The Resurrection of the Body

The Resurrection of the Body: The Temple of Mithras in the City of London

By Altair Brandon-Salmon

Abstract

In 1954 a Roman temple dedicated to Mithras was discovered in a bombsite in the City of London. The bust of Mithras that was uncovered drew national attention, with thousands coming to see the excavated remains. The history of the site, stretching from Roman London to its contemporary transformation into Bloomberg’s European headquarters, testifies to the force of money in shaping urban space, while the sculptures discovered there demanded a cultic response, then and now, from their audience. The bust of Mithras became both a sign of the war dead, otherwise suppressed in official discourse, and a challenge to the idea that cities were ordered, controlled environments. Finally, Mithras emerges as a counterpoint to the growing financial capital that underpinned post-war London and presents a cyclical, ritualised conception of history that integrates the Roman origins of the city into its twentieth-century manifestation.

Eruption

After the Second World War, bodies were disturbed and brought out of the ground in London. Not just the bodies of the 30,000 people who had perished during the Blitz, but stone bodies found amid the mud as the foundations to new buildings were excavated. In 1954 The Sunday Times published a photograph on its front page of a Roman bust of Mithras, the god at the centre of the Mithraic cult, discovered in a building site in the City of London (fig. 1). The sculpture was part of a trove of finds, including many other statues, that were found on the site: archaeological remains buried like dead bodies.

To unearth the traces of the past often involves disturbing the dead, whether they are bodies or sacred effigies. The photograph of Mithras would perhaps have reminded readers of the recent dead, those killed at home or slain overseas. The gap between the living and the dead had thinned to the point of almost inevitable contact during the war. Millions were killed, crossing the final threshold to the other world. Yet, as Elizabeth Bowen wrote, the dead “made their anonymous presence … felt through London” by “their absence”.1 Instead of inhabiting the houses and streets, they were now underground. There was no escape from those buried beneath: contemporary London is a city built on a mass grave.

1

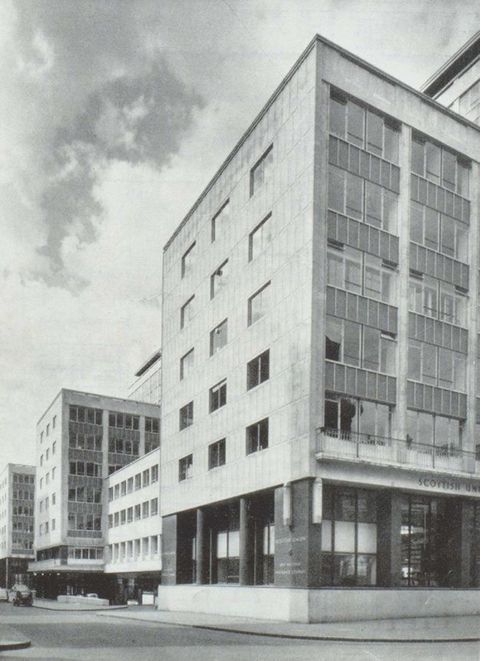

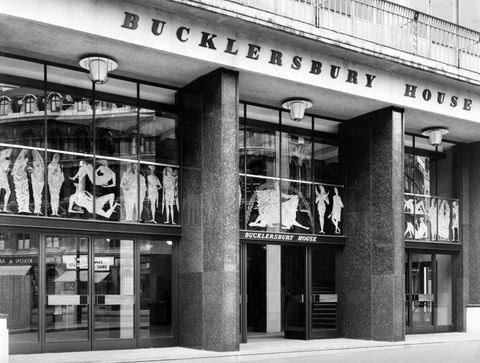

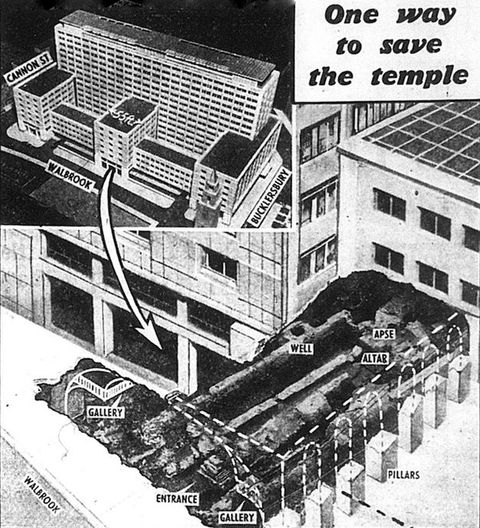

Mithras was discovered on Walbrook in the City of London, within sight of the Bank of England and Mansion House (fig. 2). The street had been destroyed on 10 May 1941 by high explosives, which had levelled the warren of 500 businesses working from Mansion House Chambers, built in 1882.2 During the construction of Bucklersbury House, developed by the Legenland Property Company as the first large-scale office block to be built in London since the end of the war, a Roman temple was discovered on 18 September 1954 (fig. 3).3 The clearing of the site was paused; a team of archaeologists led by William F. Grimes, director of the London Museum, was given sixteen days to excavate the Temple of Mithras. It proved to be the most significant discovery of Roman sculpture in Britain during the twentieth century. Eighty thousand people queued to see the muddy remains.4 But Legenland needed their new office block. The builders returned, and the temple was carved up piece by piece and finally relocated in 1962 over 300 feet away on Queen Victoria Street, on top of a carpark. In 2010 the financial services company Bloomberg bought Bucklersbury House and demolished it in favour of a new European headquarters (fig. 4). The temple was once again relocated, now to the basement of the building, within 40 feet of the original site, so as not to disturb delicate remains that had not been found in 1954 (fig. 5).5

2

The temple was a remnant of a continent-spanning empire, the scale of which seemed small compared to the Second World War, whose international dimensions were made plain in newspapers and cinemas such as the Monseigneur News Theatre in Piccadilly, which showed newsreels twenty-four hours a day.6 The breadth of the conflict was unique, but Britons were already used to thinking in global terms. The British Empire was an imperial form of world-making that the Romans would have recognised. The city itself had been founded as a Roman colony between 50 and 55 CE.7 This imperial context helps explain why the Temple of Mithras excited such an extraordinary public reaction on its discovery and why the site has changed so much in the subsequent decades. To dig up the remains of a former empire’s most secret religion in the heart of London only seven years after Indian independence underlines how the temple appeared at a turning point in British history.

6The temple is approached here from three different angles: first, as a site of cultic power that speaks to the City’s mercantile identity; second, as a site that moves, the temple’s occupation of different spaces revealing the power of money to shape the urban environment; and, finally, as emblematic of a post-war world, where the victims of the Blitz were transmuted into representations of deities. Together, these perspectives crystallise the Temple of Mithras into a symbol of the cycles of construction, destruction, and reconstruction marking the history of London. Of the sculptures recovered, the bust of Mithras inhabits multiple temporalities and spaces at once, demanding a break with linear conceptions of time.8

8The post-war City of London, so badly damaged during the Second World War, was subjected to “comprehensive redevelopment”.9 The burned-out acres of warehouses and neoclassical buildings were going to be replaced by a new landscape of offices. The City would be at the heart of a new empire just as Britain’s colonial empire was being dismantled by decolonisation movements: a financial empire based on money, markets, and trade. Capital can be thought of as money over time, accumulating interest until the principal sum is primarily composed of this temporally accrued wealth. The urban environment of capital can also be tenacious, as over time Londinium became the City of London, millennia of capital inscribed in its stone. For Fredric Jameson, “ground rent and value in land are both essential to the dynamic of capitalism … capital is oriented towards the expectation of future value: and thus with one stroke the value of land is revealed to be intimately related to the credit system, the stock market and finance capital generally”.10 As a consequence, space itself is deeply embedded within capitalism, indeed as a foundational component in money’s reproduction of itself. The architecture that takes root in this land becomes an intermediary between capital and its future returns, often attempting to obscure the very purpose the building is dedicated to serving.

9In post-war London, the manipulation of capital needed a new form of architectural expression, of sleek buildings with the latest amenities, although it was not until the 1960s that the city allowed defiantly modernist developments. In that sense, Bucklersbury House represented the first hesitant steps towards an archetypal architecture of capital: a reinforced concrete frame with glazed walls and metal windows, what Herbert Wright has called a “modernist slab with wings”.11 The reconstruction of the City in the 1950s has been comprehensively chronicled by, among many others, Nicholas Bullock, Elain Harwood, and more critically, Owen Hatherley.12

11Yet these architectural histories have bracketed the discovery of the Temple of Mithras as purely an archaeological event. Similarly, exhaustive accounts of the temple found in the work of W. F. Grimes, John D. Shepherd, and most recently Susan M. Wright focus primarily on the excavation of Roman London. My aim here is to consider the temple as a palimpsest, where “the stages of erasure and reinscription coalesce together into a singular act”, so that the site simultaneously embodies multiple historical, architectural, and symbolic meanings.13

13What pulls these threads together is money. The merchants and veterans of the Roman Empire who established the temple in London were in many respects hardly dissimilar to the financiers and lawyers who were at the heart of Bucklersbury House or Bloomberg Europe. The Roman imperial economy was radically different from post-war London’s, yet money was central to both and temples, holy and profane, were built to facilitate the accumulation of wealth. There was in both eras a cult of money in London.

The term “cult” has many overtones, not the least of its meanings being the act of ritualised homage to the divine. A cult in a religious sense always carries within it the promise of doing something towards the figure of veneration.14 The temple’s design, along with its sculptural programme, demanded from its adherents certain forms of action. Upon the re-emergence of Mithras and other statues of deities in post-war London, the public accordingly changed their behaviour, treating the sculptures as emanations from another world.

14Cult

The Temple of Mithras was a sacred space. To understand it requires excavating Mithraism itself and how the temple’s architecture expressed a complex philosophical vision of the world. Mithraism was a Roman cult whose origins and meanings remain unknown; its theology was shrouded in secrecy, so most of what is known is based on archaeological remains. It gained popularity towards the end of the first century CE, although it dates back to at least the first century BCE. As a male-only cult, it was popular among the military, merchants, and Roman political elite.15 Temples dedicated to Mithras, called Mithraea by archaeologists, were founded across the empire, with over 100 sites known; there seems to have been a particular emphasis on the frontiers, where there was a substantial army presence. Unlike the contemporaneous rise in Christianity, Mithraism was not a populist religion but was reserved for dedicated initiates who had to pass through seven stages.16 Mithraea were usually small, compact rectangular buildings, with vaulted roofs and partly underground, reflecting the limited membership of the cult.17 There would be wall paintings, relief sculptures, and statues of Mithras and other crucial figures, and the windowless central space was lit with torches.18 With over 100 known examples across the Roman Empire, Mithraea were a well-established building type.19

15Mithraism went into decline after Constantine’s Edict of Milan in 313 CE, which established imperial tolerance of Christianity, and seems to have been extinguished sometime in the fourth century.20 The Roman Empire withdrew from London in the first decade of the fifth century CE and the city was only sparsely populated until it was refounded by Alfred the Great in 886 CE.21

20

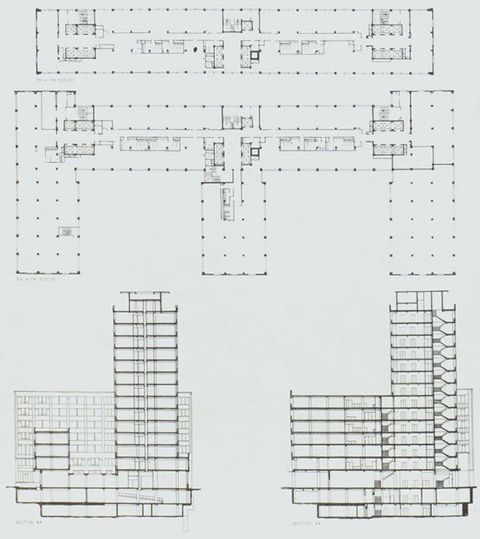

The London temple was constructed around 240 CE as an extension of a private property, possibly belonging to Ulpius Silvanus, a veteran of the Second Augustan Legion.22 It was built in a valley to the east of the Walbrook stream, along one of the city’s main roads.23 The temple was laid out on an east–west orientation, with a single nave reached by descending steps, and narrow aisles on either side.24 There was a screened narthex to prevent non-members from seeing the main chamber, and a semi-circular apse at the west end, very near the stream, where a statue of Mithras would have stood. Mithraea did not have windows and were barrel-vaulted; the Walbrook temple had seven columns on either side separating the nave, which could have seated thirty people, from side aisles. It was an intimate space 59 feet long and 26 feet wide, and was illuminated only by torches (fig. 6). The walls were made of local ragstone, rendered in plaster and painted, supplemented by Roman brick and tiles, and the floors and benches were made of wood. The temple was continually altered because of subsistence in the marshy ground and perhaps because of a change in emphasis of the ritual. It ceased operation in the fourth century, when its stone was taken by Londoners, and the city rose up and swallowed the remains. By the time it was discovered, it lay 23 feet below street level.25 The remains themselves were between 1 and 2 metres high, with the apse at the west end the tallest remnant. After the Romans left Britain around 410 CE, the city was largely abandoned and its structures fell into ruin and were scavenged for building material.26 The Walbrook stream had been culverted around 1440, and the valley was built up over time, so the watercourse was no longer detectable in the city’s topography.27

22The temple represents the frustrations of antiquity: materially present yet intellectually hard to get at, a place of obscure belief and ritual. The Mithraic mystery creates a space for the unknown within London, the bombs having destroyed not just buildings but also the possibility of ever uncovering all of the city’s history.

Between 1941 and 1952 Walbrook was a bombsite (fig. 7). Fenced in by hoardings, it was a wasteland of weeds, flowers, and wild animals. Yet the archaeologist William F. Grimes knew this was an “unprecedented opportunity” that could transform the knowledge of Roman London.28 The city had never been properly excavated, but the swathes of bombsites and the slow process of rebuilding enabled him and his team to begin unearthing medieval and Roman London. Grimes was director of the archaeological wing of the Roman and Mediaeval London Excavation Council; the City Wall was retraced and a large Roman fort at Cripplegate discovered (now partially underneath the Barbican). The former Walbrook stream offered a promising site for cuttings. Grimes’s initial work started in 1952, as he tried to clear the bomb rubble from the double basements of the destroyed buildings with Audrey Williams and a small group of assistants. By the autumn of 1954, the builders for Bucklersbury House were ready to move into the site. It was on the last day of the dig, the morning of Saturday, 18 September, that a workman found a marble bust, the head of Mithras. Suddenly, Grimes realised that the fragmentary outline of a rectangular building that had been discovered was a Mithraeum.29

28A remnant changed everything. From a bombsite to a Roman ruin to now a temple, Mithras gave an identity to Walbrook that was both new and had always been there, waiting to be discovered. The cool gaze of Mithras is implacable, his eyes always looking beyond us, both boyish and aged at the same time. The smoothness of the marble suggests a perfection that lies beyond our own world. He could only be a god, erupting out of the dirt, defeating the amnesia of the living and refusing to stay anonymously dead. His vitality transcended the 1,500 years of burial and bent the political and economic forces of the City of London around him. Mithras was reborn.

The remains speak to the “cult of ruins”, which Andreas Huyssen sees as common to the cultures of northern transatlantic countries since the eighteenth century.30 One cult transplants another within the same space. Yet the Mithraic cult is an ambiguous force. Mithras was a lawgiver, a god of justice and order, an appropriate deity for the soldiers and merchants who were initiated into the cult.31 It would seem to be an apt temple to have been found within the City of London, yet its very presence challenged who was able to transform the post-war urban environment. Office blocks were the new secular temples being built in the 1950s. In their attempt to build over the destruction of the war, developers sought to displace older fragments of London. A cult implies obsession and veneration in equal measure, with idols providing a point of focus. For the initiates in the Roman temple, that was the statue of Mithras, but in post-war London, the idols were dispersed into the notes and coins that were hard to acquire.

30The cult of money in post-war London and its creation of a financed-based economy centred on the City led to the uncovering of the temple. Yet this money had its own history as the wealth accrued in Britain’s colonies. The Australian-born Aynsley Bridgland had been buying parts of the five-acre plot of land around Queen Victoria Street and Cannon Street since the late 1940s. Building was still limited by rationing, but Bridgland knew that, when restrictions were lifted, development would be enormously profitable. While he bided his time, Bridgland made his company, Legenland, the chief operator in South Africa, staunchly supporting apartheid. He was the post-war imperialist, a bald businessman in a three-piece suit, pugnacious, ruthless, and master of the new financial instruments.32

32The City’s architecture has been characterised historically by neoclassicism, the quotations from Rome constituting a dual assurance of power and permanence.33 Bridgland was suspicious of modernist architecture, unconvinced that it would be supported by traditional clients, and the initial plan put before the City of London in 1950 showed a building clad in Portland stone. The London County Council and the Royal Fine Art Commission, which advised on architectural and urban planning, criticised the design as “too bulky”.34 Bridgland’s architect, Owen Campbell-Jones, kept on redesigning the proposal, turning to a more modernist vernacular, and in 1953 it was finally approved.

33

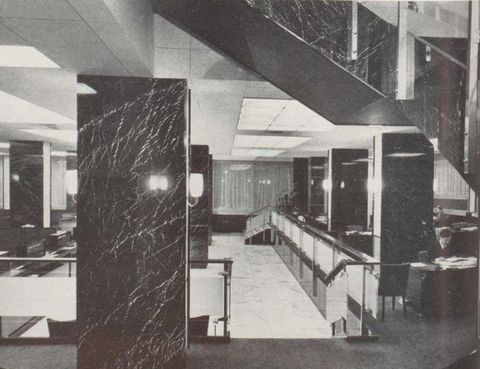

Campbell-Jones’s complex plan reflected the difficulties of the site, running along the narrow Walbrook between Queen Victoria Street and Upper Thames Street (fig. 8). Yet what the 2,000 people who worked there were doing was always meant to be hidden. Bucklersbury House’s eastern front along Walbrook could be seen only obliquely, with its fourteen-storey main spine stepped back from the street and connecting to three six-storey spurs that projected forwards. The facade of stone mullions and green panels interspersed between the curtains of glass hung on a steel frame to present a smooth, disarming screen.35 On the ground floor were pubs and restaurants, and below were a carpark, stores, and a mechanical plant: all the necessities of the modern office.36 Its cost of £4 million was much trumpeted in the press as the most expensive building under construction in London, a figure that generated its own political momentum.37 If the restless shift of facades denied the viewer a firm image of the building, it was inside that the luxurious finishings for Legal & General and the other tenants were revealed.38 For the Bankers Trust Company in the west wing, there was a public banking hall with white marble paving, dark Repen marble for the columns, and Indian laurel wood panelling (fig. 9).39

35

Campbell-Jones’s architecture for Bucklersbury House was stolidly glamorous, with no expense spared. It is architecture for London from the 1950s to be placed alongside the Shell Centre on the South Bank and John Lewis on Oxford Street. This was to be London’s future, where all the new ring roads and elevated highways would lead, a city powered by coal and nuclear power stations. Even if the empire was changing, London was still at the heart of money.

The cult of money can appear all dominant, but it can be superseded, at least temporarily, by other energies. The discovery of Mithras—not the temple structure itself, which had been unearthed earlier in the summer, but the bust—brought the enormous investment of Bridgland temporarily to a halt. The Telegraph reported the find, which was then picked up by The Sunday Times. On Sunday, 19 September, people started to visit the site, before the builders were to move in. Humphreys, the building contractors, decided to postpone the beginning of work to allow for a few extra days of excavation and to open the site in the evenings. On Monday, 10,000 people, and on Tuesday 15,000, queued into the night. By the following Sunday, 26 September, 35,000 people were queueing for 1½ miles to see the remains (fig. 10).40 Grimes, shocked by the public interest, later wrote that there was “an atmosphere of excitement amounting at times to … hysteria”.41 Working on the site in the rain and mud, as thousands of people passed by, Grimes, Williams, and the team continued to excavate the site. At the weekend, tobacconists and cafes opened, while newspaper hawkers went up and down the crowd. In opening up the earth, as William Thomson Hill observed, nineteen centuries of history was exposed, making visible “layer after layer of forgotten London”.42

40

The crowds had come out of curiosity and a sense that something unique was taking place, a slice of history that would be exposed for only a short time. They congregated not to pray but to bear witness to an older religion. On the evening of Sunday, 26 September, as darkness fell, Williams discovered a head of Minerva near where Mithras had been found (fig. 11). Williams carried it “triumphantly” along the queue of 1,000 people.43 The immaculate surface of the slightly smaller than life-sized marble reflects Minerva’s divine perfection. That the top of her head is missing its original diadem serves to emphasise the severity of her expression, her eyes looking beyond the viewer into another world. A photograph of the bust was on the front pages of the national papers the next day. Minerva—goddess of wisdom, justice, law, victory—was once again being processed through the streets of London.

43

Minerva as a sculpture imposes a distance between itself and the audience. Michael Fried described this gap as similar to “being distanced, or crowded, by the silent presence of another person”.44 The audience stands back to allow a space for this force to exist, which is recognised as being outside of themselves. To invoke Fried’s ideas about 1960s minimalist art may seem odd with reference to a head carved in Italy sometime between 130 and 190 CE.45 Yet Fried argues that the objects made by Donald Judd, Robert Morris, and Tony Smith, are “placed not just in [our] space but in [our] way”.46 Minerva would have been a full-length statue, her head turned to the right and looking slightly upwards. It acts as an intervention in space, a demand that people modulate their behaviour in response to Minerva’s presence. When the statue was in the temple, this would have been underlined by being painted so that it appeared both of and apart from the world, like an actor on the stage: an obvious fiction and resolutely real.

44If Minerva is viewed as anticipating the strategies of minimalist art, its effect on the crowds in 1954 becomes explicable, whereby people saw not just the representation of a god but a sign of the alterity of the Roman world that had been brought into the present. The sculpture was both “simultaneously approaching and receding” from the viewer, to use Fried’s phrase.47 Alexander Nagel has argued that ancient and medieval objects are central to the production of modernist art, so that artworks have multiple relationships with temporality, like an arrow shot through different “sheaths” of time.48 The rediscovery of the Minerva head resituated its meaning but did not unmoor it from its use as a cult statue. The cult had shifted through time from Mithras to the cult of ruins, and was never more potent than in London after the war, Minerva’s incompleteness testifying to the partiality of that which survives through history.

47Bucklersbury House, however, wanted to sidestep history. As a glass-and-stone box which could be reproduced serially through the arrangement of cubes in space, it was a design where, as Jane Stevenson puts it, “time has come to a stop”.49 This was architecture’s logical endpoint—nothing could go beyond this design language. Hence, John Hutton’s engraved glass above the entrances to Bucklersbury House, representing Roman legionnaires and gods (fig. 12).50 Here the past was used as ornament, with the temple becoming an advertisement for an office block. The building itself was never meant to appear as if it had its own history.51 Yet this self-delusion was far more fantastical than any Mithraic beliefs. Bucklersbury House was knocked down in 2010 to make way for Bloomberg’s European headquarters.52 No trace of it remains now except in photographs and plans.

49

The sculptures’ rediscovery was anticipated by their own theology. Central to Mithraism is the belief that Mithras was born from a rock and brought water from the stony ground by firing an arrow into it.53 All of Mithraism’s crucial scenes speak of transformation. Found at nearly all its temples is the Tauroctony relief, a scene representing Mithras slaying a bull, with ears of corn and clusters of grapes springing forth from the bull’s wounds, death metamorphosing into life.54 The Mithraeum, built to resemble a cave, was a space of rebirth for initiates, who were metaphysically transformed as they progressed through the seven grades. To enter a Mithraeum was not to step into a specific location but to be in an environment that contained and intensified the cosmos itself, a world where gods could be present and human transformation was possible.55 The Tauroctony, as found in the Walbrook, is to be interpreted, Roger Beck argues, as a vision “of genesis and apogenesis” (that is, souls entering and leaving heaven) (fig. 13).56 A Mithraeum was where the gap between the divine and the human was narrower, and could facilitate moving between these worlds.

53

This was underlined by theatrical rituals in the gloom of the temple, which used incense, water, food, and torches, sometimes hidden behind sculptures to make them seem momentarily alive.57 Beck called the scene of Mithras slaying the bull “a stage or scene against which the two principal players perform their parts”, the sculpture being seen as a re-enactment of the belief system’s ontology.58 Religion and theatre have always been intimately connected, and the representation of Mithras and the other gods still carries a call to action, as when Williams held up Minerva to the crowds upon its discovery.

57It was appropriate that the sculptures were reborn in a “mud patch” and theatrically presented to the audience who had queued to see them, for this is how cults are enacted.59 The temple is a stage that organises the viewer’s perceptions and the sculptures are actors, who demand an emotional response.60 Minerva was carved from a block of saccharoidal marble, probably from Carrara, Italy, as were many of the other sculptures discovered at the Mithraeum. But, more than a piece of stone, it is emblematic of a polytheistic world, where gods actively intervened in people’s lives and, in the right conditions, appeared to the faithful. Minerva’s rediscovery in 1954 has its own quality of the miraculous. As the onlookers gazed at the head, perhaps they too felt the presence of a foreign divinity.

59Motion

Buildings are not often thought of as being able to move. They are static shapers of space through which an individual can travel. Objects and decor may come and go, but the structure itself is seen as immobile and permanent. Yet buildings move vertically all the time—when they are constructed and when they’re destroyed—and London has a rich history of moving buildings horizontally, whereby houses and churches are shifted according to the pressures of politics and money. As Tim Anstey points out, movement is fundamental to architecture, and the suppression of this knowledge is itself an ideological manoeuvre to claim permanence for the current instantiations of political power in a spatial environment. These are actually always provisional and improvisatory, and build on previous regimes, whose fragmentary presence suggests that the status quo will, in time, also be relegated to the cemetery.61

61The Temple of Mithras has been in five different sites over the past seven decades, but that is not unique. The fifteenth-century merchant’s house Crosby Hall was moved from Bishopsgate in the City of London downstream to Chelsea in 1910 so that a bank could be built in its place. St. Mary Aldermanbury, designed by Christopher Wren after the Great Fire of London in 1666, was bombed in 1940. The diocese was reluctant to fund its restoration, so it was rebuilt at Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri, as a memorial to Winston Churchill.62 The constant demands of financial renewal, particularly in the City, lead to buildings being treated as movable objects, especially before the preservationist turn in the 1970s. This prioritised notions of authenticity in the built environment, a concept that had little traction in London after the war, when hundreds of buildings had to be rebuilt, often as a creative reinterpretation (the House of Commons Chamber and St. Bride’s, for example). Indeed, the war had underscored the notion that buildings could be fabricated in one place and constructed in another: prefabricated homes, factories, and schools proliferated, with 160,000 “Portal homes” (named after Lord Portal, the minister of works) made from 1944 onwards.63 The world was in a frenzy of motion during and after the war; it makes sense that buildings were not immune from these forces.

62What causes a building to move? The force of money, which in London has always been its raison d’être, the city founded by the Romans on the island’s largest river and so always dedicated to commerce.64 This emphasis on the profits of the present over the legacies of the past is reflected in how little Grimes had to go on for his excavation efforts in the city: an annual £2,500 grant from the Ministry of Works and a mere £550 in total from the Corporation of London.65 An economic history of the Walbrook site is the only way to explain the vicissitudes of what has occurred since a Roman temple was discovered there.

64Numbers have their own force. As an advertisement at the time went, “In Londinium they believed in Mithras; in London they believe in Shell”.66 Bridgland and Legal & General had a budget of £4 million for Bucklersbury House; by 1954, before the foundations had been laid, £1 million had already been spent.67 This was at the forefront of David Eccles’s mind when, as the minister of works, he visited the site on 20 September at the request of the prime minister, Winston Churchill. Bridgland’s budget meant that delays were expensive, running at £2,000 a day, and politically damaging.68 The government did not want to be seen to be impeding reconstruction. Churchill chaired a Cabinet meeting the next day dominated by Cold War politics, which covered France’s rejection of the European Defence Force and the Chinese threat to invade Taiwan, but the eighth item on the agenda was the temple.69 Eccles told the Cabinet, “The ruin is nothing much to see and none of the archaeologists I met on the site suggested we should stop the new building altogether … I do not recommend any action to preserve the remains”.70 The lead article in The Times on 20 September, which had excited Churchill’s attention, asked “why no arrangements could be made either to arch over the remains in a sort of crypt, or to remove them stone by stone for re-erection elsewhere”.71 Bucklersbury House was to have a double basement, extending down to the level of the temple’s remains. The developers did not want to lose the two-storey basement for parking and building services, nor the deep piling needed for the foundations due to the poor quality of the Walbrook subsoil.72 So the latter course of action proved to be the eventual compromise: the temple would be relocated.73 Building over the temple would, apparently, have cost £500,000, while moving it would cost only £10,000 (fig. 14).74

66

Bridgland, who had initially been reluctant to pause construction, announced on 28 September that he would reconstruct the temple on a nearby site, with his company paying the cost.75 This act of archaeological philanthropy, which saved the government from embarrassment, was rewarded with a CBE and later a knighthood, cementing Bridgland’s establishment credentials.76 By October, the temple had been broken up, not into carefully numbered stones, but into “masses as large as can be handled”.77 The remains were placed in the graveyard of the former St. John the Baptist upon Walbrook nearby, a church that had burned down during the Great Fire and not been rebuilt.78 One sacred ruin was left in the remains of another, the dead piled upon the dead. At some point, the temple’s stones were then moved to a builders’ yard in Surrey, to await its fate.79

75Buildings that move defy the standard categories of architecture, their fluidity defeating notions of stability and originality. In 1961, two years after the completion of Bucklersbury House, the temple was reconstructed on top of the entrance to the underground carpark, overlooking Queen Victoria Street (fig. 15). Neither Grimes nor the Ministry of Works was involved, and crazy paving was used for the flooring, while the different levels of the temple, which had shifted over the centuries, were “maltreated”.80 The restriction of the podium meant that the apse was not even fully reconstructed. Finished in 1962, over 300 feet from where it had originally been discovered, the temple stood, exposed for all to see—to see what exactly? A ruined Roman temple? A facsimile using the same material, with modern concrete added? There isn’t a language to describe buildings that shift in this way.

80

The values of authenticity and preservation in the built environment, which are central to organisations such as the National Trust and English Heritage in contemporary Britain, are relatively recent. In 1954 there was a debate on whether the temple needed to be kept at all. The historian C. E. Vulliamy, in a letter to The Times, wrote: “What remains of the Mithraeum is a ruin which does not possess any aesthetic value. What it does possess is an archaeological and historical value which … can be fittingly preserved by adequate survey and the recovery of the objects”.81 While there is now a consensus in Britain about preserving the archaeological and architectural past, particularly of structures built before 1800, such ideas were far from accepted in the 1950s. Even Grimes thought that discarding the actual temple, as long as the site was recorded, was no great loss.82 In a decade when cities were full of ruins and money was needed to restore Wren churches and build new highways, keeping the temple in situ was never considered a serious prospect. Bridgland enjoyed both “the glory as the promoter of the first glass box” in London and being the saviour of the temple.83 He died in 1966, a wealthy man, his legacy the reconstruction of the City in the new image of money: glass, marble, and smooth surfaces.84

81But cities don’t stop moving. The hectic building in the City after the deregulation of financial trading in 1986 dwarfed Bridgland’s efforts. Bucklersbury House, once the city’s tallest office building, was soon overshadowed by new tower blocks. Post-war commercial architecture still resides outside the realm of heritage, so Bucklersbury House was always vulnerable to the depredations of the commercial property market. By 2004, Legal & General wanted to redevelop the lucrative site. Jean Nouvel was commissioned to design a new Walbrook Square, with an office building nicknamed the Cloud as its centrepiece. Although planning permission was granted in 2007, the project was mired in delays. Norman Foster was brought in to work with Nouvel, and then took over the whole scheme. Bloomberg, the American financial services company that underpins the wealth of Michael Bloomberg, who at the time was mayor of New York City, bought the site from Legal & General in 2010.85 The temple had been given a Grade II listing by English Heritage in 2007, which meant that it now had statutory protection, unlike in 1954.86 As a consequence, the City Corporation required Bloomberg to reconstruct the temple as close as possible to the original site as a condition of demolishing Bucklersbury House. The new European headquarters for Bloomberg was completed in 2017, its cost never revealed, although it was speculated to be in the range of £1 billion.87 It makes the amounts Bridgland was dealing in look small in comparison. The mayor of London, Sadiq Khan, was on hand to open this new bauble for the capital alongside Michael Bloomberg, home to 6,700 employees and a vision of American money coming to Britain, in a twist on nineteenth-century New Yorkers seeking to buy cultural capital in London.

85

Bloomberg London is a new temple of money for London that chimes with the Temple of Mithras’s merchants and traders.88 Ten stories high, it takes up the whole triangular site, with a covered arcade retracing the Roman-era Watling Street (fig. 16). Three corners have been effectively cut off from the building to create a more fluid sense of space by Foster + Partners (a team of eleven architects worked on the building) and to avoid becoming a simple rectangle. The facade has a stone skeleton that marks out the recessed ground floor, the dominant middle section containing the offices, and the top stories, which are again recessed. The building is large, but the subtle setbacks and lack of sharp corners means that its public face is reserved. Within the stone mullions are bronze alloy fins and louvres that act as vents for the building, and placed inside the grid are the windows themselves. Claims by the Foster + Partners architect Kate Murphy that the exterior is classical in temperament seem overstated; the surface texture and colour (white and brown) is closer to postmodernism.89 Apart from a discreet glass door for the Temple of Mithras, no external architectural feature refers to the remains.

88Perhaps it is appropriate that the temple is once again hiding in plain sight, just as it would have done in the second century CE. It has been placed 23 feet underground, back at its original level, and 40 feet away from where it was discovered, in order to protect remains—including part of the narthex—that were uncovered when the foundations for the Bloomberg building were being excavated and have been left in situ.90 Visitors to the museum move through an atrium that contains a vitrine with 600 artefacts dug up in 1954 and in 2010 at the Walbrook, and then descend a narrow staircase into a room with a series of interactive displays giving an abbreviated history of the site. Another darkened staircase takes the viewer down, finally, to the temple. The remains are laid out, with a walkway floating above it, the reconstruction informed by Grimes’s original survey drawings and photographs. A sound and light show plays out on each visit, designed by Local Projects and Studio Joseph, to create a theatrical experience that, ironically, serves to conceal the temple itself.91 The mysteries of Mithraism are capitalised upon to present not Roman London but, more elusively, the obscurity of the past itself.

90The temple’s history points to the sheer difficulty of the past: it refuses ever to be destroyed or quietened. This is not true of all fragments of Roman London. It persists because it was a sacred space, continuing to hold the charge of a belief that caused people to change their behaviour. If we think of buildings as objects that can move—according to the pressures of religion, conflict, or money—the temple’s biography can be explained. It seems telling that capital in the post-war period in London was just as powerful a physical force as the Luftwaffe’s bombs in making buildings move. Yet it’s this very motion that has prevented the temple from being destroyed: buried, excavated, and now underground once again. The fluidity of the Roman stones enables it to carry a potent force that was made visible in 1954.

The Remains of Bodies

War is fragmentation. It cleaves limbs from bodies, slices holes through cities, scars survivors’ minds. There was no utopian harmony in London before the bombs, but there is no doubt that the Blitz ruined the city. Part of the horror of the bombing was the way it tore apart the human body, leaving limbs to be found in the rubble.

Press censorship (and self-censorship) meant that images of victims were not published in newspapers. Instead, photographs proliferated of sculptures torn apart by high explosives, from effigies of the Knights Templar in the Temple Church to Lee Miller’s photograph Revenge on Culture, which shows a statue of a nude woman covered in debris. Sculptures became the visual expression of bodies destroyed.

When the head of the Mithras was reproduced in The Sunday Times in 1954, it was both a marble bust and a head. This image excited the attention of the crowds and drew them towards Walbrook. Yet what is commanding about this head? An image of a god, an image of a young man, and fundamentally a fragment of a body. When a marble neck was found on 21 September, it slotted neatly into the head just as a dead body is reconstructed.92 In post-war Britain, these statues were slippery objects, representing ancient gods and the invisible dead who were all around.

92Theodor Adorno wrote that “the fragment is that part of the totality of the work that opposes totality”.93 The sculptures discovered at the temple, including those of Mercury and Serapis (a river god), and a figure of a Genius, resist unity and wholeness—the watchwords of post-war London, when the city was being reconstituted as more ordered, coherent, and planned. This is because the sculptures had been deliberately ruined millennia earlier. In the fourth century CE, the temple’s dedication shifted to the cult of Bacchus, and the old sculptures of Mithras and the other gods were not destroyed but carefully decapitated and buried beneath the temple in two pits, and covered over with roof tiles.94 Mithras was no longer being worshipped but he was not to be discarded. He was buried, in the knowledge that the tombs of gods and emperors are seldom left in peace.

93Mithras anticipated this future through the multivalence of his carved expression. Originally, the head would have belonged to a Tauroctony. He would have been looking backwards over his shoulder, away from the bull, his eyes cast towards heaven. He is not delighting in the killing of the bull, nor is he distraught, for he is an agent of divine purpose.95 Yet there is a dreaminess on his face, his eyelids drooping a little too far, which makes him seem as though he is escaping from the world. Is that a quiver in the supple lips, the flash of teeth in the shadow of the open mouth—or is it a trick of the light? Nagel writes that “inanimateness and uncanny presence” are central to sculptures that stage an encounter with the viewer, the art not so much a physical fact as existing in the tremulous space between object and subject.96 That’s how Mithras operates, forging a transhistorical interruption where the head forces us to consider him not as a remnant of an oblique past but as here before us in the present, dissolving the comfortable distance that we assume exists between then and now.

95Mithras wears his characteristic Phrygian cap, a soft conical hat that in the eighteenth century was revived in Revolutionary France and America as a sign of liberty.97 Mithras, however, is no embodiment of freedom but rather a figure who ensures the continuation of the world. In the relief of Mithras Tauroctonos found at the temple, a snake and a dog drink the blood of the slain bull, which represents the cycle of life and death. The torchbearers Cautes and Cautopates stand to the left and right, symbols of light and darkness.98 Mithras died, was buried, and now rises again in modern London. Memories are confused but, at some point during the queue to see the temple, the frustrated crowd tried to storm the barricade around the site and were fought back by the police.99 Grimes dismissively suggests that people had come out of “sensationalism”.100 In a sense he was right, for they were there not to learn about the evolution of the Walbrook valley, but to experience the sensation of looking at the remains of another world. The sensuality of the sculpted head, its promise of animacy, is a spectral presence: all that has been destroyed, and will come back, perhaps more powerful than before.

97The temple gave physical shape to the sense that London’s current iteration was temporary. The Blitz had shown that buildings, monuments, and streets were not immutable but could be changed in a moment. The temple was a reminder that London was once like Calcutta, the capital of a colony, distant from the centre of imperial power. National narratives, particularly during and immediately after a war, often emphasise destiny and inevitability: victory, in the British rhetoric of the 1940s, was assured. This is a comforting illusion. Mithras’s wisdom suggests different cycles of time—through death comes regeneration, not unlike how London was rebuilt in the post-war period—and provides a different vision of the city. The alterity of the past acts as the true freedom, for it enables variant futures to be imagined. When everything is a mosaic of fragments, new additions can always be made.

If the temple itself could be moved by the power of money, then the sculptures have an agency that allows them to sidestep the forces of capital. They were placed on view in the Royal Exchange in 1955, where they had been accessioned into the rarefied category of art, to be seen with respect and protected from being touched.101 Subsequently, they were displayed in carefully lit vitrines in the Museum of London within the Barbican.102 The shift from religious idol to art object did less harm than might be expected to the sculptures, for the Mithraic fragments were treated as significant holders of meaning, to be cleaned, preserved, and restored where possible. What the heads and arms lost in their translation from ruin to museum was their resemblance to the bomb victims of London. If gods could look like those killed during the Blitz, they served as an oblique memorial to a loss that otherwise went unseen. The war dead found their representation, not in grand memorials in Hyde Park, but in stony remains found in pits on a building site. Mithras was a counter-memorial to the Blitz.

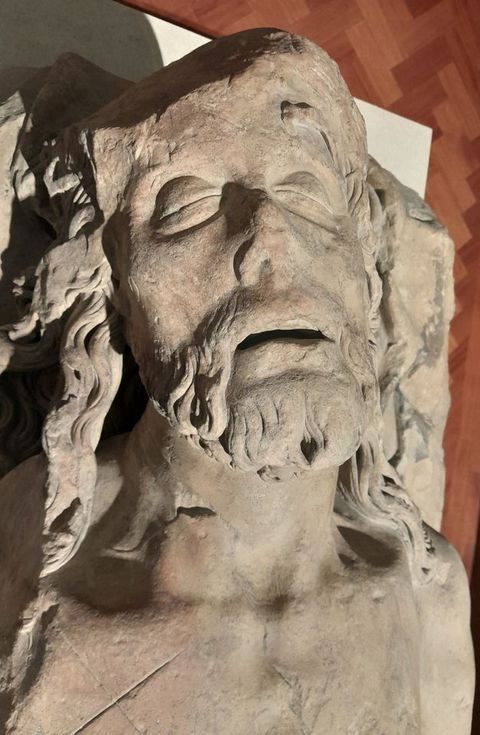

101Mithras was not the only dead body found in London in 1954. On Ironmonger Lane, across the road from Walbrook, the Worshipful Company of Mercers were rebuilding their seventeenth-century hall, which had been destroyed in 1941. On 30 April, workmen clearing the chapel vault discovered a life-size limestone effigy of the dead Christ buried five feet below the floor (fig. 17).103 It was an astonishing discovery of a major work of pre-Reformation sculpture, probably carved in the early sixteenth century. Subsequently publicised in The Times, the statue was displayed at the Royal Exchange before being placed in the Mercers’ new hall, designed by Noel Clifton.

103

The sculpture had probably been buried during the late 1540s after Edward VI ordered the Mercers (dealers in luxurious fabrics such as silk and velvet) to remove images from their chapel, which they had taken over from the dissolved monastic hospital church of St. Thomas of Acon.104 Like the Temple of Mithras, changing religious and political contexts led to the burial of sculptures. The Dead Christ’s moment of suppression coincided with the political destruction of buildings in England, and its rediscovery came in the aftermath of another wave of political violence. The sculpture marked the passing of one form of Christianity (Catholicism) in favour of another (Protestantism). The sculpture is a remnant of another way of life, highly ritualised, colourful, visceral.

104The sculpture foregrounds the Crucifixion’s violence, with long tails of blood seeping from Christ’s wounds. He lies on a shroud and three rough biers in the agonising days between his death on the cross and his resurrection. This is a vision of humanity abandoned, the sense of aloneness that Jesus on the cross expressed at the very end: “Jesus cried with a loud voice, saying, Eli, Eli, lama sabachthani? that is to say, My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?”105

105To feel deserted at the moment of greatest pain shows that even Jesus had an instant of wavering faith. The sculpture represents a godless world, before the miracle of resurrection. Here, within Christianity, is the moment when there is no beyond.106 The sculptor has carved Christ’s mouth slightly open, his nose already collapsed, eyes closed, pain frozen across the shrunken face. A thorn cuts into the brow of his forehead. The chips and scarring of the stone only add to the violence done to the body. The Dead Christ is fragmentary: the top of his head, the whole of his left arm, his hands, and his feet are missing. This may be due to deliberate iconoclastic attack or to the act of burial.107 More mysteriously, a large, deeply incised X lies across Jesus’s right breast (fig. 18). The impulse that led to marking the sculpture thus now lies beyond knowledge, but it serves as a sign: X marks the spot. This is the origin point of the world, desecrated and then destroyed.

106

The sculpture was originally painted, the mantle in purple, the loincloth in white, and the body a naturalistic flesh tone. When it was discovered, traces of red could still be seen on Christ’s tongue and a reddish brown in the hair.108 While it’s impossible to know where the statue was placed in the chapel, it was carved to be seen in the round, so that worshippers could circle the effigy and bear witness to Jesus’s suffering; the sculpture’s verisimilitude would have heightened the viewer’s spiritual encounter. While moving around the sculpture, they would have read three carved Latin inscriptions, including a quotation from St. Paul’s epistle to the Philippians: “he humbled himself, and became obedient unto death, even the death of the cross”.109 Three drops of blood flowing from Christ’s wounds separate the words. Christians must be faithful to Christ as Christ himself was faithful to his fate.

108Joan Evans, director of the Society of Antiquaries, and Norman Cook, keeper of the Guildhall Museum, compared the sculpture to Hans Holbein’s The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb (1520–22) when they published the discovery in The Times (fig. 19).110 For Julia Kristeva, Holbein’s painting established the lacuna of death: “A depressive moment: everything is dying, God is dying, I am dying”.111 The Mercers’ sculpture performs a similar metaphysical manoeuvre, where the death of a man is also the death of God. Only the promise of salvation prevents total collapse. Both the painting and the sculpture embody the idea that every murder restages the murder of Christ. To kill is to destroy the world. It seems right, then, that the Dead Christ should have been found in a bombsite.

110

There was in the pre-Reformation church the cult of the Five Wounds (hands, feet, and body), which focused on the injuries Christ suffered. According to Richard Williams, “Prayers were said and masses dedicated to the wounds in the hope of spiritual help and protection”.112 The sculpture of the Dead Christ, both in its original form and in its damaged, recovered state, restages this violence within the very stone itself, becoming a cult object. Its dismemberment is intensely moving—in the sense that it forces the audience to react.

112It is appropriate that both Mithras and the Dead Christ were found within the heart of London, for cemeteries, as Michel Foucault pointed out, were historically within the walls of urban environments up until the eighteenth century.113 You could not have a church without its cemeteries; indeed, a number of cemeteries remain in the city, despite their attendant churches having been lost to the Great Fire or to the Blitz. The cult of the dead was central to the experience of London until the Victorian transformation of the whole city, but the suppression of burial places always threatened to be undone.114 In 1954 the Mercers’ Hall Christ and Mithras each recast their surrounding environments and transformed them into spaces that break with linear time and interrupt the continuity of the city with an ideological counterpoint.

113These sculptures contain their own death and rebirth, despite their different religious systems. They are the true symbols of post-war London, a city of ash and dust that would be made anew by architects such as Owen Campbell-Jones and Chamberlin, Powell and Bon. The cyclicality of London’s destruction is part of the temple and of the Dead Christ. Within the different levels of the temple’s remains are the layers of rebuilding and collapse of Roman London, while the biers holding Christ are stained red, either from the flames of the Great Fire or from the Blitz. It is in the ground that the past is buried (be it bodies or stone) and where the future can be discovered, and the earth itself shows that London is a city where the dead can be resurrected.

London is a city of constant change, where new forms of architecture are constantly being tried, leading to a conglomeration where no single era dominates but instead the eras interweave with one another. On Walbrook can be found the entire history of London and its determining forces. Out of the ground came a Roman temple whose sculptures have the power to summon up another vision of the city, while acting as reminders of the destruction of bodies that had so recently occurred in London and across the world. Money took material shape in the post-war city with the new office blocks of developers such as Aynsley Bridgland, possessed of the same force to move buildings as high explosive bombs.

The temple and the head of Mithras anticipated, through their emphasis on theatre and cyclical patterns of time, the changes that would be wrought, the stones carrying their own kind of wisdom. The public response to Mithras showed the hunger for an experience of the past that was part of the present, and to participate in a ritual that renewed Roman London while creating a different kind of war memorial. The thousands of people who queued into the night saw that the dead could rise again. The past would not be forsaken.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Alexander Nemerov and Amir Eshel for first encouraging me to think about the resonant ruins of Mithras. Baillie Card and Martin Myrone have been an enormous help in improving the article, as were the vital contributions of two anonymous peer reviewers.

About the author

-

Altair Brandon-Salmon is a lecturer in Civic, Liberal, and Global Education at Stanford University. His scholarship has been published in Art History, Art Journal, and the Oxford Art Journal. He is a guest curator for Projects Twenty Two and has been a curator for the Sheldonian Theatre and Campion Hall.

Footnotes

-

1

Elizabeth Bowen, The Heat of the Day (London: Reprint Society by arrangement with Jonathan Cape, 1950), 86. ↩︎

-

2

“Bloomberg through Time: 1666 to c 1900”, in Archaeology at Bloomberg, ed. Susan M. Wright (London: MOLA, 2017), 77. ↩︎

-

3

William Thomson Hill, Buried London: Mithras to the Middle Ages (London: Phoenix House, 1955), 25. ↩︎

-

4

Ralph Merrifield, The Roman City of London (London: Benn, 1965), 20. ↩︎

-

5

“Mithras Refound: 20th to 21st Century”, in Archaeology at Bloomberg, ed. Wright, 112. ↩︎

-

6

Matt Houlbrook, Queer London: Perils and Pleasures in the Sexual Metropolis, 1918–1957 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005), 59. ↩︎

-

7

Francis Sheppard, London: A History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), 13. ↩︎

-

8

It is not my intention to analyse every sculpture found at the Temple of Mithras in this article, but rather to highlight the works that resonated with the public at the time and to consider how they inflect the meaning of the site. ↩︎

-

9

Peter Ackroyd, London: The Biography (London: Random House, 2000), 957. ↩︎

-

10

Fredric Jameson, “The Brick and the Balloon: Architecture, Idealism and Land Speculation”, New Left Review 228, no. 1 (March–April 1998), https://newleftreview.org/issues/i228/articles/fredric-jameson-the-brick-and-the-balloon-architecture-idealism-and-land-speculation. ↩︎

-

11

Herbert Wright, “Bronzed and Breathing; Architects: Foster & Partners”, Blueprint 356 (February 2018): 126; see also Nicholas Bullock, Building the Post-war World: Modern Architecture and Reconstruction in Britain (London: Routledge, 2002), 256–57. ↩︎

-

12

Bullock, Building the Post-war World; Elain Harwood, Space, Hope, and Brutalism: English Architecture, 1945–1975 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press for Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, 2015); Owen Hatherley, Modern Buildings in Britain: A Gazetteer (London: Particular Books, 2022). ↩︎

-

13

Nadja Aksamija, Clark Maines, and Phillip Wagoner, “Introduction: Palimpsests: Buildings, Sites, Time”, in Palimpsests: Buildings, Sites, Time, ed. Nadja Aksamija, Clark Maines, and Phillip Wagon (Turnhout: Brepols, 2017), 9. ↩︎

-

14

“Cult (n.)”, Oxford English Dictionary, DOI:10.1093/OED/1043563032. ↩︎

-

15

John D. Shepherd, The Temple of Mithras, London: Excavations by W. F. Grimes and A. Williams at the Walbrook (London: English Heritage, 1998), 223. ↩︎

-

16

Shepherd, The Temple of Mithras, 223–24. ↩︎

-

17

“Mithras Refound: 20th to 21st Century”, in Archaeology at Bloomberg, ed. Wright, 95, 101. ↩︎

-

18

“Mithras Refound: 20th to 21st Century”, in Archaeology at Bloomberg, ed. Wright, 101. ↩︎

-

19

“Mithras Refound: 20th to 21st Century”, in Archaeology at Bloomberg, ed. Wright, 101. ↩︎

-

20

W. F. Grimes, The Excavation of Roman and Mediaeval London (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1968), 108. ↩︎

-

21

“Bloomberg through Time: c AD 48 to c AD 410”, in Archaeology at Bloomberg, ed. Wright, 43. ↩︎

-

22

The Mithras Tauroctonos found in 1889 on Walbrook has a dedication to Ulpius Silvanus and is likely to have come from the temple. Shepherd, The Temple of Mithras, 173. ↩︎

-

23

Grimes, The Excavation of Roman and Mediaeval London, 92. ↩︎

-

24

See Simon Bradley and Nikolaus Pevsner, London 1: The City of London, The Buildings of England (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1997), 584–85; and Susan Wright, ed., Archaeology Bloomberg, 83. ↩︎

-

25

“Mithras Refound: 20th to 21st Century”, in Archaeology at Bloomberg, ed. Wright, 101–5. ↩︎

-

26

“Bloomberg through Time: c AD 410 to the Mid 17th Century”, in Archaeology at Bloomberg, ed. Wright, 47. ↩︎

-

27

James Drummond-Murray and Jane Liddle, “Medieval Industry in the Walbrook Valley”, London Archaeologist 10, no. 4 (Spring 2003): 88. ↩︎

-

28

Thomson Hill, Buried London, 12. ↩︎

-

29

Grimes, The Excavation of Roman and Mediaeval London, 231. ↩︎

-

30

Andreas Huyssen, “Nostalgia for Ruins”, Grey Room 223 (Spring 2006): 7. ↩︎

-

31

Grimes, The Excavation of Roman and Mediaeval London, 116. ↩︎

-

32

Oliver Marriott, The Property Boom (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1967), 75, 195. ↩︎

-

33

Bradley and Pevsner, London 1, 127–28. ↩︎

-

34

“Bucklersbury House; Architect: O. Campbell-Jones”, Builder, 2 January 1959, 9. ↩︎

-

35

Bradley and Pevsner, London 1, 584. ↩︎

-

36

“Bucklersbury House”, Builder, 11–12. ↩︎

-

37

Shepherd, The Temple of Mithras, 17. ↩︎

-

38

Marriott, The Property Boom, 76. ↩︎

-

39

“Offices, including a Banking Hall for the Bankers Trust Company, Bucklersbury House, Queen Victoria Street, City of London; Architect: O. Campbell-Jones”, Architecture and Building, May 1959, 197. ↩︎

-

40

Merrifield, The Roman City of London, 19. ↩︎

-

41

Grimes, The Excavation of Roman and Mediaeval London, 232. ↩︎

-

42

Thomson Hill, Buried London, 37. ↩︎

-

43

“Temple Gives Up Another God”, Daily Mail, 27 September 1954, 1. ↩︎

-

44

Michael Fried, “Art and Objecthood”, in Art and Objecthood: Essays and Reviews (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998), 155. ↩︎

-

45

Shepherd, The Temple of Mithras, 167. ↩︎

-

46

Fried, “Art and Objecthood”, 154. ↩︎

-

47

Fried, “Art and Objecthood”, 167 (emphasis original). ↩︎

-

48

Alexander Nagel, Medieval Modern: Art Out of Time (London: Thames & Hudson, 2012), 23. ↩︎

-

49

Jane Stevenson, Baroque between the Wars (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018), 137. ↩︎

-

50

“Bucklersbury House”, Builder, 14. ↩︎

-

51

Stevenson, Baroque between the Wars, 137. ↩︎

-

52

Herbert Wright, “Bronzed and Breathing”: 126. ↩︎

-

53

“Mithras Refound: 20th to 21st Century”, in Archaeology at Bloomberg, ed. Wright, 95. ↩︎

-

54

Manfred Clauss, The Roman Cult of Mithras: The God and His Mysteries, trans. Richard Gordon (Abingdon: Routledge, 2017), 79–80. ↩︎

-

55

Roger Beck, Beck on Mithraism: Collected Works with New Essays (London: Routledge, 2019), 72. ↩︎

-

56

Beck, Beck on Mithraism, 289. ↩︎

-

57

“Mithras Refound: 20th to 21st Century”, in Archaeology at Bloomberg, ed. Wright, 95. ↩︎

-

58

Beck, Beck on Mithraism, 289. ↩︎

-

59

Lisa Benjamin, “Remembering the 1954 Discovery”, Oral History Archive, London Mithraeum Bloomberg Space, 10 November 2014, MP3 audio, 28:11 mins., https://www.londonmithraeum.com/oral-history/. ↩︎

-

60

Sigrid de Jong, “Staging Ruins: Paestum and Theatricality”, Art History 33, no. 2 (April 2010): 348. ↩︎

-

61

Tim Anstey, Things that Move: A Hinterland in Architectural History (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2024), 11. ↩︎

-

62

Peter J. Larkham, “Developing Concepts of Conservation: The Fate of Bombed Churches after the Second World War”, Transactions of the Ancient Monuments Society 54 (2010): 23. ↩︎

-

63

Angus Calder, The People’s War: Britain 1939–1945 (London: Pimlico, 1992), 499. ↩︎

-

64

Sheppard, London, 17. ↩︎

-

65

Marriott, The Property Boom, 75–76. ↩︎

-

66

Mollie Panter-Downes, “Bacchus in Londinium”, New Yorker, 30 October 1954, 78. ↩︎

-

67

Shepherd, The Temple of Mithras, 17. ↩︎

-

68

Panter-Downes, “Bacchus in Londinium”, 78. ↩︎

-

69

Shepherd, The Temple of Mithras, 18. ↩︎

-

70

Sir David Eccles to the Cabinet, CAB 1129/70, C.(54)294, 21 September 1954, Copy no. 59, reproduced in Shepherd, The Temple of Mithras, 18–19. ↩︎

-

71

“A Temple for Destruction?”, Times, 20 September 1954, 7. ↩︎

-

72

“Bucklersbury House”, Builder, 12. ↩︎

-

73

Shepherd, The Temple of Mithras, 1. ↩︎

-

74

Grimes, The Excavation of Roman and Mediaeval London, 233. ↩︎

-

75

Shepherd, The Temple of Mithras, 24. ↩︎

-

76

Marriott, The Property Boom, 76. ↩︎

-

77

“Moving the Temple of Mithras”, Times, 11 October 1954, 6. ↩︎

-

78

Bradley and Pevsner, London 1, 462. ↩︎

-

79

Marriott, The Property Boom, 76. ↩︎

-

80

Grimes, The Excavation of Roman and Mediaeval London, 234. ↩︎

-

81

C. E. Vulliamy, “Letters: Roman Temple in London”, Times, 25 September 1954, 7. ↩︎

-

82

“Work Halted on Roman Temple”, Times, 21 September 1954, 8. ↩︎

-

83

Marriott, The Property Boom, 75. ↩︎

-

84

See Marriott, The Property Boom, 75; and Bradley and Pevsner, London 1, 128. ↩︎

-

85

Herbert Wright, “Bronzed and Breathing”: 126. ↩︎

-

86

See “Mithras Refound: 20th to 21st Century”, in Archaeology at Bloomberg, ed. Wright, 91; and “Temple of Mithras”, Historic England, https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1391846?section=official-list-entry. ↩︎

-

87

Isabelle Priest, “Written in Stone; Architects: Foster & Partners”, RIBA Journal 124, no. 12 (December 2017): 25. ↩︎

-

88

Shepherd, The Temple of Mithras, 223. ↩︎

-

89

Herbert Wright, “Bronzed and Breathing”: 131. ↩︎

-

90

“Mithras Refound: 20th to 21st Century”, in Archaeology at Bloomberg, ed. Wright, 105. ↩︎

-

91

Herbert Wright, “Bronzed and Breathing”: 138. ↩︎

-

92

Shepherd, The Temple of Mithras, 19; Frances Faviell, A Chelsea Concerto (London: Dean Street Press, 2016), 105. ↩︎

-

93

Theodor W. Adorno, Aesthetic Theory, trans. Robert Hullot-Kentor (London: Bloomsbury, 2013), 93. ↩︎

-

94

“Mithras Refound: 20th to 21st Century”, in Archaeology at Bloomberg, ed. Wright, 105. ↩︎

-

95

Jocelyn M. C. Toynbee, Art in Roman Britain (London: Phaidon Books, 1962), 142. ↩︎

-

96

Nagel, Medieval Modern, 92. ↩︎

-

97

“Mithras Refound: 20th to 21st Century”, in Archaeology at Bloomberg, ed. Wright, 95. ↩︎

-

98

Shepherd, The Temple of Mithras, 172. ↩︎

-

99

Shepherd, The Temple of Mithras, 14. ↩︎

-

100

Grimes, The Excavation of Roman and Mediaeval London, 235. ↩︎

-

101

Thomson Hill, Buried London, 177. ↩︎

-

102

In 2022 the Museum of London closed its Barbican site in advance of its relocation to the former West Smithfield market building, which is scheduled to be completed by 2026. ↩︎

-

103

Joan Evans and Norman Cook, “A Buried Statue of Christ”, Times, 19 May 1954, 7. ↩︎

-

104

Richard Williams, “Reformation”, in Art under Attack: Histories of British Iconoclasm, ed. Tabitha Barber and Stacy Boldrick (London: Tate Publishing, 2013), 68. ↩︎

-

105

Matthew 27:46 (KJV). ↩︎

-

106

Julia Kristeva, Black Sun: Depression and Melancholia, trans. Leon S. Roudiez (New York: Columbia University Press, 1989), 113. ↩︎

-

107

Williams, “Reformation”, 68. ↩︎

-

108

Joan Evans and Norman Cook, “A Statue of Christ from the Ruins of Mercers’ Hall”, Archaeological Journal 111 (1955): 170–71. Subsequent cleaning by the Guildhall Museum removed any traces of paint that had survived. Conversation with Jane Ruddell, company historian, The Mercers’ Company, 20 April 2023. ↩︎

-

109

Philippians 2:8 (KJV). The Latin inscription on the sculpture reads: “HVMILIAVIT SEMETIPSVM FACTUS OBEDIEVS VSQUVE AD MORTTEM: MORTEM AVTEM CRVCIS. Pavlvs Epts Ad Philippens”. Thomson Hill, Buried London, 161. ↩︎

-

110

Evans and Cook, “A Buried Statue of Christ”, 7. ↩︎

-

111

Kristeva, Black Sun, 130. ↩︎

-

112

Williams, “Reformation”, 69. ↩︎

-

113

Michel Foucault, “Of Other Spaces”, trans. Michiel Dehaene and Lieven De Cauter, in Heterotopia and the City: Public Space in a Postcivil Society, ed. Michiel Dehaene and Lieven De Cauter (London: Routledge, 2008), 18. ↩︎

-

114

Foucault, “Of Other Spaces”, 19. ↩︎

Bibliography

Ackroyd, Peter. London: The Biography. London: Random House, 2000.

Adorno, Theodor W. Aesthetic Theory. Translated by Robert Hullot-Kentor. London: Bloomsbury, 2013.

Aksamija, Nadja, Clark Maines, and Phillip Wagoner. “Introduction: Palimpsests: Buildings, Sites, Time”. In Palimpsests: Buildings, Sites, Time, edited by Nadja Aksamija, Clark Maines, and Phillip Wagoner, 9–22 Turnhout: Brepols, 2017.

Anstey, Tim. Things that Move: A Hinterland in Architectural History. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2024.

Architecture and Building. “Offices, including a Banking Hall for the Bankers Trust Company, Bucklersbury House, Queen Victoria Street, City of London; Architect: O. Campbell-Jones”. May 1959, 196–99.

Beck, Roger. Beck on Mithraism: Collected Works with New Essays. London: Routledge, 2019.

Benjamin, Lisa. “Remembering the 1954 Discovery”. Oral History Archive. London Mithraeum Bloomberg Space. 10 November 2014. MP3 audio, 28:11 mins. https://www.londonmithraeum.com/oral-history/.

Bowen, Elizabeth. The Heat of the Day. London: Reprint Society. By arrangement with Jonathan Cape, 1950.

Bradley, Simon, and Nikolaus Pevsner. London 1: The City of London. The Buildings of England. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1997.

Builder. “Bucklersbury House; Architect: O. Campbell-Jones”. 2 January 1959, 8–14.

Bullock, Nicholas. Building the Post-war World: Modern Architecture and Reconstruction in Britain. London: Routledge, 2002.

Calder, Angus. The People’s War: Britain 1939–1945. London: Pimlico, 1992.

Clauss, Manfred. The Roman Cult of Mithras: The God and His Mysteries. Translated by Richard Gordon. Abingdon: Routledge, 2017.

Daily Mail. “One Way to Save the Temple”. 28 September 1954, back page.

Daily Mail. “Temple Gives Up Another God”. 27 September 1954, 1.

de Jong, Sigrid. “Staging Ruins: Paestum and Theatricality”. Art History 33, no. 2 (April 2010): 334–51.

Drummond-Murray, James, and Jane Liddle, “Medieval Industry in the Walbrook Valley”. London Archaeologist 10, no. 4 (Spring 2003): 87–94.

Evans, Joan, and Norman Cook. “A Buried Statue of Christ”. Times, 19 May 1954, 7.

Evans, Joan, and Norman Cook. “A Statue of Christ from the Ruins of Mercers’ Hall”. Archaeological Journal 111 (1955): 160–80.

Faviell, Frances. A Chelsea Concerto. London: Dean Street Press, 2016.

Foucault, Michel. “Of Other Spaces”. Translated by Michiel Dehaene and Lieven De Cauter. In Heterotopia and the City: Public Space in a Postcivil Society, edited by Michiel Dehaene and Lieven De Cauter, 13–29. London: Routledge, 2008.

Fried, Michael. “Art and Objecthood”. In Art and Objecthood: Essays and Reviews, 148–72. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998.

Grimes, W. F. The Excavation of Roman and Mediaeval London. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1968.

Harwood, Elain. Space, Hope, and Brutalism: English Architecture, 1945–1975. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press for Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, 2015.

Hatherley, Owen. Modern Buildings in Britain: A Gazetteer. London: Particular Books, 2022.

Historic England. “Temple of Mithras”. https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1391846?section=official-list-entry.

Houlbrook, Matt. Queer London: Perils and Pleasures in the Sexual Metropolis, 1918–1957. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005.

Huyssen, Andreas. “Nostalgia for Ruins”. Grey Room 223 (Spring 2006): 6–21.

Illustrated London News. “Modern London Discovers Roman London—and Queues to Visit It in Thousands: Aspects of the Unique Mithras Temple in the Heart of the City”. 225, no. 6024 (2 October 1954): 543.

Jameson, Fredric. “The Brick and the Balloon: Architecture, Idealism and Land Speculation”. New Left Review 228, no. 1 (March–April 1998). https://newleftreview.org/issues/i228/articles/fredric-jameson-the-brick-and-the-balloon-architecture-idealism-and-land-speculation.

Kristeva, Julia, Black Sun: Depression and Melancholia. Translated by Leon S. Roudiez. New York: Columbia University Press, 1989.

Larkham, Peter J. “Developing Concepts of Conservation: The Fate of Bombed Churches after the Second World War”. Transactions of the Ancient Monuments Society 54 (2010): 7–34.

Marriott, Oliver. The Property Boom. London: Hamish Hamilton, 1967.

Merrifield, Ralph. The Roman City of London. London: Benn, 1965.

Nagel, Alexander. Medieval Modern: Art Out of Time. London: Thames & Hudson, 2012.

Panter-Downes, Mollie. “Bacchus in Londinium”. New Yorker, 30 October 1954, 78–95.

Priest, Isabelle. “Written in Stone; Architects: Foster & Partners”. RIBA Journal 124, no. 12 (December 2017): 24–30.

Sheppard, Francis. London: A History. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Shepherd, John D. The Temple of Mithras, London: Excavations by W. F. Grimes and A. Williams at the Walbrook. London: English Heritage, 1998.

Stevenson, Jane. Baroque between the Wars. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018.

Thomson Hill, William. Buried London: Mithras to the Middle Ages. London: Phoenix House, 1955.

Times. “Moving the Temple of Mithras”. 11 October 1954, 6.

Times. “A Temple for Destruction?” 20 September 1954, 7.

Times. “Work Halted on Roman Temple”. 21 September 1954, 8.

Toynbee, Jocelyn M. C. Art in Roman Britain. London: Phaidon Books, 1962.

Vulliamy, C. E. “Letters: Roman Temple in London”. Times, 25 September 1954, 7.

Ward, Laurence. The London County Council Bomb Damage Maps 1939–1945. London: Thames & Hudson, 2015.

Williams, Richard. “Reformation”. In Art under Attack: Histories of British Iconoclasm, edited by Tabitha Barber and Stacy Boldrick, 48–73. London: Tate Publishing, 2013.

Wright, Herbert. “Bronzed and Breathing: Architects: Foster & Partners”. Blueprint 356 (February 2018): 124–38.

Wright, Susan M., ed. Archaeology at Bloomberg. London: MOLA, 2017. https://assets.bbhub.io/company/sites/30/2017/11/BLA-web.pdf.

Imprint

| Author | |

|---|---|

| Date | 14 November 2025 |

| Category | Article |

| Review status | Peer Reviewed (Double Blind) |

| License | Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) |

| Downloads | PDF format |

| Article DOI | https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-28/abrandonsalmon |

| Cite as | Brandon-Salmon, Altair. “The Resurrection of the Body: The Temple of Mithras in the City of London.” In British Art Studies. London and New Haven: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art and Yale Center for British Art, 2025. https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-28/abrandonsalmon. |