Bloodlines

Bloodlines: Circulating the Male Body Across Borders in Art and Anatomy 1780–1860

By Anthea Callen

Abstract

Art and anatomy in the nineteenth century were intimately linked male-dominated professions, where hand and eye united. These activities were key interconnected sites of male bonding, of growing professional identity formation, and of the construction of modern masculinity. For the Irish-born Maclise brothers, Daniel and Joseph, the bonds were also fraternal: brothers living and working together in London throughout their lives with a shared passion for life drawing, anatomy, and the human figure in pictorial representation. Dissecting, in particular, the lithographic drawings of surgeon-artist Joseph Maclise (1815–1880) in Richard Quain’s The Anatomy of the Arteries of the Human Body (1840–circa 1844) and his own Surgical Anatomy (1851, 1856, and 1859), this essay tracks the lifeblood of the anatomical arts circulating around the networks of specialists with whom Maclise was associated, from Cork and the capitals of Scotland, England, and France, across the Atlantic to Philadelphia and Boston. At a time when travel was far slower, surgeons, artists, and printmakers travelled long distances in search of greater learning, the flow returning to generate new knowledges in its places of origin. Like the Grand Tour, these journeys often lasted far longer than a passing tourist visit, at times entailing months or years of professional study and work—as in Joseph Maclise’s anatomy studies in Paris. The anatomical work, and its representation in images and texts, was thereby circulating in shared ideas, practices, teaching, books, manuals, atlases, art, and crucially, given that the (primarily) white male body was the “universal” body in medical anatomy, in shared ways of seeing and constituting the human (male) body.

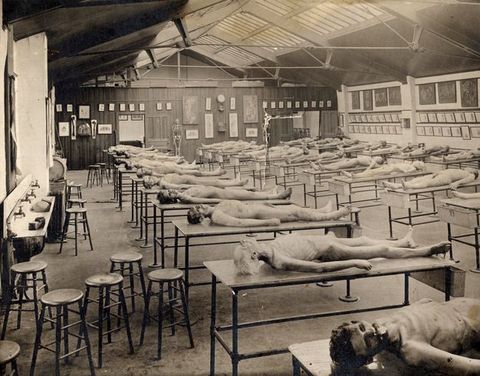

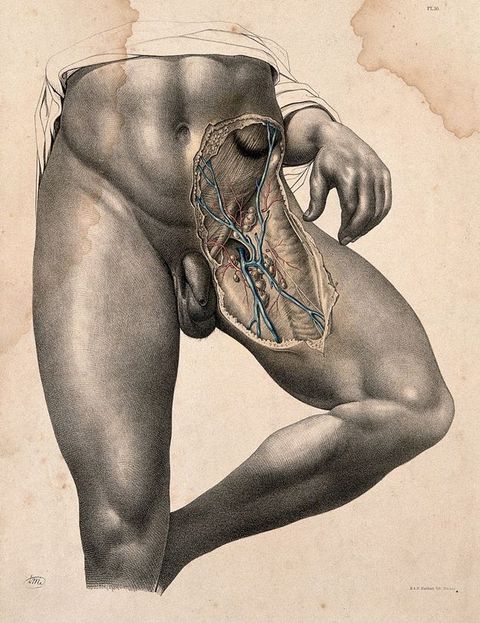

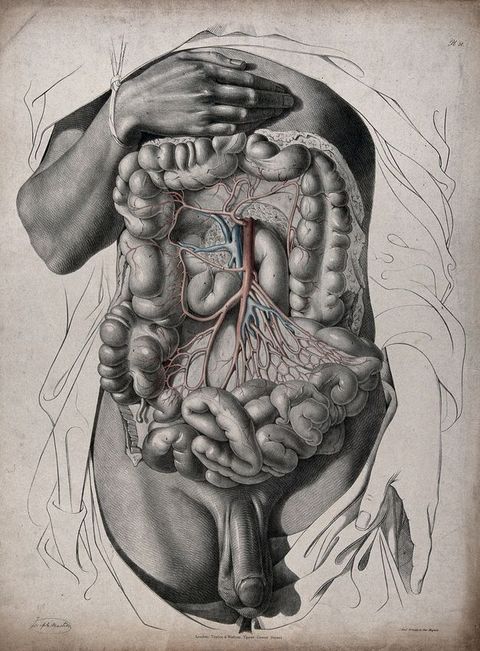

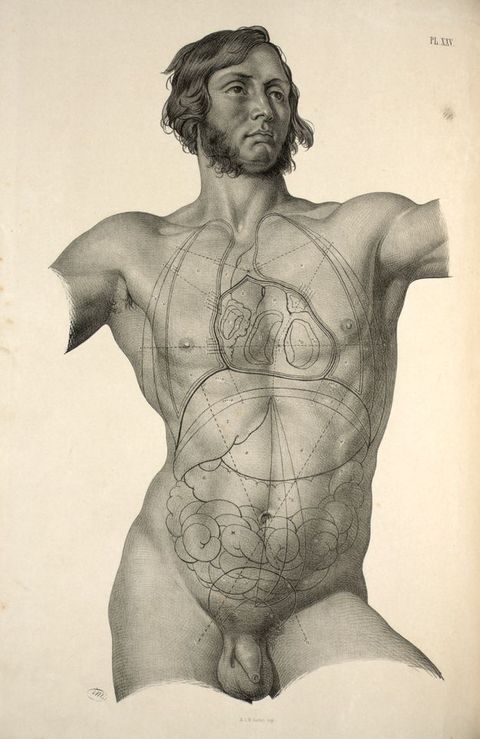

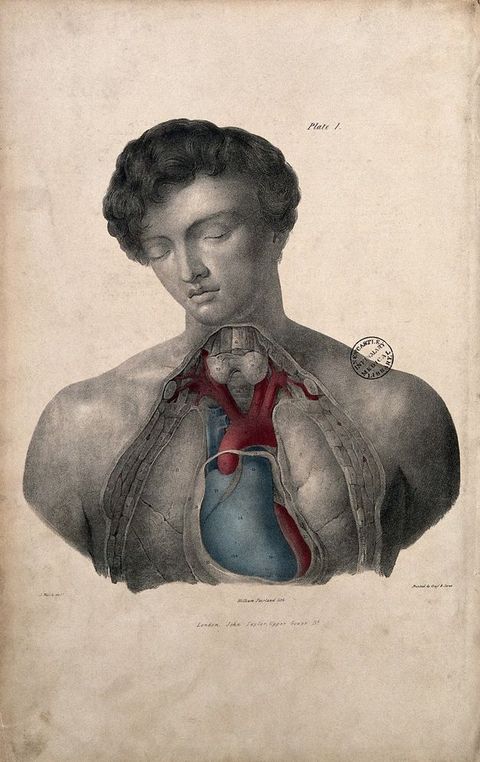

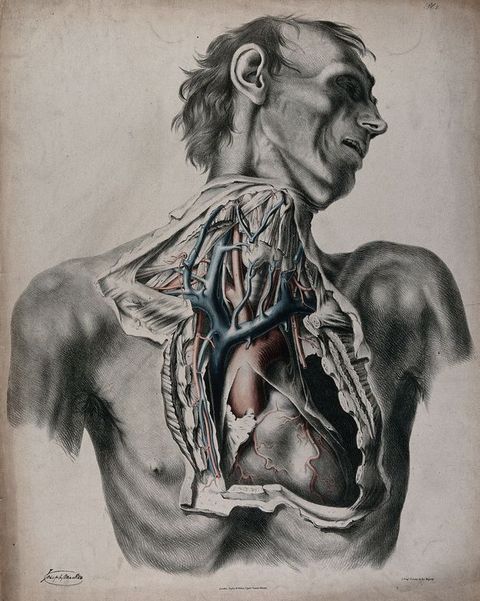

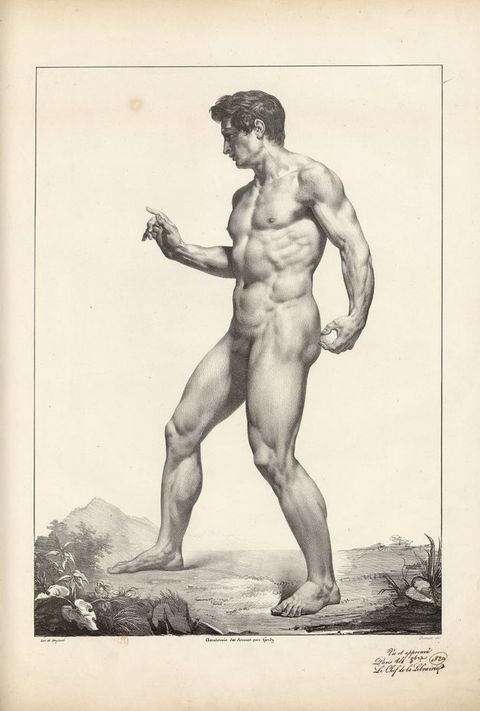

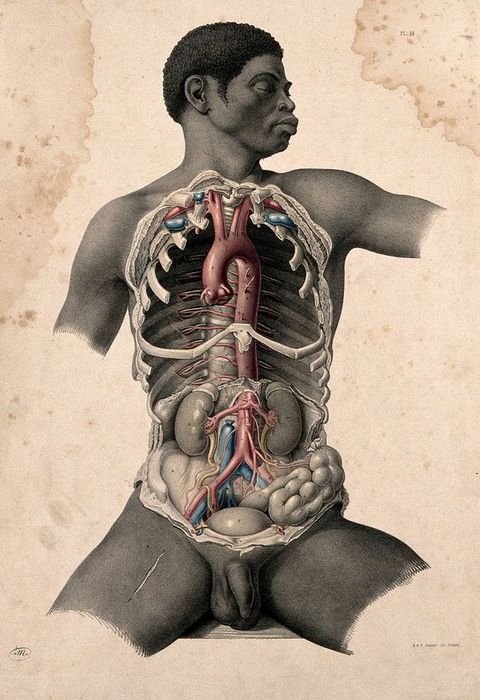

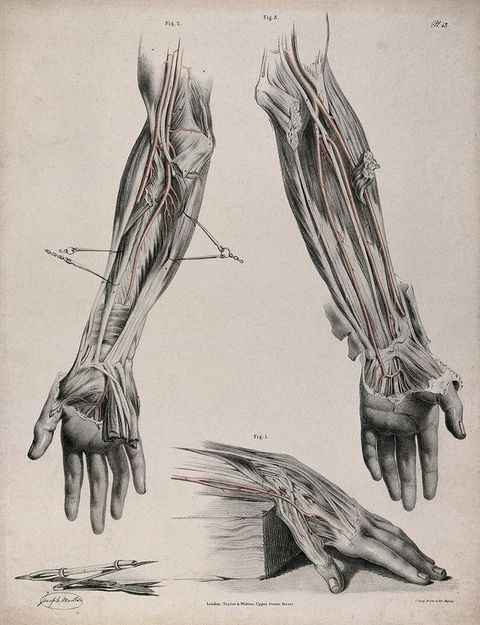

Art, anatomy, and printing in the nineteenth century were intimately linked, male-dominated professions, where hand and eye unite. All three activities were key interconnected sites of male bonding, of growing professional identity formation, and of the construction of modern masculinity.3 For the Irish-born Maclise brothers, Daniel and Joseph, these bonds were also fraternal: brothers living and working together throughout their lives with a shared passion for life drawing, anatomy, and the human figure in pictorial representation.4 Where Daniel as a history painter gained fame and royal patronage under the prince regent, executing monumental commissions for the Houses of Parliament, little is known of surgeon-anatomist Joseph.5 Here I argue that the difference between Joseph Maclise’s work as an accomplished artist-anatomist and that of previous anatomical illustrators is that he fused his dissection drawings with his studies after living “life models”, superimposing onto, incorporating these beautifully “airbrushed” innards into the superbly drawn bodies of his life figures: these are not cadavers, not those truly dead corpses with muscles tensed in rigor mortis found in anatomy dissection rooms (fig. 2).6 Where in Vesalius or Valverde, blatantly deathly figures act out life (albeit classically, mythologically inspired and often as memento mori), Maclise’s very real, athletic men perform death. Not only do his (almost exclusively) male models hold themselves in ways impossible to rope up or secure dead bodies, but also their flesh and muscle retain the full vigour and synergy of life.7

3Major Arteries

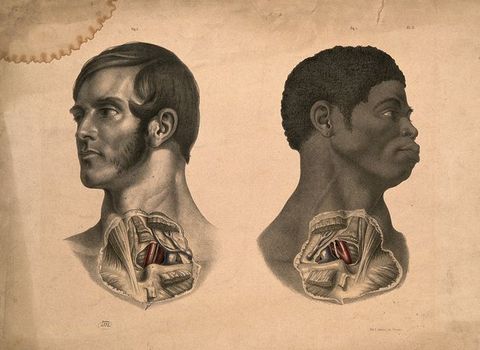

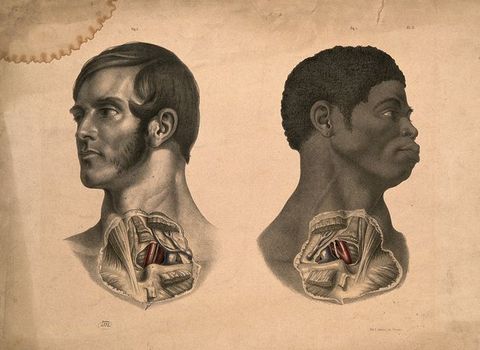

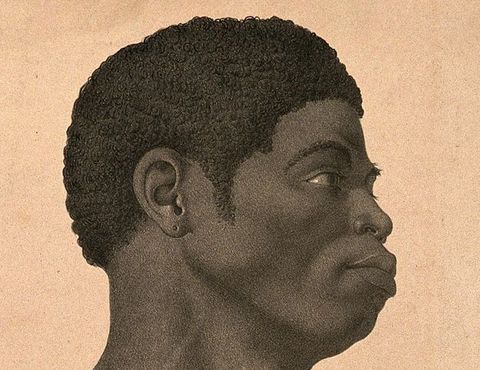

Dissecting the work of Joseph Maclise (1815–1880), this essay tracks the life-blood of the anatomical arts circulating around the networks of specialists with whom Maclise was associated, from Cork and the capitals of Scotland, England, and France, across the Atlantic to Philadelphia and Boston.8 At a time when travel was of course far slower, anatomists, surgeons, artists, and printmakers travelled long distances in search of greater learning, the flow returning to generate new knowledges in its places of origin. Like the Grand Tour, these journeys often lasted far longer than a passing tourist visit, at times entailing months or years of professional study and work—as in Joseph Maclise’s anatomy stage(s) in Paris. The anatomical work, and its representation in images and texts, was thereby circulating in shared ideas, practices, teaching, books, manuals, atlases, art, and crucially, given that the (primarily) white male body was the “universal” body in medical anatomy, in shared ways of seeing and constituting the human (male) body. As we shall see, Maclise’s lithographs, already unusual for the inclusion of Black men, are of such high quality that “ethnic” variations of skin tone are discernible even in this grey-scale medium. Although perhaps equally studied in anatomy dissection rooms, the female body was rare in anatomical prints, especially for teaching—and used almost exclusively to display female difference: woman’s generative organs.9 Female bodies caused concern and breaches of propriety in the male-student only dissection room.

8By 1800, human (pathological and comparative) anatomy was both a research science in its own right and the foundational study not just for surgeons, but increasingly also for all serious medical practitioners.10 Yet far from being a forked road where art and science irrevocably separated, this period in fact heralded an ever deeper mutual dependence, especially in anatomy, physiology, and nascent anthropology; this mutual dependence was further entrenched with the advent of photography in 1839, followed by radiographic and other imaging processes. Artists, too, continued to study anatomical dissection to hone their knowledge of the human body, gaining kudos from this association; anatomy professors trained artists while simultaneously relying on their representational skills to communicate their own learning—and their professional prestige in major portraits.11 Traditionally in Britain, physicians were university trained (Oxford and Cambridge in England, Edinburgh in Scotland, and Dublin in Ireland), as against surgeons whose more “craft” associated training had remained closely allied to the private anatomy schools, to the hospitals, and to apprenticeships or “demonstratorships”.12 Only once the Anglican stranglehold of the Oxbridge universities had been loosened in England, and secular medical schools like London’s University College had been founded (in 1826), did the expansion in anatomy teaching foster a burgeoning market in textbooks—as well as in bodies for dissection.13 Edinburgh surgeon-anatomists John (1763–1820) and Charles Bell's (1774–1842) quarto-sized publications with in-text images were pragmatically designed for individual student use, whereas the life-size lithographs in Maclise’s atlas (up to about 64 x 50 cm) for trainee surgeons were first released in loose-leaf fascicules, whether for use in libraries and lecture theatres, or pinned to the walls of anatomy schools, hospital dissection rooms, or operating theatres—or indeed for the specialist tastes of cognoscenti collectors.14

10Academy-trained professional artists, especially men like Daniel Maclise, with ambitions to excel in the top echelons of history painting, attended compulsory anatomy classes in the art academies of Cork, London, and Paris. The Maclise brothers were keen Europhiles with a particular passion for France: Daniel made his first visit to Paris in 1830, and he and Joseph are recorded there together in September 1844. After he finished at University College in 1839, and perhaps again in 1844, Joseph Maclise continued his anatomy studies in Paris, then not only world capital of art but also of Enlightenment natural sciences and medical research; there he undertook hundreds of anatomical dissections at Pierre-Nicolas Gerdy’s (1797–1856) École d’Anatomie attached to the Hôpital de la Pitié in the fifth arrondissement (fig. 3). As Maclise explained in his own preface to Surgical Anatomy (1851), the “illustrations made by myself from my own dissections” were “first planned at London University College”, presumably while still a student there, and “afterwards realised at the École Pratique, and School of Anatomy a few years since”.15 He would have left University College already briefed on his commission for Richard Quain’s Anatomy of the Arteries since the first plates appeared late in 1840, and he also did the groundwork in Paris for his own subsequent publications.16 For the journeyman anatomist or trainee surgeon at this time, the Hôpital de la Pitié had two distinct advantages. First, ready access to corpses: it was the Paris hospital-asylum for the poor and destitute, and hence furnished an endless supply of unclaimed bodies for dissection and, being located next to Sainte-Pélagie prison, it also had access to the corpses of criminals.17 Second, its chief anatomist-surgeon, Gerdy, was one of the most interesting and radical anatomists of his era: his work—and networks—were undoubtedly a key formative influence on Joseph Maclise.

15

Underpinning my discussion in this essay is the idea of a disinterested “objective” scientific gaze (Foucault’s “controlling” medical gaze), as distinct from its “subjective” counterpart, the artist’s gaze. Yet why so superior, different or mutually exclusive?18 These apparently distinct views are in fact shared, not least because they were jointly formed. Positioning the gaze as essentially embodied, subjective—as classed, racialised, gendered, sexed, socio-historically, and geographically specific—these two purportedly distinct visualities—science/art, “objective/subjective”—converge here in, and on, a single principal “subject”: at once the desiring male artist-anatomist and the desirable male (anatomical) body. In anatomical representation, there is often an obsessional, narcissistic scrutiny of the male body, whether in all its beauty or in all its sordid abjection; its circulation in this private scientific world authorised an entirely legitimate desiring gaze, a gaze seeking knowledge—but also pleasure and pain. The objective scientific gaze, like the artist’s gaze, is simultaneously a private libidinous gaze. So multiple lines of sight, visual positions, converge and enmesh on a single corpus: subjective, objective, libidinous, embodied.19

18Given the multi-sensory nature of artistic and medical practice alike, my discussion highlights their shared reliance on the senses of sight and touch.20 In medical research of the period, especially in diagnostics, the two senses are closely aligned.21 Imagine the intimate marriage of these senses necessary for brilliant French médécin-philosophe and pathological anatomist Xavier Bichat (1771–1802) to accomplish his remarkable anatomical taxonomy of human tissues and membranes, entirely without the visual aid of a microscope.22 John and Charles Bell also emphasised the importance of touch as well as vision, the latter writing treatises on both the eye and the hand; as we shall see, Joseph Maclise’s Parisian mentor Gerdy, too, researched the sense of touch.23 Seen in comparison to the work of contemporaries, or indeed almost any other anatomist, Maclise’s lithographic anatomies are strikingly erotic. Examining them here in fine-grained detail enables an exploration of the roles of sight and touch in the generation of an embodied libidinous gaze in art and anatomy alike.

20Corpses

Since the vast majority of bodies available for dissection belonged to the poor and destitute, the abject and powerless, anatomy was fundamentally an issue of class, of who held the power and who ended up on the slab. Anatomy schools sprang up conveniently alongside hospitals or asylums for the poor, or close to prisons. Xavier Bichat benefited, too, from the proliferation of available corpses during the Reign of Terror (1793–1794); even in his last year, he is reputed to have opened upwards of 600 bodies.24 Ironically, many such guillotined specimens would also have had the advantage of being young, healthy, and fit, albeit headless. Surgeon-anatomist Jean-Joseph Sue fils (1760–1830) and artist-surgeon Jean-Galbert Salvage (1772–1813) both profited too from the invaluable experience of war surgery on the battlefield—as did Charles Bell—and from access to dead soldiers or duellists for dissection.25 Salvage’s work entered the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture collections, as did his Anatomie du Gladiateur (1812), which other art academies also acquired, while in 1789 Sue fils himself inherited the chair of anatomy there from his father.26 A typical medical traveller in search of knowledge, Sue fils completed his MD in 1783 at the Royal College of Physicians in Edinburgh, overlapping there with John Bell, who had become a fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons in 1780. Both Sue fils, who wrote on the nature and experience of death by guillotine, and Bichat were among many anatomists researching key scientific questions of life and death, which were central preoccupations during this period and which pertain to my discussion of Joseph Maclise. Although Bichat’s research was unknown outside Paris when he died at the early age of thirty, by the 1840s, “his system of histology and pathological anatomy had taken both the French and English medical worlds by storm”.27 And just as from this period onwards in France corporal punishment and the scaffold were forbidden as public spectacles, so too did the carnivalesque public dissections in the European theatres of anatomy cease. This “discipline”, entering the professional realms of institutional science, was now hidden from the public gaze.28

24Between the 1820s and the 1860s, the overarching period covering Joseph Maclise’s publications, there were dramatic changes in the provision of anatomy teaching for medical students, aided by the 1832 Anatomy Act in Britain permitting the release of unclaimed bodies to science. The old private anatomy schools closed down or combined with the newly proliferating university and hospital medical schools which took over and regulated their role.29 Thus Charles Bell, for example, who in 1811 had moved his anatomical practice from his home into William Hunter’s (1718–1783) old Great Windmill Street School of Anatomy, became the first professor of anatomy and surgery at the London College of Surgeons in Lincoln’s Inn Fields in 1824. In 1829, the Great Windmill Street School of Anatomy was incorporated into the new (Anglican) King’s College medical school established to counter the new reformist London University College, to which Bell was appointed professor of surgery in that same year.30

29Arterioles

Edinburgh

At a moment in the late eighteenth century when modern medicine began its inexorable rise, John Bell’s work produced the first modern surgical anatomy. He elaborated not simply anatomists’ growing knowledge of the human body, its norms, and pathologies, but also offered insight into its surgical treatment.31 His brother Charles added further volumes at the turn of the century and in the years immediately following.

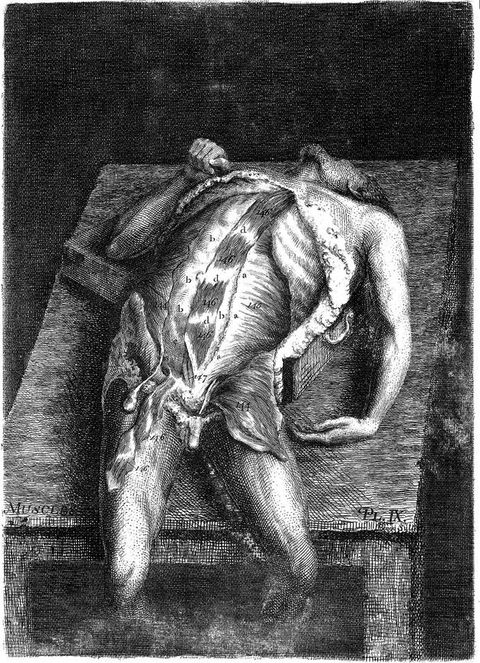

31Although published in the relatively small octavo, John Bell’s plates were uncompromisingly blunt: rendered with an almost aggressive crudity, a Rembrandtesque chiaroscuro adds atmospheric gloom to his anti-aesthetic pictorial “naturalism”. Aiming, he states in the preface to his 1794 Engravings Explaining the Anatomy of the Bones, Muscles and Joints, at the “useful” (for the student) rather than the “beautiful”,32 Bell explains:

32His “gothic horror” anatomical plates figured the violence of dissection. Unmistakably dead, his corpses and body parts lie abruptly dumped on tables or strung up with gallows-style ropes, set in awkwardly angled compositions within dingy interiors closed off from light and air (fig. 4). Here, we are told, is the natural home of dissection: in mean, ill-lit backrooms or dank basements, like the dark underground chambers of Henri Gervex’s (1852–1929) oil study Autopsy at the Hôtel-Dieu (1875) (fig. 5).34

34

All outward appearance of respect for the dead that might be politely parsed in a classical idiom is in Bell sacrificed to the sceptic’s plain-speaking eye. Thus, Bell’s etchings, deeply blackened with the oily printing ink, render the dissection slab a terrifying scene of back-street butchery, torture, and human sacrifice, anticipating by over twenty years literary works like Mary Shelley’s (1797–1851) Frankenstein (1818) and the later anatomist-turned-author Eugène Sue’s (1804–1857, son of Sue fils) Les Mystères de Paris (1830).35 John Bell’s prints, then, are unmediated by conventional “taste” or by examples drawn from classical Greek or Roman models, deliberately eschewing the cultivated mannerisms that made ideal anatomies socially acceptable. Effectively the founder of applied surgical anatomy and Scotland’s most successful surgeon in his time, John Bell flaunted his materialist expertise in the dissecting room in the face of his rivals, the Edinburgh University and Edinburgh Royal Hospital medical elite: not for Bell the niceties of the Edinburgh drawing room.36

35Arguing as powerfully for plainness of words as for directness of images, John Bell decried professional anatomists’ self-defeating obscurantism which, especially in language, alienated young would-be practitioners in the field.37 Analysing a range of historical illustrations widely deployed or imitated, from Vesalius (1514–1564) on, Bell described the continual struggle between painter and anatomist—the “one striving for elegance of form, the other for accuracy of representation”.38 Derived merely from the imagination of the painter, he noted, such illustrations show “sturdy and active figures, with a ludicrous contrast of furious countenances, and active limbs, combined with ragged muscles, and naked bones, and dissected bowels, which they are busily employed in supporting, forsooth, or demonstrating with their hands.”39

37This was, Bell argued (referring to Albinus), like a “statue anatomised”, where “all the irregularities of substance, all the gradations of bones, ligaments, tendon, and flesh, are rounded down with studied smoothness; it is a figure that can never compare with the body as it lies before him for dissection”.40 Instead of this “vitious [sic] practice” images illustrating anatomy texts should be “useful” rather than “elegant” and “tasteful”, presented, Bell argued, only as they appear on the dissecting table during the procedures, notably with “enough of the general figure … kept there to explain the posture of the parts”.41 This could only be achieved, we understand, by a singular talent combining both the artistic and scientific—like his own and that of his younger brother Charles, and, of course, Joseph Maclise. Following John Bell, Maclise was a strict adherent to evidential science; yet, in Maclise’s atlas-size plates, representation of the “general figure” came almost to dominate over the dissection itself, and death succumbed to life.

40Cork

Beginning his art studies as a youth in Cork, copying classical casts in Crawford Art Gallery from the newly acquired collection cast by Antonio Canova, from 1828, Daniel Maclise continued his art studies at the Royal Academy in London.43 Joseph Maclise may also have drawn from these casts and would certainly have known them. Daniel began his anatomy studies too in Cork, with the influential military surgeon, anatomist, and art enthusiast John Woodroffe (1788–1859), attending his lectures over a number of years and devoting “many winters” to dissection.44 The Cork network was highly influential within London circles too; Richard Quain (1800–1887) may well have studied under Woodroffe, who probably taught Joseph Maclise, too. Woodroffe, in turn, commended Maclise to Quain at University College in London to continue his studies, and where in 1832 Quain was appointed professor of descriptive anatomy.45

43In the preface to his Anatomy of the Arteries of the Human Body (1840–circa 1844), Richard Quain described his illustrator Joseph Maclise as “my former pupil”.46 Maclise gained his licentiate at University College in 1839 and by the date of Quain’s publication was working “at the duties of his profession”.47 Joseph himself named his teachers at University College as Robert Liston (1794–1847) and Samuel Cooper (1780–1848); it was to them (as well as his fellow students), rather than Quain, that Maclise dedicated his Surgical Anatomy.48,49 Samuel Cooper gave Joseph Maclise the intellectual and discursive basis for his publishing interests, while Robert Liston taught him the incisive surgical dexterity which, thanks to Joseph’s equal dexterity with both scalpel and pencil, provided the perfect combination for his anatomical publications. Like his brother Daniel, Joseph Maclise was a superb draughtsman of the human body; indeed, Joseph was perhaps the greater of the two, with his more instinctive feel for composition and bold treatment, but with the same sharp eye for detail. Joseph’s figures are more powerfully emotive than those of Daniel—who could not resist a trivialising anecdotalism in the gestures and expressions of his figures, even when making grand history paintings like The Death of Nelson or Waterloo (1858–1864) (fig. 6, see also fig. 10).

46

London

The urban geographies of London and Paris were highly significant to the Maclise brothers, who are known to have lived together throughout their lives, with sister Isabella as their housekeeper.50 Daniel Maclise arrived in London in 1827 aged twenty-one, enrolling at the Royal Academy the following year. His brother followed him to London, perhaps at the of age twenty-two in 1837, the year Daniel took up residence in 14 Russell Place (fig. 7).51 It was here that Daniel must have had his studio, and where doubtless the brothers worked side by side drawing together from the muscular male life models that are characteristic in the oeuvre of both. Eventually, this would also be the address of Joseph’s surgical practice.52 Yet, since he qualified in 1839, it is more likely Joseph arrived in London considerably earlier when, from 1831 to 1837, Daniel lived just a few doors south at 63 Charlotte Street.53 An area of good houses, constructed only thirty years previously, Fitzrovia was renowned for its artists as well as the artists’ trades: John Constable (a tutor of Daniel Maclise at the RA) lived at 78 Charlotte Street from 1822–1837, finishing The Lock, Salisbury Cathedral, and Hampstead Heath while there.54

50

Right across the street from the Maclises, at 64 Charlotte Street, lived and worked the famous lithographic printers that Joseph chose for his Surgical Anatomy plates: Michael and Nicolas Hanhart, who came to London in the 1820s. They were from the same Mulhouse/Paris stable as Godefroy Engelmann (1788–1839) and Jeremiah Graf, “Printers to Her Majesty”.55,56 Indeed, in this early period, lithographers were an even more interconnected fraternity than artists or anatomists. Graf was the lithographer selected by Quain to print Maclise’s illustrations to his Anatomy of the Arteries of the Human Body in 1840–circa 1844. Jeremiah Graf and Godefroy’s nephew Auguste Engelmann had established a lithography business in London in 1826, joined there from Paris by Michael Hanhart in 1828 as an assistant, then manager. In 1830, M. & N. Hanhart established their own lithographic business in Charlotte Street, when the Engelmann London branch (Engelmann, Graf & Coindet) failed. Jeremiah Graf too, apparently with his brother Charles, set up his own business nearby that same year, first at 14 Newman Street (also Fitzrovia) and, by 1838, at 16 Castle Street (now Eastcastle Street), just off Charlotte Street.57 The proximity of both Graf and M. & N. Hanhart to the Maclise residence meant that not only were they familiars but, in the case of Hanhart, Joseph had merely to cross the street to work on his stones at the printers’ (where studios with stones were made available) or, as was also customary at this period, stones for artists’ to work on were delivered to their studios.58 Conveniently too, for both Maclise brothers, the firm of Winsor & Newton, artists’ colourmen, was established in 1832 just down from Charlotte Street at 38 Rathbone Place. George Rowney Colourmen had begun around the corner at 10 and 11 Percy Street in 1783; by the 1850s, they had their retail outlet at 51 Rathbone Place, with wholesale at 10 Percy Street.59

55Paris

The precise dates of Joseph Maclise’s anatomy studies in Paris are uncertain. He most likely worked there for a couple of years immediately after qualifying at London University College in 1839, but he was certainly back in Paris for an extended period in 1844. By summer 1844, Maclise’s lithographic plates for Quain’s The Anatomy of the Arteries of the Human Body would have been more or less completed, and some of these provided the backbone for his own Surgical Anatomy (1851). Daniel Maclise had first visited the city while still a Royal Academy student, just after the “Three Glorious Days” of the July Revolution in France in 1830. His return visit for a month in 1844 confirms Joseph was already in Paris and perhaps based again at the École d’Anatomie at L’Hôpital de la Pitié.60 It was probably late August when Daniel joined “Joe”, who was living in student lodgings at Hôtel Corneille, rue Corneille, in the Luxembourg area centrally located between the Sorbonne and the Écoles de Médecine and Beaux-Arts (see fig. 3). The hotel served as a residence, as he reported, “… principally occupied by students of every grade and style, and of every profession—clerical, law-yal [sic], medical, artistical”.61 Daniel had already been three weeks in Paris when he wrote this, and his description illuminates Joseph Maclise’s circumstances while working in Paris:

6062I am au quatrième in a small room in the … hotel, my bed in a recess at one end, and the casement opening from ceiling to floor at the other. It commands a view of the Odéon Theatre, which is on the opposite side of the narrow street … On the left, I can see the principal dome of the Palace of the Luxembourg, and can be in the Gallery in 2½ minutes from my bedroom. I have a little bed, a little chair, a little chest of drawers, a big looking glass, a large washing-basin, jug, and water-bottle; the room is surrounded by shelves for books, the floor is polished oak, laid down in a pattern, and this is, I believe, the exact model of all the rooms in the house … Each floor is served by a garçon, who is every man’s factotum; he makes the bed, cleans the boots, brushes the clothes, stitches on buttons, and does everything that the necessities of fifty men require. … I fortunately got into the very next room to Joe, which was unoccupied, the tenant having just left the day before …

I breakfast and dine, and do all that I have to do, from home. I am out from nine in the morning; I am choke-full up to my eyes in pictures; I never saw so much in all my life put together; it has taken me from ten in the morning till four in the afternoon, for three days together, constantly walking, to see the miles of canvas in Versailles.62

In his descriptions of the sites and galleries he visited, and of the many notable London friends (mainly artistic) he met, who were also in Paris on tour, Daniel scarcely mentions his brother.63 Nevertheless, since Joseph was known to frequent the galleries and museums, it is likely that for much of Daniel’s stay they joined forces. It is clear it was quite customary to drop into the studios of artists one admired, or who were friends/associates; presumably Joseph also engaged in this practice—and in visits to lithographers like Engelmann associated with his London printers.

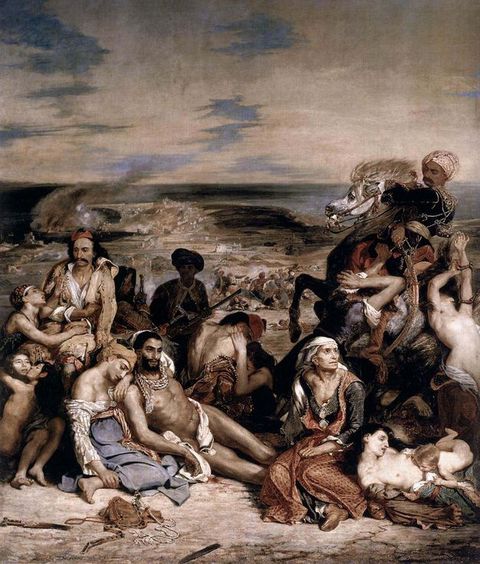

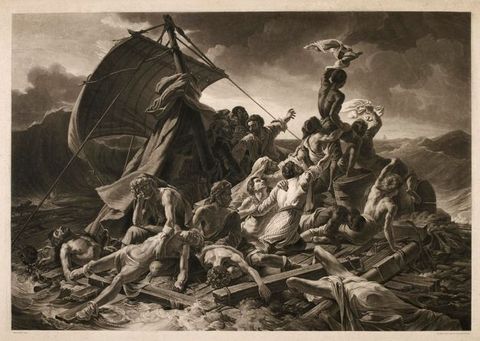

63Together in Paris, Daniel and Joseph Maclise undoubtedly visited the artworks both greatly admired, including the Louvre’s Napoleonic paintings by Antoine-Jean Gros (1771–1835) and Paul Delaroche’s (1797–1856) Execution of Lady Jane Grey (1833), plus his recently completed L’Hémicycle du Palais des Beaux-Arts (1837–1841) at the Palais des Beaux-Arts, which Daniel claimed to visit almost daily.64 The Maclises both admired Théodore Gericault’s (1791–1824) monumental Raft of the Medusa (1819), which entered the Louvre in 1824, soon after the artist’s early death (fig. 7).65 However, according to Nicolas-Sebastien Maillot’s 1831 painting, Raft of the Medusa Shown in Salon Carré of the Louvre, the huge canvas was then hung too high for close study (fig. 8). In his monumental history painting, The Meeting of Wellington and Blücher after Waterloo (1861), Daniel follows Gros’ heroic Napoleonic dramas like the Retreat from Moscow in his own treatment of the foreground dead (fig. 9).66 Particular poses in The Meeting of Wellington and Blücher after Waterloo owe a clear debt too, to Gericault’s Raft of the Medusa: two sprawled soldiers (far left and right) in eye-catching white breeches, are direct quotes, in reverse, of the foreground right corpse posed by Delacroix for Gericault’s painting. Likewise, the beautifully modelled thighs and the use of eroticising drapery in this Gericault/Delacroix nude find powerful echoes in Joseph’s drawings, for example, Plate 16 of Surgical Anatomy (1851) (fig. 10), with its equally sumptuous thighs; here, the cursorily suggested white drapery nevertheless performs a key narrative function: akin to a lifted shirt, it serves a seductive, revelatory role more associated with female nudes, drawing the eye to the genitals, rather than (as in the Gericault) covering them up. This device had been yet more provocatively deployed by Maclise in his abdomen dissection for Quain (circa 1844, Plate 51) (fig. 11). Maclise’s drapery is remarkably pristine compared to the filthy rags we sense in John Bell’s prints—or yet the blood-soaked cloth draped across the central nude in Delacroix’s Massacre at Chios (1824), also in the Louvre (fig. 12).67 Delacroix’s modern Greek god, his languidly beautiful body and rich olive skin, echoed by Joseph Maclise in his Plate 51 for Quain, lies dying in a position commonly used when starting dissection: even closer is the pose of the corpse, far left, in Gericault’s Raft of the Medusa.

64

In addition to the painting’s material presence on view in Paris, several prints after Gericault’s Raft of the Medusa were circulating in London from the time of Gericault and his friend Nicolas Toussaint Charlet’s (1792–1845) British tour of the painting during April 1820–December 1821; Charlet produced a first, somewhat woodcut-like lithograph in 1820, which was published at least twice (in 1820 and 1823).68 Often attributed to Gericault, Charlet was in fact its principal author, and since Charlet himself became a renowned lithographic printmaker, their work together in London exploiting the medium is no surprise.69 Gericault was one of the first major artists, in 1817, to experiment with lithography as an artistic rather than a purely reproductive medium, rapidly becoming an adept—as did Delacroix. The medium’s immediacy, precision, and versatility stemmed from the directness of the artist’s drawn chalk mark on the prepared stone surface.70 Although obviously reversed, the resulting print was an exact replica of the drawing retaining its original qualities of draughtsmanship and personal “touch”: a reproducible drawing. It could be fine and delicate like silverpoint, or rich with deep tone and sfumato. Since artists themselves could draw directly on the stone, the process could eliminate the intermediary craftsman or designer; intaglio methods, however, required the help (as in the case of John Bell) or full intervention of a skilled craftsman-artisan, who engraved the drawing onto the copper plate. Lithographic prints were also therefore cheaper as well as almost endlessly repeatable.71

68However, Charlet’s choice of a linear rather than a tonal print after Gericault’s Raft of the Medusa meant it lost all the chiaroscuresque drama and painterliness of the original. Much closer in painterly feel was the print made for the mass market by British printmaker, Samuel William Reynolds (1773–1835) (fig. 14). His mezzotint (circa 1829) was undoubtedly made in Paris, since it was printed by F. Chardon, 30 rue Hautefeuille (just off Boulevard St Germain between Boulevard St Michel and Place de l’Odéon), and not long after Gericault’s painting entered the Louvre. Also a friend of Charlet, and probably encouraged by him, Reynolds often visited Paris and was certainly there in the later 1820s; he was a painter and printmaker whose work was more widely appreciated on the Continent than in Britain and he regularly exhibited at the Paris Salon.72 Reynolds’ mezzotint of the Raft of the Medusa meant the painting that proved so popular in Britain was already available in print and circulating in Paris and London by 1829; Daniel could have acquired a copy in Paris in 1830.73

72

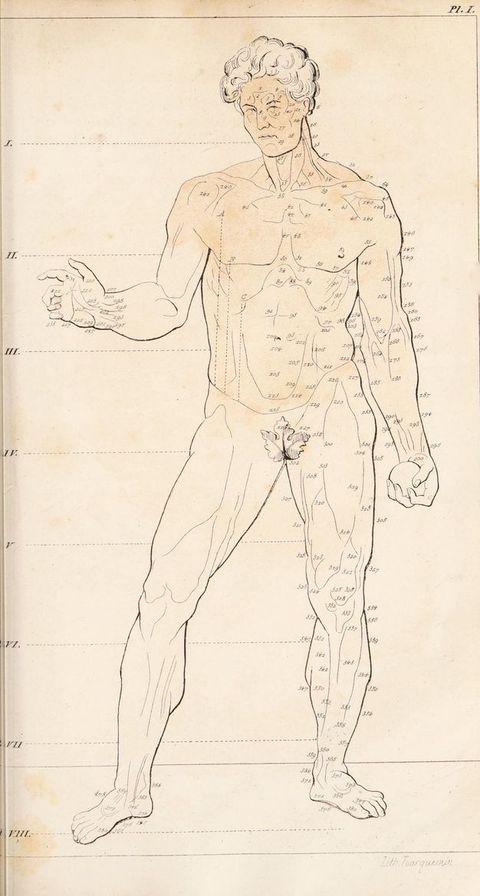

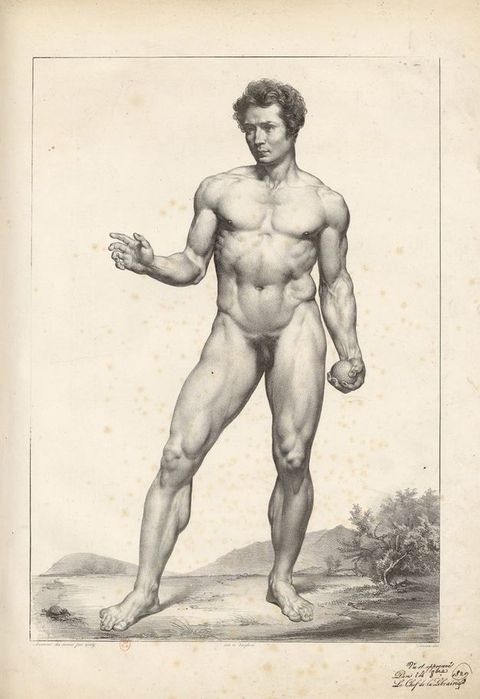

Still more telling are the networks in Paris that Joseph Maclise accessed through Pierre-Nicolas Gerdy and his École d’Anatomie. Like Maclise, Gerdy was deeply committed to sensory evidence and reason in the science of anatomy, first publishing his ideas in a pamphlet in 1844.74 Thus, during the likely period of Maclise’s stage there, Gerdy was researching touch and skin sensation.75 Throughout the 1820s, he welcomed artists as well as medics at the École d’Anatomie, running courses in which a key feature for all students was work from the “living figure”, which he deemed crucial to a real understanding of human anatomy. Gerdy advertised his dedicated Cours d’anatomie appliquée à la peinture et à la sculpture in 1827 and, in 1829, published his atlas, Anatomie des peintres, with three lithographic figures posed in conventional front, back, and side views; separate linear key plates avoided complex key letters marring his figures (figs. 15–17).76 Both publications coincided with Gerdy’s bid for the chair of anatomy at the École des Beaux-Arts.77 Many students from the Beaux-Arts preferred his teaching to that of ageing incumbent Professor Jean-Joseph Sue (1760–1830), whose classes they deserted in droves; Gerdy was young, exciting, and interdisciplinary. Significantly, not only did he teach from the live model but also from paintings and sculpture, closing his curriculum with “considérations historiques et bibliographiques sur l’anatomie, les beaux-arts, et par des promenades anatomiques dans les jardins et les musées publics, pour y analyser les reliefs sensibles sur les statues et les tableaux”.78 He was (in)famous for his student tours of the Louvre, critiquing artists’ anatomical knowledge in great works of art. Gerdy’s emphasis on the living body in the actual and pictorial underpinned all his teaching, although in his treatises he (like Bichat) placed great emphasis on weighty and at times impenetrable textual description. Even his innovative classes, founded on the study of surface anatomy, entailed obsessive description of every curve, bump, and crevice of the human body (see fig. 15). His students clearly loved him: there were riots and two years of strikes at the École des Beaux-Arts when, in 1830, Gerdy was passed over for the chair, ostensibly on the grounds of his youth.79

74

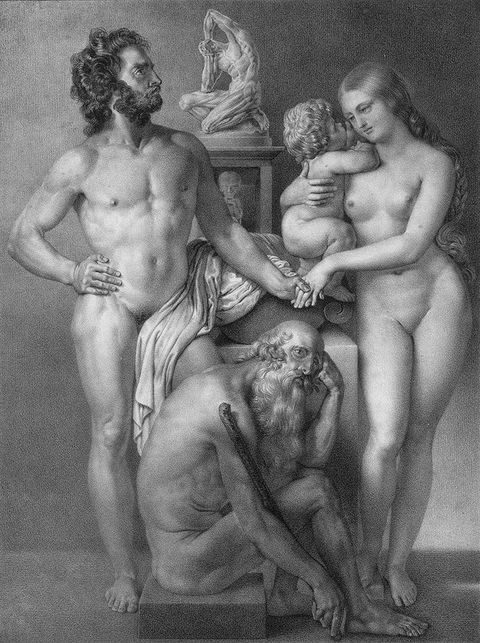

Before Gericault’s untimely death, he too probably worked with Gerdy and, through him, may have had access to the corpses and body parts he studied in his studio while working on the Raft of the Medusa. Gerdy had links too with Gros, whose students at the École des Beaux-Arts also studied with Gerdy: under Gros, Maximilien-Félix Demesse (1806–18??) competed unsuccessfully four times for the Prix de Rome, in 1827–1830.80 Demesse provided the surface anatomy drawings for Gerdy’s lithographic illustrations to his Anatomie des peintres: he even redeployed this same frontal figure for the protagonist Méléagre in his concour esquisse for the Rome Prize in 1830 (fig. 18). His master Gros’ own early life studies, dynamic and muscular (fig. 19), make a telling comparison too with the models of Maclise (see fig. 16). While the overall muscular athleticism is comparable, Maclise gives his figures an extraordinary, extrovert vitality, openly disporting themselves as if to a complicit viewer. Notable, too, is Gros’ academic treatment of the genitals, reduced to a shrunken, abstracted pouch; the contrast reveals just how daringly explicit were those of Maclise, even given the rationale of their medical context. While working in Paris, Joseph Maclise could well have attended Gros’ studio to pursue his life drawing, or equally the open Académie Suisse life studio frequented by all the great artists of the period, which was located on Île de la Cité, just across the Pont Saint-Michel on the Quai des Orfèvres (see fig. 3).81 Demesse’s life drawings for Gerdy were printed by lithographer Pierre Langlumé (1790–18??), who exhibited at the Paris Salon in 1822 and 1824, and whose printing workshop was conveniently located at 6 rue de l’Abbaye, between the École des Beaux-Arts and the École de Médecine.82 Through Gerdy, Joseph Maclise likely met Demesse and Gros, and, while in Paris, Maclise himself may have practised lithography, perhaps at Langlumé’s (then owned by Bénard), or with Jean Engelmann—son of Godefroy, an associate of Maclise’s London printers Graf and the Hanharts—perhaps alongside the renowned Nicolas-Henri Jacob (1782–1871), who lived next door to Langlumé/Bénard, at 4 rue de l’Abbaye.83 Trained under Jacques-Louis David and professor of drawing at the École nationale vétérinaire d’Alfort (1818–1830), Jacob was artist-lithographer to the renowned anatomist Jean-Baptiste-Marc Bourgery (1797–1849), whose magisterial Traité complet de l’anatomie de l’homme (1831–1854), which Joseph would have known, ran to fourteen volumes, including eight of plates, with over 700 illustrations.84 Early on, Jacob had demonstrated the new medium in practice in his 1819 lithograph, The Genius of Lithography: his 1831 frontispiece for Bourgery flaunted his Davidian credentials and penchant for male muscle (fig. 20).85

80

Delectable Bodies / corpus delecti

A key characteristic of all exemplary dissection écorchés (cast from flayed corpses) on display in anatomy schools was their muscular fitness: in life, they were exclusively well-built soldiers, duellists, pugilists. So for artistic anatomists like Joseph Maclise, even in death, high manly ideals prevailed.87 Indeed, I contend that the figures in Maclise’s anatomies actually were live models: men drawn from life and probably in the studio alongside Daniel—the latter preparatory to his grand historical battle scenes full of military men, the former his “ideal” guardsmen stripped off in the life room and transformed on the lithographic stone into living anatomical specimens.88 They are designed, as Joseph stated, “to indicate the interior through the superficies, and thereby illustrate the whole living body which concerns surgery”, which was precisely Gerdy’s philosophy in teaching anatomy to artists and surgeons alike.89 Rather than making complete and finished drawings after his dissected bodies for his lithographic figures, or indeed drawing them directly on stone in the anatomy room, Maclise must first have made detailed preparatory drawings just of the dissected parts, and later transposed these, incorporating them onto/into his figures drawn in the studio from life. Joseph may have made drawings from the life model leaving blank spaces ready to receive the dissected details to scale, or possibly he made composites: scaled dissection drawings pasted over a ready-drawn figure, which he would then redraw complete onto stone.90 No studies or life drawings on paper seem to survive which could elucidate his method, and nor do there seem to be extant life drawings of Daniel for comparison; the latter’s full-scale cartoons that include semi-naked male figures are the closest one gets to the latter’s method.91

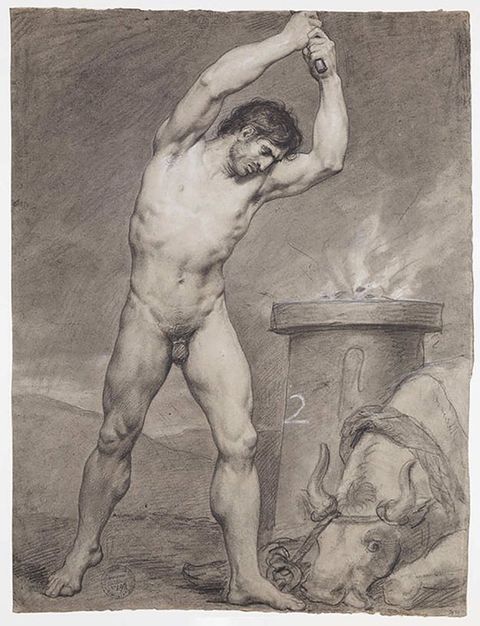

87Comparing work by other British contemporaries, for example, William Fairland’s lithographs after J. Walsh’s drawings (1837), while powerfully emotive, lack the taut anatomical precision and skilled figure drawing of Maclise.92 This is partly the result of a less coherent light source than is customary in Maclise, but also their romantic figure of a young male, appears decontextualised, a cut-out floating in the middle of the sheet (fig. 21).93 Similar figures by Maclise, like John Bell’s (see fig. 4), inhabit “real” space: a table, or a surface with objects, drapery, the outline of a chair all evoke an inhabited spatial setting. Nevertheless, the richly sensual chiaroscuro in Walsh’s anatomical figures, almost closer in appearance to mezzotint, are a probable influence on Maclise’s lithographs, most notably in his own Surgical Anatomy of 1851. Walsh’s drawing romanticises its subject, a muscular and healthy young beauty with a glorious sweep of curly hair stylishly coiffed as if “in life”, his eyelids simply lowered at rest. Light and shade in Maclise’s lithographs are more closely observed: his directional light source produces greater formal, and hence representational, coherence than does Walsh’s more “abstracted” light, that merely catches the corporeal prominences. There was something of this, however, in Maclise’s first lithographs for Quain (fig. 22). Walsh depicts a youth’s head on a man’s body; the sumptuous tonalities and modelling have all the romantic mystery of a Gericault académie. Yet, despite being a dissection illustration, the Walsh lacks the taut violence that in Gericault is rarely far below the surface and which, as in the mature Maclise, is sublimely erotic: desire, sex, and death come together.

92

Similar in style to Walsh/Fairland, the later anatomical lithographs Fairland produced for Francis Sibson’s (1814–1876) Medical Anatomy (1869), deployed Sibson’s idiosyncratic technical procedure for tracing his own dissections, which were then lithographed by William Fairland. Sibson describes his work thus:

94This … and all the following plates were taken from dissections made by myself. I took the outlines of the organs by the aid of a transparent tracing frame … Those outlines formed the groundwork for the coloured drawings from the body, which, as well as the lithographs, were executed with untiring care by Mr Fairland, under my close supervision. The lithographs have been carefully coloured, from the original drawings, by Mr Sherwin.94

This overly complex process, difficult to imagine in practice (how such a tracing frame could be set up and worked on above a corpse on a slab), is not known to have been widely adopted. Inventive though it is, it suggests the mind of a pure scientist complicating an otherwise direct transcription that could be produced by any good artist, including Fairland himself, but especially one like Joseph Maclise, who was also a surgeon-anatomist. Crucially, in Sibson’s case, it enabled the anatomist to retain full control, rather than conceding it to Fairland’s skills.

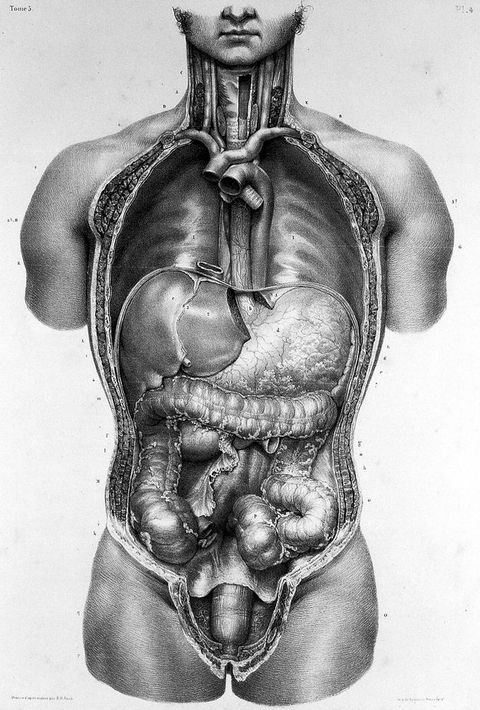

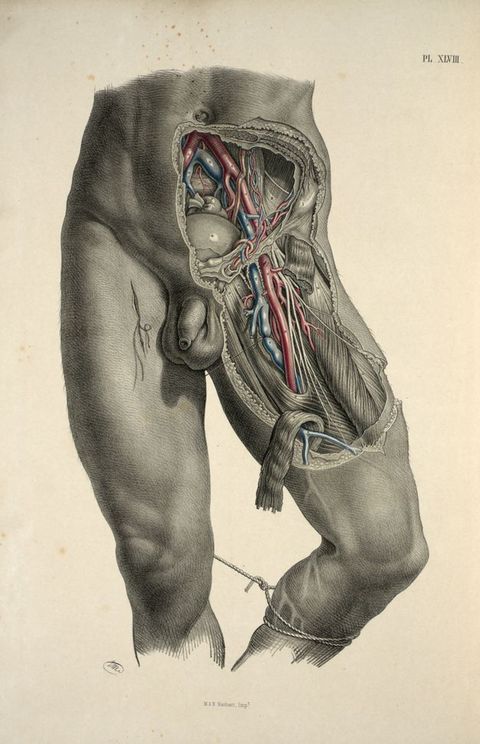

The complete Quain text for The Anatomy of the Arteries of the Human Body was, according to its title-page, published in 1844, but Maclise’s plates were printed in batches or “fascicules” beginning as early as 1840, with an anticipated total of thirteen.95 While there is no certainty over the extent to which Joseph Maclise was directed or constrained by Quain, a mature Maclise style emerged in the later plates, circa 1842–1844, when he came closer in feel to the Walsh/Fairland plates. Thus, in “Abdomen” (see fig. 12), Maclise explored a far richer and more sensual use of the lithographic chalk than seen in his earlier Quain plates. Here, to differentiate the complex, richly detailed textures of the organs, he exploits an extensive range of tonal values and touch that are arguably best suited to this complex subject. The cornucopia of bulging organs is animated by Maclise’s densely worked detail in the central ellipse, brought into “sculpted” relief under his left-to-right directional light and rendered by his superbly varied hatched modelling. Projecting into our space, this brilliant illusion of three-dimensionality is cleverly reinforced by the surrounding linear simplicity, where delicate black lines, stark in contrast to the white paper, evoke the linen swaddling the figure. Maclise drapes his white “cloth” theatrically over the figure’s left hip, to create a striking cast shadow from his well-endowed genitals, which hang pristine before his smoothly carved loins to draw the spectator’s eye. The genitals are beautifully rendered with contour hatch lines to echo and sculpt its plump forms. A deeply shadowed fold of fabric between his thighs is a metonymic device more commonly seen in female erotica to suggest the vulva.96 Clearly, by this date, Joseph Maclise’s style (as his commentators were to observe) owed less to his English contemporaries or the Bells than to Continental influences, whether Gros, Gericault, Delacroix, or Nicolas-Henri Jacob (fig. 23). And yet, direct comparison between Jacob and Maclise serves powerfully to demonstrate the painterly sensuality of the latter, as against the static formal restraint of Jacob, despite his “live” muscular figure. Maclise evidently looked more to the theatrical drama, sensuality, and mouvementé flamboyance of French Romantic art than to Jacob’s colder Davidian manner.

95

What we are witnessing here, I contend, is a stylistic development, an ever-growing confidence and skill in Joseph Maclise’s use of the lithographic medium, and with it a parallel shift to “live” figures, probably inspired by his work in Paris with Gerdy and his study of French art. In the preface to his own 1851 Surgical Anatomy, Maclise provides a clear scientific rationale to underpin this “new” style which, addressed specifically to the trainee surgeon, is after all intended as an aide to operating on live subjects.97 Superbly emotive in their lush build-up of chalk strokes, producing a richly modelled effect, without loss of precision in the detail, Maclise’s mature lithographs demonstrate an extraordinary control of his drawing mediums. His first plates for Quain, then, are less clearly personal: the scrawny unidealised body in Plate 2, “Neck and thorax” (see fig. 22) is stylistically closer to the Bells, particularly to John Bell (see fig. 4). Maclise’s figure looks very dead: a worn old man emaciated by a lifetime of hunger and work, and typical of the actual corpses available for dissection (see fig. 2). Maclise soon abandoned this abrasive Bellsian style. By Quain Plate 51 (see fig. 12), especially the intestines, his complex lighting includes highlights, reflected lights, and lustre to suggest moist malleability and vitality, the very textures of the different organs. The degree of Maclise’s obsession with precise observational detail—or the appearance of it—is seen here in the glistening entrails where even an overhead window is apparently reflected. Another glossy bar of light cast on the firmly straight (circumcised?) penis affirms its solid bulk, its tantalising hint of tumescence.98

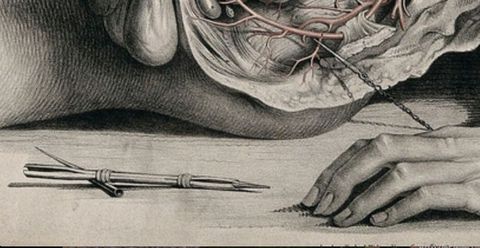

97Sight, Touch, and “Appendages”

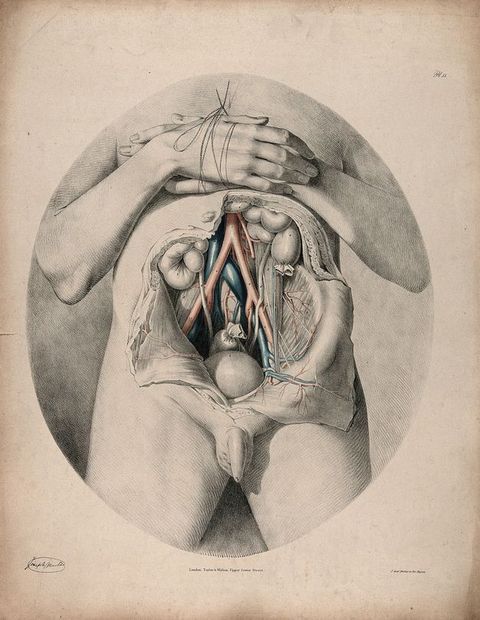

In Quain Plate 51, Joseph Maclise also exploits contrasts of “finish” (see fig. 12). A schematic left hand dissolves into drapery, in contrast to the beautifully resolved right hand and muscular arm, held effortlessly above the open and extravagantly baroque abdomen by a delicate twist of bandage. These are not the hands of a labourer or manual worker. In Maclise’s Plate 55 for Quain, both arms are folded across the chest, and again hands play a central role (fig. 24). Unmistakably youthful, this figure is verging on puberty. Although, echoing the subject matter, an oval format is common for the trunk in artistic anatomies, here, distinctively for Maclise, this beautiful boy-man is tenderly “framed” in an encircling ellipse reminiscent of rococo portraiture—and lithographic portraits. This figure has youthful genitals and the palest “girlish” skin. Maclise is remarkable for his close observational attention to skin texture and tone from a wide range of ethnic origins and ages, which, thanks to his extraordinary skills in life drawing and lithography, he is able to represent so persuasively in black and white. Combined, these qualities ensure the “truth” and legitimacy of his images, convincing the viewer of a scientific authority based in extensive comparative (human) anatomy, while simultaneously delighting the voyeuristic eye.

Differentiating the physiology of the senses from their cultural associations (if this is indeed possible), Sander Gilman observes that “[t]o comprehend the social construction of ‘touch’ and its relationship to sexuality, we must take into consideration the fact that the representation of touch is always in the realm of another sense, that of sight”.99 Elaborating this idea, he argues:

99100Thus the status afforded sight and touch, most often considered the highest and the lowest of the senses, is not random. These two senses are inexorably linked within the social construction of their history, just as they are linked within the internalized construction of the erotic gaze.100

Distinguishing the social construction of “good” and “bad” touching, Gilman suggests that the touching of the self is a “powerful homologue” for the touching of a same-sex Other—a touch electrifyingly visible in Maclise’s surgical anatomies where, in addition to penises, hands play a central role. In the majority of his plates, neither appendage was strictly necessary. Yet Maclise stressed in his preface regarding (and justifying) his “novel treatment” of anatomical figures for the surgeon, like the dashingly vigorous model in “location of the viscera” (see fig. 16): “I have […] left appended to the dissected regions as much of the undissected as was necessary”.101

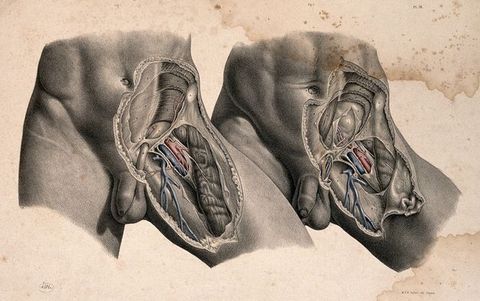

101In a series of dissections of the groin on standing figures, Maclise first presents a single exquisite model. Quite gratuitously overexposed from the ribcage to below the right knee (see fig. 11), he empowers this model with a more confident homoerotic self-display and panache than can be found even in dedicated “artistic nudes”, like Émile Bayard’s (1868–1937) photographic “Nus masculins” in Le Nu esthétique or those of Wilhelm von Gloeden (1856–1931) (fig. 25).102 In Maclise’s plate, the figure’s right leg takes the body weight, while the left is raised to the side, knee bent, the better to expose the dissected groin. This is a bronzed Athenian god of a figure, his superb athletic form and firm flesh smoothly rendered, muscles catching a light angled to accentuate their perfection. Hairless almost throughout, in the manner of a scraped Greek athlete, like Lysippos’ Apoxyomenos, this trope makes explicit reference to Hellenic homosexual culture, or the modern Turkish bath, to a knowing Victorian male audience (fig. 26).103 Maclise marks a modern masculinity in discreetly drawing attention to his model’s testicles, where minutely observed pubic hairs stand out against the white of the paper. The model’s hand introduced here in Plate 16 (1851) (see fig. 11), if more “work-reddened” and meaty than that for his Quain Plate 51 (see fig. 12), is again eloquent, evoking the sense of touch and of self-touching between the index and second fingers and again on his thigh.104 This immediately recalls Gerdy and his artist Maximilien-Félix Demesse, whose Plate 3 has the same hand, the same touch (fig. 27).105 The fact that the figure holds a ball in his hand (cue “athlete”) is barely perceptible in this plate (compare with Gerdy’s diagram and Plate 1, figs. 15 and 17). Instead, the eye lingers over whether his finger and thumb touch, or do not touch, the flank of his own buttock. Maclise undoubtedly knew Gerdy’s Anatomie des peintres, and he probably knew Demesse himself.

102

In Plate 26 of Maclise’s Surgical Anatomy (1856 London edition), this figure is transformed, reproduced landscape on the sheet, cut off at upper thigh; yet, the eloquent hand remains, as do the tiny pubic hairs on the scrotum, along with new anatomical detail: on his right thigh, Maclise provides the surface appearance of the femoral vessels dissected on the left leg. The model’s full vertical splendour returns in Plate 48 (1856; see also Plate 47 in the 1851 edition): the same pose but with hand and drapery omitted (fig. 28).106 Instead, there are other, different frissons. A hanging slab of muscle echoes the angle and dangle of the penis; the bent left leg is restrained below the calf, for once the rope shown digging into flesh, tautly tied for no apparent reason and to nowhere we can see. On this leg, the indication of surface veins below the skin continues beyond the dissection on to the thigh and calf; yet only on a live body in which blood is circulating would such raised veins or arteries be expected to occur. On both sides of the ligature restricting the femoral vein in the dissection itself, there is a lumpy swelling of its “contents” (despite nearby vessels being severed); the similar “tourniquet” roping of the calf would arguably result in a swelling above it of the arteries rather than the veins in a living subject.107 This olive-skinned flesh characteristic of the preferred Italian artists’ models of the period also sports a suture to the right leg. Seen first on the inner thigh of the Black man (1851) (fig. 29) and later recurring sutured, here the sutured incision is replicated on a “white” man. Highly evocative/provocative and exquisitely drawn, the thread of this apparently subcutaneous suture is left hanging from the sewn wound, casting its own delicate shadow.108 Pleasure and pain again: secret cuts and scars give authenticity and human frailty to perfect beauty.

106

Maclise’s Plate 18 in Surgical Anatomy (1851) extended this theme into coupledom (fig. 30). Close-cropped, he focuses in on a series of groins of two overlapping figures. Almost line dancers in a cabaret or an anatomical striptease, each dissection reveals deeper and different layers of component organs, the veins and arteries picked out in watercolour. And, of course, the acutely observed and distinct genitals: all different, each carefully delineated. Thus, posed alike, these two, well-built males contrast: on our right, a mature manly physique, darker skinned with a hint of ageing flesh on the muscle; on our left, narrow-hipped and lithe, a firm-bodied young blood. The older figure pushes up against the younger, his genitals suggestively touching the thigh of the younger model. In Maclise’s 1856 London second edition, with its smaller sheets (52 x 34 cm), the two figures are reduced and slightly cropped in two successive landscape sheets showing the incrementally deeper dissections (Plates 27 and 28). Two further plates of paired groins illustrate inguinal hernias, the figures placed side by side, not touching (Plates 29 and 30).109 There seems here in Maclise no intimation of, no concession to, the rising public anxieties at this period over moral probity, where even medical images might be subject to censure; this resulted, in 1857, in the Obscene Publications Act that sought to define and police the immoral power of the libidinous gaze.110

109

The Lubricant

Lithography oiled the wheels of dissemination. And of course, unlike an incised or intaglio medium, lithographs can be almost indefinitely reprinted from the original stone without wearing out, or rather wearing down, as happens—with an attendant loss of definition—in etched or engraved printing; hence, this planographic method is quite distinct, more economic, and direct. Lithography depends upon the oily printing ink adhering only to the areas of the stone marked by the artist’s design in waxy lithographic crayon, giving effects like chalk or pastel, or with “tusche”—the liquid waxy variant which can be applied with pen or brush—to achieve a distinctively ink or watercolour effect.111

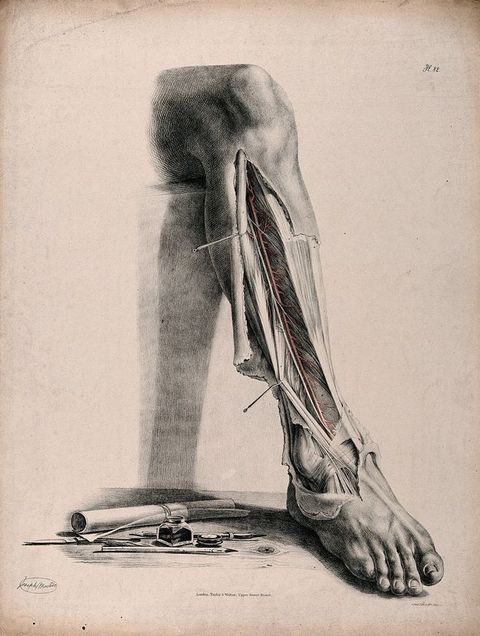

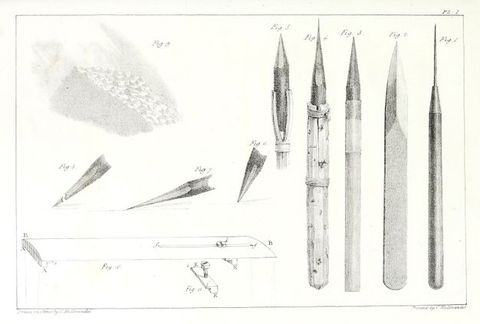

111Maclise principally uses the lithographic crayon, mirroring the effect of black chalk drawing. Marking his professional terrains in his lithographs for Quain, Maclise advertises his skills as both artist and surgeon-anatomist, self-consciously positioning exquisite still lifes of his tools alongside the dissections. His draughtsman’s tools: a roll of paper, a porte-crayon, knife, quill pen, and a bottle of ink (or lithographic tusche), lie at the foot of a dissected leg in Plate 72 (circa 1844) (fig. 31). In the lateral dissection of a female bladder and reproductive organs, Plate 59 (circa 1842–1843) (fig. 32), Maclise’s curved surgical scissors (a feminine tool?) eloquently reinforce the curve of a smooth-fleshed buttock, so plumply rounded it appears not to be load-bearing. In a second lateral dissection (male), Plate 60, a phallic porte-crayon awaits the cadaver’s hand (fig. 33). A disembodied hand in Quain, Plate 43 (fig. 34; see also fig. 35, which shows the porte-crayon among the essential tools of the lithographer), gestures eloquently to the interlocked tools of the artist-anatomist: a loaded porte-crayon rests on tweezers and a small blade or scalpel. In Plate 44, the “corpse’s” hand is wittily poised beside the surgeon-anatomist’s threaded curved needle, a specialist wood-handled flesh-hook and probe(?). For Maclise, all the tools of his trades included in his lithographs served as reminders both of the expert human touch of the specialist entailed in this multilayered work, and of the work’s “objective” scientific basis in observation; it was, as William Hunter named it, the “mark of truth”.112 It is for Maclise, when working under Quain’s direction, simultaneously the young artist-surgeon’s calling card; indeed, in Plate 43, the tools appear immediately above the artist’s signature (see fig. 34). Yet, equally, in his play on tools and cadavers, Maclise is making macabre visual puns that border on the knowing dissection-room prank: in-jokes which, to the aficionados of anatomy were a key feature of this “rite of passage”.113 By the time of Joseph Maclise’s solo publications, especially the major Surgical Anatomy (1851), his skills were famous: with his own authority stamped on the title-page, there was no longer the need to publicise his dual expertise.114

112

Indeed, Quain could be a patronising patron. In the 1844 preface to his atlas, The Anatomy of the Arteries of the Human Body, Quain noted with clinical understatement that although his friend and associate Joseph Maclise was first and foremost an “anatomist and surgeon”, his (eighty-seven plates of) “drawings will, I believe, be found not have lost in spirit and effect” as a result. The lithographs were initially available in seventeen unbound fascicules produced between 1840 (when on 19 December the first issue was reviewed in the Provincial Medical & Surgical Journal) and 1846, when a subscription appeal for five hundred bound volumes appeared in The Lancet on 31 October.115 Quain emphasised his requirement that Maclise “carry out my views as to the delineations”: his lithographs were to follow Quain’s directions. The atlas’s title-page clearly specifies what Maclise undertook: “The Drawings from Nature and on Stone by Joseph Maclise Esq. Surgeon”—not only did he make the initial anatomical drawings, we are told he also drew them on the lithographic stone.116 This work was more typically undertaken by draughtsmen-designers employed by the lithographic printers, usually overseen by the original artist and/or the anatomist-surgeon. Yet evidently, in Maclise’s case, his desire for authority and the integrity of the work meant he drew the stones himself, and his style is highly characteristic throughout his illustrations.117 The effort was certainly worth his while. For the 1840 reviewer, Joseph Maclise “evinced artistical talent of the very highest order”; “brother to the famous painter of that name”, Joseph’s lithographs “completely overshadowed” Quain’s confused text. Significantly given Joseph Maclise’s Paris stage and artistic interests, his lithographs “bear comparison with any of those splendid specimens of anatomical drawing, so abundant on the continent but … so rare in our own country”.118 The reviewer was doubtless alert to the outstanding contemporary work of Jacob in Paris for Jean-Baptiste-Marc Bourgery’s (1797–1849) Traité complet de l’anatomie de l’homme comprenant la médecine opératoire (1831–1854), already in production when Maclise was living there.119 The 1846 Taylor & Walton subscription to Quain’s The Anatomy of the Arteries of the Human Body also offered the entire run of the then “eighty-seven drawings” in unbound portfolio form: in imperial folio, “an oblong, averaging about two feet square, the figures thus being the size of life”. The publishers stressed that “the large size of the stones renders it difficult to preserve them uninjured …” thus,

115120they design to print off as many copies as are wanted by subscribers, and then to efface the drawings from the stones, in order that the plates may not be hereafter produced in a less perfect manner, or the pecuniary value of the work to the purchaser be lessened by a subsequent flooding of the market with an indefinite number of copies, worn or not.120

Equally, however, it is clear when comparing prints from different editions of Maclise’s Surgical Anatomy that there are subtle variations in interpretation when a stone was redrawn, and re-sized, not necessarily by Maclise himself. The Philadelphia editions, in a much weaker hand, were copied onto stone in America.121 Abstracted stylisation accretes too through repetition from the flat, where knowledge and sight of the original is lost. There are slight differences, for example, in the twist of the torso and the muscular detail in the dissection figures of “Thorax and abdomen” between the 1851 and 1856 editions (Plates 12 and 22, respectively); more thigh is visible in the 1851 print while, in the 1856 print, the contrasts of light and shade in the modelling are more pronounced.122 Differences are particularly clear in comparing the drawings of a Black man’s head in the 1851 and 1856 London editions (figs. 36 and 37). Whereas the two “white” heads in this comparative anatomy sheet are relatively similar, differing just in subtle physiognomic details and in 1856 a reduced light–dark contrast, the treatment of the two Black men’s heads—notably in the handling of the hair, but also in the appearance of the skin—suggests the later draughtsman had no personal knowledge of Black people. In the 1851 print, the intense light-absorbing properties of a matt blue-black skin, and the tightly curled hair are beautifully evoked but, in the 1856 print, not only is the head physiognomically more brutish but also the hair is rendered like burnished, light-reflective bronze studs, or a scaly helmet—an effect heightened by the raking overhead light that also gives areas of skin a glistening sheen more common on Maclise’s white flesh. It is probable these lithographs in the second London edition (1856) were drawn directly on stone—not by Maclise himself but by expert “copyists”.

121

Whether as a naturalistic “mark of truth”, a sentimental gesture of shared humanity, or an erotic sign, Joseph’s inclusion of the earring hole, too, meticulously denoted in the lobe of his Black model (fig. 38) is equally a signifier of the man’s social status and profession: in London at this period, most Black men were freed or escaped slaves employed mainly as sailors, and earrings were associated with this profession.123 Commonly a captain’s gift to a young sailor on first crossing the equator or rounding Cape Horn, the gold hoop was both a talisman against drowning (among other things), and a bond to cover a dead sailor’s transport home and funeral.124 There is thus a narrative eloquence here to the Black man’s empty earring hole, and tragic irony in his “appearance” on the dissection slab. The bodies available for medical dissection might as often be female as male, and yet in visual representation the “Body” was essentially male. Significantly with respect to the racialised body (and this is apparent in Maclise’s anatomies, see figs. 29, 36, 37, and 38) and despite the contentions of some comparative anatomists and proto-anthropologists, dissection prompted others to question theories of an embodied racial difference precisely because beneath differently pigmented skins the same flesh and corporeal structures were present.125 In Europe, the appearance of Black people or “outsiders” like Jews in anatomical atlases and painting alike might suggest a negatively racialised interest in comparative anatomy, yet perhaps paradoxically can equally signal the work of radicals: abolitionists, non-conformists, and liberal thinkers like Gericault, William Etty (1787–1849), and Joseph Maclise himself.

123

Appended

Just as in the burgeoning series of “aesthetic nude” photographs notionally intended for artists’ use, or the artistic studies of beautiful well-hung Sicilian youths posed by photographers like Baron Wilhelm von Gloeden (see fig. 25) forty-odd years later, in his Surgical Anatomy, Joseph Maclise left particular parts more exposed than others—notably, as we have seen, hands and the male external genitalia.126 The viewer’s eye is inexorably drawn in particular to his penises, their sheer variety and myriad beauty, their personal portrait-like individuality. Given his large-scale, almost life-size figure plates, their impact is all the greater. Verging on the obsessional, every conceivable shape and state of vigorous male genitalia—apart from erect—are lovingly delineated, providing his readership with a veritable taxonomy of healthy sexual organs.127 Indeed, visibly more full-blooded and generous than those found on neoclassical nudes, Maclise’s penises were barely constrained by the bounds of Victorian propriety and convention. Although recognised as “high art” and as skilful as those of his brother Daniel, arguably Joseph’s naked male figures could only be accommodated within the homosocial world of medicine.128 Unmistakably erotic in feel as in sheer penis count, genitals are often the central focus between assertively splayed thighs or “man-spread”. Far from evoking death, Maclise’s life-size male figures embody vital manly virility, the “absent” erect penis displaced in the muscular verticality of his models’ superbly taut polished flesh: the rippling athletic thighs, arms, shoulders and, indeed, in the eloquent hands.129

126The particular advantages of the lithographic medium, its expressive qualities, and approximation to the intimacy of chalk drawing, plus the wealth of rich texture and detail it offered to such a consummate draughtsman, its subtle direct and indirect lights, reflections and shadows both attached and cast, result in an extraordinary variety of sensual, erotic delights for the libidinous eye. Paraphrasing Michael Hatt’s analysis of Haymo Thornycroft’s rural Mower, Maclise’s well-endowed, urban guardsmen, sailors, and labouring bodies have a kind of masculine muscle that could be looked at and enjoyed overtly in a medico-anatomical narrative, and also as “phantasmatic figure[s] to be consumed covertly in an erotic one; the very process of looking, of contemplation, is one which submerges this paradox”.130 Given the medical context and function of Maclise’s lithographs, their artistic quality and scale demonstrate the artist’s own pleasure in the male body, a pleasure with a more than chance resemblance to pictorial homoerotic pornography—and similarly a resistance to normative Victorian heterosexuality. Yet, covert erotic looking in the domain of the anatomy room, or the private library, is a very different affair to that in a public art gallery or Westminster Halls. According to the Obscene Publications Act of 1857, it was not possession as such of erotica that was considered dangerous but rather its uncontrolled production and dissemination among the ill-educated masses, threatening to distract and weaken workers, and corrupt the innocence of youth. Working privately from live rather than dead models, Maclise could sate his own homoerotic desires (whether lived out or phantasmic) for the male military body: a passion he shared with his brother Daniel. Creating medical anatomies at such a high level of aesthetic skill meant Joseph Maclise observed and drew the best male models as a fine artist, while at the same time being licensed as a surgeon-anatomist to explore intimate bodily terrains forbidden to Daniel as a painter of heroic military history.

130Like their anatomical artists, such lithographic plates travelled widely. Their relative cheapness—especially in individual fascicules of a few plates—meant that, like pornography, they were readily available and doubtless circulated within educated circles well beyond their primary audience of medical students and surgeons. Under the umbrella of medical science, these superb lithographs offered their all-male viewers, whether in London or Paris, Boston or Philadelphia, a safe space to enjoy their libidinous gaze on exquisite male bodies, modern ideals of athletic masculinity, without fear of persecution or censure.

Acknowledgements

I would like warmly to thank Keren Hammerschlag for her kind invitation to contribute to this major British Art Studies project, and for her comments on my text. My thanks also to the two BAS reviewers for their close reading plus their astute and helpful feedback. Marcia Pointon generously read an earlier version of my paper and gave me invaluable advice on it. I am very grateful too, to the incomparable William Schupbach at the Wellcome, who answered all my obscure queries during library lockdowns in 2020; Michael Sappol was also very kind in answering my questions and sharing his research. Irish medical historians Davis Coakley and Clive Lee have also generously shared their research and networks with me, without which my knowledge especially of the Cork anatomy fraternity would be greatly impoverished. The BAS project editors, especially Baillie Card, and Maisoon Rehani who has organised the illustrations, deserve my grateful thanks for their hard work, patience, and invaluable input. I am also indebted to all those individuals and organisations that supplied the illustrations.

About the author

-

Professor Emeritus Anthea Callen FRSA is an art historian and painter with a long-standing interest in interdisciplinary material culture. Widely published and consulted, Callen is a world renowned specialist on Impressionism and the history of nineteenth-century artists’ materials and techniques, publishing the definitive study, The Art of Impressionism: Painting Technique and the Making of Modernity in 2000 (Yale University Press). Her latest book in the field is The Work of Art: Plein Air Painting and Artistic Identity in Nineteenth-Century France (Reaktion, 2015). As a feminist, she has long been interested in sexualities and the visual representation of the human body: in The Spectacular Body: Science, Method and Meaning in the Work of Degas (Yale University Press, 1995), Callen analyses social and pictorial constructions of the female body, and her recent work on Degas (for the 2021 São Paulo MFA Degas and Dance exhibition catalogue), focuses on pigments, paper, and skin. Her major new book Looking at Men: Art, Anatomy and the Modern Male Body (Yale University Press, 2018) examines the interdependent visual cultures of art and medicine to study the modern male body, masculinity, and power circa 1780 to 1920.

Footnotes

-

1

Joseph Maclise, Preface to Surgical Anatomy (Philadelphia, PA: Blanchard and Lea, 1951), vi. The first fascicule of lithographs of Joseph Maclise’s Surgical Anatomy, first London edition (London: John Churchill, 1851) were advertised in February 1849, see “Miscellaneous”, Provincial Medical & Surgical Journal (1844–1852) 13, no. 3 (7 February 1849): 84. ↩︎

-

2

See Mechthild Fend, Fleshing out Surfaces: Skin in French Art and Medicine 1650–1850 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2017), 216, discussing Jean-Galbert Salvage, 1772–1813. ↩︎

-

3

On women printers and printmakers in the nineteenth century, see Michelle E. Tusan, “Performing Work: Gender, Class, and the Printing Trade in Victorian Britain”, Journal of Women’s History 16, No. 1 (Spring 2004): 103–126; Anon., “Women Printers in the 19th Century”, International Printing Museum, https://www.printmuseum.org/blog/women-printers-in-the-19th-century; and Allison Meier, “Remembering Forgotten Female Printmakers from the 16th to the 19th Centuries”, Hyperallergic, 19 October 2015, https://hyperallergic.com/246077/remembering-the-forgotten-female-printmakers-from-the-16th-to-19th-centuries. ↩︎

-

4

Their Scottish Presbyterian father, Alexander, came to Cork with the Scottish Highlanders, settled and married there. ↩︎

-

5

Daniel’s life and painting career are well documented, whereas that of the less famous Joseph is patchy and oddly ill-known; it is strange that, despite their close intimacy throughout their lives, neither Daniel nor his biographers make more than passing reference to his brother Joseph. On Daniel Maclise, see W. Justin O’Driscoll, A Memoir of Daniel Maclise (London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1871); Richard Ormond, “Daniel Maclise”, Burlington Magazine 110, no. 789 (December 1968), Special Issue Commemorating the Bicentenary of the Royal Academy (1768–1968): 684–693; Nancy Weston, Daniel Maclise: An Irish Artist in Victorian London (Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2001); Peter Murray, ed., Daniel Maclise 1806–1870: Romancing the Past, exhibition catalogue, Crawford Art Gallery, Cork (Kinsale: Gandon Editions, 2008). On Joseph Maclise, see Davis Coakley, “Anatomy and Art: Irish Dimensions”, in The Anatomy Lesson: Art and Medicine, ed. Brian Kennedy (Dublin: The National Gallery of Ireland, 1992), 74–76. I am very grateful to Professor Davis Coakley for this and other references relevant to Joseph Maclise, and for introducing me to Professor Clive Lee, to whom I am also most grateful for his references; see, for example, his “Anatomies and Academies of Art II: A Tale of Two Cities”, Journal of Anatomy 236, no. 4 (April 2020); 577–587, DOI:10.1111/joa.13130. On the Maclises’ Cork circle, see also Davis and Mary Coakley, Wit and Wine: Literary and Artistic Cork in the Early Nineteenth Century (Peterhead: Volturna Press, 1975). ↩︎

-

6

On nineteenth-century anatomical conventions, see Janis McLarren Caldwell, “The Strange Death of the Animated Cadaver: Changing Conventions in Nineteenth-Century British Anatomical Illustration”, Literature and Medicine 25, no. 2 (2006): 325–357; and Martin Kemp, “Style and Non-Style in Anatomical Illustration: From Renaissance Humanism to Henry Gray”, Journal of Anatomy 216 (2010): 192–208. ↩︎

-

7

Clive Lee makes a similar point in his discussion of William Hunter’s various écorchés, in “Anatomies and Academies of Art II: A Tale of Two Cities”. ↩︎

-

8

Joseph Maclise had editions of his Surgical Anatomy, published in Boston and especially Philadelphia (1851, 1856, 1859); see Naomi Slipp, “‘It Should Be On Every Surgeon’s Table’: The Reception and Adoption of Joseph Maclise’s Surgical Anatomy (1851) in the United States”, British Art Studies 20 (July 2021), DOI:10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-20/nslipp. ↩︎

-

9

William Hunter’s Gravid Uterus is the most famous example; see Ludmilla J. Jordanova, “Gender, Generation and Science: William Hunter’s Obstetrical Atlas”, in her Nature Displayed: Gender, Science and Medicine 1750–1820 (London: Routledge, 1999), Chapter 11. On the history of printmaking and its vital cultural importance, see the classic text, William M. Ivins, Prints and Visual Communication (Boston, MA: MIT Press, 1969). ↩︎

-

10

On the Royal College of Surgeons, see “History of the RCS”, Royal College of Surgeons of England, https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/about-the-rcs/history-of-the-rcs/. See Cindy Stelmackowich, “Bodies of Knowledge: The Nineteenth-Century Anatomical Atlas in the Spaces of Art and Science”, Canadian Art Review 33, nos. 1–2 (2008): 75–86. ↩︎

-

11

On the symbiotic relations between art and anatomy, physiology and anthropology, see Anthea Callen, Looking at Men: Art, Anatomy and the Modern Male Body (London: Yale University Press, 2018), passim; see also Mary Hunter, The Face of Medicine: Visualising Medical Masculinities in Late Nineteenth-Century Paris (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2015). ↩︎

-

12

On the history of the Royal College of Surgeons (founded in 1800), and its origins in the trade guild and London Livery Company of Barber-Surgeons which, until 1745, held a monopoly on training surgeons, see Royal College of Surgeons, “History of the RCS”. For an overview of the history of medical training in the UK, see M.D. Warren, “Medical Education during the Eighteenth Century”, Postgraduate Medical Journal 27, no. 308 (1951), esp. 307–309, DOI:10.1136/pgmj.27.308.304; and Bernice Hamilton, “The Medical Professions in the Eighteenth Century”, The Economic History Review, New Series 4, no. 2 (1951): 141–169, DOI:10.1111/j.1468-0289.1951.tb00606.x. ↩︎

-

13

See notably Ruth Richardson, Death, Dissection and the Destitute (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2001); and Helen MacDonald, Human Remains: Dissection and its Histories (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2006). ↩︎

-

14

The text volume for Richard Quain’s Anatomy of the Arteries (1841–1844), is sometimes referred to as quarto, sometimes as octavo. It is noteworthy that the lithographic atlases were not hugely expensive, see discussion here. I am grateful to Keren Hammerschlag for drawing my attention to the direct reference to Charles Bell in Joseph Maclise’s Plate 66 for Quain. A book by ‘C Bell’ lies beneath a section of pelvis displaying the blood vessels that nourish the penis; it is unclear if this is intended as a compliment or is a ribald University College in-joke. ↩︎

-

15

Joseph Maclise, Preface to Surgical Anatomy, 1st edn (London: John Churchill, 1851), viii. By then linked to La Salpêtrière (nearby, in the thirteenth arrondissement and already noted for its syphilis specialism, later made infamous by the work of Jean-Martin Charcot and his Hysteria patients from the early 1870s), l’Hôpital de la Pitié was the largest hospital in France. ↩︎

-

16