Slade, London, Asia

Slade, London, Asia

Animating the Archive (Part

1)

Ming Tiampo

Liz Bruchet

Introduction

From its inception in 1871, the Slade School of Fine Art in London attracted artists from around the world. Slade, London, Asia: Contrapuntal Histories between Imperialism and Decolonization takes the Slade as a starting point for a global microhistory and a reimagined and refigured archive. This feature surfaces how the Slade functioned during the post-war period as a site of encounter, decolonization, and expression for overseas artists; it also presents archival records which illuminate how the Slade occupies a complex place in the global history of art education, art practice, empire, and decolonization.

This feature consists of two interwoven parts. The first is a narrative history in the form of an academic essay that conceptualizes and interrogates the Slade’s role as a transversal line, which at its points of intersection with other lines—such as those tracing histories of colonialism, decolonization and nation building, of concurrent institution building, or of modernist aesthetics—creates contrapuntal nodes, or complex sites of multiple entangled and resonating histories.1 The second part of the feature is this offering of an “animated” archive that brings together materials from multiple institutional and personal archives in Asia and the UK, presented in a manner that invites readers to consider them in a non-linear fashion. Throughout this feature, we build upon Edward Said’s use of the musical metaphor of contrapuntalism to address both the presence of empire in the metropolis and the construction of a transnational counterpoint with multiple voices and melodic lines in order to tune in to histories at the intersection of imperialism and decolonization.2

In this approach, the Slade is configured as a transversal line that links multiple histories from Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Indonesia, Singapore, Nigeria, Sudan, Uganda, Britain, and beyond. While we began with the focus on tracing connections between the Slade and artists and sites in Asia, the research evolved iteratively, and came to defy the parameters of the "London, Asia" project. Indeed, the documents showcased here have illuminated important alignments and transversals that extend beyond Asia, taking us to parts of Africa as well as parts of Britain beyond London. In this sense, these archival fragments also help us to position the Slade as one of many transversals and sites of relational comparison through which to analyse multiple colonial and postcolonial histories of art education.3

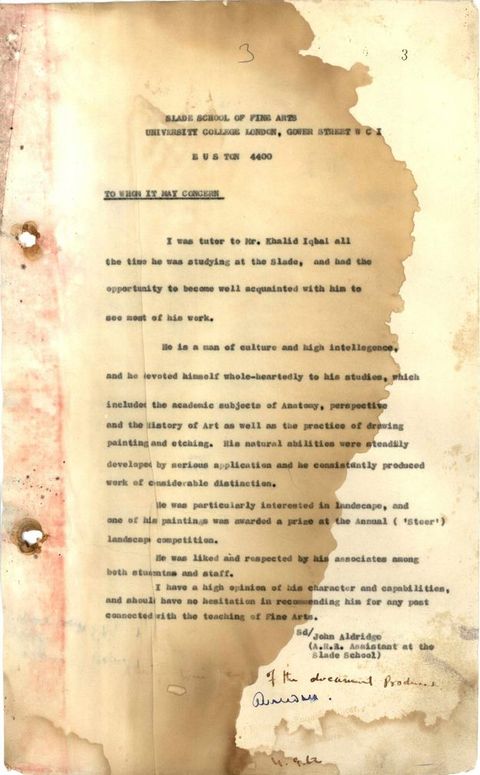

The constellations of records presented here also shine light on some of the many interconnected and difficult histories, visual languages, and pedagogical frameworks that emerged out of the Slade’s particular transnational context at the intersection of imperial, decolonial, and migration histories. Working through archival material with this framing, and reading them against and along their grain, has allowed us to understand and represent the Slade as an institution that contributed to, but did not fully determine, the formation of the artists who attended it. Many of the artists featured in this research were mid-career when they arrived at the Slade, and were often supported by scholarships or schemes designed to develop capacity for newly independent nations and construct Britain as a post-imperial power. The artists brought with them their own vocabularies, ideas, ambitions, and conundrums, contributing to the contrapuntal environment at the Slade. The records featured here convey artists as institutional subjects in which the Slade functions as an authoritative intermediary, as well as (auto)biographical figures, postcolonial interlocutors, actors, and visionaries.

The project has evolved from two long-term collaborative research projects: “Transnational Slade” and “London, Asia”. The collaboration activates an alchemy of archival studies and art history, opening up the field of research to new intersections, and enabling us to refigure the archives we draw on and co-constitute.4 Setting an aim to “animate the archive” foregrounds (an) archive(s) as the subject of activation and illumination. It suggests we are bringing to life what has passed. Yet archives, considered through archival studies, are not inert, nor solely concerned with the past; they carry agency and hold different affordances in the present. In this sense, through this research, we seek not to animate but rather to refigure the archive and assume that archives, in their plurality, are important subjects of study in their own right.5

Although our research has resulted in this initial publication with its own particular framing and moment of archival activation and authorship in a form akin to an exhibition, the collaborative ethos of the project has encouraged the sharing of archival knowledge in order to seed new research beyond the scope of this project. The journey has led us to an array of personal, family, institutional, and organizational archives (both formal and informal), as well as oral histories and research workshops. The open access, digital format of British Art Studies lends itself to embedding different types of records in a variety of formats, which provides opportunities to make visible the qualities and patterns of these records as they are distilled from different recordkeeping contexts and activities.

This is Part 1 of a two-part feature, which addresses the period from about 1945 to 1965; Part 2 will encompass the period from the 1960s to the 1990s, and incorporate material gleaned from upcoming workshops. The contrapuntal histories of art education presented here offer a global microhistory situated within the complex entanglements between imperialism and decolonization. They have also prompted reconsideration of ways to engage with, co-constitute, and curate a research archive in pursuit of this endeavour. We take the Slade as a starting point for exploration, but render it as a single melodic line in a polyphonic counterpoint. As such, these transversally linked and co-constituted histories provide new methodologies for writing the histories of contrapuntal modernisms, while also understanding art in Britain itself as the product of empire.

1The concept of transversals was first used by Tiampo to theorize the relationships between histories that are both parallel and linked through a third term. Ming Tiampo, “Slade, London, Asia: Intersections of Decolonial Modernism”, 10 November 2020, https://www.paul-mellon-centre.ac.uk/whats-on/slade-london-asia.

Edward Said, Culture and Imperialism (New York: Vintage, 1993), 51.

Shu-mei Shih, “Comparison as Relation”, in Comparison: Theories, Approaches, Uses, ed. Rita Felski and Susan Stanford Friedman (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013), 79–98.

Carolyn Hamilton, Verne Harris, and Graeme Reid, Introduction to Refiguring the Archive, ed. Carolyn Hamilton et al. (Dordrecht: Springer, 2002), DOI:10.1007/978-94-010-0570-8_1.

Anne J. Gilliland, Sue McKemmish, and Andrew J. Lau, eds., Research in the Archival Multiverse (Clayton, VIC: Monash University Publishing, 2016), http://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/31429.

I. Institutional Pathways and Documentary Trails

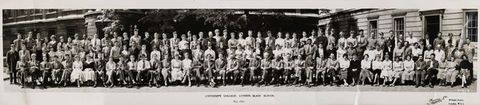

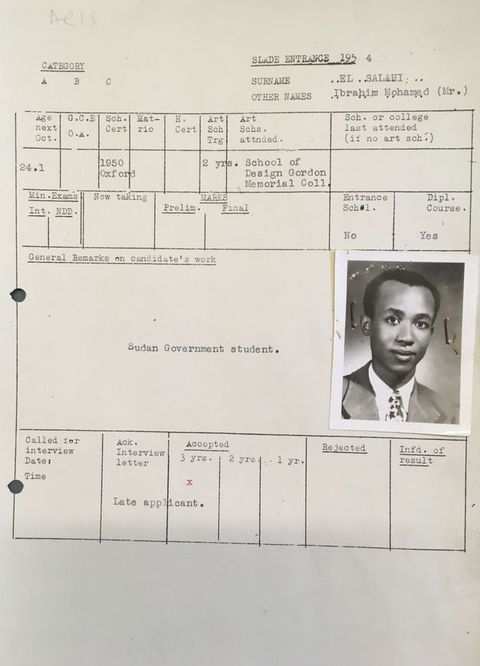

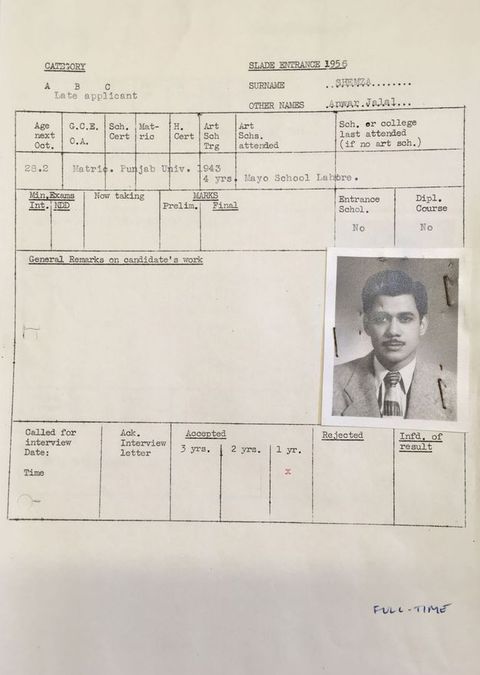

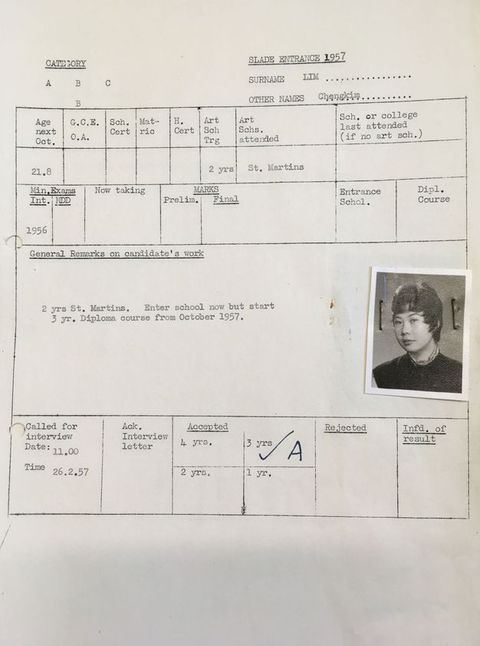

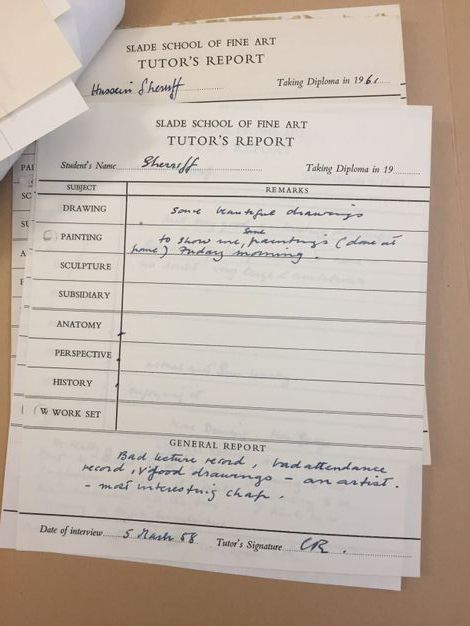

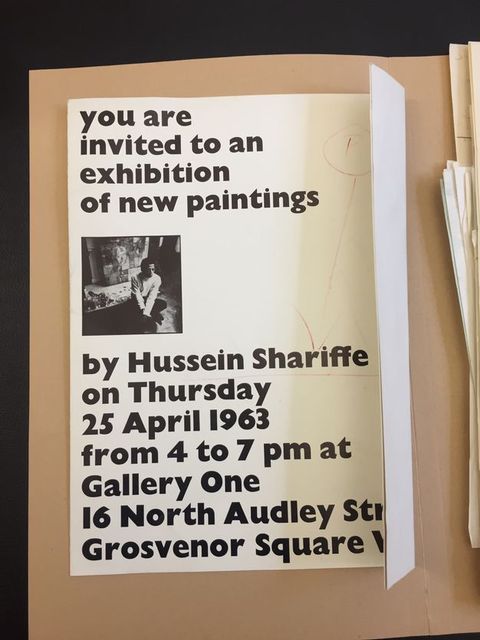

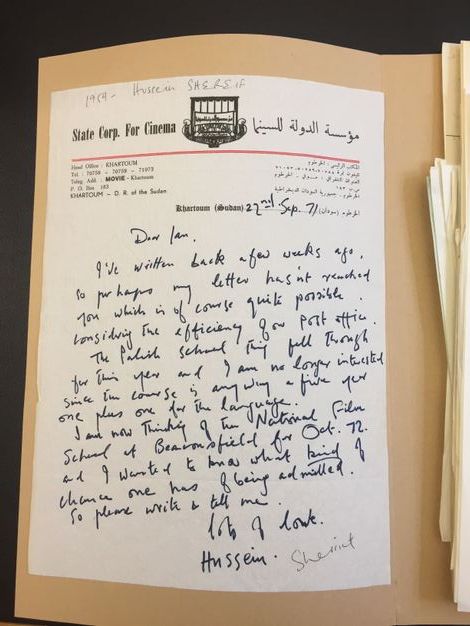

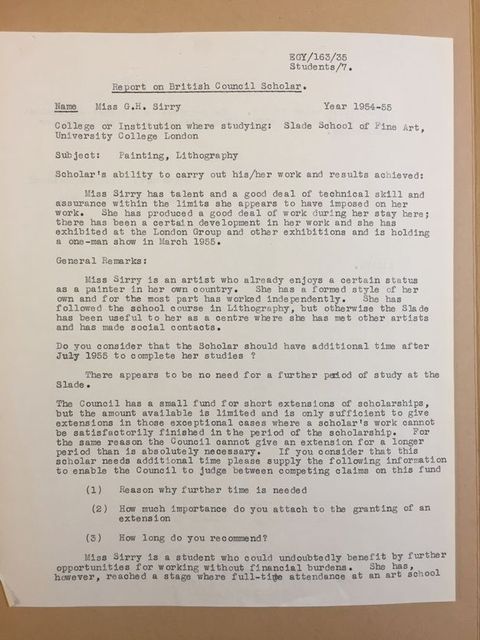

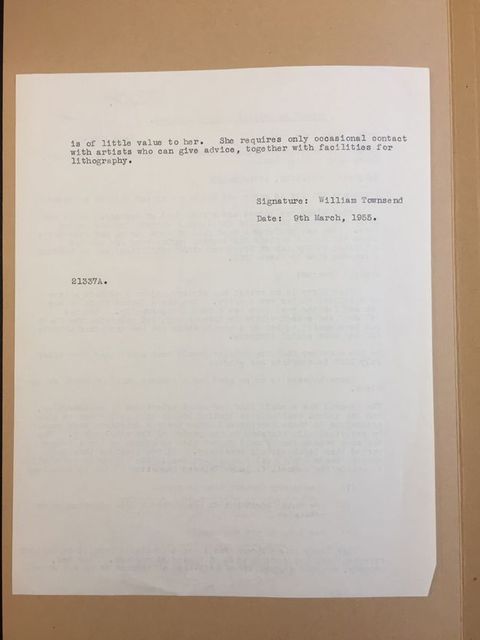

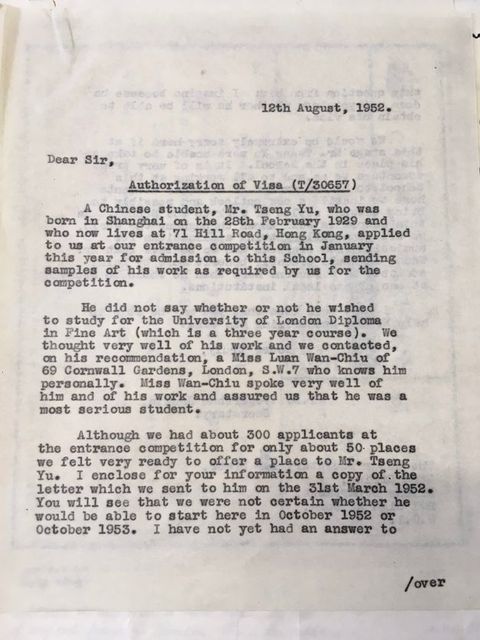

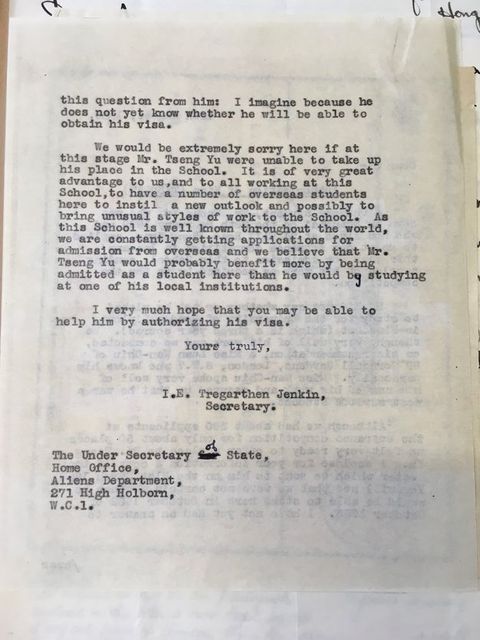

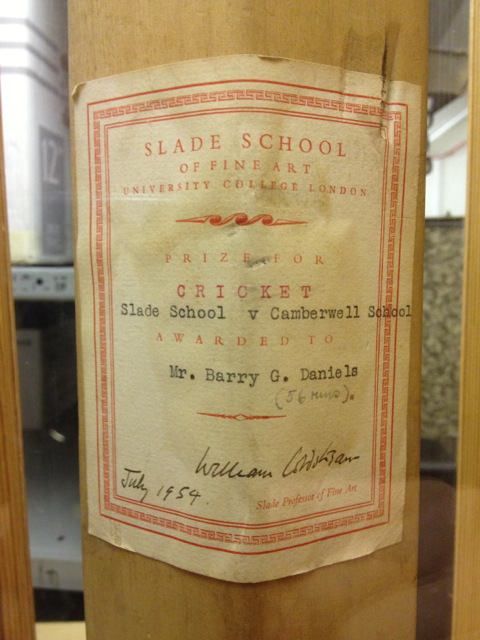

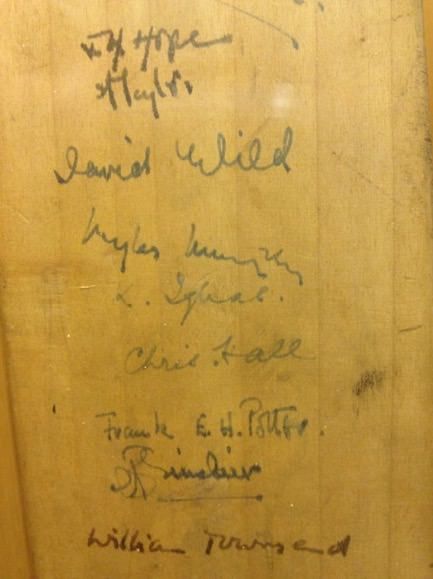

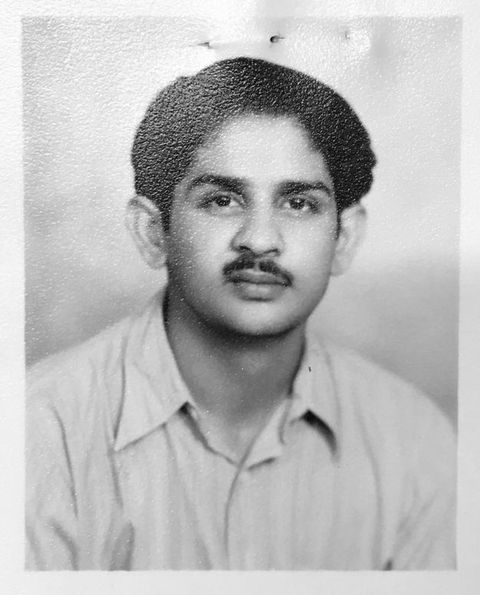

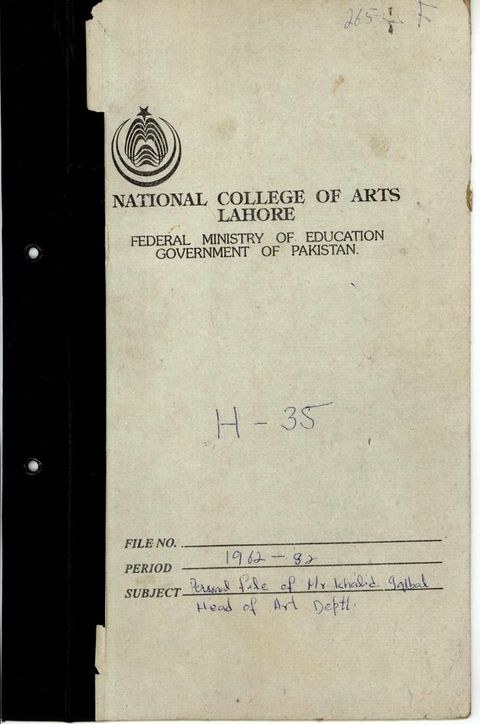

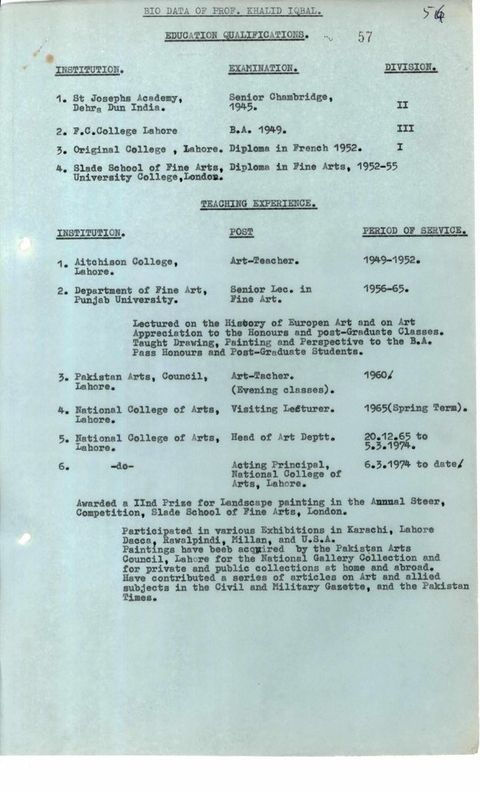

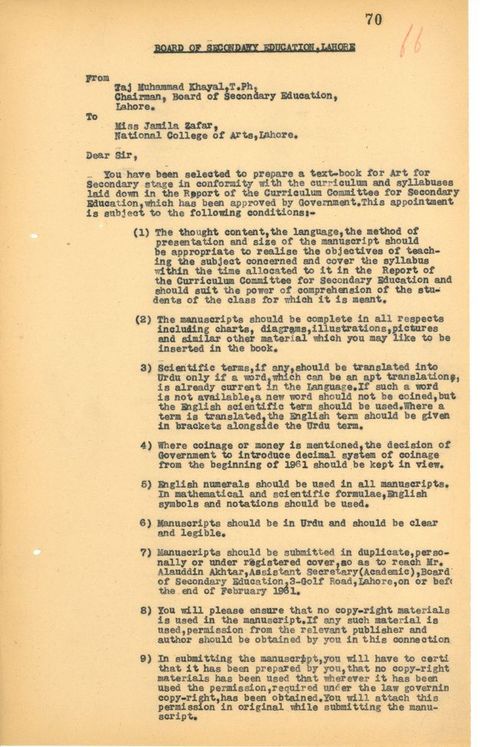

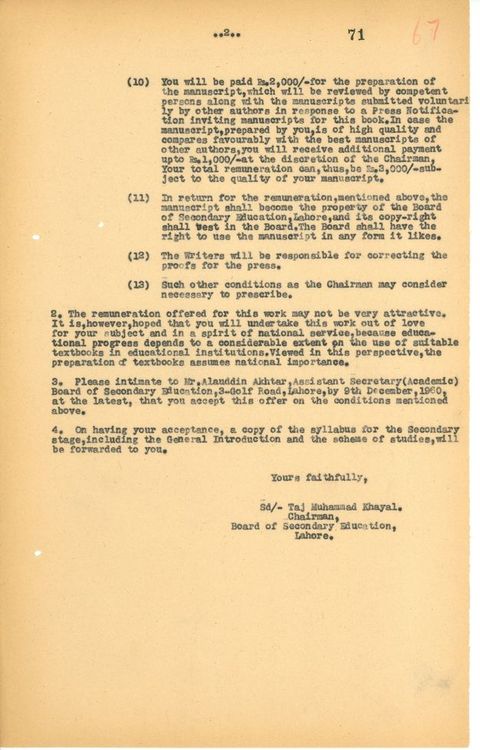

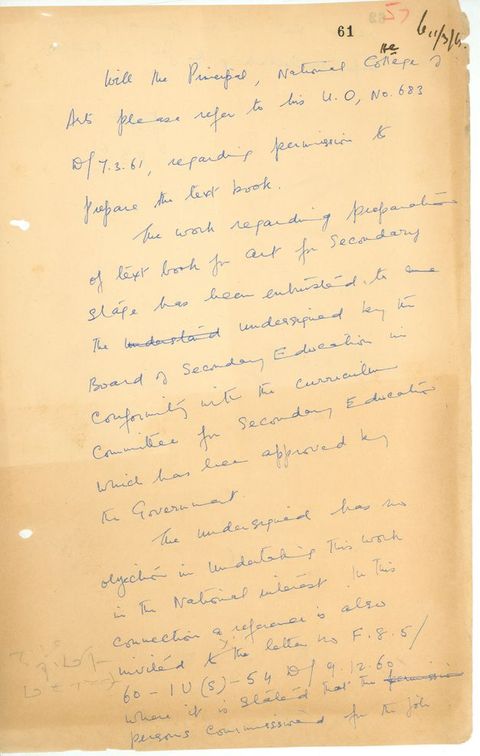

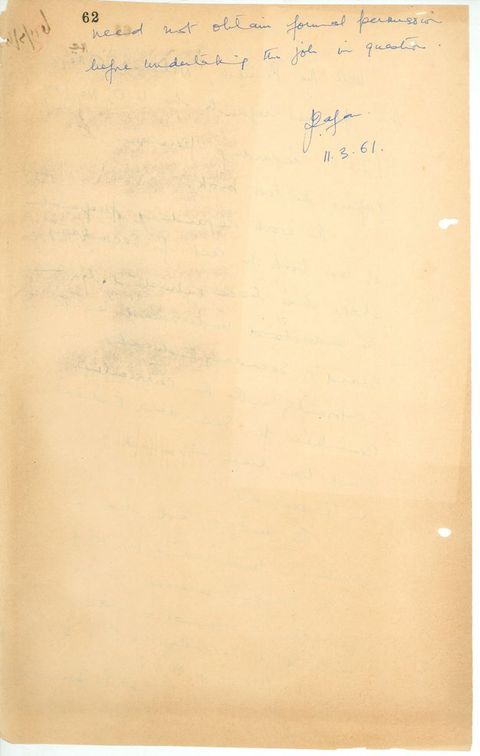

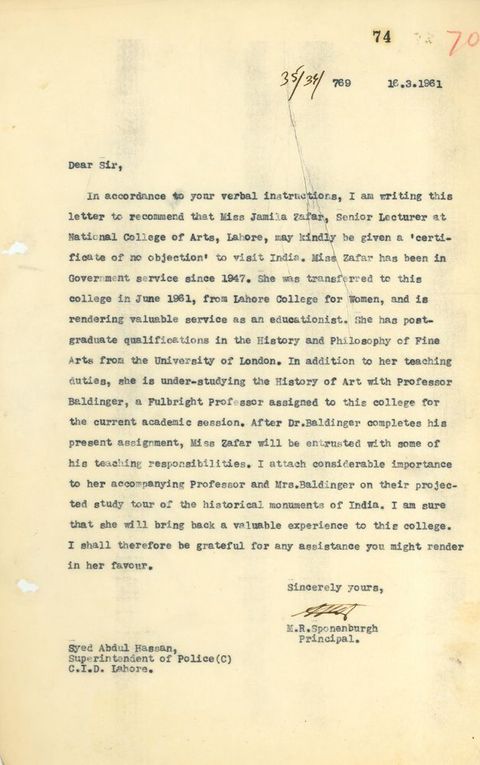

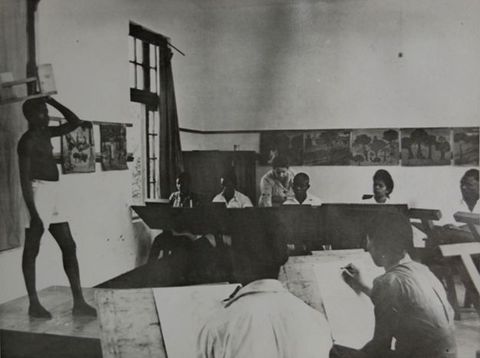

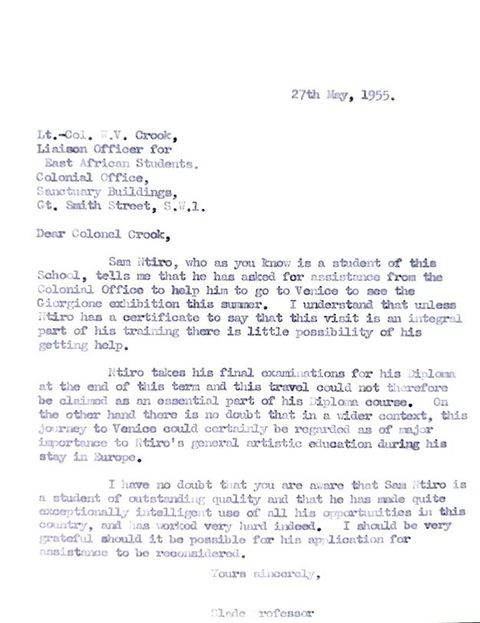

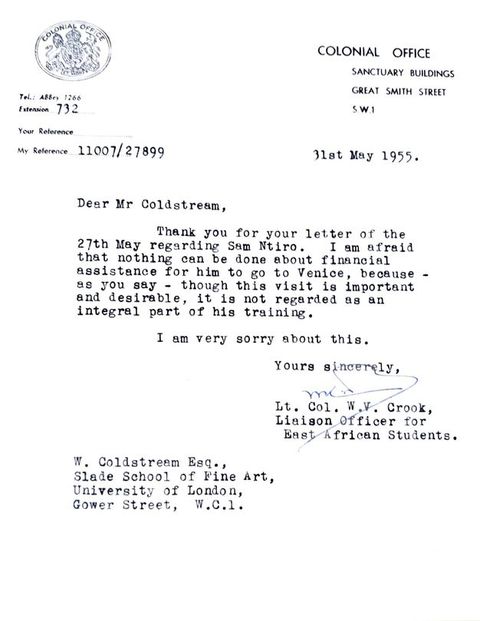

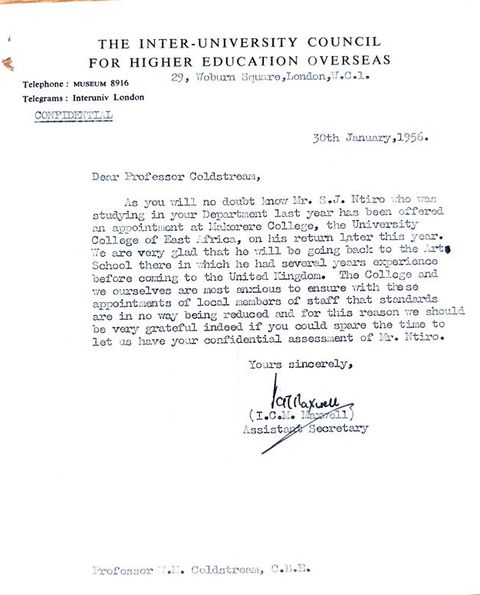

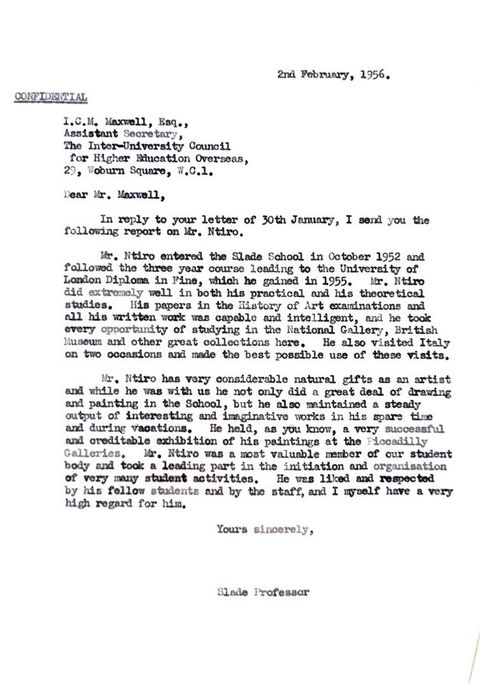

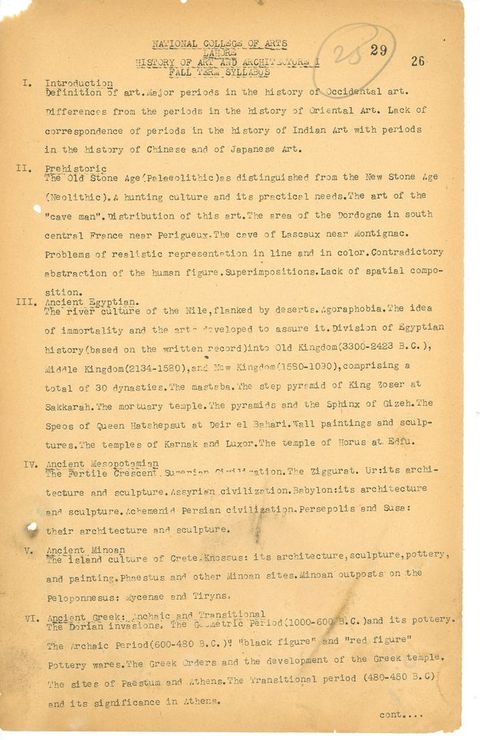

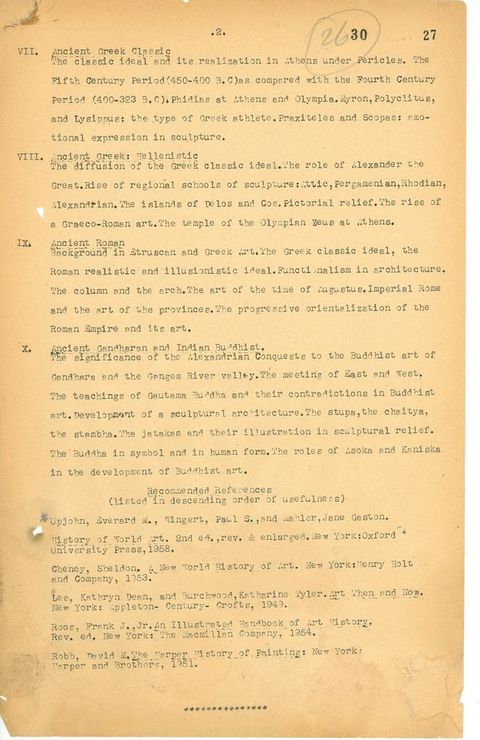

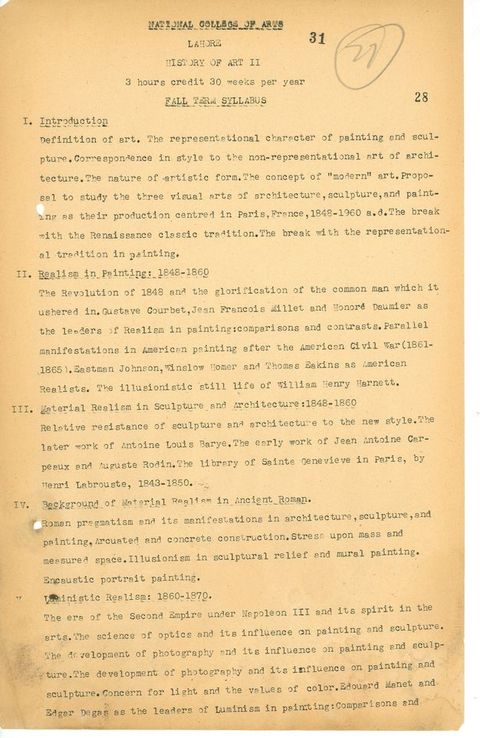

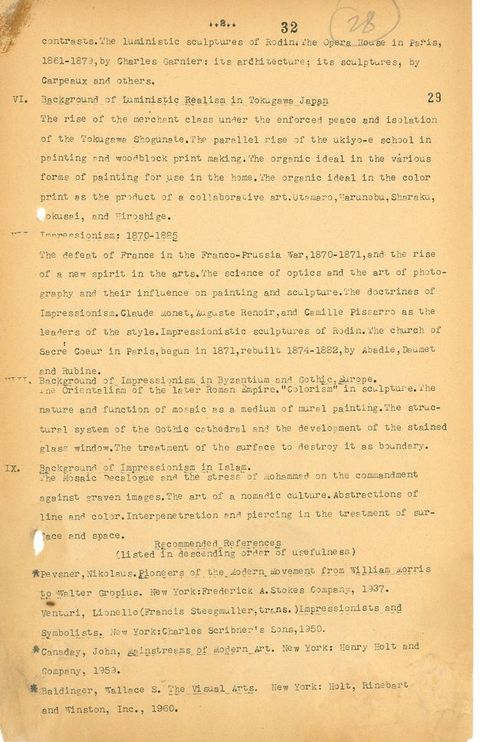

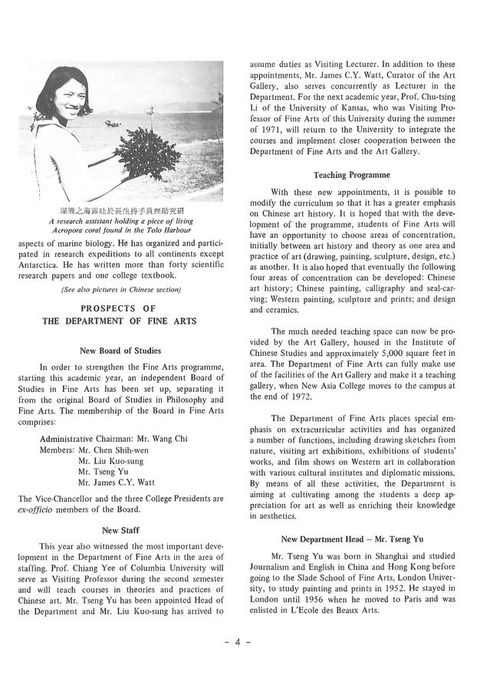

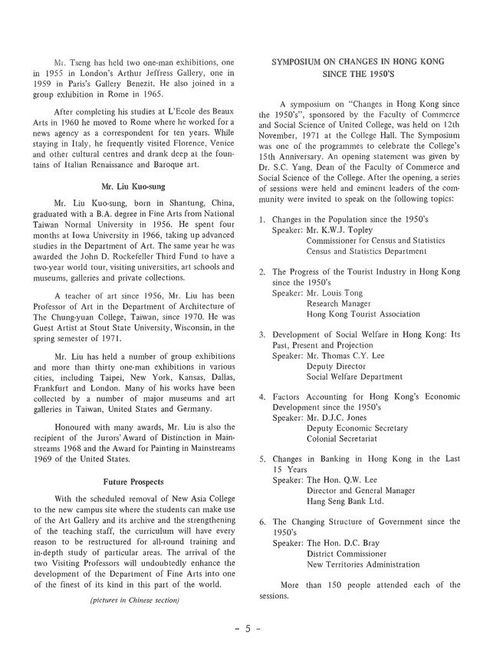

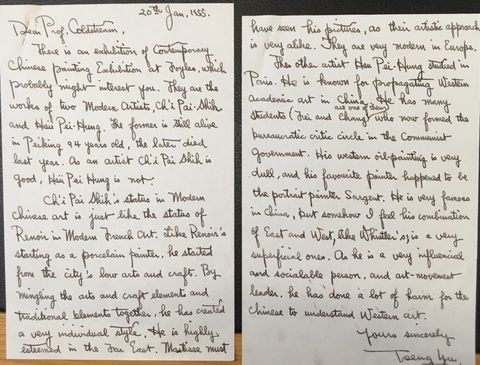

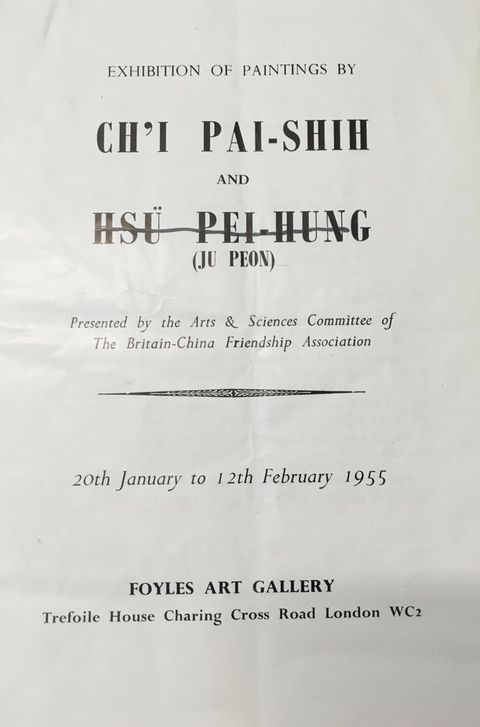

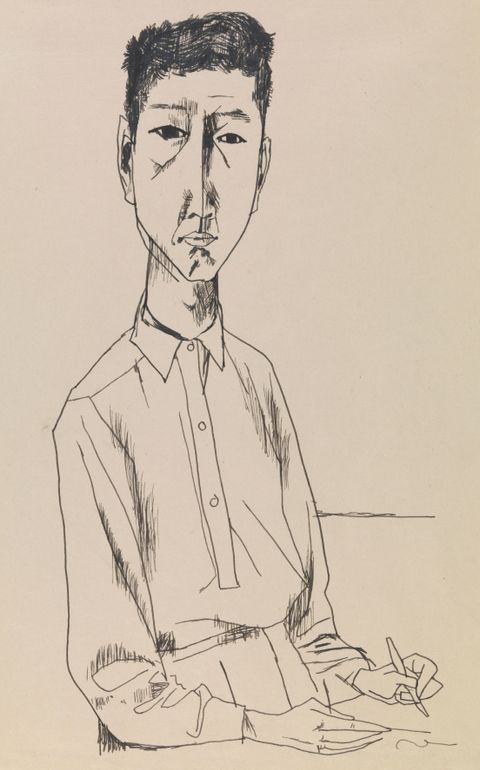

This section showcases a selection of records from the Slade archive: panoramic class photos providing compelling but incomplete representations of a given year group; student files containing a variety of records reflecting operations bureaucratic and beyond, such as correspondence between officials, funders, tutors’ reports, reference letters, press clippings, and exhibition catalogues; and an autographed cricket bat, an idiosyncratic artefact self-consciously transformed into an art-historical document, which speaks to a complex moment of artistic sociality. Embracing archival studies, which posits archives as subjects of study in their own right, we invite consideration of the form, content, and context of such institutional records. When read along and against its grain, this art-school archive helps to illuminate the particular transcultural positions and conditions the artists and institutions featured were working in and through. Records in this section relate to artists such as Khalid Iqbal, Hussein Shariffe, Gazbia Sirry, Wendy Yeo, and Tseng Yu, and institutions as diverse as the State Corporation for Cinema in Khartoum, the National Film and Television School in Beaconsfield, the UK Home Office, the British Council, and the National College of Arts, Lahore. Through this arrangement, we foreground the intertextual nature of evidence and the complexities of the source material that underpin our propositions in the accompanying long-form essay.

II. Imagining Postcolonial States

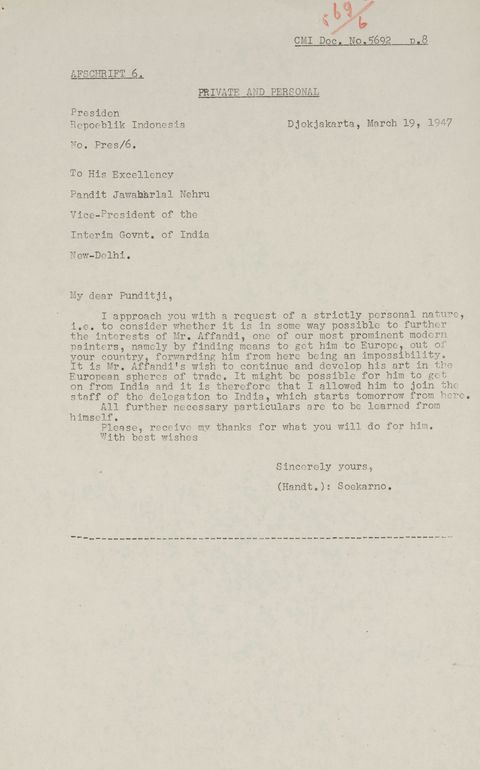

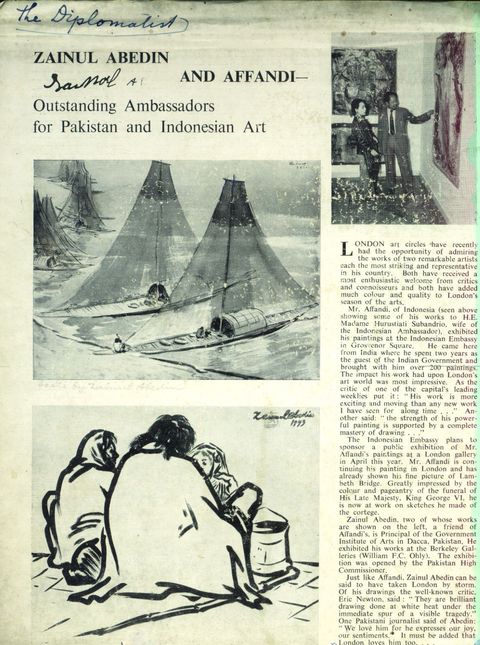

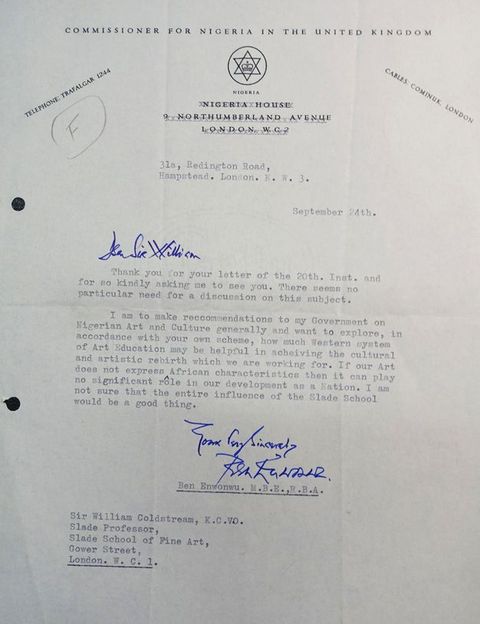

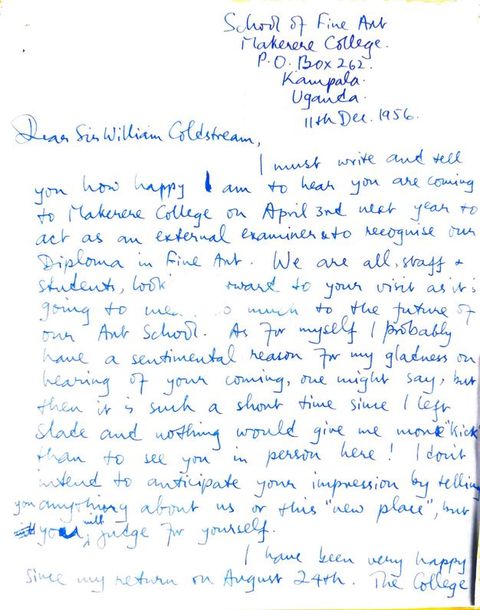

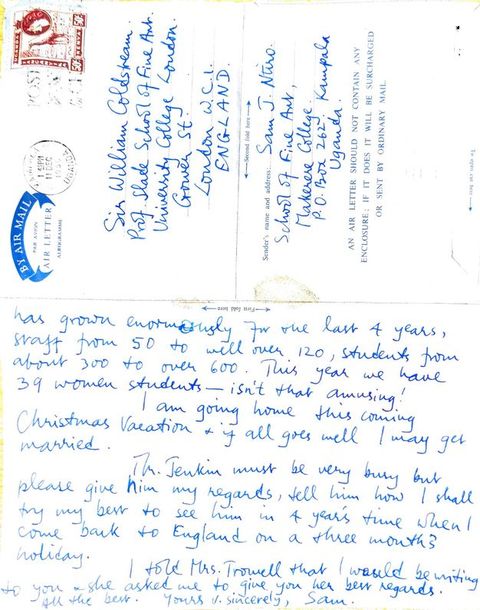

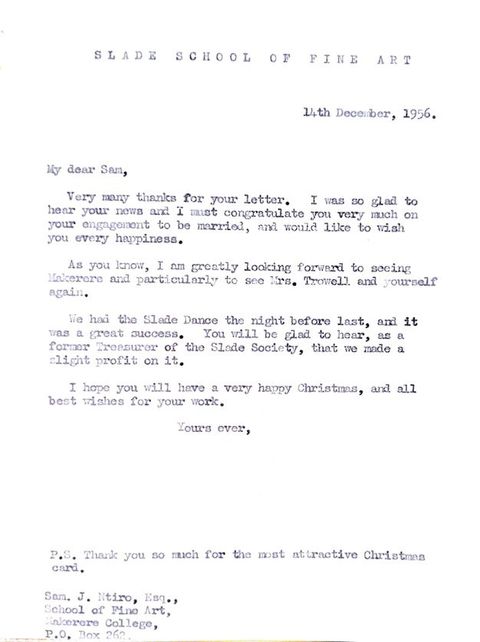

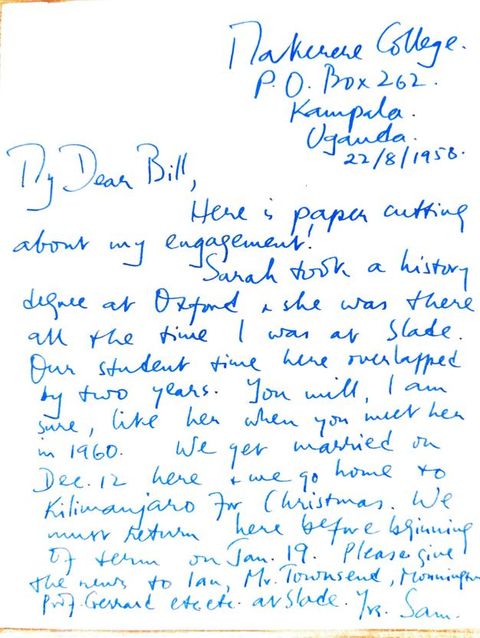

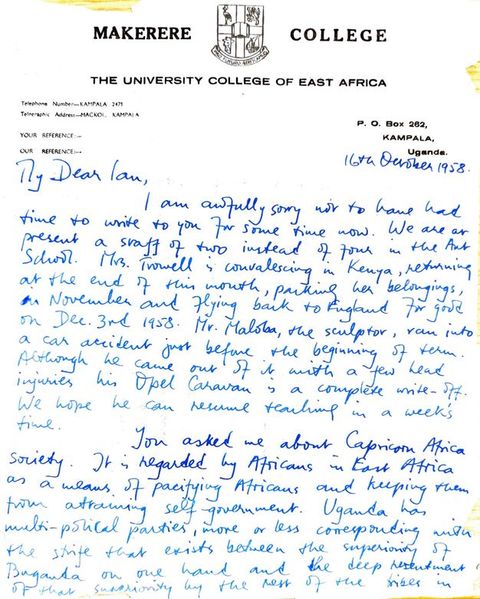

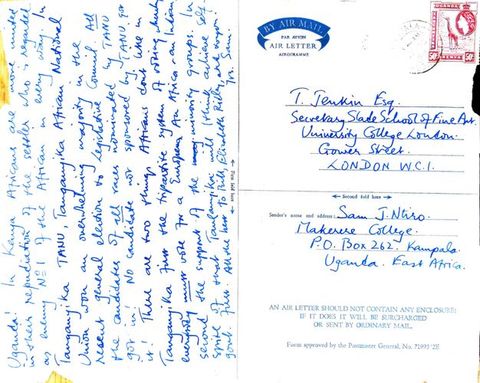

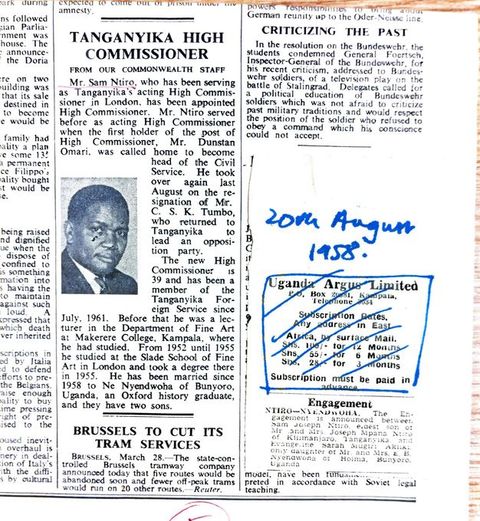

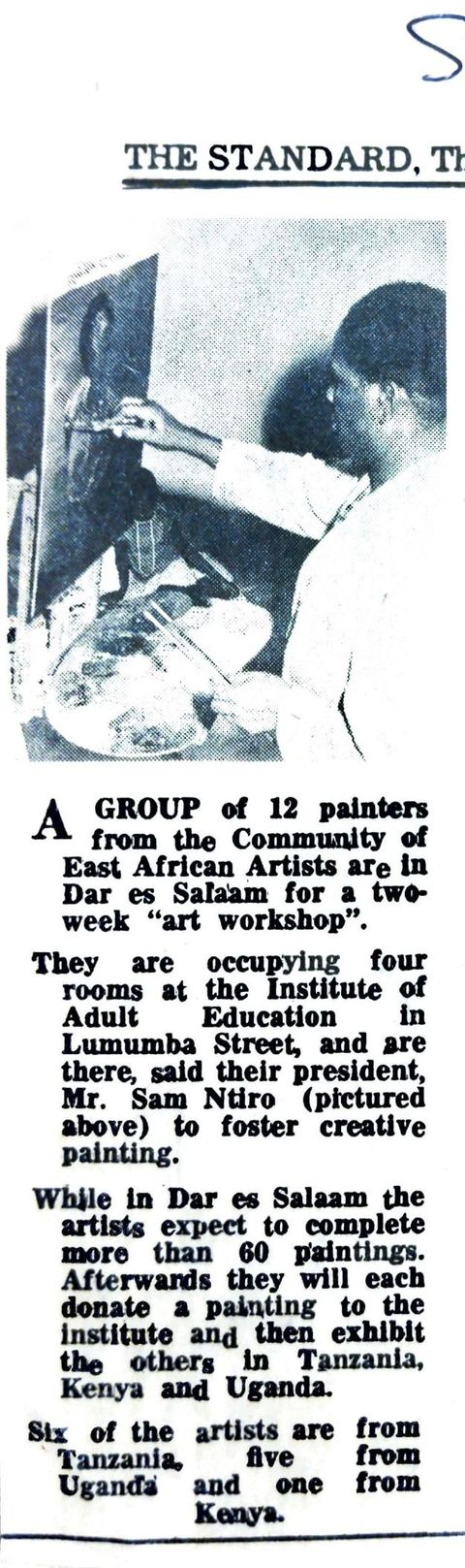

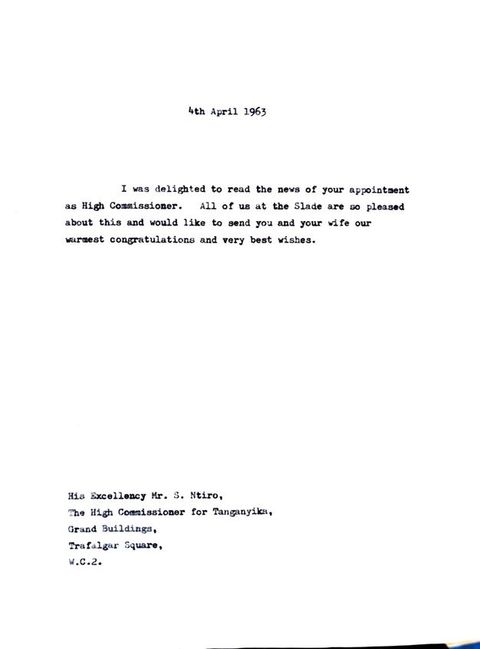

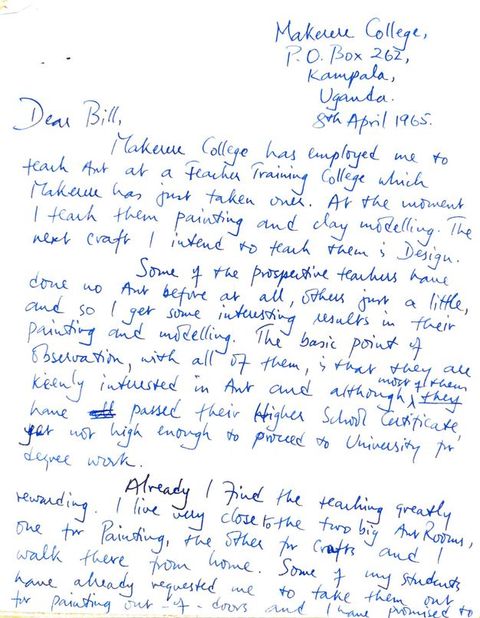

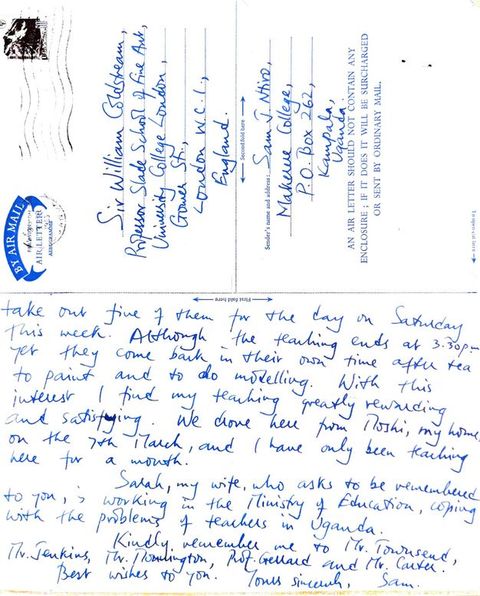

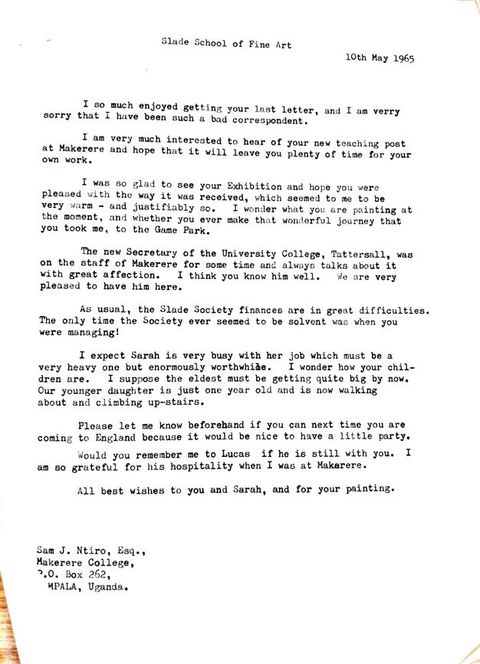

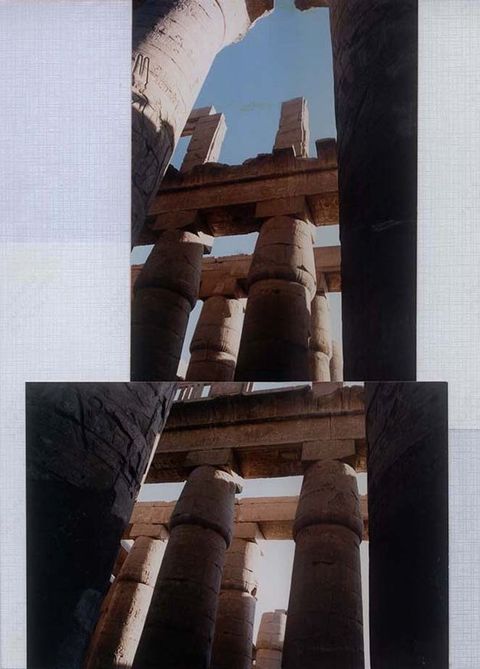

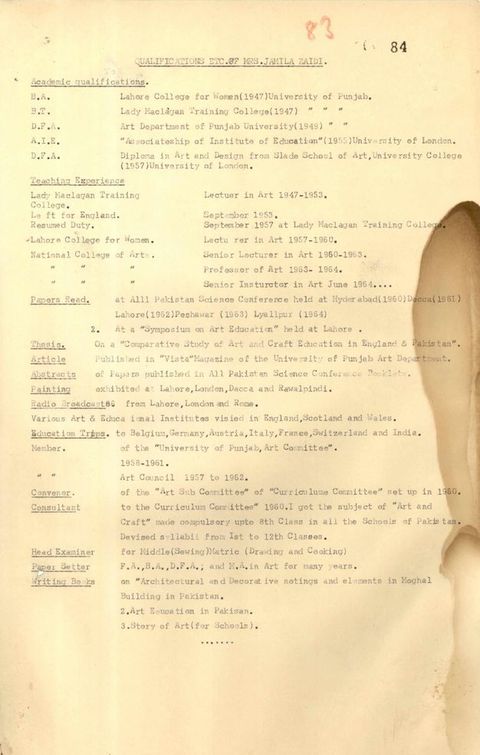

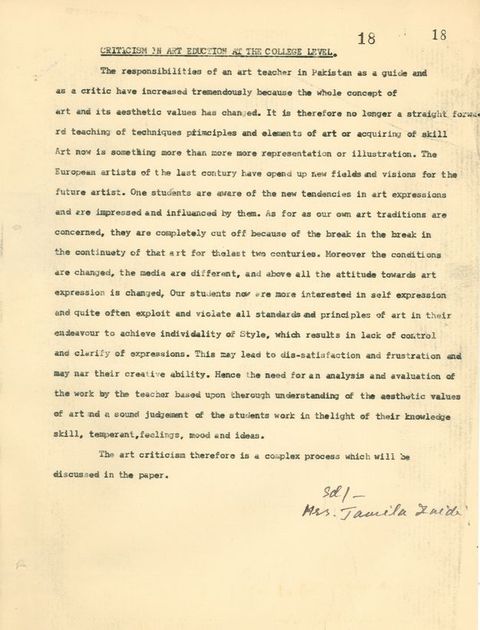

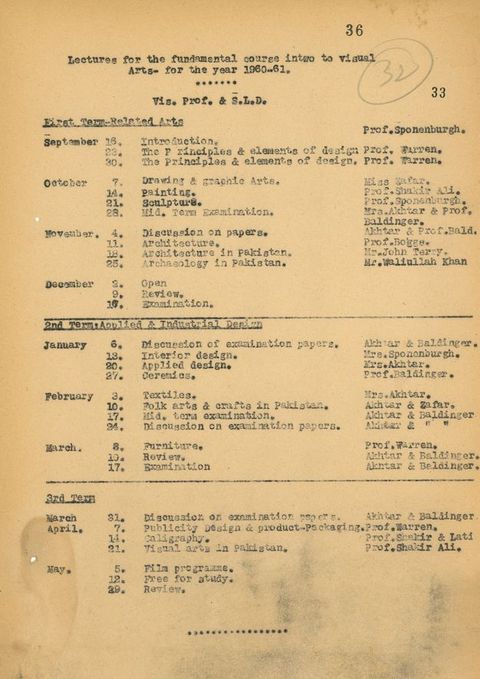

The documents featured in this section begin to elucidate the complex contrapuntal positionalities and objectives of artists who were simultaneously occupied in roles as bureaucrats, arts administrators, and key members of government, many of whom were funded by national governments to study at the Slade. Approaching the Slade as a contrapuntal site in a global context in which art education played an important role in postcolonial nation building and in the ongoing assertion of British influence, the records speak to case studies that can illuminate multivalent postcolonial modernisms. The records configured here touch on the stories of Zainul Abedin and the Government Institute of Fine Arts, Dhaka; Jamila Zaidi and the National College of Arts, Lahore; K.G. Subramanyan and art education in India; as well as relationships between the Slade and the Nigerian College of Arts, Science and Technology, and Makerere College, Kampala. Our movement through Bangladesh, Pakistan, India, Nigeria, and Uganda illustrates how diverse responses to colonial education can be set productively in dialogue with each other along transversals, as they are negotiated across multiple sites and through varying cultural and artistic imaginaries.

III. Contrapuntal World-Making

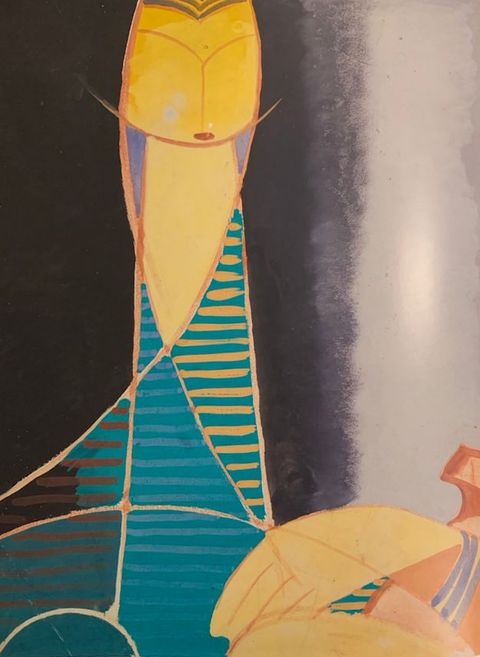

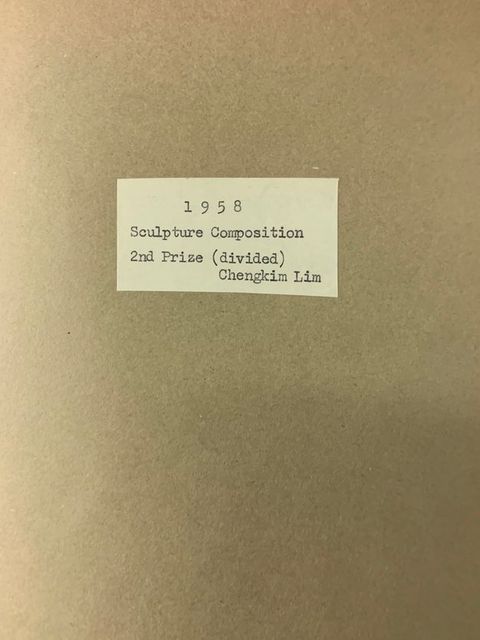

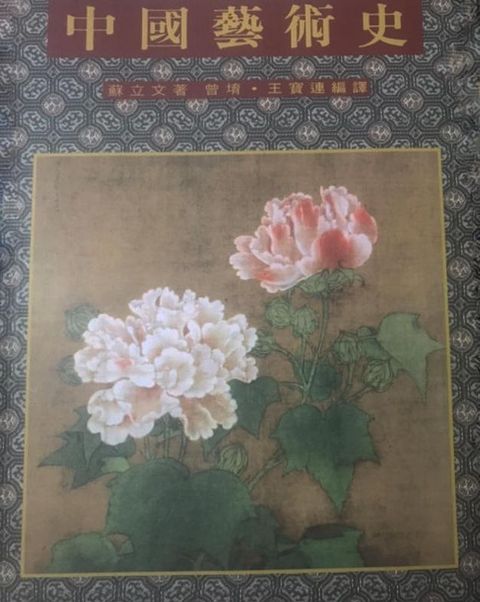

This section focuses on the work of art in the context of the contrapuntal worlds made and remade by overseas artists at the Slade, reflecting their negotiation of novel configurations of artistic methods, vocabularies, and schemas. The five artists featured—Zainul Abedin (1951–1952), Tseng Yu (1952–1956), Wendy Yeo (1953; 1955–1959), Anwar Jalal Shemza (1956–1960), and Kim Lim (1957–1960; 1969–1970)—each came to the Slade via different circuits of mobility and access, and each responded in turn to the opportunities and challenges of the Slade as a contact zone, producing distinct contrapuntal aesthetics. When examined together with the Slade as a transversal line, the relationships between these works become more evident, bringing out their harmonic interdependencies despite their independent melodic lines.

IV. Contrapuntal Pedagogies

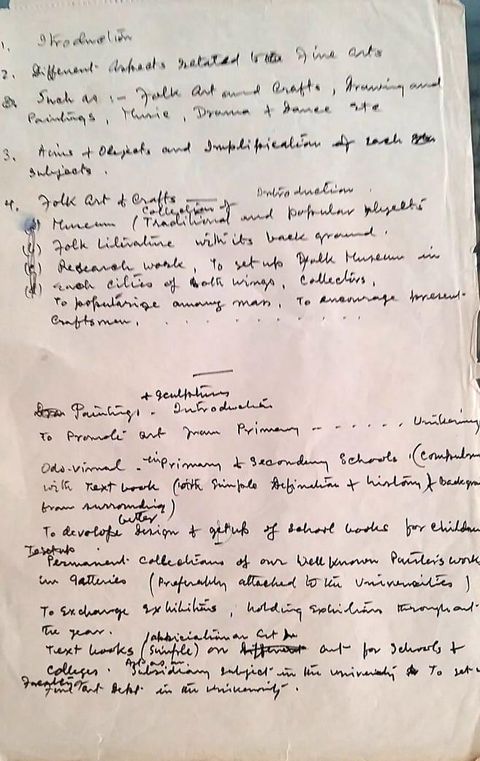

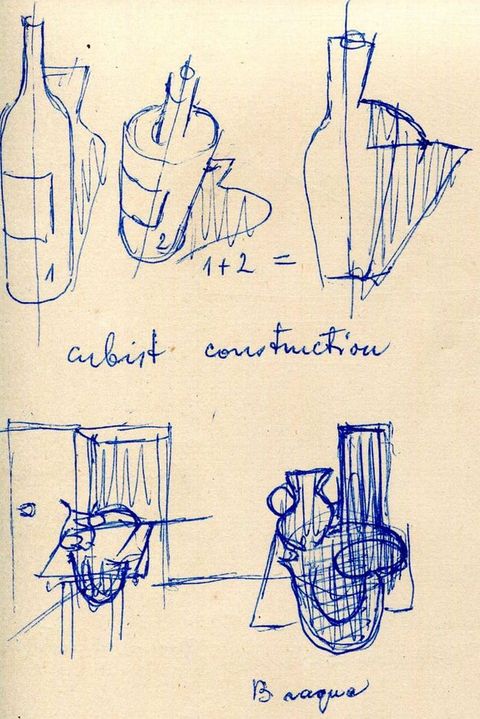

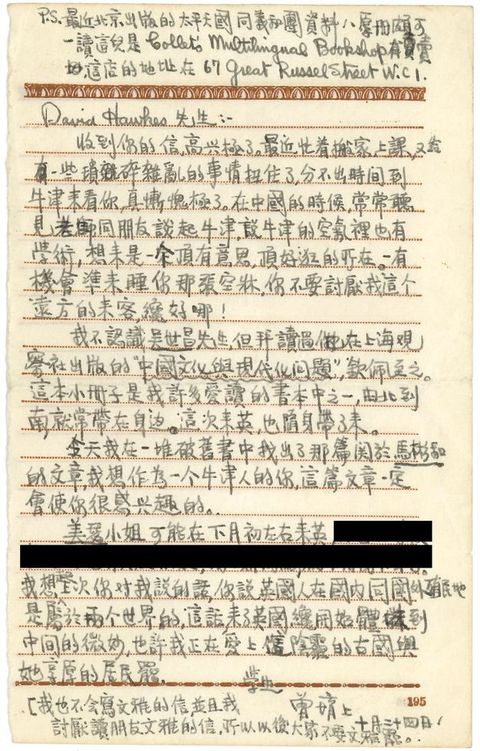

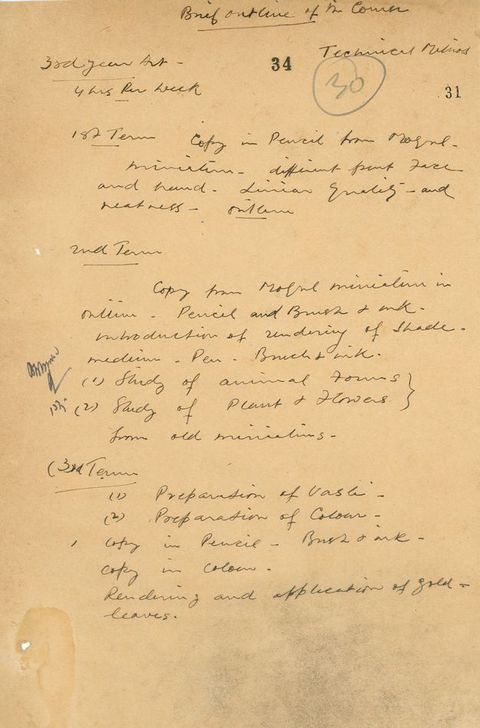

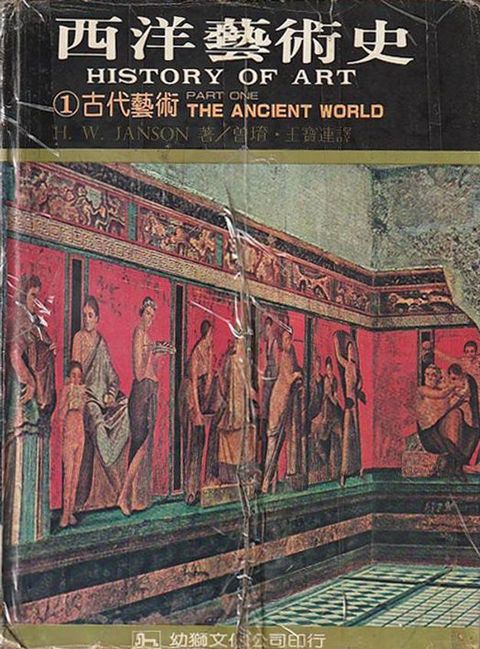

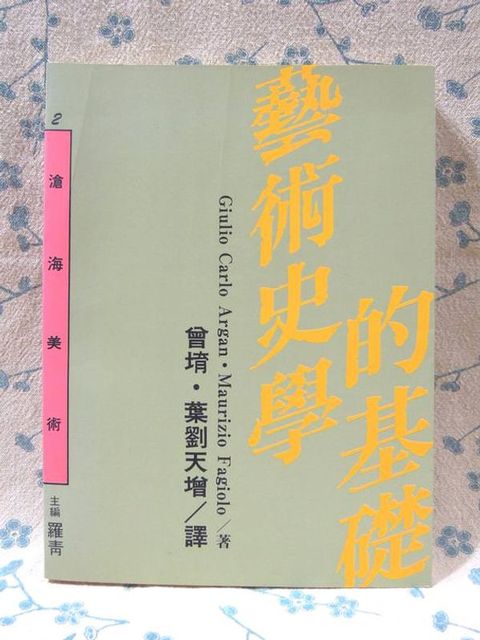

The records gathered here, including curricula, artists’ notes, and administrative and artistic correspondence, enable us to consider how a number of overseas artists who passed through the Slade reworked, supplemented, and often disrupted the school’s pedagogical models in contrapuntal fashions. Transversal comparisons of three groups of pedagogical artefacts from three different sites—Dhaka, Lahore, and the Sinophone world—provide a means of analysing critical appropriations of the Slade’s curriculum in order to draw relational comparisons between different colonial and postcolonial histories of art education.

V. Schema and Correction: Repositioning Art Histories

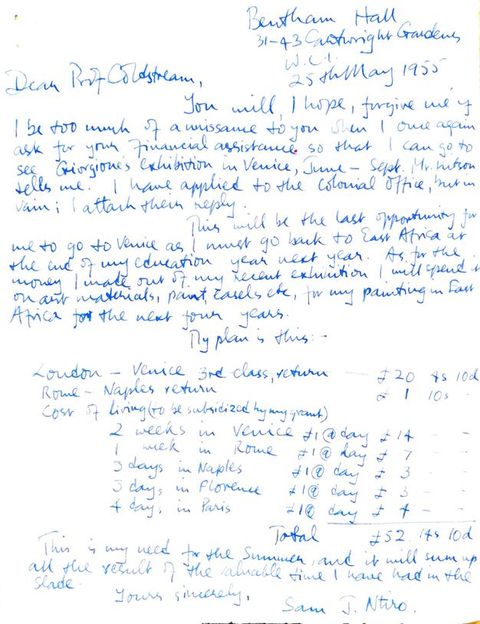

As the first art school situated within a university in Britain, the Slade was established with a mandate to provide fine arts training in the context of a liberal arts education, which distinguished it from other art schools until the more academic Diploma in Art and Design (DipAD) was introduced to studio courses nationwide in 1960. In this section, we juxtapose archival records with artists’ accounts of art history at the Slade and its situation within the broader intellectual ecosystem of the University of London. This distinguishes the provision of art history within the art school fostered as at once a fertile ground for cross-disciplinary artistic experimentation, and a context deeply rooted in Eurocentric and colonial epistemologies, inheritances, and positionings. For artists coming from the colonized or decolonizing worlds, this art-historical education, designed to enable contemporary artists to situate their work within the arc of history, made evident the Eurocentrism of the art world and catalysed a variety of critical responses.

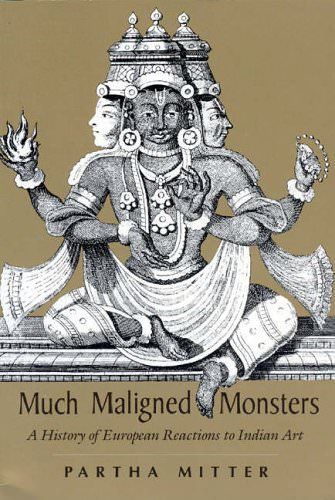

The interventions made by artists such as Ben Enwonwu, Anwar Jalal Shemza, K.G. Subramanyan, and Tseng Yu as well as by art historian Partha Mitter can also be understood in dialogue with those scholars of art history who taught at the Slade in the 1950s, namely, Rudolph Wittkower (1949–1956) and Ernst Gombrich (1956–1961). These “corrections” to the “schema”, to use Gombrich’s formulation, point to a mutually informing, albeit at times fraught, terrain of contact between art historians and artists that continues to have resonances in our understanding of global art histories.6

6Ernst Gombrich, Art and Illusion (New York: Pantheon Books, 1960).

About the authors

-

Liz Bruchet is a researcher, archive curator, and oral historian, and Senior Lecturer in Archival Studies in the Department of Information Studies, UCL. Her research focuses on the records and recordkeeping practices of visual arts organisations, with particular interests in the interconnections between archives and curation, as well as the biographies of archives, “orphan” objects and records, and the value of these for curation. Her MA in Curatorial Studies (UBC) drew on her experience in museum and gallery work in Canada, and her PhD in Archival Studies from the University of Brighton developed a conceptual framework for understanding the tangled relationships between archival and curatorial practices. She has led oral history projects for institutions such as the Association for Art History and the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, and prior to her current role, was Researcher and Archive Curator at the Slade School of Fine Art, UCL, for which she has developed a range of collaborative research, digitisation, and exhibition projects. Recent publications include “Archival Finding Aids and Perceptual Frames: Tracing Material Contact Points Through Stephen Chaplin’s Slade Archive Reader”, in The Materiality of the Archive: Creative Practice in Context, ed. Sue Breakell and Wendy Russell (Routledge, forthcoming 2022).

Liz Bruchet is a researcher, archive curator, and oral historian, and Senior Lecturer in Archival Studies in the Department of Information Studies, UCL. Her research focuses on the records and recordkeeping practices of visual arts organisations, with particular interests in the interconnections between archives and curation, as well as the biographies of archives, “orphan” objects and records, and the value of these for curation. Her MA in Curatorial Studies (UBC) drew on her experience in museum and gallery work in Canada, and her PhD in Archival Studies from the University of Brighton developed a conceptual framework for understanding the tangled relationships between archival and curatorial practices. She has led oral history projects for institutions such as the Association for Art History and the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, and prior to her current role, was Researcher and Archive Curator at the Slade School of Fine Art, UCL, for which she has developed a range of collaborative research, digitisation, and exhibition projects. Recent publications include “Archival Finding Aids and Perceptual Frames: Tracing Material Contact Points Through Stephen Chaplin’s Slade Archive Reader”, in The Materiality of the Archive: Creative Practice in Context, ed. Sue Breakell and Wendy Russell (Routledge, forthcoming 2022). -

Ming Tiampo is Professor of Art History, and co-director of the Centre for Transnational Cultural Analysis at Carleton University. She is interested in transnational and transcultural models and histories that provide new structures for understanding and reconfiguring the global. She has published on Japanese modernism, global modernisms and diaspora. Tiampo’s book Gutai: Decentering Modernism (University of Chicago Press, 2011) received an honourable mention for the Robert Motherwell Book award. In 2013, she was co-curator with Alexandra Munroe of the AICA award-winning Gutai: Splendid Playground at the Guggenheim Museum in New York. Her current book projects include Transversal Modernisms: The Slade School of Fine Art, a monograph which reimagines transcultural intersections through global microhistory, and Intersecting Modernisms, a collaborative sourcebook on global modernisms. Her latest book, Jin-me Yoon, is forthcoming with Art Canada Institute in 2022. Tiampo is an associate member at ici Berlin, a member of the Hyundai Tate Research Centre: Transnational Advisory Board, a member of Asia Forum, a founding member of TrACE, the Transnational and Transcultural Arts and Culture Exchange network, and co-lead on its Worlding Public Cultures project.

Ming Tiampo is Professor of Art History, and co-director of the Centre for Transnational Cultural Analysis at Carleton University. She is interested in transnational and transcultural models and histories that provide new structures for understanding and reconfiguring the global. She has published on Japanese modernism, global modernisms and diaspora. Tiampo’s book Gutai: Decentering Modernism (University of Chicago Press, 2011) received an honourable mention for the Robert Motherwell Book award. In 2013, she was co-curator with Alexandra Munroe of the AICA award-winning Gutai: Splendid Playground at the Guggenheim Museum in New York. Her current book projects include Transversal Modernisms: The Slade School of Fine Art, a monograph which reimagines transcultural intersections through global microhistory, and Intersecting Modernisms, a collaborative sourcebook on global modernisms. Her latest book, Jin-me Yoon, is forthcoming with Art Canada Institute in 2022. Tiampo is an associate member at ici Berlin, a member of the Hyundai Tate Research Centre: Transnational Advisory Board, a member of Asia Forum, a founding member of TrACE, the Transnational and Transcultural Arts and Culture Exchange network, and co-lead on its Worlding Public Cultures project.

Footnotes

-

1

The concept of transversals was first used by Tiampo to theorize the relationships between histories that are both parallel and linked through a third term. Ming Tiampo, “Slade, London, Asia: Intersections of Decolonial Modernism”, 10 November 2020, https://www.paul-mellon-centre.ac.uk/whats-on/slade-london-asia. ↩︎

-

2

Edward Said, Culture and Imperialism (New York: Vintage, 1993), 51. ↩︎

-

3

Shu-mei Shih, “Comparison as Relation”, in Comparison: Theories, Approaches, Uses, ed. Rita Felski and Susan Stanford Friedman (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013), 79–98. ↩︎

-

4

Carolyn Hamilton, Verne Harris, and Graeme Reid, Introduction to Refiguring the Archive, ed. Carolyn Hamilton et al. (Dordrecht: Springer, 2002), DOI:10.1007/978-94-010-0570-8_1. ↩︎

-

5

Anne J. Gilliland, Sue McKemmish, and Andrew J. Lau, eds., Research in the Archival Multiverse (Clayton, VIC: Monash University Publishing, 2016), http://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/31429. ↩︎

-

6

Ernst Gombrich, Art and Illusion (New York: Pantheon Books, 1960). ↩︎

Imprint

| Author | Ming Tiampo Liz Bruchet |

|---|---|

| Date | 18 July 2021 |

| Category | Animating the Archive |

| Review status | Peer Reviewed (Double Blind) |

| License | Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) |

| Downloads | PDF format |

| Article DOI | https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-20/animatingsladearchive |

| Cite as | Tiampo, Ming, and Liz Bruchet. “Slade, London, Asia: Animating the Archive (Part 1).” In British Art Studies. London and New Haven: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art and Yale Center for British Art, 2021. https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-20/animatingsladearchive. |