Composing

Composing

Interview with Robert Bentall

Abstract

Composer Robert Bentall speaks with the British Art Studies editorial team about the score he wrote for Impermanence’s The Ballet of the Nations. How was the composition shaped by sampling the sonic textures of the period? What musical information is contained within Vernon Lee’s original 1915 text, and how did it influence Bentall’s score?

Interview

BAS: How did you come to score The Ballet of the Nations?

Rob: In May 2017, I collaborated with Impermanence on the research and development phase of an adaptation of Baal, the first play by Bertolt Brecht. The collaboration was very successful, after which Joshua and Roseanna discussed The Ballet of the Nations project with me, suggesting that my music might fit the film. They subsequently invited me to meet Grace in November of that year. She talked us through the historic background of Vernon Lee’s text, of which I knew very little. I was fascinated by Grace’s description of the text, and Lee’s life more broadly, and was keen to be involved. I came at the project from the angle of a creative practitioner who had some experience working with dancers, and was seeing the historic material for the first time.

BAS: Can you describe your practice prior to Baal? Had you made music for a dance production before?

Rob: No, my earlier compositional work was as a solo artist and stemmed from my practice as an electroacoustic composer, which developed during my doctorate at the Sonic Arts Research Centre at Queen’s University, Belfast. I was writing fixed-media electronic music, exploring themes of genre hybridisation by blending elements of folk, ambient, pop, and musique concrète styles within multichannel surround sound compositions. In 2015, during a period supported by the charity Sound and Music through their Embedded Composer scheme, I started writing pieces for the nyckelharpa, a Swedish 16-stringed traditional fiddle, combined with electronic sound (fig. 1). I had also begun collaborating on interdisciplinary projects—I worked with Knaïve Theatre on a production of Karel Čapek’s War with the Newts, and with video artist Heather Lander on an audio-visual piece titled Nearer Future.1

1

BAS: How did the elements of collaboration and dance in The Ballet of the Nations change your approach to composing?

Rob: My composing for The Ballet of the Nations was driven firstly by the text, which is quite an unusual process. It isn’t standard practice to score a film without having seen a cut of the video first. But all of us—in choreography, cinematography—were working on the same premise, which was thinking about Vernon Lee, and examining the quirks and intricacies of the text as a starting point for a creative piece. So, my first ideas for the sound were extracted from The Ballet of the Nations text. It’s a rich source of sonic information; there are many instruments described as being performed by the cast of Human Passions, including the harmonium, pianola, woodland horn, and bass—all of these appear in the score. Some of the music, notably the sections for the Smallest Dancer, was written during the filming process.

The elements of dance also do change my approach to composing. When working on something for Impermanence, I am often thinking about textures or rhythms that might work alongside choreography. Working on a film was slightly different again—I was considering, in the score that some sections might want to be more muted, in order to let the dialogue sing through.

BAS: Joshua and Roseanna have described how deeply Grace’s research shaped the choreography. Did that context inform the film’s sound, as well?

Rob: Absolutely. I spoke with Grace about composers whose music was often scored for dance and ballet contemporary with Vernon Lee, and from around the time that Lee wrote The Ballet of the Nations, even if removed from her specific milieu. I fixated on that period, from 1914 to 1918, and Grace mentioned the work of a composer named Eugene Goossens, of whom I knew very little. His Kaleidoscope Suite (1917) for orchestra intrigued me with its rich, expressive opening chords. The opening scenes of the film, where Grace appears as Vernon Lee and describes the proverbially bourgeois Victorian age, are scored by computer manipulations of this composition. This music is constructed from a sample of one chord in the opening sequence of the Kaleidoscope Suite, which has been extended in length by approximately one thousand times via computer processing. The chord is then surrounded by an arrangement I made, featuring primarily double bass and bassoon sections suggesting harmonic changes against the static chord derived from Goossens.

BAS: You mentioned your academic training—what is your own research process like?

Rob: First, research is a process of listening. It’s trawling through musical works to find appropriate material for use in a project; in this case, music relevant to dancing and to the period itself. Often research involves locating sounds lost, forgotten, or out of fashion. Second, research is practice—finding new combinations of timbres through arrangement, and examining how old and new technologies can be combined musically. As I mentioned before, for The Ballet of the Nations, I also explored links between text and music by extracting sonic material referenced directly in the prose.

BAS: Did you use a lot of samples for the soundtrack?

Rob: Absolutely, if you define sampling as reusing musical material from works created by other artists. One noticeable example in the score is my sampling of a song titled “Kaval Sviri” by the Bulgarian State Television Female Choir (fig. 2) . I was looking to score the chorus sections of the dancers that appear at several points in the film, and Roseanna suggested something musically related to a “chorus”. Singing of any sort was not mentioned by Lee, so I had free rein.

Eventually, I found this tune and slowed it down to half its speed in a digital sampler, added a synthesiser part, and looped a few of the sections I particularly liked so you never hear the whole track. It’s basic language, and the sense of a powerful chorus is still there, but the harmonies feel more exposed given how long they take to elapse.

Another key sample is taken from Debussy’s Poisson d’or (1907). I chose five piano chords, reordered them, and manipulated them to sound very distant, as if from within an ecclesiastical space (fig. 3). The track jumped out at me because Grace found it had been used in the Chelsea theatres at the turn of the century.

BAS: How does that sit with being a composer of electronic music and sound?

Rob: Sampling is inherent to my recent working process; I often transform and reuse material from my own work, as well as from earlier pieces by other artists. Sampling often sits alongside digital processing, which changes the duration, texture, or timbre of the original sound. And of course, it’s in conjunction with sounds I record and produce myself.

BAS: Sampling older material is quite interesting in relation to this project—Vernon Lee is not exactly a household name in the way that First World War poets like Wilfred Owen are, and pulling sounds out of the archive to give them new relevance seems like another facet of this approach.

Rob: Yes, there is a natural sympathy there. The internet, with resources such as YouTube and Spotify, has made an impossibly large archive of musical information very easy to access. It’s easier to find things that you might otherwise never have discovered, but there is still far more than a listener will ever get through. The score—drawing upon Bulgarian choirs, instruments in the text, Russian folk songs, and the Swedish nyckelharpa—very much functions as a little archive of my musical inspirations during this project.

BAS: Is there a written score for electronic music?

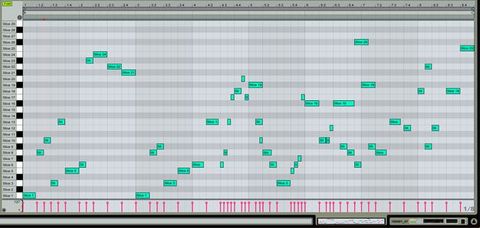

Rob: Not as a score with notation in the Western classical sense. Instead, you can visualise the score as a series of layered sound clips organised in Ableton Live, my chosen software. Coloured rectangles each represent a different block of sound (fig. 4) and some notes can be represented within a digital piano roll (fig. 5). The sounds in the score are either played into the computer with a MIDI controller (fig. 6) or a MIDI keyboard (fig. 7).

BAS: You mentioned that several historic instruments are used in the score. Can you describe a few examples?

Rob: In the first half of the film, I drew on the sound worlds of the text itself, which mentions instruments including the harmonium, the woodland horn, the double bass, and the pianola. The harmonium plays a key role—it features prominently in the score when Ballet Master Death is starting the dance. For me, its sound conjures up a sort of infernal metallic quality that suits the scene. The harmonium presents an obsessive three-chord figure that mutates through a few stark modulations. You get a sense of pulsation and energy as the film’s narrative announces the start of war. I don’t play the harmonium that well, but got what I needed to score the film. This is in opposition to the nyckelharpa, which is a key part of the score and my musical practice more generally. The pianola, or player piano, is also an unusual instrument to use in a score. For this sound, I used a mixture of piano and synthetic harpsichord timbres to generate a somewhat tinny keyboard sound that features prominently in a section of the choreography where the Nations dance together in formation (fig. 8).

BAS: In that process of honing a sound, how many drafts or iterations might exist for a section like this?

Rob: It varies. The harmonium-led music came out very naturally and only featured minor changes from my first draft to the third and final one. The final version, which came about as Joshua and Roseanna were looking at the cut, involves a sharp silence when the Ballet Master waves his wand to create a pause—I learned a lot about linking dramatic effects in sound and picture whilst the film was being edited (fig. 9).

BAS: Did you introduce any new instruments to the sonic world that Vernon Lee describes?

Towards the end of the film, I drew more on my own creative practice with the introduction of the nyckelharpa, which is an 800-year-old 16-stringed Swedish traditional keyed fiddle.2 The sound is very resonant, thanks to its twelve sympathetic strings. I discovered it whilst doing artistic residencies in Sweden in 2013–14 and started learning it soon after. In Lee’s text, and in the film, Satan describes the music for the ballet as being simultaneously too archaic and ultramodern, which I think the nyckelharpa articulates perfectly. It’s an ancient instrument that sounds surprisingly modern to my ear. I play it as an improvising contemporary musician, having also learnt some traditional performance techniques. For The Ballet of the Nations, I wrote some new melodies for the nyckelharpa, which are very present in the latter-half of the score. There are multiple recordings of the instrument layered on top of each other.

2BAS: You were on set for the filming—what impact did seeing the dancing, on location, have on your choices for the sound?

Rob: Certain scenes were shot at Sandham Memorial Chapel, which has a mural cycle painted by Stanley Spencer commemorating the dead of the First World War. I had already composed some music for those sequences, but I took the nyckelharpa with me, and in the space, my ideas changed. My first sensation was of being overwhelmed and I was especially struck by the wall showing a mass of crosses. Listening to the acoustics of the space, I also wondered if the music I had planned originally would feel dense. So I got the instrument out and wrote something quickly, improvising around a new melody (fig. 10). In the editing phase, I wove this new music around Satan’s speech in the chapel, creating a kind of call and response between the instrument and Satan’s dialogue and movement (fig. 11).

BAS: Are resonance and that emotional quality connected?

Rob: For me, the resonant quality of liturgical spaces is very emotive. I love hearing instruments played in churches and cathedrals. The intense resonance of the nyckelharpa makes it sound as if it’s always being played in a chapel, and I find it elicits a real emotional and physical response. I hope this enhances the drama of the film, and conveys some aspect of my affective experience of making music to its viewers.

BAS: Sometimes it seems that the music you wrote complements the dance very closely. How much did you have to consider synchronising with the dancers, in a technical sense?

Rob: The score’s ability to punctuate the dance really came about through my time spent on set, watching the action and the choreographed sections come to life. I could write music accordingly, or alter the tempo of music I’d already written to match the scenes better. But we also worked the other way around—the choreography for the section at 24:45 in the film is sequenced to music I wrote before filming. The process was collaborative, and on set I was tinkering with compositions, describing the score I envisioned, or just cogitating—watching the dancers and actors, and examining how they moved and spoke. All of that observation filtered into the final result."

About the author

-

Robert Bentall is a composer and performer working with electronic sound and live instruments. His works, which have been presented across Europe as well as in North, Central, and South America, hybridise ambient, folk, improvised, and experimental music. Rob completed a PhD in 2015 at the Sonic Arts Research Centre, Queen’s University Belfast, under the supervision of Dr Paul Wilson and Dr Simon Waters. He received the P.J. Leonard Prize for Composition from the University of Manchester, and is one of Sound and Music’s “New Voices”. He has collaborated with artists including Impermanence (UK), Knaïve Theatre (UK), Heather Lander (USA), and CMMAS (Centro Mexicano para la Música y las Artes Sonoras (Mexico) on a variety of interdisciplinary projects.

Footnotes

-

1

Nearer Future, for nyckelharpa, electronics and video, has documentation here: https://vimeo.com/247005482. ↩︎

-

2

A high-quality video of the nyckelharpa playing traditional Swedish music can be heard here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WwCEl4Y8fDk. ↩︎

Imprint

| Author | |

|---|---|

| Date | 29 March 2019 |

| Category | Interview |

| Review status | Peer Reviewed (Editorial Group) |

| License | Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) |

| Downloads | PDF format |

| Article DOI | https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-11/composing |

| Cite as | Bentall, Robert. “Composing.” In British Art Studies: Theatres of War: Experimental Performance in London, 1914–1918 and Beyond (Curated by Grace Brockington, in Collaboration with Impermanence, with Contributions from Ella Margolin and Claudia Tobin). London and New Haven: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art and Yale Center for British Art, 2019. https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-11/composing. |