“May They Associate”

“May They Associate”: Decoding an Illuminated Book Designed for King James VI in Paris by Agents of Mary, Queen of Scots

By Alexandra Plane

Abstract

The article presents the first full study of a significant illuminated book prepared as a gift for King James VI around 1581–82. The article uses analysis of the book’s complex emblems and texts to argue that its decoration was designed and commissioned by agents of his mother, Mary, Queen of Scots, in Paris. Examination of its illuminated title page reveals the Scotsman John Gordon’s role in adapting Mary’s most famous emblem into a new design that promoted her plan for joint rule, or “Association”, with her son. The artistic and financial investment in this deluxe book shows that the teenage King James VI was expected to be capable of skilled engagement with visual media in an international courtly context.

Introduction

This article focuses on one of the many hundreds of surviving books acquired or intended for the Scottish and English libraries of King James VI and I. Many are arrestingly beautiful material objects. Yet, even among these riches, this book stands out for its overlooked artistic and political significance. A thorough analysis reveals its importance for the study of title pages as “outstanding witnesses for the history of the early modern cosmos of images”.1 The book repeatedly surfaced in the collections of some of the greatest French bibliophiles of the nineteenth century: Ambroise Firmin-Didot; Charles-Alexandre, third marquis de Ganay; and Eugène and Auguste Dutuit.2 In 2016 it featured as the final item in an exhibition at the Musée des Antiquités in Rouen, Trésors enluminés de Normandie: Une (re)découverte.3 Despite these appearances and its residence since 1902 in the public collection of the Petit Palais, Paris, the book has never been addressed in the scholarship on its intended recipient, King James VI and I.

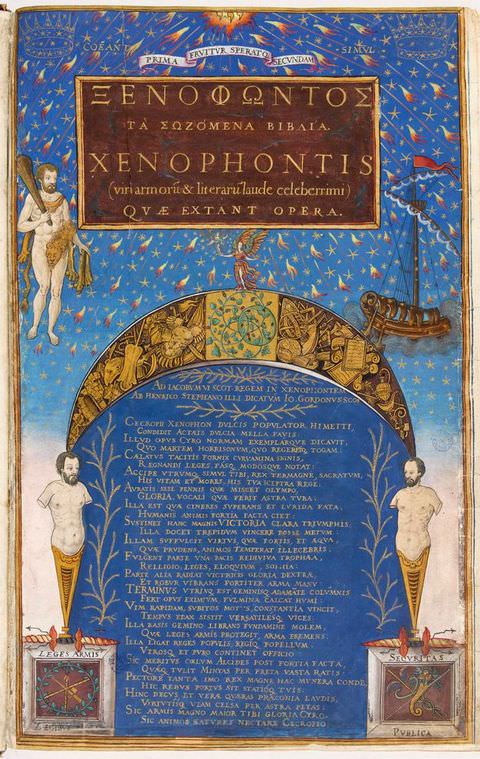

1The book in question is a copy of Henri Estienne’s second edition of the collected works of the ancient Greek author Xenophon, printed in 1581.4 I argue that, far from being a straightforward presentation copy from its printer, as is sometimes believed, it was commissioned and designed for James in Paris around 1581–82 by agents of his mother, Mary, Queen of Scots. Analysis of the illuminated texts and emblems on its complex title page shows that Mary’s most famous emblem was reworked into a new design with the aim of promoting her plan for joint rule, or “Association”, with her son. I discuss the scheme and execution of the volume in terms of meaning, design, artistry, and cost, bringing to light the role of the little-known John Gordon, a Scotsman in Paris of dubious morals but emblematic expertise. These findings provide new evidence not only for the rich and interconnected visual culture of Jacobean Scotland and France, but also for the teenage King James’s own aptitude and interest in the interpretation of text integrated with visual imagery.

4A Dazzling Illuminated Title Page

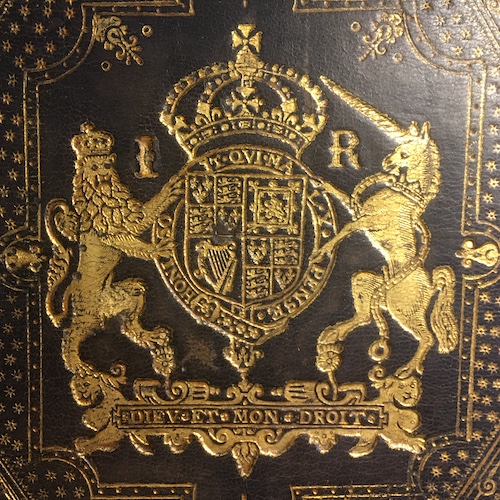

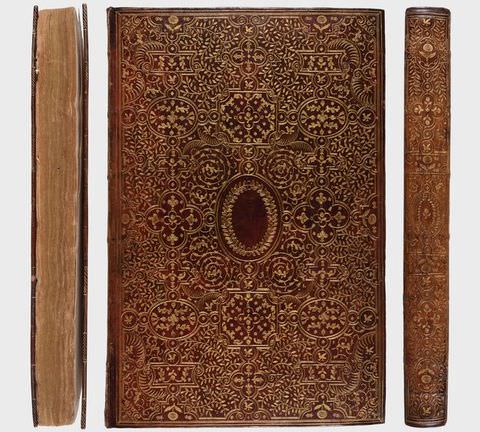

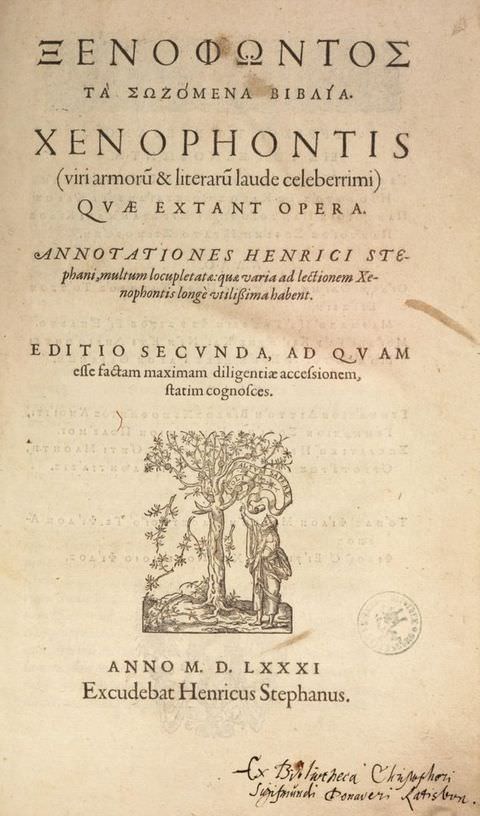

The book’s editor-printer Henri Estienne was the most famous humanist scholar-printer of his era. By the time of its publication in 1581, he was in dire straits financially because of the enormous cost of printing two landmark works of scholarship. These were his five-volume Greek thesaurus, Thesaurus Graecae linguae (1572); and his edition of Plato’s collected works (1578), the second volume of which he had dedicated to King James VI. Estienne’s financial precarity may have also prompted him to dedicate his new edition of Xenophon to James. In 1579 James had rewarded the Protestant composer Jean Servin with 100 gold crowns after Servin had dedicated his printed psalm settings to him, commissioned a luxuriously bound set, and personally transported them to Scotland for presentation.5 Estienne had probably heard of James’s generosity to Servin. They both worked on the psalm paraphrases of George Buchanan, James’s tutor, and were also both residents of Geneva, where Estienne’s new edition of Xenophon’s works was printed.6 It has usually been assumed from its ornate decoration that the copy of the book analysed here was the dedication copy, sent to James by Estienne.7 Two pieces of evidence raise questions about this assumption. The first is the copy’s distinctively Parisian “fanfare” binding, discussed in more detail below (fig. 1). High-profile presentation copies bound in Geneva were generally bound in a different style by workshops such as the Geneva Kings’ Bindery, which was chosen by Jean Servin for his presentation set for King James (fig. 2).8 The second piece of evidence reveals itself when we open the book to find not Estienne’s printed title page (fig. 3) but richly illuminated images surrounding a poem addressed to James by a “John Gordon, Scotsman” (fig. 4). Why would Henri Estienne, a capable poet, send a copy of his Xenophon to be bound in Paris and order his own name and printer’s device to be replaced with a poem written by someone else? His printer’s device depicting an olive tree had been passed down the family as a powerful commercial and cultural symbol of the Estienne printing dynasty. Hélène Cazes has noted that “la sobriété de la mise en page, sans cadre ni couleur” (the sobriety of the page layout, with neither border nor colour) was an important visual signifier of an Estienne edition.9 This densely illuminated title page could not therefore be more un-Estienne. The reason for the incongruity is probably that the book was not a straightforward dedication copy from Estienne but a complex political gift designed by Gordon.

5

A closer look reveals that the printed title page is present beneath the decoration, and that a blank sheet of paper has been pasted over it as a base for the illumination (fig. 5). The only element that has been preserved from the printed page is the work’s title, but even its printed letters have been painted over in gold on a veined red ground imitating a marble tablet. The rest of the printed page has been replaced by a complex design of emblems and mottoes. Half the page is now taken up by Gordon’s thirty-six-line neo-Latin poem written in gold on an azure ground, within a triumphal arch. To the left is Hercules with his characteristic Nemean lion skin and club, while to the right is another symbol of ancient Greek heroism: the Argo, the ship that carried Jason and the Argonauts. The content is remarkably beautiful but relatively unsurprising so far, its classical imagery well suited to an edition of Xenophon being sent to a young, elite male recipient. However, at the top of the page is a rather more unusual set of images and mottoes. In the top corners of the page are two crowns outlined in gold and composed of golden stars, and between them are two Latin mottoes: “Coeant simul” (May they join together at the same time) and “Prima fruitur speratq[ue] secundam” (He/she enjoys the first and hopes for the second).

The identity and personal contacts of the poem’s author clarify the meaning of these mottoes. The poem’s heading reads “Ad Iacobum VI Scot Regem in Xenophontem ab Henrico Stephano illi dicatum Io. Gordonus Scot” (John Gordon, Scotsman, to James VI King of Scotland in the Xenophon dedicated to him by Henry Stephanus [i.e., Henri Estienne]). Gordon was the grandson of an illegitimate daughter of King James IV of Scotland and therefore a blood relation of both Mary, Queen of Scots, and King James VI.10 He was also an extremely slippery character. A report commissioned by William Cecil concluded of his spying and double-dealing that “his custom was to dine with the one and sup with the other, making his profit of both, and making both privy of the other’s counsels”.11 Gordon used his classical learning to curry royal favour by writing panegyrics. He wrote in Latin in support of Mary, which prompted her to ask the archbishop of Glasgow James Beaton, her ambassador in France, to advance Gordon his yearly pension in 1571.12 Mary’s financial support enabled him to study in Paris and serve as gentleman-in-waiting to Charles IX, Henri III, and Henri IV. He also spent time in her household in England.13

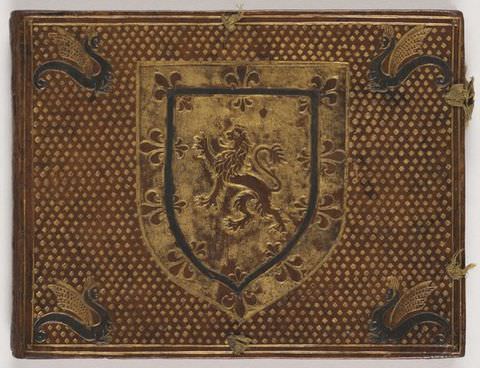

10In France, Gordon served as a court expert on emblems and classical myths. The printed account of Henri III’s 1581 Balet comique de la Royne, a significant performance, ended with Gordon’s interpretation of its Circe mythography.14 This publication has been regarded as a significant influence on both Ben Jonson, whose copy survives, and Inigo Jones, who lifted text directly from Gordon for the masque Tempe Restored (1632).15 Gordon was also the person who recommended to Henri III an emblem of three crowns accompanied by the motto “Manet ultima caelo” (The last remains in heaven).16 Michael Bath and Nuccio Ordine have traced the evolution across Europe of this emblem, which was invented by or for Henri’s sister-in-law, the eighteen-year-old Mary, Queen of Scots, and which first appeared on a jeton minted for her in 1560 (fig. 6).17 She later embroidered it into the hangings of her bed of state, which was sent to James in 1587.18 The upper portion of the title page of James’s Xenophon must be another interpolation of this emblem and its accompanying mottoes. Mary’s 1560 jeton shows two of the three crowns as real crowns, while the third is made of stars. The motto on the jeton reads “Aliamque moratur” (And she awaits another). As mentioned earlier, the Xenophon title page depicts two star crowns with the motto “Prima fruitur speratq[ue] secundam” (He/she enjoys the first and hopes for the second). In both cases, the implied object of expectation, enjoyment, or hope is a crown. Bath has shown that the ambiguity is deliberate: it is what gave the emblem “the extraordinary political and rhetorical power which it had in the sixteenth century”.19 For Mary, the star crown could represent her claim to the throne of England and/or, less controversially, the expected reward for her piety after death.

14

What, then, do the two star crowns and mottoes represent in the book intended for her son? In 1581, the year in which the book was printed, Mary was planning what is known as the Association, a scheme for joint rule by her and James as co-monarchs. The Catholic monarchs of Europe would not recognise James as king without Mary’s permission. While in English captivity, she used this as leverage in her attempts to persuade her son to agree to her plan. The Association has been “typically overlooked or misunderstood: indeed, there is no proper scholarly account” of it.20 It has recently been addressed in the context of the English succession by Susan Doran and Paulina Kewes, while the decryption of Association-related letters from Mary has provided new evidence.21 One of these letters, dated 20 October 1581, revealed Mary’s anxiety about the safe delivery of a crucial Association-related missive to James Beaton in Paris.22 The cryptographers did not identify the letter she mentioned.23 It can now not only be identified but also connected to the design of the Xenophon title page. The letter in question must have been a letter of 28 August 1581, Mary’s commission to Beaton regarding the Association.24 Fearing it lost, she sent him another letter on 28 October, explaining the Association’s constitutional innovations and practical arrangements in great detail over sixteen pages. She charged Beaton with negotiating her son’s agreement to her plan and even described her planned Association coinage: “there shall be on one side engraved the portraits of the faces of their majesties … with this inscription ‘Securitas publica’, or other such device which will be found fitly to denote and signify the said union and association”.25 “Securitas publica” is exactly the motto used on the Xenophon title page, on one of the pedestals below the poem. This Association motto also provides the context for the second motto between the two star crowns: “Coeant simul” (May they join together at the same time; or, indeed, May they associate). The two star crowns, then, symbolise the hoped-for joint rule: a new transformation of Mary’s internationally famed emblem. Mary had stipulated in her letter to Beaton that James would need to be re-crowned, either actually or symbolically.26

20John Gordon’s Poem: A Guide to the Visual Content of the Page

With this context in mind, we are now better equipped to interpret Gordon’s poem on the title page. In full, with my interlinear English translation, it reads:

27Ad Iacobum VI Scot. Regem in Xenophontem

ab Henrico Stephano illi dicatum Io. Gordonus Scot.

John Gordon, Scotsman, to James VI King of Scotland

in the Xenophon dedicated to him by Henry Stephanus27

28Cecropii Xenophon dulcis populator Himetti,

Xenophon was a consumer of the Hymettian sweetness of Cecrops,28

condidit actaeis dulcia mella favis:

he preserved sweet honey from Attic honeycombs:

illud opus Cyro normam exemplarque dicavit,

he dedicated that work to Cyrus as a standard and example

quo martem horrisonum quo regeretque togam:

of how to direct cacophonous war and wear the toga [of peace]:

caelatus tacitis fornix curvamina signis,

the arch carved on its vaulting with motionless symbols

regnandi leges fásque modósque notat:

signifies the laws, religious dictates, and methods of ruling:

accipe utrumque simul tibi, rex termagne, sacratum,

receive both of these dedications29 together, great king,30

his vitam et mores, his tua sceptra rege:

with these rule your life and customs, with these rule your kingdom:31

auratis sese pennis quae miscet Olympo,

it is Glory who stirs up the heavens with her golden wings,

Gloria, vocali quae ferit astra tuba:

who reaches the stars with her resounding trumpet:

illa est quae cineres superans et lurida fata,

it is she who, overcoming ashes32 and ghastly fortunes,

humanis animis fortia facta ciet:

sets in motion bold deeds through human spirits:

sustinet hanc magnis Victoria clara triumphis,

shining Victory sustains her through great triumphs,

illa docet trepidum vincere posse metum:

she teaches the fearful that it is possible to conquer fear:

illam suffulcit Virtus, quae fortis, et aequa,

Virtue holds her up, who is brave, and just,

quae prudens, animos temperat illecebris:

who is prudent, who holds minds back from temptations:

fulgent parte una pacis rediviva trophaea,

the renewed trophies of peace gleam on one side,

relligio, leges, eloquium, sophia:

religion, laws, speech, wisdom:

parte alia radiat victricis gloria dextrae,

on the other side shines the glory of the victorious right hand,

et robur vibrans fortiter arma manu:

and strength boldly brandishing weapons:

terminus utrinque est geminisque adama[n]te columnis

the terminal figure on either side is made of adamant in twin columns,

fert opus eximium, fulmina calcat humi:

it holds an extraordinary load, it bears down the crushing weight of a thunderbolt on the ground:

vim rapidam, subitos motus constantia vincit,

constancy overcomes swift force and sudden tumults,

tempus edax sistit versatilésque vices:

it halts devouring time and reversals of fortune:

illa basis gemino librans fundamine molem,

that pedestal balancing the weight on a twin foundation,

quae leges armis protegit, arma premens:

it protects laws with weapons, holding weapons:

illa ligat reges populis, regíque popellum,

it binds kings to peoples, and the masses to the king,

utrosque et puro continet officio:

it holds them together with pure duty:

sic meritus coelum Alcides post fortia facta,

thus Alcides33 was worthy of heaven after brave deeds,

quaeque tulit Minyas per freta vasta ratis:

and the ship which carried the Minyans34 through the immense seas:

pectore tanta imo rex magne haec munera conde,

treasure such valuable gifts as these deep in your heart, great king,

hic rebus portus sit statioque tuis:

may this be a haven and resting place from your affairs:

hinc decus et verae quaeras praeconia laudis,

from here may you seek honour and the publishing of true praise,

virtutisque viam celsa per astra petas:

may you seek the way of virtue through the lofty stars:

sic armis magno maior tibi gloria Cyro,

thus in arms there will be greater glory for you than for mighty Cyrus,

sic animos satures nectare Cecropio.

thus may you fill hearts with the nectar of Cecrops.

The poem’s framing device refers to Xenophon’s role as the biographer of Cyrus the Great of Persia. Gordon used it to signal his classical learning and flatter James’s own, assuming that he would understand the reference to the “sweetness of Hymmetos”, a mountain near Athens.35 The sources for this reference were the works of the ancient Graeco-Roman writers Pliny, Pausanias, and Strabo, all of which were familiar to those with a Renaissance humanist education. Gordon could be confident that the young king had read these works during his intensely academic upbringing with his tutors, George Buchanan and Peter Young. Gordon’s performative erudition may have influenced James’s decision in 1603 to recall him from France to become dean of Salisbury and to praise him “with a speciall Encomion, that hee was a man well travelled in the Auncients”.36 Gordon correctly judged that James would have read Xenophon’s Cyropaedia, one of the most influential works in the speculum principis, or “mirror for princes”, genre.37 James’s childhood copy of the 1569 Basel edition of Xenophon survives,38 as does Young’s record of a remark made by the young James when reading Xenophon’s Cyropaedia.39 By describing Cyrus’s exemplarity as a leader in war and peacetime, Gordon set up a link to the “carved arch” with its corresponding two sides. The trophies on the right represent peace, including an armillary sphere, a globe, music books, and musical instruments. Those on the left represent martial victory. They include weaponry, armour, and what appears to be the head of a tapir. Tapirs had been described by several European authors by the early 1580s. André Thevet had mentioned them in his Les singularitéz de la France antarctique.40 James had owned a copy of this book since childhood, and Mary, Queen of Scots, reproduced images from another copy of it in her embroidery, including a toucan.41 There are no securely identified European visual representations of tapirs from before 1594.42 If this is a tapir, it may symbolise, given the military context, the perceived glories of colonial expeditions, including those that had enabled Frenchmen such as Thevet to encounter tapirs in South America. The poem also tells us that the two figures perched atop the arch are the personifications of Glory, with trumpet, standing on Virtue, who is holding a gold crown rather than her customary laurel wreath.

35It is noteworthy that although the poem explains every visual element below the title of the printed work, it does not address any of the imagery or mottoes at the top of the page connected to Mary’s famous emblem. A closer reading of the poem, however, suggests that Gordon directs James’s attention towards them in a more nuanced way. He interprets the surrounding images as portraying the benefits that Mary is offering James through the Association. Twin figures share the burdens of war and peace, providing a constancy that is capable of overcoming attack or unrest. Their two pedestals, one bearing the motto specified by Mary as her chosen wording to “denote and signify” the Association, emphasise how judicial and military strength together promote national stability and popular loyalty to rulers. Accompanying the motto are a crossed caduceus and a cornucopia, jointly symbolising peace and public felicity. The message is strengthened by the other pedestal, with its image of a crossed sword, rule, and fasces, signifiers of military power, rectitude, and public order and concord respectively.43 The motto on this pedestal is “Leges armis, legibus arma” (Laws for weapons, weapons for laws).

43By contrast, Hercules and the Argo may seem like unremarkable classical images rather than part of this political subtext. However, consider their position on the page: they are depicted in the sky to emphasise that they both became constellations; the Argo even has a covering of stars to show that it is the Argo Navis constellation.44 Gordon concludes the poem by urging James to gain even greater glory than Cyrus by “seek[ing] the way of virtue through the lofty stars”. The Association emblems and mottos are quite literally written in the stars of this page, floating loftily in the heavens above Hercules and the Argo; the two crowns are made from stars. The “way of virtue” lies, then, in agreement to the Association, which will help James to become, like Hercules and the Argo, a heroic figure “worthy of heaven”.

44The Making of the Book: Design, Illumination, Binding

This title page can therefore be interpreted as a work of symbolic propaganda designed to promote the Association to James. Beaton, who we know was acquainted with Gordon and facilitated his payments from Mary, may have delegated the production of the book to him. Gordon was ideally equipped for the task, for he had experience of writing royal panegyrics in Latin, expertise with royal emblems, and even knowledge of Parisian bookbinders. Henry Killigrew reported in 1573 that Gordon had “deceived a bookbinder in Paris of a good piece of money”.45 The design is most likely his, given its novel interpolation of Mary’s emblem and its integration with the textual content of his poem. His use of the adjective “termagne” to address James in the poem may also be a clue to one of his sources of inspiration. John Elder, tutor to Lord Darnley, had published in 1555 The Copie of a Letter Sent in to Scotlande, his account of Philip II of Spain’s arrival in England, where he recorded that the spectacle featured verses including the words “ter magne Philippe”, “wrytten in a field blue, whiche Heroldes call azure, with faire Romaine letters of siluer”.46 It is possible that Gordon, an interpreter of royal pageants, used a copy of Elder’s work as an inspiration for his title page, with its address to James as “rex termagne”, written on an azure field in fair Roman capital letters of gold.

45Illustrated title pages are attracting increasing scholarly attention. In Gateways to the Book: Frontispieces and Title Pages in Early Modern Europe, Gitta Bertram, Nils Büttner, and Claus Zittel argue that they form “the via regia leading into early modern visual culture: they provide emblematic models and ideograms; they are the key to the worlds of cognition and imagination; they show patterns of perception, ordering and reasoning; they shape the collective memory”.47 The design of the title page in James’s Xenophon shares some elements with the genre of “architectural” title pages that was popular in the late sixteenth century.48 Unlike these others, however, it is not the result of homogeneous mass production via printing. Its aim is not to “shape the collective memory” but to shape the mind of one individual, King James VI. Its relationship to the text it precedes is also fundamentally different to that of most title pages. Following Gérard Genette’s approach to interpreting the textual structures of books, title pages are generally treated as “paratexts” that serve as thresholds to the text proper.49 However, Gordon’s title page, the only section of the book that is coloured and illuminated, presents itself as the only part that matters. Rather than encouraging its reader to pass through the archway into Estienne’s text, it persuades them to stop, entranced, and study not only Gordon’s poem but also his emblematic design. Estienne’s printed dedication to James, lauding him as a Protestant champion, literally pales in comparison. Recent research on title pages has been grounded in the assumption that “all title pages and frontispieces have in common that they introduce a codex”.50 Gordon’s extraordinary title page does not play an introductory or supporting role but reverses this dynamic and makes the codex a support for its illumination.

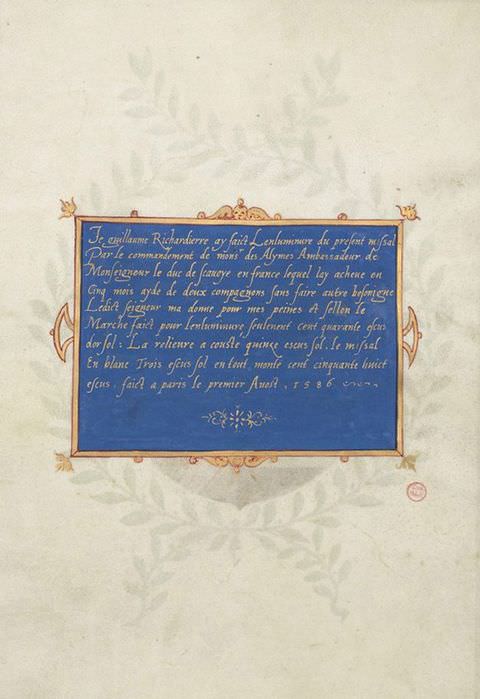

47The political content of this page enables us to pinpoint its decoration with unusual precision. We are looking at the output of a professional miniaturist working in Paris, probably in 1581–82. Most Renaissance artists of this kind are unidentifiable today, but we do know the name of one important miniaturist working on high-level commissions in Paris in the 1580s.51 Guillaume Richardière was employed in 1586 to illuminate a printed missal for René de Lucinge, seigneur des Alymes, and in the following year to illuminate another missal (known from an itemised bill) and the gospel book of the Ordre du Saint-Esprit, a chivalric order founded by Henri III.52 The first book, which has survived, opens with writing in gold on an azure ground: “I, Guillaume Richardierre, illuminated the present missal … I completed it in five months, helped by two companions, without doing any other work”. He continues to say that the costs were “for the illumination only, one hundred and forty écus d’or soleil; the binding cost fifteen écus soleil; the blank missal, three écus soleil” (fig. 7).53 One miniature survives from the book he illuminated for the Ordre du Saint-Esprit.54 Its border of golden stars trailing orange and red tails on an azure ground is strikingly similar to the background of the upper portion of the Xenophon title page (fig. 8). It is possible that Richardière was employed to realise Gordon’s vision, but closer study, possibly with scientific analysis of pigments, will be necessary to prove this. Regardless, it is clear from the nuance and detail of the Xenophon title page—particularly the fine shading and hatching on the anatomy—that its illuminator was extremely skilled.

51

Also anonymous is the other expert artist who worked on the book: its binder. The book was bound in the fanfare binding style that was a specialism of high-end binders in Paris. It can be difficult to appreciate today quite how much skill was involved in creating a binding of this kind. To produce a fanfare design, binders used many individual metal tools to cover the book’s surface in complex geometric designs of interlocking shapes. They then surrounded these with additional gilt tooling of leafy branches.55 Each design is entirely unique. In his study of fanfare bindings, Geoffrey Hobson has observed that, on average, only two per year have survived from their main period of production from around 1570 to 1588.56 Fanfare bindings were among the most difficult designs to execute and would have been beyond the capabilities of most binders, even in Paris.57 They were produced in limited numbers, at great cost, for an exclusive clientele. Many owners of fanfare bindings were members of the French royal family, particularly Catherine de’ Medici and Henri III.58 James VI is one of only four foreign monarchs known to have possessed a fanfare binding and the only one known to have owned multiple fanfare bindings.59

55Very little archival evidence survives for sixteenth-century binderies, which generally did not sign their work. The binding on James’s Xenophon, like many other fanfare bindings, has been attributed to Nicolas and Clovis Eve simply on the basis that they were known to be working at the top end of the market in Paris at the time.60 Rigorous analysis of bindings, however, requires closer examination of the individual tools used across different books to identify shared ones, which may indicate an origin in the same workshop. Hobson followed French scholars in sounding a note of caution on attributions to the Eves.61 Using a systematic analysis of tools on fanfare bindings, he was able to identify twenty-three from the same workshop. The presence of Henri III’s arms on some of them showed that they were the work of a royal binder.62 Among the twenty-three is James’s Xenophon, with its distinctive tool of a tiny walking bird linking it to this group (fig. 9).63 Like the illuminator, the binder employed to work on James’s Xenophon was clearly among the best to be found.

60

We can deduce, then, that a significant amount of money was spent on creating this deluxe personalised book for James. However, its commissioners were able to limit their expenditure because of the specific political focus of its decoration; they did not pay for illumination beyond the title page. It seems unlikely that John Gordon, who was known as a constant borrower of money, would have been able or willing to pay for the book, its binding, and its decoration. It is more likely that Beaton provided the financial backing as part of his commission from Mary to advocate for the Association on her behalf. Enough money was spent on the book to attract James’s attention with its spectacular binding and dazzle him with its title page, but nothing further. Although the rest of the book functioned as a carrier for its extraordinary title page, its contents were likely also a deliberate choice. The 1581 Xenophon was probably selected precisely because it had been dedicated to James by Henri Estienne, an international leader of Protestant scholarship. He was a friend and printer to many of the learned Scots who had contributed to James’s upbringing. These included Henry Scrimgeour, who had been the first choice to tutor the young James.64 Estienne praised Scrimgeour in the dedication as the scholar whose research had laid the foundations for his editions of Xenophon.65 Estienne also corresponded and worked with George Buchanan and Peter Young, the two scholars appointed as James’s tutors; Young was also Scrimgeour’s nephew and keeper of James’s library. The 1581 Xenophon, printed by Estienne and dedicated by him to James, was therefore ideally suited to act as a Protestant Trojan horse for pro-Catholic propaganda.

64The care that went into the book’s production tells us a great deal about what people expected of the young king’s ability to interpret complex visual media. Why invest so much time, money, and effort in an object if James would not be able to understand its message? The design of the title page shows that James was expected to be fully conversant not only with pre-existing political emblems, but also with how they could be reworked and redeployed in new contexts. James’s librarian recorded a number of emblem books in his childhood library by the authors Andrea Alciato (in Latin), Claude Paradin (in French and Latin), Paolo Giovio (a French translation), and Guillaume de la Perrière (in French).66 The design of the Xenophon title page shows that, as he approached adulthood, James was expected to have absorbed their contents. The teenage James was not just an able student but also a teacher in the art of emblems. In 1584 the Scottish courtier and poet William Fowler wrote in a note to James that “whils I was teaching your maiestie the art of me[m]orye yow instructed me in poesie and imprese for so was yours, sic docens discam” (while I was teaching your majesty the art of memory, you instructed me in poetry and emblems for so was yours, thus may I learn while teaching).67 As well as attesting to James’s knowledge and interest in emblems, the quotation is noteworthy in associating his understanding of “imprese” (emblems) with “poesie” (poetry).

66James’s own use of an integrated approach to poetry and visual imagery is apparent in his printed works, particularly his 1584 double acrostic poem in the shape of a funeral urn, mourning the death of his cousin Esmé Stewart.68 He also drew on his classical education for displays and gifts, including the heroic figures of Hercules and the Argo that feature on the Xenophon title page. In 1594 he collaborated with William Fowler to design the baptism of his son Prince Henry Frederick at Stirling. The most notable feature was the huge model ship, which contributed to James’s self-presentation as a “newe Jason”, to use Fowler’s words.69 In 1590, when James was in Denmark for his honeymoon, he gave the University of Copenhagen a silver gilt cup as a gift of thanks for his visit there. Until now, scholars of King James have been unsure of the cup’s design, survival status, or condition.70 While it was partially melted during the British Navy’s bombardment of Copenhagen in 1807, the cup and its lid were rescued from the wreckage and eventually became one of the earliest items in the collection of the National Museum of Denmark.71 Standing atop the lid is the figure of Hercules, depicted holding a club and lion skin just as on the Xenophon title page (fig. 10). James clearly recognised that classical images and emblems provided a shared visual language when he was planning events and gifts aimed at an international audience.

68

Potential Couriers of the Book from Paris to Scotland

It is difficult to say whether the copy of Xenophon’s works carefully decorated with classical imagery, Gordon’s poem, and his emblem designs ever reached James. His librarian, Peter Young, stopped recording new additions to his library around 1580.72 Documented sightings of this copy can be traced back to 1741, when the bibliographer Michel Maittaire printed the text of the poem, which he had “happened to read”, deep in the appendix of the final volume in his Annales typographici ab anno MDXXXVI.73 Maittaire was French but resided in England from the late seventeenth century, so it is not clear where he saw the book. Given how much effort had gone into producing it, Gordon and his associates must have tried their best to deliver it to James. In May 1583 Francis Walsingham heard from the English ambassador in Paris that John Gordon would be employed as the French king’s “agent about ye Scot kynge”.74 Gordon applied to Walsingham for a passport in December that year, explaining that he planned a three-month trip to Scotland via England because he had been away for eighteen years and was eager to meet James.75 Negotiations for the Association largely took place between 1581 and the summer of 1583, so the plan may have been to secrete the book in an earlier shipment or embassy from France. Such transportations of goods were used as opportunities for Association-related spying and the transmission of documents. A 1581 shipment of sumptuous French apparel for James and Esmé Stewart, transported by one of Mary’s close associates, fell under the suspicion of the English ambassador to France.76 He wrote that if a boat were to intercept “George Douglas and his merchandise it would profit somebody. There will be letters worth the sight”.77 These suspicions soon boiled over in the Ruthven Raid, when James was held hostage by some of his pro-English and anti-Mary nobles. They were reported to have tortured Douglas, who confessed that he had addressed James “in this matter of Association”.78

72The presence of Mary’s chosen Association motto in the book, communicated to Beaton after Douglas’s departure from France, suggests that it was transported in a later shipment. It may have accompanied the gift of horses sent to James by the duc de Guise in May 1582; a spy reported that the horses were only a “countenance” for the intelligence-gathering mission of their courier.79 It is also possible that the plan had been for the book to be given to James by the two French ambassadors who arrived to check on him in January 1583 during the Ruthven Raid. There were fears that the raiders might panic and kill James.80 Henri III and Mary had both charged the ambassadors with congratulating James on being “associated with her in this crown, which would render the happy rule of the serene King her son very lawful”.81 James was already gaining a reputation as a master of political deception, so one of the ambassadors made a copy of his responses in writing for Mary. The ambassador acknowledged her instructions not to record the Association negotiations in writing but assured her that there was no harm in James keeping the original.82 James then sent a copy to Elizabeth to defend himself against accusations by the English ambassadors that he was keeping Association overtures secret from her.83 In this context of intercepted correspondence and leaked negotiations, the Xenophon presentation copy may have been intended as a seemingly innocuous and purposefully ambiguous gift that could slip past James’s minders and Elizabeth’s spies.

79Conclusion

In 1599, King James VI composed his own work in the mirror for princes genre: his Basilikon Doron. He informed his son Henry that “Zenophon, an old and famous writer … setteth down a faire patterne for the education of a young Kinge, under the supposed name of Cyrus”.84 Did he have in mind, or even to hand, the stunningly beautiful copy of Xenophon designed for him by John Gordon? We may never know whether the book reached its intended recipient, but it does not prevent us from drawing useful conclusions from it. Analysis of its complex title page has shown that John Gordon was not simply the author of its poem but also the designer of its visual content. Michael Bath’s analysis of Gordon as a vector for the transmission of emblems between monarchs can now be extended from Mary, Queen of Scots, and Henri III to James VI, with an additional transformation of the emblem “celebrated as the very model of a perfect impresa” across Europe.85 It is an important addition to Bath’s findings on the importance of emblems in Scottish decorative arts and architecture during this period.86 Gordon’s poem, translated into English for the first time here, has also been revealed to be an integral part of the page, directing interpretation of the surrounding images.

84Assessment of the quality and style of the illumination and binding has given us a sense of the investment of time and money required to transform the book into a deluxe gift object. By situating the title page in the context of the Association, this article has produced new evidence for the use of books as carriers of political imagery, as well as for the planning of the Association itself. In the febrile climate of fear and suspicion of the early 1580s, Mary’s agents appear to have conceived the Xenophon presentation copy as an alternative, subtler form of political overture. They would not have invested so much in the book’s production if they had not believed it would have some chance of success. It shows that, even as a teenager, James was expected to be adept in the interpretation of visual media. Studying emblem books was part of his education, and he emerged from the schoolroom at Stirling equipped to understand and engage in the ever-evolving flow of images that characterised and linked courts across Europe. It is vital that we bear this in mind when we consider him as King James VI and I. James had become an active participant in international European visual and material culture long before he transformed that of Elizabethan England.

Acknowledgements

With thanks to Claire Martin, Deputy to the Director of the Documentary Resource Centre, Petit Palais, for providing access to the book discussed in the article.

About the author

-

Alexandra Plane is a librarian and doctoral student completing a PhD on the Scottish and English libraries of King James VI and I, funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC), and co-supervised at Newcastle University and the National Library of Scotland. She co-curated the 2024–25 National Library of Scotland exhibition Renaissance: Scotland and Europe, 1480 to 1630.

Footnotes

-

1

Gitta Bertram, Nils Büttner, and Claus Zittel, “Introduction”, in Gateways to the Book: Frontispieces and Title Pages in Early Modern Europe, ed. Gitta Bertram, Nils Büttner, and Claus Zittel (Leiden: Brill, 2021), 4. ↩︎

-

2

Catalogue illustré des livres précieux, manuscrits et imprimés, faisant partie de la bibliothèque de M. Ambroise Firmin-Didot: Belles-lettres—histoire (Paris: Librairie Firmin-Didot, 1878), item 679, sold for 6,000 francs to Charles Porquet; Catalogue d’un choix de livres rares et précieux, manuscrits et imprimés, composant le cabinet de feu M. le Marquis de Ganay (Paris: Ch. Porquet, 1881), item 219, sold for 2,050 francs; Edouard Rahir, La collection Dutuit: Livres et manuscrits (Paris: Librairie Damascène Morgand, 1899), item 623. ↩︎

-

3

Nicolas Hatot and Marie Jacob, Trésors enluminés de Normandie: Une (re)découverte (Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2016), 274–75, no. 93. It was included in this exhibition on the grounds that it had been owned by the Dutuit brothers, who came from Normandy. ↩︎

-

4

Xenophōntos ta sōzomena biblia. Xenophontis (viri armoru[m] & literaru[m] laude celeberrimi) quae extant opera. Annotationes Henrici Stephani, multum locupletatae ([Geneva]: Henri Estienne, 1581), Petit Palais, Museum of Fine Arts of the City of Paris, Dutuit Collection, LDUT623. ↩︎

-

5

On Servin’s work and his presentation of it to James, see James Porter, “The Geneva Connection: Jean Servin’s Settings of the Latin Psalm Paraphrases of George Buchanan (1579)”, Acta Musicologica 81, no. 2 (2009): 229–54. ↩︎

-

6

On its title page, Estienne’s 1581 edition gives Paris as its place of printing, but it was actually printed in Geneva. Such false imprints were commonly used in the early modern period for various purposes including broadening the market for a book or evading censorship. ↩︎

-

7

Rahir, La collection Dutuit, 265. The inaccurate description of the ornately decorated copy of Estienne’s Xenophon as having “a manuscript dedication from the printer” has been repeated in modern sale catalogue descriptions for other books owned by James. See Maggs Bros., Books & Readers in Early Modern Britain VI, catalogue 1495 (London: Maggs Bros., 2017); Maggs Bros., Bookbinding in the British Isles: Sixteenth to the Twentieth Century, catalogue 1212 (London: Maggs Bros., 1996); and Bernard Quaritch, Early Books and Manuscripts (London: Bernard Quaritch, 2004). ↩︎

-

8

The workshop that we now refer to as the Geneva Kings’ Bindery was first identified by G. Hobson, “Une reliure aux armes d’Henri III”, in Les trésors des bibliothèques de France: Manuscrits, incunables, livres rares, dessins, estampes, objets d’art, curiosités bibliographiques, ed. R. Cantinelli and Amédée Boinet (Paris: G. van Oest, 1925), 147–59. It was then localised to Geneva and named by Ilse Schunke, “Der Genfer Bucheinband des sechzehnten Jahrhunderts und der Meister der französischen Königsbände”, Jahrbuch der Einbandkunst 4 (1937): 37–64. The workshop is thought to have been staffed in part or whole by Protestant binders who had moved to Geneva from Lyon. ↩︎

-

9

Hélène Cazes, “Le rameau et les couronnes: Deux oliviers aux titres de Henri Estienne (1530–1598)”, in La page de titre à la Renaissance, ed. Jean François Gilmont, Alexandre Vanautgaerden, and Françoise Deraedt (Turnhout: Brepols, 2008). ↩︎

-

10

For an overview of his life, see Dorothy Mackay Quynn, “The Career of John Gordon Dean of Salisbury, 1603–1619”, Historian 6, no. 1 (1943): 76–96. ↩︎

-

11

Calendar of the Cecil Papers in Hatfield House, vol. 2, 1572–1582 (London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1888), no. 120. ↩︎

-

12

Mary wrote to Beaton: “Maistre Jean Gordon a escrit quelque chose pour moy en langue latine, et a bonne volonté de me faire service … Maistre Jean Gordon m’a faict dire qu’il doibt quelque argent par dela, lequel il sera constrainct payer promptement; a ceste cause je vous prie davancer une annee sa pension, qui est de deux cents francs”. Quynn, “The Career of John Gordon”, 80. ↩︎

-

13

Quynn, “The Career of John Gordon”. ↩︎

-

14

John Gordon, “Autre allegorie de la Circé, selon l’opinion du sieur Gordon, escocois, Gentilhomme de la Chambre du Roy”, in Baltasar de Beaujoyeulx, Balet comique de la Royne, faict aux nopces de monsieur le duc de Joyeuse & madamoyselle de Vaudemont sa soeur (Paris: Adrian Le Roy, Robert Ballard, & Mamert Patisson, 1582), 74–76. ↩︎

-

15

Anne Daye, “The Role of ‘Le balet comique’ in Forging the Stuart Masque: Part 1 The Jacobean Initiative”, Dance Research 32, no. 2 (2014): 186; Frances A. Yates, The French Academies of the Sixteenth Century (London: Warburg Institute, 1947), 264; A. Stahler, “Inigo Jones’s ‘Tempe Restored’ and Alessandro Piccolomini’s ‘Della institution morale’”, Seventeenth Century 18, no. 2 (2003): 193. ↩︎

-

16

Michael Bath, Emblems in Scotland: Motifs and Meanings (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 108–9. ↩︎

-

17

Michael Bath, Emblems for a Queen: The Needlework of Mary Queen of Scots (London: Archetype, 2008), 42–47; Nuccio Ordine, Trois couronnes pour un roi: La devise d’Henri III et ses mystères (Paris: Belles Lettres, 2011); Michael Bath, “Symbols of Sovereignty: Political Emblems of Mary Queen of Scots”, in Immagini e potere nel Rinascimento europeo, ed. Giuseppe Cascione and Donato Mansueto (Milan: Ennerre, 2009), 53–67; Nuccio Ordine, “Manet Ultima Coelo or Tertia Coelo Manet? Mysteries of Henri Ill’s Impresa”, in Immagini e potere nel Rinascimento europeo, ed. Cascione and Mansueto, 15–38. ↩︎

-

18

It was later shipped to England and back again for repairs in anticipation of James’s 1617 homecoming to Scotland. Michael Bath, “Ben Jonson, William Fowler and the Pinkie Ceiling”, Architectural Heritage 18, no. 1 (2007): 73–86. ↩︎

-

19

Bath, “Symbols of Sovereignty”, 54. ↩︎

-

20

Susan Doran and Paulina Kewes, “The Earlier Elizabethan Succession Question Revisited”, in Doubtful and Dangerous: The Question of Succession in Late Elizabethan England, ed. Susan Doran and Paulina Kewes (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2014), 32. The gap will be filled by a forthcoming monograph on the Association by Doran and Kewes. ↩︎

-

21

Doran and Kewes, “The Earlier Elizabethan Succession Question Revisited”, 32–34; George Lasry, Norbert Biermann, and Satoshi Tomokiyo, “Deciphering Mary Stuart’s Lost Letters from 1578–1584”, Cryptologia 47, no. 2 (2023): 101–202. ↩︎

-

22

Collection of assorted letters, Bibliothèque Nationale de France (BnF), Français 20506, fol. 194. ↩︎

-

23

Lasry, Biermann, and Tomokiyo, “Deciphering Mary Stuart’s Lost Letters”, 146. ↩︎

-

24

State Papers Scotland Series I, Mary Queen of Scots, 1568–1587, The National Archive (TNA), SP 53/11, fol. 59; translated from the French original in William K. Boyd, Calendar of State Papers Relating to Scotland and Mary, Queen of Scots, 1547–1603, vol. 6, 1581–83 (Edinburgh: HM General Register House, 1910), no. 55. ↩︎

-

25

State Papers Scotland, Mary Queen of Scots, TNA, SP 53/11, 60, fol. 19r, translated from the French original in Boyd, Calendar of State Papers, no. 74. ↩︎

-

26

State Papers Scotland, Mary Queen of Scots, TNA, SP 53/11, 60, fol. 18v, in Boyd, Calendar of State Papers, no. 74. ↩︎

-

27

i.e., Henri Estienne. ↩︎

-

28

Cecrops was a mythical early king of Athens. ↩︎

-

29

i.e., both this dedicatory poem from John Gordon and the printed dedication to James by Henri Estienne on the following page. ↩︎

-

30

Literally, “thrice-great”. ↩︎

-

31

Literally meaning “sceptre”, the noun sceptrum is often used poetically in the plural, as here, to refer to a singular “kingdom”. It is possible that Gordon is alluding to the possibility of James ruling multiple kingdoms in future as potential successor to Elizabeth I. ↩︎

-

32

i.e., of death or destruction. ↩︎

-

33

i.e., Hercules. ↩︎

-

34

i.e., the Argo, carrying Jason and the Argonauts. ↩︎

-

35

Honey was classically associated with divine inspiration and poetic skill, and Mount Hymettos was famed for its honey. Strabo wrote that it was so delicious because it was smokeless (ἀκάπνιστον), that is, produced without fumigation of the hives (Geography, 9.1.23). See also Pausanias, Description of Greece, 1.2.1, and Pliny, Natural History, 11.13.32. With thanks to James Hua for these references. ↩︎

-

36

William Barlow, The Svmme and Svbstance of the Conference … at Hampton Court. Ianuary 14. 1603 (London: Iohn Windet for Mathew Law, 1604), 69. ↩︎

-

37

On the reception of Xenophon’s Cyropaedia in the medieval and early modern periods, see Noreen Humble, “Xenophon and the Instruction of Princes”, in The Cambridge Companion to Xenophon, ed. Michael A. Flower (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016), 429. She notes that “humanists of Calvinist persuasion were in fact responsible for the bulk of the editorial and commentary tradition on Xenophon’s works during the sixteenth century”, with the most notable being Henri Estienne. ↩︎

-

38

Xenophontos hapanta ta sozomena biblia. Xenophontis et imperatoris & philosophi clarissimi omnia, quae exstant, opera (Basel: Thomas Guarinus, 1569), National Library of Scotland, Bdg.l.33. James also owned a copy of the work in English, which he gave away to Agnes Graham, Lady Tullibardine. Catalogue of the library of King James VI of Scotland, British Library (BL), Add MS 34275, fol. 18v; George Frederic Warner, ed., The Library of James VI, 1575–1583, from a Manuscript in the Hand of Peter Young, His Tutor (Edinburgh: T. and A. Constable for Scottish History Society, 1893), lxix. ↩︎

-

39

“Lisant en Xenophon; [Cyrop. v. 2, 28] que Gadate auoit esté chastré pour ce que la concubine du Roy l’auoit regardé de bon oeil, le Roy dit que la femme deuoit plustost estre chastrée”. BL, Add MS 34275, fol. 2r, printed in Young, The Library of James VI, lxxiii. ↩︎

-

40

The “tapihire” is described in André Thevet, Les singularitéz de la France antarctique (Antwerp: C. Plantin, 1558), 96. For other early references to tapirs, see Frédéric Tinguely, “Jean de Léry et les métamorphoses du tapir”, Littératures 41, no. 1 (1999): 33–45. ↩︎

-

41

James’s copy is listed in BL, Add MS 34275, fol. 15v; printed in Young, The Library of James VI, lvii. Peter Mason, “André Thevet, Pierre Belon and Americana in the Embroideries of Mary Queen of Scots”, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 78 (2015): 207–21. ↩︎

-

42

Wilma B. George, Animals and Maps (London: Secker & Warburg, 1969), 77. She also suggests that a tapir may have appeared earlier in Guillaume Le Testu’s manuscript Cosmographie universelle of 1555 (p. 74). With thanks to Lisa Voigt for discussing early representation of tapirs with me and confirming that the animal depicted on the title page of the illuminated Xenophon resembles one. ↩︎

-

43

For the symbolism of the fasces in the early modern period, see T. Corey Brennan, The Fasces: A History of Ancient Rome’s Most Dangerous Political Symbol (New York: Oxford University Press, 2022), 120. ↩︎

-

44

The Argo Navis constellation was depicted with a similar starry design in medieval and Renaissance astronomical books, e.g., ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-Ṣūfī, “Kitāb ṣuwar al-kawākib al-ṯābita”, BnF, Arabe 5036, fol. 217r; Gaius Julius Hyginus, Poeticon astronomicon (Venice: Erhard Ratdolt, 1482), sig. f2v. ↩︎

-

45

Records and papers (originals and copies) concerning England and Scotland, 1568–1575, BL, Cotton MS Caligula C IV, fol. 24r. Killigrew went on to reveal that Gordon had “lately counterfeited the Earl of Huntly’s hand, and by that deceit got money of a Scottish merchant to the sum of six score French crowns”. ↩︎

-

46

John Elder, The Copie of a Letter sent in to Scotlande, of the Ariuall and Landynge, and Moste Noble Marryage of the Moste Illustre Prynce Philippe, Prynce of Spaine, to the Most Excellente Princes Marye Quene of England (London: John Waylande, 1555), sig. [B.vii]r. ↩︎

-

47

Bertram, Büttner, and Zittel, “Introduction”, 4. ↩︎

-

48

On the architectural genre of title pages, see Margery Corbett, “The Architectural Title Page”, Motif 12 (1964): 48–62; and Gitta Bertram, “Considerations on the History and the Analysis of Illustrated Title Pages”, in Gateways to the Book, ed. Bertram, Büttner, and Zittel, 79. ↩︎

-

49

Bertram, Büttner, and Zittel, “Introduction”, 29–30. ↩︎

-

50

Bertram, Büttner, and Zittel, “Introduction”, 6. ↩︎

-

51

On illuminators in Renaissance Paris more generally, see Anna Baydova, Illustrer le livre: Peintres et enlumineurs dans l’édition parisienne de la Renaissance (Tours: Presses Universitaires François Rabelais, 2023). ↩︎

-

52

Emile Picot, “Note sur l’enlumineur parisien Guillaume Richardière et sur son beau-père Philippe Danfrie”, Bulletin de la Société de l’Histoire de Paris et de l’Ile-de-France 16 (1889): 35–42. ↩︎

-

53

“Je, Guillaume Richardierre, ay faict l’enluminure du present missal … lequel j’ay achevé en cinq mois, aydé de deux compagnons, sans faire autre besoingne. Ledict seigneur m’a donné pour mes peines et sellon le marché faict, pour l’enluminure seulement, cent quarante escus d’or sol. La relieure a cousté quinze escus sol, le missal en blanc trois escus sol”. BnF, Rothschild 2528 (16 a), vellum leaf placed before text (author’s translation). ↩︎

-

54

Evangéliaire du Saint-Esprit (detached leaf), Bibliothèque et Archives du Musée Condé, Chantilly, Ms. 408 (XIX C [1] 15). On this surviving leaf of the Ordre du Saint-Esprit’s gospel book, see Valérie Auclair, L’art du manuscrit de la Renaissance en France (Paris: Somogy, 2001), 74–77. ↩︎

-

55

Fanfare bindings were first systematically defined in G. D. Hobson, Les reliures à la fanfare (London: Chiswick Press, 1935), 1–2. ↩︎

-

56

Hobson, Les reliures à la fanfare (1935), 23. Anthony R. Hobson later reprinted the book with additional examples that had come to light since his father first published it. G. D. Hobson, Les reliures à la fanfare, with additions and corrections by A. R. A. Hobson (Amsterdam: Gérard Th. van Heusden, 1970). ↩︎

-

57

Hobson, Les reliures à la fanfare (1935), 59. ↩︎

-

58

For a full list of owners, see Hobson, Les reliures à la fanfare (1935), 43–46. Mary, Queen of Scots owned one fanfare binding: Hobson, Les reliures à la fanfare (1935), item 34 on p. 14. ↩︎

-

59

The other royal owners were Elizabeth I; Maximilian II, Holy Roman Emperor; and Philip III of Spain. James was also given a four-volume set of books in fanfare bindings around 1601: item 175 in Hobson, Les reliures à la fanfare (1935), 23. ↩︎

-

60

The catalogues of the three collections to which it belonged in the nineteenth century all made the same attribution; see nn2–4 for references. It was also reproduced with the Eve attribution in “Guide raisonné de l’amateur et du curieux”, L’art: Revue Hebdomadaire Illustrée 2 (1881): 113. ↩︎

-

61

Hobson, Les reliures à la fanfare (1935), 51–52. ↩︎

-

62

Hobson, Les reliures à la fanfare (1935), 53–55. ↩︎

-

63

The tool is reproduced in Hobson, Les reliures à la fanfare (1935), 28. ↩︎

-

64

On Scrimgeour, see John Durkan, “Henry Scrimgeour, Renaissance Bookman”, Edinburgh Bibliographical Society Transactions 5, no. 1 (1978): 1–31. ↩︎

-

65

Xenophōntos ta sōzomena biblia, sig. ¶.ii.v. ↩︎

-

66

Andrea Alciato, “Emblemata Alciati, 8o”, BL, Add MS 34275, fol. 16v, in Warner, Library, lxi; Claude Paradin, “Metamorphose d’Ovide figurée, avec les devises heroiques de Paradin 8o”, BL, Add MS 34275, fol. 10v, in Warner, Library, lxxxvii; “Symbola Paradini. lat., 16o”, BL, Add MS 34275, fol. 16v, in Warner, Library, lx; Paolo Giovio, “Devises de Jovio en francoys, 4o”, BL, Add MS 34275, fol. 17v, in Warner, Library, lxvi; Guillaume de la Perrière, “La Morosophie de Guillaume de la Perriere, 8o”, BL, Add MS 34275, fol. 16v, in Warner, Library, lxii. ↩︎

-

67

Poems and other items of William Fowler, secretary to Queen Anna, late 16th century–first quarter of 17th century, National Library of Scotland, MS. 2063, fol. 272v, quoted in The Works of William Fowler: Secretary to Queen Anne, wife of James VI, vol. 3, ed. Henry W. Meikle, James Craigie, and John Purves (Edinburgh: W. Blackwood and Sons, 1940), xix. For the context of Fowler’s note, see Allison L. Steenson, The Hawthornden Manuscripts of William Fowler and the Jacobean Court, 1603–1612 (New York: Routledge, 2020), 29. ↩︎

-

68

James VI, The Essayes of a Prentise, in the Diuine Art of Poesie (Edinburgh: Thomas Vautroullier, 1584), sigs. [G2v–G3r]. ↩︎

-

69

William Fowler, A True Reportarie of the Most Triumphant, and Royal Accomplishment of the Baptisme of the Most Excellent, Right High, and Mightie Prince, Frederik Henry (Edinburgh: Robert Waldegrave, 1594). On James’s self-representation as Jason, see Clare McManus, “Marriage and the Performance of the Romance Quest: Anne of Denmark and the Stirling Baptismal Celebrations for Prince Henry”, in A Palace in the Wild: Essays of Vernacular Culture and Humanism in Late-Medieval and Renaissance Scotland, ed. L. A. J. R. Houwen, A. A. MacDonald, and S. L. Mapstone (Leuven: Peeters, 2000), 175–98; and Bath, Emblems in Scotland, 91–114. ↩︎

-

70

The cup was described as “apparently” surviving in Miles Kerr-Peterson and Michael Pearce, “King James VI’s English Subsidy and Danish Dowry Accounts, 1588–1596”, in Miscellany of the Scottish History Society, vol. 16 (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2020), 45. Their source is David Stevenson, Scotland’s Last Royal Wedding: The Marriage of James VI and Anne of Denmark (Edinburgh: John Donald, 1997), 130–31. ↩︎

-

71

National Museum of Denmark, inventory no. 74. James paid twenty-five dalers for it. Kerr-Peterson and Pearce, “King James VI’s English Subsidy and Danish Dowry Accounts”, 45. It has a maker’s mark with “MP” or “MF” (as yet unidentified) and an assay mark for Nuremberg. With thanks to Marie T. Laursen and Poul Grinder-Hansen of the National Museum of Denmark, and Rasmus Agertoft of the Rundetaarn, for their help in tracking down and viewing the cup. ↩︎

-

72

The notebook in which he recorded the contents of James’s library has one list dated 1583, but it is a record of a few books being moved rather than acquired. BL, Add MS 34275, fol. 10v, in Warner, Library, xxxv. ↩︎

-

73

Michel Maittaire, Annalium typographicorum tomus quintus et ultimus (London: Gul. Darres & Cl. Du Bosc., 1741), 562–63. The appendix referred to books omitted from the main text because they had been “seen later or found elsewhere”. ↩︎

-

74

State Papers Foreign, France, 1577–1780, TNA, SP 78/9, fol. 99. ↩︎

-

75

State Papers Foreign, France, 1577–1780, TNA, SP78/10, fol. 114. ↩︎

-

76

The courier, George Douglas, was the brother of the laird of Lochleven. He had previously helped Mary escape from Lochleven Castle. ↩︎

-

77

Records and papers, BL, Cotton MS Caligula C VII, fol. 68. ↩︎

-

78

That Douglas’s confessions were extracted under torture is reported by one of Mary’s correspondents, the Spanish ambassador to England Bernardino de Mendoza, writing to King Philip II. He added that the torture had been ordered by Elizabeth. Calendar of Letters and State Papers Relating to English Affairs: Preserved Principally in the Archives of Simancas, vol. 3, 1580–1586 (London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1896), no. 291. Copies of Douglas’s depositions can be found at State Papers Scotland Series I, Elizabeth I, 1558–1603, TNA, SP 52/30, fol. 309; and Swinton’s Kirk MSS, National Library of Scotland, MS. 31.2.19. ↩︎

-

79

State Papers Scotland, Elizabeth I, TNA, SP 52/30, fol. 258. By the summer of 1582 Guise, another backer of the Association, had tentative support from Spain and Rome to invade England and free Mary. Steven J. Reid, The Early Life of James VI: A Long Apprenticeship, 1566–1585 (Edinburgh: John Donald, 2023), 194–95. ↩︎

-

80

Calendar of State Papers (Simancas), vol. 3, no. 291. ↩︎

-

81

Mary’s instructions can be found in the recently decrypted BnF, 500 de Colbert 470, fol. 307, in Lasry, Biermann, and Tomokiyo, “Deciphering Mary Stuart’s Lost Letters”, 157. Henri III’s instructions can be found in State Papers Scotland, Mary Queen of Scots, TNA, SP 53/12, fol. 32; and State Papers Scotland, Elizabeth I, SP 52/31, fol. 19. ↩︎

-

82

State Papers Scotland, Mary Queen of Scots, TNA, SP 53/12, fol. 40. ↩︎

-

83

Robert Bowes and William Davison to [Walsingham], [7 February 1583], Records and papers, BL, Cotton MS Caligula C VII, fol. 126. ↩︎

-

84

James VI, Basilikon Doron Devided into Three Bookes (Edinburgh: Robert Waldegrave, 1599), 145. ↩︎

-

85

Bath, “Symbols of Sovereignty”, 53. ↩︎

-

86

Bath, Emblems in Scotland. ↩︎

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Bibliothèque et Archives du Musée Condé, Chantilly. Ms. 408, XIX C [1] 15. Evangéliaire du Saint-Esprit (detached leaf).

Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris. 500 de Colbert 470.

Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris. Arabe 5036. ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-Ṣūfī, “Kitāb ṣuwar al-kawākib al-ṯābita”.

Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris. Français 20506. Collection of assorted letters.

Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris. Rothschild 2528 (16 a).

British Library, London. Add MS 34275. Catalogue of the library of King James VI of Scotland, 1573–1583.

British Library, London. Cotton MS Caligula C IV. Records and papers (originals and copies) concerning England and Scotland, 1568–1575.

British Library, London. Cotton MS Caligula C VII. Records and papers (originals and copies) concerning England and Scotland, 1582–1584, including correspondence of Mary, Queen of Scots.

The Morgan Library & Museum, New York. PML 62835. Psalmi Davidis a G. Buchanano versibus expressi: Nunc primum modulis IIII. V. VI. VII. et VIII. vocum a I. Servino decantati. Tenor. Lyon [Geneva]: Charles Pesnot, 1579.

The National Archives, London. State Papers Foreign, France, 1577–1780. SP 78/9, SP 78/10.

The National Archives, London. State Papers Scotland Series I, Elizabeth I, 1558–1603. SP 52/30, 52/31.

The National Archives, London. State Papers Scotland Series I, Mary Queen of Scots, 1568–1587. SP 53/11, 53/12.

National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh. Bdg.l.33. Xenophontos hapanta ta sozomena biblia. Xenophontis et imperatoris & philosophi clarissimi omnia, quae exstant, opera. Basel: Thomas Guarinus, 1569.

National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh. MS. 2063. Poems and other items of William Fowler, secretary to Queen Anna, late 16th century–first quarter of 17th century.

National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh. MS. 31.2.19. Swinton’s Kirk MSS, a collection of Scottish historical documents, for the most part copies from the Cotton Library, 17th century.

Petit Palais, Museum of Fine Arts of the City of Paris, Dutuit Collection, LDUT623. Xenophōntos ta sōzomena biblia. Xenophontis (viri armoru[m] & literaru[m] laude celeberrimi) quae extant opera. Annotationes Henrici Stephani, multum locupletatae. [Geneva]: Henri Estienne, 1581.

Secondary Sources

Auclair, Valérie. L’art du manuscrit de la Renaissance en France. Paris: Somogy, 2001.

Barlow, William. The Svmme and Svbstance of the Conference … at Hampton Court. Ianuary 14. 1603. London: Iohn Windet for Mathew Law, 1604.

Bath, Michael. “Ben Jonson, William Fowler and the Pinkie Ceiling”. Architectural Heritage 18, no. 1 (2007): 73–86.

Bath, Michael. Emblems for a Queen: The Needlework of Mary Queen of Scots. London: Archetype, 2008.

Bath, Michael. Emblems in Scotland: Motifs and Meanings. Leiden: Brill, 2018.

Bath, Michael. “Symbols of Sovereignty: Political Emblems of Mary Queen of Scots”. In Immagini e potere nel Rinascimento europeo, edited by Giuseppe Cascione and Donato Mansueto, 53–67. Milan: Ennerre, 2009.

Baydova, Anna. Illustrer le livre: Peintres et enlumineurs dans l’édition parisienne de la Renaissance. Tours: Presses Universitaires François Rabelais, 2023.

Beaujoyeulx, Baltasar de. Balet comique de la Royne, faict aux nopces de monsieur le duc de Joyeuse & madamoyselle de Vaudemont sa soeur. Paris: Adrian Le Roy, Robert Ballard, & Mamert Patisson, 1582.

Bertram, Gitta. “Considerations on the History and the Analysis of Illustrated Title Pages”. In Gateways to the Book: Frontispieces and Title Pages in Early Modern Europe, edited by Gitta Bertram, Nils Büttner, and Claus Zittel, 61–91. Leiden: Brill, 2021.

Bertram, Gitta, Nils Büttner, and Claus Zittel, eds. Gateways to the Book: Frontispieces and Title Pages in Early Modern Europe. Leiden: Brill, 2021.

Bertram, Gitta, Nils Büttner, and Claus Zittel. “Introduction”. In Gateways to the Book: Frontispieces and Title Pages in Early Modern Europe, ed. Gitta Bertram, Nils Büttner, and Claus Zittel, 1–57. Leiden: Brill, 2021.

Boyd, William K. Calendar of State Papers Relating to Scotland and Mary, Queen of Scots, 1547–1603. Vol. 6, 1581–83. Edinburgh: HM General Register House, 1910.

Brennan, T. Corey. The Fasces: A History of Ancient Rome’s Most Dangerous Political Symbol. New York: Oxford University Press, 2022.

Calendar of the Cecil Papers in Hatfield House. Vol. 2, 1572–1582. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1888.

Calendar of Letters and State Papers Relating to English Affairs: Preserved Principally in the Archives of Simancas. Vol. 3, 1580–1586. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1896.

Catalogue d’un choix de livres rares et précieux, manuscrits et imprimés, composant le cabinet de feu M. le marquis de Ganay. Paris: Ch. Porquet, 1881.

Catalogue illustré des livres précieux, manuscrits et imprimés, faisant partie de la bibliothèque de M. Ambroise Firmin-Didot: Belles-lettres—histoire. Paris: Librairie Firmin-Didot, 1878.

Cazes, Hélène. “Le rameau et les couronnes: Deux oliviers aux titres de Henri Estienne (1530–1598)”. In La page de titre à la Renaissance, edited by Jean François Gilmont, Alexandre Vanautgaerden, and Françoise Deraedt, 185–209. Turnhout: Brepols, 2008.

Corbett, Margery. “The Architectural Title Page”. Motif 12 (1964): 48–62.

Daye, Anne. “The Role of ‘Le balet comique’ in Forging the Stuart Masque: Part 1 The Jacobean Initiative”. Dance Research 32, no. 2 (2014): 185–207.

Doran, Susan, and Paulina Kewes. “The Earlier Elizabethan Succession Question Revisited”. In Doubtful and Dangerous: The Question of Succession in Late Elizabethan England, edited by Susan Doran and Paulina Kewes, 20–44. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2014.

Durkan, John. “Henry Scrimgeour, Renaissance Bookman”. Edinburgh Bibliographical Society Transactions 5, no. 1 (1978): 1–31.

Elder, John. The Copie of a Letter Sent in to Scotlande, of the Ariuall and Landynge, and Moste Noble Marryage of the Moste Illustre Prynce Philippe, Prynce of Spaine, to the Most Excellente Princes Marye Quene of England. London: John Waylande, 1555.

Fowler, William. A True Reportarie of the Most Triumphant, and Royal Accomplishment of the Baptisme of the Most Excellent, Right High, and Mightie Prince, Frederik Henry. Edinburgh: Robert Waldegrave, 1594.

Fowler, William. The Works of William Fowler: Secretary to Queen Anne, Wife of James VI. Vol. 3. Edited by Henry W. Meikle, James Craigie, and John Purves. Edinburgh: W. Blackwood and Sons, 1940.

George, Wilma B. Animals and Maps. London: Secker & Warburg, 1969.

Gilmont, Jean François, Alexandre Vanautgaerden, and Françoise Deraedt. La page de titre à la Renaissance. Turnhout: Brepols, 2008.

“Guide raisonné de l’amateur et du curieux”. L’art: Revue Hebdomadaire Illustrée 2 (1881): 108–17.

Hatot, Nicolas, and Marie Jacob. Trésors enluminés de Normandie: Une (re)découverte. Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2016.

Hobson, G. “Une reliure aux armes d’Henri III”. In Les trésors des bibliothèques de France: Manuscrits, incunables, livres rares, dessins, estampes, objets d’art, curiosités bibliographiques, edited by R. Cantinelli and Amédée Boinet, 147–59. Paris: G. van Oest, 1925.

Hobson, G. D. Les reliures à la fanfare. London: Chiswick Press, 1935.

Hobson, G. D. Les reliures à la fanfare. With additions and corrections by Anthony R. A. Hobson. Amsterdam: Gérard Th. van Heusden, 1970.

Humble, Noreen. “Xenophon and the Instruction of Princes”. In The Cambridge Companion to Xenophon, edited by Michael A. Flower, 416–34. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016.

Hyginus, Gaius Julius. Poeticon astronomicon. Venice: Erhard Ratdolt, 1482.

James VI. Basilikon Doron Devided into Three Bookes. Edinburgh: Robert Waldegrave, 1599.

James VI. The Essayes of a Prentise, in the Diuine Art of Poesie. Edinburgh: Thomas Vautroullier, 1584.

Kerr-Peterson, Miles, and Michael Pearce. “King James VI’s English Subsidy and Danish Dowry Accounts, 1588–1596”. In Miscellany of the Scottish History Society, vol. 16, 1–94. Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2020.

Lasry, George, Norbert Biermann, and Satoshi Tomokiyo. “Deciphering Mary Stuart’s Lost Letters from 1578–1584”. Cryptologia 47, no. 2 (2023): 101–202.

Maggs Bros. Bookbinding in the British Isles: Sixteenth to the Twentieth Century. Catalogue 1212. London: Maggs Bros., 1996.

Maggs Bros. Books & Readers in Early Modern Britain VI. Catalogue 1495. London: Maggs Bros., 2017.

Maittaire, Michel. Annalium typographicorum tomus quintus et ultimus. London: Gul. Darres & Cl. Du Bosc., 1741.

Mason, Peter. “André Thevet, Pierre Belon and Americana in the Embroideries of Mary Queen of Scots”. Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 78 (2015): 207–21.

McManus, Clare. “Marriage and the Performance of the Romance Quest: Anne of Denmark and the Stirling Baptismal Celebrations for Prince Henry”. In A Palace in the Wild: Essays of Vernacular Culture and Humanism in Late-Medieval and Renaissance Scotland, edited by L. A. J. R. Houwen, A. A. MacDonald, and S. L. Mapstone, 175–98. Leuven: Peeters, 2000.

Ordine, Nuccio. “Manet Ultima Coelo or Tertia Coelo Manet? Mysteries of Henri Ill’s Impresa”. In Immagini e potere nel rinascimento Europeo, edited by Giuseppe Cascione and Donato Mansueto, 15–38. Milan: Ennerre, 2009.

Ordine, Nuccio. Trois couronnes pour un roi: La devise d’Henri III et ses mystères. Paris: Belles Lettres, 2011.

Picot, Emile. “Note sur l’enlumineur parisien Guillaume Richardière et sur son beau-père Philippe Danfrie”. Bulletin de la Société de l’Histoire de Paris et de l’Ile-de-France 16 (1889): 35–42.

Porter, James. “The Geneva Connection: Jean Servin’s Settings of the Latin Psalm Paraphrases of George Buchanan (1579)”. Acta Musicologica 81, no. 2 (2009): 229–54.

Quaritch, Bernard. Early Books and Manuscripts. London: Bernard Quaritch, 2004.

Quynn, Dorothy Mackay. “The Career of John Gordon Dean of Salisbury, 1603–1619”. Historian 6, no. 1 (1943): 76–96.

Rahir, Edouard. La collection Dutuit: Livres et manuscrits. Paris: Librairie Damascène Morgand, 1899.

Reid, Steven J. The Early Life of James VI: A Long Apprenticeship, 1566–1585. Edinburgh: John Donald, 2023.

Schunke, Ilse. “Der Genfer Bucheinband des sechzehnten Jahrhunderts und der Meister der französischen Königsbände”. Jahrbuch der Einbandkunst 4 (1937): 37–64.

Stahler, A. “Inigo Jones’s ‘Tempe Restored’ and Alessandro Piccolomini’s ‘Della Institution Morale’”. Seventeenth Century 18, no. 2 (2003): 180–210.

Steenson, Allison L. The Hawthornden Manuscripts of William Fowler and the Jacobean Court, 1603–1612. New York: Routledge, 2020.

Stevenson, David. Scotland’s Last Royal Wedding: The Marriage of James VI and Anne of Denmark. Edinburgh: John Donald, 1997.

Thevet, André. Les singularitéz de la France antarctique. Antwerp: C. Plantin, 1558.

Tinguely, Frédéric. “Jean de Léry et les métamorphoses du tapir”. Littératures 41, no. 1 (1999): 33–45.

Warner, George Frederic, ed. The Library of James VI, 1575–1583: From a Manuscript in the Hand of Peter Young, His Tutor. Edinburgh: T. and A. Constable for Scottish History Society, 1893.

Yates, Frances A. The French Academies of the Sixteenth Century. London: Warburg Institute, 1947.

Imprint

| Author | |

|---|---|

| Date | 18 December 2025 |

| Category | Article |

| Review status | Peer Reviewed (Double Blind) |

| License | Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) |

| Downloads | PDF format |

| Article DOI | https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-29/aplane |

| Cite as | Plane, Alexandra. “‘May They Associate’: Decoding an Illuminated Book Designed for King James VI in Paris by Agents of Mary, Queen of Scots.” In British Art Studies: Reframing King James VI and I (Edited by Kate Anderson, Jemma Field, and Catriona Murray.). London and New Haven: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art and Yale Center for British Art, 2025. https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-29/aplane. |