Cumbrian Cosmopolitanisms

Cumbrian Cosmopolitanisms: Li Yuan-chia and Friends

By Hammad Nasar

Abstract

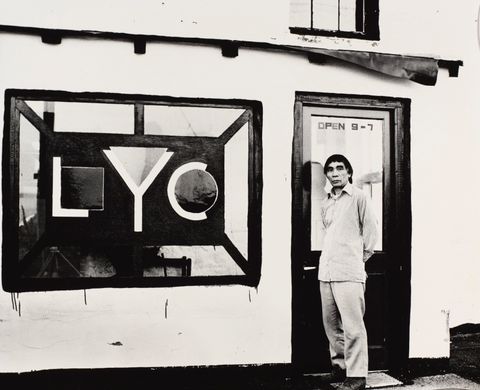

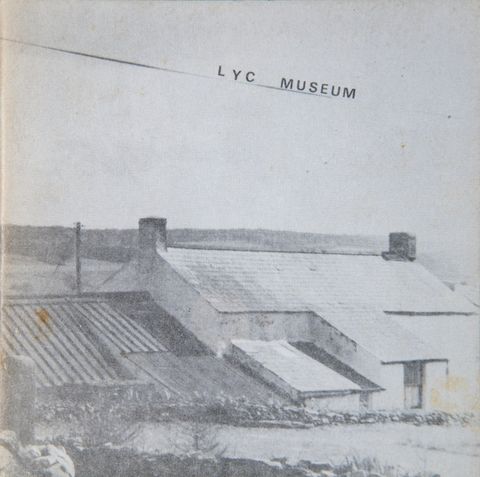

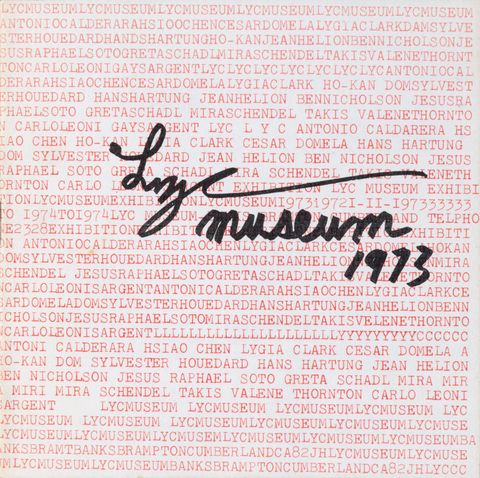

The LYC Museum & Art Gallery (the LYC) in the Cumbrian village of Banks (astride Hadrian’s Wall) was the single-minded effort of artist Li Yuan-chia (1929–1994). His initials gave the museum its name. It was sited in a set of converted farm buildings that Li had bought from his friend, the painter Winifred Nicholson. Between 1972 and 1983, the museum showcased the work of more than 320 artists—from local artists (Andy Christian, Susie Honour) to totemic national figures (Paul Nash, Barbara Hepworth), and contemporary artists, now of international renown (Lygia Clark, Andy Goldsworthy), but then barely known in Britain. A young David Nash designed the LYC’s window. The programme reflected Li’s circuitous cosmopolitanism, his commitment to art as experimentation, and his expansive range of interests: the LYC had a children’s room, library, performance space, printing press, communal kitchen, and a garden. The networks and practices that the LYC enabled and enriched have yet to be studied widely, but it is an exemplary site from which to explore how friendships inform shared practices, generate work, and socialise narratives; and, how the LYC itself functioned as a kind of infrastructure. This article is anchored in the recent exhibition Speech Acts: Reflection-Imagination-Repetition (Manchester Art Gallery, 2018–2019) and its accompanying symposium The LYC Museum & Art Gallery and the Museum as Practice (2019). It explores the idea of “friendship”, and to a lesser extent that of “infrastructure”, through the lens of three works in the Speech Acts exhibition. It forms part of an ongoing collective effort towards inquiries that cross disciplinary and geographic borders, and test polyphonic, multi-authored, and speculative approaches that I have described elsewhere as “art histories of excess”. It invites methodological reflections on the forms and possibilities for conducting and staging collaborative research, and on wider questions of how historic entanglements have the potential to expand existing histories of British art.

The Entangled Histories and Practices of Li Yuan-chia

In the last few years, the work of the Chinese-born artist Li Yuan-chia (1929–1994) has featured in two very different exhibitions on two continents—in two national institutions that could both claim him as their own. In Taiwan, the Taipei Fine Art Museum (TFAM) did just that with an expansive posthumous retrospective, Viewpoint: A Retrospective of Li Yuan-chia (2014), that positioned him as the “father of conceptual and abstract art in Taiwan” (fig. 1).1 It traced his practice over five decades and was accompanied by a luxurious, four-volume catalogue replete with commissioned essays, archival material, and even a replica of Li’s magnetised “toy” works. Li, however, remains largely unrecognised in Britain—his home from 1966 until his death in 1994.2

1

His was a small presence in Tate Britain’s Migrations: Journeys into British Art (2012) exhibition (fig. 2). Its accompanying catalogue carried no illustrations of Li’s works, and framed his expansive artistic practice through the restrictive lenses of calligraphy and abstraction; and privileged biography and geography in positing his contribution to British art, alongside Kim Lim’s, as “fusing far Eastern and Western philosophies and art practices”.3 A recent display at Tate Modern (2015) was slightly more expansive and introduced a wider range of works (Figs 3, 4, and 5). But his work was entirely absent from Tate Britain’s Conceptual Art in Britain 1964–1979 (2016) and is unaccounted for in the generally circulating institutional and academic histories of art in Britain.

3This is at least partly due to the distinctive genealogy of Li’s work that resists attempts to categorise it with a singular label. He drew liberally from modernist, Zen Buddhist and Daoist practices to explore ideas of space, life, and time. The initial vehicle for his explorations was “the Point”—the “Origin and the End of Creation”.4 Originally, a spot of colour or mark in monochromatic paintings and reliefs, it eventually took the form of magnetised objects that could be moved around on metallic discs. He called these magnetic works “toys”, inviting active audience participation.

4Li’s interests and experiments with form were shaped by, and reflect, the zigzagged trajectories of his life. Born in Guangxi, China, Li moved to Taiwan in 1949, where he was part of the Ton-Fan Group of artists experimenting with abstraction. In 1962, he moved to Bologna, where he was associated with the Punto Group of artists. An invitation to show at Signals Gallery brought him to London in 1966. In London, between 1967 and 1970, Li had three solo exhibitions and participated in three group exhibitions at the Lisson Gallery. Artists he showed with included Ken Cox, Mira Schendel, Derek Jarman, and Ian Hamilton Finlay. But London’s regard for Li was not wholly reciprocated; a trip to his friend Nick Sawyer’s family house in Cumbria (Boothby) for Christmas in 1967, saw him settle in nearby Bankside.

The retrospective at the TFAM and a growing international engagement with artists associated with Signals Gallery has sparked renewed interest in Li’s work, with a clutch of recent commercial exhibitions in London and Taipei. 5 But despite this more recent attention, art history—in Britain as in Taiwan—is yet to seriously engage with the remarkable art space he founded in the Cumbrian countryside, the LYC Museum & Art Gallery (the LYC), in 1972 as arguably his most important work.6

5The reasons for why this is so are not clear-cut. One can speculate that the voluminous Li Yuan-chia archives at the John Rylands Library at the University of Manchester have yet to be catalogued, so research is time and resource intensive; or that its non-conformity with conventional models of institutional critique and practice present a hurdle requiring some effort and imagination; or more prosaically, that a focus on the LYC does little to advance the commercial attractiveness of Li’s work. Even the exhibition at TFAM—which was broad in scope and ambitious in scale—was conventionally monographic in form and thus not geared towards dealing with the multifarious nature of the LYC, which also does not fit within a national (“father of conceptual and abstract art in Taiwan”) frame.

The LYC was located in the village of Banks, astride Hadrian’s Wall. Li Yuan-chia’s initials gave the museum its name—an act of self-naming that, in the context of the reading proposed by this article, can be interpreted as an artistic claim. Between 1972 and 1983, the museum showcased the work of more than 320 artists—from local artists (Andy Christian, Susie Honour) to totemic national figures (Paul Nash, Barbara Hepworth), and contemporary artists, now of international renown (Lygia Clark, Andy Goldsworthy), but then barely known in Britain. A young David Nash designed the LYC’s window (fig. 6). The networks and practices that the LYC enabled and enriched have yet to be studied widely. For example, his friendship with the concrete poet and Benedictine monk, dom sylvester houédard, or the pioneering sound artist, Delia Derbyshire—Li’s assistant, and briefly partner, at the LYC (1976–1977) have only recently begun to be addressed in exhibitions and publications.7

7

Friendships, and the expanded notions of infrastructure they often become part of, are growing areas of recent scholarship that can productively illuminate any consideration of the LYC. In Affective Communities, Leela Gandhi charts a history of anti-colonialism through a series of “minor narratives of crosscultural collaboration between oppressors and oppressed” retrieved from colonial archives.8 She engages the intellectual legacies of an impressive range of earlier scholars (Kant, Hegel, Marx, Foucault, Said, and Nandy) to build on Derrida’s recognition that there exists in “the unscripted relation of ‘friendship’ an improvisational politics appropriate to communicative, sociable utopianism investing it with a vision of radical democracy.”9 Her proposition is for a liberatory politics in the heart of “empire” that she labels the “politics of friendship”. In her recent essay, Infrastructure as Form, Karin Zitzewitz considers the case of the workshops initiated by the Triangle Arts Trust and argues for the need “not to separate analysis of the works of art from the activities from which they emerge.”10 To do so, she contends, would attribute “artistic production exclusively to the artist [… and] ignore how ably a networked art infrastructure distributes agency among its elements.”11

8The LYC is an exemplary site from which to explore both these formulations: the question of how friendships inform shared practices, generate work, and socialise narratives; and of how the LYC itself functions as a kind of infrastructure. The LYC is also a singular site from which to consider historic entanglements with the potential to enrich and expand existing histories of British art.12 Undertaking such inquiries that cross disciplinary and geographic borders requires polyphonic, multi-authored, and speculative approaches that I have described elsewhere as “art histories of excess”.13 The work of Li Yuan-chia is beginning to attract such collective effort.14 This essay is anchored in two recent initiatives that bring the focus specifically to the LYC Museum & Art Gallery itself.

12The first is the exhibition that I curated with Kate Jesson at Manchester Art Gallery—Speech Acts: Reflection-Imagination-Repetition (2018–2019).15 At the heart of the exhibition, which contained work by more than forty artists, was a stylised reconstruction of the LYC (fig. 7). Speech Acts posited the LYC as both an artwork and as a hub for nurturing art and community, and explored the role of museums in forging and circulating collective stories through the artworks they collect and the exhibitions they arrange (fig. 8). It considered the case of the LYC as one example of how networks of people shape artistic practices and determine how artworks circulate. It suggested that affinities—between people and practices—help create the shared stories that forge meaning in art.

15

The second example is a symposium anchored in the Speech Acts exhibition—The LYC Museum & Art Gallery and the Museum as Practice (March 2019).16 It brought together scholars, artists, museum directors, and curators to consider ideas of place, friendship, exhibitions, publications, and the function of museums. This article forms part of this larger collective research project. It explores the idea of “friendship”, and to a lesser extent that of “infrastructure”, through the lens of three works in the Speech Acts exhibition. All three works are participatory, and have to different extents, collective authorship and a relationship with Li. Through them, I attempt to read the traces of “friendship” in objects and situations.

16The principal artwork is the LYC itself—not in the conventionally understood sense of a building devoted to the acquisition, care, study, and display of culturally significant objects—but as a relational and participatory work of art. The focus in this article is on the formation of the LYC, how its ethos was informed by Li’s early experimentation with participatory art, and the friendships he formed during his stay at Boothby. The second, the video work Point in Time (1987) by Madelon Hooykaas and Elsa Stansfield, features Li as a participant, and encapsulates an exchange of ideas, aesthetics, and affective registers nurtured through years of discussions.

The third and final example is the newly commissioned film, Space & Freedom (2018), by artist–film-maker, Helen Petts. It mixes archival footage shot by Li and lost sound recordings, with new film footage shot by Petts and accompanied by improvised sound by Steve Beresford, to become a site for collaboration across time.

The LYC and the Museum as Practice

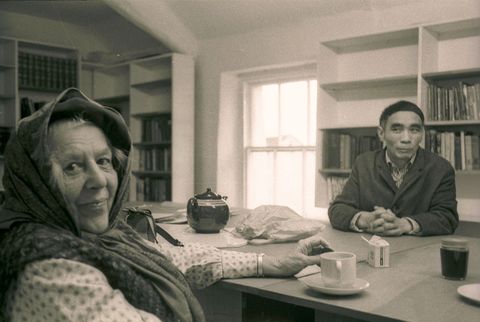

The LYC has often been positioned as Li sacrificing his own practice, while he gave “his attention to others”.17 But I would like to place the LYC in an artistic trajectory that saw Li moving away from static objects and towards the production of work that invited participation from audiences to animate the work. The museum started life as a set of dilapidated farm buildings that Li bought from his friend and neighbour, the painter Winifred Nicholson (fig. 9). Li showcased her work in four separate exhibitions at the LYC. Around this nucleus, he built an exhibition programme of prodigious range and eclecticism. The programme was indebted to Li’s cosmopolitanism and his commitment to art as a mode of experimentation. Apart from being a painter, sculptor, and photographer, Li was also a poet, designer-maker, and curator—of art and social interaction. For him, art was social interaction. And it was this expansive vision that Li brought to not just the programme but also to the construction and functioning of the LYC.

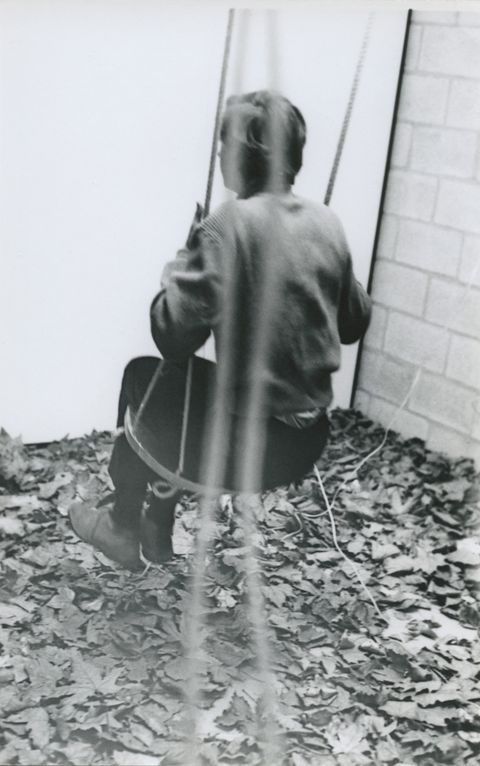

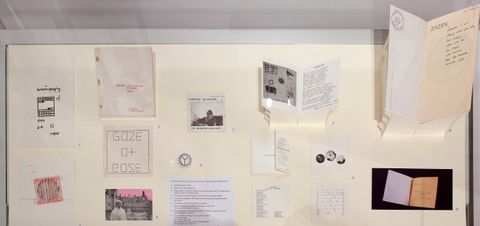

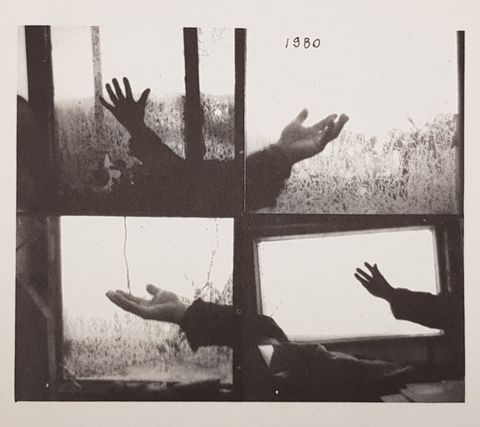

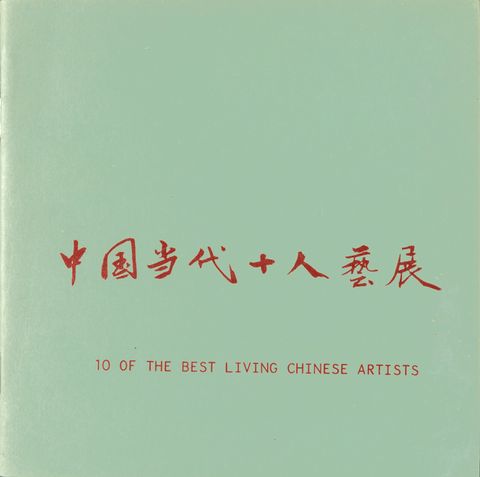

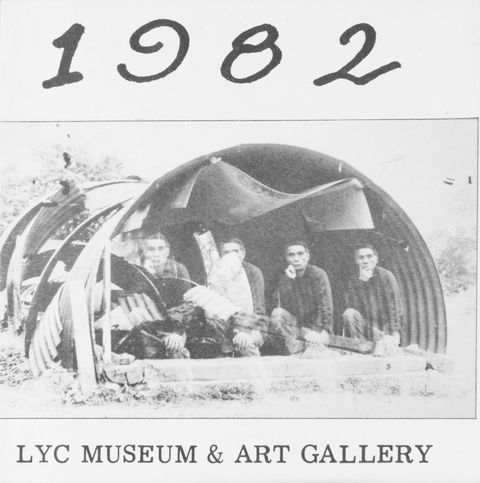

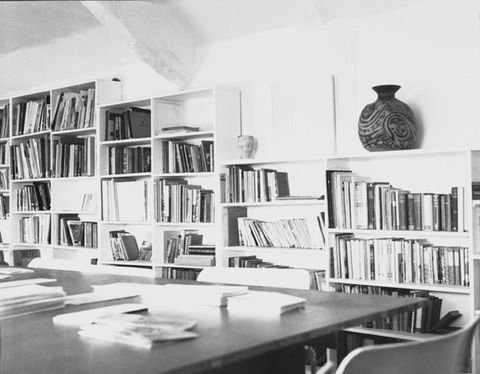

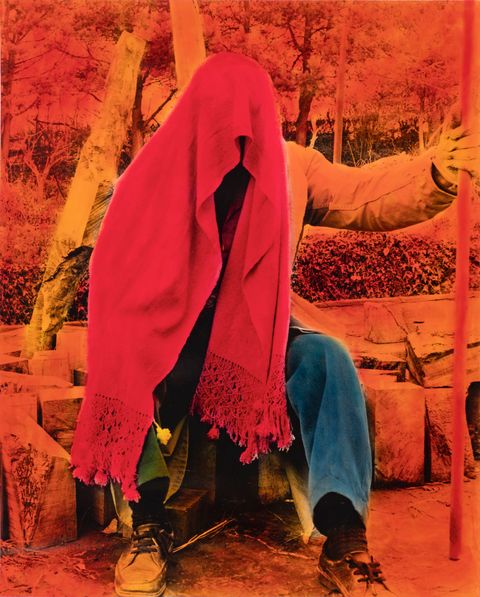

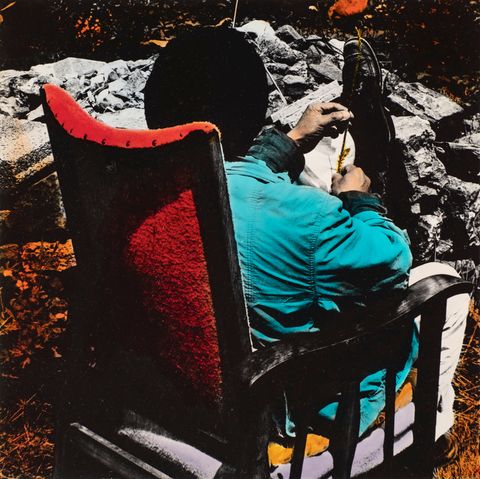

17The LYC consumed Li. He built it himself—undertaking all construction, plumbing, and electrical work (fig. 10). At its peak, it hosted four new exhibitions a month, each accompanied by a catalogue that he designed and printed (Figs. 11, 12, 13, 14, 15). Apart from galleries, the LYC had a children’s room, library, performance space, printing press, communal kitchen, and garden (fig. 16). It hosted rug-making workshops. Children played in its courtyard (fig. 17). It was an open space for the multiple possibilities of art. The artist Shelagh Wakely, who exhibited at the LYC in 1979, saw the museum as “a work of his [Li’s]”.19 Mei-ching Fang, who curated Li’s retrospective at TFAM, considered his establishing and running a museum as “an idealistic practice”.20 It was an example of social practice before such a thing was named and tamed.21 And after its closure to the public in 1983, it became the site of Li’s experimentation with photography (Figs 18, 19, and 20).

19

Li’s establishment of the LYC in 1972 was considered an “impulsive, intuitive move”.22 But I read the LYC’s formulation as more of a progression of the experimentation that Li was engaged in during his time at Boothby (1967–1971). His friend Nick Sawyer invited Li to Boothby. Sawyer first met Li at the Signals Gallery, and went on to help produce Li’s multiples for his subsequent exhibition at the Lisson Gallery.23 Boothby was the family house of Sawyer’s stepfather, Wilfrid Roberts. Roberts was a farmer turned radical Liberal politician, who Sawyer recounts as “playing chess with Wyndham Lewis, getting drunk with Dylan Thomas, and dining out with Stalin.”24 Wilfred Roberts’ elder sister was Winifred Nicholson. Wilfrid and Winifred were the grandchildren of George Howard, the 9th Earl of Carlisle, a “painter of pre-Raphaelite tendencies and a younger member of the circle of William Morris and Burne-Jones”.25

22

Boothby was thus a repository of unusual artistic treasures. A Bomberg hung in Sawyer’s bedroom (Tudor Room). Sawyer recounts thumbing through a hand-painted William Blake manuscript as a child, and being surrounded by art works by Moore, Rosetti, and of course Winifred Nicholson.26 Early during the Second World War, Nicholson moved from Paris to Boothby and made it her Cumbrian base for the next twenty years, where she painted views from the house as well as its interiors (fig. 21). Competing with the bountiful beauty of nature in the vicinity of Boothby was an eight-foot metal sculpture of Buddha—brought to Cumbria by her father Charles Roberts, who had served as Under-Secretary of State for India.

26

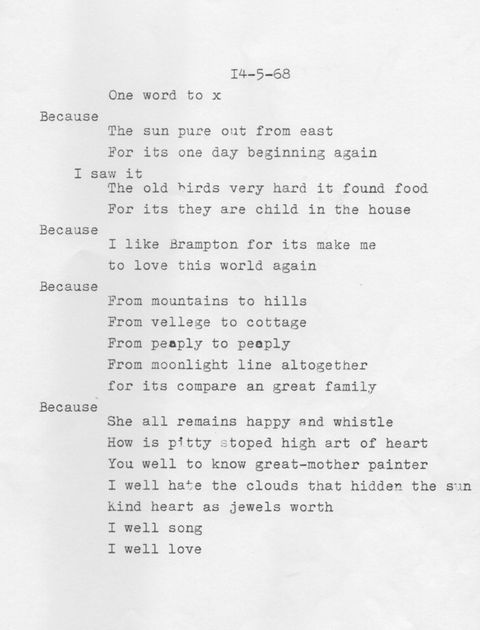

On arriving at Boothby for Christmas in 1967, Li struck a friendship with Wilfrid and Kate Roberts, and was offered a large studio room at Boothby at nominal rent—a room that offered Li the same vista as Winifred Nicholson’s studio. Those views also inspired Li and found voice in his poetry (fig. 22).

Li had come to Cumbria in search of “space” and “freedom”, and managed to establish a livelihood through gardening, painting, and decorating.27 This allowed him to experiment in his studio at Boothby without the need to sell to survive. And the two self-organised exhibitions he held in Boothby evidence a growing interest in exhibiting environmental and participatory works. The first was held between in October 1968;28 the second was in June 1969.29 Both these exhibitions are likely to have informed Lisson Gallery’s better-known exhibition, Li Yuan-chia: Golden Moon Show (16 October–29 November 1969) (fig. 23).

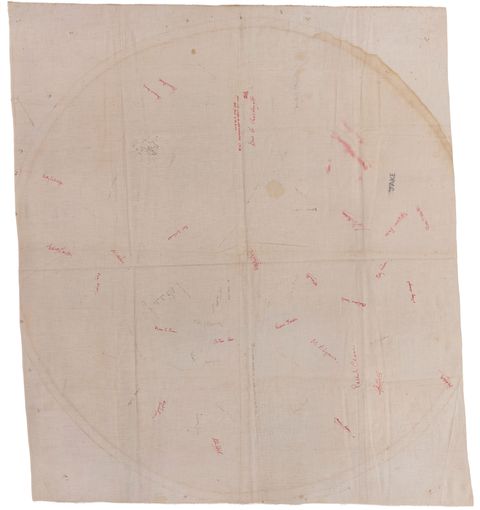

27The digital archive of artist and art promoter Richard Demarco, offers a set of installation photographs of the first Boothby exhibition (Figs 24, 25, 26, 27, and 28).30 The photos show elaborate arrangements of Li’s circular discs, many with his movable magnetic points. Plastic sheets hung from the ceiling with circular holes cut in them, delineate micro-environments within the large space. Also visible are two large patterned wall hangings, and most curiously, an arrangement of Li’s geometric points on a tufted circular rug. Several photographs show Li encouraging his visitors to interact directly with the work. One photograph shows a web-like installation with washing lines strung across the trees in the courtyard of Boothby. An important trace of the exhibitions at Boothby is a tablecloth that served as Li’s visitor’s book (fig. 29). The trajectories that any one of these names—Audrey Barker, Eejay Hooper, or Winifred Nicholson—open up, are vast; and beyond the scope of this paper.

30

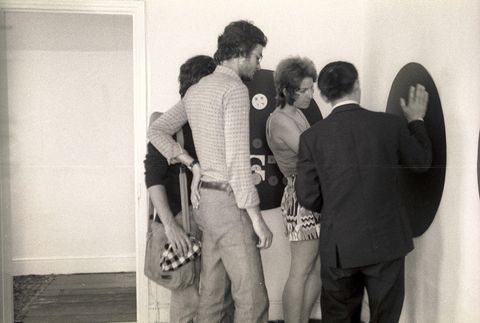

By the time of Li’s participation in the little known but important exhibition Popa at Moma: Pioneers of Part-Art, at Museum of Modern Art, Oxford in 1971, Li had already been exhibiting environmental and participatory works in his studio in Boothby, and subsequently at Lisson Gallery. Popa at Moma was curated by Mark Jones and Rupert Legge and is considered the first institutional attempt in the UK to frame participatory practices (or “Part-Art”) as an artistic tendency. It featured Lygia Clark, John Dugger, David Medalla, Hélio Oiticica, Graham Stevens, and Li Yuan-chia. And it achieved notoriety for when a jolly young Oxford crowd took the Part-Art manifesto literally and as Hilary Floe quotes “Everything was Getting Smashed” (fig. 30).31 Two of the artists who were there for the opening—Medalla and Dugger—withdrew their work. Li was happy to let his work be. The show opened and closed on the same evening.

31

Li’s openness to sharing agency, by not intervening to limit the terms on which the Oxford audience participated, was to be later channelled into the functioning of the children’s art room at the LYC—where both Li’s art works and art materials were available for children to “play” with. The LYC was Li showing us how Participatory Art could live in a museum setting; where the operational activity of running a museum—the openings, performances, the programming, and publishing activities—could themselves be considered as part of an art work. It suggests that Li’s engagement with place, and a close circle of friends with distinct artistic visions, played an important role in shaping Li’s imagination of what the LYC could be.

This is not to diminish Li’s agency in its making. Instead, I suggest a reading of his practice that, during the time of his stay in Boothby, was moving away from reliefs, paintings, and static objects to kinetic sculptures, “toys”, multiples, “environments”; situations that invited an activation of objects, materials, space, and human relations. This direction in his work was in conversation with the work of a number of artists associated with Signals Gallery. He had simply taken it further. In the LYC, Li had fashioned a machine capable of changing people’s relationship with art, with each other, and hence with life.

The catalogue accompanying Li’s last monographic exhibition in the UK has a section on the LYC Museum & Art Gallery.32 It carries reprints of reviews in the press (Paul Overy, The Times, 4 September 1974; and Kenneth Hudson, The Illustrated London News, October 1980) and personal reflections from a number of artists and friends who had played a part in the life of the LYC. With the addition of interviews with visitors to the LYC, it helps build a multi-vocal account of how the museum operated and its many distinctive features—from the tea that greeted visitors to its library of donated art books. Artists in particular were struck by what David Nash identified as Li’s combination of “humble modesty with outrageous ambition”.33 Many picked out the unique experience of staying at the LYC while working with Li on the installation of the exhibition.

3234To show at LYC Museum was something special … The windows were at floor level making the often misty landscape part of the installation … It was very much his place: it was a work of his, imbued with his aesthetic … I left with my belief in art revitalised.

—Shelagh Wakely34He also made a garden and created a small world that was a place of its own. He never tried to fit in, it was we who were expected to fit into Li’s imaginative world. He was firmly determined to impose his vision, to make that world accessible to whoever would come within range of his remarkable presence.

—Kathleen Raine35Li made me question the purpose of art.

—Katerina El Haj36He created a space that had something for everybody, adult and child.

—David Nash37

Point in Time and the Primacy of Encounter

There is a copy of Zazen—the artist Madelon Hooykaas’ photo book documenting her 1970 stay in a Japanese monastery—in the LYC Archive (fig. 8).38 It carries a dedication to her friend, occasional collaborator, and Li’s erstwhile partner, Delia Derbyshire. It is dated 1976—the year before Madelon Hooykaas and her long-term collaborator, Elsa Stansfield, exhibited at the LYC. On either side of the dedication are rubber stamps that suggest a sequential ownership. One simply reads “Delia Derbyshire”. It is mirrored on the inside cover by a competing claim: “LYC Museum Library”. This larger stamp also grounds this object in a place—Banks, Brampton, Cumbria. It reveals the web of friendships that underpin another collaborative work in the Speech Acts exhibition, Point in Time (1987) by Stansfield/Hooykaas (fig. 31).

38Elsa Stansfield and Madelon Hooykaas are pioneering figures in the history of video art in Europe. Friends from their time together at the Ealing School of Art & Design in 1966, they started collaborating on films and what they called “video-environments” in the early 1970s. Hooykaas worked with Stansfield at her film and sound studio (8, 9, and 10 in Neal’s Yard, London) and were joined by Delia Derbyshire. They worked on two projects with Derbyshire. When Derbyshire moved to Cumbria, they visited their friend at the LYC and were introduced to Li. They showed at LYC in 1977 and became firm friends of Li’s—bonding over a common interest in Zen Buddhism and long walks. Their friendship continued despite Elsa’s move to Holland as Head of the Department for video/sound (Time Based Art) at the Jan van Eyck Academie, Maastricht. Point in Time dates from when Li visited them in Holland after the closure of the LYC.39

39Point in Time suggests a journey—both physical and internal. The physical one is dominated by footage of a rocky terrain that seems to have been shot from a car and then slowed down. It is frequently abstracted. The film is punctuated by lingering images of fluttering flags—none of which seem to bear overt symbols of national affiliation. A modulated drone evokes and echoes highland winds. We are traversing time and place. Interspersed with footage of the physical journey(s) are views of Li’s hand preparing for and performing calligraphy. The preparation of the black ink conveys a luxuriant treatment of time. An ink stick is pressed against a stone mortar and then ground down through describing steady rhythmic circular movements. Minute amounts of water are mixed into the ink to modulate the thickness. Too thick and the writing will not be fluent. Too thin and the ink will flow too fast. This is a practiced ritual.

We follow Li’s hand dip a brush into the ink and describe Chinese characters on paper. The camera shifts to extreme close up. We see the pulse of the brush in the hand. The movement is not the dramatic flourish of a heroic Jackson Pollock drip painting, but more the careful listening of the divining stick or dowsing rod being manipulated over land to locate a source of water. And as the brush touches the paper, we witness the small oceans of ink from which the calligrapher structures meaning. This is an internal journey. A search. This reading is lent support by the appearance of an enigmatic compass that frames the beginning and the end of the work; the movement of the needle—from true north to wild gyrations—suggesting circuitous routes.

Point in Time evidences an engagement with place, spirituality, and calligraphy—through practice. It encapsulates an exchange of ideas, aesthetics, and affective registers nurtured through years of discussions amongst friends in the multiple languages and practices of calligraphy, sound, and video. It also hints at a shared interest in Buddhism that inflects both practices: those of Li and Stansfield/Hooykaas. As Dorothea Franck points out, “Buddhists are not primarily believers but practitioners”. 40 A section of Franck’s text on Stansfield/Hooykaas bears the title, “Saying what cannot be said”, and is an uncanny echo of the title of the survey exhibition of Li’s work, Li Yuan-chia: Tell Me What Is Not Yet Said (2000), curated by Guy Brett. Both titles emphasise the unknown, the unsaid, and the unsayable, suggesting the primacy of encounter and feeling as a way to experience the practice of Li and Stansfield/Hooykaas.

40This interpretation of Point in Time also sheds light on how the LYC operated, where the primacy of encounter—between exhibiting artists and the landscape; visitors and art; and of all of the above with Li—was privileged. Where Li’s endless pots of tea and “strange mixture of peanut butter and mixed fruit” welcomed all with casual warmth, every day of the year until 7pm.41 Where the rug-making classes, the library, poetry readings, and children’s art room made every trip to the LYC also an encounter between art and life—a pit stop in life’s ongoing journey.

41The Search for Space & Freedom

If Hooykaas/Stansfield were friends Li knew, Helen Petts was a friend he did not. Helen Petts’ film, Space & Freedom (2018), was newly commissioned for Speech Acts and takes its name from Li’s search for the same in Cumbria (fig. 32). It begins in darkness. There are no titles, no images, and the black screen heightens our sense of hearing. Despite this preparation, we still have to strain to hear a heavily accented male voice whistling; seemingly communicating in birdsong. Later in the film, we hear him describing his vision for a place. The voice is Li Yuan-chia’s and the place—the LYC in Bankside.

Because of its privacy settings, this video cannot be played here.

These recordings of Li’s voice were hiding in plain sight on reel-to-reel tapes in the still to be catalogued LYC archives at the Special Collections of the John Rylands Library. This is the first time this recording has been digitised and possibly the first time it has been heard since Li recorded it. It literally gives voice to Li’s ideas for the LYC—a vision he obviously felt compelled to record for posterity. In the full cut of Space & Freedom, Li says:

42Want happen a small theatre … for perform music, and … upstairs … I would like have my office and a store room. But when I completely finish … I feel upstairs could very beautifully, could be, make a lovely art gallery. So I change my mind. No longer will happen the office and a store room, open for a gallery.

Ground floor … could be used for the theatres, but we only use for one more play … then no longer have second time. Well, give my new ideas, I will change from the small theatre, change it to the arts room. Arts room will be … provide colours, pens, papers, let everybody, anyone wish coming in and enjoy yourself … draw a pictures … or writing a poetry … writing a story … sometimes picture with the story together. So … so it will be give creative joy, to the children. So children, they have something to do. They are not running away all the buildings. (Inaudible) very peaceful, there, they enjoying it. So the parents can, walking around the gallery, enjoy works of art, or crafts … or enjoy the library books.42

The recording also provided Petts with a sonic clue to Li’s interest in contemporary avant-garde classical music.43 It was recorded over an episode of the BBC programme, Music of Our Time, which has not been completely erased by the over-recording—functioning, as Petts points out, “like pentimenti in painting”.44 Petts makes a feature of the scratchy nature of this sound, inviting the musician Steve Beresford to “punctuate” her film with improvisations from prepared pieces for piano.

43Petts uses Li’s archival sound recording as one of the central pillars of Space & Freedom. She combines it with previously digitised video shot by Li on a 8mm camera; film she shot on location; and original music improvised by Steve Beresford. The film thus becomes a site for collaboration across time—with Li and Beresford. A collective exploration of the rhythms, textures, sights, and sounds of the Cumbrian landscape that inspired Li. By toggling back and forth between archival and contemporary footage, with the archival film shown in black and white, Petts allows us to enter the space and place of the LYC at two different times more than four decades apart.

Space & Freedom’s complex yet light soundscape anchors the LYC in nature. Birds chirp, tweet and sing; water burbles and gushes; the wind is an understated presence at the edge of perception; its soughing accompanies us on rambles through the trees. Slow panning shots frame the quiet majesty of the LYC’s physical location, underlining the central importance of its natural setting in the experience for exhibiting artists, visitors, and indeed Li himself.

David Nash called the LYC “an oasis of how life and art could be”, and likened it to “a growing plant” in being “vulnerable yet determined”.45 Space & Freedom allows us a glimpse into this plant-like oasis, whose capacity to spark creative thought persisted for Li, even after the LYC’s closure; when its garden became the stage for his experimentation with photography and, as shown in one segment of the archival clip above, animation. Li mined the performative possibilities offered by temporary arrangements of everyday objects (blocks of wood, a ball, an umbrella, and hedge shears) and his own body to produce a lyrical body of work tinged with a melancholic beauty (fig. 33).

45

Petts’ film may be structured as a collage but it slowly reveals the LYC and its setting with a painter’s sensibility. It can be seen as a companion piece to Throw Them Up & let Them Sing, her poetic film on Kurt Schwitters’ exile in Norway and then the Cumbrian countryside. Petts seems to share the historian Macaulay’s liking for working on the dead. “With the dead there is no rivalry,” he wrote. “In the dead there is no change. Plato is never sullen. Cervantes is never petulant. Demosthenes never comes unreasonably. Dante never stays too long.”46 Petts’ film clearly shows us that the dead do speak to us; but for that we have to be willing to listen.

46The Necessity of Collaboration

There is in the discipline of art history an impulse to disentangle entangled histories—to reduce the complex and the messy to tidy pockets of monographic depth. Contained. Neat. Sharp-edged. This brief look at a handful of examples—the formation of a museum and two films—underlines the need for forms of art-historical research that allow sense to emerge from polyphony; forms that embody “undisciplined” approaches, not reducible to neat monographic accounts.47 It points to the need for “art histories of excess” that exceed nations, institutions, and singular art historians examining single objects or single subjects.48

47There is in this call a recognition of the need for collaboration—for both conducting research and in its staging. The exhibition is one form capacious enough to do both, while maintaining the possibility for speculation—for resisting closure. Digital publishing—that allows open access not just to art-historical propositions, but also to methodologies and, where possible, to digital copies of underlying archival material—is another.

This issue of British Art Studies also carries an article by David Butler on Delia Derbyshire; and BAS editor Baillie Card’s interview with the actor, writer, and director, Caroline Catz. Catz’s recent short film, Delia Derbyshire: The Myths and the Legendary Tapes (2018), also touches on the time Derbyshire spent at the LYC. In dialogue with this article, the Speech Acts exhibition and the symposium on the LYC Museum & Art Gallery, these initiatives continue the journey towards a multi-authored, expansive, and entangled history of artistic practice that may help us understand the role of friendships in Li Yuan-chia’s Cumbrian cosmopolitanism.

Acknowledgements

This article would not have been possible without the generous support of Sonia Boyce, David Dibosa, Mei-ching Fang, Stella Halkyard, Madelon Hooykaas, Susan Pui San Lok, Janette Martin, Helen Petts, Nick Sawyer, Sarah Victoria Turner, Kaiwei Wang, and Wei Yu.

About the author

-

Hammad Nasar is a curator, writer, and researcher based in London. He is co-curator (with Irene Aristizábal) of British Art Show 9 (2020–2022), and a Senior Research Fellow at the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, where he co-leads (with Sarah Turner) the London, Asia project. Earlier, he was the inaugural Executive Director of the Stuart Hall Foundation (2018-19); Head of Research & Programmes at Asia Art Archive, Hong Kong (2012–2016); and, co-founded (with Anita Dawood) Green Cardamom, London (2004–2012).

Footnotes

-

1

Wall text for the exhibition, Viewpoint: A Retrospective of Li Yuan-chia (2014), at the Taipei Fine Art Museum (TFAM). Viewpoint was a collaboration between TFAM and the LYC Foundation; with LYC Foundation Trustees Guy Brett and Nick Sawyer co-curating the exhibition with Mei-ching Fang, TFAM’s Chief Curator. ↩︎

-

2

Li’s work was included in The Other Story: Afro-Asian Artists in Post-War Britain (1989), curated by Rasheed Araeen at the Hayward Gallery, with subsequent touring venues including Wolverhampton Art Gallery, Manchester City Art Gallery and Cornerhouse, Manchester. A posthumous retrospective exhibition, Li Yuan-Chia: Tell Me What Is Not Yet Said (2001), curated by Guy Brett, was organised by Iniva (Institute of International Visual Arts) at the Camden Arts Centre, London; Abbot Hall Art Gallery and Museum, Kendal; and Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussels. ↩︎

-

3

Leyla Fakhr, “Artists in Pursuit of an International Language”, in Migrations: Journeys into British Art, ed. Lizzie Carrey-Thomas (London: Tate Publishing, 2012), 55. ↩︎

-

4

Quoted in Rasheed Araeen, “Taking the Bull by the Horns”, in R. Araeen (ed.), The Other Story; Afro-Asian Artists in Post-War Britain (London: Southbank Centre, 1989), 57. Araeen’s quotation is from Li’s letter/statement to Andrew Dempsey (Assistant Director, Hayward Gallery), 3 July 1989. ↩︎

-

5

Recent exhibitions on the Signals Gallery have been held by a number of London-based commercial galleries including: England & Co (2014), S|2 (2018), and Thomas Dane (2018). Solo exhibitions of works by a number of artists associated with Signals Gallery including dom sylvester houédard and Li Yuan-chia have also been held in the last few years by galleries including: Richard Saltoun (2016, 2017), Lisson Gallery (2018), and S|2 (2017), and Each Modern (2019), in London, New York, and Taipei. It is worth noting that this interest has, in the case of Li and others, been instigated through an international process of reclamation by institutions based in Asia. For an exploration of this topic, see Hammad Nasar: “Notes from the Field: Navigation the Afterlife of the Other Story”, Asia Art Archive, 1 April 2015*. https://aaa.org.hk/en/ideas/ideas/notes-from-the-field-navigating-the-afterlife-of-the-other-story. ↩︎

-

6

While the catalogues accompanying both significant monographic exhibitions—Viewpoint: A Retrospective of Li Yuan-Chia (2014) and Li Yuan-Chia: Tell Me What Is Not Yet Said (2001)—devoted considerable attention to the LYC as being more than simply another exhibiting institution, they did not advance a particular position in how it fit within Li’s wider artistic practice. ↩︎

-

7

The exhibition Performing No Thingness (2016) curated by Nicola Simpson at Norwich University of the Arts, explored the concept of “nothingess” in the work of artists Li Yuan-chia, dom sylvester houédard, and Ken Cox through staging an interplay of art works and correspondence. See also Andy Christian’s In the North Wind’s Breath (The Private Press at Penny Royal, 2018), 22–23, for a potted account of Delia Derbyshire and Li’s life at the LYC. The slim booklet shares personal perspectives from Christian; who was an exhibiting artist at the LYC and lived nearby. ↩︎

-

8

Leela Gandhi, Affective Communities: Anticolonial Thought, Fin-de-siècle Radicalism, and the Politics of Friendship (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2006), 6. ↩︎

-

9

Gandhi, Affective Communities, 19. ↩︎

-

10

Karin Zitzewtiz, “Infrastructure as Form: Cross-Border Networks and the Materialities of ‘South Asia’ in Contemporary Art”, Third Text 31, nos 2–3 (2017): 341–358. ↩︎

-

11

Zitzewtiz, “Infrastructure as Form”, 357. ↩︎

-

12

Investigating the history of the LYC has been a key part of the ongoing research project, London, Asia, at the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art. For more on the London, Asia project, see https://www.paul-mellon-centre.ac.uk/projects/london-asia. ↩︎

-

13

Hammad Nasar and Karin Zitzewitz, “Art Histories of Excess: Hammad Nasar in Conversation with Karin Zitzewitz”, Art Journal (Winter 2018): 106–112. ↩︎

-

14

Viewpoint: A Retrospective of Li Yuan-chia (2014) at the Taipei Fine Art Museum (TFAM) was a collaboration between TFAM and the LYC Foundation (see Note 1). The Black Artists and Modernism (BAM) research project—funded by the AHRC and led by University of the Arts London (UAL) in collaboration with Middlesex University—organised a study day on Li’s work with Iniva on 13 February 2017—which included presentations and discussions on different aspects of Li’s work; see https://www.iniva.org/programme/events/li-yuan-chia-study-day-2. For more on BAM, see http://www.blackartistsmodernism.co.uk/about/. ↩︎

-

15

Speech Acts: Reflection-Imagination-Repetition (2018–2019), curated by Hammad Nasar with Kate Jesson, was presented by Manchester Art Gallery in partnership with the BAM project (see Note 11). A gallery guide to the Speech Acts exhibition is available to view and download from Manchester Art Gallery’s website, http://manchesterartgallery.org/exhibitions-and-events/exhibition/speech-acts/. Selected texts from the guide accompanied by installation images of the exhibition were published by ArtUK, and are available at: https://artuk.org/discover/stories/speech-acts-introduction-by-the-director-of-manchester-art-gallery-and-the-whitworth; https://artuk.org/discover/stories/speech-acts-an-introduction-by-sonia-boyce; https://artuk.org/discover/stories/speech-acts-a-curatorial-introduction; https://artuk.org/discover/stories/speech-acts-reflections-performing-the-self; and https://artuk.org/discover/stories/speech-acts-imagination-the-sum-of-all. ↩︎

-

16

The LYC Museum & Art Gallery and the Museum as Practice, 6–7 March 2019, Manchester Art Gallery. This symposium was organised by the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art (PMC) and University of the Arts London (UAL), in collaboration with Manchester Art Gallery and the University of Manchester; it was convened by Hammad Nasar, Lucy Steeds, and Sarah Victoria Turner. For more details, see https://www.paul-mellon-centre.ac.uk/whats-on/forthcoming/the-lyc-museum-art-gallery-and-the-museum-as-practice. ↩︎

-

17

“Chronology”, in Li Yuan-Chia: Tell Me What Is Not Yet Said (London: Institute of International Visual Arts, 2000), 148. ↩︎

-

18

Quoted in Mei-ching Fang, “More than a Museum: LYC Museum and Art Gallery”, in Viewpoint: A Retrospective of Li Yuan-chia, Vol. I (Taipei: Taipei Fine Art Museum, 2012), 127. ↩︎

-

19

Shelagh Wakely in Li Yuan-chia: Tell Me What Is Not Yet Said, 135. ↩︎

-

20

Mei-ching Fang, “More than a Museum”, 117. ↩︎

-

21

Socially engaged practice has been professionalised as a field of study and artistic practice in the twenty-first century, with numerous courses being taught in art schools and universities across the world, and its impact being studied and measured by museums and funding bodies, see https://www.museumsassociation.org/download?id=1249262. ↩︎

-

22

Hammad Nasar, Interview with Nick Sawyer, 21 June 2018. ↩︎

-

23

Sawyer later studied at the Courtauld Institute of Art and became part of “Exploding Galaxy”—an experimental dance drama group (founded by David Medalla) that lived as a community in Balls Pond Road, North London between 1967 and 1968. ↩︎

-

24

Hammad Nasar, Interview with Nick Sawyer, 14 June 2018. ↩︎

-

25

Obituary of Rosalind Lady Carlisle in The Times, 13 August 1921. http://ghgraham.org/text/rosalindhoward1845_obit.html. Accessed 24 June 2018. ↩︎

-

26

Nasar, Interviews with Nick Sawyer, 14 and 21 June 2018. ↩︎

-

27

Quoted in Diana Yeh, “Utopia Beyond Cosmopolitanism: A Translocal View of Li Yuan-chia”, in Viewpoint: A Retrospective of Li Yuan-chia (Taipei: Taipei Fine Art Museum, 2012), 21. ↩︎

-

28

Li Yuan-chia, Boothby Studio Exhibition catalogue (Cumbria, 1968); see also “Chronology”, in Li Yuan-chia: Tell Me What Is Not Yet Said, 147. ↩︎

-

29

Invitation to a reception at Li’s Boothby Studio on 28 June 1969 reproduced in “Chronology”, in Li Yuan-chia: Tell Me What Is Not Yet Said, 147. ↩︎

-

30

For photographs of Li Yuan-chia in Cumbria on numerous occasions from 1969 to 1978, see the Richard Demarco archive, http://www.demarco-archive.ac.uk/people/149-li_yuan_chia. The group of photographs showing Li’s own exhibition in 1969, however, have been mislabelled and are not in his studio at the LYC, but at Boothby. The LYC was not established in 1969. I am grateful to Nick Sawyer for confirming this. ↩︎

-

31

Hilary Floe, ‘‘Everything was Getting Smashed’: Three Case Studies of Play and Participation’, Tate Papers no. 22 (Autumn 2014). https://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/22/everything-was-getting-smashed-three-case-studies-of-play-and-participation-1965-71. Accessed on 8 February 2019. ↩︎

-

32

Li Yuan-chia: Tell Me What Is Not Yet Said (London: Institute of International Visual Arts, 2000), 148. ↩︎

-

33

David Nash in Li Yuan-chia: Tell Me What Is Not Yet Said, 139. ↩︎

-

34

Shelagh Wakely in Li Yuan-chia: Tell Me What Is Not Yet Said, 135. ↩︎

-

35

Kathleen Raine in Li Yuan-chia: Tell Me What Is Not Yet Said, 134. ↩︎

-

36

Interview with the musician, artist and creative practitioner Katerina El Haj, 7 February 2018. El Haj is a member of the Nicholson family and visited LYC during the summer during her childhood holidays over several years. ↩︎

-

37

David Nash in Li Yuan-chia: Tell Me What Is Not Yet Said, 139. ↩︎

-

38

Else Madelon Hookyaas and Bert Schierbeck, Zazen (Tucson, AZ: Omen Press, 1974). ↩︎

-

39

Interview with Madelon Hooykaas, 2 March 2018. ↩︎

-

40

Dorothea Franck, “Deep Looking: A Buddhist Look at the Work of Stansfield/Hooykaas”, in Madelon Hooykaas and Claire van Putten (eds), Revealing the Invisible: The Art of Stansfield/Hooykaas from Different Perspectives (Amsterdam: De Buitenkampt, 2010), 121. ↩︎

-

41

Artist Lynne Curran in Li Yuan-chia: Tell Me What Is Not Yet Said, 140. ↩︎

-

42

Transcription by Helen Petts. ↩︎

-

43

This is, as Petts acknowledges in email correspondence (21 May 2019), speculative. While Li’s access to a professional ¼ inch reel-to-reel tape recorder in the 1970s suggests more than a casual interest in music, it may have belonged to Delia Derbyshire (see Note 4) and requires further research. ↩︎

-

44

Hammad Nasar, “Helen Petts in Conversation”, Ocula, 23 August 2018, https://ocula.com/magazine/conversations/helen-petts/. Accessed on 20 May 2019. ↩︎

-

45

David Nash in Li Yuan-chia: Tell Me What Is Not Yet Said, 139. ↩︎

-

46

Quoted in Catherine Hall, “Afterword” in Julian Henriques and David Morley with Vana Goblot (eds), Stuart Hall: Conversations, Projects and Legacies (London: Goldsmiths Press, 2017), 305. Hall’s quotation from Macaulay was originally published in the July 1837 (132) issue of the Edinburgh Review, 3, https://archive.org/details/edinburghreview100coxgoog/page/n290, accessed on 17 May 2019. ↩︎

-

47

Irit Rogoff, “Hammad Nasar: Interview with Irit Rogoff”, in Iftikhar Dadi and Hammad Nasar (eds), Lines of Control: Partition as a Productive Space (London: Green Cardamom and Herbert F. Johnson Museum, Cornell University, 2012), 108. ↩︎

-

48

“Art Histories of Excess: Hammad Nasar in Conversation with Karin Zitzewitz”, Art Journal (Winter 2018): 106–112. ↩︎

Bibliography

Araeen, Rasheed (1989) The Other Story: Afro-Asian Artists in Post-War Britain, exhibition catalogue. London: Southbank Centre. Exhibition at the Hayward Gallery, London, 1989.

Black Artists and Modernism (BAM) (n.d.) “About”. http://www.blackartistsmodernism.co.uk/about/.

Black Artists and Modernism (BAM) (2017) Study day on Li’s work with Iniva, University of the Arts London (UAL) in collaboration with Middlesex University, 13 February. https://www.iniva.org/programme/events/li-yuan-chia-study-day-2.

Brett, Guy and Sawyer, Nick (2000) Li Yuan-chia: Tell Me What Is Not Yet Said, exhibition catalogue. London: Institute of International Visual Arts. Exhibition held at the Camden Arts Centre, London, Abbott Hall Gallery and Museum, Kendal, and Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussels, 2001.

Carlisle, Rosalind Lady (1921) “Obituary”. The Times, 13 August. http://ghgraham.org/text/rosalindhoward1845_obit.html. Accessed 24 June 2018.

Catz, Caroline (2018) Delia Derbyshire: The Myths and the Legendary Tapes.

Christian, Andy (2018) In the North Wind’s Breath. The Private Press at Penny Royal.

Fakhr, Leyla (2012) “Artists in Pursuit of an International Language”. In Lizzie Carrey-Thomas (ed.), Migrations: Journeys into British Art. London: Tate Publishing.

Floe, Hilary (2014) “‘Everything was Getting Smashed’: Three Case Studies of Play and Participation”. Tate Papers 22 (Autumn). https://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/22/everything-was-getting-smashed-three-case-studies-of-play-and-participation-1965-71. Accessed 8 February 2019.

Franck, Dorothea (2010) “Deep Looking: A Buddhist Look at the Work of Stansfield/Hooykaas”. In Madelon Hooykaas and Claire van Putten (eds), Revealing the Invisible: The Art of Stansfield/Hooykaas from Different Perspectives. Amsterdam: De Buitenkampt.

Gandhi, Leela (2006) Affective Communities: Anticolonial Thought, Fin-de-siècle Radicalism, and the Politics of Friendship. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Hall, Catherine (2017) “Afterword”. In Julian Henriques, David Morley, and Vana Goblot (eds), Stuart Hall: Conversations, Projects and Legacies. London: Goldsmiths Press.

Jesson, Kate and Nasar, Hammad (2018–2019). Speech Acts: Reflection-Imagination-Repetition. Manchester Art Gallery, 25 May 2018–22 April 2019. http://manchesterartgallery.org/exhibitions-and-events/exhibition/speech-acts/.

Li, Yuan-chia (1968) Boothby Studio Exhibition, exhibition catalogue. Cumbria.

Li, Yuan-chia (1969) Li Yuan-chia: Golden Moon Show, exhibition catalogue. London: Lisson Gallery. Exhibition at the Lisson Gallery, London.

LYC Museum & Art Gallery (n.d.) London, Asia project, Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art. https://www.paul-mellon-centre.ac.uk/projects/london-asia.

Madelon Hookyaas, Else and Schierbeck, Bert (1974) Zazen. Tucson, AZ: Omen Press.

Mei-ching, Fang and Ya-chi Tsai (eds) (2012) Viewpoint: A Retrospective of Li Yuan-chia, exhibition catalogue. Taipei: Taipei Fine Art Museum. Exhibition at the Taipei Fine Art Museum, Taipei, 2014.

Nasar, Hammad (2015) “Notes from the Field: Navigation the Afterlife of The Other Story”. Asia Art Archive, 1 April. https://aaa.org.hk/en/ideas/ideas/notes-from-the-field-navigating-the-afterlife-of-the-other-story.

Nasar, Hammad (2018) Interview with Katerina El Haj, 7 February.

Nasar, Hammad (2018) Interview with Madelon Hooykaas, 2 March 2018.

Nasar, Hammad (2018) Interviews with Nick Sawyer, 14 and 21 June.

Nasar, Hammad (2018) “Helen Petts in Conversation”. Ocula, 23 August. https://ocula.com/magazine/conversations/helen-petts/. Accessed 20 May 2019.

Nasar, Hammad and Zitzewitz, Karin (2018) “Art Histories of Excess: Hammad Nasar in Conversation with Karin Zitzewitz”. Art Journal (Winter): 106–112.

Nasar, Hammad, Lucy Steeds, and Sarah Victoria Turner (2019) The LYC Museum & Art Gallery and the Museum as Practice. Symposium held at Manchester Art Gallery, organised by the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art and University of the Arts London, in collaboration with the Manchester Art Gallery and the University of Manchester, 6-7 March. https://www.iniva.org/programme/events/li-yuan-chia-study-day-2.

Petts, Helen (2018) Space & Freedom, film.

Rogoff, Irit (2012) “Hammad Nasar: Interview with Irit Rogoff”. In Iftikhar Dadi and Hammad Nasar (eds), Lines of Control: Partition as a Productive Space. London: Green Cardamom and Herbert F. Johnson Museum, Cornell University.

Zitzewtiz, Karin (2017) “Infrastructure as Form: Cross-Border Networks and the Materialities of ‘South Asia’ in Contemporary Art”. Third Text 31, nos 2–3: 341–358.

Imprint

| Author | |

|---|---|

| Date | 31 May 2019 |

| Category | Article |

| Review status | Peer Reviewed (Double Blind) |

| License | Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) |

| Downloads | PDF format |

| Article DOI | https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-12/hnasar |

| Cite as | Nasar, Hammad. “Cumbrian Cosmopolitanisms: Li Yuan-Chia and Friends.” In British Art Studies. London and New Haven: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art and Yale University Press, 2019. https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-12/hnasar. |