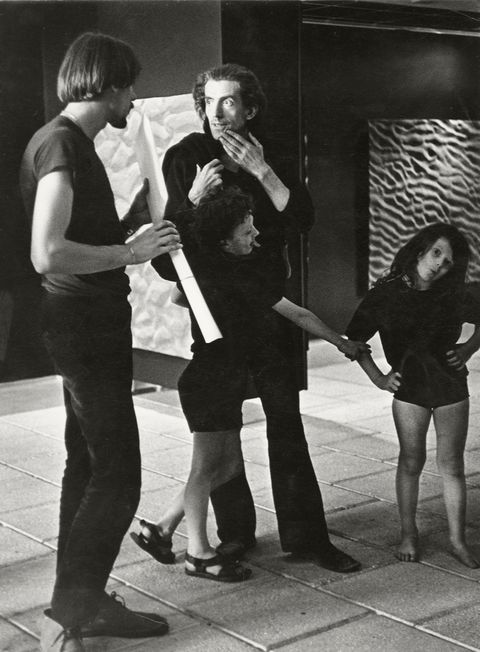

Mark Boyle and Joan Hills at the Gemeentemuseum, The Hague

Mark Boyle and Joan Hills at the Gemeentemuseum, The Hague

By Chris Townsend

Abstract

Boyle Family’s poured resin reliefs, cast from randomly chosen sections of the earth’s surface, problematize the boundaries between sculpture, painting, and performance in British art of the 1960s and 1970s. This essay, discussing the collective’s first international exhibition, at the Gemeentemuseum in The Hague, in turn problematizes the critical nominations that have so far been used to categorize its practice. The essay sees the Boyle Family as operating not in the genres of “earth” or “environmental” art, but rather within the broad category of European conceptualism and the legacies of high modernism, sharing much with the work of Bernd and Hilla Becher in particular.

In May 1970 Mark Boyle (1934–2005) and Joan Hills (b. 1931) were asked by the German curator Hans Locher to stage an exhibition at the Gemeentemuseum, The Hague, in the Netherlands. The Hague project was a radical step both for British sculpture and the artists themselves. It was an almost complete inversion of the social organization, values, and practices that had marked British sculpture until the late 1960s. The exhibition was neither the work of a single artist nor was its content readily definable as “sculpture”. Instead, it was marked by diverse practices of denotation and creation that shared a common thematic in the documentation of environment and society.

Although the Gemeentemuseum show was presented solely under the rubric of Mark Boyle, the accompanying publication made clear it was the work of “Boyle and his colleagues in the Sensual Laboratory, Joan Hills, Des Bonner and Cameron Hills”.1 Indeed, if the project was collective, by 1970 it went further than the corporate operations of the Sensual Laboratory which Boyle had founded with Hills, his partner, and John Claxton in November 1966. For the project was also familial: indeed, in 1970 it was about to become primarily so. Cameron Hills, Joan Hills’s teenage son by her earlier marriage, was joined by the couple’s two younger children, Sebastian (b. 1962) and Georgia (b. 1963). Even in the wake of Fluxus and its challenge to Abstract Expressionism’s romantic myth of the obsessional male artist, collective practice in art was still rare: collective practice whilst at the same time going about the difficult and time-consuming business of raising children, was exceptional; collective practice that involved those children—of pre-school age— in the making of artwork, was so remote from art’s traditions in the modern era that, even when the Boyle Family appellation was established with a modicum of success by the late 1970s, it demanded a continual insistence on its collective identity. Although in the early years of the project, exhibitions and objects were ascribed only to Mark Boyle, they were never less than shared efforts. As Mark Boyle later remarked: “Our primary objective was to make our work. Secondly we wanted to survive. . . . Under these circumstances, if the art world wants to believe in the single, preferably male, obsessed, artist, you don’t quarrel with them.”2

1No one in this group was “a sculptor”: none had received extended training in an art school, none had worked as a studio assistant for an established artist—as had, for example, Anthony Caro, Phillip King, and Denis Mitchell with Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth. Boyle had studied to be a lawyer before joining the army, whilst Hills had briefly enrolled on a painting course, been to an architectural school, and studied structural mechanics. Boyle began writing poetry in the late 1950s: before he shifted his attention to the visual arts he would be published in The Paris Review, one of the leading international literary journals. Hills recalls that by the early 1960s she and Boyle were experimenting widely with collage and assemblage. On the one hand they were making pieces where the material used stood only for itself as object, and on the other using compositional methods where the assemblage carried a greater cultural reference. However, found material from the urban environment gradually supplanted the use of studio-derived materials for attachment to boards.3

3Boyle’s dual status as poet and artist was important in the development of the collective practice, with its activities spread across a variety of media: he was invited to read his poetry at the 1963 Edinburgh Festival and at the same time to show “his” assemblages at the Traverse Gallery. Whilst installing the exhibition, Boyle and Hills became drawn into Ken Dewey’s staging of a “happening” for the International Drama Conference, organized by John Calder at the McEwan Hall of Edinburgh University. This event eventually bore the title Boyle devised for it, In Memory of Big Ed, and became notorious as the highest profile work of event-art yet staged in Britain. Boyle and Hills also took part in the second “happening” at the conference, Allan Kaprow’s Exit Piece.4 Returning to London, Boyle and Hills added the creation of events to their portfolio of practices. By the time of their first major London exhibition at Indica Gallery in July 1966, the couple in most ways fulfilled Kaprow’s prescription for artists working in the wake of painting’s failure: their output ranged between the production of objects and performance; it was exhibited or staged more often in informal, or domestic spaces rather than institutions; and they sought to “discover out of ordinary things the meaning of ordinariness”.5

4The Hague exhibition was the first full international exhibition of this totalizing engagement with the everyday. By 1969, two significant, governing vectors had been added to it: the work was now both indexical and aleatoric. The most visible objects in the Gemeentemuseum were the resin “earth pieces”. These had developed from the assemblage works in 1965–66, shortly before the Indica show. That exhibition marked the transition between one form of practice and another. All of the original sites for the earth pieces had, to varying degrees, been selected at random. Whilst several of the works in the Indica Gallery show were transfers of material onto boards, including organic materials fixed to a resin surface, others were either resin casts where only a thin layer of fine detritus had been incorporated into the resin pellicle, or where organic materials had been similarly preserved and fixed to a resin surface. As Patrick Elliott has observed, contemporary British sculptors including Phillip King and William Tucker also used new polymer resins, but none had attempted anything like this.6 After July 1966 the resin works would become Boyle and Hills’s most visible and recognizable mode of practice. However, whilst the earth pieces have subsequently often been accommodated within the rubric of “land art”, this is not how Boyle and Hills understood them.7 As Boyle put it in the ICA Bulletin of June 1965, “My ultimate object is to include everything.”8 The earth pieces were part of a wider aesthetic endeavour that examined the relation between sign and referent, and a parallel social project that promised—even if it could only rarely be executed—a total analysis of human physical, social, and environmental relationships.

6

The first step in this presentation of the object as referent had been the introduction of square boards of a pre-determined size. Rather than the assemblage being made only with the materials that the site offered—often including the surface on which it was made—it was now subjected to an element of modernist presentation through a paradigm which was being reprised at much the same time by Minimalist art—the grid. Whilst the resin incorporated a trace of the surface it recorded, to attain the effect of reality—to appear to be a readymade—it now required the intervention of the artists to give the effect of natural colour to the surface. But they were also required, for the work to appear wholly free from intervention, to mark their presence as artists only by erasing all traces of artistry. The work was “sculptural”, since it was three-dimensional, and produced by a sculptural process—negative casting. But it was defined by the edges of the grid, and thus followed the contested tradition of framed representation. Indeed, the earth pieces are still often appraised within the discourses of painting: Bill Hare, for example, positions them within abstraction.9 Furthermore, the earth pieces could be, and were, exhibited either on the gallery floor, horizontally, or on the wall, vertically.

9All of the sites of these earth pieces had, to varying degrees, been selected at random. The selection of sites within London had expanded to a global scale with the announcement of the “Journey to the Surface of the Earth” project during Boyle and Hills’s major exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in London in June 1969. The project was to make “multi sensual presentations of 1000 sites selected at random from the surface of the earth”.10 Starting in Boyle and Hills’s flat in August 1968, and then continuing at the ICA, friends and finally members of the public first threw, and later fired darts into a large map of the world. The only dart to land in Holland was near The Hague, and seeing this during the ICA exhibition, Locher invited the group to undertake its first multi-sensual survey and present the results.

10

Although they did not complete a full survey in Holland, according to the parameters they established for themselves, Boyle and Hills’s first overseas exhibition was clearly ambitious. It was marked by a striking amount of supporting activity, notably the publication of Journey to the Surface of the Earth: Mark Boyle’s Atlas and Manual. This volume came from the German publisher Edition Hansjörg Mayer, and is significant in a number of ways. Firstly, it emphasized the conceptual grounding of the Boyle project, previously only apparent in the ICA exhibition, and otherwise elided in the presentation of the single object. Indeed, the Atlas as a totalizing index and practical guide, with the artists heavily involved in its content and design, is best understood not as an analysis of the project but an integral part of it. Secondly, it took a European publisher—one already familiar with the ways in which the artist’s book in various guises might be bound into conceptual art projects—to recognize the emphasis and potential of Boyle and Hills’s activity. Thirdly, it marked Boyle and Hills as artists whose perspective was not parochial, but international. The overarching title for the project, Journey to the Surface of the Earth, more or less solicited invitations from institutions beyond the British Isles; the Gemeentemuseum exhibition in turn led to invitations from Norway (the Henie-Onstad Kunstsenter) and Germany.

Boyle Family would evolve not only from the collaboration between father and mother with a pair of rapidly maturing and artistically engaged children, but from the continual international activity that the concept of the Journey to the Surface of the Earth forced upon the collective. The Hague might only have been on the other side of the North Sea, but the exhibition marked a significant turn in the group’s patterns of making and exhibition work. Whereas before 1969, they had been part of the London art scene—where, in 1993, David Mellor placed them in his defining exhibition of that milieu, The Sixties Art Scene in London—they were now to become global artists.11 One of the penalties of this would subsequently be that it became increasingly difficult to locate Boyle Family’s work within the localizing framework of national art history. As Philipp Kaiser and Miwon Kwon’s exhibition Ends of the Earth: Land Art to 1974 (2012–13) or the writings of Stephanie Ross and Charles Green (amongst others) exemplify, it became possible to represent the project within various and at times conflicting international contexts through selective emphasis.12 However, the category where it might have been expected to fit comfortably, alongside contemporary, totalizing European conceptual projects, is one context where the Boyle project has not been adequately examined. The exhibition that followed Boyle and Hills’s installation at the ICA was a revised version of Harald Szeemann’s groundbreaking When Attitudes Become Form.13 If this was coincidence, it is in retrospect something more than fortuitous, for Szeemann’s show was one into which any of Boyle and Hills’ activities could have been readily accommodated.

11Certainly Boyle and Hills would later be compared to, and classified along with, a number of the artists included in When Attitudes Become Form—notably “earth artists” such as Richard Long, Robert Smithson, and Michael Heizer. Boyle and Hills were not “conceptual” artists in any specific sense—any more than were most of the artists included by Szeemann: the materialization of the fundamental concepts that underpinned their work was mostly expressed in media and material objects. Boyle and Hills’s practice ran completely counter to the attempted elimination of objects in favour of “knowledge”, that might be understood to characterize conceptualism as a practice.

However, in their emphasis upon the apodicticity of objects, in their refusal to read into, or have read into them, degrees of significance and meaning, at this moment in the 1960s Boyle and Hills seem to share many of the directions of thought that typify conceptual art in its broader senses. In their insistence on the literal properties of things in the world, their status first of all as pure, objective presence, Boyle and Hills share a far greater affinity than might be at first apparent with another collaborative project that began at much the same time—that of Bernd and Hilla Becher. The Bechers and the Boyles would both criss-cross continents in vans crammed with equipment, and became characterized by their insistence on one presentational format (albeit that the Boyles were unfairly labelled in this way). The Bechers undoubtedly made motivated choices both of general sites and specific locations that they photographed to produce their typologies of industrial forms. However, their re-evaluation of the Neue Sachlichkeit tradition of objectivity led them to a deliberate anonymity of style which mirrored the anonymity claimed for the industrial architecture and landscape that was their subject. Both couples thus operated on a basis of uninflected presentation of objects through their indices—the cast for the Boyles and the photograph for the Bechers. What varies between the two oeuvres is the character of that index and the mode of its selection: the Bechers concentrating on one aspect of industrial modernity and its obsolescence; Boyle and Hills taking a universalizing approach where everything matters equally.

Actual sites in The Hague were selected by the artists using darts on maps of increasingly large scale, and then thowing a right-angle in the field, which determined the orientation of the predetermined square. Because of their presentation as factual objects and their striking realism—which led some to think they were indeed “the real thing”, the earth pieces were to secure Boyle Family’s reputation, even though their project was conceived as far more diverse in its scope. The Hague earth piece was shown horizontally, as it had been cast, and came from a muddy track scarred by tyre marks and containing a piece of piping. A vertical “strata study”, made by pouring resin down a rock face, was shown vertically. Much of the exhibition was concerned with providing a context for the Hague earth-probe through a broad survey of the Boyles’ existing works. On the walls were casts from “The Tidal Series” (1969), made at Camber Sands in southern England, along with several earth pieces from “The London Series” and two “Snow Studies” (1969), also made at Camber. Locher would later record a certain bewilderment on the part of the audience in the Gemeentemuseum. One part of the audience found the principal earth piece “downright ugly”, and was unable to understand why such an ordinary subject needed to be recorded. They were, however, impressed by the technique used to record it. Others, more accustomed to looking at contemporary art, wanted to interpret the earth pieces on the basis of their encounters with artists such as Alberto Burri (using natural materials in abstract painting) or Antoni Tàpies (bringing real objects into the artwork and transposing them), and could not accommodate the governing concept that these were exact facsimiles of real objects chosen at random.14

14Incorporating the actual surface of the site into a permanent indexical trace was intended as only the first of some sixteen different activities. Some of these were specific and readily achievable ideas, such as taking a six-foot (1.8-metre) earth core with an auger and making a film involving a 360-degree pan from the centre of the site, or collecting seeds from the site. Other goals were more nebulous, such as making “a study of elemental forces working on the site”. The most demanding element was filming and taping in the local community, treating it “as a biological entity”, with these recordings then becoming the basis for performances under the title “Requiem for an Unknown Citizen”.15

15The use of chance for the earth pieces’ production seemingly eliminated the artists’ involvement, first in the visual appearance of the works, then in the choice of objects for the work, and finally in the process of choosing the site itself. At times, the only surviving act of motivation for “the artists” appeared to be the choosing of those who would choose on their behalf. However, the process of site selection, as it evolved, also included the recuperation of artistic identity from its intended universality. Within the world map used to determine sites for the “World Series”, the mark made by a dart covered an extensive area. To determine the location of earth pieces, the Boyles would take progressively larger scale maps, using their dart throwing process, and where possible involving the public in it. Eventually this defined an area where the artists used chance procedures in the field to select the final site. The definition of sites therefore, even if it remains chanced, passes back from the unseeing projection of others to the hands of the artists at the end of the selection process. This return of identity, however, is not accompanied by either a return to aesthetic choice or the non-aesthetic provocations of Marcel Duchamp. There is no special category of objects that, in their re-presentation, might challenge the status of the art object. All objects will serve equally well.

The Hague show presaged a decade of extraordinary success for Boyle Family, culminating in representing Britain at the 1978 Venice Biennale. If that institutional endorsement was a significant acknowledgment, one that afforded a complete “earth-probe” into a site in Sardinia, it was also a containment. It was an exhibition nominated in the identity of a single man—Mark Boyle—rather than the collective: and it emphasized as far as possible the pictorial thematic within the group project, rather than its unique combination of the pictorial with the performative, of the survey of the social and natural worlds presented, not as “culture” but as document.16 A project that was part of late modernism’s radical break with representation was recuperated in the terms provided by the traditions of landscape—rather than “land”-art and the painting of nature. Michael Compton’s essay for the British Council considered the project in terms of Romanticism and finding beauty in the everyday.17 But the Boyles’ corporate activity did not mirror that of the Renaissance or Baroque studio. Nor were the artists much interested in aesthetic categories—as the critic and curator Jasia Reichardt had made clear after the event Any Play or No Play (Theatre Royal, Stratford East, London, 1965).18 There Boyle and Hills synthesised a Duchampian “whatever” as describing the outcome of events, with a Schwitteresque “everything” as their potential contents. Far from challenging judgments of taste towards the object by the substitution of a single object, beyond the register of aesthetic prescription and indexical of all other objects, in privileging the plural and the democratic they suggested that not simply any thing can be that object, but every thing, and it does not matter what those objects are. All objects in a culture are capable of challenging judgments that would privilege one object, one experience, over another. That disinterested “interest” in presentation is the operating eidos of the Boyle project, with its principal goal not the replication of reality but the attentiveness of the spectator. Paradoxically, their collective practice and the “realism” of its objects means they have become deconstructive agents between the binary categories of description and nomination in which culture is formulated. Are they artist or artists? Is the work reality or representation? That corrosion of classification together with their international perspective has, perhaps, worked against the collective’s own status within British art."

16About the author

-

Chris Townsend is professor in the Department of Media Arts, Royal Holloway, University of London. His books include The Art of Rachel Whiteread and The Art of Bill Viola (both Thames & Hudson, 2004) and, with Alex Trott and Rhys Davies, Across the Great Divide: Modernism’s Intermedialities, from Futurism to Fluxus (Cambridge Scholars, 2014).

Footnotes

-

1

Journey to the Surface of the Earth: Mark Boyle’s Atlas and Manual (Cologne: Edition Hansjörg Mayer, 1970), np. ↩︎

-

2

Mark Boyle, “Beyond Image: Boyle Family”, in Beyond Image: Boyle Family, exh. cat. (London: Arts Council of Great Britain, 1986), 11. ↩︎

-

3

Chris Townsend, Interview with Mark Boyle and Joan Hills, 5 Jan. 2001. ↩︎

-

4

For fuller accounts of the conference and these events see, inter alia, Charles Marowitz, “Happenings at Edinburgh” and Ken Dewey, “Act of San Francisco at Edinburgh”, Encore 46 (Nov.–Dec. 1963), reprinted in New Writers IV: Plays and Happenings (London: Calder and Boyars, 1967), 67–76; “High Jinks End Drama Conference”, The Scotsman, 9 Sept. 1964, 4; Andrew Wilson, “Towards an Index for Everything: The Events of Mark Boyle and Joan Hills 1963–71”, in Patrick Elliot, Bill Hare, and Andrew Wilson, Boyle Family, exh. cat. (Edinburgh: National Galleries of Scotland, 2003); and chap. 5 in my forthcoming A World at Random: The Art of Boyle Family. ↩︎

-

5

Allan Kaprow (1958), “The Legacy of Jackson Pollock”, in Essays on the Blurring of Art and Life, ed. Jeff Kelley (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1993), 9. ↩︎

-

6

Patrick Elliott, “Presenting Reality: An Introduction to Boyle Family”, in Elliot, Hare, and Wilson, Boyle Family, 13. ↩︎

-

7

See, for example, Philipp Kaiser and Miwon Kwon’s exhibition, Ends of the Earth: Land Art to 1974, MoCA Los Angeles/Haus der Kunst, Munich, 2012–13. ↩︎

-

8

Mark Boyle, artist’s statement, ICA Bulletin, June 1965, n.p. ↩︎

-

9

Bill Hare, “Old Habits of Looking, New Ways of Seeing: The Paintings of Boyle Family”, in Elliot, Hare, and Wilson, Boyle Family, 81–87. ↩︎

-

10

Journey to the Surface of the Earth, np. ↩︎

-

11

David Mellor, The Sixties Art Scene in London (London: Phaidon, 1993). ↩︎

-

12

Stephanie Ross, “Gardens, Earthworks, and Environmental Art”, in Salim Kemal and Ivan Gaskell, eds., Landscape, Natural Beauty and the Arts (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 183–98; Charles Green, The Third Hand: Collaboration in Art from Conceptualism to Postmodernism (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2001). ↩︎

-

13

When Attitudes Become Form (Works—Concepts—Processes—Situations—Information), was held at Kunsthalle Bern (March–April 1969), Museum Haus Lange Krefeld (May–June 1969), and at the ICA, London (Aug.–Sept. 1969). ↩︎

-

14

J. L. Locher, Mark Boyle’s Journey to the Surface of the Earth (Stuttgart: Edition Hansjörg Mayer, 1978), 49. ↩︎

-

15

Journey to the Surface of the Earth. “Requiem” has, in fact, only been staged once (in Rotterdam in 1971), without being associated to any earth-probe, and using material recorded in London. See Locher, Mark Boyle’s Journey, 146–53. ↩︎

-

16

The first exhibition to properly acknowledge the collaborative nature of the project was Mark Boyle and Joan Hills Reise um die Welt at the Kunstmuseum Lucerne in November 1978. The group would not be described as “Boyle Family” until a show at the Henie-Onstad Kunstsenter in 1985. ↩︎

-

17

Michael Compton, Mark Boyle, British Pavilion, Venice Biennale, 1978 (London: British Council, 1978). ↩︎

-

18

Jasia Reichardt, “On Chance and Mark Boyle”, Studio International (Oct. 1966): 165. ↩︎

## Bibliography

Beyond Image: Boyle Family. Exh. cat. London: Arts Council of Great Britain, 1986.

Boyle, Mark. Artist’s statement. ICA Bulletin, June 1965.

– – –. “Beyond Image: Boyle Family.” In Beyond Image.

– – –. Journey to the Surface of the Earth: Mark Boyle’s Atlas and Manual. Exh. cat. Cologne: Edition Hansjörg Mayer, 1970.

– – –. Three Poems. Paris Review 8, no. 29 (Winter–Spring 1963): 81–83.

Dewey. Ken. “Act of San Francisco at Edinburgh.” Encore 46 (Nov.–Dec. 1963). Reprinted in New Writers IV: Plays and Happenings. London: Calder and Boyars, 1967.

Elliott, Patrick. “Presenting Reality: An Introduction to Boyle Family.” In Patrick Elliot, Bill Hare, and Andrew Wilson, Boyle Family. Exh. cat. Edinburgh: National Galleries of Scotland, 2003, 9–19.

Hare, Bill. “Old Habits of Looking, New Ways of Seeing: The Paintings of Boyle Family.” In Elliot, Hare, and Wilson, Boyle Family, 81–116.

Kaprow Allan (1958). “The Legacy of Jackson Pollock.” In Essays on the Blurring of Art and Life. Ed. Jeff Kelley. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1993.

Marowitz, Charles. “Happenings at Edinburgh.” Encore 46 (Nov.–Dec. 1963), reprinted in New Writers IV: Plays and Happenings. London: Calder and Boyars, 1967.

Wilson, Andrew. “Towards an Index for Everything: The Events of Mark Boyle and Joan Hills 1963–71.” In Elliot, Hare, and Wilson, Boyle Family, 45–59.

Imprint

| Author | |

|---|---|

| Date | 18 July 2016 |

| Category | Article |

| Review status | Peer Reviewed (Editorial Group) |

| License | Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) |

| Downloads | PDF format |

| Article DOI | https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-03/ctownsend |

| Cite as | Townsend, Chris. “Mark Boyle and Joan Hills at the Gemeentemuseum, The Hague.” In British Art Studies: British Sculpture Abroad, 1945 – 2000 (Edited by Penelope Curtis and Martina Droth). London and New Haven: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art and Yale University Press, 2016. https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-03/ctownsend. |