Introduction

Introduction: Queer Art in Britain since the 1980s

Fiona Anderson Flora Dunster Theo Gordon Laura Guy

Re-materialising Histories of Queer Art

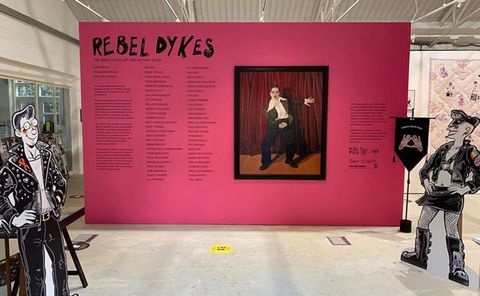

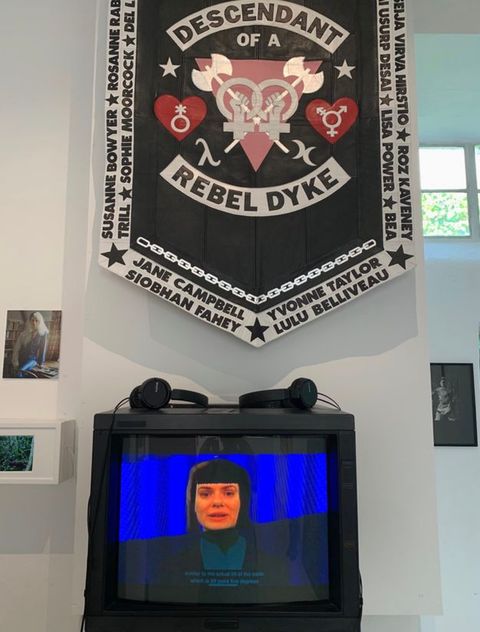

In 2017 a group of women referring to themselves as the “Rebel Dykes” launched a crowdfunding campaign to make a documentary about their history as “a bunch of kick ass post-punk women who lived the life in London in the 1980s”. These women “created their own world, made their own rules, and refused to be ignored”. Rather than let history “tidy them away”, they were taking matters into their own hands.1 What followed was a long and time-consuming process of assembling the resources necessary to become the authors of their own story. As part of their funding efforts, the Rebel Dykes held walking tours of Brixton, where many of them had lived. They hosted a night at the now defunct DIY Space for London that featured a cabaret performance by Frankie Sinatra (one of the Rebel Dykes), and a photo lecture by Jade Sweeting and Janina Sabaliauskaitė, younger artists whose work had been influenced by the photographs and material culture of lesbian life in the 1980s. Merchandise was made and rewards promised. When the documentary was released in 2021 it was as a direct result of this Herculean effort. Alongside still images and archival footage, the film is peppered with ephemera and charged by personal testimony. Where queer curation and scholarship often fixate on questions of scarcity—a perceived lack of archival materials—the Rebel Dykes project makes a different case. It illustrates the fact that, just as often, evidentiary material exists, having been preserved and cared for within community networks for years but that, to gain traction, it requires material resources and the mapping of a historical context.

1

By creating this context, the film re-materialises the community at its heart, lending a name and identity to what was, in its day, an informal social milieu. The Guardian describes “rebel dykes” as “a new term for an old mood”.2 That “old mood” looked something like women exploring their sexuality, navigating conflicts and solidarities, and manoeuvring through the DIY economies that often sustain artistic practice. An exhibition at Space Station Sixty-Five in south London that coincided with the film’s release, The Rebel Dykes Art & Archive Show, underscored the way in which its titular term had travelled, not only capturing a history but also offering a framework through which to position contemporary practice that shares the rebel dyke sensibility (figs. 1 and 2). The exhibition located artists such as Lola Flash, Del LaGrace Volcano, Tessa Boffin, and Jill Posener alongside a younger generation, creating equivalences with work by the likes of Rene Matić, Sarah-Joy Ford, and Bernice Mulenga. Where the idea of the rebel dyke had initially been posed as an identity forged in the context of the long 1980s, here it was reoriented as an oppositional stance with as much relevance to younger generations as to those who came of age in the time of Thatcher’s Britain.

2

This special issue seeks to intervene in the influx of writing and exhibitions on queer art in Britain over the last decade. Many different histories and different timelines have been constructed through these projects, yet in several the 1980s, a period of queer culture and politics shaped by Section 28, the HIV/AIDS crisis and the consolidation of neoliberalism, constitutes a touchstone that connects the recent past with the political struggles of the present. Over the last ten or so years, landmark survey exhibitions such as Queer British Art 1861–1967 (Tate Britain, 2017), Coming Out: Sexuality, Gender & Identity (Walker Art Gallery, 2017), and more recently Women in Revolt (Tate Britain, National Galleries of Scotland, Whitworth Art Gallery, 2023–25) have marked a new period of visibility for queer artistic production in Britain, even as artists and scholars have critiqued the imperative to be visible and advocated for practices and histories that resist “queer” as an institutional interpellation.3 Alongside these larger exhibitions, a broader queer revival of interest in and reappraisal of historic canons and works of art from this period is taking place. A recent example is Blue Now (2023–24), a live-action revisitation of Derek Jarman’s final film Blue (1993), performed by Neil Bartlett, Jay Bernard, Travis Alabanza, Joelle Taylor, and Russell Tovey with the musician Simon Fisher Turner, who had developed the score for the original film. A performance of Blue Now in Glasgow in November 2024 was part of the public programme for the exhibition Digging in Another Time: Derek Jarman’s Modern Nature at the Hunterian Art Gallery, the latest in a series of Jarman exhibitions, such as Derek Jarman: Brutal Beauty at Serpentine Galleries (2008) and Derek Jarman, PROTEST! at IMMA, Dublin (2019–20) and Manchester Art Gallery (2021–22). In contrast to the DIY effort of the Rebel Dykes, Jarman’s legacy has become increasingly established and prominent in the British cultural sphere, a process of confirmation exemplified by the highly successful crowdfunding campaign in 2020 to secure the public acquisition of Prospect Cottage, his seaside home and garden at Dungeness, Kent. This well-publicised effort raised over £3.8 million in ten weeks, a material distinction that points to the inequalities that structure queer cultural production, both past and present.4 Yet both demonstrate how the ongoing project of assembling a history of queer art in Britain—both before and since the 1980s—has necessitated creating a critical context through which artists and practices can be positioned and understood. It is to this developing critical context that this special issue, and the articles and responses within it, makes its contribution.

3The 1980s in Britain: A Critical Context

An animating impulse for this special issue is frustration with the dominance and deployment of histories of queer practice and models of queer theory and politics developed in scholarship produced in and focusing on the United States.5 Our interest as editors in the potential of art and art history in Britain to challenge such cultural imperialism and reinvigorate queer thought stems not from a parochial or nationalistic desire to centre British art therein. Many of the contributions to this special issue foreground the divided, decentred, and devolved nature of artistic, political, and intellectual debates and practices in “Britain” since the 1980s rather than any national unity. This heterogeneity is what we believe a return to the critical contexts of the 1980s offers. Oppositional artistic, cultural, political, and theoretical practices precipitated and coalesced in Britain in especially distinctive and productive ways in the post-industrial, postcolonial social landscape of this decade, offering useful tools for both wider queer critique and the critique of “queer” as currently practised in the often American-centric academy. In Britain, this period saw the ascendency of Black cultural studies, photo theory, the social history of art, and theories of sexual dissidence. These international debates were inflected in the British context with commitments to radical, expansive Marxist thought at the intersections of feminism, sexuality, and racial difference. Such commitments informed creative challenges to “fine art” traditions through new theories of representation and visual culture; a broad ecology of activist groupings, community spaces, and local authority galleries; and diverse venues of publication and debate, such as the journals Screen, TEN.8, and Camerawork, and the organs of the “new” art history. Crucially, such divergent cultural trends and commitments were not formed in a vacuum but as part of the climate of protest and reaction against the hostility and harassment directed at queer and Black communities, the ascendance of Thatcherism, and the escalation of the Cold War. Sites such as the Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp in Berkshire (1981–2000), as touched upon in Liz Murray’s specially commissioned zine in this issue, exemplify one particular contextual circumstance that led to the gathering of feminist anti-nuclear protesters, and the resultant production of queer identities, in Britain. Elsewhere in this special issue, the poet Cherry Smyth discusses the emergence of “queer” as a political sign in Britain, both aligned with and distinct from terminology developed at the intersection of AIDS activism and academic approaches in the United States. Read together, the contributions to this special issue scrutinise the specific ways in which queer gained its vitality in Britain from the political and cultural contexts detailed above.

5Such a broad range of activities across art- and image-making, and political action and debate, are significant to the question of whether a “British queer theory” may be said to exist or, perhaps more importantly, what its radical potential may be now.6 To foreground the specificity and political potential of queer art in Britain as it emerged historically, this special issue is grounded in the 1980s. The various contributions focus in and on, and also depart from, that decade as a space of artistic innovation and theoretical capacity, a site of opposition and resistance to the straightened prospects for queer artistic organising and intervention now. In this spirit, the form and focus of the contributions range considerably. This special issue includes extended critical essays that grapple with historic forms of art production and organising since the 1980s, several of which ask how such projects and efforts continue to resonate in the cultural politics of the present. Evelyn Whorrall-Campbell charts the overlaps and divergences between “trans” and “queer” film and video production and criticism in the 1990s; Fiona Anderson examines the local and international dimensions of HIV/AIDS cultural production in the north-east of England; and Naomi Pearce explores bisexual desire and perspectives as texturing imperatives of visibility, and as challenging canonicity, in queer art history. Other features, including One Object, dwell in detail on singular art objects and archival traces, examining queer forms of engagement and archival labour that encircle these materials now. The issue includes a selection of cross-generational interviews with key artists and figures, such as Beth Bramich’s dialogue with the film-maker Noski Deville and the performance artist and vocalist Nicola Singh, who have recently collaborated on a contemporary response to Deville’s film Loss of Heat (1994), commissioned by the feminist film distributor Cinenova. Intergenerational dialogue and difference is also a feature of the invited responses from curators and critics to the conversation piece “Instituting Queer Art in Britain”.

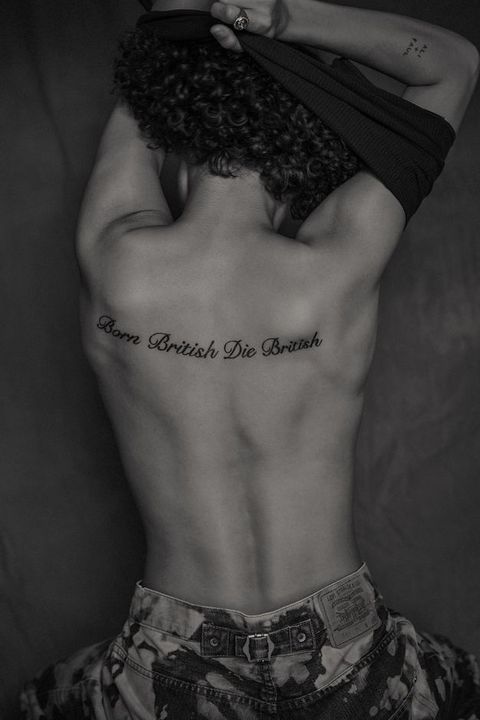

6Another premise of this special issue is that, if queer cultural production in Britain since the 1980s is to be understood, it requires a critical context in which it can be grasped on its own terms, framed by a deep understanding of the material circumstances of living and working in Britain for both artists and art historians, and an awareness of the distinct character and culture of British higher and further education. The contributors to this special issue, like its editors, work across different geographies and in different kinds of academic and cultural institutions. From these dispersed positions, it is important to reflect on the development of queer art as similarly dispersed, not as something attached only to urban centres such as London but happening across England, Scotland, Wales, and Ireland, and in dialogue with countries and protagonists beyond those borders. The practices that characterise queer art produced in Britain since the 1980s often challenge national identifiers and have been forged through anti-racist and decolonial positions. For instance, in Rene Matić’s exhibition Born British, Die British (Vitrine, 2020), the artist appropriates a nationalist slogan identified with racist, right-wing, skinhead subcultures, adopting and inhabiting it from Matić’s position as mixed race, non-binary, and queer. One photograph shows these words tattooed onto their back, raising questions as to what “British” means and to whom it belongs (fig. 3). This photograph was later shown in The Rebel Dykes Art & Archive Show, further nuancing the ways in which “British” changes as it moves through different frames of reference, and highlighting art’s potential to challenge the terms through which we understand it. Similarly, Gregory Salter’s contribution in this special issue examines how the historic regulation of sexuality and race through law and economic coercion in Britain has been coextensive across imperial and postcolonial contexts. In his analysis of Sunil Gupta’s imagery of men and queer relations in Delhi and London in the 1980s, Salter shows how queer art in Britain was from its first formations fundamentally animated by postcolonial and decolonial critique.

At present there is unprecedented precarity in queer cultural production in the United Kingdom, with gallery spaces, archival organisations, and heritage sites facing closure as a consequence of the long-term effects of Conservative austerity policies, in tandem with the present economic downturn and infrastructural crises. London’s Bishopsgate Institute, which holds the country’s largest archive of LGBTQ+ ephemera, and where the contributors to this issue gathered in 2024 for a study day, is illustrative of these conditions (fig. 4). Not long before we met, the institute issued a public email noting that it receives no external funding and that, as a result of “significant financial pressures”, it would pause most public programming for a period of several years. While its special collections remain open to researchers, its library, once open to the public on a daily basis, is now closed indefinitely. As some of the contributors to the conversation piece feature note, calls for greater inclusion and gestures towards queer visibility and diversity in cultural institutions have come at a time of severe underfunding.7 The celebration and visibility of certain artists can serve to drain their energy away from collective and archival projects, a phenomenon that Lubaina Himid warned of in 2005.8

7

Further, the right, left, and centre of British politics have all created what Nat Raha and Mijke van der Drift refer to in their recent book as “hostile environments and atmospheres of violence” for trans, non-binary, and gender nonconforming people.9 Like Section 28 and the feminist “sex wars” that preceded it, the insidious backlash taking place at present limits the space for queer and trans cultural production. These histories also have much to tell us about the specific ways in which censorship happens within institutions, through either fearful pre-emptive self-censorship or outright exclusion. Urgently, this offers potential connection and solidarity between queer, trans, and pro-Palestinian struggles at present. We are completing this editorial in April 2025, immediately following the ruling by the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom on the legal definition of the terms “woman” and “sex” in the Equality Act 2010 in the landmark case For Women Scotland Ltd versus The Scottish Ministers.10 There is much to say on this ruling about how rights-based political discourse limits more capacious and more radical articulations of emancipatory politics, and the collusion of some feminists with the very institutions and structures that produce, reproduce, and entrench gendered, racialised, and class-based violence. The ruling will further embed this violence in the fabric of queer and trans life in Britain.

9Against this backdrop of crises and political turmoil, there has been a burgeoning of curatorial and creative practices that engage with the themes and histories that we have tried to outline here, in particular with the 1980s as what the photography journal TEN.8 named the “critical decade”, accounting for “paradigm shifts in both theory and practice”.11 They include the exhibitions A Tall Order—Rochdale Art Gallery in the 1980s (2023) at Touchstones Rochdale, curated by Alice Correia and Derek Bishton; Hot Moment: Tessa Boffin, Ingrid Pollard and Jill Posener (2020), curated by Radclyffe Hall, at Auto Italia in London; and Ajamu: Archival Sensoria (2021), the second exhibition curated by Languid Hands as part of their curatorial fellowship programme No Real Closure at Cubitt Gallery in London, as well as film projects such as Ed Webb-Ingall’s We Have Rather Been Invaded (2018), about the legacies of Section 28; Rhubaba’s maud (2022), about the Scottish Ghanaian artist Maud Sulter; and Julie Ballands’s Mothers of Invention (2021), which gathers histories of lesbian performance and DIY cultural activity in the north-east of England. As we begin to map these projects—and there are so many more that could have been included—in this special issue, a new formation emerges, a structure of feeling that has characterised a period of cultural production and its return to an earlier moment of art and activism.

11Reimagining Art History Queerly

To think alongside the aesthetic, collective, intergenerational qualities of these projects makes demands of us as readers, viewers, and art historians. As Catherine Grant, whose own research and support were so integral to the development of this project, writes about the work of Sharon Hayes in her book A Time of One’s Own: Histories of Feminism in Contemporary Art, “the transmission of historical material that was intended to build communities is used to think about what kind of queer and feminist communities are needed in the present”.12 The “present moment”, Grant argues, “can only be understood through an intense, embodied engagement with history”.13 Many of the contributions here emerge from such engagement, and indeed take it as the basis of theoretical and political elaboration, as in Theo Gordon’s work on the fragmented records of the exhibition Ecstatic Antibodies: Resisting the AIDS Mythology (1990–93) in the Gupta+Singh Archives in London; Thomas Elliott’s stewardship of the archive of the London Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence as the foundation of his analysis of their and Jean Fraser’s use of queer nun imagery; Alice Correia’s curation of Mumtaz Karimjee’s photo archive; and Flora Dunster’s engagement with the figure of the queer angel in Tessa Boffin’s photographs as a means of querying the ways in which we historicise the recent past. The dialogue between the artists Sarah-Joy Ford and Rachel Field on lesbian tradition exemplifies the powerful and productive enmeshments between bodies, histories, and different forms of artistic and activist practice. Such a dialogue is necessarily undergirded by feminist principles of collectivity and, as Gail Lewis follows through the teachings of Audre Lorde, “the need to take seriously the concept of the ‘generative’ as a potentiality between generations”.14

12Collaboration in the academy, with its demands of proprietary ownership, is different from collectivity in political organising. Importantly, the work we do happens through community engagement as much as through scholarship and academia, as the various contributions to the One Object feature in this issue make clear through their exploration of the archival and emotional labour (within and beyond universities) that underpins much of this work. This archival labour is necessitated by the material and politics of queer practice and supported by the continually expanding spaces for queer scholarship that have opened up in recent years, nationally and internationally, and that make our work possible. These expanding spaces also signal how this special issue came together through our own collaborations as a group of four editors. The issue has its foundations in a number of discursive events and research projects that we have worked on variously, including “Resisting Relations” a symposium at Goldsmiths in June 2019, dedicated to the “sometime resistant, often divergent and frequently precarious ways that lesbian identity appears in histories of feminist art”, and multiple panels at the Association for Art History’s annual conferences, including “Lesbian Constellations: Feminism’s Queer Art Histories” in 2018 and “‘Queer’ ‘British’ ‘Art’” in 2021.15 The pan-European project Cruising the 1970s: Unearthing Pre-HIV/AIDS Queer Sexual Cultures (2016–19), which included the conference “Imagining Queer Europe” in Edinburgh in March 2019, allowed for these ideas to be developed in dialogue with colleagues across Europe, opening up transnational approaches that connect located practices to dispersed communities and global histories.

15With this special issue we wanted to capture a vibrant period in practice and scholarship and to foreground the work of some of the people and projects who have been central to it. Our first emails about this undertaking date back to autumn 2020. We began writing this introduction four years later, at the end of 2024. In the background of any introduction are the material conditions that encircle the production of a publication. Contributors drop out, deadlines are missed, and the commitments of paid work, care work, and urgent life events take precedence. Anyone involved in collaborative endeavour, be it in the academy or elsewhere, understands this, but it feels important to acknowledge here the ad hoc as well as intentional ways in which interventions like the one represented by this special issue come together. Writing this introduction four years after the inception of the project has allowed us to reflect on patterns that structure the sometimes banal or frustrating details of editorial work. Whose work eventually makes it into an art history journal, and whose doesn’t, is a subject that is deeply racialised and classed. Picking up the threads of radical practices that have emerged in the heterogeneous contexts of cultural production then and now, and of which the academy is just one institution among many, means that working on this special issue has sometimes felt like trying to fit a square peg into a round hole. Yet we want to commit this period of queer practice to the record of art history. Doing so has raised questions that have different resonances for each of us. What might art history offer? How does the frame of art history limit or expand what is possible? How might it reshape itself around or through these practices? The contributions to this special issue offer points of departure for working through these questions now and in the future, signalling to the value of collaboration and conversation in the ongoing work of tracing and reimagining histories of queer art in Britain since the 1980s.

Acknowledgements

This special issue has been made possible by many people. We are grateful, first, to the team at British Art Studies who have shepherded it over the course of several years, namely Baillie Card, Tom Powell, Tom Scutt, and Maisoon Rehani. We thank the Paul Mellon Centre for their support, especially Sarah Turner for initial conversations about this project. The breadth and depth of the issue speaks to the remarkable labour of our contributors, and we thank them for the time they have put into crafting each article, response, and feature. This extends to the artists, photographers, and film-makers who have allowed us to illustrate the issue with their work, and to the archives from which we have drawn material. Thank you to the Bishopsgate Institute and Stef Dickers for hosting us in January 2024. A wider network of friends and colleagues have informed our work as individuals and as a group, including James Boaden, Gavin Butt, Glyn Davis, Catherine Grant, Sunil Gupta, Nat Raha, and Charan Singh. We dedicate this issue to the girls, gays, and theys whose queer resistance reminds us that practice makes (art) history. Free Palestine. Trans Liberation Now.

About the authors

-

Fiona Anderson is an art historian based in the Fine Art department at Newcastle University. Her work explores queer art histories from the 1970s to the present, particularly in the context of the ongoing HIV/AIDS epidemic and in relation to preservation and archiving practices. She is the author of the book Cruising the Dead River: David Wojnarowicz and New York’s Ruined Waterfront (University of Chicago Press, 2019), which examines the erotic and political roles that New York’s post-industrial landscape played for various queer communities in the city, and co-editor, with Glyn Davis and Nat Raha, of “Imagining Queer Europe Then and Now”, a special issue of Third Text (January 2021). Fiona’s writing has also been published in journals such as Performance Research, Journal of American Studies, and Oxford Art Journal. She is also a DJ. Her radio show and club night Wildflowers offers a queer feminist and global perspective on country music, folk, and Americana.

-

Flora Dunster is a Senior Lecturer at Central Saint Martins, where she is course leader of MA Contemporary Photography; Practices and Philosophies. She works on histories of queer and lesbian photography in the United Kingdom. She is co-author with Theo Gordon of Photography—A Queer History (Octopus/Ilex, 2024). Her writing can also be found in the journal Third Text and in The Routledge Companion to Global Photographies and Resist, Organise, Build: Feminist and Queer Activism in Britain and the United States during the Long 1980s, among other publications. She is co-editor of this special issue of British Art Studies with Fiona Anderson, Theo Gordon, and Laura Guy.

-

Laura Guy is a Reader in Gender, Sexuality, and Culture at the Glasgow School of Art. Her writing on the interactions of art and design with feminist and queer politics has been published widely. She is co-editor with Glyn Davis of Queer Print in Europe (Bloomsbury, 2022) and editor of Phyllis Christopher’s artist monograph Dark Room: San Francisco Sex and Politics, 1988–2003 (Book Works, 2022). In 2023–24, she was principal investigator on the Carnegie Trust-funded research project “Remapping the City of Culture through Grassroots LGBTQ+ Cultural Production”. With Fiona Anderson, Flora Dunster, and Theo Gordon, she is co-editor of this special issue of British Art Studies dedicated to queer art in Britain since the 1980s.

-

Theo Gordon is Leverhulme Early Career Fellow in History of Art at the University of York, working on a book provisionally titled “Viral Landscapes: Art and HIV/AIDS in the UK”, due in 2026. He has published widely on modern and contemporary art, with essays on Helen Chadwick, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Douglas Crimp, Sunil Gupta, and other artists in journals including Oxford Art Journal, Art History, and InVisible Culture, and reviews regularly for Burlington Contemporary. He is co-author with Flora Dunster of Photography—A Queer History (2024) and editor of We Were Here (2022), a book of Gupta’s essays for Aperture.

Footnotes

-

1

“Rebel Dykes Documentary Launches Crowdfunder”, The Punk Site, 18 March 2017, https://www.thepunksite.com/news/rebel-dykes-documentary-launches-crowdfunder. ↩︎

-

2

Rebecca Nicholson, “‘Sex Workers, Reggae Girls, Squatters, All the Ones Who Didn’t Fit In’: How Rebel Dykes Reveals a Secret Lesbian History”, The Guardian, 11 November 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/film/2021/nov/11/rebel-dykes-film-sex-workers-reggae-girls-squatters-siobhan-fahey-gay-rights. ↩︎

-

3

See, for example, Johanna Burton, Eric A. Stanley, and Reina Gossett, eds., Trap Door: Trans Cultural Production and the Politics of Visibility (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2018). ↩︎

-

4

“Derek Jarman’s Prospect Cottage Saved for the Nation”, Creative Folkestone, https://www.creativefolkestone.org.uk/news/2020/04/derek-jarmans-prospect-cottage-saved-for-the-nation/. ↩︎

-

5

“The long history of queer being employed as an insult contributed to its reclamation in the 1970s and 1980s, as a badge of protest. In the early 1990s, Queer Theory began to emerge, pioneered by scholars such as Judith Butler (b. 1956) and Eve Sedgwick (1950–2009)” (Clare Barlow, “Introduction”, in Queer British Art, edited by Clare Barlow (London: Tate, 2017), 13). ↩︎

-

6

Speaking at the “Imagining Queer Europe” conference in Edinburgh in March 2019, Mandy Merck asked “Is there a British queer theory?”, noting that most of the theorists who are associated with gay and lesbian cultural writing in the United Kingdom in the 1970s and 1980s “came out of a sociological version of cultural studies which they taught, rather than the psychoanalytic or philosophical perspectives that led to queer theory”. See Mandy Merck and Laura Guy, “Deviations and Conversions, Seventies Style”, Third Text 35, no. 1 (2021): 2–14, DOI:10.1080/09528822.2020.1864975. ↩︎

-

7

“Instituting Queer Art in Britain”, British Art Studies 27 (2025), DOI:10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-27/conversation. ↩︎

-

8

“If we have a greater presence, as artists, on the bookshelves, in the galleries, in the universities, on the television, and in the press, would we spend time talking here? We should do, but would we? Will we continue to do so when we are experimenting with different ideas, new collaborators, new museums, new journals, and new publishers? Will we talk about the 1980s then?” (Lubaina Himid, “Inside the Invisible: For/Getting Strategy”, in Shades of Black: Assembling Black Arts in 1980s Britain, ed. David A. Bailey, Ian Baucom, and Sonia Boyce (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005), 42). ↩︎

-

9

Nat Raha and Mijke van der Drift, Trans Femme Futures: Abolitionist Ethics for Transfeminist Worlds (London: Pluto Press, 2024), 121. ↩︎

-

10

The ruling was made on 16 April 2025: Judgment For Women Scotland Ltd (Appellant) v. The Scottish Ministers (Respondent), [2025] UKSC 16 (on appeal from [2023] CSIH 37), https://supremecourt.uk/uploads/uksc_2024_0042_judgment_aea6c48cee.pdf. ↩︎

-

11

David A. Bailey and Stuart Hall, “Critical Decade”, TEN.8 Photo Paperback 2, no. 3 (Spring 1992): 4. ↩︎

-

12

Catherine Grant, A Time of One’s Own: Histories of Feminism in Contemporary Art (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2022), 15. ↩︎

-

13

Grant, A Time of One’s Own, 4. ↩︎

-

14

Gail Lewis, “Whose Movement Is It Anyway? Intergenerationality and the Problem of Political Alliance”, Radical Philosophy 214 (April 2023): 67, https://www.radicalphilosophy.com/article/whose-movement-is-it-anyway. ↩︎

-

15

“Resisting Relations”, Goldsmiths, University of London, 6 June 2019, https://www.gold.ac.uk/calendar/?id=12565. ↩︎

Bibliography

Bailey, David A., and Stuart Hall. “Critical Decade”. TEN.8 Photo Paperback 2, no. 3 (Spring 1992): 4–7.

Barlow, Clare. “Introduction”. In Queer British Art, 1861–1967, edited by Clare Barlow, 10–17. London: Tate, 2017.

Burton, Johanna, Eric A. Stanley, and Reina Gossett, eds. Trap Door: Trans Cultural Production and the Politics of Visibility. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2018.

Goldsmiths, University of London. “Resisting Relations”. 6 June 2019. https://www.gold.ac.uk/calendar/?id=12565.

Grant, Catherine. A Time of One’s Own: Histories of Feminism in Contemporary Art. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2022.

Himid, Lubaina. “Inside the Invisible: For/Getting Strategy”. In Shades of Black: Assembling Black Arts in 1980s Britain, edited by David A. Bailey, Ian Baucom, and Sonia Boyce, 41–47. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005.

Lewis, Gail. “Whose Movement Is It Anyway? Intergenerationality and the Problem of Political Alliance”. Radical Philosophy 214 (April 2023): 64–74. https://www.radicalphilosophy.com/article/whose-movement-is-it-anyway.

Merck, Mandy, and Laura Guy. “Deviations and Conversions, Seventies Style”. Third Text 35, no. 1 (2021): 2–14. DOI:10.1080/09528822.2020.1864975.

Nicholson, Rebecca. “‘Sex Workers, Reggae Girls, Squatters, All the Ones Who Didn’t Fit In’: How Rebel Dykes Reveals a Secret Lesbian History”. The Guardian, 11 November 2021. https://www.theguardian.com/film/2021/nov/11/rebel-dykes-film-sex-workers-reggae-girls-squatters-siobhan-fahey-gay-rights.

The Punk Site. “Rebel Dykes Documentary Launches Crowdfunder”. 18 March 2017. https://www.thepunksite.com/news/rebel-dykes-documentary-launches-crowdfunder.

Raha, Nat, and Mijke van der Drift. Trans Femme Futures: Abolitionist Ethics for Transfeminist Worlds. London: Pluto Press, 2024.

Imprint

| Author | |

|---|---|

| Date | 14 July 2025 |

| Category | Introduction |

| Review status | Peer Reviewed (Editorial Group) |

| License | Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) |

| Downloads | PDF format |

| Article DOI | https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-27/intro |

| Cite as | Anderson, Fiona, Flora Dunster, Theo Gordon, and Laura Guy. “Introduction: Queer Art in Britain since the 1980s.” In British Art Studies: Queer Art in Britain since the 1980s (Edited by Fiona Anderson, Flora Dunster, Theo Gordon and Laura Guy), by Fiona Anderson, Flora Dunster, Theo Gordon, and Laura Guy. London and New Haven: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art and Yale Center for British Art, 2025. https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-27/intro. |