Abstraction’s Ecologies

Abstraction’s Ecologies: Post-Industrialization, Waste and the Commodity Form in Prunella Clough’s Paintings of the 1980s and 1990s

By Catherine Spencer

Abstract

This article’s aims are twofold: firstly, it argues that Prunella Clough’s engagement with consumer items in her paintings of the 1980s and 1990s constitute a sustained engagement with the fluctuating nature of the commodity form, moving beyond the established critical narrative whereby these works are understood as simply redeeming “everyday” materials. Secondly, in order to do this, it proposes new artistic frameworks for Clough’s work, moving away from her early association with Neo-Romanticism to foreground her relationship with Pop and Minimalism, and with Post-Conceptual painting. Clough’s late works, it finds, powerfully condense histories of industrial production and painting in Britain.

During the 1980s and 1990s, in the last two decades of a career that began in the 1940s, the painter Prunella Clough embarked on a distinct phase within her work. The first part of Clough’s oeuvre saw her create studies of dockworkers at Lowestoft harbour, and labourers in factories tending their machines. These were followed by industrial landscapes that became progressively more abstract throughout the 1960s and 1970s.1 By the mid-1980s, however, Clough had shifted her attention away from the chemical works, gravel pits, and electrical plants that occupied her for many years, and onto small, cheap consumer items that she glimpsed for sale in London corner shops and markets, and on souvenir stalls at decaying seaside resorts.2 The abstracted images Clough developed from her studies of these commodities constitute a unique episode in the artist’s sustained meditation on the gradual movement from an industrial to a post-industrial economy in Britain.

1Clough’s first public presentation of this new subject matter occurred in 1989, with her first exhibition at the Annely Juda Fine Art Gallery in London.3 The titles of works included in Prunella Clough: Recent Paintings, 1980–1989 signal Clough’s concern by this point with the synthetic, packaged, and mass produced: Wrapper (1985), Iridescent (1987), Sugar Hearts (1987), Toypack: Sword (1988), Sweetpack (1988), Vacuum Pack (1988), Plastic Bag (1988), and Party Pack (1989). Clough had already undertaken one substantial solo show that decade with an exhibition in 1982 at the Warwick Arts Trust, but this was dominated by the very different agendas of her Gate and Subway series.4 While the catalogue for the 1982 show contained an introduction and rare interview with the artist by the curator Bryan Robertson, the depth of the painter-critic Patrick Heron’s essay accompanying the exhibition of 1989 confirmed it as a significant departure.5 The result was a critical and financial success.6 It catalyzed Clough’s upward trajectory in Britain over the following decade, which saw her embark on major exhibitions at the Camden Arts Centre in London (1996) and Kettle’s Yard Art Gallery, Cambridge (1999).7 Shortly before her death in 1999, Clough received the prestigious Jerwood Painting Prize.8 The Annely Juda exhibition marked an important juncture in terms of Clough’s professional visibility, as well as the formal and conceptual stakes of her painting.

3Critics responded enthusiastically to Clough’s engagement with the often-discarded fragments of advanced capitalism. In his catalogue essay, Heron observed that Clough was “fascinated . . . by many of those products of the present age whose magical potential she alone has perceived and in her paintings has insisted on celebrating”.9 The wider critical reception of these works elaborated the implications of Heron’s analysis, with the critic Tim Hilton stating that each of Clough’s paintings presents “a singular representation of a trivial object that, by reason of its existence in a serious modern painting, acquires an ontological aura”.10 This perspective infuses reviews of Clough’s other exhibitions, which similarly stress the “redemptive impulse” of her work, leading to the characterization of Clough’s later paintings as primarily concerned with the metamorphosis of the everyday.11 By contrast, this essay seeks to complicate the established trope that Clough’s works from the 1980s and 1990s comprise acts of metaphorical, and for some commentators rather whimsical, salvage. Clough’s exploration of commodity life cycles is by no means unconnected with an interrogation of painterly process, but the ecologies established by her treatment of abstraction are far more nuanced than the straightforward transformation of “low” culture into “high” art.

9Rather, Clough’s paintings of the 1980s and 1990s instigate an extended investigation of the commodity form. The art historian Margaret Garlake describes how Clough’s later works “take an ironic look at a culture which has moved during her working life from austerity to satiety, in which industry is as much concerned with the production of instant rubbish as with the essentials of existence”.12 Yet Clough’s cognizance of waste constantly undercuts apparent affluence with the shadow of boom and bust. As Andy Beckett observes in his history of Britain during the 1970s, “from 1945 onwards, the issue of Britain’s decline changed from a matter for intermittent public debate into a major and growing preoccupation of political life.”13 This anxiety stemmed from the fact that “between 1950 and 1970, the country’s share of the world’s manufacturing exports shrank from over a quarter to barely a tenth.”14 The movement from an export to an import economy was linked to the rise of the service sector, the outsourcing of labour overseas, and the globalized circulation of inexpensive consumer merchandise. Clough’s studies of mass-produced items register these developments, while acknowledging the rapidity with which desirable commodities might become unwanted under the pressures of overproduction and designed obsolescence. Indeed, Clough’s approach to the commodity evokes Karl Marx’s famous description of it in volume one of Capital (1867) as “a very queer thing indeed, full of metaphysical subtleties and theological whimsies”.15 An awareness of the commodity’s fluctuating nature, and the ramifications of this for painting as a practice, threads throughout Clough’s work.

12The aims of this essay are twofold. In order to reconceptualize Clough’s late paintings as explorations of commodity relations, it proposes in tandem alternative artistic frameworks for considering Clough’s work, prising her away from an early and surprisingly enduring association with Neo-Romanticism, which Heron condemned as a “totally incorrect (and . . . damaging) misconception”.16 Clough’s treatment of consumer products can in the first instance be linked to the advent of Pop and Minimalism during the 1960s. Moreover, later debates about the so-called “death of painting”, followed by Post-Conceptual painting, provide suggestive contexts for her work. In the 1950s and 1960s painting enjoyed a pre-eminent position within the British, European, and North American art worlds Clough moved in, but she felt that the discipline subsequently entered something of a wilderness: “In the 1970s, ‘nobody was doing painting’.”17 The 1970s saw a diversification of artistic practices in Britain, and an embrace of alternative modes like Conceptual art and performance; according to John A. Walker in his history of this period, “painting and sculpture were experiencing [an] identity crisis”.18 This paralleled, and sometimes emerged directly from, conditions created by an economic downturn that saw strikes and fuel shortages.19 Although Clough exhibited fairly regularly in the 1970s, the decade’s reverberations can be detected in the works she created in the 1980s and 1990s.20

16Focusing on paintings that Clough displayed in 1989 at Annely Juda, the first part of this essay situates the preoccupations of Clough’s later work in relation to Pop and Minimalism, while the second shows how still life provided a fertile genre for addressing consumption and the history of industrialization. The final section argues that the understanding of the commodity form developed in response to these models shaped Clough’s interest in recycling through citation and collage. Such strategies in turn correspond to the re-emergence of painting after Conceptualism in the 1980s and 1990s. Rather than painting’s exhaustion, we find in Clough’s late canvases what this essay identifies as ecologies of abstraction. Clough’s tendency to transplant and reuse forms and compositional devices from earlier works, alongside her experimentation with collage and found objects, establishes a network of interlinked, even organic references at the level of representation. Through this network, Clough’s paintings participate in a system of wastage and renewal, in which abstraction functions as a signifier for change and adaptation. By re-thinking Clough’s work in this way, the essay gestures towards a wider re-assessment of the traffic between painting in Britain since the 1980s and its longer histories.

Pop and Minimalism: alternative frameworks

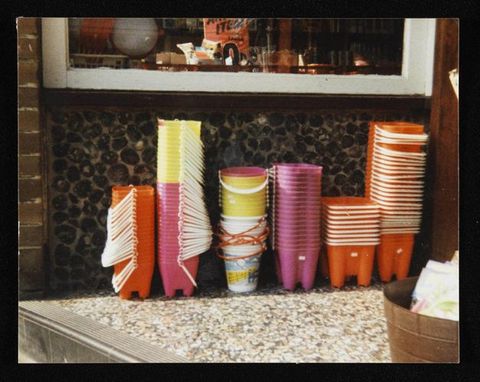

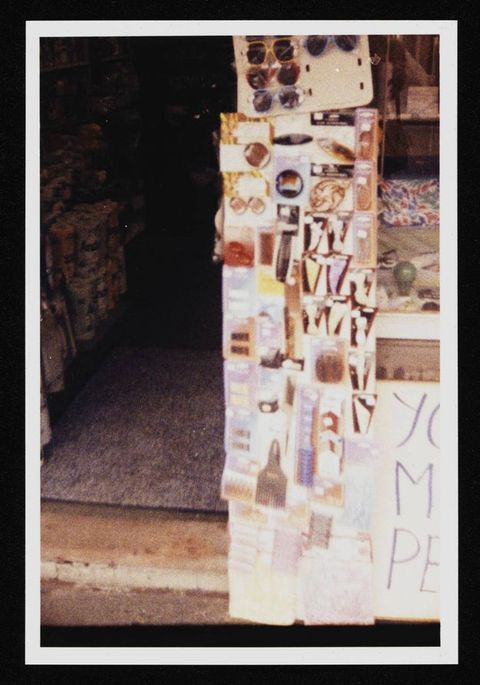

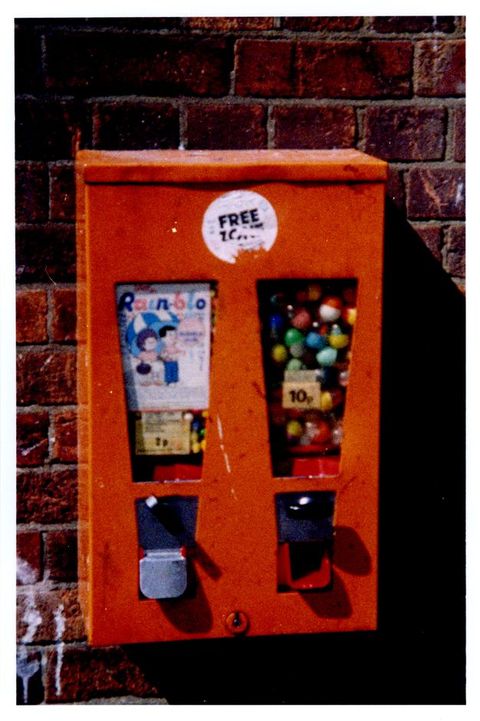

The works that Clough showed in 1989 with titles like Sweetpack, Plastic Bag, and Sugar Hearts were, Hilton observed, full of “cheap and ridiculous plastic goods . . . little bits of moulded inconsequence, hairgrips, imitation jewellery, balloons, bags, sweet wrappers and stickers”.21 The sources for these subjects can be found in Clough’s photographic archive. Clough claimed in her 1982 interview with Robertson, “I occasionally take rough photos, but often do not refer to them; they are only approximate aids for the memory.”22 Clough’s papers tell a slightly different story. They contain several series of neatly packaged photographs, dating back to the 1940s but increasing in number during the 1980s and 1990s. Leafing through these snapshots, which Clough’s friend Robin Banks describes as “rough and tough, visionary and sometimes cropped badly or squint”, reveals how her eye snagged repeatedly on certain clusters of objects.23 Favourite subjects include stacks of brightly coloured plastic chairs, buckets and domestic goods slotted together into conglomerate forms (fig. 1); sunglasses and hairclips arrayed in serried ranks on display cards (fig. 2); and footballs cocooned in semi-transparent plastic, rendering them mysterious. One particularly suggestive image shows a vending machine full of plastic capsules, each of which contains a small trinket promising a surprise, but veiled and obfuscated (fig. 3).

21

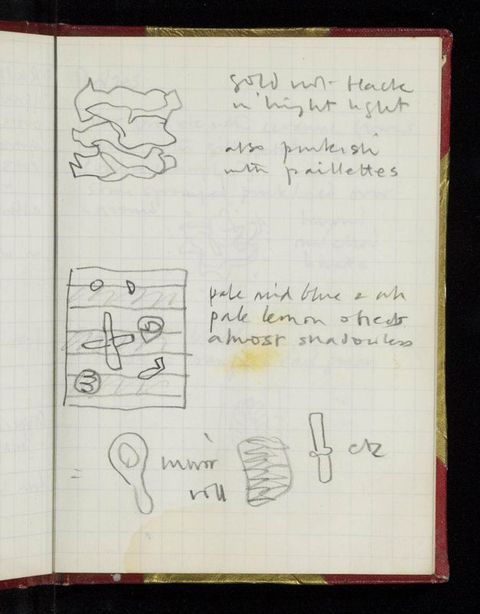

Sacha Craddock notes that “Clough uses photographs and to some extent mimics the photographic view”, and the cropped, close-up perspective employed by her canvases replicates the seemingly casual aesthetic of the quick snapshot.24 The distance insinuated and then marked by the camera lens, through its act of mediation, underscores Clough’s interest in transposition and change. Alongside her photographs, Clough made detailed written notes, such as those in a notebook dated to 1987: “‘Toiletries’ in spangle pale lime green & ‘silver’”, “Shellsuit violet / sand / turquoise” and “airless squashed balloons / pink, yellow, green on / wet pavement (4) / with damp patch”.25 These appear alongside rapid sketches of mirrors, toy windmills, and shapes that have already passed beyond recognizability (fig. 4). The notes and photographs unfold Clough’s attraction to ersatz materials, and with those that might be used for camouflage and dissimulation in urban life. It is not simply the case that Clough “metamorphoses” these objects, but that she recognizes their inherently unstable physical character, which simultaneously results from, and comes to stand as an analogue for, their mutable use and exchange value.26

24This instability inflects even the most ostensibly decipherable imagery in the paintings Clough showed during 1989, such as the central motif of Toypack: Sword (1988; fig. 5). In the version of this work reproduced in the Annely Juda catalogue, Clough presents a highly stylized, plastic-looking weapon, its hilt coloured sky blue and sherbet orange.27 The sword floats against a backdrop composed of unidentifiable, abstract fragments, like the delicate machinery of a watch scattered across a white field (nothing as substantial as “ground” is offered here). For Hilton, Clough depicts her central image “with just enough realism for one to be able to grasp that here is a toy”; this is the kind of frippery that could be picked up cheaply in a store selling mass-produced consumer items, and used to beguile a child for a few hours.28 The neologism of Clough’s title stresses the point: “Toypack” indicates that this sword is part of a “pack”, one of many identical cellophane-wrapped items.

27

The viewer of Clough’s paintings from the 1980s encounters commodity items at a slightly different stage in their life cycle to the celebration of newly minted goods in many Pop canvases of the 1960s. In Toypack: Sword an air of abandonment cuts against the toy’s pastel shades. Yet although Clough’s paintings have rarely been aligned with developments of the 1960s, she nonetheless recalled this period as especially generative, admitting “there were many difficulties in the Sixties which were also a pleasure and an exhilaration.”29 Clough kept abreast of occurrences in the United States, visiting New York and attending a variety of shows by American artists in Britain, such as Robert Rauschenberg’s exhibition at the Whitechapel Art Gallery in 1964, and Roy Lichtenstein’s Tate show of 1968.30 Toypack: Sword registers the legacies of Pop, albeit at a determined move, not simply in terms of its engagement with the commodity form, but in the way that the painting explicitly, almost jarringly, overlays representation onto abstraction, and in so doing fundamentally dislocates the co-ordinates of both.

29Reflecting on Clough’s career in the 1990s, Hilton observed: “I think she feels gratitude for the Sixties: not the fashionable or pop side of the decade but the way that painters kept putting new abstract ideas in the arena.”31 While suggestive, this statement ignores the role that abstraction played within Pop, particularly the strand of visual experimentation in Britain that coalesced around artists like Richard Smith and Robyn Denny.32 Furthermore, Hal Foster proposes that much Pop art is not easily resolvable as figurative or even realist in any meaningful sense: “Pop does not return art, after the difficulties of abstraction, to the verities of representation; rather, it combines the two categories in a simulacral mode that not only differs from both but disturbs them as well.”33 The navigation of abstraction and realism is a consistent aspect of Clough’s work, but it comes into sharp focus in her studies of toys and product packaging during the 1980s.

31

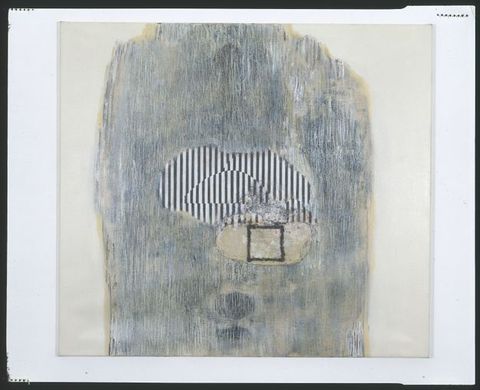

Equally, while Clough did not associate directly with Pop artists, she was familiar with the eminently fashionable 1960s phenomenon of Op art through her friendship with the painter Bridget Riley.34 Clough’s work provided a significant precedent for the younger artist. On encountering her work in 1953 at the Leicester Galleries, Riley recognized Clough as “unmistakably a modern painter”.35 Clough’s later paintings playfully return to the visual language of the 1960s. In Emerge (1996) Clough has overlaid several sections of black-and-white vertical lines within a scuffed surround, recalling Riley’s signature Op art images such as Fall (1963) and Current (1964). Emerge references both Riley’s pared down abstract striations and the perceptual flicker they establish, akin to the disruptive ripple of migraine aura (fig. 6). The edges of Clough’s striped sections do not quite match up, triggering the impression of movement and recession intimated by the painting’s title. Clough’s citation of Riley, however, is fully embedded within her own mode of working. Testifying to her predilection for “beaten up” canvases, in places the intersecting planes dissolve under a corrosive stain, their edges inexpertly sutured together.36

34Minimalist abstraction, however, clearly exerted a particular pull.37 The productive challenges posed by the 1960s encompassed “the first sight of Donald Judd and Sol Lewitt, for instance, and minimalism. The ideas were of a kind that were incompatible with the European tradition that I grew up with.”38 Clough also admired the work of the US painter Myron Stout, who created radically simplified black-and-white canvases dominated by single shapes. The British artist Rachel Whiteread recognized the intersections between Clough’s work and Minimalism, writing that she could “draw parallels” between her Postminimalist sculpture and Clough’s paintings.39 Clough’s reference to Judd is particularly suggestive, however, given his use of seriality and modular repetition, modes which can be indexed to the forms and processes of the postmodern, service-oriented, white-collar city.40

37Clough’s photographic archive demonstrates the importance of repetition and replication for her later practice, but this equally informs her use of other media. Clough was an accomplished printmaker, accustomed to making multiple iterations of the same image.41 Clough also constructed assemblages from mass-produced items amassed on walks through urban and industrial environments, including “old work gloves, wire mesh, pieces of rusting metal, a plastic toy sword, fragments of Formica, a shard of coloured pottery or a steam-rolled tin can”.42 Ian Barker recounts that the discovery of reliefs made from these objects in Clough’s studio after her death came as “a total surprise”.43 Clough nonetheless considered them part of her practice, as “on their reverse were Prunella’s carefully typed labels–identical to those she used to identify her paintings and drawings.”44 Clough exhibited an assemblage only once during her lifetime, at Annely Juda in 1989, emphasizing the correlations between her found object reliefs and the paintings in the show.45

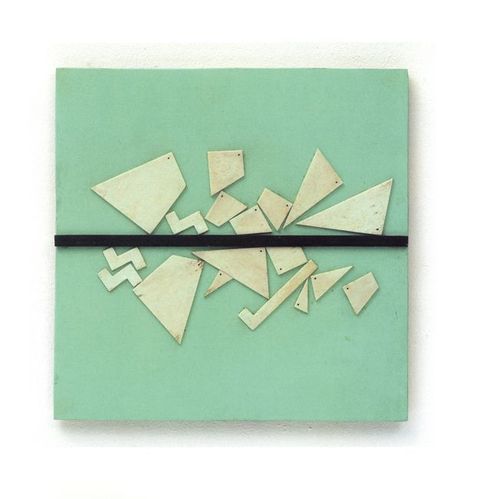

41One assemblage, entitled Equivalence (1965), offers a response to the provocations of the 1960s (fig. 7). Its white segments, nailed onto a synthetic mint-green background, look like the modular parts of a child’s construction kit wrenched from their original purpose. Clough’s use of plastic in this assemblage partakes in the artistic experimentation with new, prefabricated materials by practitioners associated with Pop and Minimalism. The abstract Equivalence proposed here is qualified. The white shapes either side of the central black partition seem like they could match up, but on closer inspection their number and distribution do not correspond. Similarly, Toypack: Sword offers a questionable equivalence. The painting presents the viewer with a depiction of a dagger that revels in its status of second-order representation, to the extent that its hovering form starts to seem like a simulacrum set adrift from a tangible referent. This inference migrates across Clough’s work from the 1980s and 1990s, stemming from the commodity’s paradoxical combination of materiality and abstracted labour power.

This slipperiness can be tracked back through Clough’s thinking about commodities from the outset of her career. During the 1950s, when Clough was still focused on landscape studies of factories, chemical works, and power stations, she and the painter David Carr exchanged a rich correspondence about these zones of production.46 Clough never explicitly critiqued commodity production, stating dispassionately to Carr: “The fact that a lorry is loaded by a crane with a crate of useless objects and driven to some place where nobody wants them seems just an aspect of human stupidity which is so constant that one can hardly get upset about it.”47 Clough developed her thoughts on the nature of objects useful and useless in other missives, notably during an extended account of a trip to a paint factory. Clough immersed herself in the details of the site, with its “vats of chemicals, drying powder, paste paint, boiling oil, resins, tanks, roller grinders, millstone grinders, ball grinders, distemper mixers, sheet-tin can makers, spot welders”.48 It is, however, the following passage that proves particularly revealing in terms of Clough’s conceptualization of production:

4649Men painty [sic] from head to foot, women putting on can handles without looking; and the transition–to simplicity, speed and visual boredom in the new “experimental” machines, the closed constructions where raw material is fed in and emerges a product, invisible, mysterious–whereas the others were open, explicit, logical.49

In the space of a sentence, Clough maps a seismic change from earlier modes of manufacture. Where machines were once “open, explicit, logical”, what she observes occurring in the new “experimental” factories is akin to alchemy, whereby the materials are put in, and the “product” emerges through unknowable processes. While humans attend to this transformation, the hand-made has been truly usurped by complex machinery, which has assumed total responsibility for the creation of goods.

It is as if Clough savoured this observation in order to apply it later in Toypack: Sword. The sword drifts over splinters of raw matter, replicating the sudden jump from inchoate material to final “product” observed by Clough at the paint factory. Its chemical colouring emphasizes that this is a plastic toy, recalling Roland Barthes’s evocation of plastic’s creation: “At one end, raw, telluric matter, at the other, the finished, human object. . . . More than a substance, plastic is the very idea of its infinite transformation; as its everyday name indicates, it is ubiquity made visible.”50 The plastic items that Clough photographed, and then filtered through abstraction into works like Toypack: Sword, mark an intensification of the material’s restless movement. By the 1980s, the production of budget plastic toys, accessories, and cleaning utensils had largely been outsourced from Britain to other countries, and the physical evidence of industrial production receded from the landscape. It is also tempting to read Toypack: Sword as an analogy for the act of painting and its transpositions, which in light of Clough’s captivation by the factory production of paint, simultaneously acknowledges the commodity status of the resulting work. Considering Clough’s work in relation to Pop and Minimalism, even if she ultimately kept both at a distance, enables the full extent of her work’s imbrication in cycles of mass production, industrialization, and consumption to emerge.

50Still life and “machine life” painting

In the list of paintings for Clough’s Annely Juda exhibition of 1989, one category impresses through its multiple recurrences: that of the still life. Of thirty-eight works in the show, six were specifically titled “still life”. In his essay, Heron alights on this aspect of Clough’s most “recent paintings”, which “are actually entitled Still Life or Interior– not that they can for a moment be thought of as continuing any tradition of spatial reconstruction of inhabitable domestic space”.51 Nevertheless, Heron felt, the paintings “seem to be projecting at us a spatial reality that implies those almost claustrophobic, limited sequences of depth which constitute the experience of the ‘still life’ or the ‘interior’”.52 This engagement with still life replays Pop art’s obsession with domestic products, and with the commodity fetishism invested in household goods, again indicating the importance of the artistic frameworks established in the first section of this essay for Clough’s practice.53 It moreover ties into longer traditions of the still life from the Dutch seventeenth century onwards, and, in Clough’s hands, with histories of commodity production in Britain.

51Heron connected Clough’s interest in still life to her regard for the French artist Georges Braque’s Cubist experiments.54 He compared Clough’s enthusiasm for “mass-produced objects, manufactured to meet popular tastes” to “the crude and patently ‘suburban’ furnishings of small cafés near Varengeville [that] inspired many of Braque’s most exquisitely classical pictorial inventions”.55 Clough’s use of the still life genre to reflect on mass-produced commodity items can be rooted in Modernist pathways to abstraction.56 It relates to a particular strand of Modernism that engaged with the everyday and the quotidian, the material effects of bourgeois living, and the impact of manufacturing and industry on popular culture.57 Yet, as Heron intimates, Clough’s still lifes diverge from these models, as they do not deliver the viewer into “inhabitable domestic space”, but rather a disorientating and unstable topography.

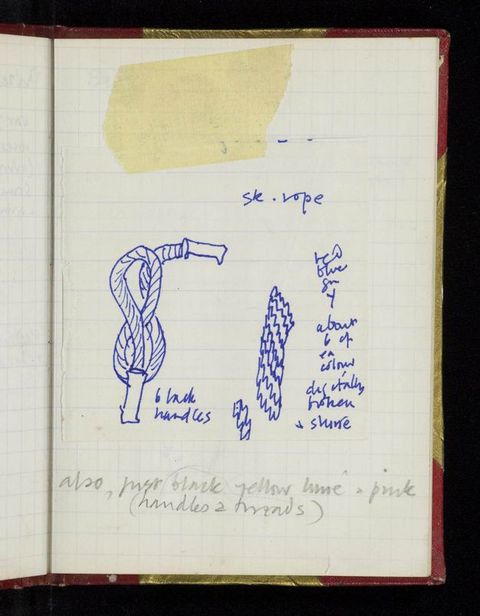

54These qualities can be discerned in many works Clough showed in 1989, notably Still Life (1987). At just over a metre high, it dominates the viewer’s visual field. A synthetically coloured green oval, shimmering with hints of oil-slick iridescence, hangs amidst a constellation of white dots on a black background as if suspended in a sediment-filled solution (fig. 8). A transparent penumbra unfurls around its central nucleus like a watermark, or cloud of gas. Heron described Still Life as a painting of “electrifying strangeness”, its queasy combination of diagrammatic flatness and shallow depth resisting coherent and identifiable representation.58 Certain details, however, offer associative possibilities. The central shape mimics the opaque capsules containing small toys in the vending machine photographed by Clough. The umbilical loop of cord or rubber hosing protruding into the top of the painting, partially obscured by a rectangular scrim, has affinities with a drawing Clough made in her 1987 notebook, glossed as a “sk rope” (presumably “skipping rope”) (fig. 9).59 The colours echo those Clough deployed in contemporaneous works like Sweetpack, also included in the show, redolent of glistering confectionary wrappings. While visually alluring, this palette’s evocation of oil on water alludes to the petrochemicals used to make plastic, so that like Toypack: Sword it evokes chains of commodity production.

58

Annely Juda insisted that Clough’s earlier work “was very important to understand what she was doing later on”.60 Clough’s consistent commitment to still life exemplifies this. In a review of Clough’s Leicester Galleries exhibition in London of 1953, the critic and painter John Berger claimed: “The key to understanding Miss Clough’s work is to realise that she is fundamentally a still-life painter. Above all, she is interested in the material, the density, the tactile ‘feel’ of the objects she paints.”61 During the 1940s, Clough did produce conventional still lifes of fruit, flowers, and shell arrangements.62 In Still Life with Yellow Marrows (1948) four yellow courgette blossoms, framed by a wicker basket, glow softly against a dingy brown-black background. Garlake notes that during the 1940s, when Clough’s career began, “still life was a simple subject demanding no more than a few vegetables or household objects, a favoured genre during the war when artists often spent long periods without studios or access to models.”63 Clough herself enjoyed “the sort of paintings that . . . are intensive rather than extensive . . . early Giacometti, early Morandi, early de Chirico even. They all have to do, in varying ways, with still life.”64 The title of Berger’s review–“Machine-Life Painting”–indicates, however, that the subject matter of Clough’s still lifes was not that of the bourgeois home.

60

Instead, Berger states, the “machine lifes” of the 1953 show, with titles like Night Train Landscape, The Cranes, and The Old Machine, are the progeny of the “industrial city–its greased axels, its riveted plates, its plane boards, its cables, ladders and tarpaulins, its rust, its crude protective paints, the condensation of its atmosphere”.65 As Clough succinctly put it: “Living rooms are not exactly enough.”66 For Berger, the central “paradox” of Clough’s paintings was her ability to treat landscape with the “intimacy” gained through close looking and scrutiny, hallmarks of the still life genre.67 Clough’s studies of industrial machinery often contain the composite elements of a detailed still life within them, but fragmented and dislocated.68 Industrial Interior V (1960) homes in on a section of machinery, the exact function of which remains wilfully obscure (fig. 9). Clough rendered the dramatically simplified black forms with a strong degree of stillness and isolation, enlivening them momentarily at their centre with a cluster of shapes including a red diamond and a dun-coloured circle, like the atomized building blocks of a still life study.

65Clough, meanwhile, saw her subject matter “mainly as landscape”.69 The landscape with which she was engrossed was “the urban or industrial scene or any unconsidered piece of ground”, marked with traces of human labour, littered with parts of machines and the infrastructural detritus of the built environment.70 Clough’s preference for this terrain emerged early in her career. In the catalogue essay he wrote to accompany her retrospective at the Whitechapel Art Gallery in 1960, Michael Middleton observed that Clough “paints these things . . . because she is tough-minded, non-escapist, determined to identify herself with the realities of a world shaped by industry, science and technology”.71 Clough and Carr deeply admired the painter Laurence Stephen Lowry, whose work provided a precedent for the serious consideration of what Clough sometimes called “urbscape”.72 Describing several paintings by Lowry that she had seen to Carr, Clough lingered on “the lighter, more open of the two big ones–which has that good strip of shed tops at the bottom and a railway arch. How inexhaustive [sic] his invention is in such detail!”73 Lowry’s industrial subject matter was a key aspect of his appeal, but his incorporation of observational detail was equally important, and it was this that Clough would carry into her still lifes.74

69The paintings that Clough created in the mid- to late 1980s continue to merge still life examination with landscape elements. Many reviews of the Annely Juda show in 1989 seized on the floating quality of Clough’s images, particularly Still Life. Sue Hubbard luxuriated in Clough’s “soft aqueous blues, thin watery greens . . . suggesting a world of ponds and rivers, or the magic of cells viewed under a microscope”.75 Other critics associated Clough’s play with scale, and her oscillation between macrocosmic and microscopic, with intimations of biological life.76 One reviewer discovered in Still Life a “floating emerald sac–are those eggs inside its belly?”77 This aqueous quality relates to the seascapes Clough made during and after the Second World War, which elicited the latent surrealism of the landmines and sea-defences that rendered the beaches uninhabitable.78 The legacy of these landscapes, border zones barred to everyday human use, informs the liminality of works like Still Life. Comparably, the sense of suspension in Industrial Interior V, as if the motion of the machine has just been stopped, or slowed down so that its interlocking segments can be observed, seeps into Still Life’s microscopic perspective.

75

The watery suspension of Still Life also relates to Clough’s paintings of the 1970s that resonate with industrial decline, such as By the Canal (1976). The letters Clough and Carr exchanged during the 1950s cumulatively portray a landscape of lively industry, but by the mid- to late 1970s Clough’s work increasingly responded to the slowing of industrial production.79 In 1981 the British economic historian Martin J. Wiener asserted that, “by the nineteen-seventies, falling levels of capital investment raised the specter of outright ‘de-industrialization’–a decline in industrial production outpacing any corresponding growth in ‘production’ of services”.80 By the Canal is strikingly minimal in its imagery (fig. 10). A rust-coloured rectangle dominates the canvas, bristling with small hooks along one edge. This orange shape, the colour of oxidizing iron and steel, is semi-transparent, merging with the blue of the background. Streaks of thinned paint course down the canvas like rivulets of condensation, so that the overall effect is of metal waste submerged underwater.

79Clough had a fondness for canals: “I like looking. Industrial estates, preferably by a canal (watery-flexible) will do.”81 By the Canal was painted when Britain’s canal network had almost completely ceased functioning for commercial purposes.82 Once the arteries that fed the Industrial Revolution, they sank into gradual decay. Significantly, given Lowry’s importance for Clough, in a 1966 essay on the artist Berger identified his paintings with “a logic . . . of decline” that expressed “what has happened to the British economy since 1918, and their logic implies the collapse still to come”.83 According to Berger, Lowry’s paintings provided visual evidence of the “recurring so-called production crisis; the obsolete industrial plants; the inadequacy of unchanged transport systems and overstrained power supplies”.84 Although not quite as apocalyptic as Berger’s analysis, Clough’s re-invention of the still life tradition as “machine-life” comparably considers the life cycle of industrial production, its ebbs and flows, starts and stoppages. Painted over a decade after By the Canal, Still Life shares its impression of indeterminacy and desertion.

81It is therefore arguably the 1970s, characterized by economic decline, the abandonment of industrial structures, and periods of strike and scarcity, which laid the ground for Clough’s experiments of the 1980s and 1990s.85 The stilled life of Clough’s later paintings executes an oblique but powerful commentary on the impact of the 1970s, which the novelist Margaret Drabble characterized in 1977 using the metaphor of “the ice age”.86 Frances Spalding compellingly observes, “it is as if [Clough] wanted to point to the brine and detritus left behind after a wave of modernity recedes, leaving the scraps, orts, fragments and sense of elegy for a vanished ideal.”87 Clough developed the still life genre to such a pitch that it could encapsulate the long, complex history of industrialization and de-industrialization in Britain, through an extremely streamlined and elliptical vocabulary.

85Samples, stacks, and painterly eco-systems in the 1990s

It is, however, important not to forget Clough’s exhilaration at the “first sight” of Pop and Minimalism when considering the still lifes of the 1980s and 1990s. What Heron refers to as the “electrifying strangeness” of Still Life might indicate an intrigued appreciation of outsourced mass production and its effects, as much as (if not more than) despair at stagnation. Clough’s adherence to still life suggests her consistent fascination with the products of industry, and with the possibility that their fluctuating value might endow them with a life of their own at the margins of perception. Equally, Clough’s return to the historical genre of still life during the mid- to late 1980s can be read as an affirmation of painting’s enduring relevance after the doubts of the 1970s, during which the medium risked association with obsolescence, as the melancholy, rusting surface of By the Canal tacitly conveys.88 By contrast, the works Clough embarked on in the 1980s share in the revivification of Post-Conceptual painting.89 Critics have downplayed the Postmodern qualities of Clough’s work, but the role of commodity culture and ironic painterly gesture in Toypack: Sword, and even Still Life, entail that these wider debates prove illuminating.

88Writing in relation to the Post-Conceptual painting of the German artist Gerhard Richter, the philosopher Peter Osborne argues that:

90What is peculiar about post-conceptual painting is that it must treat all forms of painterly representation “knowingly”, as themselves the object of a variety of second-order (non-painterly) representational strategies, if it is to avoid regression to a traditional concept of the aesthetic object. The difficulty is to register this difference without negating the significance of the painterly elements; to exploit the significance of paint without reinstituting a false immediacy.90

The “knowingness” of Clough’s painterly strategy, and her overt engagement with issues of representation, is clearly apparent in paintings like Toypack: Sword, which exploits the “significance of paint”, but acknowledges its remove from the “real”. This effect is one that Hanneke Grootenboer argues still lifes have long enjoyed, possessing as they do “the rare quality of raising the issue of the nature of their own representation”.91 Clough deepens this reflexivity through her choice of subject matter, particularly in the studies of packaging that she first showed at Annely Juda in 1989 such as Vacuum Pack (1988), and continued into the 1990s with works like Package Piece (1998).92

91

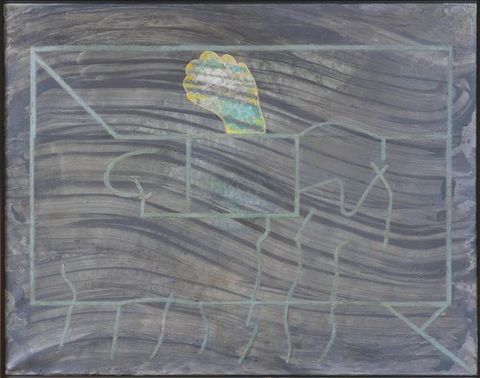

Vacuum Pack consists of a light grey grid overlaid onto a smeared background, as if a dirty surface has been given a hasty and ineffectual wipe (fig. 11). At the top of the painting, a small flare in pastel yellow, green, and pink emerges from the wire-like armature. Rather than the identifiable products celebrated by Pop art, or even by Postmodernism’s embrace of consumer culture, design, and fashion, Clough’s packaging is anonymous, subjected to extreme abstractions and distortions.93 Clough resists what Osborne describes as the restitution of “false immediacy” by emphasizing surface through her focus on packaging, foregrounding the dissimulating nature of her chosen subjects in a way that invokes high modernism’s adherence to the flatness of the picture plane, but ultimately subverts it to reflect instead on what Fredric Jameson theorizes as the “depthlessness” of late capitalism.94 Vacuum Pack offers an acute comment on this state. Vacuum-packing works by removing the air around an object and encasing it in plastic, to stop products from decaying and facilitate transportation; Clough’s title plays on the implicit paradox of attempting to package an absence or “vacuum”. The subjects of paintings such as Vacuum Pack are not static, identifiable “objects”, and their mutability aligns them with the ceaseless flow of abstracted commodity relations.95

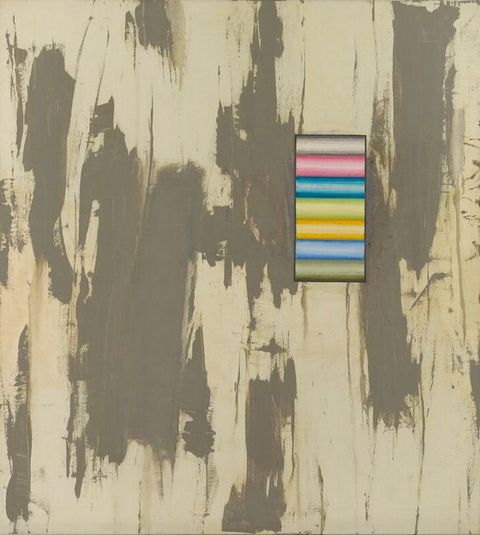

93The self-depreciating humour that imbues Vacuum Pack corresponds with Post-Conceptual painting’s knowingness. Samples (1997) is perhaps one of Clough’s most “knowingly” ironic paintings. In it, Clough placed a strip of rectangular colour blocks, ranging through grey, pink, blue, green, and yellow, within a dynamic field of paint-marks that parodies the overblown swagger of American Abstract Expressionism (fig. 12).96 The incongruous stripes of pigment resemble the charts produced by commercial paint companies, distributed at home improvement stores.97 Clough apparently pits the hand of the artist against machine-mixed, chemically calibrated colours. Yet the painting ultimately infers that such a comparison is a false one, as the recherché marks sweeping down the canvas fail to overwhelm the jewel-bright swatch, and seem just as pre-programmed and “false” as the acidic palette of the latter. We are back with Clough on her visit to the paint works, where manufactured colours partake in a process of transformation comparable to the application of paint on canvas in the artist’s studio.

96

Samples functions through the structuring principle of collage. Clough juxtaposes two different image registers, holding them in tension. This collaged quality, together with the titular reference to mixing and matching, signals another key aspect of Clough’s later practice, especially in the 1990s. During this decade, Clough ranged across her oeuvre, citing motifs and processes from previous canvases, photographs, assemblages, and prints, recycling them to establish what can be conceptualized as a painterly eco-system. In 1982 Clough reflected: “A painting is made from many . . . events, rather than one; and in fact its sources are many layered and can be quite distant in time, and are rarely if ever direct.”98 These “events” might include forms “left over from other paintings but [which] still demand to be used”.99 In this respect, Clough’s work diverges from dominant trends in Post-Conceptual painting. The ecologies of her abstracted motifs remain deeply imbricated with the history of her own work, and longer histories of painting in Britain, Europe, and the United States. Clough discovers a use-value in the outmoded and discarded that goes beyond knowing irony.

98

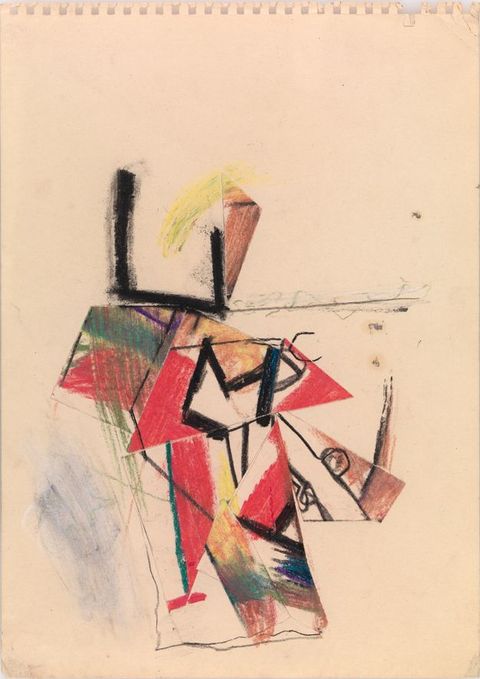

Although the collage aspect of Clough’s work intensified in the 1990s, it originated in the 1960s. Untitled (Pink) (1960s) is an intriguing early collage which forms a pendant to Equivalence. Its collaged fragments coalesce on the page of a sketchbook as if only fleetingly arrested (fig. 13). Significantly, these pieces appear to have been cut up from one of Clough’s own drawings, rendered dynamically in thick, waxy marks of pencil or crayon. Some sections suggest industrial materials–a filament of wire, iron girders–but the overall impression is of movement and play, while the hot pink colour anticipates Clough’s neon tones of the 1980s and 1990s. Untitled (Pink) verifies the artist’s longstanding interest in collage, specifically the re-appropriation of previously used forms and materials, as both a compositional and conceptual device. The fragment was an important model for Clough, as the artist reflected: “I’ve always found that I have learnt more from some (less accomplished) less resolved (tentative, fragile, smaller) or incomplete work–it’s more accessible; on the other hand . . . there is a real need to feel that one is taking part in something bigger than oneself.”100 An inferred relationship between part and whole in Clough’s collage and assemblage works intimates that she considered each as belonging to a larger system of interlacing interests, ideas, and sources.

100The citational qualities of Clough’s works extend to their relationship with the criticism they received. As well as referencing synthetic plastic goods, the saccharine hues Clough employed in the 1980s and 1990s can also be read as a way of deliberately wrong-footing the reviewers who designated her practice as essentially “feminine”. Writing with reference to US women artists grappling with the legacies of Modernism in the 1960s and 1970s, curator Helen Molesworth describes how in the formalist discourse dominated by Clement Greenberg, “the language of quality was largely the province of the critic, whose role it was to put forward the robust discourse of affirmation and persuasion. . . . What this often meant for women artists was a gendered use of language that served to undermine the authority of the works themselves.”101 Clough was subjected to such qualifications throughout her career.102 Words like “genteel”, “modest”, “feminine”, and “tasteful”, wielded with a strongly gendered subtext, have dogged her critical reception, while Clough’s personal reticence has been repeatedly invoked to explain the ambiguity of her paintings.103 Clough did not align herself with feminism, but it is tempting to speculate that the colours she chose in the 1980s and 1990s sampled and redeployed the ingrained assumptions of this critical discourse, in order to expose its superficiality.104

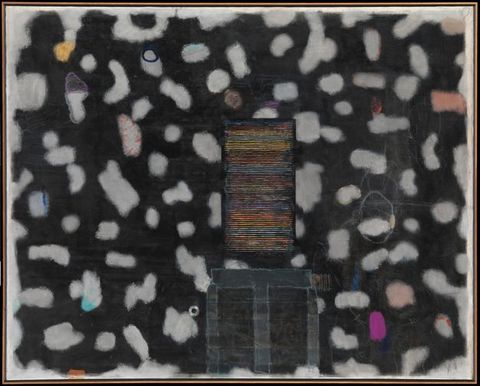

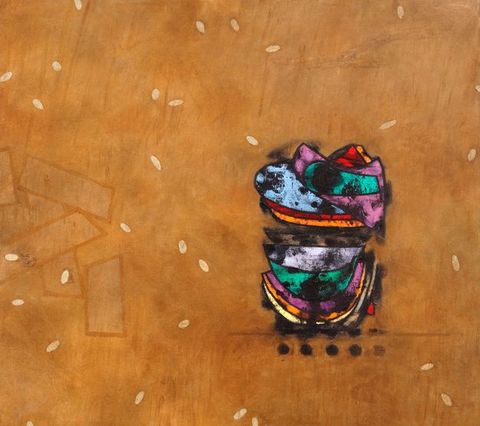

101Clough’s recurrent return to the stack motif exemplifies her interest in recycling forms. Stack of 1993 is an ambitious, large-scale canvas, in which the titular stack balances on top of a concrete-block-like pedestal (fig. 14). This “stack” is configured from rainbow-coloured gradations, glimpsed through bands of horizontal black lines like a ventilator grille. The perforated backdrop, which takes up the majority of the composition, reiterates this emphasis on veiling. Large ragged holes punctuate its black surface, concealing and partially revealing other shapes and brief bursts of colour lurking behind. While the “stack” invites comparisons with the slotted-together contours of chairs and buckets in Clough’s photographs, it equally infers a flat block illuminated at dusk. The scale of the background swings between sky and cells enlarged under a microscope, as in Still Life. Ghosts of multiple structures shadow Stack, from the cooling towers Clough studied in the 1950s, to the abandoned industrial sites that appear in canvases of the 1960s and 1970s. Margaret Drabble interprets Stack’s “bright colours” as celebrating “the glory of the world of choice”, yet this dense layering of references embeds it in a far more uneven history of production.105

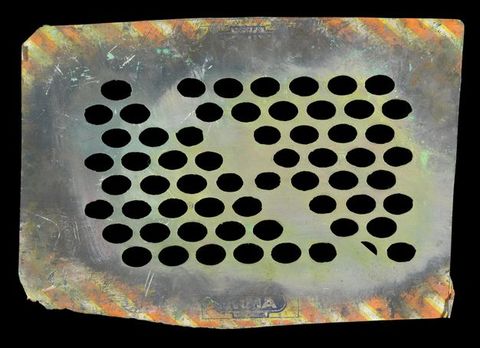

105This is further emphasized by Stack’s position within a longer chain of images. In Small Stack of 1996, Clough isolates the stack motif from the earlier painting, which now more than ever resembles a precarious tower of glittering merchandise (fig. 15). Small Stack’s title signals its seriality in terms of both content and making, parasitic as it is on the image of 1993. Small Stack also demonstrates how Clough employed found objects to make her work. Clough overlaid the central stack shape with a grid of regular dots, the precision of which indicates they were applied with a stencil. Clough improvised stencils from bits of old mesh, plastic draining boards, and sections of punched card (fig. 16).106 The surface invention of Small Stack stems from a process whereby Clough did not simply reference the obsolete detritus of mass-produced living in her canvases, but used it to generate replicable effects across her paintings. The result suggests that the worlds of painting and mass production are by no means polar opposites, but fundamentally interrelated.

106

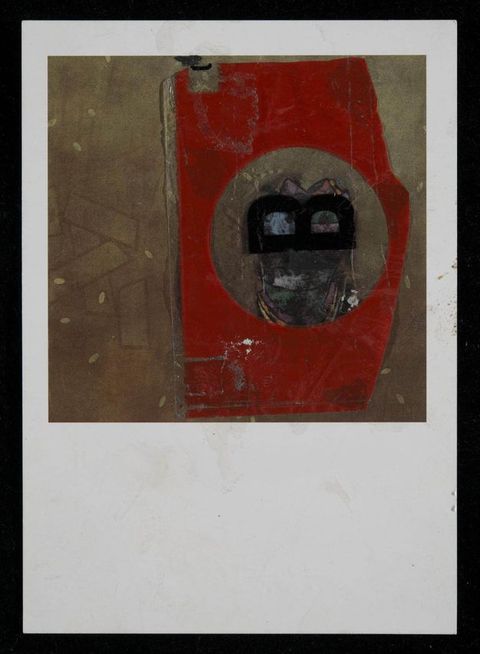

Through the connections Clough establishes between it and her other works, Small Stack participates in a painterly eco-system that refuses to ignore the pressures of commodity culture, but proposes ways in which waste items might be endowed with generative potential over time. This achieves its most suggestive expression in Small Stack’s afterlife. The painting featured in Clough’s Camden Arts Centre exhibition of 1996, and was evidently one of the works that the organizers selected to reproduce on promotional postcards. A stack of these samples found its way back to Clough, prompting the artist to meditate on her 1996 painting through its simulacrum. On forty-one postcards of Small Stack, Clough re-worked the image using collaged elements and stencils, exploring the infinite differences within repetition.107 In some cases, Clough tore away the glossy top layer of the card to mine the furry white seam beneath. Elsewhere, she added drawn and painted elements. Clough overlaid one postcard with a section of red cellophane wrapper, containing a transparent circle stamped with a black letter “B” (fig. 17). This aperture frames the “small stack”, but rather than allowing the viewer to focus on the original image, the de-contextualized lettering partially obscures the stack and transforms it into a new entity.108

107

It could be argued that the Small Stack postcards, particularly when combined with collaged packaging, witness the apotheosis of painting as commodity. Conversely, they might be understood as an attempt to use the former to resist and re-route the latter. Yet rather than either succumbing to the logic of consumption, or providing antidotes to mass production, Clough’s work instead approaches painting and the commodity fetish as part of the same networked ecology.109 For Theodor Adorno, artworks are “plenipotentiaries of things that are no longer distorted by exchange, profit, and the false needs of a degraded humanity”.110 Despite their aesthetic qualities, Clough’s paintings deliberately test and explore such systems of exchange and profit. By considering objects and images through the models provided by Pop, Minimalism, still life, Post-Conceptual painting and collage, Clough indicates that new eco-systems of ideas and forms must of necessity build on existing processes of exchange and production. Abstraction does not entail removal from these systems and their resulting products, but engagement with them. The poet Stephen Spender caught this paradox in his review of Clough’s first retrospective in 1960: “Her paintings are not abstractions: they are concerned with the nature of things; and great attention to the structure of things reveals, of course, abstraction.” Clough’s works of the 1980s and 1990s offer an intense contemplation of painting’s histories, and in so doing propose new angles from which these histories might be viewed.

109Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Sarah V. Turner and Mark Hallett for the invitation to share material that developed into this article at the Paul Mellon Centre; also Rachel Smith and Helena Bonett for organizing Materials, Movements, Encounters: Modernist Art Networks at Tate St Ives, and Rye Holmboe and Andrew Witt for Art in the Age of Real Abstraction at University College London, where previous versions were presented. Thanks also to Tate Archive for their assistance with Clough’s papers during cataloguing.

About the author

-

Catherine Spencer is Lecturer in Modern and Contemporary Art at the University of St Andrews. Her research and teaching interests focus on performance art since 1960, technologies of mediation, and feminism; she has published articles on these areas in Art History, Tate Papers and Oxford Art Journal. She has also written on abstraction and the legacies of modernism, including essays on the painter Prunella Clough for British Art Studies, and the work of Jay DeFeo in Tate Papers. With Jo Applin and Amy Tobin she is the co-editor of London Art Worlds: Mobile, Contingent and Ephemeral Networks, 1960-1980 (Penn State University Press, 2018). Catherine has recently been awarded a Philip Leverhulme Research Fellowship for a book project on the relationship between performance art, counterculture and sociology, and will be on research leave from January 2018-September 2019.

Footnotes

-

1

Survey books and exhibitions of post-1945 art in Britain that include Clough focus predominantly on her early realist and figurative studies, and to a lesser extent on the abstract works of the late 1950s and early 1960s. See the entries on Clough in Julian Spalding, ed., The Forgotten Fifties (Sheffield: Graves Art Gallery, 1984); Margaret Garlake, New Art, New World: British Art in Postwar Society (New Haven and London: Yale Univ. Press, 1998); and James Hyman, The Battle for Realism: Figurative Art in Britain during the Cold War, 1945–1960 (New Haven and London: Yale Univ. Press, 2001). Two important publications that span Clough’s longer career are Ben Tufnell, ed., Prunella Clough (London: Tate Britain, 2007), and Frances Spalding, Prunella Clough: Regions Unmapped (Farnham: Lund Humphries, 2012). ↩︎

-

2

Clough lived in London all her life, but visited the east coast regularly. Her family holidayed in Southwold, and in 1945 bought a house there so that the area “remained an important base”. Spalding, Prunella Clough, 50. ↩︎

-

3

Clough’s representation by Juda from 1988 was a success: previously, Juda felt, no one had taken “proper care” of Clough professionally. Juda arrived in Britain from Kassel in Germany, via Palestine, in 1937. She trained as a fashion designer before opening the Molton Gallery in 1960. Annely Juda Fine Art followed in 1968. Annely Juda, interview by Monica Petzal, 12 Feb. 2003, British Library, National Life Stories Collection: Artist’s Lives, C466/151/01–14, tape F14525. ↩︎

-

4

Clough’s Gate paintings were minimalist, mainly black-and-white works based on an abstracted gate motif. The Subway series, which explored the fleeting shadows cast by commuters on the walls of the underground, saw Clough experiment with cellulose on Formica tiles. Prunella Clough: New Paintings 1979–82 (London: Warwick Arts Trust, 1982). ↩︎

-

5

Under Robertson’s tenure at the Whitechapel Art Gallery, Clough had her first retrospective there in 1960. The 1982 show itself “made a great impact, more than any other show since Clough’s Whitechapel exhibition in 1960”. Spalding, Prunella Clough, 193. ↩︎

-

6

The Independent reported that “three-quarters of Prunella Clough’s pictures at Annely Juda were sold four days after the exhibition opened.” Geraldine Norman, “Eager Buyers Snap up ‘New’ Art”, Independent, 1 May 1989, page number unknown, Prunella Clough Papers, Tate Gallery Archive, London (hereafter TGA) 200511/1/2/12. Juda drily remarked: “she always sold a lot. More than she wanted to.” Juda, interview by Petzal, 12 Feb. 2003. ↩︎

-

7

Clough held other well-received exhibitions at Annely Juda in 1993 and 2000, and in 1997 had her first major show outside Britain at the Henie Onstad Art Centre in Oslo. Hilton celebrated the 1993 exhibition as “the talk of the art world”. Tim Hilton, “A Veteran With Youthful Verve”, Independent on Sunday, 19 Dec. 1993, page number unknown, TGA200511/1/2/16. ↩︎

-

8

For many observers, this was the year the jury finally “got it right”. Martin Gayford, “Jerwood Finally Gets it Right”, Daily Telegraph, 22 Sept. 1999, 24. ↩︎

-

9

Patrick Heron, “Prunella Clough: Recent Paintings, 1980–89” (1989), in Prunella Clough, ed. Tufnell, 48. ↩︎

-

10

Tim Hilton, “View from a Corner”, Guardian, 26 April 1989, 46. ↩︎

-

11

Anon., review of Eight Recent Monotypes, London, New Art Centre, 1985, publication unknown, TGA200511/1/2/10. See also, for example, Tim Hilton, “Dreams of Everyday Life”, Independent on Sunday, 3 Oct. 1993, 32, and Sue Hubbard, “The Romance of the Ordinary”, New Statesman 138, no. 4935 (9 Feb. 2009): 44. ↩︎

-

12

Margaret Garlake, “‘Skulpturen Republik’; Prunella Clough”, Art Monthly 126 (May 1989): 21. ↩︎

-

13

Andy Beckett, When the Lights Went Out: Britain in the Seventies (London: Faber, 2009), 15. ↩︎

-

14

Beckett, When the Lights Went Out, 16. ↩︎

-

15

Karl Marx, Capital, trans. Eden and Cedar Paul, 2 vols. (1890; London: J. M. Dent & Sons, 1942), 1: 44. ↩︎

-

16

Heron, “Prunella Clough”, 50. See Malcolm Yorke, “Prunella Clough”, in The Spirit of Place: Nine Neo-Romantic Artists and Their Times (London: Constable, 1988), and Christopher Neve, Unquiet Landscape: Places and Ideas in Twentieth-century English Painting (London: Faber, 1990), 115. ↩︎

-

17

Prunella Clough, cited in Judith Collins, “A Biography”, in Judith Collins, Sacha Craddock, and Isabelle King, Prunella Clough (London: Camden Arts Centre, 1996), 8. ↩︎

-

18

John A. Walker, Left Shift: Radical Art in 1970s Britain (London: I. B. Tauris, 2002), 113. For longer views of alternative art production in Britain since 1970, see Neil Mulholland, The Cultural Devolution: Art in Britain in the Late Twentieth Century (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2003), and Dominic Johnson, ed., Critical Live Art: Contemporary Histories of Performance in the UK (London: Routledge, 2013). ↩︎

-

19

For the links between artistic production in the 1970s and the socio-economic context, see Robert Hewison, Too Much: Art and Society in the Sixties, 1960–1975 (London: Methuen, 1986), and Astrid Proll, ed., Goodbye to London: Radical Art & Politics in the 70s (Berlin: Neue Gesellschaft für Bildende Kunst and Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2010). ↩︎

-

20

See Prunella Clough (Sheffield: Graves Art Gallery, 1972), and Recent Paintings by Prunella Clough (Edinburgh: Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, 1976). ↩︎

-

21

Hilton, “View from a Corner”, 46. ↩︎

-

22

Prunella Clough, “Interview with Bryan Robertson, 1982”, in Prunella Clough, ed. Tufnell, 44. ↩︎

-

23

Robin Banks, “Some Personal Memories”, in Peter Adam, Robin Banks, and Michael Harrison, Prunella Clough: The Late Paintings and Selected Earlier Works (London: Annely Juda Fine Art, 2000), 6. ↩︎

-

24

Sacha Craddock, “Prunella Clough: Paintings”, in Collins, Craddock, and King, Prunella Clough, 20. ↩︎

-

25

Prunella Clough, notebook, ca. 1987, TGA200511/2/1/12. ↩︎

-

26

Marx distinguishes between the use value and exchange value of a commodity, arguing that while sometimes the two are connected there are multiple permutations and distortions of this relation: “for any one commodity there are numerous elementary expressions of value, according as it is brought into a value relation with this or that or the other commodity.” Marx, Capital, 1: 34. ↩︎

-

27

Toypack: Sword appears in the 1989 catalogue, but Clough reported in a 1992 letter: “incidentally a painting called TOY PACK 1989 is no more. . . . It is in process of becoming a different caterpilla [sic] / butterfly?” Clough refers to a work called Toypack, rather than Toypack: Sword, and dates it a year later, but it could be the same work. Prunella Clough, letter to Ian Barker, 14 Oct. 1992, TGA200511/1/2/13 (1 of 2). ↩︎

-

28

Hilton, “View from a Corner”, 46. ↩︎

-

29

Clough, “Interview with Robertson”, 43. ↩︎

-

30

Prunella Clough, diary entry for 4 Feb. 1964 diary, TGA200511/5/19; and diary entry for 4 Jan. 1968, 1967 diary, TGA200511/5/22. Robertson included Clough in a touring exhibition of the United States and Canada entitled New British Sculpture and Painting, in which she “emerged as the star of the show, pre-eminently”. Bryan Robertson, letter to Prunella Clough, 5 Jan. 1967, TGA200511/1/2/4 (1 of 2). ↩︎

-

31

Hilton, “Dreams”, 32. ↩︎

-

32

Lawrence Alloway would periodize the “switch from the figurative to an abstract basis” as “characteristic of the second phase of Pop Art”, arguing that “in 1957, at the ‘Young Contemporaries’ . . . Smith exhibited a painting which was influenced both by Sam Francis and by American popular culture.” Lawrence Alloway, “The Development of British Pop”, in Pop Art, ed. Lucy R. Lippard (1966; London: Thames and Hudson, 1970), 44. ↩︎

-

33

Hal Foster, The First Pop Age: Painting and Subjectivity in the Art of Hamilton, Lichtenstein, Warhol, Richter, and Ruscha (Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press, 2012), 7. ↩︎

-

34

For Riley’s dismay at the fashion industry’s consumption of her designs, see Pamela M. Lee, “Bridget Riley’s Eye/Body Problem”, in Chronophobia: On Time in the Art of the 1960s (Cambridge, MA, and London: MIT Press, 2006). ↩︎

-

35

Prunella Clough, transcript entitled “Prunella Clough and Bridget Riley: A Dialogue”, 7 May, year and venue unknown, 1. Prunella Clough artist’s file, Women’s Art Library (MAKE), Goldsmiths, University of London. ↩︎

-

36

Clough, “Interview with Robertson”, 44. ↩︎

-

37

Spalding traces the importance of Minimalism for Clough’s move towards a more rigorous mode of abstraction in the 1970s, exemplified by Double Diamond (1973). Spalding, Prunella Clough, 179. ↩︎

-

38

Clough, “Interview with Robertson”, 43. ↩︎

-

39

Rachel Whiteread, letter to Prunella Clough, 18 May 1983, TGA200511/1/2/9. Whiteread’s engagement with the legacies of Minimalist abstraction to explore domestic and interior space illuminates Clough’s project in turn. See Briony Fer, On Abstract Art (New Haven and London: Yale Univ. Press, 1997), 153–68. ↩︎

-

40

Joshua Shannon explores the relationship between Judd’s modular, rectangular sculptures of the 1960s and the forms produced by the processes re-making US industry, notably the shipping container and the office: “The sculptures manage to represent not only the forms of the new stage in capitalism but also the logic that those forms endeavoured to naturalize or hide.” Joshua Shannon, The Disappearance of Objects: New York Art and the Rise of the Postmodern City (New Haven and London: Yale Univ. Press, 2009), 180. ↩︎

-

41

Apart from some early lithographs, Clough’s first extended encounter with printmaking came in 1961 when she was invited to the Curwen Studio in London. Spalding, Prunella Clough, 154. See also Prunella Clough: Prints and Works on Paper (London: Flowers Graphics, 2006). ↩︎

-

42

Gerard Hastings, “Prunella Clough: Unconsidered Wastelands”, in Prunella Clough: Unconsidered Wastelands (London: Osborne Samuel, 2015), 11. ↩︎

-

43

Ian Barker, “The Unseen Reliefs of Prunella Clough–A Brief Context”, in Prunella Clough: Unseen Reliefs, Drawings and Prints (London: Annely Juda Fine Art, 2003), unpaginated. ↩︎

-

44

Barker, “Unseen Reliefs”, unpaginated. ↩︎

-

45

Clough showed an undated assemblage entitled Moonwater. Barker, “Unseen Reliefs”, unpaginated. ↩︎

-

46

See David Archer, Prunella Clough & David Carr: Works 1945–1964 (London: Austin/Desmond Fine Art, 1997). ↩︎

-

47

Prunella Clough, letter to David Carr, postmarked 1953, TGA200511/1/1/23/12 (2/4). ↩︎

-

48

Prunella Clough, fragment entitled “paint factory”, undated, TGA200511/1/1/23/78. ↩︎

-

49

Clough, “paint factory”, undated. ↩︎

-

50

Roland Barthes, Mythologies, trans. Annette Lavers (1957; London: Vintage, 2000), 97. ↩︎

-

51

Heron, “Prunella Clough”, 49. ↩︎

-

52

Heron, “Prunella Clough”, 49. ↩︎

-

53

For an overview, see John Wilmerding, ed., The Pop Object: The Still Life Tradition in Pop Art (New York: Acquavella Galleries and Rizzoli, 2013). ↩︎

-

54

Braque was an important reference point for Heron: see “Braque”, The New English Weekly, 4 July 1945, and “The Changing Jug”, The Listener, 25 Jan. 1951, in Painter as Critic: Patrick Heron, Writings 1945–97, ed. Mel Gooding (London: Tate Publishing, 1998), 13–18 and 54–59. ↩︎

-

55

Heron, “Prunella Clough”, 49. ↩︎

-

56

Hanneke Grootenboer proposes that still life is “arguably the most philosophical genre” and a key site for artistic experimentation, noting that “the still lifes of Cézanne are central to Merleau-Ponty’s thought” while the “very first photographs were shots of typical still-life scenes and . . . cubism’s final break with realism developed within a series of still-life paintings.” Hanneke Grootenboer, The Rhetoric of Perspective: Realism and Illusionism in Seventeenth-century Dutch Still-Life Painting (Chicago and London: Univ. of Chicago Press, 2005), 5. ↩︎

-

57

William Packer celebrated Clough as “the heir to Klee and Schwitters”. William Packer, “Prunella Clough”, Financial Times, 21 March 1975, page number unknown, TGA200511/1/2/7. For an overview of artistic engagements with the “everyday” in the twentieth-century, see Ben Highmore, Everyday Life and Cultural Theory (London and New York: Routledge, 2000), and Stephen Johnstone, ed., The Everyday: Documents of Contemporary Art (London: Whitechapel Art Gallery and MIT Press, 2008). ↩︎

-

58

Heron, “Prunella Clough”, 51. ↩︎

-

59

Clough, notebook, ca. 1987. ↩︎

-

60

Juda, interview by Petzal, 12 Feb. 2003. ↩︎

-

61

John Berger, “Machine-Life Painting”, New Statesman and Nation 45, no. 1154 (18 April 1953): 454. ↩︎

-

62

Aspects of these works are reminiscent of Henry Moore’s organic figure studies. Clough took sculpture classes with Moore at the Chelsea School of Art (then part of Chelsea Polytechnic) in the late 1930s. She reflected: “Work under Moore was a deliberate if juvenile exercise in 3 dimensional realisation for the benefit of work in 2–a thing inconceivable to regret.” Clough, diary entry for 21 May 1945, 8 Nov. 1944–28 Nov. 1947 diary, TGA201215/1/1. ↩︎

-

63

Margaret Garlake, “Fishermen and Velvet Kebabs: Prunella Clough’s Subjects”, in Prunella Clough, ed. Tufnell, 96. Clough taught throughout her career, and during her time at Chelsea School of Art still lifes of “red cabbages and suitable objects” were a classroom staple. Prunella Clough, interviewed by Bridget Jackson, date of recording unknown, British Library, National Life Stories Collection: General, C464/44/01, tape F13491. ↩︎

-

64

Prunella Clough, cited in Bryan Robertson, “Happiness is the Light”, Modern Painters 9, no. 2 (Summer 1996): 20. ↩︎

-

65

Berger, “Machine-Life Painting”, 454. ↩︎

-

66

Clough, “Interview with Robertson”, 44. ↩︎

-

67

Berger, “Machine-Life Painting”, 455. See Norman Bryson’s classic study, Looking at the Overlooked: Four Essays on Still Life Painting (London: Reaktion, 1990). ↩︎

-

68

Garlake describes Clough’s mode of still life as a “very idiosyncratic form of the genre”. Garlake, “Fishermen”, 97. ↩︎

-

69

Clough, “Interview with Robertson”, 43. ↩︎

-

70

Clough, “Interview with Robertson”, 43. ↩︎

-

71

Michael Middleton, “Introduction”, in Prunella Clough: A Retrospective Exhibition (London: Whitechapel Art Gallery, 1960), 8. ↩︎

-

72

Clough used the word “urbscape” interchangeably with landscape in her appointment diaries, which combine administrative tasks with brief, Morse code-like lines about the weather and the progress of works. Prunella Clough, diary entry for 11 June, 1958 diary, TGA200511/5/13. ↩︎

-

73

Prunella Clough, letter to David Carr, “Thursday, 6pm”, undated, TGA200511/1/1/23/61 (1/3). ↩︎

-

74

The esteem Clough and Carr had for Lowry is significant given the unevenness of his critical reception. For a valuable revisionist approach, see T. J. Clark and Anne Wagner, Lowry and the Painting of Modern Life (London: Tate Britain, 2013). ↩︎

-

75

Sue Hubbard, “Prunella Clough: Annely Juda”, Time Out, 10–17 May 1989, page number unknown, TGA200511/1/2/12. ↩︎

-

76

For the impact of the microcosmic view on landscape painting in Britain, see Catherine Jolivette, “Growth and Form: The New Landscapes”, in Landscape, Art and Identity in 1950s Britain (Farnham: Ashgate, 2009). ↩︎

-

77

Amanda Sebestyen, untitled review, City Limits, 11–18 May 1989, page number unknown, TGA200511/1/2/12. ↩︎

-

78

For the role played by coastal landscapes in British Surrealism, see Pennie Denton, Seaside Surrealism: Paul Nash in Swanage (Swanage: Peveril Press, 2002). ↩︎

-

79

For a key study of the US context that resonates with changes in Britain, see Daniel Bell, The Coming of Post-Industrial Society: A Venture in Social Forecasting (1973; New York: Basic Books, 1999). ↩︎

-

80

Martin J. Wiener, English Culture and the Decline of the Industrial Spirit, 1850–1980 (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1981), 157. ↩︎

-

81

Prunella Clough, draft statement containing excerpts from the 1982 Robertson interview, ca. 1982, TGA200511/1/2/8 (137/138). ↩︎

-

82

The work can be compared to the paintings Rita Donagh has produced inspired by her childhood in the Midlands, such as Canals (2005). Donagh reflects: “The canals even in decline were very important, with their overgrown towpaths. One had a rich experience of nature, as it reclaimed industrial wasteland.” Rita Donagh, interview with Jonathan Watkins, 21 July 2005, Jonathan Watkins, “Back to the Black Country”, in Rita Donagh (Birmingham: Ikon Gallery, 2005), 7. ↩︎

-

83

John Berger, “Lowry and the Industrial North” (1966), in About Looking (London: Writers and Readers Publishing Cooperative, 1980), 92. ↩︎

-

84

Berger, “Lowry and the Industrial North”, 92. ↩︎

-

85

Clough’s diary for 1973 records that year’s oil shortage, with commentaries such as “crisis crisis” and “fuel and general crisis”. Prunella Clough, diary entries for 6 Dec. and 19 Dec., 1973 diary, TGA200511/5/28. ↩︎

-

86

Drabble’s eponymous novel of industrial decline charts a terrain similar to Clough’s paintings. Drabble’s protagonist Anthony Keating, a property developer, acquires a gasometer: “It was not a very expensive gasometer, for the gas board had abandoned it some years earlier, on the advent of North Sea Gas, but it was a useful site, which would join very neatly onto a brewer’s yard and an old bomb site, and possibly a whole stretch of river frontage.” Margaret Drabble, The Ice Age (1977; London: Penguin, 1978), 31. Clough felt that “a gasometer is as good as a garden, probably better.” Prunella Clough, “Statement”, from “Seven Artists Tell Why They Paint”, Picture Post, 12 March 1949, in Prunella Clough, ed. Tufnell, 21. ↩︎

-

87

Spalding, Prunella Clough, 159. ↩︎

-

88

Douglas Crimp closes his provocative essay “The End of Painting” by anticipating a time in which “the code of painting will have been abolished”. Douglas Crimp, ‘The End of Painting’, October 16 (Spring 1981): 86. ↩︎

-

89

See Thomas McEvilley, The Exile’s Return: Toward a Redefinition of Painting for the Post-Modern Era (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1993), and the texts in Terry R. Myers, ed., Painting: Documents of Contemporary Art (London: Whitechapel Art Gallery and MIT Press, 2011). ↩︎

-

90

Peter Osborne, “Modernism, Abstraction and the Return to Painting”, in Thinking Art: Beyond Traditional Aesthetics, ed. Andrew Benjamin and Peter Osborne (London: Institute of Contemporary Arts, 1991), 72. ↩︎

-

91

Grootenboer, Rhetoric of Perspective, 22. ↩︎

-

92

Clough’s photographs contain images of blister packs, a make-up compact with fold out sections, and, more startlingly, mortuary flowers at a cemetery decaying inside their cellophane wrappings. Prunella Clough, source photographs, undated, TGA200511/4/3. ↩︎

-

93

Before she dedicated herself to painting, Clough produced graphic design work. For examples see Spalding, Prunella Clough, 20. ↩︎

-

94

Fredric Jameson, Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (Durham, NC: Duke Univ. Press, 1991), 9. ↩︎

-

95

See Sven Lütticken, “Living with Abstraction”, Texte zur Kunst 69 (March 2008), in Abstraction: Documents of Contemporary Art, ed. Maria Lind (London: Whitechapel Art Gallery and MIT Press, 2013), and Marshall Berman, All That is Solid Melts into Air: The Experience of Modernity (London: Verso, 1983). ↩︎

-

96

Reviewing Clough’s Whitechapel retrospective, David Sylvester noted: “one suspects the influence of Americans like Rothko, Kline and Motherwell”, but concluded that any influences “are always thoroughly digested”. David Sylvester, “Exhibitions”, New Statesman 60, no. 1542 (1 Oct. 1960): 472. ↩︎

-

97

A list in Clough’s archive juxtaposes “Homebase” (possibly an allusion to the British DIY chain of that name) with words like “downturn”, “rift”, and “baubles”. Prunella Clough, written fragment, undated, TGA200511/2/2/2 (29/39). ↩︎

-

98

Clough, “Interview with Robertson”, 44. ↩︎

-

99

Clough, “Interview with Robertson”, 44. ↩︎

-

100

Clough, “Clough and Riley”, 2. ↩︎

-

101

Helen Molesworth, “Painting with Ambivalence”, in WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution, ed. Lisa Gabrielle Mark (Los Angeles: Museum of Contemporary Art, 2007), 434. ↩︎

-

102

The examples are too many to list in their entirety. A couple suffice: Edward Lucie-Smith detected a “lack of ambition” in Clough’s work, despite the fact that he was writing after her major Whitechapel retrospective of 1960. Edward Lucie-Smith, “Round the Art Galleries: Reality and Style”, The Listener 1854 (8 Oct. 1964): 556. John Russell bestowed a particularly sexist backhanded compliment: “where scale is concerned there is a ‘recommended maximum’ above which women’s art decreases very sharply in its effectiveness. Someone who knows this and does not go outside her own best capacities is Prunella Clough.” John Russell, untitled clipping, Sunday Times, 31 March 1968, page number unknown, TGA200511/1/2/4 (2 of 2). ↩︎

-

103

For the dangers attendant on applying a biographical lens to women’s art, see Anne Wagner, Three Artists (Three Women): Modernism and the Art of Hesse, Krasner and O’Keeffe (Berkeley and Los Angeles: Univ. of California Press, 1996). ↩︎

-

104

As early as 1966 Clough was held up as one of the “few really influential women” artists who had overcome institutional prejudices. Fiona MacCarthy, “Fiona MacCarthy talking about Women Artists”, Guardian, 28 Feb. 1966, 6. Monica Petzal noted that Clough, together with Gillian Ayres, “represented for several generations of younger women artists–including myself–the most invaluable of role-models”. Monica Petzal, “Prunella Clough, Gillian Ayers”, unknown publication, ca. 1982, TGA200511/1/2/8 (25/138). For the gender politics of Clough’s reception, see Joan Key, “The Metamorphosis of Attrition”, Women’s Art Magazine 70 (June–July 1996): 5–7. Clough’s aunt, the designer and architect Eileen Grey, provided a role model that “did allow for other possibilities”. Clough, “Clough and Riley”, 2–3. ↩︎

-

105

Margaret Drabble, “A Floating World”, New Statesman 133, no. 4677 (1 March 2004): 39. ↩︎

-

106

Hastings, “Unconsidered Wastelands”, 12–13. ↩︎

-

107

Prunella Clough, Small Stack postcards, TGA200511/3/1/2/1–41. ↩︎

-

108

For the intersection of seriality and abstraction in the late twentieth century, see Briony Fer, The Infinite Line: Re-Making Art After Modernism (New Haven and London: Yale Univ. Press, 2004). ↩︎

-

109

David Joselit’s exploration of contemporary painting’s ‘networked’ qualities addresses a different context (New York in the 2000s) but is suggestive here. See David Joselit, “Painting Beside Itself”, October 130 (Fall 2009): 125–34. ↩︎

-

110

Theodor W. Adorno, Aesthetic Theory, ed. Gretel Adorno and Rolf Tiedemann, trans. Robert Hullot-Kentor (1970; London: Bloomsbury, 2013), 310. ↩︎

Bibliography

Primary

Jackson, Bridget. Interview with Prunella Clough. Date of recording unknown. British Library, National Life Stories Collection: General, C464/44/01.

Petzal, Monica. Interview with Annely Juda. 12 Feb. 2003. British Library, National Life Stories Collection: Artist’s Lives, C466/151/01–14.

Prunella Clough Papers, 200511 and 201215. Tate Gallery Archives, London.

“Prunella Clough and Bridget Riley: A Dialogue.” Transcript. 7 May, year and venue unknown. Prunella Clough artist’s file, Women’s Art Library (MAKE), Goldsmiths, University of London.

Secondary

Adorno, Theodor. Aesthetic Theory. Ed. Gretel Adorno and Rolf Tiedemann, trans. Robert Hullot-Kentor. 1970; London: Bloomsbury, 2013.

Alloway, Lawrence. “The Development of British Pop.” In Pop Art. Ed. Lucy R. Lippard. 1966; London: Thames and Hudson, 1970, 27–67.

Archer, David. Prunella Clough & David Carr: Works 1945–1964. London: Austin/Desmond Fine Art, 1997.

Banks, Robin. “Some Personal Memories.” In Robin Banks, Michael Harrison, and Peter Adam, Prunella Clough: The Late Paintings and Selected Earlier Works. London: Annely Juda Fine Art, 2000, 5–8.

Barker, Ian. “The Unseen Reliefs of Prunella Clough—A Brief Context.” In Prunella Clough: Unseen Reliefs, Drawings and Prints. London: Annely Juda Fine Art, 2003, unpaginated.

Barthes, Roland. Mythologies. Trans. Annette Lavers. 1957; London: Verso, 2000.

Beckett, Andy. When the Lights Went Out: Britain in the Seventies. London: Faber, 2009.

Bell, Daniel. The Coming of Post-Industrial Society: A Venture in Social Forecasting. 1973; New York: Basic Books, 1999.

Berger, John. “Lowry and the Industrial North” (1966). In About Looking. London: Writers and Readers Publishing Cooperative, 1980, 87–95.

– – –. “Machine-Life Painting.” New Statesman and Nation 45, no. 1154 (18 April 1953): 454–55.

Berman, Marshall*. All That is Solid Melts into Air: The Experience of Modernity*. London: Verso, 1983.

Bryson, Norman. Looking at the Overlooked: Four Essays on Still Life Painting. London: Reaktion, 1990.

Clark, T. J., and Anne Wagner. Lowry and the Painting of Modern Life. London: Tate Britain, 2013.

Clough, Prunella. “Interview with Bryan Robertson, 1982.” In Prunella Clough. Ed. Tufnell, 43–45.

– – –. “Statement” from “Seven Artists Tell Why They Paint.” Picture Post, 12 March 1949. In Prunella Clough. Ed. Tufnell, 21.

Collins, Judith. “A Biography.” In Judith Collins, Sacha Craddock, and Isabelle King, Prunella Clough. London: Camden Arts Centre, 1996, 5–9.

Craddock, Sacha. “Prunella Clough: Paintings.” In Judith Collins, Sacha Craddock, and Isabelle King, Prunella Clough. London: Camden Arts Centre, 1996, 15–22.

Crimp, Douglas. “The End of Painting.” October 16 (Spring 1981): 69–86.

Denton, Pennie. Seaside Surrealism: Paul Nash in Swanage. Swanage: Peveril Press, 2002.

Drabble, Margaret. “A Floating World.” New Statesman 133, no. 4677 (March 2004): 38–39.

– – –. The Ice Age. 1977; London: Penguin, 1978.

Fer, Briony. On Abstract Art. New Haven and London: Yale Univ. Press, 1997.

– – –. The Infinite Line: Re-making Art After Modernism. New Haven and London: Yale Univ. Press, 2004.

Foster, Hal. The First Pop Age: Painting and Subjectivity in the Art of Hamilton, Lichtenstein, Warhol, Richter, and Ruscha. Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press, 2012.

Garlake, Margaret. “Fisherman and Velvet Kebabs: Prunella Clough’s Subjects.” In Prunella Clough. Ed. Tufnell, 95–109.

– – –. New Art, New World: British Art in Postwar Society. New Haven and London: Yale Univ. Press, 1998.

– – –. “‘Skulpturen Republik’; Prunella Clough.” Art Monthly 126 (May 1989): 20–21.

Gayford, Martin. “Jerwood Finally Gets it Right.” Daily Telegraph, 22 Sept. 1999, 24.

Gooding, Mel, ed. Painter as Critic: Patrick Heron, Writings, 1945–97. London: Tate Publishing, 1998.

Grootenboer, Hanneke. The Rhetoric of Perspective: Realism and Illusionism in Seventeenth-century Dutch Still-Life Painting. Chicago and London: Univ. of Chicago Press, 2005.

Hastings, Gerard. “Prunella Clough: Unconsidered Wastelands.” In Prunella Clough: Unconsidered Wastelands. London: Osborne Samuel, 2015, 11–15.

Heron, Patrick. “Prunella Clough: Recent Paintings 1980–89” (1989). In Prunella Clough. Ed. Tufnell, 47–51.

Hewison, Robert. Too Much: Art and Society in the Sixties, 1960–1975. London: Methuen, 1986.

Highmore, Ben. Everyday Life and Cultural Theory. London and New York: Routledge, 2000.

Hill, Emma, and others. Prunella Clough. Cambridge: Kettle’s Yard Art Gallery, 1999.