Naughty Nuns and Saucy Sisters

Naughty Nuns and Saucy Sisters: The Queer Nun at the End of the 1980s

By Thomas Elliott

Abstract

Whether on the front line of protests or on the gallery wall, the nun was a figure with a queer appeal for artists and activists at the end of the 1980s. But what inspired queer people in late twentieth-century Britain to get the habit? In this article I examine the queer nun as she appears in the activism of the London House of the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, an activist group and order of gay male nuns, and in the photographic sequence Celestial Bodies (1990), produced by Jean Fraser for the touring exhibition Stolen Glances: Lesbians Take Photographs (1991). Situating these as part of the political and religious atmosphere of the period, I examine how the queer nun allowed Fraser and the London House to challenge and critique the political realities of their era. By placing these works alongside sources drawn from British art of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, I examine the place of the nun in visual culture in Britain, particularly her representation as a licentious and sapphic figure, before returning to the twentieth century to trace the trans-historical resonances of these connotations in the work of Fraser and the London House and their attempts to deconstruct and reappropriate socially constructed categories of sexuality and gender.

Introduction

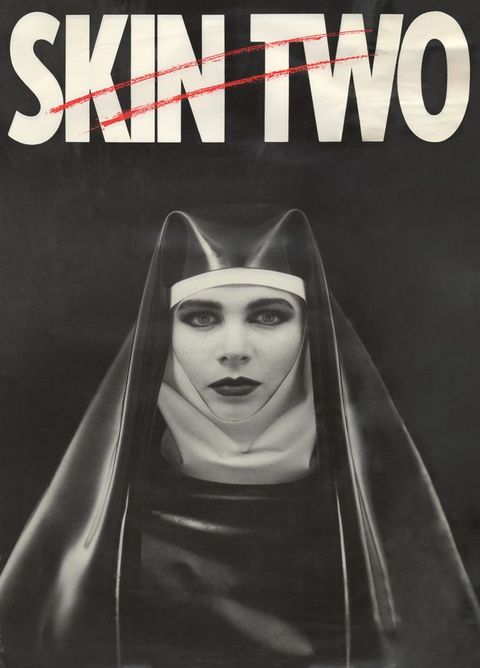

A beautiful young woman looks out at the viewer from the cover of issue 8 of the fetish magazine Skin Two (fig. 1). Her dark eyeshadow and painted lips complement the paleness of her skin, a contrast mirrored by her black-and-white rubber-wear outfit. Framing her face is the white strip of a bandeau and the folds of a white wimple. A black latex veil falls over her shoulders, beneath which she wears a black rubber scapula. The high gloss of the material shines in the light, lending a sense of tactility and physicality to the image. It is striking, sensual, seductive. And very clearly depicts a nun.

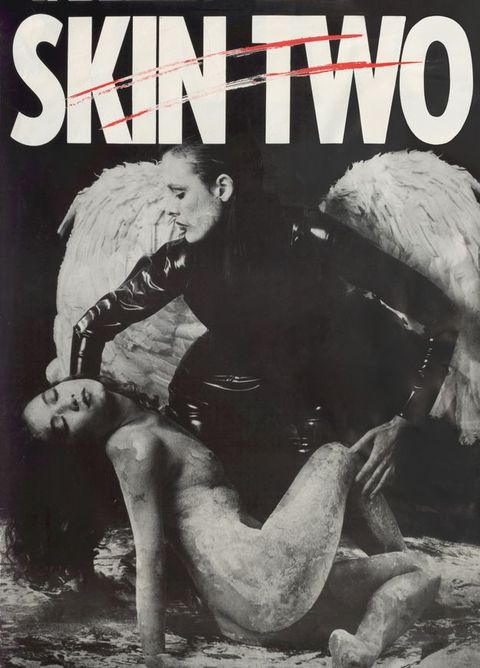

Skin Two, launched in 1984, was marketed to a polysexual fetish audience. Its goal was to celebrate the “hedonistic possibilities” of what was, at the time, a “fledgling fetish scene”, and it featured “what’s on” guides for the kink community, fetish-wear photoshoots, and reviews of parties and club nights alongside advice on kink and BDSM practice and “serious journalism”.1 Articles included the writing of queer S&M (sadism and masochism) pioneers such as Patrick Califia, legal guidance for kink practitioners, and articles on art, fashion, psychology, and sexuality.2 Early issues were published on a more or less yearly basis and were heralded by publicity posters featuring each new issue’s cover image. These were fly-posted across various London locations and distributed for promotional purposes around the fetish scene.3 A number of these posters were collected by the photographer Tessa Boffin, and her archive includes examples featuring the latex-clad nun of issue 8 and posters advertising issue 7 that show a female angel in black PVC cradling the body of a nude woman (fig. 2). The posters in Boffin’s collection, slightly water damaged, refer to shared queer spaces, night clubs, and fetish events where the alignment of the nun and other religious imagery with sex and deviance needed no explanation.

1

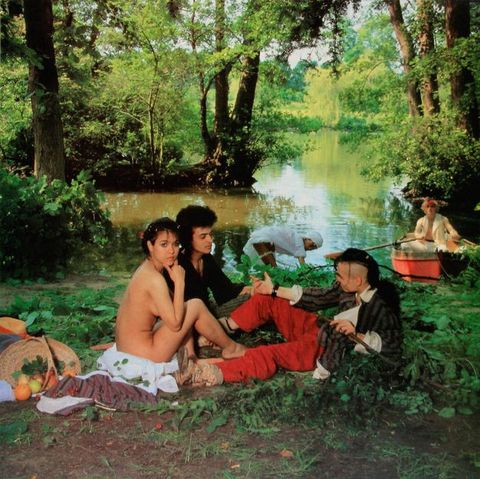

This article explores the nun as a figure with queer appeal in late 1980s and early 1990s Britain. I take as my focus the activism of the London House of the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, an order of gay male nuns who appeared, dressed in nuns’ habits, at protests and queer community events around the country,4 and Jean Fraser’s photographic series Celestial Bodies (1990). The latter was shown as part of the touring exhibition Stolen Glances: Lesbians Take Photographs (1991) and was made up of photographs depicting two nuns engaged in intimate moments; reading together, holding hands, lacing each other’s coifs, and, accompanied by a nude female companion, sharing a picnic and wine in a re-enactment of Édouard Manet’s Le déjeuner sur l’herbe (1863).5

4Both Fraser and the London House can be situated as part of what I consider a “turn to the religious” in queer art and visual culture in Britain at the end of the 1980s. Alongside a number of their contemporaries—including Derek Jarman, Tessa Boffin, Rotimi Fani-Kayode and his partner Alex Hirst, Sunil Gupta, and the American performance artist Ron Athey—Fraser and the London House made use of religious symbolism to convey a visual politics of queer resistance that allowed them to mount a critique of homophobia and to tease apart socially constructed categories of gender and sexuality. But what inspired their use of such religious imagery, especially the figure of the nun? And what made the nun in particular both an attractive and a useful figure for queer political resistance?

“A Vision in Black Habit and Wrinkled Wimple, Adorned with a Collection of Gay Liberation Badges”

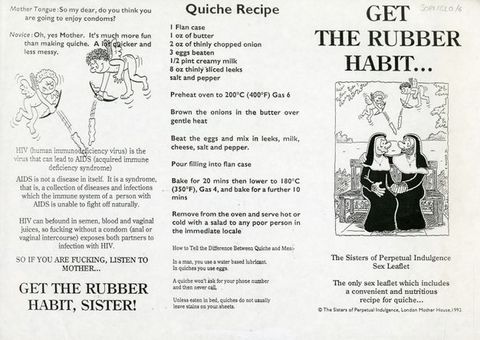

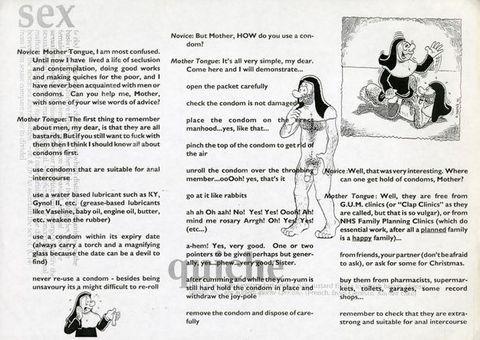

The London House of the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence was formed after a group of activist friends encountered the Australian sister Mother Ethel Dreads a Flashback at a kiss-in against homophobia organised by the queer direct action group Outrage! in September 1990.6 The event saw a large number of attendees, who gathered and kissed under the statue of Eros in Piccadilly Circus to protest against the Metropolitan Police’s continued victimisation of gay men for public displays of same-sex affection—kissing, holding hands, and so on.7 Inspired by Mother Ethel’s look, which the journalist Paul Burston described as “a vision in black habit and wrinkled wimple, adorned with a collection of gay liberation badges”,8 and driven by shared political beliefs, the group established the London House in the weeks that followed and quickly became an eye-catching presence on the activist scene.9 Many of the founding members were key players in the queer direct action groups ACT UP London and Outrage!, but the activism of the newly formed house extended beyond these two organisations.10 They were pioneers in safe-sex education and condom distribution, produced and distributed their own safe-sex guides (notably the first, and possibly only, safe-sex leaflet to include a recipe for a quiche!) and brought their style of provocative, irreverent, and unashamedly queer humour to causes as diverse as the anti-Gulf War movement and later the Countdown on Spanner campaign (figs. 3a and 3b).11

6

The newly formed London House existed as part of a wider international movement, with houses located in Europe, Australia, and the United States. The organisation was founded in San Francisco in 1979, its mission being the “promulgation of universal joy and the expiation of stigmatic guilt”.12 A leaflet distributed by the London House in the early 1990s described this mission in the following way:

1213The promulgation of universal joy is the mission which the Sisters carry out personally and collectively as an antidote to the oppressive effects of gender roles and behaviours forced upon women and men in our society. The Sisters try to exorcise the gloom of conformity and “proper” behaviour from their lives and the lives of others.13

“Stigmatic guilt”, they wrote,

14is the effect of centuries of scapegoating of gay people … gays are made to swallow lies about themselves. The stigma attached to being gay brings its own brand of guilt and self-oppression. The Sisters seek to expiate this on behalf of gay people. The Order’s mission is equally to the straight and the gay communities.14

Central to their activism was the practice of publicly manifesting as nuns. “Public manifestation” was intended to show their “vocation wherever people gather, but most of all in the Market Place”. This they accomplished through “the wearing of [their] habits and the perpetration of [their] presence”.15

15Dressing as nuns differentiated the group from other activists and allowed them to be more theatrical, more camp, and more immediately recognisable than many of their peers. This was an effective tactic at protests and actions, drawing the attention of the public and the press to the causes they supported and helping to defuse tensions. We get a sense of this in the photograph by Sandra Wong-Geroux showing two sisters at a protest in London being confronted by a member of the police (fig. 4). On the left is an American sister, wearing a wig and headpiece and the stylised face paint and make-up for which the American houses came to be known. To the right stands Sister Belladonna in Gloire de Marengo of the London House in a more traditional black-and-white nun’s habit. Behind them are a number of photojournalists, two of whom Wong-Geroux has captured in the process of documenting the scene.

To publicise their work, the London House created a pamphlet in 1992, in which they answered frequently asked questions about their activism. The answer to the second question, “Why do you dress up as nuns?”, was: “because we are nuns”. When asked about their habits, the group responded, “The habit is a uniform we wear which betokens our professed aim and maximises our visibility”.16

16The group also made use of the habit’s function as a symbol of authority and gravitas. A nun’s habit, like priestly vestments or the simple “dog collar” worn by vicars, serves as a marker of “sacred bodies ‘set apart’ for divine service”. While not professing to be religious or to be above the profane desires of the world (by any stretch of the imagination!), the London House capitalised on these associations to transmit “ideas of selflessness, approachability, and compassion”, which aided them in their community service and outreach work.17 The idea of the nun as a spiritual and authoritative figure lent weight to their serious messaging and attempt to position themselves as trustworthy and approachable, particularly in their work on safe-sex education and condom distribution and helping queer people to overcome feelings of sexual guilt and shame.

17However, by bringing the habit into the public realm of the “Market Place”, the London House destabilised the boundary between the sacred and the profane that religious dress serves to demarcate. This blurring of the distinction between contrasting spheres, coupled with the gender subversion inherent in their existence as “gay male nuns”, lent their activism a disruptive element. To see nuns in secular, political (on demonstrations), or sexually charged (in gay bars and fetish clubs) spaces disrupted people’s expectations and also contrasted the sisters to those in power, both in the Church of England and in the Conservative government.18 These were institutions criticised by the London House for affecting an appearance of holiness or respectability while doing little to help those who were less fortunate than themselves. Joining the front lines of protests against war or for safe sex, the London House pointed to the conspicuous absence of members of the Church in these arenas and highlighted government inaction on HIV/AIDS. Melissa Wilcox, writing on the American Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, has described this as “serious parody”: “a form of cultural protest in which a disempowered group parodies an oppressive cultural institution while simultaneously claiming for itself what it believes to be an equally good or superior enactment of one or more culturally respected aspects of that same institution”.19

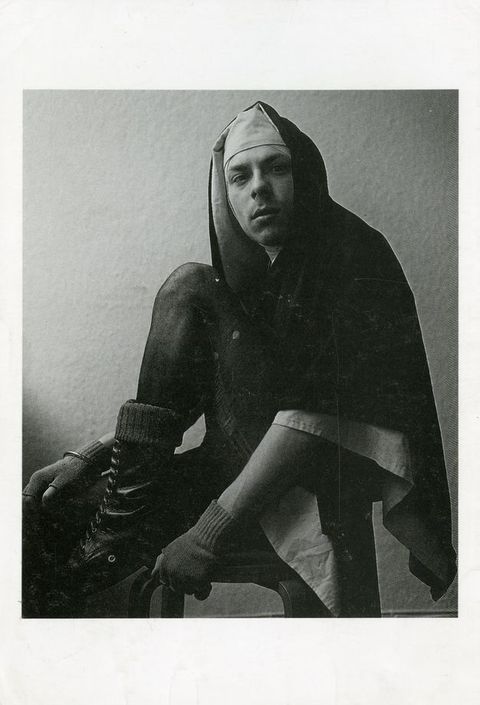

18For Sister Belladonna, one strength of public manifestation—appearing in public dressed as nuns—was that it was “an extraordinary vehicle for breaking through people’s pre-conceptions about what queers were like” that challenged “people’s brains”.20 This sense of disruption was furthered by its genderfuck elements, which broke down the hermetic barriers between “man” and “woman”.21 The nun’s habit contained an implicit critique of the rigid gender hierarchies found in both the Roman Catholic Church and the Church of England, the latter of which was at the time embroiled in its own bitter debates over the ordination of women, and challenged common-sense ideas of gender, sexuality, and religiosity.22 Photos such as Denis Doran’s portrait The Reverend Mother Suxcox (1993) reveal the genderfuck style adopted by the London House (figs. 5). Mother Suxcox is shown sitting on a stool, with one leg raised and his foot on the stool’s seat. Unlike the sisters of the American tradition, one of whom we saw in the photo by Wong-Geroux, Mother Suxcox’s face is unpainted beneath his bandeau and veil and shows the stubble round his mouth. His raised leg reveals ripped tights worn underneath his habit, drawing attention to the hair and musculature of his leg and a pair of leather boots. These aspects of a traditionally masculine presentation, taken together, are a contrast to the nun’s habit, an object of clothing worn exclusively by women in religious contexts.

20

Like members of the London House, Jean Fraser was involved in queer activism during the 1980s and 1990s, as a photojournalist, a member of activist groups, and part of a loosely formed coalition of London-based cultural producers who were critical of how HIV/AIDs, homosexuality, race, and gender were being represented in the art world and media. In 1986 Fraser had co-curated, with the photographer Sunil Gupta, the group exhibition Same Difference, which focused on the work of “photographers who openly identified as lesbian, gay or bisexual” and featured a teaching workshop designed for local schools. The workshop and the planned touring exhibition were both cancelled because of local authorities’ fears about the topic of sexuality provoked by the preamble to Section 28.23

23Fraser would later work with Tessa Boffin to develop the exhibition Stolen Glances: Lesbians Take Photographs, in which she also participated as an exhibiting artist, co-curator, and co-editor of the book of critical essays and artistic practice published under the same name. This collection, conceived by Fraser and Boffin ahead of curating the exhibition, is an artistic and theoretical text in its own right rather than a traditional exhibition catalogue, and has remained an influential and important work in the years since its publication. It was not enough, wrote Boffin and Fraser, that campaigns against Section 28 had increased the visibility of lesbians in the national media: They wanted art by lesbians to be visible too, not just in “isolated contexts” but “accessible to a wider audience of lesbians and the ‘independent’ photography sector”. Faced with a post-Section 28 cultural landscape in which the “promotion of homosexuality” was under attack, Fraser and Boffin argued that “promotion was exactly what we needed”.24

24As students of the Polytechnic of Central London, both Fraser and Boffin had been exposed to the theoretical frameworks of scholars such as Victor Burgin, Roberta McGrath, and Simon Watney on how representation “frames and organises political subjects”.25 While they aimed to promote photographic work by self-identified lesbians, Fraser and Boffin were equally keen to explore the politics of representation itself and to deconstruct terms such as “gay” and “lesbian” by exploring their historical and cultural origins. In the introduction to the book that accompanied the exhibition, they wrote about how they had prioritised photography that “concentrated on constructed, staged or self-consciously manipulated imagery”, as opposed to documentary-style photography or work that attempted to “naturalise” a “lesbian aesthetic”, so as to reveal the “socially constructed nature of sexuality”. This in turn allowed them to argue that “there is no natural sexuality at all” but instead a series of historically specific representations that have shaped and structured the political subject.26

25Fraser’s contribution to both the exhibition and the book drew on the figure of the “lesbian” nun to interrogate the social construction of the categories “woman”, “lesbian”, and “nun”. Her photographic sequence Celestial Bodies, as reproduced in the book, was composed of seven photographs featuring two young women dressed in seemingly authentic, full body-covering black-and-white habits and sensible black leather shoes. Iconographical detail, including visible brickwork, flowering white roses, and lush foliage suggest that the pair are in a convent garden. A narrative is suggested by the sequence of the photographs. In the first (untitled) image, the nuns are seen reading a book they hold between them. In the second, Transgression/Devotion, the nun on the left places her hand on her companion’s thigh, and in the third, Sublimination/Sanctity, the pair sit together holding hands and returning the viewer’s gaze (fig. 6). In the four later images, the nuns have acquired wine and fruit, as well as a nude female companion. Three of the final images show the nuns and their companion in varied compositions inspired by Manet’s Le déjeuner sur l’herbe, while the fourth shows one of the nuns relacing the other’s coif.

The images are irreverent and entertaining, displaying a light-hearted camp not dissimilar from the humour of the London House, and it is likely that some of those who saw the work would have been familiar with the group. Alongside her photographs, Fraser displayed quotations from diverse cultural references pointing to the complex and long-standing relationship between the nun and the lesbian, and queer sexuality more broadly. Among these is an excerpt from an interview with a founding member of the London House, Mother Ethel Dreads a Flashback:

27A car pulls up, Mother Ethel steps out—a vision in a black habit and wrinkled wimple, adorned with a collection of gay liberation badges, a silver whistle and a pair of nipple clamps. “Our mission” [he says] "is the promulgation of universal joy and the expiation of stigmatic guilt … the guilt attached to labels like “homosexual” … stigmatic guilt is something the Church … has used to keep people in line.27

“Kinky Vicar’s Gay Play Time”

Mother Ethel’s words, reproduced by Fraser on the gallery wall, speak to the idea of the Church of England, and the Christian faith more broadly, perpetuating harmful feelings of sexual guilt and shame. HIV/AIDS had reopened the wounds that the development of gay liberation politics since the 1970s had started to heal, reawakening feelings of guilt, shame, and stigma around homosexuality. In the words of Melissa Wilcox, “many gay and bisexual men felt a lifetime of cultural and religious guilt descend on them once again”.28 In the United Kingdom, the attitude of the Church of England, and frequent press coverage of its debates on homosexuality from 1987 onwards, deepened these feelings and reintroduced notions of sexual sin into public discourse.

28Gauging the impact of religion, and in particular Christianity, on life in Britain at the end of the 1980s is challenging. The prevailing understanding is of an increasing secularisation of society as the twentieth century progressed, with church attendance and self-professed Christian belief generally declining.29 Surveys have suggested that, by the end of the 1990s, religion was largely thought to be a private matter and that a majority of the population were against the idea of religious belief influencing public life, that is, politics, law, or government.30 Explicit appeals to religion by members of parliament were rare and, as Liza Filby has highlighted, unlike in the American context, “Christian Conservatism in Britain did not serve to galvanise the electorate”: Allegiance to political party was more likely to be predicated on issues of class and economics than on denominational affiliation or its lack.31

29However, as Filby continues, Christianity provided “an important philosophic undercurrent” to the Thatcher regime, providing the “tone and intellectual framing” for the government’s ideology.32 Graeme Smith has argued that, while “political scientists have all but ignored Thatcher’s Christianity”, her faith was central to her political programme.33 And, for Grace Davie, Christianity in 1980s Britain presented something of a paradox: Despite the supposed decline in religious institutions, the decade had seen a number of religious groups assuming a far greater public profile than “many thought possible a decade or so” earlier, with church leaders intervening in public debate and regularly appearing in the media.34 Despite a fall in church attendance across most Christian denominations, there was a distinct religious atmosphere in the 1980s, where religious thought, views, and beliefs were part of the backdrop of day-to-day life in the national press, on radio and television, and in the presence of street evangelism on urban high streets. The likes of the London House, Fraser, and other queer artists both felt and responded to this.35

32Looking back over the previous decade from the vantage point of 1990, the LGBT activist and religious studies scholar Martin Pendergast argued that Christian attitudes towards homosexuality and responses to HIV/AIDS covered a “wide spectrum of opinion and practice”.36 Lesbian and gay Christian groups had been involved in AIDS activism from the earliest years of the epidemic and had played a significant role in setting up telephone helplines, support groups, and interfaith groups.37 And, despite the portrayal of AIDS as the wrath of God by both British and American news media, British church leaders “one by one rejected any suggestion that AIDS was God’s punishment” and argued for compassion in dealing with people suffering from the virus.38

36Yet, as Pendergast wrote, the development of the New Right in British Christianity and the “move towards a British equivalent of the ‘moral majority’ in religious institutions and the political rhetoric of the period” produced a double standard towards homosexuality in these groups.39 While ostensibly preaching a message of compassion, some Christians remained—in their attitudes towards safe sex, condom use, and sexuality—committed to traditional Christian morality, including a rejection of promiscuous lifestyles and a return to “sexual expression only within marriage”, the latter option not being a possibility for lesbians and gay men at the time.40

39By 1987, the Church of England’s tentative progress towards building a consensus on homosexuality was undermined by a series of splits between its conservative and liberal members. In the General Synod of that year, the topic of homosexuality, particularly whether the Anglican Church should allow openly gay men to be clergy, was hotly debated.41 The Daily Telegraph reported how the then Archbishop of Canterbury, Robert Runcie, “called for compassion and understanding, particularly towards homosexuals who were attempting to form stable relationships” while continuing to dismiss the view that such relationships were of the same value as Christian marriage. Runcie was quoted as stating that, in considering homosexuality, “we must unashamedly proclaim biblical beliefs and morals”, that the Bible considers sexual acts between people of the same gender to be a sin. Compassion, it would seem, had it limits within the Church. Following a series of highly charged debates, the Synod passed a motion that included a statement that “homosexual genital acts fall short” of God’s ideal.42 However, the synod did not include a much publicised motion to expel all known gay members of the clergy from their parishes. Two years later, the Church suppressed the publication of the Osborne Report, commissioned in 1986, which encouraged a liberal change in attitudes towards homosexuality, and continued to engage in vitriolic debate on the subject for years to come.43

41This led Walter Ellis, writing in the Sunday Telegraph, to portray the Church of England as being in the grip of a shadowy “homosexual lobby” and to tout the promised return to scriptural purity on matters of sex and morality that the growth of evangelicalism seemed to promise.44 Other papers amplified the voices of homophobic members of the faith under the guise of encouraging public debate. The Reverend John Weeks stated that the topic of homosexuality “appals me. It is contrary to the creative order of things”, while the Star reported that the “hypocrisy of the Church of England” on homosexuality “threatened the very foundation of the Church”.45

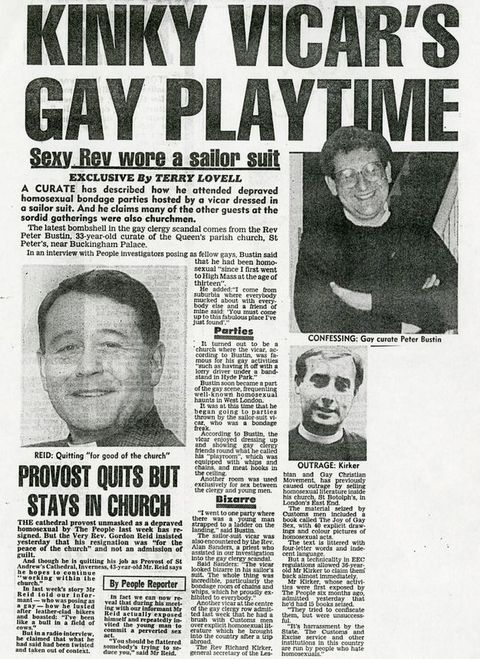

44Articles such as these were accompanied by a tabloid witch-hunt pursuing homosexual clergy, a number of whom were outed by sting operations in which journalists posed as fellow homosexual Christians. The resulting stories, describing the personal lives of their targets in lurid detail, were salacious and deeply homophobic, with examples such as “Kinky Vicar’s Gay Playtime” (in the People) and “Evil Fantasies of Kinky Canon” (in the News of the World) both leading to the public disgrace of their victims (fig. 7).46 These articles repeated similar messages of “sin” and “evil”, as well as alleging that the Anglican Church was being controlled by the threatening spectre of a “gay mafia”.47

46

The Church of England’s attempts to find a middle ground that might appease both its liberal and conservative wings was doomed to failure and left the public with an impression of a church that was homophobic but, paradoxically, full of gay people. In the years following 1987, the church and many of its members responded to media pressure with a toughened stance on homosexuality. Archbishop Runcie was succeeded by Archbishop George Carey, a conservative evangelical who proved to be an advocate for conservative sexual morality and an opponent of liberalisation.48

48Groups such as the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence and Outrage! saw the Church of England as condoning homophobia by not challenging it, as promoting an out-of-date sexual morality that had little modern relevance, and as actively responsible for HIV/AIDS deaths by its discouragement of safe-sex education.49 The Church was also seen as hypocritical because of the perceived presence of many gay men in its ranks and as promulgating a harmful association between sexuality and sin. The queer nun can be considered a response to this religious environment.

49The London House of the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence used the nun, a symbol for some of the most self-denying and conservative strands of Christian belief, and inverted it, transforming it into a symbol of sex positivity, self-acceptance, and queer resistance. Gender blurring was central to this performance, serving as a way to communicate an inversion of hierarchy. As Sister Dominatrice des Hommes of the London House put it on national television: “because the church always pushes us down … as gay men, as lesbians, we say why not turn it around? It’s all about a role reversal. Why not let the men be nuns … and let the women be popes?”50 The reversal of the roles of man and woman, and of straight and gay, signalled a reversal of society’s power dynamics (fig. 8).

50For the scholar of religious dress William Keenan, “carnival time” is when the public, secular space of the street plays host to a cavalcade of “popes, cardinals, bishops, abbots … nuns and sisters in every cut and colour of religious dress”. The performative inversion of the London House can be understood as a tactic of carnivalisation, of bringing religious costume into secular and profane settings to upturn and undermine supposedly “natural and normative orders”.51

51In its attempts to establish a consensus on homosexuality, the Church of England assumed the authority to speak about and on behalf of “the homosexual”, who was framed as a problem to be fixed. Notably, the Osborne Report, the only study commissioned by the Church that actively sought to include the experiences and opinions of lesbian and gay Christians, was suppressed. The Church employed its superior hierarchical position (as “sacred”) in relation to the homosexual individual’s “profane” to impart authority to its moral pronouncements. More broadly, for centuries Christian groups have claimed tradition, authority, and divine guidance to pronounce judgments of sin and guilt. This stigma, or in their words “stigmatic guilt”, was precisely what the London House aimed to challenge and “expiate”.52

52Adopting the habit as their chosen dress, and claiming to be nuns, so as to spread a political message of radical self-acceptance was more than an eye-catching shock tactic. In doing so, the London House managed to call into doubt the authority of the Church of England and its moral pronouncements. There was the inevitable contrast, which must have caused discomfort to members of the Church, between a group of gay men who dressed in religious clothing, spoke about gay sex, and preached a message of love and acceptance, and the public’s perception of the Church as a group of closeted gay men who dressed in religious clothing and were equally fixated on gay sex but preached a message of exclusion and sin.

“Isn’t That Joke a Bit Hackneyed by Now?”

The visitors book of the Edinburgh exhibition of Stolen Glances, kept by Tessa Boffin and now preserved in her archive, contains responses left by the public to Fraser’s Celestial Bodies. While many people were positively disposed towards the work, some found her use of the nun problematic. “Disappointing to see lesbianism and religion together”, wrote one visitor, who went on to frame Fraser’s use of religious imagery as an “attack”. “Too many nuns”, wrote another: “isn’t that joke a bit hackneyed by now?”53

53“Hackneyed” jokes at the expense of nuns have long been an element of English culture. Reformation satires concerned with constructing the Catholic other, against which the behaviours of the Protestant citizen could be measured, presented the nun as “more or less whorish”, and jokes referring to convents as brothels and brothels as convents can be found dating back to at least the 1550s.54 A stock comedic character in British literary works throughout the post-Reformation period, the nun stood for “all women and all Catholics”, satirising the excessive, misguided, and perverse behaviours of both.55 Temporally, as part of a pre-Reformation religious landscape, and geographically, as a continental phenomenon, othered, or “inevitably elsewhere”, the convent became a site that allowed “male writers not only to give voice to anxieties about female sexuality, but also to use the disturbing nature of that sexuality as a vehicle for articulating other kinds of anxieties” about religion, gender, and nationhood.56

54These tropes intensified and diversified in the mid-nineteenth century, when the nun became a figure simultaneously of anxiety and of fascination. Catholic Emancipation and the re-establishment of the Catholic hierarchy in 1850 had led to an unprecedented number of new convents on British shores, and it was estimated that by 1873 there were “some 3,000 Roman Catholic nuns living in 235 convents in England and Wales”.57 To this figure can be added a number of Anglican sisterhoods, who were routinely mocked in periodicals such as Punch as being more concerned with fashion than with faith and for taking their vows of celibacy “rather lightly”.58 As the century drew on, the figure of the nun came to serve as a sign and symptom of concerns not only about religion but also about the erosion of gender boundaries, the proper place of women in society, and fears of the spinster and other “redundant single women”.59 Nuns were the target of satirical prints, sensational novels, and an ensuing spate of polemics, religious tracts, and pornography detailing their supposedly “libidinous and corrupt lives”.60

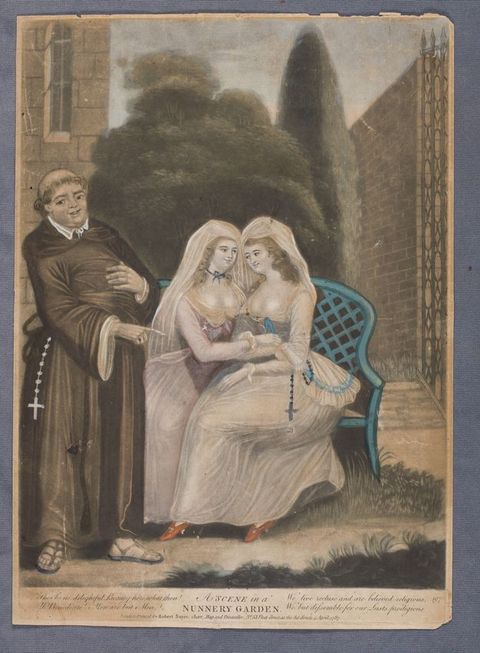

57A principal element of the nun “joke” was the charge that nuns, while ostensibly claiming chastity and poverty, actually indulged in all manner of luxurious and risqué behaviour. We can sense the transhistorical echoes of this joke in the erotic, latex-clad nun of Skin Two, the camp humour of the London House, and the suggestive and indulgent behaviour of the nuns and their female companion in Celestial Bodies. The eighteenth-century print A Scene in a Nunnery Garden (1787) illustrates this trope (fig. 9). The print shows a nunnery garden, hidden from the outside world by high walls, as the scene for an erotic embrace between two nuns, overseen by a portly friar, who directs our gaze towards the women with a pointing finger. The two nuns sit on a loveseat, their fine dresses accentuating their breasts and the contours of their bodies, and their red shoes calling to mind the rich red vestments of Catholic cardinals, the colour of luxury, and the scarlet of prostitution and the devil.61 The hand of one nun circles the waist of her companion, who in turn looks down at the other’s decolletage. Beneath the image appear the words: “The Scene delightful, Beauty here, what then! Ah! Benedicite! Men are but Men. We live recluse and are believed religious, We but dissemble for our Lusts prodigious”.

61

Satires such as this had various uses, drawing attention to Catholic hypocrisy, implying that the profligate lives of Catholic religious were funded by the common person, and contrasting the moral values of Protestants and their licentious Catholic counterparts. Notably, in its critique the print constructs the convent as a sapphic space: The male friar appears to be of no interest to the women, who are lost in each other’s presence, their “Lusts prodigious” appearing more directed towards their own sex.

In Celestial Bodies, Fraser places her nuns within a “nunnery garden” of their own, emphasised by the brickwork suggesting the impermeable walls of the convent and by the garden foliage surrounding them. The tightly cropped photographs add to the sense that they are enclosed in a private space. In Transgression/Devotion, the brickwork of the convent wall is clearly visible behind the pair, and Fraser has included in the scene a flowering white rose bush—a symbol of purity, innocence, and the Virgin Mary (fig. 10). One nun has placed her hand on her companion’s thigh as she looks expectantly into her face. The second nun gazes fixedly at the book held between them. The gesture, while suggesting sexuality, is relatively innocent, but the idea that convents are a home for the “sapphically inclined” encourages the viewer to read more into the scene than the gesture alone might suggest and to fill in the gaps with their own convent fantasies.62

62

The world within the convent walls, seen as a hothouse of erotic potential, inspired much nineteenth-century art. The nun existed as a figure that was at once pious and sentimental and associated with moral panics, prurient exposés of convent life, and even pornography. Fine art works portraying nuns reflected some of this voyeuristic fascination. Alexander Johnston’s The Novice, which is known today only by an engraving of the original oil painting (fig. 11), shows an elegant young woman in a bare Gothic stone cell, in the process of removing her fine jewellery. The white robe of a novice lies at her feet and a leering skull sits on a rosary on the windowsill to her right. The image speaks to religious concepts: The renunciation of luxury and vanity for a chaste spiritual life is connoted by the removal of jewellery, while the rejection of worldly mortality in pursuit of heavenly eternity is shown by the skull and the rosary. But, as Dominic Janes has noted, “skulls and crucifixes powerfully suggested sexual transgression” for the Protestant viewing public and, alongside the loose hair of the young woman, impart an erotic charge to the image.63

63

Elements such the convent wall, the enclosed garden, and various “metonyms for the sexual act”—such as keys, gates, and the crossing of material boundaries—were used in the pornography of the era to symbolise “the transgression into a woman’s body”.64 Those viewing Johnston’s work are placed in the position of having penetrated the bounds of the convent to watch a religious striptease of sorts. In the moment captured within the frame, the novice is seen taking off her bracelet, and the logic of the picture may encourage the viewer to imagine her eventual disrobing before she covers her naked body with the novitiate’s white habit.

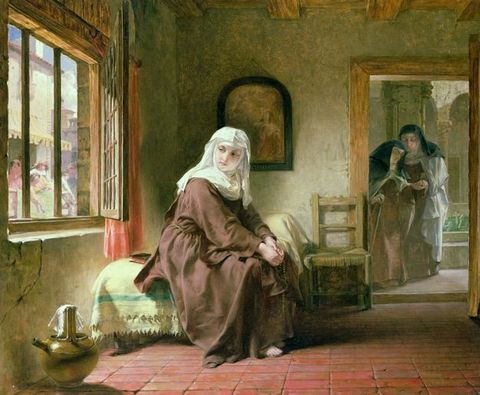

64A later painting of the same name, Alfred Elmore’s The Novice (1852), shows a pretty young novice seated on her bed in a cell with a rustic terracotta floor, located in a possibly European Catholic elsewhere (fig. 12). In her hands she holds rosary beads but, distracted from her prayers, she turns her face towards the sunlit carnivalesque scene outside the window. To her left a gothic cloister can be seen in shadow, from which two black-veiled nuns approach, an infirm elderly nun supported by a younger one. Behind them are a number of small white crosses embedded in the grass, perhaps the graves of nuns who have died within the confines of the religious life.

Critics condemned the image for its “unnaturalness”, a common response at the time to many depictions of nuns. As Susan P. Casteras has argued, many nineteenth-century English viewers saw the convent as a place of living death, of unnatural celibacy, sterility, and mortification.65 Elmore’s image plays on these connotations, presenting a clear contrast between the vitality of the sunlit world and the cloister “where old age, infirmity and the grave awaits”.66 The work of both artists contain elements of the mid-nineteenth-century fascination with the convent as a space into which young women were seduced and perverted away from their natural inclination towards the pleasures of heterosexual romance, marriage, and childbearing.

65If we can consider the “convent” to be a “grave” during this period, it was, as Ariel Kline has written, a “sexy one” and one with a distinctly queer charge.67 The figure of the lesbian, the idea of the spectral, and otherworldly fantasy circulated as part of what Francesco Ventrella has described as a nineteenth-century “web of signifiers”, which bound together a host of “supernatural figures with a troubled relationship” to gender and sexuality—“a sybil, a ghost and a vampire”.68

67The nun, particularly as represented in art and visual culture, provides a counter to what Terry Castle has termed “the no-lesbians-before-1900 myth”: a prefiguration of the modern sexual category.69 Nineteenth-century representations of the nun built on pre-existing understandings of the convent as a sapphic space and combined these with an aura of sexual threat. In Elmore’s painting the older nuns in the gloom of the cloister emerge from the shadow as depraved vampiric figures, surrounded by the evidence of their previous victims whom they had seduced into abandoning the outside world for the homosocial, queer world of the cloister.

69Fraser’s work taps into this legacy. While her images are relatively chaste in what they show, they are also seductive and sexual. The light touch, clasped hands, and knowing glances of her figures, particularly in the first three images in the sequence, are exaggerated by the cultural framework viewers bring to the picture, particularly those who are familiar with representations of nuns in British popular and visual culture, or for lesbian audiences, who are alert to the legacy of stereotyping and accustomed to performing queer readings of ostensibly heteronormative cultural artifacts.

Celestial Bodies also relies on viewers bringing with them at least partial knowledge that this is a construct—a “hackneyed” joke. For the images to make sense, the viewer has to understand convents as a sapphic space. Yet Stolen Glances is keen to draw our attention to the workings of this joke and does so to remind us that it is a fiction, a construct, and a product of representation—a “discursive reality” rather than an essential or objective fact.70

70In Fraser’s images a number of visual elements create a sense of authenticity, including the seemingly authentic habits and sensible shoes worn by her protagonists and their location in a walled convent garden. Fraser included with the photographs a series of textual excerpts from diverse sources including Diderot’s anticlerical writings in The Nun (1792, English translation 1797), testimony from the 1623 trial of the now infamous “lesbian” nun Sister Benedetta Carlini, and dialogue from Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s film Black Narcissus (1947), together with contemporary sources including Cherry Smyth’s erotic writing on the habit as an object of sexual pleasure, memoirs of lesbian ex-nuns including Rosemary Keefe Curb, and an interview with Mother Ethel Dreads a Flashback of the London House of the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence.71

71By highlighting the social construction of the nun as symbol, Fraser was able to comment on how “the lesbian” has been the product of similar processes. Her inclusion of the writings of Diderot, for example, point the viewer towards a tale, written by a male author, in which a young woman is forced into a convent against her will. Here she suffers all manner of indignity and humiliation, much of it sexual, at the hands of corrupt nuns: The mother superior “sends for her, treats her harshly, orders her to undress and give herself twenty strokes with the scourge”. This draws a connection between how the nun and the lesbian have often served as the same cautionary character against whom innocent young women needed to be protected.72 In Black Narcissus, a small group of nuns travel to India to establish a new convent, but their attempts are doomed to failure because of mounting erotic and emotional tensions and neuroses. While the nuns are ostensibly heterosexual, the film serves as an example of how nuns, like lesbians, have been portrayed, as “lonely” yet “fearful of men”, “tormented” by “warped passions”, “savage”, and “incorrigible” because they “desire the forbidden”.73

72Fraser also included excerpts from two non-fiction works that had gained some notoriety in the years prior to Stolen Glances, and that might have been familiar to some members of her audience, particularly regular readers of lesbian and feminist publications. That this was an audience courted by Boffin and Fraser is suggested by their decision to publish the introduction to the Stolen Glances book in journals such as Feminist Review and Feminist Studies. This served to both publicise the touring exhibition and provide potential visitors with a theoretical framework through which to approach the exhibition in advance.74

74The life of the seventeenth-century “lesbian” nun and fraudulent mystic Sister Benedetta Carlini had recently been published by Judith Brown to some fanfare.75 Brown’s book, based on documents she discovered in the state archives of Florence, contained a “detailed description of [Carlini’s] sexual relations with another nun”. For Brown, this made the document “invaluable for analyzing … women’s sexual lives as well as Renaissance views of female sexuality”.76 Brown’s book not only showed how lesbians and nuns were represented by patriarchal systems—in this case in documents produced by male investigators on behalf of the Catholic Church—but also brought the nun and the lesbian together in the scholarly record, highlighting the convent as a key location for lesbian history.

75Fraser also quotes from Lesbian Nuns: Breaking Silence, a collection of memoirs of convent life written by fifty-one self-identified lesbian women who had lived or, in a handful of cases, continued to live as Roman Catholic nuns.77 In the introduction to the collection, Keefe Curb, herself a lesbian ex-nun, made a connection between nuns and lesbians that seemingly spoke to the concerns of Fraser’s work:

7778if our culture defines normality in terms of male experience and values only women who relate to men, both nuns and Lesbians tend to be ridiculed or dismissed as irrelevant to the strides of history … a male defined culture which moralizes about “sins of the flesh” … sees both nuns and Lesbians as “unnatural”.78

On its original publication by the lesbian publishing company Naiad Press, the book had received “unprecedented” international attention.79 Barbara Grier, a co-founder of Naiad, seeing its potential to both raise the company’s profile and secure its financial stability, launched a publicity campaign that reached far beyond the confines of the lesbian and gay reading community, netting more than “80 television appearances and radio interviews” in the United States alone.80 While the text of the book was serious, emotional, and by no means sexually explicit, the campaign played on the sensational suggestive frisson arising from the pairing of lesbians and nuns. As one reviewer wrote, “the apparently oxymoronic term ‘lesbian nun’ easily tickles the curiosity of lovers of naughtiness, prurience, and the shocking … and guarantees the sale of a certain number of books”.81 Naiad Press would go on to sell excerpts of the book to the soft-core pornographic magazine Forum, against the wishes of the co-editors and contributors, which led to numerous debates in lesbian, gay, and feminist publications in the years that followed.82

79The texts that accompany Fraser’s images, taken together, point to the continued existence of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century tropes linking the nun to sexual deviance, unnaturalness, and neurotic or hysteric emotionality. At the same time, Fraser deployed these references to draw the viewer’s attention to how historic representations of the nun mirror those of the lesbian as a shadowy, perverse, and disordered figure. By placing her visual images alongside the textual excerpts, she argued that the “social, historical, and existential ‘reality’” of both the nun and the lesbian is a “discursive reality”.83 As viewers, we are challenged to locate the “real”, the “original” text that shapes what the nun is, and to question where our pre-existing knowledge of the nun comes from, but we are ultimately frustrated. In place of a unique stable original, Fraser offers a seemingly endless process of representation, subverting the idea that there is an “original” text at all.

83A Picnic in a Convent Garden

In the photograph Blasphemy/Communion (fig. 13), Fraser quotes directly from Manet’s Le déjeuner sur l’herbe (fig. 14). The similarities in the models’ poses, the conjunction of a female nude with two clothed figures, and the use of a wicker basket overflowing with fruits signal her close quotation of the original painting. At first glance, Manet’s painting may be a strange location to find nuns. Yet, for Fraser’s audience, the association of the painting with sex and scandal would have been fresh as it had been the subject of controversy in the British press ten years earlier following Malcolm McLaren’s quotation of the painting for an album cover for the pop group Bow Wow Wow. The album cover, which featured the then fifteen-year-old lead singer Annabella Lwin as the nude figure in the composition, had been the subject of a high-profile obscenity case on its release (fig. 15).84

84

From Le déjeuner, Fraser produced three images. Blasphemy/Communion recreates Manet’s painting most faithfully, while the other two play with it, making subtle changes to the composition and the attitudes of the principal characters. In Profanity/Reverence the nuns’ nude companion lies in front of them with her back to the viewer. She looks up towards the sky, while the nuns look with interest down at her exposed body. In Sacrilege/Absolution she props herself up on her elbow to read a book, while the two nuns look out of the frame, returning the viewer’s gaze. These images, as laid out in the Stolen Glances book, are interrupted by the photo Revelation/Chastity, in which the nude woman is not present; instead, the image shows one of the nuns relacing her companion’s coif (fig. 16).

These images could be read as juxtaposing the nuns against their sexually liberated companion. Despite their connotations of sex and licentiousness, nuns, with their vows of chastity and habits covering the full body, remain a symbolic shorthand for the more sex-denying elements of the Christian faith, particularly at the time of the work’s exhibition, when conservative Christian morality was increasingly a feature of public discourse on sex. If Celestial Bodies is read in such a light, it can be interpreted as a narrative of sexual political awakening, in which the pair of nuns, first seen reading chastely in the garden together, grow in awareness of their sexual feelings for each other, before achieving sexual and political liberation through contact with the nude, here seen as an allegory of lesbian sexual knowledge and freedom.

However, this narrative is complicated by the inclusion of Revelation/Chastity between the scenes with the nude. Fraser also made this choice in displaying the images on the gallery wall. Faced with their nude companion, the nuns in Celestial Bodies relace themselves into their coifs rather than taking off their religious habit to join her, resisting a narrative that would cast them as sexually repressed representatives of an outmoded traditional morality. Celestial Bodies readily explores the nun as a figure of sexual capacity, one that is linked to lesbianism and sexuality. Furthermore, as the more contemporary quotes referenced by Celestial Bodies show, Fraser was keenly aware of the radical queer potential of the nun, particularly in regard to the activism of the London House of the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, who could hardly be considered as nuns in the sexually repressed mould.

The nude figure who appears alongside the nun in the Le déjeuner images was modelled by the author and poet Cherry Smyth, whose work Fraser quotes to accompany her images. Smyth’s writing presents a scene in which the protagonist dresses in a nun’s habit gifted to her by a lover: “The wimple pulls tightly across my forehead. The constraint gives me pleasure, makes me graceful. … I wonder if you are as wet as I am, and if, later you will make me sit down on the edge of our bed, lift the layers, and lick my inner thighs”.85

85Smyth’s words frame the habit as an object of pleasure rather than of repression, one that is freely given and worn. For the London House too the habit was an object that they wore to spread a message of sexual freedom, freedom from guilt, and that they customised to emphasise these aims, as shown in the description of Mother Ethel as “a vision in a black habit and wrinkled wimple, adorned with a collection of gay liberation badges, a silver whistle and a pair of nipple clamps”, or in the combination of wimple, ripped tights, and leather boots worn by the Reverend Mother Suxcox in Denis Doran’s image discussed in this article.86

86Throughout the sequence Fraser’s nuns move between the ambiguous, and at times paradoxical, significations carried by the nun in the British cultural imagination. Nuns are known to be chaste and virginal, yet Fraser’s work draws on the idea of their licentiousness. The habit is a symbol of chastity but also exists simultaneously as a fetish object. The nun herself exists as an object of heterosexual fantasy, but this relies in large part on the idea that she is a lesbian. It becomes yet another fantasy that lesbians can reappropriate to their own ends.

By frustrating attempts to locate a straightforward sexual liberation narrative, Fraser may well have been commenting on the perceived weaknesses of the sort of lesbian and gay liberation politics that had characterised the period prior to her own. As the activists interviewed by Ian Lucas in his oral history of Outrage! noted, by the time Fraser was making Celestial Bodies, there was a feeling among many out, politically active queer people that “the legacy of lesbian and gay campaigns since 1970 had not led to any significant improvement for lesbians or gay men … in fact, people were beginning to realise that things had actually become a lot worse”.87 For Fraser and the London House, merely adopting “lesbian” or “gay” as positive terms was no longer enough. Fraser and Boffin had reflected on this in the introduction to Stolen Glances, noting that such a strategy “attempted to replace one myth with another—a simultaneous normalisation and idealisation” that ignored the origin of these identifying categories and their function as part of systems of “investigation, surveillance and control”.88

87Instead, by drawing on the history of the nun’s cultural construction and highlighting her paradoxical connotations, Fraser and the London House examined how sexual identity categories are themselves the product of multiple processes of at times problematic representation. In doing so, they did not argue for such categories and identities to be discarded entirely. What Celestial Bodies and the London House seem to suggest is that categories such as “nun”, “woman”, “gay”, and “lesbian” can be sources of pleasure and empowerment but only if we acknowledge their socially constructed nature and make an informed consensual choice to adopt the said categories. If the habit can be put on and taken off for reasons of sexual pleasure or political pressure, perhaps so too can our rigid sexual and gender categories.

Conclusion

Unlike the impact and legacy of Section 28 on queer culture, the influence of the religious ethos of the United Kingdom at the end of the 1980s on the arts and visual culture has yet to be fully studied. The work of Fraser and the activism of the London House show how religious symbolism—in this case the potent signifier of the nun’s habit—has the capacity to be appropriated to queer political ends. The London House adopted the figure of the nun to create a joyful carnivalesque that was counter to what they identified as “stigmatic guilt”, the result of “centuries of systematic scapegoating of gay people” designed to support oppressive and hierarchical social structures of inequality.89 By transgressing the boundaries between male and female, sacred and profane, the London House called the supposedly natural or common-sense division of these realms into question, and by doing so undermined the authority of those in power, such as the Church of England hierarchy, to speak on behalf of queer people. For Fraser, the habit allowed for the deconstruction of categories of “woman”, “lesbian”, and “the nun” herself, illuminating the processes of representation by which these, and by extension all, political subjects can, it is argued, be formed. By combining her photographs with text, Fraser was able to point to the similarities between how the nun and the lesbian have been represented across time and to argue for the potential power of these categories when they are reappropriated for political and pleasurable ends.

89For these interventions to be successful, Fraser and the London House relied on the position of the nun as a complex and at times paradoxical figure in the British cultural imagination. Nuns are at once chaste and sexual, authoritative and comedic, and these connotations can be considered to have undergone significant naturalisation, appearing to have “always been there”, “time-free” and pre-existing—as I discussed in the introduction, the sexy or naughty nun, with her connection to licentiousness and deviance, seemingly needed little by way of introduction or explanation at the end of the 1980s, and the same can be said of today.90 By tracing this history back from the late twentieth century to the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, we can better understand the origins of this paradoxical image. This allows us to consider the influence that religious imagery might have had on the development of the modern sexual subject and, at the same time, contends for a sense of queer ownership over these same religious symbols in the present.

90The work of Fraser and the London House have a place in a history of queer art and visual culture in Britain. Their work can be seen as responding to a certain conjuncture of cultural and religious forces present at the end of the 1980s. I argue that their work, and work similar to it by other queer artists and activists working with religious symbolism in Britain during this period, also need to be recognised as part of an archive of British religiosity, as engaging in visual forms of debate about the meaning and significance of religious symbols, their origins, and their continuing importance.

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge my PhD supervisors Dr Francesco Ventrella and Dr Meaghan Clarke for their hard work and support over four years. I would also like to thank Jean Fraser for her engagement with this research and for her thoughtful and considered feedback. My thanks to the archival team at Bishopsgate Institute, London, for their assistance and advice throughout the collection and cataloguing of the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence Archive. I would also like to thank the members of the London House of the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence and the order’s queer saints who have been so generous with their time and support.

About the author

-

Thomas Elliott holds a doctorate in art history from the University of Sussex, where he focused on the use of Christian symbolism by queer artists at the end of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. He was funded by the Consortium for the Humanities & the Arts South-East England Doctoral Training Partnership (CHASE DTP), and his research interests include Christianity, sexuality, fin de siècle decadence, and the legacy of the long 1980s in Britain and the United States. At the Association for Art History’s annual conferences in 2023 and 2024 he presented work on, respectively, queer medievalisms in the work of the London House of the Sisters of Indulgence and queer representations of Christ in the work of Elisabeth Ohlson Wallin. He was a speaker at the Queer Medievalism workshop and conference at Oxford University in the summer of 2022. In 2023 he worked with founding members of the London House to collect and catalogue material relating to the early years of the group. The collection, the first archive of the Sisters in the United Kingdom, has recently been made available to the public at the Bishopsgate Institute, London, and was made possible by the CHASE DTP doctoral placements scheme. In his spare time, he is part of the creative team behind the Brighton-based club night “Gender Trouble” and the queer religious DIY fashion event “The Church of Italo”, and is an active member of the life model and artists collective Artists/Models/Ink.

Footnotes

-

1

Tony Mitchell, “Nifty Fifty!”, Skin Two 50 (Winter 2004–5): 54. BDSM is an umbrella term for a number of related erotic relationships between consenting adults, including bondage, discipline, dominance and submission, sadism, and masochism. ↩︎

-

2

Pat Califia, “The Power Exchange”, Skin Two 6 (1986): 5. For an overview of the range of topics explored in Skin Two across the years, see Mitchell, “Nifty Fifty!”. ↩︎

-

3

Information on the production schedule of the magazine and the promotional purposes was obtained through email correspondence with the ex-editor of Skin Two, Tony Mitchell. ↩︎

-

4

Some notes on terminology: The Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence are an international activist movement, with groups based in cities across Europe, Australia, and the Americas. Local groups tend to refer to themselves as chapters or houses, as in “the London House” or “the Sydney House”. In some cases, “chapter” or “house” is used interchangeably by the same group. For clarity, I shall use the term the “sisters” to refer to the wider organisation and “house” when referring to a specific local group. The London House primarily referred to themselves as “gay male nuns” in their own material and in interviews. They took the pronouns “he” and “him” when “manifesting” as nuns (the term used by the Sisters for appearing in public dressed in habit), in large part for the genderfuck contrast it lent their performance. However, there were also female and trans members of the London House. Many houses today use more inclusive descriptors, but I preserve it here when talking about the London House, except where individual sisters have expressed a preference for an alternative descriptor. For a wider discussion of gender, labelling, and contemporary debates on these issues in the international order, see Melissa Wilcox, Queer Nuns: Religion Activism and Serious Parody (New York: New York University Press, 2018). ↩︎

-

5

Little evidence remains of how the exhibition Stolen Glances and Fraser’s Celestial Bodies appeared in the galleries that hosted them. Slides preserved in the Tessa Boffin Archive at the University of the Creative Arts show that Fraser exhibited five photographs when Stolen Glances visited the Cambridge Darkroom in 1991. The exhibition was accompanied by a book featuring the photographs and a collection of essays, in which Fraser included seven photographs: Tessa Boffin and Jean Fraser, eds., Stolen Glances: Lesbians Take Photographs (London: Pandora, 1991). Most of this article is based on the photographs that appear in this book. ↩︎

-

6

The Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence take on sister names when joining the order. A number of them have also published work under their “secular” names. I use sister names throughout unless the sister in question has publicly used their secular name to write or talk about the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence. ↩︎

-

7

The story behind the kiss-in and its subsequent impact is told through interviews with organisers and attendees in Ian Lucas, Outrage! An Oral History (London: Cassell, 1998), 31–37. ↩︎

-

8

Paul Burston, “Entertaining Mother Ethel”, Capital Gay, 17 August 1990. ↩︎

-

9

The group was well enough established to be a central feature at a queer Christmas event in Covent Garden later that year, leading a public carol service (Lucas, Outrage!, 32–47). ↩︎

-

10

Scholarship on the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence was, until recently, limited but this has started to change. For the London House and their use of Polari, see Paul Baker, Fabulosa: The Story of Polari, Britain’s Secret Gay Language (London: Reaktion Books, 2019). For their work with Derek Jarman, see Peter Tatchell, “Outrage! Direct Action & Queer Revolution”, in Derek Jarman: Protest!, ed. Seán Kissane and Karim Rehamni-White (London: Thames & Hudson, 2020), 202–5. For the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence outside London, see Chris Greenough and Nina Kane, “‘Blessed Is the Fruit’: Drag Performance, Birthing and Religious Identity”, in Contemporary Drag Practices and Performers: Drag in a Changing Scene, ed. Mark Edward and Stephen Farrier (London: Bloomsbury, 2020), 188–205, and Nina Kane, “Guimpe-ing It Up for the Archive: Vestiary Politics and the UK Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence”, in The Routledge Companion to Drag, ed. Mark Edward, Stephen Farrier, and Garjan Sterk (London: Routledge, forthcoming). On the Sisters in the United States, see Wilcox, Queer Nuns, and for work on the Australian sisters, see Miles Pattenden and Michael Barbezat, “Ave, Ave, Ave Mardi Gras: The Queer Medievalism of Sydney’s Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence”, conference paper presented at Queer Medievalisms Workshop, Oxford University, July 2023. ↩︎

-

11

Countdown on Spanner was an organisation dedicated to demanding “the recognition that sadomasochism is a valid, sensual and legitimate part of human sexuality”, formed in response to the R v Brown judgment of the House of Lords, which wrote into UK law that “consent was not a valid legal defence for actual bodily harm”, effectively criminalising S&M acts between consenting adults; the ruling remains in effect today (Countdown on Spanner Archive, 1984–98, catalogued by Barbara Vesey, Bishopsgate Institute, London). ↩︎

-

12

Wilcox, Queer Nuns, 42. ↩︎

-

13

Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, “Who Are the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence”, publicity flyer, circa 1991, SOPI/BEL/6/1, Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence Archive, Bishopsgate Institute, London. ↩︎

-

14

Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, “Who Are the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence”. ↩︎

-

15

Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, “Who Are the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence”. ↩︎

-

16

Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, “Who Are They?”, 1992, SOPI/BEL/6/1, Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence Archive, Bishopsgate Institute, London. ↩︎

-

17

William Keenan, “From Friars to Fornicators: The Eroticization of Sacred Dress”, Fashion Theory: The Journal of Dress, Body and Culture 3, no. 4 (1999): 391; Wilcox, Queer Nuns, 2. ↩︎

-

18

Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, “Who Are They?” ↩︎

-

19

Wilcox, Queer Nuns, 70. ↩︎

-

20

Mark A. Spencer (aka Sister Belladonna in Gloire de Marengo) interviewed by Paul Baker, “The Story behind the Book Cover: An Interview with Sister Belladonna”, Fabulosa! The Story of Polari, Britain’s Secret Gay Language, 20 July 2019, http://wp.lancs.ac.uk/fabulosa/2019/07/20/198. ↩︎

-

21

David Bergman has traced the origins of the term “genderfuck” to a 1974 article by Christopher Lonc in the magazine Gay Sunshine, in which the author uses the term to argue for the strength of politicised drag performance as a tool for destabilising and undermining sexual and gender roles. By the early 1990s, the term had become popular among queer activists and theorists as a form of counter-identity politics that deployed performative and politically and sexual charged inversions of gender and sexual tropes in calling attention to the socially constructed nature of categories such as male/female and straight/gay. See David Bergman, Camp Grounds: Style and Homosexuality (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1993), 7; Susie Bright, “Toys for Us”, On Our Backs, Fifth Anniversary Issue (October–November 1989): 8–9; and June L. Reich, “Genderfuck: The Law of the Dildo”, Discourse 15, no. 1 (1992): 112–27. ↩︎

-

22

Sean Gill, Women and the Church of England: From the Eighteenth Century to the Present (London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 1994), 257–59; Ian Jones, “Earrings Behind the Altar? Anglican Expectations of the Ordination of Women as Priests”, Dutch Review of Church History 83 (2003): 462–76. ↩︎

-

23

Sunil Gupta, “Same Difference”, undated, https://www.sunilgupta.net/same-difference.html. ↩︎

-

24

Tessa Boffin and Jean Fraser, “Introduction”, in Stolen Glances: Lesbians Take Photographs, ed. Tessa Boffin and Jean Fraser (London: Pandora, 1991), 9. ↩︎

-

25

Laura Guy, “Backwards Glances at Lesbian Photography”, Photoworks 24 (2017), https://radar.gsa.ac.uk/5635/. ↩︎

-

26

Boffin and Fraser, “Introduction”, 9–10. ↩︎

-

27

Mother Ethel Dreads a Flashback OPI interviewed in Burston, “Entertaining Mother Ethel”, quoted in Jean Fraser, “Celestial Bodies”, 79. ↩︎

-

28

Wilcox, Queer Nuns, 78. ↩︎

-

29

Steve Bruce, “The Truth about Religion in Britain”, Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 34, no. 4 (1995): 426. See also Steve Bruce, Religion in Modern Britain (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995). ↩︎

-

30

Tony Glendinning and Steve Bruce, “Privatization or Deprivatization: British Attitudes About the Public Presence of Religion”, Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 50, no. 3 (2011): 510. ↩︎

-

31

Liza Filby, “God and Mrs Thatcher: Religion and Politics in 1980s Britain”, PhD thesis (University of Warwick, 2010), 13. See also Andy Walton, Andrea Hatcher, and Nick Spencer, Is There a “Religious Right” Emerging in Britain? (London: Theos, 2013). ↩︎

-

32

Filby, “God and Mrs Thatcher”, 13. ↩︎

-

33

Graeme Smith, “Margaret Thatcher’s Christian Faith: A Case Study in Political Theology”, Journal of Religious Ethics 35, no. 2 (2007): 236. ↩︎

-

34

Grace Davie, “‘An Ordinary God’: The Paradox of Religion in Contemporary Britain”, British Journal of Sociology 41, no. 3 (1990): 395. ↩︎

-

35

Street evangelism and the presence of missionaries in urban settings in the United Kingdom is relatively understudied. For an overview on the Jesus Army, a notable movement active in the 1980s and 1990s, known for its brightly painted double-decker buses and recognisable style of clothing, see David V. Barrett, The New Believers: Sects, “Cults” and Alternative Religions (London: Cassell, 2001), 226–68. ↩︎

-

36

Martin Pendergast, “HIV in Britain 1982–1990: The Christian Reaction”, Blackfriars 71, no. 840 (July–August 1990): 347. ↩︎

-

37

Pendergast, “HIV in Britain”, 347–48. ↩︎

-

38

Pendergast, “HIV in Britain”, 348. The portrayal of HIV/AIDS as God’s punishment has been studied primarily in the American context: see Michael McCabe, “AIDS and the God of Wrath”, Furrow 38, no. 8 (August 1987): 512–21; Mark R. Kowalewski, “Religious Constructions of the AIDS Crisis”, Sociological Analysis 15, no. 1 (1990): 91–96; and Anthony M. Petro, After the Wrath of God: AIDS, Sexuality, & American Religion (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015). However, examples of this rhetoric can also be found in the British news media: see Hugh Whittow, “AIDS Is the Wrath of God, Says Vicar”, Sun, 7 February 1985, and John Lisners, “I’d Shoot My Son If He Had AIDS, Says Vicar”, Sun, 14 October 1985. ↩︎

-

39

Pendergast, “HIV in Britain”, 347–48. ↩︎

-

40

Pendergast, “HIV in Britain”, 347–48. ↩︎

-

41

The General Synod is the national assembly of the Church of England and is made up of elected members of the laity and clergy, including all Church of England bishops. The synod is responsible for debating and passing legislation that affects all areas of the Church, including forms of worship, matters of religious and public interest, and the setting of budgets. ↩︎

-

42

Robert Runcie, quoted in Jonathan Petre, “Synod Rejects Call to Oust Practising Homosexuals”, Daily Telegraph, 12 November 1987. ↩︎

-

43

Lucas, Outrage!, 77. ↩︎

-

44

Walter Ellis, “Towards a More Muscular Christianity”, Sunday Telegraph, 15 November 1987. The evangelical movement within the Church of England, sometimes referred to as the Christian right or conservative Christianity, had been growing steadily since the early 1970s. Articles such as “Evangelicals on the Move”, published in the Church Times in 1987, point to an awareness of the growth of the movement within the Church at this time. See Michael Saward, “Evangelicals on the Move: An Analysis of Their Increasing Influence”, Church Times, 30 October 1987, and Michael Saward, The Anglican Church Today: Evangelicals on the Move (London: Mowbray, 1987). On the growth of the Holy Trinity Brompton (HTB) group of churches, see Cristina Odone, “A Contagious Case of HTB”, Spectator, 20 September 1997. For a study of the main evangelical beliefs during this period, see Christopher Sinclair, “Evangelical Belief in Contemporary England”, Archives de Sciences Sociales de Religions 38, no. 82 (1993): 169–81. For the continuing role of evangelicalism within the Anglican Church, particularly on how it thinks about homosexuality, see Christopher Craig Brittain and Andrew McKinnon, “Homosexuality and the Construction of ‘Anglican Orthodoxy’: The Symbolic Politics of the Anglican Communion”, Sociology of Religion 72, no. 3 (2011): 351–73. ↩︎

-

45

Sally Brompton, “Sally Brompton Talks to Two Ministers in Neighbouring Parishes Who Hold Radically Different Views”, Times, 11 November 1987; “Humbug in the Pulpit”, Star, 12 November 1987. ↩︎

-

46

Tom Lovell, “Kinky Vicar’s Gay Playtime”, People, 15 November 1987; Chris Blythe, “Evil Fantasies of Kinky Canon”, News of the World, 4 June 1989. ↩︎

-

47

Editorial, News of the World, 9 July 1989. ↩︎

-

48

Timothy W. Jones, “Moral Welfare and Social Well-Being: The Church of England and the Emergence of Modern Homosexuality”, in Men, Masculinities and Religious Change in Twentieth-Century Britain, ed. Lucy Delap and Sue Morgan (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), 197–217. ↩︎

-

49

Ian Lucas has recorded the emotional responses of many queer activists to the attitudes of the Church of England in his oral history of Outrage!, along with protests against the cChurch organised by Outrage! throughout the earlier 1990s. See the chapters “The Whores and the Three Legged Man” and “Bashing the Bishops (Again)” in Lucas, Outrage!, 73–86, 202–7. See also William Whyte, “OutRage! Hypocrisy, Episcopacy and Homosexuality in 1990s England”, Studies in Church History 60 (June 2024): 533–56, DOI:10.1017/stc.2024.19. ↩︎

-

50

Sister Dominatrice des Hommes interviewed on Dial Midnight, episode 8, aired 4 December 1992 on London Weekend Television, videocassette (VHS), 58: 52, donated to the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence Archive, Bishopsgate Institute, London, Nunz-VHS Recordings of Various Sisters TV Appearances, SOPI/BEL/3. ↩︎

-

51

Keenan, “From Friars to Fornicators”, 394. ↩︎

-

52

Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, “Who Are the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence?” ↩︎

-

53

Responses from the public to Celestial Bodies recorded in the visitors book of Stolen Glances: Lesbians Take Photographs, Edinburgh, 1991, Tessa Boffin Archive, University for the Creative Arts, Rochester, NY, BOFF/1/3/4. ↩︎

-

54

Marjo Kaartinen, Religious Life and English Culture in the Reformation (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002), 1, 109. ↩︎

-

55

Francis E. Dolan, “Why Are Nuns Funny?”, Huntingdon Library Quarterly 70, no. 4 (2007): 510. ↩︎

-

56

Kate Chedgzoy, “‘For Virgin Buildings Oft Brought Forth’: Fantasies of Convent Sexuality”, in Female Communities, 1600–1800: Literary Visions and Cultural Realities, ed. Rebecca D’Monté and Nicole Pohl (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2000), 54. ↩︎

-

57

John Nicholas Murphy, Terra Incognita; or, The Convents of the United Kingdom (London, Longmans, 1873), quoted by Susan O’Brien, “Terra Incognita: The Nun in Nineteenth-Century England”, Past & Present 121 (November 1988): 110. ↩︎

-

58

Susan P. Casteras, “Virgin Vows: The Early Victorian Artists’ Portrayal of Nuns and Novices”, Victorian Studies 24, no. 2 (1981): 160. See also Dominic Janes, “The Role of Visual Appearance in Punch’s Early Victorian Satires on Religion”, Victorian Periodicals Review 47, no. 1 (2014): 66–86. ↩︎

-

59

Maureen Moran, Catholic Sensationalism and Victorian Literature (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2007), 80–84. ↩︎

-

60

Dominic Janes, “The Confessional Unmasked: Religious Merchandise and Obscenity in Victorian England”, Victorian Literature and Culture 41, no. 4 (2013): 679. ↩︎

-

61

Hilary Davidson, “Sex and Sin: The Magic of Red Shoes”, in Shoes: A History from Sandals to Sneakers, ed. Giorgio Riello and Peter McNeil (Oxford: Berg, 2006), 273. ↩︎

-

62

Chedgzoy, “‘For Virgin Buildings Oft Bought Forth’”, 32. ↩︎

-

63

Dominic Janes, “William Etty’s Magdalens: Sexual Desire and Spirituality in Early Victorian England”, Religion and the Arts 15, no. 3 (2011): 289. ↩︎

-

64

Julie Peakman, Mighty Lewd Books: The Development of Pornography in Eighteenth-Century England (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003), 147. ↩︎

-

65

Casteras, “Virgin Vows”, 175. ↩︎

-

66

Caoimhín de Bhailís, “Alfred Elmore: Life, Work and Context”, PhD thesis (University College Cork, 2017), 118. ↩︎

-

67

Ariel Kline, “Is the Painting a Grave? John Everett Millais and the Queer Refusals of Victorian Art”, British Art Studies 24 (2023): 8, DOI:10.17658/issn.2058–5462/issue-24/akline. ↩︎

-

68

Francesco Ventrella, “Voicing the Queer Self: Listening to Portraits with Vernon Lee”, Art History 46, no. 3 (2023): 450. ↩︎

-

69

Terry Castle, The Apparitional Lesbian: Female Homosexuality and Modern Culture (New York: Columbia University Press, 1993), 96. ↩︎

-

70

Linda Hutcheon, “The Politics of Postmodernism: Parody and History”, Cultural Critique 5 (1986–87): 184. ↩︎

-

71

Denis Diderot, The Nun (London: Penguin Books, 1974 [1760]); Judith C. Brown, Immodest Acts: The Life of a Lesbian Nun in Renaissance Italy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986); Cherry Smyth, “Forbidden Grace”, unpublished paper; Rosemary Keefe Curb, “What Is a Lesbian Nun?”, in Lesbian Nuns: Breaking Silence, ed. Rosemary Keefe Curb and Nancy Manahan (London: Columbus Books, 1985), xxvii; Burston, “Entertaining Mother Ethel”, all cited in Fraser, “Celestial Bodies”, 77–79. ↩︎

-

72

Diderot, The Nun, cited in Fraser, “Celestial Bodies”, 78. ↩︎

-

73

Nina Levitt, “Conspiracy of Silence”, in Stolen Glances, ed. Boffin and Fraser, 61. ↩︎

-

74

Jean Fraser and Tessa Boffin, “Tantalizing Glimpses of Stolen Glances: Lesbians Take Photographs”, Feminist Review 38 (1991): 20–31; Tessa Boffin and Jean Fraser, “Stolen Glances: Lesbians Take Photographs”, in “The Lesbian Issue”, special issue, Feminist Studies 18, no. 3 (1992): 550–62. ↩︎

-

75

Brown, Immodest Acts. Readers may be aware of the tale of Benedetta Carlini through the film Benedetta (dir. Paul Verhoeven, 2021), based on Brown’s book. ↩︎

-

76

Brown, Immodest Acts, 4. ↩︎

-

77

Nancy Manahan and Rosemary Keefe Curb, eds., Lesbian Nuns: Breaking Silence (Tallahassee, FL: Spinsters Ink, 2013 [1985]), Kindle. ↩︎

-

78

Rosemary Keefe Curb, “What Is a Lesbian Nun?” In Lesbian Nuns, ed. Manahan and Curb, loc. 388–574. ↩︎

-

79

The publishing history of the book is outlined in the foreword to the 2013 edition: Joanne E. Passet, “Foreword: Lesbian Nuns: Breaking Silence, Revered and Reviled”, in Lesbian Nuns, ed. Curb and Manahan, loc. 110–379. ↩︎

-

80

Passet, “Foreword”, loc. 150–70. ↩︎

-

81

Lillian Faderman, Review of Immodest Acts: The Life of a Lesbian Nun in Renaissance Italy, by Judith C. Brown, and Lesbian Nuns: Breaking Silence, ed. by Rosemary Curb and Nancy Manahan, Signs 12, no. 3 (1987): 576–79. ↩︎

-

82

Passet, “Foreword”, loc. 204. See also Rosemary Curb, “Lesbian Nuns Controversy: Rosemary Curb Responds”, Off Our Backs 15, no. 9 (October 1985): 27; Julia Penelope, “The Perils of Publishing”, Women’s Review of Books 2, no. 12 (September 1985): 3–6. ↩︎

-

83

Hutcheon, “The Politics of Postmodernism”, 184. ↩︎

-

84