Instant Malaysia

I: Personal Journey

Meandering through the Malaysian exhibition in the

Commonwealth Institute, this text takes

the form of

ghost-writing: a

segue of

continuous texts,

subjecting the self

to ambulation

through space and

time.

Ghosting.

I am going to visit Malaysia. A Malaysia I have never visited. An alternate Malaysia

I have not seen as a citizen of the country.

It is exciting;

and a different experience.

Will I recognise the place, be familiar with the culture, people, or climate?

After all, this is not Malaysia geopolitically located in Southeast Asia,

but a Malaysia created by an exhibition promoting the country of my birth. Promoting Malaysia at the centre of the old empire: the Commonwealth Institute

for London audiences.

I will be comparing the Malaysia I know as a lived experience against what I see at the display—walking through the exhibition space to get to know the place I think I know. A country condensed and housed in an exhibition gallery, confined within fabricated walls.

Maybe, this will be my way of looking at what it means to be Malaysian; facing my

struggles and coming to terms with the country’s history, nationalism, patriotism, and understanding the nation-state

in another place: in London.

It is 2019, 36 years after the Instant Malaysia exhibition was staged. Though it was

intended to be a permanent display, technological failures mean that it did not survive until the closure of the Commonwealth Institute in 2002.

I don’t know for sure.

Today, the Institute has ceased to exist, its building redeveloped into the new and gleaming Design Museum.

When I visited the Design Museum,

I was not there for their exhibitions. Sorry.

Instead, I was constructing my memory theatre, removing the exuviae of the new institution

to visualise the old.

At the Design Museum’s reception, I paid £2 for a short history of

the building.

I asked for the Commonwealth Institute’s library and archives. They are scattered

everywhere, they told me. Its traces almost completely

erased, forgotten, or disconnected

from its replacement.

Nevertheless, it was in 1973 when the Malaysian display

graced the halls of the Commonwealth Institute. It was practically unknown to Malaysians

then and now. I would not have known about this show, if not for my years of residing

and studying in London.

How do I visit an exhibition that lives in the past?

Loosely taking a page from Walter Benjamin’s The Arcades Project,

I like the possibility of visiting the display as a

displaced character and having fragments of information

fill the gaps.

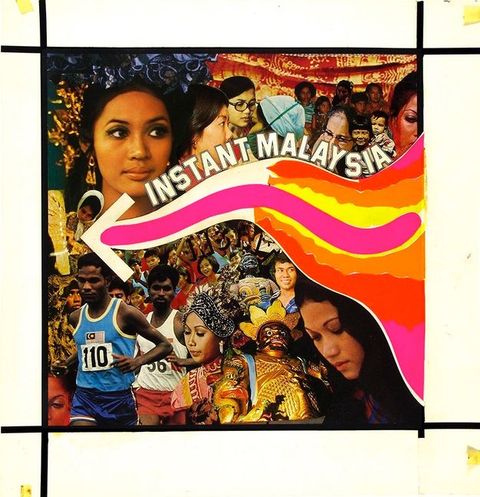

Coming to the entrance of the display, I am looking at

exhibits of black and white faces plastered onto boards

of red and green.

The aesthetic sensibilities of the boards are possibly the flavour of the day,

but it’s too gaudy for my taste.

Furthermore, the images are cropped and enmeshed together in jarring compositions.

Maybe I missed it, but they lack explanatory notes to elaborate on their intentions.

Nevertheless, the boards are probably the work of

Ron Herron, an English architect, who had an affinity for pictorial collocation

—juxtaposing portraits of people.1

On the panels are photos of Malaysians, people from all walks of life—entangled.

This style of portrayal continued on the walls of the exhibition.

On the front left panel by the entrance, the word Malaysia attempts to encapsulate the people

of a nation.

Conceivably, the non-coloured images reflected a unity among

the races, or attempted to blanket over differences.

My walk-through reveals that the display

was constructed to represent a country in a particular period.

To re-enact a Malaysia from a different era: the time my parents’ generation reminisced as the

“good old days”.

Yesterday’s exhibition.

1Simon Sadler, Archigram: Architecture Without Architecture (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2005), 54.

II: Malaysia and the “Soft Sell”

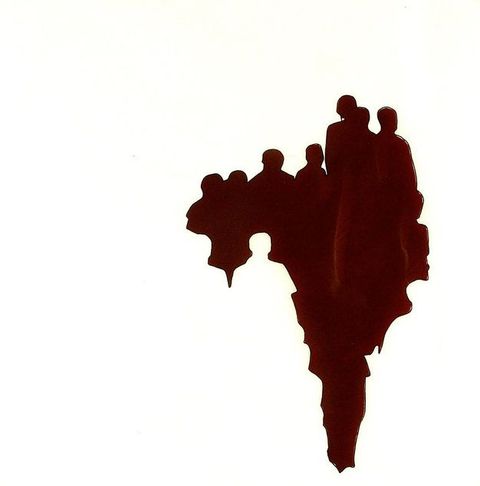

13 May 1969

and a personal reflection

Malayan Independence in 1957

framed diverse people as countrymen within an imagined

community,2

formulated by the borders that make a nation. Alongside

the Malay majority, there were

Chinese and Indian immigrants, whose forefathers came to

British Malaya for work

and trade.

Malayan Independence gave them a chance to be part of a new country, but racial seams remained, and ethnic issues became domestic points of contention. National boundaries separated Malaysia from Singapore in the South of the Peninsula in 1965, just as societies in the North were divided from Thailand.

The borders separated

families, friends, and cultures.

In 1969, Malaysia’s first general election after Singapore’s departure sparked a national implosion. For voters who lost in the election, discontentment with—among the reasons given—overzealous celebrations, and racial and religious taunting by supporters of the winning party, led to confrontations and violence. The Chinese and Malays began rioting on 13 May, as increasing instability and deaths on the streets prompted the government to impose a curfew. Parliament was suspended in a state of emergency and a National Operations Council (NOC) was established to manage state affairs for the next 18 months, until Parliament was reinstated in 1971. Led by the NOC, the Department of National Unity created the National Principles to unify the country, and spent “nearly a year drafting a national ideology meant to bond Malaysia’s diverse population.”3 The principles were based on the Malaysian Constitution and could not be challenged; it has been argued that they “considerably tightened the political framework in Malaysia and restricted the freedom of expression and manoeuvre of the opposition parties.”4

My parents had grown up in different towns accustomed to a British lifestyle and practices. Their youth was the subject of some of my bedtime stories, but these stories disappeared or became darker when they thought of the 1970s. The racial riots after the '69 elections changed the country, they said.

I remember this particular anecdote:

On 13 May, a curfew was announced asking everyone to vacate the streets. With shops closing indefinitely, your grandmother went out alone. Desperate, she cycled for miles to buy milk powder for her infant. We thought she would die.

a story in a car ride, 1988

2Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities, revised edn (London: Verso, 2006).

Perdana Leadership Foundation, “Rukun Negara: The National Principles of Malaysia”, 19 September 2016, http://www.perdana.org.my/index.php/spotlight2/item/rukun-negara-the-national-principle-of-malaysia. Accessed 25 January 2019.

Peter Wicks, “The New Realism: Malaysia since 13 May, 1969”, The Australian Quarterly 43, no. 4 (December 1971): 20–21, http://www.jstor.org/stable/20634465. Accessed 12 May, 2019.

The Malaysian exhibition, a few years later.

A little-known fact:

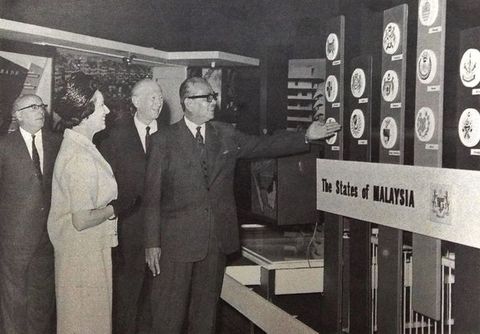

Instant Malaysia was a production headed by the Malaysian government. Various

government bodies were enlisted, including

the Visual Production team from

the Ministry of Information,

the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and

the Malaysia High Commission of London.

When the exhibition began its run at the Commonwealth Institute, it showcased significant and noteworthy technological advances in exhibition design. State of the art mechanisms, automatic sensors, and a climate simulator were fabricated to enhance the experience.

Malaysia’s humid climate was artificially fabricated to provide an immersive experience. Visuals, sound, heat, and touch transported visitors to the tropical surroundings of Malaysia. The Malaysia Department of Information also produced a brochure for members of the audience, serving as a souvenir and guide.5 Regrettably, I can’t find a copy of the brochure. The exhibition was funded by the Government, and must have been especially costly during its recovery from the national crisis, though it appears this was downplayed.

An initial plan for the exhibition, designed by James Gardner, was rejected by the government. A different approach was necessary to: …reinvent the nation’s image for larger global communities especially after the 1969 riots; and to remain economically competitive at the onset of the worldwide oil crisis in 1972.6 The Malaysian government took ownership of its national exhibition, as the Commonwealth Institute’s curatorial leadership was set aside.

5Commonwealth Institute, Annual Report of the Director to the Board of Governors (London: Commonwealth Institute, 1973), 8 and 12–13.

Chee-Kien Lai, “Concrete/Concentric Nationalism: The Architecture of Independence in Malaysia, 1945–1969”, PhD dissertation, University of California, Berkeley, 334.

Architect and historian Lai Chee-Kien writes:* *

To procure a suitable design for a new exhibit, the Malaysian government in 1972 approached the architects of Archigram through Fred Lightfoot, an administrator at the Institute. A meeting was convened where a Malaysian representative presented what was programmed, and how they could be exhibited in the new display. Archigram accepted the job as the nature of the task was similar to earlier projects … The exhibit’s conception and design were largely undertaken by Dennis Crompton and Ron Herron…7

Following the exhibition, Archigram reported:

7Archigram Architects recently designed a permanent exhibition at the Commonwealth Institute for the Malaysian government which has set out to soft sell the country as a politically viable, economically stable and industrially progressive nation. At the opening of the exhibition, at the end of last year, the High Commissioner said the exhibition was intended to “show a cross-section of life in Malaysia today … and its hopes and aspirations for the future” as an integrated multi-racial country. With the aid of the audio-visual techniques used in the exhibition, plus “the blessing of the Almighty” (to quote the High Commissioner again), the soft sell is pretty successful—at least in its hardware; which stands out resoundingly from the conventionally tasteful exhibits which surround it.8

Lai, “Concrete/Concentric Nationalism”, 334–335.

Architectural Design, “Archigram as Architects”, Architectural Design (1974): 387–388. Project by Centre for Experimental Practice, “Malaysian Exhibition”, Archigram Archival Project (2010), University of Westminster, http://archigram.westminster.ac.uk/project.php?id=171. Accessed 10 January 2018.

The engagement between the parties was made through Commonwealth links. The result was a Malaysian themed exhibition interpolated by the changing forms and architectural designs of Archigram’s practice. The group’s ideological emphasis on “hardware”, rather than politics, would have been favourable to the Malaysian selection committee, whoever they were. Staging the show at the Commonwealth Institute, where Malaysian exhibitions were already on display in the permanent galleries, was a platform to strengthen existing relationships, participate in an international forum, and “soft sell” the nation to other Commonwealth citizens and businesses.

***

So,

the images from Instant Malaysia used diversity and pluralism to entice visitors, a message spearheaded by the government to denote a harmonious society.

Back in Malaysia, official forms for locals still have a

tick box

for ethnic divisions.

What happened to the Commonwealth’s objective of racial equality?

Instead of addressing the blood-stained streets and social re-engineering

policies, Instant Malaysia was a smokescreen concealing actual realities.

Was this a political project with a state agenda? Governmental policing by exhibition?

The Malaysian racial riots happened four years before

the installation of Instant Malaysia. It was probably an event

unknown to many in London.

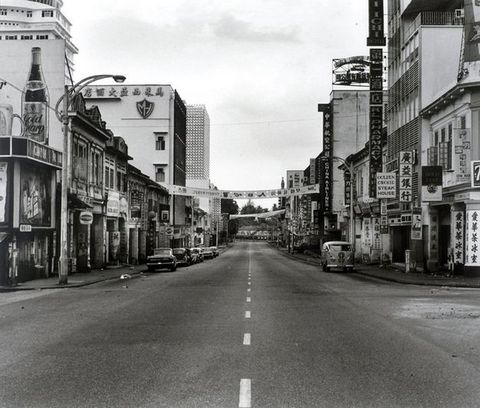

As I continue with my walk, there is a sense that this is primarily a

Malaysia packaged and sold to the world when long-distance travel

was less accessible in the 1970s.

Unless someone had the financial means or cause

to take such an incredibly long flight, folks

were unable to experience the tropical country in the East.

This exhibition provided an experience of the tropics,

transporting visitors like myself to another world,

another place instantly.

Who were the people who formed the audience?

From my perspective, foreigners are looking at Malaysians in the photomontage.

What would they make of the images? Would they think critically about the exhibits?

I hope visitors considered the scope and meaning it created as a national exhibition, but also

wonder if other nationally endorsed shows were curated and presented in this manner and scale?

Something worth considering.

III: Archigram

What is Archigram?

\

I read:

Archigram are amongst the most seminal, iconoclastic and influential architectural groups of the modern age. They created some of the 20th century’s most iconic images and projects, rethought the relationship of technology, society and architecture, predicted and envisioned the information revolution decades before it came to pass, and reinvented a whole mode of architectural education—and therefore produced a seam of architectural thought with truly global impact.9

The collective efforts of the architects produced over 900 drawings between 1961 and 1974. Mike Webb, a founding member of the group, explained that the drawings were not just two-dimensional works. They embodied and expressed ideas.10 To understand Archigram would be to examine their drawings.

9Project by Centre for Experimental Practice, “About Archigram”, The Archigram Archival Project, 2010, University of Westminster, http://archigram.westminster.ac.uk/about.php?pg=archi. Accessed 10 January 2018.

Peter Cook, ed. *Archigram *(New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1999), 2–3.

It was through Archigram’s drawings that I managed to make more cohesive sense of Instant Malaysia.

There is a sense

that Archigram’s research may not be entirely visible, as

much of it became incorporated into the exhibition.

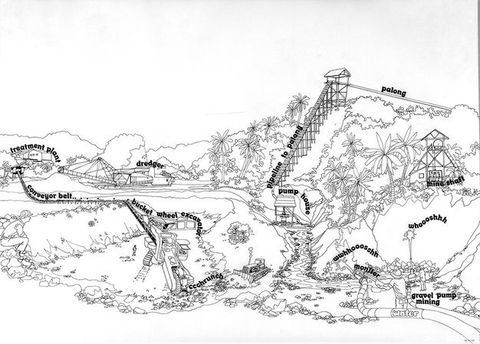

Dennis Crompton, another founding member of Archigram, spoke in an interview about his ten-day research trip to Malaysia. Upon arrival at the airport, he encountered a wave of hot and humid air, which was a new experience for him.11 He

travelled around the peninsula and visited its major cities and industries; and experienced its various landscapes, cultures and micro-climates.12

Crompton visited Malaysia to study and observe everything the country had to offer. His research was fairly extensive:

there are mapped towns and careful annotations of significant sites relating to infrastructure, education, and tourism. Studies included:

topographical layouts, and images of Malaysian domestic aviation, riverine routes, railway lines, road systems, areas with tin mining and timber, rubber plantations, and worldwide telecommunications for the country.

Some of these were charted on local and global maps to pinpoint exact locations.

11Lai, “Concrete/Concentric Nationalism”, 252 and 335.

Lai, “Concrete/Concentric Nationalism”, 335.

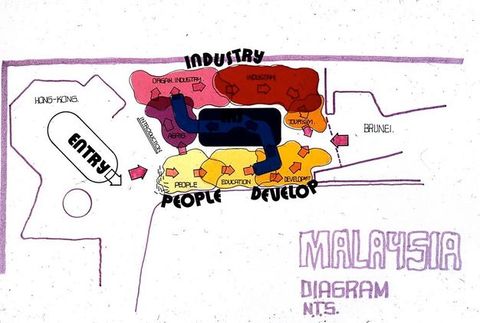

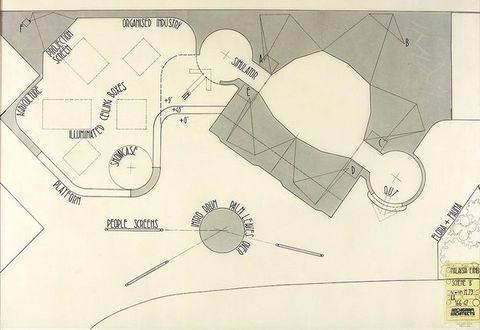

These drawings made little sense until I realised they were studies for different sections of the exhibition. Reading the drawings in parallel with installation photographs uncovered Archigram’s intention to delineate the different sectors, including

organised industry, agriculture, education, tourism, and development, with

subsections on

communications, housing, health and welfare, policy, and planning.

The Archigram designers wanted to demonstrate the nation’s progressive politics and industries; that even a third world country was a place of tremendous prospects. Without government support for their research, gaining access to all this information would have been impossible.

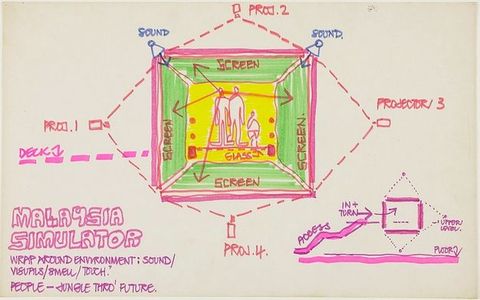

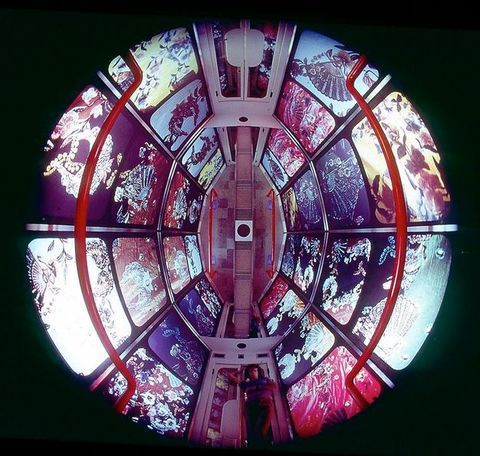

Archigram research outcomes populated the lower level display, which provided a comprehensive account of Malaysia as a nation, while the upper level contained the sensory simulator.

Even though the Archigram graphics were vibrant, within

the exhibition I found many photos

in black and white,

dulling the colours of the country.

Beautiful drawings, possibly meant for large-scale wall and pillar illustrations, were also replaced in several instances by photographic images in the display. Their omission remains one of the mysteries of the exhibition.

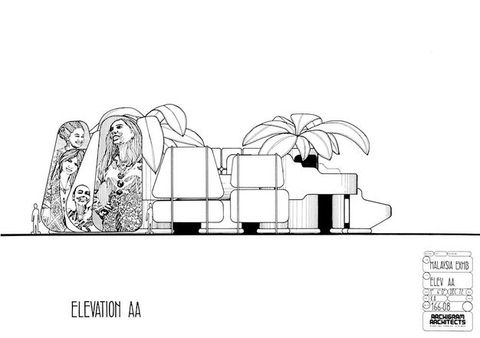

In the Elevation A–A drawing, a human figure on the left specified the structure’s massive proportions. It was also a prompt to read the illustration from left to right—in accordance with how visitors would stream across the display. The architects added a tropical feel to the design with two overarching palm trees looming over the show. It is evocative of certain old Malaysian Tourism Board advertisements promoting sunny beaches with trees that give shade from the tropical heat.

In my opinion, there are strong parallels with the tourist experience; front panels resembled locals greeting visitors arriving upon Malaysian shores. Moving deeper into the interior metaphorically opened up the country, providing access to its ecosystems, culture, and industrial sectors. The entire configuration was carefully considered, encouraging viewers to explore the varied industries and people’s lives from within the structure, which also symbolised the country.

The drawings also provided insight into the incorporation of vernacular architecture in the show.

Malay houses are traditional architectural forms suited for the tropical weather. These timber structures built on stilts with a slanting roof offered sufficient ventilation and protection against natural elements.

I find the shape of the slanted roof similar to the kit-of-parts that Archigram used in the exhibition. The proposed exhibition structures—

recreations to be installed as part of the displays—are possibly simplifications of the original. But the scale of the standing figure in the exhibition drawing is comparable to the proportion of a person’s height in an actual Malay House.

Importantly, adopting traditional architectural values

enhances the showcase

by retaining the essence of

Malaysian culture in this

exhibition for those unfamiliar with

Malaysia.

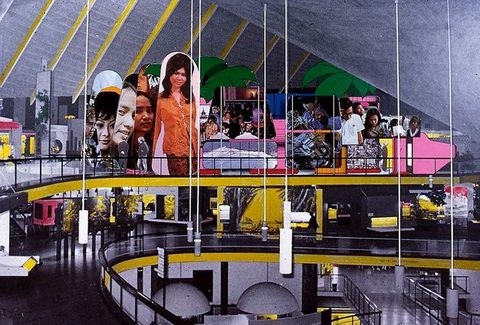

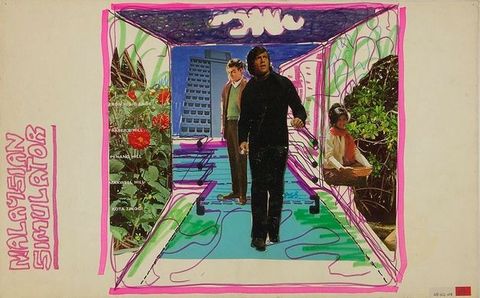

Ron Herron’s axonometric print of the exhibition featured a bird’s-eye view of the entire

arrangement in colour, compared to the earlier outline drawings.

The different sections were fully illustrated

—children in school uniform would be in the education section, and so on.

The only solid-looking structure appeared to be the simulator hovering in the

centre, with the surrounding exhibits looking more

malleable and organic.

Baillie, my editor, wondered if perhaps the exhibits surrounding the solid central structure were modular; another kit-of-parts assembled to mould the space, guiding visitors through stand-alone thematic displays that could be presented together variously.

This approach would be a nod to Archigram’s

propositions of non-solid architecture.

Since the 1960s, the architects in the group have challenged accepted conventions

with futuristic strategies and outcomes.

Instant Malaysia’s set-up was well suited to their architectural ideas,

which went beyond the

modernistic conventions of the day.

Fortunately, there is an illustration which allows for a comparison of Archigram’s vision

against the realized project. The collage was fairly colourful and brighter in contrast to the muted outcome of the show, with greyscale images fronting the exhibition façade. A green coloured structure was chosen to envelop the exhibition, and the portrait boards were scaled down making them less imposing. Moreover, the portraits were considerably smaller and now bled around the edges of the construction. Strikingly, the palm trees no longer reach above the top of the showcase. The exhibition photograph provides a good idea of the space taken by Instant Malaysia within the Commonwealth Institute, revealing that, compared to other exhibits at the time, it was a bigger attraction.

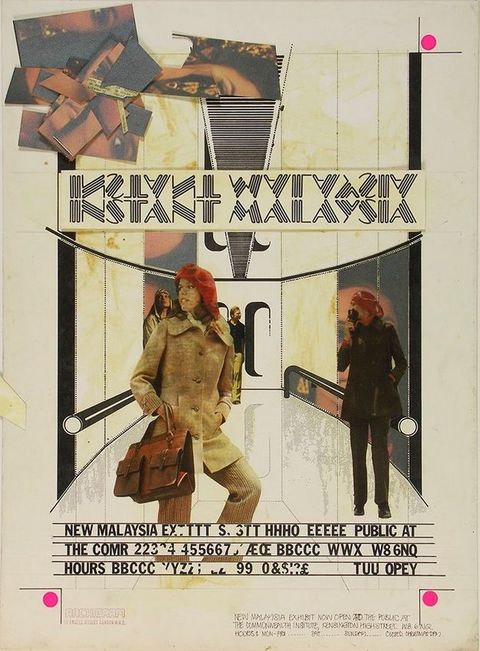

I found a couple of graphics in the Archigram Archive.

With no written evidence, I can only speculate on their intended purposes. The way they foreground the exhibition title suggests advertisements to entice London viewers to the exhibition. Herron and Crompton’s graphic arrangement of Malaysians meshed together interestingly inserted a gold-plated statue of a deity among ordinary faces. In a different pitch, Herron and Allinson’s design-in-progress had white visitors within the simulator. The use of plausibly European models probably had a greater chance of attracting British visitors to the exhibition. At this stage of the planning, the simulator’s design was already complete, with handrails on the side mounted in front of the large projection screens. Unfortunately, I am not doing justice to the design properties employed in the posters.

A design historian would surely be able to articulate the principles of design seen here, and the currency of graphic design in the 1970s, but I am searching for clues that illuminate the experience of the exhibition.

Archigram adopted a multitude of influences including technology, space gadgets, media, and even pop culture. Their endeavours were not unnoticed by the Malaysian Government, who engaged their services and allowed Archigram’s unconventional approaches to infuse their permanent exhibition.

This is how Archigram described the simulator for Instant Malaysia:

13The major feature of the exhibition, which is built on two levels, is the sensory (and sensual) simulator located at the level above the general display area. Inside, “in 12 minutes you experience the 90º atmosphere of the Malay jungle and the cool winds after the monsoon”. The simulator accommodates up to 15 people at any one time and they are subjected to constantly changing visual images and sounds, and, more powerfully, temperature and humidity. The mechanics of the simulator are interesting—the four screen multi-projection slide system, which is literally done by mirrors, synchronised with three track sound, and the associated impacts of superimposition, dissolve, blink etc… In the end, of course, it is the simulator which really draws one’s attention. Rightly or wrongly, this particular piece of hardware is much more intriguing than the content of the exhibition as a whole.13

Centre for Experimental Practice, “About Archigram”, The Archigram Archival Project.

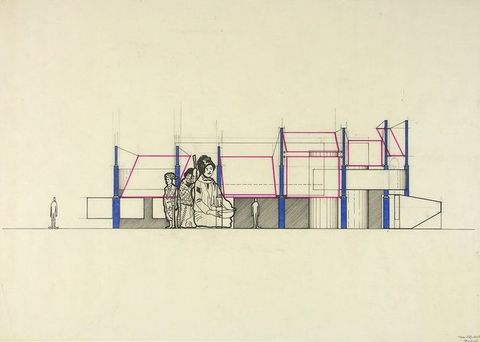

Coloured

illustrations also provided insights to the

simulator.

Though the end product evolved from these

initial ideas,

it was a window into the conceptual developments for the main exhibit.

With a limited number of photographs

of the actual simulator,

graphics and sketches signified the

designers’ intent to

encapsulate viewers with

foliage and nature.

Different images projected on the screens

also

made an impression

of this being a one-stop visit, bringing

multiple attractions

from Malaysia together for

visitors’ convenience.

Instant.

The idea of a living machine was carried over to Instant Malaysia from earlier Archigram conceptions, with the simulator having one objective: to induce a tropical ecosystem similar to Malaysia.

Archigram projects adopted the kit-of-parts as their architectural language. These flexible assemblages allowed the architects to work with organic components instead of fixed structures. This significant shift moulded their direction as appliances became increasingly visible in their ideations. Here are some of the items they used:

… First, the idea of a “soft-scene monitor”—a combination of teaching-machine, audio-visual juke box, environmental simulator, and from a theoretical point of view, a realization of the “Hardware/Software” debate … as the notion of an electronically-aided responsive environment…14

Due to the close time-frame between the projects and Instant Malaysia, it is not a surprise

to see Archigram use similar machines/ideations adopted from earlier projects.

I believe all their projects and developments added to the knowledge that made *Instant Malaysia *possible. The drawings and photographs for Instant Malaysia evidenced Archigram principles as

I think of the Malaysian exhibition as a materialisation and achievement of the group’s

incredible journey.

Built for London audiences,

the simulator’s objective was to clone a particular human condition:

of people acclimatised and habituated in hot, humid conditions with torrential monsoon rain. In short, the tropical weather. The simulator’s function enabled visitors to experience this alien condition.

14Cook, Archigram, 94.

According to the 1974 Commonwealth Institute Annual Report, the Malaysian simulator was

popular with visitors. In the following years, there

were continuous reports of damages, theft, and vandalism

of the exhibit. The dysfunctional machine persisted as

the Commonwealth Institute laboured to keep the device

fully operational. The Commonwealth’s 1977’s Annual

Report concluded that the complex system needed

continuous maintenance, which generated a substantial

financial cost.15

By this time, thieves had stolen the slides from the old

machine, which was in need of an overhaul. With the

consistent technical problems plaguing the device, the

Instant Malaysia simulator is an exemplar of an

exhibition over-reliant on an instrument.

Who should have taken responsibility for the simulator? The Malaysian Government, or Archigram?

Unfortunately, the company that had produced the simulator for Archigram ceased its operations in 1975. Without the simulator, visitors and the exhibition itself were victims of a failed machine.

15Commonwealth Institute, Annual Report of the Director to the Board of Governors (London: Commonwealth Institute, 1974), 15; Commonwealth Institute, Annual Report of the Director to the Board of Governors (London: Commonwealth Institute, 1975),18; Commonwealth Institute, Annual Report of the Director to the Board of Governors (London: Commonwealth Institute, 1976), 17; and Commonwealth Institute, Annual Report of the Director to the Board of Governors (London: Commonwealth Institute, 1977), 16.

I spoke to a Malaysian who visited the exhibition in

1973, and

she said,

The graphics were excellent, and the display had a presence and scale unlike some lurid images

now. I remember the humidity simulator very well. I was impressed when I saw it as anything Malaysian was usually less exciting. People wished to experience the tropics again. While Malaysian visitors wanted to feel the warmth, the British officers who travelled to Malaysia before this exhibition were nostalgic of their time spent in the tropics. Although I did not see them at the show, I met some of them afterwards, friends of my parents.

The simulator was humid. When you arrive at Kuala Lumpur International Airport

after a long flight and come out into the open? That blast of humid hot air. Like that. Also, it smelled right in the capsule. Like, after rain. There was no time limit as we took our time. Also, it was quite spacious. I do not remember feeling crowded-in.

*From the screens, I saw images of tropical plants and wild animals. Yes, monkeys and *

a tiger. The sounds were terrific with a waterfall somewhere.

*It became one of those must-see exhibits that year. I was there a few times with my friends. *

I think Londoners, especially those who have not visited Malaysia would have liked it—to experience tropical humidity at their doorstep. Those I met at the exhibition were pleasantly surprised by the different climate and thoroughly enjoyed it.16

16Born and raised in Malaysia, Izan Tahir received her education at the London College of Printing in the 1960s. She was a designer employed by Terence Conran when she visited Instant Malaysia in 1973. Izan witnessed the political and cultural developments in the UK and experienced the tumultuous formation of Malaysia as a new nation-state. I had this conversation with Izan on 4 December 2017.

The visitor enjoyed the simulator, and recalled certain vivid sights, sounds, and feelings such as the controlled

temperature, decades after the event. That the show was a talking point among former British colonial officers and Malaysians in the 1970s proves the success of the simulation. I argue that the exhibition and simulator inadvertently became their memory theatre of time spent in Malaysia. Archigram probably did not intend the display to have nostalgic purposes. Nevertheless, it went beyond its objective as a real crowd-pleaser, triggering deeper feelings and emotions from people affiliated with Malaysia.

***

Earlier, I mentioned Crompton’s visit to Malaysia. In the simulator, he must have incorporated the sensation of the tropical weather that he experienced with the more general atmosphere of a jungle. The visitor was right when she recalled the sounds of wild animals.

Up until the 1990s, I had older Europeans asking if I lived on top of a tree. One wonders if there was a link between the Malaysian exhibition and the lasting perceptions it formed for its visitors.

So, these are the things one experienced in the simulator.

I saw it as an

interactive simulator

political simulator

education simulator

humidity simulator

memory simulator

It was a form of entertainment, an attraction for visitors to Instant Malaysia and the

Commonwealth Institute in 1973; and in 2019—for me.

It was fantastic listening to the memories of somebody who had visited the exhibition.

Her account alongside with Archigram’s notes added a human touch to my mental image of the display.

I would love to speak with British visitors who visited Instant Malaysia.

That would be a third perspective, showing how they perceived the exhibition as the target audience.

I am still amazed by this exhibition.

Doesn’t it mean one country in two locations?

A strange proposition,

Malaysia in Southeast Asia and Malaysia in London.

I’m a town boy.

Growing up in the 1980s and 1990s, I experienced most of

the things shown in the simulator, except for the wild

animals incorporated into the sequence—something I hope

to see only at the zoo. However, the simulation of rain

was spot-on.

That tropical smell was unmistakable and the sounds,

magical.

The filmed scenes are images I associate with Malaysia,

but it is weird to see them portrayed on the screens. I

probably took such things for granted.

My walk-through of the exhibition was probably unnecessary and inappropriate. After all,

I was not the exhibition’s target audience. It was for

non-Malaysians to get to know the new country, and there

was a sense of exoticisation at play; to romanticise the

foreign culture and differentiate it from British

practices and experiences.

However, the exhibition was a portrayal of Malaysia in

1973.

It introduced the Malaysia I know, but different. I am told the country was much greener then, with less cars, less pollution, less sophisticated electronic devices. A simpler life. Growing up, I did not have the luxury of the Internet until my college days in the 1990s.

It was a different world with different conditions

then.

With advancements in global travel today, people are

probably less taken with the images from

Instant Malaysia. However, it is a nostalgic

trip for me. A trip down memory lane—remembering the

conditions and beauty of Malaysia.

If I had been the curator of this significant exhibition, forgotten though it is today, what would I have wanted the audience to see? How would I frame the visual

pedagogy of such a show? The Commonwealth Institute posited exhibitions like Instant Malaysia as educational tools. Their efforts, documented in photographic prints, depict schoolchildren visiting the shows. I wonder about the impact of such visits and how they shaped young minds towards the Commonwealth’s objectives? The Commonwealth’s educational drive has been in place for decades, instructing thousands of people. How did it affect, change, or develop new windows into third world countries, like Malaysia, which exhibited at the Commonwealth Institute? These exhibitions were knowledge agencies containing the power to frame viewer perceptions. Didactic in nature, they were capable of building serious scholarship on these alien cultures by percolating their social, cultural, political, and ethnographical practices.

I still have a question. Should the presentation be considered a Malaysian exhibition, or should it be viewed as an Archigram display? It was a Malaysian display with Archigram aesthetics, where one could not do without the other.

The fulfilment of the project was never an intervention for the architects. Archigram’s design

and execution of Instant Malaysia was never celebrated as an achievement of the group. Until today, even Archigram publications have very little information regarding the Malaysian show.

It resulted in

the exhibition itself forgotten as there are a lack of dedicated resources regarding Instant Malaysia. As a Malaysian and a student of the history of art, I have never even heard of this national presentation. I started my investigation with a scrap of information on a website which has since been taken down, highlighting this Malaysian exhibition at the Commonwealth Institute. Further research on unpublished Commonwealth documents brought me to archives of universities and museums focused on art exhibitions, but not the “national galleries” in the Commonwealth Institute. This is surprising as the national spaces were spread across the main areas of the building. It then dawned on me that shows like Instant Malaysia were significant in forwarding new nation states with the support of the Commonwealth of Nations, not fine art. These national exhibitions became a political front, a façade of newly independent countries promoting themselves to the world in London. In turn, fine art was shown in the art gallery, but it was not displayed within the spaces allocated for national agendas and portrayals. The 1973 Malaysian exhibition was a means to “soft sell” a modernising and developing country. With the entire country’s ecosystem acting as subject matter, it took precedence over artistic practices and presentations. Lest we forget, the Commonwealth Institute was an organ of the Commonwealth, a political association.

Essentially, months of investigation finally revealed the Archigram digital archives with

drawings, photos and prints of the Malaysian show. Even then, there were minimal written resources as I continue my journey piecing together information using predominantly Archigram images.

One more thing about architects and their design for exhibitions.

I read:

Much has been written about how challenging architecture exhibitions are to mount. The primary critique is that they rely on displaying representations—drawings, sketches, collages, models, fragments, photographs, the like—rather than built forms. But these documents are, for many practitioners, their principal form of communicating architectural ideas…17

For architects, this is the way they present their works in and through exhibitions. Without permanent structures, these works on paper, print, and models become the completed works. Archigram embraced this method of production and presentation—providing many of these valuable works for the Malaysian exhibition. The annual reports from the Institute in the 1970s also left behind links. Without Archigram and the annual reports, it would have been impossible to historicise the Malaysian exhibition and its significance.

Where Malaysia is concerned, this exhibition provided a glimpse of how the government wished to promote the country, especially towards London and European audiences. The state commissioned Archigram, a London-based practice for the construction of a simulated display within a strategic London space, the Commonwealth Institute. It resulted in a co-authorship consisting of Malaysian advocacies, political direction, and subject matter combined with the architects’ technological experimentations and conceptual biases. A complex negotiation witnessed in the working processes of previously unnarrated drawings, models, and prints.

At this stage, do I know this Malaysia? Is this what I expected from the show? I don’t know. While I have a clearer understanding of the displayed items along with its intentions, my search for history, politics, and nationalism continues. As I look at the photographs, the exhibits, and enjoyed the sensory simulator, the exhibition is a memory of a Malaysia strange yet familiar…

17Zoe Ryan (ed.), As Seen: Exhibitions that made Architecture and Design History (Chicago, IL: Art Institute of Chicago, 2017), 15.

Wandering,

I am still

lost—a

contemporary

ghost strolling

around a forgotten

exhibition. I

could go no

further in this

memory theatre

but to look

elsewhere for

answers. My

ghosting has come to an end. For

now.

Acknowledgements

This article would not be possible without the support of Sarah Victoria Turner, Hammad Nasar, Baillie Card, Maisoon Rehani, Marquard Smith, Pam Meecham, and Tew Sophen.Kindly note that all the mistakes found in this article are entirely mine.

About the author

-

Kelvin Chuah is a writer and researcher with a keen interest in exhibition histories. As an MPhil Candidate at UCL, Institute of Education, his research draws upon personal memories to meta-narrate forgotten Malaysian exhibitions at the Commonwealth Institute.

Kelvin also looks for serendipity in archives and libraries in search of forgotten stories.

Footnotes

-

1

Simon Sadler, Archigram: Architecture Without Architecture (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2005), 54. ↩︎

-

2

Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities, revised edn (London: Verso, 2006). ↩︎

-

3

Perdana Leadership Foundation, “Rukun Negara: The National Principles of Malaysia”, 19 September 2016, http://www.perdana.org.my/index.php/spotlight2/item/rukun-negara-the-national-principle-of-malaysia. Accessed 25 January 2019. ↩︎

-

4

Peter Wicks, “The New Realism: Malaysia since 13 May, 1969”, The Australian Quarterly 43, no. 4 (December 1971): 20–21, http://www.jstor.org/stable/20634465. Accessed 12 May, 2019. ↩︎

-

5

Commonwealth Institute, Annual Report of the Director to the Board of Governors (London: Commonwealth Institute, 1973), 8 and 12–13. ↩︎

-

6

Chee-Kien Lai, “Concrete/Concentric Nationalism: The Architecture of Independence in Malaysia, 1945–1969”, PhD dissertation, University of California, Berkeley, 334. ↩︎

-

7

Lai, “Concrete/Concentric Nationalism”, 334–335. ↩︎

-

8

Architectural Design, “Archigram as Architects”, Architectural Design (1974): 387–388. Project by Centre for Experimental Practice, “Malaysian Exhibition”, Archigram Archival Project (2010), University of Westminster, http://archigram.westminster.ac.uk/project.php?id=171. Accessed 10 January 2018. ↩︎

-

9

Project by Centre for Experimental Practice, “About Archigram”, The Archigram Archival Project, 2010, University of Westminster, http://archigram.westminster.ac.uk/about.php?pg=archi. Accessed 10 January 2018. ↩︎

-

10

Peter Cook, ed. *Archigram *(New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1999), 2–3. ↩︎

-

11

Lai, “Concrete/Concentric Nationalism”, 252 and 335. ↩︎

-

12

Lai, “Concrete/Concentric Nationalism”, 335. ↩︎

-

13

Centre for Experimental Practice, “About Archigram”, The Archigram Archival Project. ↩︎

-

14

Cook, Archigram, 94. ↩︎

-

15

Commonwealth Institute, Annual Report of the Director to the Board of Governors (London: Commonwealth Institute, 1974), 15; Commonwealth Institute, Annual Report of the Director to the Board of Governors (London: Commonwealth Institute, 1975),18; Commonwealth Institute, Annual Report of the Director to the Board of Governors (London: Commonwealth Institute, 1976), 17; and Commonwealth Institute, Annual Report of the Director to the Board of Governors (London: Commonwealth Institute, 1977), 16. ↩︎

-

16

Born and raised in Malaysia, Izan Tahir received her education at the London College of Printing in the 1960s. She was a designer employed by Terence Conran when she visited Instant Malaysia in 1973. Izan witnessed the political and cultural developments in the UK and experienced the tumultuous formation of Malaysia as a new nation-state. I had this conversation with Izan on 4 December 2017. ↩︎

-

17

Zoe Ryan (ed.), As Seen: Exhibitions that made Architecture and Design History (Chicago, IL: Art Institute of Chicago, 2017), 15. ↩︎

Bibliography

Anderson, Benedict (2006) Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, revised edn, London: Verso.

Architectural Design (1974) “Archigram as Architects”: 387–388.

Benjamin, Walter (2002) The Arcades Project. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bettmann (1969) “Post-Riot Scene in Kuala Lumpur”. Getty Images, https://www.gettyimages.co.uk/detail/news-photo/patrol-streets-kuala-lumpur-malaysia-troops-of-the-malay-news-photo/515103668. Accessed 20 February 2019.

Butcher, Henry (2017) 32, Sultan Ismail Nasiruddin Shah, May’ 69—Kuala Lumpur Berkurong, 1969, 23 April, Malaysian & Southeast Asian Art. http://www.hbart.com.my/files/MSEAAAPR17-web.pdf. Accessed 20 February 2019.

Centre for Experimental Practice (2010) “Malaysian Exhibition”. Archigram Archival Project, University of Westminster. http://archigram.westminster.ac.uk/project.php?id=171. Accessed 10 January 2018.

Cook, Peter, ed. (1999) Archigram. New York: Princeton Architectural Press.

Commonwealth Institute (1964) Annual Report of the Director to the Board of Governors, London: Commonwealth Institute.

Commonwealth Institute (1973) Annual Report of the Director to the Board of Governors, Commonwealth Institute, London: Commonwealth Institute.

Commonwealth Institute (1974). Annual Report of the Director to the Board of Governors, Commonwealth Institute, London: Commonwealth Institute.

Commonwealth Institute (1975) Annual Report of the Director to the Board of Governors, Commonwealth Institute, London: Commonwealth Institute.

Commonwealth Institute (1976) Annual Report of the Director to the Board of Governors, Commonwealth Institute, London: Commonwealth Institute.

Commonwealth Institute (1977) Annual Report of the Director to the Board of Governors, Commonwealth Institute, London: Commonwealth Institute.

Commonwealth Institute (2010) The Archigram Archival Project, University of Westminster. http://archigram.westminster.ac.uk/project.php?id=171. Accessed 10 January 2018.

Crompton, Dennis (2012) A Guide to Archigram 1961–74. New York: Princeton Architectural Press.

Gabriel, Sharmani P. (2015) “The Meaning of Race in Malaysia: Colonial, Post-Colonial and Possible New Conjunctures”. Ethnicities 15, no. 6: 782–809. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/. Accessed 12 April 2017.

Lai, Chee-Kien (2005) “Concrete/Concentric Nationalism: The Architecture of Independence in Malaysia, 1945–1969”. PhD dissertation, University of California, Berkeley.

Perdana Leadership Foundation (2016) “Rukun Negara: The National Principles of Malaysia”. 19 September. http://www.perdana.org.my/index.php/spotlight2/item/rukun-negara-the-national-principle-of-malaysia. Accessed 25 January 2019.

Ryan, Zoe (ed.) (2017) As Seen: Exhibitions that made Architecture and Design History. Chicago, IL: Art Institute of Chicago.

Sadler, Simon (2005) Archigram: Architecture Without Architecture. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Upton, Alex (2018) “The London Design Museum by John Pawson, OMA+ Allies And Morrison’. London Architectural Photographer. https://www.alexuptonphotography.com/london-design-museum/1. Accessed 20 February 2019.

Walker, Dave (2012) “Almost Forgotten: The Commonwealth Institute”. The Library Time Machine. https://rbkclocalstudies.wordpress.com/2012/06/28/almost-forgotten-the-commonwealth-institute/. Accessed 10 January 2019.

Wicks, Peter (1971) “The New Realism: Malaysia since 13 May, 1969”. The Australian Quarterly 43, no. 4 (December): 20–21. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20634465. Accessed 12 May, 2019.

Wilson, Tom (2016) The Story of the Design Museum. London: Phaidon Press.

Imprint

| Author | Kelvin Chuah |

|---|---|

| Date | 30 September 2019 |

| Category | Article |

| Review status | Peer Reviewed (Double Blind) |

| License | Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) |

| Downloads | PDF format |

| Article DOI | https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-13/kchuah |

| Cite as | Chuah, Kelvin. “Instant Malaysia: Imagining a Nation at the Commonwealth Institute.” In British Art Studies: London, Asia, Exhibitions, Histories (Edited by Hammad Nasar and Sarah Victoria Turner). London and New Haven: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art and Yale University Press, 2019. https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-13/kchuah. |