Jay Prosser and St. Pelagius the Penitent at the Transgender Film Festival, or What Happened to Trans British Art?

Jay Prosser and St. Pelagius the Penitent at the Transgender Film Festival, or What Happened to Trans British Art?

By Evelyn Whorrall-Campbell

Abstract

This article returns to the First International Transgender Film & Video Festival (TFF) in 1997 to historicise transgender artistic production and its relation to queer theory and aesthetics at a time when the categories “transgender” and “queer” were being formed. Identifying the twin discursive sites of cinema and scholarship as forums for claims about definition, the article tracks the self-conscious production of transgender studies and its objects of study in proximity to queer. By moving through the writing of the festival panellist and academic Jay Prosser and Jason Barker’s St. Pelagius the Penitent (1997), one of TFF’s programmed films, the article situates the field of transgender studies in a British context. The article brings a humorous attitude to the various promises and limitations offered by queer and trans thinking at this historical juncture in the 1990s, which accommodates a material approach to transgender studies not limited by appeals to the real.

The Transgender 1990s

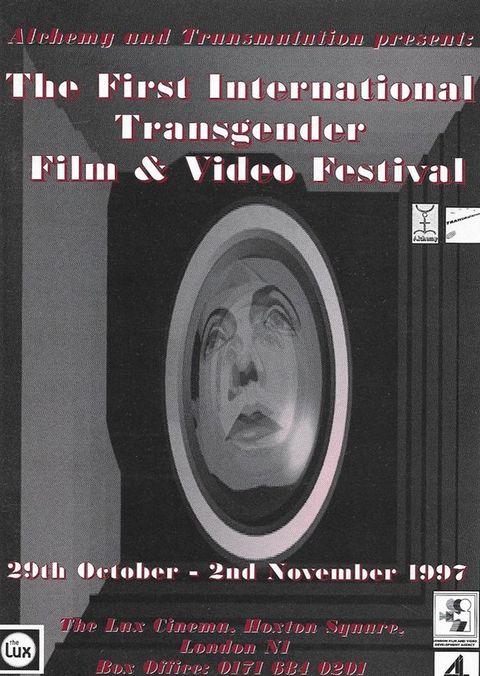

The First International Transgender Film & Video Festival (TFF) opened in October 1997 at the Lux Centre in Hoxton Square, London, the recently completed purpose-built home for the newly merged London Filmmakers Co-op and London Electronic Arts. In his introduction to the festival in the accompanying brochure, its co-founder Zachary Nataf invokes a familiar trans genre, the elegy:1

12I would like to dedicate this First International Transgender Film & Video Festival to the memory of Consuela Cosmetic who died with AIDS in March 1996 during the post-production of Mirror, Mirror …[;] to Venus Xtravaganza, one of the stars of Paris Is Burning … who was murdered for being transsexual just before the film was released in 1990[;] to Brandon Teena, a young man who was kidnapped and gang-raped to try to prove to him that he was not a man and later murdered by his abductors in Nebraska in 1993 when police failed to pursue the charges brought. … And to Candy Darling, a Warhol superstar in the 1970s … who died at the age of thirty from complications from her hormone treatment.2

I repeat Nataf’s words here not to propose that trans life is epistemologically valuable only in death, but because his list of American trans icons may complicate this article’s claim to historicise the “trans 1990s” in a special issue on queer art in Britain.3 Along with Cosmetic, Xtravaganza, Teena, and Darling, Nataf calls up US historical events and objects that have been central to queer theoretical and art-historical knowledge: the AIDS epidemic in New York; Jennie Livingston’s 1990 documentary Paris Is Burning; and Andy Warhol and his Factory of genderqueer and trans performers. In Nataf’s introduction, these objects stand as artefacts of a transgender media history that his festival was engaged in writing. The significance of this elegy, and its reproduction in a special issue on queer artistic production, may be to shift queer art-historical scholarship and its coordinates to re-narrate its objects as also—and in some instances more properly—trans.

3Yet this is precisely not my point. My investment in Nataf’s words and in TFF itself is more than recuperative or recovery work, although this is undoubtedly important given the lack of scholarship on British transgender artistic production in the 1990s (indeed in any decade). Nor do I want to advocate stretching the category of “queer” to include trans. To do so would not only fail to identify “queer” and “trans” as terms with overlapping but distinct uses in the 1990s, but also risk their collapse without examining the discursive conditions that have produced the possibility for this indistinction and, as such, curtail our ability to think what trans was, is, and could have been. I am interested instead in examining the 1990s as the decade when queer and transgender studies began, to understand the difficulty of historicising Nataf’s introduction and TFF itself in trans studies today. Why has there been so little attention to transgender artistic and theoretical production in Britain? Why do we struggle to articulate “trans” as a historical and contemporary category of analysis but not “queer”? Or, to put it another way, why has queer expanded to include trans but not the other way around, as was imagined by many users of the term “transgender”, including Nataf and others associated with TFF?

By returning to TFF, the ideas of one of its panellists (Jay Prosser), and one of its programmed films (Jason Barker’s 1997 “creative documentary” St. Pelagius the Penitent), I hope to historicise transgender artistic production and its relation to queer theory and aesthetics at a time when both “transgender” and “queer” were categories that were being formed. I identify the discursive sites of cinema and scholarship as twin forums for different claims about how the new term “transgender” should be defined, tracking the self-conscious production of transgender studies and its objects of study in proximity to queer. I move through a discussion of TFF, the work of Jay Prosser, and Barker’s short film to recast the field of transgender studies in a British context, indicating the precarious existence of radical transgender praxis in 1990s Britain. In recognising the various promises and limitations offered by the relation between this praxis and queer forms of thought and politics, this article offers an alternative to the impasse between transgender and queer studies.4 Instead of Prosser’s autobiographical attitude, I argue for approaching transgender studies with a sense of humour to find an alternate transgender genre in the comedic. St. Pelagius’s combination of comedy with hagiography allows me to read the film for the joke’s suspension of disbelief, a critical position from which to undertake a material analysis of trans politics that is not limited by appeals to what might count as real.

4As such, I first pursue a historical reading, situating TFF in a genealogy of transgender in the 1990s to provide a useful account of the festival for future scholarship. TFF’s role in bringing together British-based artists, writers, and scholars and their American and European counterparts is important in re-specifying transgender in Britain. Second, I turn to Jay Prosser’s ideas, rehearsed at TFF and in his writings, to elaborate the differences between cinema and scholarship as discursive sites for producing knowledge about trans life. This intervention is historiographic. I seek to understand how “transgender” as a political, aesthetic, and identarian category took shape at the end of the twentieth century and what its contingency meant, and indeed could mean, for transgender studies as a disciplinary formation going forward. Finally, I pursue a close reading of St. Pelagius to advance the film’s usefulness for rethinking transgender studies. Through humorous experiments in hagiography, St. Pelagius transforms the proximity of trans life to death by comedically restaging an angelic ascension as an act of (perverse) wish fulfilment and collective suspension of disbelief: hate your gender; try leaving it behind.

Film-makers Talk Transgender

From 1997 to 1999, the International Transgender Film & Video Festival gathered trans film-makers, artists, performers, community activists, and scholars together annually for a five-day programme of screenings, live art, visual art exhibitions, and panel discussions at the Lux Centre (fig. 1).5 Organised by the film-makers Zachary Nataf and Annette Kennerley, the festival was backed by a new “transgender cultural organisation” called Transmutation, founded with two central objectives: to promote transgender self-representation and to develop opportunities for transgender cultural production. Transmutation’s steering committee included transgender film-makers, artists, and writers, among them Jason Barker, Simon Dessloch, and Mijka Scott. TFF was imagined as one avenue by which Transmutation might achieve its goals.

5

According to the welcome statement by Kate More and Mijka Scott, on behalf of Transmutation, the aim of TFF was “to advance cultural works by and/or about transgender people of all races, classes, creeds, abilities and sexualities, representing the full spectrum of the community, in order to contribute to creating a sense of self worth and pride, especially for transgender youth”.6 Central to producing “transgender pride” was the festival’s commitment to “challenge mainstream society’s negative and stereotyped representations of transgender people”.7 This was marked by an annual prize, the Alchemy Award, given to producers or film-makers of a work that had “made the most impact that year in terms of accurate and diverse transgender representation and the countering of negative stereotypes”.8 A second aim opened up as a result of the festival’s interest in representation, namely, the need to resolve a problem of definition: what was “transgender film and video”? As More and Scott wrote in their statement, the festival programme was selected to provide an overview of “transgender cinema history firsts” alongside documentaries, artists’ shorts, and independent features to delineate what More and Scott called—in a phrase unavoidably evocative of Sandy Stone’s linguistic slippages—“a transgender genre”.9

6Further to these aims, the First International Transgender Film & Video Festival held numerous discussion panels with trans scholars and activists alongside the screenings, situating the films in a broader discursive, political, legal, and imaginative context. This was a dialogic mode that also characterised other queer cultural interventions, including the Lesbians Talk Issues series of short books from Scarlet Press, for which Nataf had written Lesbians Talk Transgender in 1996.10 Despite the festival’s inheritance from sexual politics, these panels, with titles such as “Representation & Trans-Aesthetics”, “Trans-Youth” and “Cybergender”, registered TFF’s specific aesthetic and political concerns as separate from those of the gay and lesbian community. Susan Stryker, the American theorist and historian central to the establishment of transgender studies in America, was invited to speak on the “Cybergender” panel. Writing later about the 1990s, Stryker returned to themes raised at TFF, commenting on the decade’s specificity with regard to technological change and its impact on transgender representation. For her, the 1990s were exemplified by a new language of transgender describing the separation of (biological) sex from (cultural) gender, which also encapsulated something of digital media’s reshaping of reality by separating representation from the need for a material referent.11 In the 1990s transgender raised aesthetic and material questions that ventriloquised the novelty of other societal changes, including the impending millennium and its promise of a digital revolution. TFF was a site not only for experiments in transgender representation but also where scholars could elaborate interpretative frameworks for these experiments in dialogue with the works themselves.

10TFF remained close to the more established London Lesbian and Gay Film (LLGFF) Festival, held at the British Film Institute and then in its eleventh year. TFF screened some of the same films, including Hans Scheirl’s experimental transgender cyborg slasher feature Dandy Dust (1998), and worked with the same people; for example, Cherry Smyth, curator of the LLGFF from 1992 to 1996, was also TFF’s volunteer coordinator and a member of the programme advisory committee. But a space apart for transgender artistic production was still considered a political imperative.12 Nataf described lesbian and gay endeavours as TFF’s inspiration but considered them insufficient to address transgender audiences: “One of the reasons I set up the transgender film festival was to do for transgender audiences what lesbian and gay film festivals … had done for gays: to de-pathologise transgender subjectivities and to empower that audience by giving them representations of transgender people which were not oppressive”.13 Implicit in this statement is the claim that transgender faced different representational dilemmas that could not be adequately discussed in lesbian and gay settings even where the same films were screened. TFF therefore marked, if not a separation of content, at least an attempt at a separation of context.

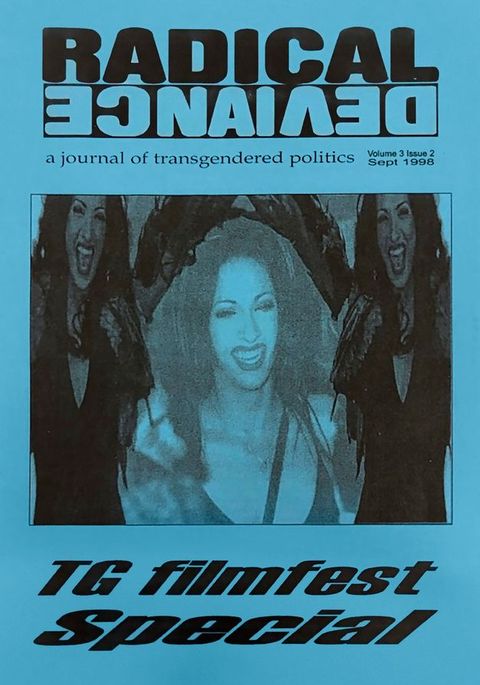

12TFF’s understanding of transgender as a distinct category of analysis that raised unique questions of theory and politics paralleled endeavours by individuals outside their association with the festival. Kate More was co-editor of the short-lived publication Radical Deviance: A Journal of Transgendered Politics, which, like TFF, ran between 1996 and 1999. More, via the journal, sought to generate novel theories of gender transition from and against those that had already been defined by feminism, lesbian and gay studies, postmodernism, and queer theory, with many of the same people who appeared at the film festival.14 The journal and the festival intersected in multiple ways. More was engaged in editorial work from her position at Gender & Sexuality Alliance (G&SA), an organising group initially based in Middlesbrough that produced Radical Deviance and was one of TFF’s sponsors. Many G&SA members, including Roz Kaveney, Zachary Nataf, Jay Prosser, and Stephen Whittle, both spoke at TFF and wrote for Radical Deviance. An issue of Radical Deviance was dedicated to the previous year’s festival in 1998 (figs. 2 and 3), and a short book of film reviews, including many that had been screened at TFF, was later compiled, fulfilling the festival’s desire to produce a trans media history.15 The existence of G&SA, TFF, and Radical Deviance reflected an aim to create distinct spaces for British transgender theory and practice at the end of the twentieth century.

14

G&SA, TFF, and Radical Deviance also demonstrate the centralising force London exerted on transgender activism throughout the 1990s. In 1997 G&SA relocated from Middlesbrough to occupy the old Marxism Today offices close to King’s Cross in London. The group had previously been supported by Cleveland County Council through council’s equal opportunities and HIV units, but in 1996 G&SA lost its access to resources when the authority was dissolved under the Local Government Act 1992. Responsibility for Cleveland’s activities was passed on to Stockton Borough Council, which funded the first two issues of Radical Deviance but quickly decided it could not offer long-term support.16 The very factors that had initially secured G&SA its funding were the reason for the group’s eventual precarity. While local authorities could occasionally redirect money creatively, this funding was always at risk of being taken away. There were a greater number of different potential funding streams in London, both public and private, which meant that transgender activity coalesced in the city as groups cross-funded each other’s activities and individuals took up positions across multiple projects. The Beaumont Society, the Gender Trust / GEMS, and TV/TS News joined G&SA in offering TFF organisational and promotional support. However, being in the capital was no guarantee of secure funding and TTF was forced to end after 1999.

16If transgender audiences required their own festival apart from gay and lesbian audiences, and transgender readers their own journal, this raised the question of not only what counted as transgender film but also what counted as transgender, that is, who was included under the label and on what grounds. TFF deployed “transgender” as an umbrella term that could best, though imperfectly, contain a variety of experiences of sexual and gender diversity.17 The festival programme offered this working definition:

1718By transgender we mean all people who challenge traditional assumptions about gender, i.e., all self identified cross gender people whether intersex, transsexual men and women, transvestites, cross-dressing drag kings and drag queens, cross-living transgenderists and the spectrum of androgynous, bi-gendered, third gendered and as yet unnamed gender variant and gender gifted people in our community.18

This broad church approach was in line with contemporary uses of the term in activist and community movements, signalling both a wresting of the definition from the medical gatekeeping bound up in the term “transsexual” and a new coalitionary politics founded on the basis of gender rather than sexual deviance.19 In hir preface to Transgender Warriors, Leslie Feinberg defined “transgender” capaciously:

1920Today the word transgender has at least two colloquial meanings. It has been used as an umbrella term to include everyone who challenges the boundaries of sex and gender. It is also used to draw a distinction between those who reassign the sex they were labelled at birth, and those of us whose gender expression is considered inappropriate for our sex.20

This coalitionary term usefully expressed the political aims of Nataf’s Lesbians Talk Transgender, a British text aimed at negotiating the contested and shared ground between lesbians and trans(gendered) or trans(sexual) individuals. Nataf reproduced Kate Bornstein’s call for gender-based solidarity between lesbians, gay men, and trans people:

21lesbians and gay men actually share the same stigma with “transgendered” people: the stigma of crimes against gender … So let’s reclaim the word “transgendered” so as to be more inclusive … Then, we have a group of people who break the rules, codes, and shackles of gender. Then we have a healthy-sized contingent! It’s the transgendered who need to embrace the lesbians and gays, because it’s the transgendered who are in fact the more inclusive category.21

Bornstein’s inclusive ambitions were also reflected in the festival’s film selection, which included a range of works with different investments in transgender identity. “The Divine Androgyne: Fluid Gender Shorts”, the section of the first TFF under which Jason Barker’s St. Pelagius was shown in 1997, brought together a variety of gendered subjects and genres, including experimental film and video work, docu-shorts, and a music video, from the United States, United Kingdom, Germany, and Australia.22 Summarised in the festival programme as about “both genders, neither gender, beyond gender and genders yet unnamed” as “Fluid Gender looks at a spectrum of possibilities”, “The Divine Androgyne” was a loose collection of works with various degrees of relation to transgender as an identity category. In addition to Barker’s own “transgendered saint”, the section also featured the trailer for a documentary about New York drag kings; an experimental short about an angelic-hermaphroditic companionship; Kiki and Herb’s rendition of “Total Eclipse of the Heart”; an elegiac reflection on gender performativity through transvestism; a gothic-techno-noir-Frankenstein-genderfuck film; and a documentary portrait of the genderqueer artist Lorenza, who has a dream of growing wings.

22Besides absorbing various gendered/sexually non-normative motifs and subjects into its definition of transgender, as Bornstein’s definition indicates, TFF’s commitment to coalition also reflected the workings of a queer epistemology and politic at large, where divestment from the fixity of “lesbian” and “gay” promised to offer a way out of the impasse of identity. As has been observed by many scholars since the 1990s, to various degrees of opprobrium, “queer” was in part newly constituted as a field of study over an interest in gender nonconformity. Transgender was, as Andrea Long Chu and Emmett Harsin Drager argue, arrogated by the discipline of queer theory with the effect of, at least in the university, stymying the development of trans theory proper.23 Yet, where queer theory made gender-crossing subservient as a sign of sexuality, Bornstein’s solidaristic comment raised the hope that transgender could reverse this logic, smoothly incorporating queer under the primary analytic of gender, where social violence against gay and lesbian subjects could be explained by the threat that same-sex behaviour posed to the gender binary.24

23This coalitionary definition complicated TFF’s commitment to modelling industry standards for transgender representation. Transgender as coalition sought to use the term “transgender” less as an identity for a specific group of people with shared characteristics and more as an analytic framework, where gender would replace sexual object choice as the primary lens through which to understand and therefore challenge normativity and its oppressions. In separating transgender from one specific image of selfhood, this analytic approach could include a loose conglomerate of subjects who fell outside gendered norms, including those whose nonconforming gender identification was understood as part of their sexual identity. However, if the category of transgender were to include lesbians and gay men, how would TFF speak to the representational concerns facing audience members who found themselves in circumstances that were unique to gender transition, concerns that had prompted Nataf to create a separate festival in the first place? The question of who was being addressed was particularly relevant to the positive image strategies pursued by TFF and promoted by the festival’s Alchemy Award, which rewarded work that challenged negative stereotypes of trans life through “accurate and diverse” representations.25 But where there was no clear subject what single representation would be the most accurate illustration of transgender as coalition? The films selected for this annual prize—The Wrong Body (1996), directed by Oliver Morse for Channel 4; Alain Berliner’s feature Ma vie en rose (1997); and Woubi, Chéri (1998), directed by Laurent Bocahut and Philip Brooks—all mobilised the dominant trans genres of autobiography and documentary realism. By selecting these films, the award identified what an ideal transsexual subject looked like: a narrativised individual whose transition was made legible as authentic self-expression.

25These two approaches—transgender as coalition and the positive image strategy of the Alchemy Award—were kept in productive tension at TFF. While the Alchemy Award prioritised certain representations, the diversity of films throughout the festival itself offered a range of alternative transgender images and narratives that renegotiated what a transgender subject might look like. The annual screening also left the possibility open for alternative circulatory histories of these films—especially where works had been, or would go on to be, screened at lesbian and gay festivals. The panel discussions that followed screenings enabled a variety of opinions and interpretations to be shared, and both the films and the paratexts found in the printed programme to be recontextualised and reconfigured. Different screening strands permitted contradictory thinking, and audience members could drop in and out of sessions. The festival itself allowed for disagreements between the panellists and the audience and among the audience members themselves. One attendee voiced their dislike of Bestor Cram’s 1997 documentary You Don’t Know Dick, in contrast to the warm reception the film received from the rest of the audience, not only with a poor review in their column for Radical Deviance but, as they wrote, by “yelling their indignation at the screen”.26 However, this polyvocality was less easily contained when trans knowledge production moved from the festival into the disciplinary field, as the next section will show.

26Trans Studies at TFF

TFF’s panel discussions were where the festival’s own discursive framing met those of its programmed films and of academics who were defining the burgeoning field of trans studies. Alongside British-based artists, cultural organisers, and academics such as Kristiene Clarke, Roz Kaveney, Kate More, Jay Prosser, Cherry Smyth, Del LaGrace Volcano, and Stephen Whittle, the festival also attracted Chris Straayer and Susan Stryker from the United States.27 The festival’s first panel, “Representation & Trans-Aesthetics”, brought together Clarke, Straayer, Kaveney, and Prosser to discuss the stakes of transgender artistic production and representation: as the programme summarised it, “who is representing us, why and how?” The only record of the discussion exists in the short preview in the printed programme, which summarised each panellist’s contributions. Kristiene Clarke spoke on her own film projects and the future of trans representation, Roz Kaveney on Andy Warhol’s Women in Revolt and historic representations, Chris Straayer on the potential of negative representations of trans life, and Jay Prosser on transsexual autobiography and trans genres.28

27Not all the summaries were brief. In contrast to the other panellists, Prosser was given a page write-up in the programme. Prosser’s talk, “Transsexual Narrative (Not a Queer Performative)”, drawn from his as yet unpublished book Second Skins: The Body Narratives of Transsexuality, argued that the distinctive aesthetic, formal, and genre concerns of trans artistic production were separate from those of queer modes. This presentation raised ideas that were central to Second Skins: that queer is not a useful approach for theorising transsexuality; that transsexuality and transgender are distinct categories of identity and analysis; that transgender is not an umbrella term that contains transsexuality but has displaced the latter in its expansive non-specificity. Prosser’s main issue with transgender, both as a coalitionary politic and as a critique of the medical capture of gender transition, was its queering of transsexuality, or, as Prosser put it, a “pride in queer difference”.29 However, worse than the post-transsexual adoption of queer politics was the adoption of transgender as a privileged object for the new project of queer studies, with gender transition illustrating deconstructionist reading strategies that “disembody sex” and transsexuality’s attachment to it.30 The subtitle of Prosser’s talk, “Not a Queer Performative”, was a pointed reference to what was to become in Second Skins a thorough critique of Judith Butler’s theory of performativity, which represented for Prosser the worst contribution of queer studies to understanding gendered subjectivity.31

29I have picked up Prosser’s presentation and Second Skins here rather than those of his fellow panellists, in part because of the more detailed record of his presentation at TFF but also because of his unique position straddling British and American transgender discourse. Besides his involvement in TFF, Prosser was a member of G&SA and a regular contributor to Radical Deviance, although the journal described his work as bearing “little relationship to the theoretical concerns occupying trans in the UK”. For Radical Deviance’s Matt Lee, this raised the question of whether Prosser should be considered “American or English [sic]” in his academic work.32 That Prosser’s Second Skins continues to be cited in contemporary American trans studies suggests the former.33 Moving between the British film festival and US scholarship as he did, Prosser is useful for showing the differing contexts in which knowledge about transgender subjectivity and aesthetics were debated and shaped. However, while his ideas entered the academy through Second Skins, this shift displaced the British sites of trans theoretical and cultural production to which Prosser belonged in the 1990s, obscuring them and their contributions to trans theory.

32Unlike the other panellists, Prosser provided a direct answer to the overarching question raised by TFF as to what made a film trans and not queer. TFF supported a less definitive approach, emphasising, as Nataf did in his introduction to the first festival, the importance of a community context in producing trans readings of films, but Prosser’s critique was clear. For him, the “definitive aesthetic form or generic mode” of transsexuality was autobiography, including its literary, photographic, and documentary forms. He claimed this was borne out historically and psychologically, given that the imperative to narrate oneself to doctors was fundamental to transsexuality’s emergence as a coherent subject position in the early twentieth century.34 Indeed, Prosser presented narrative as the prime, if not only, form capable of representing transsexuality: “How else is transsexuality, this internal feeling of embodied sexual difference that yet by definition does not initially manifest itself on the body, to be read except through autobiographical narrative?”35 Prosser’s claims at TFF, therefore, bound aesthetics to epistemology, installing a narrativised transsexual subject as the correct political addressee of the new field of trans studies, separate from queer.36

34Prosser’s writing demonstrated a concern to wrest the meaning of transsexuality from queer studies (as exemplified by Butler), which at best failed to account for the aetiology of transsexual identification as a felt interiority, and at worst cruelly deliteralised transsexual bodies through a perverse reification of genital sex. This wresting, through powerfully indicating the effect of queer’s eclipse of transsexuality on ways of thinking about trans subjectivity, aimed to produce a new disciplinary field: trans studies. At TFF and later in Second Skins, Prosser attempted to define a new field of study via an exclusive object: autobiographical narrative. His book focused on memoir and portrait photography as the two primary forms of autobiography because of their ability to “realistically” represent their subjects. Outside the pages of the book, however, demarcating autobiography was not straightforward. While the Alchemy Award largely upheld Prosser’s argument, the wide variety of genres present at TFF demonstrated the difficulty of limiting the autobiographical mode to strictly faithful depictions of reality.37 In practice, the difference between queer and trans could not be reliably based on a division between trans autobiography and queer performativity. This article will later discuss a film screened at TFF that demonstrates the coexistence of these modes: Jason Barker’s St. Pelagius the Penitent.38 However, this was not the only departure between the accounts of trans life offered by Second Skins and at TFF.

37The Ultimate Failure of the Transsexual

In the first chapter of Second Skins, Prosser argues that “[i]t is transgender that makes possible the lesbian and gay overlap … it is surely this overlap or cross-gendered identification between gay men and lesbians—an identification made critically necessary by the AIDS crisis that ushers in the queer moment”.39 If transgender emerged as a result of AIDS, as he suggests, he is quick to move past the epidemic—a move that draws attention given his stated investment in the materiality of the body against queer’s linguistics. The absence ghosting Prosser’s statement here is, of course, the (unimaginable) affected trans subject—despite, as Che Gossett and Eva Hayward point out, the historical and contemporary fact of trans people living/dying with AIDS.40 Indeed, this move seems more incongruous when we consider the institutionalisation of “transgender” by American and British social service providers and community organisations involved in safer-sex outreach in the 1990s, for whom the umbrella term served as a useful shorthand to replace a diverse range of self-identifications.41 TFF, however, was more than capable of imagining trans life and death as coexistent with the epidemic. The festival was dedicated to the memory of Consuela Cosmetic following her death from AIDS, and was explicit about its intention to raise funds for the production of “HIV/Safe Sex materials for trans people” through the gala and other efforts.42 Rather than being absent from trans community consciousness, the festival placed AIDS front and centre in its programming efforts. This consciousness was lost when Second Skins was read outside this context in the field of trans studies.

39Prosser’s difficulty connecting trans life to AIDS in Second Skins is accompanied by a secondary separation—of trans life from feminism. He argues not only that transgender is necessary to produce queer out of lesbian and gay solidarity in the face of AIDS, but also that it is vital to queer studies’ separation from feminism. According to this logic, transgender allows queer to break from feminism through male identification. Prosser cites Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick on the “courageous history of lesbian trans-gender role-playing and identification” to argue that queer theorists produced transgender as an alternative critical heuristic to feminism when they themselves left femininity behind.43 As with its inability to imagine the coexistence of AIDS and transsexuality, Second Skins’ insistence, in Awkward-Rich’s words, “on the absolute difference of trans” also struggles to imagine the possibility that trans subjectivity can be co-constituted through feminist and queer commitments.44

43The narrative of Second Skins ignores certain historical facts. Its vision of trans studies cannot, for example, account for Roz Kaveney, a fellow speaker on Prosser’s panel, who was central to British lesbian feminist activism through the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s, a member of London’s Gay Liberation Front TV/TS Group, co-organiser of the dyke SM club night Chain Reaction, and co-founder of Feminists Against Censorship.45 Or for Annette Kennerley, co-founder of TFF with Zachary Nataf, who came to trans organising from her involvement in lesbian activism and film-making. Or for Nataf himself, whose Lesbians Talk Transgender, a text interweaving trans-, queer-, and lesbian-identified voices to “talk transgender” in relation to same-sex desire, demonstrates his aim to “retain ties with the lesbian community” he first came out into, “which proved to be fertile ground for subverting patriarchal gender norms”.46 Indeed, Radical Deviance, which shared many members with TFF, originated in the G&SA’s outreach involvement with transgender and transsexual sex workers in Newcastle, supported by Cleveland County Council’s HIV unit. The publication continued to promote safer-sex projects even when ties with Cleveland were cut following the local authority’s dissolution in April 1996.47 Second Skins’ account of transgender’s historical development as a category originating in queer studies obscures the more complex interconnections that made up British lesbian, queer, and trans organising. Trans activists and trans demands were present in feminist and queer politics in ways that predated and were coterminous with queer studies’ interest in transgender.

45In claiming a separate disciplinary space for trans studies, Prosser’s book affirms the distinctiveness of transsexual identities and their aesthetic, material, and political concerns, and offers an alternative to the inadequate paradigms in feminism and queer studies for thinking gender transition. In his attempt to create a theoretical space for trans studies in the academy that did not, and still largely does not, exist in the United Kingdom, Prosser claims that queer studies over-reach into issues of trans life, if only to clarify the need to hire trans professors for programmes dominated by feminist and queer theorists.48 This claim demonstrates the difficulty facing Prosser in the United Kingdom, where gender and sexuality departments were far less common than in the United States, where trans studies found its initial institutional footings and where Second Skins was taken up in teaching and research. Against the backdrop of these disciplinary difficulties, TFF as a site for trans theorising through community was to navigate the various investments of its organisers, audience, and artists differently. Instead of an academic model of entrenchment and competition, TTF had to rely on prior and contemporaneous feminist and queer endeavours as those involved, such as Nataf and Kennerley, drew on their (previous) lived identities and organising experience. TFF also depended on help from a variety of sponsors and donors. While Channel 4 and the London Film and Video Development Agency provided some support, TFF relied on existing independent film distributors with differing political commitments. For example, the feminist film and video distributor Cinenova acted as programme sponsor and provided works for screening.

48However, despite their different formulations of transgender versus transsexual, both TFF and Prosser’s project were to come to a premature end after 1999. The financial and administrative reality of running an independent film festival in a rapidly gentrifying London eventually brought TFF to an end after its third year. The Blairite promise of a modern Britain brought about by cultural uplift proved empty. Caught up in the optimism surrounding independent film in the late 1990s, the Lux Centre, which had hosted TFF, was presented as the culture sector’s prototype for new civic-minded public–private partnerships, as an industry test case for new models of arts funding. Predictably, these new investments created an unsustainable economic climate for independent projects. The Lux Centre had been purpose-built for the National Centre for Artists’ Film, Video and Digital Art, the product of the merger of London Film-Makers’ Co-op and London Video Arts. The centre was an enthusiastic proposal that had been designed to cut costs and generate investment but, rather than mitigating the effects of gentrification and defunding, it ultimately worsened the situation.49 The centre was forced to close in 2001, following multiple flawed funding strategies and restructuring, compounded by escalating rent costs in the Shoreditch area.50 Following the failure of these funding models, a trans 2000s, at least in terms of independent cultural production, was to be characterised by an unavailability of resources, with limited possibilities for supporting projects at any scale, let alone a film festival.51

49While Second Skins continued to be cited in American queer and transgender studies, Prosser’s next book-length project, Light in the Dark Room: Photography and Loss, saw him turn away from transsexual matters. This move underscored the difficulty of continuing a career in the emergent field.52 Only one chapter of the book is dedicated to transsexuality, a version of an earlier article written by Prosser as a rejoinder to Second Skins.53 Composed as a palinode, the text mirrors the foreclosed fate of TFF, taking a less optimistic tone than Prosser’s first book and indicating some of the difficulties caused by his earlier investment in autobiography as a secure referent for the “transsexual real”.54 He now describes the quest for the real he had pursued in Second Skins as melancholic, traumatic even, as he writes: “This real—most ineffable, most impossible—may be the ultimate failure of the transsexual (all transsexuals) to be real, that is to be real-ly sexed”.55 The coincidence of these two (one literal and one conceptual) failures—of Prosser’s transsexual and of TFF—both occurring around 1999, marks one point in the precarity of transgender studies in the United Kingdom.

52The fate of TFF and of Prosser’s palinode demonstrate that reality; both the material conditions of knowledge production and the concept of “the real” itself had a horrible habit of interrupting the project of trans theorising. Second Skins attempted to legitimate transsexual identity by attaching it to an autobiographical empiricism but instead created a transsexual subject who did not reflect the more complex investments at play in sites like TFF, or even those that shaped Prosser’s own lived experience. The question that arises, then, is where else the field should look for a possible model of trans studies that can incorporate the problems of its own early foreclosure? Prosser offers one possibility when he concludes his revised thoughts on his first book. After laying out the ultimate failure of transsexuals, Prosser attempted to resolve the paradox he had just created: if transsexuality isn’t real, what does that make him? It seems, in the end, that reality makes little difference: “In spite of the fact that transsexuality is impossible this in no way prevents it from existing”.56 Transsexuality’s impossible existence—Prosser’s statement—reads like a grim joke.

56What kind of trans theorising would be possible from this contradictory position? This question animates the next section of this article, as I turn to a film that was present at the first TFF alongside Prosser: Jason Barker’s St. Pelagius the Penitent. This film formalises a set of concerns that animate the diversity of thought, including Prosser’s, expressed at TFF: worry about the material reality of transsexuality, issues of genre and representation, the painful proximity of trans life to erasure and death, and the collective project of belief in trans existence. By staging the miraculous life of a medieval saint, St. Pelagius offers an answer to Prosser’s troubled transsexual prayers.

The Sex of Angels

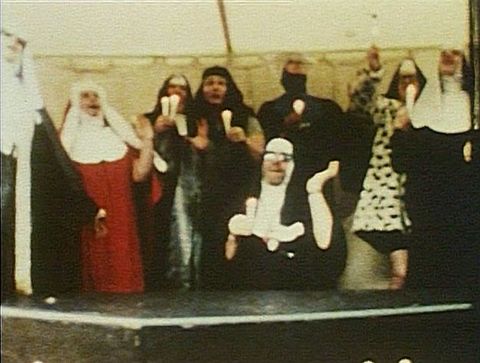

St. Pelagius the Penitent is a thirteen-minute short film directed by Jason Barker and screened at the first TFF in 1997. Described by Barker as “a film about five trans, intersex and gender queer friends and a medieval saint”, the film’s narrative is loosely structured around the hagiography of its subject, St. Pelagius of Antioch, a Christian saint from the fourth or fifth century whose legend recounts the saint’s transformation from Margarita to male eunuch.57 Each of the five featured friends, Simo, Levi, Del, Svar, and Hans, enacts a different part of Pelagius’s journey to sanctity, with each short tableau-like scene paired with a biographical section featuring verité-style footage of the performer and an asynchronous voiceover in which they discuss an aspect of their own gender transition. St. Pelagius ends with the saint’s ascension, with the five friends, now adorned with angel wings affixed by BDSM harnesses, shooting into the heavens over a soft pink sky sparkling with hand-drawn stars, as the British post-rock supergroup Snowpony’s “Come and Sit on Your Daddy’s Knee” plays the film to a close (fig. 4).58

57St. Pelagius was distributed to various European film festivals besides TFF, including the Berlin International Film Festival and the Tampere Film Festival; at Tampere it won Best Documentary. At TFF, as mentioned, the film was included in the section titled “The Divine Androgyne: Fluid Gender Shorts”.59 The title, referring to the hermaphroditic alchemical androgyne, was taken from one of the selected works, David Cutler’s video The Divine Androgyne.60 It proved a loose category—the rationale for some films’ inclusion was more obvious than others—but, nonetheless, the selection reflects a predominance of religious imagery to represent trans life and transition, as well as Nataf and Kennerley’s desire to identify this imagery for their audience.

59Unlike Prosser’s transsexual, who is resolutely distinct from queer subjectivities and histories, St. Pelagius, both in its aesthetic references and in its actual participants, attests to the inseparability of queer and trans histories without realising the concomitant fear that trans will collapse into “gender trouble”. Barker’s film features several of the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, as well as Mark Harriott, a film-maker for OutRage!, who plays the sickly “hermaphrodite” healed by a saintly miracle (fig. 5).61 Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, religious imagery was a popular aesthetic through which to launch a queer reclamation of the homophobic institutions of church and state, drawing on the historic association between Catholic excess and a decorous and effeminate homosexuality. This recuperation was a potent move in the context of the religious rhetoric surrounding AIDS and the salvific analogies between bodily mortification and sanctity in Catholic theology. Queer saints, from Jean Paul Sartre’s Saint Genet to St. Derek (of Dungeness), were joined by transgender equivalents, such as Leslie Feinberg’s Joan of Arc in Transgender Warriors and Marjorie Garber’s St. Pelagius (discussed in Vested Interests, probably the text that introduced Barker to this saint in the first place), whose deviancy was their cross-dressing rather than their sexual desire.62

61

Another recurring figural motif were angels, as attested by other films screened at TFF. Queered by Jean Cocteau and Jean Genet, these winged messengers made appearances in the post-punk work of Jarman, John Maybury, and Cerith Wyn Evans, and were repeat figures in two films by Isaac Julien and a photo series by Tessa Boffin, emblems of the lamination of queer sex with death during the epidemic.63 Although there were American counterparts, most notably Tony Kushner’s 1991 play Angels in America, these figures also describe a British network travelling through the work of queer artists and film-makers through the 1980s and 1990s. So popular were these angels that a regional history of queer art could be mapped through their recurrence. The angels in Julien’s 1989 film Looking for Langston (fig. 6) wear the same wings as those in Boffin’s photo series from the same year, Angelic Rebels: Lesbians and Safer Sex, the costume exchanged between the two artists. Jimmy Somerville of Bronski Beat fame—and co-founder with Isaac Julien, Steve McLean, and Mark Nash of the production company Normal Films—reprised his role as an angel in Looking for Langston for Sally Potter’s 1992 adaptation of Orlando. More than harbingers, these queer cherubim also brought levity to the seriousness of the terrestrial realm. From Somerville’s aerial antics in Orlando to Boffin’s reimagining of angelic fashion in the form of a skirt made from a dental dam, humour was a part of the heavenly performance through which artists mediated the grave conditions of queer life.

63

Made several years later, St. Pelagius contains registers and remnants of these earlier angelic works and networks. The film stars the artists Del LaGrace Volcano and Hans Scheirl as St. Pelagius, both of whom were involved in the queer club-cum-art scene to which Boffin also belonged, although the landscape had already changed by 1997. Quim, the lesbian erotica magazine in which all three had published work, had folded in 1995, with the dyke nights Chain Reaction and Clit Club also closing sometime around the mid-1990s. The film’s angels also resemble their forebears visually: the wings of Boffin’s and Julien’s angels were attached with BDSM harnesses, a stylistic and practical decision repeated by Barker for his closing angelic ascension. However, even this short passage of time saw a change in circumstances. By 1997, when Barker made St. Pelagius, there were successful new combination therapies for managing HIV, which changed the direction of the epidemic in populations with access to the new treatment.64 Where for Prosser in Second Skins this change meant that he could not imagine AIDS having anything to do with trans life, Barker’s aesthetic genealogies enfolded the history of queer death into St. Pelagius’s transition.

64Angels featured in other works in TFF’s programme. These divine creatures were deployed with specific reference to their sex or, put more precisely, their sexed ambiguity. The title of one film by Clio Barnard, Hermaphrodite Bikini (The Gender of Angels), expresses succinctly the reason for the figurative utility of angels in imaging alternative genders. Maggie Jailler’s film A Nosegay tells the story of a fallen angel’s love for a hermaphrodite, each attracted to the other by their shared sexual non-dimorphism.65 This theological context is not mobilised, or at least not explicitly, in the work of Julien and Boffin, but St. Pelagius certainly draws on these associations, not least because, at the climax of the film—its conclusion—the angels come to represent a horizon of gendered transformation in an imaginative excess of normativity. The medieval held specific value for St. Pelagius’s trans imaginary, which, rather than expressing the achievement of sanctified sexual ecstasy through Christian iconography, maps the hagiographic genre onto the transition narrative to arrive at the ecstasy of being properly, and divinely, sexed.

65The Miracle of Cinema

Putting aside these queer connections momentarily: St. Pelagius, as a film organised around a stylised hagiography, would appear at first to fall under Prosser’s definition for a “transsexual narrative”, a claim strengthened by the film grounding its medieval story in documentary footage and personal disclosures by the performers. Barker’s description of the film as a creative documentary situates it within claims about realism, performed in St. Pelagius through its use of verité-style footage following each performer during quotidian acts of everyday life and labour: eating a Mr. Whippy ice cream on a visit to the seaside, kissing at studio parties in boy drag, hosing developer off photographs outside in the garden, preparing a Sunday roast, shooting testosterone into each other’s buttocks, loafing about the streets of London. There is a faithfulness to this “home movie” aesthetic and an intimacy that carries over into the accompanying voiceovers, where Simo, Levi, Del, Hans, and Svar provide a self-narration, a similarly “authentic” expression of individual subjectivity and self-determination typical of trans biographical accounts.66 The familiar genre conventions lend trans life the legibility and reality that Prosser finds in autobiographical texts—testosterone shots are incorporated into the practice of daily life and represented through the same visual language used to depict other acts of material subsistence (fig. 7).

66

In St. Pelagius’s hagiographic tableaux, however, this legibility breaks down. Each performer’s staging of a moment from St. Pelagius’s life is wrapped in allegory, made obscure by a lack of context. Without any dialogue, the story is told through exaggerated gestures and visual effects. When Simo, as St. Pelagius, first puts on his dead father’s vest, a flash of white light illuminates the screen and he raises his arms in awe. When Del is kneeling on the ground in prayer, a crash of thunder on the soundtrack and lines of lightning (scratched directly into the image) suddenly interrupt the saint’s contemplation (fig. 8). In wonder, Del clutches a newly grown beard, before beginning to brush dark dye through the wispy hair. Miraculous bodily transformation is dramatised through cinematic techniques, including jump cuts hidden in bursts of pyrotechnics and interventions on the surface of the film. These illusionistic effects recall the spectacular transformations of early “trick cinema”, and place these episodes in a realm of unreality and fantasy rather than documentary.67 Radical Deviance’s review of Barker’s film, published in 1998 in its reflection on the previous year’s festival, praised it for “avoid[ing] what have become TS [transsexual] cliches”, while noting that the work “leav[es] us with that age old question: is there identity beyond performativity?”68 Hagiography as a form with different narrative conventions and allowances presents a challenge to Prosser’s emphasis on autobiography as the definitive transsexual mode of self-realisation.

67

These “tricks” use the techniques of cinema to perform the miraculous transformations that are genre conventions and theological necessities in hagiographies, sanctifying the transformations of gender transition through spectacular enactment. The general narrative structure of hagiography follows the saint’s journey through corporeal suffering to a seat in the kingdom of heaven, a narrative consistent with classic trans narratives, featuring a linear transition from suffering to salvation although with a slightly different ending (beatification is dependent on the saint’s death rather than surgical rebirth).69 Again, St. Pelagius uses the magic of cinema to stage this final act. At the end of Barker’s film all five performers, adorned with their BDSM angel wings, unite to ascend upwards over a blush-pink sky strewn with hand-drawn stars. Their faces are alight with a silly joy as they perform their angelic roles, their arms outstretched like children pretending to be aeroplanes and their hands clasped in exaggerated mimicry of piety (fig. 4). Their joy, while embodied, is not bodily—the angels are translucent, coloured by the sky that shines through their torsos. Barker’s angels transform the death of St. Pelagius from a terminal reality to stage ascension as a trans desire to leave the body behind.

69What does it mean for transgender studies, then, if St. Pelagius ends on an image of angelic ascension and de-realisation, where transness is abstracted into a visual allegory, a visual allegory that draws on queer references, no less? What does it mean to consider this desire for immateriality through the material conditions that shape the content and distribution context of St. Pelagius as a work of British experimental film-making in a queer tradition, as a work produced in the late 1990s after the introduction of effective HIV treatment, as a work screened in the context of a cash-strapped transgender festival involved in newly defining a politics of gendered liberation?

Allegory’s immateriality has been problematic for trans studies. The use of allegory, as Emma Heaney identifies in modernist literature and queer theory, has been a tool of exceptionalism by which writers consign transsexuality to metaphor, making transition a material impossibility.70 Prosser’s narrative theory of transsexuality similarly critiqued strategies of metaphorising. Central to his criticism of Judith Butler was their use of the term “transubstantiation” as a synonym for gender transition. Prosser reads transubstantiation for its Catholicism, as a term both “performative and constative” that literalises Christ’s body through the metaphor of the Eucharist.71 He summarises Butler’s argument, as it appears in their reading of Jennie Livingston’s 1990 documentary Paris Is Burning, as: “Venus’s [Xtravaganza] desire is here said to represent a transubstantiation of gender in that her transsexuality is an attempt to depart from the literal materiality of her sexed and raced body.”72 Transubstantiation is used in Butler’s text to describe the naivety of Xtravangaza’s belief that she could actually change her sex.

70Regardless of his criticism, Prosser agrees with Butler on one crucial point. They both make the same assumption that transubstantiation does not actually take place. But what if you do believe, perhaps perversely, against all the odds? Would that faith look something like Prosser’s own paradoxical articulation of trans existence on his return to Second Skins, where, even though he deems transsexuality impossible, he still believes that it—and he—exist? Before, I called Prosser’s conclusion a grim joke. Perhaps there is something more to this statement: religion and humour share a similar kind of relation to the truth.

A Moment of Levity

Instead of autobiography, St. Pelagius makes the case for comedy as the ultimate trans genre. Both forms share many of the same features: a confessional mode, the risk of personal vulnerability, and the importance of a satisfying ending. Yet comedy’s specific bodiliness—as manifest in spontaneous laughter, visceral cringe, embarrassing pratfalls—of both the comic object and the person laughing (who may indeed be the same) speaks more to the experience of gender transition than autobiography’s controlled narrative voice. For Lauren Berlant, the disconnect inherent in the mind–body relation is definitively slapstick, a comedy of errors between how the subject wants to behave and what their body can do.73 Berlant’s definition of slapstick is clearly trans-coded—it would be hard to find a bigger disjuncture between one’s desires and one’s body than that of gender transition. The exaggerated shock and awe displayed by all five performers in St. Pelagius when witnessing their transformations as the titular saint further ham up this disconnect.

73Slapstick’s usefulness, the reason why it remains funny and not simply tragic, is its ability to bridge this disjuncture, or at least hold two things (such as Prosser’s impossible existence) to be true at once. The joke’s effectiveness relies not on its representativeness but on the success of its landing. Comedy’s pay-off is its ability to describe a vision of the world as inconsistent with itself, which allows one to acknowledge moments of reality that feel unreal, beyond belief. This divergence holds one at a critical distance from one’s conditions of existence—there does not have to be a totalising resolution, an alignment with expectations, or a fully explainable world view.74 More important than reality is collective buy-in: do we get the joke or not? Patricia Gherovici and Manya Steinkoler use the physical comedy of Wile E. Coyote and Buster Keaton to argue that “the comic hero never stops not dying … Comedy euthanises death’s lethality”.75 The same can be said of Jason Barker’s angels who similarly stage the duality of death’s finality and its generic repetitiveness. By ending the film with a scene that cuts between five performers, who have been brought together for the first time as identical angels making their way to heaven, St. Pelagius multiplies death for comic effect. The whole film leads up to this dramatic pay-off, making trans death the punchline to St. Pelagius’s gender transition. Yet Barker’s choir of impossibly resurrected angels use humour to side-step death’s painful realism in a suspension of disbelief that can hold the mutually exclusive proposition of one’s impossibility and one’s continued existence together. As the historian Jules Gill-Peterson explains in her conversation about trans comedy with writer Charlie Markbreiter, laughing at one’s own pain can mean taking a critical stance on the pain’s source: It’s so bad, it’s funny. The difference is a change in perspective: laughing back means refusing to take what the world throws at you lying down. In Gill-Peterson’s words: “Going from a life where the joke’s on you and I have no control, to one where I choose to make the joke on me? That’s being trans, baby”.76

74Unlikely as it may seem, hagiography resembles comedy in being a genre that describes extraordinary realities. Hagiography’s saintly exceptionalism describes an intervention in the question of what is real; that is, the saint proves their sanctity through the fact that their miraculous work is typically unbelievable, outside the bounds of the real world as commonly observed. The saint performs a kind of negative role, defining what is not typical of the world under normal physical laws. The historian C. Libby argues that a similar structure of negation can be read into the medieval hagiographies of “transvestite saints”. Libby names this new interpretative methodology of negation “the apophasis of transgender”, drawing from the rhetorical devices and theological methods that were contemporary with these saints’ lives. Apophatic theology, Libby writes, “confronts the dilemma of how to describe the ineffable and transcendent divine using a series of negations as explanatory mechanisms”.77 Isn’t this also the function of self-deprecating humour, an attempt to explain the ineffable through strategies of self-negation? Like apophasis, humour is a critical stance from which to describe something that seems impossible to describe. Viewed through this apophatic structure of negation, then, St. Pelagius’s documentary realism bleeds into literalising trans impossibility under a cis view of the world. In the film, imagining one’s future self can be nothing but an allegory of unreality, the future trans self as not-real, angel, dead but not. The diaphanous translucence of St. Pelagius’s angels demonstrates their insubstantial reality, a transcendent flight that attempts to leave the body and the world behind. Depersonalisation and dissociation are transformed from familiar trans affects to aesthetics or, more accurately, anaesthetics, as the angelic figures float above the terrestrial lives of the performers shown in the documentary segments.78

77Although the angelic versions of Simo, Levi, Del, Svar, and Hans fly from their earthly lives, they do not sever their relations to those they leave behind. Comedy, but perhaps especially trans comedy, is social. Berlant argues that comedy is intersubjective: in laughing, we not only work out what is acceptable for us all to laugh at but also work out our relationships to each other, our distinctions, and the things we hold in common.79 (Even laughing at someone else is an attempt to put distance between yourself and them. Accusations of humourlessness are accusations of being anti-social, of not getting along; this is why transphobes complain that trans people cannot take a joke.80) This sociality is what, in Berlant’s words, tilts comedy “toward the affirmation of the attachment to life” even when mediating death.81 St. Pelagius’s angels are not only goofing for each other or for the congregation of Sisters and supplicants watching them ascend from below, but also for the audience gathered together in the Lux Centre, sat watching the screening at TFF.

79Through this sociality, comedy holds both the allegorical and the material together. Jokes are rarely funnier when imitated in art than when spontaneously offered up in everyday life.82 Gherovici and Steinkoler argue this point too using, fittingly, religious language which can help make sense of St. Pelagius’s interweaving of comedy and faith, especially in the context of TFF. In pointing out Lacan’s comparison between comedy and the Catholic communion mass, they describe how humour operates on the level of the material, as “transubstantiation not of the body of Christ, but of a signifier that makes reality a little more palatable”.83 This use of transubstantiation’s comic affect refracts back onto Butler and Prosser’s comments, offering an alternative to the stalemate of queer versus trans. To answer my earlier question: considering St. Pelagius’s angelic immateriality through the material conditions that shaped the content and distribution of Barker’s film refocuses trans theory on a different kind of reality from that presented by queer performativity or transsexual autobiography. Uniting the comedy set, the communion mass, and the film festival screening is the audience’s collective suspension of disbelief, holding a dual awareness of the conditions that produce transness as an impossibility and of one’s actual existence in spite of this.

82The stakes of this position are as clear in the present as they were at the end of the twentieth century. The existence of TFF, Prosser’s project of instituting trans studies, and Barker’s footage reminds us that the project of trans theoretical and cultural production is materially underpinned. TFF’s premature closure and Prosser’s difficulties also remind us that this kind of public project is precarious. One inadvertent legacy of transgender’s coalitionary intent has been an abstraction of the goals of transgender politics away from the specific aim of gender transition, that is, the aim of securing the material conditions (medical care, employment, education, public services, community) that enable people seeking transition to transition.84 Therefore, any strategy must affirm access to the material conditions for trans life and thought as a goal while facing continuing legislative attempts to render transition, and public forms of transgender life, impossible.

84Conclusion: Hate Your Gender? Try Leaving It Behind

In Lesbians Talk Transgender, Zachary Nataf reflects on the remarkable possibilities for self-transformation at the end of twentieth century. He uses as an example an anecdote reported in the men’s magazine GQ: “In San Francisco people are talking about radical plastic surgery which could redesign the human body; for example, rearranging the muscles of the back to give yourself angel’s wings”.85 Nataf’s straightforward presentation of this story without comment makes it a challenging statement to interpret. Are we to take this as evidence of medical fact or as a wishful fantasy? In transgender studies, where the only aesthetic option is reality, with all else a queer performance, we don’t have many other options. But what if it weren’t all that serious? Humour encourages a belief in the unbelievable—“Really”, we scoff, “I can’t believe that actually happened to you”. But, of course, the joke is it really did.

85Starting with the collective mourning that opened the First International Transgender Film & Video Festival, and ending with the angelic ascension of St. Pelagius the Penitent, this article has located an alternative set of coordinates for transgender studies that reveals the contingency of the field’s trajectory. In providing a historical account of TFF and the festival’s attempts to define transgender, I have pointed to a British trans theoretical and cultural project that has been overlooked in contemporary trans studies. Jay Prosser’s presence at TFF allowed me to elaborate the differences between cinema and scholarship as discursive sites for producing knowledge about trans life, and to indicate how the different circumstances of these sites shaped both the kinds of knowledge produced and its continued availability for the field of trans studies. To complicate the picture of early trans studies offered when only Prosser’s Second Skins is cited, I returned to Prosser’s own rejoinder to his text to pursue a close reading of St. Pelagius that is also an attempt to rethink the project of trans studies itself. By inflecting hagiography’s alternative narrative epistemology with light-hearted humour, St. Pelagius transforms the proximity of trans life to death with a comic finale involving an angelic ascension that perversely literalises the trans desire to leave one’s gender behind. Even while Barker’s angels are flying high, comedy’s sociality returns St. Pelagius’s angels to the scene of TFF, to the precarity of its public presence and of those acts of gender transition shown in St. Pelagius’s documentary sections.

On Friday, 31 October 1997, the audience at TFF sat for the second feature of the evening’s double billing, Ed Wood’s Glen or Glenda (1954). Kate More called Wood’s semi-autobiographical drama at the festival “one of the worst ever made”. Despite her poor review, More did not write off Wood’s work but instead argued that it was a must-see for the transgender community: “this film is a true test of TG [transgender] people who really want to pass muster. For to be truly empowered we need to desensitise ourselves to the abject, and if mtfs can watch Glen or Glenda without cringing, and instead laugh at themselves, then yes, we’ve arrived”.86 The test of Glen or Glenda is a test of humour. For More, the project of trans politics needs more than representation. Having good politics means being able to have a good laugh.

86Acknowledgements

Research for this article started during my AHRC-funded doctorate, while its completion was enabled by a postdoctoral fellowship at the Institute for Advanced Studies in the Humanities at the University of Edinburgh. I am grateful to both the Arts and Humanities Research Council and the University of Edinburgh for their support. I would like to thank my supervisor, Amy Tobin, whose advice and guidance have been crucial throughout, and Jason Barker, Annette Kennerley, Kate More, and Diane Morgan for their invaluable help and generosity, for providing access to archival material, and for permission to share images of their work. Finally, I am grateful to all at British Art Studies, and to the anonymous readers, for their help in improving this article.

About the author

-

Evelyn Whorrall-Campbell is a postdoctoral research fellow at the Institute for Advanced Studies in the Humanities at the University of Edinburgh. They completed a PhD in film and screen studies at the University of Cambridge in 2024, with a thesis on trans theory and artistic practice in 1990s Britain. In 2025 they began a postdoctoral fellowship at the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art. Recent publications include articles for Art Monthly, world picture, and Cambridge Literary Review.

Footnotes

-

1

For a discussion of mourning as the predominant mode by which trans life is publicly articulated, see Cameron Awkward-Rich, The Terrible We: Thinking with Trans Maladjustment (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2022), 144. ↩︎

-

2

Zachary I. Nataf, “Founder’s Statement”, in The First International Transgender Film and Video Festival (London: Transmutation, 1997), programme, [4]. Although it was widely thought that Candy died of cancer (see “Candy Darling Dies; Warhol ‘Superstar’”, New York Times, 22 March 1974), rumours have circulated that her lymphoma had been caused by carcinogenic hormones acquired on the black market (Francesca Passalacqua, “Candy Remembered”, in My Face for the World to See: The Diaries, Letters, and Drawings of Candy Darling, Andy Warhol Superstar, ed. Jeremiah Newton, Francesca Passalacqua, and D. E. Hardy (Honolulu: Handy Marks, 1997), 20). ↩︎

-

3

For a critique of the necropolitical value of trans life, see C. Riley Snorton and Jin Haritaworn, “Trans Necropolitics: A Transnational Reflection on Violence, Death, and the Trans of Color Afterlife”, in The Transgender Studies Reader Remix, ed. Susan Stryker and Dylan McCarthy Blackston (New York: Routledge, 2022), 66–76. ↩︎

-

4

Cáel M. Keegan, “Getting Disciplined: What’s Trans* about Queer Studies Now?”, Journal of Homosexuality 67, no. 3 (2018): 384–97; Andrea Long Chu and Emmett Harsin Drager, “After Trans Studies”, TSQ 6, no. 1 (2019): 103–16. ↩︎

-

5

Although the TV/TS Centre at 2–4 French Place was less than a ten-minute walk away, no relationship was fostered with TFF. It appears that the TV/TS Centre highly prized its independence (see Yvonne Sinclair, “2–4 French Place”, Yvonne Sinclair: The Story of the TV/TS Group (blog), https://yvonnesinclair.co.uk/pages/2%20French%20Place.html. ↩︎

-

6

Kate More and Mijka Scott, “Welcome to the Festival”, in The First International Transgender Film and Video Festival (London: Transmutation, 1997), programme, [1]. ↩︎

-

7

More and Scott, “Welcome to the Festival”, [1]. ↩︎

-

8

More and Scott, “Welcome to the Festival”, [1]. ↩︎

-

9

Sandy Stone, “The Empire Strikes Back: A Posttranssexual Manifesto”, Camera Obscura 10, no. 2 (29) (1992): 168. ↩︎

-

10

Zachary I. Nataf, Lesbians Talk Transgender (London: Scarlet Press, 1996). ↩︎

-

11

Susan Stryker, “1990s: The Shape of Trans to Come”, Aperture Magazine, Fall 2022, https://issues.aperture.org/article/2022/03/03/1990s-the-shape-of-trans-to-come. ↩︎

-

12

Horak argues that the TFF, unlike the two other major transgender film festivals founded in the 1990s (Toronto’s Counting Past 2 and San Francisco’s Tranny Fest), was less opposed to existing lesbian and gay film festivals (Laura Horak, “Representing Ourselves into Existence: The Cultural, Political, and Aesthetic Work of Transgender Film Festivals in the 1990s”, in The Oxford Handbook of Queer Cinema, ed. Ronald Gregg and Amy Villarejo (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2022), 511–40). ↩︎

-

13

Zachary I. Nataf, “Directors’ Statement”, in The Second International Transgender Film and Video Festival (London: Transmutation, 1998), programme, 9. ↩︎

-

14

For the only discussion of Radical Deviance in scholarship see Nat Raha, “Queer Memory in (Re)Constituting the Trans Lesbian 1970s in the UK”, in Queer Print in Europe, ed. Glyn Davis and Laura Guy (London: Bloomsbury, 2022), 211–12. ↩︎

-

15

Shona Fearon, ed., Transgender in Film: Selected G&SA Film Reviews (London: Gender and Sexuality Alliance, 2000). ↩︎

-

16

Kate More and Diane Morgan, “G&SA Loses Funding”, Radical Deviance 2, no. 3 (1996): 91–92. ↩︎

-

17

The author discussed this definition in a personal conversation with Annette Kennerley on 12 January 2023. As co-founder of TFF, Kennerley shared how the use of “transgender” in the name of the festival had given rise to debate among fellow organisers. In the United Kingdom the sociologist Richard Ekins used “trans-gender” as a collective category when he set up the Trans-Gender Archive at the University of Ulster in 1986 (David Valentine, Imagining Transgender: An Ethnography of a Category (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007), 262n2). See also Richard Ekins and Dave King, The Transgender Phenomenon (London: SAGE, 2006), 13–20. ↩︎

-

18

More and Scott, “Welcome to the Festival”, [1]. ↩︎

-

19

Valentine, Imagining Transgender, 33. ↩︎

-

20

Leslie Feinberg, Transgender Warriors: Making History from Joan of Arc to Dennis Rodman (Boston: Beacon Press, 1996), p. x. ↩︎

-

21

Kate Bornstein, Gender Outlaw: On Men, Women, and the Rest of Us (New York: Routledge, 1994), 134–35, quoted in Nataf, Lesbians Talk Transgender, 30. ↩︎

-

22

First International Transgender Film and Video Festival, 31–33. ↩︎

-

23

Chu and Drager, “After Trans Studies”, 103; See also Keegan, “Getting Disciplined”; Kadji Amin, “Whither Trans Studies? A Field at a Crossroads”, TSQ 10, no. 1 (2023): 54–58. The problematic relation between queer and trans theory was identified in the 1990s by Jay Prosser and Viviane K. Namaste (Jay Prosser, Second Skins: The Body Narratives of Transsexuality (New York: Columbia University Press, 1998); Viviane K. Namaste, Invisible Lives: The Erasure of Transsexual and Transgendered People (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000)). ↩︎

-

24

Susan Stryker, “Transgender Studies: Queer Theory’s Evil Twin”, GLQ 10, no. 2 (2004): 212–15. ↩︎

-

25

More and Scott, “Welcome to the Festival”, [1]. ↩︎

-

26

Kasimirovitch, “You Don’t Know Dick”, Radical Deviance 3, no. 2 (1998): 8. ↩︎

-

27

First International Transgender Film and Video Festival, 8–9. ↩︎

-

28

First International Transgender Film and Video Festival, 8. ↩︎

-

29

Prosser, Second Skins, 173. ↩︎

-

30

Prosser, Second Skins, 6. For the term “posttranssexual”, see Stone, “The Empire Strikes Back”. ↩︎

-

31

Judith Butler, Bodies that Matter: On the Discursive Limits of “Sex” (London: Routledge, 2011). ↩︎

-

32

Matt Lee, “The Grifting of Three Papers on Trans Theory”, Radical Deviance 2–3, nos. 5–6 (1997–98): 174. ↩︎

-

33

References to Prosser’s work include Cassius Adair, Cameron Awkward-Rich, and Amy Marvin, “Before Trans Studies”, TSQ 7, no. 3 (2020): 307–10; Awkward-Rich, The Terrible We, 103, 108, 120–21, 130; Che Gossett and Eva Hayward, “Trans in a Time of HIV/AIDS”, TSQ 7, no. 4 (2020): 537–41; Emma Heaney, The New Woman: Literary, Modernism, Queer Theory, and the Trans Feminine Allegory (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 2017), 225–26; Keegan, “Getting Disciplined”; Chu and Drager, “After Trans Studies”, 110; Gayle Salamon, Assuming a Body: Transgender and Rhetorics of Materiality (New York: Columbia University Press, 2010), 28–42, 63. ↩︎

-

34

First International Transgender Film and Video Festival, 12. ↩︎

-

35

First International Transgender Film and Video Festival, 12. ↩︎

-

36

I am using the term “idealisation” here in the Freudian sense, taking my lead from Kadji Amin’s use of “idealisation” and “de-idealisation” from his reading of Judith Butler. See Judith Butler, “Afterword”, in Butch/Femme: Inside Lesbian Gender, ed. Sally R. Munt and Cherry Smyth (London: Cassell, 1998), 225–30; Kadji Amin, Disturbing Attachments: Genet, Modern Pederasty, and Queer History (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017), 8–10. ↩︎

-

37

Magnus Berg, “Expanding Trans Cinema through the Tranny Fest Collection”, JCMS: Journal of Cinema and Media Studies 61, no. 2 (2022): 181–87. ↩︎

-

38

Jason Barker, “Films and Writing”, Jason Barker—Filmmaker and Writer (blog), https://www.jasonebarker.com. ↩︎

-

39

Prosser, Second Skins, 22. ↩︎

-

40

My gloss on Prosser’s statement here is indebted to the work of Gossett and Hayward on transgender studies’ difficulty looking at HIV/AIDS (Gossett and Hayward, “Trans in a Time of HIV/AIDS”, 535). ↩︎

-

41

Valentine, Imagining Transgender, 4; Kate More, The Manual for Transgendered Sex Workers (London: Radical Deviance, 1996). ↩︎

-

42

Nataf, “Founder’s Statement”, [4]. ↩︎

-

43

Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Epistemology of the Closet (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990), 37, quoted in Prosser, Second Skins, 22. ↩︎

-

44

Awkward-Rich, The Terrible We, 103. ↩︎

-

45

Raha, “Queer Memory”; TGirlsonFilm and Jaye Hudson, Tranny Central: The History of G.L.F’s Transsexual and Transvestite Group (1971–1975) (London: PageMasters, 2024). ↩︎

-

46

Nataf, Lesbians Talk Transgender, 6. ↩︎

-

47

Kate More, “Housekeeping”, Radical Deviance 1, no. 1 (1996): 2. ↩︎

-

48

Adair, Awkward-Rich, and Marvin make the same point in relation to contemporary US educational institutions (Adair, Awkward-Rich, and Marvin, “Before Trans Studies”, 306–20). ↩︎

-

49

Adair, Awkward-Rich, and Marvin, “Before Trans Studies”, 230–47. ↩︎

-

50

Julia Knight and Peter Thomas, Reaching Audiences: Distribution and Promotion of Alternative Moving Image (Bristol: Intellect Books, 2012), 217–59. ↩︎

-

51

The next large-scale transgender cultural project in the United Kingdom was Transfabulous. Founded by Serge Nicholson and Jason Barker, Transfabulous was a month-long annual festival of transgender art, film, and performance that was held in London from 2006 to 2012. ↩︎

-

52

Jay Prosser, Light in the Dark Room: Photography and Loss (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2005). ↩︎

-

53

Jay Prosser, “A Palinode on Photography and the Transsexual Real”, a/b: Auto/Biography Studies 14, no. 1 (1999): 71–92. ↩︎

-

54