Correspondences and Fractures

Correspondences and Fractures: Lesbians Talk Queer Formations

Interview by Laura Guy With Cherry Smyth

Abstract

This interview between the poet Cherry Smyth and the writer Laura Guy focuses on Smyth’s contribution to feminist and queer activism and cultural production after she arrived in London from Ireland in the early 1980s. The conversation covers a range of activities in which Smyth was involved in the ensuing years, including the Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp and the Troops Out Movement; feminist and community film and video production; Irish women’s writing and her contribution as a cultural critic to the formation of new queer perspectives and politics in the early 1990s, particularly in her books Lesbians Talk: Queer Notions (1992) and Damn Fine Art: By New Lesbian Artists (1996). In the correspondences and fractures signalled by these connected yet heterogeneous practices, the category of “queer” emerges as a site of potentiality not only in the recent past but also for a younger generation of artists working in Ireland today.

Introduction

The eighties are on the horizon the first time I meet Cherry Smyth. It’s 2012. We’re introduced by a mutual friend, the artist Margareta Kern, who drives a small group of us from east London to the Kent coast for the Whitstable Biennale. Margareta has programmed an evening of videos documenting women’s activism and self-organising during the miners’ strike of 1984 and 1985.1 It is the first weekend of September and the event takes place outside, at a temporary cinema that P. Staff has conceived for the festival (fig. 1). We sit at the harbour in our coats, watching staticky images of industrial action. The screen is installed in front of an asphalt factory, a reminder that industry and its decline belong to parts of the south as well as to the north. That evening, Margareta tells the audience stories about Kent miners who were part of the national strike.

1

The miners’ strike is among the most significant events in the timeline of political upheaval that demarcates the 1980s. A year-long struggle, the strike signals the long-term effects that Thatcherite policy would have on Britain. Margareta and I connect on train journeys to Durham through a shared interest in returning to this decade. She is an artist in residence at Durham University, and I am a student researching my master’s thesis on the British photography magazine TEN.8, established in Birmingham in 1979. In Whitstable, as we walk between exhibition venues, I chat nervously to Cherry about it, knowing that she has contributed to some of the debates and was close to photographers and theorists whom I am beginning to write about. I wonder if she is nonplussed about being asked to return to that time since she seems a bit more interested in my girlfriend’s glossy new Doc Martens sandals in deep red leather.

I am writing anecdotally about this meeting because it frames the spirit of return that shapes the following conversation. When Cherry and I speak in November 2024, an exhibition has just opened at Tate Britain dedicated to TEN.8 and associated histories of British documentary photography in the 1980s. Twelve years earlier, the work of returning to the politicised cultural practices of that period was taking place at a more grassroots level partly among artists such as Margareta and P. Staff, who were interested in not just revisiting but also reactivating archives of leftist activism and dissent. In 2012, in the wake of the financial crash, and amid a broader context of student uprising, housing activism, and an emerging movement of newly unionised workers such as the group Justice for Domestic Workers, the radical histories of the 1980s seemed to come alive again. Not only were the interconnected struggles and solidarities signalled by the cultural practices associated with the 1980s offering inspiration for the present but they were also instructive in understanding the political transformations that were to characterise the intervening decades, which were undergirded by the logic of neoliberalism and the practice of privatisation.

The heterogeneous terrain of political activism and cultural production in the 1980s is one that Cherry and I discuss in the conversation that follows. Speaking over Zoom, Cherry recalls her involvement in the Women’s Peace and the Troops Out of Ireland movements, in HIV/AIDS activism, and in the new queer politics of the 1990s. These activities gesture to important correspondences and fractures in the period under discussion. As we loop between different struggles, between the present and the past, I am reminded of the temporalities enacted by her 2019 poetic sequence Famished, which dwells on the long history of the Irish Famine, examining the subsequent migration crisis and the role of women in it.2 In Famished, the past and the present connect through polyvocal performances. The histories we approach here are a more recent lived terrain for Cherry, but the means of telling them also suggests a multiplicity of discourses, allegiances, and layers of engagement.

2Interview

Laura Guy: “They call us British. / Stamp out our language. / Undermine our culture, / Swallow our pride”.3 These lines are from your poem “Coming Home”, first published in 1995. “Coming Home” attends to the violence of separation and its impact on both personal and cultural memory. In the poem, this separation from your home country, Ireland, is felt through language. Yet it is also the splitting apart from your queer life in London when you visited home.

3Cherry Smyth: “Coming Home” was a way of going home and bringing London with me through writing. It was written in the period before I came out to my family. Every time I went home, I regressed to being eighteen or younger; none of my family had left Ireland; my life in London was erased. I remember writing that poem in fragments over several visits. It gave me a sense of coherence, a sense of belonging in the world of writing. I’m reminded of the line “Coming out gave me a voice and took away my tongue” from my poem “Private Love”.4

4“Coming Home” was a defiance as well. While male writers like James Joyce, Seamus Heaney, and Sean O’Casey were endlessly celebrated, it was rare to say that you wanted to be a woman poet. In some ways my sense of belonging was so strongly in the lesbian community that it sheltered me from the anti-Irish racism in England at the time, but being in London sheltered me from the homophobia in Ireland.

In 1993 or 1994, I remember being at the Lesbian Lives conference in Dublin.5 I read my work and it was extraordinary. People were clapping before I’d even finished the poem. They were so desperate to find something to relate to as Irish lesbians. I did feel a real draw to go back to Ireland and read in public because I felt protected by the lesbian and gay community in London. In Ireland, they didn’t have that sense of protection or even legality at that point.6

5LG: When you left Ireland and arrived in London, did you identify as lesbian?

CS: Not exactly, no. I left Ireland in 1982 for a year, for a postgraduate diploma in Film and TV at Middlesex in London with no intention of staying for forty! I never really wanted to live in England, to be part of the diaspora. But I didn’t want to return to the north of Ireland because of the Troubles, and economically it was hard to be in the south at that time.

When I arrived in London, I got involved with a feminist film course at the BFI where I met some fabulous women. I was very active in Take Back the Night and Greenham Common … Once you got involved in those things, you met all these amazing women who, of course, were lesbians. I came out through film and activism.

I was always writing poetry too and took part in live lesbian poetry readings which were incredibly erotic, and challenging, and fun. Getting spoken word poetry published was really difficult then. It took a long time to get my first collection out.

LG: Were there spaces in which lesbianism and Irishness came together for you, once you were in London?

CS: A lesbian ran the Irish Women’s Centre. When they said “a woman’s writing class” at the centre, it was nine-tenths lesbian. Lesbianism was very present but activities weren’t all organised around that. The centre helped women to stay here who’d come over from Ireland for an abortion.

In London, I belonged to a group of Irish women writers. We had a reading and writing group called Fine Lines. We met regularly, about six of us. We were from the north and the south, and both first and second generation. We got invited to places to read and discuss being Irish. That was mostly Greater London Council (GLC) funded at that time. There was a need for that space for the Irish community and Irish immigrants.

I was very involved in conferences about Ireland, which were an important way of keeping in touch and finding a place for my own instinct for nationalism. Later people assumed I was Catholic because of my politics. I was brought up in quite an atheist way but in a Protestant tradition. The more I read about Protestant rebels, I thought I have to claim it in order to dismantle it. I would always tell people that I was a self-proclaimed post-prod nationalist!

Becoming a lesbian gave me a community and it also gave me a way to be a Protestant from the north and be accepted in a wider Republican setting. That had been much harder when I was in Dublin, though I did go and march in support of the hunger strikes when I lived there. Coming to London and being around the Troops Out movement, and incredibly articulate Irish and English people involved in the anti-apartheid struggle as well, were key to my politicisation. And then the peace movement, of course.

LG: Were there interactions between the feminist peace movement and anti-imperial resistance in Ireland at that time?

CS: Anti-militarisation was a connection I made in my own politics but I don’t think connections were being made as much as I would’ve expected them to be. I remember it being notable when I did meet another lesbian who was involved in Troops Out, an English woman.

LG: It’s one of the contemporaneous criticisms of Greenham, that the protest had a narrow focus and didn’t make links to broader anti-colonial or anti-imperialist struggles.

CS: That’s true. It didn’t. I think that was its strength and its weakness because so many people hadn’t participated in political action and non-violent direct action before. One thing that always stays in my mind was Embrace the Base—30,000 women came in buses from all over the country. A more radical and broader agenda may have lost that impetus, though, of course, some of them didn’t go back because they realised there was so much going on around radical feminism, and patriarchy, and class, and to some extent race. There were a lot of other things being processed and challenged.

At Greenham, it was just that single focus of get the cruise missiles off the land. It was very immediate and direct. Whereas get the troops out of Ireland goes back 800 years. I didn’t blame people for not wanting to get into it or wanting to make those connections, though it left me confused, having grown up with it.

What disappointed me more actually was living in Dublin and people not giving a shit about what was happening in the north. That was more shocking, the lack of empathy or understanding amongst a lot of people that I met, in the south and then in London. In Famished I detail the anti-Irish racism that I encountered when I arrived in England.

LG: Did that surprise you when you arrived in London?

CS: Probably not. I knew how the English media trade. It surprised me more when I went to America and people were so welcoming and saw us as scholars, saints, and righteous. Whereas, when I came to London, we were seen as terrorists, alcoholics, and stupid. It was shocking dealing with it. But it wasn’t shocking that it happened because I did have some understanding of imperialism at that point.

LG: You said you came to London to study film and television. What was the draw for you?

CS: When I came to London, my idea was to go into TV and make documentaries. But I found the TV world execrable and I drifted into more experimental and independent film, going to see it and then helping people, like Jacqui Duckworth, make it, and then writing about it. I started writing my own scripts and trying to develop them. I was also working at Greater London Arts Association, funding people like Derek Jarman and Terence Davies to make short films.

Film and TV were very important to my direction in England and in London specifically. Curating the festival brought together a love of curating, of putting on live events, of presenting things in public. I just really enjoyed all that and the way it helps you develop politically and aesthetically by watching hundreds of films from around the world. It was an extraordinary experience.

LG: When you started to work with video in the 1980s, did it feel like a politicised medium?

CS: Completely. While at Lambeth Video, I made a short film about homelessness and worked with local people and young black women. We created a rap about being homeless, and made a video about women in sport, in which we filmed older Asian women doing aerobics. It was very much connected to empowerment.

It wasn’t formally interesting, though it was striving to be. In 1983 another video co-op, the Albany in Deptford, supported the production of Framed Youth: Revenge of the Teenage Perverts. I remember being really excited by that because it did break the mould in terms of its filming conventions. Then there was Sankofa Film and Video Collective and Black Audio Film Collective, which were really influential for a lot of us at the time.

I would go to the London Film-Makers Co-op as well, but that seemed completely straight, very white and male. It was a radical space in terms of aesthetics though. That’s where I first saw Carolee Schneemann’s work. Then I was introduced to women film-makers like Maya Deren and Alice Guy through Circles and then Cinema of Women.

LG: Were you beginning to make connections between lesbian and gay issues and film and video?

CS: The lesbian and gay community was another contingent that really needed representation and visibility. Video was a great tool for activism. It was very much part of our whole repertoire of campaigning. It was seen as an amazing way to reach people and to collect conversations. To paraphrase the poet the Andra Simons, we were existing ourselves into existence.8

8LG: One of the things that I wanted to talk about was your cultural criticism. When did you start writing in relation to culture and publishing in magazines?

CS: It was around the time I started working at Greater London Arts in the late 1980s. I wrote reviews for the BFI magazine and for a couple of other independent film magazines. Then there was a feminist magazine called Everywoman that I wrote for, for a while. This was before I had a column with Paul Burston in City Limits. I might have written for Spare Rib … most of them didn’t pay or paid very little.

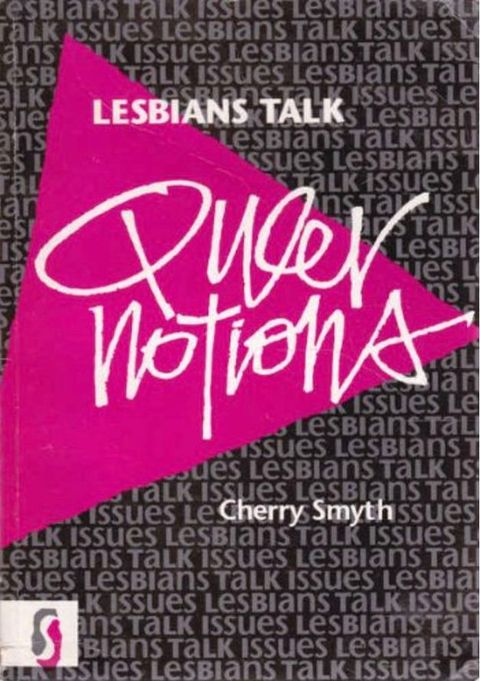

With a friend and colleague at Greater London Arts, I set up a series of talks, “Making it Public”, at the Rio Cinema. We organised each event, screening films around different themes such as “butch”, “femme”, “race”, and “monogamy and non-monogamy”. It was mobbed by lesbians wanting to talk about relationships. It was a way of bringing cultural criticism and activism together. A lot of the people, like the writer Nina Rapi and the film-maker Ruth Novaczek, who took part in “Making it Public”, then became interviewees for my book Lesbians Talk Queer Notions (fig. 2).9

9

I was also writing a little about art at that point because of artists like Sadie Lee. Ingrid Pollard’s early images were emerging. I started gathering things up. It’s interesting when you say cultural criticism because, in a way, I was very aware of becoming a critic. But I was also aware of all those fascinating things that you learn through conversations. It was such an extraordinarily exciting time, the beginning of queer in London, and who claimed it and what it meant.

You know that Beatles movie A Hard Day’s Night? That’s what it was like in London in 1987–88. It was so on fire with ideas. You’d go to see Judith Butler talking one minute, then a screening of She Must be Seeing Things the next.10 There were so many venues to go to from clubs and bars like The Bell or Rackets, Club Kali or Paradise, to places like the ICA. Then there was the Lesbian and Gay Centre, where events brought together sex and performance—live art. Those moments where activism and performance came together really interested me.

10LG: Do you remember when you first heard the term “queer” used in a way that felt like it encapsulated this possibility?

CS: I don’t remember when I first heard it. It was probably through American cultural criticism. Probably through film studies, like the journal OUT/LOOK: National Lesbian and Gay Quarterly. There were academic journals for film that were using it long before we were using it here. If you look at the references in Queer Notions, that will tell you that it was nearly an all-American influence.

I remember there was a letter to City Limits when I was working there. A woman wrote, “Oh, I used to really like Cherry Smyth’s work, but now she’s gone all queer” or something like that. It was disapproving. There were a lot of very heated conversations with older lesbians not wanting to, not seeing, how you could possibly reclaim it. You can see similar debates around the use of racial slurs among black artists in relation to the work of Kara Walker, for instance.

My motivation with Queer Notions was to ask: “What is queer? What can lesbians get from it? Is it going to be just taken over by white gay men? Is that all it is?” I was interested in really looking at the progressive potential of it and believing in it, hoping it could catch on and stay burning.

LG: This would have been during the onset of the HIV/AIDS crisis?

CS: My next-door neighbour was dying of AIDS. Derek Jarman, Stuart Marshall, and John Maybury were making films about it. Some films and performances were emerging from America. I went to protests, organised by ACT UP in New York and then OutRage! over here. We met in the basement of the Lesbian and Gay Centre. It existed in rageful opposition to something like Stonewall, which nobody there supported because it was so self-elected. This was much more non-hierarchical and anarchic.

It was a difficult time but I loved it as well, because for me it embodied the radical potential of lesbians and gay men working together towards something. Looking back, that was probably a little bit idealistic because there seemed to be lots of lesbian-specific issues on which gay men didn’t reciprocate with their support.

Derek Jarman and Jimmy Somerville were around. Then there were Simon Watney, Elizabeth Wilson, these queer elders who were so articulate and amazing. It was the whole gamut—a very rich education. There was an action in which we all lay down in Charing Cross Road and stopped the traffic for a couple of hours. I remember it being incredibly exhilarating and life affirming. When people around us were getting ill and dying, it felt like you just had to do something. It was very immediate.

The other thing that I loved about groups like ACT UP was the graphic quality of it, the graphic design, where again—if you look at Dyke Action Machine and fierce pussy—a lot of the activists had day jobs as graphic artists. And that confrontational wit I loved. That was really important to the aesthetics of those movements and their power. That was really inspiring. I remember seeing this stencil on the pavement when I was walking around New York: “My lover was queer bashed here”. It was naming it, marking out a territory.

I suppose you’re getting a political language while also building an identity, and then you’re learning a visual language which did start to leak into the mainstream. It provided a direct and punchy riposte to the dreadfully ominous and inexplicit government “information” films screened at that time. We were more informed than the government, than health professionals, via North American AIDS activists. It was empowering. I was reminded of a lot of this during the COVID pandemic, when it was hard to access reliable and up-to-date information.

LG: The recent exhibition Women in Revolt! Art and Activism in the UK 1970–1990, curated by Linsey Young, dedicated a room to lesbian practice. There were various artists, photographers, and film-makers represented there whom you worked alongside, such as Del LaGrace Volcano, Ingrid Pollard, Pratibha Parmar. That room framed the work in relation to HIV/AIDS and to Section 28, but my perception is that a lot of that work was also coming out against reactionary positions within feminism.

CS: Yes, it was coming out against the positive imagery and cosy sex, feminist perspectives in which there wasn’t meant to be any role player objectification or fantasies involving power play. I remember really struggling with that at a feminist film conference where people were, like, “no more male gaze”, “no more objectification”. I think I even said: How can you have desire without objectification? Can you explain that? Splits did happen, with women claiming one camp or the other. There were questions around S&M, sex work, Wages for Housework, which were divisive at the time. It was perceived as a betrayal of feminism and a reification of the patriarchy to explore consensual S&M and to support women sex workers. Many women were trying to broaden how lesbian sex was represented and talked about. Some women were violently judged and that was incredibly difficult and painful. I remember going into the Bell one night. I thought it was a mixed lesbian and gay night. I had red lipstick on. Then I got in there and it was women-only. I remember swiping my lipstick off with the back of my hand because I was so scared of being judged as not being a feminist.

LG: Do you see parallels between some of those splits in feminism in that period and the splits happening now?

CS: Yes, I mean, there were definitely questions around sex work that were divisive at the time and disagreements about demanding wages for housework. But I don’t remember people being so violently opposed to trans people. Zach I. Nataf wrote the book Lesbians Talk Transgender around that time.11 Some women saw queer as pro-porn and therefore damaging to women who had been abused. It was very polarised and very, very aggressive. Some of these positions were self-limiting and self-deceptive. That’s what I don’t like about this resurgence of trans exclusiveness. Some of that moralising judgement seems to have resurfaced in trans-exclusionary radical feminism. It’s incredibly self-denying to say you’ve never thought of yourself as having any gender fluidity, never having a cock, never imagining yourself as a man, wondering how your life would’ve been different. It’s deeply divisive and disrespectful of people’s deep struggles to be who they are. It has a similar valence to those debates in the '80s.

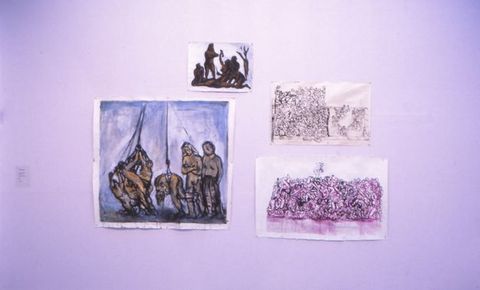

11LG: I was looking at the essay that you wrote for the catalogue to the exhibition Bad Girls (figs. 3 and 4).12 You write about a multiplicity of feminisms in the 1990s that resist the essentialising and didactic early tendencies of earlier feminist work. Was it queer that was offering up this sense of multiplicity for feminism?

12

CS: Queer gave anyone who was questioning heteronormativity a place to be, and it was less tied to your sexual practice than to your progressive politics. I thought that was really powerful. It gave people a way to rebel against the radical feminist mother.

The radical edge of queer has now been taken up by trans. It’s often got that energy of deviance and iconoclasm that queer had. We wouldn’t have heteronormativity if we didn’t have gender binaries. I’ve met some extraordinary non-binary and trans artists, writers, and students, and that’s been incredibly exhilarating.

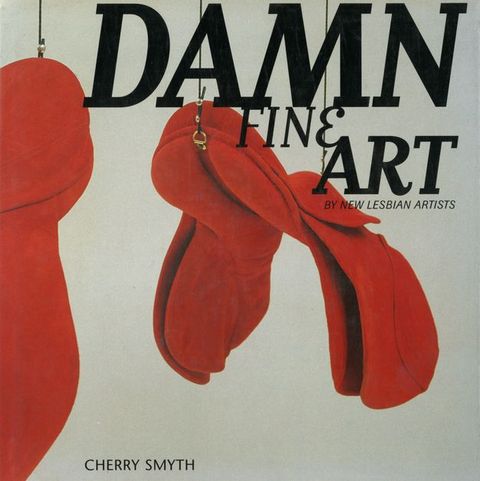

CS: It seemed incredibly important to chart the vitality and urgency of this emergent queer art movement. Queer images have always played a significant role in supporting people to recognise who they are, or could be, in coming out and creating community. I wanted to write a book that celebrated lesbian art within a feminist frame as well as within art-historical traditions which, although they often excluded women, were also key reference points and a bulwark to react against. Previously most lesbian art books were positioned in parallel to the mainstream, not arguing for a place within it.

LG: What understanding or approach to fine art was Damn Fine Art getting at? Where was the intervention situated?

CS: It feels very clear to me—if you look at the tension between community and commerce in the '80s—artists weren’t looking for galleries. They would’ve been extremely surprised if a gallery approached them and would’ve seen representation as a capitalist sell-out. Most lesbians in the art world have often been sheltered or carried by white gay men. I think patriarchy is still the defining category for success, isn’t it? I thought it would’ve changed a lot by now. I can’t believe that I’m reading my intro to Damn Fine Art and thinking, wow, that’s almost more radical than things now.

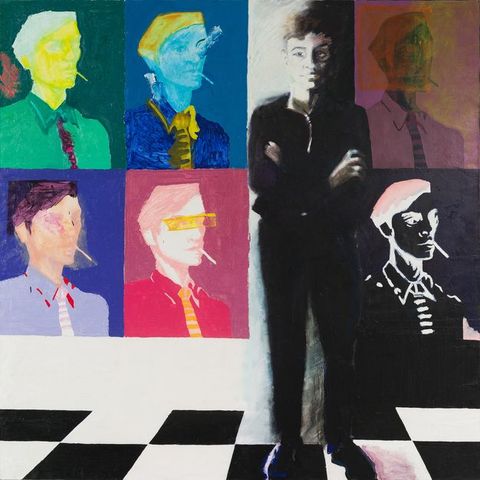

I was talking to the artist Veronica Slater recently about her painting Soul Identified as Flesh, which she made in 1987–88 and was shown in Women in Revolt! (fig. 6). She told me that she was very much making her own icon, in the style of Andy Warhol and his feminine icons. She wanted to make an androgynous icon. The work was about claiming lineage. Its context was informed by Section 28 and the beginning of AIDS, as well as by art history.

In 2023 she made a new series called Soul ID that revisits some of those earlier images (fig. 7). She digitised them, created erasures, and made them more about gender fluidity. She’s worked with the figure for a long time but her recent paintings are more abstract. I thought it was interesting how the two ends of her practice have developed. She’s moved from something incredibly figurative and very defined by the politics around it to something more interrogative of gender and form.

I think it was Nayland Blake who said that if you grow up as queer you are already looking for codes within codes. You’re already attuned to those tropes that could be seen as postmodern, putting together codes that culture has not given you but that you’ve taken. I thought that was an interesting progression in Slater’s work, work that wouldn’t have been shown at the Tate in 1987, that’s for sure. The Tate finally collected Soul Identified as Flesh, which is a key work of lesbian portraiture.

LG: It’s interesting hearing about Slater returning to her earlier work. I wanted to talk about the present reinterest in this recent history. How do you feel about it?

CS: In 2023 I was part of an event hosted at Bishopsgate Library, when Nazmia Jamal digitised the Lesbians Talk series, published by Scarlet Press in the '90s.14 It was Pratibha Parmar, Joelle Taylor, and me. It was hilarious because when one of us couldn’t remember something, the other would come in as this second brain. It was very, very funny. It was quite a mixed audience in terms of age. There would’ve been more space for these kinds of discussions happening at the ICA or the Drill Hall. Back in the 1980s and '90s, there were many more of these intergenerational spaces than there are now.

14I was quite resistant to returning to that moment. I haven’t followed queer representation in the same avid way. My interests have got so much broader, although a lot of the artists that I’m interested in happen to be queer. I had to stop being the poster dyke for things. At that time, I would only be asked to review lesbians and then women artists. But now, when I go back to look at Queer Notions I’m, like, “Oh, wow, she knew a lot this girl! Was I that?!”

LG: Perhaps it’s appropriate to return to your poetry here. I’d hazard that queerness does continue to appear in your work but is located in formal experimentation more so than questions of visibility and representation. Is that also true of the queer artists you continue to be drawn to and to write about?

CS: When I said I’m doing a poetry collection about the Irish Famine, a friend of mine said, “Oh, you’re queering it!” I don’t know if I can do that. How can I imagine a character from that era when being queer was policed, punished, and so often invisibilised? There were also so many other layers of really painful identities on top of it. But perhaps, as you suggest, the polyvocal style I used and the charting of anti-Irish racism owe something to a queer sensibility and a cut-and-paste aesthetic.

There’s a piece by Kian Benson Bailes called Culchie Boy, I Love You (2023). Do you know what a culchie is? It’s someone from the country. We would say, “Oh, he’s just a big culchie”, meaning he’s a rural hick. It can be derogatory but not always. It comes from the Irish word for woods, coilte. He’s come out of the woods. That’s really beautiful. Bailes takes ancient goddess myths and transgenders them using an insect-like body, adorned by his mother’s headscarf, which he places in Catholic churches. His performative transsexuality connects to decolonisation as well as to ancestors, which are ideas and approaches that fuel a lot of contemporary work.

Eimear Walshe represented Ireland at the Venice Biennale in 2024. They’re a non-binary artist who made a wonderful piece called The Land Question: Where the Fuck Am I Supposed to Have Sex? (2020), in which they’re wandering around trying to find somewhere for sex (fig. 8). The video lecture investigates queer sexuality and property in the state and how they are connected. How can you have queer sex if you can’t afford to rent or buy your own privacy? In the 1980s artists such as Bailes and Walshe would probably have had to leave Ireland to make that work. Now they’re staying to make it. That is a significant difference. Just when you think nothing’s changed, it really has.

About the authors

-

Cherry Smyth is an Irish writer living in London. Her fifth poetry collection, One Mountain: Sold (Arlen House Press, 2025), examines the wreckage of extractivism and presents other new poems that have evolved out of concerns about how we relate to each other, the environment, and ethics. Famished (Pindrop Press, 2019), a book-length poem, explores the Irish Famine and how imperialism helped cause the largest refugee crisis of the nineteenth century. If the River Is Hidden (Epoque Press, 2022), co-written with Craig Jordan-Baker, is a prose–poetry collaboration based on a river pilgrimage in Northern Ireland. Smyth has also published Queer Notions (Scarlet Press, 1992) and Damn Fine Art: By New Lesbian Artists (Cassell, 1996). She co-curated Limber: Spatial Painting Practices at the Herbert Read Gallery in 2013 and also writes for Art Monthly. She has written catalogue essays for Elizabeth Magill, Orla Barry, Brigid McLeer, Mikhail Karikis, and others. Smyth’s website is www.cherrysmyth.com and her Instagram account is @cherrysmythpoet.

-

Laura Guy is a Reader in Gender, Sexuality, and Culture at the Glasgow School of Art. Her writing on the interactions of art and design with feminist and queer politics has been published widely. She is co-editor with Glyn Davis of Queer Print in Europe (Bloomsbury, 2022) and editor of Phyllis Christopher’s artist monograph Dark Room: San Francisco Sex and Politics, 1988–2003 (Book Works, 2022). In 2023–24, she was principal investigator on the Carnegie Trust-funded research project “Remapping the City of Culture through Grassroots LGBTQ+ Cultural Production”. With Fiona Anderson, Flora Dunster, and Theo Gordon, she is co-editor of this special issue of British Art Studies dedicated to queer art in Britain since the 1980s.

Footnotes

-

1

The screening was part of Strike / 84, a year-long artist residency undertaken by Margareta Kern in the Department of Applied Social Science at Durham University. Strike / 84 was concerned with the miners’ strike “as a historical, cultural and class rupture, and the rise of neoliberal ideology accelerated by the 80s Thatcherism (and later New Labour) whose consequences are felt today” (Margareta Kern, “Strike / 84”, https://www.margaretakern.com/works#/strike/1984/). ↩︎

-

2

Cherry Smyth, Famished (Glasgow: Pindrop Press, 2019). ↩︎

-

3

Cherry Smyth, “Coming Home”, in When the Lights Go Up (Belfast: Lagan Press, 2001), 20. ↩︎

-

4

Cherry Smyth, “Private Love”, in Writing Women 8, no. 1 (1990): 29. ↩︎

-

5

The first Lesbian Lives conference, organised by Ger Moane, Ailbhe Smyth, and Rosemary Gibney with the Dublin-based group Lesbians Organising Together (LOT), took place in the spring of 1993 at University College Dublin. ↩︎

-

6

The Criminal Law (Sexual Offences) Act decriminalised sex acts between men in Ireland in 1993 for consenting persons aged seventeen years and over. ↩︎

-

7

Lambeth Video were a cooperative established in 1983 and predominantly funded through the Greater London Arts Association. ↩︎

-

8

Andra Simons, Turtlemen (London: Copy Press, 2021). ↩︎

-

9

Cherry Smyth, Lesbians Talk Queer Notions (London: Scarlet Press, 1992). ↩︎

-

10

She Must be Seeing Things is Sheila McLaughlin’s 1987 lesbian film classic starring Lois Weaver and Sheila Dabney. B. Ruby Rich remembers that the film was “revelatory” and that “it was denounced by a cadre of anti-porn feminists” when it came out. She writes that it “helped lead the way to the new queer representations” that informed her groundbreaking conceptualisation of “New Queer Cinema”, which was developed in essays for The Village Voice and Sight and Sound in 1992. See B. Ruby Rich, New Queer Cinema: The Director’s Cut, Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2013, p. 8. ↩︎

-

11

Zachary I. Nataf, Lesbians Talk Transgender (London: Scarlet Press, 1995). ↩︎

-

12

Bad Girls was curated by Kate Bush, Emma Dexter, and Nicola White. It opened at the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA), London, on 7 October 1993 and toured to the Centre for Contemporary Arts (CCA), Glasgow, in January 1994. Responding to “perceptible shifts in feminist thinking” and reacting “against the hard-edged didactic work created during the 1980s by artists such as Cindy Sherman, Barbara Kruger, and Jenny Holzer”, Bad Girls featured the artists Helen Chadwick, Dorothy Cross, Nicole Eisenman, Rachel Evans, Nan Goldin, and Sue Williams (Kate Bush, Emma Dexter, and Nicola White, eds., Bad Girls (London: ICA; Glasgow: CCA, 1993), 3). ↩︎

-

13

Cherry Smyth, Damn Fine Art: By New Lesbian Artists (London: Cassell, 1996). ↩︎

-

14

“Lesbians Talk Issues Revisited” was held at Bishopsgate Institute on 30 March 2023. Chaired by Nazmia Jamal and featuring contributions from Pratibha Parmar, Cherry Smyth, and Joelle Taylor, the event was part of a larger project organised by Jamal to digitise the Lesbians Talk Issues series, published by Scarlet Press between 1992 and 1996. More information and a recording of the talk can be found at https://www.bishopsgate.org.uk/collections/lesbians-talk-issues. ↩︎

Bibliography

Bush, Kate, Emma Dexter, and Nicola White, eds. Bad Girls. London: ICA; Glasgow: CCA, 1993.

Nataf, Zachary I. Lesbians Talk Transgender. London: Scarlet Press, 1995.

Rich, B. Ruby. New Queer Cinema: The Director’s Cut. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2013.

Simons, Andra. Turtlemen. London: Copy Press, 2021.

Smyth, Cherry. Damn Fine Art: By New Lesbian Artists. London: Cassell, 1996.

Smyth, Cherry. Famished. Glasgow: Pindrop Press, 2019.

Smyth, Cherry. Lesbians Talk Queer Notions. London: Scarlet Press, 1992.

Smyth, Cherry. “Private Love”. Writing Women 8, no. 1 (1990):29.

Smyth, Cherry. When the Lights Go Up. Belfast: Lagan Press, 2001.

Imprint

| Author | |

|---|---|

| Date | 14 July 2025 |

| Category | Interview |

| Review status | Peer Reviewed (Editorial Group) |

| License | Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) |

| Downloads | PDF format |

| Article DOI | https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-27/csmythlguy |

| Cite as | Guy, Laura, and Cherry Smyth. “Correspondences and Fractures: Lesbians Talk Queer Formations .” In British Art Studies: Queer Art in Britain since the 1980s (Edited by Fiona Anderson, Flora Dunster, Theo Gordon and Laura Guy), by Fiona Anderson, Flora Dunster, Theo Gordon, and Laura Guy. London and New Haven: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art and Yale Center for British Art, 2025. https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-27/csmythlguy. |