In the Flesh at the Heart of Empire

In the Flesh at the Heart of Empire: Life-Likeness in Wax Representations of the 1762 Cherokee Delegation in London

By Ianna Recco

Abstract

In 1762, a delegation of Cherokee leaders arrived in London for negotiations with King George III following the Anglo-Cherokee War (1759–1761), itself part of the Seven Years’ War (1756–1763). The British public reacted to the men’s presence in London with fervent zeal; throngs of Londoners flocked to the men’s private rooms and any public house, garden, or theatre they attended to see them in person before their very eyes. This article asks why the delegation became such a spectacle by studying three wax statues that were made in the image of the men and were exhibited at Mrs. Salmon’s Royal Wax-Work in London from 1762 to approximately 1793, after which they were lost to history. In questioning how the life-likeness of the wax statues was achieved through materiality and visual elements, and analysing contemporary accounts of the London public’s reception of the men, it emerges that the statues worked to retain their subjects as objects of spectacle long after they returned to North America. Due to the low aesthetic status and fragility of wax statuary, the medium has received little art-historical attention despite the significance of the art form in eighteenth-century London. This article seeks to address this oversight and bring new insight to the imperial visual culture of eighteenth-century Britain.

“A New Press of the Cherokee King, with his Two Chiefs”

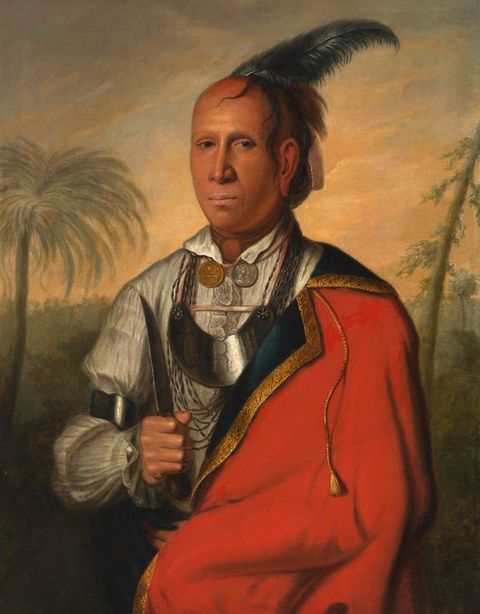

In 1762, a “new press” of wax statues was unveiled at Mrs. Salmon’s Royal Wax-Work at 189 Fleet Street in London. In the eighteenth century, the terms “press” and “presses” were commonly used to describe wax statues, most likely in reference to the physical process of creating them in which wax was poured into a mould and an exact impression, or cast, was made.1 According to the handbill, this particular ensemble consisted of typical subjects for an eighteenth-century British waxwork such as members of the royal family and Mark Antony and Cleopatra, but one group stands out in the announcement, that of “a new Press of the Cherokee King, with his two chiefs, in their Country Dress, and Habilments [sic]”.2 Although their names are omitted, we know that the “Cherokee King” refers to Utsidihi, an asgayagusta, or military leader, with “his two chiefs” referring to Kunagadoga and Atawayi, all of whom ruled alongside the Tennessee River in the southeast region of North America at that time.3

1Although seemingly far removed from a London audience, visitors to Mrs. Salmon’s waxwork would have instantly recognised these wax statues with their dark skin, plucked scalps, and red cloaks as representations of the three men who made up the Cherokee delegation that toured London from 16 June to 25 August 1762. They received an enormous amount of attention from the British public and press, and their likenesses were captured and disseminated in a range of British visual and performative media.4 Despite the fact that these men were significant players in North American politics during the Seven Years’ War (1756–1763) and the British press demonstrated a vested interest in Cherokee military and political affairs, primary sources make clear that Utsidihi, Kunagadoga, and Atawayi were reduced to objects of spectacle in London. They attracted crowds that would surround them in public venues, cram into their living spaces to watch them dress, and flock to public houses to watch them eat and drink. I use the term “spectacle” here and throughout the article in the sense that Utsidihi, Kunagadoga, and Atawayi were turned into curiosities by the British public, which, in large part, negated the men’s status as emissaries and their diplomatic mission. The term’s connotations of display and exhibition are of particular relevance as are its performative and theatrical aspects.5 What emerges from the archive is that the specific goal of the London masses was to see the men in the flesh before their very eyes. The effect of this aggressive scrutiny was an objectification that largely disregarded, and even neutralised, the significant political and military power that the Cherokee wielded in North America.

4Representing Life-likeness

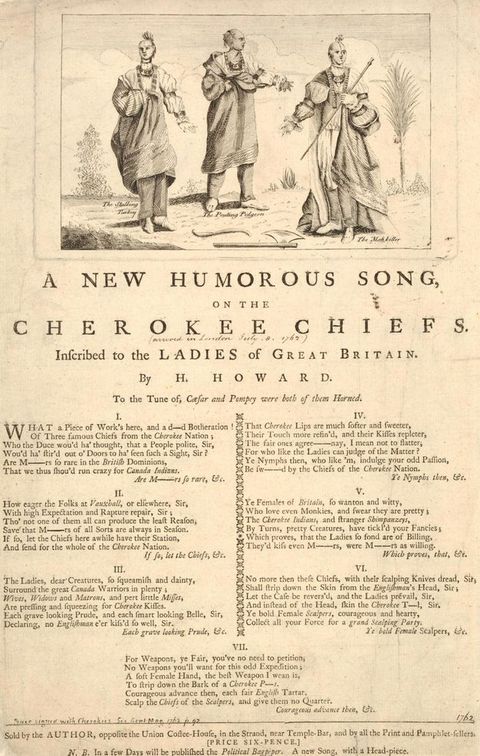

The emphasis on spectacle that characterised the British public’s reaction in 1762 is reflected in the wide variety of images of the delegation in a range of media. The artworks that have survived in the largest number are the engravings and mezzotints done after paintings and studies of the men, their countenances, adornments, and facial tattoos incised and inked and pressed for individual purchase and magazine publication.6 The two known paintings that survive of the delegation are portraits by Joshua Reynolds and Francis Parsons, depicting Utsidihi and Kunagadoga, respectively, arresting countenances that now sit unseen in storage in the Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa, Oklahoma (figs. 1 and 2). In contrast, there were also less durable representations that have not survived to the present day, their existence only recorded in advertisements and descriptions in British newspapers. Such examples include a popular ballad titled Cherokee Chiefs (fig. 3) as well as a pantomime called Harlequin Cherokee that was regularly performed at Drury Lane in 1763 and depicted “the Return, Landing and Reception of the Cherokees in America”.7 One letter published in the St. James Chronicle relayed that Utsidihi was even rendered as the puppet Punch when a puppeteer “clapping on a Pair of Whiskers upon Punch, blacking his Face, and dressing him in a strange Robe, passed him off through half the Country for the Cherokee King”.8 Apart from one broadside with a ballad, most of these have been lost to time likely due to both their more performative elements and their low rank in the hierarchy of art history. The wax statues exhibited at Mrs. Salmon’s emerge as the most ephemeral representation of Utsidihi, Kunagadoga, and Atawayi. The fact that we have no visual record of them nor any knowledge of where they ended up (or, more likely, of their destruction)—the most probable answer being that they were melted down and formed into new statues—has discouraged any research into them. While an art-historical examination of any of these examples of artwork would allow significant and varied insight into British imperial visual culture of the eighteenth century, the wax statues exhibited at Mrs. Salmon’s will lie at the heart of this analysis to determine the inherent function and significance of “life-likeness” in representations of the 1762 delegation as a physical manifestation of the British public’s relegation of powerful political leaders to objects of spectacle. Although the particular theme of life-likeness is traditionally associated with portraits in the art-historical discipline, an even more fruitful discussion will unfold if we extend the same ideas of life-likeness typically only applied to painted portraits to sculpted wax portraits. While Reynolds’s and Parsons’s portraits of the 1762 delegation served to memorialise and preserve the diplomats for posterity through life-like representations in a medium accorded aesthetic legitimacy, the wax statues were constructed to sustain British engagement with, and perpetuate the otherness of, inaccessible foreign peoples. By transcribing the men within such a life-like mode of British visualisation, the wax statues can be understood as the ultimate art objects of empire in the sense that they mimetically froze their Indigenous North American subjects as objects of spectacle stripped of their agency and political power in the heart of the British empire for decades.9

6

Life-Likeness in Art History

In his examination of the “phenomenon of loss” in material culture, Glenn Adamson describes how lost objects suffer a double loss, one of survival to the present day as well as a lack of representation in the historical record.10 Both ideas are true for the wax statues discussed in this analysis. Eighteenth-century British wax statues have largely been pushed to the periphery of art-historical study because, as Roberta Panzanelli and Uta Kornmeier determined, scholars consider them “disreputable” subjects that are regarded as “old-fashioned popular entertainments without any internal logic”.11 The seminal work that remains the most influential analysis is Julius von Schlosser’s “History of Portraiture in Wax”, published in 1911.12 No significant work in this field had then been undertaken until 2008, when Ephemeral Bodies: Wax Sculpture and the Human Figure, edited by Roberta Panzanelli, was published. In it, she wrote that this lack of scholarship has only been exacerbated by the dearth of Early Modern wax statues that have survived over time; to her, the history of wax statues is essentially “a history of disappearance”.13 Histories of disappearance, Adamson remarks, can be especially confounding when the objects that have been lost were once popular and commonplace at a particular moment in time, as wax statuary was in mid-eighteenth-century London.14 For these particular objects, their disappearance is further dramatised because wax statuary was a medium that strove to achieve material presence and existence and, as a result, life-likeness was, and remains, the defining trait of the medium.

10“Life-likeness” as a term emerged from studies of the use of ad vivum in the visual culture of the Early Modern period as an assertion of the verisimilitude of an art object. While the tradition of inscribing “ad vivum” directly onto artworks flourished in Europe in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, it waned in the eighteenth century, making space for other articulations of life-likeness in European visual culture that conveyed the same ideas.15 Daston and Galison also identify the terms “after life” and “drawn from nature” in addition to “ad vivum” as artistic and scientific claims commonly made in the Early Modern period, particularly on botanical drawings.16 Significantly for this study, another function of ad vivum was to verbally substantiate a representation of unfamiliar non-European beings or foreign places.17

15The principles of “ad vivum”, “after life”, and “drawn from nature” can be applied in the present examination of objects produced in mid-eighteenth-century London as cognates appear in advertisements for prints derived from Reynolds’s and Parsons’s paintings of Utsidihi and Kunagadoga that emphasised they were done “from the Life” and “after the Life”.18 These terms all work to not only “[preach] fidelity to nature” but also to articulate what is life-like or vivacious in a visual representation.19 A crucial connotation of these terms is that the image it describes is lively and animate, in the same sense that a viewer might say that a painted figure is following them with its eyes or that a statue looks alive.20 In this sense, the term “life-likeness” is an appropriate one for this study as it has been established as a useful translation of ad vivum in recent art-historical research and relates directly to eighteenth-century descriptions of painted representations of Utsidihi and Kunagadoga, with “life” being the essential component of the term.

18Life-likeness, however, is a cultural construct that has different connotations in an Indigenous context. Considering modern Cherokee conceptualisations of art, contemporary artist America Meredith also looks towards linguistic practice and encourages the examination of Indigenous vocabulary in forming theory. Meredith explains that the Cherokee word for “art” is “ᏗᏟᎶᏍᏙᏗ”, or ditlilosdodi, and signifies creating an imitation of reality.21 The suffix “ᏗᏟᎶᏛ-”, ditlil, appears in many words, including “ᏗᏟᎶᏍᏔᏅ”, or “ditlilostanv”, meaning “artificial”, “copy”, “duplicate”, and “imitation”. The word for artist is “ᏗᏟᎶᏍᏔᏅᏍᎩ”, or ditlilostanvsgi, and the verb for “to copy” is “ᏗᏟᎶᏍᏔᏅᎯ”, or ditlilostanvhi. Taking this into consideration, we can further establish that “life-likeness” is a relevant theme given this connotation of an artificial imitation or duplication of reality. In addition, the Cherokee term that members historically refer to themselves as is “Aniyunwiya” or “ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯ”, which translates to the “Principal People” or “Real People”. For Utsidihi, Kunagadoga, and Atawayi, whose individualism and agency were effectively swallowed by the British public during their time in London, affirming them as “Real People” reminds us of the living, breathing men who were transmuted into inanimate and illusory material representations and were largely erased from history.22

21The “Real People” in North America

The years from 1759 to 1761 were marred by warfare between the British and Cherokee during the conflict that came to be known by the British as the Anglo-Cherokee War. This occurred against the larger backdrop of the global Seven Years’ War (1756–1763). Despite waging war against the Cherokee people over trade and sovereignty conflicts, British army officers were quick to negotiate compromises once the military and diplomatic prowess of the Cherokee became apparent and, in 1761, the Holston River treaty ended the fighting that had spanned across South Carolina, Georgia, North Carolina, and Virginia.23 As eighteenth-century newspaper reports demonstrate, the British were acutely aware of the Cherokee’s power, around which there was a palpable anxiety. This unease is apparent in a report published in the London Evening Post in July 1762, when the delegation was already in London, that reads, “The Cherokees are the most considerable Indian Nation with which we are acquainted, and are absolutely free; [The] strength of an Indian nation consists in their warriors and of these, according to the best accounts, there may be about three thousand amongst the Cherokees”.24 The pervasive fear of French encroachment compounded this apprehension and also loomed large in the press. Again, concurrent to when the delegation was already in London, a report from South Carolina was published in the London Evening Post that stated, “The French make their advantage of [the British inability to take Louisiana], and say we are not the warriors we pretend; and I wish their arts may not at length prevail to make them disturb us, in which case we should be in an infinitely worse situation than in a Cherokee war”.25

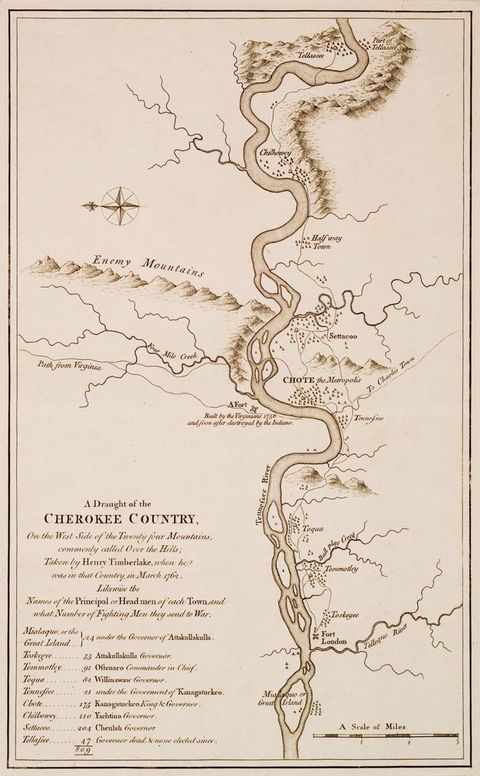

23Historians have been able to reconstruct this period further using the trove of official correspondence and reports from British governors, officers, and colonial assemblies.26 The memoir published in 1765 by Henry Timberlake, the ensign who accompanied Utsidihi, Kunagadoga, and Atawayi to London, provides key information about the 1762 delegation. Timberlake had a previous relationship with the men, having met them when Utsidihi and Kunagadoga insisted that a representative of the British military appear at Chota, the principal town, to mark the peace treaty; Timberlake volunteered and acted as a diplomat himself, while fostering a relationship with Utsidihi in particular.27 Timberlake’s memoir, titled The Memoirs of Lieut. Henry Timberlake: (who accompanied the three Cherokee Indians to England in the year 1762); containing whatever he observed remarkable, or worthy of public notice, during his travels to and from that nation; wherein the country, government, genius, and customs of the inhabitants, are authentically described; also the principal occurrences during their residence in London; illustrated with an accurate map of their Over-Hill settlement, and a curious secret journal, taken by the Indians out of the pocket of a Frenchman they had killed, begins in “Cherokee Country”, where he establishes the basis of his narrative before the scene turns to London across the Atlantic. On first opening the book, the reader is met with a folded map, which unfurled, reveals a detailed illustration of Cherokee territory and a register of the principal leaders in the region, introducing us to Utsidihi and Kunagadoga as important figures (fig. 4). Timberlake’s writing can be characterised as ethnographic in nature as he discusses the breadth of Cherokee cultural and political practices with the distinct voice of an outsider. Despite the limitations that his account presents, in lieu of a direct account from Utsidihi, Kunagadoga, and Atawayi, Timberlake’s memoir provides valuable information for understanding the ways in which such literary productions conditioned the perception of the delegation in North America and their time in London. Moreover, Timberlake’s text provides a vital connection between seeing Utsidihi, Kunagadoga, and Atawayi in their local context, and how the attention of curious onlookers rendered them “foreign” upon their arrival in London.

26

Unlike previous delegations of North American Indigenous representatives to London, most notably the 1710 Haudenosaunee delegation, the 1762 delegation had neither been invited by King George III to London, nor had it been authorised by the Cherokee council at Chota.28 John Oliphant hypothesises that the delegation sought to meet with the king in part to symbolically acknowledge the newly ratified alliance between the British and the Cherokee, but also so Utsidihi could bolster his standing within his own nation and lay the groundwork for establishing Virginia as a trade centre.29 In fact, while the men were in London, the Gazetteer and London Daily Advertiser speculated that Utsidihi’s political ambition and jealousy of another Cherokee leader, Attakullakulla or Little Carpenter, was the reason for his visit: “The cause of the Cherokee Chiefs coming to England having been variously, but not truly represented, it may not be amiss to inform the public, through the channel of your paper, of what were their real motives for visiting our court and kingdom. […] A jealousy of this particular honour paid to Attakullakulla has prompted [Utsidihi] to come to England, imagining that the Little Carpenter owes all his power and influence to his having visited King George”.30 While we cannot know if this is historical fact, what is more noteworthy is the emphasis given in this report on the delegation’s “real motives”. This illustrates what Troy Bickham identifies as a shift in the British imagination over the eighteenth century to an increased appetite for “the reality of things” and topicality following the Seven Years’ War when imperial issues took precedence over European ones.31 Sadiah Qureshi, in Peoples on Parade, identifies this same topicality in nineteenth-century newspapers advertising exhibitions of foreign peoples in London as a means to generate public interest and spectatorship.32 The Seven Years’ War brought imperial matters to the forefront of British consciousness in what Bickham calls an “increasingly imperial, globally minded society that shared assumptions about alien cultures”.33 These assumptions were only magnified once Utsidihi, Kunagadoga, Atawayi, Timberlake, Thomas Sumter, a soldier in the Virginia militia, and William Shorey, an interpreter, sailed for London on 15 May 1762.34

28The “Real People” in London

The delegation’s time in London is well recorded as a result of the intense attention they garnered in contemporary newspapers. What emerges from the archive is that Utsidihi, Kunagadoga, and Atawayi, all of whom were high-ranking and distinguished leaders, were reduced to objects of display and spectacle during their time in London. It is only with this archival analysis that we can proceed to our material analysis, that of the wax statues that maintained a life-like image of the men once they had departed London and were no longer available to the public as living spectacles.

The delegation landed in Plymouth, England, on 16 June 1762 and immediately became a major focal point of the British public. Timberlake wrote of the moment saying their ship “drew a vast crowd of boats, filled with spectators […] and the landing-place was so thronged, that it was almost impossible to get to the inn”.35 Utsidihi, Kunagadoga, and Atawayi’s “foreignness” was an immediate draw for the London public: “The uncommon appearance of the Cherokees began to draw after them great crowds of people of all ranks”.36 From the moment they disembarked, Utsidihi, Kunagadoga, and Atawayi became a regular fixture in the local newspapers, which reported on their dress, habits, interactions with the public, and their itinerary, and, as seen earlier, the events of the Seven Years’ War and Cherokee politics. The intense interest in the men that the press generated included reports on their itinerary and whereabouts throughout their entire visit, and advertisements of their presence were included on playbills, play-house doors, public gardens, and public houses among other spaces, underscoring their status as spectacles for the British public to come and watch.37 It is useful to keep in mind the parallel between these advertisements of their location and the announcement of the “new press” of wax statues at Mrs. Salmon’s Royal Wax-Work; both the men and representations of them were announced to the public to garner attention and to attract an audience. On their very arrival, the specifics of their accommodations were published: both the Public Advertiser and the St. James’s Chronicle announced that: “A House is taken in Suffolk-street […] for the three Cherokee Indian Chiefs”, on 24 June 1762.38

35Prior to the delegation’s arrival, a model existed of foreign peoples exhibited in London since the fifteenth century, which subsequently informed the “human displays” that proliferated in the nineteenth century as a form of popular entertainment and helped to fuel the racist hierarchies propagated in the scientific discourse of the period.39 In the nineteenth century, foreign peoples, including other Indigenous peoples like Inuit and Anishinaabe, were exhibited in theatres, museums, galleries, and private apartments to satiate the curiosity of viewers, feeding into an Enlightenment system of knowledge.40 As in the case of the 1762 delegation, printed materials were essential in advertising these exhibitions as evidenced by posters, playbills, handbills, and newspaper advertisements and reviews.41 In fact, Qureshi identifies that the performer’s ethnic origins were featured the most prominently in promotional materials, with the location of the exhibition commonly following, as in our eighteenth-century account.42

39Turning to Timberlake’s text, it is evident that Utsidihi, Kunagadoga, and Atawayi were wary of the unwanted attention they received during their transformation into objects of spectacle. Only a few days into their visit, Timberlake wrote of the discomfort that arose within the men given the intense and overwhelming scrutiny they faced at their residence, “at which they were so much displeased, that home became irksome to them”.43 Timberlake and Charles Wyndham, the Secretary of State for the Southern Department, attempted to restrict the number of spectators, only to have the opposite effect, making more people eager to see them. In a telling account, Timberlake writes that despite the restrictions, “[members of the public] pressed into the Indians’ dressing room, which gave them the highest disgust, these people having a particular aversion to being stared at while dressing or eating” to the effect that “they were so disgusted, that they grew extremely shy of being seen”.44 This was echoed in the London Chronicle and the London Evening Post which relayed, “they are shy of company, especially a crowd, by whom they avoid being seen as much as possible”.45 The intense scrutiny they were under is especially clear in the British public’s desire to see them perform daily, and personal, activities as if they were performers to be watched on a stage or objects on display.46 The unwillingness and discomfort of the men with their new status as objects of spectacle are palpable in these accounts, particularly as staring is in direct opposition to Cherokee cultural sensibilities. Timberlake wrote early in his memoir in a general description of the Cherokee people that “they seldom turn their eyes on the person they speak of, or address themselves to, and are always suspicious when people’s eyes are fixed upon them”.47 In fact, Jim Hornbuckle and Laurence French write in The Cherokee Perspective that “avoidance of eye and body contact … when conversing with others” is historically a significant Cherokee cultural behaviour that has survived to the present day.48

43Nonetheless, there was a performative dimension to the delegation’s presence in London. Utsidihi, Kunagadoga, and Atawayi apparently even made public appearances to satiate the public and dissuade them from intruding on their accommodation on Suffolk Street. In one instance, the Public Advertiser announced that the men would be at a horse show at the Star and Garter in Chelsea on 17 July 1762, the advertisement for which stated, “they intend to be present, and will indulge the Company with their Appearance upon the Green for a sufficient Time to satisfy the Curiosity of the Public, in hopes that they may receive the Politeness from the Populate, in their Retirement to the Apartment appointed for them”.49 Here we see that not only was their presence at this performance advertised, but their role as objects of spectacle was made clear by the statement of their purpose to “satisfy the curiosity of the public”. For these reasons, they became as much a performance as the shows they were attending. As seen in this example, in exchange for their presence, Utsidihi, Kunagadoga, and Atawayi hoped to find reprieve from the overwhelming attention, or as Timberlake wrote, the “ungovernable curiosity of the people”.50 It is in these advertisements that the eighteenth-century construct of a British “Public” and “Populate” as an imagined entity is made especially clear.

49Others sought to monetise and exploit the display of the delegation, pointing to the ways in which the scopic regimes of knowledge in the eighteenth century went hand in hand with the monetisation of a “foreign” spectacle. There exists an account from the perspective of a public house owner planning to “exhibit” the men to stimulate business published in the 30 July 1762 edition of the Gazetteer and London Daily Advertiser. The author describes how another man, the owner of the Dwarf Tavern, “has got money by showing the Cherokees at his house”, and so he went “to see in what manner they were exhibited there”. The words “showing” and “exhibited” alone delineate the status of the men as spectacle, and, in further evidence of this, the tavern had a sign affixed to its door that read, “This day the King of the Cherokees and his two chiefs drink tea here”, similar to an advertisement one might find outside of a theatre. The author of the account relayed that over the course of the day, several hundred spectators came to see Utsidihi, Kunagadoga, and Atawayi, who, “if their looks or behaviour may be believed, [were there] not from their own choice”, yet another example of their discomfort at the attention. To amplify the connotations of an exhibition or performance, the author reported that the men were encircled by a rail to separate them from the spectators. For his own display, the author revealed that he had railed off a corner of his tap room, placed a chair for “the King”, meaning Utsidihi, in the centre of it, and hired a man to shout from the door “Walk in gentlemen, see 'em alive!”51 The spaces of exhibition examined here (the men’s apartment, dressing room, the Star and Garter, and the Dwarf Tavern) are all comparable to spaces identified by Qureshi as “sites in which social and political orders, often amenable to imperialism, were created or endorsed”.52 These examples illustrate Qureshi’s assertion that displayed people largely were reduced to “consumable commodities” through this process of exhibition and spectacle.53 In effect, the British public demeaned and dehumanised Utsidihi, Kunagadoga, and Atawayi and effectively erased their identities as principal leaders of a complex political and cultural system. This can even be seen in the terminology of “King” used so frequently by the British press to describe Utsidihi although his status as an asgayagusta is one of great cultural specificity. A July 1762 report admits this saying, “so that when we call any of their Chiefs Princes or Kings, it is to accommodate their manners to our ideas”.54

51On a broader level, the intense public scrutiny of the delegation also fed into a symbolic desire for imperial conquest of the Americas. As discussed earlier, reports concurrent to the men’s time in London describe the Cherokee as “the most considerable Indian Nation” known to the British.55 This anxiety is explicitly expressed in a report published in the London Daily Advertiser prior to the men’s departure from London: “In a few days the Cherokee Chiefs, with their King (as he is called) will leave this nation, the climate not being found to agree with them. This departure, while they are in good health, is prudent, for if any of them should die here, Indian jealousy would suspect they had been poisoned or murdered here, and in the case probably bring on a cruel and revengeful war”.56 It is apparent that the British perceived the Cherokee to be a very real threat to their imperial expansion and thus feared their retaliation. By objectifying and stripping Utsidihi, Kunagadoga, and Atawayi of their agency while they were in London, the British public was momentarily able to symbolically control a politically independent people whose power in North America was viewed with apprehension and unease.

55Life-Likeness in Wax Statuary

Utsidihi and Kunagadoga sat for their portraits by Reynolds and Parsons, respectively, in June and July, and afterwards they remained in London for one month and continued to be subject to intense scrutiny.57 While it likely was intended more as societal commentary on British mores, some contemporary observers verbalised their distaste for the spectators’ actions in the newspapers.58 The best example of this is in the St. James’s Chronicle of August 1762 in an anonymous letter to Henry Baldwin, the printer of the paper, which criticised the manner in which Utsidihi “was exposed to publick View as a Monster” and a “strange Sight”, who was brought over merely “to be stared at”. The author denounced the “English Curiosity [that] is easily imposed upon” and said, “Our Nation is remarkable for its Greediness after Novelty, which requires continually to be fed with fresh Matter”.59 After the delegation sailed from London on 24 August 1762, Utsidihi, Kunagadoga, and Atawayi left a void in the London public scene. In the absence of the public spectacle that they generated in person, London indeed needed “fresh matter” to feed the public’s “greediness for novelty”, and it would come in the form of the wax statues exhibited at Mrs. Salmon’s.

57A multitude of London guides and visitors’ diaries illustrate that Mrs. Salmon’s Royal Waxwork was founded by a Mr. Salmon in the late seventeenth century and passed through several owners and locations before it closed in the mid-nineteenth century, one of its last mentions being in Charles Dickens’s David Copperfield in 1850.60 Primary sources illustrate the popularity of Mrs. Salmon’s among audiences across the social spectrum. The Daily Advertiser in 1776 wrote of the “inimitable” establishment, “This is one of those capital Exhibitions which no Person of Taste ever visits this Metropolis without seeing”.61 The Morning Herald in 1785 wrote of “The great number of the fashionable world, who every day resort to Mrs. Salmon’s Royal Waxwork”.62 Mrs. Salmon’s even moved from Aldersgate to Fleet Street near St. Dunstan’s church in 1711, where it “was more convenient for the quality’s coaches to stand unmolested”, to attract a wealthy clientele.63 In eighteenth-century Britain, wax statues were a way to convey an authentic likeness of persons who were otherwise inaccessible.64 To many, the statues at Mrs. Salmon’s were the next best thing to seeing an individual in person. This is especially true in the case of Utsidihi, Kunagadoga, and Atawayi, whom many Londoners may have only briefly caught sight of, if at all. In contrast to the rarer opportunities of encountering them in person, material exhibitions provided the British public with “sustained opportunities” of engagement.65 These “sustained opportunities”, as opposed to single observed moments, were an essential part of knowledge production in this period, particularly in achieving and capturing “truth-to-nature”.66 As such, in its guarantee for sustained opportunities and unique material and virtual engagements with the men, Mrs. Salmon’s emerged as a significant exhibition space for the British public to seek entertainment and continue the objectification of Utsidihi, Kunagadoga, and Atawayi.67

60Despite their popularity across social classes, wax statues were not accepted in academy circles as works of art. In 1768, the Royal Academy of Arts prohibited the exhibition of wax statues like those in the fashion of the “Cherokee King” in their Abstract of the Constitution and the Laws. It stated: “no … models in coloured wax, or any such performance, nor any Work of Art which has been publicly exhibited elsewhere for emolument, shall be admitted into the Exhibition of the Royal Academy”.68 Small wax medallions and busts, like those by Catherine Andras, were however accepted within the mode of portraiture.69 The Society of Artists of Great Britain and the Free Society of Artists accepted wax models and portraits, and many were exhibited in the 1760s and 1770s, including those done in coloured wax, but these too were only on a small scale, were framed, were not free-standing, and did not incorporate glass eyes and human hair.70 Alison Yarrington states that these restrictions were to prevent any affiliation with the popular entertainment form of waxworks.71 It is unsurprising that the Royal Academy restricted the exhibition of wax statues as Joshua Reynolds, the President of the Royal Academy from 1768 to 1792, despised them for their exact replication of nature. Reynolds’s Eleventh Discourse (1782) reads, “To express protuberance by actual relief, to express the softness of flesh by the softness of wax, seems rude and inartificial, and creates no grateful surprise. But to express distances on a plain surface, softness by hard bodies, and particular colouring by materials which are not singly of that colour produces that magic which is the prize and triumph of art”.72 These sentiments were not just held by Reynolds but were reflected in contemporary literature. A poem, published in the Whitehall Evening Post in 1790 by the Earl of Carlisle to mark Reynolds’s resignation as President of the Royal Academy, praises the “nobler art” of painting compared to “waxwork figures [that] always shock the sight/too near to human flesh and shape, affright/and when they best are form’d afford the least delight”.73 Wax’s ability to resemble flesh too accurately and its overly illusionistic life-likeness were the reasons it was deemed unworthy of academic exhibition.

68However, the very life-likeness condemned by art theorists like Reynolds was precisely why Mrs. Salmon’s was the most famous waxwork of its time; the skill of their rendering and the degree of life-likeness were irresistible. Mrs. Salmon’s was one of the best examples of waxworks of the eighteenth century and was a predecessor to Madame Tussaud’s better-known waxworks.74 The 1782 London Guide begins its description of Mrs. Salmon’s with the telling line, “the figures are modelled in wax, many of them so just a resemblance of Nature, that if they were seen in any other place, and unexpectedly, they might be easily mistaken for the works of Nature”.75 A similar account appeared in an advertisement for a moving statue at Mrs. Salmon’s in a 1710 edition of the Tatler that read “Nothing but life can exceed the motions of the heads, hands, eyes, &c., of these figures”, perhaps referring to wax statues that were not just realistic in appearance but also in mechanised movement.76 The glass eyes of wax sculptures in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries may have been mechanically set to occasionally glance at the viewer.77 In fact, the flourishing of eighteenth-century wax statuary falls within what has been called the “period of the automaton craze”, when there was significant public interest in moving and speaking anthropomorphic automata throughout Europe that achieved corporeal mimicry through impressive mechanisms.78 In her analysis of biomorphic automata in the eighteenth century, Bianca Westermann determines that these mechanical figures lay “at the intersection of artificial and animate, of dead matter and lifelike behaviour”, much as the wax statues at Mrs. Salmon’s did, mechanised or not.79

74In these examples referencing “life” and “nature”, we see a departure from the more straightforward ad vivum, or “from life”, paradigm that was used to describe Reynolds’s and Parsons’s portraits. The wax statues cross the line that separates representational art objects from living organisms, or “the works of Nature”.80 Such a degree of trompe l’oeil can produce an unavoidable sensory impression that can mislead the eye.81 This is a phenomenon that Kornmeier has termed “the waxwork moment”, which she defines as the time it takes a viewer to realise that a wax statue is an object and not a real person or the moment when an image reveals its artificiality.82 This doubt is illustrated in an advertisement of a waxwork exhibition in the 1780s where “[the statues’] countenances and attitudes are so expressive and animated, that they seem ready to address each other”.83 Quite simply, according to a 1784 visitor to Mrs. Salmon’s, “you thought they were alive”.84

80Wax statues created a bridge between representation and reality that had been “removed by time or space”.85 This effectively promoted the viewer “from the beholder of an image to an eyewitness”, just as the quality of ad vivum might have compensated for the unfamiliarity or inaccessibility of a subject.86 Exhibitions of Indigenous North American objects in the eighteenth century had a similar function. The British Museum and the Leverian collection, which opened in 1753 and 1773, respectively, displayed significant collections of objects taken from North America from drums and tomahawks to wampum and clothing. Visitors to the Leverian were especially impressed with the “reality” of the ethnographic display, as seen in the 1782 issue of the European Magazine which reads, “all conspire to impress the mind with a conviction of the reality of things”.87 Bickham writes that these objects were displayed to engage audiences with “geographically distant peoples and places that the increasingly imperial-minded Britons perceived as relevant”.88

85

When the “Cherokee” wax statues were made, Mrs. Salmon’s business was in the hands of a surgeon-solicitor named Mr. Clarke, who took over following the death of Mrs. Salmon in 1760.89 As the statues did not survive to the present day and there is scarce imagery of contemporary wax statues, we must use primary sources to reconstruct what they may have looked like and how they were exhibited (fig. 5). Given the seemingly high level of artistry at Mrs. Salmon’s that was praised by visitors, the statues would have likely been made of high-quality beeswax imported from the Ottoman territories, which was guaranteed to allow for a quick and easy whitening process.90 Before the wax could be poured, a mould of the sitter’s face had to be made. If possible, this would be done from life with plaster. For example, Mrs. Salmon made likenesses from “Dead faces” upon request and likely made these casts from life.91 As there is no mention of Utsidihi, Kunagadoga, and Atawayi undergoing such a sitting, it is much more likely that their wax statues were based on a mould produced from a pre-made cast, which is how the majority of contemporary wax statues were made. This is consistent with a visitor’s description in 1783 that “all busts seemed similar to us”.92 The heated wax would then be poured into the mould, and once set, the perfect wax impression would be extracted.93 In addition to the head, the forearms and hands would also be made from a mould.94 The question arises that if the wax sculptor used a pre-made cast, did they account for specific features like the men’s elongated earlobes? This would have been possible as the sculptor could make subtle revisions after the wax face was cast, but perhaps it was a neglected detail as creating a “true-to-nature” image was, in fact, a highly mediated and selective process where the unusual or singular was largely excluded in favour of perceived generality and commonality.95

89A significant step in the creation of the statues would have been the application of oil paint to create an accurate skin tone. In the broader tradition of ad vivum, skin colour was an essential part in bringing an image to life.96 Oil paint was likely used for the same reasons that portrait painters favoured it, namely, that it could be layered and had a life-like luminous quality. Utsidihi, Kunagadoga, and Atawayi’s “copper” skin became a main focus of the British public and was described repeatedly in the press, and a visitor’s diary entry in 1793 mentions the skin of the statues being rendered in a “copper” colour.97 Their tattoos and face paint were also likely added at this stage, in addition to illusionistic veining and pigment spots.98 These visual elements would have been key in establishing the effective illusion of vitality that was expected of waxworks.99

96The natural properties of wax allow the medium to absorb light and blur contours, which have the effect of creating an illusion of movement when viewed from different angles. Not only does the translucence of wax resemble human skin, but its form can sag and deform over time much like human skin itself.100 Wax also has the appearance of being soft to the touch and has a silken and glossy texture.101 The illusionism created by the medium would have made the skin of the statues of Utsidihi, Kunagadoga, and Atawayi devoid of abstraction.102 Once the heads were painted, real hair, glass eyes, and teeth would have been fitted into the statues, likely imitating the men’s true appearances including their specific hairstyles.103 As the sculptor would only use wax to form the visible anatomy of the statue like the head, neck, forearms, and hands, the body would be constructed of a wooden frame and then covered in clothing.104 We also know, according to the handbill referenced at the beginning of this article, that the statues were clothed “in their Country Dress, and Habilments [sic]”.105 The men supposedly gave their own clothes to be used for the display, but as their characteristic white shirts and red cloaks were made in London, they could have been specially made for the waxwork.106 These would have served to transport the audience to an inaccessible setting.107 Qureshi also notes that, for displays of foreign people in the nineteenth century, accurate ethnic clothing was highly significant and that spectators appeared to be especially concerned with the “authenticity” of performers.108 It is the combination of all these persuasive visual effects that establishes a notion of vitality while simultaneously suppressing the mediations required to create the life-like objects.109

100Once the statues were made, they took their place among the two hundred other statues at Mrs. Salmon’s. After paying a shilling for admission, visitors were received by a woman who provided a short description of the statues as well as descriptive handbills.110 Many statues were exhibited theatrically in active poses rather than formal studio poses and were dramatised by strategic lighting.111 It seems that by 1783, the delegation’s trio was reduced to just two figures.112 According to a companion book, “A Cherokee king, with his chief”, was exhibited in the first of five rooms. The same room included the mythological figure of Andromeda chained to a rock, a literary scene from Macbeth, and the biblical scene of Susanna and the elders.113 In picturing this arrangement, the statues of Utsidihi and either Kunagadoga or Atawayi stood among literary, mythological, and biblical characters that were far more familiar and less foreign to the British public. This is a noteworthy juxtaposition that parallels Bickham’s analysis of contemporary exhibitions at the British Museum and the Leverian that not only displayed Indigenous North American objects, but also juxtaposed them with European objects to demonstrate, as Bickham determines, the conviction of “British cultural and technological superiority”.114 This adverse contextualising of Indigenous objects next to British and European objects included placing drums next to European instruments, bows and arrows next to swords, and tomahawks next to firearms, which worked to visually establish an Indigenous otherness.115 Mrs. Salmon’s similarly sought to fabricate difference with the juxtaposition of familiar European figures with those of foreign people, and the public conformed to this imperial mentality, as seen in the diary entry of a visitor in 1793 describing his memory of a childhood visit to Mrs. Salmon’s: “I was then quite a youth, and the hideous copper countenance of the chiefs, […] contrasting so frightfully with the sweaty death-like faces of the principle figures, riveted the scene so firmly on my memory”.116 Despite the prestige and power that defined Utsidihi, Kunagadoga, and Atawayi as principal leaders from the Overhill towns, this reception to their wax countenances is a sharp distinction from the function of sixteenth-century wax votives that Panzanelli writes “were meant to inspire ‘first devotion, then reverence and veneration’ for the great men represented there”.117 The last mention of the statues was in 1793, after which they faded from history.118

110Conclusion

We have no evidence that Utsidihi, Kunagadoga, and Atawayi saw their wax statues or were at any point involved with their creation as they were for the sittings of their painted portraits. However, European portraits were present in North America, functioning as successful tools for mediating colonial and imperial relationships, particularly in representing physically absent individuals.119 The Cherokee people also had a cultural tradition of portraiture themselves as seen in the Mississippian period AD 800–1650, in which they rendered elite human figures in copper plates and marble statues, which they carved and painted naturalistically (figs. 6 and 7).120 But what would Utsidihi, Kunagadoga, and Atawayi have made of the statues of themselves? Would their wax representations have interested the men? Or would it have been off-putting to see such uncanny representations of themselves, frozen in a room among other curious figures?

119

The moment that the wax statues were completed, they became outdated representations as their subjects continued to age and change in North America.121At Mrs. Salmon’s, however, they were frozen in time and in form, in what Dustin Wax calls “a dead state”.122 This idea is reflective of the original function of wax statuary for funerary purposes as well as the colour of unpainted wax that resembles dead, not living, flesh.123 This applies to both the wax statues at Mrs. Salmon’s and the most recognisable representations of the men, Joshua Reynolds’s and Francis Parsons’s portraits of Utsidihi and Kunagadoga. In both media, the subjects are trapped in their own representations. The life-likeness inherent to the media encourages viewers to expect that someone, or some internal life, will always be behind the image.124 The portraits of Utsidihi and Kunagadoga, meanwhile, have survived and sit in storage, protected from the effects of time. If the statues of Utsidihi, Kunagadoga, and Atawayi were indeed melted down into other figures at the end of the century, they likely were transformed into more topical and relevant characters, and perhaps European subjects at that.

121Acknowledgements

I would like to first thank Tim Nuttle, Tim Orr, TommyLee Whitlock, and Sarah Orndorff for the creation of their valuable resource, the Cherokee–English Dictionary Online Database https://www.cherokeedictionary.net/. This article was developed as a dissertation during my graduate studies at the Courtauld Institute of Art, and I am particularly grateful for the guidance of Dr. Esther Chadwick. In addition, I would like to thank the editorial team at British Art Studies, and finally, to Simon Jia, for his steadfast support.

About the author

-

Ianna Recco is a curatorial assistant at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Asian Art. She received her MA from the Courtauld Institute of Art with a specialisation in circum-Atlantic visual culture, circa 1770–1830 and her BA from Hamilton College in Art History and Classical Languages.

Footnotes

-

1

For additional contemporary usage of the terminology, see “Advertisements and Notices”, Gazetteer and New Daily Advertiser, 10 June 1767, Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/Z2000358293/BBCN?u=cioa&sid=BBCN&xid=4822bb2a. ↩︎

-

2

Richard D. Altick, The Shows of London (Cambridge, MA: Belknap, 1978), 53; Troy Bickham, “‘A Conviction of the Reality of Things’: Material Culture, North American Indians and Empire in Eighteenth-Century Britain”, Eighteenth-Century Studies 39, no. 1 (2005): 30, www.jstor.org/stable/30053587; and Maurice W. Disher, Pleasures of London (London: Hale, 1950), 200. ↩︎

-

3

Coll Thrush, Indigenous London: Native Travelers at the Heart of Empire (New Haven, CT: Yale University, 2016), 70. While today there are 400,000 registered Cherokee Nation citizens, Tyler Boulware cautions against applying a nation framework to eighteenth-century Cherokees as it presents an oversimplified homogeneity and unity to a broad and diverse people who identified themselves primarily by town and regional affiliations. See Tyler Boulware, Deconstructing the Cherokee Nation: Town, Region, and Nation among Eighteenth-Century Cherokees (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2011). ↩︎

-

4

Henry Timberlake, The Memoirs of Lieut. Henry Timberlake: (who accompanied the three Cherokee Indians to England in the year 1762); containing whatever he observed remarkable, or worthy of public notice, during his travels to and from that nation; wherein the country, government, genius, and customs of the inhabitants, are authentically described; also the principal occurrences during their residence in London; illustrated with an accurate map of their Over-Hill settlement, and a curious secret journal, taken by the Indians out of the pocket of a Frenchman they had killed (London: J. Ridley, 1765), 116 and 129. ↩︎

-

5

The term has been established by other scholars in the field of Indigenous North American visitors to London including Kate Fullagar in The Savage Visit: New World People and Popular Imperial Culture in Britain, 1710–1795 (Berkeley, CA: University of California, 2012); and Jocelyn Hackforth-Jones, David Bindman, Romita Rayet, and Stephanie Pratt in Between Worlds: Voyagers to Britain, 1700–1850 (London: National Portrait Gallery, 2007). In addition, the term is used in many scholarly analyses of wax statuary including Uta Kornmeier’s essay “Almost Alive: The Spectacle of Verisimilitude in Madame Tussaud’s Waxworks”, in Ephemeral Bodies: Wax Sculpture and the Human Figure, ed. Roberta Panzanelli (Los Angeles, CA: Getty Research Institute, 2008), 67–81; and by Altick in The Shows of London. ↩︎

-

6

An entire discussion could be had about the relationship between engraving and tattooing in the case of the 1762 Cherokee delegation. For an analysis of the physical parallel between European engravings and Indigenous tattooing customs, see Michael Gaudio’s discussion of Theodor de Bry’s engravings of tattooed Algonquin people in “Savage Marks: The Scriptive Techniques of Early Modern Ethnography”, in Engraving the Savage: The New World and Techniques of Civilization (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, 2008), 1–44. ↩︎

-

7

“Advertisements and Notices”, Public Advertiser, 11 November 1762, Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/Z2001087090/BBCN?u=cioa&sid=BBCN&xid=114cbc83; and “Advertisements and Notices”, Gazetteer and London Daily Advertiser, 10 May 1763, Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/Z2000342044/BBCN?u=cioa&sid=BBCN&xid=b79bc3ae. ↩︎

-

8

“News”, St. James’s Chronicle, 5–7 August 1762, Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/Z2001255714/BBCN?u=cioa&sid=BBCN&xid=e64cd150. ↩︎

-

9

Bickham, “‘A Conviction of the Reality of Things’”, 36 and 41. ↩︎

-

10

Glenn Adamson, “The Case of the Missing Footstool: Reading the Absent Object”, in History and Material Culture, ed. Karen Harvey (London: Routledge, 2017), 240. ↩︎

-

11

Uta Kornmeier, “The Famous and the Infamous: Waxworks as Retailers of Renown”, International Journal of Cultural Studies 11, no. 3 (2008): 280, DOI:10.1177/1367877908092585; and Roberta Panzanelli, ed., Ephemeral Bodies: Wax Sculpture and the Human Figure (Los Angeles, CA: Getty Research Institute, 2008), 1. ↩︎

-

12

Julius von Schlosser, “History of Portraiture in Wax”, in Ephemeral Bodies: Wax Sculpture and the Human Figure, ed. Roberta Panzanelli (Los Angeles, CA: Getty Research Institute, 2008), 171–303; Aby Warburg’s seminal essay on wax effigies in the fifteenth-century Renaissance portraiture tradition has also been a key discussion in the use of wax. See Aby Warburg, “Bildniskunst und Florentinisches Bürgertum”, in Die Erneuerung der heidnischen Antike: kulturwissenschaftliche Beiträge zur Geschichte der europäischen Renaissance, Gesammelte Schriften, ed. Gertrud Bing, in association with Fritz Rougemont (Leipzig: B.G. Teubner, 1932). ↩︎

-

13

Panzanelli, Ephemeral Bodies, 1. ↩︎

-

14

Adamson, “The Case of the Missing Footstool”, 243. ↩︎

-

15

Thomas Balfe, Joanna Woodall, and Claus Zittel, eds., Ad Vivum? Visual Materials and the Vocabulary of Life-Likeness in Europe before 1800 (Leiden: Brill, 2019), 3. ↩︎

-

16

Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison, “Truth-to-Nature”, in Objectivity (New York: Zone, 2007), 98. ↩︎

-

17

Balfe, Woodall, and Zittel, Ad Vivum, 5. ↩︎

-

18

“Advertisements and Notices”, Public Advertiser, 30 July 1762, Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/Z2001085751/BBCN?u=cioa&sid=BBCN&xid=4a780571; and Thomas Mortimer, The Universal Director; or, The nobleman and gentleman’s true guide to the masters and professors of the liberal and polite arts and sciences; and of the mechanic arts, manufactures, and trades, established in London and Westminster, and their environs (London: J. Coote, 1763), 21. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/U0101202820/MOME?u=ull_ttda&sid=MOME&xid=09b664f2. ↩︎

-

19

Balfe, Woodall, and Zittel, Ad Vivum, 2, 4, and 5; and Daston and Galison, “Truth-to-Nature”, 104. ↩︎

-

20

Balfe, Woodall, and Zittel, Ad Vivum, 10. ↩︎

-

21

America Meredith, “Cultivating Vocabulary: An Ongoing Process”, Ahalenia, 30 September 2012, http://ahalenia.blogspot.com/2012/09/; the Cherokee syllabary ᏣᎳᎩ ᎦᏬᏂᎯᏍᏗ, or Tsalagi Gawonihisdi, was invented by the Cherokee linguist Sequoyah in 1821. It was adopted by the tribe within five years and has remained in use ever since. ↩︎

-

22

Jim Hornbuckle and French Laurence, eds., The Cherokee Perspective: Written by Eastern Cherokees (Boone, NC: Appalachian State University, 1981), 3. ↩︎

-

23

Mark H. Danley and Patrick J. Speelman, eds., The Seven Years’ War: Global Views (Leiden: Brill, 2012), 325; Stan Hoig, The Cherokees and Their Chiefs: In the Wake of Empire (Fayetteville, AR: University of Arkansas, 1998), 45; and John Oliphant, “The Cherokee Embassy to London, 1762”, The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 27, no. 1 (1999): 1, DOI:10.1080/03086539908583045. ↩︎

-

24

“News”, London Evening Post, 3–6 July 1762, Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection, https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?p=BBCN&u=cioa&id=GALE%7CZ2000667146&v=2.1&it=r&sid=BBCN&asid=a3987ebf. ↩︎

-

25

“News”, London Evening Post, 19–21 August 1762, Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection, https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?p=BBCN&u=cioa&id=GALE%7CZ2000667425&v=2.1&it=r&sid=BBCN&asid=fff6607f. ↩︎

-

26

John Oliphant, Peace and War on the Anglo-Cherokee Frontier, 1756–63 (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2001), xi–xiv. ↩︎

-

27

Timberlake, The Memoirs of Lieut. Henry Timberlake, 10, 31, and 35. ↩︎

-

28

Much has been written about the 1710 Haudenosaunee delegation, who were dubbed “The Four Mohawk Kings” by the English, as well as the four portraits of them by Jan Verelst commissioned by Queen Anne. On the portraits, see Kevin R. Muller, “From Palace to Longhouse: Portraits of the Four Indian Kings in a Transatlantic Context”, American Art 22, no. 3 (2008): 26–49, DOI:10.1086/595806. For a discussion on performance and display in the Haudenosaunee visit to London, see Joseph Roach, Cities of the Dead (New York: Columbia University, 1996). ↩︎

-

29

Oliphant, “The Cherokee Embassy to London, 1762”, 1–2. ↩︎

-

30

“News”, Gazetteer and London Daily Advertiser, 7 August 1762, Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection, https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?p=BBCN&u=cioa&id=GALE%7CZ2000340323&v=2.1&it=r&sid=BBCN&asid=0e5233c1. ↩︎

-

31

Bickham, “A Conviction of the Reality of Things”, 29–30; See Troy Bickham, Savages within the Empire: Representations of American Indians in Eighteenth-Century Britain (Oxford: Clarendon, 2006); and Fullagar, The Savage Visit. ↩︎

-

32

Sadiah Qureshi, Peoples on Parade: Exhibitions, Empire, and Anthropology in Nineteenth-Century Britain (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2011), 66 and 68. ↩︎

-

33

Bickham, “A Conviction of the Reality of Things”, 31. ↩︎

-

34

Oliphant, “The Cherokee Embassy to London, 1762”, 8. ↩︎

-

35

Timberlake, The Memoirs of Lieut. Henry Timberlake, 115. ↩︎

-

36

Timberlake, The Memoirs of Lieut. Henry Timberlake, 117. ↩︎

-

37

“News”, St. James’s Chronicle or the British Evening Post, 5–7 August 1762. ↩︎

-

38

“Business”, St. James’s Chronicle or the British Evening Post, 22–24 June 1762, Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/Z2001255493/BBCN?u=cioa&sid=BBCN&xid=4991f781; and “News”, Public Advertiser, 24 June 1762, Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/Z2001085329/BBCN?u=cioa&sid=BBCN&xid=8bcc11ce. ↩︎

-

39

Qureshi, Peoples on Parade, 2. ↩︎

-

40

Qureshi, Peoples on Parade, 2 and 8. ↩︎

-

41

Qureshi, Peoples on Parade, 47 and 49. ↩︎

-

42

Qureshi, Peoples on Parade, 60. ↩︎

-

43

Fullagar, The Savage Visit, 118; and Timberlake, The Memoirs of Lieut. Henry Timberlake, 117. ↩︎

-

44

Timberlake, The Memoirs of Lieut. Henry Timberlake, 123. ↩︎

-

45

“News”, London Chronicle, 19–22 June 1762, Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/Z2001677284/BBCN?u=cioa&sid=BBCN&xid=004075d1; and “News”, London Evening Post, 19–22 June 1762, Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/Z2000667073/BBCN?u=cioa&sid=BBCN&xid=63734509. ↩︎

-

46

These accounts closely mirror the attention that previous delegations from North America experienced, especially the 1710 Haudenosaunee delegation in London. A central focus of Joseph Roach’s study is the account of the Haudenosaunee men attending a showing of Macbeth at the Queen’s Theatre and being seated on stage so the public could watch them as they, in turn, watched the actors; see Roach, Cities of the Dead. ↩︎

-

47

Timberlake, The Memoirs of Lieut. Henry Timberlake, 55. ↩︎

-

48

Hornbuckle and French, The Cherokee Perspective, 12. ↩︎

-

49

“Advertisements and Notices”, Public Advertiser, 17 July 1762, Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/Z2001085598/BBCN?u=cioa&sid=BBCN&xid=ff1b2530. ↩︎

-

50

Timberlake, The Memoirs of Lieut. Henry Timberlake, 118. ↩︎

-

51

“News”, Lloyd’s Evening Post, 26–28 July 1762, Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/Z2000553435/BBCN?u=cioa&sid=BBCN&xid=9e8659f5; and “Arts and Culture”, Gazetteer and London Daily Advertiser, 30 July 1762, Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/Z2000340265/BBCN?u=cioa&sid=BBCN&xid=7d81e82b. For a parallel historical moment of the British public going to see exhibited North American Indigenous people, see Jessica L. Horton “Ojibwa Tableaux Vivants: George Catlin, Robert Houle, and Transcultural Materialism”, Art History 39, no. 1 (February 2016): 124–151, DOI:10.1111/1467-8365.12184. ↩︎

-

52

Qureshi, Peoples on Parade, 8. ↩︎

-

53

Qureshi, Peoples on Parade, 48. ↩︎

-

54

“News”, London Evening Post, 3–6 July 1762. ↩︎

-

55

“News”, London Evening Post, 3–6 July 1762. ↩︎

-

56

“News”, Gazetteer and London Daily Advertiser, 29 July 1762, Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection, https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?p=BBCN&u=cioa&id=GALE%7CZ2000340251&v=2.1&it=r&sid=BBCN&asid=e320bc56. ↩︎

-

57

Fullagar, The Savage Visit, 108; “News”, Lloyd’s Evening Post, 28–30 July 1762; “News”, London Evening Post, 27–29 July 1762, Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/Z2000667290/BBCN?u=cioa&sid=BBCN&xid=3d40576b; “News”, St. James’s Chronicle or the British Evening Post, 27–29 July 1762, Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/Z2001255672/BBCN?u=cioa&sid=BBCN&xid=f5f42ab5; Marcia Pointon, Hanging the Head: Portraiture and Social Formation in Eighteenth-Century England (New Haven, CT: Yale University, 1998), 48; and Sarah Erwin et al., Treasures of Gilcrease: Selections from the Permanent Collection (Tulsa, OK: Gilcrease Museum, 2005), 29. The only concrete mention of Utsidihi’s sitting in Reynolds’s sitter-book that I found, as did Kate Fullagar, is on 1 June 1762. The Gilcrease Museum, however, has published that there were three separate sittings for this portrait, a fact that they likely garnered from archival documents beyond the sitter-book. ↩︎

-

58

This could in fact be part of a larger satirical literary tradition of fictionalising Indigenous North American voices to level a critique against contemporary British society. This has been discussed in terms of the 1710 Haudenosaunee delegation in Hackforth-Jones et al., Between Worlds. ↩︎

-

59

“News”, St. James’s Chronicle or the British Evening Post, 5–7 August 1762. ↩︎

-

60

Altick, The Shows of London, 54; and Bickham, “‘A Conviction of the Reality of Things’”, 30. ↩︎

-

61

“News”, Daily Advertiser, 14 June 1776, Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/Z2000159197/BBCN?u=cioa&sid=BBCN&xid=1cd1baab. ↩︎

-

62

“News”, Morning Herald, 21 June 1785, Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/Z2000920037/BBCN?u=cioa&sid=BBCN&xid=90076eaf. ↩︎

-

63

Uta Kornmeier, Taken from Life: Madame Tussaud and the History of the Wax Museum from the 17th to the Early 20th Centuries (Berlin: Humboldt University, 2003), 183. ↩︎

-

64

Panzanelli, Ephemeral Bodies, 67. ↩︎

-

65

Bickham, “‘A Conviction of the Reality of Things’”, 29 and 31. ↩︎

-

66

Daston and Galison, “Truth-to-Nature”, 59. ↩︎

-

67

Bickham, “‘A Conviction of the Reality of Things’”, 29 and 31. ↩︎

-

68

Royal Academy of Arts, Abstract of the Constitution and the Laws of the Royal Academy of Arts in London, established December 10, 1768 (London: B. McMillan, 1815), 42. ↩︎

-

69

Alison Yarrington, “Art in the Dark: Viewing and Exhibiting Sculpture at Somerset House”, in Art on the Line: The Royal Academy Exhibitions at Somerset House 1780–1836, ed. David H. Solkin (New Haven, CT: Paul Mellon Centre, 2001), 174. ↩︎

-

70

Algernon Graves, The Society of Artists of Great Britain 1760–1791, The Free Society of Arts 1761–1783: A Complete Dictionary of Contributors and Their Work from the Foundation of the Societies to 1791 (London: George Bell and Sons, 1907), 103. ↩︎

-

71

Yarrington, “Art in the Dark”, 174. ↩︎

-

72

Joshua Reynolds, “The Eleventh Discourse”, in The Discourses of Sir Joshua Reynolds, ed. John Burnet (London: James Carpenter, 1842), 188. In 1776, Reynolds added a clause to his theory to allow for the contradictive state that portraiture existed within. He said that artists could include “single features” if they were “innocent” like Utsidihi’s ochre facial markings, which were superficial enough to not threaten the ideal of universal refinement and did not detract from the general humanity of the figure. ↩︎

-

73

“Arts and Culture”, Whitehall Evening Post, 13–15 April 1790, Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/Z2001628986/BBCN?u=cioa&sid=BBCN&xid=aafe6581. ↩︎

-

74

Uta Kornmeier, “Madame Tussaud’s as a Popular Pantheon”, in Pantheons: Transformations of a Monumental Idea, ed. Matthew Craske and Richard Wrigley (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2004), 154–155. ↩︎

-

75

The London Guide: Describing the Public and Private Buildings of London, Westminster, & Southwark (London: Printed for J. Fielding, 1782[?]), The Making of the Modern World, 116, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/U0107784531/MOME?u=ull_ttda&sid=MOME&xid=21b14e15. ↩︎

-

76

M.C. Barres-Baker, An Introduction to the Early History of Newspaper Advertising (London: Brent Museum, 2006). ↩︎

-

77

Kornmeier, “Madame Tussaud’s as a Popular Pantheon”, 150–151; and Kornmeier, Taken from Life, 28. ↩︎

-

78

Minsoo Kang, Sublime Dreams of Living Machines (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2011), 174–175; and Bianca Westermann, “The Biomorphic Automata of the 18th Century: Mechanical Artworks as Objects of Technical Fascination and Epistemological Exhibition”, Figurationen 17, no. 2 (2016): 125 and 131. ↩︎

-

79

Westermann, “The Biomorphic Automata of the 18th Century”, 133. ↩︎

-

80

Panzanelli, Ephemeral Bodies, 67–68. ↩︎

-

81

Panzanelli, Ephemeral Bodies, 67–68. ↩︎

-

82

Panzanelli, Ephemeral Bodies, 67. ↩︎

-

83

“Advertisements and Notices”, The World, 3 June 1788, Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/Z2001505241/BBCN?u=cioa&sid=BBCN&xid=0467a12e. ↩︎

-

84

Kornmeier, Taken from Life, 230. ↩︎

-

85

Lucia Dacome, Malleable Anatomies: Models, Makers, and Material Culture in Eighteenth-Century Italy (Oxford: Oxford University, 2017), 7. ↩︎

-

86

Balfe, Woodall, and Zittel, Ad Vivum, 6; and Panzanelli, Ephemeral Bodies, 74. ↩︎

-

87

Bickham, “‘A Conviction of the Reality of Things’”, 32, and 35–36. ↩︎

-

88

Bickham, “‘A Conviction of the Reality of Things’”, 31–32. ↩︎

-

89

Altick, The Shows of London, 53. ↩︎

-

90

Dacome, Malleable Anatomies, 6–7. In the British use of Ottoman wax to create a representation of North American Indigenous people, we see an example of the complex entanglement of power, people, materials, and art that is inherent to the idea and execution of empire. ↩︎

-

91

Hanneke Grootenboer, “Introduction: On the Substance of Wax”, Oxford Art Journal 36, no. 1 (2013): 17. ↩︎

-

92

Kornmeier, Taken from Life, 230. ↩︎

-

93

Kornmeier, Taken from Life, 63. ↩︎

-

94

Kornmeier, Taken from Life, 63. ↩︎

-

95

Daston and Galison, “Truth-to-Nature”, 60. ↩︎

-

96

Balfe, Woodall, and Zittel, Ad Vivum, 10. For an art-historical analysis of skin and flesh tones, see Mechthild Fend, Fleshing Out Surfaces: Skin in French Art and Medicine, 1650–1850 (Manchester: Manchester University, 2016). ↩︎

-

97

Altick, The Shows of London, 53; and Bickham, Savages within the Empire, 33. ↩︎

-

98

Kornmeier, Taken from Life, 30. ↩︎

-

99

Balfe, Woodall, and Zittel, Ad Vivum, 4. ↩︎

-

100

Kornmeier, “Madame Tussaud’s as a Popular Pantheon”, 149–150. ↩︎

-

101

Dacome, Malleable Anatomies, 6. ↩︎

-

102

Kornmeier, “Madame Tussaud’s as a Popular Pantheon”, 151. ↩︎

-

103

Kornmeier, Taken from Life, 63. ↩︎

-

104

Kornmeier, Taken from Life, 61. ↩︎

-

105

Altick, The Shows of London, 53; Bickham, “‘A Conviction of the Reality of Things’”, 30; and Disher, Pleasures of London, 200. ↩︎

-

106

Stephen Foster, British North America in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries (Oxford: Oxford University, 2013). ↩︎

-

107

Bickham, “‘A Conviction of the Reality of Things’”, 30. ↩︎

-

108

Qureshi, Peoples on Parade, 119 and 166. ↩︎

-

109

Balfe, Woodall, and Zittel, Ad Vivum, 5. ↩︎

-

110

The London Guide, 116. ↩︎

-

111

Altick, The Shows of London, 52; and Kornmeier, Taken from Life, 80. ↩︎

-

112

A Companion to All the Principal Places of Curiosity and Entertainment in and about London and Westminster (London: J. Drew, 1801), 87–89. ↩︎

-

113

A Companion to All the Principal Places of Curiosity and Entertainment in and about London and Westminster, 94–96. ↩︎

-

114

Bickham, “‘A Conviction of the Reality of Things’”, 36. ↩︎

-

115

Bickham, “‘A Conviction of the Reality of Things’”, 37. ↩︎

-

116

Altick, The Shows of London, 53; and Bickham, Savages within the Empire, 33. ↩︎

-

117

Panzanelli, Ephemeral Bodies, 15. ↩︎

-

118

Bickham, Savages within the Empire, 33. ↩︎

-

119

Muller, "From Palace to Longhouse, 29–30; and Stephanie Pratt, American Indians in British Art, 1700–1840 (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma, 2005), 58. ↩︎

-

120

Richard Drake, A History of Appalachia (Lexington, KT: University Press of Kentucky, 2001), 7; and Susan C. Power, Early Art of the Southeastern Indians: Feathered Serpents & Winged Beings (Athens, GA: University of Georgia, 2004), 67–71 and 84. For one of the most famous examples of this, The Rogan Copper Plates, see Lee Anne Wilson, “A Possible Interpretation of the Southern Cult Bird-Man Figure on Objects from the Southeastern United States, ad 1200 to 1350”, Phoebus 3: A Journal of Art History (1981): 6–18, https://hdl.handle.net/2286/R.A.208472. ↩︎

-

121

Panzanelli, Ephemeral Bodies, 76. ↩︎

-

122

Dustin Wax, “In the Flesh in the Museum: Representations of Indians in American Natural History Museums”, Savage Minds (2006), https://savageminds.org/2006/08/10/in-the-flesh-in-the-museum/. ↩︎

-

123

Wax, “In the Flesh in the Museum”. ↩︎

-

124

Kristina Huneault, I’m Not Myself at All: Women, Art, and Subjectivity in Canada (Montreal: McGill University, 2018), 58. ↩︎

Bibliography

A Companion to All the Principal Places of Curiosity and Entertainment in and about London and Westminster. London: J. Drew, 1801.

Adamson, Glenn. “The Case of the Missing Footstool: Reading the Absent Object”. In History and Material Culture, edited by Karen Harvey, 240–255. London: Routledge, 2017.

Altick, Richard D. The Shows of London. Cambridge, MA: Belknap, 1978.

Anon. “Advertisements and Notices”. Gazetteer and London Daily Advertiser, 10 May 1763. Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/Z2000342044/BBCN?u=cioa&sid=BBCN&xid=b79bc3ae.

Anon. “Advertisements and Notices”. Gazetteer and New Daily Advertiser, 10 June 1767. Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/Z2000358293/BBCN?u=cioa&sid=BBCN&xid=4822bb2a.

Anon. “Advertisements and Notices”. Public Advertiser, 17 July 1762. Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/Z2001085598/BBCN?u=cioa&sid=BBCN&xid=ff1b2530.

Anon. “Advertisements and Notices”. Public Advertiser, 30 July 1762. Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/Z2001085751/BBCN?u=cioa&sid=BBCN&xid=4a780571.

Anon. “Advertisements and Notices”. Public Advertiser, 11 November 1762. Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/Z2001087090/BBCN?u=cioa&sid=BBCN&xid=114cbc83.

Anon. “Advertisements and Notices”. The World, 3 June 1788. Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/Z2001505241/BBCN?u=cioa&sid=BBCN&xid=0467a12e.

Anon. “Arts and Culture”. Gazetteer and London Daily Advertiser, 30 July 1762. Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/Z2000340265/BBCN?u=cioa&sid=BBCN&xid=7d81e82b.

Anon. “Arts and Culture”. Whitehall Evening Post, 13–15 April 1790. Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/Z2001628986/BBCN?u=cioa&sid=BBCN&xid=aafe6581.

Anon. “Business”. St. James’s Chronicle or the British Evening Post, 22–24 June 1762. Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/Z2001255493/BBCN?u=cioa&sid=BBCN&xid=4991f781.

Anon. “News”. Daily Advertiser, 14 June 1776. Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/Z2000159197/BBCN?u=cioa&sid=BBCN&xid=1cd1baab.

Anon. “News”. Gazetteer and London Daily Advertiser, 29 July 1762. Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection. https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?p=BBCN&u=cioa&id=GALE|Z2000340251&v=2.1&it=r&sid=BBCN&asid=e320bc56.

Anon. “News”. Gazetteer and London Daily Advertiser, 7 August 1762. Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection. https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?p=BBCN&u=cioa&id=GALE|Z2000340323&v=2.1&it=r&sid=BBCN&asid=0e5233c1.

Anon. “News”. Lloyd’s Evening Post, 26–28 July 1762. Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/Z2000553435/BBCN?u=cioa&sid=BBCN&xid=9e8659f5.

Anon. “News”. London Chronicle, 19–22 June 1762. Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/Z2001677284/BBCN?u=cioa&sid=BBCN&xid=004075d1.

Anon. “News”. London Evening Post, 19–22 June 1762. Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/Z2000667073/BBCN?u=cioa&sid=BBCN&xid=63734509.

Anon. “News”. London Evening Post, 3–6 July 1762. Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection. https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?p=BBCN&u=cioa&id=GALE|Z2000667146&v=2.1&it=r&sid=BBCN&asid=a3987ebf.

Anon. “News”. London Evening Post, 27–29 July 1762. Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/Z2000667290/BBCN?u=cioa&sid=BBCN&xid=3d40576b.

Anon. “News”. London Evening Post, 19–21 August 1762. Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection. https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?p=BBCN&u=cioa&id=GALE|Z2000667425&v=2.1&it=r&sid=BBCN&asid=fff6607f.

Anon. “News”. Morning Herald, 21 June 1785. Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/Z2000920037/BBCN?u=cioa&sid=BBCN&xid=90076eaf.

Anon. “News”. Public Advertiser, 24 June 1762. Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/Z2001085329/BBCN?u=cioa&sid=BBCN&xid=8bcc11ce.

Anon. “News”. St. James’s Chronicle or the British Evening Post, 27–29 July 1762. Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/Z2001255672/BBCN?u=cioa&sid=BBCN&xid=f5f42ab5.

Anon. “News”. St. James’s Chronicle, 5–7 August 1762. Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/Z2001255714/BBCN?u=cioa&sid=BBCN&xid=e64cd150.

Balfe, Thomas, Joanna Woodall, and Claus Zittel, eds. Ad Vivum? Visual Materials and the Vocabulary of Life-Likeness in Europe before 1800. Leiden: Brill, 2019.

Barres-Baker, M.C. An Introduction to the Early History of Newspaper Advertising. London: Brent Museum, 2006.

Bickham, Troy. “‘A Conviction of the Reality of Things’: Material Culture, North American Indians and Empire in Eighteenth-Century Britain”. Eighteenth-Century Studies 39, no. 1 (2005): 29–47. www.jstor.org/stable/30053587.

Bickham, Troy. Savages within the Empire: Representations of American Indians in Eighteenth-Century Britain. Oxford: Clarendon, 2006.

Boulware, Tyler. Deconstructing the Cherokee Nation: Town, Region, and Nation among Eighteenth-Century Cherokees. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2011.

Cunningham, Colin, and Gillian Perry, eds. Academies, Museums, and Canons of Art. New Haven, CT: Yale University, 1999.

Cushman, Ellen. The Cherokee Syllabary: Writing the People’s Perseverance. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma, 2013.

Dacome, Lucia. Malleable Anatomies: Models, Makers, and Material Culture in Eighteenth-Century Italy. Oxford: Oxford University, 2017.

Danley, Mark H., and Patrick J. Speelman, eds. The Seven Years’ War: Global Views. Leiden: Brill, 2012.