Climate and Culture Beyond Borders

Climate and Culture Beyond Borders

By Worm: art + ecology

With this British Art Studies feature, which responds to the theme of “British Art and Natural Forces” proposed by the journal’s editors, I bring together four artistic practices alongside my own.1 They highlight diverse activities among international, socially engaged, creative practices that relate to the core conversations on justice in environmental and climate issues. I encourage us to narrate British artistic engagements with nature through our long-existing and under-represented creative activisms, across geographies and from multiple perspectives of climate justice.

1British Arts in 2020

Over a decade of austerity policies, the creative climate in the UK has been weathered by relentless state budget cuts to creative education, artistic development, cultural production, and their public arts engagements. It has led to the commercialisation of our arts and higher education institutions, rather than nationalising them for more stable and inclusive public accessibility. But the arts sector is not an isolated sector to have its public purse pinched. Austerity cuts to welfare continue to disintegrate the NHS and state education, and aggravate food and housing injustices, just to name a few immeasurable manifestations of the growing economic disparities in Britain.

The Culture of Britishness

What does this have to do with our conversation on British arts and climate change? I’ll firstly problematise the “British” in our British arts, in the current political context of Brexit, the international rise in right-wing nationalisms, and the accelerated injustices as a result of the global health crisis—all of which intersect with climate politics. The UK government is now weaponising the British arts sector to expedite the growing public animosity towards racialised people, exemplified by the state’s overtly racist motives behind its Hostile Environment policies and the Windrush scandal, to enforce the widespread, violent, anti-immigrant hate; and the policing and deportation of racialised people. It also comes in the form of the government’s economic recovery plan for the cultural sector as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, which itself is disproportionately killing racialised and systemically marginalised people in the UK. Specifically, it is the Conservative government’s former “Festival of Brexit” plan, now rebranded with the working title Festival UK 2022.2 The festival is a nationwide “open, original, optimistic” presentation of “UK creativity and innovation” to celebrate post-Brexit British nationalism, while UK border policy remains firmly anti-immigrant.3

2Grassroots campaigns by arts workers, namely Migrants in Culture, rally against the festival’s xenophobic propaganda, call for its cancellation, and propose a redistribution of its £120 million budget to aid a fair, sector-wide economic recovery.4 Similarly, cultural workers’ unions across the country have been striking against mass job losses at major arts institutions, which have received and unevenly distributed the government’s emergency funding, despite the already stark pay gap between low-paid contract workers (including non-art workers, such as cleaners, security, technicians, bar staff, and so on, most with precarious contracts), and directors and managers.5 In addition to unemployed and furloughed sector workers, arts freelancers have also been struggling with reduced or no work, with some unentitled to welfare. All were controversially advised by the Chancellor to “retrain” for other careers, publicly undermining the cultural sector and the extensive skills of arts professionals.6 Even with the Culture Recovery Fund, the government took advantage of the vulnerability of arts organisations to manufacture an artwashing publicity exercise, as grants were allocated on the condition that recipients must publicly thank the government beyond the standard requirements via social media, newsletters, and website communications, to further display deep gratitude through “local media outlets”.7 Many arts organisations, especially the third that were rejected from the Culture Recovery Fund, felt that this outcome further fosters the already toxic atmosphere of scarcity. It also contributes to the divisive competition for survival, based on an organisation’s prestige, size, and region, including the London-centrism of arts funding.8 With these developments, this moment holds a troubling outlook for the arts in the UK, as the formal cultural sector both economically comprises its core workers, and further excludes us through violent, nationalist ideologies.9

4Participation in the Arts

The accumulation of these changes significantly forecasts diminishing accessibility in British arts participation in the coming generations. Subsequently, it will raze the range of cultural leaders from minoritised backgrounds, who are crucial not only to an equitable arts sector, but also to one that works in tandem with the anti-colonial global climate justice movement. In addition to the pre-existing colonial remnants of the British Empire—such as intergenerational material, social and cultural capital—that leave the cultural elite unscathed by austerity, these further erosions of the cultural sector and public services make the arts in Britain an inhospitable space for many creatives and publics to participate.

This year, primary and secondary school educators have been banned from teaching with “anti-capitalist material”,10 and were warned that anyone teaching that “‘white privilege’ is an uncontested fact are breaking the law”.11 Critical race and anti-capitalist theories are integral to understanding climate injustices. Those most impacted by race, class, gender, LGBTQIA+, and disability injustices are also the most compromised by social, climate, and environmental injustices. Often arts programming tokenises these groups to fulfil funding criteria, further creating an unsafe space for political arts, evident in the prevalent institutional anti-Black racism.12 Ultimately, the British arts sector reproduces and normalises the violences of the UK political climate towards minoritised people. Where artistic practices that take climate change issues sincerely into account are inherently political, the increasingly challenging environment in British arts is yet another layer of barriers as we try to operate creatively and politically.

10Climate Change and British Arts

Working across climate change and the arts, I see many parallels between two. They both seek to engage audiences with realities and speculations around today’s urgencies. Yet they also integrate systemic barriers that restrict who is resourced to participate in the mainstream, to generate, share, and then eventually archive the types of experiences and knowledges that exist. The white supremacist, patriarchal, capitalist, and ableist structures in the mainstream UK “climate arts” have permeated from its elitist beginnings as part of Europe’s cultural sector. Similarly, the enlightenment-birthed environmental movement in Britain negates and erases the cultures, histories, and experiences of resistance of its former empire. Unethical institutional greenwashing persists through eco-aestheticised public programming, as a continuation of thriving neoliberal ideology, despite—and in order to capitalise on—the overlapping global crises of climate change, racial injustice, and a health crisis exacerbated by our current pandemic.

With this in mind, it is essential that working to communicate climate change issues through the arts must centre and be accountable to the people who have been minoritised by the climate movement, the arts sector, and the state in Britain. Through my curatorial projects under the name Worm: art + ecology, I am interested in creatively communicating anti-colonial climate activities and narratives. These should emphasise inclusive participation in everyday local and global climate activisms that consider racial, disability, class, gender, and LGBTQIA+ justices as directly related. My work interrogates the power structures of climate knowledges, shaped by colonial histories, imperialist sciences, corporate greed, and so on. Further, I see communal climate knowledges and storytelling as interrelated methods of co-learning, communicating, and interacting with the plurality of histories, presents and futures, facts and dreams.

Self-Archiving

Together with my invited contributors in this feature, I aim to draw alliances across geopolitical borders, languages, and creative activities between them as a group of people, who are individually unbound to one label of researcher, artist, or activist. A selection of our works make equally diverse and complementary cover illustrations for this issue of British Art Studies (figs. 1–5).

Sonia E. Barrett is a visual artist who meditates on the grand furnitures of the Great Houses and Estates across the UK, USA, and the Caribbean, which were built on the colonial wealth of the slave industries. In deconstructing and reassembling these mahogany “bodies”, she narrates the violent, extractive histories and migrations of peoples and trees from their lands (fig. 6). Barrett seeks to intervene her pieces back into the “crime scenes” of the British trusts and estates, which continue to hold colonially amassed wealth through land ownership.

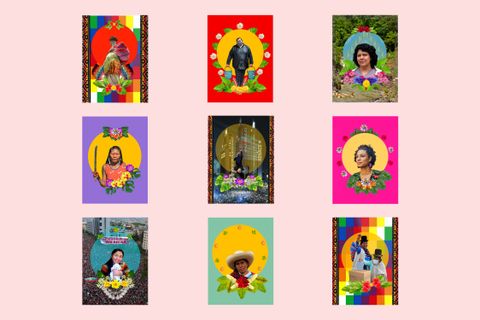

The Bonita Chola (aka Angela Camacho) is a Bolivian Indigenous creative, Bruja, and community organiser living in London, who takes us through her processes of documenting and archiving Indigenous and Afro-descendant community organisers through her social online platform. Her practice comprises colourful, immediate, and shareable image and text cards, which forefront accessibility, in both production and dissemination, of the news and herstories relating to anti-colonial, climate, and social justice issues (fig. 7).

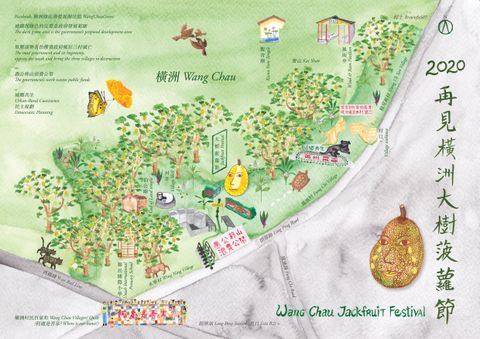

Michael Leung is an artist/designer and urban farmer in Hong Kong, sharing his research on the British “colonial residue and (non-)indigenous entanglements” in the New Territories. Standing alongside the Wang Chau villagers, who are currently facing eviction by the Hong Kong government, Michael’s watercolour paintings, photos, and anecdotes commune with the villagers’ collective farming, jackfruit harvest festival, campaigning, and everyday co-learning as determined acts of resistance (fig. 8).

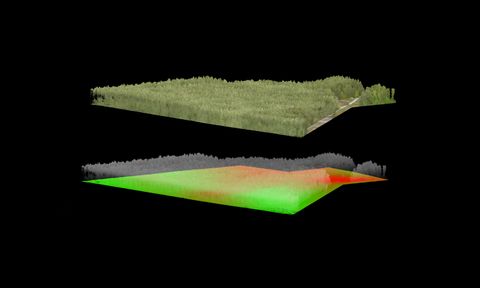

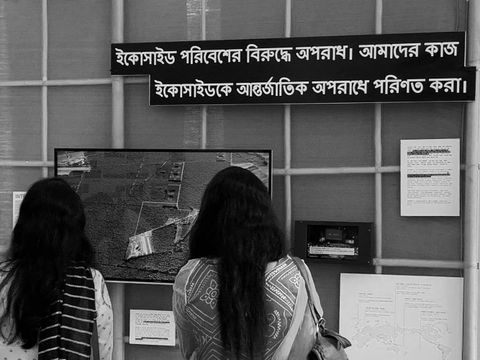

INTERPRT (Nabil Ahmed, Olga Lucko, Svitlana Lavrenchuk, and Filip Wesołowski) are a group of researchers, architects, and spatial designers advocating to criminalise ecocide, crimes against the environment, through the International Criminal Court. The studio’s extensive investigations use geospatial analysis and architectural methodologies to reconstruct cases of environmental violations in both war and peace times (fig. 9). They gather legislative and activist histories with visual cultures to further demonstrate the contemporary consequences of historical injustices, and to communicate potential tools for justice for climate and environmental frontlines.

For myself, Angela Chan, I introduce a visual research project that considers the biases, time-lining, and power structures of public climate communication framings in the UK. Critiquing a recent water scarcity report as falling short of inclusive and fair framing, I open communal “living room” conversations nationwide with other people from systemically minoritised backgrounds, who are often excluded from mainstream climate justice activities, to map and record our current relationships, practices, and perceptions towards water and its scarcity (fig. 10).

Through these articulate, informative, and reflective projects, we explore climate and social issues in the homes and communities we inhabit around the world, referring to Britain to contend with its colonial ties to our subjects, places, communities, and selves. We offer insights into various long-term projects and commitments to everyday climate and social justice around the world, with this cover commission as just the beginning of future collaborations and friendship. We destabilise the singular narrative of “the future of” or “the solution to” the climate crisis, as determined by the violent hegemonies that have caused and sustain it. All the while, we carve out our own self-organised archives by overwriting some histories with truth, creating vocabularies to strengthen international solidarity, and narrating our own timelines of place beyond borders."

About the author

-

Worm: art + ecology is a long-term curatorial project that communicates climate change issues through contemporary art and creative practices. Since 2014, it has produced online and gallery exhibitions, interviews with practitioners, and also delivers public workshops and talks that explore climate issues through intersectional frames.

Crossing disciplines to share different insights on climate and environmental realities, Worm: art + ecology encourages accessible approaches to these issues, working in collaboration with creative practitioners from groups that are systemically marginalised from often both the mainstream climate movement and the arts.

Worm: art + ecology strives to challenge the criteria for climate change expertise to centre climate justice. Central themes in the project’s artistic activities address racial and social justice as intrinsic to climate justice. They examine the history of climate change to create inclusive participation in dialogue with anti-colonial, decarbonised futures.

Worm: art + ecolog is a curatorial project by Angela YT Chan.

Footnotes

-

1

“British Art and Natural Forces” was the theme of the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art’s autumn 2020 research programme. A focal point of the programming was to discuss the relationship between visual representation, art history, and climate change. ↩︎

-

2

Theresa May’s 2018 plan for the “Festival of Great Britain and Northern Ireland” has been resurrected by Boris Johnson’s government as “Festival UK 2022”, and is known to critics as the “Festival of Brexit”; see Ben Quinn, “Government Pushes Ahead with Plans for ‘Festival of Brexit’”, The Guardian, 5 November 2020, (https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2019/nov/05/government-pushes-ahead-plans-festival-of-brexit)[https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2019/nov/05/government-pushes-ahead-plans-festival-of-brexit], accessed 20 November 2020. ↩︎

-

3

About, Festival UK 2022, (https://www.festival2022.uk/about)[https://www.festival2022.uk/about], accessed 20 November 2020. ↩︎

-

4

Migrants in Culture, FUK 2022, (http://migrantsinculture.com/f-uk-2022/)[http://migrantsinculture.com/f-uk-2022/], accessed 20 November 2020. ↩︎

-

5

Jonathan Knott, “Trade Unions Call For Overhaul of ‘Disastrous’ Cultural Policies”, Museums Association, 28 October 2020, (https://www.museumsassociation.org/museums-journal/news/2020/10/trade-unions-call-for-overhaul-of-disastrous-cultural-policies/)[https://www.museumsassociation.org/museums-journal/news/2020/10/trade-unions-call-for-overhaul-of-disastrous-cultural-policies/], accessed 20 November 2020. ↩︎

-

6

Pippa Allen-Kinross, “What Did Rishi Sunak Actually Say About People in the Arts?”, Full Fact, 7 October 2020, (https://fullfact.org/economy/rishi-sunak-arts-opportunities/)[https://fullfact.org/economy/rishi-sunak-arts-opportunities/], accessed 20 November 2020. ↩︎

-

7

Liz Hill and Adele Redmond, “Hundreds of Arts Organisations Rejected for Emergency Funding”, Arts Professional, 13 October 2020, (https://www.artsprofessional.co.uk/news/hundreds-arts-organisations-rejected-emergency-funding])[https://www.artsprofessional.co.uk/news/hundreds-arts-organisations-rejected-emergency-funding], accessed 20 November 2020. ↩︎

-

8

Oli Mould, “Whose Bailout is it Anyway? Saving the Arts may not Save Culture”, Tacity, 7 July 2020, (https://tacity.co.uk/2020/07/07/whose-bailout-is-it-anyway-saving-the-arts-may-not-save-culture/)[https://tacity.co.uk/2020/07/07/whose-bailout-is-it-anyway-saving-the-arts-may-not-save-culture/], accessed 20 November 2020. ↩︎

-

9

Dave O’Brien, “The Impact of Covid-19 on the DCMS Sectors: A Submission to the Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Select Committee Inquiry”, UK Parliament, 2020, (https://committees.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/5549/html/)[https://committees.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/5549/html/], accessed 20 November 2020. ↩︎

-

10

Mattha Busby, “Schools in England Told not to Use Material from Anti-Capitalist Groups”, The Guardian, 27 September 2020, (https://www.theguardian.com/education/2020/sep/27/uk-schools-told-not-to-use-anti-capitalist-material-in-teaching)[https://www.theguardian.com/education/2020/sep/27/uk-schools-told-not-to-use-anti-capitalist-material-in-teaching], accessed 20 November 2020. ↩︎

-

11

Jessica Murray, “Teaching White Privilege as Uncontested Fact is Illegal, Minister Says”, The Guardian, 20 October 2020, (https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/oct/20/teaching-white-privilege-is-a-fact-breaks-the-law-minister-says)[https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/oct/20/teaching-white-privilege-is-a-fact-breaks-the-law-minister-says], accessed 20 November 2020. ↩︎

-

12

Jade Montserrat, Cecilia Wee, and Michelle Williams Gamaker—UK Artists 4 BLM, Art Professional, “We Need Collectivity Against Structural and Institutional Racism in the Cultural Sector”, 24 June 2020, (https://www.artsprofessional.co.uk/magazine/article/we-need-collectivity-against-structural-and-institutional-racism-cultural-sector)[https://www.artsprofessional.co.uk/magazine/article/we-need-collectivity-against-structural-and-institutional-racism-cultural-sector], accessed 20 November 2020. ↩︎

Bibliography

Allen-Kinross, Pippa (2020) “What Did Rishi Sunak Actually Say About People in the Arts?” Full Fact, 7 October, https://fullfact.org/economy/rishi-sunak-arts-opportunities/. Accessed 20 November 2020.

Busby, Mattha (2020) “Schools in England Told not to Use Material From Anti-Capitalist Groups”. The Guardian, 27 September, https://www.theguardian.com/education/2020/sep/27/uk-schools-told-not-to-use-anti-capitalist-material-in-teaching. Accessed 20 November 2020.

Cambridge Water Company (2020) “The Great British Rain Paradox”. Cambridge Water Company News, https://www.cambridge-water.co.uk/news/the-great-british-rain-paradox. Accessed 21 November 2020.

Festival UK 2022 (n.d.) About, https://www.festival2022.uk/about. Accessed 20 November 2020.

Hill, Liz and Redmond, Adele (2020) “Hundreds of Arts Organisations Rejected for Emergency Funding”. Arts Professional, 13 October, https://www.artsprofessional.co.uk/news/hundreds-arts-organisations-rejected-emergency-funding. Accessed 20 November 2020.

Kimmerer, Robin Wall (2003) Gathering Moss: A Natural And Cultural History Of Mosses. Corvallis, OR: Oregon State University Press.

Knott, Jonathan (2020) “Trade Unions Call For Overhaul of ‘Disastrous’ Cultural Policies”. Museums Association, 28 October, https://www.museumsassociation.org/museums-journal/news/2020/10/trade-unions-call-for-overhaul-of-disastrous-cultural-policies/. Accessed 20 November 2020.

Migrants in Culture (n.d.) F*UK 2022, http://migrantsinculture.com/f-uk-2022/. Accessed 20 November 2020.

Montserrat, Jade, Wee, Cecilia, and Williams Gamaker, Michelle —UK Artists 4 BLM, Art Professional (2020) “We Need Collectivity Against Structural and Institutional Racism in the Cultural Sector”. 24 June, https://www.artsprofessional.co.uk/magazine/article/we-need-collectivity-against-structural-and-institutional-racism-cultural-sector. Accessed 20 November 2020.

Mould, Oli (2020) “Whose Bailout is it Anyway? Saving the Arts may not Save Culture”. Tacity, 7 July, https://tacity.co.uk/2020/07/07/whose-bailout-is-it-anyway-saving-the-arts-may-not-save-culture/. Accessed 20 November 2020.

Murray, Jessica (2020) “Teaching White Privilege as Uncontested Fact is Illegal, Minister Says”. The Guardian, 20 October, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/oct/20/teaching-white-privilege-is-a-fact-breaks-the-law-minister-says. Accessed 20 November 2020.

O’Brien, Dave (2020) “The Impact of Covid-19 on the DCMS Sectors: A Submission to the Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Select Committee Inquiry”. UK Parliament, https://committees.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/5549/html/. Accessed 20 November 2020.

Quinn, Ben (2020) “Government Pushes Ahead with Plans for ‘Festival of Brexit’”. The Guardian, 5 November, https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2019/nov/05/government-pushes-ahead-plans-festival-of-brexit. Accessed 20 November 2020.

Imprint

| Author | |

|---|---|

| Date | 30 November 2020 |

| Category | Artist Collaboration |

| Review status | Peer Reviewed (Editorial Group) |

| License | Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) |

| Downloads | PDF format |

| Article DOI | https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-18/worm |

| Cite as | + ecology, Worm: art. “Climate and Culture Beyond Borders.” In British Art Studies. London and New Haven: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art and Yale University Press, 2020. https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-18/worm. |