Mumtaz Karimjee

“… my photography was about making visible what would otherwise remain invisible …”1

Making Visible is an introduction to the photographic work of Mumtaz Karimjee. Born in Bombay in 1950, and based in London in the 1980s and 1990s, Karimjee was a self-taught photographer who was actively involved in debates about feminist and lesbian representation and the politics of racial struggle.2 Through her engagement with different modes of photographic practice, from the documentary, community project work, and conceptual self-portraits using image and text, to expressive still lifes, Karimjee skilfully illustrated the intersectionality of diasporic, feminist, and queer identities. As an artist, a writer, and a curator, she made significant contributions to the aesthetic and political debates in Britain during what has been described as “the critical decade”.3

1Mumtaz Karimjee, “In Search of an Image”, Trouble and Strife: The Radical Feminist Magazine 20 (Spring 1991): 22–27, 23, https://www.troubleandstrife.org/issues/Issue20_FullScan.pdf.

For Karimjee’s detailed biography and bibliography, see Alice Correia, “Mumtaz Karimjee: In Search of an Image”, 2020, South Asian Diaspora Arts Archive (SADAA), https://sadaa.co.uk/studio/files/Mumtaz-Kiramjee-essay.pdf.

David A. Bailey and Stuart Hall, “Critical Decade: An Introduction”, in “The Critical Decade: Black British Photography in the 80s”, ed. David A. Bailey and Stuart Hall, special issue, Ten.8 2, no. 3 (Spring 1992): 4–7.

During her artistic career Mumtaz Karimjee engaged with the politics of representation and the ways in which photography could be harnessed as a mode of visual protest. This online exhibition is the first retrospective consideration of her creative practice and includes a selection of newly digitised photographic works and materials, including contact sheets, exhibition posters, and texts sourced from her archive. The exhibition is divided into two parts according to Karimjee’s mode of working: first, documentary and reportage and, second, the conceptual, often expressive, image. Each part presents Karimjee’s work chronologically and demonstrates how she experimented with different modes of photographic practice to address her thematic concerns. However, we can also recognise overlaps and slippages between her photographic forms: some documentary work opens on to the desirous in similar ways to her overtly expressive images, while some staged images take the form of recuperative testimony.

Through her involvement in community photography workshops, feminist publishing, and self-organised exhibitions, Karimjee established important creative networks and undertook collaborative, often activist, projects with other Black and South Asian artists and queer cultural producers. This exhibition illustrates how, across her many photographic series, curatorial projects, and publications, she made visible both personal experiences and communities rendered marginal or simply omitted from mainstream British culture. In the context of this special issue of British Art Studies on queer British art since the 1980s, her engagements with lesbian and gay activism are seen in relation to her personal exploration of sexuality, which intersected with her concerns about female agency and the struggle against gendered and racial violence. Her work is a testament to her resistance and resilience when faced with what she described as “the racism, sexism and homophobia of the white dominant society in which I live and the sexism and homophobia of the society into which I was born”.4

4Mumtaz Karimjee, “In Search of an Image”, artist’s statement, undated, Women’s Art Library, Goldsmiths, University of London.

“I describe myself as a photographer particularly challenging what I see as mainstream photojournalism’s tendency to reinforce stereotypes …”5

In 1976 Mumtaz Karimjee enrolled as a mature student on the BA (Hons) Modern Languages (Chinese and German) course at the Polytechnic of Central London. Having previously worked as a secretary, she was keen to make the most of her educational opportunity and decided to study in China—at Beijing University (1978–79) and then at Nanjing University (1980–81)—at a time when the Chinese government was extremely strict about allowing foreigners into the country. While in China, Karimjee photographed and documented local women and their environments, thus initiating her artistic career. These photographs were subsequently included in exhibitions of Black feminist art, where the word “Black” was understood as a political and unifying term denoting anti-racist solidarity between people of colour. Later, Karimjee became an integral member of the Black Women and Photography group, which published the important journal Polareyes (1987). Alongside her community workshops and curatorial projects, Karimjee’s social documentary photographs of women in the United Kingdom positioned her internationally within a global feminist network. She sought to make visible women who were stereotyped, disempowered, or ignored by British print and broadcast media but who were central to her own globally attuned cultural life. Writing in 1991, she explained: “Creating our own imagery which challenges the way others see us is one way to self-empowerment”.6

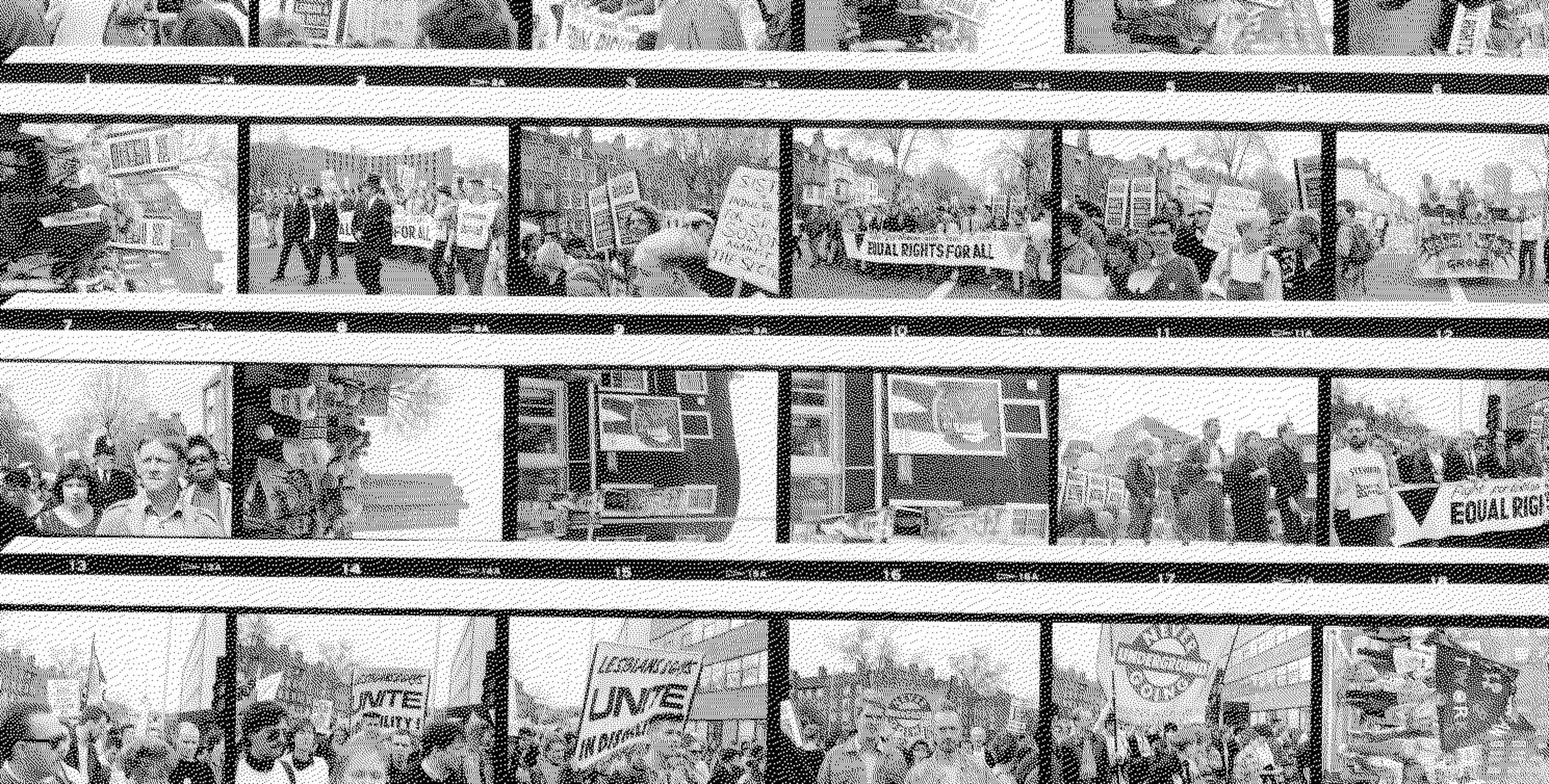

As well as composing photo narratives, and making use of framing texts, Karimjee also worked in responsive reportage while attending and recording protest marches that challenged abuse and injustice. Photographs and archival material in this section highlight her involvement in anti-racist activism and campaigns for women’s rights, and record queer conviviality amid the outrage over the implementation of Section 28 of the Local Government Act 1988 and the prejudicial treatment experienced by those diagnosed with AIDS.

5Karimjee, “In Search of an Image”, Trouble and Strife, 22.

Karimjee, “In Search of an Image”, Trouble and Strife, 27.

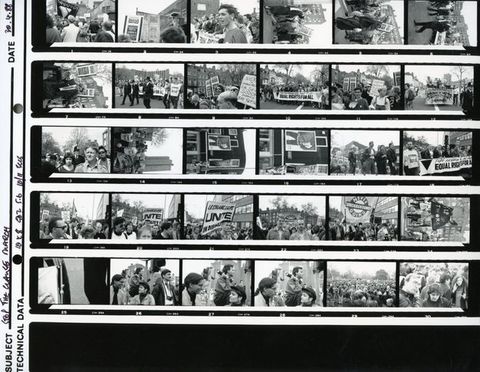

While studying in China between 1978 and 1981, Karimjee started taking photographs of women in everyday settings to explore the realities of their lives and to expose the constructed nature of their representation in Western written and visual media. Women in China 1949–1985 specifically sought to present women as not only active in but central to Chinese society. Karimjee’s photographs include scenes of female labourers carrying shovels walking down a dusty rural road and young mothers playing with children in an urban playground. Other photographs show women depicted on billboards and street murals. When they were exhibited, each image was accompanied by a quotation from a Chinese political leader or an extract from a journalistic commentary sourced from Phyllis Andors’s book The Unfinished Liberation of Chinese Women, 1949–1980, published in 1983.7 The series was first exhibited in Black Women Time Now, curated by Lubaina Himid in 1983 at Battersea Arts Centre, and was then revised and updated for its inclusion in Maud Sulter’s two-week “Check It! Blackwomen’s Creativity Project” festival at the Drill Hall Arts Centre, London, in July 1985.

7Phyllis Andors, The Unfinished Liberation of Chinese Women, 1949–1980 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1983).

Karimjee’s photographic series Reflections of the Black Experience was commissioned by the Greater London Council Race Equality Unit for a group exhibition of the same name, staged at Brixton Art Gallery in March 1986.8 The show was part of a larger, London-wide programme of events addressing the historical and contemporary experiences of Black and South Asian people in the city. Karimjee’s series focuses on the the Bengali community in east London and includes images of young children watching a performance of traditional Indian dance and of policemen walking past pro-National Front graffiti. The series depicts both the joys and the struggles of life to underscore the observation that there is no singular South Asian “experience”. Photographs from this series were reprinted and included in the exhibition The 80s: Photographing Britain at Tate Britain in 2024–25. This show partially restaged the exhibition Reflections of the Black Experience and included works by each of the ten participating artists.

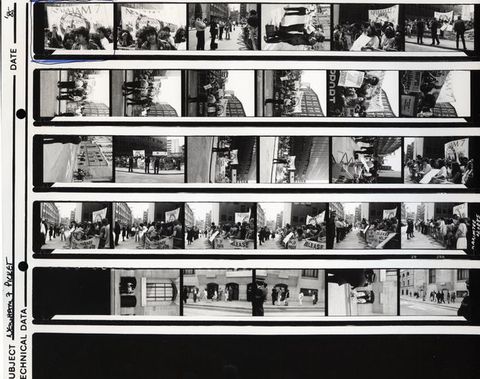

Included in the exhibition Reflections of the Black Experience, the photograph Newham 7 Picket at the Old Bailey, London records the mass picket that congregated outside the Old Bailey in support of the “Newham 7” in 1985. On 7 April 1984, seven young men had been arrested during a confrontation with a gang of white racists who had spent the day attacking the local South Asian community in Newham, east London. The trial of the Newham 7 started on Monday, 13 May 1985, with each defendant facing charges of affray.9 Karimjee photographed the picket organised by grassroots campaigners, capturing the many protesters chanting and holding banners, and members of the public entering court wearing supportive placards. Although the defence case rested on the right to self-defence, four of the seven were eventually convicted.

Throughout the 1980s and into the 1990s, Mumtaz Karimjee photographed protesters campaigning against violence towards women at numerous protest marches and Reclaim the Night events. Her photographs show that these events were attended by women of different ages and ethnicities who were united in a common goal and who were agitating for women’s rights both in the United Kingdom and internationally. These photographs capture different moments of anger, rage, and frustration but also the quiet dignity with which women expressed their demands.

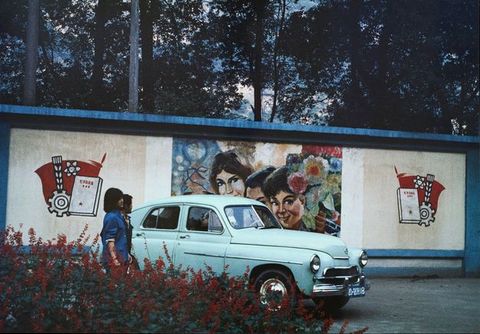

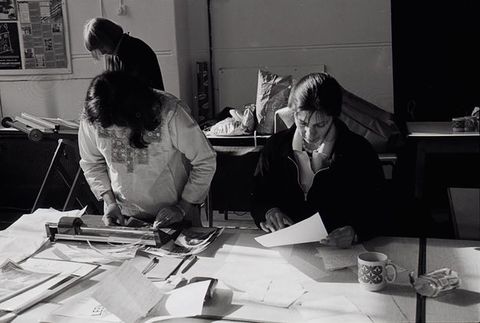

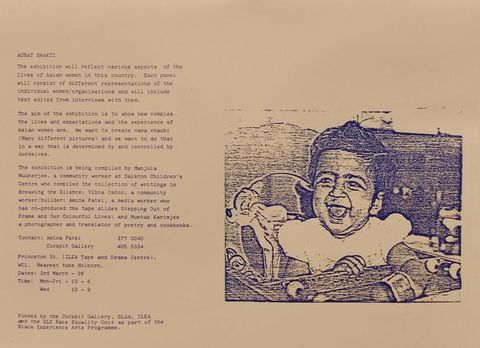

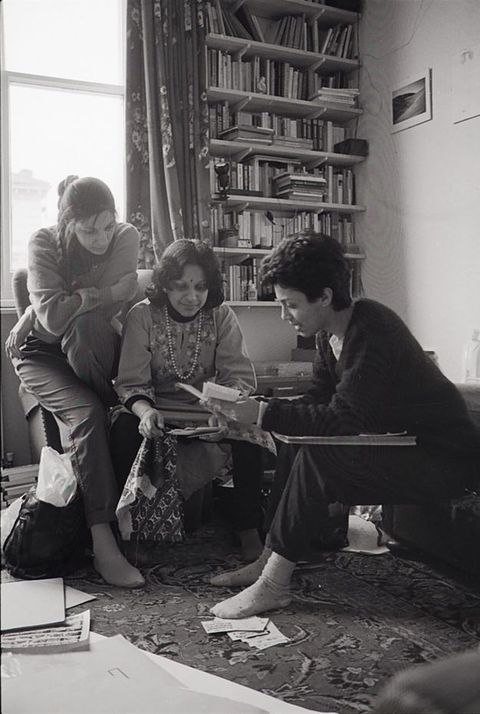

In 1986, with Amina Patel, Manjula Mukherjee, and Vibha Osbon, Karimjee organised the exhibition Aurat Shakti at the Cockpit Gallery, London; it later toured to other venues.10 Aurat Shakti (translated from Hindi as “Women’s Power”) was a collaborative community exhibition in which the four coordinators worked with South Asian women, including the activist Jayaben Desai, the artist Samena Rana, and women’s groups such as Asian Girls Group Islington and Asian Women’s Resource Centre, Brent, to record the complexities of their lives and experiences in Britain. The resulting exhibition was composed of twenty laminated panels that included photographic portraits of the participating women, typed transcripts of their statements, and images selected from their respective personal photograph albums.

In 1976 Jo Spence published her groundbreaking essay “The Politics of Photography”, in which she argued that community photography workshops challenged the elitist hierarchies of image-making that controlled and manipulated who is pictured in print and broadcast media and how they are represented.11 Recalling the arguments made by Spence, Karimjee and Patel later explained that they encouraged participants to use their own personal snapshots “in order to contest and highlight the differences between the images taken by the photographer which constructs the subject, and the subject’s personal photographic selections”.12 The exhibition sought to emphasise cumulatively the multiplicity of voices among the British South Asian community and to question the ways in which mainstream photojournalism can frame women in regressive ways.

10See “Aurat Shakti—Muntaz Karimjee, Vibha Osbon, Manjula Mukerjee & Amina Patel (3–26 Mar 1986)”, Cockpit Gallery Exhibitions & Cultural Studies Projects 1973–89, Cockpit Archives, https://cockpitarchives.co.uk/aurat-shakti-muntaz-karimjee-vibha-osbon-manjula-mukerjee-amina-patel-1986/.

See Jo Spence, “The Politics of Photography”, Camerawork 1 (February 1976), https://fourcornersarchive.org/archive/view/0000001.

Mumtaz Karimjee and Amina Patel, “Aurat Shakti”, in “The Critical Decade”, 146–47, 146.

Alert to the visual biases informing the stereotyped representation of women from the global majority, the series My Mothers My Sisters (1987–88) presents images of women in India. Drawing on a matrilineal history of anti-colonial struggle, Karimjee’s photographs depict women from different generations as active agents in their own lives, whether as homemakers, as workers, or as activists challenging social injustices. Of this series, she wrote: “My Mothers My Sisters represents the beginning of my photographic journey home. … To find my own home I have needed to reclaim the stories of My Mothers and My Sisters, stories which have been made invisible by colonial and patriarchal history”.13 The series was first exhibited in Karimjee’s solo exhibition in 1987, which was part of the multivenue Spectrum Women’s Photography Festival, which she co-organised with Elaine Kramer. My Mothers My Sisters was subsequently included in the exhibition Fabled Territories: New Asian Photography in Britain, curated by Sunil Gupta at Leeds Art Gallery (and touring) in 1989.

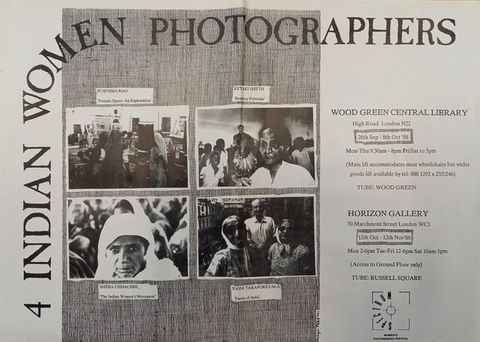

In 1988 Karimjee curated the exhibition 4 Indian Women Photographers as part of the Spectrum Women’s Photography Festival. The first exhibition dedicated to Indian women photographers to be staged in the United Kingdom, it presented work by Sheba Chhachhi, Purmina Rao, Sooni Taraporevala, and Ketaki Sheth. Karimjee had met the participating photographers in 1987 while on a research trip to India, funded by the Women’s Solidarity Fund. Each artist presented works that engage with the experiences of women from different castes and regions of India, demonstrating both the distinct specificities of their lives and the commonalities of living in a patriarchal society. With the support of Amina Patel of Cockpit Gallery and of Laxmi Jamdagni, the show was initially staged at Wood Green Central Library, north London, and then moved to Horizon Gallery in central London. For Karimjee, the exhibition represented “a breakthrough in the monopoly of who is ‘allowed’ to show their images of India in Britain”.14

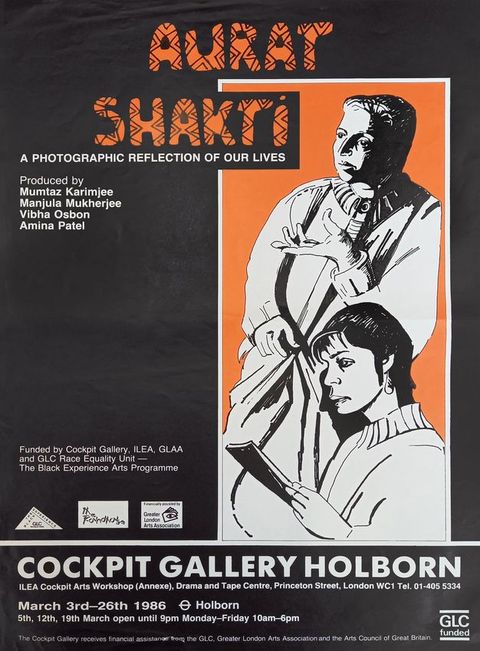

On 30 March 1988 Mumtaz Karimjee documented protesters at the national Stop the Clause rally in London. The mass public rally had been organised to protest against the implementation of Clause 28 of the Local Government Act, which ultimately became law on 24 May 1988. The clause, which stipulated that local authorities could not intentionally “promote the teaching in any maintained school of the acceptability of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship by the publication of such material or otherwise”, was regarded by many as a vicious homophobic attack on gay and lesbian rights. Karimjee’s photographs of the march give access to moments of queer sociality and attest to an “increased sense of lesbian and gay community” that such protests engendered.15

Karimjee’s images were included in the exhibition Against the Clause at Community CopyArt, London, 3–28 May 1988. The show of photographic and photocopy-based art had been conceived as a celebration of “Lesbian, Gay and heterosexual defiance”.16 In his review of the exhibition, Manick Govinda suggested that Karimjee’s images of protesters were important documents that recorded the authoritarianism of “an increasingly oppressive state and [the] defiance against it”.17 The show’s catalogue included an essay by the lesbian film-maker Pratibha Parmar, while Karimjee’s photograph of protesters with printed “Stop the Clause” slogans taped to their jackets, was reproduced on the cover.

15Tessa Boffin and Jean Fraser, “Introduction”, in Stolen Glances: Lesbians Take Photographs, ed. Tessa Boffin and Jean Fraser (London: Pandora, 1991), 9–21, 9.

Manick Govinda, “Against the Clause Exhibition”, Bazaar 5 (Summer 1988): 20–21, 20.

Govinda, “Against the Clause Exhibition”, 20.

In 2023 Rohit K. Dasgupta and Churnjeet Mahn argued that “LGBTQ+ South Asians have a fractured presence in the history of queer and antiracist resistance and community building in the UK”.18 As such, Karimjee’s photograph depicting (from left to right) Keith Khan, Al-An deSouza, Pratibha Parmar, and Sunil Gupta at the national Stop the Clause protest rally on 30 March 1988 is of historical importance. Capturing some of the leading gay and lesbian artists of South Asian heritage, the image positions Karimjee in a wider narrative of queer South Asian creative resistance. Parmar and deSouza both went on to contribute to the publication Ecstatic Antibodies: Resisting the AIDS Mythology, edited by Tessa Boffin and Sunil Gupta. This photograph is also of interest because it appears to be taken on the same day that Gupta photographed deSouza and Khan for his series “Pretended” Family Relationships (1988), itself a protest against Clause 28.19

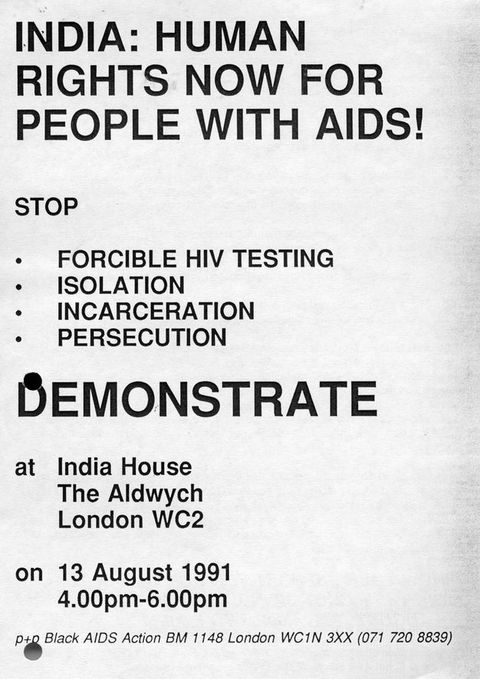

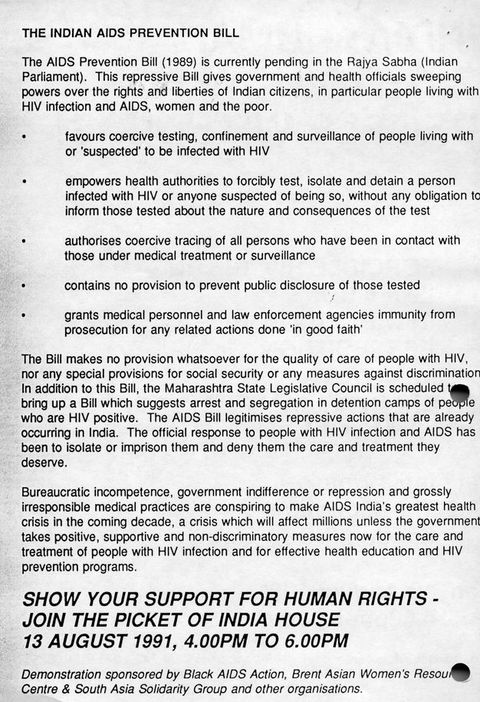

In August 1991, Black AIDS Action, Asian Women’s Resource Centre, Brent, and South Asia Solidarity Group organised a demonstration outside India House in central London to protest against the systematic abuse of people with AIDS in India. Black AIDS Action was an independent, voluntary group that monitored governmental responses to the HIV/AIDS epidemic and its particular impact on the global majority. In 1991 there was concern about the AIDS Prevention Bill of 1989, which was passing through the Indian Parliament. The bill made no provision for the care of those with HIV/AIDS but, instead, proposed to entrench existing practices of surveillance and the segregation, isolation, and criminalisation of those living with the virus. Karimjee’s photographs of the demonstration, together with her archival materials produced by Black AIDS Action, speak to the important work undertaken by grassroots activists in the fight against discrimination and harassment of those with HIV/AIDS in the early 1990s.

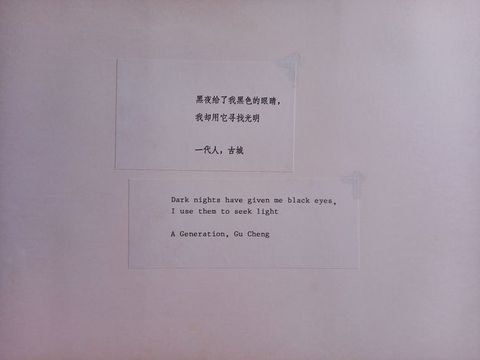

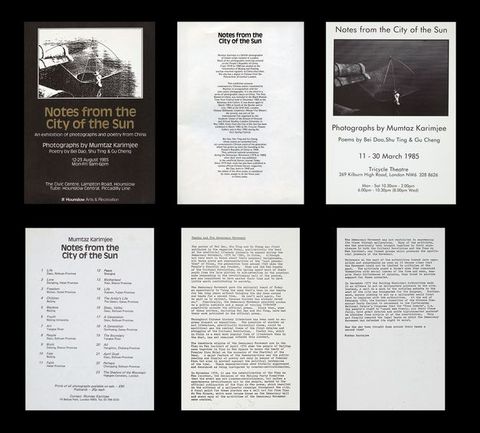

Alongside her documentary work, Karimjee also created non-didactic experimental landscape images and developed a conceptual photographic practice that included studio-based self-portraiture, animation, and still life imagery. Central to her approach to this type of image-making was an acute awareness of the strictures placed on freedom of expression through self-censorship, familial or social constraint, or governmental restriction. During her studies in China, she was exposed to the pro-democracy “Misty” poets, and the way in which they used metaphor and oblique imagery to criticise and contest the Chinese state. Responding to these poets, Karimjee’s series Notes from the City of the Sun depicts China and its people through an exploration of light, shadow, and atmospheric conditions. These images and her subsequent abstract and conceptual works pose questions about how politicised statements may be rendered beyond didactic and explicit means.

Throughout the 1980s and into the 1990s, Karimjee developed her interest in poetic and non-narrative imagery. Using black-and-white film she photographed urban architecture and the remnants of London’s industrial infrastructure. Colour photographs of flowers rendered abstract through the use of extreme close-up may be understood as both haptic and erotic studies. While some queer and racialised artists debated the need to create “positive” photographic images to counter negative stereotypes, Karimjee asserted her right to simply create. In 1987 she wrote:

20Tired of struggling for my right to create

Tired of struggling with the politics and ethics surrounding my right to photograph

I retreat to create.20

Mumtaz Karimjee, Polareyes: A Journal by and about Black Women Working in Photography 1 (1987), 26–28, 27. Karimjee has noted that the word “ethics” was erroneously printed as “ethnics” in Polareyes (correspondence with the author, June 2024).

Notes from the City of the Sun is a photographic essay comprising images taken by Karimjee during her visits to China between 1983 and 1985. Accompanying the photographs are Chinese poems that the artist translated herself.21 A Generation is an image of tonal shadows in which figures walking along a track may be discerned, with bamboo plants framing the scene. It is unclear whether this is dawn or dusk, and a shroud of mist obscures specificity. Alongside the image is a two-line poem titled “A Generation” by the celebrated poet Gu Cheng (1956–93). Karimjee explains that her use of image and text is meant to provoke her audience “to question how she looks at the images by juxtaposing them with the text in such a way that the text does not provide simple explanations”.22

These archival documents record the context in which Karimjee created Notes from the City of the Sun and the sites where the series was exhibited. Rather than showing in conventional gallery spaces, Karimjee exhibited her work in 1985 at cultural venues across London, including the Tricycle Theatre, Kilburn (March); the Greater London Council’s County Hall on the South Bank (May); and Hounslow Civic Centre (August). Karimjee’s essay “Poetry and the Democracy Movement” provides an introduction to the work of the eminent Chinese scholars Gu Cheng, Shu Ting (b. 1952), and Bei Dao (b. 1949), who were closely associated with the pro-democratic movement and whose poems were understood by the artist, and Chinese audiences, as acts of contestation.23 Her decision to translate and use their poems in this series signals a form of solidarity with peoples facing oppression across the globe.

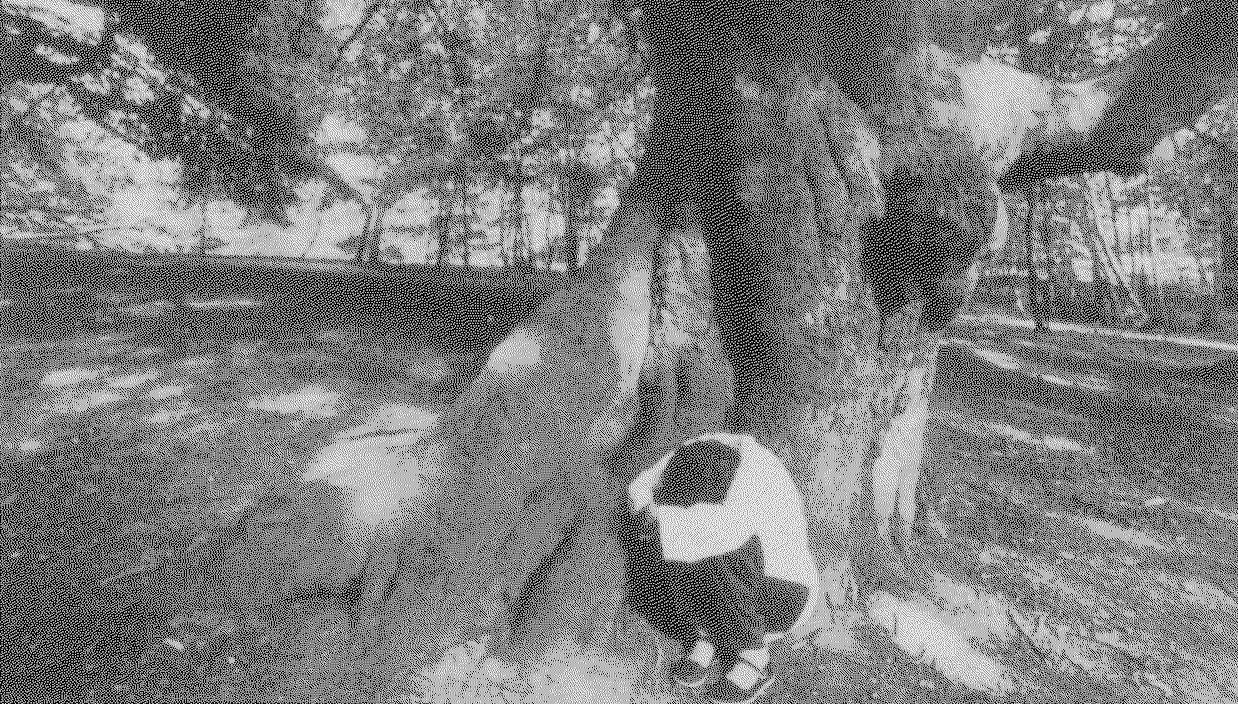

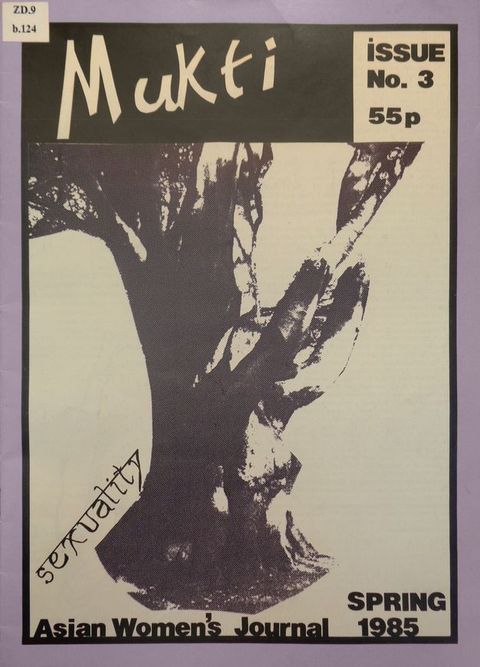

Between 1983 and 1987, Karimjee was part of a collective of South Asian women who created and published the feminist magazine Mukti: Asian Women’s Journal, which addressed the lived experiences of South Asian women in Britain across seven issues.24 Thematic issues tackled topics including work, education, and racism and prejudice. Issue 3, on sexuality, was published in the spring of 1985 and features a photograph by Karimjee on the cover, depicting what she has described as her “favourite” tree on Hampstead Heath, London. The original colour image is a compositional study of dappled light and shadow, as sunlight casts patches of bright light through the tree’s branches and leaves. The location of the tree in an area known for gay cruising raises questions about the public spaces available to gay and lesbian people in the 1980s.

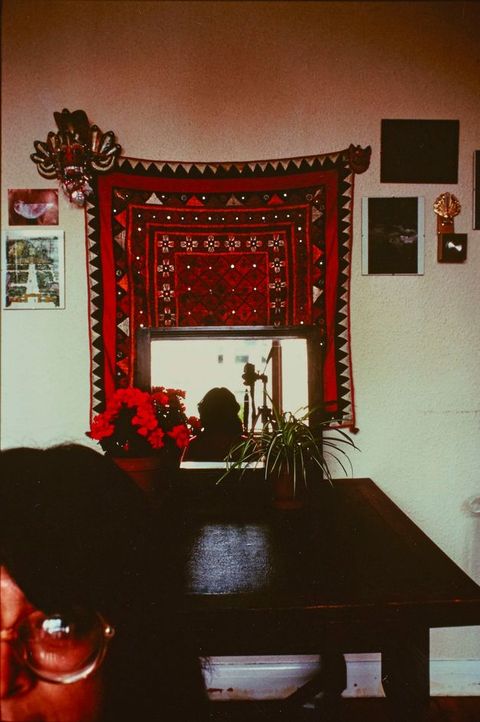

Described by the artist as a self-portrait, Veils and Windows shows a fragment of Karimjee’s face in the lower left-hand corner, while the rest of the image presents the interior of a domestic space, with the camera in front of a window seen reflected in a mirror on the rear wall. The reflective here and there of the composition is destabilising and resists fixity. This unsettled composition, together with Karimjee’s fragmentary portrait, suggests how identity is both revealed and concealed at particular moments and in particular contexts. The photograph was part of the Women in China 1949–1985 series exhibited at the Drill Hall Arts Centre in 1985. It was also reproduced in black-and-white in the third issue of the feminist magazine Mukti, alongside an article about the strictures of arranged marriage. In this context, the photograph gestures to how many queer South Asian women struggle for self-expression in the face of familial heteronormative expectations and demands.

Part of the series Reflections of the Black Experience, Brick Lane: Doors and Shadows presents the urban fabric of London’s East End, which is home to a large Bengali community. In this black-and-white photograph Karimjee shows the exterior of a shabby building in a poetic study of light and shadow. Stippled light falls on an arrangement of abstracted rectangular forms, suggesting that beauty may be found in sites and spaces ordinarily regarded as decaying. Karimjee’s composition focuses on the geometric arrangement of doors and windows and, together with her decision to use black-and-white film, directly recalls the imagery of modernist photography that focused “on the repeated patterns of light and dark found in the experience of everyday life”.25

In this multipart work Karimjee explores her own sexual identity in the context of two distinct societies that are hostile to it. In Search of an Image consists of two parts separated by an image of the artist crouching at the base of a tree. On the left, titled “The Eastern Disease?”, Karimjee performs the role of an “exotic” sexual deviant that conforms to a British colonial stereotype of lesbianism, as revealed in the accompanying quotations. On the right, titled “The Western Disease?”, Karimjee in modern dress reads an article about the discrimination experienced by lesbians in contemporary India. The work cumulatively challenges the notion that homosexuality is the result of contact with “other”, contaminating, cultures. In Search of an Image was first included in Karimjee’s 1987 solo show alongside the series My Mothers My Sisters and was later included in the exhibition Stolen Glances: Lesbians Take Photographs, curated by Tessa Boffin and Jean Fraser in 1991. In 1996 Sunil Gupta reflected, “Karimjee’s work is a brave attempt to reclaim a space for herself … As the first published piece of ‘out’ lesbian work by a Muslim woman in this country it is historic”.26

In March 1990 the Association of Black Photographers (now Autograph ABP), launched its first exhibition titled Autoportraits.27 Mumtaz Karimjee exhibited a multipart work consisting of staged portraiture, still life, landscape imagery, and a prose poem. In 1991 she reflected:

During the year leading up to the opening of the exhibition my life was filled with trauma, beginning with my father’s death which opened up all kinds of old wounds. It made me understand the extent [to which] my life had been dominated by fear, how much of my energy had been spent dealing with the fact that I was always terrified. So, when it came to actually producing the work for the exhibition I felt I couldn’t just present “pretty” pictures of myself and the work I did produce explored fear. Portraits of myself as a small child, cowering in the corner of a bed mirror each other and lead to a central image of myself running away. The context for these images are photographs of my mother’s grave and my father’s flat as I was packing it up after his death and the text:

Fear—Alienates—The small child—Runs—Adult—Dreams—Shatter.28

27See “Autoportraits. 20 Mar–12 Apr 1990. Past Exhibition”, Autograph ABP, https://autograph.org.uk/exhibitions/autoportraits.

Karimjee, “In Search of an Image”, Trouble and Strife, 24.

Labismina: A Survivor of Child Sexual Abuse Returns from the Underworld takes its title from a Brazilian folk tale about Dona Labismina, who was born in the form of a snake, while her twin sister, Maria, was born human. During childhood, Labismina protects Maria from becoming a child bride, but she retreats to the sea at the onset of puberty, reassuring Maria that she will return if help is needed. Made in collaboration with Lindsay River, Labismina is an audiovisual slide tape that includes songs and paintings by Carmen Tunde Williams alongside shadow puppetry, photographic self-portraiture, poetry, and texts. It draws on ancient myth, colonial histories of violence, survivors’ testimony, and contemporaneous scholarship to address the sexual abuse of children, women, and people regarded as “property”. Throughout, a narrator asserts their identity “as a Black survivor …”. Labismina was commissioned by Autograph ABP for inclusion in the exhibition Mis(sed) Representations, which toured to Cave Arts Centre, Birmingham, and Bluecoat Gallery, Liverpool, in 1992.29

In 1993 Mumtaz Karimjee created a series of sensual photographic studies of purple irises and other flowers. While this series may relate to the analytical work of the gay photographer Robert Mapplethorpe, Karimjee’s close-up, tactile flower imagery is arguably better understood in the context of modernist gender-nonconforming painters including Vanessa Bell, Gluck, and Georgia O’Keeffe, who, in the early twentieth century, used flower imagery metaphorically to address themes of sexuality and desire. Karimjee’s playful titles, such as Wild about Iris or Coming Out, Petal? allude to lesbian pleasure and eroticism. As such, they recall Audre Lorde’s 1978 essay “Uses of the Erotic”, in which she defines the erotic as “an assertion of the lifeforce of women; of that creative energy empowered”.30 Two of Karimjee’s flower portraits were included in Lesbian Looks: Postcards from the Edge, published by Scarlet Press in 1993.31

By the mid-1990s, changes to arts funding had led to fewer opportunities for Black and Asian artists to self-organise and exhibit. Karimjee moved to Liverpool and, while she continued to take photographs periodically, refocused her career on homeopathy.

Karimjee’s photographs from the 1980s and 1990s may be regarded, cumulatively, as unambiguous affirmations of female agency. Whether working in a documentary mode or experimenting with conceptual, poetic, or metaphoric imagery, they challenge patriarchal heteronormative assumptions about queer Asian womanhood in Britain and present the pluralities of female experience beyond reductive and essentialising tropes. Karimjee’s contributions as an artist, writer, community facilitator, and curator disrupt the erasure and omission of racialised queer histories from majority-white heteronormative art histories. Documenting the diverse ways in which South Asian queer identities were expressed in the 1980s, her photographs of Section 28 protests and photo essays such as In Search of an Image are part of an underacknowledged moment of resistance in British society. Thankfully, in the 2020s art-historical re-evaluation of the 1980s has led to the inclusion of Karimjee’s work in several important exhibitions and publications.32

Throughout her career, Karimjee addressed the confined, silent rage experienced by abused, discriminated against, and minoritised people. Her work harnessed that rage and used it productively to speak out. In this respect, Karimjee has done what the writer bell hooks describes:

32Moving from silence into speech is for the oppressed, the colonized, the exploited, and those who stand and struggle side by side a gesture of defiance that heals, that makes new life and new growth possible. It is that act of speech, of “talking back”, that is no mere gesture of empty words, that is the expression of our movement from object to subject—the liberated voice.33

See Alice Correia (ed.), What Is Black Art: Writings on African, Asian and Caribbean Art in Britain, 1981–1989 (London: Penguin, 2022); Linsey Young (ed.), Women in Revolt! Art and Activism in the UK 1970–1990 (London: Tate, 2023); Joy Gregory (ed.), Shining Lights: Black Women Photographers in 1980s–90s Britain (London: Autograph, 2024:); Yasufumi Nakamori, Helen Little, and Jasmin Kaur Chohan (eds.), The 80s: Photographing Britain (London: Tate, 2024).

bell hooks, Talking Back: Thinking Feminist, Thinking Black (London: Routledge, 2015), n.p., quoted in Mumtaz Karimjee with Lindsay River, Labismina: A Survivor of Child Sexual Abuse Returns from the Underworld, 1992.

Acknowledgements

This presentation would not have been possible without the support of Mumtaz Karimjee: my particular thanks to her for opening up her archive so generously.

About the author

-

Alice Correia is an independent art historian. Her research examines late twentieth-century British art, with a specific focus on artists of African, Caribbean and South Asian heritage. She has worked at Tate Britain, Government Art Collection and the Universities of Sussex and Salford. She has held fellowships at the Paul Mellon Centre for the Study of British Art and the UAL Decolonising Arts Institute. She is a co-chair of the British Art Network’s Black British Art Research Group and she is the editor of What is Black Art? Writings on African, Asian and Caribbean art in Britain, 1981–1989, Penguin Classics, 2022. With Derek Horton, she curated A Tall Order! Rochdale Art Gallery in the 1980s at Touchstones Rochdale, 2023.

Alice Correia is an independent art historian. Her research examines late twentieth-century British art, with a specific focus on artists of African, Caribbean and South Asian heritage. She has worked at Tate Britain, Government Art Collection and the Universities of Sussex and Salford. She has held fellowships at the Paul Mellon Centre for the Study of British Art and the UAL Decolonising Arts Institute. She is a co-chair of the British Art Network’s Black British Art Research Group and she is the editor of What is Black Art? Writings on African, Asian and Caribbean art in Britain, 1981–1989, Penguin Classics, 2022. With Derek Horton, she curated A Tall Order! Rochdale Art Gallery in the 1980s at Touchstones Rochdale, 2023.

Footnotes

-

1

Mumtaz Karimjee, “In Search of an Image”, Trouble and Strife: The Radical Feminist Magazine 20 (Spring 1991): 22–27, 23, https://www.troubleandstrife.org/issues/Issue20_FullScan.pdf. ↩︎

-

2

For Karimjee’s detailed biography and bibliography, see Alice Correia, “Mumtaz Karimjee: In Search of an Image”, 2020, South Asian Diaspora Arts Archive (SADAA), https://sadaa.co.uk/studio/files/Mumtaz-Kiramjee-essay.pdf. ↩︎

-

3

David A. Bailey and Stuart Hall, “Critical Decade: An Introduction”, in “The Critical Decade: Black British Photography in the 80s”, ed. David A. Bailey and Stuart Hall, special issue, Ten.8 2, no. 3 (Spring 1992): 4–7. ↩︎

-

4

Mumtaz Karimjee, “In Search of an Image”, artist’s statement, undated, Women’s Art Library, Goldsmiths, University of London. ↩︎

-

5

Karimjee, “In Search of an Image”, Trouble and Strife, 22. ↩︎

-

6

Karimjee, “In Search of an Image”, Trouble and Strife, 27. ↩︎

-

7

Phyllis Andors, The Unfinished Liberation of Chinese Women, 1949–1980 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1983). ↩︎

-

8

See “Reflections of the Black Experience—10 Black Photographers”, Brixton Art Gallery Archive 1983–86, https://brixton50.co.uk/black-experience-photographers/. ↩︎

-

9

See Newham Monitoring Project and Campaign Against Racism and Fascism, Newham: The Forging of a Black Community (London: Newham Monitoring Project, 1991). ↩︎

-

10

See “Aurat Shakti—Muntaz Karimjee, Vibha Osbon, Manjula Mukerjee & Amina Patel (3–26 Mar 1986)”, Cockpit Gallery Exhibitions & Cultural Studies Projects 1973–89, Cockpit Archives, https://cockpitarchives.co.uk/aurat-shakti-muntaz-karimjee-vibha-osbon-manjula-mukerjee-amina-patel-1986/. ↩︎

-

11

See Jo Spence, “The Politics of Photography”, Camerawork 1 (February 1976), https://fourcornersarchive.org/archive/view/0000001. ↩︎

-

12

Mumtaz Karimjee and Amina Patel, “Aurat Shakti”, in “The Critical Decade”, 146–47, 146. ↩︎

-

13

Mumtaz Karimjee, “Statement”, in Fabled Territories: New Asian Photography in Britain (Leeds: Leeds City Art Gallery, 1991), 45. ↩︎

-

14

Mumtaz Karimjee, “4 Indian Women Photographers”, draft press release, 1988, Mumtaz Karimjee Archive Collection. ↩︎

-

15

Tessa Boffin and Jean Fraser, “Introduction”, in Stolen Glances: Lesbians Take Photographs, ed. Tessa Boffin and Jean Fraser (London: Pandora, 1991), 9–21, 9. ↩︎

-

16

Manick Govinda, “Against the Clause Exhibition”, Bazaar 5 (Summer 1988): 20–21, 20. ↩︎

-

17

Govinda, “Against the Clause Exhibition”, 20. ↩︎

-

18

Rohit K. Dasgupta and Churnjeet Mahn, “Between Visibility and Elsewhere: South Asian Queer Creative Cultures and Resistance”, South Asian Diaspora 15, no. 1 (2023): 1–16, 1. ↩︎

-

19

See Sunil Gupta, “Pretended” Family Relationships, https://www.sunilgupta.net/pretended-family-relationships.html. See also Greg Salter, “‘Gay’ Image-Making from Britain and India: Sunil Gupta in the Late 1980s”, in this issue of British Art Studies. ↩︎

-

20

Mumtaz Karimjee, Polareyes: A Journal by and about Black Women Working in Photography 1 (1987), 26–28, 27. Karimjee has noted that the word “ethics” was erroneously printed as “ethnics” in Polareyes (correspondence with the author, June 2024). ↩︎

-

21

Mumtaz Karimjee, conversation with the author, 3 June 2016. ↩︎

-

22

Karimjee, “In Search of an Image”, Trouble and Strife, 23. ↩︎

-

23

Mumtaz Karimjee, conversation with the author, 3 June 2016. ↩︎

-

24

See Alice Correia, “Mukti, South Asian Feminist Activism and Visual Culture”, in Counter Print: The Alternative Art Press in Britain After 1970, ed. Victoria Horne (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2025), 195–218. ↩︎

-

25

Mary Warner Marien, Photography: A Cultural History (London: Prentice Hall, 2003), 201. As exemplified in the work of Paul Strand. ↩︎

-

26

Sunil Gupta, “Culture Wars: Race and Queer Art”, in Outlooks: Lesbian and Gay Sexualities and Visual Cultures, ed. Peter Horne and Reina Lewis (London: Routledge, 2002), 170–77, 174. ↩︎

-

27

See “Autoportraits. 20 Mar–12 Apr 1990. Past Exhibition”, Autograph ABP, https://autograph.org.uk/exhibitions/autoportraits. ↩︎

-

28

Karimjee, “In Search of an Image”, Trouble and Strife, 24. ↩︎

-

29

See Bluecoat Library, https://www.thebluecoat.org.uk/library?q=mumtaz+karimjee. ↩︎

-

30

Audre Lorde, “Uses of the Erotic”, in Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches (Trumansburg, NY: Crossing Press, 1983), 53–59, 55. ↩︎

-

31

Rosa Ainley and Belinda Budge, Lesbian Looks: Postcards from the Edge (London: Scarlet Press, 1993). ↩︎

-

32

See Alice Correia (ed.), What Is Black Art: Writings on African, Asian and Caribbean Art in Britain, 1981–1989 (London: Penguin, 2022); Linsey Young (ed.), Women in Revolt! Art and Activism in the UK 1970–1990 (London: Tate, 2023); Joy Gregory (ed.), Shining Lights: Black Women Photographers in 1980s–90s Britain (London: Autograph, 2024:); Yasufumi Nakamori, Helen Little, and Jasmin Kaur Chohan (eds.), The 80s: Photographing Britain (London: Tate, 2024). ↩︎

-

33

bell hooks, Talking Back: Thinking Feminist, Thinking Black (London: Routledge, 2015), n.p., quoted in Mumtaz Karimjee with Lindsay River, Labismina: A Survivor of Child Sexual Abuse Returns from the Underworld, 1992. ↩︎

Imprint

| Author | Alice Correia |

|---|---|

| Date | 14 July 2025 |

| Category | Virtual Exhibition |

| Review status | Peer Reviewed (Double Blind) |

| License | Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) |

| Downloads | PDF format |

| Article DOI | https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-27/acorreia |

| Cite as | Correia, Alice. “Mumtaz Karimjee: Making Visible.” In British Art Studies: Queer Art in Britain since the 1980s (Edited by Fiona Anderson, Flora Dunster, Theo Gordon and Laura Guy), by Fiona Anderson, Flora Dunster, Theo Gordon, and Laura Guy. London and New Haven: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art and Yale Center for British Art, 2025. https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-27/acorreia. |