Painting the Queen Black

Painting the Queen Black: Paint, Portraiture, and Seeing Queen Anna as a Daughter of Niger

By Mia L. Bagneris

Abstract

In The Masque of Blackness, written by Ben Jonson and performed on Twelfth Night in 1605, Anna of Denmark and eleven women of the court employed a novel mechanism of racial impersonation for a royal masque, performing not in black masks but with their faces and bodies painted black. This article contends that Inigo Jones’s A Daughter of Niger, conventionally regarded as a generic costume design for the performance, is actually a portrait of Anna in blackface. Within the context of early modern ideas about Blackness and beauty, it attends to the dual material implications of painting the queen black—both her actual body during the masque’s performance and its enduring graphic representation in Jones’s picture.

Prelude to a Spectacle

Sometime during the weeks leading up to the Christmas season in 1604, King James VI and I engaged in a tense exchange with his Privy Council regarding the court’s plans for a holiday masque. Although James had initially proposed an elaborate production, perhaps with “fine ballets or dances” that featured Anna of Denmark and ladies of the court, he apparently balked at the £4,000 price tag projected by the council. Hoping to reduce the expense, he immediately suggested potential economising measures: perhaps the queen could finance the masque from her own coffers, with the court ladies contributing funds for their own costumes, or they could all just enjoy more modest entertainments instead? However, the council, unmoved by James’s concerns for frugality, essentially countered that the king just needed to man up and “resolve beforehand that the expense must be your own”. The council admonished that cancelling the masque simply for “the saving of £4,000 would be more pernicious than the expense of ten times the value”. Indeed, they implied that James stood to lose far more than a bit of money, for his personal honour and that of his kingdom were at stake. If foreign powers should learn that a court fete had been cancelled merely because of the cost, the council cautioned, “the judgment that will follow will neither be safe nor honourable”.1

1The holiday entertainments eventually proceeded as scheduled, but if the Privy Council had been counting on “safe and honourable” amusements to shore up James’s reputation, they must have been gravely disappointed by the unexpected drama and controversy that followed instead. The council had hoped that, by staging the extravagant show at court as planned, James could avoid tarnishing his crown with rumours of financial insolvency or otherwise imperilled power and that going through with the production would allow the king to save face. It did not occur to them, however, that Anna, who had been charged with planning the masque in which she and her ladies would perform, might literally blacken hers (fig. 1).

Meditations on The Masque of Blackness: Black Paint in Performance and Portraiture

Anna of Denmark was a legendary beauty whom James had reportedly determined to marry immediately on viewing her portrait. Flaxen haired, azure eyed, and ivory skinned, she embodied emerging Renaissance ideals of feminine pulchritude that the literary scholar Bernadette Andrea, building on the germinal work of Kim F. Hall in Things of Darkness, observes, “collapsed ‘beauty’ into ‘fairness’ and ‘fairness’ into ‘whiteness’” (fig. 2).2 However, Anna, perhaps motivated by a desire to create a striking contrast between herself and the character she was to portray in that year’s Twelfth Night entertainments, commissioned Ben Jonson to write a masque of racial transformation in which she and the chosen ladies of her court would appear as “Black-mores at first”.3 The resulting Masque of Blackness marked the beginning of a notoriously contentious, decades-long collaboration between Jonson as the dramatist responsible for developing the script and Inigo Jones as the designer responsible for what Jonson rather condescendingly referred to as “the bodily part”—the visual elements that brought Jonson’s text to life, including elaborate and often mechanised stage sets, astounding theatrical effects, and sumptuous costumes.4

2

Scholars of early modern Britain have long studied the language and plot of The Masque of Blackness as a dramatic text. They have also analysed its performance as a historical event and, especially since the 1990s, brought increasing critical attention to the masque as a comprehensive production by interpreting the implications of the work as a live, embodied performance.5 Additionally, the research of Stephen Orgel and Roy Strong, culminating in the mammoth two-volume opus Inigo Jones: The Theatre of the Stuart Court, including the Complete Designs for Productions at Court for the Most Part in the Collection of the Duke of Devonshire, Together with Their Texts and Historical Documentation, published in 1973, directed attention to Inigo Jones’s masque designs as a body of work for the first time and remains the most comprehensive survey and assessment of Jones’s theatre designs.6 Aiming to reproduce each of the nearly five hundred known designs created by Inigo Jones for Jacobean and Carolinian court masques—most of which remain in the private collection of the duke and duchess of Devonshire at Chatsworth House and are not generally accessible—the project made a significant contribution by assembling and documenting the visual and material culture of these dramatic productions. Orgel and Strong’s scholarship therefore supported a better appreciation of the masques, which would have been primarily spectacular experiences rather than textual ones, in terms of both their visual display and their theatrical impact. However, while this work introduced the visual culture of the masques into the scholarly discourse, it did so primarily as part of a documentary rather than a critical interpretative project. Consequently, the costume sketches, set designs, and other visual works Jones created in conjunction with royal masques have been understood primarily as material artefacts of the productions or valued for their relationship to the famed “architect” Jones. They remain surprisingly understudied as significant visual culture objects meriting critical analysis themselves. Accordingly, scholars have overlooked the remarkable design made by Jones for The Masque of Blackness typically identified as A Daughter of Niger. The striking watercolour sketch of an imposing, spectacularly attired, and apparently dark-skinned woman—one of fewer than ten masque designs that the artist chose to execute in colour—has been reproduced as a general illustration for The Masque of Blackness and understood as a specific costume design representing one of the twelve daughters of Niger, the featured group of characters around whom the plot centres. It has yet to receive any independent critical visual analysis or art historical interpretation. Taking an unessayed approach, this article proposes a provocative new way of seeing and understanding Jones’s picture not simply as a representation of a daughter of Niger, that is, as a generic costume design meant to show the identical ensembles worn by the twelve court ladies who assumed the roles in the performance of The Masque of Blackness, but as a specific portrait—in blackface—of the singular Queen Anna.7

5Bringing together and building upon previous scholarship, I initially address the implications of the novel mechanism of racial masquerade deployed in The Masque of Blackness, that is, the application of black paint to the skin in lieu of more conventional prostheses of racial masquerade such as masks, gloves, and stockings. Although the practice of using cosmetic methods to represent racial Otherness had been well established for more than two decades in professional English theatre, the use of black paint as a mechanism of racial impersonation in The Masque of Blackness was still a daring innovation with unique implications within the context of the royal masque.8 Having established this context, I then undertake a closely observed visual analysis of Jones’s sketch to buttress the reading of A Daughter of Niger as a portrait likeness of Anna. The analysis brings into relief the material tensions Jones’s picture struggles to resolve that were not present in the live performance, and highlights the challenge that the artist confronted: how to clearly distinguish—in a two-dimensional rendering in paint on paper—a queen painted black from a queen painted as Black. I contend that A Daughter of Niger materially manifests the doubly fraught implications of Anna’s painted body—both her actual physical body in the masque’s performance and its graphic representation in the costume design. Jones’s portrait of Anna as a daughter of Niger labours to define the liminal boundary between paint and skin inherent in both the performance and the picture in ways that prompt a consideration of how both might potentially contribute to our understanding of the early modern foundation and origins of anti-Blackness.

8Meet the Dark and Lovely Daughters of Niger: Staging the Poetics and Politics of Paint

As Andrea observes, traditional scholarship on Jacobean court masques (and essentially anything written before the influence of second-wave feminism) “treated the question of Queen Anne’s authoritative role in the production of the early masques less as a point of contestation than as a possibility too ridiculous to pursue”.9 In the last several decades, however, Andrea and others, including Hardin Aasand, Leeds Barroll, Dympna Callaghan, Sujata Iyengar, Ann Clive Kelly, Barbara Kiefer Lewalski, Clare McManus, Ann Pleiss Morris, Andrea Ria Stevens, Sara B. T. Thiel, and Virginia Mason Vaughan have increasingly taken up the supposedly foolhardy pursuit. Complicating—and at times directly challenging—earlier interpretations of the queen’s role in these elaborate productions, they have examined how Anna, who made artistic patronage a defining feature of her consortship, strategically appropriated the royal masque to her own ends.10 Using the court masque as a platform to stage her identity and assert her power, Anna marked out a public role for herself through which she managed, though not completely or unproblematically, to contest her husband’s authority, the limitations of her position as queen, and prevailing gender norms.

9The Masque of Blackness, the first of what Jonson dubbed “The Queen’s Masques”, featured Anna and her ladies as star players although, in keeping with convention, silent ones because female participants in court masques did not have speaking parts.11 Constraints of space preclude a summary and analysis of Jonson’s complicated and convoluted text that does justice to its language and plot. However, because elements of the masque’s plot and language, especially regarding colour and form and their relationship to beauty, inform my interpretation of Jones’s watercolour sketch of A Daughter of Niger, a general overview of the text may be helpful. As the masque opens, the river god Niger—whom Jonson describes as having the “forme and colour of an Æthiope”—beseeches his father, the sea god Oceanus, on behalf of his twelve dark and lovely daughters whose deep complexions come as a gift from the “glorious Sunne” and signify “Signes of his [the Sun’s] feruent’st Loue [ferventest love]”. Although “Faire Niger”, as Jonson calls the dutiful father, declares his daughters’ exquisiteness and asserts that “in their black, the perfectst beauty growes”, he reports, in exasperation, that the women themselves have become unconvinced of their own loveliness.

11Niger attributes this turn of events to the recent spate of poets’ paeans to pale pulchritude, lamenting that his daughters’ doubts have emerged ever

… since the fabulous voices of some few

Poore brain-sicke men, stil’d Poets, here with you,

Haue [have], with such enuy [envy] of their graces, sung

The painted Beauties, other Empires sprung;

Letting their loose, and winged fictions fly.

The distraught father adds that, although once “About the Globe, the Æthiopes were as faire, / As other Dames”, his daughters have been driven to depression over their dark complexions and are now not only dark in skin colour but also “blacke, with blacke dispaire”. Seeking to restore his daughters’ happiness, Niger resolves to help them in their mission to change their complexions.

Following the advice of an oracle that appears to the melanated maidens in a stream, father and daughters embark on a quest to find a temperate land ending in “tania”, whose pleasant climate will be gentler to their complexions. After they find no luck in “Blacke Mauritania”, “Swarth Lusitania”, or “Rich Aquitania”, the moon goddess Æthiopia—a vision in flowing garments of white and silver—appears dramatically before them. Invoking James’s proclamation of the kingdom of Great Britain on his ascent to the throne, she dispatches them to the island “With that great name Britania … / … (whose new name makes all tongues sing) / … Whose Beames shine day, and night, and are of force / To blanch an Æthiope, and reuiue a Cor’s [revive a corpse]”.12

12While Anna had apparently approached Ben Jonson with her idea for the masque’s ostensibly shocking gimmick for the ladies to impersonate Niger’s brilliantly beautiful Black daughters, Jonson managed to take all the credit for the work’s successes but none of the blame for its less than favourable reception among the British members of court. Writing of her request in his introduction to the text, he dismisses Anna’s agency while taking pride in his own genius ability to transform the queen’s frivolous demands into great art: “Hence (because it was her Maiesties will, to haue them Black-mores at first) the inuention was deriued by me, & presented thus”.13 As Andrea observes, with this statement “Jonson literally brackets the Queen’s command … [and] frames her stated intention with the assertion that his art gave form to her caprice”.14

13But what exactly was the substance of the queen’s “caprice”? Given the prevalence of performances of Blackness—both by actual Black people and through impersonations of them—in the Tudor and Jacobean courts, it is doubtful whether a little racial masquerade of the conventional sort would have raised many eyebrows or be registered as a frivolous whim. By 1601, as Andrea has noted, people of African descent—and Black women, in particular—already had an established presence, albeit a marginalised one, in the British royal court. For example, Black ladies-in-waiting served at the court of James IV of Scotland, and Black dancers performed at the court of Elizabeth I. Some occupied positions of relative privilege and renown, albeit ones we would today identify as problematically rooted in anti-Blackness. For example, Elen More, maidservant to Mary Tudor, was deemed the “Black Queen of Beauty” and presided over court festivities in 1507 and 1508. In an earlier set of these amusements, More, sumptuously dressed and accompanied by her own attendants, she served as the “chivalric prize” in the Tournament of the Black Knight and the Black Lady, with the winner “rewarded by the black lady’s kiss” and losers demeaned by having to “cum behind and kis her hippis”.15 Indeed, James and Anna’s court festivities frequently featured Black skin or the impersonation of it. In a now infamous episode at the couple’s Norwegian wedding celebration in 1579, for example, four young Black men preceded the royal carriage, dancing naked in the snow in the queen’s honour and for the crowd’s amusement. The performance cost them their lives as all four later succumbed to the effects of the cold and died.16 Similarly, the 1590 welcoming festivities held on the queen’s arrival in Edinburgh included a parade of “three score young men of the town, [dressed] lyke Moores, and clothed in cloth of silver, with chaines about their neckes, and bracelets about their armes, set with diamonds and other precious stones”.17 The idea of Blackness, whether actual or impersonated, had therefore been a hallmark of the royal couple’s celebrations from the very start.

15Underscoring both the novel means of racial impersonation in the performance of The Masque of Blackness and the source of the directive that had inspired it, Vaughan asserts that “what is radical in Queen Anne’s request is her desire to use black pigment”.18 While some scholars have argued that there is insufficient evidence to support crediting Anna with the choice of black paint to accomplish her request for a masque of racial impersonation, there is more than enough circumstantial evidence to warrant considering it as a likely possibility.19 However, a narrow focus on the question of who should be credited with this choice inevitably diverts attention away from how the application of black paint atop the women’s pale flesh changed the implications of performance entirely.

18

Like a bevy of Black Venuses, Queen Anna and her ladies—whom Jonson describes as “twelue Nymphs, Negro’s; and the daughters of Niger”—entered the masque in a magnificent illuminated seashell chariot designed by Jones to appear as though it was moving on the waters of the elaborate set. The aquatic vehicle was attended by twelve Oceaniae, marvellous sea maidens portrayed by blue-face female masquers, who served as torchbearers to light the festivities (fig. 3).20 Jonson’s profuse commentary prefacing the masque does not describe the material means of metamorphosis used to transform the white ladies of the Jacobean court into the daughters of Niger. It does make clear, however, that he intended Jones’s designs to showcase the exoticism of the dark-skinned demi-goddesses as a crucial element of the performance:

2021the colours, Azure and Siluer; [their hayre thicke and curled vpright in tresses, lyke Pyramids,] … Iewels interlaced with ropes of Pearle. And, for the front, eare, neck, and wrists, the ornament was of the most choise and orient Pearle, best setting of[f] from the black.21

Continental Europeans seemed to have had a more favourable opinion of the masque: the Venetian envoy Nicolò Molin, for example, described it to the doge as “very beautiful and sumptuous” and made no mention of the blackface queen and her ladies.22 However, English attendees were less positive in their assessment of the display. Representing the “generally hostile” reception of the masque from the British members of court, Sir Dudley Carleton famously denounced the performance in a letter to Sir Ralph Winwood:

2223Theyr apparel was rich, but too light and curtisan-like for such great ones. In steed of visards [instead of vizards], theyr faces and armes up to ye elbowes were painted black, which was disguise sufficient for they were hard to be knowne, but it became them nothing so well as theyr read and white, and you can not imagine a more ougly [ugly] sight then a troope of leane-cheek’t moores [lean-cheeked Moors].23

In a very similar letter written to Sir John Chamberlain, Carleton complained: “Theyr black faces, and hands w[hi]ch were painted and bare vp to the elbowes, was a very lothsome sight, and I am sory that strangers should see owr court so strangely disguised”.24 What bothered Carleton, it would appear, was not the act of racial impersonation by Queen Anna and her ladies but the unusual means by which they achieved it.

24What exactly was the big deal? Before extending Andrea Ria Stevens’s insights about the materiality of blackface in the performance of The Masque of Blackness to appreciate what was accomplished by painting the queen and her ladies black, it is helpful to understand what black paint could not do within the dramaturgical logic of the masque. Unlike more conventional racial prostheses such as vizards, stockings, or gloves, black paint could not facilitate the miraculous transformation from Black to white that the text anticipates for the daughters of Niger. Although Jonson declared that “it was her Majesties will, to have them Black-mores at first”, Anna and her ladies were black at first and at last; at the conclusion of The Masque of Blackness, the daughters of Niger are still as black as ever. While the conceit of the Masque of Blackness turned on the potential instability of skin colour, material constraints demanded that it remain fixed. Although we do not know the specific materials used to make it, the black pigment applied to their skin could not be easily removed during the performance, and the promised racial metamorphosis failed to transpire before the masque’s finale.25 This would have to wait until The Masque of Beauty, whose title indicates the by then definitive crystallisation of the opposition of Blackness and beauty that the opening of The Masque of Blackness suggests was still somewhat inchoate just three years earlier. Once Anna and her ladies went black, they could not, within the space of the production, ever go back.

25Engaging in more than a flippant exercise of anachronistic wordplay, I deliberately highlight the resonance of this modern colloquial expression with Anna’s early modern performance to trace connections (and divergences) between understandings of “race” and ideas of anti-Blackness emergent in Anna’s time and those operative in our own, especially as they intersect with gender. Ironically, although the masque’s plot constructed Blackness as something entirely fungible, its performance visually suggested its intrinsic immutability. The notion of Blackness as an indelible stain that no solvent, passage of time, or successive number of generations might mitigate emerged as the dominant perspective in the British world before the end of the seventeenth century.

This idea was legally enshrined, for example, in the first anti-miscegenation legislation passed in British North America in Maryland in 1691. It also arguably underpinned even earlier laws, including one passed in Virginia in 1662 that established hereditary slavery through maternal relationship and ultimately gave way to the “one-drop rule” that came to define Blackness in the United States. Moreover, not exclusive to the British world, the notion of Blackness as immutable also informed the sistema de las castas of colonial New Spain. Under the casta system, successive infusions of Spanish ancestry over three generations could restore the status of ancestral lines infused with Indigenous American heritage back to Spanishness, but there was no similar “remedy” for those that included African forebears. No amount of Spanishness could dilute the “stain” of Blackness.

Significantly, eighteenth-century paintings that visualise the casta system disproportionately depict negras (rather than negros) as the source of this racial “pollution”. They represent the threat of “invisible” Blackness almost exclusively in female form through the alvina, a white-appearing woman with undetectable (and possibly unknown) African heritage, whose union with a white Spaniard results in the dark-skinned torna atrás (known as a “throwback” in the English-speaking world). However, the male correlate of the alvina, the alvino, is virtually unknown. While the masque’s conclusion did not foreclose the possibility of dispatching the stubborn blackness painted onto the body of Anna and her ladies, its failure to deliver the anticipated transformation harbingered notions of Blackness as a permanent adulteration. These ideas became firmly entrenched in the following decades, as did the specific burden women’s bodies were forced to bear in relation to racialised ideologies.

Sharing Skin, or, That’s So Meta: Meta-Metamorphosis and the Materiality of Racial Masquerade in The Masque of Blackness

The relationship of the mechanism of racial impersonation (paint) to the production’s failure to realise its own logical resolution takes on greater significance in light of the masque’s status as a work not merely of metamorphosis but of meta-metamorphosis. Anna and her ladies are not simply Black nymphs who long to become white; they are white women masquerading as Black nymphs who long to, but who do not in the context of the production, become white. Both the language and the plot of Jonson’s text underscore the unsettled nature of “Blackness”, and especially of its relationship to beauty in early modern British culture, by evincing the ambiguities, ambivalences, and contradictions that were inherent in understandings of and attitudes about what was later characterised as “racial” difference. In describing dark skin as a gift from the sun, The Masque of Blackness reflects early modern “climate theory”, which attributed complexional variation among humans to differences in climate.26 Jonson’s language implicitly constructs blackness as a form of augmentation, an acquired rather than essential feature that might ultimately be removed because that which is given can also be taken away. Citing David Wills, Farah Karim-Cooper underscores that “prosthesis” inevitably suggests the notion of “amputation—or a lack or deficiency”.27 The meta-metamorphosis operative in The Masque of Blackness complicates all this, however, holding ideas of essence versus additive and augmentation versus amputation in anxious and unresolved tension. Moreover, in constructing their blackness as embellishment rather than essence, Jonson’s drama also arguably—and ironically—implies that whiteness is Niger’s daughters’ original state.

26As Dympna Callaghan has observed, “climate theory both coexisted with and contradicted competing theological and empirical understandings of race (dark skin did not fade when Africans were shipped to England), neither of which were entirely discrete or coherent”, and was itself plagued with inherent inconsistencies that inform Jonson’s text.28 The sun both bestows blackness as a gift and has the power to shine with the force to blanch an Ethiop white. The entire plot of the masque relies on the credible possibility of the removal of blackness, but the text also consistently alludes to its stubborn endurance, which the embodied performance seemed to confirm.29

28Acknowledging Blackness as enduring in more ways than one, the masque’s broader celebration of the coexistence of Blackness and beauty (in spite of the inherent anti-Blackness that drives its plot) offers an early modern take on the contemporary quip “Black don’t crack!”. Despite being motivated by an admirable commitment to his daughters’ happiness, Niger clearly finds their dissatisfaction with their dark complexions incomprehensible and utterly ridiculous. In addition to “the perfect[e]st beauty” he finds in their dark skin, he observes:

30Since the fix’t colour of their curled haire,

(Which is the highest grace of dames most faire)

No cares, no age can change; or there display

The fearefull tincture of abhorred Gray;

Since Death hir selfe (hir selfe being pale & blue)

Can neuer alter their most faith-full hew;

All which are arguments, to proue, how far

Their beauties conquer, in great Beauties warre;

And more, how neere Diuinity they be,

That stand from passion, or decay so free.30

Since the fixed colour of their curled hair,

(Which is the highest grace of dames most fair)

No cares, no age can change; or there display

The feareful tincture of abhorred Gray;

Since Death herself (herself being pale &

blue)

Can never alter their most faithful hue;

All which are arguments, to prove, how far

Their beauties conquer, in great Beauties war;

And more, how near Divinity they be,

That stand from passion, or decay so free.

Since the fixed colour of their curled hair,

(Which is the highest grace of dames most fair)

No cares, no age can change; or there display

The feareful tincture of abhorred Gray;

Since Death herself (herself being pale &

blue)

Can never alter their most faithful hue;

All which are arguments, to prove, how far

Their beauties conquer, in great Beauties war;

And more, how near Divinity they be,

That stand from passion, or decay so free.

Niger praises the consistency and endurance of his daughters’ superior beauty that persists unaltered by emotional stress or age. Moreover, Blackness in the text boasts more claims to beauty than the anti-ageing properties of melanin. In addition to The Masque of Blackness’s insistence on the dark beauty of his daughters, the text describes Niger himself as “fair”, both conceding that fairness need not be synonymous with pale skin and underscoring the association of fairness with qualities, such as luminosity, in addition to whiteness.

Scholars such as Hall and Stevens have traced the growing tendency to associate beauty, fairness, and whiteness in early modern England. Karim-Cooper expands and complicates the discourse around race and fairness by observing that, although it was increasingly associated with a pale complexion, “fairness” also connoted more than superficial whiteness. Even as the relationship between paleness and fairness calcified, whiteness could not in itself render one “fair”, as the concept continued to convey the lustre or glow associated with silver or pearls.31 Described as of a “beauteous race”, Niger and his daughters embody this kind of shining beauty and

3132… though but blacke in face,

Yet, are they bright,

And full of life, and light.

To proue [prove] that Beauty best,

Which not the colour, but the feature

Assures vnto [unto] the creature.32

Karim-Cooper’s chapter analysing “the ways in which the material lives of cosmetics are mediated” in Ben Jonson’s plays has little to say about The Masque of Blackness.33 Its status as a royal masque and use of black paint do not quite fit the “culture of cosmetics”—applications to the skin in pursuit of idealised beauty that is akin to make-up or the beauty culture today—she primarily studies in that text. However, debates surrounding the use of cosmetics in early modern Britain render the choice of paint as the means of racial impersonation in The Masque of Blackness particularly intriguing, especially as the cosmetics controversy frequently played out explicitly on the Renaissance stage, with satirists—including Jonson—using “cosmetic practices and fashions as the targets of their attacks”.34

33Dramatic scenes involving the application of make-up were common, and Stevens observes that “stage blackness is so often accompanied by self-reflexive references to the paint that creates it”.35 The painting of Queen Anna and her ladies (and their eventual stripping) occurred entirely off-stage, however, and did not figure in the text or plot of The Masque of Blackness, potentially rendering their black appearance more disorienting for viewers. If, as Stevens suggests, “only a readily removable black pigment [could] represent blackness as a disguise or a temporary deviation from an original whiteness”, the persistent blackness of Anna and her ladies even at the masque’s finale suggested a disconcerting permanence.36

35Amplifying this implication of the stubborn endurance of the stage make-up, the application of the paint itself also hinted at the unsettling possibility of indelible blackness. Some anti-cosmetic tracts, Stevens observes, actually attributed dark skin to a culture’s habitual cosmetic use.37 John Bulwer’s Anthropometamorphosis, for example, suggests that the ancient ancestors of the Moors had an “affectation of painting” that permanently altered their complexions over time.38 Thus, the act of applying pigment to Anna’s skin to alter her complexion potentially risked the status of the queen’s own racial integrity.

37Additionally, the perceived degradation of the complexion made paint out to be a poison, which, being composed of highly toxic substances, it actually was at the time and suggested that it could infect more than just the surface. The skin, permeable border between the outside world and the corporeal interior, could both transfer this poison through its surface and absorb it through its pores.39 The cosmetic blackness of Queen Anna and her ladies thus suggested a potential contagion to themselves and the masque’s guests. Carleton’s revulsion is palpable as he describes how the Spanish ambassador “tooke owt [out] the Queen and forgot not to kiss her hand [part of the convention of the masque], though there was danger it would haue [have] left a marke on his lips”.40 Even more provocative: what must Carleton have thought of the blackened Anna, six months pregnant with Princess Mary, as she twirled about in her gilded slippers and showed the court her painted arms and legs through her diaphanous gown?41 Might the royal fetus have absorbed the contagion of Blackness through the pseudo-placental interface of her mother’s painted, tainted skin? With Anna’s porous flesh the primary source of protection for the future of the royal bloodline that was housed in her pregnant body, the decision to paint that flesh black—despite the controversial status of cosmetics during the period and given the disproportionate responsibility maternal bodies would ultimately be made to bear for the “transmission” of Blackness—registers as a deliberately provocative choice intended to at least skirt the bounds of propriety and perhaps directly court controversy.

39Stevens asserts that representing Blackness with paint ultimately worked to clarify and redefine whiteness and Blackness in the context of an emerging British nationalism.42 I would argue that the use of paint as the material mechanism of racial masquerade in The Masque of Blackness’s drama of meta-metamorphosis actually muddled any notion of Black and white as separate and discrete. Its emphasis on the skin suggested a literally permeable boundary between Black and white that transgressed racial lines rather than clarified them. In The Masque of Blackness racial transformation is at once possible and impossible, and Blackness exists as simultaneously fungible, indelible, and potentially transmittable. Paint rendered both the materiality and the meaning of Blackness—and potentially whiteness—fundamentally fraught by confounding distinctions between the player and the role she played.

42Unlike a mask, which would have established a physical distinction between Anna and the dark-skinned demi-goddess she impersonated, the decision to paint the queen’s skin eliminated any appreciable distance between the Black body of Niger’s daughter and the ostensibly white one of the queen: Queen Anna and the daughter of Niger literally shared the same skin and the very same face. Moreover, while wearing a physical mask might materially reinforce a clear distinction between player and part and theoretically rendered its wearer anonymous, blackface allowed the performer to embody another persona while her own identity still remained recognisable. Vaughan suggests that this might have been a motivating factor for Anna, who “desired to be recognized through her extravagant disguise”.43

43But, beyond the spectacle, what did recognition of the faces of Anna and the court ladies underneath the insufficient disguise of black paint achieve? As Sir Dudley Carleton’s assertion of the unfathomability of “a more ougly sight then a troope of lean-cheek’t moores” indicates, the startling incongruity between the facial features of the white women and those the audience would have expected of actual daughters of Niger contributed to the controversy sparked by their performance. Karim-Cooper emphasises that several early modern theorists writing about ideals of beauty acknowledged that beauty might come in many shades and originate in many places. Nevertheless, for these theorists beauty required a kind of internal coherence, and the features that made a Moor beautiful were necessarily different from those that defined the beauty of a white person.44 Although The Masque of Blackness consistently praised the beauty of Niger’s dark-skinned daughters in words, the facial features of the black-painted white ladies who portrayed them created a visual dissonance that rendered that beauty unimaginable. While Anna and her ladies might still be recognisable beneath the black paint they wore, their gimmick obscured the possibility of Black beauty suggested by Jonson’s text.

44Like Vaughan, Stevens also emphasises the possibility of recognition in spite of disguise as critical to the decision to forgo masks in favour of black paint. She notes that “paint is an intimate and idiosyncratic medium that generates an effect specific to the performer himself [sic]. Two performers can each wear the same mask; two painted faces, while resembling each similarly made up, will nonetheless be unique”.45 To this I would add the important observation that, although Jonson’s text called for Anna to play one of the twelve daughters of Niger, whose attire, the dramatist insists, “was alike, in all, without difference”, the material choice of blackface over black masks meant that Anna and the other women would have been recognisable as individuals by the unique contours of their own faces.46

45Incognegro No More: Reframing A Daughter of Niger as a Portrait of the Queen

This prompts the question: whose face it is that confronts viewers of Inigo Jones’s A Daughter of Niger with her self-possessed gaze? From the top of her elaborately feathered and bejewelled scrolled headdress to the tips of her impossibly tiny, golden-slippered feet, the seemingly giant woman—magnificently outfitted in a richly patterned ensemble of azure and gold with accents of silver and pearl—commands the space of the textured page upon which Jones has painted her. Her majestic form fills almost the entire length of the creamy sheet and makes the spiky rays of the adornment extending from the diadem at the centre of her headdress seem as though they might pierce the top border of the page and penetrate reality. It is a fitting crown for this regal woman, enhancing the confident countenance that perfectly suits the broad shoulders and sturdy upper body of her imposing frame. Multiple insinuations of delicacy and movement do nothing to soften the force of the woman’s unyielding expression. Jones washes the bottom of the page with lateral sweeps of sheer pale grey blue. The gestural squiggles suggest the tide that carried Niger’s daughters on their journey, lapping the bottom edge of the composition like waves upon which the woman’s dainty feet ostensibly float, while the billowing diagonal folds of the figure’s garments imply the presence of the wind. Anchored by nothing, however, save the sheer strength of her own will, she will not be moved.

Jones’s picture of the formidable dark-skinned woman contrasts sharply with the description of Niger’s inconsolable, weeping daughters in Jonson’s text. Proud and authoritative, she hardly seems like the sort of woman who would be driven to the depths of despair by a few lines of poetic drivel, nor does she strike the viewer as some generic nymph, merely an anonymous figure upon which to hang a costume design. Although her dark complexion diverges from Anna’s legendarily pale loveliness, her visage—with its large forehead, firm brow, long nose, lean cheeks, small mouth, and definitive chin—bears an unmistakable resemblance to confirmed portraits of Anna of Denmark. Immediately upon its performance, The Masque of Blackness would have been inevitably associated, even synonymous, with Queen Anna. It was, after all, the first of the “Queen’s Masques” and, whether or not she had personally thought up the idea to forgo black masks in favour of black paint, Jonson had emphasised that her explicit request had inspired the plot in which she and the ladies of her court impersonated Black women. In light of all this and especially since Anna herself portrayed the character depicted in Jones’s A Daughter of Niger, I find it curious that the picture—to the extent that it has been discussed at all—has received attention only as a generic costume design and has not been recognised or interpreted as a specific portrait likeness of Anna.

Understanding the work in this way draws attention to it as a discrete visual culture object that, in addition to its function as a costume design and material artifact of The Masque of Blackness as an historic dramatic production, also manifests its own distinct agenda. What might have been at stake in such a portrait, and how is the fraught nature of Anna’s embodied performance of Blackness evident in the materiality of its graphic representation in Jones’s picture? Finally, especially because the material mechanism used for both the performance and the picture—that is, paint—would have been identical, how could Jones effectively make a visual distinction between a portrait of the queen in blackface and a portrait of the queen with a Black face?

Given that the initial idea for the women to star in a racial masquerade had been Anna’s, Jones must have had the queen specifically in mind as he crafted the design for the costume to be worn by Niger’s daughters in The Masque of Blackness. The inaugural project in what would become a decades-long association with the Stuart court that was fostered by Anna’s patronage in particular, The Masque of Blackness initiated the most important professional relationship of Jones’s celebrated design career. Jones may, in fact, have first become attached to the Stuart court through Anna, not James, and considered her, not the king, his primary patron. According to the 1655 recollections of his assistant John Webb, Jones, who had long lived abroad, had initially been associated with Anna’s brother Christian IV.47 The claim that he worked for the Danish monarch before ever being employed by the Stuarts remains unsubstantiated by hard evidence, but Jones was definitely part of an English delegation, led by the earl of Rutland, that was at Christian IV’s court when James and Anna visited to celebrate the birth of her nephew in 1603.48 Webb names the queen as responsible for bringing him to England, underscoring the perception of Jones as primarily connected to Anna rather than James, and asserts that “being desirous that His own native soil … should enjoy the fruits of his laborious Studies; Queen Ann here honoured Him with her service”.49

47Whether or not Anna played a major role in bringing Jones to England or initially established him there, she was unequivocally the principal champion of his career. Assigning him to prominent commissions, Anna mobilised the architectural projects Jones designed for her as tools in her own self-fashioning. For example, as Jemma Field traces, the grounds and palace at Greenwich, which are now primarily celebrated as an example of Jones’s architectural ingenuity, began as Anna’s personal project when, in 1616, she entrusted Jones with realising her vision for the royal estate. Initiated, commissioned, and built by Anna, Greenwich was also intended to be paid for by the queen directly. Following Anna’s death, Henrietta Maria completed the project, making it a rare example of a structure built and paid for by royal women.50 Highlighting the importance of Anna’s building projects to her public persona, Paul van Somer’s famous 1617 “power-portrait” of the queen in hunting dress (which, not so incidentally, features the queen with a Black horse groom) showcases the new vineyard and border wall that Anna had built as part of her renovation of Oatlands. It also prominently features, as “a tribute to the Queen's love of building and patronage of Inigo Jones”, the classical gateway that he had designed for her.51

50Recognising A Daughter of Niger as a portrait likeness enhances its status as an early visual record of Jones’s participation in Anna’s self-fashioning, perhaps even one made by Jones in the hope of cultivating the queen’s favour. Given that Anna communicated directly with Jonson about her vision for The Masque of Blackness, one wonders if she might have provided Jones with explicit instructions about the costumes she and her ladies would wear. Might she even have previewed the costume design before the ensembles were made? If she did, she would have set a precedent for her working relationship with Jones that the two would later follow for the queen’s building projects. For example, Jones submitted advance designs for the Queen’s House at Greenwich for Anna’s approval and then revised them according to her direction when his first attempts failed to meet her expectations.52 If Anna did preview Jones’s costume design, what might she have thought at the sight of herself as the daughter of Niger? Did she see her own pale body painted black or might she have entertained, through Jones’s picture, the provocative thought of herself with Black skin?

52While we can only speculate about what Anna might have thought of Jones’s sketch, Orgel and Strong made their assessment of the work clear. Along with the figure of the brilliant blue torchbearer Oceania, the other extant design connected to The Masque of Blackness, A Daughter of Niger represents the earliest of the theatre designs for the Stuart court that they documented. Compared to later designs, which they speculate Jones may have completed after a second tour of Italy sponsored by the earl of Arundel between 1613 and 1614, Orgel and Strong offer a generally unfavourable assessment of the designs for The Masque of Blackness. They note Jones’s adherence to what they consider to be “less advanced” English artistic conventions, asserting that the painted sketches “betray no knowledge of Italian Renaissance draughtsmanship”, and find “plodding labour” in what they perceive as the clumsily opaque application of the paint.53 They accept Jones’s watercolour sketch of the imposing black-skinned woman as a generic costume design representing any one of the twelve daughters of Niger in the masque’s cast, and dwell on what they consider to be the work’s technical deficiencies. Perhaps blinded by the figure’s blackness, they never entertain the notion that A Daughter of Niger might be a portrait likeness of Anna. However, understanding the intriguing picture in the context of the preceding images presented by Orgel and Strong that influenced it, and of other costume designs made by Jones, supports an interpretation of A Daughter of Niger as a portrait of the queen.

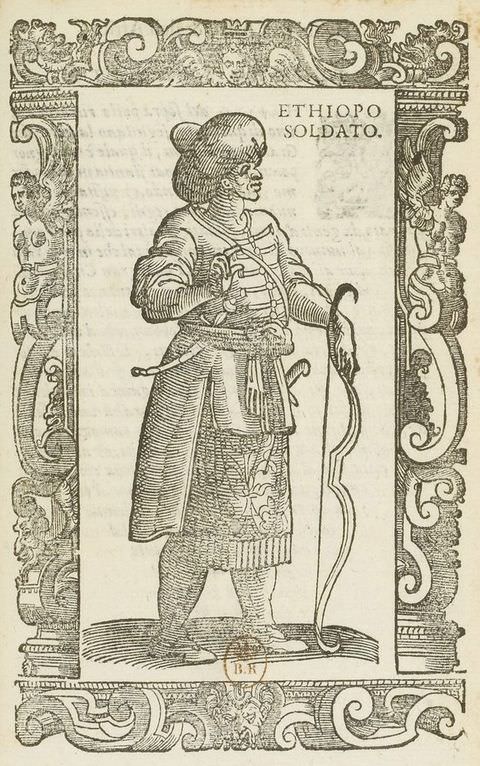

53A motley assortment of images likely influenced A Daughter of Niger. Despite what Orgel and Strong deem a decidedly un-Italian Renaissance composition, the influence of Italy is not entirely missing from Jones’s design. They identify a 1598 edition of Cesare Vecellio’s well-known costume book De gli habiti antichi et moderni di diverse parti del mondo as the origin of many of the components of the figure’s splendid sartorial display, tracing the striped underskirt and diagonally draped mantle to Vecellio’s Aethiopian Virgin (fig. 4), the shorter overskirt to his rendering of an Aethiopian soldier (fig. 5), and the elaborate scrolled headdress to the book’s illustration of a Thessalonian bride (fig. 6).54 They also propose that Elizabethan topographic and proto-ethnographic documentary drawings, exemplified by the work of artists like John White, may have been a source of visual inspiration for Jones’s costume designs in general.55

54

The commanding figure in A Daughter of Niger also evinces compositional similarity to Elizabethan and Jacobean full-length portraits of sitters in exotic costumes such as Marcus Gheeraerts’s Portrait of an Unknown Woman (fig. 7).56 Indeed, the carriage of Jones’s A Daughter of Niger—erect posture, direct authoritative gaze, strong arms extended to the front, and holding an accessory while striking a pose of inexplicable solidity on incongruously delicate feet—is almost identical to any number of period full-length portraits of high-born ladies. The similarities between Jones’s A Daughter of Niger and these early seventeenth-century portraits lends credence to understanding it as a portrait, especially as its unique composition distinguishes it from Jones’s other costume designs.

56

Comparing Jones’s A Daughter of Niger to his other costume designs—particularly designs known to have been made for Anna—provides additional support for interpreting the work as a portrait of the queen. In general, Jones’s costume sketches tend to focus on attire and accessories, highlighting the specifics of silhouette and embellishment rather than the individual who wears them. The only design Jones executed for a female masquer that features a direct gaze even remotely comparable to that of the figure in A Daughter of Niger is the one he made for Candace as played by Lady Anne Winter in The Masque of Queens. The figure’s engagement with the viewer, however, is more coquettish, as befits a lady at court, than commanding, as befits a queen. More often, the figures in Jones’s designs essentially function as mannequins for the costumes, and he typically renders them in full or three-quarter profile, with averted gazes and in a generic, even schematic, manner. Jones frequently drew them as classical statues rather than actual human bodies and certainly not to resemble any specific likeness. This observation holds true even for designs where notes on the sketches identify the wearer of the costume and their assigned role in the masque, as in many of the sketches made for The Masque of Queens in 1609. For that masque, Jones depicted the figures in a variety of ways; the design for Artemisia, played by Lady Elizabeth Guilford, shows the figure as a classical sculpture rendered in profile (fig. 8), while the design for Camilla, played by Lady Catherine Windsor, looks more human but still rather generic and with an averted gaze (fig. 9).

Jones even followed this practice in other designs known to have been made for Anna, such as a headdress for Bel-Anna also from The Masque of Queens (fig. 10). Interestingly, Orgel and Strong speculate that a 1610 design for a headdress for Tethys’ Festival, or The Queen’s Wake —Jones’s only other design for a female masquer in which the figure’s gaze confronts the viewer authoritatively as in his depiction of Niger’s daughter—represents Jones’s attempt at a portrait likeness of Anna (fig. 11).57 They reproduce Jones’s design for this headdress alongside a well-known portrait of Anna, inviting viewers to assess for themselves the likeness between the two.58 Despite the nearly identical contours of the faces in the black-and-white sketch for the headdress, the painted portrait to which they compare it, and the figure in A Daughter of Niger, the image of Niger’s daughter fails to prompt the same speculation from Orgel and Strong. Could they not see past the dark skin of the figure’s painted visage to find Anna’s distinctive face staring back at them?

57

Painting Problems: Painting White Skin Painted Black

I propose that Orgel and Strong’s failure to see Anna’s face in A Daughter of Niger demonstrates that Jones’s picture may have failed in the task it endeavoured to accomplish. If in The Masque of Blackness “The person of the queen is”, as Sujata Iyengar asserts, “thus inseparable from her blackened body as Daughter of Niger, keeping the barrier between black and white in suspension, through technologies of skin color” and prompting the disconcerting spectre of racial instability, then Jones, in the portrait, labours to keep these two bodies separate in spite of their shared skin.59 To achieve this goal, I contend that Jones uses paint—the same material that, in the masque’s performance, troubled the stability of skin colour—in an effort to assert that stability in the picture. What Orgel and Strong perceive as “plodding labour”, I propose, instead reveals the traces of Jones’s struggle to accomplish this tricky task.

59In striving to represent Anna’s body as distinct from the paint layered on top of it, Jones implicitly tried to represent the fundamental integrity and inviolability of the queen’s whiteness. A Daughter of Niger evinces the designer’s purposeful efforts to distinguish the pristinely pale body of his royal patron from the dark-skinned one of the character she impersonated in the masque. Jones’s rendering of the figure’s complexion in a dull, sooty hue appears deliberate. The unnatural flesh tone is markedly different from the lustrous black that the masque’s text associates with the idea of Black beauty and lacks the luminosity associated with early modern ideals of fairness.60 Jones had to figure out how to depict Queen Anna, in the guise of Niger’s daughter, as black while also avoiding the possibility that her body might be misread as Black, and his attempt to convey this results in the figure’s unfamiliar and uncanny blackness. Indeed, the figure’s bizarrely black complexion, while captivating, is not Black and certainly not beautiful in the way Jonson’s text describes. It works as a distraction that compels the viewer to try to make sense of her appearance rather than to probe beyond the surface of its dark disguise to discover her identity.

60The insights of the philosopher and art historian Jacqueline Lichtenstein suggest that painting itself may have been the source of Jones’s struggle in A Daughter of Niger:

61Pictorial activity does not merely modify, embellish, or make up an already present reality whose insufficiency could be revealed if its ornaments were removed like a woman without her make-up. Behind the layers of paint used by the painter to represent forms in a picture, nothing remains, just the stark whiteness of the canvas [or, in this case, paper]. No reality hides behind the colors … painting hides or covers nothing. It does not present us with an illusory appearance, but with the illusion of an appearance whose very substance is cosmetic.61

Although painting the queen black for the performance of the masque had its own implications in the context of the live production, the boundary between flesh and pigment—however porous and problematic—nonetheless still existed in some tangible way. In Jones’s picture, however, there is no material difference between the queen’s physical reality and the pigment used to alter it, so the task of rendering a graphic representation of that embodied reality—that is, painting a queen who is painted black—was an enterprise fraught with its own unique difficulties.

In contrast to the fluid line and transparent handling of paint that the artist evinces in later designs, for example, 1613’s Lords’ Masque, Strong and Orgel disparage Jones’s line work and particularly the lack of facility he demonstrates with watercolour technique in his early designs. This may be a fair assessment given that the figure’s costume in A Daughter of Niger lacks the delicate colour and more accomplished draughtsmanship of the few colour costume designs Jones executed later in his career. I contend, however, that Jones’s technique in his rendering of Anna portraying Niger’s daughter indicates not ineptitude but an intentionally inconsistent treatment of colour and line that reflects the artist’s attempt to use paint to legibly represent paint—that is, to separate the queen’s white body from the layer of painted blackness on top of it.

Jones clearly takes more time with the figure here than in other designs and, to the modern viewer, the depiction of costume seems almost secondary to his delineation of the figure itself. For example, in comparison to the light touch he uses in the line work that delineates her dress, Jones distinctly outlines the darkened figure’s scandalously bare arms with a firm hand, bringing attention to the physical body beneath the costume (figs. 12 and 13). The contrast of the sturdy line and dark pigment of the arms with the airiness of the diaphanous, billowing sleeves that graze them amplifies the viewer’s sense of the weighty reality of the parts of the figure’s body not concealed by her gown.

Except for the strategic juxtaposition of these sheer sleeves and her bare but for black paint arms, Jones clearly approaches the painting of the woman’s body differently from the painting of the costume that covers it. Conflicting with Carleton’s eyewitness description of the actual costume as “too light and curtisan-like”, the dense application of paint Jones uses to render her gown, which Strong and Orgel find amateurish, makes the ensemble appear stiff and heavy.62 This is especially evident in the azure and gold middle section where tiny gaps of white paper can be seen between the thick application of rich cobalt blue pigment, revealing that Jones did not paint the costume over a ground layer (fig. 14).

62

However, his treatment of the figure’s skin and hair evince something quite different. Without relying on the now familiar physiognomic caricatures, such as exaggeratedly thick lips, wide noses, and startingly white eyes, that were later employed to render Blackness hyperlegible—and legibly inferior—from whiteness by making it ugly and/or ridiculous, in this early example of blacking up, the artist must work to ensure that black paint cannot be mistaken for actual Black skin. Close inspection of the object reveals that, in the parts of the picture meant to signify black paint on top of white flesh, Jones uses a subtly golden base layer of cream pigment that appears to shine through the dark colour applied on top of it. In this way, Jones suggests the true and unequivocal whiteness of the figure’s body despite its dark appearance (see figs. 12 and 13). While this may not be a virtuoso handling of the medium, I do find it to be a deliberate one.

Jones’s curious rendering of the hair and base of the figure’s headdress demonstrates a similar approach. Jonson describes the performers’ coiffures as “thicke, and curled vpright in tresses, lyke Pyramids”, which seems somewhat different from the scrolled hairstyle or headpiece in Jones’s picture. Commentators seem to have focused exclusively on the women’s skimpy attire and the black paint applied to their skin, giving us no sense of the appearance of the hair of Niger’s daughters in the performance. The absence of post-performance chatter about the women’s hair suggests that the shocking effect of the women’s painted skin and scanty costumes completely overshadowed the hairdressing or that the performers’ coiffures were arranged differently from—and perhaps much more simply than—the rendering in Jones’s design. Whatever the case for the performance, in Jones’s A Daughter of Niger the hairstyling makes its own statement. Rendered in the same charcoal hue as the figure’s painted flesh, the three elements—skin, hair, and headdress—bleed into one another, distinguished only by their different textures. However, close looking reveals that the figure’s dark curls are shot through with visible strands of what ostensibly represent Anna’s own legendarily flaxen locks (fig. 15).

After this observation, it feels impossible not to see Anna in the subtle hint of blue in the murky pools of the figure’s eyes peering forcefully down at us from Jones’s page. The material limits of painting leave Jones with no easy means of differentiating Anna’s body from the paint that stains it, and the picture strains under its obsession with separating the queen’s white beauty from the daughter of Niger’s Blackness. But Jones’s attempts to reinforce this separation ultimately separated Anna’s identity from A Daughter of Niger altogether; the Blackness of Niger’s daughter apparently blinded viewers to the picture’s likeness of Queen Anna’s distinctive face. However, despite Jones’s best efforts to divide them and history’s inability to see them both at once, Anna and Niger’s daughter have always been and will be forever fixed and bound together on the page.

After Thoughts: How Does It Feel to Be a Problem?

Accepting Inigo Jones’s A Daughter of Niger as a portrait likeness of Anna of Denmark whose tortured materiality evinces the artist’s anxious preoccupation with distinguishing the queen’s white body from the Blackness of the role she performed compels us to interrogate the stakes entailed in making that distinction.63 As the borders of Europe looked to expand, eventually stretching across the stormy seas traversed by the daughters of Niger to include far-flung lands and “exotic” peoples, the British sought to distinguish themselves from those they desired to conquer and control, and their own white bodies became a primary mechanism by which they did so. Somewhat counter-intuitively, the popular nineteenth- and twentieth-century Blackface performances that are more familiar to most people today than The Masque of Blackness heightened this distinction in the service of white supremacy. In these acts of racial impersonation, white performers appropriated Black bodies—or, more accurately, a caricature of Black bodies—only to exaggerate the perceived shortcomings and inferiority that white Europeans and Americans projected onto Black people. Superficially, the blackface of Queen Anna and her ladies in The Masque of Blackness seems far removed from the performances of racial impersonation that followed several centuries later. The denigrating physiognomic exaggeration typically associated with nineteenth- and twentieth-century Blackface performance in Great Britain and the United States has no place in the text of The Masque of Blackness, nor do the stereotypical “deficiencies”—physical and otherwise—projected onto Black bodies to buttress anti-Black racism. On the contrary, Jonson’s text repeatedly acknowledges the intrinsic beauty of the daughters of Niger, and the invented “deficiencies” associated with Blackness have nothing to do with the “problem” that its plot must resolve.

63This, however, does not mean that the masque did not promote anti-Blackness or that it was somehow less problematic than more overtly racist performance, both at court and on the professional stage, in early modern British culture. Jones’s anxious attempt to separate the body of Great Britain’s real white queen from Niger’s fictional Black daughter in his portrait of Anna of Denmark reveals an arguably more insidious iteration of anti-Blackness underpinning the masque. Imagined deficiencies of Blackness are not the problem in The Masque of Blackness; Blackness itself ultimately is. The Masque of Blackness registers an inchoate moment in the history of racialised bodies in the early modern British imagination when Blackness could be simultaneously acknowledged as beautiful and construed as a crisis. Niger’s daughters do not weep because their blackness makes them ugly; they weep because they now believe their Blackness does. Anna’s blackface performance in The Masque of Blackness and the fraught task of painting the queen black that Jones essayed in A Daughter of Niger confirm that, as early as 1605, Blackness did not have to be imagined as exaggeratedly ugly, buffoonish, or otherwise deficient to be understood as abhorrent. Blackness itself had already been imagined—and imaged—as a problem of dramatic proportions.

Acknowledgements

For Julian who also thought this was a cool image. This article began as a talk delivered at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC, in 2016 for a symposium on racial masquerade organised by Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw, and I am extraordinarily grateful for the opportunity she offered me to think about an image I had rather randomly encountered as her student. I would also like to thank Cherise Smith, who also participated in that symposium, for the comments she offered there and her continued support in all the years since. An invitation from Kimberly Poitevin to join a panel she had organised for the Renaissance Society of America convening in 2023 provided the chance to resurrect and reconsider my original paper, and the generous feedback and encouragement I received from those who attended that session significantly improved the ideas I offer here. This project also benefited immeasurably from the support and careful reading of my work wives, Sarah Danielle Allison and Stephanie Porras; the thoughtful comments of the other contributors to this special issue during our London workshop; the anonymous reviewers, whose insight and suggestions—along with those of the journal and special issue editors—made this an incalculably better article; the dependable research assistance of Gabi Janis, Caroline Niver, Xavier Pasquier, and Bella Waltzer; and the patience and support of my family, especially Isaiah and Zora.

About the author

-

Mia L. Bagneris is an associate professor of art history and Africana studies and Chair of the Department of Africana Studies at Tulane University, where she also co-founded and directs the Crossroads Cohort. Her scholarship focuses primarily on the long nineteenth century, exploring the representation of race in the Anglo-American world and the place of images in the histories of slavery, colonialism, empire, and the construction of national identities. She is the author of Colouring the Caribbean: Race and the Art of Agostino Brunias (Manchester University Press, 2018), co-author of Reframing Black Art: Case Studies in Nineteenth-Century Visual Culture (Routledge, forthcoming), and is currently finishing her third book, Imagining the Oriental South: The Enslaved Mixed-Race Beauty in British Culture, c.1865–1900. Her research and other scholarly activities have been supported by grants and fellowships from the Yale Center for British Art, Harvard University’s W.E.B. Du Bois Institute, the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, the American Council of Learned Societies, and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

Footnotes

-

1

Letter from the Privy Council to King James, December 1604, in Calendar of the Cecil Papers in Hatfield House, vol. 16, 1604, ed. M. S. Giuseppi (London, 1933), 389, British History Online, https://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-cecil-papers/vol16/. ↩︎

-

2

Bernadette Andrea, “Black Skin, The Queen’s Masques: Africanist Ambivalence and Feminine Author(ity) in the Masques of Blackness and Beauty”, English Literary Renaissance 29, no. 2 (1999): 256. Andrea’s article extends the groundbreaking scholarship of Kim F. Hall, Things of Darkness: Economies of Race and Gender in Early Modern England (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1995), particularly her articulation of the “poetics of color”. ↩︎

-

3

Ben Jonson, The Masque of Blacknesse, Renascence Editions: An Online Repository of Works Printed in English between the Years 1477 and 1799 (transcribed 2001), 2, https://pages.uoregon.edu/rbear/jonson1.html. Unless otherwise noted, all quotations from the masque are from this edition, with spelling and punctuation modernised only where explicitly noted. ↩︎

-

4

Ben Jonson, The Masque of Blacknesse. ↩︎

-

5

Scholars rarely focused on The Masque of Blackness before the late twentieth century and certainly not before the 1990s, when the rise of (post)colonial studies and Black studies prompted a surge of interest in the relatively neglected masque. In general, it was mentioned and sometimes discussed in early scholarship on Ben Jonson and British court masques, but it has been so comprehensively studied since the 1990s that limitations of space preclude a full historiographical account here. Noteworthy among the early scholars to mention The Masque of Blackness in pertinent ways are Percy Simpson and C. F. Bell, “Designs by Inigo Jones for Masques & Plays at Court”, Volume of the Walpole Society 12 (1923), http://www.jstor.org/stable/41830403; and D. J. Gordon, “The Imagery of Ben Jonson’s The Masque of Blacknesse and The Masque of Beautie”, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 6 (1943): 122–41, DOI:10.2307/750427. Kelly’s article on the “challenge of the possible” in The Masque of Blackness initiated a wave of dedicated scholarship on the masque, particularly the agency of Queen Anna in its production and the implications of her performance. Ann Cline Kelly, “The Challenge of the Impossible: Ben Jonson’s ‘Masque of Blackness’”, CLA Journal 20, no. 3 (1977): 341–55. Meanwhile, the ideas introduced in Hall’s now canonical text, Things of Darkness, both generally and in the specific attention she gave the masque, underpin the treatment of race and its intersections with gender in many of the subsequent scholarly texts cited throughout this article. ↩︎

-

6

Stephen Orgel and Roy Strong, The Theatre of the Stuart Court; including the Complete Designs for Productions at Court, for the Most Part in the Collection of the Duke of Devonshire, Together with Their Texts and Historical Documentation (London: Sotheby Parke Bernet; Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973). Simpson and Bell had catalogued and briefly described the designs in “Designs by Inigo Jones for Masques & Plays at Court” in 1923; but Orgel and Strong offer the first comprehensively illustrated publication that attends to the works as visual materials, albeit in a primarily documentary rather than an interpretive manner. ↩︎

-

7

Throughout this article, I have used “black” to refer to material colour and “Black” as an adjective meaning “of African descent” or related to the modern concept of race. Accordingly, I have followed the same practice for “blackness” and “Blackness”. Although, as I argue at the article’s conclusion, I consider them to be related expressions of anti-Blackness, I have used “blackface” with a lowercase b to describe the female masquers’ racial impersonation in The Masque of Blacknesse to distinguish it from the more well-known nineteenth- and twentieth-century iterations of “Blackface”, which employed standard conventions of racial caricature not evident in Anna of Denmark’s racial masquerade. However, as my argument makes plain, the distinction between “black” and “Black” is fraught and sometimes subjective. ↩︎

-

8

See Andrea Ria Stevens, Inventions of the Skin: The Painted Body in Early English Drama (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2013), 88. Moreover, as Meg Twycross and Sarah Carpenter observe, professional stage productions also employed “blacking up” as an alternative to masking for reasons other than racial impersonation, for example to represent the devil or souls condemned to hell. Meg Twycross and Sarah Carpenter, Masks and Masking in Medieval and Early Tudor England (Abingdon: Routledge, 2016), 215–16. ↩︎

-

9

Andrea, “Black Skin, The Queen’s Masques”, 253. ↩︎

-

10

For an excellent recent examination of the visual and material culture connected to Anna’s court, including her patronage of the arts and its impact exclusive of royal masques, see Jemma Field, Anna of Denmark: The Material and Visual Culture of the Stuart Courts, 1589–1619 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2021). ↩︎

-

11

The second masque, The Masque of Beauty, an explicit sequel to The Masque of Blackness, was performed on 10 January 1608. However, Samuel Daniel’s The Vision of Twelve Goddesses, performed on 8 January 1604, almost a year to the day before The Masque of Blackness, was the first masque Anna organised after the death of Elizabeth I and the establishment of the Stuart court in England. See Barbara Kiefer Lewalski, “Anne of Denmark and the Subversions of Masquing”, Criticism 35, no. 3 (1993): 341–55. ↩︎

-

12

Given that every royal masque hinged on a conceit that amounted to a deferential allegory flattering the king, the beaming Britannia, who is “temperate, and refines / All things upon which his radiance shines”, would have been understood as King James. ↩︎

-

13

Jonson, Masque of Blacknesse, 2. ↩︎

-

14

Andrea, “Black Skin, The Queen’s Masques”, 252. ↩︎

-

15

For a more comprehensive treatment of Elen More, as well as the history of Black presence and “spectacles of Blackness” in the British courts, see Andrea, “Black Skin, The Queen’s Masques”, 257–64. ↩︎

-

16

These oft-rehearsed details are recorded in, for example, Ethel Williams, Anne of Denmark: Wife of James VI of Scotland, James I of England (Harlow: Longmans, 1970), 20–21, and repeated in Andrea, “Black Skin, The Queen’s Masques”, 260–61. ↩︎

-

17

Papers Relative to the Marriage of King James the Sixth of Scotland with the Princess Anna of Denmark (Edinburgh, 1828), 40, quoted in Andrea, “Black Skin, The Queen’s Masques”, 261. ↩︎

-

18

Virginia Mason Vaughan, Performing Blackness on English Stages, 1500–1800 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 65 (emphasis original). ↩︎

-

19

Stevens notes that, while scholars such as Hardin Aasand, Andrew Gurr, Barbara Kiefer Lewalkski, and Virginia Mason Vaughan attribute the choice of blackface make-up to Queen Anna and relate it to her project of authoritative self-fashioning, it is impossible to know with certainty who was responsible for suggesting the idea because Jonson’s commentary does not explicitly address the question. Stevens, Inventions of the Skin, 91. ↩︎

-

20

One of very few scholarly articles to attend to Jones’s images, and the only critical discussion of the significance of the blue-face of the Oceaniae in The Masque of Blackness, is Pascale Aebischer and Victoria Sparey, “Black, White and Blue: Pregnancy and Unsettled Binaries in The Masque of Blackness (1605)”, Multicultural Shakespeare: Translation, Appropriation, and Performance 22, no. 1 (2020): 15–36. ↩︎

-

21

Jonson, The Masque of Blacknesse, 3. ↩︎

-

22

Extract from a dispatch sent home by the Venetian ambassador Nicolò Molin, dated 27 (i.e. 17) January 1605, in Archivio di Stato, Venezia, Piero Duodo e Nicolo Molin Amb., 1604, Senato III [Secreta], Filza III.Inghilterrai. Both the transcription of the original Italian and the English translation are available at The Cambridge Edition of the Works of Ben Jonson Online, https://universitypublishingonline.org/cambridge/benjonson/k/masque/44Blackness_Venice/. ↩︎

-

23

Orgel and Strong, The Theatre of the Stuart Court, 89; Sir Dudley Carleton, Letter to Ralph Winwood, January 1605 (transcription), Northamptonshire Record Office, Winwood Papers, 3 https://universitypublishingonline.org/cambridge/benjonson/k/masque/40Blackness_Winwood/. ↩︎

-

24

Sir Dudley Carleton, Letter to John Chamberlain, 7 January 1605 (transcription), The National Archives, Kew, SP 14/12/6, fols. 8v–9, https://universitypublishingonline.org/cambridge/benjonson/k/masque/34Blackness_SP14_12_6/. ↩︎

-

25

Dympna Callaghan and Farah Karim-Cooper document the various materials and recipes in Europe to create the effect of Black skin that circulated among theatre professionals in the Renaissance, though it is not clear that any of these were used for the court performance of The Mask of Blackness. Dympna Callaghan, “‘Othello Was a White Man’: Properties of Race on Shakespeare’s Stage”, in Shakespeare Without Women (London: Routledge, 2000), DOI:10.4324/9780203457726-7; Farah Karim-Cooper, Cosmetics in Shakespearean and Renaissance Drama, 2nd ed. (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2006). ↩︎

-

26

For a comprehensive history of theories linking skin colour to climate, see Roxann Wheeler, The Complexion of Race: Categories of Difference in Eighteenth-Century British Culture (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010). ↩︎

-

27

David Wills, Prosthesis (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1997), 133, quoted in Karim-Cooper, Cosmetics in Shakespearean and Renaissance Drama, 114. ↩︎

-

28

Callaghan, “‘Othello Was a White Man’”, 75–96, 79. ↩︎

-

29

The abrupt switch from “black/blackness” to “Black/Blackness” between this sentence and the next is intentional, signalling that, while “blackness” might be imagined as a mutable condition, “Blackness” was forever. ↩︎

-

30

Jonson, The Masque of Blacknesse, 5, modernised below:

Since the fixed colour of their curled hair,

(Which is the highest grace of dames most fair)

No cares, no age can change; or there display

The feareful tincture of abhorred Gray;

Since Death herself (herself being pale & blue)

Can never alter their most faithful hue;

All which are arguments, to prove, how far

Their beauties conquer, in great Beauties war;

And more, how near Divinity they be,

That stand from passion, or decay so free. ↩︎ -

31

Karim-Cooper, Cosmetics in Shakespearean and Renaissance Drama, 12–13. ↩︎

-

32

Jonson, The Masque of Blacknesse, 4 (emphases added). ↩︎

-

33

See Karim-Cooper, Cosmetics in Shakespearean and Renaissance Drama, 113–33. ↩︎

-

34

Annette Drew-Bear, Painted Faces on the Renaissance Stage: The Moral Significance of Face-Painting Conventions (Lewisburg, PA: Bucknell University Press, 1994), 29. ↩︎

-

35

Stevens, Inventions of the Skin, 97. ↩︎

-

36

Stevens, Inventions of the Skin, 89. ↩︎

-

37

Stevens, Inventions of the Skin, 94. ↩︎

-

38

Bulwer, quoted in Stevens, Inventions of the Skin, 94. ↩︎

-

39

Early modern ideas about the skin—in particular, the implications of its porous nature—are the subject of a considerable body of scholarship, including, most recently, Evelyn Welch’s Renaissance Skin, which provides an excellent historiography on the topic in general and devotes its fifth chapter to an investigation of “Porous Skin”. Evelyn Welch, Renaissance Skin (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2025), especially 102–25. ↩︎

-

40

Sir Dudley Carleton, Letter to Ralph Winwood, January 1605 (transcription), Northamptonshire Record Office, Winwood Papers, 3, https://universitypublishingonline.org/cambridge/benjonson/k/masque/40Blackness_Winwood/. ↩︎

-

41

The production’s numerous references to and associations with fertility—specifically Queen Anna’s fertility—was understood by scholars at least as early as Gordon’s 1943 article on The Masque of Blackness’s imagery, who points out that the name of the nymph portrayed by the queen, Euphoris, derives from the Greek word for “fertile” and that the other nymphs bear monikers with similar implications. Gordon, “The Imagery of Ben Jonson’s The Masque of Blacknesse and The Masque of Beautie”, 126–27. Understanding the production in the context of Anna’s pregnancy is a primary focus for Ann Cline Kelly, “The Challenge of the Impossible”. For a recent discussion of the implications of Anna’s pregnancy in the performance, see Sara B. T. Thiel, “Performing Blackface Pregnancy at the Stuart Court: The Masque of Blackness and Love’s Mistress, or the Queen’s Masque”, Renaissance Drama 45, no. 2 (2017): 211–36. ↩︎

-

42

Stevens, Inventions of the Skin, 99–100. ↩︎

-

43

Vaughan, Performing Blackness on English Stages, 66. ↩︎

-

44