“A Gift with Strings Attached”

“A Gift with Strings Attached”: Deciphering a Jacobean Watch

-

Kate Anderson

-

Tacye Phillipson

-

Christina J. Faraday

-

Gerda Stevenson

-

Jane Eade

-

Joseph James Ellis

-

Emma Stead

-

Brianna Guthrie

Introduction by

-

Kate AndersonSenior Curator, Portraiture (Pre-1700)National Galleries of Scotland

Introduction

The Ramsay-Kerr Watch in the collection of the National Museum of Scotland is revered as an exceptional, extant seventeenth-century timepiece (fig. 1). Equally, it is a multifaceted and evocative object that gives us insight into early modern experiences with time, astrology, patronage, relationships, and court politics. Commissioned as a high-status gift, the watch illuminates the interactions between three Scotsmen: the king, his favourite, and a royal watchmaker, and as such is a rich springboard for academic and curatorial inquiry.

The multi-author format of this feature brings together specialists working across disciplines from horology, art history, court studies, and religious history. The contributors’ diverse expertise presents innovative approaches to analysing and interpreting the materiality and iconography of this extraordinary object. From unpacking the technical capabilities of the watch and the skill of its maker, and uncovering the familial and religious symbolism, to interpreting its significance as an object representing queer histories, the responses reframe the watch and situate it within its historical, political, and cultural contexts. The feature demonstrates how one object can be interrogated to draw out multiple themes and narratives that are pertinent to the ambition of this special issue.

This feature has also inspired responses that creatively animate the watch, including a commissioned poem and a short film capturing the watch being handled and opened to reveal its complex form, function, and artistry.

Contribution by

-

Tacye PhillipsonSenior Curator of ScienceNational Museums Scotland

The Watch as a Watch

Watches, miniature timepieces powered by a spring and designed to be carried or worn as adornment, were first made in the late fifteenth or early sixteenth century. By the early decades of the seventeenth century, they were expensive and unreliable technical luxuries but readily available in London—at a price. They were rare enough that it was noted Guy Fawkes had one on his person when he was arrested in 1605, but were available to the extent that he and his co-conspirator Thomas Percy had been able to buy it the day before to time the burning of the touchwood.1

1In his satirical publication The Gull’s HornBook, first published in 1609, Thomas Dekker mentions the ostentatious setting of a watch by the clock of St. Paul’s Cathedral: “you may here have fit occasion to discover your watch, by taking it forth and setting the wheels to the time of Paul’s … The benefit that will arise from hence is this, that you publish your charge in maintaining a gilded clock; and withal the world shall know that you are a time pleaser”.2 This parody of manners illustrates the role of watches in the social spectrum as an item of conspicuous ownership. It also accurately reflects that watches of the period were not good timekeepers; they varied by maybe half an hour a day and required daily resetting (the cathedral clock itself would have been frequently reset according to the sun).

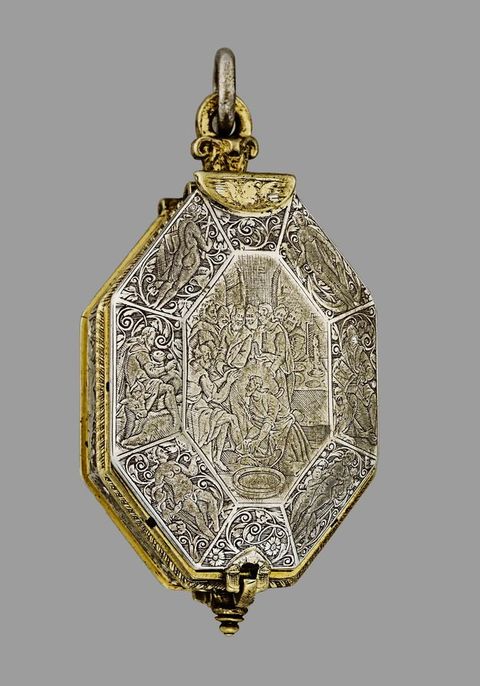

2This watch, signed by the Scottish maker David Ramsay, who had probably learned his horological craft in France, has a mechanism of gilded brass within a silver case, which would have been made and decorated by different craftsmen from those who made the watch movement itself.3 When not in use, it was further protected by a black mammalian shagreen case with silver pinhead decoration and pink silk lining (fig. 2). It was a luxury item, even by the standards of watches of the period, with its ornate silver case and many technical features beyond telling the time of day. Its construction of silver rather than gold, and its elaborate workmanship, potentially contributed to its long-term survival; the incentive for reusing materials from gold and jewelled watch cases was significantly higher.

3

This is one of several watches that have similarities to each other. The most closely correlated known items are two watches also signed by Ramsay with nearly identical functionality and allied decoration: one, with a plain silver outer storage case, is on loan to the Victoria and Albert Museum (figs. 3–5), while the other is in the John C Taylor Collection (fig. 6).4 Each has an engraved portrait of James VI and I after Simon de Passe inside the cover and is engraved with his royal arms but, unlike the Kerr watch, they do not have the arms or other clear indication of the recipient of these presumably royal gifts. Both watches, and a star-shaped watch by Ramsay that is now in the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers’ collection at the Science Museum in London, have ornamentation signed by Gérard or Gerhart de Heck, and on all three Ramsay’s name is followed by “Scotus” or “Scottes”.5 There is also a watch, signed “David Ramsay Scotus” in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, which only tells the hour, without any additional functionality, and where the case is engraved with the arms of Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales.6 The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, has a mechanism signed by Ramsay (without the national designation “Scotus”) that has similar functionality and dials to the three James VI and I watches and has been remounted into a slightly overlarge case.7

4

The differences between the watches, including the engraving style of Ramsay’s name, may reflect different craftsmen. The presence of multiple languages, including French, Latin, English, and Dutch, across the three James VI and I watches is intriguing, raising questions of how far it reflected the commissioners’ request or the craftsmen’s decision or familiarity with the languages. On the Kerr watch, December is marked “Dcbe”, and March as “Mart”, choices that are unexpected for a native English speaker. On the outside of the case, the biblical engravings are identified as “Iohnnes XIII Chapter” on one side but “Iohnnes XIII Capittel” on the other, potentially indicating a Dutch design. Gérard de Heck, who signed other watch cases used by Ramsay, though not the Kerr watch, was Flemish and recorded as living in the parish of St Martins-in-the-Fields in London around 1618.8

8The Kerr watch, as was usual for the time, has a single hand on a dial marked with the hours and half hours. The upper large disc has an arrowhead indicating the day of the month. On this disc are engraved English abbreviations for the months of the year indicated with the (probably replaced) pointer, a reminder of the number of days in each, and the symbol of the zodiac that best aligns with the month in the Julian calendar. The smaller apertures show the phase of the moon, its age in days, the day of the week (in English) adorned with its ruling god, and the “planetary hours”, the same set of seven ruling gods or heavenly bodies as shown on the days of the week (fig. 7).9 The opaque front cover would have been opened each time the watch was consulted: this was not a device designed to tell the time at a quick glance.

9

The presence of astrological indications such as the planetary hours is surprising on watches associated with James VI and I, the author of Daemonologie, in which he stigmatised astrology of the sort this relates to as “utterlie unlawful to be trusted in, or practized amongst christians, as leaning to no ground of naturall reason: & it is this part which I called before the devils schole”.10 It may be that this feature was primarily decorative and had been installed simply because it was technically feasible, as part of an elaborate mechanism, and not specifically tailored to the taste of the king. It is also likely that the astrological indications had faded into custom and were not noted as astrological, just as we seldom think of Saturn on Saturday these days. Though later in the seventeenth century, Quakers were sufficiently conscious of the association of day names with pagan gods to instead call them first to seventh day.

10All the extra indications on this watch, termed “complications”, are shown by dials that rotate at a fixed speed compared to the hours of the day. The complications were all accomplished by means of straightforward gears run by the main timing mechanism of the watch. This relationship is reflected in the design of the watch: the principal mechanism is located between the two main plates, as for a simpler watch that showed only the hours. The extra gearing to achieve the complications is all situated beneath the dial plate and would have increased the friction that the spring needed to overcome for the watch to run (fig. 8). A square shaft in the middle of each dial enables the indicator to be set by means of a watch key. All the complications on this watch can be seen in watches signed by different makers, so it is unlikely that Ramsay invented any of them. While he would have been personally capable of making the watch mechanisms, his other time-consuming activities at the royal court mean that he probably coordinated other skilled makers to produce the mechanisms as well as the cases.11 Features that were present in some other watches of the period but not on this one include an hour strike and an alarm.

11

When it was made, the Kerr watch would have been an item of conspicuous luxury, with the mechanism and functionality not appearing to be fully personalised to the customer, in contrast to the engraving on the case. It has experienced a degree of alteration and damage over the centuries but still gives a clear indication of what it was like visually and mechanically when new, and of its contrast to our modern expectations for a watch as a reliable timekeeper.

Contribution by

-

Christina J. FaradayAffiliated Lecturer in the History of ArtUniversity of Cambridge

Accuracy, Astrology, and Authority

As the first Master of the London Clockmakers’ Company, one of the oldest clockmaking guilds in the world, David Ramsay is easily slotted into traditional narratives about the horological revolution: the steady march towards ever greater expertise and precision in clockmaking.12 And yet a close look at the watch Ramsay made around 1615 as Chief Clockmaker to James VI and I reveals the complexity of early modern attitudes to time and the period’s great plurality of approaches to timekeeping.

12On opening the engraved silver lid, the viewer discovers that the dial recording the hours is only the third largest of the seven indicators embedded in a gilded oval plate. The hour dial is towards the bottom, with Roman numerals from I to XII and only a single hour hand, representing the smallest unit of time measured by the watch. Although it is surprising to us now, this was not unusual in the early seventeenth century. Minute hands had begun to appear on clocks in the 1580s, following the invention of a more precise regulator known as a cross-beat escapement but, until the pendulum was employed in 1656, mechanical clocks were accurate to around fifteen minutes per day at best.13 The difficulty of imposing uniformity on tiny handmade components made accuracy at smaller scales even less feasible, and minute hands become universal on watches only after 1700.14 More generally, people did not lead their lives by the minute, and daily activities were organised on schedules more approximate than our own.

13What Ramsay’s watch lacks in exactitude it makes up for in diversity of timescales. The largest dial gives the month and date. A circular silver plate is divided into segments labelled with the names of the months, plus the number of days in each and an image to represent the corresponding sign of the zodiac. A central silver hand identifies the current month, while a heart-shaped “bug” on the central plate tracks the date on the outer ring. To the left, a wedge-shaped opening displays the day of the week and its corresponding planetary ruler according to astrological theory; for Thursday this is a representation of Jupiter. To the right is a rectangular opening for the lunar date, and below that a circular display, now abraded, probably once showing the phases of the moon.15 In the lower right, next to “IIII” on the hour dial, a further wedge-shaped aperture, badly tarnished, probably shows the planetary hour.16

15Collectively, the seven different indicators provide a wealth of information corresponding to a variety of timescales and astronomical principles. In 1615 England was still using the Julian calendar (despite the introduction of the Gregorian calendar in neighbouring countries in 1582). This system is broadly based on the position of the sun in relation to the earth, but time can also be measured by the lunar cycle, which produces months roughly twenty-seven days in length, incommensurate with the longer months of the solar calendar. According to astrological theory, each of the seven planets governed one of the days of the week, as well as individual hours in the day. In the philosophy known as judicial astrology, such information could be employed to identify the most propitious time for particular actions and to predict future events. The inclusion of the lunar date and planetary hour thus gives enhanced significance to the engraved astrological imagery, its myriad dials seemingly designed to facilitate calculations associated with judicial astrology.

When the watch was made around 1615, the practice of astrology was still some decades away from its popular peak.17 Yet astrology was already an essential part of the educated worldview. Astrologers had been consulted by English monarchs and their courtiers throughout the sixteenth century, on everything from medical concerns to the relocation of lost property. Meanwhile, provincial practitioners served wider publics, and astronomical principles were disseminated through pocket almanacs.18 Although James VI and I himself condemned the practice of judicial astrology as “utterlie unlawful to be trusted in, or practized amongst Christians, as leaning to ground of natural reason; … the devils schole”, several of his courtiers employed astrological practitioners as their personal physicians.19 At the trial of Robert Kerr and Frances Howard for the murder of Thomas Overbury, it emerged that Howard had consulted the notorious astrologer Simon Forman, possibly in connection to her relationship with Kerr. The revelation was probably more scandalous for the clandestine nature of the affair and subsequent murder trial than for the astrological connection specifically.20

17Astrology was not generally seen as illicit, but the watchmaker Ramsay was reputed to have more sinister interests. By the 1620s he had fallen in with the Rosicrucians, an esoteric philosophical movement concerned with magic, alchemy, and other mystical subjects. In 1626 Ramsay presented a letter to Charles I proposing a meeting with the “President of the Rosy Cross”, at which it was promised that the king would discover the secret of generating riches and religious triumphs. When the author was unmasked as the radical preacher and heretic Philip Ziegler, Ramsay’s reputation was badly bruised, although apparently not enough to make him abandon the Rosy Cross altogether, as he seems to have introduced his nephew to the movement in the 1630s.21 Ramsay is also associated with dowsing, or divination with rods. The memoirs of the astrologer William Lilly describe “one winter’s night” around 1634 when he and Ramsay sought buried treasure in the cloister of Westminster Abbey. They uncovered only a coffin too light to contain treasure, but when they re-entered the abbey, “upon a sudden … so fierce, so high, so blustering and loud a wind did rise, that we verily believed the west-end of the church would have fallen upon us; our rods would not move at all; the candles and torches, all but one, were extinguished, or burned very dimly”, a phenomenon they put down to “daemons”.22

21Watchmaking itself, and the associated subject of mathematics, were sometimes linked to the occult. Mathematics was often coupled with magic; John Dee, a major proponent of the subject, was an astrologer well known for his magical experiments. Meanwhile John Aubrey’s life of the Elizabethan mathematician Thomas Allen describes how a housemaid, “hearing a thing in a case [his watch] cry Tick, Tick, Tick, presently concluded that that was his Devill, and … threw it out of the windowe into the Mote (to drowne the Devill)”.23 In the literature of the period, however, clocks had other, less controversial, cosmic connections: God was often compared to a clockmaker, as the author of the great clock of the universe.24 The clock’s unidirectional chain of command, from the weight or spring to the wheels to the hand on the dial, also made it a perfect metaphor for authoritarian systems of governance.25 The well-ordered society was frequently compared to a clock, with the king as prime mover, directing the movements of the lesser “wheels” with authority and constancy:

2326This moving world, may well resembled be,

T’a Jacke, or Watch, or Clock, or to all three: 26

For, as they move, by weights, or springs, and wheeles,

And every mover, others mover feeles,

So doe the states, of men of all degrees,

Move from the lowest to the highest sees,

The lesser wheeles, have most celeritie,

The greatest move with farre more constancie,

And if there movings lowest wheeles neglect,

The greatest mover doth them all correct.

For, if the wheeles, had equall force to move,

The lowest would checke, the leading wheele above.

So, if there were, no difference in estates,

All would be lawlesse, yet al Magistrates:

Therefore hath Art, well ordered the thing,

That best resembles, Subjects and their King.27

If this watch was a gift from James VI and I to Robert Kerr, it can be framed as a pointed reminder of the king’s authority—an interpretation underscored by engraved portraits of the royal couple on the inside of the back lid. The years 1614–15 were a period of frustration for Kerr, who responded belligerently to the advancement of a new favourite, George Villiers, rebuking James for his neglect.28 If the watch was indeed given to Kerr at this time, the common connection between the clock and the monarch’s absolute power may have served to remind Kerr of his position as a mere subject, no matter how favoured.

28Contribution by

-

Gerda StevensonActor, Writer, and Director

Watch

Silver astronomical watch signed “David Ramsay Scotus, me fecit”, given by James VI and I to one of his favourites, Robert Kerr, first earl of Somerset, circa 1615.

I am a portable cosmos, but

in another time I was a mechanism

in more ways than one:

my wheels and pinions intricate

as the statecraft that conceived me,

a triangular transaction between king,

watchmaker, and earl, a balancing act

by three Scots at the heart of English power,

a gift with strings attached—loyalty the price

of possessing me, a pledge to bring peace

to that old fault line of warring nations,

renamed by King Jamie as “The Middle Shires”.

Ramsay, my maker, the foremost of his age,

knew all about war and ordnance,

apprentice to a gunsmith—his first trade—

he learned the alchemy of crucible and anvil,

taming his native geology, and understood well

that the bullet’s arc and a lasting career

are a calculation of timing.

Not so for the earl! I had to dangle on a chain

around Kerr’s neck, and for a while

our heartbeats rhymed, but a fall from grace

was always predicted on time’s chart

for the man whose flawless form

bewitched the king’s vision.

War and monarchs still rage and reign,

but Time is the Emperor, as the clockmakers say,

and I have served that cosmic realm

for longer than you ever will;

and can, still—if those white-gloved hands

that lift me from the shadows

choose to set me in motion again.

Contribution by

-

Jane EadeDirector of Heritage CollectionsVenerable English College, Rome

The Representation of Faith and Religion

This extraordinary watch was bequeathed to the museum by Sir Archibald Buchan-Hepburn, fourth baronet of Smeaton Hepburn as one of seven “relics” associated with Mary Queen of Scots and which had descended to Sir Archibald from his ancestor Lord Bothwell. The nature of its iconography and afterlife is as surprising as its origins as a gift from King James VI and I to his favourite, Robert Kerr, earl of Somerset.

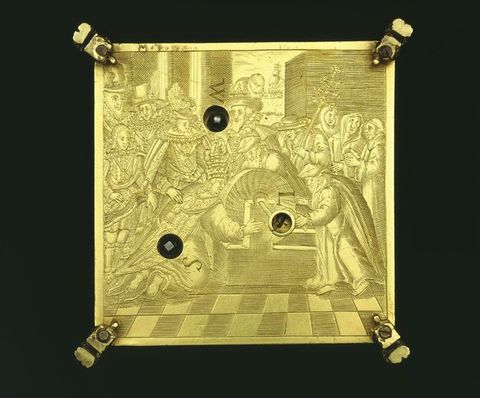

Viewed in the context of the Scottish Presbyterian Church and the equally devout Presbyterian upbringing of the king’s watchmaker, David Ramsay, it seems astonishing that King James would choose an image of Christ washing the feet of his disciples, with the Last Supper on the reverse, for the decoration of the case.29 It astonishes because engraving on metal of this scene from the Gospel of John was commonly associated with the reverse of papal medals and hence with the Roman Catholic Church (fig. 9). For example, a nearly contemporary watchcase by Edmund Bull of Fleet Street, which has the same iconography on each side, bears the arms of the recusant Catholic Wiseman family (fig. 10).30 It is therefore perhaps no surprise that, in its afterlife, the watch has come to symbolise not James’s own devotions but those of his Catholic mother, Mary Queen of Scots.

29

The case itself was likely imported, and indeed the engraving suggests a maker more attuned to printmaking than manufacturing medal dies.31 It can be compared to the cases signed “de Heck sculpt” for Gérard de Heck, a Dutch case engraver who signed two watches by David Ramsay.32 It has not been possible to trace the source of the engravings used, though the architectural setting of the Last Supper appears to be derived from a woodcut by the artist and printer Heinrich Vogtherr the elder, and the figures of Jesus and Peter from a woodcut by Virgil Solis, loosely copied in reverse from Dürer.33

31

The theology to which James adhered was that of the Scottish Reformers but he did not hesitate to call his faith Catholic. In his Apologie for the Oath of Allegiance … and Premonition of 1609 he wrote, “I am such a Catholike Christian, as beleeueth the three Creeds; that of the Apostles, that of the Councell of the Nice, and that of Athanasius”, but denied that the church had any earthly monarch “who cannot erre in his Sentence by an infallibility of Spirit”, just as he rejected what he called “new Articles of faith” such as transubstantiation.34 Indeed, a clock by Ramsay from around 1614, which is contemporaneous with the watch, is engraved on the base with an image of King James VI and I and his sons Henry Frederick and Charles holding the pope’s nose to a grindstone turned by English bishops and watched by a horrified cardinal and three friars.35

34The watchcase in question has the foot washing prominently on the reverse of the case, with a scene of the Last Supper covering the face. The coat of arms of Robert Kerr appears on the underside of the face, while on the reverse of the foot washing is a portrait of the king and queen. The message of the king as the servant of his people seems clear. Such imagery, despite its use on papal medals, was evidently not viewed by James as the privilege of the Roman church.36 Since Martin Luther’s famous Passional Christi und Antichristi, the same scene had been juxtaposed in Protestant propaganda with an image of the pope having his feet kissed.37

36Kerr had followed James from Scotland, where he had first come to the king’s attention at the Accession Day tilt in 1607. His rise in royal favour was rapid, being created earl of Somerset in 1613, shortly before his marriage to Frances Howard, former wife of Robert Devereux, third earl of Essex. That year, the king’s Scottish watchmaker, David Ramsay, moved to London and was made clockmaker extraordinary to the king and given the roles of groom of the privy chamber and page of the bedchamber.38 James had turned the bedchamber into a key private space beyond the privy chamber, to which ministers were not admitted and to which access had to be sought through the loyal Scotsmen, including Kerr, who served him. The date of the king’s gift and its symbolism are inextricably linked. The watch must have been made following Kerr’s ennoblement in 1613 but before his sensational downfall in late 1615. Whether James continued the custom of Maundy Thursday foot washing is unknown, but the watch could conceivably have been given to Kerr as a personal token of affection for Maundy Thursday, 27 March 1614, or even on 16 April 1615, before the investigation into Kerr’s role in the murder of Thomas Overbury began in September the same year.

38As king of England, James had not wished to continue the custom of foot washing, nor the custom of healing by royal touch for the tubercular disease known as the King’s Evil. Both practices were undoubtedly thought of as popish by Scottish Presbyterians, but they had been made so popular by Elizabeth that James was advised to keep them.39 Gold “angel” coins that accompanied the touching service were certainly struck in James’s reign and pierced for hanging around the neck of recipients.40 However, Ramsay’s watch is the only extant image of foot washing that appears to have been commissioned by or for the king. That the watchcase bears a portrait of the king and queen, and the arms of Kerr, the king’s favourite, suggests that it had a special meaning for both commissioner and recipient. The sense enshrined in the image of Christ washing the feet of his disciples is that of touch. The engraving itself, with the figure of Jesus worn from handling or from the friction of being worn close to the body, demands to be felt as well as seen. The watch’s oval shape and palm-like dimensions invite the warmth of its recipient’s hand. In the ancient world the washing of another’s feet was an act of service on the part of hosts or their servants, and Jesus’s action is therefore usually interpreted as one of radical humility.

39The central band of decoration encircling the watch clearly indicates that the scenes are taken from chapter 13 of the Gospel of John, where both Peter and “the disciple whom Jesus loved” are focal points. However one views James’s intimacy with his male favourites, the image of Christ as “Master and Lord” washing a disciple’s feet is, undeniably, one of intimacy and profound love. The imagery is powerful precisely because it inverts a hierarchy of power, the master becoming the servant, despite the latter being never “greater than his lord” (John 13:16). The imagery of the watchcase strikes a balance between love and authority, service and kingship.

This is reflected in the king’s letters to Kerr, which David Bergeron has argued reveal a loving relationship that reflected and revealed “intense desire”.41 In the king’s first surviving letter, probably dating from 1615, James declares that Kerr has “deserved more trust and confidence of me than ever man did: in secrecy above all flesh, in feeling and unpartial respect, as well to my honour in every degree as to my profit”. He goes on to speak of the “strange frenzy” and “insolent pride” that have taken hold of his favourite, warning Kerr not to deceive himself or to try his “long-suffering patience”.42 Kerr had apparently woken the king at all hours of the night and been by turns fiery and sullen, refusing to sleep in James’s bedchamber despite the latter’s entreaties. The king goes on to issue a warning: “If ever I find that ye think to retain me by one sparkle of fear, all the violence of my love will in that instant be changed in[to] as violent a hatred”.

41Kerr’s vanity and blindness led him to crave the power his position had led people to believe he possessed, a position that was already straining his abilities.43 The imagery of the watch reflects love but in its shadow is perfidy, for Jesus rose to wash the feet of his disciples after speaking of Judas’s coming betrayal. This exquisite gift feels eerily prophetic in the context of Kerr’s subsequent downfall:

43Verily, verily, I say unto you, The servant is not greater than his lord; neither he that is sent greater than he that sent him … I know whom I have chosen: but that the scripture may be fulfilled, He that eateth bread with me hath lifted up his heel against me. (John 13:16, 18)

Contribution by

-

Joseph James EllisPhD candidateUniversity of York

Royal Gifts and the Politics of Friendship

Seventeenth-century timepieces were prestige items. Although their timekeeping was not always reliable, some had an astonishing array of other horological capabilities. The example featured here is also unusual in the volume of historical information that is packed into its diminutive frame. It is inscribed by the Scot and royal clockmaker David Ramsay, one of the most famous names in early horology and a servant in King James’s Bedchamber. A coat of arms adorning the inside top cover indicates that the watch belonged to the king’s favourite, Robert Kerr, earl of Somerset (fig. 11). The double portrait of James and his consort, Anna of Denmark, suggests that it was a gift from the king. Further symbols help date the object. A coronet atop the coat of arms reveals that it must have been commissioned after Kerr was created earl of Somerset in November 1613. James was unlikely to have given such an exquisite gift after the earl’s downfall in late 1615. This brief period was defined by court scandal, with Somerset at the epicentre. In the space of little more than two years, he went from pre-eminence to prisoner. As such, the watch is a valuable lens through which to explore early modern cultures of gift giving, the politics of favouritism, and material manifestations of power.

In the early modern period, gifts were exchanged between elite individuals to establish or reinforce a friendship. This extended beyond an interpersonal connection to include, as Ruth Grant suggests, “the entire affinity of a noble, along with all the attendant responsibilities and obligations”.44 Recipients acknowledged that by accepting a gift they were expected to advocate on the giver’s behalf. Unlike today, this form of exchange was not considered unscrupulous. Indeed, widely available “wisdom literature” legitimised the notion that gifts inaugurated a bond of social obligation. Seneca the Younger’s classical work, De Beneficiis—translated into English for the first time in 1578 and again in 1614—contained an influential proverb “To give a benefit is a sociable thing … it joyneth that man’s favour, and obligeth this man’s friendship”.45 As the lawyer and politician Sir William Drake later put it, “by gifts and presents a man attains his ends”.46 By the reign of James VI and I, ancient ideas had been distilled into practicalities and rituals that pervaded court life. Even the king was not exempt from the social contract of gift exchange.

44At New Year, courtiers presented the king and queen with gifts in an obligatory act of homage. These usually consisted of gold coin but some chose more imaginative offerings, such as jewellery, horse furniture, items of clothing, or “a box of dry confections”.47 James reciprocated with a quantity of gilt plate based on their position at court in a material affirmation of the hierarchy. He also bestowed vast sums of money throughout the year. David Ramsay, for instance, was well recompensed for his clockmaking skill. In addition to an annual stipend of £250, James granted him the “free gift” of £1,000 in 1614.48 When the king was on progress, civic authorities presented him with gold cups and coins, and he usually reciprocated by renewing the town’s privileges. This ratified bonds of allegiance between crown and country, with a public exposure that could not have been achieved from within the palace walls. Gifts from the king also represented significant political statements. In January 1580, as a boy king in Scotland, James commissioned twenty-five gold rings. The likely recipients were twenty-five gentlemen appointed “to attend the King’s Majesty at all times on his riding and passing to the fields”.49 Wearing the ring was a clear indication of who constituted James’s inner circle and, more significantly, who did not. Thus, a monarch’s authority was reinforced by their participation in wider cultures of gift exchange. There is no written record of James giving Somerset the watch, suggesting that this had occurred in private, but it is likely that he wore it as a pendant around his neck as a conspicuous symbol of royal favour.

47The king’s most intimate companions—his favourites—naturally received more than most. James, who was notoriously profligate, showered them with money, clothes, jewels, and estates. They were granted influential and lucrative positions at court. As Neil Cuddy notes, James created a “private” governmental regime, in which power emanated from the bedchamber. The “director” of this institution was the favourite.50 This was an ideal set-up for a Scottish king accustomed to personal contact in government, yet James’s reliance on favourites did little to bolster his reputation. An increasingly virile news culture reported on the multiple transgressions that came to be associated with Jacobean favouritism—sodomy, popery, and corruption. Moreover, as Curtis Perry argues, contemporary representations treat the “all-powerful, Machiavellian” royal favourite as an “embodied creation of unchecked royal will”.51 They are consistently situated within broader theories of absolute monarchy. Consequently, the meteoric ascent of any individual courtier tended to be followed by an equally spectacular fall. Untold wealth and power attracted resentment. Favourites often died isolated, in disgrace, or by the sword. All three of James’s great favourites followed this well-trodden career path.

50The first was Esmé Stuart, James’s thirty-seven-year-old cousin and later duke of Lennox. On 8 June 1581, according to an inventory, the fourteen-year-old James gave Stuart “ane cheinye of gold contening xxv knottis of perll with twenty fyve buttownes of gold and fiftie dyamantis sett thairin”.52 Like Somerset’s watch, the conspicuous ornament confirmed a political order with Esmé at its apex. Jealous Scottish noblemen formed a powerful faction against him to cut off his access to the king, and he died in exile just two years after receiving the magnificent gift.

52George Villiers, first duke of Buckingham, was the favourite of not one king but two: Charles I was as enamoured with him as his father had been. James’s proclivity for attractive male courtiers is well documented, and Buckingham’s looks and charisma were famously unmatched. Dangerous rumours circulated that the two were engaged in a sexual relationship. The truth behind the gossip is now unrecoverable, but Buckingham’s unstoppable ascent only fuelled speculation. In the decade between 1614 and 1624, he was transformed from a court nobody into the most powerful courtier in the realm. It was impossible, however, for Buckingham to shed the label of “upstart”. A series of ill-advised military campaigns damaged his public image beyond repair, and in 1628 a disgruntled army officer stabbed him to death at the Greyhound Inn in Portsmouth.

The earl of Somerset was Buckingham’s predecessor. His story is one of sex, intrigue, scandal, and murder. After he caught James’s eye in 1607, the two became inseparable. Royal favour shielded Somerset from controversy over his affair with the married Frances Howard, countess of Essex. The pair married in 1613, after the countess secured a dubious and highly public divorce on the grounds of her first husband’s impotence. A depiction of James made the same year shows the monarch wearing a pendant in a style similar to Somerset’s pocket-watch (fig. 12). However, the following year rumours began to circulate that the new earl and countess of Somerset had been complicit in the poisoning of Thomas Overbury, a former friend who had vehemently opposed their marriage. Amid the growing scandal, James publicly maintained his undiminished attachment to Somerset. The gift of the watch in 1614 or early 1615 was perhaps a public statement of solidarity. Behind the scenes, however, the relationship was beginning to sour. James complained of Somerset’s “induced obstinacy” and “strange frenzy”.53 The king’s earlier support for the Howard–Kerr match fuelled dangerous murmurs of royal complicity in the murder. Moreover, James was increasingly distracted by a handsome new rising star, George Villiers, and could not, or would not, protect his former favourite any longer.

53

The watch tells the story of the rise and fall of a royal favourite. It does not appear on the printed inventory of Somerset’s possessions made in November 1615, suggesting that he kept it with him during his subsequent arrest and murder trial, which culminated in a death sentence. The Somerset couple remained prisoners until they were pardoned in 1622 but were never welcomed back at court. The earl’s anxiety during this period may have been manifested on the object itself, for the figure of Jesus has been rubbed raw on both outside covers (fig. 13). The watch also symbolises the political nature of royal “friendship”. A Latin inscription “me facit” (he made me) denotes Ramsay as the watch’s maker but could just as easily describe James’s creation of Somerset. He was the “king’s creature”, rising as a result of royal benevolence only to be abandoned when he became a liability. James certainly had an unwise infatuation for the handsome Scotsman, but he sought loyalty above all. A favourite’s survival depended on his providing it, and extravagant gifts constituted the king’s side of the bargain. It is rare to find such a tangible and personal symbol of this political exchange.

Contribution by

-

Emma SteadCuratorPalace of Holyroodhouse, Royal Collection Trust

Representations of the Royal Family and Familial Imagery

This curious watch contains engraved representations of King James VI and I and Anna of Denmark. The interpretation of these two figures in the interior of the watch case, placed alongside the scenes from chapter 13 of John’s Gospel on the exterior, tells the viewer a great deal about the watch’s depiction of marriage and the royal family. The familial imagery of the watch, which James presented to Robert Kerr, earl of Somerset, around 1615, is interesting given the personal and interpersonal relationship between the gift giver and receiver.

James’s ideological construction of kingship, as represented in portrait types by artists such as John de Critz and Paul van Somer, is evident in the watch. The portrait of James engraved on the watch is of a similar type to that attributed to De Critz in the collection of Dulwich Picture Gallery (fig. 14). The king, depicted wearing The Feather hat jewel and the Great George, is immediately identifiable. Another closely comparable portrait is the half-length etching by Simon de Passe from around the same date as the watch, which shows the king in a remarkably similar stance (fig. 15). Again, the king is instantly recognisable, despite none of the trappings of kingship being present on his person. James’s depiction in the watch portrait is clearly derived from these portrait types and not from life.

By contrast, Anna’s likeness in the watch portrait is not as convincing. We recognise her because she is standing beside her husband, but her characteristics are more generic and she wears none of her distinctive jewellery. This portrait type is well known, and the closest comparison is the portrait by Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger at Woburn Abbey (fig. 16). The cartwheel ruff she is typically depicted wearing in portraits was out of fashion by about 1613, and in both the watch portrait and the Gheeraerts her picadil (the support for her broad collar of lace) is arch-shaped, as it is in a surviving example in the Victoria and Albert Museum dated 1600–15.54 The inclusion of this is helpful in dating the watch.

54

Depictions of James and Anna together in a double portrait form are rare, and the watch portrait is an interesting and unique example on a three-dimensional object. Double portraits of the couple are found in contemporary engravings, including those attributed to Jan Wierix, showing the pair side by side,55 and that by Renold Elstrack (fig. 17). Antony Griffiths posits that Elstrack’s engraving of James and Anna was first published around 1613, following their daughter Princess Elizabeth’s marriage.56 If these dates are correct, the production of such prints indicates James’s desire to portray family unity, domestic order, and dynastic continuity, especially following the loss of Prince Henry Frederick in 1612.

55

Might the watch’s emphasis on domestic harmony relate to the marriage of Robert Kerr and Frances Howard in 1613, whom Elstrack also depicted in a double portrait engraving around 1615 (fig. 18)? The match precipitated a court scandal. Kerr’s affair with the already married Howard was well known, and the king went to great lengths to help her achieve a divorce so they could be wed. Perhaps the watch contains a special message, even a warning, about the expectation of commitment and a projection of unity, especially following the king’s blatant meddling on behalf of his male favourite.

Anna, for her part, famously detested Kerr. Their fractured relationship has often been recounted by James’s biographers, who point to an episode in 1611 where the queen had the prominent courtier Thomas Overbury exiled from court and Kerr was forced to apologise after an incident in which she thought they were laughing at her.57 She later petitioned for George Villiers’s appointment to the bedchamber, apparently to reduce Kerr’s sphere of influence. Her appearance in the watch is therefore most interesting. Why would the watch, showy as it is, depict Anna in a private gift from James to his male favourite?

57The inclusion of Anna and her equal representation with her husband in the portrait is curious, given her dislike of Kerr, the recipient. It points to the watch being gifted from James in an official rather than a personal capacity. The king and queen stand in front of the central throne canopy and chair of estate. The parity of their positioning is noticeable, although the king’s position on the left-hand side affords him precedence, as echoed in the supporters of the coat of arms above them where the lion of England (in the dexter position) is given honour over the unicorn of Scotland. These are the king’s coat of arms rendered in miniature. Nowhere else in pictorial form is Anna granted queenly status in front of the throne chair. For example, in the engraving The Triumph of King James and His August Descendants by Willem van de Passe, made three years after the queen’s death, James sits alone on the throne, with Anna to the side (fig. 19).

There is an immediate comparison to be drawn with a painting in the Royal Collection, The Family of Henry VIII (fig. 20). The composition of this painting, in which Henry VIII appears with Jane Seymour, his three children, and members of the court, suggests that the monarch is responsible for looking after them all. Henry’s stance and position in front of the throne canopy, with everyone else around him, makes his pre-eminence clear; this is not the case in the watch engraving of James and Anna.

Anna’s mere presence in the watch portrait, and especially her positioning in front of the throne, signifies to Kerr her God-given status as James’s consort. It reflects her favourite motto, “My greatness comes from on high” (in Italian, “La mia grandezze dal eccelso”), which can be seen in Van Somer’s portrait Anne of Denmark and a Groom in the Royal Collection (fig. 21). This portrait, one of the last Anna commissioned from Van Somer, is the only one of her known to have been displayed at one of her residences during her lifetime; it hung opposite a portrait of William Herbert, third earl of Pembroke, with whom she had allied herself against the Kerr–Howard faction.58

58

Other engravings featuring both James and Anna are typically part of a larger group portrait in an allegorical setting. An interesting contemporary comparison is the portrait by Simon de Passe of James, Anna, and Charles, Prince of Wales (fig. 22). James is again much more recognisable than Anna. The inclusion of Charles here is interesting and probably represents another conscious attempt by the king to portray family unity. In the instance of the watch, familial imagery extends only to the queen consort.

Interestingly, the only other contemporary instance of familial imagery by de Passe is a scene engraved on the base of a table clock, also by Ramsay, now in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum (fig. 23). The scene shows James holding the pope’s nose to a grindstone, while he is watched with approval by his two sons and other notable Protestant European rulers, and with dismay by a cardinal and three friars. Robert Kerr, by marrying into the Howard clan, had become part of the Catholic faction at court and such obvious imagery would have been entirely inappropriate. Anna also displayed Catholic inclinations privately and probably converted secretly around a decade before her husband’s accession to the English throne. This attracted criticism and controversy, particularly when she refused to take Anglican communion during the coronation service at Westminster Abbey.

The presence of the English coat of arms above the depiction of the monarch in the watch promoted James’s presentation of himself as British, and Kerr as a British subject, whose arms are depicted on the inside of the watch, despite James, Kerr, and Ramsay all being Scottish born. These origins had by 1615 been superseded by new titles for James, as king of England, and for Kerr, as earl of Somerset. The royal coat of arms under the throne canopy is James’s alone, not his married arms, and Kerr’s arms likewise do not reflect the Howard union. If the watch was made to celebrate a marriage, as Elstrack’s double portraits were, it did not represent it fully. Alternatively, if it was meant to underline James’s status in both obvious and subliminal ways, it reinforced the message that, however valued his relationship with Kerr was, it would never come at the expense of his ideological construction of kingship. In James’s first speech to the English Parliament, he used metaphors of marriage and biblical imagery to underline his divine right to rule. He asserted, “I am the husband, and all the whole isle is my lawful wife. I am the head and it is my body. I am the Shepherd and it is my flock”, reaffirming hierarchy and his authority over the nation.59 He also quoted from the marriage service in relation to the union of Scotland and England: “What God hath conjoined, then let no man separate”.

59James was always concerned with the projection of his own family unity and domestic order. This extended to his gift of the watch, where Somerset, as the male favourite and recipient, would have been perfectly aware of the truth of their own relationship. The king’s cultivated persona of the father, whereby he compared a monarch’s duty to their subjects as that of a father to his children, as in his written works The Trew Law of Free Monarchies and the Basilikon Doron, come together in the exterior of the watch. Each side has an engraving from John, chapter 13, showing a scene from the Last Supper and one of Jesus washing his disciples’ feet. The dual strokes of duty and humility are thus brought together in this gift from a king to a subject. The suggestion of a canopy over the exterior depiction of the Last Supper recalls the throne canopy raised over James and Anna in the interior. Thus the joint status of the king and queen is retained at the expense of anything else, including the truth of the relationship between James and Kerr. This costly and personal gift from the monarch to his subject embodies a close and even intimate relationship but one that does not raise Kerr to equal status with the king.

Contribution by

-

Brianna GuthrieInstructor, Art HistoryWake Technical Community College

Reproducibility in the Context of Time

This silver watch represents the inherent complexities of time and portraiture. The first is a concept that can be fixed and yet is ever moving, while the latter, at its most basic, stops time to make the absent present. The Ramsay watch features a portrait of King James VI and I and his wife, Anna of Denmark, and relies on repeated imagery to create and solidify likeness and authority (fig. 24). While the particularizing features of the king and queen are what make them recognizable, it is the longstanding symbols of royal authority that contribute to a chain of references built on both the visual language of popular prints and deeply rooted traditions of monarchical images.

The question of whether an object is an original or a copy is complicated by the nature of production. The designs engraved on the watch likely derive from well-known visual models such as print or stock sources, but there is no question of this object as a whole being “original” or, at the very least, “authentic”. In this case, we have a provenance and the object is signed. Moreover, each of the known surviving watches by David Ramsay is unique; though they share certain characteristics, there was a clear attempt to make each one individual. Yet, if we restrict the idea of originality to just the image of James and Anna, the watch obviously is part of popular material culture and royal imagery circulating in Jacobean England and Scotland at the time.

Scholars such as Angela McShane and Stephanie Koscak have demonstrated the breadth of monarchical images that circulated at all levels of society during the Stuart era.60 Portrayals of the royal family, particularly the monarch, were relatively standard but changed according to the medium or purpose of the object. For example, a limited-edition delicate engraving would look very different to a crude mass-market woodcut; in contrast, a profile portrait on a gold coin bears a passing similarity to a carved ivory knife handle (figs. 25 and 26). Regardless of quality or material, they are all objects that bear the likeness of King James.

60

David Ramsay’s watches are highly decorated objects with repeated motifs, designs, and style. The oval shape itself is often repeated across a variety of media, including popular portrait prints, portrait miniatures, and even rings and other jewelry. The object most closely related to the watch is the engraved oval portrait medallion, of which Simon de Passe was commissioned by the king to create a series. While such items were frequently worn as jewelry to communicate favor and loyalty to the king, de Passe’s portraits can also be found on objects such as gaming tokens.61 Portraits printed as book frontispieces, on maps, and as single sheets were also made to fit into oval frames. Simply put, portraits and other depictions of the king were abundant, and a standardized type of his image developed quickly from early on in his reign.

61The engraved portrait on the Ramsay watch is meant to replicate the royal couple’s likeness and their status. Presumably the images of James on watches or other gifted objects were approved by him and illustrate how he wanted to be seen; they both constructed and performed authority. The rather formulaic visual conventions were meant to reiterate the kingly role, just as the performative nature of monarchy repeatedly imbued the physical body of the ruler with authority. The many depictions of James as king relied on a history of visualized authority that was easily recognized, underscoring a deliberate “disruption of chronological time, to collapse temporal distance”.62 The actual body of a monarch would be substituted with each death, but the standardization of iconography meant that they were always recognizable, regardless of the individual. This is exemplified by recycled engraving plates, where only the faces of Elizabeth I and James I were swapped to indicate a change in reign.63 There is a profound irony in the permanence of visualized monarchical authority engraved on an object that counts the passing of time.

62The watch engraving of James and Anna corresponds to much of their public imagery. This image shares many characteristics across a wide array of painted and printed portraiture: James appears with his signature goatee and wears a feathered hat, along with a cape, doublet, and breeches. The medal around his neck is a familiar reference to the Order of the Garter. Anna, for her part, is shown wearing her signature wide farthingale, holding a handkerchief in one hand and a fan in the other. Her face is framed by a wide, open ruff and she appears to be wearing a number of jewels. The same descriptions, with minor variations, could be applied to any number of painted and printed portraits, such as an engraving by Renold Elstrack (fig. 27). The size of the watch presents obvious limitations in portraying accurate physiognomic detail: the pair’s roster of individual facial features is somewhat absent, replaced by a more generalized appearance. The portrait on the Scottish watch functions differently because of the simple fact that it was given as a personal gift of the king. Robert Kerr, earl of Somerset, knew James well, and the appearance of the royal couple on his watch is enough to function as a symbolic reminder of the king’s largesse and power, regardless of their facial likenesses.

How often would Kerr see the image of James and Anna? For all its symbolism, the image is not shown when the object is used to monitor the time; rather, the portrait of the king and queen would be seen only when winding the mechanism. When using the watch for its intended purpose, Kerr would instead see his own recently updated coat of arms above the watch face, a reminder perhaps of the favor bestowed on him that is better reinforced by the symbol of the monarch’s largesse rather than by an image of the king himself. And what better symbol of the fleeting nature of royal patronage than the gift of a watch?

The watch engraving is part of a wide array of material and visual culture that creates and perpetuates a monarchical type. Its design elements and images were likely copied from other sources, yet the watch is undoubtedly a unique object. Royalty relies on the repeated use of symbols and specific visuals that remain constant regardless of who occupies the throne; official photographs taken after King Charles III’s coronation more recently only confirm the continuity of such traditions. While the portrait of James and Anna freezes them in stasis, the use of the same royal symbols (throne and canopy of state, crowns and scepters, and Order of the Garter accessories) continues even today. Time marches on.

Acknowledgements

The editors would like to thank the National Museums of Scotland and Dr Anna Groundwater, (Principal Curator, Renaissance and Early Modern History), for supporting the feature and for granting access to research and to film the watch.

About the author

-

Kate Anderson is Senior Curator, Portraiture (Pre-1700) at the National Galleries of Scotland where she has responsibility for the sixteenth- and seventeenth-century collections. Her research interests focus on the visual and material culture of the early modern period, specialising in portraiture and self-fashioning at the Stuart courts from about 1560 to 1715. In 2025 she curated the exhibition The World of King James VI & I (National Galleries of Scotland, Portrait) and edited the accompanying publication Art & Court of James VI & I (Edinburgh: National Galleries of Scotland, 2025). Her current research focuses on the British baroque artist John Michael Wright.

Footnotes

-

1

Edmond Howes, The Annales, or Generall Chronicle of England, Begun First by Maister John Stow, and After Him Continued and Augmented with Matters Forreyne, and Domestique, Anncient and Moderne, unto the Ende of This Present Yeere 1614 (London: T. Adams, 1615), 878. ↩︎

-

2

In modernised English from Thomas Dekker, The Gull’s Hornbook, ed. R. B. McKerrow (London: Alexander Moring, 1904), 39. ↩︎

-

3

Adrian A. Finch, Valerie J. Finch, and Anthony W. Finch, “David Ramsay, c.1580–1659”, Antiquarian Horology 40, no. 2 (June 2019): 177–99. ↩︎

-

4

“King James Portrait Watch, circa 1618” (JCT0161), Clocktime, https://clocktime.co.uk/artefacts/ramsay-king-james-portrait-watch. For both watches see T. P. Camerer Cuss, The English Watch 1585–1970 (Woodbridge: ACC Art Books, 2008), 34–35. ↩︎

-

5

“Silver Star-Shaped Verge Watch by David Ramsay” (L2015-3086), Science Museum Group, https://collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk/objects/co8557625/silver-star-shaped-verge-watch-by-david-ramsay. ↩︎

-

6

“Elongated Octagonal Gilt-Brass and Silver Cased Verge Watch” (WA1947.191.36), Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, https://collections.ashmolean.org/object/390499. Ramsay was in Paris in 1610, where this was likely made, though he was in London in 1613. Finch et al., “David Ramsay, c.1580–1659”. ↩︎

-

7

Watch (17.190.1550), The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/194141. ↩︎

-

8

Finch et al., “David Ramsay, c.1580–1659”, 190. ↩︎

-

9

This was not even good astrology. The gearing on the watch simply rotates the planetary hours dial at a steady speed, while the astrological planetary hours were of uneven lengths, changing according to the time of year. Day and night were each divided into twelve hours, so daytime planetary hours were much longer in the summer than in the winter. ↩︎

-

10

James VI, Daemonologie, in Forme of a Dialogue (Edinburgh: Robert Walde, 1597), 14. ↩︎

-

11

Finch et al., “David Ramsay, c.1580–1659”. ↩︎

-

12

Adrian A. Finch, Valerie J. Finch, and Anthony W. Finch, “David Ramsay, c.1580–1659”, Antiquarian Horology 40, no. 2 (June 2019): 177–99. ↩︎

-

13

Silvio A. Bedini, “The Mechanical Clock and the Scientific Revolution”, in Klaus Maurice and Otto Mayr, The Clockwork Universe: German Clocks and Automata, 1550–1650 (Washington, DC: Watsons, 1980), 21–22, exhibition catalogue; David Thompson, Clocks (London: British Museum, 2004), 13; Henry C. King, Geared to the Stars: the Evolution of Planetariums, Orreries and Astronomical Clocks (Bristol: University of Toronto Press, 1978), 80. ↩︎

-

14

George Daniels and Cecil Clutton, Watches: A Complete History of the Technical and Decorative Development of the Watch (New York: Bloomsbury, 2022), 88. ↩︎

-

15

I suggest this based on the model provided by another, comparable watch by David Ramsay of around 1618, sold at Sotheby’s on 15 December 2015. “The Celebration Of The English Watch—Part 1 David Ramsay and the First Clockmaker’s Court) / Lot 4”, Sotheby’s, https://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2015/david-ramsay-and-the-first-clockmakers-l15056/lot.4.html. ↩︎

-

16

The number four on clocks is traditionally shown as “IIII” instead of “IV”, for reasons variously attributed to aesthetic preference, Roman superstition, or (wrongly in this case) to a caprice of Louis XIV of France. ↩︎

-

17

Keith Thomas, Religion and the Decline of Magic: Studies in Popular Beliefs in Sixteenth- and Seventeenth-Century England (London: Penguin, 1991 (1971)), 347–62, esp. 336, 341. ↩︎

-

18

Thomas, Religion and the Decline of Magic, 347–62. ↩︎

-

19

James VI, Daemonologie, in Minor Prose Word, ed. James Craigie (Edinburgh: Scottish Text Society, 1982), 9–10 (bk 1, ch. 4), cited in Jane Ridder-Patrick, “Astrology and Supernatural Power in Early Modern Scotland”, in The Supernatural in Early Modern Scotland, ed. Julian Goodare and Martha McGill (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2020), 132. See Thomas, Religion and the Decline of Magic, 344. ↩︎

-

20

Barbara Howard Traister, The Notorious Astrological Physician of London: Works and Days of Simon Forman (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001), 181–90; see also Lauren Kassell, “How to Read Simon Forman’s Casebooks: Medicine, Astrology, and Gender in the Elizabethan London”, Society for the Social History of Medicine 12, no. 1 (1999): 3–4. ↩︎

-

21

Finch et al., “David Ramsay”, 192–93. ↩︎

-

22

William Lilly, History of His Life and Times, from the Year 1602 to 1681 (London: Charles Baldwyn, 1822 (1715)), 79–80; see also Finch et al., “David Ramsay”, 196. ↩︎

-

23

Aubrey’s Brief Lives, ed. Oliver Lawson Dick (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1957), 5. ↩︎

-

24

Anthony Maxey, The Sermon Preached before the King, at Whitehall, on Tuesday the Eight of Ianuarie, 1604 (London, 1605), C2v. ↩︎

-

25

For more, see Christina J. Faraday, “Tudor Time Machines: Clocks, Dials and Watches in English Portraits c.1530–c.1630”, Renaissance Studies 33, no. 2 (April 2019), 239–66, esp. n50. ↩︎

-

26

A jack or jacquemart was an automaton found on clocks, which struck the hours on a bell. ↩︎

-

27

John Norden, The Labyrinth of Mans Life (London, 1614), D2v onwards. ↩︎

-

28

A. Bellany, “Carr [Kerr], Robert, Earl of Somerset (1585/6?–1645)”, in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2008), https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-4754. ↩︎

-

29

See Adrian A. Finch, Valerie J. Finch, and Anthony W. Finch, “David Ramsay, c.1580–1659”, Antiquarian Horology 40, no. 2 (June 2019): 177–99. ↩︎

-

30

See Jeffery R. Hankins, “Papists, Power, and Puritans: Catholic Officeholding and the Rise of the ‘Puritan Faction’ in Early Seventeenth-Century Essex”, Catholic Historical Review 95, no. 4 (2009): 689–717. Another watch with this subject by Isaake Symmes is recorded by Octavius Morgan: see David Thompson, “Octavius Morgan, Horological Collector, Part One: The Early Years”, Antiquarian Horology 27, no. 3 (March 2003): 310n12. ↩︎

-

31

With many thanks to Tom Hockenhull for correspondence about this piece. ↩︎

-

32

Adrian Finch, A Directory of Early Clockmakers and Apprentices, https://adrianfinchblog.wordpress.com/clockmakers/directory-of-early-clockmakers-and-apprentices/. ↩︎

-

33

For Vogtherr see Frank Müller, Heinrich Vogtherr l’Ancien: un artiste entre Renaissance et Réforme (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 1997); for Solis see the illustration to an unidentified edition of a Passional, printed by Valentin Geissler in Nuremberg after 1552. An example can be found in the British Museum (1874,0711.1922): https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/search?keyword=1874%2C0711.1922. ↩︎

-

34

W. B. Patterson, King James VI and I and the Reunion of Christendom (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 94. ↩︎

-

35

Helen Pierce has convincingly suggested a date of circa 1614 for the clock. Helen Pierce, “The Pope and the Grindstone: A Jacobean Satirical Print”, Print Quarterly 40, no. 2 (2023): 131–37. ↩︎

-

36

I am indebted to Professor Clare Jackson for conversations about James’s theology and the Scottish context. ↩︎

-

37

With thanks to Harry Spillane for providing me with an image of this. ↩︎

-

38

Finch et al., “David Ramsay”, 183. ↩︎

-

39

Carole Levin, “‘Would I Could Give You Help and Succour’: Elizabeth I and the Politics of Touch”, Albion: A Quarterly Journal Concerned with British Studies 21, no. 2 (1989): 203–4 and n47. ↩︎

-

40

For example, C. F. Noon, Spink Coin Auction, 8 October 2003, lot 293; and https://www.sovr.co.uk/products/james-i-fine-gold-angel-mm-mullet-pierced-for-touching-for-the-kings-evil-unc-fm22833. ↩︎

-

41

David M. Bergeron, King James and Letters of Homoerotic Desire (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1999), 68. ↩︎

-

42

Bergeron, King James and Letters, 80–81. ↩︎

-

43

A point made by Steven R. Spence, “The Elusive Robert Carr: A Construction of a Jacobean Favourite, 1598–1612” (MA thesis, Victoria University of Wellington, 2023), 92. ↩︎

-

44

Ruth Grant, “Friendship, Politics and Religion: George Gordon, Sixth Earl of Huntly and King James VI, 1581–1595”, in James VI and Noble Power in Scotland, 1578–1603, ed. Miles Kerr-Peterson and Steven J. Reid (Abingdon: Routledge, 2017), 57. ↩︎

-

45

Thomas Lodge, The Workes of Lvcius Annaevs Seneca, Both Morral and Natural (London: William Stansby, 1614), 100–1. ↩︎

-

46

Commonplace Book of Extracts, University College London, Ogden MS 7/8, fol. 7. ↩︎

-

47

John Nichols, The Progresses, Processions, and Magnificent Festivities of King James the First, 4 vols (London: J. B. Nichols, 1828), 1:596–97. ↩︎

-

48

Nichols, Progresses, 3:78. ↩︎

-

49

Estait of the King's Household, National Records of Scotland, Edinburgh, E34/35/14. ↩︎

-

50

Neil Cuddy, “The King’s Chambers: The Bedchamber of James I in Administration and Politics, 1603–1625”, PhD diss. (University of Cambridge, 1987), iii. ↩︎

-

51

Curtis Perry, “1603 and the Discourse of Favouritism”, in The Accession of James I: Historical and Cultural Consequences, ed. Glenn Burgess, Rowland Wymer, and Jason Lawrence (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006), 161. ↩︎

-

52

A Collection of Inventories and Other Records of the Royal Wardrobe and Jewelhouse (Edinburgh, 1815), 305–7. ↩︎

-

53

G. P. V. Akrigg, ed., Letters of James VI & I (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992), 335–40. ↩︎

-

54

Picadil (192-1900), Victoria and Albert Museum, https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O110596/picadil-unknown/. ↩︎

-

55

For example, the portrait of James VI and I and Anna of Denmark in the British Museum (O,8.168), https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_O-8-168. ↩︎

-

56

Antony Griffths, The Print in Stuart Britain, 1603–1689 (London: British Museum Press, 1998), exhibition catalogue: British Museum, London. ↩︎

-

57

Historical Manuscripts Commission, Report on the Manuscripts of the Marquess of Downshire, Preserved at Easthampstead Park, Berkshire, vol. 3, Papers of William Trumbull the Elder, 1611–1612, ed. A. B. Hinds and E. K. Purnell (London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1938), 83. ↩︎

-

58

Jemma Field, “Anna of Denmark: A Late Portrait by Paul van Somer”, British Art Journal 18, no. 2 (2017): 50–55. ↩︎

-

59

The Speech of King James the I. to Both Houses of Parliament upon His Accession to, and the Happy Union of Both the Crowns of England and Scotland Regally Pronounced, and Expressed by Him to Them, die Jovis 22th. Martii 1603 (London: Richard Baldwin, 1689), https://name.umdl.umich.edu/A46455.0001.001. ↩︎

-

60

Angela McShane, “Subjects and Objects: Material Expressions of Love and Loyalty in Seventeenth-Century England”, Journal of British Studies 48, no. 4 (2009): 871–86, DOI:10.1086/603618; Stephanie E. Koscak, Monarchy, Print Culture, and Reverence in Early Modern England (London: Routledge, 2020). ↩︎

-

61

One such token was applied to a patch box, now in the Royal Collection, RCIN 22002, https://www.rct.uk/collection/search#/1/collection/22002/patch-box. ↩︎

-

62

Alexander Nagel and Christopher S. Wood, Anachronic Renaissance (New York: Zone Books, 2010), 32. ↩︎

-

63

James I, 1610, Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 601393, https://www.rct.uk/collection/search#/1/collection/601393/james-i. ↩︎

Imprint

| Author | |

|---|---|

| Date | 18 December 2025 |

| Category | One Object |

| Review status | Peer Reviewed (Double Blind) |

| License | Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) |

| Downloads | PDF format |

| Article DOI | https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-29/oneobject |

| Cite as | Anderson, Kate. “‘A Gift with Strings Attached’: Deciphering a Jacobean Watch.” In British Art Studies: Reframing King James VI and I (Edited by Kate Anderson, Jemma Field, and Catriona Murray.). London and New Haven: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art and Yale Center for British Art, 2025. https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-29/oneobject. |