“Gay” Image-Making from Britain and India

“Gay” Image-Making from Britain and India: Sunil Gupta in the Late 1980s

By Gregory Salter

Abstract

This article explores Sunil Gupta’s 1988 series “Pretended” Family Relationships, emphasising its focus on interracial relationships, to place it firmly in the context of the management of sexuality and race by the British state in the 1980s and to highlight the transnational histories and experiences to which it gestures, with a particular focus on India and gay and lesbian Asians in Britain. In doing so, it frames Gupta’s practice as one of image-making with an interrogative approach to gay identity at this moment that surfaces a wide range of possibilities for building sexual lives and relationships in the process. The first section introduces the series and outlines its relationship to the uneven management of sexuality and race by the British state; the second turns to another series of images by Gupta, Exiles (1986), to address the transnational histories and fractured processes of recognition that underpinned his concern with the interracial a few years later; and the third turns back to “Pretended” Family Relationships to explore how the series is rooted in the complex navigation of family and personal life by gay and lesbian Asians in Britain. Across these sections, this article brings to the fore the particular interracial dynamics at the heart of Sunil Gupta’s 1980s practice, noting in the process their overlaps and divergences with existing frameworks in queer studies, and putting forward a transnational and long-term history of Section 28, which has been under-articulated in art-historical and historical scholarship to date.

Introduction

In 1988 Sunil Gupta began a series of colour portraits of gay male couples in interracial relationships, just as debates about a piece of legislation known as Section 28 of the Local Government Act were taking place among British politicians. Gupta quickly incorporated the controversy around this legislation, and the mobilisation of thousands of people against it, into his new work, expanding the portraits to include lesbian couples and adopting a phrase from its wording as the series title: “Pretended” Family Relationships.1 Since then, for many reasons, not least its title, the context of Section 28 has tended to dominate responses to the series. It is worth noting, however, the persistence of the aims behind the series’ original conception. “Pretended” Family Relationships was shown in August and September 1989 at a group show Partners in Crime at Camerawork in London, and a reviewer quoted exhibition interpretation material to note that it addressed, in part, “the ‘ambivalence in multi-racial’ gay male relationships”.2 “Pretended” Family Relationships is the focus of this article, through which I explore the fundamental relationship between the development of the Section 28 legislation, the responses of gay and lesbian people, and experiences and histories shaped by race. On the latter, it is crucial to acknowledge the continuing relevance of the broad category “black” for Gupta in this period and for understanding the series as a whole. Here, however, I focus particularly on the experiences of Asians in Britain and the additional context of India, largely because of how Gupta and other diasporic Asians like him were beginning to articulate their positions in these terms at this moment.3 In this analysis, I turn to a slightly earlier series by Gupta, Exiles (1986), which aimed, in his words, to “create images of gay Indian men”.4 While the experiences articulated in Exiles are in many ways very different from those addressed in “Pretended” Family Relationships, a dialogue between them spotlights the transnational histories and movements that shaped Gupta’s response to Section 28 and deepens an understanding of the 1988 series’ interrogation of family, relationships, and ways of building personal lives.

1This article responds, in part, to the interventions of queer of colour critique, particularly scholarship in this area that has addressed South Asian perspectives. This work has productively highlighted the differences and distinctions between Western investments in queerness and models of being and desire that sit outside of them, while also revealing how race and empire have shaped sexuality. Such frameworks help to illuminate aspects of “Pretended” Family Relationships and Exiles, though there is also a need to consider the precise management of sexuality and race by Britain and India in the late 1980s, which was influenced by the economic reorganisation of empire that had taken place in the post-war years. As a result, this article takes an art- and archive-led approach, and understands Gupta’s late 1980s practice as a form of image-making that sought to grapple with the uneven and competing histories that shaped desire and personal life at this specific moment.5 One concern that recurs in his practice, and that is the focus of my analysis here, is recognition: by the state, between people in relationships, within and across communities, and within families. In the sections that follow, I use recognition as a way of articulating the kinds of fractured dialogues that occur across “Pretended” Family Relationships and Exiles, accounting for and understanding the precise effects of the histories of race and sexuality from and across Britain and India in the late 1980s, and of surfacing an interracial history of Section 28.

5I begin by tracing how “Pretended” Family Relationships pictures the relationships between gay and lesbian people and the British state, both in the late 1980s and historically. In doing so, I show how sexuality and race were managed by the British government at this moment and how this series, and Gupta’s practice more widely, is only partially understood if it is approached via the frameworks of existing queer of colour critique. I then turn to selected images from Exiles to analyse the Indian contexts that helped to shape “Pretended” Family Relationships and to describe a dynamic of fractured recognition that is central to Exiles and a crucial presence in Gupta’s response to Section 28. Finally, I turn back to “Pretended” Family Relationships and explore the ways in which many of its images are shaped by the simultaneous navigation of a majority-white gay and lesbian scene and families of origin by Asian gay men and lesbians. Here, the dynamic of fractured recognition from Exiles recurs in a different context. By articulating the persistence of recognition in these series, I seek to show how Gupta’s response to Section 28 was shaped by much longer and transnational histories of sexuality and race and the negotiation of the ambivalence and potential of gay and lesbian relationships formed amid them.

“Pretended” Family Relationships and the State

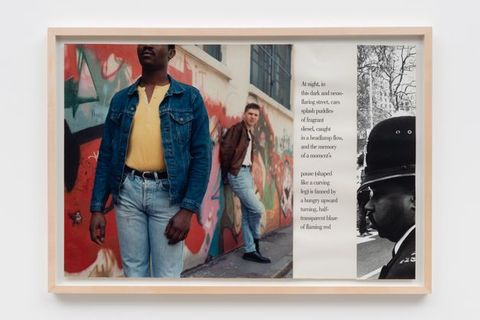

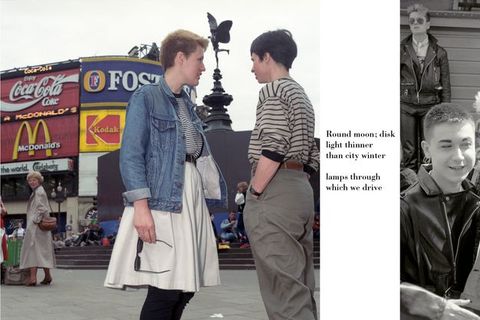

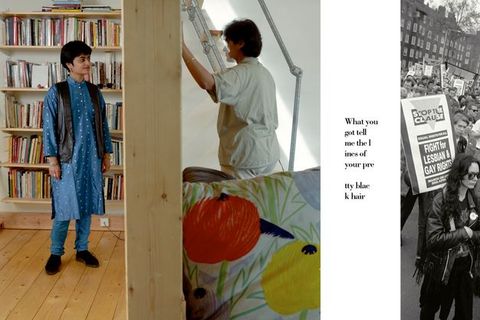

“Pretended” Family Relationships consists of twelve works, each taking a similar form: on the left and taking up around two-thirds of the work is a colour photograph of a couple—many but not all of them are interracial—represented in either a public or a private space; in the centre, there is a short snippet of poetry written by Gupta’s then partner Stephen Dodd, who lived in New York at the time; and, on the right, there are thin, cropped black-and-white photographs taken by Gupta at demonstrations against Section 28 in London. The form of the series is crucial—combining images of gay and lesbian couples with scenes of protest (connecting, in the process, the personal and the political) while also bringing Gupta’s photographs into dialogue with the poetry of his white partner. The form also demonstrates the long-term influence on Gupta’s practice of figures such as the North American artist Duane Michals, who used staged photographs alongside text to tell particular narratives. Here Gupta may have felt that the combination of image and text, which sometimes complement each other and sometimes contradict each other or work in tension, could be effective in countering two-dimensional representations of gay and lesbian relationships by the state and even well-meaning activists. In the process, they could convey a complexity and depth that was unavailable elsewhere and invoke states of togetherness and fracturing that were central to his response to Section 28, as we shall see. The series can also be viewed as a continuation of Gupta’s exploration of “constructed documentary”, an approach he used to critique and augment the approaches of documentary photography. While several of the colour portraits in the series appear like portraits, others are clearly staged to convey particular experiences that are less easily or frequently depicted. Exiles, which is discussed later in this article, also engages with these techniques. In “Pretended” Family Relationships, the staged colour photographs and their accompanying texts are joined by actual documentary photographs, taken at the Section 28 protests. The bringing together of these various elements—staged photograph, text, and documentary photograph—is bound up in a concern with the competing representational frameworks available to, and imposed on, gay and lesbian people in this moment. Gupta’s use of form fractures the totality of these frameworks and multiplies the possibilities within them.

The demonstrations against the legislation, events at which Gupta took the photographs that would form the final part of the series, had grown in scale as it was debated in Parliament in the early part of 1988. Between 15,000 and 20,000 lesbians, gay men, and supporters attended an anti-Section 28 march in Manchester on 20 February 1988, while 40,000 marched in London on 30 April; attendance at pride celebrations that summer swelled considerably in the wake of its enactment.6 The title of the series, as already noted, references the wording of Section 28 of the Local Government Act, which read as follows:

6(1) A local authority shall not—

(a) intentionally promote homosexuality or publish material with the intention of promoting homosexuality;

(b) promote the teaching in any maintained school of the acceptability of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship.

(2) Nothing in subsection (1) above shall be taken to prohibit the doing of anything for the purpose of treating or preventing the spread of disease.

It outlawed any teaching of homosexuality as a viable and acceptable identity and basis for life and discouraged institutions connected to local authorities from addressing the subject of homosexuality.

The origins of Section 28 lay in a combination of political developments. It came amid rising moral panic about the use of gay- and lesbian-related materials in schools. In 1986 there had been an outcry after various newspapers reported that a book titled Jenny Lives with Eric and Martin, which depicted a child being brought up by her father and his boyfriend, was being made available in schools. This flashpoint occurred during a drive by the Conservative government and sympathetic sections of the press to curb the work of local authorities, which were perceived to have been taken over by militant homosexuals and other left-wing groups and to be related to excessive state spending.7 The inclusion of gay and lesbian subject matter in school education remained on the political agenda during and after the 1987 election, helped along by the intervention of members of parliament such as Jill Knight and by Margaret Thatcher’s post-election address to the Conservative Party conference that warned: “Children who need to be taught to respect traditional moral values are being taught that they have an inalienable right to be gay”.8 The growing HIV/AIDS crisis may also have been a further contributory factor, for it hardened attitudes towards same-sex relationships, though Martin Durham has argued that “campaigners would oppose the ‘promotion’ of homosexuality, whether AIDS existed or not”.9 It is likely that right-wing individuals and groups marshalled the growing panic about HIV/AIDS to advance Section 28 rather than Section 28 being a direct result of the impact of the crisis.

7The wider motivations that drove Section 28 are signalled in the wording of the legislation. Anna Marie Smith noted that the emphasis on the term “promotion” signalled not a fear of difference in general, but an anxiety that difference would be subversive and impact society more generally—the fear that, in short, the desires and bonds of gay men and lesbians might disrupt the social order.10 By extension, the denigration “pretended” sought to delegitimise this subversive difference, rendering it dishonest and inauthentic.11 Gupta’s response was to produce a constructed series that sought to picture gay and lesbian relationships with breadth and diversity, situating his subjects in homes and public spaces and, in dialogue with the snippets of Dodd’s poems and the protest imagery, rendering them in multifaceted and unapologetic terms. Some of the portraits, which are of people in Gupta’s own friendship and professional networks, focus on actual couples, while several others depict people who were not real couples but posed in staged situations.12 Several of the relationships in “Pretended” Family Relationships, therefore, are pretended. In this way, Gupta responds to Section 28’s simultaneous demands for authenticity and concerns with legitimacy with a constructed series that casts into doubt the very viability of those demands.

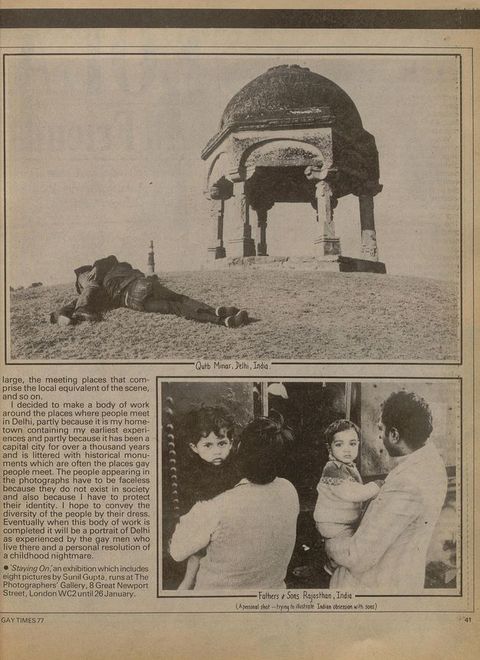

10The first artwork in “Pretended” Family Relationships directly addresses the impact of the state’s imposition of Section 28 (fig. 1). In the larger colour photograph on the left, Gupta depicts two men leaning against a wall together on the South Bank of the River Thames, somewhere between Lambeth Bridge and Westminster Bridge: on the left is an Asian man and on the right a white man; behind them, on the other side of the river, are the Houses of Parliament. In one respect, the image can be read as something of an unapologetic statement of presence, with the couple standing in public in front of the building in which the law that denigrates their relationship as “pretended” was passed. Something similar occurs in the black-and-white photograph on the right, where a policeman on horseback faces a crowd of protestors. Gupta’s extreme cropping of the image places the focus on two protestors in the crowd: a white man and a black woman. The stand-offs that Gupta stages here—between a couple and Parliament, between protestors and the police—establishes a tense and fractious relationship at the start of the series, here focused on gay and lesbian people and the state, rooted in the latter’s tactics of denigration and marginalisation. Such a dynamic is emphasised by the extract of Dodd’s poetry, placed between the images: “I call you / my love though / you are not my / love and it // breaks my / heart to tell you”. In the context of the artwork, these words cast the relationship between the depicted individuals and the state in particular terms, literally falling between the couple and Parliament and the cropped glimpse of the protest, cleaving them yet also binding them in fracture. In this way, their apparent reference to a dissolving relationship positions the gay and lesbian individuals affected by Section 28 in an intimate, yet fractured and disconnected, relation to the state.

At the same time, Gupta’s opening to the series in Untitled #1 immediately centres interracial couples or solidarities in both its photographs. On the left, the presence of the Asian man alongside his white counterpart also connects lawmaking in the British Houses of Parliament with India. It reminds us that it was the British-imposed Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code in 1860 that continued to shape the lives of those in India who sought same-sex contact, who may or may not have conceived of themselves as “gay” or “lesbian”, and who had to live in fear of arrest and to navigate the bribes and sexual favours solicited by the police if they were caught.13 Also present is the knowledge of the wider impact of British laws that criminalised homosexuality in other colonies beyond India.14 The looming horse-mounted policeman in the black-and-white photograph on the right serves, in turn, to connect the imperial management of colonised populations with contemporary policing, a connection that was repeatedly made by black activists during this decade.15 Given this context, #1 might be read as embodying Gayatri Gopinath’s compelling argument that “the barely submerged histories of colonialism and racism erupt into the present at the very moment when queer sexuality is articulated”.16

13Gopinath’s claim comes from a field of scholarship known as queer of colour critique, which emerged in the 2000s.17 This field offers a crucial framework for articulating the aims of Gupta’s practice, but we might also want to counter or adjust its assumptions, particularly in considering an artist based in Britain in the late 1980s. For clarity, I shall focus on Gopinath’s scholarship to explain this, since she is one of the key figures in the wave of queer of colour critique and focuses on South Asia. Alongside the fundamental argument that histories of sexuality are inseparable from histories of race and empire, Gopinath also notes that many queer histories remain rooted in dominant Euro-American liberal models of sexuality and frequently overlook non-heteronormative forms of desire that look and operate quite differently. For Gopinath and many other figures in queer of colour critique, forms of desire outside the West might be “incommensurate” with models such as “gay” and “lesbian”.18 Instead, she theorises the notion of “impossibility” to describe how a queer female South Asian subject position is produced by dominant nationalist and diasporic perspectives and supported by queer investments in Euro-American liberal models of sexuality.19

17As I elaborate in the next two sections of this article, the differences and divergences between models of sexuality and desire in Britain and in India are a clear concern of Gupta’s practice. I am, however, reluctant to adopt the language of incommensurability, and particularly its embrace of “impossibility”, to articulate what is being pictured in his art. Such language risks constructing its own binary, with undeconstructed Euro-American “gay” and “lesbian” identities on one side and non-Western models, here those of South Asia, on the other. It risks sidelining even as it attempts to highlight the same-sex intimacies that empire (and its afterlives) tried and failed to stop between coloniser and colonised, and the uneven forms of dialogue and exchange that occurred through them.20 In #1, Gupta pictures dialogue and intimacy, rooted in an articulation of a kind of fractured recognition by the state of people thinking of themselves as “gay” and “lesbian”, summoning histories in the process that entwine rather than separate them. I am conscious, too, that many of the perspectives of queer of colour critique grew out of the US academy in the late 1990s and early 2000s, when academics were naming the emergence of “homonormativity”, struggling with liberal demands for gay marriage, and seeking to rethink the terms of “queer” and reinvest it with mobility and radicality.21 Strategies such as Gopinath’s “impossibility” seek to disconnect queer from nationalist ideologies, their persistence in diasporic communities, and their investments in transnational capitalism, but Gupta’s practice does not attempt such a move from the vantage point of 1980s Britain, just before the activist and academic coining of “queer” as a position and way of thinking. Section 28, and Gupta’s response to it, need to be thought in the context of the precise economic management of sexuality and race in 1980s Britain by the Thatcher government, which was itself rooted in the persistence of a partial form of homosexual citizenship in Britain since the late 1950s—a complex, longer-term, compromised enfolding of gay men and, in less explicit terms, lesbians into the state that means that more recent queer approaches, though valuable, must be adapted here. The rest of this section outlines this context and explains how it shapes “Pretended” Family Relationships.

20Section 28 sought to cleave what was perceived as radical or militant homosexuality from its more respectable forms, despite the seemingly blanket denigration contained in its wording. As Anna Marie Smith has shown, most supporters of Section 28 spoke positively of and accepted “a law-abiding, disease-free, self-closeting homosexual figure who knew her or his proper place on the secret fringes of mainstream society”; the target of the legislation, Smith notes, was “the promiscuous, diseased, angry, flaunting, self-promoting and militant homosexual”.22 The distinction between the two was that the latter was perceived as having the potential to disrupt the social order, while the former would simply assimilate into it.23 This split was echoed within gay and lesbian communities too, with many more assimilationist people blaming militant activists for the increased pushback from right-wing groups.24 In this way, at its instigation, Section 28 can be viewed as the latest iteration of a strategy of containment of gay and lesbian desire by British governments, stretching back to the recommendations of the Wolfenden Report in 1957 and their enactment as law in 1967. Additionally, Smith argues that Section 28’s targeting of so-called militant homosexuals took its models from Powellism, which made some forms of blackness a scapegoat for perceived national decline, aspects of which had been absorbed into Thatcherism’s approach to race early on.25 Just as Section 28 distinguished between good and bad gay men and lesbians, so Thatcher’s policies on race and migration praised the hard-working, assimilating, family-focused, and entrepreneurial immigrant and denigrated those outside of this model as threatening the very stability of the nation.26 The political strategies relating to both demographics were part of a post-war project to manage marginalised populations amid long-term processes of decolonisation and deindustrialisation, forming them, through a partial, fractured form of recognition, into disciplined and (at this point) self-sufficient economic units, unlocking their consumer potential, and maintaining their social and cultural marginalisation.27 It is in this context that Gupta’s merging of a concern about interracial relationships with a response to Section 28 makes sense—the two issues were inseparable under the Thatcherite approaches to race and sexuality, with both groups (gay people and people of colour) subject to the economic management and structuring of their personal lives amid Thatcherism’s first wave of neoliberal polices.

22

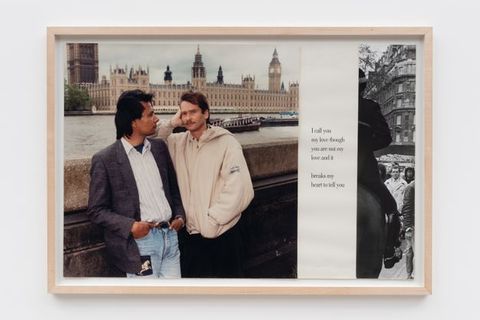

The economic management of race and sexuality in 1980s Britain was rooted in a very narrow definition of “family”. This definition was partly shaped by the drive to create a property-owning democracy and make the family and home the space where the “correct” forms of consumption were learned and where wealth could be transmitted through inheritance (rather than redistributed, as it would be under forms of socialism).28 Thatcher’s family was also based on a belief in individuals as inherently self-interested. This was not necessarily a belief in selfishness, but a sense that self-interested people would work hard and take care of themselves and that this, in turn, would produce a prosperous but also moral society. In this way, self-interest was a force for good because it “led, first, to concern for one’s family, then to concern for the well-being of the wider community, then the nation as a whole”.29 This rhetoric was a means of re-emphasising the family (instead of the welfare state) as a form of social security.30 This restrictive and economically determined model of family life finds its way into some of the colour photographs in “Pretended” Family Relationships, though its presence can be read as a gesture to the ways in which lives operated within and outside of state demands, shaped by choice, economic necessity, and the uneven effects of capitalism. In Untitled #4 (fig. 2) and Untitled #8 a gay and lesbian couple recline on beds, Untitled #10 finds a couple lounging on and in front of a sofa, while in Untitled #7 two women sit around a table in a walled outdoor space, as their dog leans in to nuzzle the arm of the woman on the left (fig. 3). At the same time, further dimensions are added to these potentially static images by their accompanying texts: for example, in #7, where the seated women are joined by poetry that evokes absence and that chimes with the smoking figure on the right: “Lighting / a cigarette // You’re not here // Lighting / a cigarette”. To the right of the text is a cropped shot of a protesting crowd holding banners, including one that reads “Never going underground”. Presence and absence give the couple depth and longevity: togetherness accompanied by separation. The joining of images of domesticity and protest, in turn, gestures to both the terms demanded by the state and the uncontainability of the lives it sought to confine there, whether through protest or through the forging of different forms of relation.

28

Alongside these domesticity-focused portraits, other images sought to complicate and further broaden understandings of gay and lesbian family relationships. For instance, Untitled #2 is recognisable as a scene of cruising on the street, with a white figure gazing after a black male who seems to have stopped, possibly before turning back (fig. 4). Dodd’s poetry, split into two verses across the phrase “a moment’s pause”, encapsulates an instance of fleeting, perhaps uncertain, recognition resonant with possibility. At the same time, the presence of a black policeman looking in from the photo on the right connects the policing of the Section 28 protests with the wider policing of gay and lesbian lives while functioning as a nod to the Thatcherite approval of “good” (i.e., aligning with the state) black subjects, as already noted. In Untitled #6, in comparison, two women stand close together in conversation in front of Alfred Gilbert’s Shaftesbury Memorial Fountain at Piccadilly Circus (fig. 5). The fountain is topped by a sculpture that is popularly known as Eros but actually depicts Eros’s brother Anteros, the god of requited love in Greek mythology. The photograph is composed so that the sculpture appears between the conversing women. While the couple are placed in a location associated with love, they are also on the edge of Soho, a district filled with gay and lesbian bars and businesses at the heart of the capital and the nation. The implication is that this particular kind of love is very much present in British society, but this is countered by elements that undermine or temper it, however. In the background, to the left of the couple, a woman turns from the direction her body is facing to glance at them; one of the couple is so positioned as to notice this glance—of intrigue or disapproval—out of the corner of her eye. Gupta has chosen a text by Dodd that describes a journey undertaken at night—“Round moon; disk / light thinner / than city winter // lamps through / which we drive”. Together, all these elements suggest public surveillance and lives lived somewhat out of sight, in contrast to the hypervisibility of the leather-clad figures in the accompanying protest snippet. The Shaftesbury Memorial Fountain’s reference to returned love is discordant with the state’s relationship to the desires pictured here, drawing us back to Dodd’s invocation of fractured intimacy that Gupta deployed to open the series in #1.

What is notable about #2 and #6 is that they focus on forms of intimacy that are not readily recognised by the state as legitimate or desirable, whether that involves cruising or simply closeness with a partner in public. In doing so, they focus on other moments of recognition—wordless forms of acknowledgement that may lead to sexual contact in cruising or forms of surveillance in public by others, the latter borne in different ways by the subjects of the images in #6. These artworks from “Pretended” Family Relationships build on the series’ opening evocation of the state and its historical and current management of race and sexuality, and touch on the range of gay and lesbian intimacies and desires outside the narrow confines of government legislation, evoking their rich, at times cautious, everyday persistence. By combining photographs of couples and protests with texts to reveal the fleeting, less visible or representable, aspects of gay relationships, Gupta’s series directly challenges the denigration of these relationships as “pretended” through complicated, multifaceted, and non-static evocations of their dynamics. It is not just one form or model of family life that is at stake but a whole spectrum of possibilities. What the state does and does not recognise as legitimate desire or ways of being are subtly and persistently dramatised across the series, and consistently narrated as love—its absence, its connection, and its fracture.31 In the process, the relationships that Gupta dramatises across the series sprawl, resistantly and messily, across the binaries dictated by the state (“good” gay men and lesbians versus “bad” ones) or even those shaped by queer perspectives in our moment (which may privilege oppositionality over non-oppositionality, for instance). This does not suggest that Gupta pictures moments of assimilation at times, but simply that his response to Section 28 is complex, shaped as much by ambivalence and negotiation as by protest. This is a complexity that we can understand, I argue, by tracing the instances of fractured recognition he depicts to the uneven management of sexuality and race in Britain—this is a relationship that produces Gupta’s subjects, binds them to the state and capitalism, yet produces forms of resistance and variety at the same time. These are the terms in which Gupta articulates his response to Section 28, with its focus on the interracial. In the following sections, I explore the implications of this in terms of the experiences of Asian people in particular.

31Transnational Recognition in Exiles

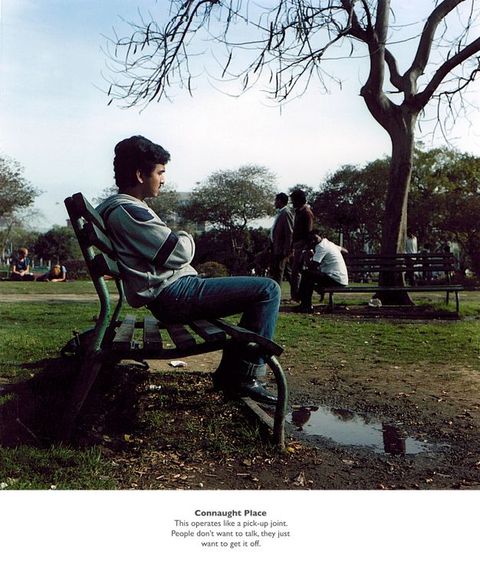

Stepping back from “Pretended” Family Relationships, this section turns to examine some of the artworks that were part of a slightly earlier series by Gupta—Exiles (1986), which aimed, as I noted earlier, to “create images of gay Indian men”. The series was made in Delhi, the city of his birth, on a return visit there, following several earlier trips between 1980 and 1983.32 It consists of twelve works that combined staged photographs taken in Delhi with snippets of text that originated from conversations Gupta had with men there. To create work about a scene that he had left in 1969 when he migrated to Montreal in Canada with his parents, he contacted men through his own personal network and by positioning himself in cruising spots.33 Those who agreed to appear in the series were largely middle-class men whom Gupta knew or with whom he was able to make contact. Some of them turn away from the camera and are hence anonymised, while others show their faces. I have turned to Exiles not because the experiences depicted are comparable to those in “Pretended” Family Relationships—I do not seek to conflate the very different contexts and forms of desire addressed across the series. What Exiles does provide, however, is an insight into the changing nature of what Westerners and Indians in diaspora would have named as “gay” experience in India, particularly as Euro-American models of desire began to interact unevenly with family and class. It is also part of a wider series of discussions about “gay Indians” that took place tentatively within India and among its diaspora, discussions that frequently hinged on faltering and imperfect processes of recognition. In this section I turn to Exiles to deepen and define more securely the processes of fractured recognition at which I gestured in the previous section, a process that emerges alongside the precise negotiation of family by “gay Indian men”. The dynamic of recognition and family persists in “Pretended” Family Relationships, as I shall show in the final section.

32

The first artwork in Exiles is Connaught Place (fig. 6), a park at the centre of one of New Delhi’s main financial, business, and commercial districts and a popular cruising area. In Gupta’s artwork, a despondent Indian man sits alone on a bench. In the background, a group of three Indian men cluster around another bench, one of whom looks over at the man in the foreground, suggesting the possibility of some kind of connection, while the other men gaze in another direction across the park. To the left, two white people lounge on the ground. Connaught Place had been established for some time as a cruising space for Delhi residents. Gupta knew as much from having lived in the city in the 1960s, and it had registered in Western gay magazines such as Gay News and Ciao! (a gay travel magazine) by the 1970s.34 It attracted largely “workers, lower- and middle-class, white-collar workers and small businessmen” who have either married or plan to marry and who did not identify with the Western category “gay”, with which only a small minority of wealthier Indians did.35 The text accompanying Gupta’s Connaught Place reads: “This operates like a pick-up joint. People don’t want to talk, they just want to get it off”. This snippet is ambiguous, encapsulating the unsteady readings that Exiles might elicit: It may be a simple statement of fact about the dynamics at Connaught Place or an expression of frustration with these dynamics and a desire for something more than the fleeting sexual contact offered by this public space. The central image of the seated lone man, both within and looking beyond this world, can be aligned with both interpretations.

34In the late 1970s the very small number of people who began identifying as “gay” began to organise in India. A gay liberation group formed in Bombay in 1977 and the following year a gay and lesbian newsletter, Gay Scene, was set up by Dhruvajyoti Roy-Chowdhury in Calcutta; it appears to have run for just two issues. They—largely wealthy or financially independent individuals who had either travelled abroad or, through education or work, had easy access to Western ideas—also began to make their voices heard in the Western gay press. By the early 1980s letters from seemingly isolated gay men and lesbians in India, usually seeking information and pen pals, were being published.36 The gay press also published news of the formation of small-scale groups of gay people. For example, a conference brought together forty delegates in Hyderabad in 1982, while a gay association called Lib-India had formed in Delhi by 1985.37 The growth in visibility of still relatively small groups of gay- and lesbian-identifying people in Indian urban areas was helped by the emergence of a commercial gay press in the West in the 1970s and the growing circulation of gay publications. Structural shifts in the Indian economy following a sustained period of modernisation, together with shifts in global capital, gave wealthier people in India greater mobility.38 These small-scale identifications with categories such as “gay” and “lesbian” in India occurred alongside other models of desire that were much more widespread. For instance, akshay khanna has articulated such models as a “sexualness” that “flows through people without constituting them as subjects”, underlining how sexual object choice and personhood for many Indian men do not align in the same forms as they do in the West.39 The simultaneous presence of differing models of desire undergirds the interactions of diasporic Indians like Gupta with their home on their return, as we shall see.

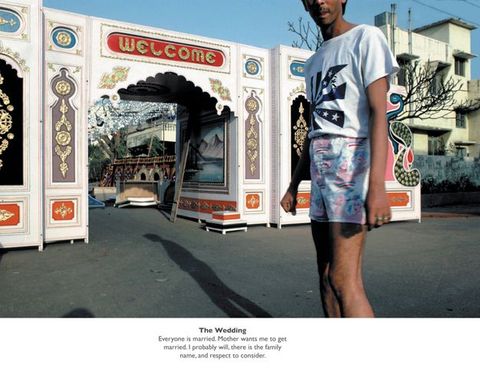

36In 1985 Gay Times published an essay on and photographs from Gupta’s trips back to India in the early 1980s (fig. 7a–b). In his essay, Gupta describes trying to talk to a cross-section of men at particular cruising sites, notes that “most people did not identify themselves as being gay”, and reasons that this is a result of the influence of the extended family and its economics: caste-dictated arranged marriages were a vital and unquestioned means of achieving social security, while few people had the privacy or space at home to “come out”.40 These observations chime with the vast majority of men who engage in same-sex intimacies, including those who identify as gay, regarding marriage as “an inescapable social duty” that offered “security and protection … against sickness, old age, and adversity”.41 For many, same-sex relationships or intimacies could “coexist with the obligations and privileges of marriage, and … function as primary erotic and emotional relationships”, while remaining largely unrationalised and unexplained.42 Gupta built such a perspective into another image from Exiles. The Wedding depicts a man in front of a decorative archway featuring the word “Welcome”, intended for a wedding or some other family-focused celebration (fig. 8). He turns from this celebratory yet somewhat ominous portal, his shadow falling towards its entrance to suggest his inevitable path. The accompanying text reinforces this reading: “Everyone is married. Mother wants me to get married. I probably will, there is the family name, and respect to consider”. The distinction between a largely unrationalised same-sex contact and the bonds and obligations of family life is crucial in Exiles, and sheds further light on the complexities of “Pretended” Family Relationships.

40

In 1986 Gupta and the Delhi-based journalist Ashish Kumar collaborated on an article for Gay Scotland, in which they articulated the sense that same-sex intimate contact in India was banished to operating outside the family and its institutions:

43New Delhi, 6pm. The fashionable shops of Connaught Place have just closed, the din of shoppers is dying down, the families and sightseers occupying the central park are being replaced by men of all ages from a broad spectrum of Indian society. In the twilight, framed by neon-lit signs, homosexual men cruise each other in a rare public display of their sexuality. Few words are exchanged. It is a society which acknowledges its homosexuals—but not its gays.43

Here, Connaught Place represents a perceived restrictive dilemma for “gay Indians”. The article’s headline—“In India: Closeted by Caste and Class”—translates this for a British audience into a kind of closeting, although the text notes more subtly that such a framework is not relevant in India. A lack of acknowledgement—or silence, as Gupta and other activists have frequently called it—more accurately encapsulates the position of Indians who were beginning to be recognised, or not, as “gay”.44 These tensions—between diasporic Indians hoping to recognise people like themselves in their country of origin and the relative silence, lack of naming, and disconnections between sexual desire and personhood that were present in India—are at the heart of Exiles and wider related discussions. These tensions and the differences at which they point are crucial to maintain here, while also tracing the ways in which Gupta and others like him sought to bridge the gap with dialogue.

44At this point, Gupta was one of several internationally mobile Indian-born gay men who were addressing gay life in India and operating in networks for gay men who had left India. Trikon, a group for South Asian gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender people, was founded in San Francisco in 1986, while Shakti, a group for South Asian gay men and lesbians, followed in London in 1988 and spread throughout the United Kingdom. The position of these gay and lesbian people in relationship to India could be complicated. In late 1986 the Canadian magazine Body Politic printed a letter from a man called Ashok, who had returned to India from the West as an out gay man. He recounts experiences of picking up men in Delhi and Bombay noting, like Gupta, that these men do not identify as gay. But he still threads together an unsteady connection:

45On this trip, I met few people who were openly gay, or who even identified with being gay. At times, I felt like a stranger and an outsider because I was gay and I thought of myself as such. And yet, I felt I was one of them. I, too, had spent a good part of my life in hiding from others, in concealing my emotions; I understood the despair of a life devoid of friends and support systems, the compromise of marriage and a life of pretence. Never mind the good or the bad, the trip showed me that gay people were there.45

Ashok’s words convey a contradictory sense of connection, where he is separated from the men in India by different models of sexuality but also connected by what are perceived as fundamental and universal experiences of isolation and concealment. The term “gay” is restated at the end, and used defiantly here, despite the differences and lack of identification, as a leap of connection rather than a simplification.

The moves of recognition and, we might say, misrecognition across these accounts is instructive, and is something we could preserve and work with rather than “correct” or flatten. They emerge from a particular material context—the simultaneity of and tensions between the slowly increasing presence of Western models of “gay” and “lesbian” in India and the perseverance of different models of desire and their relation to personal life and family. These find a particular voice in (but are not solely reducible to) the observations of diasporic Indians returning to their homes and which had been the product of increasingly transnational flows of media, capital, and people after the 1960s. I conceive of recognition here in terms of Laura Doan’s queer critical history, which she applied to artworks in a generative article that responded to Tate Britain’s 2017 exhibition Queer British Art, 1861–1967. Acknowledging a desire by contemporary audiences, and the institutions tasked with engaging them, to find contemporary models of gender and sexuality in the historical artworks and objects on display and thus to see themselves there, she notes how this can lead to instances where “recognition constitutes misrecognition” by those who look.46 While the words of diasporic Indians such as Ashok are not a contemporary misreading of the past, Doan’s attention to processes of recognition between queer subjects is instructive, not to admonish subjects for what we might perceive as misrecognitions but to draw attention to moments of tension between “queer” subjects who do not meet on solid ground (fig. 9). Gupta made such tensions part of Exiles. For instance, in Humayun’s Tomb, a complex work focusing on a historical site that Gupta knew well, from his youth, as a cruising ground, an Indian man stands with his back to us, facing the tomb, while a white male figure walks towards him. The composition appears to dramatise the potentially discordant relationship between Indian and Euro-American models of desire, with the ambiguity of whether the oncoming white figure will pause to meet the Indian figure or breeze straight past him. The accompanying text, meanwhile, disparages “Americans—talking about AIDS and distributing condoms … They’re always telling us what to do”.

46

We can add to Doan’s insights those of Anjali Arondekar, who has written on approaches to the colonial archive of sexuality in India. Working against approaches that might aim to recuperate “queer” South Asian subjects from the colonial archives in which they are notably absent, Arondekar advocates for an approach to the archive that thinks of it, crucially, as “more fractious than cumulative, more a space of catachresis than catharsis”.47 Doan and Arondekar both refuse to mould subjects into “our” terms but instead are attentive to what emerges in moments where we allow recognition to falter, where misrecognition occurs yet still binds. In this light, we can see the work that “gay” does in Ashok’s account, naming a desire for similarity, a recognition of difference, and a persistence of some kind of attachment within that difference. This is a complex relation that should not be smoothed out into either broad similarity or incommensurate difference, one that clearly has a presence within Exiles. It is also a dynamic of recognition that we can take with us back to “Pretended” Family Relationships.

47Community, Family, and Recognition in "Pretended" Family Relationships

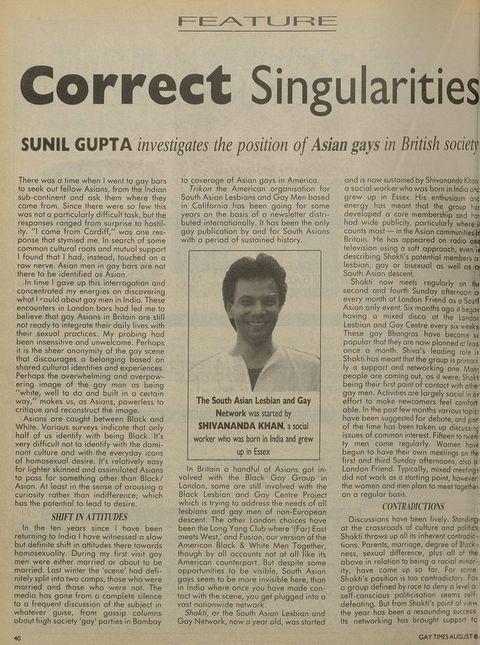

The uneven processes of recognition that Gupta dramatises in Exiles—a consistent aspect of discussions about “gay Indians” by voices in the diaspora that was refused or remade by Indians themselves—can help us understand the complex relationship between gay and lesbian communities, race (focusing specifically on the experiences of people from India and other parts of South Asia here), and forms of family life in Britain that fed into “Pretended” Family Relationships.48 Gupta himself addressed this directly in an article published in 1989 that sought to investigate the position of gay Asian people in British society (fig. 10a–b). He described seeking out “Asian gays” in bars and asking them where they came from: “the responses ranged from surprise to hostility. ‘I come from Cardiff’ was one response that stymied me”. He found that “Asian men in gay bars are not there to be identified as Asian” but were instead aiming to be subsumed into the “anonymity” of the gay scene. Gupta concluded that, as a result, Asian gay people were “invisible” in Britain, seemingly without ready-made or easily accessible networks of others like them and perhaps still adhering to a lingering colonial training to “imbibe the values of the dominant culture”.49 Gupta noted an emerging solution to this isolation and invisibility in the group Shakti, which offered support and community to an increasing number of Asian gay men and lesbians. Originally formed as the South Asian Lesbian and Gay Network in the summer of 1988 and headed by Shivananda Khan, an Indian-born social worker living in the United Kingdom, the group changed its name to Shakti, meaning “strength” in Sanskrit, in February 1989 and met twice a month at the London Friend drop-in centre on Caledonian Road.50 The establishment of a specific Asian network was typical of the splintering of the broad category of political blackness in the second half of the 1980s, and members of Shakti were initially recruited from the Black Lesbian and Gay Group, though, as Khan noted, this was not a fundamental break: “We can form coalitions with other groups, for example Black groups where we are talking about racism in the whole society. Being Asian is to do with culture, being Black is political, that’s the way people see it”.51

48

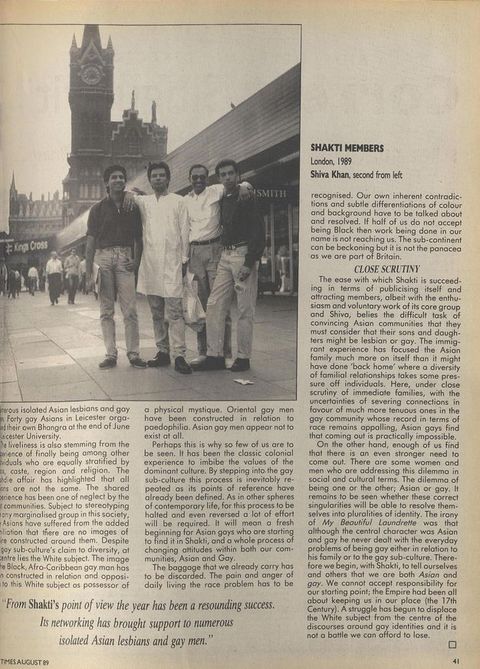

At the heart of many of Shakti’s aims and activities was the careful and complicated negotiation of questions of family by Asian gay men and lesbians. Khan articulated this in articles published in the gay press to mark a year since the group’s founding (fig. 11a–c). He emphasised the importance of the Asian community as “a nurturing space, filled with extended family networks, Asian cultural values, attitudes, beliefs, and religions”, which provided “tight bulwarks” against racism and “strong links” with the Indian subcontinent. These communities acted, in short, as “a vast extended family for those who live within them”. He noted, however, that gay men and lesbians also feel adrift from this community because of their sexuality: “if we try to express our ‘gayness’, our families feel that we have rejected them and our community”.52 This point is crucial—Khan was careful to note, like Gupta, that same-sex intimacy was at best tolerated and mostly ignored (“Historically, in the subcontinent it’s been relatively OK to be married and have sex with a man and not talk about it”)—but it was being gay, having “an emotional commitment to a partner, living together”, that caused trouble because it meant deviating from familial expectations.53 He noted that this could lead some to reject their Asian communities entirely and to immerse themselves in a majority-white gay and lesbian community, while others were understandably reluctant to break their ties with family and community: “their relationships are fragile, family duties come first and this can be destructive”.54 In response, Shakti developed a space for Asian gay men and lesbians to meet safely, alongside more mixed socials that were open to the wider community, and set up a family network to offer counselling and guidance to Asians wishing to navigate the relationship between their sexualities and their families: “We don’t suggest they come out to their family … We advise people to delay marriage and gradually educate the parents”.55 Gupta noted that this familial pressure could be particularly intense within families that had left India, as “immigrant experience has focused the Asian family much more on itself than it might have done ‘back home’ where a diversity of familial relationships takes some pressure off individuals”. In such contexts, severing these connections was more risky for gay men and lesbians as well as their families, so that “coming out is practically impossible”.56

52

Gupta struggled to get interracial couples to pose for the photographs in “Pretended” Family Relationships and had to rely largely on artists or activists who were already publicly out. Gupta and Khan’s writing provides one explanation for this: he was asking people, particularly if they were of Asian heritage, to operate in ways that were outside the structures and requirements of their lives. In response, he appears to have built reflections on or echoes of these competing demands into “Pretended” Family Relationships. For instance, the sudden pause by the black male figure in the street in #2, who is cruised by the white male figure looking at him, becomes a pivotal moment where to turn back and meet his gaze is to alter his path. Another photograph of two Asian women in a domestic space, Untitled #9 in the series, has a related sense of unease (fig. 12). The two women initially appear to turn to face one another, but Gupta has depicted them as divided by a wooden beam that bisects the space, placing a marker of division and fracture in an otherwise unified image. The dividing beam is echoed by the insertion of Dodd’s text between the colour image and the protest fragment, presenting the words of one lover to another in short sentences of largely two words each, the line breaks cutting into single words at times and undermining its articulation of connection. The narrow lines of poetry also recall the snaking line of figures in the protest, so that a momentary division between a couple becomes a collective experience in a different form. This oscillation between division and togetherness is echoed in the appearance of the two women in the colour photograph. The woman on the left turns to face her partner and is positioned as clearly visible to us. The woman on the right, whose hand is tellingly placed on the bisecting piece of wood, is less clearly seen, as a beam of light from a doorway or window on the upper level hits her face and splinters it into a less clear profile. Even in an image that appears to depict a partnership between two Asian people, Gupta retains an unsteady combination of outness, togetherness, division, and self-fracturing.

The series title—“Pretended” Family Relationships—begins to take on other connotations beyond its roots in the new Section 28 legislation. Gupta was aware that, while entering into an interracial relationship as an Asian gay man or lesbian for instance could bring love, security, and possibility, it could also mean a break with much wider familial and cultural structures. This was a concern for most gay and lesbian people of any ethnicity at this time of course. I have highlighted the experiences of Asian people here to draw out just one of the many complex negotiations pictured in the series and to acknowledge Gupta’s exploration of this particular viewpoint in accompanying articles at this time. Such a break with one’s family would have necessitated a kind of “pretending” in navigating the conventional coming-out model in the gay and lesbian community (even if this was negotiated unevenly by many) or discarding references to cultures or religions that were less legible to most people. At the same time, while images such as those in #2 or #9 can be read as concerned in part, with loss—of families, of cultures of origin, of self—they also hinge on moments of change or fracture that gesture at something different. There is a sense that the potential change of direction in #2 could lead not only to a navigation of racial difference but also to intimacy and connection that might not entirely transcend this difference but could nevertheless flourish. Or the fracturing of the woman’s face in #9 might signal not simply unmaking but also remaking: Note how her partner, wearing a kurta with jeans and a leather vest, whose entire body and face can be seen clearly, holds her gaze, counteracting the division of the wooden post. Neither of these artworks, to be clear, suggests a complete rejection of identity categories (whether of sexuality or of race) but they allow for loss or exile to be present in these images alongside, at the same time, a very clear sense of what might be gained—desire, new kinds of selves, new ways of living together within and across communities. Such possibilities are present, too, across the series, beyond the works that address specifically Asian subjects.

Gupta’s turn to interracial couples in “Pretended” Family Relationships may also have been driven by his dissatisfaction with a prominent representation of such a relationship in British culture a few years earlier in the 1985 film My Beautiful Laundrette, written by Hanif Kureishi and directed by Stephen Frears. Set during the Thatcher years, the film deals with various entanglements between Pakistani and English communities in south London, including the relationship between Omar (Gordon Warnecke), the son of an alcoholic former left-wing journalist from Pakistan, who is tasked with running a laundrette for his uncle, and Johnny (Daniel Day-Lewis), a member of a right-wing street punk group who resumes his sexual relationship with Omar and begins working at the laundrette (fig. 13). The film was well received in the gay press for depicting Omar and Johnny’s relationship “without apology and as if their passionate liaison were the most natural in the world” and “natural and happy despite outside pressures … This film goes a long way to making gays visible on film”.57 In an interview at the time of the film’s release, however, Kureishi commented: “I never set out to write a gay film … I’ve always written about class, about race, about money, about England today. Now I’ve crammed it all into one film”.58 Indeed, the film may be more concerned with addressing and satirising the Asian entrepreneur (a racialised figure who was considered favourably by Thatcherites for how they dovetailed with her social and economic policies), with Omar and Johnny functioning as a kind of metaphor for negotiation and assimilation in this era. Kureishi commented that the two main characters were “really the two sides of me … because I’m half Pakistani and half-English. I got the two parts of myself together … kissing”.59 Kureishi deployed a gay relationship as a metaphor for interracial experience, but from the point of view of #9 in “Pretended” Family Relationships this was not the solution it appeared to be, partly because the film assumed that such desire might unite racial categories rather than falter, or perhaps change them, and models of sexuality, irrevocably.

57

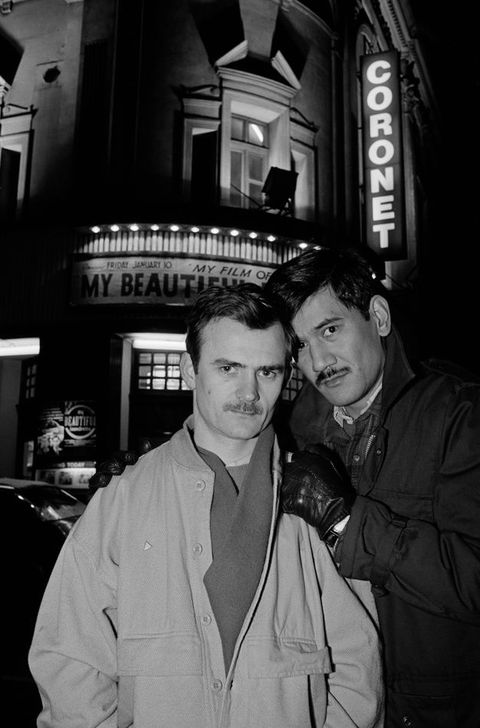

Gupta made numerous critical comments on the film in the years that followed, expressing his reservations about the praise given to a film written and directed by straight men over those directed by gay directors such as Isaac Julien, while also noting that “although the central character was Asian and gay he never dealt with the everyday problems of being gay either in relation to his family or to the gay sub-culture”.60 For him, the film was blissfully unaware of the realities of being gay and Asian, and ended up operating “completely against what little shreds of evidence we have about Indians coming out, where the problems can seem insurmountable”.61 In 1986 Gupta had made the hoardings advertising screenings of My Beautiful Laundrette at the Coronet in Notting Hill into the backdrop for an image simply titled Gay (fig. 14), part of a series he produced for a Greater London Council-funded exhibition at Brixton Art Gallery titled Reflections of the Black Experience in that year; Kureishi appears in another image in this series, Writer. Gupta and Dodd appear in the foreground, with Gupta grasping his partner’s shoulder (once again, he was unable to find another gay Asian man who was willing to pose for such an image), as if to answer the film’s prominent, though unsatisfactory, depiction of an interracial gay relationship with its real-life counterpart. Gupta’s hand on his partner’s shoulder here, creasing and folding Dodd’s jacket in the process, takes on an air of couple-rooted stability amid the gleaming horizontal and vertical billboards behind them, as if the lived intimacy and connection between these two men, rather than the broad inadequacies of wider cultural representations, matter most.

60

Given floundering representations such as My Beautiful Laundrette and the questions and possibilities raised by interracial relationships, let us turn back to #1, the artwork that opened this article and the “Pretended” Family Relationships series as a whole. The Asian figure is Shakti’s Shivananda Khan, who agreed to pose for the series soon after meeting Gupta for the first time: “I contacted Gay Times and they gave me Sunil’s name—the first thing he talked about was taking photographs of me for the ‘Pretended’ Family Relationships exhibition”.62 Earlier I read the combined images of the two men in front of the Houses of Parliament, the paired interracial figures seemingly facing down an approaching police horse, and Dodd’s melancholic poetry snippet—“I call you / my love though / you are not my / love and it // breaks my / heart to tell you”—as conveying the partial and incomplete terms of citizenship to which these figures were subject, whether they be British gay men and lesbians, former colonial subjects, non-white migrants (particularly in the wake of the British Nationality Act 1981), or people across all these categories.63 The British state’s assimilatory yet hostile manoeuvres may have been registered by these groups as contradictory and fractured gestures of connection. Gupta’s use of Dodd’s words draws us back, at the same time, to the realities and challenges of the interracial relationship itself. In one sense, Dodd’s text, used by Gupta in this context, might highlight the difficulties of an interracial relationship, expressed here as a kind of love attempted yet failed, though with an intimacy that lingers (“it breaks my heart to tell you”). But it also resonates with the possibility, outlined here, that gay and lesbian couples in interracial relationships may not always find themselves on shared ground. This is not to suggest separation in terms of cultural differences but to acknowledge the difficulties in navigating shifting and competing models of desire, relationships, and lives—think back to Khan’s comment on the Asian family’s difficulties when same-sex attraction tipped into “an emotional commitment to a partner, living together” (the very subject of Gupta’s series) or Gupta’s repeated insistences that coming out, for many Asians, was “impossible” and “insurmountable”. “Pretended” Family Relationships proceeds, as I have argued, to track the difficulties faced by those caught up in these longer transnational and interracial histories, which work both to bind people together and to distance them from each other, but it also insists on presenting both the relationships formed and the lives lived despite this and the possibilities that emerge in the process.

62In conclusion, we turn to one final artwork from the series, #4 (see fig. 2), whose main image depicts an interracial couple positioned on a bed. Stripped of the histories summoned by the public sites of #1 or #6 and less immediately coloured by the tensions of #2 and #9, this artwork appears to turn to a more quotidian kind of ease. Such a reading is reinforced by Dodd’s accompanying text: “Seeing you, seeing / me, it all becomes // so clear”. However, those surrounding artworks, and the wider concerns of the series, remind us that we should not interpret this only as an image of interracial domestic harmony. We might bear in mind, too, the complex interrogations of recognition across Gupta’s work elsewhere, such as in Exiles, that suggest that “Seeing you, seeing / me” may not be a statement about sameness but rather an assertion of difference. We can step back and read the artwork from left to right—from the interracial couple in a domestic setting, freighted now with the histories and contemporary struggles outlined earlier, to the central statement of difference in Dodd’s poem that ends not in disconnection but in clarity, and finishing with the protest snapshot on the right, a lone male figure perched on a wall, brandishing a placard shaped as an upturned triangle, emblazoned with the word “FIGHT”.

Reading across the artwork in this way, we move from the everyday fact of an interracial gay relationship, a recognition of difference, and a clarity that takes us towards the need for struggle. This “FIGHT” is, of course, most immediately related to the groundswell of activism in response to Section 28. But it also refers to other forms of fighting—of struggle and negotiation, both public and private—that are embedded in and articulated through “Pretended” Family Relationships. We may think of the work to hold on to the broadest range of possibilities of gay and lesbian family relationships, from those that align with Thatcherite ideals in the first wave of neoliberal economic policies in Britain to those that look or think or work quite differently. We may think of the long slow work of coming out to families of Asian or other minoritised heritages, which may not look like coming out in the conventional sense and may, in turn, begin to rework what identity and family themselves look like within and across Asian, and indeed gay and lesbian, communities. And it may even be the less easily discernible activity of facing long-term transnational ties, rooted in imperialism, restructured after decolonisation, and newly and potently mobile in an era when people and capital moved with greater intensity, and reworking them into forms of connection that may give rise to new ways of living together without losing sight of these histories. By bringing these histories and experiences together in “Pretended” Family Relationships, and centring the interracial in his response to Section 28 and his picturing of gay and lesbian relationships in Britain more widely, Gupta highlights an interracial history of Section 28 that is rarely acknowledged in scholarship or in public memory. This article has focused largely on aspects of the series that address people with families from India and other parts of South Asia specifically, and its concern with difference and dialogue resonates across the series. I have used a framework of instances of complex and fractured recognition between gay and lesbian people, between people who may or may not understand themselves to be gay or lesbian, and between such people and the state. By emphasising the complexities, ambivalences, and possibilities at the heart of the series and in Gupta’s practice more widely in the 1980s, I have sought to explore how they direct us towards queer histories that traverse the oppositional and the non-oppositional, where more uneven articulations of the effects of transnational interactions between race, sexuality, and class on people’s lives, relationships, and families might surface.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Sunil Gupta, Charan Singh, the anonymous peer reviewers, and the editors of this special issue.

About the author

-

Gregory Salter is an associate professor in art history at the University of Birmingham. He has been researching British art after 1945, with a particular focus on the histories of gender and sexuality. His book Art and Masculinity in Post-War Britain: Reconstructing Home was published in 2019. His current research project explores queer art in Britain between 1957 and 1988.

Footnotes

-

1

Gupta describes the conception of the series in Ldn-Post, “Sunil Gupta’s ‘Pretended’ Family Relationships Photo Series Acquired by the Museum of London”, London Post, 27 June 2022, https://london-post.co.uk/sunil-guptas-pretended-family-relationships-photo-series-acquired-by-the-museum-of-london. ↩︎

-

2

James Cary Parkes, “Shooting Partners”, Pink Paper 88 (2 September 1989): 12. The other artists in the Partners in Crime show—Hinda Schuman, Doug Ischar, and Kaucylia Brooke—also explored gay and lesbian relationships. ↩︎

-

3

In the first and final sections of this article, I largely use the word “Asian”, echoing the term deployed by Gupta and others like him in the late 1980s. In the second section, I use the word “Indian”, as these subjects are clearly rooted in that particular location. Occasionally, when speaking more generally, it has been necessary to use the broader umbrella term “South Asian”, a term that was used to define the remit of the group Shakti, for instance. On the history and, in the late 1980s moment, the persistence and fragmenting of the category of “political blackness”, see Rob Waters, Thinking Black: Britain, 1964–1985 (Oakland: University of California Press, 2019). ↩︎

-

4

Sunil Gupta, “Exiles”, https://www.sunilgupta.net/exiles1.html. ↩︎

-

5

I adopt the term “image-making” from Kobena Mercer’s “Dark & Lovely: Black Gay Image-Making”, in Welcome to the Jungle: New Positions in Black Cultural Studies (London: Routledge, 1994), 221–32, here, and use it in place of “photography” for a few reasons. Gupta’s practice is, of course, centred on photography, but it also builds in dialogues with film, media, text, and fine art. Mercer’s term is contemporary with the practices covered in this article, and it echoes Gupta’s own language about his practice (see n. 4, for example). ↩︎

-

6

Anna Marie Smith, New Right Discourse on Race and Sexuality: Britain, 1968–1990 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 229. ↩︎

-

7

Ibid., 188–89; Stephen Brooke, Sexual Politics: Sexuality, Family Planning, and the British Left from the 1880s to the Present Day (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 227. ↩︎

-

8

On the immediate prehistory of Section 28, see Martin Durham, Sex and Politics: The Family and Morality in the Thatcher Years (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1991), 111–17. Thatcher’s comment is quoted in Andy McSmith, No Such Thing as Society (London: Constable, 2010), 360–61. ↩︎

-

9

Durham, Sex and Politics, 122. ↩︎

-

10

Smith, New Right Discourse, 203. ↩︎

-

11

Philip A. Thomas, “The Nuclear Family, Ideology and AIDS in the Thatcher Years”, Feminist Legal Studies 1, no. 1 (March 1993): 36–37. ↩︎

-

12

Aside from one figure, whom I name in the final section of this article, I have not named the sitters in “Pretended” Family Relationships. While some of the sitters may be identifiable to those who are familiar with Gupta’s social and professional circle in London in the 1980s, the sitters are not formally named in the series itself, unlike in Lovers: Ten Years On (1984–86), for instance, which gives their first names. With this in mind, I have sought to maintain the more anonymous nature of this series rather than tying these artworks to particular individuals and their lives (aside from the aforementioned exception). In doing so, I am emphasising the ways in which our encounters with the sitters are not directed by names but by the histories, dynamics, and politics that emerge when we perceive them in the context of the work. ↩︎

-

13

For a discussion of how Section 377 was enacted from day to day in India, see Jyoti Puri, Sexual States: Governance and the Struggle over Antisodomy Law in India (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016), 42. Gupta recounted his own experience of police blackmail in Sunil Gupta, “The Hidden India”, Gay Times 77 (January 1985): 39–41. ↩︎

-

14

For this history, see Enze Han and Joseph O’Mahoney, “British Colonialism and the Criminalization of Homosexuality”, Cambridge Review of International Affairs 27, no. 2 (2014): 268–88. ↩︎

-

15

In the early 1980s the work of the London Metropolitan Police’s Special Patrol Group was viewed as a continuation of colonial practices by some activists, and the comparison was also made of the policing of racialised populations more generally: see Simon Peplow, Race and Riots in Thatcher’s Britain (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2019), 107, and Waters, Thinking Black, 106. ↩︎

-

16

Gayatri Gopinath, Impossible Desires: Queer Diasporas and South Asian Public Cultures (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005), 2. ↩︎

-

17

See, e.g., Cathy J. Cohen, “Punks, Bulldaggers, and Welfare Queens: The Radical Potential of Queer Politics”, GLQ 3, no. 4 (1997), 437–65; David L. Eng, The Feeling of Kinship: Queer Liberalism and the Racialisation of Intimacy (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010); Roderick A. Ferguson, Aberrations in Black: Towards a Queer of Color Critique (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2004); Martin F. Manalansan, “In the Shadows of Stonewall: Examining Gay Transnational Politics and the Diasporic Dilemma”, GLQ 2, no. 4 (1995), 425–38; Jasbir Puar, Terrorist Assemblages: Homonationalism in Queer Times, tenth anniversary expanded ed. (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017); Chandan Reddy, Freedom with Violence: Race, Sexuality, and the US State (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011). Much of the early work of queer of colour critique was collected in a special issue of Social Text: see David L. Eng, with Judith Halberstam and José Esteban Muñoz, “Introduction: What’s Queer About Queer Studies Now?”, Social Text 23, nos. 3–4 (2005): 1–15. ↩︎

-

18

Gopinath, Impossible Desires, 11. ↩︎

-

19

Ibid., 15–20. ↩︎

-

20

On this history, see Leela Gandhi, Affective Communities: Anticolonial Thought, Fin-de-Siècle Radicalism, and the Politics of Friendship (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2006). ↩︎

-

21

See, e.g., Michael Warner, The Trouble with Normal: Sex, Politics, and the Ethics of Queer Life (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999), and Lisa Duggan, The Twilight of Equality? Neoliberalism, Cultural Politics, and the Attack on Democracy (Boston: Beacon Press, 2003). ↩︎

-

22

Smith, New Right Discourse, 18. ↩︎

-

23

Ibid., 204, 207. ↩︎

-

24

Ibid., 20. This idea is echoed in Peter Drucker, Warped: Gay Normality and Queer Anti-Capitalism (Leiden: Brill, 2015), 283, where he also argues that, by the 1980s, lesbian and gay identity was “acquiring a hegemonic position in a new same-sex formation that fit increasingly well into the emerging neoliberal order” (242). ↩︎

-

25

On the connections and also the breaks between Powellism and Thatcherism, see Camilla Schofield, “‘A Nation or No Nation?’ Enoch Powell and Thatcherism”, in Making Thatcher’s Britain, ed. Ben Jackson and Robert Saunders (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 95–110. ↩︎

-

26

Smith, New Right Discourse, 22, 26–27. On Thatcherism’s limited embrace of hard-working, entrepreneurial racial minorities, see Matthew Francis, “Mrs Thatcher’s Peacock Blue Sari: Ethnic Minorities, Electoral Politics and the Conservative Party, c. 1974–86”, Contemporary British History 31, no. 2 (2017): 274–93. ↩︎

-

27

My thinking here is guided by David Evans’s work on legislation on homosexuality as forms of “sexual accumulation strategies”—David T. Evans, Sexual Citizenship: The Material Construction of Sexualities (London: Routledge, 1993), 50—as well as by recent comments on the deployment of race relations discourses: see Marc Matera et al., “Marking Race: Empire, Social Democrat, Deindustrialisation”, Twentieth Century British History 34, no. 3 (2023): 566–67. In the United States, Grace Kyungwon Hong has traced an “invitation to reproductive respectability” across the post-war decades, which also feels relevant in the different context of Britain: see Grace Kyungwon Hong, Death Beyond Disavowal: The Impossible Politics of Difference (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015), 7, 19–23. ↩︎

-

28

Heather Nunn, Thatcher, Politics and Fantasy: The Political Culture of Gender and Nation (London: Lawrence & Wishart, 2002), 110, 101. On Thatcherism’s property-owning democracy, see Matthew Francis, “‘A Crusade to Enfranchise the Many’: Thatcherism and the ‘Property-Owning Democracy’”, Twentieth Century British History 23, no. 2 (2012): 275–97. On distinctions between “good” gay consumers in family-like units and “bad” queers whose desires were less easily commodified, see Jon Binnie, The Globalisation of Sexuality (London: SAGE, 2004), 20. ↩︎

-

29

Florence Sutcliffe-Braithwaite, Class, Politics, and the Decline of Deference in England, 1968–2000 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018), 156. ↩︎

-

30

Melinda Cooper, Family Values: Between Neoliberalism and the New Social Conservatism (New York: Zone Books, 2017), 17; echoed in broad terms, specifically in relation to Britain, in Jane Pilcher, “Gillick and After: Children and Sex in the 1980s and 1990s”, in Thatcher’s Children? Politics, Childhood and Society in the 1980s and 1990s, ed. Jane Pilcher and Stephen Wagg (London: Falmer Press, 1996), 78. ↩︎

-

31

Glyn Davis has highlighted dissent as a crucial element of Gupta’s practice elsewhere: see Glyn Davis, “The Queer Archive in Fragments: Sunil Gupta’s London Gay Switchboard”, GLQ 27, no. 1 (2021): 121–40. ↩︎

-

32

Exiles was commissioned for the Photographers’ Gallery 1987 exhibition The Body Politic: Re-presentations of Sexuality, which also featured the work of Emily Andersen, Diana Blok, John Coplans, Andy Golding, Roberta Graham, Barbara Kruger, Rosy Martin, David Roberts, Hiro Sato, Jo Spence, Mitra Tabrizian, Susan Trangmar, Helen Chadwick, and Ken Hollings. On the commissioning and making of Exiles, see Natasha Bissonauth, “A Camping of Orientalism in Sunil Gupta’s ‘Sun City’”, Art Journal 78, no. 4 (Winter 2019): 101–2. ↩︎

-

33

Sunil Gupta and Anthony Luvera, “Mr Malhotra’s Party”, Source: The Photographic Review 79 (Summer 2014): 23–33. ↩︎

-

34

See Sunil Gupta, “Queering the Indian Street”, in We Were Here: Sexuality, Photography, and Cultural Difference (New York: Aperture, 2022), 106; Derek James, “A Letter from India”, Gay News 55 (26 September–9 October 1974): 11; and Jerry Daniels, “Gay India”, Ciao! 5, no. 6 (January–March 1978): 23–25. ↩︎

-

35

Jeremy Seabrook, Love in a Different Climate: Men Who Have Sex with Men in India (London: Verso, 1999), 5–6. I use Seabrook’s account here because it relates directly to a space such as Connaught Place. I do not take up his use of the term “men who have sex with men” to describe the people who use the park, a term that emerged through largely Western-directed responses to HIV/AIDS outside the West. For a history of the emergence of this term and a clear articulation of how it flattens and distorts experiences of gender and desire in India, see Naisargi N. Dave, Queer Activism in India: A Story in the Anthropology of Ethics (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012), 10–11, and Charan Singh, “Photographic Rehearsal: A Still-Unfolding Narrative”, Trans 11, no. 1 (2021), http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.7977573.0011.105. ↩︎

-

36

See, e.g., Anon., “GLF in India”, Gay News 126 (8–21 September 1977): 3; Anon., “Inside Burning”, Gay Community News 8, no. 4 (9 August 1980): 5; and Sajan Thomas, “Life in India”, Gay Times 82 (June 1985): 5. ↩︎

-

37

Anon., “First Indian Meet”, Gay News 234 (18 February 1982): 6; Ashish Kumar, “India”, International Gay Association Bulletin 1 (1985): 28. ↩︎

-

38

Seabrook, Love in a Different Climate, 5–6, 54. I am also thinking here of the wider economic shifts during and after the Emergency in the mid-1970s amid government investment in “modernisation”. See Emma Tarlo, Unsettling Memories: Narrative of India’s “Emergency” (New Delhi: Permanent Black, 2003), 29, and Christophe Jaffrelot and Pratinav Anil, India’s First Dictatorship: The Emergency, 1975–77 (London: Hurst, 2021). ↩︎

-

39

akshay khanna, Sexualness (New Delhi: New Text, 2016), 12. ↩︎

-

40

Gupta, “The Hidden India”. ↩︎

-

41

Seabrook, Love in a Different Climate, 10, 140, echoed in Shakuntala Devi, The World of Homosexuals (New Delhi: Bell Books, 1978), 6–7, 9. ↩︎

-

42

Ruth Vanita, “Introduction”, in Queering India: Same-Sex Love and Eroticism in Indian Culture and Society, ed. Ruth Vanita (London: Routledge, 2002), 3. ↩︎

-

43

Ashish Kumar and Sunil Gupta, “Gays in India: Closeted by Caste and Class”, Gay Scotland 24 (November–December 1985): 7. ↩︎

-

44

Silence is a concept evoked by gay Indians in the late 1970s: see Shashi Pandit in Anon., “A Passage from India”, Clone, May 1977: 13; Dhruvajyoti Roy-Chowdhury in the first issue of his Bombay publication Gay Scene, September 1978, 1–2; and Gupta in “India Postcard: or Why I Make Work in a Racist, Homophobic Society”, in We Were Here: Sexuality, Photography, and Cultural Difference (New York: Aperture, 2022), 41. For a more recent reflection on language as it relates to gender, sexuality, and desire in India, see Singh, “Photographic Rehearsal”. ↩︎

-

45

Ashok, “Letter from India”, Body Politic 133 (December 1986): 21. ↩︎

-

46

Laura Doan, “Then and Now: What the ‘Queer’ Portrait Can Teach Us about the ‘New’ Longue Durée”, Visual Culture in Britain 18, no. 1 (2017): 29–30. ↩︎

-

47

Anjali Arondekar, For the Record: On Sexuality and the Colonial Archive in India (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2009), 171. ↩︎

-

48

In this way I build on other scholars who have noted the transnational shape of Gupta’s practice, such as Bissonauth, “A Camping of Orientalism”, 105. ↩︎

-

49