS-related illness in 1994, aged thirty-two. The exhibition is more thematically concerned with AIDS as a historical context that with queerness as a political category. The exhibition catalogue, promotional materials, and wall texts insist on the central relevance of AIDS to the creation of the works and to how the works produce (and arguably frustrate) meaning. The works are difficult to install because they contain dangerous materials, threaten to toxify the environment of the gallery, rely on volatile technological components, or risk injury to those who encounter them. It would not be feasible or practical to install them in “grassroots” spaces.

Is siting such a retrospective (the first of its kind) and such works in two major institutions a betrayal of their queer potential? The artist’s works were rarely exhibited in his lifetime, and in London were only ever shown at Milch, which was first a squat and later an itinerant semi-commercial gallery, where the logics of funding, health, and safety and of public palatability were secondary to the creative vision of artists in concert with that of the maverick curator Lawren Maben. Yet both of Butt’s best-known works, Transmission (1990) and Familiars (1992), were first shown in institutional spaces, respectively at Goldsmiths’ College, London, and at John Hansard Gallery, Southampton (fig. 6). At the latter, the curator Stephen Foster enthusiastically supported Butt in fabricating and installing his difficult works. While it might be ideologically convenient, it would be a mistake to claim that the entry of these queer works into institutional spaces is necessarily counter to their initial scenes of production or exhibition, or that it inevitably resembles a process of belated containment. Institutions are not static or monolithic; they are porous, contested, and subject to change through pressure, critique, and participation as well as by paying attention to the people who work inside them, especially those who do so against the grain.

We need to find ways to pay attention to queer artists without condemning them to an often materially unliveable outside, and without reifying them as unsalvageable or as outsiders. Otherwise, we may end up reifying a series of double binds characteristic of both the Left and queer politics, as predicaments that have arguably become inevitable and intractable in recent years, as a culture of grievance, and claims to identity based substantially on victimisation, make political gains harder and harder. Paul Preciado identifies an “epistemic gap … between the theory and practices of the … left and its discourses around class struggle and political ecology, and the political grammar and practices of resistance and emancipation of racial, gender and sexual minorities”, and argues that this gap has been “exacerbated by neoliberal politics and the essentialization of identities” in recent years.28 Such gaps or double binds in the politicisation of the presentation of queer art include the conflict between visibility and co-optation, whereby marginalised groups seek legitimacy and recognition but then critique its effects as depoliticising, as undoing autonomy, or as commodification by mainstream culture and market forces. There are, of course, potential (or perhaps inevitable) deformations and inhibitions to queer art on entry into museums: elisions take place to prevent insult or blowback, especially those that may be caused by erotic or pornographic content; and works are narrated anew to re- or decontextualise them and to (deliberately or tacitly) camouflage circumstances that might now cause trouble or impede accessibility (typically a kind of dumbing down redescribed as democratisation or diversification). Yet it is a category error to see the basic fact of institutional entry as a political own goal for queer art and artists. Reasonable compromise is perhaps a necessary evil in the context of a larger tension between theory and practice, in which the individual application of theoretical principles in real-world situations—for example, curating exhibitions of previously overlooked artists in institutions of art—creates pragmatic gains that do not always align with the collective’s fantasy of ideological purity. As Wendy Brown writes, we need a more specific and “local” model of cultural intervention that “replaces critique of an imagined social totality and an ambition of total transformation with critique of historically specific and local constellations of power and an ambition to refigure political possibility against the seeming givenness of the present”.29

28Rather than assuming that institutional engagement is a betrayal of queer art’s insurgent roots, we might instead ask: How are queer artists and curators leveraging institutional power, however partially and provisionally, for our own political ends? How are these venues shifting, however incrementally, in response to our presence? And do we risk romanticising our exclusion as freedom at the expense of recognising the expanded material gains and other imaginative possibilities that institutional access can offer?

Response by

-

Michael PetryArtist, author, and DirectorMuseum of Contemporary Art (MOCA), London

Hidden Histories and Curating Queer Art

“Faggot”, “fudge packer”, “arse bandit”, “bum boy”, “cocksucker”, “fairy”, “flamer”, “pansy”, “fruit”, “gaylord”, “homo”, “nancy”, “bender”, “bent”, “swish”, “sissy”, “shirt lifter” (that was a new one for me), “batty boy” (ditto), and of course “queer” were all terms thrown at me in the 1980s and, sadly, even fairly recently. These words were used as weapons, and word bombs could explode anywhere, including in artistic environments. Museums and galleries were not necessarily safe spaces for visiting “homosexuals”.

Members of the LGBT community tended to find solace in each other’s arms. Many gay men of my generation (post-Stonewall/pre-AIDS) were raised in a queer community that saw themselves as an “army of lovers”. You were encouraged to have as many partners (marriage equality was a chimera then) and with as diverse a group of people as possible. It made for an exciting time. Change grew from a 1960s hope that community could be more than the 1950s dream of white heteronormativity. This wonderful experiment had obvious drawbacks when it came to sexual health, but I never let anyone use the word “promiscuity” around me. He who is without sin and all that.

I wrote about many UK-based queer artists, including Ajamu, Anya Gallaccio, Sunil Gupta, Maggi Hambling, Isaac Julien, and Sadie Lee, long before others would acknowledge their importance.30 I put them in shows in warehouses (now luxury flats) and non-institutional, non-queer spaces like the Museum of Installation, where I was co-director from 1990 to 2004.31 Even there, I got push-back. How do we say, “More straight artists please”?

30I was often the only queer in the room. In the 1980s queer artists were a lot like that “army of lovers” (and many of us had been or were lovers). We were a smallish group and had to stick together to help each other out, and that included end-of-life care as much as lending a hand to paint gallery or studio walls for an exhibition. My own lover was very old-school, out but from a “good” family. His academic friends were “shirt lifters”, who often hated that I was openly queer. Homophobia is learned, and many gay men at the time (and sadly now) despised themselves and other queers. The “angry gays”, like me, took to “queer” like the proverbial.

In 2004 I was asked to curate Hidden Histories: 20th Century Male Same Sex Lovers in the Visual Arts at the New Art Gallery Walsall, its first major international exhibition, and author its survey book.32 Some of the featured artists had never allowed their work to be shown in a queer context before (including the love triangle of Robert Rauschenberg, Cy Twombly, and Jasper Johns). After much discussion, it was decided that the exhibition would exclude women, with stakeholders deeming it inappropriate for me, a man, to speak for women. It was hoped that a second exhibition about and curated by women would follow (it did not). The show included major loans, including a Francis Bacon painting of a male lover. One important loan was Félix González-Torres’s "Untitled" (Portrait of Ross in L.A.), an homage to his partner, Ross Laycock, who died of AIDS (fig. 7). The local Labour council objected to its inclusion, accusing the artist—and me—of trying to “tempt” children into what I’ll politely call “homosexuality with candy”. They threatened to lock the museum if it was installed. So it wasn’t. At the opening, they turned up and loudly abused me and the staff until a local eighty-year-old woman guest scolded them and forced them to leave.

32

The show was a huge success, yet twenty years later the same González-Torres work was the subject of controversy in an exhibition at the Smithsonian, where the wall text all but erased Ross as his lover and the fact that both men died of HIV/AIDS.33 I have written at length about the power of the institutional wall label and how it can direct or misdirect the viewer about any given work.34 Though some information regarding Ross was available elsewhere in the room, many viewers might not have seen it or connected the two texts. Whether intentional or not, such ambiguity echoes broader tendencies I have observed in exhibitions of work by Robert Rauschenberg, Cy Twombly, Jasper Johns, Andy Warhol and so many other high-value artists. In those cases, the estates or galleries involved have often appeared to de-queer the artists so as to preserve their work’s commercial appeal in more conservative markets. It seems one step forward …

33I have long advocated for change in the academy and the museum, and while it has been slow and mainly decorative I remain hopeful. I’m happy that some friends are now included in institutional spaces, but at the same time I know how shallow those inclusions can be and how easily institutions could backslide (not a gay term but a religious Texan one). Still, I believe in looking hard and seeing where you really are, then going out to change what you can.

Response by

-

Irene RevellLecturer on the MFA CuratingGoldsmiths, University of London

Humans of the Institution(s)

In heeding the provocation’s much needed call to attend to the potentially appropriative relationship between “hegemonic institutions … and grassroots oppositional work”, I would like to further propose a queering of this very relation, that is, to think beyond the binary of institutions versus grassroots towards a nuanced ecology that, at its most hopeful, could consist of “humans of the institution” who exist in constellations that spill between these at times porous categories.35 For my part, my work has spanned establishing and (co-)directing the now defunct curatorial organisation Electra, which (depending on one’s point of view) was very much institutional (with legal status and regular funding) and yet at the same time still a minnow, working repeatedly with Tate, among many partners of multiple scales (fig. 8).36 Meanwhile, I had come out of, and continue to be involved in, queer DIY and self-organised cultural production—including the London club night Homocrime (2003–6) and the queer punk band Woolf (2009–18), sometimes artworld-adjacent but often far from it—while being situated, for now, in another institution—academia—and eluding a chrononormative career path, as many of us inevitably do.

35

Staying with the Tate exhibitions Queer British Art and Women in Revolt!, I suggest it is precisely in their contrast that we might tease out some of these complexities. Queer British Art (2017) emerged within a wider landscape of national institutions marking the fiftieth anniversary of the partial decriminalisation of male homosexuality in England. My own enduring memory is not of the exhibition itself but of the rainbow flag that flew above Tate Britain throughout: a queasy image that captures some of the deep unease held in the titular words “queer” and “British”—a contradiction in terms if “queer” is to retain any critical valency. That is, any viable queer politics must heed the inherent homonationalism implied in this particular celebration of Britain, not least while the very same law festers as a deadly legacy in numerous former colonies. The flag as “outreach complex” par excellence, taken down as soon as the works, briefly reanimated in the exhibition, are returned to the collections whose underlying operations, we imagine, remain fundamentally unchanged.37 Conversely, Women in Revolt! (2023–24) was the passion project (and ultimately swansong) of the curator of British contemporary art, Linsey Young. The vast majority of the works included were not in the national collection nor indeed in any art collection; rather, they were drawn from individual artists and researchers and from the many community organisations such as the volunteer-run film and video distributor Cinenova. As such, the exhibition immediately challenged the status of the collectible, pointing kaleidoscopically to this broader array with what Young describes as the hope of “building relationships rather than simply extracting information”—a potential that can truly start to take hold only through a reimagining of the institution itself.38

37These interdependencies within a broader ecosystem and across scales may also exist within institutions, which means that, in order to understand what sets the scene for any blockbuster show, we may need to look beyond exhibition-making. The Tate Film programme emerged from public programmes, and under the first curator of film Stuart Comer’s tenure gave rise to a concerted focus on queer artists, with Barbara Hammer’s nineteen-part retrospective The Fearless Frame (2012) at its apex.39 Following suit almost immediately was Charming for the Revolution: A Congress for Gender Talents and Wildness (2013), a two-day live programme that took place in the newly inaugurated Tanks, a co-presentation between Tate Film and my organisation, Electra, bringing together works by Pauline Boudry / Renate Lorenz, Carlos Motta, and Wu Tsang. These projects exemplify the shifting possibilities afforded by the wider zeitgeist discussed in the provocation and, most significantly, just preceding the numerous waves of austerity that initially affected smaller organisations and more recently Tate itself.40 Electra was to have its decade-long Arts Council funding withdrawn the following year, in part and, to paraphrase, because “there are lots of larger institutions doing this work now”.41 Even if it is based on an anecdotal assumption, this moment makes starkly clear what is at stake in such an exchange between small-scale, grassroots, and community organisations and larger institutions.

39While the possibility of such topics “ascending” into the exhibition programme in the intervening decade is undisputed, the essential question is perhaps one of resilience: how, and ultimately where, that may remain possible, especially when these more nuanced relationships between different scales of organisation and activity are not better understood, never mind nurtured. After all, in each of these examples it is the sheer force of individuals, albeit with collegial support within the many collaborations, that has produced paradigm-shifting programming but that may just as well spell impermanence without any accompanying institutional shift. If these achievements are to be more than high-water marks before the combined hands of austerity and culture wars snuff out any pockets of institutional oxygen, it is the very reimagining of the institution as a multicentred organism, composed first and foremost of its workers and existing interdependently with many other kinds of organisation, that offers any promise of queer futurity.

Response by

-

Sunil GuptaProfessor of PhotographyUniversity for the Creative Arts

Full Circle: The Culture Wars Are Back

I think there is something to be said, investigated, and re-examined about the end of the 1980s, when lesbian and gay art in Britain made itself known increasingly and began its transformation into queer art. For me the decade represented a great coming together of diverse practices, of voices that were locked in battle for scarce resources from local authorities, of community spaces and universities, to produce new works.

My own battle started in art school, where a Eurocentric postmodern art history had taken no notice of postcolonialism or anything gay that might divert it from an imaginary universal subjectivity. With some like-minded fellow students, I installed a separate Black graduation show at the Royal College of Art (RCA) in 1983. It involved getting a room in the same building as the main degree shows and showing the work of several students across art forms, including several from graphics, only one of whom—Ruhi Hamid, now a documentary film-maker—I still know, and who designed the cover of the RCA catalogue that year. It was a novel show for the RCA, and some curious people did come. Of course, we were more interested in inviting our allies in the town halls and especially the Greater London Council (GLC). I was invited back to the GLC’s Race Equality Unit, and it changed the direction of my work. We had also concluded that the art market was of no use to our broader aims of liberating society. We refused to engage with Cork Street and saw fine art as a primarily bourgeois commodity exchange.

But it was also a time of great separatism: women made work about women, gay men about gay men, lesbians about lesbians, and Black people about Black people. This was reflected in the kind of choices you were able to make: which kinds of activist meetings you could go to, which kinds of bars and clubs you could hang out in to meet like-minded people. For me, it was also a time when few Asians were out and even fewer made artwork of any kind, but I didn’t let it worry me and became Black-identified in the GLC sense.42 The art institutions were not interested in us, the larger group of Black and white artists who felt art had a social purpose outside of the market, and we were not interested in them. For example, I thought of the Tate as the “enemy”, with sugar and slavery embedded in its name. They were uninterested in us because we mostly came from lens-based mediums with an avowedly anti-fine-art practice. British institutions also suffered from a class problem in that the curators came from privileged educational backgrounds and were mostly straight white women, while the technicians came from working-class backgrounds and were mostly white men, and the security staff were mostly Black. Photography as a medium uniquely saw a series of metropolitan local-authority-funded workshops and spaces involving darkrooms, galleries, and educational programmes such as Camerawork in London’s Bethnal Green. It was there that we had the first LGBT photo show, to my knowledge, Same Difference in 1986, organised by Jean Fraser and myself. Challenging those straight white institutional curators face to face was fun but unproductive. One told me Rotimi Fani-Kayode’s work was like a wannabe Robert Mapplethorpe’s, only not as good; they decided what was good. Undaunted, we went off to do our own thing, including curating, starting Autograph—as a collective not an institution—and joining forces with the lesbians Jean Fraser and Tessa Boffin in my case. It brought race and LGBT together in my practice. I made pictures of white women. All those government policies—around AIDS and Clause 28 (later Section 28 of the Local Government Act 1988) and the lack of legal recognition of LGBT relationships—to make oppositional work about.

42All of this was happening without the market and without institutional support. Everyone went to a lot of demonstrations about issues that mattered to everyone, not just about sexuality and race but also about the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) and the miners’ strikes. It’s where I met my larger community of lesbian and gay friends, including the former members of the Gay Left group like Simon Watney and Emmanuel Cooper (fig. 9—pictured here with his long-term partner, David Horbury). I think the 1980s was a time when community mattered, and this was the thing Margaret Thatcher wanted to split apart. She succeeded, and the market ushered in the Young British Artists (YBAs), and Tony Blair got Cool Britannia, and we who had been very active saw our resources, such as local authority and Arts Council funding, dry up and the market take over our aesthetic ideas. For example, the YBAs were riffing on ideas around autobiography that had been around Black arts for a decade, unrecognised and unreferenced. Tracy Emin’s Bed was preceded by the lesbian Indigenous artist Destiny Deacon’s work in Melbourne, which I encountered in person in the mid-1990s while researching my curatorial project The New Republics: Art from Australia, Canada and South Africa. It doesn’t surprise me that Tate and other institutions now want to historicise everything and put it to bed. Lisette Model, my great teacher, told me in 1976, “Darling, when your work is dead, it will be in a museum”.

So, if we return to the 1980s, what can we learn? That community matters. That we are not living in a bubble, as the internet would have us believe. That it’s our job to save the world.

About the authors

-

Laura Guy is a Reader in Gender, Sexuality, and Culture at the Glasgow School of Art. Her writing on the interactions of art and design with feminist and queer politics has been published widely. She is co-editor with Glyn Davis of Queer Print in Europe (Bloomsbury, 2022) and editor of Phyllis Christopher’s artist monograph Dark Room: San Francisco Sex and Politics, 1988–2003 (Book Works, 2022). In 2023–24, she was principal investigator on the Carnegie Trust-funded research project “Remapping the City of Culture through Grassroots LGBTQ+ Cultural Production”. With Fiona Anderson, Flora Dunster, and Theo Gordon, she is co-editor of this special issue of British Art Studies dedicated to queer art in Britain since the 1980s.

-

Theo Gordon is Leverhulme Early Career Fellow in History of Art at the University of York, working on a book provisionally titled “Viral Landscapes: Art and HIV/AIDS in the UK”, due in 2026. He has published widely on modern and contemporary art, with essays on Helen Chadwick, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Douglas Crimp, Sunil Gupta, and other artists in journals including Oxford Art Journal, Art History, and InVisible Culture, and reviews regularly for Burlington Contemporary. He is co-author with Flora Dunster of Photography—A Queer History (2024) and editor of We Were Here (2022), a book of Gupta’s essays for Aperture.

Footnotes

-

1

Simon Watney, “School’s Out” (1991), in Imagine Hope: AIDS and Gay Identity (London: Routledge, 2000), 40. ↩︎

-

2