Mapping Decolonisation

Mapping Decolonisation: Exhibition Floor Plans and the “End” of Empire at the Commonwealth Institute

By Claire Wintle

This article explores the relationship between “permanent” exhibitions and political flux. Offering a close reading of London’s Commonwealth Institute and its intriguing gallery floor plan of 1969, it considers the interaction between display, exhibition graphics, and imperial change. While the British Empire crumbled (reforming in more clandestine guises), and new nation-building programmes took place around the world, the Commonwealth Institute became a dynamic site of neo-imperial and nationalist agendas, with diplomats, designers, and educators from Asia and beyond all working to re-territorialise, redistribute, and challenge British hegemony. Through this history of the Commonwealth and its exhibitions, the article offers broader lessons on the possibilities and limits of an exhibition’s ephemeral archive, the embodied, fragile nature of exhibition making, and the limits of ‘decolonisation’ as a productive term in the current drive to develop socially just exhibitions.

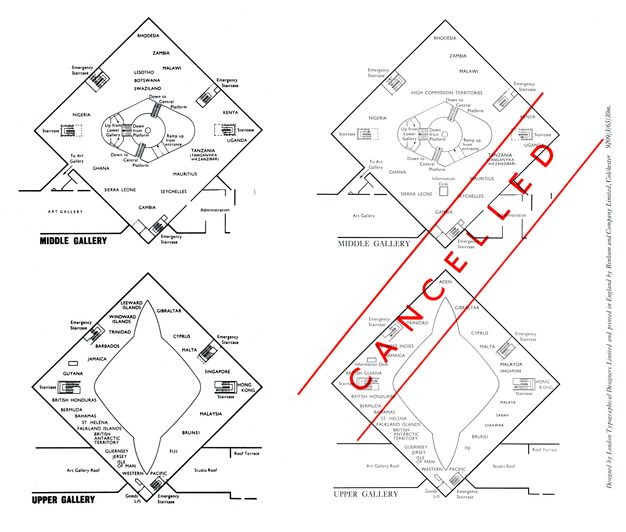

On the final two pages of a handbook describing the work of the Commonwealth Institute in the 1960s, two near-identical maps printed in black ink on white card are arranged in neat alignment, side by side (fig. 1). Both maps depict a plan of the middle and upper floors of the Commonwealth Institute’s exhibition galleries at two different moments—in 1965 and 1969. The map on the right has a red “CANCELLED” banner emblazoned across the original graphic, drawing attention to the material changes that had apparently affected the galleries in the years between their production. The floor plans—as with all exhibition maps—were designed to show the spaces available to visitors, and to define and explain the spatial arrangements and content of the galleries in an accessible and simplified two-dimensional form. The printed lines of the maps thus mark the physical and conceptual boundaries of the Commonwealth Institute. The changes in the floor plans, both physical and conceptual, are the subject of this essay; tracking these changes helps us to map shifting practices at the Institute across the 1960s, and understand how they aligned with and contributed to the complex and contradictory processes of “decolonisation” that occurred both in the galleries and the world beyond (fig. 2).

The Commonwealth Institute was a new cultural centre that had opened in 1962, located in Holland Park on the western edge of central London. The successor to South Kensington’s Imperial Institute, it was intended to “foster the interests of the Commonwealth by information and education services designed to promote among all its people a wider knowledge of one another and a greater understanding of the Commonwealth itself.”1 Its great square structure, capped with its spectacular tent-like copper roof and flanked by an adjoining block, incorporated a library, art gallery and cinema, book shop, several reception rooms, and 60,000 square feet of exhibition galleries spread over three floors. In the exhibition galleries at the Institute, individual display areas were allocated to each of the Commonwealth countries and “dependent territories”. They were represented through a multi-sensory mix of dioramas, mural paintings, sculptures, models, taxidermy, photographs, everyday objects, graphics, and interpretative text. Exhibits aimed to depict “not only the history and geography” of each particular country, but also their “contemporary economic, social, cultural and constitutional development”.2 In the Handbook, both maps identified the inclusion and position of each of the Commonwealth member states in the galleries, labelling every country by name in uppercase sans serif typeface. In as much as all maps are selective models of perceived reality that make the world anew,3 the maps depict the Commonwealth Institute, but they are also representations of the Commonwealth itself.

1Yet, both the Commonwealth and the Institute were undergoing intense change in the 1960s. In a display space that sought “always [to] present contemporary and not outdated pictures” of the countries concerned, “the portrayal within ‘permanent’ exhibitions of so much that is impermanent” was acknowledged by Institute staff as “the most difficult of our problems”.4 Between the design of the right-hand map in 1965 and the second one on the left in 1969, political shifts on the world stage had been rapid, and national and colonial boundaries were being redrawn in several regions. The Commonwealth itself had shifted from a “comfortable and cooperative erstwhile club of white Dominions” into a multiracial forum dominated by the newly independent nations of Africa and Asia.5 In September 1963, Sarawak and Sabah were among the crown colonies that joined with the Federation of Malaya to become the Federation of Malaysia; British Guiana emerged as Guyana in May 1966 and Barbados gained independence in November 1966. In August 1964, a single high commission for the protectorates of Basutoland, Bechuanaland and Swaziland was abolished, with Basutoland gaining independence as Lesotho in October 1966, Bechuanaland as Botswana in September 1966, and Swaziland (now Eswatini) in September 1968. When Aden became part of an independent South Yemen in November 1967, the new country declined to join the Commonwealth.

4Each of these constitutional shifts required amendments on the gallery floor. On the map and in the exhibits themselves, country names were changed, exhibits added, divided, or, in the case of Aden, entirely removed (see interactive map). Eventually, in 1969, the decision to supplement the original Handbook with a four-page textual explanation of wider changes across the Institute and an additional map was unavoidable. Presumably for budgetary reasons, the majority of the 1969 handbook appears to have been reprinted using the original printing plates from 1965. The new edition took the form of the earlier design, but a “supplement”—including the new map—was inserted. In the 1969 edition, the 1965 map was nullified through the use of an additional plate which formed the word “CANCELLED” framed by fine parallel lines. During the printing process the red type seems to have been applied to the page first, followed by the 1965 map, printed from the original plate in black ink.6

6The bolder typography included in the new map from 1969 on the left-hand side might imply a confidence in the permanence of the new exhibitionary and geopolitical arrangements. Yet the urgency and anxiety of the “CANCELLED” banner, amplified in red and strengthened by the contrast of just two colours, hints at a certain desperation on the part of Institute staff at the impossibility of keeping up with constitutional change. As Kenneth Bradley, the Institute’s director, confided to readers of the Commonwealth Institute Journal as early as 1964, keeping abreast of political shifts in the exhibition space was “inevitably a continuous and sometimes rather arduous process … Our purely private hope is that one day the Commonwealth will settle down and give us a breathing space!”7

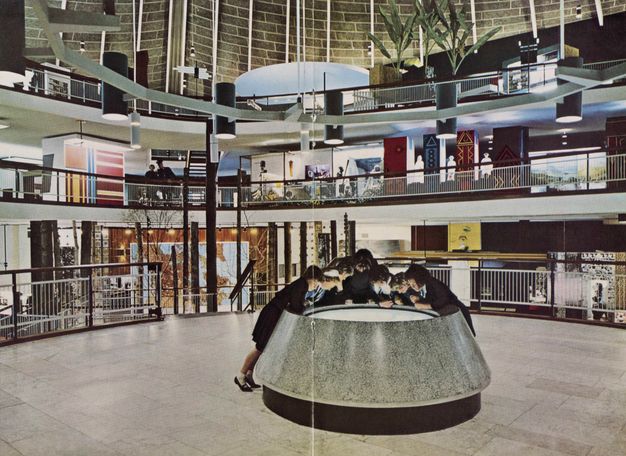

7Maps and exhibition spaces have long been understood as “institutions of power”.8 Distinguished map historian J.B. Harley famously described cartography as “a teleological discourse, reifying power, reinforcing the status quo, and freezing social interaction within charted lines.”9 Within the field of museum studies, Michel Foucault’s conceptualisation of the relationship between power and knowledge, the politics of space, and the mechanisms of governmentality have been similarly influential in reframing the museum as a civilising instrument “designed to effect consensual governance through the organization and transmission of culture.”10 In the case of the Commonwealth Institute, the architectural historian Mark Crinson has argued that the building’s architecture and spatial syntax offered a panoptic display which provided visitors with a “specular dominance over the world of the Commonwealth” (fig. 3).11 To adapt, once more, the words of J.B. Harley, maps and museums, and indeed maps of museums, have been largely couched as “a language of power, not of protest”.12

8

But the double-map feature contained within the Commonwealth Institute’s Handbook hints at the limits of maps and museums as totalising entities through which powerful institutions affect influence. Although archives, too, are often positioned as sites of control through which to cover up complexities on the ground,13 here the materiality of the guidebook, in which a defunct map is physically juxtaposed with a replacement, explicitly highlights the embodied, messy, and fragile nature of work at the Commonwealth Institute and in the Commonwealth at large. Scholars have drawn attention to the phenomenon of “counter maps”, in which techniques of map-making are used “to re-territorialise the area being mapped and to make a case for the redistribution of resources”.14 Such counter maps act to “re-frame the world in the service of progressive interests and to challenge inequality”.15 As this essay will demonstrate, much of the work at the Commonwealth Institute was directly aligned with a regressive aspect of mid-century “decolonisation” (often suppressed in contemporary calls to “decolonise” the museum) in which those in positions of power present themselves as gracefully bestowing “freedom”, even while retaining and reconstructing imperial influence over economic and cultural practices under models of “development” and “partnership”.16 As we shall see, mapping “decolonisation” at the Commonwealth Institute also involved such neo-imperial methods. There was no end of empire at the Commonwealth Institute. Yet the practical realities of exhibition work at this time, which necessitated the unusually swift turnaround of displays and relied on limited and particular forms of funding, meant that diverse agents and more progressive forms of decolonisation also made inroads into the work of the Institute. In what follows, guided by the map, the Commonwealth Institute will be charted as a space in which those in the former colonies could in part articulate their own vision of a “decolonising” world, working to re-territorialise, redistribute, and challenge (some forms of) inequality. As we shall see, driven by independence movements across the world and the realities of museum practice, the double map in the Handbook has some characteristics of the “counter map”: it is a language of power, but contra Harley, also one of protest.

13There were several unique aspects of the Commonwealth Institute’s structure that demanded its active response to political change to a greater extent than any other exhibition space in the UK at this time.17 In addition to the Institute’s contemporary focus highlighted above, the organisation’s public premise as “an outstanding example of that close functional co-operation which characterises the modern Commonwealth”18 lent an expectation that its exhibitions would be informed by international collaboration. In the run up to the Institute’s opening, between 1957 and 1961, Bradley and his staff visited Malta, Cyprus, Aden, India, Pakistan, Ceylon, Uganda, Kenya, Tanganyika, Zanzibar, Malaya, Singapore, Borneo Territories, Australia, New Zealand, Fiji, and Canada. The brief trips were designed to gain knowledge of “contemporary conditions”, develop networks of support within the respective governments concerned, and facilitate discussions about exhibition designs with partners in the countries to be represented.19 In 1965, Bradley, accompanied by the consultant exhibition designer James Gardner, visited Ghana again. Here the two men worked in “close co-operation” with government officials, designing the exhibition “on the spot” and obtaining exhibits for display.20

17In a more sustained process of cooperation that worked to create a significant level of accountability among staff, the Institute’s board of governors included high commissioners to the UK of various Commonwealth countries. In 1958, following the passing of the Commonwealth Institute Act, in which the new name and purpose passed into law, representatives of newly independent Ghana and the Federation of Malaya joined representatives of Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, India, Pakistan, Ceylon, and Southern Rhodesia as governors of the Institute. Alhaji Abdulmaliki, acting commissioner for Nigeria, and the commissioners for British West Indies, British Guiana and British Honduras, and East Africa were also included.21 Throughout the 1960s, as the Commonwealth grew, so did membership of the board, and an education committee also comprised representatives of the various high commissions. High commissioners were seen by the Institute’s British staff as a practical conduit to their home countries’ governments.22 They informed the processes and practices of the Institute inasmuch as their approval or dissent was registered in the Institute papers,23 and their officers regularly engaged with the production of specific exhibits. For example, Tanganyika’s 1961 exhibition was developed with its high commissioner, Mr Dunstan Omari, “under his direction”;24 and many other more practical alliances also took place (fig. 4).25 Some used the space in their own, politically astute way: in 1965 and 1966 alone, diplomats from Barbados, Ceylon, Gambia, Ghana, Guyana, Jamaica, Malta, Nigeria, Trinidad and Tobago, and Uganda held private receptions in the galleries, with the high commissioner for Kenya noted for hosting a party of 2,000 guests.26

21

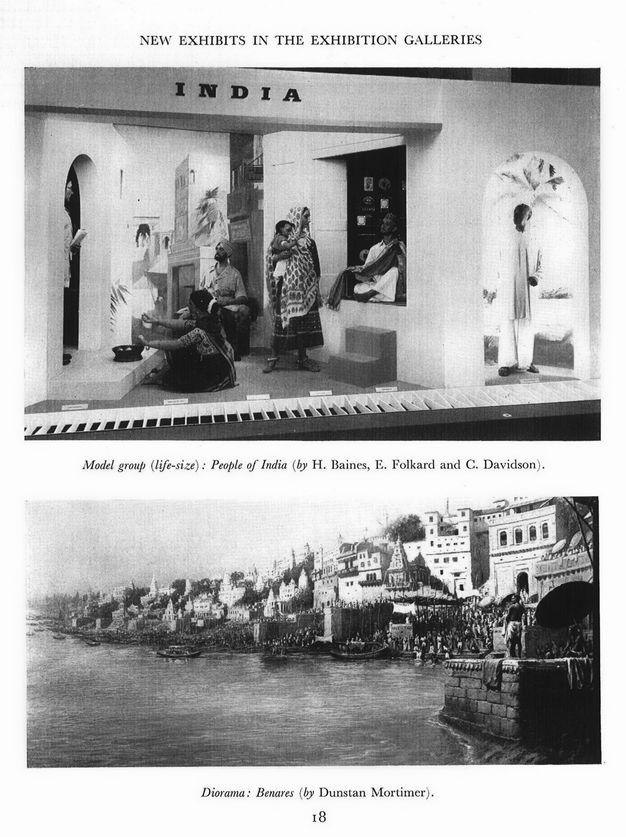

Perhaps the most influential driving factor in the Commonwealth Institute’s interaction with political change was its reliance on the grants contributed by the governments of the countries represented. Each country was responsible for the production and maintenance costs of its own exhibitions, and countries often contributed further grants to the wider costs of the Institute. Between 1953 and 1958, for example, the governments of Ceylon, India, and Pakistan contributed £7,225, £8,843, and £7,170 respectively,27 with the Government of India in 1958 paying for a new diorama of Benares, as well as a group of life-size human figures depicting a “Parsee Businessman”, “Marwari woman”, “Sikh solider”, “Woman and child from the Deccan”, “Muslim merchant”, and “South Indian Brahmin”, all set within a street scene and made by H. Baines, E. Folkard, and C. Davidson. (fig. 5)28 Governments also gave gifts in kind, such as the government of Pakistan’s 1965 donation of “a plaster cast of a fine example of Gandhara sculpture, carpets, textiles, and arts and crafts”.29 They additionally funded education officers and lecturers from their various countries to work with school groups and other audiences, both in the Institute and across the UK (fig. 6). These close working arrangements resulted in a “never-ending process”30 of responding to political change and the practical requests of the Commonwealth governments involved. Bradley regularly described the “difficult” work “necessitated by” government demands and the pressures of maintaining “accurate and up-to-date” exhibitions and educational services: as he suggested, “the achievement of independence must always be made [visible] immediately”.31

27

Despite the added labour that the structural frameworks of the Institute necessitated, such cooperation with Commonwealth governments was the cause of great celebration within the Institute and by Bradley in particular. Most of the examples introduced above were described in the annual reports and official Journal of the Institute. The repeated and public dissemination of this continuous, dynamic activity supported Bradley’s clear agenda to demonstrate the validity of the Institute and make a claim for its continued funding, both from foreign governments and the UK’s Department of Education and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office. For Bradley, the pressure upon the British staff at the Institute from foreign governments to reconstruct their exhibits demonstrated “so clearly the value which other commonwealth governments set” on the Institute.32 As an example of this repeated emphasis on the contemporaneity and responsiveness to international agendas, we might even read the inclusion of the double map in the 1969 edition of the Handbook as evidence of this desperation to retain relevance in a changing world.

32But archival evidence, less in the public eye, also demonstrates the genuine difficulties that the Institute’s structures presented to the practicalities of exhibition work, as well as the challenges they posed to British control. Documents, likely authored by Bradley and written in preparation for the reframing and relocation of the Institute in the late 1950s, describe how “the necessity for obtaining grants of various kinds each year from 47 separate governments makes accounting complicated and revenues uncertain”.33 India’s refusal to pay a general maintenance grant and preference for giving £500 a year for the improvement of its court caused “constant difficulty … because it is not always desirable or possible to spend £500 in this way within one financial year”.34 The “relative poverty” of some countries prevented their governments from meeting their commitments to the Institute,35 and on other occasions, in the case of Nigeria in 1968 for instance, the civil war, described in the Annual Report as unspecified “political difficulties”, caused funding delays for the Institute and a “difficult phase” in the exhibition department.36

33Furthermore, despite his regular published celebrations of the “practical co-operation” between nations imbedded in the work of the Institute,37 Bradley also found the associated challenges to his authority and the artistic and pedagogic vision for the Institute problematic. In an extraordinary diatribe about the “important question of principle involved” in redistributing creative control to those in other countries, he described his partners’ interest in the displays as one of several “important difficulties to be overcome”.38 He bemoaned how:

3739the Overseas Governments who give the grants sometimes try to dictate to the Institute as to the content of their exhibitions or, worse still, insist on carrying out the work themselves … South Africa insisted on rebuilding its own Court, rather than allowing the Institute to do it, and the result is, as they now admit, aesthetically deplorable and educationally inadequate … Canada designed and built their own Court in 1948. About half of it would be suitable only for a Trade Fair.39

For Bradley, Canada’s continued position of “look[ing] after its own Court itself and at its own expense” was deemed “generous, but as it virtually removes this Court from the control of the Institute and leaves the Institute no say in its educational content it is undesirable.”40 He expressed his fear at the possibility that India might also threaten to implement a similar scheme.41 As this document might suggest, and as several contemporary and more recent commentators on the Institute have argued, in some respects, the Institute under Bradley projected a “spurious egalitarianism”,42 “echoing imperial ways of seeing distant territories as ordered, described and laid out, from and for the core of Empire.”43

40But if Bradley imagined the Commonwealth Institute as a site through which to continue imperial practices of paternalist control, both the archive and the map suggest the limit of his opportunities. From the 1950s onwards, at the Institute, the (former) empire’s capacity to “strike back” continued: in 1960, South Africa left the Commonwealth, removing its funding entirely; despite Bradley’s complaints, in 1962 Canada opened an exhibition that had been completely designed and built in Ottawa,44 and by 1978, India’s foreign secretary, Jagat Singh Mehta, had commissioned the National Institute of Design in Ahmedabad to redesign and construct a new permanent display in London. Indeed, due to production delays in India and strikes in London during the Winter of Discontent, NID staff completed the India: A Whole World in her Self exhibit while in the UK, taking over the Commonwealth Institute’s own equipment and machinery during the installation.45 The Commonwealth Institute was thus not a straightforward technology of control. A growing body of scholarship has highlighted the inconsistencies and failures of museums as “disciplinary regimes”, and the need to credit a broader range of actors in the practice of meaning making.46 Here, the neo-colonial tendencies of the Commonwealth Institute were challenged by a wide range of participants who were interested in how their nations were represented.47 The double map in the Handbook is just one piece of evidence that visually represents both the fragility of the Commonwealth Institute and its reliance on the world beyond the UK.

44

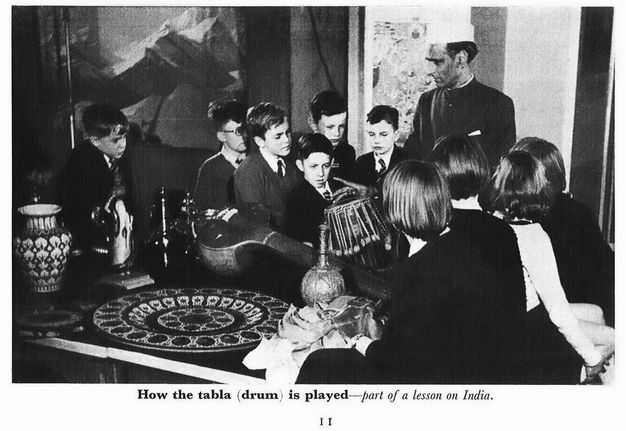

Of course, the displays that emerged from these complex international relationships had limited decolonial potential. They are not the “red-hot cannonballs and bloody knives” of genuine decolonisation called for by Frantz Fanon, and in most cases, the individuals working with Bradley and his team at the Institute could be described as part of Fanon’s despised “colonized ‘elite’”, whose individualist and capitalist values are seen by Fanon as borrowed from the colonialists and preserved intact after their departure.48 Ghana’s new display of 1965, described above as part of a celebrated act of international cooperation, hails the independent nation’s industrial development through an emphasis on a burgeoning cocoa industry and the hydroelectric dam on the Volta River. Both exhibits slotted in very well to the wider use of images of industrialisation in the former colonies to provide “evidence” of the benefits of Western modernisation theory and justification for continued British intervention after independence.49 They might also be seen as championing an elite capitalist agenda that displaced many poorer inhabitants of the Volta River region at great social and economic cost. Many of the exhibits incorporate classically objectifying modes of display, such as life-size human models and dioramas, visual techniques that have long been used as forms of ocular control over geographical space and human cultures.50 In an astonishing British Pathé film of 1959 of the India court that brings Figures 5 and 6 to life, the sight of Mr Angadi, education officer at the Institute, stepping out of the tableau of model human figures in order to demonstrate to British schoolchildren “how the tabla (drum) is played” and how to wear a sari, could certainly be read as a form of exotic spectacle and objectification of the “other” (fig. 7).51 It could also evoke a long, violent history of the display of humans in international exhibitions across the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The film’s clearly white male narrator, the clichéd soundtrack redolent of an Indiana Jones film, and the typecasting of Angadi as “an Indian [here] to introduce his native country”, might cement this exoticisation of India, and heighten our discomfort at an exhibition that certainly says as much about the prevalence of British cultural imperialism in 1959 as it does about Indian society in this period.

48Yet one might also recognise that Angadi, in both the film and the photograph, takes his place at the Institute as a museum professional, a subject specialist and expert member of staff who commands a position of authority in the mediated space of the museum.52 The constructed nature of his performance as an “authentic Indian” is made explicit through the rupture of the tableau as he dramatically emerges from the scene, challenging visitors’ perspectives of a static, timeless country “over there”. Adorned in a khadi kurta and “Gandhi cap”, both popular symbols of the anti-British nationalist struggle in India throughout the twentieth century,53 Angadi interrupts the children’s comfortable “specular dominance”, and physically guides their movements through the gallery and their handling of the Institute’s collections. As such, Angadi is not only a passive subject offered up for British consumption. The children are also bound up in their own rituals of performance, to the camera, and in relation to Angadi: they respond to his guidance within the boundaries of acceptable behaviour, politely acknowledging his seniority and cultural capital. Angadi is of course constrained by the disciplinary structures of the Institute—bound to do his employers’ bidding (and thus informed by both Bradley’s neo-imperial project, and the nationalist agenda of the Indian government which likely paid for his post). Yet, he is also an active part of the Institute’s structures and hints at their complexity. Angadi’s probable long-term residence in the UK blurs the boundaries between “home” and “abroad”. His interaction with the schoolchildren and their incorporation into the film confounds distinctions between performer and audience, and his physical presence ruptures the neat divisions between “Eastern” tradition and “Western” contemporaneity—both hallmarks of the imperial display of colonial cultures. As Ruth Craggs has argued in relation to the use of the Institute by immigrants residing in the residential areas around west London, “to think of the Institute solely in terms of the spectacle of ‘out there’ performed for those ‘at home’ misses some of the ways that it worked for Commonwealth … communities” themselves.54 Angadi, as with the map, further represents some of the direct impact that these communities also had on the Institute’s work.

52Jonathan Hale has described museum graphics, from text labels to museum maps, as having the tendency to distract from the “emotional power of the embodied encounter” in the museum space;55 Carl Knappett, in his contribution to a growing discourse on practices of drawing, describes how the process of representation required in the production of a diagram “reduces all that exhausting flux, movement and creativity to something less manic”.56 Scholars have also linked the abstraction, certainty, and singular perspective often involved in both mapping and exhibition-making to the tendency of these media to portray “a disembodied and emotionless view from nowhere”.57 Maps and museums can work to quieten and ignore the “inherently fragmentary, complex and ambiguous nature of life” and land.58 Certainly, the Handbook’s maps of the Commonwealth Institute have the capacity to distance, distract, and simplify, at the macro and micro level. In the maps, and in the galleries they represent, there is no trace of the trauma and ongoing process of decolonisation as experienced by many of those who lived it. That “Nigeria” remains static and neatly repeated on both maps, fails to acknowledge the horrifying experiences of civil war that ravaged the region, in part as a result of British imperial administrative and exit policies.59 The newly allocated open space surrounding “Malaysia” on the 1969 map does not correlate with the invested presence that British economic interests retained in the Federation after 1963.60 As Harley suggests, maps can be “an impersonal type of knowledge” that “tend to ‘desocialize’ the territory they represent.”61

55Yet here, the permanence, abstraction, and certainty of the printed maps were not only sanitising salves, smoothing over change and distracting from the embodied, confrontational process of decolonisation. They also represented a threatening challenge for Bradley and his team to maintain an impossible stasis, in the galleries, and in the personal relationships that forged them. The maps also reveal rather than efface the “flux” and “movement” of exhibiting decolonisation in the middle years of the twentieth century in ways that have rarely been acknowledged. The "CANCELLED" banner reminds us of the important role that newly independent and decolonising countries had in the wider process of decolonisation, and their physical and metaphorical presence at the heart of the “metropole”. While the banner was perhaps a premonition of the eventual closure of the Commonwealth Institute in 2004, it might also be a lesson for future modes of decolonisation that take seriously a range of claims on exhibition spaces and that might shape all museums moving forwards.

Acknowledgements

I have long been interested in the Commonwealth Institute and I continue to be grateful to the many colleagues who have helped shape my thinking since 2010, when Sue Breakell generously showed me James Gardner’s mid-century designs for the new Institute in the University of Brighton’s Design Archives. These colleagues include Ruth Craggs, Denise Gonyo, Catherine Moriarty, Katherine Prior, Damian Skinner, and Tom Wilson. More recently, I have benefited from stimulating discussions with Nikki Grout, Christian Hogsbjerg, Megha Rajguru, Lesley Whitworth, and Hajra Williams on some of the issues framed here. I am also grateful to Elizabeth Buettner, Sarah Longair, Chris Jeppesen, and William Carruthers for organising the conferences at which I shared some of these ideas, and to Sarah Victoria Turner and colleagues at the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art for commissioning the article and for continuing to provide such a stimulating and inclusive environment for my work. Thanks also to Baillie Card, Maisoon Rehani, and Tom Scutt for their support with editorial, image, and digital work, and to the peer reviewers of this piece.

About the author

-

Dr Claire Wintle is Principal Lecturer in the History of Art and Design and Museum Studies at the University of Brighton. She is the author of Colonial Collecting Display: Encounters with Material Culture from the Andaman and Nicobar Islands (New York: Berghahn, 2013), and with Ruth Craggs (KCL), is editor of Cultures of Decolonisation: Transnational Productions and Practices, 1945–1970 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2016). Her current project on UK museum practice, 1945–1980, received support from a Mid-Career Fellowship from the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art.

Footnotes

-

1

Commonwealth Institute, Commonwealth Institute: A Handbook Describing the Work of the Institute and the Exhibitions in the Galleries (London: Commonwealth Institute, 1969 [1965]), 6. ↩︎

-

2

Commonwealth Institute, Commonwealth Institute, 33. ↩︎

-

3

J.B. Harley, The New Nature of Maps: Essays in the History of Cartography, edited by Paul Laxton (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001), 53. ↩︎

-

4

Commonwealth Institute, Commonwealth Institute, 24–25. ↩︎

-

5

K. Srinivasan, “Nobody’s Commonwealth? The Commonwealth in Britain’s Post-Imperial Adjustment”, Commonwealth & Comparative Politics 44, no. 2 (2006), 258. ↩︎

-

6

I am grateful to Stefan Dickers at the Bishopsgate Institute (who hold the 1965 edition) and Lesley Whitworth and Barbara Taylor of the University of Brighton Design Archives for helping me to understand this process. ↩︎

-

7

Kenneth Bradley, “Diary”, Commonwealth Institute Journal 2, no. 2 (1964), 28. ↩︎

-

8

Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (London: Verso, 1991), 163. ↩︎

-

9

Harley, The New Nature of Maps, 79. ↩︎

-

10

Lara Kriegel, “After the Exhibitionary Complex: Museum Histories and the Future of the Victorian Past”, Victorian Studies 48, no. 4 (2006), 683. Kriegel offers a useful summary of both this Foucauldian literature, including the seminal work of Tony Bennett and Eilean Hooper-Greenhill, and a review of the scholarship that has begun to acknowledge its limits. ↩︎

-

11

Mark Crinson, “Imperial Story-Lands: Architecture and Display at the Imperial and Commonwealth Institutes”, Art History 22, no. 1 (1999), 120. ↩︎

-

12

Harley, The New Nature of Maps, 79. ↩︎

-

13

For example, Thomas Richards, The Imperial Archive: Knowledge and the Fantasy of Empire (London: Verso, 1993). ↩︎

-

14

Rob Kitchin, Martin Dodge, and Chris Perkins, “Power and Politics of Mapping”, in Martin Dodge, Rob Kitchin, and Chris Perkins (ed.), The Map Reader: Theories of Mapping Practice and Cartographic Representation (Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 2011), 443; see also David Pinder, “Mapping Worlds: Cartography and the Politics of Representation”, in Miles Ogborn, Alison Blunt, Pyrs Gruffudd, David Pinder, and Jon May (eds), Cultural Geography in Practice (London: Hodder Arnold, 2003), 172–191. ↩︎

-

15

Kitchin, Dodge, and Perkins, “Power and Politics of Mapping”, 443. ↩︎

-

16

On the “imperialism of decolonisation” in a historical context, see Wm. Roger Louis and Ronald Robinson, “The Imperialism of Decolonization”, Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 22, no. 3 (1994): 462–511. For two important perspectives on the imperial complexities of “decolonisation” movements today, see Sumaya Kassim, “The Museum will not be Decolonised”, Media Diversified, 15 November 2017, https://mediadiversified.org/2017/11/15/the-museum-will-not-be-decolonised/ (accessed 13 August 2019); and Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang, “Decolonization is not a Metaphor”, Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 1, no. 1 (2012): 1–40. On the disciplinary differences and contradictions between the use of “decolonisation” as a political, economic, and social process that intensified in the mid-twentieth century, and “decolonisation” as a social justice agenda today, see Claire Wintle, “Decolonising UK World Art Institutions, 1945–1980”, Special Issue: De-Colonizing Art Institutions, OnCurating 35 (2017): 106–111. ↩︎

-

17

Some of these structures have been identified in Claire Wintle, “Decolonising the Museum: The Case of the Imperial and Commonwealth Institutes”, Museum & Society 11, no. 2 (2013): 190–193. ↩︎

-

18

Commonwealth Institute, Commonwealth Institute, 7. ↩︎

-

19

Commonwealth Institute, Annual Report (London: Commonwealth Institute, 1960), 31. ↩︎

-

20

Commonwealth Institute, Annual Report (London: Commonwealth Institute, 1965), 11; Kenneth Bradley, “Diary”, Commonwealth Institute Journal 3, no. 2 (1965): 23–24. ↩︎

-

21

Commonwealth Institute, Annual Report (London: Commonwealth Institute, 1958), 3. ↩︎

-

22

Report on Imperial Institute’s Grants from Overseas Governments, circa 1957. PRO 30/76/816. 9034. National Archives, Kew. ↩︎

-

23

For example, [Kenneth Bradley?], “The Future of the Imperial Institute”, 12 May 1954. ED121/808. 9000. National Archives, Kew. ↩︎

-

24

Commonwealth Institute, Annual Report (1965), 10. ↩︎

-

25

See Wintle, “Decolonising the Museum”. ↩︎

-

26

Commonwealth Institute, Annual Report (1965), 29; Commonwealth Institute, Annual Report (London: Commonwealth Institute, 1966), 31. ↩︎

-

27

Commonwealth Institute, Annual Report (London: Commonwealth Institute, 1961), 32. ↩︎

-

28

Commonwealth Institute, Annual Report (1958), 26. ↩︎

-

29

Commonwealth Institute, Annual Report (1965), 13. ↩︎

-

30

“The New Institute”, Commonwealth Institute Journal 1, no. 1 (1963), 18. ↩︎

-

31

Commonwealth Institute, Annual Report (London: Commonwealth Institute, 1967), 7; Commonwealth Institute, Annual Report (1966), 10. ↩︎

-

32

Kenneth Bradley, “The Institute in 1966”, Commonwealth Institute Journal (1966), 17. ↩︎

-

33

Report on Imperial Institute’s Grants from Overseas Governments, circa 1957. PRO 30/76/816. 9037. National Archives, Kew. ↩︎

-

34

Report on Imperial Institute’s Grants from Overseas Governments, circa 1957. PRO 30/76/816. 9036. National Archives, Kew. ↩︎

-

35

Report on Imperial Institute’s Grants from Overseas Governments, circa 1957. PRO 30/76/816. 9036. National Archives, Kew. ↩︎

-

36

Commonwealth Institute, Annual Report (London: Commonwealth Institute, 1968), 19. ↩︎

-

37

Commonwealth Institute, Annual Report (1968), 11. ↩︎

-

38

Report on Imperial Institute’s Grants from Overseas Governments, circa 1957. PRO 30/76/816. 9035. National Archives, Kew. ↩︎

-

39

Report on Imperial Institute’s Grants from Overseas Governments, circa 1957. PRO 30/76/816. 9034/35. National Archives, Kew. ↩︎

-

40

Report on Imperial Institute’s Grants from Overseas Governments, circa 1957. PRO 30/76/816. 9036. National Archives, Kew. ↩︎

-

41

Report on Imperial Institute’s Grants from Overseas Governments, circa 1957. PRO 30/76/816. 9035. National Archives, Kew. ↩︎

-

42

Crinson, "Imperial Story-Lands", 120. ↩︎

-

43

Ruth Craggs, “The Commonwealth Institute and the Commonwealth Arts Festival: Architecture, Performance and Multiculturalism in Late-Imperial London”, The London Journal 36, no. 3 (2011), 256. See also Wintle, "Decolonising the Museum", 188–190, “Neo-Colonialism at the Institute”. ↩︎

-

44

Commonwealth Institute, Annual Report (London: Commonwealth Institute, 1962), 9. ↩︎

-

45

Vikas Satwalekar, former NID Executive Director, interview with the author, 4 April 2015, Mumbai, India. ↩︎

-

46

Kate Hill, Culture and Class in English Public Museums, 1850–1914 (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2005); Samuel Alberti, Nature and Culture: Objects, Disciplines and the Manchester Museum (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2009), Chapter 6; Claire Wintle, “Visiting the Empire at the Provincial Museum, 1900–1950”, in Sarah Longair and John McAleer (eds), Curating Empire: Museums and the British Imperial Experience (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2012). ↩︎

-

47

I have made a similar argument in Claire Wintle, “Decolonising the Museum”, 188–190. ↩︎

-

48

Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth, trans. Richard Philcox (New York: Grove Press, 2004 [1963]), 1–62, quotations from 3 and 9. ↩︎

-

49

Anandi Ramamurthy, “Images of Industrialisation in Empire and Commonwealth During the Shift to Neo-Colonialism”, in Simon Faulkner and Anandi Ramamurthy (eds), Visual Culture and Decolonisation in Britain: British Art and Visual Culture since 1750, New Readings (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2006). On the role of local cultures in the “neo-colonial” development of the Volta River Project, see Viviana d’Auria, “More than Tropical? Modern Housing, Expatriate Practitioners and the Volta River Project in Decolonising Ghana”, in Ruth Craggs and Claire Wintle (eds), Cultures of Decolonisation: Transnational Productions and Practices, 1945–1970 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2016), 193–196; and for a more detailed reading of other displays at the Institute which combined nationalist and colonial tropes of industry to develop anti-British sentiment, see Claire Wintle, “Decolonising the Museum”, 193–196. ↩︎

-

50

See, for example, Claire Wintle, “Model Subjects: Representations of the Andaman Islands at the Colonial and Indian Exhibition, 1886”, History Workshop Journal 67, no. 1 (2009): 194–207; Stephanie Moser, “The Dilemma of Didactic Displays: Habitat Dioramas, Life-Groups, and Reconstructions of the Past”, in Nick Merriman (ed.), Making Early Histories in Museums (Leicester: Leicester University Press, 1999). ↩︎

-

51

I am grateful to Tom Wilson for drawing my attention to this video. ↩︎

-

52

Rebecca Brown’s instructive work on the performance of craft practitioners from India at the 1985/1986 US Festival of India has shaped my ideas here. Rebecca M. Brown, Displaying Time: The Many Temporalities of the Festival of India (Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press, 2017), 51–85. ↩︎

-

53

Emma Tarlo, Clothing Matters: Dress and Identity in India (London: Hurst & Company, 1996), 62–93. ↩︎

-

54

Craggs, “The Commonwealth Institute and the Commonwealth Arts Festival: Architecture, Performance and Multiculturalism in Late-Imperial London”, 257. ↩︎

-

55

Jonathan Hale, “Narrative Environments and the Paradigm of Embodiment”, in Suzanne MacLeod, Laura Hourston Hanks, and Jonathan Hale (eds), Museum Making: Narratives, Architectures, Exhibitions (Abingdon: Routledge, 2012), 194. ↩︎

-

56

Carl Knappett, “Networks of Objects, Meshworks of Things”, in Tim Ingold (ed.), Redrawing Anthropology: Materials, Movements, Lines (Abingdon: Routledge, 2011), 48. ↩︎

-

57

Rob Kitchin, Martin Dodge, and Chris Perkins, “Power and Politics of Mapping”, in Martin Dodge, Rob Kitchin, and Chris Perkins (eds), The Map Reader: Theories of Mapping Practice and Cartographic Representation (Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 2011), 442. ↩︎

-

58

Laura Hourston Hanks, Suzanne MacLeod, and Jonathan Hale, “Introduction: Museum Making: The Place of Narrative”, in Suzanne MacLeod, Laura Hourston Hanks, and Jonathan Hale (eds), Museum Making: Narratives, Architectures, Exhibitions (Abingdon: Routledge, 2012), xxii. ↩︎

-

59

Chibuike Uche, “Oil, British Interests and the Nigerian Civil War”, Journal of African History 49, no. 1 (2008): 111–135. ↩︎

-

60

Nicholas J. White, “The Survival, Revival and Decline of British Economic Influence in Malaysia, 1957–70”, Twentieth Century British History 14, no. 3 (2003): 222–242. ↩︎

-

61

Harley, The New Nature of Maps, 81. ↩︎

Bibliography

Alberti, Samuel (2009) Nature and Culture: Objects, Disciplines and the Manchester Museum. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Anderson, Benedict (1991) Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso.

[Bradley, Kenneth?] (1954) “The Future of the Imperial Institute”. 12 May. ED 121/808. 9000. National Archives, Kew.

Bradley, Kenneth (1964) “Diary”. Commonwealth Institute Journal 2, no. 2.

Bradley, Kenneth (1965) “Diary”. Commonwealth Institute Journal 3, no. 2: 23–24.

Bradley, Kenneth (1966) “The Institute in 1966”. Commonwealth Institute Journal.

Brown, Rebecca M. (2017) Displaying Time: The Many Temporalities of the Festival of India. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press.

Commonwealth Institute (1958) Annual Report. London: Commonwealth Institute.

Commonwealth Institute (1960) Annual Report. London: Commonwealth Institute.

Commonwealth Institute (1961) Annual Report. London: Commonwealth Institute.

Commonwealth Institute (1962) Annual Report. London: Commonwealth Institute.

Commonwealth Institute (1965) Annual Report. London: Commonwealth Institute.

Commonwealth Institute (1966) Annual Report. London: Commonwealth Institute.

Commonwealth Institute (1967) Annual Report. London: Commonwealth Institute.

Commonwealth Institute (1968) Annual Report. London: Commonwealth Institute.

Commonwealth Institute (1969 [1965]) Commonwealth Institute: A Handbook Describing the Work of the Institute and the Exhibitions in the Galleries. London: Commonwealth Institute.

Commonwealth Institute Journal (1963) “The New Institute”. Commonwealth Institute Journal 1, no. 1.

Craggs, Ruth (2011) “The Commonwealth Institute and the Commonwealth Arts Festival: Architecture, Performance and Multiculturalism in Late-Imperial London”. The London Journal 36, no. 3.

Crinson, Mark (1999) “Imperial Story-Lands: Architecture and Display at the Imperial and Commonwealth Institutes”. Art History 22, no. 1.

d’Auria, Viviana (2016) “More than Tropical? Modern Housing, Expatriate Practitioners and the Volta River Project in Decolonising Ghana”. In Ruth Craggs and Claire Wintle (eds), Cultures of Decolonisation: Transnational Productions and Practices, 1945–1970. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 193–196.

Fanon, Frantz (2004 [1963]) The Wretched of the Earth, trans. Richard Philcox. New York: Grove Press.

Hale, Jonathan (2012) “Narrative Environments and the Paradigm of Embodiment”. In Suzanne MacLeod, Laura Hourston Hanks, and Jonathan Hale (eds), Museum Making: Narratives, Architectures, Exhibitions. Abingdon: Routledge.

Harley, J.B. (2001) The New Nature of Maps: Essays in the History of Cartography, edited by Paul Laxton. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Hill, Kate (2005) Culture and Class in English Public Museums, 1850–1914. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Hourston Hanks, Laura, MacLeod, Suzanne, and Hale, Jonathan (2012) “Introduction: Museum Making: The Place of Narrative”. In Suzanne MacLeod, Laura Hourston Hanks, and Jonathan Hale (eds), Museum Making: Narratives, Architectures, Exhibitions. Abingdon: Routledge.

Kassim, Sumaya (2017) “The Museum will not be Decolonised”. Media Diversified, 15 November, https://mediadiversified.org/2017/11/15/the-museum-will-not-be-decolonised/ (accessed 13 August 2019).

Kitchin, Rob, Dodge, Martin, and Perkins, Chris (2011) “Power and Politics of Mapping”. In Martin Dodge, Rob Kitchin, and Chris Perkins (ed.), The Map Reader: Theories of Mapping Practice and Cartographic Representation. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

Knappett, Carl (2011) “Networks of Objects, Meshworks of Things”. In Tim Ingold (ed.), Redrawing Anthropology: Materials, Movements, Lines. Abingdon: Routledge.

Kriegel, Lara (2006) “After the Exhibitionary Complex: Museum Histories and the Future of the Victorian Past”. Victorian Studies 48, no. 4.

Louis, Wm. Roger and Robinson, Ronald (1994) “The Imperialism of Decolonization”. Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 22, no. 3: 462–511.

Moser, Stephanie (1999) “The Dilemma of Didactic Displays: Habitat Dioramas, Life-Groups, and Reconstructions of the Past”. In Nick Merriman (ed.), Making Early Histories in Museums. Leicester: Leicester University Press.

Pinder, David (2003) “Mapping Worlds: Cartography and the Politics of Representation”. In Miles Ogborn, Alison Blunt, Pyrs Gruffudd, David Pinder, and Jon May (eds), Cultural Geography in Practice. London: Hodder Arnold, 172–191.

Ramamurthy, Anandi (2006) “Images of Industrialisation in Empire and Commonwealth During the Shift to Neo-Colonialism”. In Simon Faulkner and Anandi Ramamurthy (eds), Visual Culture and Decolonisation in Britain: British Art and Visual Culture since 1750, New Readings. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Report on Imperial Institute’s Grants from Overseas Governments, circa 1957. PRO 30/76/816. National Archives, Kew.

Richards, Thomas (1993) The Imperial Archive: Knowledge and the Fantasy of Empire. London: Verso.

Satwalekar, Vikas (2015) former NID Executive Director, interview with the author, 4 April, Mumbai, India.

Srinivasan, K. (2006) “Nobody’s Commonwealth? The Commonwealth in Britain’s Post-Imperial Adjustment”. Commonwealth & Comparative Politics 44, no. 2.

Tarlo, Emma (1996) Clothing Matters: Dress and Identity in India. London: Hurst & Company.

Tuck, Eve and Yang, K. Wayne (2012) “Decolonization is not a Metaphor”. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 1, no. 1: 1–40.

Uche, Chibuike (2008) “Oil, British Interests and the Nigerian Civil War”. Journal of African History 49, no. 1: 111–135.

White, Nicholas J. (2003) “The Survival, Revival and Decline of British Economic Influence in Malaysia, 1957–70”. Twentieth Century British History 14, no. 3: 222–242.

Wintle, Claire (2009) “Model Subjects: Representations of the Andaman Islands at the Colonial and Indian Exhibition, 1886”. History Workshop Journal 67, no. 1: 194–207.

Wintle, Claire (2012) “Visiting the Empire at the Provincial Museum, 1900–1950”. In Sarah Longair and John McAleer (eds), Curating Empire: Museums and the British Imperial Experience. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Wintle, Claire (2013) “Decolonising the Museum: The Case of the Imperial and Commonwealth Institutes”. Museum & Society 11, no. 2: 185–201.

Wintle, Claire (2017) “Decolonising UK World Art Institutions, 1945–1980”. Special Issue: De-Colonizing Art Institutions, OnCurating 35: 106–111.

Imprint

| Author | |

|---|---|

| Date | 30 September 2019 |

| Category | Article |

| Review status | Peer Reviewed (Double Blind) |

| License | Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) |

| Downloads | PDF format |

| Article DOI | https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-13/cwintle |

| Cite as | Wintle, Claire. “Mapping Decolonisation: Exhibition Floor Plans and the ‘End’ of Empire at the Commonwealth Institute.” In British Art Studies: London, Asia, Exhibitions, Histories (Edited by Hammad Nasar and Sarah Victoria Turner). London and New Haven: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art and Yale University Press, 2019. https://master--britishartstudies-13.netlify.app/issues/13/mapping-decolonisation/. |