The Ecosystem of Exhibitions

Issue 14 – November 2019

Download Contents

The Ecosystem of Exhibitions: Venues, Artists, and Audiences in Early Nineteenth-Century London

By Catherine Roach

Early nineteenth-century London boasted a robust selection of displays, of art and otherwise, which made up a larger ecosystem of exhibitions. Participants in this ecosystem, including exhibition organizers, practitioners, and viewers, were at once mutually supporting and fiercely competitive. Artists banded together in group exhibitions, where many of them hoped to steal the show. Exhibition societies clustered together, benefiting from proximity even as they contended for visitors. Exhibitions and their objects were not consumed in isolation; rather, both the crowded walls of these displays and the busy itineraries of their viewers encouraged comparative viewing. Considering the display history of works by Benjamin Robert Haydon, John Constable, William Hilton, William Etty, John Martin, and Margaret Carpenter, this essay demonstrates how exhibition histories can shed fresh light on nineteenth-century art: first, by providing a new model for interactions among elements of the art world; and second, by uncovering works and artists who are rarely studied today but were vital participants in the ecosystem of exhibitions in their own day.

Introduction

When Jacques-Louis David charged Parisian audiences for a view of his painting The Intervention of the Sabine Women in 1799, a contemporary noted that it was an exhibition in the style of “les Anglais”.1 Over five decades later, a one-man show by Gustave Courbet was similarly described as an exhibition “in the English manner”.2 As these comments indicate, London was the epicentre of innovative exhibition models in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Many modes of display developed there subsequently became common practice, including the one-artist exhibition and the one-work exhibition.3 These ground-breaking British exhibitions have often been figured as precursors to later French displays, notably the Impressionist shows of the 1870s.4 But not every exhibition fits Impressionism’s glass slipper. This article examines early nineteenth-century displays in London from a new perspective. In doing so, I build on an important body of scholarship that emphasizes the diversity and interconnectedness of urban displays, of “fine art” or otherwise.5 Despite important interventions, discussion of such displays is still shaped by the discourse of the avant-garde, in which the academy faces off with outsiders, rivals, or independents.6 But this approach captures only one part of a much larger story.

1I propose instead that we consider displays of all types as parts of an ecosystem of exhibitions. The term ecosystem was coined in the early twentieth century by a scientist who sought a single term that could refer to living creatures and “the whole complex of physical factors forming what we call [their] environment”.7 Since then, this suggestive word has been widely applied, and “its uses continue to proliferate”.8 In applying the concept of the ecosystem to exhibitions, however, I am invoking in some ways its original intent, which was to create a framework in which interactions among individuals, groups, and resources could be assessed collectively.9 Thinking of exhibitions as an ecosystem allows for consideration of both the broader conditions of display and the actions of individual figures who navigated these conditions. As in a biological ecosystem, nineteenth-century exhibits and exhibitors both relied upon and competed with other actors in their environment.

7Here, a word of caution is in order: ideas about the natural world, when applied to human societies, have been used to reinforce existing cultural hierarchies, including those of race, sex, and class. It is emphatically not my intent here to invoke the later nineteenth-century theories of liberal political economy or social Darwinism, in which some types of people were seen as “naturally” fitted to succeed. This project has the opposite intent: to destabilize the hierarchies of art history, by emphasizing London’s central role in generating exhibition practices, by rethinking the relationship between the Royal Academy and other exhibition venues, and by using the study of exhibitions as a means to uncover the careers of non-canonical artists.

In his foundational survey of urban entertainments, The Shows of London, Richard Altick described that city’s varied attractions as enjoying a “healthy symbiotic relationship”.10 But while they were deeply intertwined, exhibitions during this period were not always mutually supporting. Herein lies the usefulness of the concept of the ecosystem, which conveys both intimacy and conflict. By suggesting both fierce competition and mutual dependence, the term ecosystem both encompasses and moves beyond the model of conflict embodied by the prevalent Academy/outsider binary. The modernist narrative—which, despite the revisions of postmodernism, still saturates art history—posits a contest among individuals and assumes, in the words of Linda Nochlin, that “Genius or Talent … like murder, must always out”.11 This narrative has also structured our approach to institutions, positing exhibition venues as rivals duelling for primacy. As far as it goes, this narrative is not wrong: competition was essential to the early nineteenth-century art world—but so were coexistence and collaboration. In other words, these competitors could not do without one another.

10Perhaps the clearest example of this dynamic in ecosystem models of nature is the interdependent yet violent relationship between predator and prey. Both are necessary to the ecosystem. Remove prey and the predators will perish. Remove predators and the prey will first proliferate and then starve. On the individual level, these interactions can be harsh indeed. For the entities destroyed in these processes—for the mouse eaten by a fox, or the artist whose work is upstaged by another exhibit—the fact that these events are part of a larger, mutually sustaining system is cold comfort. But in the broader view, the system enables the development of distinct, specialized types that thrive in connection with each other. Such was the case with nineteenth-century exhibitions, academic and non-academic alike. Of course, except in the most extreme cases, the stakes in the ecosystem of exhibitions were not life or death. For one set of participants, artists, what was at stake was professional success in the moment and enduring reputation in the future.

The ecosystem model has several advantages over previous ways of understanding nineteenth-century exhibitions. Tony Bennett’s influential account of the “exhibitionary complex”, identifies the solidification around 1850 of display as a form of social control, “a set of cultural technologies concerned to organize a voluntarily self-regulating citizenry”, in which the exhibition serves as an alluring environment of visual knowledge and power, “a site of sight accessible to all”.12 One crucial insight of this approach is that art exhibitions are but one part of a larger phenomenon of display; another is the insistence on the central role of the audience. But, as will be explored in more detail below, display spaces in early nineteenth-century London were not “accessible to all”: they reinforced social hierarchy not through the seductive inclusion of all citizens, but through the emphatic exclusion of the working classes. Moreover, these spaces of display and their audiences were not as orderly or self-regulated as Bennett’s account suggests.13 As subsequent scholarship has shown, both before 1850 and after, exhibition-goers often declined to conform to official scripts, instead using spaces of display to their own ends.14 Unlike the “exhibitionary complex”, the ecosystem is not a top-down model; in an ecosystem, important contributions are made by participants at every level, from the fungi to the charismatic megafauna. Exhibition-goers (and their admission fees) were both a resource for which artists and venues competed and active agents who moved among displays and chose how to interact with them. Recently, it has been suggested that “the concept of an ‘exhibitionary complex’ should be replaced with that of ‘exhibitionary networks’”.15 The term network evokes connections among displays, but it does not suggest the nature of those connections, which could be at once harmful and nurturing.

12The ecosystem model allows for a new understanding of art world dynamics, one that encompasses both the interactions of multiple venues and the specifics of individual installations. Art exhibitions were but one element of a well-established round of urban entertainments that were seen and evaluated comparatively, including theatrical performances, concerts, and social events. Within that round, each display venue provided a dynamic environment in which objects interacted with each other. The first part of this article provides a broad overview of the ecosystem of exhibitions in 1820s London. This period saw the culmination of a distinctive phase in the ecosystem of exhibitions in the British capital: the urban display culture initiated during the Seven Years’ War had by this time produced a flourishing and diverse set of attractions, with established customs and procedures; later in the century, these conditions would be altered by the rise of both regular international expositions and powerful art dealers. This first section charts interactions among three sets of actors: organizers of exhibition venues, artists, and audiences.16 It examines how exhibition administrators both rivalled and supported one another, learning from each other’s tactics and poaching each other’s contributors; how artists utilized these multiple venues, deploying works among them strategically; and how viewers chose to consume these diverse offerings.

16The next section considers how a single object fared within this ecosystem, tracing the transit of a well-known work, John Constable’s The Hay Wain, through several galleries in both London and Paris, starting with its public debut at the Royal Academy in 1821, under its original title of Landscape: Noon (fig. 1). The display history of this picture illuminates the conditions that affected the reception of individual works within the ecosystem of exhibitions. It also reveals the diversity of the art exhibited at this moment. At each stop in its journey, The Hay Wain hung alongside compelling objects that are little studied today, although they attracted more audience attention at the time. Many of these works by non-canonical figures such as John Martin and Margaret Carpenter prove equally vivid and worthy of study as the better-known works with which they once shared a gallery.17

17

In examining works displayed together, this article takes its cue from period viewing practices. Early nineteenth-century exhibitions promoted a distinctive mode of vision that took in a range of objects now classified separately. The proximity of multiple attractions and the brisk pace of their consumption encouraged comparative viewing.18 Moving from venue to venue and from exhibit to exhibit, viewers in nineteenth-century London practised a voracious and emphatically cross-referential approach to the consumption of art. “Comparison is the great test of excellence”, proclaimed the critic Robert Hunt in 1821, voicing a widely held belief.19 Both within a single show and moving among several shows, viewers assessed displays against one another, relying on their memories of sights just seen as well as of previous years’ exhibitions.20 These comparisons might take place across a room, across town, or across the great span of history. Most broadly, commentators frequently assessed the productions of the current day against exemplars of the past, asking if individual artists or the national school as a whole could measure up to their illustrious predecessors.21 Attractions were also judged in tandem, with journalists frequently comparing the charms of one venue’s offerings to those of another.22 This approach offers lessons for our own practice of art history today. The ecosystem of exhibitions in early nineteenth-century London had room for—and need for—many different kinds of actors. Considering it as a system with multiple, diverse participants provides a way of thinking beyond the canon, beyond established metrics of quality and assumptions of importance, to reveal a richer, stranger world of early nineteenth-century art.

18The Ecosystem of a City: 1820s London

London in the 1820s boasted a robust selection of displays, the product of more than half a century of steady proliferation and specialization. “London, at present, teems with shows of art”, wrote a critic for the New Monthly Magazine in 1821, citing as evidence group exhibitions at the Royal Academy, the British Institution, and the Society of Painters in Water Colours; the single-artist exhibitions of Benjamin Robert Haydon, John Glover, Thomas Christopher Hofland, Benjamin West, and James Ward; and the domestic galleries of John Leicester, the Marquess of Stafford, Thomas Hope, and the Earl Grosvenor.23 This list is by no means comprehensive, as it leaves out many displays of historic art and archaeology, such as models of a newly discovered pharaonic tomb.24 Some of these forms of display were of more recent vintage than others. While artists’ exhibitions had been around since the 1770s, the opening of domestic galleries to a limited public was a more novel phenomenon, dating from 1806.25 In addition, the first two decades of the nineteenth century saw the foundation of multiple exhibition societies.26 While the Academy remained the premiere venue, it was by the 1820s the first among many.

23Governance of these display venues varied widely. Later in the century, dealers would take a leading role in staging exhibitions, but this was not yet the case in the 1820s.27 Most organizations were administered by artist-members; the British Institution was unusual in that it was run by a group of wealthy patrons.28 Some artists handled the arrangements for displays of their own work or mounted their own thematic shows. In other cases, artists collaborated with businessmen such as William Bullock, who staged the exhibition of Théodore Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa at the Egyptian Hall in 1821.29 Whether undertaken by the artist or a representative, stand-alone displays and their associated publicity efforts could prove crucial in shaping both the initial reception and the lasting reputation of an object.30

27All of these venues competed with each other for admissions fees and critical notice. At the same time, they also contributed to a mutually sustaining environment. Exhibitions were frequently located in close proximity, creating constantly evolving artistic districts, just as they do today.31 Exhibitions held concurrently with that of the Academy, during the months of London’s political and social season, benefited from a wider audience. The Academy, in turn, benefited from the existence of other displays. The British Institution has been described as “not so much a rival to the Academy as a supplement”; this statement applies to many exhibition societies of the day.32 Non-academic organizations could provide “a stepping-stone” to the Royal Academy;33 for example, the marine painter Clarkson Stanfield was elected as an Associate of the Royal Academy soon after resigning his membership in the Society of British Artists, where he had formerly served as President.34 In addition to co-opting the most successful exhibitors from other venues, Academy administrators also adopted their innovations if they proved popular: in 1811, they experimented with the provision of a price list, after this was introduced at the British Institution and the Society of Painters in Water Colours; in 1816, they followed the example of the British Institution by opening a school of painting.35

31On occasion, the leaders of these organizations also shared resources and information. In 1813, Royal Academy administrators overcame the initial reluctance of some members and lent to the pioneering loan show of works by Sir Joshua Reynolds held at the British Institution.36 When the Society of British Artists decided, two decades later, to stage their own loan exhibition, they consulted the Directors of the British Institution on the matter of insurance.37 Of course, relations were not always so harmonious. Royal Academicians often viewed the advent of new contemporary art exhibitions with suspicion; for example, in 1824, Thomas Phillips expressed disdain for the artists who chose to participate in the inaugural show of the Society of British Artists rather than send to the Academy. At the same time—and perhaps protesting too much—he also claimed that “their departure [from] our corner” benefited the Academicians, as it “enabled us to put into execution a long desired object, viz to have no pictures above the whole lengths & it is a great improvement”.38 But competition could clearly also be destructive. As Greg Smith has shown, competition from the newly formed Associated Artists in Watercolour led to an immediate downturn in sales at the Society of Painters in Water Colours, and the Society eventually foundered and split into factions.39 As this example demonstrates, the proliferation of exhibition societies could also stunt the growth of individual organizations.

36

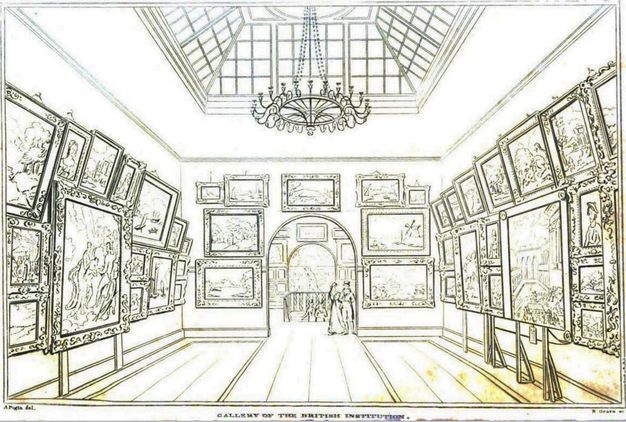

Yet another important set of actors in the ecosystem—artists—benefited enormously from the diversity of exhibition venues. Practitioners did not need to limit themselves to one type of exhibition; indeed, a chief advantage of this system was the ability to exhibit simultaneously at several venues within a single season. Each of these sites had its own character, which came with certain advantages and drawbacks. For example, the Academy exhibitions were prestigious but also increasingly voluminous, making it more challenging for an object to attract attention in a crowded field. Non-Academic venues helped artists, particularly younger artists or those recently arrived in the capital, to build a reputation and find buyers, while preparing for a run at the Academy and its honours. After noting the difficulties of viewing art in the “crowded rooms of Somerset-house”, one journalist claimed that “many a painting, whose merits have escaped notice [at the Academy], has a chance at the British [Institution] of being duly appreciated”.40 Smaller than the Academy and with no places reserved ahead of time for Academicians (who were automatically entitled to show up to eight works at the Academy), the British Institution was an ideal venue for works by emerging artists, as well as for works that had not found a buyer at the previous season’s Academy exhibition (figs 2 and 3).41 As explored in the next section, Constable was one of the many artists who took advantage of this opportunity. Matching work to venue and employing multiple venues were both vital to success in the nineteenth-century ecosystem of exhibitions.

40

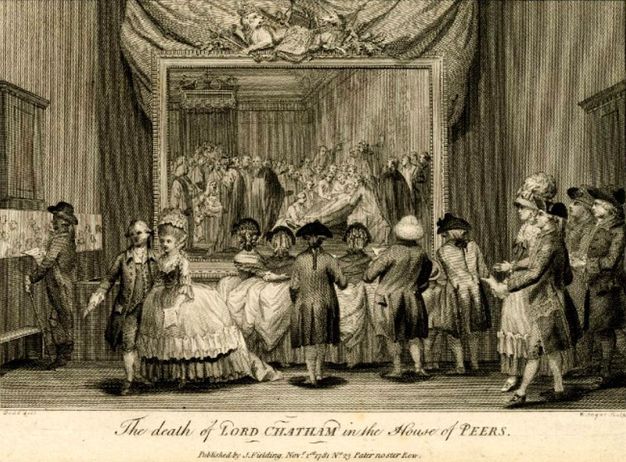

Nor were group shows the only option. In the eighteenth century, artists such as John Singleton Copley had pioneered new display models, including the one-artist and the one-work show. These shows were not necessarily oppositional in nature. Certainly, an exhibition that has been identified as the first retrospective, Nathaniel Hone’s show of 1775, was explicitly anti-Academic.42 But once established, the retrospective was immediately seized upon as an effective new form of display that could be deployed for a variety of ideological purposes. At both the Salon de Correspondence in Paris and at the British Institution in London, retrospectives served nationalist agendas.43 These exhibitions did not critique their respective academies but rather lionized members of those academies in explicitly patriotic celebrations of their national schools. Similarly, for individual artists, exhibiting outside of the Academy did not necessarily mean exhibiting against it. For example, in 1781, Copley angered his fellow Academicians by staging the first one-work exhibition, featuring the Death of the Earl of Chatham (figs 4 and 5). The issue was not clashing artistic philosophies or academic gatekeeping. Instead, Copley’s offense was withholding an object of acknowledged merit from the Royal Academy in order to exhibit it in his own name, for his own profit.44 The decision to go it alone offered both more risk and more reward than submitting works to an exhibition society. Renting a venue, printing a catalogue, and advertising a show required an artist to assume the costs personally or to take on a partner. But such exhibitions also offered more individual attention from viewers and the press, as well as the chance to reap financial rewards, should the exhibition prove popular.

42

By the early nineteenth century, artists’ entrepreneurial exhibitions had become standard practice in London. In contrast, in Paris the regulations of the Académie royale put in place before the French Revolution expressly forbade outside exhibitions due to their commercial associations, and this suspicion of non-academic shows persisted well into the nineteenth century.45 In the British capital, however, being an Academician was no bar to exhibiting outside the Academy. In 1812, the year after he had been elected a full Royal Academician, David Wilkie staged a one-artist show, while also sending a work to the Academy; two years later, another Academician, Richard Westall, complemented his monographic display with an exhibit at the British Institution.46 In 1815, the President of the Royal Academy, Benjamin West, promoted his most recent work through two simultaneous exhibitions. He showed his massive Biblical scene Christ Rejected in a one-artist exhibition, while sending a sketch of this composition to the Academy.47 One journalist helpfully advertised West’s show by noting that his Academy contribution was “the original sketch from which the great picture was painted now exhibiting in Pall Mall”.48 By the 1810s, exhibiting outside the Academy was a tactic employed even by its President.

45The possibilities and perils of this system are illustrated by the career of Benjamin Robert Haydon. Famously, Haydon committed suicide in 1846 after an exhibition of his history paintings at the Egyptian Hall was upstaged by a rival attraction, the little person Charles Stratton, better known as General Tom Thumb.49 Yet for many decades prior, London’s ecosystem of exhibitions had sustained Haydon’s career. Although scholars tend to emphasize his one-man shows, Haydon, like most artists of the period, exhibited at a variety of venues.50 True, due to grievances with both the Royal Academy and the British Institution, he ceased to exhibit with these organizations for much of the 1810s and 1820s.51 But the ecosystem provided other opportunities. Haydon enjoyed a mutually beneficial relationship with several venues: they gave him access to potential buyers and critical attention, while his participation added to their attractions and their reputations. For instance, Haydon’s first major critical triumph occurred in 1814 with the exhibition of his The Judgement of Solomon at the recently founded Society of Painters in Oil and Water Colours.52 When the Society of British Artists was established a decade later, Haydon was quick to take advantage of this new venue, as well.53 He also continued to stage his own one-artist exhibitions, which were no bar to patronage at the highest levels: his Mock Election went directly from the Egyptian Hall to the Royal Collection.54

49The chronically indebted Haydon, however, was not able to hold onto the profits of such triumphs, and the end of his career illustrates the vicious side of the ecosystem of exhibitions. In this extreme case, success or failure within this ecosystem was literally a matter of life or death. As financial pressures grew in the 1820s, Haydon took advantage of every possible venue, returning to exhibiting at the Institution and, with less frequency, at the Academy. His exploitation of multiple venues (along with the generosity of his friends and the patience of his creditors) kept him afloat for two full decades. But he also continued to take the entrepreneurial risk of staging his own exhibitions, and the failure of his display in 1846 undoubtedly contributed to his decision to take his own life. Here one can see the more destructive workings of an ecosystem, with two side-by-side attractions competing to the detriment of one. In the struggle to attract a limited resource—audience members—the human performer had prevailed over history paintings. The ecosystem could nurture and sustain artistic careers, but it could also destroy them.

As Haydon’s example demonstrates, both exhibition organizers and artists relied on another, equally vital, set of participants in the ecosystem of exhibitions: viewers. The nature of nineteenth-century art audiences represents one of the most exciting and most opaque topics in the study of past exhibitions. Audience numbers can be gauged from the stream of anonymous coins that viewers paid for admission to many nineteenth-century exhibitions. But these numbers say little about the respective social identities or the complex individual experiences of those viewers. Recent scholarship has moved beyond examining the hopes or preconceptions of exhibition planners about their audiences to studying how those audiences actually exploited a space, ignoring or refashioning the dictates of catalogue and exhibition layout.55 But much more remains to be done in this area.

55Despite important work on the topic, the social make-up of early nineteenth-century audiences is frequently mischaracterized, in part because of scholars’ tendency to impose present-day cultural hierarchies onto the displays of the past. For example, one author recently advocated for the importance of an early nineteenth-century display by asserting that it was “not a plebeian exhibition or commercial show”, but rather one with “a clear educational focus”.56 But displays in this period habitually combined commerce and education; it was, in fact, a key to their success. Similarly, in his discussion of the impetus behind the foundation of the National Gallery, London, in 1824, Brandon Taylor draws a firm line between displays of art and other attractions such as panoramas, asserting:

5657It was precisely the gap between the two available forms of public pleasure—the traditional aristocratic pleasure of beholding valuable paintings, and the delights of marvelling at the painted commercial illusions and street exotica—that must have been striking in late Hanoverian and early Victorian London.57

But this is a false binary: at the time, no strict distinction between “forms of public pleasure” existed. Rather, these cultural hierarchies were still emerging, and their boundaries had not yet hardened.58 Nor were the audiences for paintings and panoramas substantially different.59 The very fact that some commentators urged the organizers of art exhibitions to distinguish their events from other fashionable entertainments eloquently confirms that they were, in fact, entertainments.60

58More recently, scholars have begun to study in concert “categories of representation traditionally separated into spectacle and art”.61 As Jonathan Crary has shown, “paintings were produced and assumed meaning not in terms of some cloistered aesthetic and institutional domain, but as one of the many consumable and fleeting elements within the expanded field of images, commodities, and attractions.”62 The audience for these attractions was certainly stratified, but not by elite consumption of so-called fine art and lower-class consumption of other visual entertainments. Instead, participation in all of London’s public entertainments was strictly limited by their cost. In Paris, admission to the Salon was free, but at English exhibitions, a standard one-shilling fee excluded most members of the working classes, as it had originally been designed to do.63 Although the one-shilling charge has been described as “rather inconsequential”,64 it was in fact deeply consequential to those whose weekly wages were measured in shillings. In the first decades of the nineteenth century, even the best-paid members of the working classes, including skilled artisans such as carpenters working in London, made an estimated 25–40 shillings a week.65 In this period, radical publishers seeking a broad working-class audience priced their publications at one or two pence; a single admission to an exhibition cost six to twelve times that amount.66 Nonetheless, some journalists in the first decades of the nineteenth century continued to voice anxiety that the financial barriers to entry were not high enough.67 Some commentators also complained about less tutored (if relatively affluent) visitors to the regular exhibition days, accusing them of appreciating art for the wrong reasons, such as a simple-minded love of realistic detail.68

61Exhibition audiences were therefore limited by purchasing power, creating a restricted but still heterogeneous audience.69 Among those who could afford entry, a wide range of ranks were represented, from canal-owning dukes to prosperous cloth merchants. Nor should audience members be viewed in terms of their class status alone; also at work were affiliations of religion, gender, politics, economic interests, and aesthetic preferences.70 In 1845, John Scandrett Harford, an untitled but wealthy member of a Bristol banking family, wrote a letter to his wife about a Royal Academy dinner that reveals the subtle interplay of multiple social factors.71 The invitation-only event marked the opening of the Annual Exhibition and included a chance to view the display before dining.72 According to Harford, close examination of artworks was interspersed with socializing with people of various ranks and persuasions:

69I gave up between two and three hours to a view of the pictures, and was much assisted in discovering the gems among them, by Lord M[illeg] who had been I believe to the Private View the day before … The Bishop of London came up to me very cordially … he showed, while disavowing all pretences to Connoisseurship that he was a discriminating judge. Baily took me to look at a statue of his, a nymph from the Bath, the subject very delicately treated, and the

figure on all its parts so beautiful, elegant, and finely finished that I should class it, without hesitation, among the most successful works of modern art … then dear Acland joined me, introduced me to the Turner, a reddish-faced, rather short, [illeg]-looking man, with whom I had a long chat, and whom I treated with the deference due to highest genius—though some wld. say he has gone mad. [emphasis in the original].73

Harford’s account reveals the exhibition audience as diverse and subtly socially differentiated, even at this exclusive viewing. He encountered several acquaintances who outranked him on the social scale, including his close friend the baronet Sir Thomas Dyke Acland and an unidentified peer.74 A devoted Evangelical, Harford nonetheless found common interest in art with a High Church clergyman, the Bishop of London.75 Harford was also approached by an artist whom his family had patronized, Edward Hodges Baily, who successfully used the occasion to promote his sculpture. But for Harford, the most interesting social event was his introduction to J.M.W. Turner, by then an elder Academician known for his controversial formal innovations. Here the social calculations are complex indeed: Harford registers the artist’s working-class origins in his description of his rubicund complexion, only to claim to have inverted the usual social order by according Turner “the deference due to highest genius”.76 Yet Harford’s tone also suggests that he felt himself to be both acting with gracious condescension and demonstrating his own aesthetic acuity. Although hardly diverse by today’s standards, early nineteenth-century exhibitions were nonetheless complex social experiences in which visitors of different ranks, religious views, and professions could both encounter each other and distinguish themselves from each other.77

74Much more research remains to be done about the specific character of the audiences at each of London’s exhibition venues. But what is clear at this point is that those who could afford such entertainments visited many of them, moving among the various displays that made up the ecosystem of exhibitions. Artists did not limit themselves to one venue, nor did their audiences. Exhibitions were not consumed in isolation. Rather, they were part of a round of seasonal urban entertainments. Sometimes several displays were seen in the same day, interspersed with social calls, shopping, and performances. On a visit to London in 1811, in a single day, Jane Austen saw both an exhibition of contemporary art at the British Institution and a display of “curiosities”, including a taxidermy giraffe, at the Liverpool Museum.78 The contents of these two displays were more similar than might appear at first glance: the British Institution show included monumental works by artists such as West, but also numerous landscapes, genre scenes, and animal subjects, including Thomas Christopher Hofland’s Portrait of a Trout.79 Austen’s exhibition-going habits were typical for the time. In one month in summer 1812, the journalist Henry Crabb Robinson visited the Royal Academy, where he found Turner’s Hannibal Crossing the Alps “the most marvellous landscape I have ever seen”; he attended a lecture by Samuel Taylor Coleridge and a dramatic performance by Sarah Siddons; and went to see the radical publisher Daniel Isaac Eaton placed in the pillory. Tellingly, Robinson used the term exhibition to describe both the offerings at the Academy and public corporeal punishment.80

78This, then, was the ecosystem of exhibitions in 1820s London: a city filled with art exhibitions and other visual entertainments, whose organizers competed for attention, scrambled for places in desirable neighbourhoods, and synchronized their calendars in order to maximize their audience. Viewers from a range of social backgrounds, all of whom could afford the entry fees, chose among these offerings, often taking in multiple attractions within a day or within a season. Meanwhile, artists sought to find the best outlet for their works, tailoring their submissions to the available venues, mounting their own exhibitions, and manoeuvring for the best places within a show. Successfully navigating this ecosystem required talent, connections, training, wit, and no small amount of luck. Turning from a broad overview to a specific example, the next section examines the transit of a now-iconic work, John Constable’s The Hay Wain, through the ecosystem of exhibitions.

The Ecosystem of the Gallery: John Constable, John Martin, and Margaret Carpenter

In the context of a city, groups of exhibitions attracted viewers to certain districts through their collective presence, only then to compete for those viewers’ attention and resources. In the context of a single gallery, a similar dynamic took place among the objects exhibited. Each exhibition space functioned as an ecosystem within an ecosystem, like tidal pools within a larger coastal zone. The specific display conditions at each of these smaller, structurally distinct units of the ecosystem had important consequences for the reception of individual works. The perils of juxtaposition for artists of this period are well known. A brightly coloured or dramatically composed work could overshadow, or “kill”, its neighbours, and many commentators worried that the visually competitive settings of group exhibitions were driving artists to ever more extreme effects.81 But in addition to fuelling competition, the tightly packed walls could also have a generative effect. The dense hanging aesthetic of exhibitions in this period encouraged viewers to read the contents of displays in concert, savouring visual harmonies and contrasts, perceiving meaningful juxtapositions created by exhibition organizers, and generating vivid new narratives of their own.82 But for some artworks, it took several years and several different venues to find a favourable display environment.

81From today’s art-historical perspective, the most important event in London in 1821 was the exhibition at the Royal Academy of John Constable’s Landscape: Noon, now known as The Hay Wain (see fig. 1). This bucolic scene is today considered a quintessential work of the artist and of Romantic art. But at its public debut in 1821, The Hay Wain was overshadowed twice over: first, by a painting that captured the public imagination before the Academy even opened; and second, by other exhibits at the Academy. Identifying the works that shared the walls with this canonical painting sheds new light on nineteenth-century art, revealing works that competed for audience attention with Constable’s painting, and won. These include John Martin’s Belshazzar’s Feast, whose significance has recently been reassessed by scholars, and several works by Margaret Carpenter, whose paintings have yet to be seriously studied.83

83The failure of The Hay Wain to immediately capture the British public’s attention in 1821 has been used as evidence of that public’s lack of taste. For Andrew Hemingway, a survey of published criticism revealed a deficiency in nineteenth-century viewers. The public’s preference for works by John Martin and David Wilkie over The Hay Wain confirmed for this author that:

In this reading, the relative unpopularity of The Hay Wain indicates its original audience’s lack of sophistication; by contrast, the popularity of works by Martin and Wilkie suggests that they are straightforward and easily consumed. The terms of judgement being imposed here are those of a mid-twentieth-century art theory, that of avant-garde and kitsch.85 Recently, however, scholars have reassessed the work of both of these artists, exploring the nuanced social valences of Wilkie’s genre paintings and of Martin’s historical landscapes.86 I argue that the popularity of these works suggests not that their audiences were incapable of discernment, but that they valued a particular kind of looking, one fostered by the nineteenth-century ecosystem of exhibitions. This system encouraged modes of engagement that were different than, but not inherently inferior to, the modernist ideal of isolated aesthetic contemplation; instead, they were richly comparative, viewing works in concert with their companions.

85Such was the case with Martin’s Belshazzar’s Feast, exhibited at the British Institution’s annual sale exhibition of 1821, which opened in early spring (fig. 6). By the time The Hay Wain went on view at the Royal Academy later that season, Belshazzar’s Feast had already been declared the picture of the year.87 To understand why this painting was so popular, when Constable’s was not, we need to look both at its display context and at its visual qualities, according it the detailed formal analysis more usually reserved for canonical works.

87

Martin’s painting shows a party gone horribly wrong. In a vast outdoor courtyard, the Babylonian monarch Belshazzar and his court have been enjoying an impious feast served in sacred vessels looted from Jerusalem. Now all is consternation. A divine proclamation of doom, written in light, has appeared on the wall at left. The prophet Daniel, the man in black who presides at the centre of the picture, has just interpreted this portent: the king will die and his kingdom will fall. The myriad figures who respond to these events present an intricate catalogue of terror, pleading, and denial. Beyond them rise the legendary splendours of Babylon, including its hanging gardens. Throughout, the painting glistens, burns, and shimmers. The sharp yellow rays of the divine warning contrast with both the cool moonlight and the smouldering red glare of bonfires and torches. These variegated hues play across a richly ornamented scene, highlighting spiky diadems, sinuous silver vessels, and an outstretched serpent’s tongue. Martin’s composition invites the viewer both to savour this plenitude and to imagine its erasure: Babylon is resurrected only to fall once more.

Demand to see Martin’s work was so high that the British Institution sale exhibition was held open for several extra weeks. More than 33,000 visitors are known to have paid a shilling to see it, and the press of crowds necessitated a protective barrier.88 Why did this work capture the public imagination, while The Hay Wain did not? Recent attempts to rehabilitate Martin’s reputation have been grounded in his cultural significance, rather than in the aesthetic quality of his works.89 But it is worth asking what visual qualities in Martin’s compositions so appealed to London audiences. Part of the answer lies in the way in which this image was consumed. Its visual density and complexity reward sustained examination, carried out in conversation with the catalogue and with companions. Like earlier displays pioneered by Copley, this installation relied on “the interactions between image, text, and viewer”, with each viewer supplying his or her own cultural knowledge, in this case of the Biblical text and its possible interpretations in light of current events.90 The Biblical narrative, which would have been familiar to a large portion of the audience, is spread out over the surface of the composition, so that the viewer must survey the many figures in order to pick out the interpreting prophet and the disbelieving king.91 This painting rewards extended looking, and viewers spent considerable time in front of the painting, leading to complaints by reviewers that they could not even see the work they were meant to evaluate.92 One critic also claimed to have developed a personalized route through the exhibition, “first sitting before Mr. Martin’s ‘Belshazzar’s Feast’ whenever we visit the Gallery” and then proceeding to a nearby animal painting.93 In other words, viewing Martin’s canvas in its first exhibition setting could be a complex, interactive experience.

88

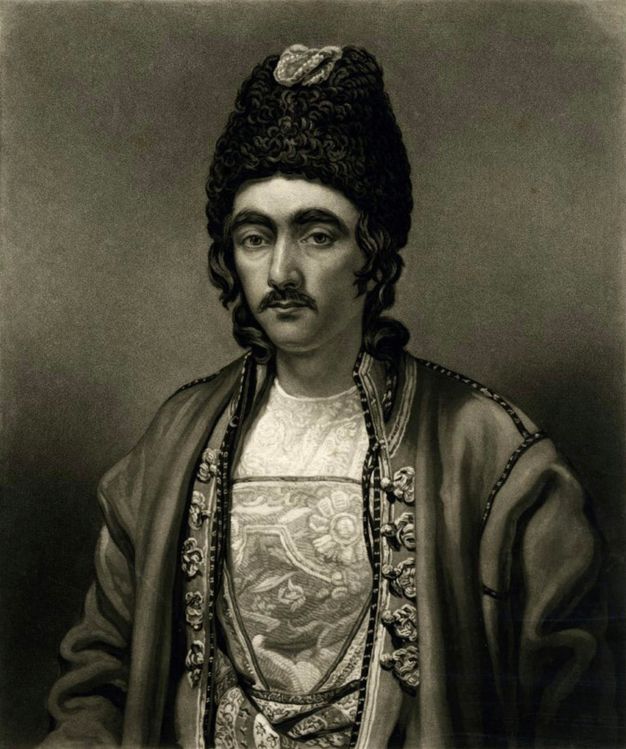

Information about this hang can be gleaned from the engraving published by the Magazine of the Fine Arts (fig. 7). Many images of exhibitions from this period adjust or even rearrange their contents, but the hang depicted here accords closely with the catalogue number order.94 Belshazzar’s Feast hung in the centre of a wall in the North Room, which was considered the principal gallery of the Institution.95 Martin’s painting served as the centrepiece of an intricately symmetrical hang—a type of installation commonly used in this era.96 This placement visually identified Martin’s painting as an important work. As the central object on the wall, it formed the anchor for a dense matrix of exhibits that contained numerous landscapes, including scenes of Italy, Spain, and the English countryside, as well as animal paintings, such as Thomas Christmas’s A Hunted Lion, which hung directly above it.97 This image would have complemented the exoticism of Martin’s canvas, as would a highly charged set of pendants that flanked it. On the left hung John J. Halls’ Meerza Jiâfer Tabeeb, a portrait of a Persian medical student (fig. 8); on the right, Margaret Carpenter’s A Native of Calcutta.98 Although little known today, Carpenter was a frequent exhibitor in London. Her Native of Calcutta has yet to be located, but its visual symmetry with its temporary pendant can be seen in the engraving: both present tightly framed three-quarter views of single figures wearing elaborate headgear. It seems unlikely that these two images of foreigners ended up to either side of Martin’s canvas by chance, especially given how few such images there were in the exhibition as a whole. One of the sites invoked though these temporary pendants, Calcutta, was a long-established nexus of imperial expansion. The other, Persia, was a country in which the British had only recently established a diplomatic presence, in the hope of countering Russian influence in the region. By juxtaposing these likenesses with Martin’s image of ancient Babylon, the British Institution administrators performed a classic Orientalist manoeuvre, conflating distance in space with distance in time. The presence of these two additional foreign faces would have highlighted Martin’s emphasis on the exotic setting, which the writer for the Literary Chronicle described as an “appalling and super-human amplitude of Eastern gorgeousness”.99 Combined with images of men from colonial territories, both actual and desired, Martin’s painting may also have invoked a sense of imperial destiny.

94

Prominent placement within a group show helped Martin’s canvas thrive within the ecosystem of exhibitions. Display circumstances in this year were less beneficial for Constable’s The Hay Wain, which faced stiff competition from both within and without the Academy Exhibition. Even after the sale exhibition at the British Institution had closed, Belshazzar’s Feast continued to compete with the Academy’s exhibits, because the picture’s new owner put it on display as a paying attraction, first on the Strand and later on Pall Mall.100 Moreover, The Hay Wain was not among the most favourably reviewed works at the Academy, although it did attract positive notice in both the Observer and the Examiner.101 The critical favourites in 1821 tended to be figure paintings, such as William Hilton’s Nature Blowing Bubbles, which garnered considerable praise (fig. 9). A rare dissenting voice in the London Magazine complained: “I don’t see why a fine plump young woman, lying under the shade of ardent sunflowers … and idly busied in bubbling water through a reed, should be dignified with the abstract title of Nature”.102 But the vast majority of critics agreed with Robert Hunt, who declared in the Examiner that “this noble picture unites the simplicity of Nature with Allegory, the seriousness of moral instruction and satire with the charms of female and infantine beauty … It will equally delight the mother, the artist, and the philosopher”.103 Hilton’s picture no doubt benefited from its location within the exhibition, hung above the fireplace in the Great Room.104 Location may likewise have contributed to the lacklustre reception of The Hay Wain: it was placed in the much smaller, adjoining School Room.105 But a spot in the School Room did not necessarily spell doom: another work hanging there, William Etty’s Cleopatra’s Arrival in Cilicia, managed to attract considerable critical attention (fig. 10). This brightly toned, action-packed composition made Etty’s reputation; “I awoke famous”, he later recalled.106 Among the critics, Etty’s Cleopatra was received as an elevated work of art, due to its attention to the body, classical subject matter, and visual references to continental masters such as Veronese and Rubens. One reviewer described Etty’s painting as a “splendid achievement” in “the highest class”, while simply noting in passing that in the same room “there are many good landscapes”.107 At the British Institution earlier that season, the installation had promoted the importance of Martin’s painting, awarding it a central place and surrounding it with companions that encouraged an imperialist reading of the work. For The Hay Wain at the Academy, however, the presentation was not as advantageous, nor were the companions as congenial.

100

At the end of the Academy Exhibition of 1821, Constable was left without a purchaser for The Hay Wain. Fortunately for the artist, the early nineteenth-century ecosystem of exhibitions provided a multiplicity of venues. In 1822, when he sent it to the British Institution sale exhibition, the critical reception was much the same: reviewers devoted more column space to landscapes by artists little known today, such as Thomas Christopher Hofland and William Linton. The circumstances of its display may once again partially explain this neglect. The Hay Wain was shown on the west side of the Middle Room, where viewers entered through a central stair.108 Although it was one of the larger paintings hanging on this wall, it was in boisterous company. Remarkably, its companion from the School Room at the Academy in the previous year, Etty’s Cleopatra, appeared aside it once more.109 Etty’s Cleopatra hung to the right of a large work that must have dominated the wall, Mary Anne Ansley’s 7 × 9.5 foot Miltonic subject, Satan Bourne Back to His Chariot after Having Been Wounded by the Arch Angel Michael (currently unlocated).110 The Hay Wain was hung to the left of this massive work, physically and likely visually dwarfed by it. At roughly 4 × 6 feet, Constable’s canvas was large for a landscape of this period, but Ansley’s history painting was even larger.

108

On the same wall, also to the left of Ansley’s monumental canvas, hung a smaller work, Devotion, painted by Margaret Carpenter, whose portrait of an Indian man had hung next to Martin’s Belshazzar’s Feast in the same space the year before (fig. 11). Carpenter’s career is emblematic of the myriad artists who operated in the ecosystem of exhibitions without the benefit of academic training, but with the help of multiple exhibition venues.111 The daughter of an army officer, she grew up in Salisbury, where her interest in art was encouraged by the second Earl of Radnor, who gave her access to his important collection of Old Master paintings at Longford Castle.112 Once established in London, she built a substantial career as a painter of portraits and subject pictures. She showed regularly at the British Institution and the Royal Academy, as well as contributing to the Paris Salon of 1827, where her exhibit won praise from Delacroix.113 As the prevalence of her work in exhibitions of the 1820s suggests, she was a fixture of the early nineteenth-century art world, and it was said that she “would certainly have been a Royal Academician but for her sex.”114 Although well known to critics and to her fellow artists at the time, Margaret Carpenter remains almost invisible to art history today, in part because she was neither a member of the Academy nor one of its vocal opponents.

111

Her exhibit at the British Institution in 1822, Devotion, is at first glance an inexplicable and untimely work, one that defies the standard developmental models of art history. It is an intense study of a single figure looking heavenward, in the mode of Counter-Reformation depictions of saints.115 The lush, varied brushwork attests to Carpenter’s technical mastery: the contours of the saint’s face are firmly handled, while his collar is merely indicated by two emphatic white streaks of paint (fig. 12). Carpenter’s picture is striking both as a frankly admiring image of an attractive man by a female artist and as an example of traditionally Catholic iconography produced in a Protestant nation. Just a year earlier a Catholic relief bill, which would have eased restrictions on Catholic male citizens’ participation in government, had passed the House of Commons only to be rejected by the Lords.

115Within the context of the British Institution, however, Carpenter’s apparently anachronistic subject matter made perfect sense: many of the patrons of the British Institution believed that study of continental models was essential for the improvement of British art. Reviewers of the exhibition remained silent about the religious implications of Carpenter’s Devotion, while praising its formal qualities; one critic went so far as to declare that it “wants nothing but the touch of time to rank it with some of the best specimens of the Italian Masters”.116 This accolade exemplifies the comparative mode of viewing enabled by the ecosystem of exhibitions, whose simultaneous displays had the effect, in the words of one critic, of “bringing the works of the ancient and modern Artists into immediate comparison”.117 Seen in this light, Carpenter’s picture represents not an object out of step with its art-historical moment, but one successfully matched with its original exhibition venue by an artist skilled at navigating the ecosystem of exhibitions.

116Carpenter’s Devotion soon found a buyer and eventually entered the collection of John Sheepshanks, who, in 1857, included it in his important gift of British paintings to the nation.118 Its companion, The Hay Wain, had also attracted some critical notice, but at the end of the exhibition, Constable had yet to find a buyer who would meet his asking price. But the display of the work at the British Institution nonetheless enabled its future fame, because it had been seen there by a French art dealer of English extraction, John Arrowsmith, who wanted the picture “to form part of an exhibition in Paris—to show them the nature of the English art”.119 Although Constable found his initial offer insultingly low, negotiations continued, as the artist was also sensible of the possibilities: “I hardly know what to do—it may promote my fame & procure commissions but it may not.”120 He also had to overcome his jingoistic prejudices, less than a decade after Waterloo, declaring at one point that “It is too bad to allow myself to be knocked down by a French man.” Eventually, however, a deal was reached, and Arrowsmith arranged for three of Constable’s works to be shown at the Paris Salon of 1824. This time, they were not overlooked, thanks in no small part to the efforts of their new owner. Arrowsmith drummed up enthusiasm for Constable’s works prior to the opening of the Salon by making them available in his rooms. There, they could be studied up close, at length, and with fewer competitors—an opportunity taken by Delacroix, among others.121 This promotion in a smaller display venue set the stage for the works’ acknowledgement at the official exhibition. Although Constable’s canvases were not originally well placed at the Salon, interest was such that The Hay Wain and one other work were moved, after the exhibition opened, to what Constable described as “a post of honour … two prime places near the line in the principal room”.122 Clearly, Arrowsmith’s advocacy had a beneficial effect. The result is well known: fame and influence for Constable in France and an elevated reputation at home.123 The Hay Wain was sought for the French national collections, but sold elsewhere, and eventually was accessioned by the National Gallery, London, where it has become an icon of national identity.

118***

In 1848, a young woman from Manchester named Mary Joanna Hutchinson wrote to her brother, a cotton mill owner, describing a visit to London. Her itinerary was typically crowded: she walked on Hampstead Heath with her uncle on one day and on another, she wrote, “I went with him to the British Institution, there are some very fine pictures in it this year. Then Mary & I went to see a Panorama of Vienna, that too is very beautiful. … I have also been gratified by a sight of the Duke of Wellington”.124 At the end of the period under consideration here, art exhibitions, panoramas, and celebrities could still be treated as comparable urban attractions. For Hutchinson, both a gathering of hundreds of contemporary artworks and a single massive, illusionistic painting of foreign city were urban display experiences to be judged in concert—and she found both to be “very beautiful”. This type of viewing is typical of the ecosystem of exhibitions in nineteenth-century London. As this article has sought to demonstrate, our approach to writing the history of this period should be similarly expansive.

124The ecosystem of exhibitions challenges scholars to consider many participants at a particular moment of visual production, not just the traditionally prestigious or immediately charismatic. Starting with an installation rather than with a particular artist or set of artists provides a fresh perspective on nineteenth-century art. This model does not dispense with hierarchy altogether—as in a biological ecosystem, there are more and less successful actors. But it encourages a broader scope for research. Constable’s importance to the history of art is unquestioned. But, as the objects discussed above demonstrate, his was not the only work of significant interest or merit to be shown in London in these years. Nineteenth-century exhibitions and exhibits should be studied as they were consumed, in combination with one another. It is insights such as this that the history of exhibitions has to offer the history of art.

Acknowledgements

This essay draws on research for a book manuscript, “The Shadow Museum: A History of the British Institution, 1805–1867”, supported by an National Endowment for the Humanities Long-Term Fellowship at the Huntington Library. Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this essay do not necessarily reflect those of the National Endowment for the Humanities. Earlier versions of this project were presented at “A Year’s Art: The Royal Academy Summer Exhibition, 1769–2016”, at the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art and “London: Capital of the Nineteenth Century”, at the College Art Association, both in 2016. For their comments, many thanks to Leah Astbury, Tim Barringer, Jordan Bear, Janice Carlisle, Josh Chafetz, Richard Godbeer, Jason Rosenfeld, Paris Spies-Gans, the members of the Virginia Commonwealth University Humanities Research Center’s Premodern Society and Culture Reading Group, and, especially, the editors of and the anonymous reviewers for this journal.

About the author

-

Catherine Roach is an Associate Professor of Art History at Virginia Commonwealth University. She is the author of Pictures-Within-Pictures in Nineteenth-Century Britain, which received the Historians of British Art Book Award for Exemplary Scholarship on the Period after 1800. She was awarded a National Endowment for the Humanities Fellowship at the Huntington Library to support work on her second book, a history of the ground-breaking nineteenth-century exhibition society, the British Institution.

Footnotes

-

1

P. Chaussard, Sur Le Tableau des Sabines, par David (Paris: Charles Pougens, 1800), 1; Fredérique Debuissons, “A Ruin: Jacques-Louis David’s Sabine Women”, Art History 20, no. 3 (September 1997): 432–433. ↩︎

-

2

Elizabeth Gilmore Holt (ed.), The Art of All Nations, 1850–1873: The Emerging Role of Exhibitions and Critics (Garden City: Anchor Books, 1981), 157; Patricia Mainardi, “Courbet’s Exhibitionism”, Gazette des Beaux-Arts, no. 118 (December 1991): 253–265. ↩︎

-

3

Emily Ballew Neff, “The History Theatre: Production and Spectatorship in Copley’s The Death of Major Peirson”, in Emily Ballew Neff (ed.), John Singleton Copley in England (Houston, TX: Museum of Fine Arts, 1995), 61–74; Konstantinos Stefanis, “Nathaniel Hone’s 1775 Exhibition: The First Single-Artist Retrospective”, in Andrew Graciano (ed.), Exhibiting Outside the Academy, Salon and Biennial, 1775–1999: Alternative Venues for Display (Farnham: Ashgate, 2015), 13–36. ↩︎

-

4

Patrick Noon, “Prologue”, in Patrick Noon (ed.), Constable to Delacroix: British Art and the French Romantics (London: Tate Publishing, 2003), 10; Rosie Dias, “‘A World of Pictures’: Pall Mall and the Topography of Display, 1780–99”, in Miles Ogborn and Charles W.J. Withers (eds.), Georgian Geographies: Essays on Space, Place and Landscape in the Eighteenth Century (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2004), 97. ↩︎

-

5

Jonathan Crary, “Géricault, the Panorama, and Sites of Reality in the Early Nineteenth Century”, Grey Room no. 2 (Fall 2002): 5–25; Christine Riding, “Staging The Raft of the Medusa”, Visual Culture in Britain 5 (2004): 1–26; Dias, “‘A World of Pictures’”; Sadiah Qureshi, Peoples on Parade: Exhibitions, Empire, and Anthropology in Nineteenth-Century Britain (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2011); Pamela Fletcher and Anne Helmreich, “Local/Global: Mapping Nineteenth-Century London’s Art Market”, Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 11, no. 3 (Autumn 2012), http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/autumn12/fletcher-helmreich-mapping-the-london-art-market; John Plunkett, “Moving Panoramas c. 1800 to 1840: The Spaces of Nineteenth-Century Picture-Going”, 19: Interdisciplinary Studies in the Long Nineteenth Century 17 (2013), DOI:10.16995/ntn.674; Eleanor Hughes, “Sanguinary Engagements: Exhibiting the Naval Battles of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars”, in John McAleer and John M. MacKenzie (eds.), Exhibiting the Empire: Cultures of Display and the British Empire (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2015), 90–110; Ann Bermingham, “Technologies of Illusion: De Loutherbourg’s Eidophusikon in Eighteenth-Century London”, Art History 39, no. 2 (April 2016): 376–399; Gillian Russell, “Reality Effects: War, Theater and Re-enactment Around 1800”, in Satish Padiyar, Philip Shaw, and Philippa Simpson (eds.), Visual Culture and the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars (London: Routledge, 2016), 169–182; Martina Droth and Michael Hatt, “The Greek Slave by Hiram Powers: A Transatlantic Object”, Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 15, no. 2 (Summer 2016), http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/summer16/droth-hatt-intro-to-the-greek-slave-by-hiram-powers-a-transatlantic-object; Mark Hallett, Sarah Victoria Turner, and Jessica Feather (eds.), The Royal Academy of Arts Summer Exhibition: A Chronicle, 1769–2018 (London: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, 2018), https://chronicle250.com. ↩︎

-

6

For a corrective approach, see Paul Barlow, “Fear and Loathing of the Academic, or Just What is it that Makes the Avant-Garde so Different, so Appealing?”, in Rafael Cardoso Denis and Colin Trodd (eds.), Art and the Academy in the Nineteenth Century (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2000), 15–32; for the persistence of this model see, for example, Andrew Graciano (ed.), Exhibiting Outside the Academy, Salon and Biennial, 1775–1999: Alternative Venues for Display (Farnham: Ashgate, 2015), 4. In addition, a recent publication that rejects this binary for artists nonetheless describes other exhibition societies as “alternatives” or “rivals”; see Sarah Monks, “Life Study: Living with the Royal Academy, 1768–1848”, in Sarah Monks, John Barrell, and Mark Hallett (eds.), Living with the Royal Academy: Artistic Ideals and Experiences, 1768–1848 (Farnham: Ashgate, 2013), 1–3. ↩︎

-

7

Arthur George Tansley, “The Use and Abuse of Vegetational Concepts and Terms”, Ecology 16, no. 3 (July 1935), 299. ↩︎

-

8

Laura Cameron and Sinead Early, “The Ecosystem—Movements, Connections, Tensions and Translations”, Geoforum 65 (October 2015), 473. A recent article deploys a related term, ecology (in this case borrowed from psychology rather than biology) to characterize the relationship between art exhibitions and their urban environment, but does not consider relationships among exhibitions. See Dell Upton, “The Urban Ecology of Art in Antebellum New York”, in Andrew Hemingway and Alan Wallach (eds.), Transatlantic Romanticism: British and American Art and Literature, 1790–1860 (Boston, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2015), 49–66. ↩︎

-

9

Tansley, “The Use and Abuse of Vegetational Concepts and Terms”, 301. ↩︎

-

10

Richard D. Altick, The Shows of London (Boston, MA: Belknap Press, 1978), 426. ↩︎

-

11

Linda Nochlin, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?”, in Women, Art and Power and Other Essays (New York: Harper & Row, 1988), 153. ↩︎

-

12

Tony Bennett, “The Exhibitionary Complex”, New Formations, no. 4 (Spring 1988), 76, 82. ↩︎

-

13

Colin Trodd, “The Discipline of Pleasure; or, How Art History Looks at the Art Museum”, Museum and Society 1, no. 1 (2003), 21, 27, https://journals.le.ac.uk/ojs1/index.php/mas/article/view/11; Tim Barringer, “Victorian Culture and the Museum: Before and After the White Cube”, Journal of Victorian Culture 11, no. 1 (January 2006), 138, DOI:10.3366/jvc.2006.11.1.133. ↩︎

-

14

David H. Solkin, “‘This Great Mart of Genius’: The Royal Academy Exhibitions at Somerset House, 1780–1836”, in David H. Solkin (ed.), Art on The Line: The Royal Academy Exhibitions at Somerset House, 1780–1836, ed. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2001), 5–8; Helen Rees Leahy, “‘Walking for Pleasure’? Bodies of Display at the Manchester Art-Treasures Exhibition in 1857”, Art History 30, no. 4 (2007): 545–660; Catherine Flood, “‘And Wot does the Catlog Tell Me?’ Some Social Meanings of Nineteenth-Century Catalogues and Gallery Guides”, 19: Interdisciplinary Studies in the Long Nineteenth Century 5 (2007), DOI:10.16995/ntn.461. ↩︎

-

15

Alexander Geppert, Fleeting Cities: Imperial Expositions in Fin-de-Siècle Europe (Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), 4. ↩︎

-

16

A full survey would also include groups such as journalists, editors, publishers, auctioneers, art dealers, artists’ suppliers, frame-makers, and porters and other working-class individuals hired to police exhibitions. On auction houses’ interactions with each other and with exhibition societies, see Matthew Lincoln and Abram Fox, “The Temporal Dimensions of the London Art Auction, 1780–1835”, British Art Studies 4 (Autumn 2016): DOI:10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-04/afox-mlincoln. ↩︎

-

17

For a recent example of such an approach, see Darcy Grimaldo Grigsby, “Still Thinking about Olympia’s Maid”, Art Bulletin 97, no. 4 (2015): 430–451. ↩︎

-

18

On the development of comparative viewing in the eighteenth century, see Andrew McClellan, Inventing the Louvre: Art, Politics, and the Origins of the Modern Museum in Eighteenth-Century Paris (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 3; Holger Hoock, “‘Struggling against a Vulgar Prejudice’: Patriotism and the Collecting of British Art at the Turn of the Nineteenth Century”, Journal of British Studies 49, no. 3 (July 2010): 585–588; Carole Paul (ed.), The First Modern Museums of Art: The Birth of an Institution in 18th- and Early-19th-Century Europe (Los Angeles, CA: Getty, 2012), xiv. ↩︎

-

19

Robert Hunt, “Fine Arts: The Royal Academy Exhibition”, Examiner, 17 June 1821, 380. ↩︎

-

20

John Bonehill, “Laying Siege to the Royal Academy: Wright of Derby’s View of Gibraltar at Robins’s Rooms, Covent Garden, 1785”, Art History 30, no. 4 (September 2007), 541; Mark Hallett, “Reading the Walls: Pictorial Dialogue at the Eighteenth-Century Royal Academy”, Eighteenth-Century Studies 37, no. 4 (2004): 597–602; Eleanor Hughes, “Ships of the ‘Line’: Marine Paintings at the Royal Academy Exhibition of 1784”, in Timothy Barringer, Geoffrey Quilley, and Douglas Fordham (eds.), Art and the British Empire (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2007), 139–152; Pamela Fletcher, “1859: Sequel Paintings,” in Mark Hallett, Sarah Victoria Turner, and Jessica Feather (eds.), The Royal Academy of Arts Summer Exhibition: A Chronicle, 1769–2018 (London: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, 2018), https://chronicle250.com/1859. ↩︎

-

21

Jason Rosenfeld, “Absent of Reference: New Languages of Nature in the Critical Responses to Pre-Raphaelite Landscapes”, in Michaela Giebelhausen and Tim Barringer (eds.), Writing the Pre-Raphaelites: Text, Context, Subtext (Farnham: Ashgate, 2009), 151–170; Catherine Roach, Pictures-Within-Pictures in Nineteenth-Century Britain (London: Routledge, 2016), 1–23. ↩︎

-

22

See, for example, “Fine Arts”, New Monthly Magazine, 1 July 1821, 334. ↩︎

-

23

“Fine Arts”, New Monthly Magazine, 1 June 1821, 282. ↩︎

-

24

Susan M. Pearce, “Giovanni Battista Belzoni’s Exhibition of the Reconstructed Tomb of Pharaoh Seti I in 1821”, Journal of the History of Collections 12, no. 1 (2000): 109–125. ↩︎

-

25

Altick, The Shows of London, 99–116, 408–415; Oskar Bätschmann, The Artist in the Modern World: The Conflict Between Market and Self-Expression (Cologne: DuMont Buchverlag, 1997), 29–52; Giles Waterfield, “The Town House as Gallery of Art”, London Journal 20, no. 1 (1995): 47–66; Anne Nellis Richter, “Improving Public Taste in the Private Interior: Gentlemen’s Galleries in Post-Napoleonic London”, in Denise Amy Baxter and Meredith Martin (eds.), Architectural Space in Eighteenth-Century Europe: Constructing Identities and Interiors (London: Routledge, 2010), 169–186. ↩︎

-

26

These include the Society of Painters in Water Colours (1804), the British Institution (1805), the Associated Artists in Watercolour (1808), Society of Painters in Oil and Water Colours (1814), and the Society of British Artists (1823). See, also, Peter Funnell, “The London Art World and its Institutions”, in Celina Fox (ed.), London: World City, 1800–1840 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1992), 155–166. ↩︎

-

27

Andrew Hemingway, Landscape Imagery and Urban Culture in Early Nineteenth-Century Britain (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), 35; Pamela Fletcher, “Shopping for Art: The Rise of the Commercial Art Gallery, 1850s–90s”, in Pamela Fletcher and Anne Helmreich (eds.), The Rise of the Modern Art Market in London, 1850–1939 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2011), 47–64. ↩︎

-

28

On the British Institution, see Peter Fullerton, “Patronage and Pedagogy: The British Institution in the Early Nineteenth Century”, Art History 5, no. 1 (March 1982): 59–72; Ann Pullan, “Public Goods or Private Interests? The British Institution in the Early Nineteenth Century”, in Andrew Hemingway and William Vaughan (eds.), Art in Bourgeois Society, 1790–1850 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 27–44; Nicholas Tromans, “Museum or Market? The British Institution”, in Paul Barlow and Colin Trodd (eds.), Governing Cultures: Art Institutions in Victorian London (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2000), 44–55; and Roach, Pictures-Within-Pictures in Nineteenth-Century Britain, 24–63. ↩︎

-

29

Susan Pearce, “William Bullock: Collections and Exhibitions at the Egyptian Hall, London, 1816–25”, Journal of the History of Collections 20, no. 1 (2008): 17–35. ↩︎

-

30

See, for example, Droth and Hatt, “The Greek Slave by Hiram Powers”; Tanya Pohrt, “The Greek Slave on Tour in America”, Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 15, no. 2 (Summer 2016), http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/summer16/pohrt-on-the-greek-slave-on-tour-in-america. ↩︎

-

31

Dias, “‘A World of Pictures’”, 92–113; Fletcher and Helmreich, “Local/Global”; see, also, Hannah Williams, “Artists’ Studios in Paris: Digitally Mapping the 18th-Century Art World”, Journal18 5 (Spring 2018), DOI:10.30610/5.2018.1. ↩︎

-

32

Altick, The Shows of London, 405. ↩︎

-

33

Anne Koval, “The ‘Artists’ Have Come out and the ‘British’ Remain: The Whistler Faction at the Society of British Artists”, in Elizabeth Prettejohn (ed.), After the Pre-Raphaelites: Art and Aestheticism in Victorian England (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1999), 90. ↩︎

-

34

Hesketh Hubbard, An Outline History of the Royal Society of British Artists (London: Royal Society of British Artists, 1937), Vol. 1, 28. ↩︎

-

35

Fullerton, “Patronage and Pedagogy”, 67; Timothy Wilcox, The Triumph of Watercolour: The Early Years of the Royal Watercolour Society, 1805–55 (London: Philip Wilson Publishers, 2005), 24. ↩︎

-

36

Joseph Farington, Kathryn Cave (ed.), The Diary of Joseph Farington (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1978), Vol. 12, 4272. ↩︎

-

37

Hubbard, An Outline History of the Royal Society of British Artists, Vol. 1, 31. ↩︎

-

38

Thomas Philips to Dawson Turner, 2 May 1824, Dawson Turner Papers, 0.13.27, Trinity College, Cambridge. ↩︎

-

39

Greg Smith, The Emergence of the Professional Watercolourist: Contentions and Alliances in the Artistic Domain, 1760–1824 (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2002), 159; Wilcox, The Triumph of Watercolour, 64. ↩︎

-

40

“British Institution”, Bell’s Life in London, 28 January 1827, 1. ↩︎

-

41

William T. Whitley, Art In England (New York: Hacker Books, 1973), Vol. 1, 289; Fullerton, “Patronage and Pedagogy”, 67. ↩︎

-

42

Stefanis, “Nathaniel Hone’s 1775 Exhibition”. ↩︎

-

43

Laura Auricchio, “Pahin de la Blancherie’s Commercial Cabinet of Curiosity (1779–87)”, Eighteenth-Century Studies 36, no. 1 (2002): 47–61; Francis Haskell, The Ephemeral Museum: Old Master Paintings and the Rise of the Art Exhibition (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2000), 16–19, 46–63; Catherine Roach, “Rehanging Reynolds at the British Institution: Methods for Reconstructing Ephemeral Displays”, British Art Studies, Issue 4 (Autumn 2016): DOI:10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-04/croach. ↩︎

-

44

Neff, “The History Theatre”. ↩︎

-

45

Paul Mattick, “Art and Money”, in Paul Mattick (ed.), Eighteenth-Century Aesthetics and the Reconstruction of Art (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 167. ↩︎

-

46

Algernon Graves, The Royal Academy of Arts: A Complete Dictionary of Contributors and their Work from its Foundation in 1769 to 1904 (London: Graves & Co., 1906), Vol. 8, 267; Algernon Graves, The British Institution, 1806–1867: A Complete Dictionary of Contributors and Their Work from the Foundation of the Institution (Bath: Kingsmead Reprints, 1969), 579. See, also Michael Clark and Nicholas Penny (eds.), The Arrogant Connoisseur: Richard Payne Knight, 1751–1824 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1982), 107; Nicholas Tromans (ed.), David Wilkie, 1785–1841: Painter of Everyday Life (London: Dulwich Picture Gallery, 2002), 62. ↩︎

-

47

For these works, see Helmut von Effra and Allen Staley, The Paintings of Benjamin West (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1986), 358–360. West may have been emulating David Wilkie, who in 1812 showed the sketch of the Village Holiday at the Academy, and the full-scale oil in his own exhibition. Tromans, David Wilkie, 1785–1841, 19. ↩︎

-

48

“Fine Arts: Royal Exhibition, Somerset House”, Belle Assemblée, August 1815, 39. ↩︎

-

49

On the complex factors that contributed to Haydon’s suicide, see John Barrell, “Benjamin Robert Haydon: The Curtius of the Khyber Pass”, in John Barrell (ed.), Paintings and the Politics of Culture: New Essays on British Art, 1700–1850 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992), 270. ↩︎

-

50

See, for example, David Blayney Brown, “‘Fire and Clay’—Benjamin Robert Haydon, Historical Painter”, in David Blayney Brown, Robert Woof, and Stephen Hebron (eds.), Benjamin Robert Haydon, 1786–1846: Painter and Writer, Friend of Wordsworth and Keats (Grasmere: Wordsworth Trust, 1999), 14; David Higgins, Romantic Genius and the Literary Magazine: Biography, Celebrity, and Politics (London: Routledge, 2005), 127. ↩︎

-

51

Graves, The Royal Academy of Arts, Vol. 4, 36; Graves, The British Institution, 1806–1867, 251. ↩︎

-

52

Brown, “‘Fire and Clay’”, 10. ↩︎

-

53

Higgins, Romantic Genius and the Literary Magazine, 140. ↩︎

-

54

Brown, “‘Fire and Clay’”, 16. ↩︎

-

55

Flood, “‘And Wot does the Catlog Tell Me?’”; Leahy, “‘Walking for Pleasure’?”; Helen Rees Leahy, Museum Bodies: The Politics and Practices of Visiting and Viewing (Farnham: Ashgate, 2012); Aileen Fyfe, “Reading Natural History at the British Museum and the Pictorial Museum”, in Aileen Fyfe and Bernard Lightman (eds.), Science in the Marketplace: Nineteenth-Century Sites and Experiences (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2007), 196–230; Mark Hallett, Sarah Victoria Turner, and Jessica Feather (eds.), The Great Spectacle: 250 Years of the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 2018). ↩︎

-

56

Richard Gillespie, “Richard Du Bourg’s ‘Classical Exhibition’, 1775–1819”, Journal of the History of Collections 29, no. 2 (July 2017) 251–269, DOI:10.1093/jhc/fhw026. ↩︎

-

57

Brandon Taylor, Art for the Nation: Exhibitions and the London Public, 1747–2001 (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1999), 33. ↩︎

-

58

Martin Myrone (ed.), John Martin: Apocalypse (London: Tate Publishing, 2011), 12. ↩︎

-

59

Riding, “Staging The Raft of the Medusa”, 3–5. ↩︎

-

60

Hemingway, Landscape Imagery and Urban Culture in Early Nineteenth-Century Britain, 5. ↩︎

-

61

Hughes, “Sanguinary Engagements”, 93. ↩︎

-

62

Crary, “Géricault, the Panorama, and Sites of Reality in the Early Nineteenth Century”, 13. ↩︎

-

63

Giles Waterfield (ed.), Palaces of Art: Art Galleries in Britain, 1790–1990 (London: Dulwich Picture Gallery, 1991), 131; C.S. Matheson, “‘A Shilling Well Laid Out’: The Royal Academy’s Early Public”, in David H. Solkin (ed.), Art on The Line: The Royal Academy Exhibitions at Somerset House, 1780–1836 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2001), 40; for a provocative theory of how publicity efforts enabled “consumption without attendance”, see Qureshi, Peoples on Parade, 47. ↩︎

-

64

Holger Hoock, The King’s Artists: The Royal Academy of Art and the Politics of British Culture, 1760–1840 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2003), 207. ↩︎

-

65

Peter Mathias, The First Industrial Nation: An Economic History of Britain, 1700–1914 (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1969), 219. ↩︎

-

66

Richard Altick, The English Common Reader: A Social History of the Mass Reading Public, 1800–1900 (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1957), 266; in the 1830s, the Mechanics’ Institute exhibitions charged a lower admission fee of half a shilling, which made them accessible to “artisans and mechanics”, but not to most “ordinary factory workers or labourers”, see Toshio Kusamitsu, “Great Exhibitions Before 1851”, History Workshop 9 (Spring 1980), 74. ↩︎

-

67

Neff, “The History Theatre”, 74. ↩︎

-

68

Hemingway, Landscape Imagery and Urban Culture in Early Nineteenth-Century Britain, 5; David H. Solkin, “Crowds and Connoisseurs: Looking at Genre Painting at Somerset House”, in David H. Solkin (ed.), Art on The Line: The Royal Academy Exhibitions at Somerset House, 1780–1836 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2001), 169–171. ↩︎

-

69

Hemingway, Landscape Imagery and Urban Culture in Early Nineteenth-Century Britain, 4. ↩︎

-

70

Marjorie Morgan, Manners, Morals and Class in England, 1774–1858 (London: St. Martin’s Press, 1994), 5–6. ↩︎

-

71