Yellow Peril

Issue 13

Do Ho Suh’s Who Am We? (2000) is a print composited from photographs of thousands of teenagers’ faces, taken from the artist’s high school yearbooks. Viewed from a distance, the print appears as a sea of unintelligible faces. But up close, with the aid of a magnifying sheet provided by the gallery, the unique contours of the individual faces become visible. While the title Who am We? reads oddly in English, Do’s title is translated directly from his native language of Korean, where the use of woori (우리)—meaning “we”, or “us”—is grammatically correct in the sentence. In Korean, “we” is commonly used in place of “I”, and connotes a grouping or community of people who are aligned.

Born 1962, Do came into adulthood in the 1980s, a period when Korea emerged from decades of military dictatorship to democratic reforms, and became increasingly open to the economic forces of globalisation and innovation. In 1988, when Seoul hosted the Olympics, Korean people were able to obtain more passports than ever before to travel overseas. Although he had already achieved his Bachelor of Arts and Masters of Arts at Seoul National University, Do retrained for his Bachelor of Fine Arts in painting at Rhode Island School of Design, before receiving his Master of Fine Arts in sculpture from Yale University. He has since lived and worked between London, New York City, and Seoul. As an émigré overseas, Do has witnessed and participated in the socio-political shifts of Korean social identity, and his work reflects the tension between the collective and the individual; belonging and difference.

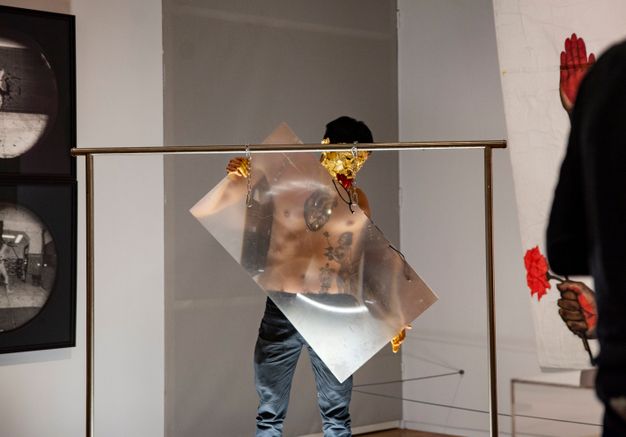

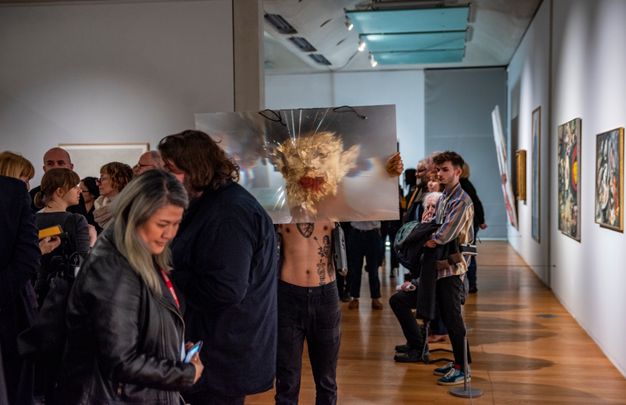

Do’s image was the starting point for the development of Nicholas Tee’s performance at the Manchester Art Gallery, which took place on 6 March 2019 in the spaces of the Speech Acts exhibition at the Manchester Art Gallery. In response to its questions of visibility, scrutiny, and identity, Tee exaggerated Do’s gesture by starting his performance seated behind a large magnifying sheet hung from a rack. Tee similarly invites the audience to inspect him—albeit a version of him that is playfully aggrandised to grotesque proportions—while considering his own position as a Singaporean migrant Chinese performance artist in the UK.\

– Annie Jael Kwan

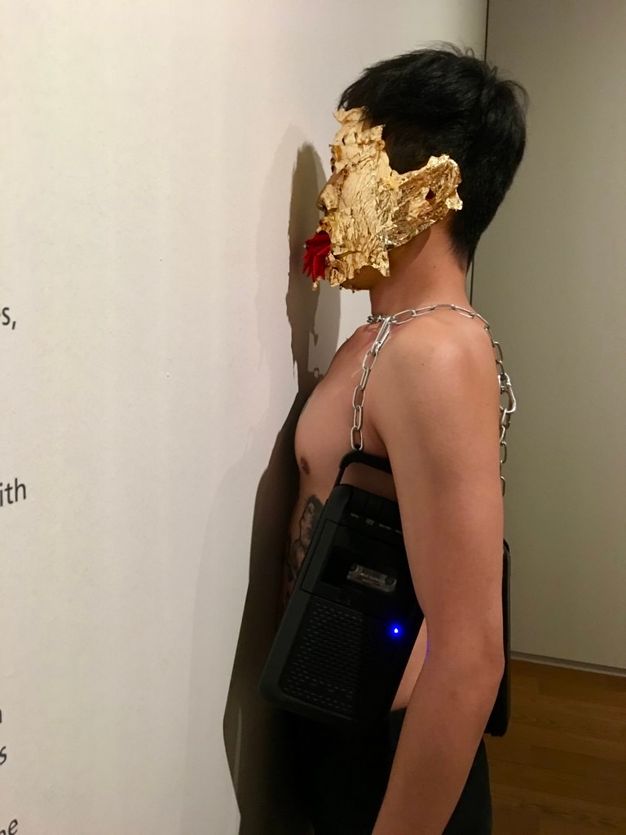

Nicholas Tee’s embodied presence challenges us to look beneath surface perceptions, be they the ambivalent yet profitable prospects of international students, the gilded façades of model minorities, or the uglier layers of prejudice and yellow peril that lie just under the surface. Gold leaf flutters precariously in the ambient breeze. It is inflated by breath, and threatening to peel back to reveal the thick, opaque layer of yellow paint that covers Tee’s face, a contemporary reference to Singaporean artist Lee Wen’s performance series, Journey of a Yellow Man (1992–2012).

If we look at a related image, the GIF that Tee made for this series (Fig. 1), Tee’s gaze is not unwavering, but rather is punctuated by blinking—an all too human gesture of incomprehension, of frustration, and of self-protection that reveals his vulnerability. As he meets the viewer’s gaze, drops of blood trickle down from his forehead, a potent reminder of shared humanity and an indictment of those who refuse to see it.

– Ming Tiampo

In situating himself between Sutapa Biswas’ Housewives with Steak Knives (1985–1986) and Steven Pippin’s Laundromat-Locomotion (Running Naked) (1997), Nicholas Tee invites additional layers of meaning to a work already overflowing with ideas, acknowledgements, and quotations.

Laundromat-Locomotion is Pippin’s tribute to Animal locomotion (1887), Eadweard Muybridge’s pioneering analysis of human and animal motion. In Pippin’s work, a battery of washing-machines-turned-cameras in a public laundromat capture the artist’s naked streak in twelve silver gelatin prints—revealing the relationship between the performance of self, its apparatus of capture, and the site of performance.

Biswas’ iconic work is an artistic claim on diverse genealogies—from Kali, the multi-armed Indian goddess of destruction, to Artemisia Gentileschi’s Judith Beheading Holofernes (circa 1620). Biswas’ Kali wears a necklace made from the severed heads of political and historic “villains”, while one of her hands makes a peace sign—a disorienting mixture of aggression and humour. Its confrontational impact is heightened by the way the work leans forward from the wall.

Tee shares Biswas’ and Pippin’s interest in art history. The yellow paint and gold leaf he applies to his face is a homage to Journey of a Yellow Man (1992–2012), Singapore-born artist Lee Wen’s seminal exploration of race and migration, first performed in London. Wen’s death on 3 May 2019, days before Tee’s performance, lends the latter additional poignancy. Tee also borrows and exaggerates the magnifying sheet used to view Do Ho Suh’s Who Am We? in the next room of the gallery to question epidermal framings, and who is allowed to become “we”.

– Hammad Nasar

The audience to Tee’s performance included other performers. Quietly observing the events unfolding in the Speech Acts galleries was an unlikely witness: James Northcote’s painting of the black actor Ira Aldridge. Made in 1826, Northcote depicted Aldridge in his much-celebrated role as Othello----“the Moor of Venice”----as the title to the artwork declares. Having entered the collection of Manchester Art Gallery in 1882, the presence of Aldridge reminds us of the stories of migration, race, performance, and identity that abound in the histories of British art, yet often remain hidden from view in the permanent displays of our public collections and the more canonical histories of British culture.

Tee’s performance was a reactivation of another historic performance, that of Singaporean Lee Wen’s Journey of a Yellow Man (1992–2012), first performed in London. But in the galleries in Manchester that night, Tee was reactivating, perhaps unknowingly, much longer histories of performance that astounded and shocked audiences in Britain. Born in New York City in 1807, Aldridge had a stage career that not only brought him to Britain but which also saw him perform in mainland Europe, Ireland, and Russia. He died while travelling in Poland. In the portrait, Aldridge looks to the right, to something beyond the heavy gilt frame which we, the viewer, cannot see. This photograph captures the moment that Tee, his face framed by a heavy gold moulding of its own, is about to pass Aldridge. It is a silent, but poignant, conversation across the centuries.

– Sarah Victoria Turner

What does it mean to be there, to witness a performance, an event? Performance art often relies on the special, somewhat cultish status of “being there”. I was there that evening and watched Tee’s performance from beginning to end. Or so I thought----there were definitely bits I missed. I never faced Tee head on, or looked him in the eye via the mediating barrier of his magnifying glass as the photographer has done here. Perhaps I didn’t want to get in the way, or was looking at other things: the other artworks or performances by other members of Asia-Art-Activism. The fragility and imperfections of memory are part of performance art’s beguiling, frustrating nature. Its history is lost even before it has been made. You want to be there, but know that you can never see it all. Photography and film do their best to capture the experience, but can only offer the partial perspective of their operators. Tee plays with these gaps, these distortions of memory and vision. His large mirror, carried in front of his face, both magnifies and blurs. Now you see me, now you don’t.

– Sarah Victoria Turner

In the words of Manchester Art Gallery Fine Art Curator Hannah Williamson, “What is a city if not a civilized place? And you are not civilized unless you have art.”1 Williamson describes the gallery’s civilising role in the city of Manchester, with its beginnings in the 1820s as a site of civic articulation in the context of the city’s booming textiles industry.

Taking his performance into the galleries, Tee haunted the histories presented with his own presence, a return of the repressed colonial to ask which narratives were being told, and which were being obscured or pushed to the edges of the frame? Turning the frame’s gilded peripheries upon themselves, Tee focused attention on his own face, made alien and stuffed with chilli peppers, to gesture at silenced histories of empire that refuse to stay silent.

– Ming Tiampo

1Hannah Williamson in “Insights into Manchester Art Gallery”, Manchester Art Gallery, http://manchesterartgallery.org (accessed 3 September 2019).

Carrying the magnifying sheet, Tee slowly exited the main doors of the Manchester Art Gallery. Outside on the public street, Tee knelt down on the pavement, facing the gallery. Donning black latex gloves, he proceeded to cut his torso with quick shallow slashes, till the words “Bloody Foreigner” were perceptible.

Since the 1970s, artists have employed violence on the body as part of the creative performance. Artists such as Chris Burden, Marina Abramovic, Franko B., and Ron Athey have treated the artist’s body like a canvas that can be shot, slashed, cut, and bled. In the same tradition, Tee utilises his body and blood as media, acting upon a darker interpretation of the exhibition’s focus on “speech acts” as material utterances. Tee depicts how racist slurs can be inflicted and manifested on the body, but the cuts are shallow—only “skin deep”, Tee assured me, when I queried the severity of his wound and possible scaring. The cuts will likely leave no permanent mark, but nevertheless the stings were felt. As he bled, the markings were somewhat faint in the dim streetlight. Beyond the unseen and yet present formal boundaries that delineate artist and audience in the gallery, passers-by stopped to enquire and inspected Tee’s body to discern the wording.

– Annie Jael Kwan

The Manchester Art Gallery has had a history of interventions against its exhibition displays that intertwine activism and art. The British women’s suffrage movement gained momentum in the city of Manchester, with the Women’s Suffrage Committee forming in 1867 to work with the Independent Labour Party to secure votes for women. By 1897, the campaign became increasingly militant and urgent. In 1913, activists Lillian Williamson, Evelyn Manesta, and Annie Briggs entered the gallery and attacked the exhibition displays, breaking the glass of thirteen paintings and even damaging four works. Just over 100 years later, in January 2018, for an art event led by black British artist Sonia Boyce to question the tension between curatorial choice and censorship in producing cultural narratives, the gallery temporarily removed John William Waterhouse’s Hylas and the Nymphs (1896).

In this vein, Tee’s action could be read as a similar attempt to affect the gallery’s exhibition display. After he breached the boundaries of the Manchester Art Gallery, Tee continued his charge up to the second floor and entered the Speech Acts exhibition. Next to the introductory wall text, Tee presses his abdomen against the exhibition wall, in an attempt to imprint the words “bloody foreigner” on its surface. Beneath the stain, he positioned the magnifying sheet as an invitation for the viewer to scrutinise closely. In marking his place within the institution, Tee’s intervention sought to enhance the themes explored by the Speech Acts exhibition in highlighting the contributions of diaspora artists to British art history. Leaving only an almost imperceptible mark after I hurriedly cleaned off the stain, mindful of the institutional pressures around this type of performance and bodily harm, Tee’s work underscores the difficulty of negotiating the institutional structures of power around which art and culture unfold, to make space for unauthorised, disobedient narratives.

– Annie Jael Kwan

Performance art, in its sharpest register, has the capacity to puncture social space; to activate it and make us feel the discomforts, half-secrets, and inconvenient truths we hide within ourselves and our social relations. Its twenty-first-century popularity has in many cases obscured this social pungency. Performance art now features in art fairs, launches gala dinners, and risks being tamed in institutional petting zoos.

This risk of neutering performance is one that Nicholas Tee navigates adroitly through the strategic and tiered withholding of his full plans; shielding the undisciplined edge of his performance from the flattening regimes of display and behaviour that museums, as public spaces, end up policing.

He ended his performance seemingly as planned, by walking through the exhibition and out of the Manchester Art Gallery. Upon reaching the street, however, he carved out the words “BLOODY FOREIGNER” on his own skin. This fragment of the performance had to take place outside the gallery because the city council had denied permission for Tee to cut himself, due to concerns around young people and self-harm. Escaping the confines of the gallery space was agreed with, and indeed recorded by, Annie Kwan, who had coordinated the performances by Asia-Art-Activism, but this plan was strategically kept from the curators of the Speech Acts exhibition, myself and Kate Jesson.

Then, quietly, Tee went rogue. He re-entered the gallery and finished his performance by pressing his body onto the wall, leaving a bloody mark at the entrance of the exhibition. He blindsided Kwan, whose slightly fuzzy photographs of these surreptitious stages are suggestive of the conflicted impulses she must have felt at this unexpected coda to what she had agreed with the artist.

In the short time before these unruly traces were cleaned from the gallery walls, the crimson marks of Tee’s blood were reflected in the different shades of red in Li Yuan-chia’s Untitled (1994) and Rasheed Araeen’s Christmas Day (1997). Together they formed a brief but intense intergenerational conversation evoking the anger, melancholy, resignation, resilience, and defiance that are germane to the immigrant experience.

– Hammad Nasar

Tee has used the GIF format to create images with looped movements as bookends for this recreated timeline of his performance at the Manchester Art Gallery. The final GIF, on the following slide, displays a large flag that was hand-sewn with gold leaf, made in collaboration with embroidery artist, Nicole Chui. Tee titled the flag GIF 谁是自己人?[who are my people?]----an invitation he also extended via a social media call-out for participants to take up space on the flag and be represented alongside him on the British Art Studies website. The question was phrased with an awareness of the complexity and ambivalence imbued in its language, shaped by personal experience and geopolitical realities: the rise of the Chinese economy and its impact on global political and economic exchanges; the majority Chinese representation in his home country of Singapore; his experience of enforced Mandarin language education; and the tendency in the UK to attend to ideas of East and Southeast Asian identity with subsuming notions of orientalism and “Chineseness”.

In 谁是自己人?, Tee’s visage is projected onto the flag with red chillies bleeding out of his mouth. Tee uses chillies as an artistic medium in his performances, because they are a sign that embodies his Southeast Asian identity. He is flanked by portraits of Asian diaspora friends and colleagues----a visual riff that calls back to Do Ho Suh’s print with multiple faces. Like a body with many heads, both alluring and grotesque, Tee’s gaze is fixed steadily on the viewer as the shimmering flag undulates slowly and continuously forwards.

About the author

-

Nicholas Tee is a live artist from Singapore based in London who collages action, image, body, sound, and material through body-based performance, pain, and endurance; his work is often politically charged, angry, messy, and unintelligible. Nicholas also curates Diaspora Disco—a performance club night that platforms East and Southeast Asian artists; his current research is in curatorial activism and the social practice of nightlife. Nicholas received his BA in Performance Arts from the Royal Central School of Speech and Drama and recently completed the MA Live Art programme at Queen Mary University of London.

Nicholas Tee is a live artist from Singapore based in London who collages action, image, body, sound, and material through body-based performance, pain, and endurance; his work is often politically charged, angry, messy, and unintelligible. Nicholas also curates Diaspora Disco—a performance club night that platforms East and Southeast Asian artists; his current research is in curatorial activism and the social practice of nightlife. Nicholas received his BA in Performance Arts from the Royal Central School of Speech and Drama and recently completed the MA Live Art programme at Queen Mary University of London.

Footnotes

-

1

Hannah Williamson in “Insights into Manchester Art Gallery”, Manchester Art Gallery, http://manchesterartgallery.org (accessed 3 September 2019).

Imprint

| Author | Nicholas Tee |

|---|---|

| Date | 30 September 2019 |

| Category | Artist Collaboration |

| Review status | Peer Reviewed (Double Blind) |

| License | Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) |

| Downloads | PDF format |

| Article DOI | https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-13/ntee |

| Cite as | Tee, Nicholas. “Yellow Peril.” In British Art Studies: London, Asia, Exhibitions, Histories (Edited by Hammad Nasar and Sarah Victoria Turner). London and New Haven: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art and Yale University Press, 2019. https://master--britishartstudies-13.netlify.app/issues/13/yellow-peril/. |