Joseph Maclise, Taylor & Walton, and Publishing on Gower Street in the 1840s

Joseph Maclise, Taylor & Walton, and Publishing on Gower Street in the 1840s

By William Schupbach

Abstract

The Anatomy of the Arteries of the Human Body (1840–1844), with text by Richard Quain (1800–1887) and lithographs by Joseph Maclise (1815–1880), was Maclise’s first publication, his largest work, and in some ways his most ambitious. How then, could it feature the work of a debutant author? Who were the people involved in its production? What professional skills were required to produce such a work? What factors enabled them to carry it to a successful conclusion? The answer suggested is that much of the burden of production fell upon the publisher, John Taylor (1781–1864), whose previous and current career provided him with the experience required for such a task. Taylor had little experience in lithographic publishing, but his three lithographic publications before The Anatomy of the Arteries of the Human Body proved a good practice ground for the much larger and more accomplished work by Maclise. Taylor was involved not only in his role as the official publisher of University College, London, where Maclise’s work was carried out, but also in the sale of the finished work, and the storage of the lithographic stones. The Anatomy of the Arteries of the Human Body can therefore be understood as a team production, produced in a manner comparable to earlier illustrated anatomy books by Andreas Vesalius and William Hunter.

Introduction

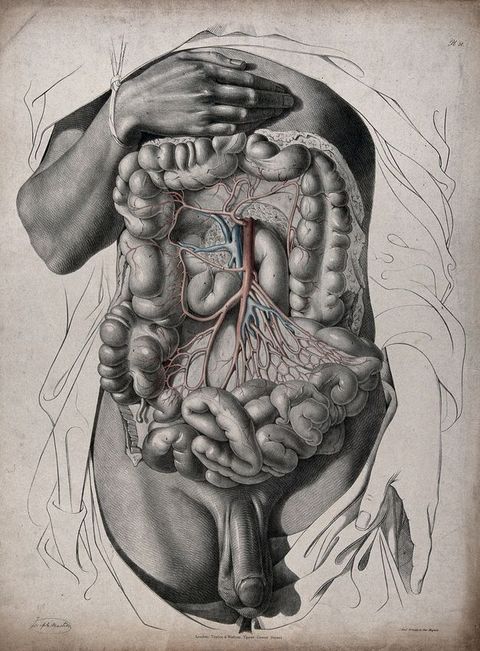

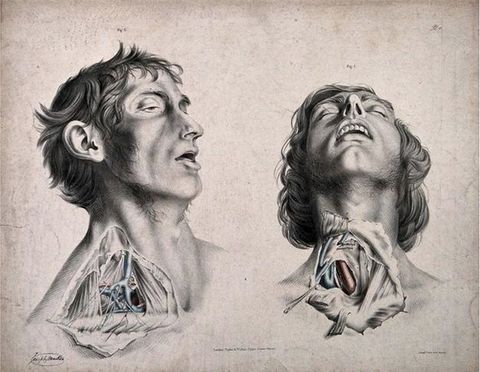

Anyone looking at the large and impressive lithographs issued with the title The Anatomy of the Arteries of the Human Body at the time of its publication in 1840–1844, must have been astonished and impressed (fig. 1). The lithographs are large and numerous, drawn in a dashing but careful style; the dissections are sophisticated in technique; detailed studies of arteries are combined with portraits of dead patients; and the suffering human figures are imbued with pathos. Most people at the time would have seen nothing like it.

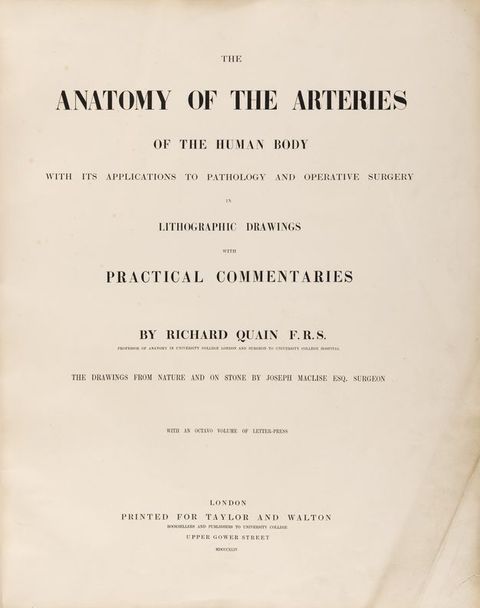

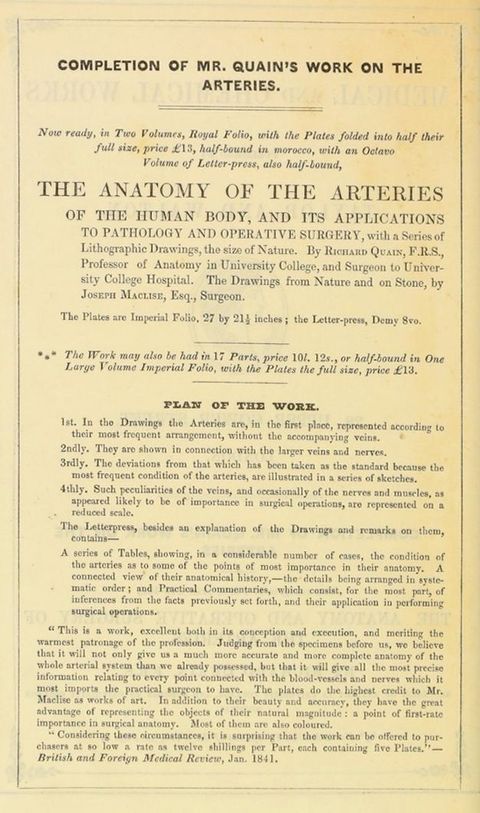

It would be natural to ask who was responsible for this impressive work. The most spectacular contribution is that of Joseph Maclise (1815–1880), however, he was not “the” creator, or the sole creator, of the work. Despite his eye-catching and indeed emotionally charged lithographs, he could be considered the junior contributor, in that this was his début publication. When the lithographs were first issued in 1840–1842, the advertisements contained no mention of Maclise: the artist was ignored.1 A title page, printed in 1844 after the work had already been issued in fascicules (parts) from 1840 onwards, proclaims in bold characters that it is “by Richard Quain F.R.S.”. A lower credit line in smaller and more compressed characters adds “the drawings from nature and on stone by Joseph Maclise, surgeon”, and the imprint at the bottom of the page, in middling-sized characters, identifies the publisher with the words “Printed for Taylor and Walton, booksellers and publishers to University College, Upper Gower Street” (fig. 2). The five names—Quain, Maclise, Taylor, Walton, and University College—are all significant. Richard Quain (1800–1887) was an experienced author, surgeon, and academic, a fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons of England (1843) and a fellow of the Royal Society (1844). Taylor and Walton had been publishing for nearly twenty years. University College was the institution, which brought all four men together in the Bloomsbury and Fitzrovia districts of London. Behind and alongside the four named contributors were many other artisans, businesspeople, and academics, who shaped the publication behind the scenes. There were also vectors, such as geographical co-location and communities of interest, that brought these players together and enabled them to generate the finished product.

1

If we could gather the detailed evidence for a network of actors of which Joseph Maclise was a member, its intention would not be to “decentre” Maclise, for he has not hitherto been regarded as at the centre of anything. Instead, it would be to place him in the context in which he worked. The extent to which large illustrated books are produced by a team, not by a single individual, has been described in other cases, such as the botanical magnum opus of Leonhart Fuchs De historia stirpium, published in Basel in 1542; the De humani corporis fabrica authored by Andreas Vesalius in 1543; and the work on the human gravid uterus written by William Hunter and published in 1774, which brought together in Westminster artists from the Netherlands, engravers from France, an obstetrician from Glasgow, and a printer in Birmingham, as well as anatomical subjects (women and babies) in London.2 Outside the anatomical and botanical fields, the Nuremberg Chronicle of Hartmann Schedel, printed in Nuremberg in 1493, has been the subject of many studies synthesising its sources and contributors.3 The names of Vesalius, Fuchs, Hunter, and Schedel attached to these works in catalogues can cast into shadow the teams supporting them.

2A balance can be struck between the inspirations of individuals and the effectiveness of the teams. As a model, one can point to the exhibition and its accompanying publication Printing and the Mind of Man, from 1963, which marked five hundred years of printing with moveable type.4 The entry for an edition of Virgil’s works published in Paris in 1767 places the printer’s name in the headline (Joseph-Gérard Barbou), but describes the roles of no fewer than nine people in the production of the work, including illustrators, engravers, publishers, a typographer and a bookseller.5 Is it possible to carry out a similar exercise for The Anatomy of the Arteries of the Human Body?

4Joseph Maclise and John Taylor

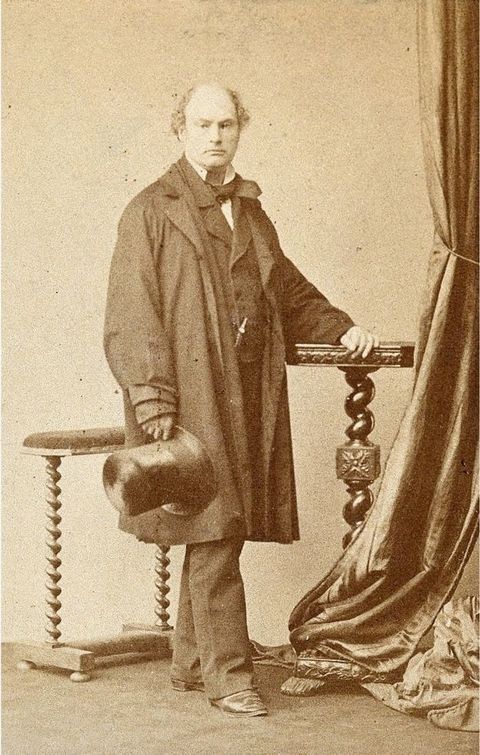

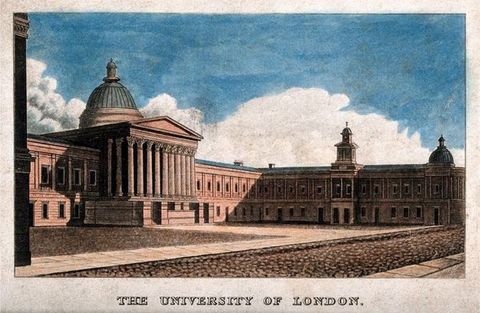

Let us start by looking at Joseph Maclise’s circle. He and his brother, the painter Daniel Maclise (1806–1870) (fig. 3), formed one of two pairs of brothers who migrated from Cork in Ireland in the 1820s and 1830s and found a home in the same area of London. The other pair were the Quains: Jones Quain (1796–1865) and Richard Quain (1800–1887) (figs. 4 and 5). The quartet of Quains and Maclises gravitated to Bloomsbury and Fitzrovia, and the institution to which three of the brothers were attached was University College, London (UCL): Jones Quain as professor of general anatomy, Richard Quain as senior demonstrator and lecturer on descriptive anatomy, and Joseph Maclise as a student and junior colleague of Richard Quain. UCL had opened in Bloomsbury in 1828 and was transforming the whole area (fig. 6).

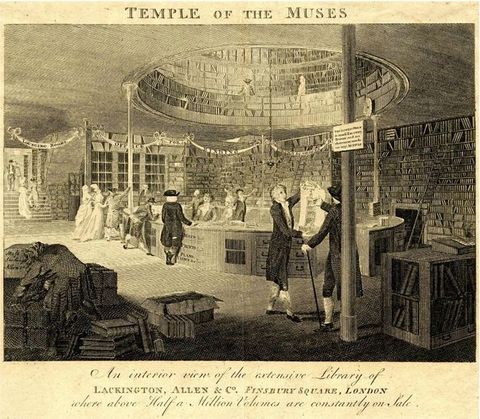

Soon after its foundation in 1826, UCL appointed an official publisher and bookseller. Although UCL strove to differentiate itself from the ancient universities of Oxford and Cambridge, it was in this respect emulating them. The person appointed to this role was John Taylor (1781–1864) (figs. 7 and 8). Taylor was born into a bookish family in East Retford, Nottinghamshire: his father was a bookseller and printer there, and John Taylor’s working life started in his father’s shop.6 He left for London in 1803 and worked for the publisher-bookseller James Lackington (1746–1815) in Finsbury Square (fig. 9). There, he learned about the balance between the public demand for books and what authors wanted to supply, the value of copyrights, and the management of a large book-based business. In 1804, he moved on to another firm of publishers, Vernor & Hood: their list included recreational verse and romances, but also—significantly for Taylor’s later career—more practical literature, such as books on manures, brewing, and the management of plantations. Works of popular science that Vernor & Hood published in Taylor’s time included A Treatise on the Art of Bread-Making (1805) and an inexpensive edition of Lavater’s Essays on Physiognomy (1806).7

6

In 1806, Taylor formed his own publishing and bookselling partnership by joining James Augustus Hessey (1785–1870) in the new firm of Taylor & Hessey. Taylor was the publisher and Hessey the bookseller. Both sides of the operation were run from 93 Fleet Street until 1823, when Taylor moved the publishing business to Waterloo Place in the West End. The partnership continued until 1825.8

8One of the lessons of Taylor’s earlier career was the volatile nature of the publishing business. Some authors would need a lot of help, encouragement, editing, and money before delivering their copy; many publications would hardly sell at all; and the poisonous rivalries among influential reviewers could destroy an author’s reputation. The writers whom Taylor published in the earlier half of his career, and who are best known today, were the poets John Keats (1795–1821) and John Clare (1793–1864): they were also among his most labour-intensive and least rewarding financially. Taylor found himself begging the editor of a review journal not to give an unfavourable review for Keats’s early work (in vain).9 In verse offered up for publication, John Clare insulted the wealthy while he himself was being supported by a wealthy patron.10 Clare also required prolonged financial support, which he received from Taylor and others, to maintain him in his years of mental illness.11

9Publishing was a far from stable business. Taylor & Hessey nearly went under in 1817, as profits in the publishing arm were exceeded by losses in bookselling. In 1826, a crash destroyed much of the industry, with well-established firms such as Hurst, Robinson & Co. going out of business. Taylor’s firm often had to be bailed out by his brother James, a banker in Nottinghamshire.12

12In an attempt to cover themselves, firms such as Vernor & Hood hedged their bets by diversification: losses from risky early works by unknown young poets such as Keats could be offset by steady sales of standard fare. This balancing act was the central story of Taylor’s professional life, and of his subsequent reputation. Exciting works by brilliant writers such Keats, Clare, Charles Lamb, Thomas De Quincey, and Samuel Taylor Coleridge aroused the interest of literary critics and subsequently historians, and contributed to Taylor’s renown. However, it was not those authors who saved the firm in the crises of 1817 and 1826. What saved it was the continuing level of sales in popular literature: spelling books, history cribs, simplified science, teach-yourself manuals, moralistic tracts on early rising, and catechisms.13 Contrasting the two types of product, Tim Chilcott in his biography of Taylor calls the latter “the publishing of uninspired mediocrity”.14

13Despite his later fame as a literary publisher, in the first phases of his career, Taylor had a personal predilection for factual knowledge. Though he had received an education in Lincoln and Retford grammar schools, his academic knowledge of the world was self-acquired. It became extensive: among other subjects, he published works on the metric system, on the relation between money and value, on arithmology, and on the authorship of the Letters of Junius. In his later career as a publisher in Bloomsbury, his journey away from romances, epic poems, and light essays continued, but the range of “serious subjects” that he published would be vastly increased through his contacts in University College, London, including the Quains and Joseph Maclise.15

15John Taylor and UCL

Taylor and Hessey split up in 1825.16 For Taylor, the ending of the partnership turned out well, as it enabled him to start a new career in association with University College, London, founded in 1826 and opened on Gower Street in 1828. On his appointment as the official publisher and bookseller to the new university, Taylor set up in business, initially at 30 Upper Gower Street (circa 1828–1830). He then changed his publishing address to 28 Upper Gower Street, the house next door but one to the north, while continuing to occupy no. 30 as well. No. 28 Upper Gower Street, on the corner of Upper Gower Street and University Street, became his publishing address: it was directly across Upper Gower Street from UCL to the east, and was directly across University Street from the North London Hospital (renamed from 1837 University College Hospital) to the north. The sites of both houses (28 and 30) were later occupied by the UCL medical school library. Today, they form the site of UCL’s Grant Museum, appropriately, since one of the first books that Taylor published from 30 Upper Gower Street was Robert Edmond Grant’s inaugural lecture at UCL, An Essay on the Study of the Animal Kingdom (1828) (fig. 10).17 Here Taylor was easily accessible to UCL professors, students, and habitués, many of whom lived or worked nearby.18

16

Around 1836, the firm John Taylor changed its name to Taylor & Walton: “Walton” has never been identified.19 No. 28 Upper Gower Street continued as the address of Taylor and Walton throughout its existence, and remained so after Taylor’s retirement in 1853. For nearly forty years, the house on the corner of University Street and Gower Street was the powerhouse of academic publishing in Bloomsbury. Joseph Maclise and the Quains must have spent a good deal of time there preparing their major anatomical works published by Taylor & Walton in the early 1840s.

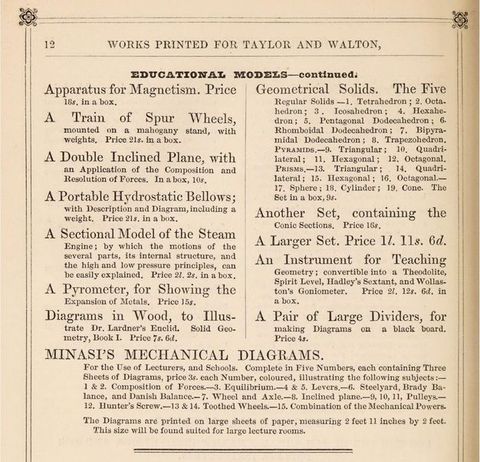

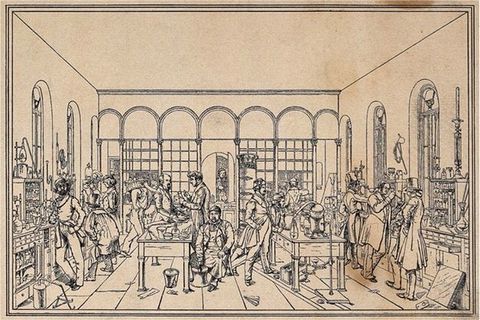

19The tenor of the publishing list to which The Anatomy of the Arteries of the Human Body belonged can be reconstructed from library catalogues and from the advertisements bound in at the ends of many of Taylor’s publications (fig. 11). The books published by Taylor were overwhelmingly educational, academic, and professional, not recreational. His subjects included not only natural and medical sciences but also antiquities, maps, music, “educational models for the use of schools, mechanics’ institutions, and for private instruction”, grammars, literature (Greek, Latin, and Italian), and “works of general interest”. Singing manuals and drawing instruments (including models, pencils, chalks, and porte-crayons) were advertised alongside anatomical volumes and monographs on chemistry. Taylor was a prolific advertiser of technical charts by his neighbour Carlo Minasi (1817–1891), who resided and taught music at various addresses around Euston Grove: “Minasi’s mechanical diagrams” remained in his stock for years.20 Taylor published sixteen works by or associated with the new applied chemistry of Justus von Liebig (1803–1873) between 1840 and 1851, and a lithograph of Liebig’s laboratory (fig. 12). Among the literary classics available from Taylor and Walton in 1842 was even “Keats’s poetical works, with portrait by Hilton”: the poet whom Taylor & Hessey had nursed into print thirty years before was now being republished posthumously by Taylor as a classical author for educational use in schools.21 Taylor & Walton books which today are still in their original bindings were modestly bound in brown, black, or dark green cloth by the firm of Remnant and Edmonds, founded in 1837 and one of the largest binderies in London.22

20

The Use of Lithography by Taylor & Walton

There is a conspicuous contrast between the anatomical lithographic publications by Taylor and the rest of his output. Most of the books published by his firm were of modest size and cheaply printed by a range of commercial letterpress printers.23 As the publisher of Taylor & Hessey, he had published books that were entirely or mainly unillustrated. As the publisher to UCL after 1828, he started in the same manner: most of his books consisted of small (octavo) volumes, printed in a routine manner and, if illustrated at all, for instance to show chemical apparatus, the book would have small wood engravings on the same pages as the text.24

23If wood engravings would not suffice, for example, if tone was required as well as line, the next resort would be steel engravings printed on their own sheets separately from the text and bound in as a frontispiece or as separate pages of plates. Both the wood engravings and the steel engravings were on a small scale, suitable for inclusion in an octavo volume (around 20 cm in height). The volumes could be bought and sold relatively cheaply.25

25However, these techniques, while suitable for small illustrations of such subjects as antiquities, histology, or botany, would not scale up for detailed illustrations of larger subjects such as anatomy and surgery. For that purpose, lithography was required: lithographs were easier and cheaper to make on a large scale; they could successfully simulate drawings, and their soft tone (compared with steel engravings) made them easier to colour by hand. They could not easily be printed on the same page as letterpress, but there were ways around that: the letterpress could be printed in a companion volume, or on separate sheets bound with the lithographs.26

26Taylor was confronted with the need to scale up to lithography early in his career with UCL, when he was still publishing as a lone operator at 30 Upper Gower Street (before the partnership Taylor and Walton came into existence at 28 Upper Gower Street). In 1832, he issued The Principles and Practice of Obstetric Medicine, by David Daniel Davis, which required large scale, and therefore lithographic, illustration. To realise the obstetric lithographs for Davis, Taylor approached the lithographic specialist Charles Joseph Hullmandel (1789–1850), whose lithographic press and office was in Great Marlborough Street, south of Oxford Street.27 The lithographs for Davis’ publication were drawn on stone by artists who frequently worked for Hullmandel.28 The finished work, consisting of two volumes of letterpress and one volume of lithographs, was produced between 1832 and 1836.

27The production of Davis’ work on obstetrics required of Taylor (and of Taylor & Walton) resources far in excess of their usual letterpress output, in the form of draughtsmen, lithographers, lithographic printers, and storage of the lithographic stones, over a period of at least four years. However, it provided good experience for a series of increasingly ambitious anatomical and medical lithographic publications, which culminated in The Anatomy of the Arteries of the Human Body. The most ambitious of these lithographic publications before Quain-Maclise was a multi-volume work with text by Jones Quain. Like the later Maclise volume, it was the work of many hands. Issued in five large but not thick volumes between 1836 and 1842, it had the generic title Anatomical Plates, with subtitles referring to the vessels, nerves, viscera, bones, and ligaments. In artistic virtuosity, the artists (J. Walsh and William Bagg) fall far below the standard that would be set later by Maclise. The dominant figure on the publication was William James Erasmus Wilson (1809–1884), in later years Sir Erasmus Wilson.29 Most of the lithographs in Anatomical Plates have the credit line “W.J.E. Wilson direxit”, a role with no equivalent in the Quain-Maclise Anatomy of the Arteries of the Human Body.

29Between the publications of the Quain brothers (Jones Quain with Erasmus Wilson and Richard Quain with Joseph Maclise) had come a smaller work with folding lithographic plates by another set of brothers: Thomas Morton the anatomist (1813–1849) and Andrew Morton the artist (1802–1845). Like the Quain–Wilson volumes, the Mortons’ slim volumes had a generic title, The Surgical Anatomy of the Principal Regions of the Human Body, followed by a subtitle for each volume referring to the region concerned. The volumes started to appear in 1838, with lithographs by Fairland after Andrew Morton. There is a possible link between Morton and Maclise: Andrew Morton’s signature or AM monogram, as artist, appears prominently written on the stone on each plate, surrounded by a circle, just as Maclise’s would appear in his plates. The Morton series, focusing on surgical anatomy like the Maclise series, was Taylor’s last work in lithography before attempting the much larger Maclise production.

The importance, for Maclise, of Taylor’s willingness to scale up from letterpress publishing to lithography, is shown by a remark by Robert Harrison (1796–1858). Harrison, professor of anatomy at Trinity College Dublin, had written a detailed book title The Surgical Anatomy of the Arteries, which went through at least four editions between 1824 and 1839, indicating its value as a dissecting aid. But it assumed that readers had the actual arteries laid out before them. As Harrison commented,

30At the time I commenced this work I contemplated having coloured plates explanatory of the relative anatomy in those situations where operations on the arteries may be required; on reflection, however, I abandoned the idea, as the number of drawings that were required must have added considerably to the size and expense of a work designed for the student in the dissecting room …30

The drawings and coloured lithographs did indeed add considerably to the complexity of Maclise’s production, but it was a challenge that, by 1840, John Taylor was prepared and equipped to take on.

Taylor, Maclise, and The Anatomy of the Arteries of the Human Body

With Taylor successfully expanding his repertoire from small-scale letterpress to large-scale lithography, what was the finished product? The lithographs of The Anatomy of the Arteries of the Human Body were issued in fascicules between late 1840 and 1844. The full title was The Anatomy of the Arteries of the Human Body: With Its Applications to Pathology and Operative Surgery. In Lithographic Drawings, with Practical Commentaries. Richard Quain was the author of a small (octavo) letterpress volume, while Maclise was the author of the large lithographs, Taylor was the publisher, and Jeremiah Graf is named on some of the plates as printer of the lithographs.

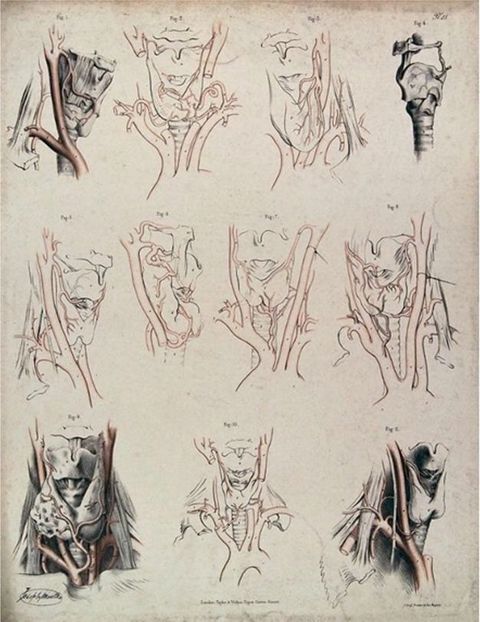

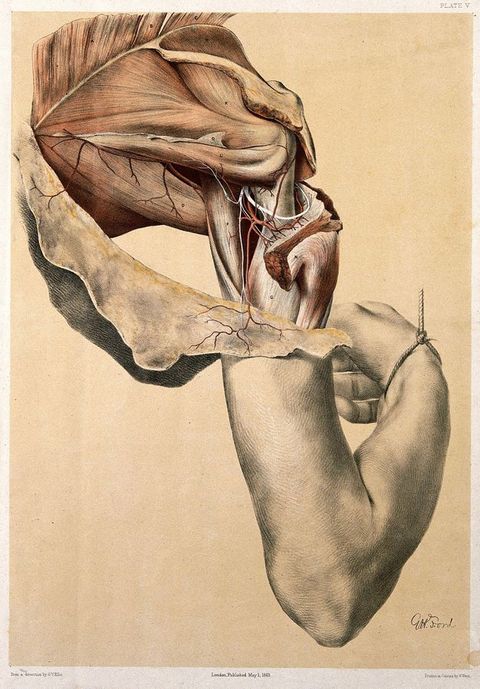

Maclise portrayed the dissected corpses as tragic heroes and heroines, struggling or having given up the struggle for life, with the scissors and other tools of the anatomist included in the picture as instruments of their passion. Together with the fine portraits of the heroic victims, there are detailed sheets of technical diagrams showing how arteries relate to viscera, bones, and veins, for the benefit of surgery students: these also have a sense of movement produced by strong diagonals and broken lines (figs. 13 and 14).

Advertisements for Quain and Maclise’s work started to appear in 1840, stating that it will be “above 13 parts Imperial folio and an octavo volume of letterpress. A part containing five plates with its accompanying letterpress will appear on the 1st of every month” (fig. 15).31 Imperial Folio measured 27 by 21½ inches (68.5 x 54.6 cm). Normally, Quain was mentioned in Taylor’s advertisements but Maclise was not, since the name Quain was known in anatomical circles (even when, as in this case, it was normally the other Quain brother, Jones, who was the well-known one).

31

However, Taylor & Walton did quote the reviewer in the British and Foreign Medical Review in 1841, as saying: “The plates do the highest credit to Mr Maclise as works of art”. That anonymous reviewer went on to say: “In addition to their beauty and accuracy, they have the great advantage of representing the objects of their actual magnitude, a point of first-rate importance in surgical anatomy. Most of them are also coloured.”32

32The genesis of the work was described in the preface by Richard Quain. He had compiled notes on the arteries in 930 cadavers, which he had dissected at UCL medical school. On examining them with a view to publication,

33[I]t became obvious that their utility would be very limited, unless as a part of a full history of the arteries with adequate delineations. … To carry out my views as to the delineations, I obtained the assistance of my friend and former pupil Mr Joseph Maclise. In reference to that gentleman’s labours, it may be allowed me to say, that while I have had the cooperation of an anatomist and surgeon, obviously a great advantage, the drawings will, I believe, be found not to have lost in spirit or effect. It affords me much gratification to render my acknowledgments to Mr Maclise, for the readiness with which he acceded to my wishes, and undertook so arduous a task, and the zeal with which he has devoted himself to it in the intervals of application to the duties of his profession.33

Quain explains that the work differs from three earlier illustrated works on the arteries (by Albrecht von Haller, Antonio Scarpa, and Friedrich Tiedemann), in showing the variations which the main arteries can demonstrate from person to person, and by showing them in relation to veins, nerves, and viscera. He did not need to say, but it may be worth emphasising today that, during the speedy operations conducted without anaesthesia, it would be easy for a hasty surgeon to cut a major artery by mistake, with fatal consequences, if the surgeon encountered an unexpected variation in the course of an artery. Maclise helped to give this lesson mnemonic force by including drop-shadows under the arteries, which gives them a three-dimensional appearance.

In marketing the work, Taylor employed a range of options. Although the fascicules of plates were issued between late 1840 and 1844, already in 1842 Taylor and Walton were offering purchasers the option of having them bound in one huge volume of enormous weight with the plates folded in the gutter of the book, or in two lighter volumes with the plates not folded.34 Also, in 1842, Taylor and Walton were announcing that Parts I to XIV were now available, priced at 12 shillings each.35In 1843, they were adding that Part XVII (the last) “will shortly be published”.36 In the meantime, the first seven parts could be bought bound in one volume for five guineas, folded or unfolded. The more substantial single volumes were offered sturdily bound in cloth, while the lighter two-volume set was available from the publishers in a more elegant form with the spine and corners bound in leather. Purchasers of the individual fascicules could have them bound any way they liked, or not at all, and could keep them in a portfolio instead.

34A new title page dated 1844 replaces the earlier “delineations” acknowledgment: “The drawings from nature and on stone by Joseph Maclise”. Perhaps this reflects the publishers’ growing realisation of quite what would be involved in producing such a massive corpus of lithographs. It tells us that Maclise had not only carried out the original drawings, presumably in pencil or chalk and watercolour, but was also recreating them, no doubt with amendments, on lithographic stones. Unusually, Taylor and Walton were not employing a professional lithographer on this publication. They had done so when publishing Jones Quain’s series of volumes Anatomical Plates (1834–1840), but in The Anatomy of the Arteries of the Human Body, Maclise, having created the composition and the drawing, was now carrying out a third role, that of lithographer.

In 1844, Maclise celebrated the conclusion of the massive work with a return visit to Paris with his brother, the painter Daniel Maclise (they had both studied there in the 1830s). The purpose of Daniel’s visit was to study French mural paintings, in preparation for his submissions to paint the murals in the new British Houses of Parliament. We do not know what Joseph did there. Meanwhile, back in London, Taylor continued to sell copies of The Anatomy of the Arteries of the Human Body, though the unwieldiness of the publication caused him some problems. In October 1846, Taylor and Walton’s advertisement states that “The plates will be contained in a portfolio, superseding the necessity of binding”. They added that, owing to the difficulty of storing the stones, they were proposing to print up to five hundred copies and then wipe the stones. The five hundred copies would, they imply, be additional to copies already sold.37 The offer to sell the plates in a portfolio would not only relieve purchasers of binding, but would also permit them to hang up individual plates in the dissecting room or study, to distribute individual lithographs of specialist subjects to those who wanted them, and to discard those that were of less or no interest. The storage of the eighty-seven massive stones must have been a major problem for the publisher, whether they were with the printer (Jeremiah Graf) or cluttering up one of Taylor’s two Gower Street houses. The offer worked for, by November 1847, Taylor was announcing that four hundred and fifty of the five hundred copies had been subscribed for, of which four hundred had been delivered. By 1 March 1848, “460 out of the 500 copies have been subscribed for and delivered”.38

37In July 1849, Taylor (by then publishing as Taylor, Walton and Maberly) announced:

39Mr Quain’s work on the arteries. The publishers beg to inform subscribers to this work, that the drawings on the stones have been destroyed. It is, therefore, not possible to increase the number already printed. About fifty copies remain unsold, for which early application is requested. They will, for the present, be supplied at the subscription price, 6l 6s [six guineas].39

This price was roughly half the price asked for the original bound volumes of the entire set, but if Taylor had already recouped his expenses on the earlier edition, the income from these 460 extra copies would have been clear profit.

After The Anatomy of the Arteries of the Human Body

After the publication of The Anatomy of the Arteries of the Human Body, Taylor and Walton published Maclise’s next work, Comparative Osteology, in 1847. This time, Taylor and Walton advertised the work extensively, naming Maclise as the author. By 1846, Joseph Maclise was a name worth mentioning.40 However, Comparative Osteology was Joseph Maclise’s last work with Taylor and Walton. Although he continued to practise medicine nearby in Fitzrovia, he placed his subsequent works Surgical Anatomy (1851) and On Dislocations and Fractures (1859) with the firm of John Churchill. Churchill was a specialist medical publisher, well capitalised, and also well connected with the affluent medical world of the West End.41

40After that, Joseph Maclise disappears into medical practice and his artistic talent is no longer in evidence. The Anatomy of the Arteries of the Human Body had made sufficient impact on Taylor and Walton to encourage them to produce one further major set of anatomical lithographs: this was Illustrations of Dissections, in a Series of Original Coloured Plates, the Size of Life (1867), for which George Viner Ellis (an assistant and then the successor to Richard Quain as professor of anatomy at UCL) reprised his predecessor’s role as the anatomist, while George Henry Ford (1812–1900) sat metaphorically in Joseph Maclise’s chair, making the drawings from nature and then copying them on to stone (fig. 16). Compared with The Anatomy of the Arteries of the Human Body from twenty years earlier, Viner Ellis and Ford’s publication is an updated work in the same genre: it was published from Taylor and Walton’s house in Gower Street, by James Walton, after Taylor had retired, and used the new technique of chromolithography instead of the hand colouring employed in Maclise’s day (red for arteries and blue for veins being a vital distinction). Despite the technical differences, the work of Viner Ellis and Ford could not have been published by Walton without the precedent of Quain-Maclise.

Conclusion

As behind-the-scenes enabler, John Taylor was a major contributor to The Anatomy of the Arteries of the Human Body. Behind Taylor were UCL and the Bloomsbury-Fitzrovia professoriat, especially in the UCL medical school. In anatomy, the leading figure at UCL was Richard Quain. It was UCL which brought together John Taylor, Joseph Maclise, and Richard Quain: the team that produced The Anatomy of the Arteries of the Human Body.

The work could only be produced because Taylor was willing to learn and adopt large-scale publication of lithography—a step outside his previous publishing experience. Before Maclise, he was introduced to it through Davis, Erasmus Wilson, and the Morton brothers. After Maclise, his firm was able to publish Viner Ellis, applying new chromolithographic printmaking methods to an existing genre. As much can be learned about a work, or corpus of works, by studying the context in which the publisher published it, as by studying the lives of the artists or writers who are more typically associated with its production."

About the author

-

William Schupbach is a member of the Research Development Team at the Wellcome Collection, and has previously held other posts in the Wellcome Trust on Euston Road in London. There he has been involved in acquiring new works for the collection, organising exhibitions, supporting research in the collection, and building up the online catalogue of the Wellcome collections of prints, drawings, photographs, and paintings. He has published on various aspects of historical iconography.

Footnotes

-

1

George Viner Ellis, Demonstrations of Anatomy: Being a Guide to the Dissection of the Human Body (London: Printed for Taylor and Walton, 1840), advertisements at end in some copies; and H. Bence Jones, On Gravel, Calculus & Gout: Chiefly an Application of Professor Liebig’s Physiology to the Prevention and Cure of these Diseases (London: Printed for Taylor and Walton, 1842), advertisements at end in some copies. ↩︎

-

2

Sachiko Kusukawa, Picturing the Book of Nature: Image, Text, and Argument in Sixteenth-Century Human Anatomy and Medical Botany (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2012); C.D. O’Malley, Andreas Vesalius of Brussels (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1964); and W.F. Bynum and Roy Porter, eds., William Hunter and the Eighteenth-Century Medical World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985). ↩︎

-

3

Christoph Reske, Die Produktion der Schedelschen Weltchronik in Nürnberg (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2000) (Mainzer Studien zur Buchwissenschaft, 10); and Stephan Füssel, Hartmann Schedel, Chronicle of the World: The Complete and Annotated Nuremberg Chronicle of 1493 (Cologne: Taschen, 2001). ↩︎

-

4

Printing and the Mind of Man; Catalogue of Exhibitions at the British Museum and at Earls Court, London (London: F.W. Bridges & Sons, 1963). ↩︎

-

5

Printing and the Mind of Man Part II, “An Exhibition of Fine Printing in the King’s Library of the British Museum, July–September 1963”, 38, no. 113. ↩︎

-

6

Tim Chilcott, A Publisher and His Circle: The Life and Work of John Taylor, Keats’s Publisher (London: Routledge, 1972). ↩︎

-

7

Richard Kirwan, The Manures Most Advantageously Applicable to the Various Sorts of Soils, and the Causes of Their Beneficial Effect in Each Particular Instance (London: Vernor & Hood, 1796 [three editions], 1801, 1802, 1806, and 1808); Michael Combrune, The Theory and Practice of Brewing (London: Vernor & Hood, 1804); Dr Collins, Practical Rules for the Management and Medical Treatment of Negro Slaves, in the Sugar Colonies, by a Professional Planter London: Vernor & Hood, 1803. Related works later published by Taylor, after he left Vernor and Hood, include: Justus Liebig, On Artificial Manures (London: Taylor & Walton, 1845); and George Darling, Instructions for Making Unfermented Bread: With Observations on Its Properties, Medicinal and Economic (London: Taylor & Walton, 1847). ↩︎

-

8

Chilcott, A Publisher and His Circle, 23–85 and 177–179. ↩︎

-

9

Chilcott, A Publisher and His Circle. Once this source is accessible after the current COVID-19 restrictions pass, references to this source throughout the article will be updated with the page numbers. ↩︎

-

10

Chilcott, A Publisher and His Circle. ↩︎

-

11

Chilcott, A Publisher and His Circle. ↩︎

-

12

Chilcott, A Publisher and His Circle, 63–64 and 183–185. ↩︎

-

13

Chilcott, A Publisher and His Circle, 187–188. ↩︎

-

14

Chilcott, A Publisher and His Circle, 67. ↩︎

-

15

John Taylor (1781–1864), the founder of the publishing firm Taylor and Walton, is not to be confused with another man who had a similar career, Richard Taylor (1781–1858), the founder of the publishing firm Taylor and Francis. Both specialised in scientific publishing in London in the same period. John was from Nottinghamshire and his scientific publishing business was based in Bloomsbury, while Richard was from Norfolk and his publishing house was located in Red Lion Court, Fleet Street. ↩︎

-

16

Chilcott, A Publisher and His Circle, 177–179. ↩︎

-

17

Taylor gives the address as no. 30 as late as 1836 (title page to Augustus De Morgan, The Connexion of Number and Magnitude: An Attempt to Explain the Fifth Book of Euclid (London: Printed for Taylor and Walton, booksellers and publishers to the University of London, 30 Upper Gower Street, 1836). Thereafter, he uses 28 as his publishing address. Post Office Directories (e.g. for 1841, page 264) show him at both addresses: “28 Taylor & Walton booksellers, &c. … 30. Taylor, John, esq”. ↩︎

-

18

For example, Edward Turner, professor of chemistry at UCL, was at 38 Upper Gower Street; the anatomist G.W. Hind was at 66 Gower Street; and the mathematician Augustus De Morgan was at 60 Gower Street. (Charles Darwin was even nearer, at 12 Upper Gower Street, but unfortunately was not publishing monographs at the time and had no position in the university.) The professor of pathology at UCL, Walter Hayle Walshe, was in Upper Charlotte Street, Fitzroy Square, while to the north, another of his authors, Samuel Kidd, professor of Chinese at UCL, was in Camden Town. David Daniel Davis, professor of midwifery at UCL and obstetric physician to the North London Hospital (the future University College Hospital) lived at 4 Fitzroy Street, Fitzroy Square, and subsequently at 17 Russell Place, Fitzroy Square, near Joseph Maclise, who was at 14 Russell Place. Russell Place was the stretch of Charlotte Street between Howland and Maple Streets: after 1867, it became the southern part of Fitzroy Street. “Fitzroy Street”, in Survey of London: Volume 21, The Parish of St Pancras Part 3: Tottenham Court Road and Neighbourhood, ed. J.R. Howard Roberts and Walter H. Godfrey (London, 1949), 44–46. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol21/pt3/pp44-46. The addresses given here are found in Post Office directories and prefaces by these authors to works published by Taylor & Walton. ↩︎

-

19

After Taylor’s retirement, the firm traded as James Walton (circa 1867–1871?), at the same address as before (albeit renumbered by the Post Office from 28 Upper Gower Street to 137 Gower Street). Whether James was the original partner in Taylor and Walton, founded thirty years before, has not been ascertained. The firm predominantly called itself “Taylor & Walton” up to 1842, then predominantly used the form “Taylor and Walton” thereafter. ↩︎

-

20

Randall C. Merris, “Carlo Minasi, Composer, Arranger and Teacher”, Papers of the International Concertina Association 6 (2009): 17–45 (page 42, n. 9 list of Minasi’s addresses in Camden). ↩︎

-

21

Taylor & Walton’s list dated August 1842, found at the end of Justus Freiherr von Liebig, Animal Chemistry, or Organic Chemistry in its Applications to Physiology and Pathology (London: Taylor and Walton, 1842). Keats is still listed in March 1847, in Taylor & Walton’s list found at the end of Justus Freiherr von Liebig, Researches on the Chemistry of Food (London: Taylor and Walton, 1847). ↩︎

-

22

Bindings so described are found among Taylor & Walton’s publications in the Wellcome Collection, London. The label of Remnant and Edmonds is usually on the end pastedown. On the firm, see James Secord, Victorian Sensation: The Extraordinary Publication, Reception, and Secret Authorship of Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2003), 120. ↩︎

-

23

His letterpress printers include: Mills and Son, Gough-Square, Fleet-Street; Mills, Jowett and Mills, Bolt-Court, Fleet-Street; James Moyes, Castle Street, Leicester Square; Samuel Bentley, Dorset Street, Fleet-Street; Samuel Bentley, Bangor House, Shoe Lane; Bradbury and Evans, Whitefriars; J.L. Cox and Sons, printers to the Honourable East India Company, 75, Great Queen Street, Lincoln’s-Inn Fields; A. Spottiswoode, New-Street Square; S. & J. Bentley, Wilson and Fley, Bangor House, Shoe Lane; John Wertheimer & Co., Circus Place, Finsbury Circus; Mitchell, Heaton and Mitchell, printers, Liverpool; Neill and Company, Old Fishmarket, Edinburgh; and Schulze and Co., 13 Poland-Street, London. ↩︎

-

24

Thomas Bagg (also called “Mr Bagg senior”) was his usual wood engraver, cutting designs that William Bagg had drawn on the wood or on paper: both of them were based at 8 Hart Street (since the 1930s called Bloomsbury Way), leading westwards off the south-west corner of Bloomsbury Square. Jones Quain, Elements of Anatomy, 4th ed. (London: Taylor & Walton, 1837), vi (“The drawings are due to the pencil of Mr William Bagg … the engraving has been conducted with great care by Mr Bagg sen.” [i.e. Thomas Bagg]). They are listed at 8 Hart Street in the Post Office London Street Directory (1841), 119 and 633. On Hart Street, see F. Peter Woodford, ed., Streets of Bloomsbury & Fitzrovia (London: Camden History Society, 1997), 76 and 84. ↩︎

-

25

For steel engravings, Taylor normally employed Henry Adlard, and occasionally Charles Wass. Work by both Adlard and Wass is found in Johannes Müller, Elements of Physiology, translated from the German, with notes, by William Baly (London: Taylor and Walton, 1838–1842) (and in many other publications). ↩︎

-

26

Michael Twyman, Lithography, 1800–1850: The Techniques of Drawing on Stone in England and France and Their Application in Works of Topography (London: Oxford University Press, 1970). ↩︎

-

27

Michael Twyman, “Charles Joseph Hullmandel: Lithographic Printer Extraordinary”, in Lasting Impressions: Lithography as Art, ed. Pat Gilmour (London: Alexandria Press, 1988), 44–90 and 362–367. ↩︎

-

28

These included George Johann Scharf, William Fairland, and W. Walton. Scharf was a Bavarian who resided in a side road off Gower Street and worked mainly for scientific publishers; see Twyman, “Charles Joseph Hullmandel”, 64–65 and 86. William Fairland had illustrated, at the age of nineteen, a privately published work on artistic anatomy, George Simpson’s The Anatomy of the Bones and Muscles: Exhibiting the Parts as They Appear on Dissection, and More Particularly in the Living Figure; as Applicable to the Fine Arts. Designed for the Use of Artists, and Members of the Artist’s Anatomical Society. … Illustrated with Highly-Finished Lithographic Impressions (London 1825). On Walton, both Taylor and Hullmandel employed an artist called W. Walton, who drew on stone drawings of Shropshire required by Hullmandel for publication as lithographs. Hullmandel also employed for the same purpose, and at the same period, an artist who signed as W.L Walton: he was very prolific and drew many different types of lithographs. It is unknown whether these were the same or different people, and if they were they connected with Hullmandel’s business partner, Joseph Fowell Walton of Sarratt Hall, Rickmansworth, Hertfordshire. The preface to the first volume of The Principles and Practice of Obstetric Medicine credits Mr W. Fairland and “M. Rue of Mr Hullmandel’s establishment”, who presumably oversaw the printing of the lithographs. ↩︎

-

29

At the age of sixteen, Wilson had met Jones Quain while Wilson was a student surgeon, and he became assistant to Jones Quain and later Richard Quain in the anatomy school at UCL. In 1836, he had briefly run his own anatomy school at 22 Sussex Street (behind University College Hospital), and in 1840 became lecturer in anatomy at the Middlesex Hospital in Fitzrovia. His residence in Fitzrovia was at 55 Upper Charlotte Street, near the Maclise brothers. D’Arcy Power and G.L. Asherson, “Wilson, Sir (William James) Erasmus (1809–1884), Dermatologist and Philanthropist”, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 23 September 2004. ↩︎

-

30

Robert Harrison, The Surgical Anatomy of the Arteries of the Human Body, 2nd ed. (Dublin: Hodges & Smith, 1829), xi–xii ↩︎

-

31

George Viner Ellis, Demonstrations of Anatomy. ↩︎

-

32

British and Foreign Medical Review 11, January 1841, 211. ↩︎

-

33

Richard Quain, The Anatomy of the Arteries of the Human Body, octavo volume (London: Taylor & Walton, 1844), vi. ↩︎

-

34

John Lindley, Elements of Botany, Structural, Physiological, Systematical, and Medical (London: Printed for Taylor and Walton, 1841), advertisements at the end in some copies, dated November 1842. ↩︎

-

35

H. Bence Jones, On Gravel, Calculus & Gout. ↩︎

-

36

Justus Freiherr von Liebig, Animal Chemistry, or Chemistry in its Applications to Physiology and Pathology (London: Printed for Taylor and Walton, 1843), advertisements at end in some copies. ↩︎

-

37

Edward W. Murphy, Lectures on Natural and Difficult Parturition (London: Printed for Taylor and Walton, 1845), advertisements at the end of Wellcome Collection copy no. 38050/B/1, dated October 1846. ↩︎

-

38

Edward W. Murphy, Lectures on Natural and Difficult Parturition (London: Printed for Taylor and Walton, 1845), advertisements at the end of Wellcome Collection copy no. 38050/B/2, dated November 1847. ↩︎

-

39

William Senhouse Kirkes, Hand-Book of Physiology (London: Taylor, Walton & Maberly, 1848), advertisements at the end of some copies. ↩︎

-

40

Edward Turner, Elements of Chemistry, Including the Actual State and Prevalent Doctrines of the Science, 8th ed. (London: Printed for Taylor and Walton, 1847), contains the publisher’s advertisements for “New works printed for Taylor Walton & Maberly” including “Maclise’s morphological studies in search of the archetype skeleton of vertebrated animals”. William Smith, Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology (London: Taylor & Walton and John Murray, 1844–1849) advertises on 1 March 1848 “New works printed for Taylor & Walton” including Maclise’s Comparative Osteology and “Mr Quain’s work on the arteries”—Maclise still receives no credit for his earlier work. The same advertisements were included in some copies of Justus Freiherr von Liebig, Researches on the Motion of the Juices in the Animal Body (London: Printed for Taylor and Walton, 1848). ↩︎

-

41

P.W.J. Bartrip, “Churchill, John Spriggs Morss (1801–1875), Medical Publisher”, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 23 September 2004. ↩︎

Bibliography

Bartrip, P.W.J. “Churchill, John Spriggs Morss (1801–1875), Medical Publisher”. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 23 September 2004.

Bence Jones, H. On Gravel, Calculus & Gout: Chiefly an Application of Professor Liebig’s Physiology to the Prevention and Cure of these Diseases. London: Printed for Taylor and Walton, 1842.

Bynum, W.F. and Porter, R. eds. William Hunter and the Eighteenth-Century Medical World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985.

Chilcott, T. A Publisher and His Circle: The Life and Work of John Taylor, Keats’s Publisher. London: Routledge, 1972.

Collins, Dr. Practical Rules for the Management and Medical Treatment of Negro Slaves, in the Sugar Colonies, by a Professional Planter. London: Vernor & Hood, 1803.

Combrune, M. The Theory and Practice of Brewing. London: Vernor & Hood, 1804.

Darling, G. Instructions for Making Unfermented Bread: With Observations on its Properties, Medicinal and Economic. London: Taylor & Walton, 1847.

Davis. D.D. The Principles and Practice of Obstetric Medicine. London: Taylor & Walton, 1832.

De Morgan, A. The Connexion of Number and Magnitude: An Attempt to Explain the Fifth Book of Euclid. London: Taylor and Walton, 1836.

Ellis, G.V. Demonstrations of Anatomy: Being a Guide to the Dissection of the Human Body. London: Taylor and Walton, 1840.

Fuchs, L. De historia stirpium. Basel: Isingrin, 1542.

Füssel, S. Hartmann Schedel, Chronicle of the World: The Complete and Annotated Nuremberg Chronicle of 1493. Cologne: Taschen, 2001.

Harrison, R. The Surgical Anatomy of the Arteries of the Human Body, 2nd ed. Dublin: Hodges & Smith, 1829.

Howard Roberts, J.R. and Godfrey, W.H. eds. “Fitzroy Street”. In Survey of London: Volume 21, The Parish of St Pancras Part 3: Tottenham Court Road and Neighbourhood. London, 1949, 44–46. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol21/pt3/pp44-46

Kirkes, W.S. Hand-Book of Physiology. London: Taylor, Walton & Maberly, 1848.

Kirwan, R. The Manures Most Advantageously Applicable to the Various Sorts of Soils, and the Causes of Their Beneficial Effect in Each Particular Instance. London: Vernor & Hood, 1804.

Kusukawa, S. Picturing the Book of Nature: Image, Text, and Argument in Sixteenth-Century Human Anatomy and Medical Botany. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2012.

Lindley, J. Elements of Botany, Structural, Physiological, Systematical, and Medical. London: Taylor and Walton, 1841.

Merris, R.C. (2009) “Carlo Minasi, Composer, Arranger and Teacher”. Papers of the International Concertina Association 6: 17–45.

Morison, S. Printing and the Mind of Man; Catalogue of Exhibitions at the British Museum and at Earls Court, London: 16–27 July 1963. London: F.W. Bridges & Sons, 1963.

Müller, J. Elements of Physiology. Translated from the German, with notes, by William Baly. London: Taylor and Walton, 1838–1842.

Murphy, E.W. Lectures on Natural and Difficult Parturition. London: Taylor and Walton, 1845.

O’Malley, C.D. Andreas Vesalius of Brussels. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1964.

Power, D’A. and Asherson, G.L. “Wilson, Sir (William James) Erasmus (1809–1884), Dermatologist and Philanthropist”. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 23 September 2004.

Quain, R. The Anatomy of the Arteries of the Human Body and its Application to Pathology and Operative Surgery, octavo volume. London: Taylor & Walton, 1844.

Quain, J. Elements of Anatomy, 4th ed. London: Taylor & Walton, 1837.

Reske, C. Die produktion der Schedelschen Weltchronik in Nürnberg. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2000.

Schedel, H. Nuremberg Chronicle. Nuremberg: A. Koberger, 1493.

Secord, J.A. Victorian Sensation: The Extraordinary Publication, Reception, and Secret Authorship of Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2003.

Simpson, G. The Anatomy of the Bones and Muscles: Exhibiting the Parts as They Appear on Dissection, and More Particularly in the Living Figure; as Applicable to the Fine Arts. Designed for the Use of Artists, and Members of the Artist’s Anatomical Society. … Illustrated with Highly-Finished Lithographic Impressions. London, 1825.

Smith, W. Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. London: Taylor & Walton and John Murray, 1844–1849.

Turner, E. Elements of Chemistry, Including the Actual State and Prevalent Doctrines of the Science, 8th ed. London: Taylor and Walton, 1847.

Twyman, M. “Charles Joseph Hullmandel: Lithographic Printer Extraordinary”. In Pat Gilmour (ed) Lasting Impressions: Lithography as Art. London: Alexandria Press, 1988.

Twyman, M. Lithography, 1800–1850: The Techniques of Drawing on Stone in England and France and Their Application in Works of Topography. London: Oxford University Press, 1970.

Vesalius, A. De humani corporis fabrica. Basel: J. Oporinus, 1543.

von Liebig, J,F. Animal Chemistry, or Organic Chemistry in its Applications to Physiology and Pathology. London: Taylor and Walton, 1842.

von Liebig, J.F. On Artificial Manures. London: Taylor & Walton, 1845.

von Liebig, J.F. Researches on the Chemistry of Food. London: Taylor and Walton, 1847.

von Liebig, J.F. Researches on the Motion of the Juices in the Animal Body. London: Taylor and Walton, 1848.

Woodford, F.P, ed. Streets of Bloomsbury & Fitzrovia. London: Camden History Society, 1997.

Imprint

| Author | |

|---|---|

| Date | 18 July 2021 |

| Category | One Object |

| Review status | Peer Reviewed (Double Blind) |

| License | Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) |

| Downloads | PDF format |

| Article DOI | https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-20/wschupbach |

| Cite as | Schupbach, William. “Joseph Maclise, Taylor & Walton, and Publishing on Gower Street in the 1840s.” In British Art Studies. London and New Haven: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art and Yale Center for British Art, 2021. https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-20/wschupbach. |