Dressing the Stuarts

Dressing the Stuarts: The Sartorial Politics of Mourning and Matrimony, 1612–1613

By Jemma Field

Abstract

This article focuses on a brief yet pivotal four-month period—November 1612 to February 1613—to examine how clothing and somatic display mediated grief, joy, and political expression at the Stuart court. Framed by two major events—the death of Henry, Prince of Wales, on 6 November 1612 and the marriage of Princess Elizabeth on 14 February 1613—the study explores how the royal family navigated public and private emotion through dress. Drawing particular attention to the three surviving Stuart children—Prince Henry, Princess Elizabeth, and Duke Charles—it brings together overlooked archival materials from the National Archives, Kew, with new readings of early Stuart portraiture, including two recently rediscovered images of Princess Elizabeth. Combining written, material, and visual evidence, the article interweaves the political with the personal to reveal how clothing and textiles could articulate and memorialise emotional experience, dynastic identity, and affective bonds at moments of profound transition.

Introduction

In his address to Parliament in 1614, King James VI and I declared that jewels were the embodiment of princely virtue and therefore requisite adornment for the royal body: “as I shall answere to allmighty god … my purity [is] like the mettell of golde of my crowne, my firmenes and clearenes like the pr[e]cious stones I weare”.1 The same held true for articles of dress, and the prominence given to fine fabrics, vivid colours, and elegant passementerie in early modern England was indicative of their high cost and expert craftsmanship, which in turn evidenced the wearer’s wealth and social prestige. Yet clothes, jewels, and accessories were also turned to individual account as people fashioned their bodily display to visualise religious identity, or to show their allegiance, virtue, favour, or dynastic membership. In the process of wear and signification, pieces of jewellery and apparel absorbed memories and meanings, which transformed them into material legacies that saw them regularly included in bequests and treasured as heirlooms.2 This article examines the political and personal value of clothing and bodily display vis-à-vis two major events at the Stuart court: the death of Henry, Prince of Wales, on 6 November 1612 and the wedding of Princess Elizabeth on 14 February 1613. It focuses on the three Stuart children—Prince Henry, Princess Elizabeth, and Duke Charles—and is based on overlooked archival material held in the National Archives (Kew) and complemented by a new analysis of several early Stuart portraits, including two recently re-identified portraits of Princess Elizabeth.3 By harnessing this rich seam of archival and visual evidence, it has been possible to recover this short window of time from November 1612 to February 1613—a four-month period filled with extreme elation and triumph and with devasting loss and sadness—as a distinct cultural moment in which the Jacobean court turned to the arts of tailoring and painting to record, memorialise, and actively shape its public meaning.

1The Stuart Court on the International Stage

In 1612, as summer turned to autumn, the Stuart court and the city of London were gripped by feverish activity as preparations were made to welcome Princess Elizabeth’s prospective husband, the Elector Palatine Frederick V, together with his extensive entourage. The Stuarts had long been inundated with offers of marriage from Brunswick, Hesse–Kassel, Hungary, Piedmont, Poland, the Palatinate, Savoy, Spain, and Sweden.4 Early modern royal marriages were, of course, intrinsically political, and for King James the question of Princess Elizabeth’s marriage was part of a larger diplomatic strategy to maintain his self-styled persona of rex pacificus by assuming a leading role in the preservation of a peaceful balance of power in Europe. In the first decade of his English reign, James enacted this role by ending the Anglo-Spanish War with the 1604 Treaty of London, smoothing England’s turbulent relations with Denmark–Norway and dispatching Stuart diplomats to the continent where they brokered several peace negotiations between warring European countries.5 It is well known that, within this rhetoric, James sought to marry his children alternately to Protestant and Catholic partners; Prince Henry would take a Catholic bride, while Princess Elizabeth would wed a Protestant groom.6 For Elizabeth’s suitors came an alliance with the three Protestant kingdoms of the Stuarts, connections through Anna of Denmark to Denmark–Norway and many of the powerful Protestant German lands, together with a dowry of £40,000.7

4At the Stuart court, the question of Elizabeth’s prospective husband, together with the new Stuart alliance that it would broker, was a hot topic. A surfeit of speculation, rumour, and politicking ensued as court attendees tried to decipher signs of favour while resident ambassadors and special envoys sought to further their own agendas. As early as January 1612, court observers were dwelling on the plausible victory of the Palatinate and anticipating that Frederick V would arrive at the English court to conclude the match.8 This was highly unusual, for the majority of early modern royal marriage matches were brokered from a distance as, over the course of several years, ambassadors, courtiers, messengers, and painters crossed between the prospective courts exchanging a multitude of portraits, gifts, and letters before the dynastic marriage alliance was concluded with the use of proxies.9 Yet, given the high political stakes of the marriage, the oversupply of suitors, and swirling rumours that Frederick was “afflicted by various hereditary diseases”, King James was not willing to risk a failed union and ordered that the young prince travel to London and personally meet the Stuarts.10

8Fanfare and celebration marked the arrival of the sixteen-year-old Frederick, together with a retinue of 150 men, on English shores on 16 October 1612.11 Lodged at Essex House, Frederick sparked an atmosphere of competitive sartorial display as the Venetian ambassador, Antonio Foscarini, recorded that the Palsgrave “changes his dress every day, and one is richer than another. All the gentlemen he has with him are covered with gold, chains, and jewels. He has fifty pages and grooms in crimson velvet liveries embroidered with gold, silver-brocade doublets, and each gentleman of his suite has his own livery. The English gentlemen vie with these, and so the whole city is full of animation”.12 Writing to the doge and senate, Foscarini later relayed Frederick’s first formal reception at Whitehall Palace where, as the ambassador recounted, the Stuarts stood “under a baldachino of gold brocade … The guard were all in rich dresses of velvet and gold; the Hall was thronged with Lords and Ladies in the richest robes and laden with jewels; a display that this kingdom could not excel”.13 The ambassador’s marked attention to the luxury goods on display underscores their political importance: costly textiles and precious jewels were evidence of the wealth, status, and sophistication of the wearer and were a physical demonstration of the popularity and stability of the associated dynasty.

11Dressing Princess Elizabeth

The image that Foscarini evocatively constructs is borne out by archival accounts and the pictorial record that showcase the clothing and accessories Elizabeth wore at the time of Frederick’s arrival, during her engagement, and at her wedding. Indeed, it was this distinctive style of dress that she wore insistently after relocating to her new marital court in Heidelberg. In a portrait of her painted by Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger around 1611, the adolescent Elizabeth wears a stiffened bodice, a low scooped neckline, close-fitting sleeves, thin hanging sleeves, an expansive wheel farthingale set with a deep flounce, and a standing collar supported by a crimson underpropper (fig. 1). The whole ensemble is fashioned from Italian silk brocade and trimmed with strips of spangled metal lace and silver buttons. The princess’s hair is worn in a high, tightly frizzed bouffant, achieved by setting supplementary pieces of false hair, or a full wig, over padded rolls. Elizabeth is thus dressed in the height of English court fashion and forged in the pictorial mould of her mother, Anna of Denmark, for the portrait bears a striking similarity—in fashion and accessories, in the use of the full-length format and three-quarter view to the right, and in having her arms gently rest on the farthingale and delicately grasp a large feathered fan—to the type of portrait that Gheeraerts created for Anna between 1611 and 1614.14 Importantly, this portrait of Elizabeth would have been viewed alongside an image of her mother, for it was sent together with portraits of James, Anna, and Henry, to Duke Charles Emmanuel I of Savoy as part of a double Stuart–Savoy marriage proposal.15 The visual echo heightened Elizabeth’s marriageability, for it underscored her legitimacy and associated fertility; she was a daughter of the house of Stuart and, as her mother had successfully borne several children, so too would Elizabeth. There is a further statement of Elizabeth’s feminine virtues in the inclusion of the small black dog, a common symbol of loyalty and marital fidelity. More generally, portraits were central to diplomatic marriage negotiations for their ability to broadcast the sitter’s fashionability, wealth, and social standing through the careful delineation of the dressed body covered in costly textiles, precious metals, pearls, and gems that had been expertly fashioned by a multitude of artificers.

14

As for all royal figures, Elizabeth’s wardrobe staff were a key part of her household and her sociopolitical identity. Among the most important of these was her tailor, John Spence. He played a leading role in dressing Elizabeth during her nuptial season and provisioning her with the new garments for her wedding trousseau that she would take with her to Heidelberg. The orders placed with Spence were extensive and included twenty-three gowns, nine petticoats, two pairs of bodies stiffened with whalebone, five farthingales, two mantles, a doublet, two nightgowns, and two safeguards.16 Elizabeth’s trousseau is considered in more detail later but, in addition to Spence’s work, we know from surviving accounts that she ordered numerous waistcoats, coifs, cross-cloths, forehead-cloths, and silk stockings that were richly embroidered with gold, silver, and coloured silk thread, as well as ruffs and cuffs of fine cambric and lawn embellished with cutwork or bobbin lace. In addition, accessories that were mandatory for the female English wardrobe—hats, feathers, fans, gloves, pins, garters, scarves, and ribbons—were purchased in large quantities.17 The periwigs and hair pieces required to achieve the impressive bouffant style that could bear the weight of numerous jewels, ribbons, and feathers were supplied to Elizabeth by two tire-women, Mrs. Swanton and Mrs. Roberts.18

16Taken as a whole, the orders made during this period were undoubtedly made with an eye to completing Elizabeth’s trousseau, although she would have worn many of the pieces prior to her departure—not least of all her wedding attire—and all the goods needed suited to her station and reflective of the wealth, craftsmanship, and fashions of the Stuart court.19 The political significance of her wardrobe is reflected in the high cost—King James sanctioned at least £16,013 for her clothing and jewellery, her servants’ liveries, and her bridal chamber.20 Following her marriage, Elizabeth would then receive an annual allowance to purchase twenty-four new gowns every year, as well as £600 worth of ribbons, stockings, and lace.21 Again, the attention paid to her sartorial buying power was political: at the most basic level Elizabeth’s attire would now be a visual statement of the financial strength and social position of her husband.

19Dressing Henry, Prince of Wales

On the side of the Stuarts, Princess Elizabeth shouldered the principal responsibility for concluding the marriage with the Wittelsbachs, but her elder brother, Henry, played a key role in amplifying the attraction of an alliance with their family. As King James’s eldest son and heir, Henry embodied the future of the multiple Stuart kingdoms; he showcased the dynastic longevity, wealth, sophistication, and military strength of the royal family. Aged eighteen, he was a precocious and athletic young adult with pronounced interests in art, architecture, theatre, and military pursuits. He was widely celebrated in his own lifetime, and posthumously, as a militantly Protestant prince who would see Britain once again engage in heroic military endeavours in the name of the true religion and vanquish the dominance of Catholic Spain and France.22 Supporting this persona, most surviving portraits of Henry show him wearing armour, yet Henry’s wardrobe accounts testify to his fondness for fine fabrics and costly embroidery.23 The most informative surviving records are the accounts compiled by Sir David Murray, Master of the Prince’s Wardrobe. The last full year of accounts prior to Henry’s death, running from Michaelmas 1611 through Michaelmas 1612, includes entries of individual garments and whole suits, material costs, and workmanship.24 These detailed and extensive records pointedly evidence the care and attention that went into the prince’s somatic presentation. Henry’s tailor was central to his image, as his sister Elizabeth’s was to hers. This office was first filled by Alexander Wilson, who journeyed with the Stuarts from Scotland and who was later joined by the Scotsman Patrick Black.25

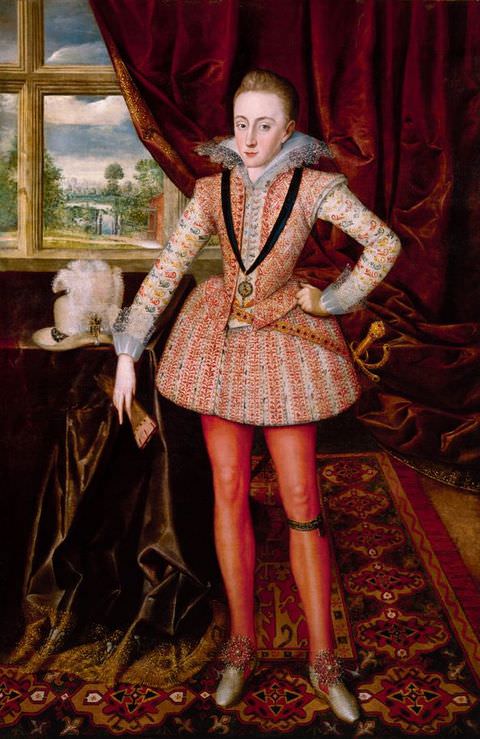

22Murray’s account book informs us that Henry’s set of foundational garments—the so-called suit—consisted of a doublet and hose and sometimes a jerkin. To this Henry added neckwear and cuffs made from fine linen—mostly holland or cambric—and a cloak lined with either velvet or shag.26 One surviving full-length portrait of the prince, painted by Robert Peake the Elder, when he was around sixteen years old, shows him in court dress rather than armour (fig. 2). Dressed in a palette of carnation (pale pink) and white, Henry wears a jerkin and matching pair of short, padded trunk-hose that are heavily embroidered with red silk (notice Peake’s considered effort to show the raised, textured quality of the needlework), together with a fitted doublet of brocaded silk, carnation silk stockings, and heeled shoes topped with large spangled rosettes. In his portrait, as in his accounts, Henry’s suit is accompanied by a host of accessories requisite for elite males in this period—hat, gloves, garters, and a sword or rapier worn across the body by dint of a hanger and girdle. We know from the records that Henry ordered these items in large quantities. For example, for the 1611–12 year, Henry ordered forty suits, together with an additional ten doublets, thirty-seven cloaks, 263 pairs of gloves, sixteen beaver hats, seventy-two pairs of velvet boothose, sixty-five pairs of garters, and fifty-two pairs of long silk hose, together with 164 pairs of shoes and seventy-nine pairs of boots.27 This was a prince deeply concerned with sartorial splendour, a prince who well understood that he was always being assessed and appraised as a somatic sign of the wealth, and therefore health, of the dynastic house of Stuart.28

26

The majority of Henry’s suits were matching ensembles made from a single textile, which then allowed for individual garments to be mixed and matched to make up a different suit. In January 1612, for example, Henry had an ensuite set of clothes made (consisting of a doublet, paned bullion-hose, and canions) from crimson velvet costing thirty shillings per yard. These garments were trimmed with gold and silver parchment and loop lace, studded with ninety-six gold and silver buttons, and finished with twenty-four yards of ribbon; the whole suit cost just over £60.29 This was not expensive by court standards and, as the arrival of Frederick V drew nearer, Henry’s wardrobe expenditure increased significantly as he prepared to embody the financial and political might of the Stuarts for the viewership of his European counterparts.

29Henry’s wardrobe accounts, dating from Michaelmas 1612, record ten new suits, six cloaks, two extra doublets, one gown, and one nightgown.30 Some of these garments—six of the suits and five of the cloaks—were being worked on by Henry’s wardrobe staff at the time of his death and were likely intended for him to wear during the wedding festivities. Described as being “unmade up” on his death, these suits were, on the whole, more expensive than any garment previously recorded in the prince’s accounts; many were heavily embellished, with £230 spent on “imbrothering” a black satin suit and cloak “wth silver purles and silke”.31 The active workings of his wardrobe were further seen in the list of “provision for apparel uncut” that listed lengths of textiles amounting to £768 2s. 2d., wherein the majority were earmarked for a specific garment, such as the “iij yards half white cloth of tyshewe [tissue] for a doublet”.32 The suites of planned clothing were all made from extremely fine silk fabrics—velvet, taffeta, and satin—and Henry chose a limited palette of black paired with a range of red hues—rose, carnation, crimson, scarlet, and ash (a flame-coloured orangey-red). Henry’s choice of sartorial embellishment showed a marked increase in opulence and cost, moving from the predominant use of decorative cutting techniques to large quantities of silk and precious metal embroidery. Indeed, the costliest outfit Henry ever ordered was a jerkin and hose of crimson satin paired with a cloak of scarlet satin that were covered with £320 worth of Venetian gold and silver embroidery.33 Importantly too, Henry began at this time to order cloth of tissue for his clothing. This was the most expensive textile to produce, as it required a large quantity of precious metal to be woven into the silk textile (usually as the weft thread) and pulled into little loops that stood proud of the fabric ground.34 For example, one of Henry’s doublets was made from carnation cloth of tissue that was almost unbelievably expensive at £18 10s. per yard.35

30These opulent garments were intended for public show, but Henry also paid close attention to the clothes he would wear in comparatively private, informal settings. He was, of course, expected to personally entertain Frederick V and the other members of the European nobility who had arrived in England ahead of the marriage, including Prince Maurits of Nassau and Henry Frederick, Prince of Orange. It was crucial, even in restricted spaces, that Henry sartorially proclaimed the wealth and associated power of the Stuarts. Thus, we find the prince ordering a lavish nightgown that would have been long and open-fronted in the manner of that worn by Ludovic Stuart, duke of Lennox and Richmond, in a portrait from the studio of Daniel Mytens, and an extant example of which can now be seen in the Verney Collection (figs. 3 and 4). The nightgown was a warm and comfortable, yet luxurious, garment worn by men and women in the relative privacy of the home.36 It was intrinsically associated with warmth and intimacy, but Prince Henry’s nightgown was made wholly to impress. It was fashioned from crimson velvet, lined with yellow shag, and embroidered all over with £220 worth of gold purles.37 It was finished just two weeks after the arrival of Frederick and his entourage. What emerges from the archival evidence of 1612 is that the heir to the Stuart throne was consciously increasing his wardrobe expenditure to ensure that he was dressed in the most magnificent clothes that money could buy. Henry’s somatic display would be readily seen and understood by onlookers as evidence of the Stuarts’ financial might which, in turn, evidenced the dynasty’s ability to secure subject loyalty and marshal military resources.

36

Dressing Charles, Duke of Cornwall

In comparison to Henry, we have far less archival evidence for Charles’s clothes during these years. The documents that do survive indicate that Charles favoured black over all other colours, followed by green, rose, tawny, hair-colour, and grisdeline (pale purple or grey-violet).38 The preference for black accords with Henry’s, and both princes favoured green, although this is unsurprising given the tradition of wearing green for riding and hunting in the summer months.39 One other notable similarity between the princes’ wardrobes was the use of slashing, pinking, and ravelling as means of adding decorative embellishment to their clothes—a design choice that can be seen in the doublet Charles wears in a portrait by Robert Peake (fig. 5).40 As mentioned, it was the arrival of the coterie of European elites that spurred Henry to switch from using cutting techniques, strips of lace, and ribbons to favouring costlier embroidery as the primary means of decorating his clothing.

38

The visual evidence from the early 1610s presents Charles in expensive materials and dyestuffs, wearing clothes of crimson (reddish purple), scarlet (reddish orange), carnation, and silver. The overall silhouette is formed by a close-fitting doublet with a natural waistline and short tabs, breeches that are long and full, and a cloak that is slung over the left shoulder. In a full-length portrait from 1613, the thirteen-year-old Charles is dressed ensuite in doublet and breaches of carnation taffeta with a matching cloak lined with shag (see fig. 5). An earlier portrait, painted when Charles was around ten years old, shows him sporting the same style with a doublet of cloth of silver, knee-length padded breeches, and a cloak of scarlet silk trimmed with silver braid (fig. 6). In both portraits, like the portrait of the sixteen-year-old Prince Henry discussed earlier (see fig. 2), Charles wears silk stockings and heeled shoes with large decorative roses, and a white beaver hat sits prominently on a table. The brothers wear very different styles of breeches, both of which were considered fashionable at court. It may be that Charles, as the younger son, sought an air of added gravitas and sophistication by donning the knee-length breeches; the longer style was routinely worn for ceremonials and was certainly on show throughout the Stuart–Wittelsbach marriage celebrations.41

41

Mourning Prince Henry

Throughout October, while many contemporaries were, as expected, marvelling over the astonishing levels of expenditure and display visible in London and Westminster, concern and anxiety about Prince Henry’s health was simultaneously rippling through the court. Sir Charles Cornwallis asserted that “the whole world did almost every hour send unto Saint James’s for news”, while John Chamberlain wrote in exalted terms about the feast at Guildhall that was held in Frederick’s honour, but noted sombrely that Prince Henry was too sick to attend.42 Although he had been unwell throughout October, Prince Henry was expected to recover, and it was not until 5 November that the Stuarts were informed that his illness was fatal; the following day, just before 8 pm, the eighteen-year-old Henry, Prince of Wales, died.43 An outpouring of lamentable sorrow rapidly followed as songs, sermons, poems, and prints were issued. A period of mourning descended on the kingdom, which required sartorial volte-face.44 Somatic display was immediately marshalled to express the sad interior state of heart and mind, with one eyewitness poignantly discerning that “the nuptial festivities of this house are turned to mournful trappings” as people changed “their festal robes into mourning for the Prince”.45

42In Westminster, the central spaces and key members of the court were chromatically and textually transformed into an emotive landscape of solemnity, remembrance, and respect. Prince Henry’s principal residence of St. James’s Palace was hung with black cloth inside and out. The privy, presence, and great chambers, together with the privy closet, chapel, and lobby, were outfitted with new chairs and stools upholstered in black velvet, while black canopies, carpets, and cushions were ordered, and the rooms, windows, and cupboards hung with a combination of black velvet and taffeta trimmed with ribbons and tassels. Black cloth spilled out onto the exterior of the palace, with 240 yards of bayes running in one border from the great chamber door, down the stairs, along through the base court and over the outer gate. Westminster Abbey, where the funeral and interment were to take place, was likewise made over in black textiles while portions of mourning cloth were allocated to Elizabeth, Charles, and Frederick V; to a number of servitors in each of the five Stuart households; and to a long list of European dignitaries, together with their attendants. In total, the black cloth “provided for the roabes and liveries of the mourners” amounted to 10,141 yards at a total cost of £7,081 16s. 6d.46 Significant further expenses were incurred by the materials purchased to outfit the architectural spaces and fashion the monuments, transportation means, and heraldic devices that were requisite for a royal funeral.47

46In death, as in life, the prince’s wardrobe staff were responsible for suitably clothing Henry’s body. They tenderly wrapped his body in two yards of scarlet—a finely spun woollen cloth—and provided the textiles required for the embalming with twenty-five ells of strong holland and eighteen ells of taffeta in shades of crimson, carnation, and yellow.48 They also provisioned the clothes to dress the life-size painted and gilded wooden effigy of the prince: a crimson velvet robe furred with miniver, with crimson satin sleeves, together with a cape of crimson velvet and a furred and gilded coronet set with blue and red stones, pearls, and garnets, as well as the ribbon for “tyeing the picture [effigy] to the coffyn” (fig. 7).49 Attending the funeral procession on 7 December 1612, Isaac Wake dwelt on the sartorial magnificence of the deceased prince, asserting the emotional power of clothing to recall an individual and thereby heighten both the liveliness of Henry’s wooden proxy and the emotional response: “under that [the canopy] laye the goodly image of that lovely Prince clothed wth ye ritchest garments he had, wch did so lively represent his person, as yt it did not onely drawe tears from ye severest beholders, but cause a fearful outcrie among ye people as if they felt at ye present their owne ruin in that loss”.50

48

The day after Henry’s death, James penned a grief-stricken letter to his brother-in-law King Christian IV of Denmark–Norway, writing that so “serious for us is the grief that we can scarcely express out loud … we believe that you will be so disheartened that we are expressing our grief rather sparingly lest the grave and sorrowful narration of the event itself increase the sadness immeasurably”.51 A measured, dignified expression of grief was also key to maintaining subject loyalty and support. It was important that the Stuarts performed a public demonstration of grief that adequately captured the significance of the national loss that was Henry’s death. Yet they also needed to reassure their subjects that the death of the heir did not spell a dynastic crisis; they could not be seen to be overly emotional or fragile, and certain royal duties such as receiving dignitaries, holding audiences, and enacting court ceremonial had to continue.52 This was a difficult, perhaps even an impossible, ask, and it was reported with a hint of disapprobation that “even in the midst of the most important discussions he [James] will burst out with ‘Henry is dead, Henry is dead’”.53 Queen Anna, for her part, retreated from court life into dark, secluded mourning spaces but she continued to receive courtiers and officials with impressive decorum, and Wake reported that “she was in hir bedchamber yt was hung wth black, & kept so darke yt ye greatest light came from hir owne eyes; but she spake in so good a tune, as yt it seemed sorrowe had not broke hir heart but that she had wisdom enough to master passions”.54 This balancing act extended to the sartorial. When James determined to install Frederick V as a Knight of the Order of the Garter in early January 1613, it was observed that the ceremony was conducted with “the knight’s wearing their robes over their mourning”.55

51Princess Elizabeth in Mourning

For Elizabeth, the radiant, sparkling, lustrous textiles and jewels that she had sported in her nuptial season were immediately replaced by a monochromatic palette. Garments and jewellery were drained of colour, and their glittering, shimmering potential was dampened. Wardrobe accounts confirm that Elizabeth continued to dress in high court fashion throughout the mourning period but that she darkened her wardrobe, choosing black materials to visualise her dolour. John Spence, Elizabeth’s tailor, fashioned her four new gowns and two petticoats from black silk rash and tamin (woollen cloth), and provided her with new farthingales and bodies stiffened with whalebone. Elizabeth also purchased six mourning ruffs, a pair of black roses for her shoes, quantities of black ribbon, and two yards of black tiffany (transparent silk fabric), which she may have used as a veil. From La Forte, a French artisan, Elizabeth ordered new mourning head attires and rebato wires.56

56A three-quarter-length portrait of the princess painted by Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger neatly accords with the archival evidence, indicating that Elizabeth’s painted persona reflected reality with a silhouette dominated by the drum farthingale, stiffened bodies, hanging sleeves, and a large ruff (fig. 8). She continued to present a visual statement of royal status, affluence, and fashionability, but sartorial choices were made to signal her bereavement. Perhaps most notably, the portrait shows Elizabeth marshalling modesty as appropriate to her grief-stricken state: the low-cut decolletage favoured at court has been replaced by a high-necked gown topped by a large linen ruff that is edged with bobbin lace. Beneath this, Elizabeth wears a monochromatic black gown of silk damask woven with a diamond pattern and small floral motifs.57 Her jewellery is dominated by black jet, which makes up her earrings and a large, three-stranded necklace. The understated nature of the outfit is slightly tempered by the open skirts, which allow for puffs of cloth of gold and silver to be pulled through, and by the locket pinned to her left breast, which is fashioned from carnelian, edged with tiny seed pearls, and finished with a large hanging pearl pendant. Yet the locket is almost certainly a token of remembrance, and contemporary viewers would have interpreted it as a miniature portrait of Prince Henry. Worn prominently at court, this miniature, together with sombre mourning clothes, materially transformed the royal female body into a site of commemoration and loss. At the same time, however, the very presence of Elizabeth’s royal body testified to the strength of the Stuart dynasty; not only had Prince Henry’s death increased her significance to the Stuart succession, but her impending wedding heightened the perception of her body as a site of reproductive potential and dynastic continuity. Importantly too, we know that copies of this portrait were made with a surviving full-length version now in the collection of Welbeck Abbey, Nottinghamshire, which testifies to its currency.

57

Miniatures of Elizabeth were also made that record the princess in mourning (fig. 9). Painted by Nicholas Hilliard, she appears at the height of court fashion—a smooth boned bodice, a large flounce pinned over the wheel farthingale, and thin hanging sleeves—with the ensemble fashioned entirely from black textiles. She again wears mourning head attire—a delicate black lace cap pinned over her bouffant—but she now wears a standing lace collar coupled with a plunging neckline, which is sanctioned by the private, intimate nature of the miniature art form. The body is once more marked as a site of remembrance by the large silk armband, while the furred muff adds a sartorial notation of temporal specificity—Henry’s death and the mourning period that ensued occurred during the winter months of 1612–13. When Hilliard designed a double portrait of Elizabeth and her young son Frederick Henry for printing (fig. 10), he seems to have drawn on the face pattern and dress details that he had depicted in the miniature two years earlier.58 The engraving was never produced; it may have been considered too provocative, for it clearly shows her passing the royal sceptre to her infant son—tacitly enacting the line of succession. From the moment of Henry’s death in 1612 until the birth of Charles’s first child in 1630, Elizabeth was heiress presumptive, and her children were crucial to the dynastic security of the Stuart kingdom. Indeed, James came under serious pressure to keep Elizabeth and Frederick in England to guard against a possible hereditary crisis.59

58

One further portrait of Elizabeth, painted by an unknown artist, commemorates Henry’s passing (fig. 11). The painting is commonly discussed in the context of her marriage and/or of Henry’s death, for it broadcasts Elizabeth’s natal identity through the supporters and symbols of the Stuart coat of arms that are woven into her lace collar and neckline, and announces her grief by way of the voluminous black armband and black locket.60 Once more, the princess’s body is preserved in paint as a site of dynastic pride, familial bonds, and memorialisation. Taken together, this collection of Elizabeth’s mourning portraits underscores the intensity of the emotion that surrounded Henry’s death, and demonstrates the desire among the royal family and their subjects to preserve their affection, loyalty, and loss visually. Whether gifted by the royal sitter or commissioned by a devoted subject, a portrait of the princess clothed in grief captured a particular historic moment and paid tribute to the virtuous and important life that was lost, and to the power and endurance of the monarchy.61

60

Charles in Mourning

Charles too continued to honour the memory of his brother long after Henry’s death. For Charles the death of Henry was personally and politically monumental; not only did he lose his elder brother—a figure to whom he had looked up his entire life—but he also lost his position as the second son.62 He was now thrust into the spotlight as the heir to the throne and had to shoulder the weight and expectation of dynastic success and longevity. As a result, Charles sought to pictorially appropriate Henry’s highly politicised, well-established, and successful persona of the gallant warrior prince; his portraits began to meaningfully include military and chivalric elements with garter regalia, armour, and weaponry. Most notably, he was painted by Paul van Somer in 1616 wearing Prince Henry’s distinctive suit of tourney armour that had been made by Jacob Halder at the royal armouries in Greenwich and gifted by Sir Henry Lee around 1608 (fig. 12).63 Later, during his own reign, Charles visually resurrected his brother’s martial memory by commissioning Anthony van Dyck to paint a portrait of Henry some twenty-one years after his death, clad again in this identifiable suit of Greenwich armour (fig. 13).64 Charles was using the power of portraiture to control Henry’s memorialisation and bolster his own position, visually asserting himself as the inheritor of his famed brother’s sober, militant, and chivalric legacy. Charles inherited not only Henry’s persona but also much of his household. Notably, Henry’s tailor, Patrick Black, soon transferred to Charles’s service, in which he was confirmed in office on 3 July 1613; thereafter he was chiefly responsible for Charles’s somatic display, as he had been for his elder brother.65

62

Material Legacy and Remembrance

As well as commemorative portraits, the Stuarts embraced material forms of remembrance with Elizabeth requesting one of Henry’s nightgowns. The garment evidently carried strong emotive value, for she paid the delivery man, Mr. Hart, the extremely high sum of £5 in gratitude.66 Although it is impossible to definitively identify which of Henry’s nightgowns Elizabeth received, it is probable that it was one of the two nightgowns that Henry ordered in late 1612 and that was therefore in current rotation in his wardrobe. One was a nightgown fashioned from hair-coloured figured taffeta, trimmed with hair-coloured silk lace, and lined with hair-coloured damask.67 The second nightgown, as mentioned earlier, was finished only weeks before Henry’s death and was fashioned from costly crimson velvet, lined with yellow shag, and embroidered all over with gold.68

66Elizabeth may have worn Henry’s nightgown, as it was one of the very few garments alongside the loose cloak that could feasibly be worn by men and women without flouting gender boundaries.69 Alternatively, she might have refashioned the fabric into other garments or kept the nightgown and never worn it. Either way, it is Elizabeth’s ownership that is important. It is an example of what Elizabeth Hallam and Jenny Hockey define as a “memory object”, as it was “infused with significance beyond [its] material existence or monetary value”.70 Although the nightgown was both expensive and finely crafted, Elizabeth’s impulse turned less on its material value than on claiming its past—on holding on to a tangible link to its previous beloved owner.71 Indeed, the very fabric of the nightgown was invested with Henry’s physical imprint and was richly evocative of his memory.72 While mourning dress served as a temporary marker of grief and remembrance, the decision to have portraits made, to commission posthumous portraits, or to obtain sartorial keepsakes was an enduring means of commemorating Henry’s virtuous life and its devastating loss.

69The Stuart–Wittelsbach Wedding

For the Stuart family, brokering Elizabeth’s marriage while processing grief was challenging, but the wedding did provide an opportune stage for the public demonstration of their dynastic strength and continuity. This was a union that would cement a new Protestant alliance and begin a new branch of the Stuart dynasty. On Sunday 26 December 1612, Elizabeth and Frederick were contractually married in the Banqueting House at Whitehall; the ceremony was held after Henry’s funeral but still within the official mourning period. Elizabeth and Charles were appropriately attired in black satin, with a nod to the joyous occasion in the quantity of lustrous, gleaming silver trimmings they both wore.73 This sartorial balancing act was noted by observers who referred to their clothing as “an even mixture of joy and mourning”, and it was noted that they “afterwards resumed their mourning” dress.74 The mourning period officially ended on 5 February 1613 and the wedding day finally dawned on 14 February 1613.75

73Once again, sumptuous textiles, costly trimmings, and precious jewels were the order of the day as elites sought to outdo one another with their magnificence. As one of the resident ambassadors in London recalled: “for many days we have heard nothing in this City but the … blare of trumpets, nor seen aught but a crush of nobles and gorgeous dresses and all the signs of rejoicing”.76 Elizabeth’s tailor, John Spence, was responsible for the luxurious clothes that the princess and her ladies wore throughout the five-day wedding extravaganza. The visiting French ambassador reported rather poetically that Elizabeth wore a “gown of silver, embroidered with gold and completely covered in diamonds” and that her female attendants were “so richly dressed in white and covered in jewels that they seemed like so many stars accompanying the moon”.77 The archival records confirm that Elizabeth’s wedding dress consisted of a train gown fashioned from cloth of silver embroidered all over with flowers, and covered in lace woven from silk and metal threads, while her bridesmaids wore cloth of silver trimmed with silver loop lace.78 As mentioned earlier, Spence also took a central role in the provision of Elizabeth’s trousseau that she would carry with her to wear in her new home. This set of clothing was fashioned from extremely expensive textiles and in a kaleidoscope of colours, with satins of deer colour, sea-green, grass-green, black, tawny, carnation, and murrey; velvets of tawny and silver; grosgrains of silver, ash colour, and black; and cloth woven with precious metal threads such as white cloth of silver, tawny cloth of gold, and black cloth of silver. To this were added large quantities of buttons, embroidery, fringe, lace, loops, and ribbons that were fashioned from coloured silks and large amounts of gold and silver. What is particularly notable about Elizabeth’s trousseau is the amount of cloth of tissue it contained; fifteen of the twenty-three gowns that Spence made were of cloth of tissue.79

76The warrant for the trousseau clearly shows Elizabeth taking English court fashion with her: the distinctive structural undergarments of drum farthingale and stiffened bodies that provided the characteristic silhouette of the flat, firm torso and cylindrical hips, together with wearing and hanging sleeves, standing collars, and plunging necklines. Indeed, her continued adherence to English styles caused significant alarm and gave rise to protest from her new subjects, who objected to the extremely low-cut décolletage.80 Beyond questions of decorum, however, Elizabeth’s new subjects would have understood her unfamiliar style of dress as evidence of her foreign loyalties and allegiances. Most royal brides faced the expectation of sartorial assimilation at their new marital court, but many women, including Elizabeth, strove to retain their natal styles and used their wardrobes to showcase familial pride and dynastic status.81 Elizabeth’s sartorial obstinacy is most constructively understood within the wider context of her marital disagreement over prestige and precedence. As Rebecca Calcagno observes, Elizabeth believed that, as a princess of the multiple Stuart kingdom of England, Ireland, and Scotland, she outranked her husband, a German count, and she insisted on taking precedence at public ceremonies. Frederick had promised James that Elizabeth would be given precedence, but he later sought to revoke this pledge, citing superiority as her husband and causing his bride to assert bluntly that they “would set me in a lower rank than them that have gone before … [and] neither will I do it”.82

80Conclusion

The Stuarts effectively lost two children in the winter of 1612–13, and both losses occasioned the use of somatic display to make statements about dynastic power, legitimacy, and endurance. The season was ushered in with high levels of excitement, but the climate of joy and festivity gave way abruptly to grief, which was in turn subsumed into a moment of triumphant celebration. In staging two extraordinary public events—a royal funeral and a royal wedding—in quick succession, however, the royal family knitted the political together with the personal and pointedly revealed the power of the dressed body, the dynamism of signification, and the potency of material forms of remembrance. Henry’s death and Elizabeth’s marriage were enacted in the public arena, in private spaces, and via somatic and material display. Each event prompted sartorial choices by the Stuart family, their courtiers, and subjects, as well as a large contingent of European elites, to visualise overlapping categories of identity including allegiances, favour, networks of belonging, rank, wealth, and virtue. The examples discussed in this article demonstrate the political and intimately personal value of garments and accessories, making clear that what was signified was not fixed but changed in accordance with the individual wearer, the onlooker, the physical setting, and the socio-political context. As we have also seen, their meanings further multiplied as sartorial goods moved across transmedial space, from adorning the physical body to being detailed in a portrait, memorialised in a posthumous image, or treasured as a keepsake.

Acknowledgements

I am indebted to Edward Town for generously sharing his 2023 research findings that re-identified two portraits of Princess Elizabeth Stuart, and for allowing me to consult his work in advance of publication. My sincere thanks also to Elena Kagny-Loux for her insights into early modern fabrics and lace. Finally, I am deeply grateful to Tim McCall, whose discerning feedback greatly strengthened the article and whose encouragement has been invaluable.

About the author

-

Jemma Field is Associate Head of Research at the Yale Center for British Art. A cultural historian and museum leader, she specialises in early modern dress, gender, and identity politics. She has published in Costume, Northern Studies, The Court Historian, and Women’s History Review, and contributed multiple chapters in edited volumes. Her first monograph, Anna of Denmark: The Material and Visual Culture of the Stuart Courts, 1589–1619, was published by Manchester University Press in 2020. Her current research investigates the wardrobe of King Charles I of England, demonstrating how the dressed body legitimised political authority, articulated constructs of gender and sexuality, and expressed ambition and power.

Footnotes

-

1

Composite Manuscript, Cotton MS Titus C VII, fol. 121r, British Library (hereafter BL). ↩︎

-

2

The recognition that meaning is generated at the nexus between specific garments and accessories, a specific body, and a specific socio-political context is indebted to the number of historians who have taken materiality and embodiment seriously, most notably in the context of Renaissance Italy. See, for example, Timothy McCall, Brilliant Bodies: Fashioning Courtly Men in Early Renaissance Italy (University Park: Penn State University Press, 2022); Leah R. Clark, “Transient Possessions: Circulation, Replication, and Transmission of Gems and Jewels in Quattrocento Italy”, Journal of Early Modern History 15 (2011): 185–221; Ulinka Rublack, Dressing Up: Cultural Identity in Renaissance Europe (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010); Evelyn Welch, “New, Old and Second-Hand Culture: The Case of the Renaissance Sleeve”, in Revaluing Renaissance Art, ed. Gabriele Neher and Rupert Shepherd (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2000), 101–19; Susan Vincent, Dressing the Elite: Clothes in Early Modern England (Oxford: Berg, 2003). See also the recent collection of essays in Erin Griffey, ed., Sartorial Politics in Early Modern Europe: Fashioning Women (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2019). ↩︎

-

3

These portraits were re-identified by Edward Town in 2023. Discussion of these portraits will be included in a forthcoming exhibition about Elizabethan and Jacobean portraiture curated by Town at the Yale Center for British Art in New Haven, CT. My thanks to Edward Town for sharing his research with me in advance of the exhibition catalogue. ↩︎

-

4

See various entries listed under E in the index of Calendar of State Papers Relating to English Affairs in the Archives of Venice (hereafter CSPV), vol. 12, 1610–1613, ed. Horatio F. Brown (London, 1905), British History Online, https://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/venice/vol12. For records of the portraits see Edward Town, “A Biographical Dictionary of London Painters, 1547–1625”, Volume of the Walpole Society 76 (2014): 88; Karen Hearn, ed., Dynasties: Painting in Tudor and Jacobean England, 1530–1630 (London: Tate Publishing, 1995), 187–88. ↩︎

-

5

James Doelman, King James I and the Religious Culture of England (Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2000), 73–101; W. B. Patterson, King James VI and I and the Reunion of Christendom (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 294–97; Steve Murdoch, Britain, Denmark–Norway, and the House of Stuart, 1603–1660: A Diplomatic and Military Analysis (East Linton: Tuckwell Press, 2000), 30–36, 38–42; Alexia Grosjean, An Unofficial Alliance: Scotland and Sweden, 1569–1654 (Leiden: Brill, 2003), 37–44. ↩︎

-

6

Jemma Field, Anna of Denmark: The Material and Visual Culture of the Stuart Courts, 1589–1619 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2020), 193–94. ↩︎

-

7

Sara Smart and Mara R. Wade, “The Palatine Wedding of 1613: Protestant Alliance and Court Festival: An Introduction”, in The Palatine Wedding of 1613: Protestant Alliance and Court Festival, ed. Sara Smart and Mara R. Wade (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2013), 38–42; Revenues and disbursements of King James VI and I, 1603–17, BL, Add MS 58833, fol. 19v. ↩︎

-

8

CSPV, 12:278, no. 419 (20 January 1612). ↩︎

-

9

James’s own protracted marriage negotiations, for example, encompassed the question of two possible Oldenburg brides—sisters Elizabeth and Anna—together with the possible restitution of the Orkney and Shetland islands to Danish rule, the granting of Scottish shipping concessions through the Øresund strait, and the final dowry amount. Importantly, too, James studied portrait miniatures to help inform his decision, and a Scottish delegation was eventually sent to Denmark to conclude the marriage, with George Keith, Earl Marischal, serving as the proxy bridegroom in August 1589. David Stevenson, Scotland’s Last Royal Wedding (Edinburgh: John Donald, 1997), 22–23, 85–86; Miles Kerr-Peterson, A Protestant Lord in James VI’s Scotland: George Keith, Fifth Earl Marischal (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2019), 50; Paul Douglas Lockhart, Frederik II and the Protestant Cause: Denmark’s Role in the Wars of Religion, 1559–1596 (Leiden: Brill, 2004), 287–88, 311–12; Field, Anna of Denmark, 155–56. ↩︎

-

10

Nadine Akkerman, Elizabeth Stuart, Queen of Hearts (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2022), 62. ↩︎

-

11

John Nichols, The Progresses, Processions and Magnificent Festivities of King James the First, 4 vols. (New York: AMS Press, 1828), 2:464. ↩︎

-

12

CSVP, 12:444, no. 680 (9 November 1612). ↩︎

-

13

CSVP, 12:443, no. 680 (9 November 1612). ↩︎

-

14

Catharine MacLeod, “Facing Europe: The Portraiture of Anne of Denmark (1574–1619)”, in Telling Objects: Contextualizing the Role of the Consort in Early Modern Europe, ed. Jill Bepler and Svante Norrhem (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2018), 77. Extant examples are in the Royal Collection, London, and at Woburn Abbey, Bedfordshire. ↩︎

-

15

Hearn, Dynasties, 187; MacLeod, “Facing Europe”, 79. ↩︎

-

16

Valerie Cumming, “The Trousseau of Elizabeth Stuart”, in Collectanea Londiniensia: Studies in London Archaeology and History Presented to Ralph Merrifield, ed. Joanna Bird, Hugh Chapman, and John Clark (London: London and Middlesex Archaeological Society, 1978), 323. Elizabeth also took her wedding dress with her. ↩︎

-

17

Expenses of Princess Elizabeth: Lord Harrington’s account, 1613, The National Archives (hereafter TNA), Kew, E407/57/2. Although numbers are not given, the extremely high cost of these bills is indicative of large quantities such as that of Mr. Croshawe, the milliner, whose bill for “gloves, pins, garters, scarves, ribbons and sundry other things” totalled £333 15s. over a period of six months. ↩︎

-

18

Expenses of Princess Elizabeth, TNA, E407/57/2. ↩︎

-

19

On the role of the queen consort as an agent of transference and exchange, see R. Malcolm Smuts and Melinda J. Gough, “Queens and the International Transmission of Political Culture”, Court Historian 10 (2005): 1–13. More recently, a number of scholars have excavated the specific role that dress played in negotiating dynastic belonging, political allegiance, and within the bounds of royal marriage: see Jemma Field, “Female Dress”, in Early Modern Court Culture, ed. Erin Griffey (London: Routledge, 2022), 390–405; Sylvène Édouard, “The Hispanicization of Elisabeth de Valois at the Court of Philip II”, in Spanish Fashion at the Courts of Early Modern Europe, vol. 2, ed. Josè Luis Colomer and Amalia Descalzo (Madrid: Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica, 2014), 237–66; Maria Hayward, “Spanish Princess or Queen of England?”, in Spanish Fashion, ed. Colomer and Descalzo, 11–37; Laura Oliván Santaliestra, “Isabel of Borbón’s Sartorial Politics: From French Princess to Habsburg Regent”, in Early Modern Habsburg Women: Transnational Contexts, Cultural Conflicts, Dynastic Continuities, ed. Anne. J. Cruz and Maria Galli Stampino (Farnham: Ashgate, 2013), 225–43. ↩︎

-

20

Revenues and disbursements of King James VI and I, BL, Add MS 58833. ↩︎

-

21

Cumming, “Trousseau of Elizabeth Stuart”, 315. ↩︎

-

22

R. Malcolm Smuts, “Prince Henry and His World”, in Catharine MacLeod, with Timothy Wilks, Malcolm Smuts, and Rab MacGibbon, The Lost Prince: The Life and Death of Henry Stuart (London: National Portrait Gallery, 2012), 19. ↩︎

-

23

Henry’s painted image is sensitively examined by Catharine MacLeod, who consistently highlights the visual framing of the prince as “the embodiment of military hope”. See Catharine MacLeod, “Portraits of a ‘Most Hopeful Prince’”, in The Lost Prince, 33–42: quotation at p. 37 and catalogue entries on portraits of Henry dressed in armour at cat. nos. 26, 28–33, 44, 56, 82. ↩︎

-

24

The account book also includes twenty-one folios itemising necessary and extraordinary expenditure apparel post-Michaelmas 1612. Most of these entries are undated, with the last dated entry being 24 October 1612, but internal evidence shows that the accounts continue past Henry’s death as they contain orders for his embalming and effigy. Miscellaneous and Subsidiary, 1570–1836, TNA, AO3/909/2, fols. 36r–46v. The declared account is Masters and Keepers of the Great Wardrobe, Sir David Murrye (Wardrobe of Henry Prince of Wales), 1610–12, TNA, E351/3085. ↩︎

-

25

Maria Hayward, Stuart Style: Monarchy, Dress and the Scottish Male Elite (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2020), 68. The two tailors are listed in Prince Henry’s 1607 wardrobe accounts (Lord Steward’s Department: Papers of Sir Julius Caesar, 1603–25, TNA, LS13/280), but by 1611 only Black is named (Robes: Accounts [Prince of Wales], Michaelmas to October, 1611–12, TNA, AO3/909/2). However, note that Alexander Wilson was later recorded as yeoman of the robes to Prince Charles (Household regulations: Prince Charles, 1612, TNA, LC5/179, p. 10). ↩︎

-

26

Robes: Accounts, TNA, AO3/909/2, fols. 15v–20r. Of the thirty-three cloaks listed in the accounts where the lining fabric is included, fifteen were lined with velvet and fifteen with shag; the remaining three cloaks were lined with taffeta. ↩︎

-

27

Robes: Accounts, TNA, AO3/909/2, running from September 1611 through to September 1612. ↩︎

-

28

McCall makes this point eloquently about fifteenth-century Italian princes (Brilliant Bodies, 5): “Galeazzo [Maria Sforza] understood that he was always on display, watched and judged by peers and courtiers and at times by large public gatherings … throughout his life, moreover, the lord was clearly aware of subjects’ and courtiers’ expectations of signorial beauty and body type”. ↩︎

-

29

Robes: Accounts, TNA, AO3/909/2, fol. 7r (11 January 1612). ↩︎

-

30

Robes: Accounts, TNA, AO3/909/2, fols. 36r–40v. ↩︎

-

31

Robes: Accounts, TNA, AO3/909/2, fol. 40r. ↩︎

-

32

Robes: Accounts, TNA, AO3/909/2, fols. 40v–41r; quotation at fol. 40v. ↩︎

-

33

Robes: Accounts, TNA, AO3/909/2, fol. 40r. ↩︎

-

34

McCall, Brilliant Bodies, 33–39; Lisa Monnas, Renaissance Velvets (London: V&A Publishing, 2012), 18–20. ↩︎

-

35

Robes: Accounts, TNA, AO3/909/2, fol. 40v. ↩︎

-

36

Susan North, “Indian Gowns and Banyans—New Evidence and Perspectives”, Costume 51, no. 4 (2020): 32–33. ↩︎

-

37

Robes: Accounts, TNA, AO3/909/2, fol. 38r (24 October 1612). ↩︎

-

38

Hayward, Stuart Style, 89. ↩︎

-

39

See also the large quantity of annual summer allocations of green clothing that King James issued to his “huntismen” and the pages who accompanied him on the hunt in both Scotland and England. Exchequer Accounts and Vouchers: Alexander, Master of Elphinstone, Treasurer, 1600–1, National Records of Scotland (NRS), E21/74, fols. 56, 57; Exchequer Accounts and Vouchers: Sir Robert Melville of Murdocairnie, Treasurer Depute, 1590–92, NRS, E21/68, fol. 170; Great Wardrobe: Miscellaneous Records, 1603–30, TNA, LC5/50. ↩︎

-

40

For Charles see Hayward, Stuart Style, 89; for Henry see various entries in Robes: Accounts, TNA, AO3/909/2. ↩︎

-

41

See William Larkin’s portrait of Richard Sackville, earl of Dorset (National Trust, Kenwood House), which commemorates the outfit the earl wore to the Palatine–Stuart wedding, together with the inventory that records these clothes in Peter MacTaggart and Ann MacTaggart, “The Rich Wearing Apparel of Richard, 3rd Earl of Dorset”, Costume 14 (1980): 45, 49. See too the male figures recorded in the 1613 etching by Abraham Hogenberg, Procession for the Wedding of Princess Elizabeth Stuart and Frederick V, Elector Palatine, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (53.601.152). Visual examples of Stuart elites wearing knee-length breeches with their ceremonial robes include those of King James (National Portrait Gallery, London, NPG 109; Royal Collection, London, RCIN 404446); Prince Henry (National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh, PGL 240; Magdalen College, University of Oxford, P0458); Ludovic Stuart, duke of Richmond and Lennox (National Portrait Gallery, London, NPG 5297). This style is also clearly seen in the engraving of Elizabeth’s marriage procession, circa 1613, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (53.601.152). ↩︎

-

42

Nichols, Progresses, 2:478; The Letters of John Chamberlain, ed. Norman Egbert McClure, 2 vols. (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1939), 1:384. ↩︎

-

43

Nichols, Progresses, 2:481, 485. ↩︎

-

44

MacLeod, The Lost Prince, 161, 170–73; Elizabeth Goldring, “‘So Iust a Sorrow So Well Expressed’: Henry, Prince of Wales and the Art of Commemoration”, in Prince Henry Revived: Image and Exemplarity in Early Modern England, ed. Timothy Wilks (Southampton: Southampton Solent University with Paul Holberton, 2020), 280–300. ↩︎

-

45

CSPV, 12:449, no. 692 (23 November 1612); CSPV, 12:452, no. 698 (30 November 1612). ↩︎

-

46

Exchequer, Pipe Office: Declared Accounts, TNA, E351/3145. ↩︎

-

47

In all, the funeral cost £16,016 0s. Revenues and disbursements of King James VI and I, BL, Add MS 58833. Note, however, that this summary account conflates all textile costs under the heading of “blacks”, whereas a significant portion of this was spent on other textiles, including purple and crimson velvet, cloth of gold, and cloth of silver. See Exchequer, Pipe Office, TNA, E351/3145, and individual bills in Miscellaneous and Subsidiary, 1570–1836, TNA, AO3/1276. ↩︎

-

48

Robes: Accounts, TNA, AO3/909/2, fols. 38v, 44r. Henry Green was paid £16 13s. 4d. for entombing Henry’s body, heart, and bowels in lead. Exchequer, Pipe Office, TNA, E351/3145; Miscellaneous and Subsidiary, TNA, AO3/1276, loose bills. Embalming the body was a rite observed in accordance with elite status, and the same was to be observed for his mother, Queen Anna, in 1619. While it allowed for preservation over the course of the time required for heraldic funerals, it was also observed for high-ranking people who were buried on the same day as their death. Jemma Field, “‘Orderinge Things Accordinge to His Majesties Comaundment’: The Funeral of the Stuart Queen Consort Anna of Denmark”, Women’s History Review 30, no. 5 (2021): 841. ↩︎

-

49

Robes: Accounts, TNA, AO3/909/2, fols. 38v, 44v, 46v; Miscellaneous and Subsidiary, TNA, AO3/1276, loose bill; Masters and Keepers of the Great Wardrobe, TNA, E351/3085. On royal effigies see, among other sources, Julien Litten, “The Funeral Effigy: Its Function and Purpose”, in The Funeral Effigies of Westminster Abbey, ed. Anthony Harvey and Richard Mortimer (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 1994), 3–19. ↩︎

-

50

Letter to Lady Carleton, London, 19 December 1612, Secretaries of State: State Papers Domestic, James I, TNA, SP14/71, fol. 130r. For Prince Henry’s funeral see, for example, Gregory McNamara, “‘Grief Was as Clothes to Their Backs’: Prince Henry’s Funeral Viewed from the Wardrobe”, in Prince Henry Revived, ed. Wilks, 259–79; Jennifer Woodward, The Theatre of Death: The Ritual Management of Royal Funerals in Renaissance England, 1570–1625 (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 1997), 148–65. ↩︎

-

51

The Royal Correspondence of King James I of England (and VI of Scotland) to His Royal Brother-in-Law, King Christian IV of Denmark, 1603–1625, ed. R. M. Meldrum (Hassocks: Harvester Press, 1977), 141 (7 November 1612). ↩︎

-

52

Catriona Murray, Imaging Stuart Family Politics: Dynastic Crisis and Continuity (New York: Routledge, 2017), 74–77. ↩︎

-

53

CSPV, 12:472, no. 732 (5 January 1613). ↩︎

-

54

Letter to Lady Carleton, London, 19 December 1612, TNA, SP14/71, fol. 128r. ↩︎

-

55

CSPV, 12:472, no. 732 (5 January 1613). ↩︎

-

56

Expenses of Princess Elizabeth, TNA, E407/57/2. ↩︎

-

57

My thanks to Elena Kanagy-Loux for discussing the fabric of Elizabeth’s dress and identifying the type of lace depicted in the portrait. ↩︎

-

58

Elizabeth Goldring, Nicholas Hilliard: Life of an Artist (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2019), 271. My thanks to Ed Town for discussing the connection between the two images with me. ↩︎

-

59

See Catriona Murray, “Distant Relations: The Palatine Family, Propaganda, and Print in Early Stuart Britain”, British Art Studies 29 (December 2025), DOI:10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-29/cmurray. ↩︎

-

60

MacLeod, The Lost Prince, 169 (cat. no. 77). ↩︎

-

61

It is also worth considering that these portraits allowed Elizabeth to retain her currency within the body politic, to leave her mark on the collective memory at a moment when her physical body left the multiple Stuart kingdoms. ↩︎

-

62

Consider Charles’s touching letter to Henry, in which he wrote: “I will give anie thing that I have to yow, both horss, and my books, and my pieces and my cross bowes, or anie thing that you would haive. Good brother, loove me; and I shall ever loove and serve yow”. Henry Ellis, Original Letters, Illustrative of English History, 3 vols. (London, 1824), 3:92 (letter no. 251); see also p. 94. He also brought Henry his favoured horse statuette as a source of comfort during his last visit. MacLeod, The Lost Prince, 160 (cat. no. 53). ↩︎

-

63

Murray, Imaging Stuart Family Politics, 84. The armour garniture is now in the Royal Collection, London (RCIN 72831). ↩︎

-

64

Anna Reynolds, In Fine Style: The Art of Tudor and Stuart Fashion (London: Royal Collection Trust, 2013), 230–31. ↩︎

-

65

Calendar of State Papers Domestic: James I, 1611–18, ed. Mary Anne Everett Green (London, 1858), 74:189 (3 July 1613), British History Online, https://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/domestic/jas1/1611-18. Black continued to serve Charles well into his own reign. Roy Strong, “Charles I’s Clothes for the Years 1633 to 1635”, Costume 14, no. 1 (1980): 73. ↩︎

-

66

Expenses of Princess Elizabeth, TNA, E407/57/2. The other rewards that Elizabeth disbursed for deliveries in this set of accounts amounted to five, ten, twenty (£1), or forty shillings (£2). ↩︎

-

67

Robes: Accounts, TNA, AO3/909/2, fol. 21r. ↩︎

-

68

Robes: Accounts, TNA, AO3/909/2, fol. 38r (24 October 1612). ↩︎

-

69

Miles Lambert, “Death and Memory: Clothing Bequest in English Wills, 1650–1830”, Costume 48, no. 1 (2014): 51. ↩︎

-

70

Elizabeth Hallam and Jenny Hockey, Death, Memory and Material Culture (Oxford: Berg, 2001), 164. ↩︎

-

71

Clark, “Transient Possessions”, 186, 188. ↩︎

-

72

Lambert, “Death and Memory”, 55. ↩︎

-

73

CSPV, 12:473, no. 734 (11 January 1613); Letters of John Chamberlain, 1:399. ↩︎

-

74

Unpublished letter from Isaac Wake to Dudley Carleton [English ambassador to Venice], 31 December 1612, TNA, SP 105/106, quoted in Ross W. Duffin, “Voices and Viols, Bibles and Bindings: The Origins of the Blossom Partbooks”, Early Music History 33 (2014): 83; CSPV, 12:472, no. 734 (5 January 1613). ↩︎

-

75

CSPV, 12:493, no. 767 (16 February 1613). ↩︎

-

76

CSPV, 12:498, no. 775 (1 March 1613). ↩︎

-

77

Mercure François (1613), seconde continuation, 71, quoted in Duffin, “Voices and Viols”, 84. ↩︎

-

78

Cumming, “Trousseau of Elizabeth Stuart”, 323. ↩︎

-

79

Frederic Madden, “Warrant of King James the First to the Great Wardrobe for Apparel etc. for the Marriage of the Princess Elizabeth”, Archaeologia 26 (1836): 387–88. ↩︎

-

80

Akkerman, Elizabeth Stuart, 137, 140–41. ↩︎

-

81

See Field, “Female Dress”; Édouard, “The Hispanicization of Elisabeth de Valois”; Hayward, “Spanish Princess or Queen of England?”; Santaliestra, “Isabel of Borbón’s Sartorial Politics”. ↩︎

-

82

Rebecca Calcagno, “A Matter of Precedence: Britain, Germany, and the Palatine Match”, in The Palatine Wedding of 1613: Protestant Alliance and Court Festival, ed. Sara Smart and Mara R. Wade (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2013), 258. ↩︎

Bibliography

Manuscript Sources

Composite Manuscript. Cotton MS Titus C VII. British Library, London.

Exchequer Accounts and Vouchers: Alexander, Master of Elphinstone, Treasurer, 1600–1. E21/74. National Records of Scotland, Edinburgh.

Exchequer Accounts and Vouchers: Sir Robert Melville of Murdocairnie, Treasurer Depute, 1590–92. E21/68. National Records of Scotland, Edinburgh.

Exchequer, Pipe Office: Declared Accounts. E351/3145. The National Archives, Kew.

Expenses of Princess Elizabeth: Lord Harrington’s account, 1613. E407/57/2. The National Archives, Kew.

Great Wardrobe: Miscellaneous Records, 1603–30. LC5/50. The National Archives, Kew.

Household regulations: Prince Charles, c 1612. LC5/179. The National Archives, Kew.

Lord Steward’s Department: Papers of Sir Julius Caesar, 1603–25. LS13/280. The National Archives, Kew.

Masters and Keepers of the Great Wardrobe, Sir David Murrye (Wardrobe of Henry Prince of Wales), 1610–12. E351/3085. The National Archives, Kew.

Miscellaneous and Subsidiary, 1570–1836. AO3/1276. The National Archives, Kew.

Revenues and disbursements of King James VI and I, 1603–17of King James VI and I, 1603–17. Add MS 58833. British Library, London.

Robes: Accounts (Prince of Wales), Michaelmas to October, 1611–12. AO3/909/2. The National Archives, Kew.

Secretaries of State: State Papers Domestic, James I. SP14/71. The National Archives, Kew.

Printed Sources

Akkerman, Nadine. Elizabeth Stuart, Queen of Hearts. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2022.

Calcagno, Rebecca. “A Matter of Precedence: Britain, Germany, and the Palatine Match”. In The Palatine Wedding of 1613: Protestant Alliance and Court Festival, edited by Sara Smart and Mara R. Wade, 243–66. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2013.

Calendar of State Papers Domestic: James I, 1611–18. Vol. 74. Edited by Mary Anne Everett Green London, 1858. British History Online, https://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/domestic/jas1/1611-18.

Calendar of State Papers Relating to English Affairs in the Archives of Venice. Vol. 12, 1610–1613. Edited by Horatio F. Brown. London, 1905. British History Online, https://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/venice/vol12.

Chamberlain, John. The Letters of John Chamberlain. 2 vols. Edited by Norman Egbert McClure. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1939.

Clark, Leah R. “Transient Possessions: Circulation, Replication, and Transmission of Gems and Jewels in Quattrocento Italy”. Journal of Early Modern History 15 (2011): 185–221.

Cumming, Valerie. “The Trousseau of Elizabeth Stuart”. In Collectanea Londiniensia: Studies in London Archaeology and History Presented to Ralph Merrifield, edited by Joanna Bird, Hugh Chapman, and John Clark, 315–28. London: London and Middlesex Archaeological Society, 1978.

Doelman, James. King James I and the Religious Culture of England. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2000.

Duffin, Ross W. “Voices and Viols, Bibles and Bindings: The Origins of the Blossom Partbooks”. Early Music History 33 (2014): 61–108.

Édouard, Sylvène. “The Hispanicization of Elisabeth de Valois at the Court of Philip II”. In Spanish Fashion at the Courts of Early Modern Europe, vol. 2, edited by Josè Luis Colomer and Amalia Descalzo, 237–66. Madrid: Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica, 2014.

Ellis, Henry. Original Letters, Illustrative of English History. 3 vols. London: printed for Harding, Triphook, and Lepard, 1824.

Field, Jemma. Anna of Denmark: The Material and Visual Culture of the Stuart Courts, 1589–1619. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2020.

Field, Jemma. “Female Dress”. In Early Modern Court Culture, edited by Erin Griffey, 390–405. London: Routledge, 2022.

Field, Jemma. “‘Orderinge Things Accordinge to His Majesties Comaundment’: The Funeral of the Stuart Queen Consort Anna of Denmark”. Women’s History Review 30, no. 5 (2021): 835–55.

Goldring, Elizabeth. Nicholas Hilliard: Life of an Artist. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2019.

Goldring, Elizabeth. “‘So Iust a Sorrow So Well Expressed’: Henry, Prince of Wales and the Art of Commemoration”. In Prince Henry Revived: Image and Exemplarity in Early Modern England, edited by Timothy Wilks, 280–300. Southampton: Southampton Solent University with Paul Holberton, 2020.

Griffey, Erin, ed. Sartorial Politics in Early Modern Europe: Fashioning Women. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2019.

Grosjean, Alexia. An Unofficial Alliance: Scotland and Sweden, 1569–1654. Leiden: Brill, 2003.

Hallam, Elizabeth, and Jenny Hockey. Death, Memory and Material Culture. Oxford: Berg, 2001.

Hayward, Maria. “Spanish Princess or Queen of England?”. In Spanish Fashion at the Courts of Early Modern Europe, vol. 2, edited by José Luis Colomer and Amalia Descalzo, 11–37. Madrid: Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica, 2014.

Hayward, Maria. Stuart Style: Monarchy, Dress and the Scottish Male Elite. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2020.

Hearn, Karen, ed. Dynasties: Painting in Tudor and Jacobean England, 1530–1630. London: Tate Publishing, 1995.

James VI and I. The Royal Correspondence of King James I of England (and VI of Scotland) to His Royal Brother-in-Law, King Christian IV of Denmark, 1603–1625. Edited by R. M. Meldrum. Hassocks: Harvester Press, 1977.

Kerr-Peterson, Miles. A Protestant Lord in James VI’s Scotland: George Keith, Fifth Earl Marischal. Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2019.

Lambert, Miles. “Death and Memory: Clothing Bequest in English Wills, 1650–1830”. Costume 48, no. 1 (2014): 46–59.

Litten, Julien. “The Funeral Effigy: Its Function and Purpose”. In The Funeral Effigies of Westminster Abbey, edited by Anthony Harvey and Richard Mortimer, 3–19. Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 1994.

Lockhart, Paul Douglas. Frederik II and the Protestant Cause: Denmark’s Role in the Wars of Religion, 1559–1596. Leiden: Brill, 2004.

MacLeod, Catharine. “Facing Europe: The Portraiture of Anne of Denmark (1574–1619)”. In Telling Objects: Contextualizing the Role of the Consort in Early Modern Europe, edited by Jill Bepler and Svante Norrhem, 63–86. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2018.

MacLeod, Catharine. “Portraits of a ‘Most Hopeful Prince’”. In The Lost Prince: The Life and Death of Henry Stuart. Catharine MacLeod with Timothy Wilks, R. Malcolm Smuts, and Rab MacGibbon, 33–42. London: National Portrait Gallery, 2012.

MacTaggart, Peter, and Ann MacTaggart. “The Rich Wearing Apparel of Richard, 3rd Earl of Dorset”. Costume 14 (1980): 41–55.

Madden, Frederic. “Warrant of King James the First to the Great Wardrobe for Apparel etc. for the Marriage of the Princess Elizabeth”. Archaeologia 26 (1836): 380–94.

McCall, Timothy. Brilliant Bodies: Fashioning Courtly Men in Early Renaissance Italy. University Park: Penn State University Press, 2022.

McNamara, Gregory. “‘Grief Was as Clothes to Their Backs’: Prince Henry’s Funeral Viewed from the Wardrobe”. In Prince Henry Revived: Image and Exemplarity in Early Modern England, edited by Timothy Wilks, 259–79. Southampton: Southampton Solent University with Paul Holberton, 2020.

Monnas, Lisa. Renaissance Velvets. London: V&A Publishing, 2012.

Murdoch, Steve. Britain, Denmark–Norway, and the House of Stuart, 1603–1660: A Diplomatic and Military Analysis. East Linton: Tuckwell Press, 2000.

Murray, Catriona. Imaging Stuart Family Politics: Dynastic Crisis and Continuity. New York: Routledge, 2017.

Nichols, John. The Progresses, Processions and Magnificent Festivities of King James the First. 4 vols. New York: AMS Press, 1828.

North, Susan. “Indian Gowns and Banyans—New Evidence and Perspectives”. Costume 51, no. 4 (2020): 30–55.

Patterson, W. B. King James VI and I and the Reunion of Christendom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

Reynolds, Anna. In Fine Style: The Art of Tudor and Stuart Fashion. London: Royal Collection Trust, 2013.

Rublack, Ulinka. Dressing Up: Cultural Identity in Renaissance Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Santaliestra, Laura Oliván. “Isabel of Borbón’s Sartorial Politics: From French Princess to Habsburg Regent”. In Early Modern Habsburg Women: Transnational Contexts, Cultural Conflicts, Dynastic Continuities, edited by Anne. J. Cruz and Maria Galli Stampino, 225–43. Farnham: Ashgate, 2013.

Smart, Sara, and Mara R. Wade. “The Palatine Wedding of 1613: Protestant Alliance and Court Festival: An Introduction”. In The Palatine Wedding of 1613: Protestant Alliance and Court Festival, edited by Sara Smart and Mara R. Wade, 13–60. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2013.

Smuts, R. Malcolm. “Prince Henry and His World”. In Catharine MacLeod, with Timothy Wilks, R. Malcolm Smuts, and Rab MacGibbon, The Lost Prince: The Life and Death of Henry Stuart, 19–32. London: National Portrait Gallery, 2012.

Smuts, R. Malcolm, and Melinda J. Gough. “Queens and the International Transmission of Political Culture”. Court Historian 10 (2005): 1–13.

Stevenson, David. Scotland's Last Royal Wedding. Edinburgh: John Donald, 1997.

Strong, Roy. “Charles I’s Clothes for the Years 1633 to 1635”. Costume 14, no. 1 (1980): 73–89.

Town, Edward. “A Biographical Dictionary of London Painters, 1547–1625”. Volume of the Walpole Society 76 (2014).

Vincent, Susan. Dressing the Elite: Clothes in Early Modern England. Oxford: Berg, 2003.

Welch, Evelyn. “New, Old and Second-Hand Culture: The Case of the Renaissance Sleeve”. In Revaluing Renaissance Art, edited by Gabriele Neher and Rupert Shepherd, 101–19. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2000.

Woodward, Jennifer. The Theatre of Death: The Ritual Management of Royal Funerals in Renaissance England, 1570–1625. Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 1997.

Imprint

| Author | |

|---|---|

| Date | 18 December 2025 |

| Category | Article |

| Review status | Peer Reviewed (Double Blind) |

| License | Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) |

| Downloads | PDF format |

| Article DOI | https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-29/jfield |

| Cite as | Field, Jemma. “Dressing the Stuarts: The Sartorial Politics of Mourning and Matrimony, 1612–1613.” In British Art Studies: Reframing King James VI and I (Edited by Kate Anderson, Jemma Field, and Catriona Murray.). London and New Haven: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art and Yale Center for British Art, 2025. https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-29/jfield. |