Costumes and Production

Costumes and Production

Interview between Ella Margolin And Pam Tait

Abstract

Production designer Pam Tait speaks with Ella Margolin about the costumes and set design of Impermanence’s The Ballet of the Nations. How did the specifics of Vernon Lee’s text and Maxwell Armfield’s illustrations influence the look and feel of Tait’s costumes, and how were aspects of visual culture across different periods used to characterise the players?

Interview

Ella: At what point did you first become involved in The Ballet of the Nations?

Pam: I heard about it around six months before we started. By the time we got the Arts Council grant, I had read Vernon Lee’s text and had a good think—and that long lead-in was very valuable.

Ella: What sort of brief were you given?

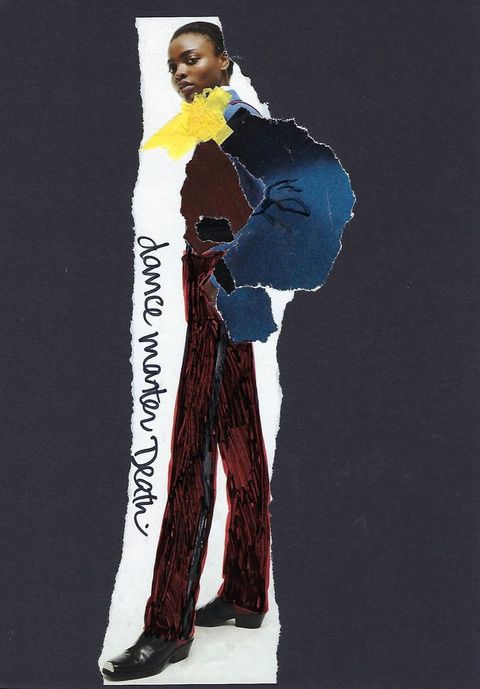

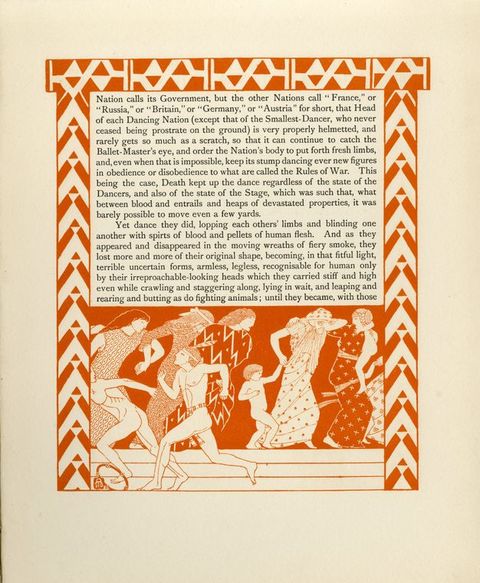

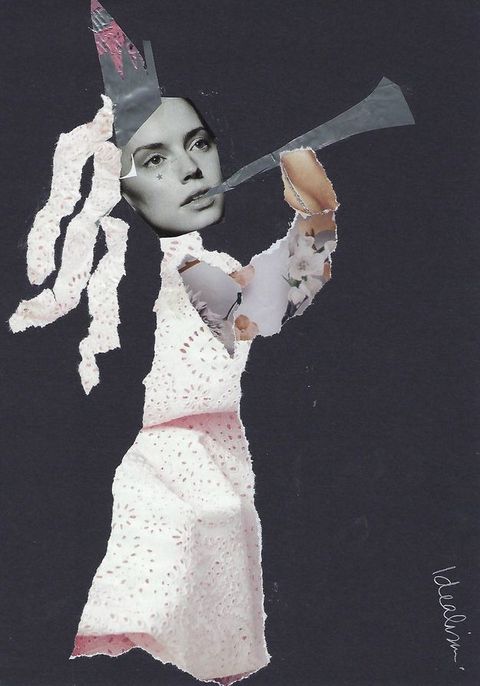

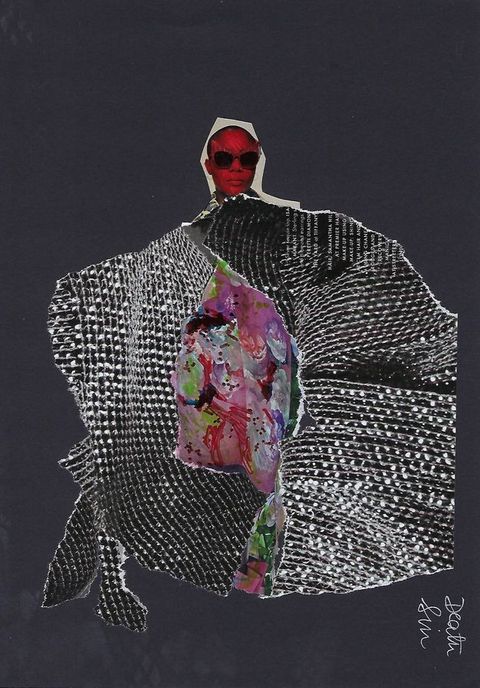

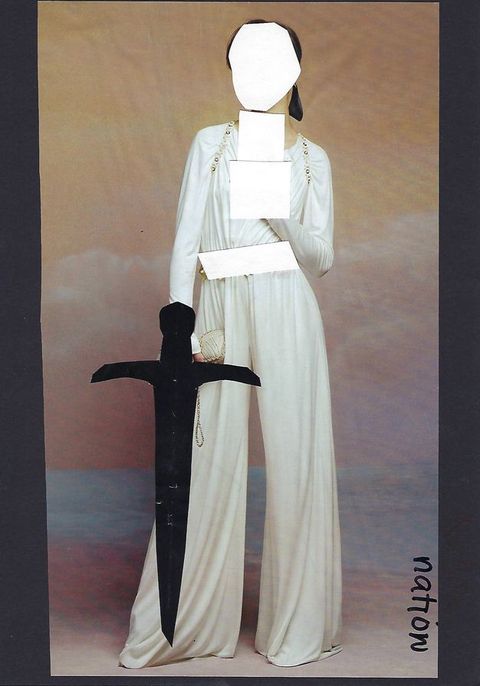

Pam: We had an enormously productive first meeting with Grace. She gave us a lot of context and enshrined certain things before we started: that there should be costumes with patterning all over, in the manner of Maxwell Armfield’s illustrations to The Ballet of the Nations—he was drawing here on his own practice as a costume designer; that the Nations should be in paper costumes, because they would have to tear each other to shreds; and that there should be references to “classical, medieval, biblical or savage costumes”, as Lee specifies in the text (fig. 1, fig. 2, and fig. 3). We were closely following the text.

Ella: Alongside the text, did any particular visual source material inspire the costumes?

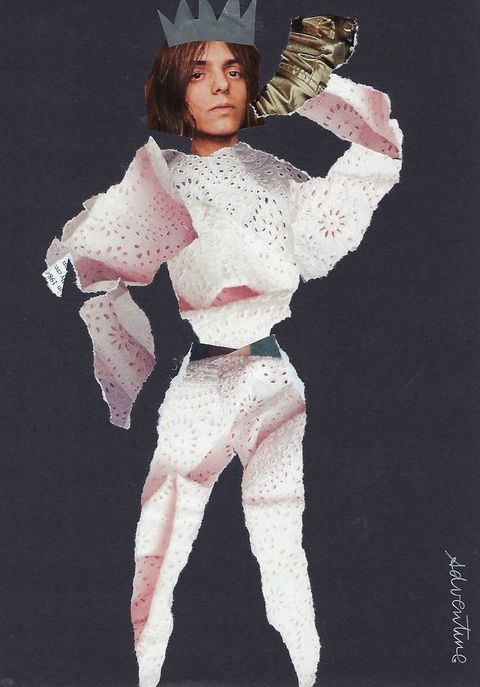

Pam: I teach costume history, and it was lovely to make things drawing on that knowledge. With Self-Righteousness, for instance, I was quite anxious to invoke some of the context of 1910, and thought about whom Vernon Lee would have looked back to as being self-righteous. The great religious controversies came to mind, and the preachers who earned hundreds and thousands of pounds in the 1870s, so I looked to the 1880s. Idealism and Adventure had to be medieval because in the text they are “very magnificent” and “of noblest bearing, if a little over-dressed” and they carry a silver trumpet and a woodland horn (fig. 4 and fig. 5). The Nations are of course modelled after chess pieces, and the shape of the hats they wear is taken from the very earliest hood that was ever made in, I don’t know, the twelfth century. So, it was like a jigsaw. Often nobody will know the references, but I like having some consonance between the layers, like in music, a theme that goes through. That is rather delicious for people, if they do notice.

Ella: How did you go about designing the costumes?

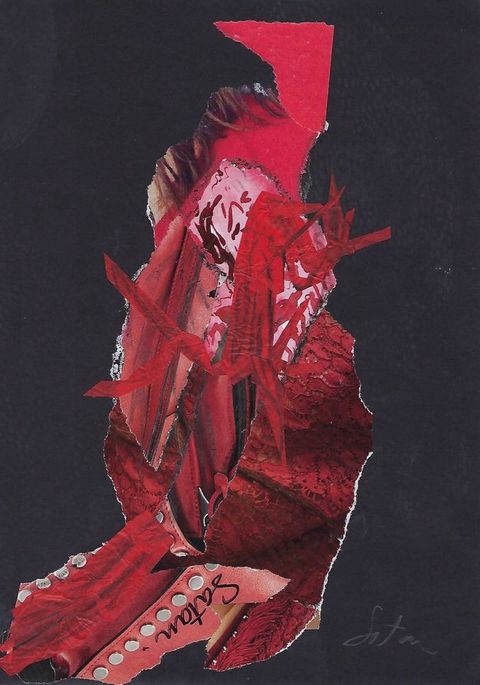

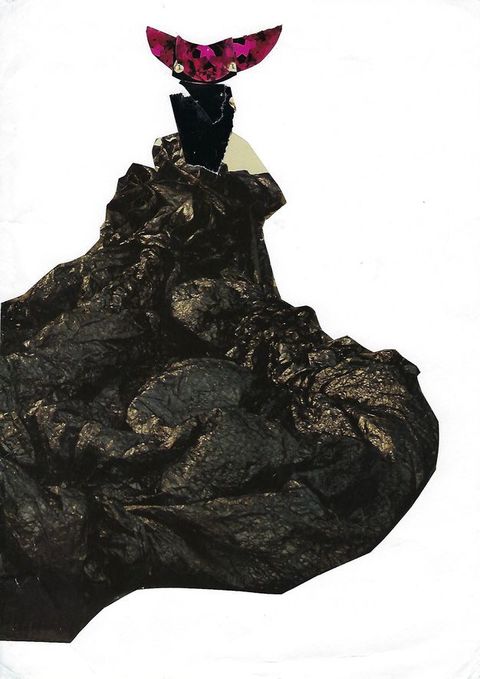

Pam: Well, for Satan, there is a line about the delicate metal tracery of his wings. I was very keen on representing that, and wanted to use melted bin bags because you can get them to resemble lace or wrought iron.

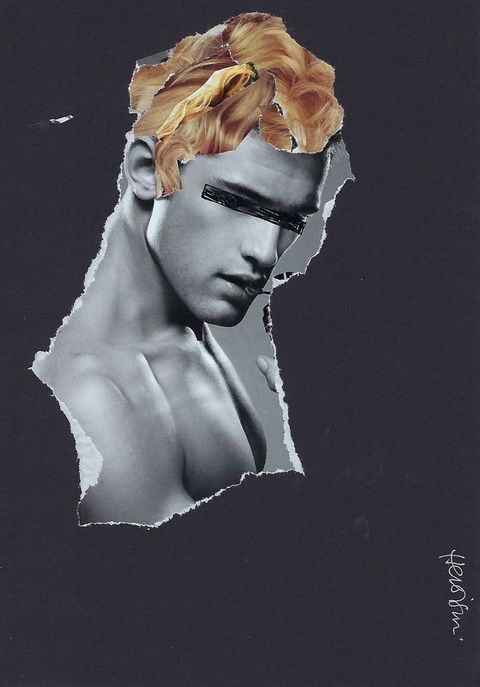

Originally, I was going to put Satan in a red under-gown with melted bin bag feathers on top (fig. 6). But because it was Sonya, who is very delicate, it seemed ridiculous to put her in red. It wouldn’t suit her colouring. Then you inevitably fall into evening wear, so she ended up being armoured because I wanted that thread running through the costumes, linking Satan to Idealism and Adventure (fig. 7, fig. 8, and fig. 9). But I had to wait for the casting of both Satan and Death, because the character of the actor would necessarily dictate the costume, which is why they changed a lot between sketches and the final version (fig. 10 and fig. 11).

Ella: Your process sounds similar to how Rob approaches composing, and even Impermanence choreography—quoting sources, deconstructing and then reconstructing them …

Pam: Yes, absolutely. When you put good roots down, you get a good result. It is easy to be led astray but you have to be the still centre. You have to see the text and vision coming together.

Ella: Did attending the rehearsals influence your work?

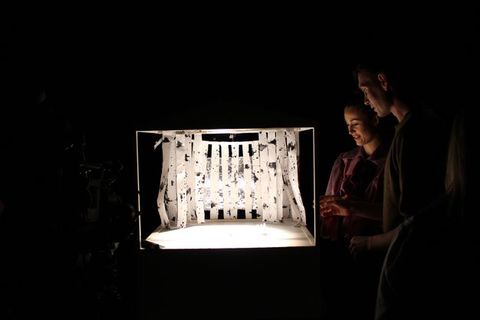

Pam: I always like to be in rehearsal because there are practical elements that come out of it. You can propose a costume but dancers will always want their waists to show, so they immediately put waistbands on the Nations’ costumes; and then you discover that their hats fall back or that the costumes are too hot (fig. 12). At one point, I noticed a big mistake with the set. I thought we would use paper trees, which is ludicrous because there was loads of dancing going on, so I just went out and bought 54 metres of white nylon and painted it in one day (fig. 13, fig. 14, and fig. 15).

Ella: After the filming was done, what changed as a result of the edit?

Pam: In watching the rough cut, the chorus dancing—which you would imagine would be the cream of the crop—actually faded into the distance. Joshua and Roseanna had chosen a deliberately contextless black studio and white studio, and when those appear alongside scenes with plentiful context, they can just disappear. The film is kind of like a painting, or several paintings, and it works on different levels. The trick is how you control those levels. When the rough cut came, because it hadn’t been graded yet, all the costumes became kind of treacly and sepia. I was frustrated because they are intentionally quite strong colours: Pompeian, Roman, and Greek colours. I was really concentrating on getting that balance of colours, and limiting them. There are so many layers to the story. You have intimate conversations between Satan and Death, which are kind of arch and Edwardian and a bit difficult to understand. You have the dancing, the Dietrich, the classical chorus, and the orchestra, so the film is not consistent.

Ella: Do you think that your clothing influenced their dance?

Pam: Yes, Impermanence are really responsive. I always like to play with the kinetic effect of the costume and how it can become part of the dance, which doesn’t come naturally to a dancer because they’ve spent their lives in leotards showing every inch of skin. And of course, it is very important in dance to see the line of the under arm and the waist because that orientates you to what that dancer is doing. But Impermanence are so versatile, you can push them. It is just gravy to watch somebody inhabit a costume and push it—I think a good costume will always take the performer beyond their comfort zone.

About the authors

-

Ella Margolin is an undergraduate student of History of Art at the University of Bristol. With a background in Fine Art, her practice includes photography, film-making, ceramics, and drawing. Alongside her studies she makes videos for local musicians, runs a small pottery enterprise called Loner Ceramics, and hosts arts events in Bristol under the name Big Stink.

-

Pam Tait has worked as a costume designer in theatre, film, and television since graduating from Oxford University. From 2000 to 2013, she was a Visiting Lecturer at the Bristol Old Vic Theatre School. She is a Teaching Fellow in the Drama Department at the University of Bristol and is now concentrating her energies on collaborations in dance theatre and dance film.

Imprint

| Author | |

|---|---|

| Date | 29 March 2019 |

| Category | Interview |

| Review status | Peer Reviewed (Editorial Group) |

| License | Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) |

| Downloads | PDF format |

| Article DOI | https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-11/costumes |

| Cite as | Margolin, Ella, and Pam Tait. “Costumes and Production.” In British Art Studies: Theatres of War: Experimental Performance in London, 1914–1918 and Beyond (Curated by Grace Brockington, in Collaboration with Impermanence, with Contributions from Ella Margolin and Claudia Tobin). London and New Haven: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art and Yale Center for British Art, 2019. https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-11/costumes. |