Mr Joseph Maclise and the Epistemology of the Anatomical Closet

Mr Joseph Maclise and the Epistemology of the Anatomical Closet

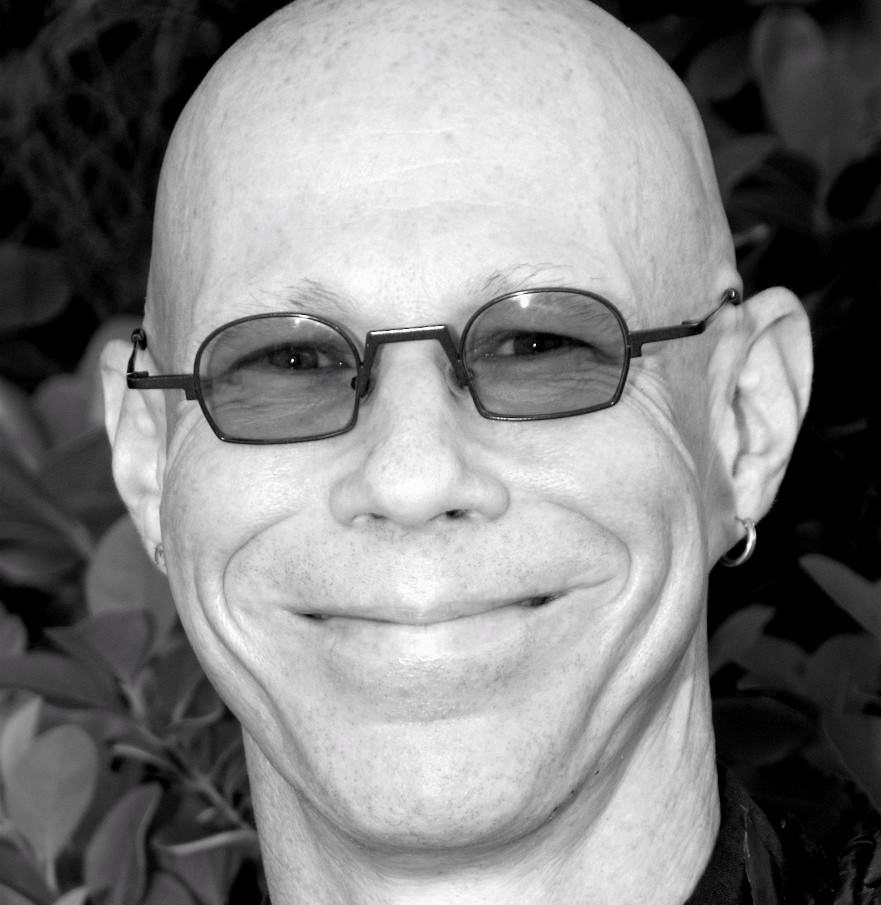

By Michael Sappol

Abstract

This article takes up the case of Joseph Maclise (1815–1891), a talented and truculent surgeon, anatomist, and medical illustrator of mid-nineteenth-century Britain. Maclise left behind a corpus of brilliant, idiosyncratic anatomical images, and opinionated commentaries, but almost no evidence of his social interactions or affective relations. Homoerotic desire was heavily policed in Maclise’s time. Given the conditions under which the archive was created (or suppressed, or lost, or shamed into reticence), we can never know with certainty what he intended or felt, or what his readers received—but we do have a rich evidentiary base of visual materials. Using narrative history, close readings of images and texts, detailed comparisons with other illustrated anatomies, and open-ended theoretical and methodological approaches (a mash-up of queer theory, Foucault, gaze theory, genre analysis, and contextualization)—an argument is joined: a book can be a closet and a queer space. Maclise’s drawings, ostensibly designed to contribute to the improvement of medical knowledge, theory, and practice, show good-looking young men and cadaveric bodies in various states of dissection. Penises, testicles, anuses, faces, sensuous hands on skin are crisply rendered in illusionistic perspective, with a highly cultivated aestheticism—often without any relevance to the anatomical topic discussed—and little attention is paid to the female body. In historical context, and from our twenty-first-century vantage point, the hypothesis of homoerotic investment leads to productive interpretations. This article poses more questions than answers but comes to rest with this: it is plausible and meaningful to take Maclise’s anatomical illustrations, and the figures depicted therein, as queer objects of queer desire.

The Mystery of Mr Joseph Maclise

The closet: a condition of smothered homosexuality, suppressed desire, longing. A claustrophobic space of isolation, where shameful feelings are incarcerated, expression is secret, or entirely thwarted.1 But the closet can also be a hothouse where desire comes to grow, intensify, and know itself. Until a crisis of self-emancipation: a coming out (as the story is commonly told). Or in more repressive circumstances, say mid-nineteenth-century London, maybe just a coded disclosure that only closeted persons of similar interests will detect and decrypt. Or maybe not even that, just an ongoing interior discussion among the closeted person’s divided selves, entirely private, self-contained.

1Even though the metaphor of “the closet” came into common usage in the middle decades of the twentieth century, the condition of being closeted undoubtedly came long before. In this article, I suggest that in Victorian Britain a certain kind of anatomical illustration might be a place where “the love that dare not speak its name” could show itself, even flaunt itself, in an image in the pages of a book or a folio of prints, all the while remaining undercover. A closet of sorts. In this construction, repression is an intensifier which creates and proliferates the very categories it aims to forbid and extinguish (as Michel Foucault famously argued).2 The closet is not a grave where desire comes to die, but a private and provisionally safe queer space—shielded from public spectatorship and policing—where desire is imaginatively free to take shape, can be self-nurtured and articulated, in reverie as in linguistic and visual and gestural code, and in meaning-laden silence, arousal, and “the telling secret”.3

2But when same-sex desire and its objects are unavowed, and evidence is limited, how should we proceed? What can we know when “closeted-ness itself is a performance initiated … by the speech act of a silence”?4 This is the paradox so cogently addressed in Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s Epistemology of the Closet (1990). Sedgwick acknowledges that there can be no epistemological certainty when it comes to a system of meaning that is covered over. But, she argues, if we only limit ourselves to what is epistemologically secure, we miss everything important.

4Joseph Maclise (1815–1891), a brilliant anatomist and gifted artist of mid-nineteenth-century Britain, and also a loquacious and opinionated writer, was entirely reticent about his affective life and erotic attachments. Maclise never married, had no children (that we know of), left behind no diaries, letters, self-portraits—almost no puzzle pieces—only a thin trail of circumstantial crumbs, mostly left behind by his brother, the famous painter and illustrator Daniel Maclise. But Joseph Maclise did leave us a large number of extraordinary anatomical illustrations, which he insisted enter “the understanding straight-forward in a direct passage” as words cannot. “A picture of form”, he asserted, “is a proposition which solves itself.” In those axioms, Maclise was arguing that his true-to-nature renderings of anatomical dissections and subjects irrefutably instantiated the forms and principles of “transcendental anatomy”.5 But, leaving those specific claims aside, and following Sedgwick’s lead, let’s entertain the possibility that Maclise’s renderings, in some queer and occluded fashion—maybe not even fully apparent to Maclise himself—instantiated other principles. Maybe they were a space in which he unveiled himself, sent out flares of homoerotic desire.

5To our twenty-first-century eyes, Maclise’s “pictures of form” are open-ended, offer many propositions from which many possible solutions can be derived. But they do have tendencies: a deeply felt mimetic sensuality, an overabundant pleasure in bodies, line, and texture, an argumentative assertion of principles and positions, and a queer intensity. And so we’ll take the case of Maclise and his images in three contrapuntal registers: the historical method (chronological, biographical, contextual, narrative); close reading and analysis of images (and some texts); and the comparative method (comparing Maclise’s pictures to those of his predecessors and contemporaries). (Which is only fitting: Maclise was a passionate exponent of the comparative method.)

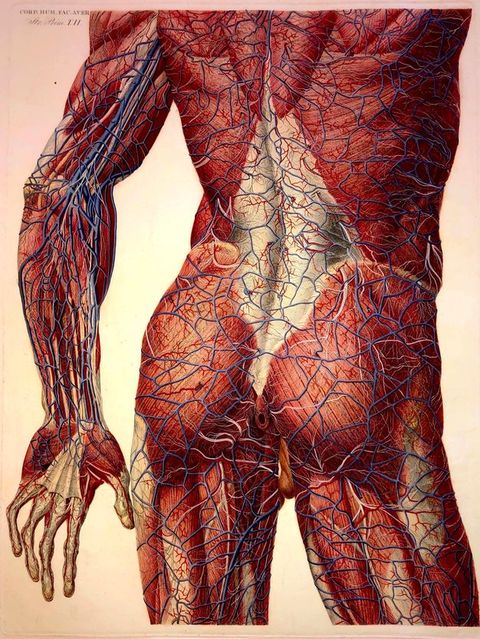

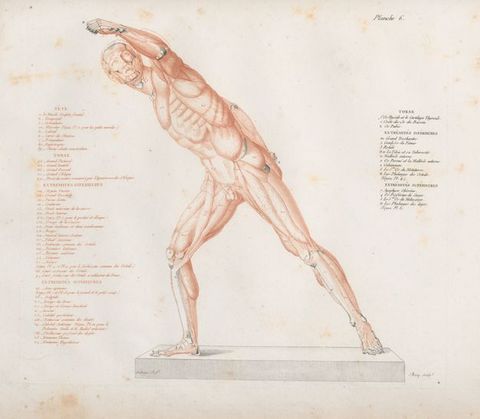

Over its long history, anatomical illustration has often been a multivalent conveyor of meanings, open to idiosyncratic clowning, horror shows, allegorical play-acting, memento mori, and erotic expression. And often enough—given the centrality of the figure of Man as the emblem of the universal anatomical human—homoerotic expression. So, to set the scene before Maclise enters stage left, let’s entertain the possibility that this spectacular life-size colored engraving from Paolo Mascagni’s Anatomia universa (or Grande anatomia del corpo umano) (1823–1830) performs something that exceeds the instrumental purpose of demonstrating the anatomy of the back of the arm, lower back, buttocks, and rectum (fig. 1).6 Maybe it was meant to be a flaunting cruising figure, a flirt. If so, was the affective power of that flirtation perversely intensified by the fact that anatomists had, over the previous century, mostly rejected the flirty poses and winking gestures of early modern anatomy as untrue to nature and unbefitting serious scientific study? Was its gaudy coloration a rejection of anatomical sobriety, a displaced expression of anatomical dandyism?7

6

The erotics of anatomical illustration went mostly unmentioned in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century medical discourse. (Anatomists William Hunter and John Bell never explicitly discussed flirtation or sensuality in the essays that prefaced their anatomical atlases, but signaled their disdain for all forms of representational play.)8 And, again, that’s a problem for historians: should we bracket erotic valences as a kind of unknowable semiological dark matter—disqualify ourselves on the grounds that we will be tempted to fill up the epistemological void with our own aisthesis and erotics? Or take interpretive liberties? In this essay, following Sedgwick, I will take liberties, because efforts to police and punish open expressions of same-sex desire nearly always produce queer results: representations disguised, encoded, contorted (even unconscious, given that we aren’t transparent to ourselves). If so, scholars can and should undertake open-ended investigation and reasonably speculate, as long as evidentiary limits are respected. This won’t be an open-and-shut case. Our remit here is to ask questions and to imaginatively reconstruct Joseph Maclise and his image-work through close and contextual reading and looking—the historian’s gaze—and credit the possibility of coded expressions and erotic valences. The anatomical closet.

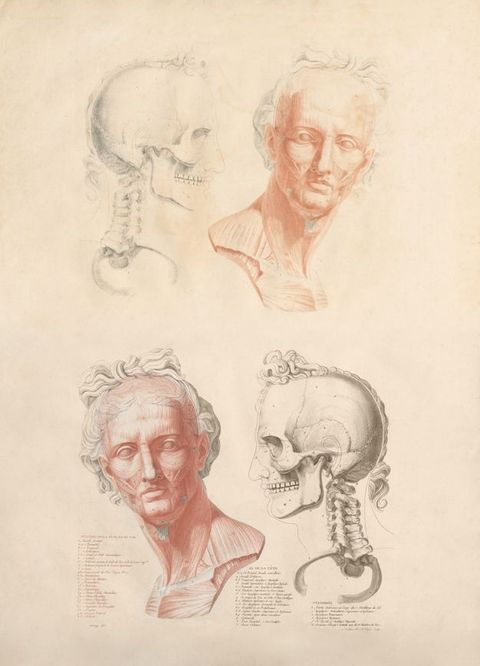

8Sharing Medical Eyes and Hands: Jacob and Bourgery’s Traité complet

The middle and upper social and intellectual registers of surgery grew markedly in the latter half of the eighteenth century and first half of the nineteenth century, as did the number of trained surgeons. And so did the production of objects and experiences for sharing among those medical men and their cultured fellow travelers—experiences that were aesthetic as well as scientific and practical. This fellowship took place between men in overlapping but stratified circles of professional knowledge and experience, a kind of bonhomie nurtured by shared connoisseurship and collecting interests. Between Men also happens to be the title of another seminal work by Sedgwick, an extended riff on masculine sociality and its troubled ramifications.9 Sedgwick argues that the sex-segregated social arrangements of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Europe and America fostered the development of intense “homosocial” attachments between men. Those attachments were forged and renewed by the sharing and exchange of, and competition over, books, opinions, paintings, meals, drinks, money (gambling!), and so on—and by the shared connoisseurship of beautiful, artfully made, and collectable things, as much as the shared viewing and owning of those things. Anatomical objects occupied a place of privilege among the collectables: beautifully wrought sculptures, paintings, drawings, and prints of beautiful nude and semi-nude men and women; and authoritative, expensive, artfully illustrated and printed, often large-sized, books dealing with the subject of anatomy, atlases which stood atop the hierarchy of medical publication.10

9So it makes sense that a reviewer of the first two installments of Richard Quain’s lithographic “imperial” folio, Anatomy of the Arteries of the Human Body (inaugurated in 1840, completed in 1844), praises the “delineations of Mr. Maclise”, for evincing “artistical talent of the very highest order”, and makes a connoisseurial assessment: Maclise’s plates “will bear comparison with any of those splendid specimens of anatomical drawing, so abundant on the continent, but heretofore so very rare in our own country …”.11 There was, it seems, something Continental, and “so very rare”, about Maclise’s images. This perhaps wasn’t merely a euphemism for sexy (or effeminate, as some writers of the time would have it), but points to a hard-to-describe quality which a connoisseurial eye would discern as aesthetically distinct from, and pleasurably superior to, the fine British illustrated anatomies extant at the time, works by William Hunter, John and Charles Bell, Astley Cooper, John Lizars, and others. The reviewer doesn’t go beyond this suggestive remark but could have been thinking of plates then issuing in installments of the Traité complet de l’anatomie de l’homme (1832–1854) of surgeon-anatomist Jean-Baptiste-Marc Bourgery (1797–1849) and his gifted collaborator, “professor-draughtsman-anatomist” Nicolas Henri Jacob (1781–1871).12

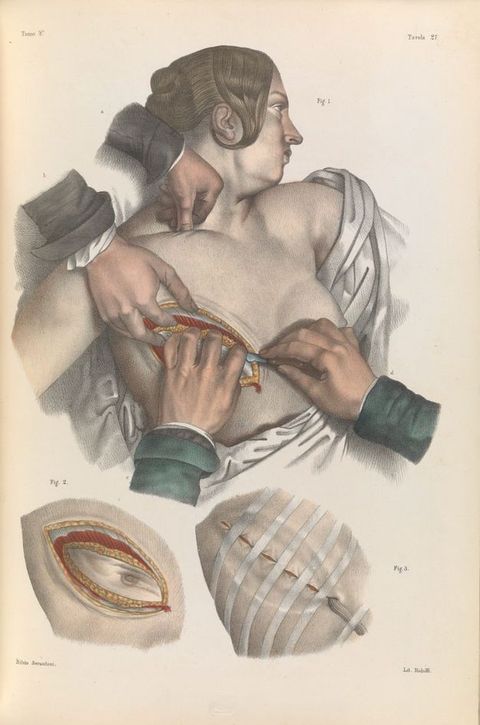

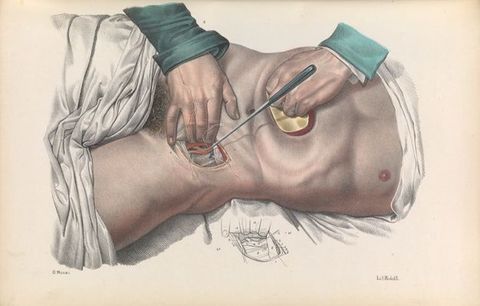

11Take, for example, this lithographic demonstration of an operation for the surgical removal of a breast cancer, which shows disembodied masculine hands working on the body of a supine and beautiful woman (fig. 2). The scene is a brilliant composition brilliantly executed. Jacob was a skilled practitioner of Jacques-Louis David’s “corporal aestheticism” (Jacob studied under David)—but was just as much under the influence of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, who famously used color and shading to show body volume, mass, texture, and silky, creamy, perfect skin.13 So, a sumptuous, perfectly polished illustration of a desirable young woman with a fashionable hairdo, undergoing a terrible operation (before anesthesia comes into common usage) without any expression of terror. Like many other images in the Traité complet, it is offered as a how-to guide to a difficult surgical operation, a horror, and also a visual delight, an incitement.

13

Two sets of almost identical hands share the surgical work, mimetically evoking both the haptic experience of surgery and the touch-sensation of masculine hands on the naked flesh of a female beauty and her anatomical subsurface.14 A shared set of touchings, which in turn are offered for sharing among those with privileged access to the plate in a fine medical library, or who can afford to subscribe to the installments (expensive), or purchase volumes as they were completed (very expensive), or purchase (from 1854 onward) the full set of eight volumes (obscenely expensive).15 The Traité complet outdid all of its competitors: its illustrations were more comprehensive, brightly colored, precise, demonstrative, pedagogical, horrific, provocative, numerous, illusionistically perspectival, more beautiful. Extravagant. And, in the aggregate: oddly playful, theatrical, voyeuristic. We gaze upon the patient, who, within the depiction, can’t return the gaze. The surgeon receives representation synecdochically, as a disembodied hand and multiples thereof. Apart from that, he only exists inferentially, outside the picture plane. And in the Traité complet, that asymmetrical relation, between undepicted gazer and depicted object of the gaze, inscribes a hierarchical relation—between spirit (the sight-unseen surgeon and reader/viewer, the subject) and matter (the pictured patient and cadaver, the object).

14A kind of transgression is thereby initiated. Elizabeth Stephens, in her essay “Touching Bodies: Tact/ility in 19th-Century Medical Photographs and Models”, argues that the “erotics of touch” is “a relation of mutuality and reciprocity between two bodies … a point of contact in which to touch is always also simultaneously to be touched”: “[T]ouch is foundational to the relationship between subjects … the point of intersection between ethics and erotics”.16 If so, the touching depicted in Jacob’s illustration violates that mutuality and reciprocity. The scene pairs the opportunity to see (what modesty shouldn’t consent to) with an opportunity to touch (what virtue shouldn’t consent to). All imaginary: this is just representation of touch, not touch itself. But from those double representational transgressions, committed upon an object of desire, an erotic frisson is constituted. Stephens speaks of “the sexualization inherent in the construction of medical knowledge itself”.17 But, as we shall see, some constructions are more sexualized than others.

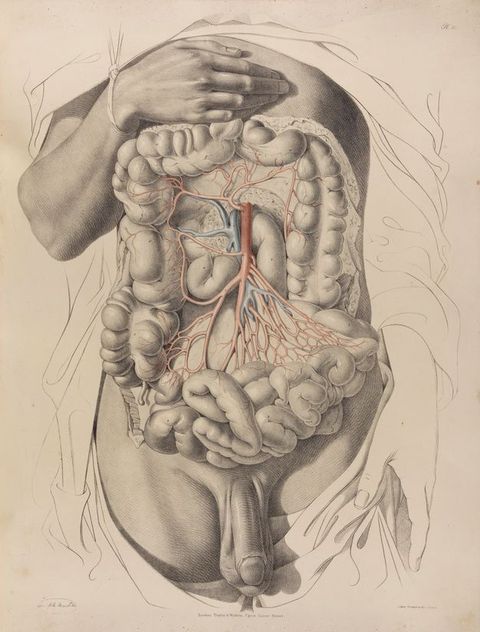

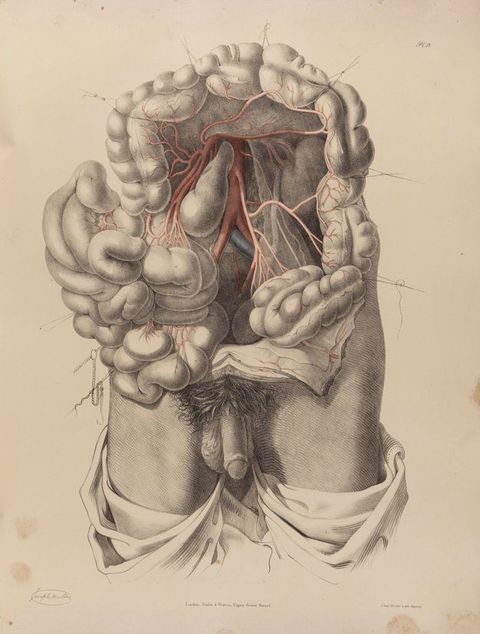

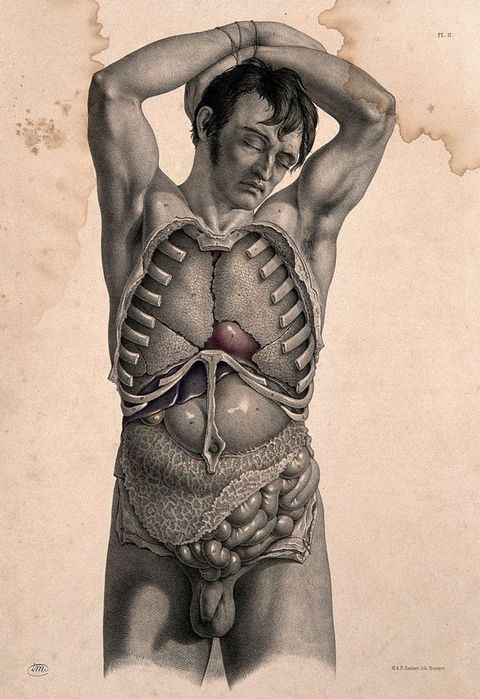

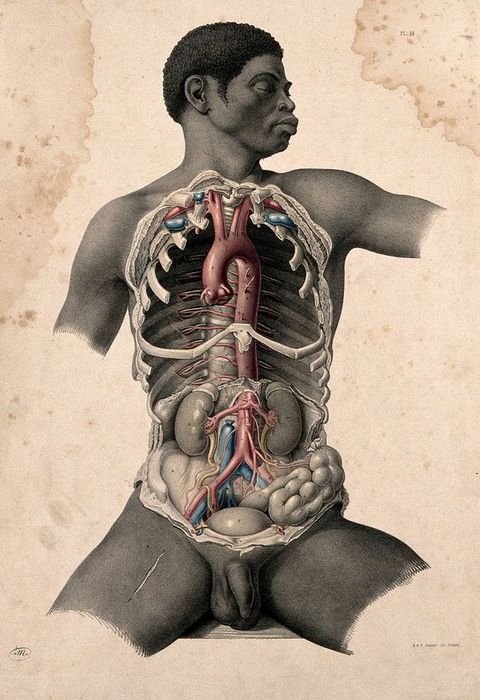

16The Parisian medical establishment never rewarded Bourgery with any high position, but his atlas became a standard reference work—a top-shelf medical publication that every good medical library had to have—and helped to inspire a growing corpus of lithographic illustrations that used high artistry and brilliant color to convey the sensual experience, the feel, of surgery (and pathology, obstetrics, dermatology, histology, and anatomical dissection). Much of the focus in the Traité complet was on dissected bodies and body parts. But the showstoppers were the atlas’s nude and semi-nude figures, some female, but most male (fig. 3). Beautiful faces and bodies—objects of desire—subjected to horrific or just peculiar scenes of surgical-anatomical intervention, in a work that was itself an object of desire, arrayed in libraries alongside other works of bibliophilic desire. (And not far away: collections of desired specimens, models, instruments, objets d’art.)

Jacob and Bourgery were acclaimed for the sheer plenitude of materials covered, especially their detailed representation of hands on and in bodies, step-by-step depictions of surgical operations—a genre of illustration that went way beyond anything non-medical artists might attempt in depicting gory scenes of the martyrdom of the saints and historical atrocities, or sexy scenes of nude heroes and woodland nymphs from Greco-Roman antiquity. Their atlas was intended for a specialized readership of medical men who were trained and licensed to look upon difficult subjects, to exercise a privileged gaze. And, by virtue of class and gender, socialized to exercise that privileged gaze upon erotic subjects. Wealthy bibliophilic physicians and surgeons built large libraries of books and, of course, also socialized with non-medical collectors—collectorship and connoisseurship were famously fraternal (but also exclusive). One can easily imagine those non-medical men of privilege, hungry for sensation and novelty, acquiring the atlas of Jacob and Bourgery, eager to peek behind the professional curtain, or merely browsing through volumes in the libraries of medical friends. (The same class of gentlemen used their pull to observe surgeries and dissections, and tour the Parisian morgue.)18

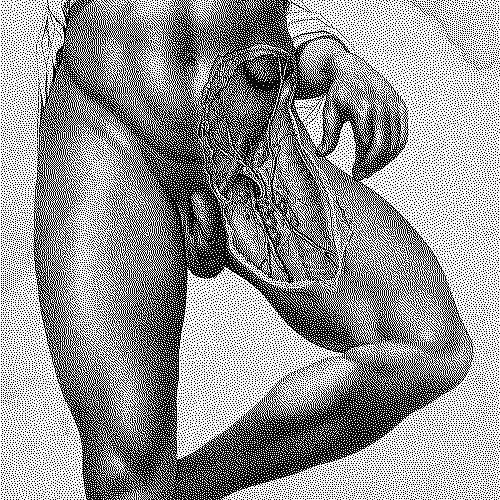

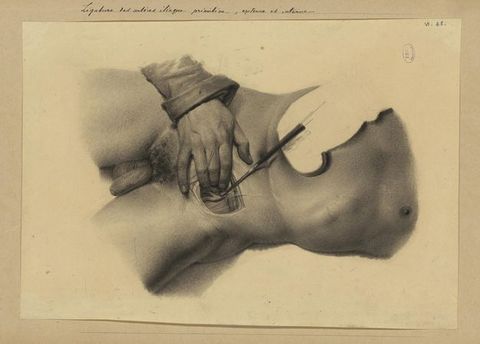

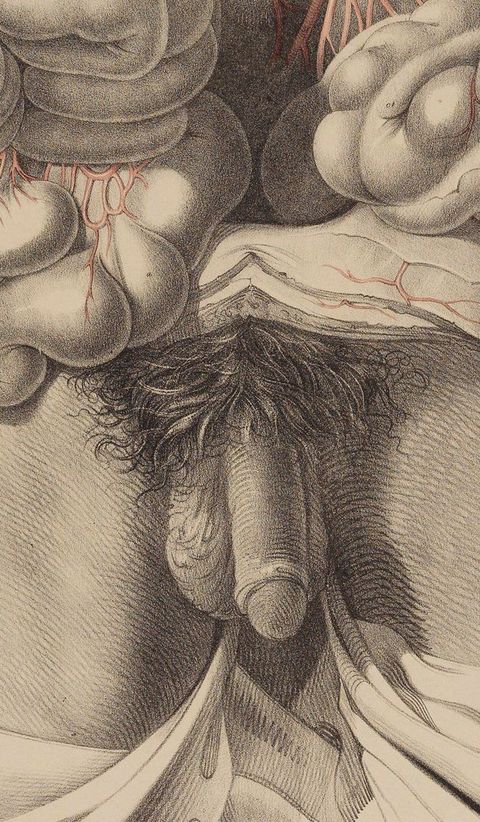

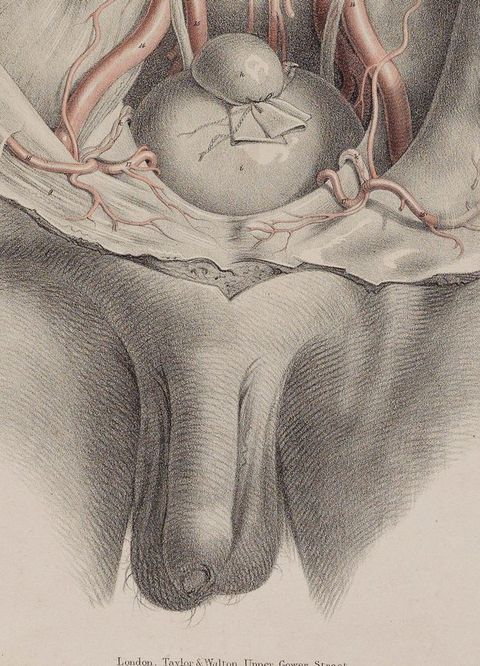

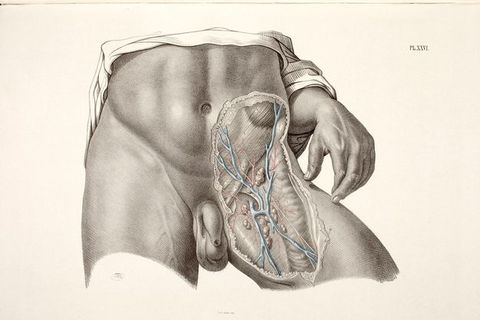

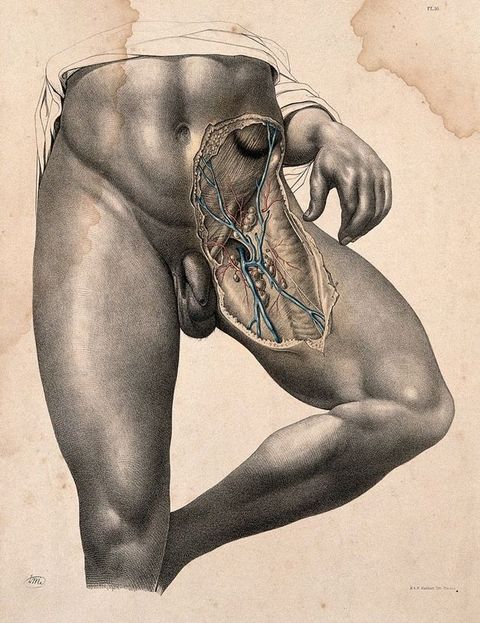

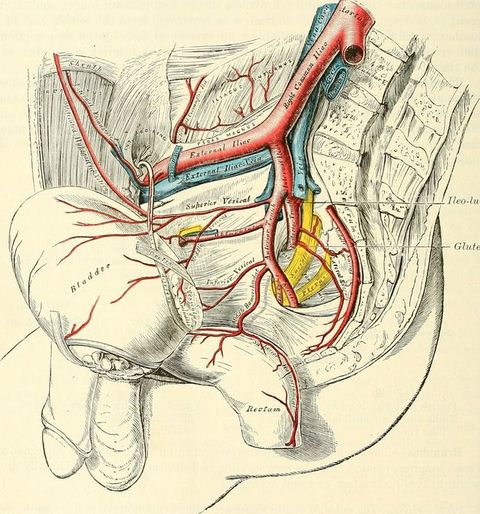

18But even Jacob had to negotiate boundaries. Compare his preparatory drawing of the ligature of the iliac arteries with the finished 1841 print. The preparatory drawing shows a hand inside a surgical cut made in the body of a well-proportioned, almost classical, masculine torso (fig. 4). The image fades out above the right nipple (leaving space for an undrawn left hand that will hold the surgeon’s probe). Below the cut, Jacob artfully renders the penis, with an almost independently sensate pinky not far away (slightly apart from the other fingers), right at the border where pubic hair leaves off. The lithographic version covers up: it wraps both ends of the anatomical subject in cloth, a framing device that protects the modesty of the reader (and anonymous patient/cadaver?) and hides the penis. Yet, upon closer inspection, the penis remains discernable beneath the artfully rendered folds of cloth. Is Jacob dancing on the line, enjoying himself, teasing his audience?

Maybe Bourgery or publisher C.A. Delaunay asked the artist to make the change, but Jacob probably didn’t need prompting. The standard practice in mid-nineteenth-century illustrated medical publication was to omit or minimize things that were irrelevant or distracting, especially if that thing was a penis. For a formally trained artist like Jacob, the preparatory drawing was a stage in a process, a place to show figures in the nude, fully undressed, to get a better sense of the underlying structure of the bodies, but then overlay clothes or drapery in the finished version. Embedded in this method was a hierarchy of structure—skeleton > écorché > nude > dressed—that was a foundational part of the curriculum of drawing pedagogy.19 And the nude stage of that hierarchy (often connected to the study of live nude models) provided the opportunity for a certain kind of private erotic pleasuring, followed by a more modest covered public presentation.20

19What makes all of this germane to our discussion is that Joseph Maclise—who followed in the footsteps of Bourgery and Jacob, and situated himself in the tradition of perfectionist, sensual, volumetric figure drawing—departed from the conventions of medical illustration and, in his finished publications, didn’t cover up his irrelevant penises …

A Bit of Puppetry: Maclise’s Superior Mesenteric Artery

If anatomical dissection and representation can activate a certain kind of queerness (and vice versa), then queer theory offers us a useful descriptive vocabulary for the tactics and settings of anatomical performance. Such as “the closet”, “queer space”, “camp”, “flagging”, “passing”, “flaunting”, “clubbing”, "panic’ … Another favored term is “the gaze”, a keyword in visual culture studies, feminist theory, and the writings of Michel Foucault. In those settings, the gaze—especially “the medical gaze”—is mostly figured as an oppressive, coercive thing. The person or body part gazed upon is “constituted” as an object by the gaze (and its technologies), and so fixed, and robbed of agency. (Foucault says “cadaverized”.)21 But not so fast. The gaze is dynamic, complex, multidirectional. It turns back on itself, has recursive properties: the object being gazed upon, even a cadaver or a picture of a cadaver, seems to look back, talk back, stages a return of sorts. “The object stares back”, proclaims art historian James Elkins (echoing Lacan): the initiator of the gaze is divided by the gazing act, invests the object of the gaze with agency, or a simulation thereof, and in so doing makes a divided self, divided subjectivity.22

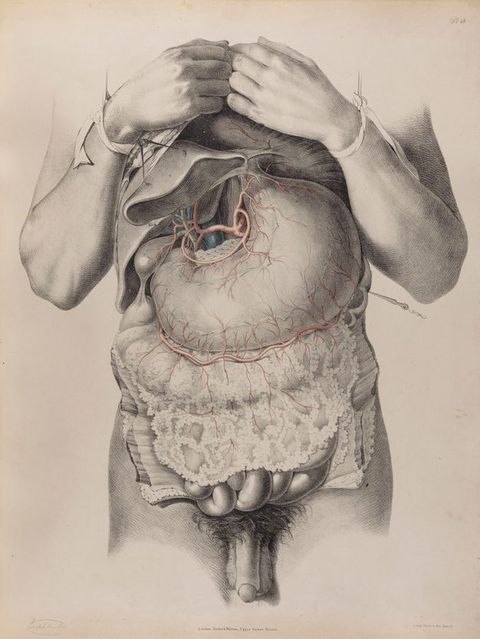

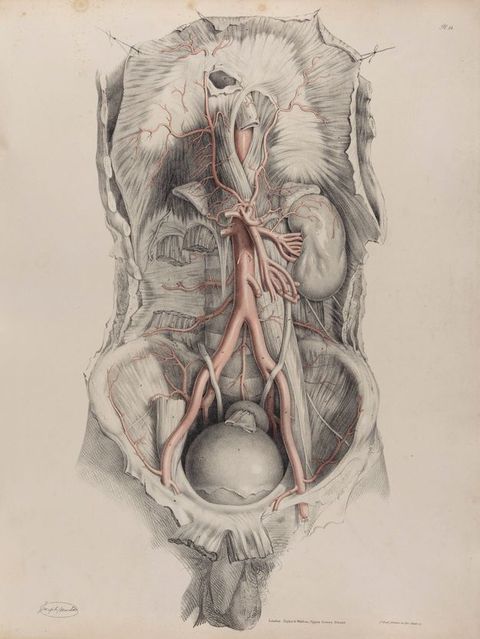

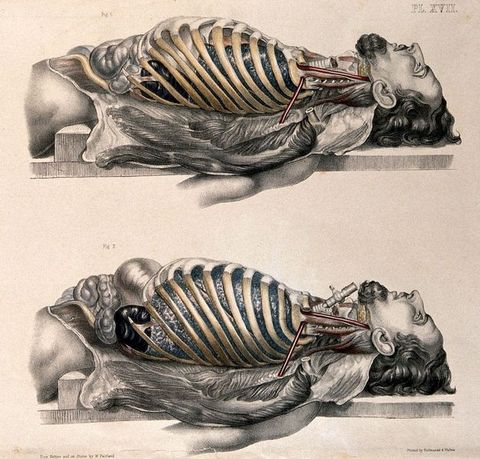

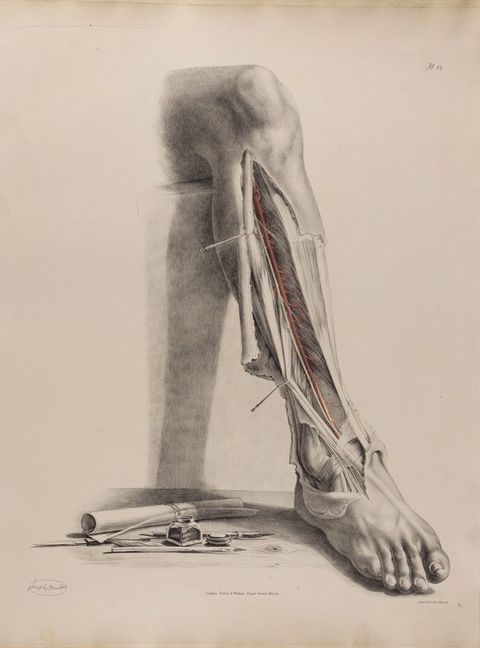

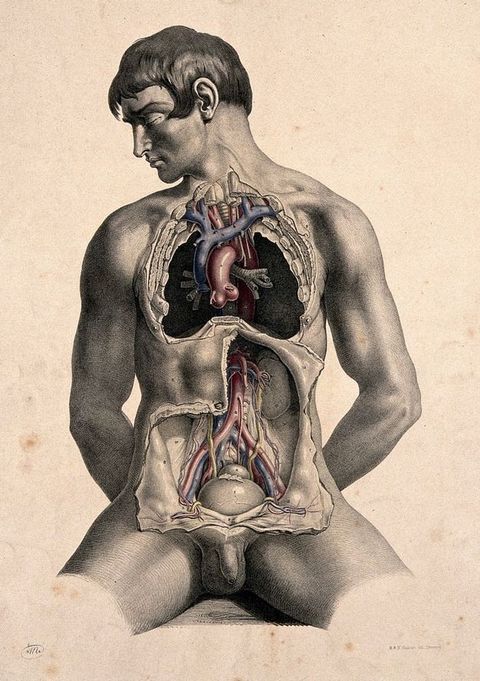

21Consider, then, this plate, from Richard Quain’s The Anatomy of the Arteries of the Human Body (1844), featuring “drawings from nature and on stone”—Joseph Maclise’s first major publication as medical illustrator (fig. 5).23 Upright, as if alive, the cadaveric figure demonstrates the anatomy of the superior mesenteric artery—and gives Maclise the opportunity to indulge in a bit of puppetry. A cord keeps the right hand suspended at the breast, so that the fingers appear to be pointing to, touching, the heart. It is a signing sensate hand; the gesture is “heartfelt”. Somehow, that hand—the cadaver in its entirety—is the artist’s proxy. But it also appears to have a will of its own, seems to signal to Maclise and, looking over Maclise’s shoulder, to the reader.

23

The wealth of extraneous detail adds to the verisimilitude of the scene, attests to Maclise’s commitment to truth telling, his skill at staging a persuasive view, what Roland Barthes famously termed “the reality effect”.24 There is the neatly arranged rupture of the cut … Those subtle shadows and contours … The undissected skin surfaces which border the rococo intestines as they nearly spill over the finely rendered penis and testicles … Maclise could have covered over the genitals with a sheet or left them out of the picture. Like the dangling hand, the penis is entirely irrelevant to the subject under demonstration. Yet, Maclise still contrives to show it hanging front and center: a provocation, when we consider that it goes against the convention in medical publication, to cover up or crop out the male genitals (unless the illustration is demonstrating a uro-genital topic). And even more provocative if we consider the convention in classical and neoclassical art (the art which saturates Maclise’s approach to illustration), where penises were expected to be discreetly small (if not obscured by a fig leaf or some other device).

24Maclise’s aphorism speaks of the “picture of form”, but what of the form of this picture?25 The mesenteric artery is framed by intestines, which are framed by the anatomist’s cut, which is framed by the skin of the cadaver, which is framed by the non finito outline drawing of the sheet with the left hand completing the circle, and then framed by the negative space around the whole. Frames around frames. Almost a rosette. The plate demonstrates a bravura dissection no doubt, flaunts the anatomist’s erudition and skill with the scalpel.26 But does so with a special aesthetic dimension: Maclise the artist flaunts his bravura draughtsmanship, command of line and shadow and space, compositional gifts—and command of lithography (this is “drawing on stone”). Flaunting in multiples. Is Maclise “queering” the picture, flaunting something of himself? (His signature is bold, expressive.) Is this the sort of thing that queer theory provokes us to think about? Can “importing queer notions into the world of critical theory”, as Caroline Evans and Lorraine Gamman advocate, help us to comprehend, reconstruct, and take pleasure in “perverse but enjoyable relations of looking” in nineteenth-century anatomy?27

25Maclise was the artist. Richard Quain (1800–1887) was the folio’s author. A wealthy “professor of descriptive anatomy” at the University of London (a prestigious post) and a Fellow of both the Royal Society and the Royal College of Surgeons, Quain was born in County Cork, Ireland, into one of the lower echelons of the upper crust (his father was a “retired gentleman living upon a small estate”). Well-connected medically via Jones Quain, his half-brother (who preceded him as professor of medicine at the University of London), Quain became one of Britain’s most eminent surgeons, a status ratified by his ascension to the office of President of the Royal College of Surgeons and appointment as Surgeon Extraordinary to Queen Victoria.28 Said to be “strictly conservative”, and an advocate for education in the liberal arts for the public and medical profession (as he contended in his Hunterian Oration of 1869), Quain argued that a surgeon should be a man of culture and discrimination, a gentleman and not just a crude mechanic of the body.29

28His “friend and former pupil” Joseph Maclise came from humbler stock.30 Also born in County Cork and fifteen years Quain’s junior, Maclise was the son of a Presbyterian Scottish regimental soldier turned tanner and shoemaker. After study in both medical anatomy and “the Anatomy of Painting” under John Woodroffe in County Cork, and further medical study at the University of London and in Paris, he attracted notice as a radical adherent of “transformism” in debates over evolutionary theory (before Darwin entered the fray).31 And established himself as a working surgeon and medical illustrator of uncommon ability. Early on, Quain was his mentor and protector, a bond likely forged from their County Cork connection. After the accolades accorded The Anatomy of the Arteries of the Human Body, Maclise was raised up from Member to Fellow at the Royal College of Surgeons. From there, he went on to produce his own atlases, most notably Surgical Anatomy (1st ed.: London: John Churchill, 1851; 2nd ed.: London: John Churchill, 1856; also in large format, though smaller than Quain’s atlas) (fig. 6). While Surgical Anatomy was a critical and commercial success, and perhaps earned him some income (we have no records of book sales, finances, or arrangements with publishers), it failed to win him a hospital or university appointment. His career ambitions, and likely his social aspirations, were thwarted.

30Queer Scenes: Maclise and the Bells Compared

Plate 60 of The Anatomy of the Arteries of the Human Body is a tour de force, a cascade of visual rhymes in deep-focus, high-definition, illusionistic perspective (fig. 7). The layered folds of fabric, pulled back like a curtain, rhyme with the deep and disruptive layered dissection. The curvature of the anatomical cut, and folded intestines, rhyme with the penis (in the shadows) and testicles (curving the other way). The cadaver’s left hand seems to be crawling toward the pen (doubling as a scalpel and overlaying what may be a scalpel) as the right hand emerges from the folds, crawling toward the anatomical opening, feeling its own torso. Does this dissected body “stare” back?32 Not with eyes (it has none). With hands? There is no haptic equivalent for staring back, yet Maclise’s cadaver seems to feel back … touch … grope …

32

Maclise keeps his hands to himself. Unlike Bourgery and Jacob’s Traité complet, surgical/anatomical hands never appear in the Quain and Maclise atlas or in Maclise’s later atlases. The disembodied hands on display in Jacob’s illustrations are sensual, but also pedagogical: they model surgical technique (solo and team), show where the surgeon’s hand or fingers should go, how to hold the surgical instrument and make the incision, how to open, hold, and close the wound, how to sew things back up. And they have an indexical function (in the service of pedagogy and showmanship): Jacob uses them to direct the reader’s attention.33 But the hands in Maclise’s Plate 60 (and Plate 51) do nothing of the sort. They are irrelevant, unpedagogical, unindexical. If anything, they distract from surgical and anatomical business (and go unmentioned in captions and commentaries).

33Distraction, of course, is a key technique of stage magic and mesmerism. Hypnotists rely on our habit of following the indexical hand to induce a trance that allows them to take over the consciousness of a hypnotized subject. Are Maclise’s cadaveric hands doing something similar? Is he entrancing us? Or indulging in a bit of auto-suggestion? If the hands in Plate 60 aren’t a proxy for the surgical hand, then for what? The desirous self? The scene of Plate 60 is oddly private, personal. Recruited to empathically feel the feeling hands of an anatomical subject, the reader is ushered into a space where Maclise’s flashing desire can, momentarily, become palpable.

This is not just gimmickry, but stylized realism, accomplished visual rhetoric, trained, and redolent of the academy and the atelier. Three or four registers of beauty converge: the beauty of the subject’s hands (and genitals); the beauty of the arrangement of the scene; the beauty of the dissection itself (which also has aesthetic dimensions, as any anatomist could tell you); and the beauty of the drawing and lithography. Together, those aesthetic attributes have a rhetorical valence. They do something more than persuade the viewer that the scene is true. The sharp focus and crisp details—the penis, testicles, and scraggly pubic hair that lie outside the margins of the dissected region, the folds of cloth—show off Maclise’s anatomical and artistic powers, which are not entirely separate matters. The beauty, precision, and detail of the artist’s rendering are distinguishing marks of anatomical excellence, as they had been for the grand productions of Maclise’s eminent anatomical forerunners: Govard Bidloo, Albrecht von Haller, Antonio Scarpa, William Hunter, Friedrich Tiedemann (all cited in Quain’s preface to the folio), and the Traité complet of Bourgery and Jacob (uncited, but arguably a lurking contextual presence). Remember also the super-size format: The Anatomy of the Arteries of the Human Body is an “imperial” folio, life-size, 1:1 scale, printed on expensive paper—of a measure and quality that bespeaks the aspiration to create a masterpiece.34

34All of which redounded to the credit of author Richard Quain (who occupied the professorial chair once held by the venerated Charles Bell), credit shared to some degree by his protégé Maclise. The Anatomy of the Arteries of the Human Body performed their command of anatomy and surgery, their slashing skill with the dissecting knife, their privileged access to prodigious quantities of the best quality cadaveric “material” (recently dead, relatively undamaged bodies, with good musculature and proportions, and nice facial features—not always readily available). And let’s not overlook the large amount of money Quain had the resources to invest, in the preparation and printing of his deluxe atlas (including payment to Maclise?). By such measures, Quain affirmed his authorial filiation with predecessor luminaries, his place in the grand anatomical tradition: the canon.

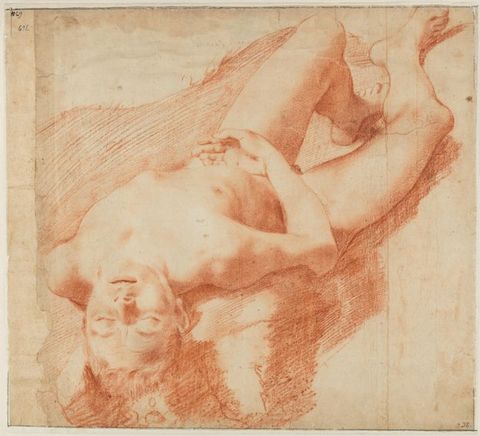

But Maclise also performed authority—mastery—in another register. The composition of the scene and its constituent parts and devices, the play of light and shadow, the big gestures and small flourishes, attest to the caressing brilliance and authority of Maclise’s drawing hand and eye—and mark his filiation with the grand tradition of figure drawing invented in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the genre of figure study so prized by connoisseurs (fig. 8). Art! Which, given the centrality of the male nude in figure drawing, was full of homoerotic potentials. Maclise aimed to satisfy the highest scientific standards of medical publication and the highest aesthetic, connoisseurial standards so prized by formally trained fine artists and collectors. If Maclise displayed his ability to perform beautiful dissections, and skillfully render beautiful men, beautiful bodies, beautiful body parts, he also displayed his gift for making beautiful pictures.

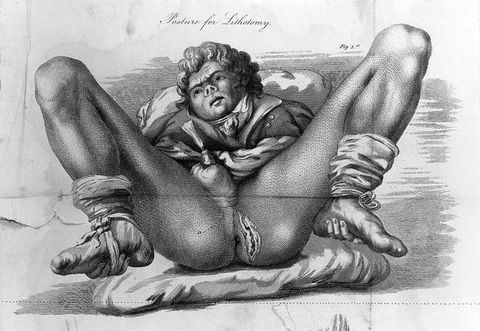

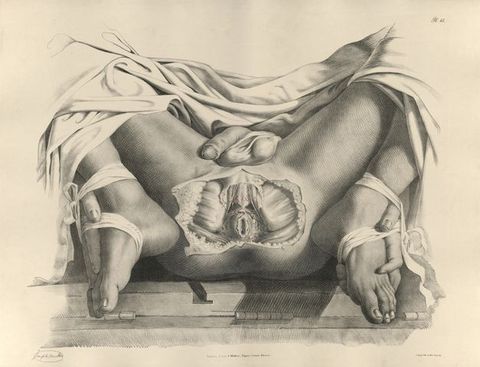

To get a fuller sense of Maclise’s aesthetic maximalism, consider Plate 62, depicting the operation for lithotomy (fig. 9). It’s all a bit much. Ostentatious virtuosity. Provocative, fulsome representation of skin surfaces. An approach, which Maclise justifies, in later writings, with a surgical rationale: “The surface of the living body is […] a map explanatory of the relative position of the organs beneath …” The depiction of skin surfaces—even those that aren’t adjacent to his dissections—is “an aid”, which furnishes “the memory with as clear an account of the structures” as if they were “perfectly translucent”.35

35

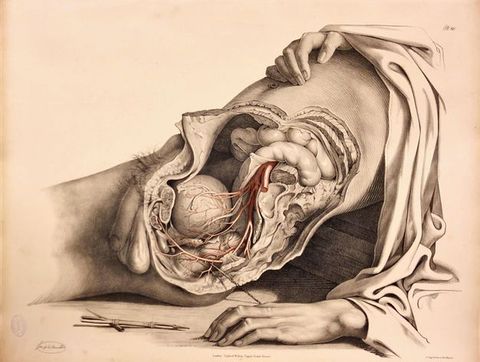

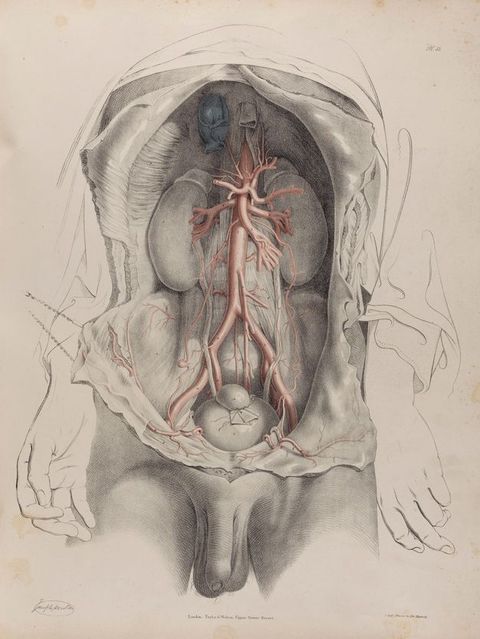

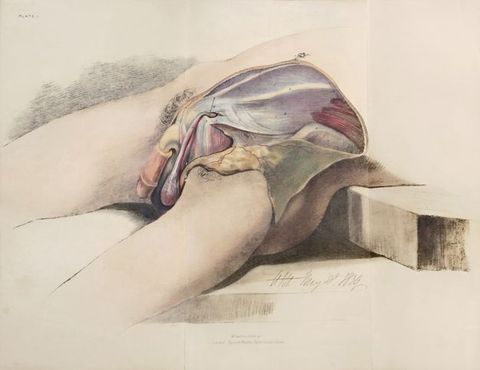

That principle furnishes Maclise with something else: an opportunity for erotic frissonerie. Plate 62 is a queer anatomical bedroom scene, featuring a supine masculine body, beneath the sheets, with exposed genitalia and open rectum (the imperial folio format encourages Maclise to make horizontal compositions). It is an arresting image, an arresting pose, simultaneously intimate and theatrical. The cadaver, a handsome young man, is placed in a female subject position—a pose that frequently appears in obstetrical illustration.36 A corpse obviously cannot resist, but the body in death becomes noncompliant (“dead weight”, rigor mortis). And so to arrange the corpse in a position favorable to both dissection and the artist’s view, the cadaver’s arms are tied to his ankles. To our eyes, the tying-up suggests coercion, but also may signal consent, as in consensual sexual bondage: the hand that holds the ankle seems to cooperate. At the same time, the figure itself appears to be asleep or lying in wait. If the man is dead, why tie the hands? Is that necessary?

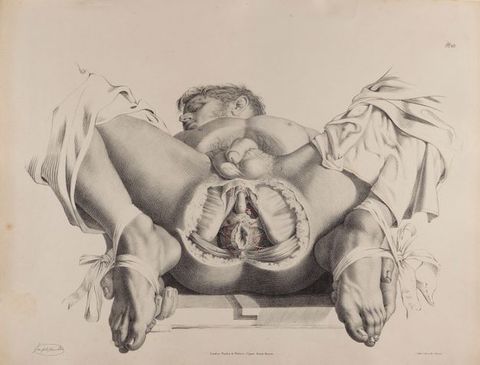

36But the logic of the pose becomes apparent when you consider the illustration’s iconographical origins and purpose—to show the anatomical structures and positioning that a surgeon would need to know to “cut for stone”. Maclise’s plate is perhaps inspired by, or in dialogue with, the “posture for lithotomy” illustration in John Bell’s Principles of Surgery (1801–1808), an awkward engraving of a living patient subjected to the cutting for stone operation (fig. 10).37 Lithotomy was a difficult procedure: only the unremitting agony of a blockage could make someone so desperate as to consent to the risky and painful operation. The surgeon had to keep the patient’s legs parted and fixed to suppress flinching, shuddering, and other involuntary movements. Hence, the tying of hands and feet. Maclise’s plates rehearse the operation on a cadaver; Bell’s on an (unhappy, reluctant) patient whose penis is tied off and bagged, as it would have to be during surgery. Bell’s illustration, probably drawn by his brother Charles, makes no attempt at graceful rendering. The visual argument is straightforward, if a bit cartoonish. Undignified, slightly off in proportions and perspective, not one of Charles’s or John’s best. Certainly not beautiful—a useful image, nothing more.

37

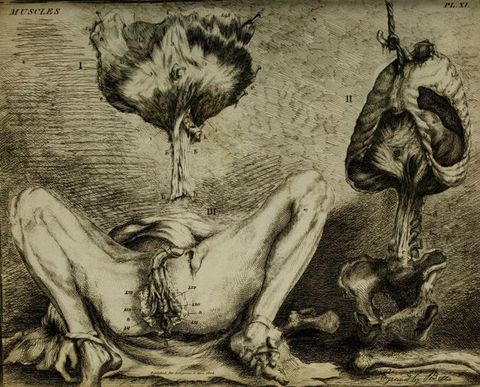

That fits with John Bell’s persona as a gruff enemy of medical gentility and prettification. In his 1794 Engravings of the Bones, Muscles and Joints, Bell makes ostentatiously ugly etchings that show severed heads, mangled bodies abjectly plopped onto the dissecting table or hanging carelessly from a hook. (The etching technique encourages quick, sketchy lines.) Like Maclise, John Bell is both the anatomist and the artist—I think a brilliant artist—but Bell never pretends to make works of Art. (We may, of course, regard his 1794 Engravings of the Bones, Muscles and Joints, as just that.) If the “posture for lithotomy” in Principles of Surgery is klutzy, slightly ridiculous, his earlier darkly gothic dissection-table etchings are powerful, disturbing, deadly serious. And among them is a deliberately harsh depiction of a very dead, and entirely unanimated, cadaver trussed up and placed in the posture for lithotomy, underneath an unpretty diaphragm nailed to the wall, next to a dissected torso hanging from a rope—anatomical objects for an entirely different lesson (fig. 11).38 In the preface to his Engravings of the Bones, Muscles, and Joints, John Bell deplores the fact that most anatomists have to depend on professional artists whose “striving for elegance of form” introduces inaccuracies, falsifies the image.39

38

Yet, Maclise’s lithotomy images, contravening Bell, combine great “elegance of form” with meticulous rendering, verisimilitude. The plates of The Anatomy of the Arteries of the Human Body counterpoint anatomical rupture, violation, and destruction with sensuality and beauty, and make it look real, which is to say true. But they also perform a bit of magic: make the cadavers seem subtly alive.

The contrast between Bell’s 1794 engraving and the work of Maclise is even more pronounced in Maclise’s Plate 61, the first of the pair dealing with the anatomy of the perineum and rectum (fig. 12). It doesn’t show the cadaver’s face, but instead frames the genitals and dissected area with a proscenium of drapery. From the carefully rendered folds of cloth—echoed by the folds of the testicular sac—to the fine grain of the wood table, it is abundantly evident that Maclise aspires to make Art—even in the depiction of this unlikely subject. Using lithography to produce subtle gradations of crayon and pencil, Maclise orchestrates the contrast between surface textures, cloth, skin, and the anatomical rupture—the flesh neatly scalloped away to reveal the “superficial dissection”. (Other plates show “deep structures”.)40 The feeling, again, is both intimate and grand—the artist’s immersive private view (Maclise’s view) is also a printed monument. Maclise aims for a heedless transcendence, entirely sequestered from the growing debate over whether beauty was antagonistic to the goal of accuracy in science (an issue he never broached in his commentaries).41

40

A “technique of echoing bodily forms in drapery and upholstery”, art historian Mechthild Fend notes, was “often used in 18th-century erotic art, in paintings by Fragonard” and in “Boucher’s 1745 Odalisque where the forms of the reclining nude […] are multiplied in the plush fabrics”.42 In both his dissection and his arrangement of reclining nudes (in Plates 61 and 62), Maclise plays with the difference between surface and underlying layers. Hardness, in the hardness of bone and muscle and the wooden table. Softness, in the smooth textures of skin and cloth. The approach is sculptural and tactile.43 Maclise exquisitely renders skin contours and surfaces, especially around the area of the anatomical opening, which softens (feminizes?) the undressed masculine subject. His pencil is a caress, almost an invitation to touch (what cannot be touched). (And what of his scalpel?) It’s as though “the alluring surface … ‘solicits touch … as it prohibits it’”. 44 If, as Fend suggests, anatomy is an unveiling and the skin a veil, “the symbolic removal of which results in the revelation of an ‘inner truth’ or essence”, Maclise reverses that. His anatomy is an opportunity to dress the body in sumptuous, silky, hairless skin and display its utter nakedness.45 Dissection gives the anatomist (and reader) access to what is usually hidden beneath clothes. Maclise sets up a queer scenario. The deliberate stripping of skin could be taken to be an echo of the stripping of clothing that precedes sexual intercourse. And the revelation of “inner truth”, anatomical unveiling, stands in for the revelation of hidden desire, an unmasking. Or a masked revelation.

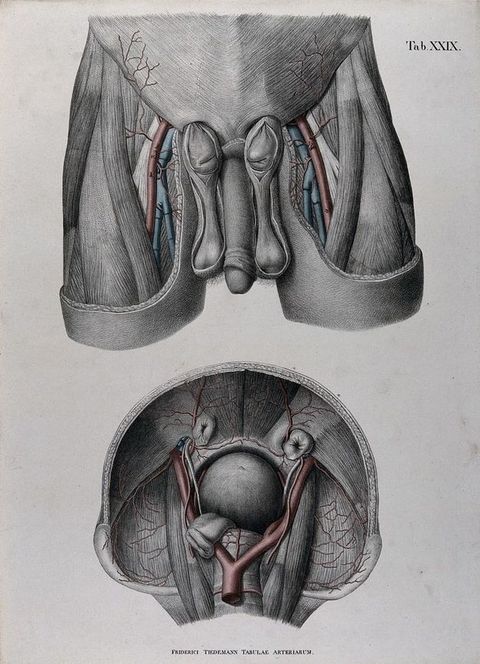

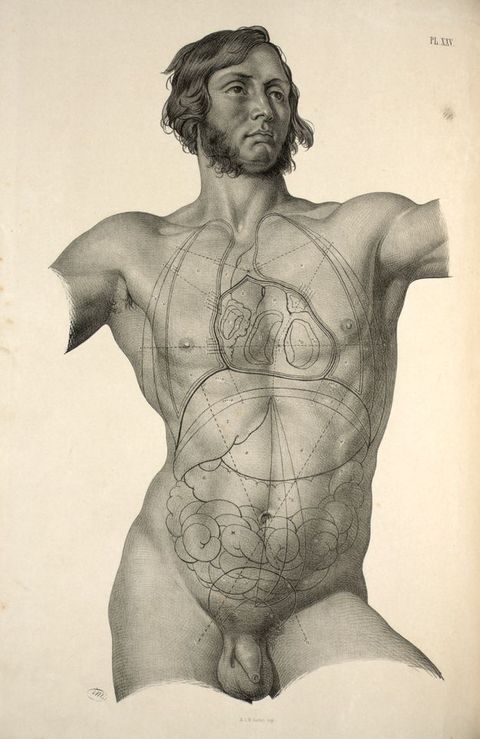

42Irrelevant Penises (a Gallery)

Maclise drew a fair number of hands and faces in his atlases, but uniquely specialized in a different area: the male nether regions. Is there another nineteenth-century artist, inside or outside of medical illustration, who so lovingly and persuasively renders the scrotum, testicles, and penis? Even within medical illustration, Maclise’s penchant for drawing male genitalia (foreskin retracted and unretracted) is exceptional. And not only in Plates 61 and 62: his atlases are full of figure studies of masculine nude subjects, with penises fully exposed, in a fashion not permitted to academicians, and only exercised in a constrained way by other medical illustrators. An uncovered penis appears 27 times in The Anatomy of the Arteries of the Human Body, often in scenes where it is irrelevant to the anatomical region demonstrated. Maclise and Quain focus almost entirely on male bodies and body parts (figs. 13–20). Only one dissected female body appears among the folio’s 87 plates: Plate 59, which resembles Plate 60 in every particular, with one signal difference: Maclise covers the undissected female genital region with cloth. Was that because representational conventions concerning female genital modesty were more powerful than those that regulated the male? Or because Maclise took special pleasure in representing the male genitals? Or all of the above?

That special interest didn’t wane in Maclise’s subsequent work. The 1856 edition of Surgical Anatomy shows the penis 43 times in 52 plates, sometimes at the margins, but often front and center. That undoubtedly reflects not only Maclise’s interest as a practicing surgeon in regions where hernias, stones, and fistulas often manifest, but also perhaps a special interest in young men, masculine bodies, and male genitalia. Women, of course, also get hernias, stones, and fistulas. But Maclise only shows female genitals twice in Surgical Anatomy and only briefly discusses operations on women.

Other contemporary British anatomies—the large format chromolithographic atlases of George Viner Ellis (a former student of Quain) (fig. 21) and Francis Sibson (fig. 22), and the smaller chromolithographic manuals of Thomas Morton (another former student of Quain) (fig. 23)—demonstrate aesthetic virtues, but lack the intimacy, grace, perspectival depth, and erotic valences of Maclise’s atlases. Sibson and Viner Ellis avoid the groin (while confining themselves to mostly male cadavers). Morton, who specializes in the surgery of hernias, stones, and fistulas, shows plenty of male groins (and a fair number of female groins), but with little sensuality. There’s nothing comparable to Maclise’s fixation on male genitalia.

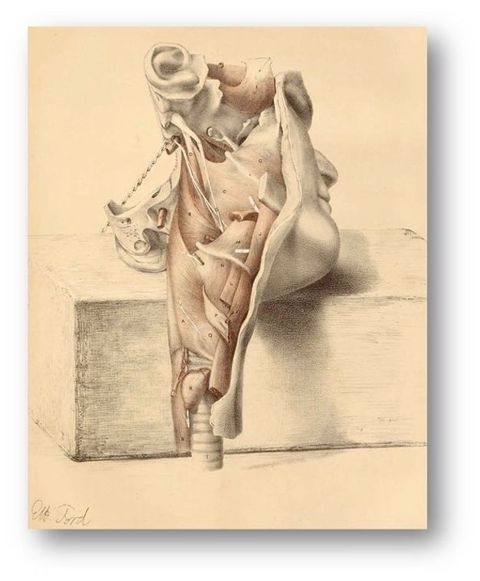

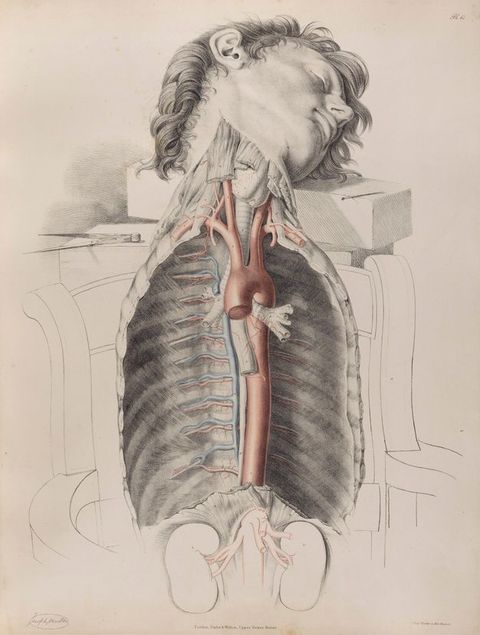

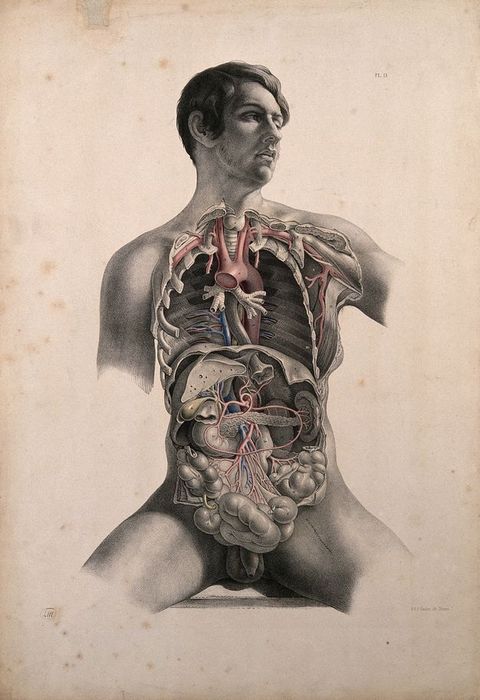

“Transcendental Anatomy” and the Semblance of a Crucifixion

We’ve looked at headless cadavers, with sensate hands and exposed genitals. Now consider Plate 47 of The Anatomy of the Arteries of the Human Body, another figure study and another queer scene: the nearly bodiless head of a handsome young man with flawless skin, flowing hair—but no hands, no arms, no genitalia (fig. 24). Seemingly asleep, his head rests on a horizontal block of wood, artfully lit (slightly from below, the left side). But that beautiful face is irrelevant (unnecessary, like the penises) to the demonstration of “the thoracic or descending aorta with the intercostal arteries”.46 As in so many of his eye-catching illustrations, Maclise’s hunger to depict masculine beauty (or just Beauty) converges with his eagerness to flaunt his artistic gifts and aesthetic sensibility.

46

There is, of course, also anatomy to attend to: an inverted V-cut incision at the neck leads down to the heavily dissected aortic cavity. Maclise leaves off at the bottom with a non finito sketch of the kidneys. What’s left of the body, after the radical paring away of parts, is framed by a non finito wooden armchair, the staves of the chair echoing the ribs of the thoracic cage and their architectural/structural function. Maclise is doubling and redoubling, embellishing his image with a kind of platonic ghost, in step with the dualism that was then coursing through British and Continental fiction, philosophy, and fine art, with its elevation of capital “B” Beauty and refined abstraction and getting-it-right detail. (Think of the dualism of real and ideal beauty in the art criticism of William Hazlitt and John Ruskin.) That open-ended, ramifying aesthetic, in turn, neatly connects Maclise’s love of beauty in realistic depiction to French naturalist Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire’s preachings on the organic “unity of plan”.47

47Quain did all the talking in the text of The Anatomy of the Arteries of the Human, but Maclise in his own atlases wrote at length on transcendental anatomy, “unity”, “symmetry”, “homology”, and against laboratory science and new empirical research. According to historian Philip Rehbock, the central idea behind transcendental anatomy was that “a single Ideal Plan or Type … lay behind the great multiplicity of visible structures of the animal and plant kingdoms”, a simple symmetrical Plan that “acted as a force for the maintenance of anatomical uniformity, in opposition to the diversity-inducing” or “degenerating … forces of the physical environment”.48 In the prefaces and commentaries to Comparative Osteology (1847), Surgical Anatomy (1851 and 1856), and On Dislocations and Fractures (London: John Churchill, 1859), Maclise dwells on the principle of anatomical and aesthetic unity—and searches for symmetry and other geometrical patterns. He argues that the dissections and skeletal specimens reveal how the organic body instantiates geometrical forms, and has a shadowy mathematical Beauty, which can be discerned by comparing different species, sexes, and stages of development. The comparative method is crucial. For Maclise, “Comparison [is] … the nurse of reason”; “Contrast is our pioneer to truth”.49

48Quain’s commentary for Plate 47 states simply that “[t]he body was in the sitting posture”, probably in a wooden armchair, “while the drawing was being made”.50 But Maclise takes the liberty here (and elsewhere) to play with aesthetic elements and visually encode “transcendental anatomical” principles that Quain might not have fully endorsed, maybe wasn’t even fully cognizant of. One reviewer commented that “Mr. Quain has allowed himself to be completely overshadowed by the artist”.51 You get the feeling that Maclise hijacked the project. While from Maclise’s later account, the two men agreed on “the Law of a ‘unity of organization’” (Quain appears on a list of the scientific men Maclise says he learned it from), Quain’s text abstains from discussion of transcendental anatomy.52 If that disappointed Maclise, maybe he compensated by speaking loudly through the artwork.

50One wonders: how did Quain and Maclise get on? What was the character and trajectory of their relationship? Was it strictly business or a friendship? Neither man was married. (Quain married late, some years after the time of their collaboration, to a viscount’s widow, and had no children. Maclise never did.) We have no sources on Maclise’s character apart from his anatomical publications, but we do on Quain. They mock him as short and fat, an “unamiable colleague”, prone to grudges, “constantly involved in disputes”, and risibly cautious in undertaking surgical operations. Obituaries mention his feud with the charismatic, incautious Robert Liston (also Maclise’s teacher) and with other members of the medical faculty.53 Maclise dedicated Surgical Anatomy to Liston. (Quain’s name only appears in a few passing references.)54 Quain can’t have liked that. Did the two have a falling out? Was Quain jealous, Maclise resentful? From the peevish tone of his writings on matters anatomical, it’s evident that Maclise carried a sizeable chip on his shoulder. It’s not hard to imagine the two men clashing on philosophy, money, deference, or something else.

53In Plate 47, Maclise performs the principle of symmetry by positioning the body in the center of the page, as an axis, framed by the symmetrical ribs and arms of the chair, the kidneys (a symmetrical pair of organs). On the anatomical subject’s right shoulder, he places a compass, a symmetrical instrument used by artists, anatomists, mariners, mathematicians, architects to plot distance and figure symmetry—an emblem of symmetry and aesthetic unity (and, along with the square rule, an emblem of Scottish Rite Freemasonry). (Was Maclise a freemason?) To the left, the compass is balanced by a pin, an implement used in the dissecting room to hold open flaps of cadaveric skin and tissue. In the preface to Surgical Anatomy (1851 and 1856), Maclise asserts that there are two kinds of facts, “ideal and real”, which he takes to be elements of a visual dialogue.55 The placement of tools then could be signaling his double commitment: to the truthful depiction of “real facts” (the pin); and to “ideal facts” (the compass); the anatomized body as actually dissected; larger anatomical principles as thereby revealed.

55At the center of the composition is the young man’s head. Maclise’s pleasure in the portrayal of the cadaver’s face, with all of its homoerotic valences, overlaps his pleasure in rendering the image in his own bravura aesthetic style, showing off. The figure could almost be taken as a preparatory drawing for the passion of Christ. The tilt of the head, the horizontal bar, the vertical aortic tube, combine to echo the form of a crucifixion. One imagines Maclise—living in the shadow of his famous older brother (perhaps a bit jealous) and eager to show artistic abilities that go beyond mere medical illustration.56

56This packing of signals, gestures, allusions, metaphors, details into what-the-eye-sees anatomical representation wasn’t unprecedented—historians of anatomy will be reminded of Gerard de Lairesse’s drawings for Govard Bidloo’s Anatomia humani corporis (1685). However, over 150 years separate Lairesse from Maclise. The plates of The Anatomy of the Arteries of the Human Body and the two London editions of Surgical Anatomy are utterly unlike anything to be found in the atlases of Maclise’s Victorian medical contemporaries and immediate predecessors.

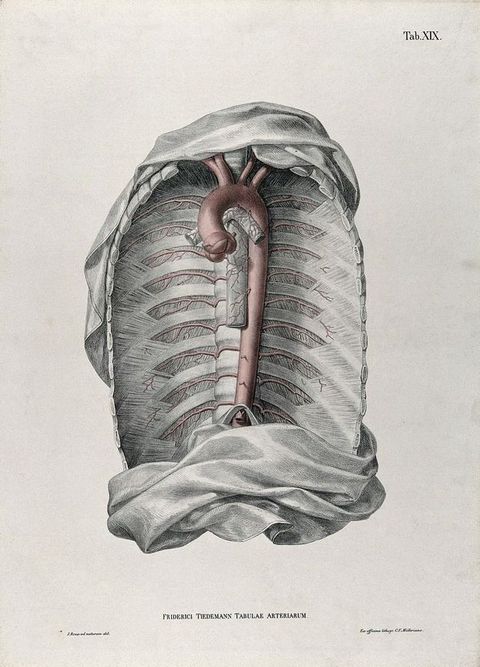

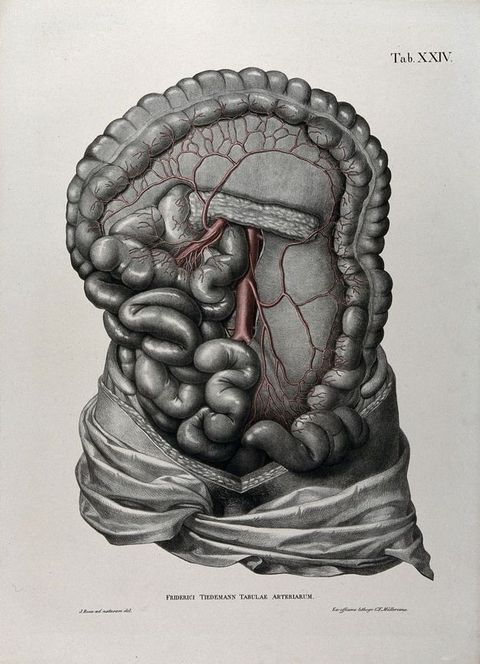

To fully get the nature of that difference, compare The Anatomy of the Arteries of the Human Body with the canonical work Quain aims to supersede, Friedrich Tiedemann’s Tabulae arteriarum corporis humani (1822) (figs. 25–27).57 Tiedemann doesn’t bring readers into the anatomy room. There are no “bedroom scenes”, echolalic crucifixions, or non finito chairs: no scenes or settings whatsoever. (Contrast Tiedemann’s pared-down take on the aorta and intercostal arteries, or his mesenteric artery, with Maclise’s.) Genitals appear only when absolutely necessary, and then only in a dissected state. And there are no undissected faces (except for an introductory plate that greets the reader). Artist Jakob Wilhelm Christian Roux poses figures, mostly torsos or fully detached parts, to stand vertically against the white of the page, as if carved in stone (vaguely echoing the fragmentary torsos of antiquity). Roux’s plates objectify—the anatomist’s gaze on the dissected subject is isolated from competing webs of meaning as if frozen, separated from the scene of dissection and the viewer. Maclise’s plates subjectify—we’re looking at an anatomical scene through Maclise’s eyes, gazing upon an anatomical subject alive with meaning and affective agency.

57

Touching Hands

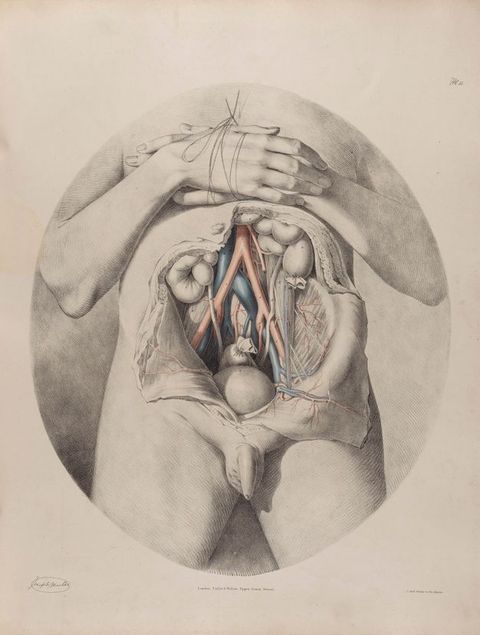

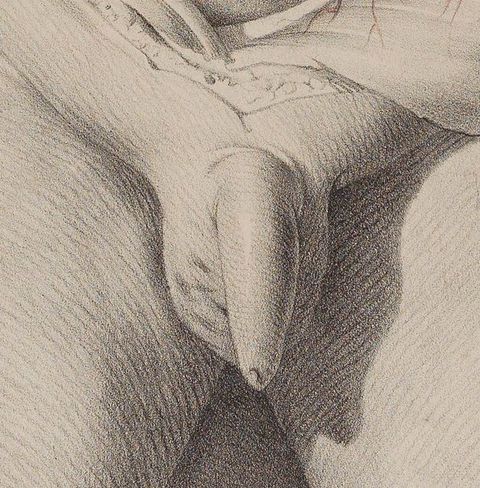

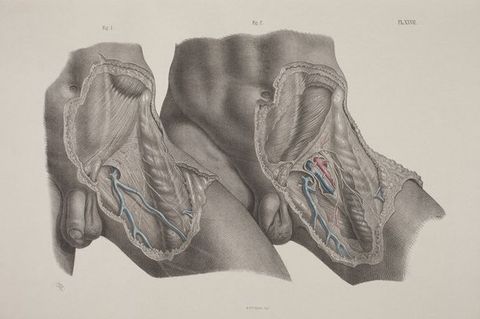

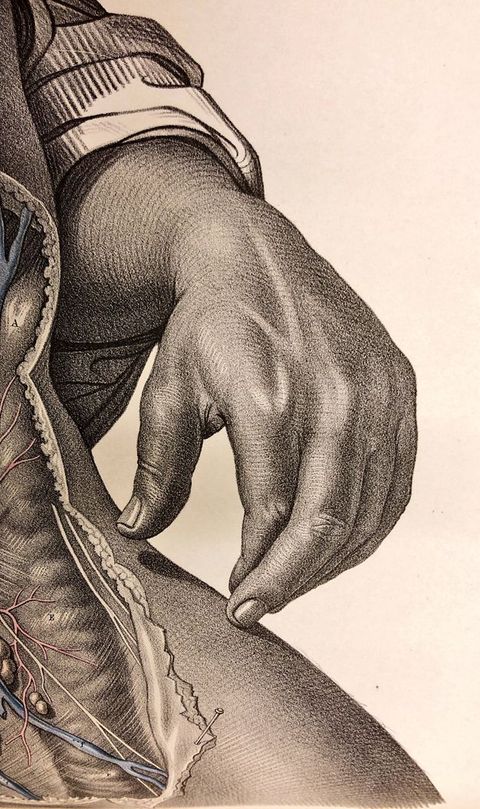

But gaze doesn’t capture the intensity of Maclise’s immersive representational tactics. For that, we need to return to touch, and the representation of hands on skin and skin-to-skin contact. In Plate 26, the sensual hand that gently grazes the thigh (fig. 28) … Is that caress merely another cadaveric proxy for the surgeon-artist’s desirous touch, special feelings for his beautifully proportioned anatomical subject? Or does it also double for the artist’s touche with crayon, pencil, and brush?58 In the 1851 first edition, Maclise shows a bit more (fig. 29). Below the genital region, the subject’s left leg appears to be touching the right leg, just in back of the knee, as if scratching an itch or performing a Scottish country dance or balletic cou-de-pied. See also Plate 27, which initiates a small series of side-by-side dissections (fig. 30). The penis on the right appears to brush the thigh of the figure on the left. It’s rare to see two cadavers touch in anatomical illustration. This kind of touching is rarer still.

58

“Images of skin”, Mechthild Fend comments, “recall a double sensation of touching and being touched.”59 That happens in the positioning of figures, but touching can also be discerned in the textures of the illusionistic rendering: light, shadow, and surfaces created by line drawing. The fine cross-hatching itself records the caressing movement of Maclise’s hand with pencil and pen on paper and then crayon on stone—and mimetically suggests the caressing movement of the hand of Maclise on the bodies of his subjects. Another echo: look closely at Maclise’s Plate 26; the index finger seems to caress the middle finger (fig. 31). A caress within a caress. Exquisite sensation. Reference to the visible brush stroke, as the record of a caress of the surface of the paper or canvas—and, by analogy, a caress of the body of the subject—was a part of the rhetoric of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century art discourse.60 The erotic valence of Maclise’s plates is even more manifest in his representation of skin and touch, than in his drawings of male genitalia. In his commentary on the anatomy of the hand, Maclise invests the hand with agency and powers, praises its “perfect … prehensile and tactile functions”: this “beautiful and valuable member” is “the material symbol of the immaterial spirit”, “has a language of its own”, is “the autograph of mind”.61 Maclise orchestrates a haptic imaginary in words, image, and line. (And if hand is “autograph of mind”, what is on Maclise’s mind when he autographs with his hand?)

59

Critics mostly loved Surgical Anatomy. A reviewer in the Edinburgh Medical & Surgical Journal, commenting on the first three installments, singled out Maclise’s “anatomical knowledge”, “talents as a draughtsman”, “great fidelity and accuracy”, his “very correct and beautiful view” and arrangement of dissected subjects in “the best and most effective positions … before the eye of the beholder” so as to stage them in an “impressive light”.62 But images like Plate 27 push the limits. One reviewer deplored “the crowding of two anatomical figures on the same page”. Was that a displaced expression of discomfort with the erotic implications of such “crowding”? With less space on the page, the smaller format 1851 Philadelphia edition places the figures on separate pages.63 In a larger format, it’s easier to put more than one figure on the same page, and perhaps more pedagogically effective: the proximity of the two figures makes the comparison easier for readers to see. But it also provides an opportunity for Maclise to stage a teasing contact between anatomical bodies.

62The convergence of artist’s touche and anatomist’s touch was an oft-recited topos of art criticism and commentary. According to Fend, the eighteenth-century French portraitist Louis Tocqué, in an essay on painting, described how “the brush penetrates the body like an anatomist’s knife”:

64Rummaging through the inner parts while painting, the artist seems to feel his way with his brush, gaining insight into anatomical knowledge. This sensible brush leads the painter to “discover the muscles neatly”, to organise the amorphous flesh, and enables him to represent the body with ease and precision simultaneously.64

Maclise works the same analogy in reverse. Like a pen, the scalpel makes a composition out of the body, turns the body into a sketch, uses the body to discover lines on paper and composition. And, if we’re not piling on metaphors, carves the body into a sculpture, the sketching of classical and Renaissance sculpture, and anatomical analysis of those sculptures, being key practices in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century art pedagogy (figs. 32 and 33). Intoxicated by the metaphorology and the haptics of his double pleasure as artist and anatomist, in some plates of The Anatomy of the Arteries of the Human Body Maclise includes the tools of the artist’s trade within the image: inkwell, paper, and pen (fig. 34). And in still others, the tools of dissection and surgery: scalpels, knives, hooks, etc. And, in a few images: both types of tools. Scalpel, pencil, chisel, burin, crayon, brush were, as Anthea Callen notes, “symbolically interchangeable” delineators, each instrument deployed by its practitioners with “manual skill, expertise, and dexterity”, to instigate a “revelation” or visualization or scientific understanding.65

65

Maclise’s Men, an Imaginary Confraternity?

Maclise’s focus on the male genitalia and rectum, and the erotics of skin and touch are not the whole story. While he largely refrained from classicizing gestures and conventions, Maclise paid heed to contemporary ideals of masculine beauty in the selection of his cadavers. And seems to have had, at some junctures, a large pool of specimens to choose from. According to Quain, for the plates of The Anatomy of the Arteries of the Human Body, “the bodies … received during a series of years for the study of anatomy into the School of Medicine in University College” amounted to 1,040 or 930. (Quain’s two prefaces differ on the exact number; either way, it’s a lot.)66 For the plates of Surgical Anatomy, Maclise doesn’t total up his cadavers, but states, “in guarantee of their anatomical accuracy”:

6667they have been made by myself, from my own dissections, first planned at the London University College [some of the same specimens used in his collaboration with Quain?] and afterwards realized at the École Pratique and School of Anatomy, adjoining the Hospital La Pitié, Paris, a few years since. Those representing pathological conditions of parts, I have made from natural specimens [Maclise’s emphasis], recent and preserved, which I had the opportunity of examining at the Hospitals and Museums in Paris, London, and elsewhere.67

Paris was famous for its prodigious supplies of cadavers available to dissectors in this period. The bodies came, with little regulatory interference or popular protest, mostly from the large, state-run charity hospitals, where many poor people sought treatment and died. London was less well endowed with large hospitals and deceased patients, but North London Hospital (later, University College Hospital, London), seems to have had numbers adequate to supply Quain’s needs, perhaps supplemented with deceased inmates from other charity hospitals, jails, and poorhouses. After finishing his work with Quain, Maclise never obtained a position that could guarantee him a supply of “anatomical subjects”. Hence, his reliance on drawings made years earlier—“planned” during his time as a student in London and “realized” in Paris.68

68Even there, his choices of cadavers to illustrate were undoubtedly limited: some plates feature older men; others are likely composites (incorporating those “natural specimens”). But, whether true-to-nature or composites, one doesn’t have to search hard to assemble a gallery of handsome young men from Maclise’s drawings. In fact, Maclise himself assembled such a gallery in Surgical Anatomy (Plates 11–15, 1851 edition; Plates 21–25, 1856 edition) (figs. 35–39). Would it be out of place to mention that the faces, musculature, and poses have an oddly familiar look? Some faint resemblance to the figures that appear on the covers of gay pornographic paperbacks of the 1950s and 1960s? Maybe that’s a stretch. But, leaving that aside, we can still place Maclise’s men in the same frame as the soft-core homoeroticism of contemporary and predecessor artworks, all broadly situated in (and licensed by) the grand aesthetic tradition of masculine nudity.

Maclise’s nudes were, of course, anatomized corpses. Was he thereby participating in the mid-century Romantic valorization and eroticization of the dead body? The kind of thing that Paul Hippolyte Delaroche was performing in his over-the-top painting, The Wife of the Artist, Louise Vernet, on her Deathbed (1845/46) and that Edgar Allan Poe adverted to in his famous remark: “The death of a beautiful woman is, unquestionably, the most poetical topic in the world” (also from 1846).69 The timing’s right—the cult of morbid sentimentality was cresting in the 1840s and 1850s—but Maclise’s men don’t fit the mold. That cult mostly scripts the cadaver as an intensely desirable woman, naked or shrouded, cold like marble, impassive but intact, without any decomposition or rupture. The dead body lacks expressiveness, doesn’t answer back, maintains a chaste feminine modesty, even as the occasion of death utterly exposes it to male contemplation. In contrast, the men in Maclise’s gallery stand upright before the reader. They may be cadaveric objects of desire—anatomical narratives of dissectors and body-snatchers played with that necrophilic potential since the early modern era—but with their sensate hands and eyes, they somehow seem alive on the printed page.70

69Maclise lived in a social environment that disapproved of, punished, homoerotic expression and relations. If his erotic attachments were principally directed to men, as we have some reason to suspect, perhaps he took his gallery of men as an imaginary confraternity. Not exactly pin-ups, but a playful projection of desired objects of affection, imaginary friends. A representational consolation for relations and attachments never realized, or (another possibility) figurations of the affective life he did enjoy. Maybe Maclise imagined them as he sketched: transported from the dissecting tables back to life, congregating in student rooms, the medical school lecture hall, or pub …

Coda: Maclise’s Fate and the Queer Anatomical Figure Study

The tradition of figure drawing, founded in the fifteenth century—and reformulated and redefined in centuries of connoisseurial discourse, most notably in the writings of eighteenth-century art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann—was full of sensuality and infused with its own pleasure in Greco-Roman pleasure in, and desire for, idealized hairless, white-marbled, masculine beauty. As Whitney Davis and others have argued, queerness was at the center, not the periphery.71 Unspeakable yet obvious. Those erotic valences were never entirely extinguished by the religious and secular policiers of the intervening centuries. Fine art and the figure study remained a place where the artist could show and play with objects of desire. Yet, certain conventions of modesty governed even sexy Italian and French neoclassical paintings and sculptures. Sensuality received ample expression, but always licensed by some underlying or attached moral frame, a mythological or historical or religious or philosophical reference, or just classicism. Until the provocations of Gustave Courbet and the decadents, artists most often obscured the genitalia by a pose, fig leaf, or some other tactic. In paintings and sculptures where male genitalia did receive representation, the penis could receive no special focus and, following classical precedents, was rendered as small—often disproportionately small. Even so, the male body, and especially the male nude, carried an erotic change. According to art historian Abigail Solomon-Godeau, in European classicist and neoclassicist art, while the female body, nude and clothed, was one focus of erotic representation, and the Herculean muscle man another, they were matched, even overmatched, by the “ephebic” (peri-adolescent, androgynous) male nude. And that’s where things stood, up until sometime in the middle of the nineteenth century (Maclise’s period), when a “crisis in representation” closed down the space for erotic depiction of the ephebic male body, and the female body, pre-eminently the nude, became the privileged signifier of erotic desire.72

71Yet Maclise, uniquely licensed and committed to illustrating the male genitalia—with a sense of himself as an artist in the grand tradition, but located in the domain of medicine, not gallery art—was able to make figure studies of what was scanted in the genre of illusionistic perspectival figure study. And what was scanted in British anatomical and surgical illustration: naturalistic, sensual, proportionate renderings of nude and semi-nude men with genitalia. Images which could be privately archived between the covers of the anatomical book, on the shelves of a medical library, or displayed on the walls of a dissecting room or classroom or lecture hall, openly exhibited to groups of privileged viewers. Shared among men in the homosocial clubs of professional medicine. While hidden from view. The anatomical closet.

Maclise was in, or adjacent to, those clubs. If we can’t say anything definite about his social networks or relations, here’s what we do know. In the 1840s and most of the 1850s, he receives laudatory mentions in the Lancet (then still an oppositional journal, a champion of political and medical radicalism), and attracts notice as a firebrand in the transformism debates.73 As he settles into a career as a practicing surgeon, medical author, and illustrator, his atlases are acclaimed and he is made a Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons.

73But, in spring 1852, he is passed over for an appointment at a London hospital. A less distinguished man is named. (The Lancet protests on Maclise’s behalf.)74 Then, in 1858, at the height of his authorial success, Maclise enters into a pointless two-year-long controversy, which he brings upon himself by penning an off-kilter diatribe against William Harvey’s account of the action of the heart, oddly inserted into On Dislocations and Fractures, a book on an entirely different topic. It was a peculiar provocation—Harvey was a beloved, celebrated icon of British medical science. The convoluted literary tone of Maclise’s diatribe, and convoluted defense of his position in letters to the Lancet, work to discredit him.75 (Was he losing his mind?) In 1861, Maclise turns up as candidate for the position of conservator at the Hunterian Museum. The five applicants are ranked by the committee; Maclise comes in last among them.76 As the 1860s unfold, he produces no new book or article and drops out of the pages of the Lancet and every other medical journal. This turn of events might be a sign that Maclise had lost interest, or Quain didn’t use his pull for Maclise, or didn’t have much pull, or that Maclise was regarded as unserviceable (and worked to make himself so). (A lot was at stake in these matters: Thomas Morton, also Quain’s student, committed suicide when he failed to get a hospital appointment.) What was happening?

74During this period, at some intervals, Joseph lives with brother Daniel in Bloomsbury and Chelsea—the two men were said to be close. (An unmarried sister, Isabella, “keeps house” for them until her untimely death in 1865.)77 Perhaps Maclise decides to concentrate on his surgical practice. Or retires to live off his savings and royalties (if they amounted to anything) or his brother’s fortune (we don’t know anything about the size or disposition of Daniel’s estate). Or takes ill. Or becomes morbidly despondent over the loss of his beloved siblings: Daniel dies in 1870.

77Or stakes a place as a defiant outsider. Maclise was on the far edge and losing side of the debates on evolution, an evolutionist but not a Darwinian. He also courted disfavor by condemning empirical research—in an age of progress, when research programs were abundantly productive, new findings were piling up and receiving acclaim in scientific journals and the press. In the preface to Surgical Anatomy, Maclise fulminates:

78All the sum of facts are long since gathered, sown, and known. We have been seekers after those from the days of Aristotle. And what is … now remaining to be done, if it be not to arrange the facts in hand, with a view to their proper interpretation? Are we to put off the day of attempting this interpretation for three thousand years more, in order to allow these dissectors time for knife-grinding, for hair-splitting, for sawing, chopping, and hammering this pauper corpus mortuum …? How long are they to lead us on this dull road, weed-gathering, tracking out bloodvessels, tricking out nerves, and slicing the brain into still more delicate atoms … in order to coin new names and swell the dictionary?78

No subtleties there. It’s not the only passage in which Maclise bludgeons the opposition, lays out grievances, and expounds on disagreements amounting almost to hatred. If he lays it on thick in his drawings, he lays it on thicker in his prose. To reviewers who called him on his textual excesses, he replies in the “Notice to The Second Edition” of Surgical Anatomy: “I have at times left the beaten march but to seek recreation”, then obscurely breaks off into four not very revelatory sentences on science and nature, in Latin, from Bacon’s Novum Organum. And finishes with this: “I have throughout … recorded ideal and real facts … for the seemingly exhausted subject of Anthropotomy [human anatomy] which have not hitherto been either written, spoken, or known …”79

79Even with the brilliance of his illustrations, rhetoric like that could derail a career. (One imagines readers skipping the introduction and going directly to the plates.) But let’s also entertain the possibility that Maclise might be alluding (consciously or unconsciously) to other things when musing over recreation-seeking off “the beaten march” and “facts … not hitherto … written, spoken, or known …”.

Was there anything? We know that Maclise was in Paris in the 1830s and later traveled with Daniel “over the continent” (Paris, Lyon, Florence, Munich, Naples, Milan, Rome). It is tempting to speculate about what went on in those places: the “continent” was notoriously an occluded zone where British men, especially artists, went to let their hair down, explore aspects of hetero- and homosexuality that were more rigorously policed in their native habitat.80 If that was the case with the brothers Maclise, we might have gotten clues from Daniel’s letters to Charles Dickens. But Dickens, who delivered the eulogy at Daniel’s funeral, destroyed that “immense correspondence, … because I could not answer for its privacy being respected when I should be dead”.81 No letters from Joseph to Daniel or anyone else have thus far turned up, and no letters to Joseph either. Likely also destroyed, as so often happened in nineteenth-century Britain. So a blind spot.

80Then darkness. Quain dies in 1887 and receives chatty (though not entirely laudatory) obituaries in the Lancet and the British Medical Journal.82 In contrast, Maclise, once the Lancet’s pet, receives no obituary, not in the Lancet or any other journal. So what happened? We haven’t a clue. His name drops out of the Medical Directory in 1879 (the year most catalogs and references give as his death date). Maybe he retired in 1879, but there was no announcement. And no announcement or remembrance upon his death from “bronchitis” and “syncope” in 1891. Which also seems odd, considering his distinguished record of publication and distinguished brother.83 The death certificate describes him as a “retired army surgeon”. (That was likely mistaken, but if he did at some point enter the service, that would add another twist to Maclise’s life story.)

82* * *

By the century’s end—a generation after Maclise’s zenith—the old medical order was coming undone. Works like The Anatomy of the Arteries of the Human Body and Surgical Anatomy, while still valued by collectors, no longer seemed modern, and the arty bibliophilic super-sized folio no longer stood securely atop the hierarchy of medical publications. Improvements in surgical techniques and photography bypassed Maclise’s illustrated plates. As enthusiasm shifted to embryology, microbiology, and neuroanatomy, Gray’s Anatomy and similar works rationalized and democratized anatomical publication for a new generation (fig. 40).

Even if Surgical Anatomy retained some usefulness as a practical guide, its visual holism, high aesthetics, cranky politics, and glowing sensuality began to look deficient, old fashioned—maybe a little queer. The tour de force plates, the extraordinary sensitivity to touch, the provocative commentaries had an over-the-top intensity. What did they encode? Thwarted desire for recognition as an artist? Thwarted desire for recognition as a master surgeon and dissector? Thwarted desire for recognition as a misunderstood theorist of transcendental anatomy? Or thwarted desire to openly touch and be touched? Some, or all, of the above.

There was an increasing sense that modern times needed modern texts and modern approaches. Greater specialization brought a new focus on parts. Irrelevant material was even more rigorously excised from the anatomical image, expressive style tamped down, deemed unscientific, behind the times. Heading into the twentieth century, “Art” and “Science” were taken to be antithetical categories. In the new age, as Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison show, the beautiful was repositioned to stand as the enemy of objectivity.84 And if beauty was an enemy, sexy beauty was even more so.

84In this new world, fine art’s truth claims were increasingly siphoned off from some order of independently verifiable objectivity (realist aesthetics and reportage) to a hodgepodge of hard-to-define oppositional essences (symbolism, impressionism, primitivism, cubism, etc.).85 As anatomist and artist, Maclise worked hard to conjure up both kinds of truth telling. But, by the 1890s, that commingling of truths had lost rhetorical salience. In a world that consigned art and science to separate spheres, the twin peaks of scientific illustration were disinterested legibility and objective depiction. Maclise’s coded, sensuous, and multivalent aestheticization—his idiosyncratic style and uniquely personal stamp—queered that. Maclise insisted: “An anatomical illustration enters the understanding straightforward in a direct passage, and is almost independent of written language.”86 Did he ever pause to consider how his own drawings might complicate that precept?

85About the author

-

Michael Sappol, a historian of the visual culture and performance of medicine and science, lives in Stockholm and is Visiting Researcher in the History of Science & Ideas programme at Uppsala University. For many years, he was curator and scholar-in-residence in the History of Medicine Division of the National Library of Medicine. He is the author of A Traffic of Dead Bodies: Anatomy & Embodied Social Identity in 19th-Century America (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2002) and Body Modern: Fritz Kahn, Scientific Illustration and the Homuncular Subject (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2017), and co-editor (with Stephen Patrick Rice) of A Cultural History of the Human Body in the Age of Empire (1800–1920) (Oxford: Berg, 2010). His current projects include: “Anatomy’s Photography: Objectivity, Showmanship and the Reinvention of the Anatomical Image, 1860–1950”; “Queer Anatomies: Medical Illustration, Perverse Desire, and the Epistemology of the Anatomical Closet”; and “Relics of Lost Medical Civilizations”. For links to selected publications, blogs, and websites, see https://swedishcollegium.academia.edu/MichaelSappol.

Footnotes

-

1

This article is taken and adapted from a book-length work-in-progress by the author: Queer Anatomies: Aesthetics and Perverse Desire in 18th- and 19th-century Medical Illustration; or The Epistemology of the Anatomical Closet. ↩︎

-

2

Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality, Vol. 1, An Introduction, trans. Robert Hurley (New York: Vintage, 1990), Parts I and II, especially 44–49. ↩︎

-

3

“The closet is not a grave” is an off-hand allusion to Leo Bersani, “Is the Rectum a Grave?” October 43 (Winter 1987): 197–222. “The telling secret” is from Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Epistemology of the Closet (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2008 [1990]), 67. ↩︎

-

4

Sedgwick, Epistemology of the Closet, 3. ↩︎

-

5

Joseph Maclise, Preface to Surgical Anatomy, 2nd ed. (London: John Churchill, 1856). ↩︎

-

6

Paolo Mascagni, Anatomia universa or Grande anatomia del corpo umano (Pisa: Presso Niccolò Capurro, 1823–1830), Plate 2. Art: Antonio Serrantoni; 98.5 x 71.5 cm. ↩︎

-

7

Michael Sappol, Dream Anatomy (Washington, DC: GPO, 2003). For an influential late eighteenth-century art anatomy full of fantastical macabre scenes, see Jacques Gamelin, Nouveau recueil d'ostéologie et de myologie, dessin‚ d’après nature … pour l’utilit‚ des sciences et des arts (Toulouse: J.F. Desclassan, 1779). But over the course of the nineteenth century, art anatomy pedagogy was also winnowed down to basics: figures posed in the nude, écorché, or as skeleton, without grand gesture, affect, or scenography. ↩︎

-

8

William Hunter, The Anatomy of the Human Gravid Uterus (Birmingham: John Baskerville, 1774); and John Bell, Engravings of the Bones, Muscles, and Joints, Illustrating the First Volume of the Anatomy of the Human Body, 2nd ed. (London: Printed for Longman and Rees, 1804 [1794]). Yet, despite their endorsement of anatomical sobriety, Hunter and Bell choreographed and orchestrated provocative image play. ↩︎

-

9

Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Between Men: English Literature and Male Homosocial Desire (New York: Columbia University Press, 1985). For erotics as the boundary of aesthetic pleasure, see also Abigail Zitin, “Wantonness: Milton, Hogarth, and The Analysis of Beauty”, Differences 27, no. 1 (2016): 25–46. ↩︎

-

10

For the social aims of high medical publication, and the way in which knowledge production affirmed claims of authority and the search for patronage and prestige, see Carin Berkowitz, “The Illustrious Anatomist: Authorship, Patronage and Illustrative Style in Anatomy Folios, 1700–1840”, Bulletin of the History of Medicine (2015): 171–208. ↩︎

-

11

Richard Quain, Anatomy of the Arteries of the Human Body, with its Applications to Pathology and Operative Surgery: In Lithographic Drawings with Practical Commentaries [“drawings from nature and on stone by Joseph Maclise”] (London: Printed for Taylor and Walton, 1844); “imperial folio”; 67 cm. Quote from “Review of New Books: The Anatomy of the Arteries of the Human Body, with its Applications to Pathology and Operative Surgery, in Lithographic Drawings, with Practical Commentaries. By Richard Quain, &c. &c. The Delineations by Joseph Maclise, Esq. Surgeon. Parts I and II. London: Taylor and Walton. 1840”, Provincial Medical & Surgical Journal 1–1, no. 12 (19 December 1840), 203, DOI:10.1136/bmj.s1-1.12.203. ↩︎

-

12