Black Apollo

Black Apollo: Aesthetics, Dissection, and Race in Joseph Maclise’s Surgical Anatomy

By Keren Rosa Hammerschlag

Abstract

This article is part of the Objects in Motion series in British Art Studies, which is funded by the Terra Foundation for American Art. Projects in the series examine cross-cultural dialogues between Britain and the United States, and may focus on any aspect of visual and material culture produced before 1980. The aim of Objects in Motion is to explore the physical and material circumstances by which art is transmitted, displaced, and recontextualised, as well as the transatlantic processes that create new markets, audiences, and meanings. Joseph Maclise’s Surgical Anatomy (1851) is no ordinary anatomical atlas. While there is an assumption that the cadavers pictured in Western anatomical illustrations are white, Maclise included in his publication several depictions of the dissection of a Black man. A close examination of Maclise’s rendering of the interior and exterior of the Black body allows for a consideration of the complex relationship between aesthetics and race in mid-nineteenth-century anatomical illustration. It also offers an opportunity to reflect on the nature of dissection during the mid-Victorian period and the racial identities of those who ended up, against their will, on the dissecting table. Shifting from the anatomy theatre to the art gallery, the Black cadaver in Maclise’s atlas is notably aestheticised, placing him in dialogue with classical statues such as the Apollo Belvedere, the “high” art productions of Joseph’s brother Daniel Maclise, pictures of Black pugilists, and abolitionist imagery from the period.

Introduction

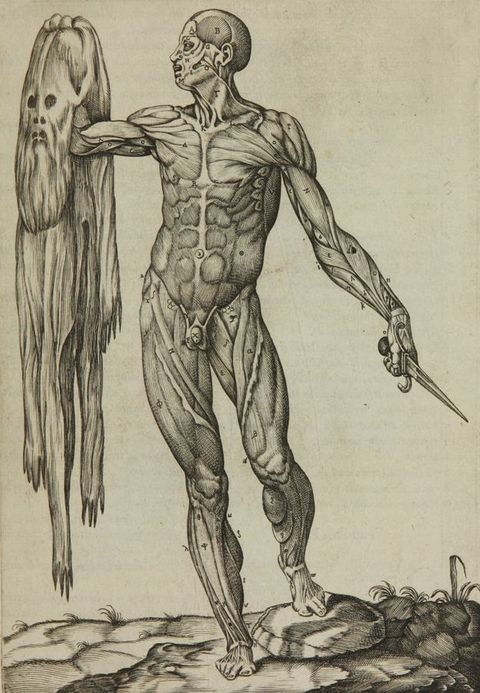

Western anatomical atlases are rarely viewed through the lens of race. One reason for this is that most of the bodies that furnish anatomical atlases dating back to Andreas Vesalius’ De humani corporis fabrica (1543) are white—or so they seem.1 The figures in anatomical atlases often appear without their skin, their bodies having been literally and representationally flayed, in order to display the underlying anatomical structures. But their status as white Europeans has remained unquestioned in the scholarship on the history of anatomical illustration.2 This assumption is reinforced by the frequency with which anatomised subjects from the Renaissance onwards have been positioned to resemble Greco-Roman statues. A prime example of this is an illustration of a flayed cadaver holding his skin in one hand and a dissecting knife in the other from Juan Valverde de Amusco’s Anatomia del corpo humano (1560) (fig. 1).3 This is a remarkable image for numerous reasons, including the fact that the man’s skin, which he has apparently removed himself, resembles a second ghostly visage.4 It is also significant that the anatomised figure strikes a pose which resembles that of the Apollo Belvedere (ca. 120–140), with one arm raised, the other lowered, a wide contrapposto, and head turned towards the raised arm (fig. 2). I will be returning to the Apollo Belvedere and Valverde’s macabre anatomised version of it in due course.

1

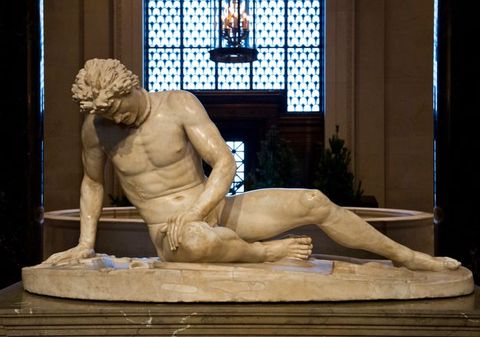

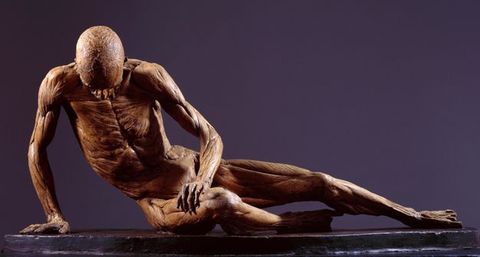

Artistic anatomy teaches artists to see through skin to the underlying anatomical structures, principally the bones and muscles, which dictate the appearance of the body in action and repose.5 Around 1771, William Hunter, professor of anatomy at the Royal Academy of Arts (or the artist enlisted to help him, Agostino Carlini), directed that the flayed body of an executed criminal be manoeuvred into the pose of the famous Dying Gaul (Roman, first or second century ad) (fig. 3) before being cast in plaster (ca. 1834) (fig. 4).6 This écorché then took its place among the other teaching aids in the Royal Academy Schools.7 By having Smugglerius, as it continues to be known, repeat the pose of the Dying Gaul, artists and art students could see through the marble surface of the classical statue and imagine the musculature beneath. The lesson was that, if the artist wanted to create an image of the human form as perfect as that seen in the Dying Gaul, he must have a grasp of the anatomical structures that produced its outward appearance.8

5

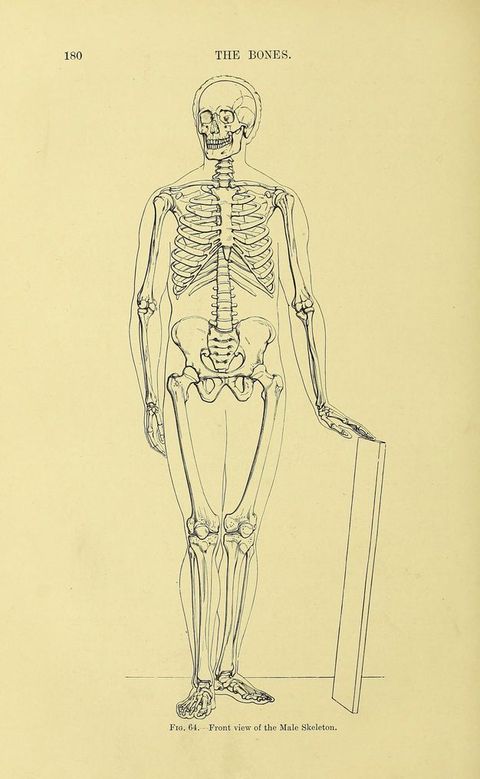

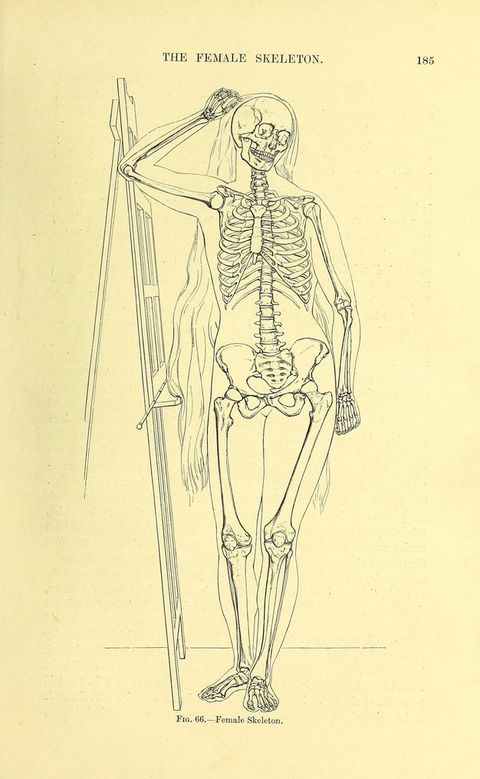

In 1878, John Marshall, professor of anatomy at the Royal Academy from 1873 to 1891, laid out the anatomy—the bones, joints, and muscles—that he believed artists should know in order to depict the human body accurately.9 His manual, Anatomy for Artists, includes several illustrations that epitomise the kind of penetrative looking that the study of anatomy was intended to encourage. For example, in “Figure 64.—Front view of the Male Skeleton”, an animated skeleton is seen resting its hand on what appears to be a canvas (fig. 5). The outline of the body is included, but the artist is encouraged to see through the surface of the body to the skeleton beneath. A few pages later, in “Figure 66.—The Female Skeleton”, another skeleton—this time, a female one—rests her elbow on an easel (fig. 6). The outline of the body is again included, with hair attached.10 The canvas in “Front view of the Male Skeleton” and the easel in “The Female Skeleton” place us in an artist’s studio, with the skeleton in the first illustration playing the role of the artist, and the skeleton in the second assuming the role of the life model.

9

In this article, rather than attempting to see through the surface of the body as Marshall and others advocated, I want to imagine a process by which the anatomised bodies used to teach anatomy to aspiring doctors, surgeons, and artists might be re-skinned, and the racial identities of those who ended up on the dissecting table restored. In Human Remains: Dissection and Its Histories, Helen MacDonald quotes John Gurche, the paleo artist (a paleo artist uses scientific evidence to recreate in visual form prehistoric scenes and creatures): “The process of reconstruction is like a dissection in reverse”.11 MacDonald describes being “caught in the historian’s impossible dilemma … No historian can really make people live again. We are not resurrectionists.”12 Nonetheless, she believes “that historians can be sufficiently thorough to reconstruct something of how people in the past experienced their lives”—and their deaths.13 If we look closely enough at the anatomical illustrations and associated text produced by or under the instruction of such eminent surgeons as William Hunter, Friedrich Tiedemann, John Marshall, and Joseph Maclise, it is possible to find traces of the identities of “the dissected”.14 From there we can begin the slow process of building up a fuller picture of the race (and gender, religion, etc.) of those who ended up, against their will, on dissecting tables in a period before consent was required to cut open a person’s corpse. Hence, with an awareness of the limitations of such an endeavour—I am no resurrectionist (!)—I will be attempting “a dissection in reverse” through close analysis of a range of images, principally Plates 5 and 14 of Joseph Maclise’s Surgical Anatomy (1851) (figs. 7 and 8).

11

Identifying Corpses

In the illustrations produced by Joseph Maclise for Surgical Anatomy, exemplary male physical specimens abound.15 Maclise (1815–1880) was an Irish surgeon who studied at University College, London, and the École Pratique, L’Hôpital de la Pitié, in Paris, before settling into practice on Fitzroy Square in London.16 He was also brother to the successful Royal Academy artist Daniel Maclise (1806–1870), known for his decorative schemes for the House of Lords. Joseph Maclise not only penned medical and scientific texts, but also produced the illustrations, no doubt with reference to the art and expertise of his brother. After illustrating Richard Quain’s The Anatomy of the Arteries of the Human Body (1844), Maclise wrote and illustrated Comparative Osteology (1847), Surgical Anatomy (1851), and On Dislocations and Fractures (1859).17 In the preface to The Anatomy of the Arteries of the Human Body, Quain, then professor of anatomy at University College, wrote of Maclise: “To carry out my views as to the delineations, I obtained the assistance of my friend and former pupil, Mr. Joseph Maclise.” Also in his preface, Quain professed that he had inspected 930 bodies “with reference to the subject of my inquires”.18

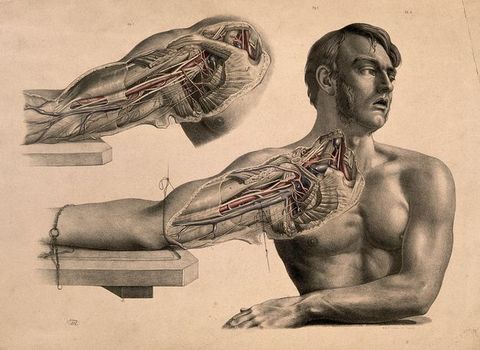

15In Surgical Anatomy, hooks, scalpels, and other surgical instruments reference the dissections undertaken by Maclise in London and Paris, and guide the aspiring surgeon as he or she dissects (fig. 9). A connection might here be made between the surgical instruments depicted by Maclise and the engraver’s tools that would have been used in the production of the images. In the preface to Surgical Anatomy, Maclise specified the intended audience for the publication: “the student of medicine and the practitioner removed from the schools”.19 As photographs of nineteenth-century anatomy theatres reveal, the folio-sized illustrations (54.5 x 37.7 cm) hung on the walls of dissecting rooms and anatomy theatres (see figs. 9–18 in this feature's introduction). But the size of the atlas, along with its elaborate illustrations, made it suitable for libraries and the collections of educated gentlemen with an aesthetic sensibility and interest in male anatomy.20 The figures, as rendered by Maclise, are overwhelmingly healthy adult men with developed musculature, lustrous hair, blemish-free skin, and expressions that look remarkably peaceful considering the bodily violations taking place. Occasionally, fabric-turned-drapery crops and frames the body pictured (fig. 10).21 This enhances the aesthetic quality of the atlas and those depicted in it, elevates the images to the status of “high” art, and speaks to the skill of the artist-anatomist.

19

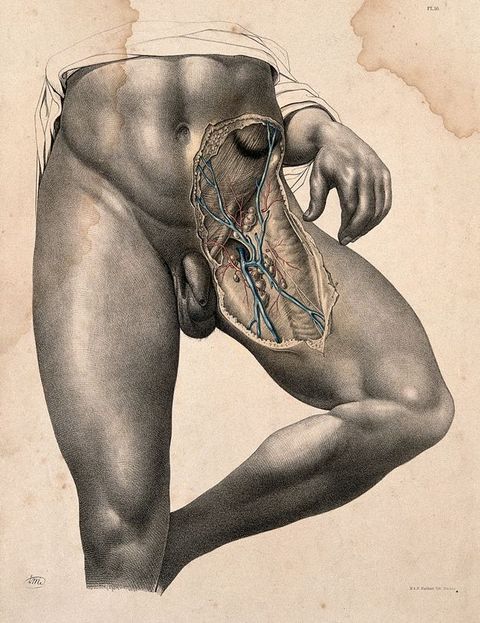

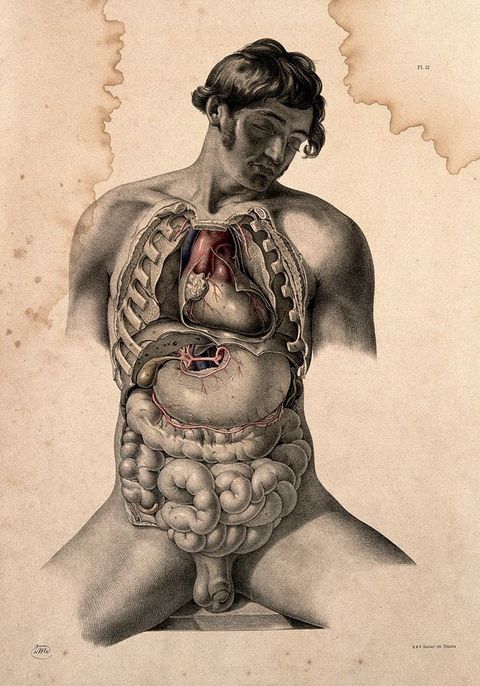

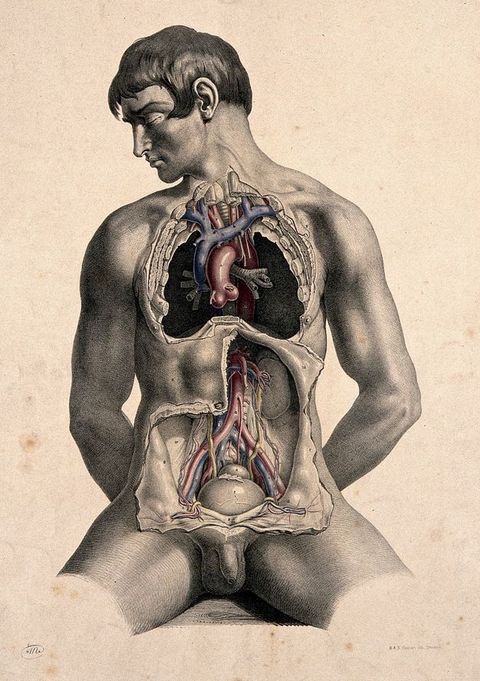

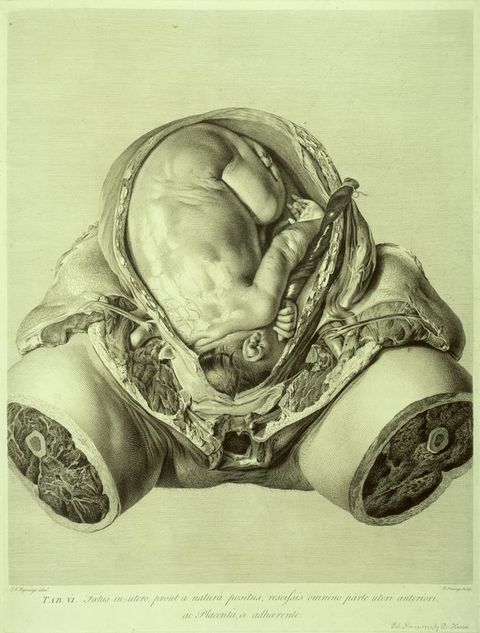

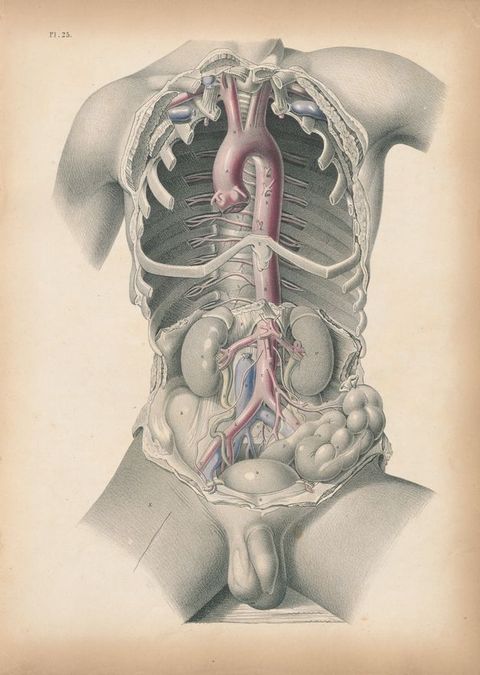

In Plate 12 (fig. 11), an illustration of the deeper organs of the thorax and abdomen, the body is gently cropped at the top of the arms and thighs, much like the Belvedere Torso (first century BCE) (fig. 12). The figure is in possession of distinguishing mutton-chop sideburns and a carefully placed curl, which hangs from his downcast head, the overall appearance being of a man who has peacefully nodded off to sleep. In Plate 15, an illustration of the relation of the internal parts to the external surface of the body, we see the cadaver’s arms, but not his hands, which are likely tied behind his back (fig. 13).22 The position of his arms helps emphasise his musculature, signalling that this was clearly someone who laboured. But there are no signs of physical degradation, injury, poverty, or hardship. His head is turned towards the left and angled downward, which serves to highlight his pronounced jawline, a bulging vein in his neck, and a lick of hair that comes down between his ear and the corner of his eye. His penis and scrotum are positioned prominently between his muscular thighs—thighs that gently fade out towards the bottom of the page. While the body is truncated at the top of the legs, we do not see evidence of the violent dismemberment of the limbs, which is so striking a feature of Table VI of William Hunter’s The Anatomy of the Human Gravid Uterus (1774) (fig. 14).23

22

We can assume that, at University College and the École Pratique, Maclise would have had access to the best cadavers on the market. Nonetheless, the idealised cadavers depicted in Surgical Anatomy are a far cry from the actual sick, poverty-stricken, and elderly bodies that Maclise and his colleagues would have encountered in mid-nineteenth-century dissecting theatres. On 1 August 1832, in Britain, the Anatomy Act was passed, which made unclaimed human bodies legally available to medical schools for “Anatomical Examination”. Prior to that, dissection was a form of corporal punishment, depicted in all of its gory brutality by William Hogarth in The Reward of Cruelty, the final stage in his The Four Stages of Cruelty series (1751) (fig. 15). In The Reward of Cruelty, Tom Nero still has a noose around his neck, having been delivered fresh from the gallows. The Anatomy Act mandated the appointment of inspectors of schools of anatomy, who were required to:

24Make a Quarterly Return to the said Secretary of State or Chief Secretary … of every deceased Person’s Body that during the preceding Quarter has been removed for Anatomical Examination to every separate Place in his District where Anatomy is carried on, distinguishing the Sex, and as far as is known at the Time, the Name and Age of each Person whose Body was so removed as aforesaid.24

With such limited official information available, historians, art historians, and medical historians are required to examine a range of visual and textual materials related to death and dissection in order to build up a more substantial picture of the identities of those who ended up on dissecting tables during the nineteenth century. In Dissection: Photographs of a Rite of Passage in American Medicine 1880–1930, medical historian John Harley Warner performs this important work by examining photographs of American medical students grouped around cadavers. In the United States, with an insufficient supply of cadavers for dissection, grave robbing was widespread, and it was disproportionately African American graves and cemeteries that were pillaged. Warner explains that this was because African Americans, along with other disenfranchised groups, were less able to defend against the violation of grave robbing. In the Australian context, a rare piece of evidence relating to the race of cadavers used for dissection appears in the May 1898 edition of Speculum, the University of Melbourne Medical School journal. The following apparently comical incident is relayed: “In the Dissecting Room.—Very junior man gazing on a blackfellow: ‘See! this body is putrifying: it is all black.’”26 The racist joke lies in the equation of dark skin with decaying flesh.

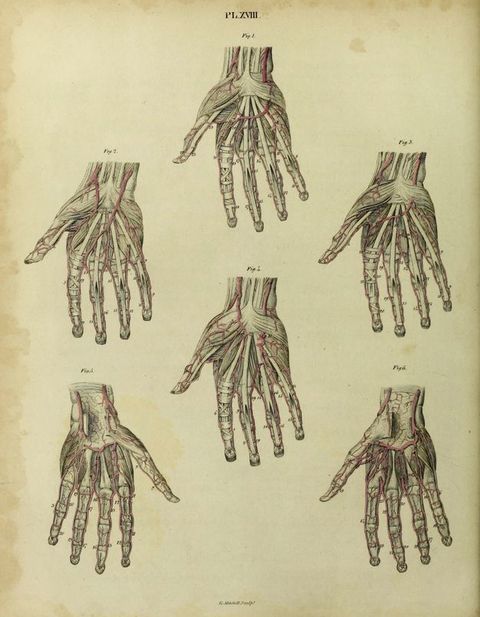

26Just as there is an assumption that the bodies depicted in anatomical atlases are white, so too is there an assumption that they are male. When female anatomy is displayed, it is generally the reproductive organs that are the focus of scientific and artistic interest.27 Friedrich Tiedemann’s Tabulae arteriarum corporis humani (1822), translated into English in 1829 as Plates of the Arteries of the Human Body, suggests otherwise.28 Tiedemann explains in his introduction: “I have with my own hands dissected upwards of five hundred bodies, and examined with no small degree of diligence subjects of both sexes, and of all ages.”29 Later he states:

2730In the explanations, I have always indicated the age and sex of the individual from whom the plate is taken, as the diameter of the arteries differ much according to age and sex; but their relations, curvatures, and direction are so constant, that it is of no moment whether the body has been male or female, young or old.30

It would be hard to tell just from looking at the illustrations in Tiedemann’s atlas that the figures are a mixture of men and women; they are neither explicitly gendered nor racialised (i.e. they mostly do not have skin, hair, or other individualising features). They do not differ in size. But the explanatory text reveals that several of the body parts belonged to women. This includes Plate XIV, Figure 2, which “Shows the left arm of a woman”; Plate XV, Figure 3, which “Exhibits the right arm of a woman, in which the interosseal artery arose from the humeral”; Plate XVI, Figure 2, which “Exhibits the left arm of a woman, in which an unusual superficial interosseal artery is served”; and Plate XVIII, Figure 3, which displays “The right hand of a woman, in which an unusual distribution of the arteries is seen” (fig. 16).

Finally, there is another clue to the identity of dissected corpses in anatomical atlases: foreskins, or the lack thereof. The majority of male cadavers in Maclise’s Surgical Anatomy have foreskins; however, in Plate 12, the man is circumcised or has a withdrawn foreskin.31 It is hard to judge conclusively based on this image the intactness of the prepuce, but the genitalia are presenting in an anomalous mode and are therefore worthy of commentary.32 Despite debates over the potential health benefits of circumcision, the operation was not routinely performed in nineteenth-century Britain. In the words of Sander L. Gilman: “Modernity, at least in the Western diaspora, came to regard infant male circumcision as the key marker of a Jewish religious identity.”33 In other words, a circumcised penis was a sign of Jewish “Otherness”. There were circumcisions performed on non-Jewish men for medical reasons. In these cases, the objective was to remove the restriction on urine, not to remove the entire prepuce. In the case of Plate 12, not enough of the foreskin has been removed to constitute a “kosher” circumcision according to Orthodox Jewish Law, but it nonetheless appears that the procedure has taken place. It could be a botched Jewish circumcision, which did and still does occur.

31In Plate 12, the circumcised penis is inconsequential to the anatomical lesson being taught, but it invites speculation about the religious background of the figure. Could this be a Jewish cadaver? Significantly, one of the écorché models in the collection of the Royal Academy is widely recognised to have been made from the body of Solomon Porter, an executed Jewish criminal (fig. 17).34 Porter was part of a gang of Jewish burglars, led by a Jewish surgeon and apothecary, Dr Weil, who broke into the house of Mrs Hutchinson in Chelsea on 11 June 1771. In the course of the robbery, a servant was murdered. Solomon, along with Dr Weil, Asher Weil, and Jacob Lazarus, was found guilty and executed at Tyburn on 9 December 1771.35 It is likely that it was Porter’s body that was, under the direction of William Hunter, flayed, manoeuvred into a pose reminiscent of a classical statue, and then cast in the production of an écorché for the Royal Academy.36 But the use of Porter’s corpse did not end at the Royal Academy. Hunter removed and preserved Porter’s penis for his anatomical collection, now at the Hunterian Museum, University of Glasgow.37 The record in the Catalogue of Anatomical Preparations in the Hunterian Museum (1840) reads: “No. 45. s. The upper half of the Penis of a Jew; as the prepuce is removed, it explains circumcision: there are also two large chancres on the glans. (Solomon Porter.)”38 Porter’s penis was clearly of interest to Hunter because it was Jewish/circumcised and diseased.

34

Whether Jewish men were more or less susceptible to syphilis by virtue of being circumcised was the subject of medical inquiry during the nineteenth century.39 Jonathan Hutchinson, surgeon to the Metropolitan Free Hospital and an expert on syphilis, concluded that “[t]he circumcised Jew is … very much less liable to contract syphilis than an uncircumcised person”.40 In the same year that Hutchinson published his findings, the second volume of Maclise’s Surgical Anatomy was being advertised. Mr E. Harding Freeland, surgeon to the St George’s and St James’s Dispensary, London, writing for The Lancet (basing his findings on the data collected by Hutchinson fifty years earlier), found

39Solomon Porter’s preserved genitals bring to the fore the intersecting histories of deviant sexuality and religious Otherness, especially in the case of Jewish men, and the medical procedures (circumcision, cosmetic surgery, etc.) that were blamed as their cause and/or touted as their cure.

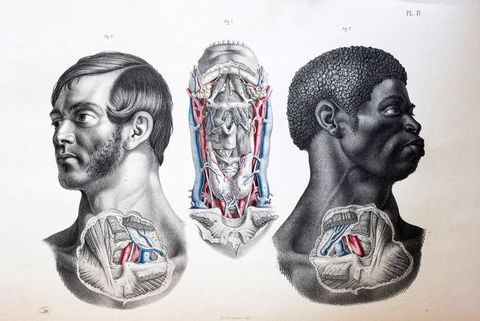

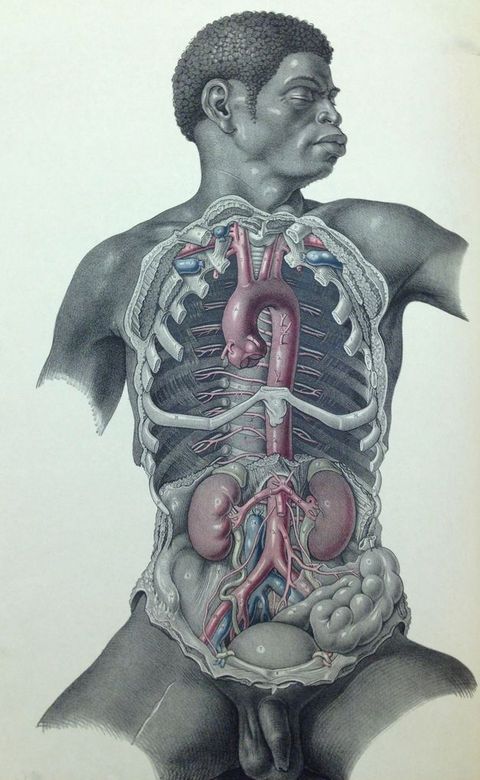

Black Anatomy

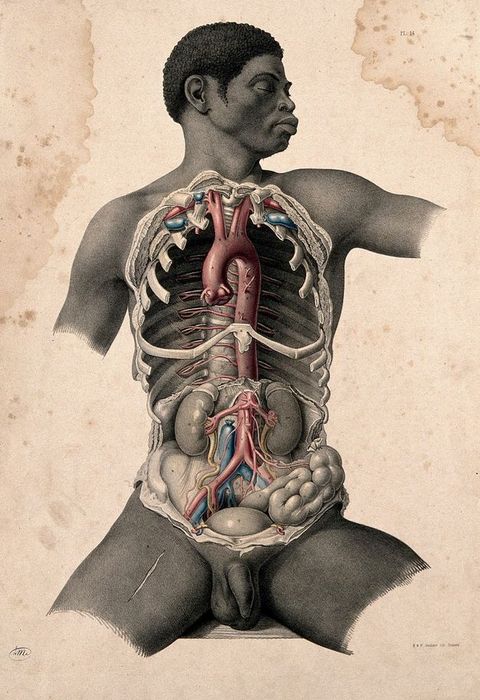

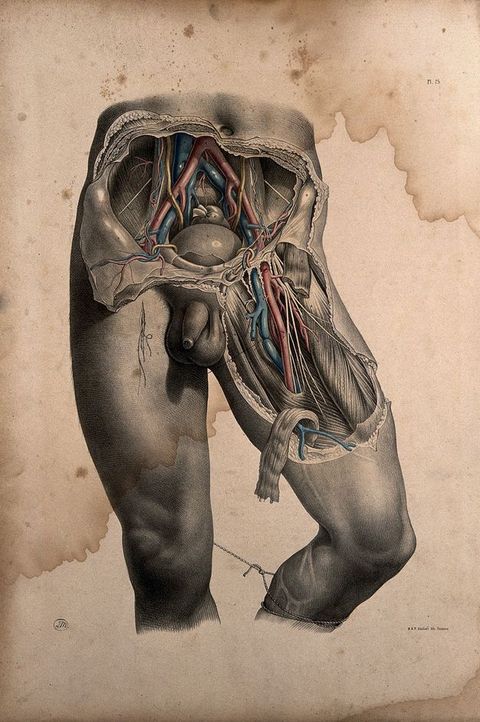

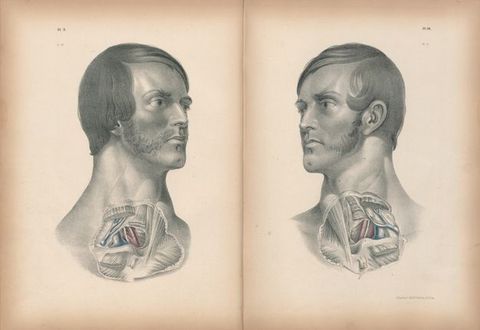

What distinguishes Maclise’s Surgical Anatomy from other elaborately illustrated anatomical and surgical productions from around this date is the inclusion of illustrations of the aestheticised body of a dissected Black man.42 The dissected Black cadaver is depicted in Plate 5 (see fig. 7) and Plate 14 (see fig. 8) of the first British edition (1851), and Plate 4 (fig. 18) and Plate 24 (fig. 19) of the second British edition. It is also possible that it is the Black man’s dissected abdomen that appears in Plate 25 of the first British edition (fig. 20).43 In Plate 14, the man has a cut on the inside of his right thigh, which appears to have been sutured in Plate 25 (this is the only illustration with stitches in that spot).

42

Significantly, the Black man in the British editions of Surgical Anatomy is transformed into a white man in all American editions of the same atlas, his skin having been lightened and his racial identity whitewashed. In the American version of Plate 5, rather than showing a white man and a Black man facing away from each other, we are presented with two versions of the same white man facing towards each other (fig. 21).44 In the American version of Plate 14, the tone of the figure’s skin is lightened and his head is cropped out of the picture, giving the impression that we are looking at the anatomy of a white man (fig. 22).45 In other words, in the American editions of Maclise’s atlas, the Black man’s anatomy is shown as a white man’s anatomy. This is a remarkable example of the whitewashing of racial difference in anatomical publications. Maclise, or, more likely his American publishers, Blanchard and Lea of Philadelphia, must have calculated that Plates 5 and 14 in their original form were too inflammatory for the American scientific community, especially in the South where slavery was still being practised.46

44

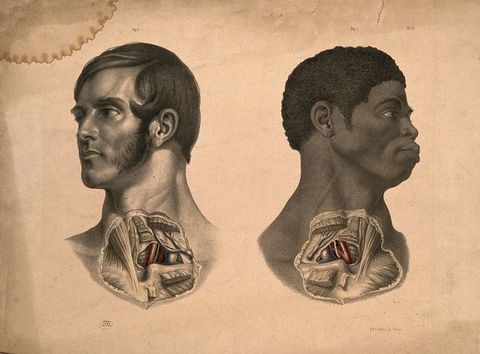

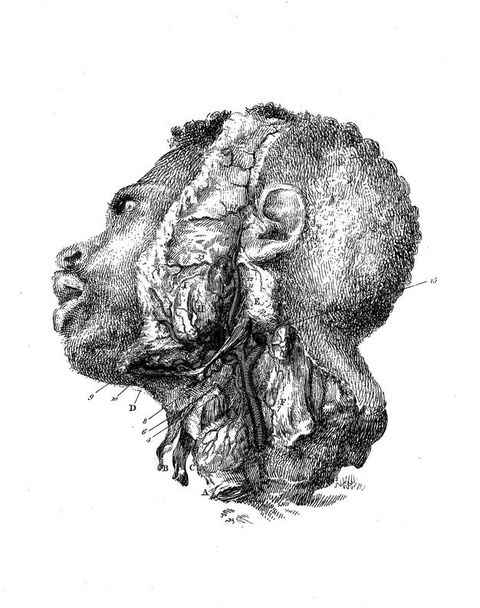

The only precedents that I have been able to find for Maclise’s illustrations of an anatomised Black man in an anatomical or surgical production appear in two publications by Charles Bell (1774–1842): Engravings of the Arteries (1811) and Illustrations of the Great Operations of Surgery (1821).47 Like Maclise, Bell was a surgeon-anatomist who produced both the text and images for his publications.48 In the third British edition (1811) of Bell’s Engravings of the Arteries, a Black figure appears in an illustration of the carotid artery (fig. 23).49 The race of the figure is referenced in the accompanying text: “Finding in the head of this black the most common and regular distribution of the branches of the Carotid Artery, I took this sketch from it.”50 This statement makes clear that the image was made from direct observation. It also justifies Bell’s use of a Black man’s anatomy by explaining that his carotid artery is standard—it presents the “most common and regular distribution of the branches”. In Illustrations of the Great Operations of Surgery, a different Black man appears in an illustration of trepanation (fig. 24).51 The illustration shows “the wound after the operation has been performed, the trephine having been applied, and the shattered bones removed”.52 Additionally, there is a sketch—a sketch within a sketch—of the fractured bone. With the bed sheets pulled right up to the bottom of his chin, the man turns his head to reveal a large, red, flower-like, gaping wound where the trephine bore down into his skull. His expression betrays no pain and suffering—perhaps the operation has provided some relief—but there is blood behind his ear and on the cloth under his neck.

47

There are similarities between Bell’s depiction of the Black man in Engravings of the Arteries and his depiction of the Black man in Illustrations of the Great Operations of Surgery. Both have backward-sloping foreheads, tightly curled hair, and stubble. While the men face in different directions, the angles of their heads are the same. The main difference is that in Illustrations of the Great Operations of Surgery the man is still alive. The dissected Black corpse in Engravings of the Arteries has his eyes and mouth open, as if suspended in the moment of his last breath. In Illustrations of the Great Operations of Surgery, the man’s eyes are open and his mouth is closed—he is silent but alert. Although the operation appears to have been successful, it is tempting to imagine it going a different way, and the unfortunate patient in Illustrations of the Great Operations of Surgery ending up a dissected cadaver in one of Bell’s anatomical publications. In Possessing the Dead, MacDonald notes that, following the passing of the Anatomy Act, hospitals became a primary (legal) source of corpses for dissection.53 Bell produced his publications before the Anatomy Act was passed, hence the corpses that he dissected would have been either executed criminals or obtained via the black market in human remains (i.e. grave robbing and/or “burking”).54 Maclise, who produced his texts after the Anatomy Act was passed, would have had access to the unclaimed bodies of those who died in public institutions: hospitals, poorhouses, asylums, etc. Put differently, the Black man in Bell’s Engravings of the Arteries was likely executed, murdered, and/or exhumed; the Black man in Maclise’s Surgical Anatomy presumably died poor and without family.

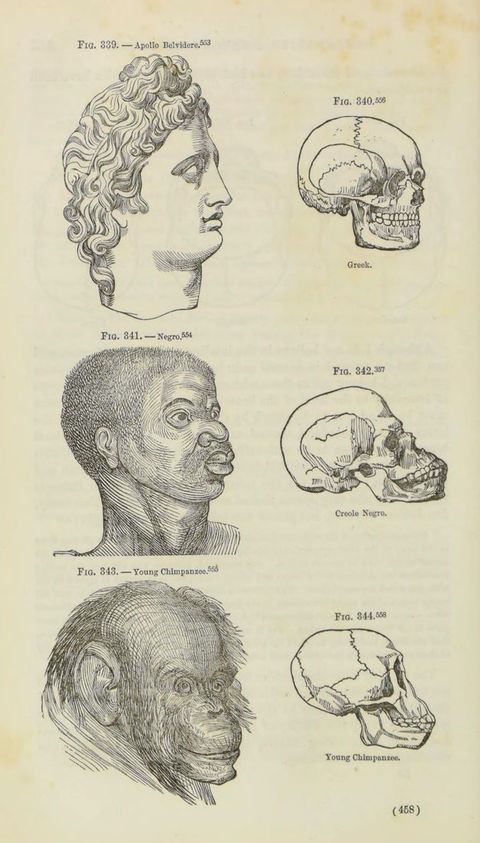

53While non-white bodies are almost entirely absent from general anatomical treatises, depictions and descriptions of the anatomical structures of non-white bodies are a ubiquitous presence in ethnographic and anthropological texts from the nineteenth century. To cite one particularly shocking example, Josiah Nott and George Gliddon’s infamous and influential American polygenisist text, Types of Mankind (1854), includes an illustration comparing the faces and skulls of the “Apollo Belvedere”/“Greek”, “Negro”/“Creole Negro”, and “Young Chimpanzee” (fig. 25).55 The heads and skulls are organised one above the other to make clear the racial hierarchy being presented: Europeans above Africans above primates. The sculpted head of the Apollo Belvedere is the whitest and has the smallest facial angle, as per Pieter Camper’s eighteenth-century system of facial measurements.56 Significantly, despite their placement on the page, the facial angle of the skull of the Black man is presented as the largest—larger even than that of the chimpanzee. It is purposefully tipped back to overemphasise the facial angle, in contrast to the skulls above and below it, which are more upright. In fact, the backward slope of the Black man’s skull is so pronounced that it does not even bear a structural resemblance to his head beside it.57 Finally, the head of the chimpanzee has a larger and more pronounced forehead than the Black man’s, the implication being that races with darker skin are less intelligent even than apes.

55

Although Bell’s illustration of trepanation in Illustrations of the Great Operations of Surgery shows the brain and skull of a Black man, it represents a departure from the kinds of racialised pictures of brains and skulls that appeared in ethnographic texts at the time. This is because the Black man’s brain and skull are not isolated from the rest of his body and therefore cannot be measured and weighed. Furthermore, race goes unmentioned in the explanatory text. Significantly, on 9 June 1836, Tiedemann presented a paper to the Royal Society, which refuted the proposition that the brains of “Negros” were smaller than those of Europeans. In his discussion of the “Weight of the Brain of a Negro”, he stated:

58Camper’s assertion, that the facial angle is smaller in the Negro than in the European, has led many anatomists to the supposition than the Negro has a less quantity of brain than the European. There are but few observations on the weight of the brain of the Negro, and these do not agree with this supposition.58

Later, he revealed that, “by measuring the cavity of the skull of Negroes and men of the Caucasian, Mongolian, American, and Malayan races”, he was able to show “that the brain of the Negro is as large as that of the European and other nations”.59

59In Races of Men: A Fragment (1851), the influential anatomist Robert Knox objected to “the contrary opinion professed by Dr Tiedemann respecting the great size of some African skulls”, stating: “I feel disposed to think that there must be a physical and, consequently, a psychological inferiority in the dark races generally”.60 Knox devoted an entire chapter of The Races of Men to “The Dark Races of Men”, in which he argued that “[s]ince the earliest times, then, the dark races have been the slaves of their fairer brethren”.61 This was because of the “obvious physical inferiority of the Negro”.62 Knox contended that the darker races were inferior “as regards mere physical strength”, “in size of brain”, in “the form of the skull” and its placement on the neck, and in “the texture of the brain”.63 He also stated that “the whole shape of the skeleton differs from ours, and so also I find do the forms of almost every muscle of the body”.64 For Knox, racial difference went as deep as the skeleton and muscles.

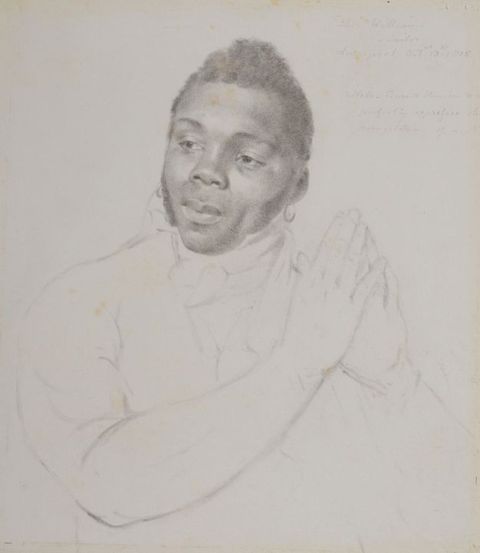

60In contradistinction to Knox’s polygenist conception of racial difference, which emphasised the permanence and inferiority of Black anatomy, the Black figure in Maclise’s Surgical Anatomy constitutes an exemplary, even idealised, anatomical specimen. (The Races of Men was published in the same year as the complete first edition of Surgical Anatomy.) In Plate 5 of Surgical Anatomy, “The Surgical Dissection of the Sterno-Clavicular or Tracheal Region, and the relative position of its main blood vessels, nerves [, &c] etc.”, Maclise depicted men of different races facing away from each other (see fig. 7). But when one penetrates below the surface of the skin, through what appears to be a window or portal to the anatomy beneath, one finds the same anatomical structures rendered in the same schematised colours. This is not an image of racialised anatomy; this is a depiction of “universal anatomy”. The Black figure’s head is turned to reveal an indentation on his earlobe, suggestive of an ear piercing.65 This detail opens up the possibility that the Black man in Maclise’s atlas is a sailor. A drawing by John Downman from 1815 of Thomas Williams, a Black Sailor shows the sitter with his hands positioned in a prayer-like gesture, and his head angled towards the left to reveal a hooped earring in his left earlobe (fig. 26). Another possibility is that the ear piercing in Plate 5 of Maclise’s atlas is a sign of the Black figure’s exoticism. In The Secret of England’s Greatness (ca. 1862–1863) by Thomas Jones Barker, Queen Victoria presents a Bible—that is, the secret of England’s greatness—to an African ambassador or prince (fig. 27). The African bows before the English sovereign, extending his left arm to receive the gift. Both Victoria and the African prince wear light-coloured garments, and both have feathers as part of their headpieces. They also both wear jewels, indicating their shared royal status. But the jewellery worn by the African prince, in particular his large hoop earring, marks him out as different from the other (white) men in the scene.66

65

We see more of the Black man in Plate 14 of Surgical Anatomy, “The Surgical Dissection of the First, Second, Third, and Fourth Layers of the Inguinal Regions, in connection with those of the Thigh” (see fig. 8). The only reference to the dissecting table is the grain of the wood seen on the bench between his thighs beneath his scrotum. The figure’s eyes are closed tightly, his nostrils slightly flared, and his lips pressed together. His torso faces forward, but his head is turned to the right. The turn of his head allows the viewer to see his pronounced jawline, the shape of his skull, and the angle of his profile. At this time, the jaw, facial angle, and skull were all subjects of examination by ethnographers and anthropologists concerned with the study of racial difference. But Maclise’s illustration combines a racialised exterior with “typical” anatomy, to use Bell’s term. The Black cadaver is depicted with dark skin and tightly curled dark hair, which were recognised at the time as characteristics of the “Negroid Type”.67 He also exhibits individualising features, including the previously noted cut on the inside of his right thigh. Where the cut appears and the dark skin is torn, light flesh is revealed. Additionally, the torn and turned-back flesh that produces a jagged uneven line along the base of the figure’s torso is light in tone, as are the broken bones of his ribcage and some of his internal organs. This is the case in other plates too, but in Plate 14 there is a more obvious contrast between the dark exterior and light interior of the body. While the exterior of the body is Black, the interior is depicted in the standardised colour scheme of anatomical illustration (red for arteries and blue for veins). Hence, the internal organs are presented as raceless—a marked departure from the racialised presentations of anatomy that were being advanced in ethnography and anthropology at the time.68

67Black Apollo

The appearance of a Black cadaver in the British editions of Maclise’s Surgical Anatomy, and his disappearance from the American editions, raises a series of poignant questions about the often-overlooked issue of race in nineteenth-century dissecting rooms: how likely was it that an anatomist or artist in mid-century Britain or America would have encountered a non-white cadaver on the dissecting table? Would a Black cadaver have been desirable, or were other factors more important such as the age and physical condition of the body? At the same time, one needs to remain mindful of the limitations of relying on an image such as Plate 14 for historical evidence. In Black Victorians, Jan Marsh offers the following warning:

69In itself, a display of black figures in visual culture is not a history of the black presence in Britain from 1800–1900. Still less is it a history of black experience. It is even difficult to say what relation the visual record bears to historical actuality in demographic or social terms, since few population estimates or first-hand testimonies exist.69

It is difficult to ascertain what relation Plate 14 bears to the realities of Black experience in nineteenth-century anatomy theatres. After all, it is a highly sanitised and aestheticised representation of the dissection of a Black body. Thought of differently, as an aestheticised depiction of a dissected Black male body, Plate 14 has much to reveal to us about the often-messy relationship between aesthetics, dissection, and race in mid-nineteenth-century Britain.

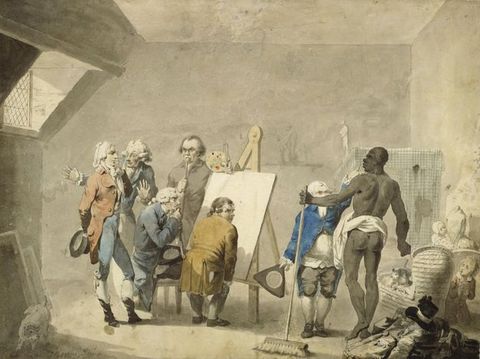

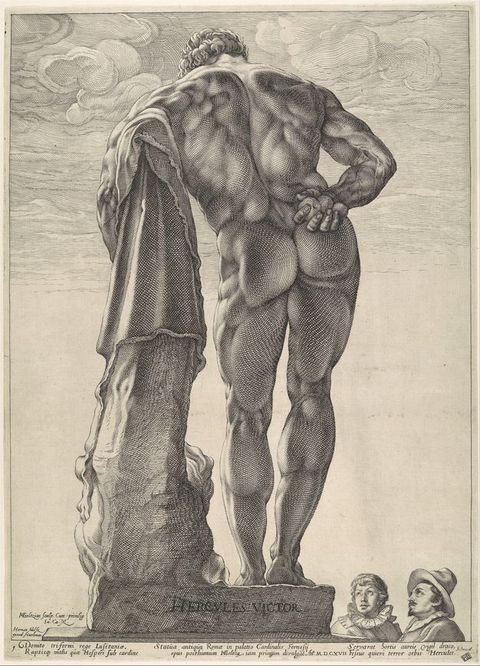

In Plate 14, the man’s arms fade out at the biceps, but we are presented with enough information to be able to recognise that his left arm is outstretched and his right arm lowered. The positioning of the arms, along with the turn of the head, gives this figure the appearance of the Belvedere Torso or Apollo Belvedere.70 That said, despite the classicising positioning, as a picture of a dead and dissected Black body presented for examination by presumably white viewers, it feels far from being a “Black Apollo”. The relationship of white male viewers to exposed Black male bodies was satirised by John Bourne in Meeting of Connoisseurs (ca. 1807) (fig. 28). Bourne’s watercolour pokes fun at the fashion for Black models at the time by showing a group of white male artist-connoisseurs in an artist’s studio surveying the unclad body of a Black male model. The comedy of the images lies in the fact that these are connoisseurs of naked Black men, rather than “Art”.71 In contrast to the short, stubby, and scrawny bodies of the pasty white gentlemen-connoisseurs, the unclad Black model boasts an impressive physique. Seeing him from behind, we are able to admire his muscular back, legs, and arm, and to appreciate his remarkably taut buttocks. So taut are his buttocks that he even resembles The Farnese Hercules (fig. 29). Some white fabric around his waist could or could not be covering his genitals—only the connoisseurs and artist know (although, from the concentrated stare of the man crouched in front of the canvas, and the suggestive gesture of the artist with his cane in his mouth, it would seem not). The model’s legs are in contrapposto, with his left foot slightly raised off the ground. His outstretched arm, bent at the elbow, rests on a broom handle for support, an alternative no doubt to the ropes that were often used to keep the limbs of life models (and cadavers) in place. A comically short and pudgy connoisseur has his hand under the Black man’s chin. He could be moving the man’s face into the correct position of the Apollo Belvedere, surveying the model’s profile, enjoying a titillating caress of the Black man’s flesh, or all of the above. Aris Sarafianos writes of this image that its satirical tone stems from “a growing sense of the intellectual shakiness and triteness of the comparison between black people and the Apollo rather than … from the ‘unusual’ nature of this analogy”.72 Furthermore, the way in which the exposed body of the Black man is closely scrutinised by the white connoisseurs invokes the scopic economy of the Atlantic slave trade and conjures up images of American slave auctions.73

70

The gesture of a muscular Black man with one arm outstretched and the other lowered appeared in major artworks from around this date, works of which Maclise would have no doubt been aware.74 At the apex of Théodore Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa (1819), for example, a Black man waves red and white fabric to attract the attention of a boat in the distance (fig. 30). The hope of salvation for these shipwrecked wretches lies in the Black man’s gesture—in his strength, energy, and determination to keep his arm outstretched. Similarly, in one of Daniel Maclise’s designs for the Royal Gallery of the Palace of Westminster, The Death of Nelson Supported by Captain Hardy on the Victory at Battle of Trafalgar (completed 1865), a muscular Black man plays a seminal role in the unfolding drama (fig. 31). At the centre of the fresco, a Black figure extends his left arm and points towards Nelson’s killer. With his right hand, he touches the man beside him to alert him to the perpetrator.75 Amidst the tumult of battle, the outstretched muscular arm of the dark-skinned man stands out. As is the case in Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa, the Black man in Daniel Maclise’s scheme performs an important compositional role, with the diagonal thrust of his arm directing the viewer’s eye into the drama. Interestingly, the Black sailor depicted by Daniel Maclise has an ear piercing, just like the Black figure in Plate 5 of Joseph Maclise’s Surgical Anatomy.76

74

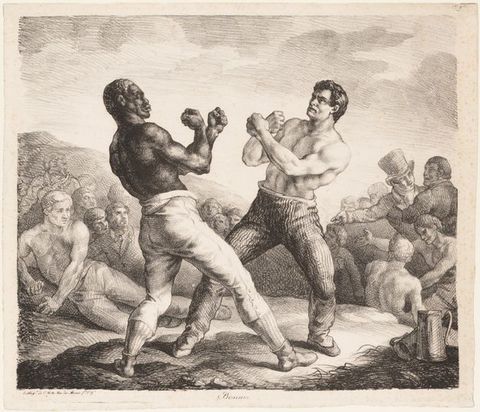

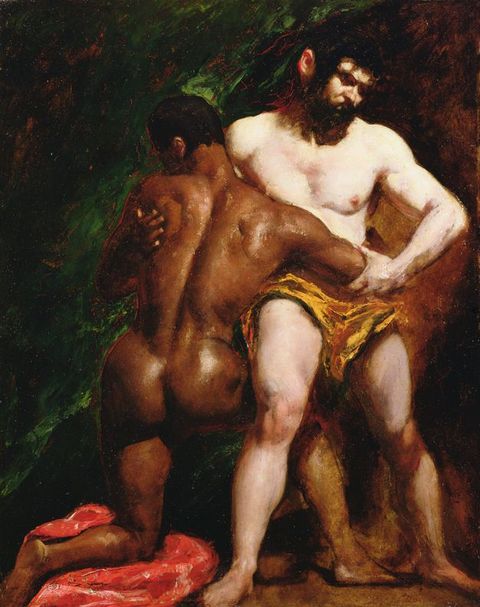

There was, of course, another reason why a Black man might extend his arm: to land a punch. By the time Maclise produced his atlas, several men of colour had achieved fame as prize-fighters in the era of bare-knuckle pugilism, Bill Richmond and Tom Molineaux foremost among them.77 As boxing was illegal for much of the nineteenth century, write Ruti Ungar and Michael Berkowitz, “[t]hose who turned to boxing as a livelihood tended to come from the lower rungs of the social ladder, and frequently they were among minority groups, such as the Irish, Jews, and Blacks”.78 Some of the most famous boxing matches—and the pictures inspired by them—pitted pugilists of different races against each other.79 The fighters in Géricault’s 1818 lithograph Les Boxeurs are generally thought to be Molineaux and Tom Cribb, the champion of England, who fought on 28 September 1811 (fig. 32).80 In Géricault’s lithograph, the muscular bodies of the boxers mirror each other—the Black boxer wears white pants and the white boxer wears black pants—their front legs forming a cross. To the left of the image, a bare-chested man assumes the pose of the Dying Gaul, reminding us once again of Smugglerius. In William Etty’s painting The Wrestlers (1840s), racially diverse, muscular male bodies are brought into even closer contact, with differently coloured flesh pushing up against each other (fig. 33). The Black wrestler is shown kneeling, right arm hooked around the white man’s torso, and front leg positioned underneath the white man’s thigh. While the white man wears a loincloth, the Black man is apparently naked, his taut shiny buttocks revealed to the viewer. Even if it was believed by many at the time that white men should win, in the images produced by Géricault and Etty the fighters seem evenly matched.81

77

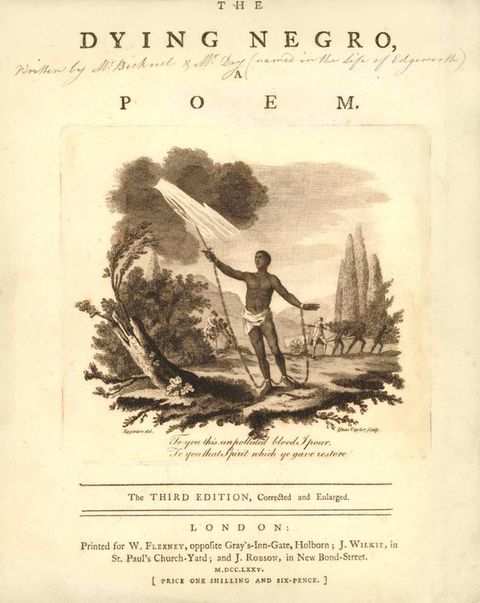

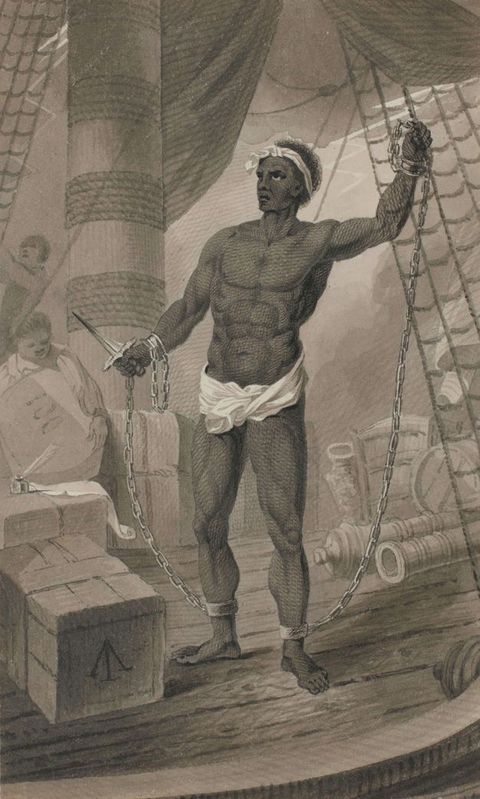

Turning once again to Plate 14 of Maclise’s Surgical Anatomy and its relationship to the Apollo Belvedere, if the anatomised Black man in Plate 14 had his legs and arms restored, would he embody the classical youth and beauty of the Apollo Belvedere, or the strength and hopelessness of The Dying Negro?82 The title page of Thomas Day’s abolitionist poem of 1775 (first published 1773) features a picturesque landscape, with a divine light piercing the dark clouds to illuminate the body of a muscular Black slave (fig. 34). In the background, three Black figures pull a wagon under the cruel mastery of a white slaveholder. Despite the chains that bind his arms and legs, the Black man in the foreground raises his right arm towards the light and, in this hand, he holds a dagger. The message conveyed is that this man would rather die than live in chains. In George Cooke’s 1793 Slave on Deck, the figure assumes a similar gesture, but now the action takes place at sea, amidst cargo, rigging, and ropes, presumably on the dreaded middle passage (fig. 35). As in Day’s image, the bound man in Cooke’s image holds a dagger, but this time it is in his lowered right hand. This makes him look less as if he is taking an oath before God, and more as if he is pledging to himself that he will escape bondage by ending his life. Additionally, in Cooke’s version, the dagger has blood on it, prompting the question of what kind of violence he might already have instigated.

82

In contrast to more familiar abolition imagery that shows enslaved men and women in unthreatening gestures of supplication and pleading such as Josiah Wedgwood’s medallion, “Am I Not a Man and a Brother?” (1787), the images by Day and Cooke present an upstanding and empowered image of the enslaved Black body. The men exhibit impressively muscular physiques, likely produced by servitude and hard labour, which associate the figures with the exemplary bodies of classical statues. Furthermore, despite the fact that the men are bound in chains, they stand in contrapposto and wear white loincloths. The loincloths conceal the men’s potentially scandalous genitals and add a classicising element. But shifting focus from the figures to what they hold—that threatening dagger—the images by Day and Cooke recall a picture that we encountered at the very outset of this article: the flayed man in Valverde’s Anatomia del corpo humano. The dagger returns us to the act of flaying. It also invokes the scalpels and other instruments depicted by Maclise in his atlas for the purpose of anatomising the human body. Above all, it allows us to imagine the excruciating and violent process by which the dark flesh of the enslaved Black man might be cut away in the production of anatomical models and illustrations for use in European and American art and medical academies.

The implied whiteness of figures in anatomical atlases works to perpetuate a series of assumptions about the normative human body, namely, that it is white, male, and classically proportioned, like the Apollo Belvedere. Ironically, there is plenty of evidence that not even classical statues, including the Apollo Belvedere, were originally white.83 The whitewashing of anatomised subjects in atlases, diagrams, and textbooks masks the fact that a significant proportion of people who ended up on dissecting tables in Britain, America, Australia, and beyond were not white. Close analysis of publications such as Maclise’s Surgical Anatomy opens up questions about the processes by which the violated bodies of the old, young, sick, pregnant, unborn, enslaved, indentured, institutionalised, imprisoned, poor, destitute, Black, Irish, and Jewish individuals who ended up on the nineteenth-century dissecting table were abstracted into objects of great aesthetic, intellectual, and monetary value. It suggests that the removal of flesh in the production of écorchés not only exposes the underlying musculature but also strips away those signifiers of non-ideal identity (dark skin, wrinkles, blemishes, scars, tattoos, and so on) in the production of ideal physical specimens. Addressing the relationship between aesthetics, dissection, and race during the nineteenth century is not a simple or straightforward task—it requires us to keep our head, follow our gut, and, on occasion, take a dagger in hand.

83Acknowledgements

This material was presented at the “Visual Culture as Historical Evidence” workshop at the Australian National University, in the Department of Art History seminar series at the University of Sydney, and as part of the School of Philosophy and Art History seminar series at the University of Essex. My thanks to organisers, convenors, and audience members for their helpful feedback. I am especially grateful to several astute readers and consultants, who have been instrumental in the development of this article and the claims contained within it: David Bronstein, Anthea Callen, Baillie Card, Sria Chatterjee, Tania Cleaves, Sander L. Gilman, Natasha Ruiz-Gómez, Alan Shroot, Sarah Victoria Turner, Robert Wellington, and the two anonymous reviewers. Thank you for the image and copyright support provided by Maisoon Rehani and British Art Studies. This project is made possible through support from the Terra Foundation for American Art.

About the author

-

Keren Rosa Hammerschlag is a lecturer in art history and curatorship in the Centre for Art History and Art Theory, School of Art and Design, at the Australian National University, Canberra. Her current research focuses on nineteenth-century anatomical illustration, and race in Victorian painting. She is the author of Frederic Leighton: Death, Mortality, Resurrection (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2015) and “Christ’s Racial Origins: Finding the Jewish Race in Victorian History Painting”, an article published in The Art Bulletin in 2021.

Footnotes

-

1

As work in the fields of Critical Race Studies and Critical Whiteness Studies reveals, “whiteness” constitutes the invisible vantage point of power and privilege. See W.E.B. DuBois, Darkwater (New York: Harcourt, Brace, and Co., 1920); Toni Morrison, Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination (New York: Vintage Books, 1993); bell hooks, Black Looks: Race and Representation (Boston, MA: South End Press, 1992); Richard Dyer, White (London: Routledge, 1997); and Robin DiAngelo, White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Race (Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 2018). ↩︎

-

2

For seminal studies of the history of Western anatomical illustration, see Londa Schiebinger, “Skeletons in the Closet: The First Illustration of a Female Skeleton in Eighteenth-Century Anatomy”, Representations 14 (1986): 42–82; K.B. Roberts and J.D.W. Tomlinson, The Fabric of the Body: European Traditions of Anatomical Illustration (Oxford: Clarendon, 1992); Ludmilla J. Jordanova and Deanna Petherbridge, The Quick and the Dead (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1997); Martin Kemp and Marina Wallace, Spectacular Bodies: The Art and Science of the Human Body from Leonardo to Now (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2000); Michael Sappol, Dream Anatomy (Bethesda, MD: National Library of Medicine, 2002); and Elizabeth Stephens, Anatomy as Spectacle: Public Exhibitions of the Body from 1700 to the Present (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2011). Gender is considered by several of these scholars, Schiebinger, Jordanova, and Stephens foremost among them, but race remains largely unexamined. In the field of art history more generally, much great work has been done on depictions of non-white subjects in terms of race. By contrast, representations of white bodies continue to be treated as just humans and are therefore exempt from scrutiny in terms of race. ↩︎

-

3

Juan Valverde de Amusco, Anatomia del corpo humano (Rome: Per Ant. Salamanca, et Antonio Lafrerj, 1560), 64. ↩︎

-

4

A version of this figure appears as Saint Bartholomew in Michelangelo’s Last Judgement (1536–1541). The artist’s likeness is recognisable in the flayed skin held by the martyred Apostle. ↩︎

-

5

For a discussion of the study of anatomy in the French art academy during the nineteenth century, see Anthea Callen, “The Body and Difference: Anatomy Training at the École des Beaux-Arts in P aris in the Later Nineteenth Century”, Art History 20, no. 10 (1997): 23–60. ↩︎

-

6

Meredith Gamer, “The Smugglerius, Re-Viewed”, Sculpture Journal 28, no. 3 (2019): 331–344. ↩︎

-

7

An écorché is a drawing or sculpture of the human body with the skin removed. ↩︎

-

8

For more on this, see Mechthild Fend, “Seeing Through Skin”, Chapter 6 in Fleshing Out Surfaces: Skin in French Art and Medicine 1650–1850 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2017), 193–234. The first female student was admitted to the RA Schools in 1860. ↩︎

-

9

John Marshall, Anatomy for Artists, illustrated with 200 original drawings by J.S. Cuthbert, engraved by J. and G. Nicholls (London: Smith, Elder and Co, 1878). ↩︎

-

10

It should be noted that this is an unusual image. As Anthea Callen and others have recognised, it was primarily the ideal male body that was the focus of anatomical study. In Looking at Men: Art, Anatomy and the Modern Male Body, Callen writes: “In art academies, anatomical studies of the human body had, from the very first, been constructed around notions of a classical ideal … The human body in question was, of course, male”; Anthea Callen, Looking at Men: Art, Anatomy and the Modern Male Body (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2018), 14. ↩︎

-

11

Helen MacDonald, Human Remains: Dissection and Its Histories (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2005), 54. ↩︎

-

12

MacDonald, Human Remains, 53. ↩︎

-

13

MacDonald, Human Remains, 53. ↩︎

-

14

John Harley Warner describes “the dissected” as “people whose class, ethnicity, race, or poverty made them vulnerable to dissection”; John Harley Warner, “Witnessing Dissection: Photography, Medicine, and American Culture”, in Dissection: Photographs of a Rite of Passage in American Medicine 1880–1930, ed. John Harley Warner and James M. Edmonson (New York: Blast Books, 2009), 15. ↩︎

-

15

The Oxford English Dictionary defines “specimen” as: “An example, instance, or illustration of something, from which the character of the whole may be inferred; A single thing selected or regarded as typical of its class; a part or piece of something taken as representative of the whole; An animal, plant, or mineral, a part or portion of some substance or organism, etc., serving as an example of the thing in question for purposes of investigation or scientific study” [electronic resource], 2nd edn, ed. John A. Simpson and Edmund S.C. Weiner (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989). ↩︎

-

16

“Maclise, Joseph (1813–1880)”, Plarr’s Lives of the Fellows, Royal College of Surgeons of England, http://livesonline.rcseng.ac.uk/biogs/E002613b.htm. ↩︎

-

17

Richard Quain, The Anatomy of the Arteries of the Human Body with its Applications to Pathology and Operative Surgery in Lithographic Drawings with Practical Commentaries: The Drawings from Nature and on Stone by Joseph Maclise (London: Taylor and Walton, 1844); Joseph Maclise, Comparative Osteology being Morphological Studies to Demonstrate the Archetype Skeleton of Vertebrated Animals (London: Taylor and Walton, 1847); and Joseph Maclise, On Dislocations and Fractures (London: John Churchill, 1859). ↩︎

-

18

Quain, The Anatomy of the Arteries of the Human Body, 1844. ↩︎

-

19

Joseph Maclise, preface to Surgical Anatomy (Philadelphia, PA: Blanchard and Lea, 1851), v. ↩︎

-

20

The question of who the audience for Maclise’s atlas were is addressed by Michael Sappol and Naomi Slipp in their contributions to this One Object feature for British Art Studies, see Michael Sappol, “Mr Joseph Maclise and the Epistemology of the Anatomical Closet”, British Art Studies 20 (July 2021), DOI:10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-20/msappol and Naomi Slipp, “‘It Should Be On Every Surgeon’s Table’: The Reception and Adoption of Joseph Maclise’s Surgical Anatomy (1851) in the United States”, British Art Studies 20 (July 2021), DOI:10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-20/nslipp. Slipp, for instance, demonstrates that Maclise’s Surgical Anatomy was widely used in American medical schools during the second half of the nineteenth century. ↩︎

-

21

This devise was used more extensively by Maclise in his illustrations for Quain’s The Anatomy of the Arteries of the Human Body. See, for example, Plates 8, 28, 52, and 62. ↩︎

-

22

My thanks to Karen Myer, librarian at the History of Medicine Library, Royal Australasian College of Physicians, for confirming this detail. ↩︎

-

23

Ludmilla J. Jordanova, “Gender, Generation and Science: William Hunter’s Obstetrical Atlas”, in William Hunter and the Eighteenth-Century Medical World, ed. William F. Bynum and Roy Porter (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985), 385–412. ↩︎

-

24

An Act for regulating Schools of Anatomy [1st August 1832], The National Archive, UK. https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/resources/body-snatchers/source-four-the-anatomy-act-1832/ [emphasis added]. ↩︎

-

25

At the time of writing this article, I have not been granted access to any nineteenth-century cadaver books in the UK or Australia. Nonetheless, curator Rohan Long has generously consulted the incoming specimen books from the 1930s, currently in the collection of the Harry Brooks Allen Museum of Anatomy and Pathology, University of Melbourne, and confirmed that the following information is included: No. (the number, as entered, in the book’s listings), Name of Doctor, Date, Patient, Whence Obtained, Disposed. ↩︎

-

26

“Spicula”, Speculum 40 (May 1898), 27. This is noted by Ross L. Jones in Humanity’s Mirror: 150 Years of Anatomy in Melbourne (Melbourne: Haddington Press, 2007). For more on the history of dissection in Australia, see Ross L. Jones, “Cadavers and the Social Dimension of Dissection”, in The Body Divided: Human Beings and Human “Material” in Modern Medical History, ed. Sarah Ferber and Sally Wilde (Farnham: Ashgate, 2011), 29–52. ↩︎

-

27

Ludmilla J. Jordanova, Sexual Visions: Images of Gender in Science and Medicine (London: Harvester Wheatsheaf, 1989). ↩︎

-

28

Plates of the Arteries of the Human Body, after Friedrich Tiedemann, Engraved by E. Mitchell, under the superintendency of Thomas Wharton Jones. The explanatory references translated from the original Latin, with additional notes by Dr Knox (Edinburgh: MacLachlan, Stewart, 1829). ↩︎

-

29

Tiedemann, Plates of the Arteries of the Human Body, 2 [emphasis added]. ↩︎

-

30

Tiedemann, Plates of the Arteries of the Human Body, 3. ↩︎

-

31

Dr Alan Shroot is convinced that there is evidence here of circumcision. ↩︎

-

32

My thanks to Sander Gilman for these thoughts. The male genitals are shown in this way in other illustrations in Maclise’s Surgical Anatomy, but this is the only illustration in the atlas that includes both the potentially circumcised penis and the figure’s face. ↩︎

-

33

Sander L. Gilman, “Cutting it Short: James Boon’s Circumcision”, Anthropological Quarterly 90, no. 4 (2017): 1033. ↩︎

-

34

Thank you to Annette Wickham for bringing this to my attention. ↩︎

-

35

For a discussion of the crime and the anti-Semitic backlash it caused, see Todd M. Endelman, The Jews of Georgian England, 1714–1830: Tradition and Change in a Liberal Society (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 1999), 198–203. ↩︎

-

36

A third écorché, the Anatomical Crucifixion (1801), was made from the body of an Irishman, James Legg. ↩︎

-

37

Accession number GLAHM: 121404 (previously Series Number 43.52), http://collections.gla.ac.uk/#/details/ecatalogue/145390. ↩︎

-

38

Catalogue of Anatomical Preparations in the Hunterian Museum, compiled by George Fordyce, David Pitcairn, and Charles Combe (Glasgow: University of Glasgow, 1840), 131. Nicky Reeves, curator of scientific and medical history collections at the Hunterian, drew my attention to the fact that the 1900 printed Catalogue of the Anatomical Pathological Preparations of Dr William Hunter in the Hunterian Museum, University of Glasgow quotes the description of the specimen as being “the penis of a Jew”, but then describes at greater length its status as a specimen/exemplar of chancres and syphilis. ↩︎

-

39

More recently, there have been discussions around circumcision and HIV transmission. Robert Darby considers the parallels between responses to syphilis in nineteenth-century Britain and HIV/AIDS in contemporary Africa, in “Syphilis 1855 and HIV-AIDS 2007: Historical Reflections on the Tendency to Blame Human Anatomy for the Action of Micro-Organisms”, Global Public Health 10, nos. 5–6 (2015): 573–588. For a critique of Darby’s position, see Brian J. Morris et al., “Male Circumcision to Prevent Syphilis in 1855 and HIV in 1986 is Supported by the Accumulated Scientific Evidence to 2015: Response to Darby”, Global Public Health 12, no. 10 (2017): 1315–1333. ↩︎

-

40

Jonathan Hutchinson, “On the Influence of Circumcision in Preventing Syphilis”, Medical Times and Gazette 11, no. 283 (1 December 1855): 542–543. ↩︎

-

41

E. Harding Freeland, “Circumcision as a Preventative of Syphilis and Other Disorders”, The Lancet 156, no. 4035 (29 December 1900), 1870. For more on this, see Robert Darby, “‘Where Doctors Differ’: The Debate on Circumcision as a Protection against Syphilis, 1855–1914”, Journal of the Society for the Social History of Medicine 16, no. 1 (2003): 57–78. ↩︎

-

42

Contemporaneous examples of surgical atlases include: Thomas Morton and William Cadge, The Surgical Anatomy of the Principal Regions of the Human Body (London: Taylor, Walton, & Maberly, 1850); George Viner Ellis and G.H. Ford, Illustrations of Dissections (London: James Walton, 1867); and Francis Sibson, Medical Anatomy, or Illustrations of the Relative Position and Movements of the Internal Organs (London: John Churchill, 1869). ↩︎

-

43

It appears as Plate 48 in the second British edition; Joseph Maclise, Surgical Anatomy, 2nd edn (London: John Churchill, 1856). ↩︎

-

44

It appears as Plates 9 and 10 in the 1851 American edition of Maclise, Surgical Anatomy. ↩︎

-

45

It appears as Plate 25 in the 1851 American edition of Maclise, Surgical Anatomy. ↩︎

-

46

I examine in depth the significance of the whitewashing of racial difference in the American versions of Maclise’s atlas in “Drawing Racial Comparisons in Nineteenth-Century British and American Anatomical Atlases”, in Nancy Rose Marshall, ed., Victorian Science and Imagery: Representation and Knowledge in Nineteenth-Century Visual Culture (Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, forthcoming, July 2021). ↩︎

-

47

Charles Bell, Engravings of the Arteries; Illustrating the Second Volume of the Anatomy of the Human Body, and Serving as An Introduction to the Surgery of the Arteries, 3rd edn (London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown, Paternoster-Row; and T. Cadell and W. Davies, Strand, 1811); and Charles Bell, Illustrations of the Great Operations of Surgery, Trepan, Hernia, Amputation, Aneurism, and Lithotomy (London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown, 1821). ↩︎

-

48

Maclise makes explicit reference to Bell by including a depiction of a book with “C.Bell” inscribed on the spine in Plate 66 of Quain’s The Anatomy of the Arteries of the Human Body. ↩︎

-

49

In Bell, Engravings of the Arteries, it appears as Plate 4. ↩︎

-

50

Bell, Engravings of the Arteries, 11. ↩︎

-

51

Bell, Illustrations of the Great Operations of Surgery, Plate 2. A trephine or hole saw was used by surgeons for perforating the skull. ↩︎

-

52

Also included are: A. The lower flap of the integuments; B. The upper flap; C. The cranium; D. The dura mater; Bell, Illustrations of the Great Operations of Surgery, Plate 2. ↩︎

-

53

“After workhouses, British hospitals were the most important source of subjects for dissection”; Helen MacDonald, Possessing the Dead: The Artful Science of Anatomy Illustrated (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 2010), 96. ↩︎

-

54

“To burke is to kill secretly by suffocation or strangulation for the express purpose of selling the victim’s body for dissection”; Warner, “Witnessing Dissection”, 16. The expression derives from the murders committed by William Burke and William Hare in Edinburgh in 1828. Burke and Hare sold the bodies of their victims to Robert Knox for dissection. For more on this, see Ruth Richardson, Death, Dissection and the Destitute (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2000). ↩︎

-

55

Josiah C. Nott and George R. Gliddon, Types of Mankind: or, Ethnological Researches, based upon the Ancient Monuments, Paintings, Sculptures, and Crania of Races, and upon their Natural, Geographical, Philological, and Biblical History: Illustrated by Sections from the inedited papers of Samuel George Morton, and by additional contributions from Professor L. Agassiz, W. Usher, and Professor H.S. Patterson, 8th edn (Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Grambo & Co, 1860), 458. ↩︎

-

56

Camper compared the skulls of different racial types by drawing a line “along the forehead and the upper lip” and measuring the angle. He used this measurement to rank races from those exhibiting the most “beautiful lines and angles” (“an angle of 100 degrees with the horizon”, pertaining to a classical Greek head) through to the opposite end of the scale, which established the “degree of similarity between a negro and the ape”; Camper quoted in Petherbridge and Jordanova, The Quick and the Dead, 82. It is worth noting that Camper was a monogenist and his drawings were not intended to be used as registers of varying cognitive ability. “Camper’s famous diagrams were meant as value-free formal sequences recording the geometrical regularity of visual variations of anatomical structure”, writes Aris Sarafianos in “B.R. Haydon and Racial Science: The Politics of the Human Figure and the Art Profession in the Early Nineteenth Century”, Visual Culture in Britain 7 (2006): 82–83. Also see the discussion of Camper in Fend’s Fleshing Out Surfaces, 159–163. Fend recounts how, in a lecture titled “On the Origin and Colour of the Blacks”, delivered in Groningen in 1764, Camper used an “anatomical dissection to demonstrate that beyond the coloured layer just below the epidermis, humans all look fairly alike” (160). Another relevant text is David Bindman, Ape to Apollo: Aesthetics and the Idea of Race in the 18th Century (London: Reaktion Books, 2002). ↩︎

-

57

My thanks to Anthea Callen for these observations. ↩︎

-

58

Frederick Tiedemann, “On the Brain of the Negro, Compared with That of the European and the Orang-Outang”, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 126, no. 2 (1836), 504. ↩︎

-

59

Tiedemann, “On the Brain of the Negro”, 504. ↩︎

-

60

Robert Knox, The Races of Men: A Fragment (Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Blanchard, 1850), 151. Despite holding contrary positions on racial physiognomy, the English edition of Tiedemann’s Plates of the Arteries of the Human Body was translated from the original Latin, with additional notes by Dr Knox. ↩︎

-

61

Knox, The Races of Men, 150. ↩︎

-

62

Knox, The Races of Men, 151. ↩︎

-

63

Knox, The Races of Men, 151. ↩︎

-

64

Knox, The Races of Men, 152. ↩︎

-

65

No other corpse in the atlas has this individualising feature, not even the same Black man in Plate 14. ↩︎

-

66

In The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex, Charles Darwin associated a juvenile love of ornaments and shiny things with animals and “savages”. He even claimed that “[j]udging from the hideous ornaments, and the equally hideous music admired by most savages, it might be urged that their aesthetic faculty was not so highly developed as in certain animals, for instance, as in birds”. Charles Darwin, The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex, 2nd edn, revised and augmented (London: John Murray, 1883), 93. ↩︎

-

67

For one of many descriptions of this type, see “II. The Negroid Type”, in T.H. Huxley, “On the Geographical Distribution of the Chief Modifications of Mankind”, Journal of the Ethnological Society of London 2, no. 4 (1870): 405–407. ↩︎

-

68

The unreliability of skin, hair, and eye colour as markers of racial difference led many nineteenth-century race scientists to locate racial difference in the deeper anatomical organs and structures of the human body. ↩︎

-

69

Jan Marsh, “The Black Presence in British Art 1800–1900: Introduction and Overview”, in Black Victorians: Black People in British Art, 1800–1900, ed. Jan Marsh (Aldershot: Lund Humphries, 2005), 14. ↩︎

-

70

Sarafianos recounts two instances in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century in which a non-white body was described as resembling the Apollo Belvedere and vice versa: Benjamin West’s exclamation upon first seeing the Apollo Belvedere in 1760, “My God, how like it is to a young Mohawk warrior!'”; and Thomas Winterbottom’s claim in An Account of the Native Africans in the Neighbourhood of Sierra Leone (1803) that “Among those of them [the Fulas], I saw a youth whose features were exactly of the Grecian mould, and whose person might have afforded to the statuary a model of the Apollo Belvidere” (Vol. 2, 200); quoted in Sarafianos, “B.R. Haydon and Racial Science”, 96 and 88–89. ↩︎

-

71

Hugh Honour observes that “Blacks were increasingly employed by artists as models from the early nineteenth century despite the common association of their colour and physiognomy with ugliness”. Hugh Honour, The Image of the Black in Western Art, Vol. IV: From the American Revolution to World War I, Part II: Black Models and White Myths (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1989), 21. ↩︎

-

72

Sarafianos, “B.R. Haydon and Racial Science”, 95. ↩︎

-

73

For a study of nineteenth-century depictions of American slave auctions, including their exhibition in Britain, see Maurie D. McInnis, Slaves Waiting for Sale: Abolitionist Art and the American Slave Trade (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2011). ↩︎

-

74

We know that Daniel Maclise saw Théodore Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa (1819) on his first visit to France in 1830. Leon Litvack, “Continental Art and the ‘Cockneyfied Corkonian’: German and French Influences on Daniel Maclise”, in Daniel Maclise 1806–1870: Romancing the Past, ed. Peter Murray (Cork: Crawford Art Gallery and Gandon Editions, 2008), 200. ↩︎

-

75

My thanks to Anthea Callen for drawing my attention to this detail. ↩︎

-

76

In Daniel Maclise’s The Death of Nelson Supported by Captain Hardy on the Victory at Battle of Trafalgar, a second Black figure also wears an earring, as do several white sailors. My thanks to Grace Saull, Assistant Curator, Parliamentary Art Collection, for confirming these details. In contrast to the strength and nobility embodied in the central Black figure, a second Black figure to the left of the scene is depicted as more feminised. This figure is positioned near to two women. He bends over to give succour (brandy, perhaps) to a wounded sailor and, in so doing, appears more hunched over, with rounded shoulders, protruding neck, and furrowed brow. ↩︎

-

77

“Boxing, or—as it was called at that time—pugilism, emerged as a popular form of entertainment in England in the second half of the eighteenth century”; Ruti Ungar and Michael Berkowitz, “From Daniel Mendoza to Amir Khan: Minority Boxers in Britain”, in Fighting Back? Jewish and Black Boxers in Britain, ed. Michael Berkowitz and Ruti Ungar (London: University College London, 2007), 4. Richmond was born in New York, the son of former slaves. Molineaux was an ex-slave from Virginia, who found asylum in Britain. ↩︎

-

78

Ungar and Berkowitz, “From Daniel Mendoza to Amir Khan”, 4. ↩︎

-

79

Adam Chill, “The Performance and Marketing of Minority Identity in Late Georgian Boxing”, in Fighting Back? Jewish and Black Boxers in Britain, ed. Michael Berkowitz and Ruti Ungar (London: University College London, 2007), 44. See also Callen’s discussion of “Contested Anatomies: Gerdy, Géricault, Etty, Bellows and the Mixed-Race Fight”, in Callen, Looking at Men, 85–91. ↩︎

-

80

Kasia Boddy, Boxing: A Cultural History (London: Reaktion Books, 2008), 72. ↩︎

-

81

Writes Boddy, “In Géricault’s lithograph, he [the Black boxer/Molineaux] is not only complementary but absolutely equal to his opponent; here, it seems possible that he might win”; Boddy, Boxing, 73. In the mid-1880s, the “mulatto” pugilist, Ben Bailey, was photographed by Eadweard Muybridge for Animal Locomotion. He appears in front of an anthropometric grid performing various actions, including punching the air; see Elspeth H. Brown, “Racialising the Virile Body: Eadweard Muybridge’s Locomotion Studies 1883–1887”, Gender and History 17, no. 3 (November 2005): 627–656. ↩︎

-

82

Thomas Day, The Dying Negro: A Poem, 3rd edn (London: printed for W. Flexney, opposite Gray’s-Inn-Gate, Holborn; J. Wilkie, in St. Paul’s Church-Yard; and J. Robson, in New Bond Street, 1775). ↩︎

-

83

Thank you to Robert Wellington for this point. See Vinzenz Brinkmann, Renée Dreyfus, and Ulrike Koch-Brinkmann, eds., Gods in Color: Polychromy in the Ancient World (San Francisco, CA: Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco, Legion of Honour, 2017). The fact that we continue to view antique statues, including the Apollo Belvedere, as white, despite the fact that they were originally polychrome, is discussed by Sarah E. Bond in her op-editorials for Forbes and Hyperallergic: “Whitewashing Ancient Statues: Whiteness, Racism and Color in the Ancient World”, Forbes, 27 April 2017, https://www.forbes.com/sites/drsarahbond/2017/04/27/whitewashing-ancient-statues-whiteness-racism-and-color-in-the-ancient-world/#72a5c33175ad; and “Why We Need to Start Seeing the Classical World in Color”, Hyperallergic, 7 June 2017, https://hyperallergic.com/383776/why-we-need-to-start-seeing-the-classical-world-in-color/. ↩︎

Bibliography

Anon. “Spicula”. Speculum 40 (May 1898): 26–27.

Bell, Charles. Engravings of the Arteries; Illustrating the Second Volume of the Anatomy of the Human Body, and Serving as an Introduction to the Surgery of the Arteries, 3rd edn. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown, Paternoster-Row; and T. Cadell and W. Davies, Strand, 1811.

Bell, Charles. Illustrations of the Great Operations of Surgery, Trepan, Hernia, Amputation, Aneurism, and Lithotomy. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown, 1821.

Berkowitz, Michael, and Ruti Ungar, eds. Fighting Back? Jewish and Black Boxers in Britain. London: University College London, 2007.

Bindman, David. Ape to Apollo: Aesthetics and the Idea of Race in the 18th Century. London: Reaktion Books, 2002.

Boddy, Kasia. Boxing: A Cultural History. London: Reaktion Books, 2008.

Bond, Sarah E. “Whitewashing Ancient Statues: Whiteness, Racism and Color in the Ancient World”. Forbes, 27 April 2017. https://www.forbes.com/sites/drsarahbond/2017/04/27/whitewashing-ancient-statues-whiteness-racism-and-color-in-the-ancient-world/#72a5c33175ad.

Bond, Sarah E. “Why We Need to Start Seeing the Classical World in Color”. Hyperallergic , 7 June 2017. https://hyperallergic.com/383776/why-we-need-to-start-seeing-the-classical-world-in-color/.

Brinkmann, Vinzenz, Renée Dreyfus, and Ulrike Koch-Brinkmann, eds. Gods in Color: Polychromy in the Ancient World. San Francisco, CA: Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco, Legion of Honour, 2017.

Brown, Elspeth H. “Racialising the Virile Body: Eadweard Muybridge’s Locomotion Studies 1883–1887”. Gender and History 17, no. 3 (2005): 627–656.

Callen, Anthea. “The Body and Difference: Anatomy Training at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris in the Later Nineteenth Century”. Art History 20, no. 10 (1997): 23–60.

Callen, Anthea. Looking at Men: Art, Anatomy and the Modern Male Body. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2018.

Chill, Adam. “The Performance and Marketing of Minority Identity in Late Georgian Boxing”. In Fighting Back? Jewish and Black Boxers in Britain. Edited by Michael Berkowitz and Ruti Ungar. London: University College London, 2007.

Darby, Robert. “Syphilis 1855 and HIV-AIDS 2007: Historical Reflections on the Tendency to Blame Human Anatomy for the Action of Micro-Organisms”. Global Public Health 10, nos. 5–6 (2015): 573–588. DOI:10.1080/17441692.2014.957231.

Darby, Robert. “‘Where Doctors Differ’: The Debate on Circumcision as a Protection Against Syphilis, 1855–1914”. Journal of the Society for the Social History of Medicine 16, no. 1 (2003): 57–78.

Darwin, Charles. The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex. 2nd edn. London: John Murray, 1883.

Day, Thomas. The Dying Negro: A Poem, 3rd edn. London: printed for W. Flexney, opposite Gray’s-Inn-Gate, Holborn; J. Wilkie, in St. Paul’s Church-Yard; and J. Robson, in New Bond Street, 1775.

DiAngelo, Robin. White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Race. Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 2018.

DuBois, W.E.B. Darkwater. New York: Harcourt, Brace, and Co., 1920.

Dyer, Richard. White. London: Routledge, 1997.

Ellis, George V., and G.H. Ford. Illustrations of Dissections. London: James Walton, 1867.

Endelman, Todd M. The Jews of Georgian England, 1714–1830: Tradition and Change in a Liberal Society. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 1999.

Fend, Mechthild. Fleshing Out Surfaces: Skin in French Art and Medicine 1650–1850. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2017.

Fordyce, George, David Pitcairn, and Charles Combe, comps. Catalogue of Anatomical Preparations in the Hunterian Museum. Glasgow: University of Glasgow, 1840.

Freeland, E. Harding. “Circumcision as a Preventative of Syphilis and Other Disorders”. The Lancet 156, no. 4035 (1900): 1869–1871.

Gamer, Meredith. “The Smugglerius, Re-Viewed”. Sculpture Journal 28 (2019): 331–344.

Gilman, Sander L. “Cutting it Short: James Boon’s Circumcision”. Anthropological Quarterly 90, no. 4 (2017): 1027–1052.

Hammerschlag, Keren R. “Drawing Racial Comparisons in Nineteenth-Century British and American Anatomical Atlases”. In Victorian Science and Imagery: Representation and Knowledge in Nineteenth-Century Visual Culture. Edited by Nancy Rose Marshall. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, forthcoming July 2021.

Honour, Hugh. The Image of the Black in Western Art, Vol. IV: From the American Revolution to World War I, Part I: Black Models and White Myths. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1989.

hooks, bell. Black Looks: Race and Representation. Boston, MA: South End Press, 1992.

Hutchinson, Jonathan. “On the Influence of Circumcision in Preventing Syphilis”. Medical Times and Gazette 11, no. 283 (1855): 542–543.

Huxley, Thomas H. “On the Geographical Distribution of the Chief Modifications of Mankind”. Journal of the Ethnological Society of London 2, no. 4 (1870): 404–412.

Jones. Ross L. “Cadavers and the Social Dimension of Dissection.” In The Body Divided: Human Beings and Human “Material” in Modern Medical History. Edited by Sarah Ferber and Sally Wilde, 29–52. Farnham: Ashgate, 2011.

Jones. Ross L. Humanity’s Mirror: 150 Years of Anatomy in Melbourne. Melbourne: Haddington Press, 2007.

Jordanova, Ludmilla J. “Gender, Generation and Science: William Hunter’s Obstetrical Atlas”. In William Hunter and the Eighteenth-Century Medical World. Edited by William F. Bynum and Roy Porter, 385–412. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985.

Jordanova, Ludmilla J. Sexual Visions: Images of Gender in Science and Medicine. London: Harvester Wheatsheaf, 1989.

Jordanova, Ludmilla J., and Deanna Petherbridge. The Quick and the Dead. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1997.

Kemp, Martin, and Marina Wallace. Spectacular Bodies: The Art and Science of the Human Body from Leonardo to Now. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2000.

Knox, Robert. The Races of Men: A Fragment. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Blanchard, 1850.

Litvack, Leon. “Continental Art and the ‘Cockneyfied Corkonian’: German and French Influences on Daniel Maclise”. In Daniel Maclise 1806–1870: Romancing the Past. Edited by Peter Murray, 198–213. Cork: Crawford Art Gallery and Gandon Editions, 2008.

MacDonald, Helen. Human Remains: Dissection and Its Histories. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2005.

MacDonald, Helen. Possessing the Dead: The Artful Science of Anatomy Illustrated. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 2010.

McInnis, Maurie. D. Slaves Waiting for Sale: Abolitionist Art and the American Slave Trade. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2011.

Maclise, Joseph. Comparative Osteology being Morphological Studies to Demonstrate the Archetype Skeleton of Vertebrated Animals. London: Taylor and Walton, 1847.

Maclise, Joseph. On Dislocations and Fractures. London: John Churchill, 1859.

Maclise, Joseph. Surgical Anatomy, 1st edn. London: John Churchill, 1851. Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/b32723684/page/n3/mode/2up.

Maclise, Joseph. Surgical Anatomy. Philadelphia, PA: Blanchard and Lea, 1851. Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/b32723659/page/n4/mode/2up.

Maclise, Joseph. Surgical Anatomy. London: John Churchill, 1856.

Maclise, Joseph. Surgical Anatomy. Philadelphia, PA: Blanchard and Lea, 1859. Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/b32723672/page/n4/mode/2up.

Maclise, Joseph. The Plates of Maclise’s Surgical Anatomy with the Descriptions from the English edn: with an Additional Plate from Bougery: Maclise. Boston, MA: John P. Jewett and Co., 1857, plates only. Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/b32723647/page/n4/mode/2up.

Marsh, Jan. “The Black Presence in British Art 1800–1900: Introduction and Overview”. In Black Victorians: Black People in British Art, 1800–1900. Edited by Jan Marsh, 12–22. Aldershot: Lund Humphries, 2005.