Turner’s Pencil

Turner’s Pencil: Graphite Landscapes and Extractive Industry

By Tobah Aukland-Peck

Abstract

The Borrowdale graphite mine in England’s northern Lake District was constructed on an exceptional graphite deposit that was first excavated in the sixteenth century. The dense, dark, and smooth material found there drove an artistic innovation: the modern pencil. Cumbrian graphite was synonymous with the pencil which, in turn, helped popularise the sketching tour, predicating the presence of artists such as J. M. W. Turner in the Lake District on the mineral composition of its topography. Drawings of the striking rural landscape in the environs of the mine, however, belied the reach of its mineral deposits. While Turner’s sketches of the area obscure industrial infrastructure, this article reads between the drawings’ imprecise lines to reveal an encounter between artist and industrial landscape that was mediated through material. Through his experiments with the notational possibilities of graphite and his interest in industrial sites, Turner’s approach to the landscape encompassed both the visible landscape and its subterranean components.

Turner’s Pencil: Graphite Landscapes and Extractive Industry

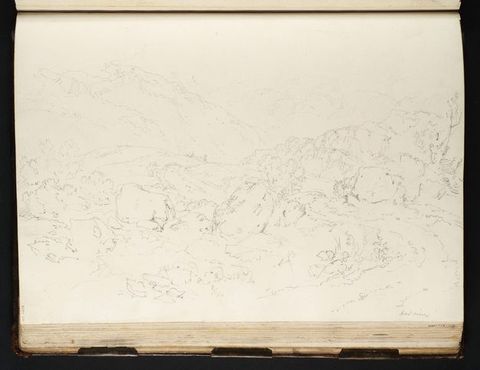

J. M. W. Turner’s 1797 graphite sketch Road over the Fells with a Lead Mine,which the artist drew during an important early sketching tour of England, shows little industrial infrastructure (fig. 1). A series of overlapping hills in the background of the white page give way to a foreground littered with scribbled lines that delineate the forms of bushes, boulders, and grass. The eye of the viewer follows the curving road, which leads to a dip in the terrain where a roof topped with a gently smoking chimney peeks out. However, the waste heaps, sorting houses, and tools that typically herald the presence of subterranean workings are absent. Rather, the titular presence of the mine comes from a scrawled note at the bottom of the page that reads “lead mines”.1 The mine recorded by Turner could be one of those in the mountainous area of the northern Lake District, where an extremely valuable commodity was found: black lead, the substance that we know as graphite today.2 Even if it refers to a lead ore mine rather than a graphite one, Turner’s notation is neither the only nor the most important evidence of a mine in the drawing. That he used a graphite pencil means that the entire image—the scribbled lines, the rise of the hill, the scattered boulders—consists of mined material. The process of extraction, while nearly indiscernible in the sketch, is inextricable from the artistic material that produced the image.

1

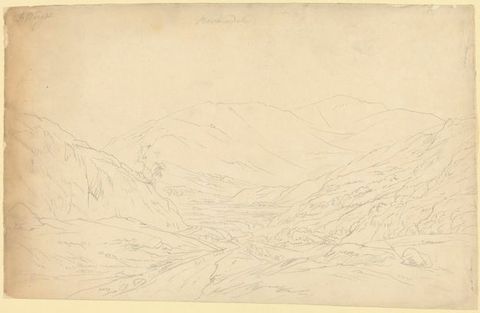

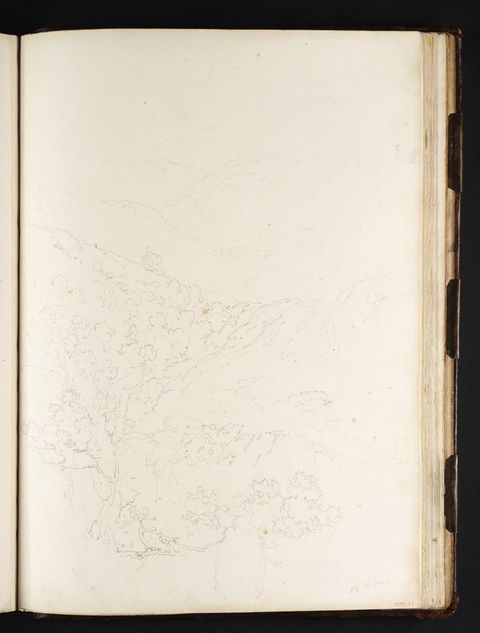

While the title of Road over the Fells makes the relationship between sketch and mine explicit, an earlier drawing in the same notebook titled Borrowdale, with Seathwaite in the Distance also contains the suggestion, albeit more obliquely, of Turner’s interest in the Lake District’s subterranean industry (fig. 2). Though it remains unseen among the outlines of mountains, trees, and fields, from this vantage point Turner would have looked directly towards the famous Borrowdale graphite mine. Cumbrian graphite was Europe’s principal source of graphite from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries. These mines were the origin of the modern graphite pencil. The spectrum of marks—including fine detail, soft texture, and legible text—that can be produced by this sought-after mineral made the pencil a multipurpose artistic tool, and the discovery of the Borrowdale graphite mine revolutionised the acts of writing and drawing. Cumbrian graphite was synonymous with the pencil, and the portability and simplicity of the pencil, in turn, helped popularise the sketching tour, a revolutionary moment in the development of British art practice. Turner’s presence in the Lake District was predicated on the mineral composition of its topography and, wielded by him, the graphite produced the image of the landscape from which it was derived.

This article contends that Turner’s 1797 Lake District sketches, likely drawn with a pencil made of graphite from the Borrowdale mines, betray a glimpse of the extractive provenance of this fundamental sketching material. The ubiquitous nature of the graphite sketch, in both Turner’s expansive archive and the work of other artists, makes graphite from Borrowdale a noteworthy example of the reliance of art-making on mined material. Yet it is one that is largely absent from the visual record. While written travel accounts of the area, including William Gilpin’s canonical text Observations, Relative Chiefly to Picturesque Beauty (1772), described the mine and the valuable material within, the world-famous industry resisted artistic representation almost entirely. Save for the title of a 1788 print, based on a Philip de Loutherbourg painting, the Lake District’s graphite mines remained unpictured in the hundreds of drawings, watercolours, and paintings of this area of the Lake District.

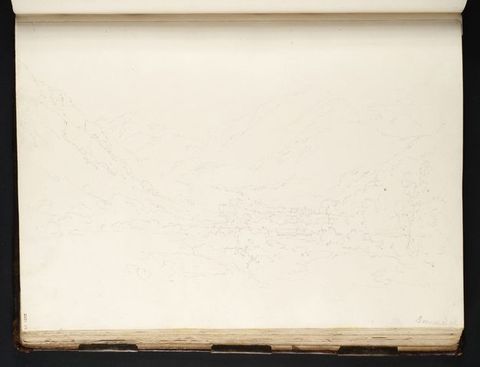

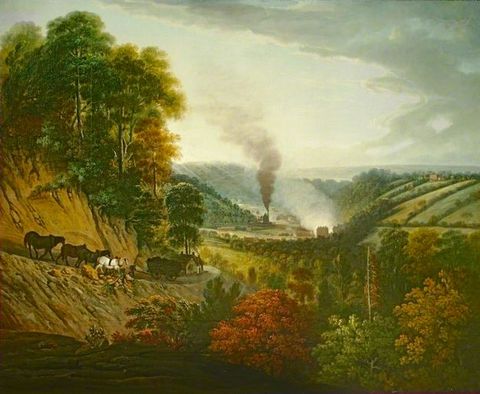

The study of extraction is a study of origins, of hidden subterranean spaces from which so many goods, ideas, and problems, despite their appearance to the contrary, are derived. Scholars have frequently considered the relationship between art and industry as one dictated by subject matter, and important studies have traced the representation of foundries, railways, and factories.3 These analyses are often situated in the context of urban manufacturing, a framing that has shaped the scholarly division between Turner’s industrial scenes—such as the looming walls, shadowy figures, and white-hot fire of The Interior of a Cannon Foundry (1797–98)—and his natural landscapes, like the drawings from his first trip to the Lake District (fig. 3).4 “Industrial scenes”, James Finch writes in the catalogue for the recent exhibition Turner’s Modern World, “provide a counterpoint to the landscapes that were Turner’s general focus during his sketching tours”.5 Yet industrial extraction was tied to the natural landscape, for ancient geological strata formed both subterranean mineral deposits and the surrounding fields, hills, and mountains. Mines defy the stability of industrial iconography, interrogating the centrality of urban factories and smokestacks to industrial art histories.

3

Turner pursued the unseen components of the landscape through his experiments with the notational possibilities of graphite, his interest in industrial sites, and his desire to picture the visually intangible aspects of landscape: aerial phenomena and subterranean geology.6 His Lake District sketches indicate the material foundation of visual and conceptual knowledge, evidence of the intertwined nature of cultural and industrial production at the zenith of the Industrial Revolution.7 Sketches, created out of the meeting of graphite and paper, are made possible by a central contradiction: the landscape is made legible on paper only by the despoliation of that same landscape.8 While mining infrastructure disrupts above-ground vistas, much of its impact evades sight: from darkened, dusty mineshafts to the waste piles and pollutants that alter the surrounding air and terrain. It is a vital economic mechanism that relies on large working-class communities but, in many images and texts, it is encountered obliquely. The resistance of mined material to visual legibility challenges the precedence of the visual in analyses of the landscape and encourages an expanded account of the factors that form artistic experiences of the rural sphere.9 Sketches too elude pictorial clarity. The writer Cyrus Redding accompanied Turner on a drawing excursion in 1812 and observed that the artist’s pencil lines were “slender graphic memoranda”.10 Rather than providing immediately legible scenes, the graphite sketch conveys information through a combination of symbols, text, and likeness. More than just a physical trace, it captures the mine’s visual ambiguity through its evasion of fixed form.

6As graphite underwent a process of refinement from raw material to artistic tool, it was taken from rural places of extraction to urban sites of consumption—a journey that artists like Turner undertook too, as they refined landscape sketches into exhibition paintings. Graphite and sketches were consumable products of the landscape caught up in the circulation of materials, workers, and currency. Accordingly, this article follows the path of artist and material as they travel between London and the Lake District. Beginning with the early history of Cumbrian graphite mining, I move from London to the Lake District and back again, following Turner from his purchase of graphite at a local artist’s supplier, through his trip to the Lake District, to the graphite mine itself, and then finally back to his studio in London. We are well acquainted with the final products of this system: the landscape painting and the graphite pencil. This article, however, brings to the surface the unacknowledged processes and materials—mining and seams of graphite—that facilitated their creation.

Beginnings: The Lake District Graphite Mines and Turner’s Early Career

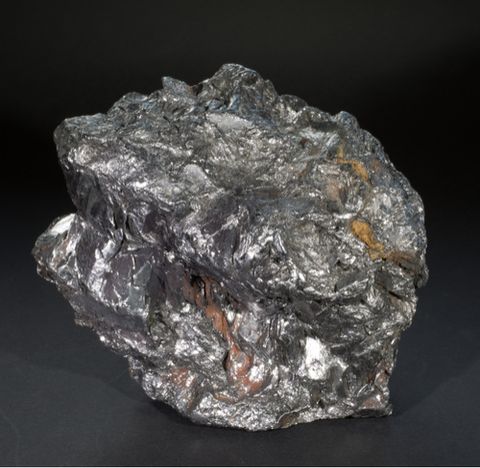

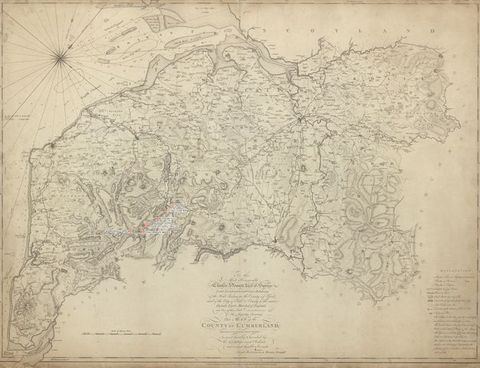

Until the early nineteenth century, the story of the graphite pencil was one of striking site specificity. Before this point, the graphite in almost every pencil sold in the United Kingdom would have been extracted in Cumbria. Ancient carbon deposits left a significant graphite vein in Seathwaite, outside the village of Borrowdale. Smaller seams dotted the surrounding area, but the Borrowdale mine, as it came to be called, was the most famous and long-lasting site of graphite mining.11 A popular origin story tells of graphite discovered on the underside of a fallen tree in 1565, though studies by Henry Petroski and Ian Tyler, scholars of the pencil and of the Lake District mines, respectively, argue that the discovery almost certainly preceded this date.12 During the sixteenth century, the smooth and slightly oily substance could be obtained relatively easily from near the surface (fig. 4). The mineral had non-calligraphic applications and was used to mark livestock, in constructing smelting crucibles, in medicinal tinctures, and for industrial lubrication.13 Cumbrian graphite was integral to the instruments of imperial Britain, smoothing ship rigging and lining cannons.14 However, even by the late sixteenth century, as the local Cumbrians experimented with methods of encasing the graphite in sheepskin, twigs, and string, it was its artistic purpose that made it most prized across Britain and Europe. The artistic association was already treated as an established one in a reference to Borrowdale in William Camden’s 1607 Brittania: or, A chorographical description of Great Britain and Ireland, “Here also is found abundance of that mineral earth, or hard shining stone, which we call Black-lead, used by painters in drawing their lines and shading”.15

11

The graphite pencil combined, and eventually superseded, two pre-existing implements: the pencil brush and the lead stylus. The word “pencil” comes from the Latin for “brush” and originally referred to small brushes used for delicate renderings. Graphite mimicked the fine line of a pencil brush but was significantly easier to use. Before the extraction of graphite from the Borrowdale mine, lead alloys crafted into a stylus were used to produce a light mark on a prepared page, a process known as metalpoint.16 Graphite, however, made darker and clearer marks on more variable surfaces. The texture and colour of the unique material was reminiscent of metallic lead deposits and, as a result, it was frequently referred to as “black lead” or “plumbago”. This linguistic elision gave rise to a common misconception that graphite was a form of lead, a conflation of the two materials that still exists today in the phrase “lead pencil”. It also precludes a decisive identification of the type of mine pictured in Road over the Fells or in Loutherbourg’s 1783 painting Labourers near a Lead Mine. In Cumbria, which was also the site of many lead mines, the local community frequently called the substance “wad”.17 The word “graphite”, from the Greek word graphein (“to write”) and the mineral suffix -ite, was coined in 1789. At the time of Turner’s first visit to the Lake District, graphite was established as inseparable from the acts of writing and drawing.

16Borrowdale graphite was a local material entangled in the politics of Britain’s global trade networks. By the first decades of the seventeenth century, graphite sheathed in wood (a close cousin of our contemporary pencils) was selling on the streets of London.18 The new tool was enthusiastically adopted and a brisk international trade developed.19 The popularity of the material and the singularity of the source made the Borrowdale mine extremely lucrative, so much so that a 1752 parliamentary bill sought to control access to the site. Henry Bankes, a member of a prominent Dorset family who owned a half share in the mines, introduced legislation titled “An Act for the more effectual securing Mines of Black Lead from Theft and Robbery”.20 This bill implemented punitive measures for unauthorised extraction and tightly controlled the dissemination of graphite, codifying the national importance of the mineral.

18Turner’s visit to the Lake District in 1797 came at an inflection point in the use and circulation of graphite, when the mineral product was challenged by manufactured and mass-produced versions. Britain was aware of the singular natural resource at its disposal and, during times of conflict, cut off the graphite exported to the Continent. A naval blockade in the 1790s gave rise to a significant threat: the French invention of the Conté pencil in 1795. This tool, created in response to the wartime dearth of Cumbrian graphite, used compressed graphite powder mixed with clay to mimic the effect of pure graphite. Made in a factory, the new implements were more standardised than their British cousins. Richard Taws characterises the Conté pencil as a modern tool that “disavowed origins”, its factory provenance a corrective to the provisional quality of the drawing.21 Conté’s invention of the factory-produced pencil precipitated an ontological shift from a natural product to an artificial one, and from a site-specific subterranean resource to a replicable factory commodity. The manufactured characteristics of the new Conté pencil brought the natural origins of Borrowdale graphite into stark relief.

21Though the graphite pencil derived from the Borrowdale mines was produced in an industrial context—with specialised labour, systems of water drainage, and strategies of waste disposal—its extractive origins meant that it was susceptible to the vagaries of nature. Borrowdale’s enormously valuable graphite deposits relied on geological chance. “Strange to say, the great value of graphite for the purpose of pencil-making does not depend on its actual purity, but upon the peculiar aggregation of its particles”, Thomas Archer, the director of the Industrial Museum of Scotland, noted in an article about artists’ materials in 1862.22 The efficacy and quantity of Cumbrian graphite was ultimately contingent on its unique geological make-up rather than on human ingenuity. For Turner in 1797, the graphite pencil was still a natural product, conflating the actual landscape and depictions of it. If, as Taws argues, the Conté pencil clarifies the simulacral quality of the drawing, the pencil sketch made of Cumbrian graphite possesses a material immediacy that undergirds the sketch’s mimetic capacity.

22Other materials, like paint and photographic chemicals, have important connections to extraction, but graphite appears among the artist’s tools, and on the page of Turner’s sketchbook, in an almost unadulterated form.23 It is recognisable simultaneously as a mineral and as a tool. Contemporaneous advertisements for stationers and colourmen, many of whom had shops on the Strand only a short distance from Turner’s childhood home in Covent Garden, demonstrate the value that was placed on the authenticity of Cumbrian graphite pencils. Nicholas Middleton emphasises his family links to Cumberland in an advertisement from 1772 promising that he is the “real and genuine Manufacturer, from Cumberland”.24 Later advertisements for R. Ackermann, whose famous shop attracted professional and amateur artists alike, highlight his selection of “genuine Cumberland black-lead pencils” (fig. 5).25 These advertisements make the high quality and desirability of Lake District graphite clear. “The Useful and the Useless”, an 1837 advertisement for G. Riddle Pencils reads, “The Public should discriminate between the genuine … cumberland lead … and the defective imitations offered for sale at apparently low prices”.26 Because of the name recognition of Cumbrian graphite, Turner, like all artists based in London, would have associated the northern landscape with his pencil and been conscious of the mines around Borrowdale as the unique source of “genuine” graphite.

23

In 1797 the twenty-two-year-old J. M. W. Turner was a student at the London Royal Academy (RA), poised for success. He had exhibited his first oil painting, Fishermen at Sea, at the RA summer exhibition the previous summer. Before embarking on his trip to northern England, which would take him up to the Scottish border through Yorkshire, Lancashire, and Cumberland during the summer and fall of 1797, Turner visited London’s stationers to source his most important materials: paper, pencils, and watercolours. Apart from the graphite lines preserved in these sketchbooks, no trace exists of the pencils that Turner purchased for the trip. The details of his particular tool, small and disposable, have been lost to history. However, while we do not know from which of London’s artist supply stores Turner sourced his pencils for the 1797 trip, it is almost certain that the graphite in the pencils available to him would have come from the Cumbrian mines.27 Turner also purchased two imposing leatherbound sketchbooks for the journey, a departure from the small portable ones that he typically used.28 The sketchbooks seem to signal his readiness to embrace a grand scale in both his subject matter and his career. While Turner had already made multiple sketching tours outside of the capital, this journey marked a significant point in his development as an artist. His close engagement with this new dramatic landscape established matter—of mountains, lakes, and natural terrain—as a centre of his practice.29 Even before his departure for the Lake District, Turner’s reliance on the pencil as his “standard tool”, according to Andrew Wilton, would have fostered an intimate familiarity with the material attributes of this mineral. Pencil sketching was at the centre of Turner’s creative translation of the natural world.30

27“The Mine at a Distance”

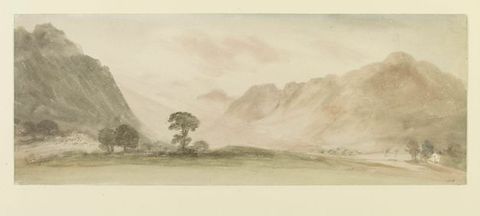

Turner arrived in the Lake District in early August 1797.31 The drawings that appear in the sketchbook pages before Borrowdale tell of an ambitious excursion that took the artist south to visit some of the Lake District’s most famous landmarks from his base in Keswick: Derwentwater, the Bowder Stone, and Castle Crag (fig. 6). These were, for the most part, well-established views from earlier literature and drawings. As Turner was in the early stages of his career, this trip to the Lake District was in part a pedagogical enterprise to expand his vocabulary of British landscape forms. Many of his contemporaries embarked on similar journeys around the Lake District because of its popularity among both professional artists and amateur sketchers. During their travels, these artists encountered the area around Borrowdale and, like Turner, would have been aware of the mine. John Farington, one of Turner’s mentors, had lived in the Lake District and his well-known 1789 aquatints of the area include the mountains to the north of Borrowdale. Francis Towne and Joseph Wright recorded views of the winding road and Borrowdale’s seemingly endless mountains in the late 1780s and early 1790s, Towne in watercolour, ink, and graphite and Wright in a simple graphite sketch (fig. 7). Most notably, John Constable spent three weeks sketching the area around Borrowdale in 1806. Constable’s 1806 View in Borrowdale (fig. 8) is a similar view to Turner’s Borrowdale, with Seathwaite in the Distance. The details of the mountains around Seathwaite on the right-hand side are undefined. With the beams of morning light hitting them from the left of the composition, they almost blend into the pink-tinged sky. During his time in Borrowdale, Constable walked the mountains around Seathwaite and would have passed close to the mine on his excursions to Sty Head. Strikingly, none of these examples include any inkling of the extractive works. Turner—with his exceptionally comprehensive archive of sketches and his continual interest in industrial themes, from the roughly contemporaneous A Limekiln, Possibly at Briton Ferry in South Wales (circa 1797) to the famous Rain, Steam, and Speed (1844)—is the focus of the present study (fig. 9).32 But the graphite substrate of the drawings of Borrowdale by other artists, those detailed here and hundreds more professional and amateur sketches, reveals the same proximity between artist, pencil, and mine.

31

For these travellers, one figure loomed large—the writer William Gilpin. A clergyman and amateur artist, Gilpin was famous for his conception of the picturesque. This fundamental term of Romantic art was codified by Gilpin in the 1770s, including in Observations, Relative Chiefly to Picturesque Beauty, which chronicled his time in the Lake District.33 The inclusion of the Borrowdale mine in the book demonstrates the site’s notoriety, and Gilpin’s description evidences an interest in the mine’s relationship to the landscape. Turner was following in the footsteps of Observations as he continued down the Keswick Road and arrived at the village of Borrowdale. However, Gilpin’s description of the mine is marked by general knowledge rather than first-hand experience:

3334I could not help feeling a friendly attachment to this place, which every lover of the pencil must feel, as deriving from this mineral one of the best instruments of his art; the freest and readiest expositor of his ideas. We saw the site of the mine at a distance, marked with a dingy yellow stain, from the ochery mixtures thrown from its mouth, which shiver down the sides of the mountains.34

The mine, marked from a distance by its aberrant “yellow stain”, seems disconnected from the pencil, which Gilpin defines as a conduit to human cognition. Instead, the trace of mining waste on the surface threatens the integrity of the landscape. Gilpin can reconcile the two only through distance—he will not visit the mine. An encounter with a space of industrial labour, as opposed to agricultural work, would undermine the contrast he has established between the bucolic Lake District and London’s grotesque industry. Indeed, Gilpin does not even mention other notable sites of local extraction like the slate quarries at Honister or the copper mines at Coniston. For Gilpin, to travel towards the mine would be to expose the mirage of the picturesque, which renders the visual membrane of the landscape without its geological or economic underpinnings.35 The graphite mine does not, he writes, “promise more on the spot than it discovered at a distance”.36

35The description of the mine in this famous account of the Lake District shows that Turner would have been well versed in the history of the site. Stopping at many of the same vistas as Gilpin, Turner had probably either read the book before he embarked on his travels or perhaps even brought it with him.37 The mine also appeared in eighteenth-century guidebooks to the area. Thomas Gray, the poet, noted the difficulty of accessing the mountains around the Borrowdale mine, when you “come to Sea-Whaite ([which] leads to the Wadd-mines) all farther access is here barr’d to prying Mortals”.38 For Gray, the remoteness of the area had an almost mythical quality. In 1800 John Housman, the author of a topographical study of the area, echoed Gilpin’s description of the mineral waste that emanated from the mines: “On the west side of this rocky dale, almost opposite the village of Seathwaite, the famous black-lead mine is seen vomiting its useless rubbish midway up the mountain”.39 Waste was also at the front of John Hudson’s mind in his 1843 guide to the Lakes: “A mile beyond Seatoller the Black-lead (or as it is provincially termed ‘Wad’) mine indicates its position, high on the hill-side, by those unsightly heaps of rubbish which always attend mining operations”.40 These stony heaps grew larger as more extensive tunnels were excavated in the workings below, a process that generated the excess material that miners gathered into teetering piles around the shaft opening. Even when the mine was closed, as during various production freezes, the large waste piles marked the presence of industrial operations.41 In 1751 George Smith of The Gentleman’s Magazine set out to investigate the famous mines and, after an arduous uphill climb, came across a group of local men and women picking pieces of graphite from the waste piles, “digging with mattocks, and other instruments, in a great heap of clay and rubbish”.42 While they lived close to the mine, these people could not take part in its official commerce. Instead, they worked outside the bounds of the extractive market, their unauthorised labour sorting through discarded materials challenging conventions of ownership, value, waste, and productivity. Gilpin called the profits of waste picking at Borrowdale—which he knew of rather than had witnessed—“honest gains”, but it was nevertheless illegal.43 The local pickers fled when they glimpsed Smith’s party, fearing the consequences of being apprehended taking materials from around the mine. Access to the mine for artists and writers like Gilpin, Gray, and Turner was hindered not so much by topography as by their desire to avoid the waste landscape and those who worked on it.44 These material and human by-products of mining operations were deemed exhausted of the potential for profit, whether monetary or visual.

37Centuries later, heaps of spent stone still stand out on the hillside around Borrowdale (fig. 10). The prominent presence of the waste signals that, despite the relatively small scale of the graphite mining operation and the exceptional natural scenery around it, the Borrowdale mine shared attributes with Britain’s growing coal- and tin-mining operations. Like the dark interior of the mine, the formlessness of its waste—an above-ground index to the scale of underground extraction—challenged attempts to capture it in visual form. A drawing by John Sell Cotman, a fellow RA exhibitor, abstracts the surroundings of a coal shaft in Coalbrookdale that he visited during a tour of Shropshire and Wales in 1802 (fig. 11).45 Cotman’s pencil lines linger on the polluted aspects of the surrounding landscape: the billowing smoke emanating from behind the shaft head winding gear and the dark spoil tumbling down the roughly rendered foreground.46 Cotman uses the brown substrate of the wove paper to signal the barrenness of the waste-strewn colliery landscape, while the emptiness of the rocky foreground contrasts with the green ridge just visible behind the swirling smoke. Mining works—whether a mountainside graphite mine, a coal mine in the increasingly industrial environs of Coalbrookdale, or a tin mine on the scenic Cornish coast—alter the landscape around them, layering subterranean matter over the surrounding terrain. The piles of stony rubbish that typify each of these mining vistas, as Hudson reminded the reader in his description of the Borrowdale mine, were a problematic contrast to the expected scenery of the Lake District landscape. Not aesthetically pleasing and therefore not visually productive, the landscape around the Borrowdale mine was, to borrow Housman’s term, “useless” to the viewer.

45

Despite its notoriety, Turner’s encounter with the mine two decades after Gilpin’s was also at a remove. Borrowdale was the southernmost sketch of a day trip from Keswick. The Loathwaite Bridge, where this sketch was made, would have been the closest Turner got to the mine, which lay two miles further down the road (fig. 12). The sketch looks towards the valley described by Gilpin, and the mine would appear on the slope of the right-hand mountain. While Gilpin and Housman described the mine, attendant buildings, and waste piles disturbing the landscape, Turner’s mountainside shows only the smooth white of the paper untroubled by industrial stain. However, Turner’s choice to sketch this view and his familiarity with Gilpin’s Observations would suggest that he was aware of the mine’s presence and would have felt the same pull of “attachment”. Yet, more than anything, this sketch of trees, fields, and mountains emphasises the remoteness of the mine. Not only is it too far to travel there, but a sketch of the famous site is also not an attractive possibility. Turner’s association with Borrowdale, like Gilpin’s, is obscured by his choice to remain at a distance.

The picturesque tourist was instructed to see the landscape as a collection of discrete objects and vistas that could be controlled, or made visible or invisible, through representation in words or in images. An industrial interruption, like the waste spewed from a mine, could be omitted from a depiction of the scene as easily as Gilpin could physically turn away from it.47 This exclusion was significant because industrial sites like the graphite mines disclosed capitalist interventions in the country landscape.48 Stephen Copley, a scholar of Romantic literature, notes that Gilpin’s “account of the mine offers a partial and momentary glimpse of the economic structures that underlie and underpin the tourist’s vision of ideal natural landscape”.49 The amateur sketcher who manipulated the natural landscape on the page could erase the labour of those, like graphite miners, who altered the physical fabric of the landscape in the service of commercial enterprise. The pencil itself, by transitioning from mined material to artistic tool, participated in this effacement of the economic reality of its origins in yet another mystification of the capitalist process.

47The material connection between artist and pencil, however, complicates the self-imposed distance between artist and mine. Gilpin’s “friendly attachment” to the pencil is intellectual but also, crucially, physical: the “ochery waste” on the mountain and the graphite mark in his notebook are both material products related to the pencil in his hand. Drawing, poetry, or painting may purport to abstract from the baser elements of the physical landscape in favour of philosophies of sublimity or transcendence, but graphite builds a connection between the mental and the physical experience of the landscape, encompassing both the idealisation of the picturesque and the geological formation. Scholars including Onno Oerlemans have challenged the assumption that Romanticism and the picturesque were ideologies that were isolated in the subjectivity of the individual mind.50 Rather, Romantic art forms are constituted by the haptic, the movement of bodies in space. Nature is moulded by human intervention, and the physical relationship between artists and their subjects points to the role of art-making in the process of this formation. Somatic experiences of landscape—and, by implication, the materials produced from it—cannot be separated from the picturesque journey. While the mine sits just beyond perception in Borrowdale, its presence is tangible.

50Lead Mine

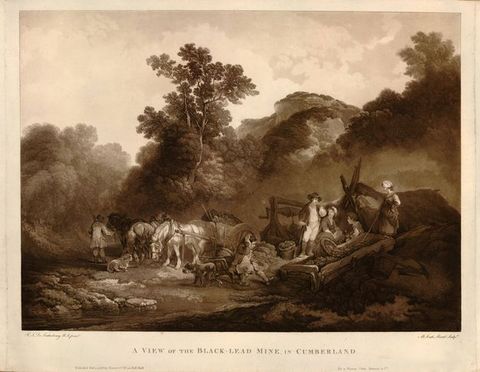

A 1788 print based on a painting by Loutherbourg titled A View of the Black-Lead Mine in Cumberland seems to bring the viewer closer to the Borrowdale mine than Gilpin’s description or Turner’s sketch (fig. 13).51 In the image, a group of workers—youthful men and women—are gathered around a stream in a tree-lined clearing, with a dramatic rocky outcrop rising above them. Dogs roam the grass and a group of horses prepare to remove a cartload of stone. Baskets are filled with mined material. The rough texture of the mineral, as rendered by Maria Katharina Prestel, is almost identical to that of the leaves around it, a confluence of form that naturalises the extracted product in the above-ground landscape. Despite the artfully placed basket, shovel, and pick, none of the figures are actively working: their faces are turned towards each other as if in conversation; their limbs are slack and their movements unhurried. Loutherbourg moulded the workings into a familiar image of idealised rural labour, hiding the difficult working conditions inside the mines. The original 1783 painting that A View of the Black-Lead Mine in Cumberland is based on was titled Labourers near a Lead Mine and, according to Rüdiger Joppien, depicted lead ore mines in Derbyshire rather than graphite mines in the Lake District.52 While Loutherbourg alluded to extraction in his title, and gave the viewer a sense of the smaller scale of some rural mineral workings, the linguistic indeterminacy between the lead of the painting and the black lead of the print further emphasises that this image shows no more details of actual industrial production than the dramatic vistas of the mountains around Borrowdale.

51

Unlike Loutherbourg’s limited view, Turner’s Road over the Fells shows no workers, tools, or discernible pieces of mined material. While the image suggests the presence of industrial workings, the mine is subsumed into the undulations of the Lake District landscape. The vantage point of this sketch is closer to the mining works than that in Borrowdale, and the titular road seems to hint at a human presence that is absent in the Borrowdale sketch. But the end of the road, where the mine should be, fades away in the top register. As the viewer squints to locate human incursions in the scene, Turner’s pale graphite lines seem complicit in the concealment of form. This is a road to nowhere, blocked by scribbled shrubs and boulders, as impassable to the viewer as the path towards the mine was for Gilpin.

We are left only with the words “lead mines” at the bottom of the sketch, through which Turner invokes the presence of a mine without an intimate encounter with its infrastructure. The illustrative value of these hastily scrawled words shows how graphite expanded the representational capacity of Turner’s sketch not only through its geological form but also through the variability of its marks. Turner used graphite both visually and conceptually to represent texture, to make notes about colour or subject, and to silhouette form. Text was another mode of making meaning with graphite. Words, Marcia Pointon argues, have a structural force in Turner’s conception of the image.53 While the graphite mark was an artistic act, it also created data to be applied back in Turner’s studio to produce an oil painting. Text, image, and memory worked together to recreate the scene. Though resemblance was one function of the pencil, the flexibility of the material expanded its notational capacity.54 In contrast to Loutherbourg’s print, the difficulty of discerning detail in Borrowdale and Road over the Fells is partly due to the nature of the sketching process, which captures scenes in quick succession. In this context, mimetic representation is beside the point. In 1877 the famed critic John Ruskin reflected on Turner’s drawings in the pedagogical manual The Laws of Fésole: “Turner’s lead outline[s] in landscape, are beyond all rivalry in abstract of graceful and essential fact”.55 The pencil lines distilled the busy landscape into essential elements for later contemplation and use; graphite was the bedrock of words, line, colour, and form.56

53The abstracted signs—the text and outlines—that make meaning in Borrowdale and Road over the Fells are evident in many of Turner’s sketches of locations in the Lake District and elsewhere. The abbreviated format of the graphite sketch forestalls industrial detail in these two drawings. The rubbish heaps reported by contemporaneous writers are indistinguishable from rocks and mountainsides. The sorting house is no different from a domestic dwelling. Yet the struggle to discern detail in the sketch is evocative of the failure of vision in the mine’s interior, a space that resists close observation. Despite the spoil heaps, labourers, and related buildings on the surface, to the sketcher or the picturesque tourist—the relationship between the industrial space, the landscape it lies in, and the commodity it produces is partially hidden by the subterranean nature of the mine, despite the spoil heaps, labourers, and related buildings on its surface. Only the small group of professional miners who worked at Borrowdale could access its interior, whose conditions were defined by elements that obscured the senses: darkness, confinement, and dust. While the print of A View of the Black-Lead Mine in Cumberland relies on tropes of rural industry to contextualise the environs of the mine, in graphite sketches such as Borrowdale and Road over the Fells the unseen mine asserts itself on the page through the provisional outlines of Turner’s graphite marks.

The Lake District at the Royal Academy

The translation of sketches into finished oil paintings traced a process of refinement, as visual components of the sketches were isolated and recombined into an ideal scene. In an echo of the process of industrial extraction, the artist had to transform raw scenery into saleable art objects, mediating between distant sites and the viewing public. The relationships in Turner’s sketches between artist, landscape, and material were regulated by a system that processed both graphite and artistic products through a single commercial centre: London. The geologist Jonathan Otley wrote in his influential 1842 study of the Lakes, “In the vicinity of the mine, the pencil-makers are obliged to purchase all of their black-lead in London, as the proprietors will not permit any to be sold until it has first been lodged in their own warehouse”.57 Graphite mining in Cumbria was not a site-specific cottage industry. Rather, it depended on the same system of urban warehouses and metropolitan owners as goods from distant colonies. Access to the land around the mine was highly regulated. The high prices commanded by Borrowdale graphite in the eighteenth century had attracted unscrupulous practices, from theft by employees to clandestine tunnelling into the mine. A parliamentary act of 1752 responded to these problems by criminalising unlawful entry. A series of guardhouses were built, employees were searched, and the mine was flooded during production freezes. The group of waste pickers Smith glimpsed working around the mine’s rubbish heaps in 1751 would, a year later, potentially face punishment. This separation between the mine and the rest of the countryside defined the value of the landscape in terms of the London market and, eventually, global cycles of trade. The Cumberland Pencil Company factory in Keswick, built in 1832, relied on a long history of pencil manufacturing in the area but, ultimately, enjoyed no special access to the material.58 Likewise, the value of Turner’s sketches was realised only in London, through the oil paintings that they contributed to creating.

57Out of hundreds of sketched scenes, Turner produced only two oil paintings from his northern travels, neither of which was related to Borrowdale. Morning amongst the Coniston Fells and Buttermere Lake, shown at the Royal Academy in 1798, attended to the Lake District’s weather and dramatic topography (figs. 14 and 15). Although it was relatively rare to see industrial subject matter in paintings displayed at the annual exhibition, the fortunes of the academy’s patrons were based on systems of natural extraction, from colonial trading to agriculture, to mining.59 A prime example of this was the Bankes family, who owned the majority share of the Borrowdale mine from 1665 to 1981, when they transferred ownership to the National Trust.60 The Bankes estate in Kingston Lacy, Dorset, underwent a significant renovation in the late 1780s with the profits garnered from the high price of graphite in the latter part of the eighteenth century.61 The family collected art and, in addition to paintings by Rubens, Van Dyck, and Tintoretto, the walls of Kingston Lacy were adorned with works by RA artists including Joshua Reynolds, Thomas Lawrence, and Henry Bone.62

59

Archer, the director of the Industrial Museum of Scotland, wrote in The Art Journal in 1862 that the Borrowdale mine was “a mine of wealth to its possessors, and has realised in one year the large sum of £100,000”.63 Archer’s play of words transmuted graphite from commodity into currency, directly transforming subterranean matter into the Bankes family’s wealth, of which famous oil paintings were a major indicator. In the same way, the value of oil paintings overcame, and often erased, the material conditions of their creation—the tools, the preparatory sketches, the studio labour. While Turner’s sketches from his 1797 northern tour are now easily accessible through a digital archive, during his lifetime they were not available for public view.64 The graphite sketches, accumulated in piles in his studio and often marred by bugs and damp, were the effluence of the artistic process, a by-product. Like the piles of waste outside the “vomiting” mouth of the Borrowdale mine, they did not have intrinsic value but reflected the laborious process of production. It is the unusual condition of the Turner Bequest, which has preserved and made public an enormous body of preparatory works, that makes the present study possible, while those of many of Turner’s contemporaries have been lost. Compared to the tangibility of oil paintings like Morning amongst the Coniston Fells or the profit garnered from the distribution of engravings and prints, graphite sketches like Borrowdale, with Seathwaite in the Distance and Road over the Fells with a Lead Mine were promises of future forms rather than commercial products of artistic labour. The objects that were imbued with value—the final painting or print—concealed the graphite mark and, in doing so, abstracted their origins. Formation—geological, industrial, and artistic—was overlaid by finish.

63Once back in London, Turner used his sketches as a basis for his oil paintings, which would be hung in the Royal Academy exhibitions and sold to collectors. As his career progressed, the artist became well known for his experimental and increasingly public investigations of the development of paintings, from his innovations in oil sketches to the famous RA varnishing days, when he would swiftly complete enormous paintings in front of onlookers. Over time, his performative art-making made the hidden processes and materials that produced the oil painting visible.65 At this early stage, Coniston Fells and Buttermere Lake amalgamated his experiences into cohesive compositions that purported to show single locations but were based on elements of several other drawings from the trip. In this, the artist relied on both of graphite’s functions: image-making and notation. In the studio, Turner played with his original sketch of Coniston Fells, which traced the stream and waterfall over a series of indistinct peaks that overlapped in the centre of the composition (fig. 16). The painting expanded this vague outline with soft colour, dramatic clouds, and details like a road and a flock of sheep. Just as graphite was extracted from the landscape and sent to London to be processed, the final product of Turner’s time in the Lake District processed the countryside in the context of an urban studio.

65

Despite the refined nature of the final artistic product, the calligraphic capacity of Borrowdale graphite was born from its contaminations. The graphite was an unusual combination of mineral elements, found only in the Lake District, that made the material so well suited to mark-making on the page. Archer reminded the reader that purity “may easily mislead the uninitiated manufacturers, who imagine they have only to seek for purity to insure success. Graphite of very fine quality is obtained from Mexico and from Ceylon, the latter being the purest yet discovered; nevertheless, for the reason stated, it is inferior for the purposes of the artist to the Borrowdale mineral”.66 The impurity of the Borrowdale seam was directly aligned with artistic potential.

66The details of graphite’s impure mineral form also record its intimate relationship with coal. The visual contrast between the Lake District landscape and Britain’s coal-mining districts belies the geological continuity between these two minerals, both of which are entwined with British national identity. Coal and graphite, along with diamonds, are carbon allotropes, the same element in different physical forms. As such, they shared similar methods of extraction. Borrowdale graphite’s allotropic peculiarity was a subject of speculation in the nineteenth century, one notably raised by Ruskin in The Ethics of Dust, first published in 1865. The purpose of diamonds, Ruskin writes in a fictional Platonic dialogue between an Old Lecturer and a group of young girls, “is the multiplied destruction of souls”: “What one would like to know is, mainly, why charcoal should make itself into diamonds in India, and only into black lead in Borrowdale”.67 Graphite, which was formed “only” in Borrowdale, lies between these two carbon cognates: diamonds, which have a pure and beautiful form but are useless and morally destructive; and coal, which is loathsomely dirty but essential. Ruskin suggests that graphite overcomes its impure mineral basis through the transformative aesthetic potential of the pencil: “Your pencils in fact are all pointed with formless diamonds”, the Old Lecturer tells the girls.68 Just as coal is subsumed by energy production, the process of crafting a tangible image or idea eliminates the troublesome impurities of graphite’s mineral form. Making a drawing eventually destroys the pencil, leaving behind graphite marks, a material trace that is codified as an aesthetic tool rather than as a mineral deposit.

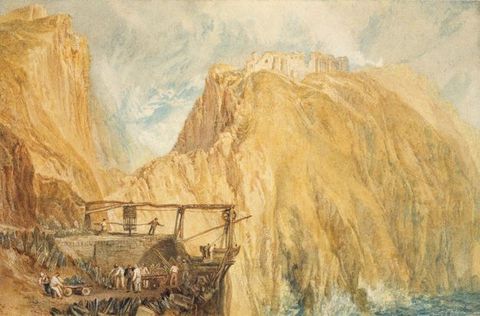

67There remained a clear association between all mines, regardless of their geographic position and the environmental degradation they caused.69 This is evident in the attention observers like Gilpin paid to the waste products thrown onto the landscape from the Borrowdale mine. Despite contemporary awareness of the allotropic relationship between coal and graphite, however, the Borrowdale mine did not share with typical coal mines a proximity to forges and factories. Illustrations of coal-mining landscapes such as William Williams’s 1777 painting Morning View of Coalbrookdale in Shropshire show dark smoke emanating from chimneys and polluted clouds visible from miles away (fig. 17). Turner’s own A Limekiln, Possibly at Briton Ferry in South Wales and Loutherbourg’s famous Coalbrookdale by Night (1801), night-time scenes that use darkness to dispense altogether with the natural scenery visible in Williams’s painting, depict instead the hellish aspects of coal-fired industry (see [fig. 9]).70 Compared to these increasingly smoke-clogged vistas, the graphite mine was more akin to Cornwall’s famous tin mines: industrial sites set amid some of Britain’s most famous scenery. Turner’s watercolour Tintagel Castle, Cornwall (1815), for instance, highlights the contrast between the Arthurian ruins on a vertiginous cliff face and the workings of a seaside tin mine (fig. 18). Turner renders the carts, winding gear, and figures of miners in the foreground in darker pigments and clearer outlines against the hazy background of cliff, castle, and sea. The mine does not yield to the transcendence of the Cornish scenery. Similarly, though many texts show an awareness of graphite itself as an impure mineral form that is inextricable from industrial waste, sketches and paintings of the Lake District maintained the contradiction between Gilpin’s “friendly attachment” to the graphite mine, which was purified by its association with the refined enterprise of sketching, and a rejection of industrial coal mining, which was inextricable from pollution, working-class labour, and waste.

69

Coniston Fells was well received. One critic noted that Turner “seems thoroughly to understand … his various materials; and, while colours and varnish are deluding one half of the profession from the path of truth and propriety, he despises these ridiculous superficial expedients, and adheres to nature and the original and unerring principles of art”.71 This critic, however, did not see that the concern with nature includes a hint of the Lake District’s mineral identity. Coniston was the site of an important copper mine and, though the workings do not appear in the Coniston sketch, Turner suggests an industrial presence in the painting, which acts as a public artefact of his time in the north.72 In a valley on the middle right, a twist of smoke rises to join the wispy clouds of the dramatic Lake District sky. A horse and cart on the bottom right may be engaged in the transport of ore, acting as an industrial pendant to the bucolic sheep in the middle ground. Coniston was a copper mine rather than a graphite one, but Turner’s earlier encounter with the Borrowdale mine relates these two sites of industrial labour.73 Far from “deluding” the artist, the material components of his practice were key to how Turner understood and interpreted nature. The traces of mining operations in the exhibited oil painting show not mere romantic staffage, but a landscape predicated on the geological capital that is hinted at in the distant view of Borrowdale.

71Exhaustion

The booming London graphite trade and the popularity of the graphite pencil hastened the exploitation of the Lake District mines and, in the early decades of the nineteenth century, Borrowdale graphite became an increasingly rare commodity. The deposits, a fugitive resource, were difficult to find, appeared underground without clear pattern, and were quickly depleted. By the 1840s, even the pencil-makers in Keswick were using imported graphite. As site specificity gave way to globalisation, a correspondent for The Builder in 1866 noted the irony: “From Borrowdale to London and back again must have cost as much, if not more, in land carriage than a shipment of lead from Mexico or the Brazils: and what did it matter to the Keswick manufacturers—supposing fair quality—where they obtained their supply or raw material. Since the cedar must come from Florida, they might as well bring the lead at the same time!”74 A mere ten miles from the Borrowdale mine, the Keswick factory was making pencils with powdered graphite from South America and cedar from the United States.

74The transition from local to imported graphite mattered, The Builder contends, because it modelled a successful shift away from indigenous British resources. In 1866 such a precedent had a bearing on another vital industry, British coal. The article continued:

75We have reached an important crisis in our national prosperity. Not only does the Keswick pencil trade supply us with an actual case of the possible phenomena of the exhaustion of coal as a mineral—as a commodity of sale or exchange—but it also supplies us with a remarkable illustration of the method by which an important national manufacture may be carried on independent of coal altogether! In fact, this condition has, we may almost say, been a necessity of its existence. For had the pencil manufacture of Keswick depended upon its congruity to a coal-pit, it could hardly have sprung into existence in the valley of Derwentwater, or in the very bosom of the middle slates of the Cumbrian mountains! … It has no tall chimneys, nor dense volumes of sulphureous smoke.75

The Builder argues that graphite’s economic success was based on its close relationship to the visual. The pencil-manufacturing industry in the bucolic Lake District was distinct from the sulphurous factories of Manchester, as sketches and paintings of Cumbria’s awe-inspiring valleys and mountains were different from those of Coalbrookdale. Because the Borrowdale mine was located in an area whose economy depended on its natural scenery, the status of pencil manufacturing was based on the absence of industrial markers. Natural beauty was, as the article implies, a condition of the pencil’s existence in both the production and the use of the tool.

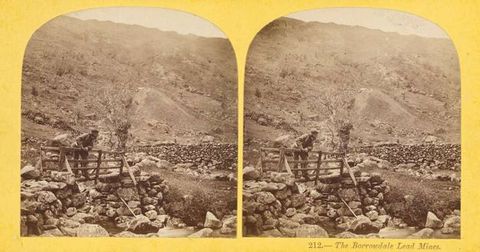

The tension between rural landscape and industrial infrastructure can be seen in a stereoscopic view of the Borrowdale mine published in 1860, contemporaneously with The Builder article (fig. 19). The photograph shows the barren hillside around the mine, a rocky expanse dotted with some small scraggly trees. There is a glimpse of a sorting house, a winding shaft head, and a wooden aqueduct. These constructions are obscured by the large spoil heap in the centre of the composition, with a cascade of textured rocks making its way down the slope. Below the mine workings, a man leans over a small bridge, looking into the water below. Wearing a cloth cap and worn suede shoes, he could be any rural working figure. We see no evidence of active labour. Instead, like the earlier print of Loutherbourg’s painting, the photograph uses the subterranean nature of the mine workings to suppress its “congruity to a coal-pit”, to borrow a phrase from The Builder. The final closure in 1891 of the Borrowdale mine, exhausted of its singular mineral, marked the end of the troublesome contradiction between the artistic function of the graphite pencil and the waste-strewn landscape from which it derived.

This is a study of beginnings: the start of Turner’s career, the graphite substrate that laid the ground for future painting, and the origin of the graphite pencil itself. At the same time, a consideration of this early encounter between Turner and Britain’s extractive industry is inevitably informed by the modern reception of Turner’s late work as an exemplar of the transition to modernity in both subject matter and stylistic approach.76 As is well established, Turner engages strongly with British industrialisation in his work, as evidenced by the subject matter of early works, including the aforementioned A Limekiln, Possibly at Briton Ferry in South Wales and Tintagel Castle, Cornwall, and by the subject and stylistic approach of his late paintings, including the canonical Rain, Steam, and Speed and Keelman Heaving Coals by Moonlight (1835) (fig. 20). Scholars such as Sarah Gould have suggested that the stylistic innovation of Turner’s later oil paintings engages with the material shifts in atmosphere occasioned by the Industrial Revolution.77 Turner’s encounter with the graphite mine predated the fog and clouds of his later work by decades. While there was anxiety in the late eighteenth century about the quickening pace of industrialisation, its drastic environmental consequences had not yet overwhelmed England when Turner worked in the Lake District.78 Yet, as Ruskin’s Ethics of Dust and the article in The Builder attest, there was an awareness at the time that coal and graphite are born from the same fossilised carbon deposits. Difficult labour and piles of extractive waste were endemic to both commercial enterprises. At the turn of the nineteenth century, despite the dramatically different economic landscapes in which they were located—the one of industrial production and the other of natural tourism—the cycles of extraction and depletion that produced both coal and the graphite pencil had already set in motion the major climatic changes that are evident in the murky skies of Turner’s paintings of the 1830s and 1840s. Just as Turner’s impasto gives physical form to murky atmospheres, so does the stylisation of his drawings around the Borrowdale mine manifest the unseen subterranean layers of the landscape. From the graphite mines of Cumberland to the coal smoke above the capital city, Turner’s works encompass the full cycle of extractive pollution.

76

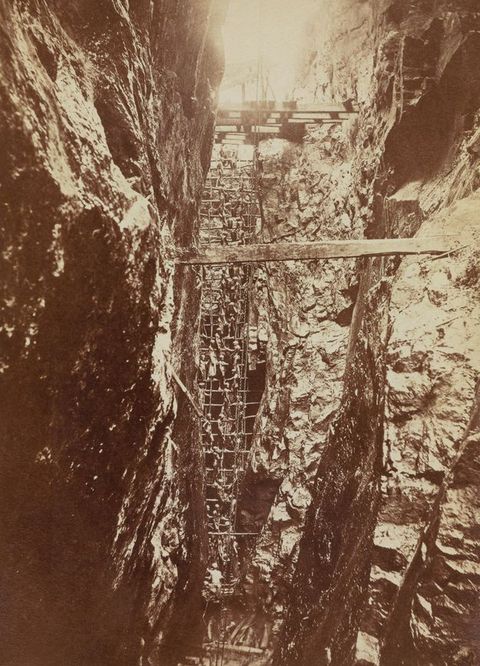

By the end of Turner’s life, the growth of the British Empire had loosened the connection between graphite mining and sites of artistic production. In the 1880s the Keswick pencil factory was using graphite mined in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), a British colony since the mid-nineteenth century, rather than locally mined graphite.79 Almost a century after Turner’s first journey to the Lake District, and as the workings at Borrowdale dwindled, a series of images appeared in the 1886 Colonial and Indian Exhibition in London advertising the products and process of Sri Lankan graphite mining. A photograph showing dozens of young workers on a long wooden ladder in a steep crevasse opened up the depths of a graphite mine to public scrutiny (fig. 21). A vertical chain bisects the upper and lower edges of the image, a line with no ends that accentuates the dangerous depth of the workings. The exploitation of human labour that lay behind the production of this valuable material, quantified as imperial achievement, is clearly visible.80 In 1899 the photograph was reproduced in The Queen’s Empire, a compilation of photographs that celebrated the British Empire at its height. “Now that the deposits of plumbago in Cumberland have been practically worked out”, the accompanying caption reads, “it is fortunate that other parts of the Empire, notably Canada and Ceylon, are able to supply the public demand”.81 The artistic choice of distance in Turner’s view of the graphite mine had become geographical reality.

79

Acknowledgements

I appreciate the feedback and support from the editorial team at British Art Studies and the anonymous reviewers. I am also grateful for Michael Lobel’s early support as I conceptualised this project. My sincere thanks go to Zoë Dostal, Katherine Fein, and Michaela Haffner for their insightful feedback on many drafts. Research for this work, including an important trip to Borrowdale, was supported by a fellowship from the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art.

About the author

-

Tobah Aukland-Peck holds a PhD in art history from the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. Her current book project on British art and extraction details how representations of coal mining, oil drilling, and stone quarrying subjects in twentieth-century Britain joined experimental art-making practices with pressing issues of labour, class, and environmental degradation. She has written about energy use, class, and environmental disaster in recent work published in Grey Room, the Open Library of Humanities Journal, and Oxford Bibliographies.

Footnotes

-

1

A. J. Finberg, custodian of the Turner Bequest in the early twentieth century, gave titles to the sketches based largely on content. In this case, however, the title was derived from Turner’s own notation. ↩︎

-

2

Turner’s 1797 trip to the Lake District coincided roughly with the coining of the word “graphite”, which was first suggested in 1789 by the German geologist Abraham Gottlob Werner. Given the very recent shift in terminology, Turner himself would have used “blacklead” or “lead” to describe the substance. To save confusion, I will use the word “graphite” throughout. ↩︎

-

3

This approach was pioneered by Francis Klingender in his 1947 study of British industrial history: see Francis Klingender, Art and the Industrial Revolution (London: Royle Publications, 1947). In Turner studies, an important early work is William S. Rodner, J. M. W. Turner: Romantic Painter of the Industrial Revolution (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997). ↩︎

-

4

On Turner and industrial cities see Stephen Daniels, “The Implications of Industry: Turner and Leeds”, Turner Studies 6, no. 1 (1986): 10–17; Stephen Daniels, “Reforming Landscape: Turner and Nottingham”, in Land, Nation and Culture, 1740–1840: Thinking the Republic of Taste, ed. Peter de Bolla, Nigel Leask, and David Simpson, 15–21 (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005); and David Hill, Turner and Leeds (Huddersfield: Jeremy Mills, 2008). ↩︎

-

5

James Finch, “Industrial Sublime”, in Turner’s Modern World, ed. David Blayney Brown et al. (London: Tate, 2020), 35. ↩︎

-

6

Celina Fox, who studies technical processes as a factor in artistic development in this period, addresses Turner’s engagement with mechanical detail and tools. Celina Fox, The Arts of Industry in the Age of Enlightenment (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2009), 442–43. For the history of Turner’s interest in geology see James Hamilton, Turner and the Scientists (London: Tate, 1998). Rodner traces some of Turner’s personal relationships with industrial patrons: see Rodner, Romantic Painter of the Industrial Revolution. ↩︎

-

7

Stephanie O’Rourke addresses similar questions of the relationship between empiricism and the senses in contemporaneous artistic experiments related to scientific innovations. Stephanie O’Rourke, Art, Science, and the Body in Early Romanticism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022). ↩︎

-

8

While the present article does not attend directly to Turner’s paper, a useful overview of his sourcing and use of drawing papers can be found in Peter Bower, Turner’s Papers: A Study of the Manufacture, Selection and Use of His Drawing Papers, 1787–1820 (London: Tate, 1990). More recently, scholars have studied eighteenth- and nineteenth-century British paper making in the context of labour, global trade, and industrial production. See Zoë Dostal, “Rope, Linen, Thread: Gender, Labor, and the Textile Industry in Eighteenth-Century British Art” (PhD diss., Columbia University, 2024). ↩︎

-

9

Addressing this point in a modern context, Siobhan Angus and Monica Bravo have argued that the origination of photographic materials in extractive practices must be taken into any account of the landscape image. See Siobhan Angus, Camera Geologica (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2024); and Monica Bravo, “Mercury Is a Messenger: Photography’s Dependence on Quicksilver and Mining Labor”, American Art Journal 39, no. 1 (Spring 2025): 16–25. ↩︎

-

10

Walter Thornbury, The Life of J. M. W. Turner, R.A. (London: Hurst and Blackett, 1862), 214. ↩︎

-

11

Turner scholar David Hill tentatively identified the mine in Road over the Fells as a small operation near Grasmere, ten miles from Borrowdale. On my own visit, I found the topography around the Grasmere mine markedly different than the hills depicted by Turner. Moreover, the Grasmere lead mine ceased production in 1573: see John Adams, Mines of the Lake District Fells (Skipton: Dalesman, 1995), 139. While this does not preclude the identification, given Turner’s notation of the site as a mine and the smoke in the chimney, the sketch may well be of another nearby workings. Andrew Wilton concludes that this is a graphite mine rather than a lead (metal) mine but, in a further layer of obscurity about the Lake District’s industrial history and the terminology around the material, the possibility remains that this was primarily a site of lead extraction. See Andrew Wilton, “A Road over the Fells, with a Lead Mine 1797 by Joseph Mallord William Turner”, catalogue entry, August 2010, in J. M. W. Turner: Sketchbooks, Drawings and Watercolours, ed. David Blayney Brown, Tate Research Publication, November 2014, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/jmw-turner/joseph-mallord-william-turner-a-road-over-the-fells-with-a-lead-mine-r1150213; and David Hill, Turner in the North (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1996), 121. ↩︎

-

12

Henry Petroski identifies the first mention of Cumbrian graphite as Konrad Gesner’s De rerum fossilium lapidum (1565). Henry Petroski, The Pencil: A History of Design and Circumstance (New York: Knopf, 2010), 38. Ian Tyler dates the first underground workings in Borrowdale mine to the 1560s: Ian Tyler, Seathwaite Wad and the Mines of the Borrowdale Valley (Carlisle: Blue Rock Publications, 1995), 65. The seam could also have been discovered by copper prospecting: see Eric H. Voice, “The History of the Manufacture of Pencils”, Newcomen Society 27, no. 1 (1950): 132. ↩︎

-

13

Tyler, Seathwaite Wad, 67. ↩︎

-

14

Petroski, The Pencil, 49. ↩︎

-

15

William Camden, Britannia, newly translated into English with large additions and improvements, ed. Edmund Gibson (London: F. Collins, 1695; orig. pub. 1607). Early English Books Online 2, University of Michigan Library Digital Collections, https://name.umdl.umich.edu/B18452.0001.001. ↩︎

-

16

Petroski, The Pencil, 17. ↩︎

-

17

Also spelled “wadd” or “wadt”. ↩︎

-

18

Petroski, The Pencil, 48. ↩︎

-

19

Graphite was “bismuth” in German and a crayon d’Angleterre in France. Petroski, The Pencil, 48. ↩︎

-

20

Amy Lax and Robert Maxwell, “The Seathwaite Connection, Some Aspects of the Graphite Mine and Its Owners”, National Trust Annual Archaeological Review 7 (1998/99): 19. ↩︎

-

21

Richard Taws, “Conté’s Machines: Drawing, Atmosphere, Erasure”, Oxford Art Journal 39, no. 2 (2016): 243–66. ↩︎

-

22

T. C. Archer, “Notes on the Raw Materials Used by Artists as Seen in the Exhibition”, in The Art Journal Illustrated Catalogue of the International Exhibition (London: James S. Virtue, 1862), 225. ↩︎

-

23

For studies in nineteenth-century oil paint see Kirsty Sinclair Dootson, “The Texture of Capitalism: Industrial Oil Colours and the Politics of Paint in the Work of G. F. Watts”, British Art Studies 14 (2019), DOI:10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-14/kdootson. ↩︎

-

24

“Genuine Black Lead Pencil”, Oracle and the Daily Advertiser, 25 March 1805; “British Artists’ Suppliers, 1650–1950”, National Portrait Gallery, https://www.npg.org.uk/research/programmes/directory-of-suppliers. ↩︎

-

25

The broadsheet published letters “from first-rate artists” praising their pencils. The advertisement appeared in William Buchanan, Memoirs of Painting, vol. 2 (London: R. Ackermann, 1824). Other advertisements for Cumberland lead include Reeves and Sons and Dobbs & Co., “Pure Cumberland Lead Pencils”, Derbyshire Courier, 1 September 1849; “Dobb’s Genuine Cumberland and Prepared Lead Pencils”, Dover Telegraph, 9 January 1836. ↩︎

-

26

“The Useful and the Useless”, Sun, 31 October 1837. ↩︎

-

27

“It is only towards the end of his life that we can ascertain from which artists’ colourmen Turner obtained his materials”. Joyce Townsend, How Turner Painted: Materials and Techniques (New York: Thames & Hudson, 2019), 28. London’s graphite was sourced from a monthly market of Borrowdale graphite on Essex Street. ↩︎

-

28

See Townsend, How Turner Painted, 22; Andrew Wilton, “The 1797 North of England Tour, Related Works and Other Subjects 1797–1801”, November 2013, in J. M. W. Turner: Sketchbooks, Drawings and Watercolours, ed. Brown, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/jmw-turner/the-1797-north-of-england-tour-related-works-and-other-subjects-r1150314. ↩︎

-

29

Hill, Turner in the North, 2. ↩︎

-

30

Andrew Wilton, Turner as Draughtsman (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2006), 24. See also Timothy Wilcox, “Which Way to Watendlath? Differing Approaches to Painting the Lake District around 1800”, in The Solitude of Mountains: Constable and the Lake District, ed. Stephen Hebron (Grasmere: Wordsworth Trust, 2006), 10. ↩︎

-

31

Hill, Turner in the North, 2. ↩︎

-

32

The Yale Center for British Art recently retitled this painting, which had previously been called Limekiln at Coalbrookdale. Instead of relating it to Turner’s trips in Coalbrookdale in 1794 and 1795, as the scholarly consensus had been up to this point, YCBA researchers now believe that A Limekiln, Possibly at Briton Ferry in South Wales was painted after Turner’s time in Wales in the summer of 1795. ↩︎

-

33

William Gilpin, Observations, Relative Chiefly to Picturesque Beauty, Made in the Year 1772, on Several Parts of England, Particularly the Mountains, and Lakes of Cumberland, and Westmoreland (London: R. Blamire, 1788). ↩︎

-

34

Gilpin, Observations, 213. ↩︎

-

35

Charlotte Klonk argues that attention to geological history increased significantly in this period, and describes the growing influence of geological surveys in landscape art. Charlotte Klonk, Science and the Perception of Nature: British Landscape Art in the Late Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Centuries (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1996), 74–80. ↩︎

-

36

Gilpin, Observations, 213. ↩︎

-

37

Gilpin also mentions Farington’s drawing of Borrowdale*.* Gilpin, Observations, 24. Farington was an important mentor of Turner’s during this period: see Luke Herrmann, “Joseph Farington (1747–1821) and the young J. M. W. Turner (1775–1851)”, British Art Journal 16, no. 1 (Summer 2015): 43–46. Farington had lived in the Lake District and was known for his prints of the local landscape, which were published as a series of aquatints in 1789. Joseph Farington, Views of the Lakes, etc. in Cumberland and Westmorland (London: William Byrne, 1789). ↩︎

-

38

Thomas Gray, Journal of a Visit to the Lake District in 1769, ed. H. W. Starr, Thomas Gray Archive, 1088, https://www.thomasgray.org/texts/diglib/primary/TWS_1971iii. ↩︎

-

39

John Housman, A Descriptive Tour (Carlisle: Francis & Jeremiah Jollie, 1800), 13. See also William Hutchinson, An Excursion to the Lakes in Westmoreland and Cumberland, August, 1773 (London: Printed for J. Wilkie and W. Goldsmith, 1774); Joseph Palmer, A Fortnight’s Ramble to the Lakes in Westmoreland, Lancashire, and Cumberland (London: Hookham and Carpenter, 1794); and Ann Radcliffe, Observations during a Tour to the Lakes of Lancashire, Westmoreland, and Cumberland (London: G. G. and J. Robinson, 1795). ↩︎

-

40

John Hudson, A Complete Guide to the Lakes (London: Longman, 1843), 80. ↩︎

-

41

The owners of the Borrowdale mines often suspended mining operations to control prices by limiting the amount of graphite available in the open market. ↩︎

-

42

George Smith, “Report of a Visit to the Black Lead Mines above Seathwaite”, Gentleman’s Magazine, February 1751, https://www.lakesguides.co.uk/html/LakesTxt/G7510051.htm. ↩︎

-

43

Gilpin, Observations, 213. ↩︎

-

44

In the twentieth century, depictions of slag pickers (also known as coal searchers or coal pickers) became more common as visual evidence of hardship in periods of economic conflict and deindustrialisation: see, e.g., the work of Bill Brandt and John Latham, which I address in “Mineral Landscapes: British Art and Extraction, 1937–75” (PhD diss., The Graduate Center, The City University of New York, 2024). ↩︎

-

45

Cotman’s drawing was included in the 1983 exhibition Coal: British Mining in Art 1680–1980, an important survey of the relationship between British art and extractive industry. ↩︎

-

46

David Hill, Coal Shaft on Lincoln Hill at Coalbrookdale, catalogue entry, The Cotman Collection, Leeds Art Gallery, December 2017, https://cotmania.org/works-of-art/41882. ↩︎

-

47

This was also the case for Romantic poetry. Despite the fact that his 1815 poem “Yew-Trees” celebrates a group of ancient yews in Borrowdale directly below the graphite mine, William Wordsworth’s 1834 Lakes guidebook does not mention any extractive workings. William Wordsworth, Poems, vol. 1 (London: Longman Hurst, Rees, Orme & Brown, 1815), 302. The framing of the site as undisturbed is an ironic oversight of the industrial activity that took place a mere 1,000 feet away. ↩︎

-

48

See Ann Bermingham, Landscape and Ideology (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986), 75. ↩︎

-

49

Stephen Copley, “'William Gilpin and the Black-Lead Mine”, The Politics of the Picturesque: Literature, Landscape and Aesthetics since 1770, ed. Stephen Copley and Peter Garside (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 42–61. ↩︎

-

50

Onno Oerlemans*, Romanticism and the Materiality of Nature* (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2002). ↩︎

-

51

Loutherbourg’s painting Labourers Near a Lead Mine was shown at the 1783 Royal Academy Exhibition. Algernon Graves, The Royal Academy of Arts: A Complete Dictionary of Contributors and Their Work from Its Foundation in 1769 to 1904 (London: Henry Graves, 1905), 301. ↩︎

-

52

Rüdifer Joppien, Philippe Jacques de Loutherbourg, RA, 1740–1812 (London: Greater London Council, 1973), catalogue no. 49. On the identification of the painting see also Stephen Daniels, “Loutherbourg’s Chemical Theatre: Coalbrookdale by Night”, in Painting and the Politics of Culture: New Essays on British Art, 1700–1850, ed. John Barrell (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993), 214; Fox, The Arts of Industry, 435–36; and Olivier Lefeuvre, Philippe-Jacques de Loutherbourg, 1740–1812 (Paris: Arthena, 2012), 252. ↩︎

-

53

Marcia Pointon, “Turner: Language and Letter”, Art History 10, no. 4 (December 1987): 467–74. ↩︎

-

54

See Wilton, Turner as Draughtsman, 65. ↩︎

-

55

John Ruskin, The Laws of F**ésole (Orpington: George Allen, 1877), 40. ↩︎

-

56

On detail and representation in the picturesque sketch see Ann Bermingham, “System, Order, and Abstraction: The Politics of English Landscape Drawing around 1795”, in Landscape and Power, ed. W. J. T. Mitchell (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994), 77–101. ↩︎

-

57

Jonathan Otley, A Descriptive Guide to the English Lakes (Keswick: Jonathan Otley, 1842), 180. ↩︎

-

58

Another iteration of cultural distance was the role of London-based Jewish communities in the pencil trade. The Builder recounts stories of Jewish merchants coming up to the Lake District to do business with the mine and the pencil factory. The article details the reaction of the local people to their so-called foreign appearance and eating practices. “Visit to a Keswick Pencil Mill”, Builder, 25 August 1866, 624. ↩︎

-

59

See David Solkin, ed., Art on the Line: The Royal Academy Exhibitions at Somerset House 1780–1836 (London: Paul Mellon Centre, 2001); and David Stacey, Art and Industry: Seven Artists in Search of an Industrial Revolution in Britain (London: Unicorn, 2021), 3–7. ↩︎

-

60

“Graphite (Wad) Mine on Seathwaite Farm, Borrowdale”, National Trust Heritage Records Online, https://heritagerecords.nationaltrust.org.uk/HBSMR/MonRecord.aspx?uid=MNA119961. ↩︎

-

61

Lax and Maxwell, “The Seathwaite Connection”. ↩︎

-

62

“Picture List”, Kingston Lacy Estate, Dorset, National Trust, https://www.nationaltrustcollections.org.uk/object/1251988. ↩︎

-

63

Archer, “Notes on the Raw Materials Used by Artists”, 227. ↩︎

-

64

For a brief history of the Turner Bequest see Alan Crookham, “The Turner Bequest at the National Gallery”, in Turner Inspired: In the Light of Claude (London: National Gallery, 2012), 52–65. ↩︎

-

65

On the evolution of Turner’s painting process see, e.g., Ian Warrell, ed., J. M. W. Turner (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2007), 19. Turner’s public varnishing days date back to the 1830s: see Leo Costello, “‘This Cross-fire of Colours’: J. M. W. Turner (1775–1851) and the Varnishing Days Reconsidered”, British Art Journal 10, no. 3 (Winter 2009–Spring 2010): 56–68; and Rebecca Hellen, “‘Three Days or More …’: Turner’s Varnishing Day Practice and the Physical Evidence”, British Art Journal 15, no. 2 (Winter 2014–15): 47–53. ↩︎

-

66

Archer, “Notes on the Raw Materials Used by Artists”, 227. ↩︎

-

67

John Ruskin, The Ethics of Dust (1865), in The Works of John Ruskin, ed. E. T. Cook and Alexander Wedderburn, vol. 18 (London: Allen, 1903–12), 218, 219. ↩︎

-

68

Ruskin, The Ethics of Dust, 219. ↩︎

-

69

In his later work, Turner engaged with another energy source: whale oil (a direct competitor to coal in household lighting). His series of Whalers paintings (circa 1845–46), depicting British whaling ships, show the process of procuring oil. Jason Edwards suggests that Turner’s interest in the whaling industry was not limited to his subject matter and the patronage of his work by a whaling products importer. Turner also used spermaceti, a waxy substance from the head of the sperm whale, in the preparation of his paintings. Jason Edwards, “Turner and the Whal/ers, c.1845–46”, in Turner and the Whale, ed. Jason Edwards (Oxford: Osprey, 2017), 84–85. ↩︎

-

70

For more on the development of Coalbrookdale as the centre of industrial imagery see Daniels, “Loutherbourg’s Chemical Theatre”. ↩︎

-

71

Monthly Magazine, July 1798, quoted in “Morning amongst the Coniston Fells, Cumberland”, Tate, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/turner-morning-amongst-the-coniston-fells-cumberland-n00461. ↩︎

-

72

See Hill, Turner in the North, 136. In 1798 Turner looked more closely at metal smelting procedures in his sketches of the Cyfarthfa iron-smelting works in Merthyr Tydfil, part of a commission from Anthony Bacon: see Brown et al., eds., Turner’s Modern World, 32. ↩︎

-

73

Voice emphasises the close connection between copper and graphite. Voice, “The Manufacture of Pencils”, 132. ↩︎

-

74

“Visit to a Keswick Pencil Mill”, Builder, 624. ↩︎

-

75

“Visit to a Keswick Pencil Mill”, Builder, 624. ↩︎

-

76

Lawrence Gowing famously identified Turner as a proto-modernist in the 1966 Museum of Modern Art exhibition Turner: Imagination and Reality. See Lawrence Gowing, Turner: Imagination and Reality (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1966); and also Jonathan Crary, “Memo from Turner”, Artforum 46, no. 10 (2008): 199. This association is challenged as anachronistic by some Turner scholars: see Sam Smiles, The Late Works of J. M. W. Turner: The Artist and His Critics (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2020). ↩︎

-

77