Whatever Happened to Delia Derbyshire?

Whatever Happened to Delia Derbyshire?: Delia Derbyshire, Visual Art, and the Myth of her Post-BBC Activity

By David Butler

Abstract

The composer and musician Delia Derbyshire (1937–2001) joined the BBC Radiophonic Workshop in 1962 and by the end of the decade had made a major contribution to the British public’s awareness and understanding of electronic music. Much of that awareness was generated by Derbyshire’s celebrated realisation, in 1963, of the original theme tune from Doctor Who. Over the next ten years, Derbyshire’s creative activity as both a BBC employee and a freelance artist would see her providing music and ‘special sound’ for television, radio, film, theatre, and live events such as the first edition of the Brighton Festival in 1967. By 1973, however, Derbyshire had left the BBC, citing the fact that she was “fed up” with how her work was being treated by the Corporation because it was “too sophisticated” and that the BBC was “increasingly being run by committees and accountants”. For many years, the standard account of Derbyshire’s life has been that, following her departure from the BBC in 1973, she withdrew from creative activity until the final few years of her life when she began to collaborate with Peter Kember (Sonic Boom). These accounts have sometimes veered into sensationalist cliché—a 2008 article in The Times characterised Derbyshire as a tragic and self-destructive artist who abandoned music for “a series of unsuitable jobs” and became a “hopeless alcoholic”.1 Recent discoveries and donations to the Delia Derbyshire Archive, however, have pointed to a more complex understanding of Derbyshire’s activity after she left the BBC. Far from withdrawing completely from music, Derbyshire would collaborate on a number of short ‘art’ films in the mid- to late 1970s. This paper draws on this archival material to provide a clearer and more detailed account of Derbyshire’s work in the 1970s, including an unreleased recording from an unfinished project in 1980. Without denying the complications that Derbyshire encountered during this often difficult phase of her life, the article demonstrates that Derbyshire remained creatively engaged and also active as an artist far longer than has often been reported or assumed. In particular, Derbyshire’s creative activity during these years saw her working with visual artists, most prominently Madelon Hooykaas and Elsa Stansfield. In doing so, Derbyshire furthered her long-standing interest in the relationship between electronic music and the visual arts. The article thus provides not only a revisionist account of Derbyshire’s post-BBC activity but also enhances our understanding of the inter-relationship between electronic sound, music, and the visual arts in Britain as well as the nature and extent of Derbyshire’s influence.

2YAMCO with Kaleidophon present a new creative service for British advertising, combining the best of music with the best of electronic sound. … To keep up with your present requirements we must be several years ahead. With our new synthesisers the range of sounds is limitless and here are some of the sounds you’re going to be hearing in the seventies. *—*Brian Hodgson2

As the 1970s began, the composer and musician Delia Derbyshire (1937–2001) appeared to be at the height of her creative activity. Based at the BBC Radiophonic Workshop since 1962, by the end of the decade, Derbyshire’s distinctive electronic and tape-based music and sound design had earned her the respect and admiration of colleagues and collaborators both within the BBC and elsewhere, in theatre, film, and diverse live events and installations, through her burgeoning profile as a freelance artist. She was (and still is) most famous for her remarkable realisation of Ron Grainer’s theme tune for Doctor Who (1963–1989, 1996, 2005–present). That piece alone had generated considerable public interest in the activity of the Radiophonic Workshop with substantial press coverage often emphasising Derbyshire’s role, despite the fact that for much of the 1960s, she and her colleagues did not receive on-screen or printed credit for their work—in keeping with BBC policy at the time. The prominence of Doctor Who and range of her overall output resulted in Derbyshire making a major contribution to the British public’s awareness and understanding of electronic music.3 In 1968, her work featured in two pioneering British concerts of electronic music at the Queen Elizabeth Hall in London and Liverpool University’s Mountford Hall respectively (the latter being the first concert of electronic music given in the north-west of England), but by this point in her career, she was already active in theatre and film, with productions including work for the Royal Shakespeare Company and the London Roundhouse. Having established the short-lived Unit Delta Plus (1966–1967) with the engineer and composer Peter Zinovieff, one of the key figures in the development of synthesiser systems such as the VCS3, and her close friend and fellow member of the Radiophonic Workshop, Brian Hodgson, in the late 1960s, Derbyshire co-founded Kaleidophon, a second independent organisation for the development of electronic music, with Hodgson and David Vorhaus in order to further this increasing freelance activity. Hodgson’s ironic voice-over for Kaleidophon’s demo tape, cited at the start of this article, looked ahead to the 1970s with playful optimism.

3That optimism did not appear to be misplaced at the time. The early 1970s saw Derbyshire involved with innovative and rewarding projects both within and beyond the BBC. In July 1970, she collaborated with Edward Lucie-Smith on “Poets in Prison”, a special event at City Temple Theatre as part of the City of London Festival, featuring “in semi-dramatised form the outcries of the Muse in chains” alongside projections and Derbyshire’s music.4 Less than six months later, in January 1971, she provided music for a BBC Radio 4 schools broadcast of Ted Hughes’ Orpheus, billed in the Radio Times as a new verse play for lights, voices, dancers, and music with Derbyshire’s score evoking the voices of stones and trees. The production won an award at that year’s Japan Prize contest, an international competition for educational broadcasting, with Derbyshire receiving the trophy alongside Hughes and the producer, Dickon Reed, at a celebratory event organised by the BBC.

4Yet, barely two years later, Derbyshire was gone from the BBC and Kaleidophon was no more. The reasons for Derbyshire’s departure in 1973 have been speculated on in various publications and dramatisations of Derbyshire’s life and it is beyond the scope of this article to address them in depth.5 Hodgson’s Kaleidophon demo voice-over anticipated at least three of the most often cited factors: an increased sense of commercialism and less artistically satisfying projects; a heightened workload; and the arrival of new technology in the form of various synthesisers.6

5The working conditions at the BBC Radiophonic Workshop in the early 1970s were also on record as being difficult, in part due to a lack of adequate resources, resulting in the manager of the Radiophonic Workshop, Desmond Briscoe, expressing his concern about the well-being of his staff. To combat this pressure, the Radiophonic Workshop invested in several synthesisers but Derbyshire found them less satisfying than her more time-consuming tape-based and musique concrète approach, which placed the emphasis on generating and crafting her own distinctive sounds. Interviewed by John Cavanagh in 1999, Derbyshire commented how:

That view was reinforced in another interview, this time with Sonic Boom (Peter Kember) from December 1999, where she stated that:

8I didn’t want to compromise my integrity any further. I was fed up with having my stuff turned down because it was too sophisticated, and yet it was lapped up when I played it to anyone outside the BBC. The BBC was very wary, increasingly being run by committees and accountants, and they seemed to be dead scared of anything that was a bit unusual. And my passion is to make original, abstract electronic sounds and organise them in a very appealing, acceptable way, to any intelligent person.8

After she left the BBC in 1973, Brian Hodgson, who had also moved on from the Radiophonic Workshop the year before, encouraged Derbyshire to join him at his new studio, Electrophon. Although Derbyshire is credited on-screen, alongside Hodgson, with providing the music for the horror film, The Legend of Hell House (1973), her mental health at this point was such that, according to Hodgson, her contribution to the production was minimal and the majority of the music was created by Hodgson in tandem with the uncredited Dudley Simpson.9 With her employment at the BBC now over, The Legend of Hell House marked a strange reversal of Derbyshire’s early career, where she tended not to be credited for her BBC projects—in this instance, she was receiving an on-screen credit when her work was apparently absent from the production.10

9What happened to Delia Derbyshire? Where did she go next and what did she do? The answers to those questions and the fact that those answers have so often fallen back on a mixture of myths and uncontested assumptions about Derbyshire also point to a wider set of challenges for art and cultural history when dealing with such a multimedia artist, whose creativity included popular and commercial forms, as well as the historical tendency for the role of sound and music to receive less attention in accounts of audio-visual works. The standard narrative of Derbyshire’s life is that her departure from the BBC in 1973 marked a complete withdrawal from creative activity in general and creating new music in particular, coupled with a decline into ill health until the last few years of her life, in the late 1990s and early 2000s, when she began to collaborate with the musician Peter Kember. Variations on that narrative can be found in numerous journalistic pieces about Derbyshire, dramatic works, fan overviews, and academic discourses. Bob Stanley’s 2003 item in The Times states that Derbyshire had “quit music in the early Seventies, but just before she died in 2001, she had started again, with Sonic Boom.”11 Jo Hutton’s initial 2008 entry on Derbyshire for the Grove Music Online encyclopaedia reported that: “she finally left the BBC in 1973 and put aside music composition for many years, until the late 1990s when she joined Peter Kember.”12 Similarly, H.J. Spencer’s overview of Derbyshire for the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography asserts that Derbyshire’s passion for music was “in abeyance for some years”, after she left the BBC and Electrophon.13 Elsewhere, Martyn Wade’s 2002 play for BBC Radio 4, Blue Veils and Golden Sands, portrays a Delia Derbyshire who lived alone throughout the last two decades of her life, with no mention of her enduring relationship with Clive Blackburn, her partner from 1980 until her death in 2001; instead, the play emphasises the revivifying impact of Peter Kember, who made contact with her in the 1990s. Nicola McCartney’s 2004 play Standing Wave, written for Reeling & Writhing at the Tron Theatre in Glasgow, has a non-linear narrative, moving back and forth between different points in Derbyshire’s life but all contained within a ten-year temporal pocket of 1963–1973, starting on New Year’s Eve 1973 with Delia in Cumbria and concluding with the sounds of the Doctor Who theme being broadcast for the first time in 1963. Once again, the account of Derbyshire’s life struggles to get far beyond 1973 and her departure from the BBC. Derbyshire’s Wikipedia entry nudges the cut-off point forward slightly but states conclusively that in 1975 “she stopped producing music”.14

11This general narrative has also been maintained by the scholarship on Derbyshire, which has begun to emerge in the last ten years. Louis Niebur, author of the first monograph on the Radiophonic Workshop, asserts that: “by the mid-1970s she had completely retired from music.”15 Teresa Winter’s thorough 2015 doctoral thesis on Derbyshire’s BBC work notes that: “after 11 years Derbyshire left her musical career in the early 1970s, emotionally and physically exhausted by the BBC’s ‘petty bureaucracy’” and that she only returned to music “during the last decade of her life.”16 Most recently, Frances Morgan’s 2017 article, which calls into question some of the myths and assumptions perpetuated by much of the discourse on Derbyshire’s life and work, summarises Derbyshire’s latter years by commenting how “soon after leaving the BBC in 1973, Derbyshire retreated from music, composing only in private, if at all,” despite offering a more nuanced summation of her post-BBC output elsewhere in the article.17

15This standard account was one that I subscribed to for several years and it is also one that was accepted by some of Derbyshire’s closest friends and colleagues. Brian Hodgson, for example, assumed that Derbyshire had withdrawn from music after she left the BBC, despite remaining in contact with her throughout the remainder of her life.18 At its crudest, it is all too easy to reduce this substantial period of Derbyshire’s life—the best part of thirty years—to the well-worn stereotype of the tragic self-destructive artist. When the existence of Derbyshire’s archive was first announced on the BBC in 2008, The Times ran an item by Russell Jenkins in which he summarised her life and career as follows:

1819Delia Derbyshire, who battled with depression and died, aged only 64, a hopeless alcoholic in 2001, was the godmother of modern electronic dance music. She carried out pioneering work for the BBC Radiophonic Workshop in the early 1960s, producing the familiar Doctor Who signature theme and collaborating with Brian Jones and Jimi Hendrix among others. … Ms Derbyshire was also a woman of her times, clad in Biba or Mary Quant, her hair in a Vidal Sassoon bob, a fixture at the parties of Swinging London where she was known for her chaotic but exuberant love life. She worked with … Yoko Ono … and met Paul McCartney to discuss an opportunity to work on Yesterday. She left the BBC a disillusioned woman. She struggled with drink and a series of unsuitable jobs, including radio operator. At one time, she married an out-of-work miner but eventually settled in the Midlands where she lived in relative obscurity and would rail, between drinks, against her lack of critical recognition.19

There are various misnomers and generalisations in the piece (not least the erroneous claim that Derbyshire collaborated with Jimi Hendrix—one can only dream of what extraordinary music they might have created had they collaborated) but it is telling how Derbyshire’s story is characterised not only through the familiar trope of the failed, self-destructive artist but also the emphasis on her lifestyle and the famous people, particularly men, that she knew rather than her own achievements as an artist. In the case of Paul McCartney, there is a curious overplaying of the project she might have done (the background to Yesterday) rather than the significant work that she did produce. This tendency to emphasise celebrity relationships, associations with “great men” and tragic decline is comparable to the “constant over-privileging of life over art”, which is interrogated by Kate Dorney and Maggie Gale in their collection of essays on Vivien Leigh.20 Informed by the Victoria and Albert Museum’s 2013 acquisition of Leigh’s personal archive, these essays move beyond the popular and journalistic accounts of Leigh that tend to address her primarily in the context of her relationship with Laurence Olivier. In a similar vein, this article draws on several years of extensive archival research and interviews with Derbyshire’s friends, colleagues, and her partner to complicate the standard narrative of Delia Derbyshire’s post-BBC career and reveals that, without denying the complications that she encountered during this often difficult phase of her life, Derbyshire remained both creatively engaged and active as an artist far longer than has often been reported or assumed. In particular, Derbyshire’s creative activity during these years saw her collaborating with visual artists, most prominently Madelon Hooykaas and Elsa Stansfield, as well as a period assisting the Chinese-born artist Li Yuan-chia at his celebrated LYC Museum & Art Gallery in north-east Cumbria. In doing so, Derbyshire furthered her long-standing interest in the relationship between music and the visual arts. The article thus provides not only a revisionist account of Derbyshire’s post-BBC activity but also enhances our understanding of experimental work exploring the inter-relationship between visual art, electronic sound, and music in Britain and the nature and extent of Derbyshire’s influence.

20Delia Derbyshire and the Visual

Derbyshire’s affinity for the visual arts and its influence on her approach to creating electronic sound and music can be traced back to her childhood. In 2011, the John Rylands Library acquired from Andi Wolf, the occupier of Derbyshire’s childhood home in Coventry, a substantial collection of Derbyshire’s schoolbooks, which provide a fascinating insight into her emerging artistic tastes and creative principles. The importance of music in her life is clear, with references to her favourite composers including Bach, Mozart and, especially, to Beethoven’s piano sonatas as well as her admiration for dances by Shostakovich. There is little, however, which appears to point directly to her later enthusiasm for electronic sound and music.

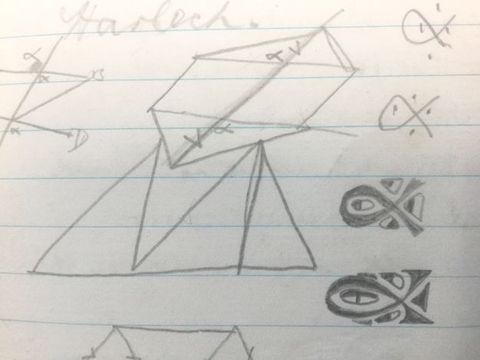

An interest in the potential of ordinary objects to make music and the transformation of everyday sound, which would be at the core of her adoption of musique concrète techniques in the 1960s, gathering and manipulating recordings of found sounds (her beloved metal lampshade being perhaps the most prominent), can nevertheless be identified in some of her school exercises, where she often refers to the sounds made by everyday objects.21 That sensitivity to the musical potential of the sound of “non-musical” objects is evident in her later recollections of the sound of air raid sirens during the Blitz in Coventry or the percussive clip-clop rhythms of factory workers’ clogs hurrying to work on the cobbled streets of Preston, where she was evacuated to for several years—an influence that is audible in the underlying rhythms of pieces such as Pot au Feu (1968) and Way Out (1969). More revealing, however, are the numerous “doodles” which appear throughout her various schoolbooks and seem to anticipate some of the recurring ideas at work in her approach to sound design and music that she developed at the Radiophonic Workshop. These drawings are often abstract, geometric patterns and miniatures, sometimes taking a basic element and then repeating the design but augmenting it further with each iteration. One of the most interesting sketches in this respect comes in her Lower Third homework notebook from 1950 (fig. 1).

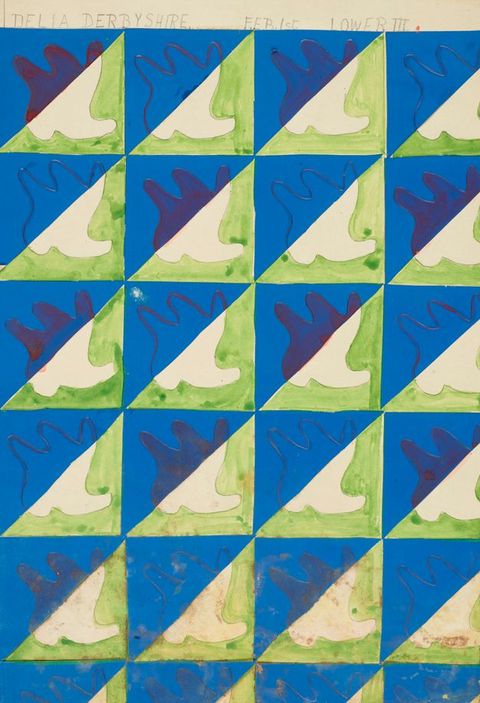

21It is not too fanciful to identify the origins of some of the core principles of Derbyshire’s later creative practice in these doodles: an interest in repetition and loops, taking a raw pattern or sound and embellishing it through gradual transformations, maybe augmenting the pitch or filtering the sound and adding further elements. Elsewhere there are variations and modulations of Derbyshire’s initials and doodles, which seem to echo her Catholic upbringing with suggestions of the sacred (fig. 2). Her school paintings also reveal a fascination with repetition and looped patterns (fig. 3).

A much more obvious influence in terms of the integration of electronic music and visual art was her experience of attending Le Corbusier’s Philips Pavilion, designed for the 1958 Brussels World’s Fair. Derbyshire travelled to Expo ‘58 with her friend and fellow music student from Cambridge, the composer Jonathan Harvey. As they entered and left the Pavilion, they would hear Iannis Xenakis’ musique concrète piece Concret PH (1958) and, within the Pavilion, Edgar Varèse’s Poème électronique (1958) was synchronised to a film of black and white photographs in addition to shifting patterns of coloured light. The music was diffused via a complex sound projection system, which employed several hundred speakers that could be activated in varying combinations to transform the nature of the sonic presentation and the spatialisation of Varèse’s composition. The experience had an undoubtedly profound impact on Derbyshire: within ten years, she was contributing to, as well as co-organising, immersive environments and events that brought visual projections and electronic music together, and an enduring interest in the relationship between music and visual art was cemented.

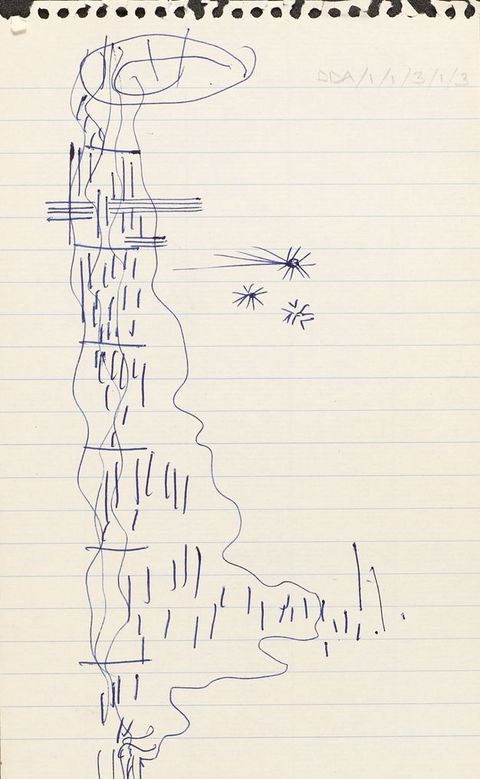

Derbyshire’s ability to “visualise” music impressed her first colleagues at the BBC, where she worked initially as a studio manager. She described her ability to pinpoint precisely where a requested extract on a record would begin by holding the LP up to the light so that she could “see the trombones” in the disc’s grooves “and put the needle down exactly where it was” much to the amazement of her peers.22 That affinity for the visual was deepened when she transferred to the Radiophonic Workshop in 1962 and quickly established her creative practice. Although she often employed conventional notation, her archive includes numerous instances where she makes use of more graphic approaches (fig. 4).

22

At the Radiophonic Workshop, Derbyshire had multiple opportunities to work on projects about key figures and movements in art history, particularly through her contribution to the educational “For Schools” programming on Radio 4. These programmes included a BBC 2 documentary about Henry Moore (I Think in Shapes, 1968), and two “For Schools” features in the “Art and Design” strand from 1968 and 1971, respectively (fig. 5). The first was on Cubism, written by Edward Lucie-Smith and featuring the poems of Apollinaire with an emphasis on Picasso and the parallels between Cubism and music; and the second on Eduardo Paolozzi. She also scored an edition of Omnibus, directed by Leslie Megahey, which focused on Goya—this was one of Derbyshire’s final works for the BBC, broadcast on 29 October 1972. The “Art and Design” radio programmes presented particular creative challenges as Derbyshire was required, as Desmond Briscoe noted, “to act as a link between the transparencies”, which were made available to some schools as well as conveying a sense of Picasso’s painting and Paolozzi’s sculpture through sound and music in a non-visual medium.23

23Lights—Sound—Installation! Collaborations with Hornsey College of Art

All of these projects came towards the end of Derbyshire’s time at the BBC but a far more important encounter at the Radiophonic Workshop took place much earlier, in 1965, and would have a significant impact on the nature of her freelance work outside the Corporation. The incident in question was a visit to the Workshop by the artists Clive Latimer and Michael Leonard and the result was a fruitful collaboration between Derbyshire and the Light/Sound Workshop (LSW) at Hornsey College of Art. The LSW was formed in 1963, in part by Latimer, and was part of the Advanced Studies Group at Hornsey under Latimer’s direction. The LSW was at the forefront of experiments in Britain to explore the relationship between sound and light projection. Their first professional performances took place in 1963, including a combination of lighting and image projection onto a cycloramic backdrop for the production Ex-Africa at that year’s Edinburgh Festival, which combined poetry, jazz, and dance with the LSW’s projections. The LSW’s own information sheet, compiled ahead of the 1965–1966 season, described its key objective as being:

24To develop a technique of projection light in which moving abstract colour images are correlated with patterns of sound. The essence of the technique is the use of continuous sequences of black and white or colour projection material in motion in one or more light beams. By the use of a number of layers of projection material in the light beam together with one or more light beams, a complex permutation of images is seen on the screen. This is further developed by optical means, mirrors, lenses and interference patterns. Movement is the basis of the technique and the development of control has been a major problem. The initial order of movement was left/right and up/down together with enlarging and diminishing the images. Further development in movement has extended our control so forms can explode or contract, move in spiral or wave motions, or fluid free movement. … The relationship between the moving image and sound is the essence of our technique. Image sequences can be developed to existing music but the use of electronic music and music concrete allows greater freedom and closer integration of sound and image. The most obvious relation of sound to image is a direct parallel, sharing rhythm and mood. More difficult is to set sound in counterpoint to the image—for example, soft fluid sounds can be set in contract [sic] with sharp broken images. Experiments linking new patterns of sound with new operating techniques are continually being investigated by Michael Leonard.24

The document identified the Light/Sound Workshop’s future priorities as including the development of architectural lighting and kinetic sculptures, and both of these aims were furthered through collaborations with Delia Derbyshire across 1966 and 1967. It is not surprising that, given the document’s identification of the benefits of electronic music and musique concrète, Latimer and Leonard would seek out the Radiophonic Workshop and establish a constructive dialogue with Derbyshire, which took root in 1965. They were not alone in seeking to collaborate with the Radiophonic Workshop to research the relationship between electronic music and image—since its establishment in 1958, the Radiophonic Workshop’s reputation had increased substantially, and by the mid-1960s had an international reach. The Academy Award-winning animator, Derek Lamb, then a Lecturer in Light and Communications at Harvard University’s Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts, wrote to Briscoe on 26 September 1966 stating that he had heard “a lot of complimentary things about your workshop’s compositions and experiments in electronic music” and asked if it would be possible to have tapes of the Workshop’s music to use as a soundtrack for visual experiments in film and animation at Harvard.25 Later that year, Robert Hyde, Lecturer in Fine Arts at Wimbledon School of Art, also contacted the Radiophonic Workshop to discuss the incorporation of electronic sound in his environmental conjunctions of structures, coloured light, projections, and movement.

25Leonard wrote to Desmond Briscoe on 19 May 1965 thanking him for the opportunity to visit the Radiophonic Workshop and discuss electronic music with Briscoe and his staff, offering, in return, a visit to the Light/Sound Workshop “to show you our own techniques of light projection”.26 The possibility of the two facilities collaborating, perhaps gathering on an evening to see how “visual material could be related to any existing tapes” or developing an improvisation around Radiophonic Workshop material, was suggested by Leonard and Derbyshire seems to have responded enthusiastically.27 She was the member of the Radiophonic Workshop who engaged most extensively with visual artists interested in working with electronic sound, and that was manifest most prominently in her freelance activity with Unit Delta Plus.

26

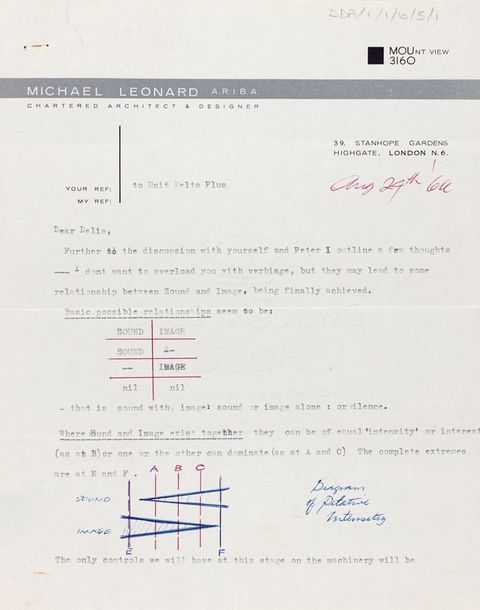

Although short-lived, Unit Delta Plus (Derbyshire, Brian Hodgson, and Peter Zinovieff) held or contributed to a number of innovative events that experimented with sound, light, and image projection. The first of these was a concert at the fledgling Watermill Theatre, Bagnor on 10 September 1966 (the Watermill had only just been converted and would not produce its first professional season of theatre until the following year, in 1967). Billed as “Unit Delta Plus Concert of Electronic Music”, the event was a genuine collaboration between Derbyshire, Hodgson, and Zinovieff and the Light/Sound Workshop. Correspondence between Michael Leonard and Unit Delta Plus reveals that considerable thought was given to how the sound and images should interact, and Leonard met with Derbyshire to discuss possible approaches to the relationship between the sound and light projections at the event. This relationship was founded on variations of four basic patterns: sound with image; sound or image alone; no projected sound and image. Within those basic configurations, there was the scope for more nuanced and complex interactions, including visual and audio fading, the movement of images in relation to sound, and shifts in both audio-visual intensity and the location of the audio through the placement of speakers (fig. 6).

Leonard suggested that the voices in the programmed 15-minute extract from Amor Dei (1964), Derbyshire’s acclaimed 45-minute collaboration with the dramatist Barry Bermange, in which a poetic collage of the voices of everyday people discussing their feelings about God were set to Derbyshire’s ambient transformations of a chorister singing, could come from all points around the audience with each voice from a different speaker. Although that proposal would be too difficult to achieve given the amount of voices in the piece and the way it was mixed and recorded, there are notes in Derbyshire’s archive on when to fade up certain speakers with the most complex arrangements for Amor Dei, and simpler instructions for Zinovieff’s Tarantella (1966) and her Moogies Bloogies (1966). Derbyshire was pivotal in the event’s development, securing permission to use an extract from Amor Dei for “a non-profit-making concert of electronic music, to be given before an invited audience at a private theatre” that “I am organising.”28 In addition to featuring existing and solo works by Derbyshire (Pot Pourri from 1966, as well as Amor Dei and Moogies Bloogies), Zinovieff, and Hodgson, the concert also included a new three-part 20-minute piece, Random Together 1, by Zinovieff and Derbyshire. The first and last parts of the piece were “composed with light projection in mind”, whereas the central section was played without visual accompaniment as it was “musically self-sufficient”.29 The projections were abstract in nature and, as Brian Hodgson recalls, took the form of slowly moving coloured oils, oozing around “like a flattened, multi-coloured lava lamp”.30 This was a significant event, pre-dating some of the more prominent concerts of electronic music held in Britain in 1968 and, according to Hodgson, it was very successful.31 The distinctive addition here was the visual interaction. As well as the projections from Hornsey College’s Light/Sound Workshop, the hour-long interval gave attendees the opportunity to explore an exhibition of paintings by Zinovieff’s five-year-old daughter, Sofka, and a moving electro-magnetic sculpture by Takis, who had begun to develop his sculptures musicales in the previous year and had exhibited his electro-musical relief at the Indica Gallery in London, in the same year as the Bagnor concert—1966.

28Unit Delta Plus followed the Bagnor concert with their participation in another event bringing together sound and light projections: the Million Volt Light and Sound Rave, held at the Roundhouse in London on two nights in late January and early February 1967. This particular happening has acquired legendary status through the involvement of the Beatles and their Carnival of Light piece, which has still to receive an official release, having been vetoed by surviving members of the group, despite Paul McCartney’s wish to put the recording out. There is little documentation confirming the full extent of Derbyshire’s involvement at the event and how the Unit Delta Plus material might have interacted with the visuals. For Brian Hodgson,

32As usual in those days it was complete chaos no one really knowing what was going on lots of noise and people milling about we eventually found someone to take charge of [Paul McCartney’s] tape and after a few minutes we left and went to the pub. I have no recollection of whatever, if anything, was played from Delia or Unit Delta Plus.32

Far better documented is Derbyshire’s contribution to the K4: Kinetic Four Dimensional immersive environments that were installed on the West Pier as part of the first edition of the Brighton Festival, across 14–30 April 1967. These “kinetic/audio/visual environments”, incorporating the mechanical sculptures of Bruce Lacey and music of Pink Floyd, were instigated by the Light/Sound Workshop. Four distinct environments were outlined by Clive Latimer in November 1966: Kinetic Arena, Kinetic Labyrinth, The Dream Machine, and Balloon Structures (aerial structures of helium-filled balloons, which were to be tethered over the pier and floodlit at night). Kinetic Arena was designed to be a large-scale social space for dancing with thirty loudspeakers providing a sense of surround sound and continuously developing moving images projected onto a white elliptical cyclorama. Conversely, Kinetic Labyrinth was intended to be “a more enclosed and personal experience”.33 The Labyrinth was to showcase the work of British and international kinetic artists, with an emphasis on generating a contemplative mood through colours and images being projected onto Perspex walls with sonic accompaniment, shifting to pulses of light, strong colour, and a sense of “illusion and disorientation”.34 The Dream Machine was intended to provide an even more intimate experience, aimed at the solitary individual with the emphasis on fantasies and creating in the subject a sense of being immersed within the image. Building on their earlier work together, Michael Leonard wrote to Derbyshire on 13 December 1966 to confirm that the project was going ahead and that the LSW would require at least half an hour of electronic sound from Derbyshire with individual pieces structured to the requirements of the programme, ranging from 3 to 10 minutes in duration.35

33Derbyshire’s audio archive at the University of Manchester contains two tapes with labels referring to the Brighton Festival event: one is labelled “Extracts from Brighton Festival” and runs for just under 4 minutes and the second is labelled “2 Bands—Labyrynth, Beachcomber for Brighton Festival 1967” and contains two cues running for just under 8 minutes and 8 minutes 30 seconds, respectively. The majority of these cues for the K4 environments comprised collages, re-edits, and transformations of some of Derbyshire’s existing work segueing into fresh configurations but there is original material as well. “Labyrynth” (which is spelled “Labyrinth” elsewhere in Derbyshire’s archive) is an extended edit of the ambient backgrounds from the “underwater” movement of The Dreams (1964), the first of the four Inventions for Radio that Derbyshire collaborated on with Barry Bermange, in which members of the public discussed their dream experiences, including dreams of drowning or being submerged beneath the waves. This material would be re-edited again by Derbyshire into The Delian Mode, running at 5 minutes 38 seconds and released on record in 1968. The mood is sombre, spacious, and haunting, with slowly undulating drones interrupted by pools of metallic sound, evocative of muted depth charges, with sounds generated from the bell-like tones of a metal lampshade. It is not clear from Derbyshire’s notes which of the K4 environments each cue was intended for but there are clear parallels (beyond the obvious shared name) between the contemplative mood described by Latimer in Kinetic Labyrinth and the sonic properties of Derbyshire’s cue “Labyrynth”.

If "Labyrynth" was a relatively uncomplicated extension of her existing material, "Beachcomber" is a far more dynamic reinvention of some of Derbyshire’s earlier work, combined with new elements. The cue makes substantial use of familiar rhythmic passages that feature in Pot au Feu and Way Out, specifically the percussive, clicking “clip-clop” rhythms and bass pulse, but repeatedly alters their speed and pitch so that the familiar material is often difficult to discern: in some instances, the pitch and speed of the material has been changed so much that the clicking rhythms sound like a chorus of tropical frogs and cicadas giving the piece a throbbing, organic quality. After an opening sequence of the percussive material gradually increasing in pitch until it takes on its recognisable form, the melody from Way Out, sourced from a sine wave oscillator, is introduced before the piece segues into further transformations of the percussive material, combined with waves of white noise that subside into a more spacious, floating sequence accompanied by rising and falling phrases of surf guitar and simulated waves. The final stages of the cue transition into material from Moogies Bloogies and Way Out segueing together in fresh configurations. The cue as a whole is an excellent example of Derbyshire’s ability to re-work her “back catalogue” of sound sources and isolated elements from her existing creations into distinctive new forms that relate to their context—in this instance, Derbyshire responds playfully to the seaside setting of the K4 environments on the West Pier with a coastal soundscape that takes the listener to a fantasy beach and electroacoustic Everglades beyond the immediate locale (fig. 7).

This re-purposing of existing material was true of Derbyshire’s final collaboration with Leonard, The Coloured Wall at the Association of Electrical Engineers Exhibition at Earls Court, which opened in late March 1968 (and featured, again, elements from Moogies Bloogies and Way Out as well as her special sound for Ron Grainer’s musical On the Level [1966] and the film Work is a Four Letter Word [1968]). By now, Unit Delta Plus had folded and Derbyshire’s freelance activity was done through Kaleidophon. The Light/Sound Workshop would soon be at an end as well. Clive Latimer was expelled from his post at Hornsey College of Art after he supported the student uprisings of May 1968.36 The 1960s closed with Derbyshire having generated considerable experience from collaborating with and advising visual artists interested in the possibilities of electronic sound and music. Although the following decade would bring major changes in the nature of her creative activity, her interest in and involvement with visual art would continue as a crucial and rewarding aspect of her life.

36Free as a White Bird: Collaborations with Stansfield/Hooykaas

If the collaboration with Hornsey College of Art’s Light/Sound Workshop was the most significant that Delia Derbyshire had with visual artists in the 1960s, then her most important collaboration in the 1970s was with Stansfield/Hooykaas. Working initially under the title “White Bird”, Stansfield/Hooykaas was the collective name for the Scottish artist Elsa Stansfield and the Dutch artist Madelon Hooykaas. The two first met in London in 1966 but began their lengthy collaboration in 1972. Over the course of the following thirty years, Stansfield/Hooykaas would create a rich body of work that integrated aspects of art and science with a particular interest in time and memory. Training as visual artists (painting; and drawing and photography, respectively), their initial collaborative projects were in film but, in the mid-1970s, they transferred their attention to video and gallery installation pieces, being among the first European artists to have videos exhibited in gallery spaces. Starting with What’s it to You?, exhibited at Glasgow’s Third Eye Centre in 1975, Stansfield and Hooykaas helped, as Malcolm Dickson asserts, “to define the expanded area of video installation”.37 They collaborated with Derbyshire on two films, Een van die dagen (One of These Days) in 1973 and Overbruggen (About Bridges) 1975, but Derbyshire’s influence would remain a tangible presence in many of their video and installation works into the 1980s and beyond.

37Derbyshire had already worked with Stansfield on the award-winning art film Circle of Light (1972). Directed by Anthony Roland, the film shimmers and drifts through the luminous and haunting photography of Pamela Bone: uncanny evocations of beaches, marshland, forests, and sunsets. With the exception of a brief introduction from Bone, the film is wordless, set to a slowly shifting soundscape of natural, elemental sounds and animal calls, blended with Derbyshire’s music at its characteristic ambient best. Derbyshire re-purposes some of her favourite material (the resonances of her beloved metal lampshade, heard most famously in her piece Blue Veils and Golden Sands from an episode of the factual series The World About Us broadcast in 1968 on the Tuareg nomads in the Sahara) but integrates new elements as well into a sensitively crafted whole. The film won first prize at the Cork International Festival with subsequent screenings around the world. The sound is credited to both Stansfield and Derbyshire; Hooykaas has confirmed that Stansfield was responsible for the vast majority of the recordings of natural sound, but a precise account of who was responsible for what and how Stansfield and Derbyshire collaborated is impossible to determine from the available evidence.38

38That positive experience resulted in Derbyshire being commissioned by Stansfield and Hooykaas for their first full collaborative film, One of These Days. Stansfield was now established at her new studio facility—8, 9 and 10—named after its location in Neal’s Yard, Covent Garden above the market. The space was converted and equipped for editing as well as animation and it was here that Brian Hodgson founded Electrophon, after he left the Radiophonic Workshop in 1972. Derbyshire completed the music for both One of These Days and About Bridges at the Electrophon facility, the second project being undertaken after she had left the BBC in 1973. One of These Days was shot in Amsterdam and Rotterdam during October 1972 and Derbyshire was involved from an early stage of the production. Hooykaas and Stansfield were keen to avoid the usual practice of handing a completed film over to the composer and invited Derbyshire to attend the shooting in Holland, so that she could become fully immersed in the aims of the project.

Of the two films, there is a more heightened sense of tension and dialogue between Derbyshire’s music and the film’s images and narrative content in One of These Days. The 30-minute film is a portrait of the artist Marte Röling. We follow Röling through her bohemian lifestyle with her friends, see her at work, planning to paint a ship with multiple images of mouths, contemplating her appearance, her life, how she will be in old age and adopting children as she travels around and between Amsterdam and Rotterdam, combined with the voices of other people on different aspects of life and death. The film takes what Hooykaas describes as a “tongue in cheek” and somewhat critical approach to Röling and that comes across most potently in the contrast between what we see, Röling’s words and Derbyshire’s music.39 Much of Derbyshire’s score is founded on the repetition and augmentation of specific words, underlining her fondness for the human voice as a sound source to be transformed: “mouth”, “dream”, and “beautiful” often appear to undermine Röling’s views or suggest a self-absorbed nature. Early in the film, we see Röling eating and drinking with friends after a party, as she discusses in voice-over her plans to paint and various relationships, but the sincerity of her plans and comments on her friendships are offset by Derbyshire’s incessant, hypnotic repetition of "dream."

39One of the most striking passages of the film, in terms of audio-visual tension, is a near 4-minute sequence of Röling travelling by train. As she reflects on how she is curious to know what she will be like in old age, Derbyshire’s rapid oscillations rise in pitch to create the impression of time running out, hurtling Röling towards oblivion (fig. 8).

About Bridges combines melancholic treated trumpet phrases with child-like nursery rhyme melodies played by a synthesiser. In both films, Derbyshire creates fresh material without revisiting sounds from earlier projects, almost certainly a result of being brought into each production at an early stage and, in the case of About Bridges, being free of any BBC commitments. For Derbyshire, the collaboration was especially rewarding and, as her partner Clive Blackburn acknowledged, she loved working with Hooykaas and Stansfield.40

40One of These Days and About Bridges were screened on Dutch television and at international festivals, in cities including Toronto, New York, Grenoble, and Rotterdam. But Stansfield and Hooykaas were frustrated at the limited exposure their work was receiving and the high cost of film-making. Instead, they “much preferred to see our work shown in a visual arts context. By making our own exhibitions and being present there, we hoped for a more immediate, personal response.”41 In 1975, Stansfield/Hooykaas began making videos to be presented and installed in galleries and site-specific environments. The lower costs of video production meant that it was difficult to commission original scores, so Elsa Stansfield instead created the soundtrack for many of these video pieces. Nevertheless, Derbyshire’s presence is clearly audible in much of this work. In fact, Labyrinth of Lines (1978) uses direct samples from Derbyshire’s score for One of These Days, but on video works such as See Through Lines (1977), Running Time (1979), Transitions (1979), Two Sides of the Story (1981), Vi Deo Volente (1985), and Point in Time (1987) there is a recognisable “Delian” aesthetic in play: sustained drones and rhythmic sequences or ambiences generated from looped and augmented everyday sound sources.

41If Elsa Stansfield was responsible for the “natural” sound in the earlier films with Derbyshire, these later works often find her creating and manipulating found sound as Derbyshire did (e.g. electricity pylons in the case of Point in Time or a looped and treated heartbeat in Running Time).42 As Hooykaas acknowledged, “I’m sure they influenced each other—I learnt myself a lot from Elsa and probably also from Delia about sound because now I’m making my own soundtracks … people like [John] Cage … [and] Delia have influenced me enormously.”43 This exchange of ideas, knowledge, skills, and techniques—a dialogue furthered by Derbyshire and Stansfield working alongside each other in the same facility at 8, 9 and 10—is consistent with Freida Abtan’s observations about the importance of “community-building and skills-sharing practices to help women engage with electronic music culture,” which has otherwise privileged male inclusion and success.44 Instead of emphasising the lone, exceptional genius, Derbyshire’s collaborations, taking in her work with the Light/Sound Workshop, are an example of Brian Eno’s concept of “scenius”, which places the emphasis instead on “the creative intelligence of a community” with the innovations of individuals dependent on an “active flourishing cultural scene”.45 Hooykaas’ deep interest in Zen Buddhism (she spent time in a Japanese monastery prior to her partnership with Stansfield) finds parallels in Derbyshire’s predilection for meditative, trance-like ambient passages and rhythmic loops, often sculpted from the sound of everyday objects and elements. In doing so, Derbyshire’s approach to much of her music was a clear kindred spirit for the future video/work of Stansfield/Hooykaas. Janneke Wesseling identifies the commitment of Stansfield/Hooykaas to the principle that:

4246Being one with nature means being one with the wind, with the ebb and flow of the tide and with the changing seasons. But Stansfield/Hooykaas are also fascinated with other, invisible forces of nature such as magnetic fields, radio waves and electricity. In their work they show how everything that exists is intertwined. Everything, from a rock to a rose, is animated with movement and change.46

That ethos is present in Derbyshire’s love of the music in the sounds around or within us, whether that was a knock on the door, a clap of thunder, a metal lampshade, or one’s own voice and breath.

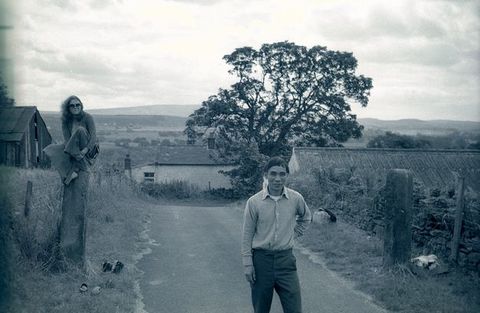

Cumbria and Beyond the Radiophonic

By the time About Bridges was released in 1975, Derbyshire had long since left London and relocated to the north of England, near the border between Cumbria and Northumberland, but her contact and creative interaction with Elsa Stansfield and Madelon Hooykaas was far from over. She was employed initially as a radio operator for Laing’s gas pipeline, liaising with French personnel in a major pipe laying operation, and it is generally from this point on that the standard accounts of her life tend to assert that she was no longer active as a musician. Her creative activity, however, would resume in a professional capacity when she assisted the Chinese artist Li Yuan-chia at his LYC Museum & Art Gallery. This was no conventional museum or gallery. The range and influence of Li Yuan-chia’s visionary practice and philosophy has escaped the attention of many accounts of late twentieth-century art history. As Diana Yeh surmises, Li’s “extraordinarily eclectic art practice”, running across painting, sculpture, poetry, calligraphy, and videography, has proven difficult to place and categorise.47 For Guy Brett, “the fact that Li Yuan-chia has been missed by the art establishments of so many countries suggests that they have no instruments fine enough to detect a journey [and influence]” that was otherwise known to many people and had a considerable and lasting influence.48 The ultimate expression of Li’s thought and practice was the LYC Museum & Art Gallery. Li founded the LYC in 1972, buying and renovating a run-down farmhouse from the artist Winifred Nicholson and transforming it into a remarkable community arts space complete with a children’s room, print room, library, and space for visiting artists to stay and exhibit their work. All of this took place in the hamlet of Banks, right beside the line of Hadrian’s Wall and the LYC remained open until 1982 (Figs. 9, 10, and 11).

47

Derbyshire was living in the nearby village of Gilsland, where she had married David Hunter, a local labourer, in the hope of being accepted by the rural community, where she was conscious of her outsider status. The marriage was not a happy one. Instead, Derbyshire was drawn to the artistic vibrancy of the LYC, where she worked across 1976 and 1977 for little money but could stay for free.49 The Times had printed a feature on the LYC in 1974 and observed that Li needed “help in running the museum, and he desperately needs an assistant to take some of the load off his own back.”50 Staying at the LYC, Derbyshire gave Li crucial support in running the Museum and Gallery. According to her future partner, Clive Blackburn, “Delia loved [the LYC] because of all the visiting artists and sculptors … she used to spend ages talking with them … she loved mixing with any sort of creative people really not just in the music field.”51 Her role was primarily to help arrange exhibitions, liaise with the artists, and entertain them during their stay. In this respect, Derbyshire was drawing on her existing organisational skills—she had managed the Radiophonic Workshop when Desmond Briscoe went on leave and had experience of organising complex artistic events as demonstrated by the Unit Delta Plus concert at the Watermill.

49In the 1977 season overseen by Derbyshire, the LYC exhibited the work of Winifred Nicholson, Charlie Brown and Eddie O’Donnelly, Nanea Bell, Thetis Blacker, Alex Fraser, David Trubridge, Elizabeth Tate, Antoinette Wijnberg, Niek Welboren, Jim Gavin, Ralph Bell, David Johnstone, and Syl Macro, as well as Li Yuan-chia himself and Derbyshire’s friends and former collaborators Madelon Hooykaas and Elsa Stansfield, who visited Derbyshire on several occasions during her time in Cumbria. This was not exactly a remote, isolated existence. Banks is close to the main road—the A69—between the cities of Newcastle and Carlisle and the rural soundscape with the Pennines to the south and Lakeland fells to the south-west would be interrupted intermittently by the nearby train line or, as Guy Brett notes, “the terrifying scream of low-flying fighter jets, emanating from the RAF base at Leeming.”52 Numerous visitors would pass through Banks on their way to and from Hadrian’s Wall, whether or not the LYC was their planned destination—around 30,000 a year at the height of the LYC’s success. Neither was Derbyshire’s life devoid of music during her time in Cumbria. According to Clive Blackburn, she still possessed two pianos, her much-loved spinet (which provided what Blackburn describes as a form of therapy as Derbyshire delighted in playing the instrument loudly so that she could “drown” in its sound), an electric organ, and VCS3 synthesiser.53

52At the LYC, Li Yuan-chia would have been another kindred spirit in his openness to the integration of different forms of expression and the music of everyday objects. Guy Brett, who had assisted Derbyshire and Zinovieff with borrowing work by Takis for the 1966 Watermill event, notes how Li “had a dream of how ‘painting, sculpture, architecture, environment, poetry, photography, embroidery, touch, sound, and so on’ might be combined in a kind of creative explosion participated in by everyone,”54 and this vivid description could be applied easily to Derbyshire’s experiments with the Light/Sound Workshop. Given that shared interest, it is hard to imagine that Li and Derbyshire did not discuss the possibilities of bringing music, sound, and visual art together. There is no conclusive evidence, however, which points to any concrete results of creative dialogue between the two. Li’s archive, also housed at the John Rylands library, includes a 45-minute cassette from the 1980s titled Time Toy No. 1 Symphony, which is an untreated recording of the clock mechanisms and chimes in several of Li’s reliefs. Derbyshire had created cues for various projects using the sound of clocks and simulated mechanical workings (The Tower [1964], for example, uses the sound of the clock mechanism inside Big Ben and much of her work for On the Level simulates the sound of machine rhythms). There is no sonic manipulation at work in Time Toy No. 1 Symphony and it is difficult to hear any overt trace of Derbyshire’s influence in the recording beyond a mutual interest in the potential of everyday objects to create music.

54Derbyshire might not have been involved with any new projects as a musician during her time in Cumbria but she remained, as Brian Hodgson reflected, “fascinated by the act of creation” and her work at the LYC required her to be creatively and artistically engaged.55 Nonetheless, the years that she lived and worked in Cumbria were not easy for her.56 She clearly connected with the region—in 1977, she wrote to Desmond Briscoe congratulating him on his recent radio feature A Wall Walks Slowly: The Sound of Cumbria, which provided a portrait of Cumbria through the poems of Norman Nicholson and the words of the Cumbrian people with the result being, as she said “effortless and extremely evocative—curlews and rainbows and the music of local voices—perfect for early on a Sunday evening.”57 Yet this was also a time of uncertainty for Derbyshire. The Li Yuan-chia Archive at the John Rylands Library contains a book, gifted to Derbyshire in December 1976 from Madelon Hooykaas, with Hooykaas providing an inscription that is revealing of some of Derbyshire’s prevailing concerns: “Freedom isn’t doing what you like, but liking what you do.” By 1978, Derbyshire had returned to London and, having met Clive Blackburn, she would move to Northampton with him in 1980, leaving her cat, “Horribles”, with Li Yuan-chia. Relocating to Northampton enabled her to be close enough to meet with friends in London and also make visits to her mother in Coventry. For Hodgson, Derbyshire’s relationship with Blackburn meant that “probably for the first time, she found happiness and settled into what, for her, was a normal existence.”58

55She continued to be interested in music and, contrary to the vast majority of reports about her post-BBC creative activity, still took on the occasional project. In the late 1970s, she collaborated with the Polish artist Elisabeth Kozmian on her “experimental documentary” Two Houses (1980), having been recommended and introduced to Kozmian by Madelon Hooykaas and Elsa Stansfield at their docklands studio in London. Kozmian was fascinated by Derbyshire: “a cheerful majestic figure”.59 Following the creation of a trial draft theme at a recording studio in London, Kozmian commissioned Derbyshire. The result was a wholly original and lyrical score for piano. The film was funded by the Arts Council and consists of a series of re-photographed colour slides, seen variously in negative and colour, and the voice-overs of the owners of two houses in the process of renovating their respective new homes in Kentish Town, North London. There is, for Kozmian, an emphasis on decay and Jungian notions of the house as a symbol for the Self, with the process of renovation likened to the process of working on and renewing one’s own Self.60 That sense of restoration from decay is conveyed in the ascending flourishes of Derbyshire’s opening cue, a sense of (re)awakening, furthered by the nature of the sound of the piano—this is not a pristine sound but something old and neglected returning to life (fig. 12).

59It is tempting to consider connections between the film’s subject matter, thematic concerns, and Derbyshire’s own life at that time, having recently returned to London from Cumbria. Certainly there is a feeling of new beginnings in Derbyshire’s score. Kozmian was delighted with the music and sense of “quiet continuous action” it gave to the film, although it is far from ever present.61 Two Houses was screened at the Institute of Contemporary Art in London and at various other one-off events but Derbyshire’s involvement was little known and unreported in accounts of her work until a remastered edition of the film, facilitated by the author and Mark Ayres, was screened at Manchester’s HOME in 2016 and BFI Southbank in 2017 as part of events celebrating Derbyshire’s film collaborations with visual artists.

61Two Houses finds Derbyshire active as a composer and collaborating on a project over six years after her assumed withdrawal from creative activity. In 1980, Kozmian discussed with Derbyshire a second film project, Clothes, but this was never realised beyond a single 90-second demo cue. The two met in a London recording studio, where Kozmian sang an old Polish folk song that provided the inspiration for Derbyshire’s cue: a gentle synthesised wordless lullaby with a sense of the sacred (not dissimilar to the tone of much of Derbyshire’s score for Amor Dei). Kozmian recalled a man “recording and playing with that singing electronically”, which suggests that Derbyshire might have employed a vocoder to create the finished effect.62 Whatever the instrument, the cue provides a tantalising glimpse of what might have been in the project with Derbyshire utilising a form of technology she had not used before (fig. 13).

62Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Derbyshire was approached to participate in various projects with her usual response being to say “no I’m not working anymore”—but there were exceptions.63 Clive Blackburn recalls her working at Adrian Wagner’s studio, which gave her access to equipment she needed, where she created the title music for a factual programme about Stonehenge.64 Privately, she and Blackburn worked on and recorded some songs for their own interest and pleasure but these were never released and that is, perhaps, the way they should remain, which might frustrate the completist impulse shared by many fans, collectors, and academics (this one included!).

63It is all too easy, as we have seen, to characterise this lengthy period of Derbyshire’s life as one of failure and defeat, unfulfilled potential and “hopeless” waste. To do so, however, is to deny Derbyshire any agency in her decisions to not release private material, turn down requests to compose or leave the BBC, and explore rewarding and meaningful alternatives in her life that do not correspond with assumptions about what a successful artist should be. None of this is to deny or diminish the difficulties that she faced at this time, including her dependency on alcohol and turbulent marriage to David Hunter. There is a danger, though, which Frances Morgan articulates, in projecting, however well-intentioned, masculinist narratives onto Derbyshire, in this case as “a vulnerable figure lost to history, not least in the insistence that she has needed rescuing or rehabilitating from historical neglect … and casts her as dependent on the heroic efforts of her rescuers.”65 Derbyshire’s departure from the BBC was an act of self-preservation and the years in Cumbria show her displaying her characteristic resourcefulness rather than needing rescue. Far from undertaking “a series of unsuitable jobs”, she was much admired among her colleagues for her work as a radio operator and her role at the LYC Museum & Art Gallery built directly from her love of and involvement with visual art, as well as her substantial experience in event and studio management. Derbyshire was part of a network of shared conversations and interests that ran through her activity as a BBC employee and freelance practitioner in the 1960s and early 1970s, and continued through her work with Madelon Hooykaas and Elsa Stansfield, as well as her time at the LYC. This way of thinking about Derbyshire complicates the “heroic pioneer” and “exceptional lone female narrative”, which has been critiqued by, among others, Tara Rodgers and Frances Morgan for presenting women as isolated points and sidelining “other networks, collaborations, grassroots feminist activities, and the presence of lesser known figures”.66 In Derbyshire’s case, it is a network that reaches across different forms of practice with Derbyshire’s creativity manifesting in unexpected ways.

65Her life, career, output, and influence was complex and more diverse and significant than we have assumed, taking in experiments in the audio-visual relationship and ground-breaking figures in video art as well as her more familiar achievements in electronic music. Delia Derbyshire continues to surprise and confound easy categorisation but that is something to be celebrated, however problematic it might be for neat overviews and headlines about her body of work—her example is a reminder of the need for more nuanced narratives that are equal to the collage of challenges, the often sudden disruptions, delights, departures, and mysteries that form the cut and spliced nature of our lives.

Acknowledgements

This article would not have been possible without the great generosity and support of Mark Ayres, Clive Blackburn, Joy Dee, James Gardner, Brian Hodgson, Madelon Hooykaas, Elisabeth Kozmian, Janette Martin, Jenn Mattinson, Louis Niebur, Joyce White, and Teresa Winter.

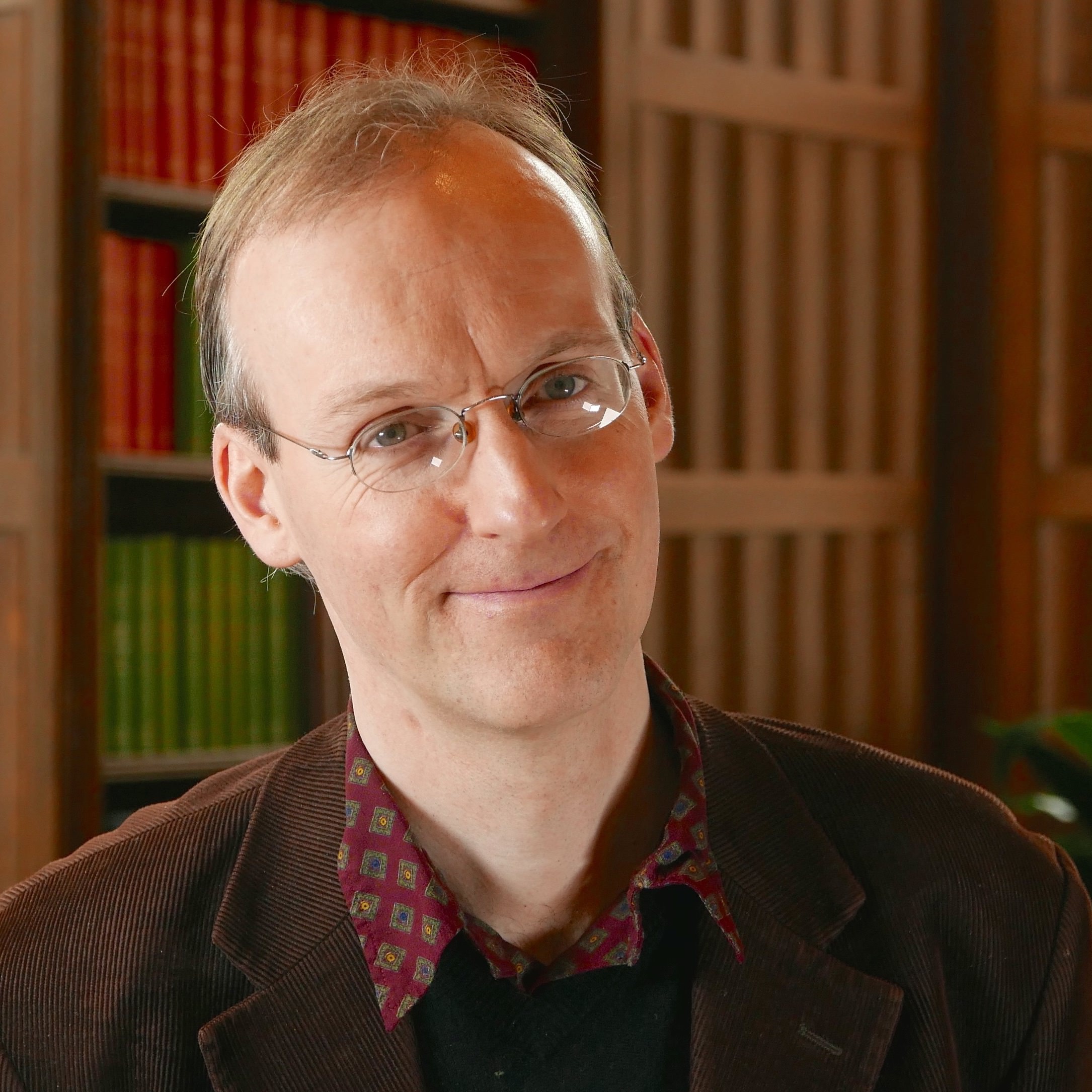

About the author

-

David Butler is Senior Lecturer in Drama and Screen Studies at the University of Manchester. He is the editor of Time And Relative Dissertations In Space: Critical Perspectives on Doctor Who (2007), author of Fantasy Cinema: Impossible Worlds on Screen (2009) and has written widely on the role of music in film and television as well as aspects of film noir, fantasy, and science fiction. He is currently one of the lead researchers and curators of the Delia Derbyshire Archive, housed at the John Rylands Library.

Footnotes

-

1

Russell Jenkins, “Delia Derbyshire, Producer of Doctor Who Theme Music, has Legacy Restored”, The Times, 18 July 2008. ↩︎

-

2

“ADS Demo (YAMCO)”, DD180, Delia Derbyshire Archive, John Rylands Library. ↩︎

-

3

For a more extensive discussion of the impact and reception of Derbyshire’s work in the 1960s, see David Butler, “‘Way Out—Of This World!’ Delia Derbyshire, Doctor Who and the British Public’s Awareness of Electronic Music in the 1960s”, Critical Studies in Television 9, no. 1 (2014): 62–76. ↩︎

-

4

Caroline Oakes (ed.), Festival of the City of London: Festival Programme (London: Westerham Press, 1970), 15. ↩︎

-

5

The reasons for Derbyshire’s departure from the BBC have been addressed in works such as Martyn Wade’s 2002 BBC Radio 4 play Blue Veils and Golden Sands or Noctium Theatre’s 2017 stage play Hymns for Robots. For Clive Blackburn, Derbyshire’s partner from 1980 until her death in 2001, “I think she was burnt out and needed some time off … I think she was doing too much—at the same time at the BBC she was working at Kaleidophon virtually not getting any sleep—working for the BBC during the day and at Kaleidophon all night—I think that’s how she got addicted to alcohol.” Clive Blackburn, interviewed by the author, 15 March 2018. ↩︎

-

6

Brian Hodgson has identified the problematic production of Tutankhamun’s Egypt as marking the real beginning of Derbyshire’s “disintegration”. This thirteen-part factual series was one of the last major projects that Derbyshire worked on at the BBC, with the first episode being broadcast in April 1972. According to Hodgson, Derbyshire began the project enthusiastically and had mapped out her concept for the full series but the production schedule was changed late in the day with the transmission order of the respective instalments being swapped, resulting in Derbyshire still working on rescheduled episodes as they were being dubbed—“that’s when she really started withdrawing from everything” and that in general “the pressures of the deadlines were becoming more and more and she hated pressure.” Brian Hodgson, interviewed by the author, 12 August 2015. ↩︎

-

7

John Cavanagh, “Delia Derbyshire: On Our Wavelength”, Boazine 7 (1998), http://www.delia-derbyshire.org/interview_boa.php. ↩︎

-

8

Sonic Boom (Peter Kember), “Delia Derbyshire Interview”, Surface, May 2000, http://delia-derbyshire.org/interview_surface.php. ↩︎

-

9

Hodgson interview, 12 August 2015. ↩︎

-

10

According to Hodgson, Derbyshire’s role on The Legend of Hell House was “confined to having dinner and standing around taking snuff”. Hodgson interview, 12 August 2015. ↩︎

-

11

Bob Stanley, “Hit & Myth”, The Times, 28 November 2003. ↩︎

-

12

Jo Hutton, “Derbyshire, Delia”, Grove Music Online (2008), DOI:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.2061642. ↩︎

-

13

H.J. Spencer, “Derbyshire, Delia Ann”, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2005), DOI:10.1093/ref:odnb/76027. ↩︎

- 14

-

15

Louis Niebur, Special Sound: The Creation and Legacy of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 142. ↩︎

-

16

Teresa Winter, “Delia Derbyshire Sound and Music for the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, 1962–1973” (PhD diss., University of York, 2015), 17. ↩︎

-

17

Frances Morgan, “Delian Modes: Listening for Delia Derbyshire in Histories of Electronic Dance Music”, Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture 9, no. 1 (2017), 10. ↩︎

-

18

Hodgson interview, 12 August 2015. ↩︎

-

19

Jenkins, “Delia Derbyshire, Producer of Doctor Who Theme Music, has Legacy Restored”. ↩︎

-

20

Kate Dorney and Maggie B. Gale (eds), “Vivien Leigh, Actress and Icon: Introduction”, in Kate Dorney and Maggie B. Gale (eds), Vivien Leigh: Actress and Icon (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2018), 4. ↩︎

-

21

For a more detailed discussion of the techniques employed by Derbyshire in the creation of her music, see Niebur, Special Sound; James Percival, “Delia Derbyshire’s Creative Process”. MA dissertation, University of Manchester, 2013; and Winter, “Delia Derbyshire Sound and Music for the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, 1962–1973”. ↩︎

-

22

Sonic Boom, “Delia Derbyshire Interview”. ↩︎

-

23

Anonymous, “The Electronic Music Makers”, Ariel, 21 January 1972, BBC Written Archives Centre, WAC R97/25/1, Radiophonic Workshop Scrapbooks. ↩︎

-

24

Typescript information sheet from Hornsey College of Art’s Advanced Studies Group, led by Clive Latimer and Michael Leonard, re Light/Sound Workshop techniques for moving image sequences, Delia Derbyshire Archive, John Rylands Library, DDA/1/1/6/5/9. ↩︎

-

25

Derek Lamb to Desmond Briscoe, 26 September 1966, BBC Written Archives Centre, WAC R97/29/1 Radiophonic Workshop External Correspondence. ↩︎

-

26

Michael Leonard to Desmond Briscoe, 19 May 1965, BBC Written Archives Centre, WAC R97/29/1 Radiophonic Workshop External Correspondence. ↩︎

-

27

Leonard to Briscoe, 19 May 1965. ↩︎

-

28

Delia Derbyshire to A.H.C.P. Ops, 17 August 1966, Delia Derbyshire Archive, John Rylands Library, DDA/1/1/6/5/4. ↩︎

-

29

Programme notes for Concert of Electronic Music by Unit Delta Plus at Watermill Theatre, Bagnor, 10 September 1966, Delia Derbyshire Archive, John Rylands Library, DDA/1/1/6/2. ↩︎

-

30

Brian Hodgson, email correspondence with the author, 6 April 2018. ↩︎

-

31

Hodgson email, 6 April 2018. ↩︎

-

32

Hodgson email, 6 April 2018. Hodgson recollects that: “An unlabelled tape arrived at Maida Vale for Delia from Paul [McCartney] just before the event. It was unleadered with no indication of direction of play (BBC tapes were always front out but generally commercial studios were end out) quick listen proved inconclusive and we set off for the roundhouse.” ↩︎

-

33

Clive Latimer, “K.4 Kinetic Four Dimensional”, typescript information sheet from Hornsey College of Art Advanced Studies Group, 10 November 1966, Delia Derbyshire Archive, John Rylands Library, DDA/1/1/5/12/1. ↩︎

-

34

Latimer, “K.4 Kinetic Four Dimensional”. ↩︎

-

35

Michael Leonard, letter to Delia Derbyshire, 13 December 1966, Delia Derbyshire Archive, John Rylands Library, DDA/1/1/5/12/2. ↩︎

-

36

See Anna Kontopoulou, “Young Contemporaries 1968: The Hornsey College Light/Sound Workshop”, LUX (2011), https://lux.org.uk/writing/young-contemporaries-1968-hornsey-lightsound-workshop. ↩︎

-

37

Malcolm Dickson, “Everything is Round: The Video Environments of Stansfield/Hooykaas”, in Madelon Hooykaas and Claire van Putten (eds), Revealing the Invisible: The Art of Stansfield/Hooykaas from Different Perspectives (Amsterdam: De Buitenkant, 2010),145. ↩︎

-

38

Madelon Hooykaas, interviewed by the author, 6 March 2018. ↩︎

-

39

Hooykaas interview, 6 March 2018. ↩︎

-

40

Blackburn interview, 15 March 2018. ↩︎

-

41

Madelon Hooykaas, “Chance Meeting: On my Collaboration with Elsa Stansfield”, in Madelon Hooykaas and Claire van Putten (eds), Revealing the Invisible: The Art of Stansfield/Hooykaas from Different Perspectives (Amsterdam: De Buitenkant, 2010), 37. ↩︎

-

42

Brief extracts of these two video pieces and their corresponding soundtracks by Elsa Stansfield are available at: http://www.li-ma.nl/site/catalogue/art/stansfield-hooykaas/running-time/7148; and http://www.li-ma.nl/site/catalogue/art/stansfield-hooykaas/point-in-time/2095. ↩︎

-

43

Hooykaas interview, 6 March 2018. ↩︎

-

44

Freida Abtan, “Where is She? Finding the Women in Electronic Music Culture”, Contemporary Music Review 35, no. 1 (2016): 58. ↩︎

-

45

Justin Kingsley, “Brian Eno Message—Don’t Get a Job”, Newiew Project (2016), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d-53tzx69fM. ↩︎

-

46

Janneke Wesseling, “Re:vision: The Experience of Nature, Time and the Unforeseen”, in Madelon Hooykaas and Claire van Putten (eds), Revealing the Invisible: The Art of Stansfield/Hooykaas from Different Perspectives (Amsterdam: De Buitenkant, 2010), 105. ↩︎

-

47

Sarah Reeve, “Li Yuan-chia’s Art Retrospective Comes to London”, Asia Times (2016), http://www.atimes.com/li-yuan-chia-retrospective-comes-london/. ↩︎

-

48

Guy Brett, “Space–Life–Time”, in Guy Brett and Nick Sawyer (eds), Li Yuan-chia: Tell Me What is Not Said Yet (London: Institute of International Visual Arts, 2000), 11. ↩︎

-

49

The exact nature of Derbyshire’s relationship with Li is unclear. Andy Christian’s autobiographical account of his visits to the LYC in the 1970s states that “a relationship began” when Derbyshire moved in with Li in 1976 but other friends of the two, such as Joy Dee, have stated that although Li might have wanted a romantic relationship with Derbyshire, no such relationship developed. See Andy Christian, In The North Wind’s Breath (The Private Press at Penny Royal, 2018), 22; Joy Dee, interview with the author, 6 March 2019. ↩︎

-

50

Paul Overy, “Museum on Hadrian’s Wall”, in Guy Brett and Nick Sawyer (eds), Li Yuan-chia: Tell Me What is Not Said Yet (London: Institute of International Visual Arts, 2000), 131. ↩︎

-

51

Blackburn interview, 15 March 2018. ↩︎

-

52

Brett, “Space–Life–Time”, 49. ↩︎

-

53

Blackburn interview, 15 March 2018. ↩︎

-

54

Brett, “Space–Life–Time”, 43. ↩︎

-

55

Brian Hodgson, “Delia Derbyshire: Pioneer of Electronic Music who Produced the Distinctive Sound of Dr Who”, The Guardian, 7 July 2001. ↩︎

-

56

One of the most affecting insights into Derbyshire’s time in Cumbria is provided by the sound artist and oral historian Jenn Mattinson in her 2017 piece Out of Place, which was commissioned for the Delia Derbyshire Day events in 2017, marking what would have been Derbyshire’s eightieth birthday. The piece makes use of interviews with two of Derbyshire’s friends who knew her in Cumbria, Cath Foxton and Joy Dee, the latter taking over from Derbyshire as Li Yuan-chia’s assistant at the LYC Museum & Art Gallery. The full piece can be heard on SoundCloud at https://soundcloud.com/user-788026861/out-of-place-delia-derbyshire-in-cumbria. ↩︎

-

57

Delia Derbyshire to Desmond Briscoe, Undated 1977, BBC Written Archives Centre, BBC WAC R97/25/2 Radiophonic Workshop Scrapbooks. ↩︎

-

58

Hodgson, “Delia Derbyshire”. ↩︎

-

59

Elisabeth Kozmian, email correspondence with the author, 22 October 2015. ↩︎

-

60

Elisabeth Kozmian, email correspondence with the author, 4 September 2013. ↩︎

-

61

Kozmian email, 22 October 2015. ↩︎

-

62

Elisabeth Kozmian, email correspondence with the author, 11 April 2016. ↩︎

-

63

Blackburn interview, 15 March 2018. ↩︎

-

64

Blackburn interview, 15 March 2018. ↩︎

-

65

Morgan, “Delian Modes”, 22–23. ↩︎

-

66

Frances Morgan, “Pioneer Spirits: New Media Representations of Women in Electronic Music History”, Organised Sound 22, no. 2 (2017): 240. ↩︎

Bibliography

Abtan, Freida (2016) “Where Is She? Finding the Women in Electronic Music Culture”. Contemporary Music Review 35, no. 1: 53–60.

Anonymous (n.d.) Typescript information sheet from Hornsey College of Art’s Advanced Studies Group Information Sheet No. 10. Delia Derbyshire Archive, John Rylands Library, DDA/1/1/6/5/9.

Anonymous (1966) Concert of Electronic Music by Unit Delta Plus, programme notes. Watermill Theatre, Bagnor, 10 September. Delia Derbyshire Archive, John Rylands Library, DDA/1/1/6/2.

Anonymous (1972) “The Electronic Music Makers”. Ariel, 21 January. BBC Written Archives Centre, WAC R97/25/1 Radiophonic Workshop Scrapbooks.

Blackburn, Clive (2018) Interview with the author, 15 March.

Brett, Guy (2000) “Space–Life–Time”. In Guy Brett and Nick Sawyer (eds), Li Yuan-chia: Tell Me What is Not Said Yet. London: Institute of International Visual Arts, 10–105.

Cavanagh, John (1998) “Delia Derbyshire: On Our Wavelength”. Boazine 7. http://www.delia-derbyshire.org/interview_boa.php.

Christian, Andy (2018) In The North Wind’s Breath. The Private Press at Penny Royal.

Dee, Joy (2019) Interview with the author, 6 March.

Derbyshire, Delia (1966) Memo to A.H.C.P. Ops, 17 August, Delia Derbyshire Archive, John Rylands Library, DDA/1/1/6/5/4.

Derbyshire, Delia (1977) Letter to Desmond Briscoe. BBC Written Archives Centre, BBC WAC R97/25/2 Radiophonic Workshop Scrapbooks.

Dickson, Malcolm (2010) “Everything is Round: The Video Environments of Stansfield/Hooykaas”. In Madelon Hooykaas and Claire van Putten (eds), Revealing the Invisible: The Art of Stansfield/Hooykaas from Different Perspectives. Amsterdam: De Buitenkant, 145–156.

Dorney, Kate and Gale, Maggie B. (eds) (2018) “Vivien Leigh, Actress and Icon: Introduction”. In Vivien Leigh: Actress and Icon. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Hodgson, Brian (2001) “Delia Derbyshire: Pioneer of Electronic Music who Produced the Distinctive Sound of Dr Who”. The Guardian, 7 July.

Hodgson, Brian (2015) Interview with the author, 12 August.

Hodgson, Brian (2018) Email correspondence with the author, 6 April.

Hooykaas, Madelon (2010) “Chance Meeting: On my Collaboration with Elsa Stansfield”. In Madelon Hooykaas and Claire van Putten (eds), Revealing the Invisible: The Art of Stansfield/Hooykaas from Different Perspectives. Amsterdam: De Buitenkant, 33–66.

Hooykaas, Madelon (2018) Interview with the author, 6 March.

Hutton, Jo (2008) “Derbyshire, Delia”. Grove Music Online. DOI:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.2061642.

Jenkins, Russell (2008) “Delia Derbyshire, Producer of Doctor Who Theme Music, has Legacy Restored”. The Times, 18 July.

Kingsley, Justin (2016) “Brian Eno Message—Don’t Get a Job”. Newiew Project. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d-53tzx69fM.

Kontopoulou, Anna (2011) “Young Contemporaries 1968: The Hornsey College Light/Sound Workshop”. LUX. https://lux.org.uk/writing/young-contemporaries-1968-hornsey-lightsound-workshop.

Kozmian, Elisabeth (2013) Email correspondence with the author, 4 September.

Kozmian, Elisabeth (2015) Email correspondence with the author, 22 October.

Kozmian, Elisabeth (2016) Email correspondence with the author, 11 April.

Lamb, Derek (1966) Letter to Desmond Briscoe, 26 September. BBC Written Archives Centre, WAC R97/29/1 Radiophonic Workshop External Correspondence.