Sight Unseen

Sight Unseen: Anthony Caro’s Prairie, 1967

By Sarah Stanners

Prologue: Out of Sight

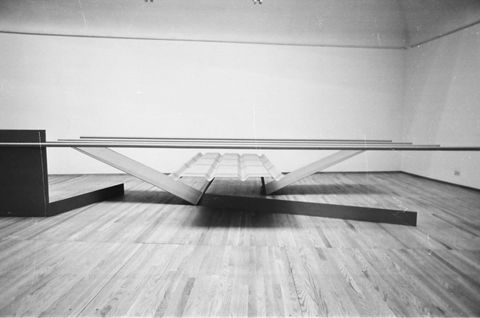

Prairie, a modern masterwork of painted steel by Sir Anthony Caro (1924–2013), has crossed the Atlantic no fewer than eight times since its making in London in 1967 (fig. 1). The international life of Prairie is extensive, especially considering the serious logistics involved in disassembling, shipping, and installing a sculpture that measures 38 x 229 x 126 inches (96.5 x 582 x 320 cm):

- Recent Sculpture, Kasmin Gallery, London, 1967

- Anthony Caro, X Bienal de Sao Paolo, 1969

- Anthony Caro, Hayward Gallery, London, 1969

- Anthony Caro: A Retrospective, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1975

- Anthony Caro: A Retrospective, Walker Art Centre, Minneapolis, MN, 1975

- Anthony Caro: A Retrospective, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 1975

- Transformations in Sculpture, Solomon R Guggenheim Museum, New York, 1985

- British Art in the 20th Century: The Modern Movement, Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, 1987

- British Art in the 20th Century: The Modern Movement, Royal Academy of Art, London, 1987

- Caro a Roma, Trajan Markets, Rome, 1992 (fig. 2)

- Anthony Caro, Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo, 1995

- Anthony Caro, Tate Britain, London, 2005

Prairie did not, however, make the trip for the 2015 double down of Caro survey exhibitions jointly organized by The Hepworth Wakefield and the Yorkshire Sculpture Park (YSP).1 Titled Caro in Yorkshire, the aim of these complementary exhibitions was to celebrate and commemorate the career of Caro with a showing of notable works such as Twenty Four Hours (1960), Sculpture Seven (1961), Month of May (1963), and Promenade (1996), to name a few. Adrian Searle of The Guardian called the exhibition “Larger and more comprehensive even than the Tate Britain Caro retrospective of 2005”, and yet Prairie was conspicuously missing from this robust reunion.2 Also obvious was the fact that an exhibition of Henry Moore’s work held the place of pride in the YSP’s main gallery at the time of this important survey of Caro’s work.3 Instead, Caro’s work could be found dwarfed throughout the YSP’s rolling fields and at the Park’s Longside Gallery, roughly two kilometres out from the YSP Centre. At The Hepworth Wakefield, Caro was deftly inserted within the canon of great British sculptors of the twentieth century as the exhibition there was indirectly framed within the superb permanent collection.

1The myopic selection of works for the exhibitions held in Yorkshire in 2015, suggests that the best of Caro from the point of view of the UK is different than the best of Caro from an American point of view. Caro in the UK is a crescendo after the major movement of Moore. Caro in America struck an all-new chord. In 2007, Caro recalled his close American connections, and the freedom of disconnection abroad:

4When I went to America the excitement in New York was in painting not in sculpture. When I went to Bennington, my friends and neighbours were painters Olitski and Noland. At weekends, Noland would have people to stay, critics, and painters. I cannot think of a single sculptor. For me it was very interesting. I could almost divorce myself from the history of sculpture.4

His relations with David Smith are curiously missing in the above statement. This erasure implies that his “almost divorce” from the history of sculpture may not have been just a matter of new contexts (geographic and social) but actually a conscious decision of the artist who revelled in the disassociation from notions of patrimony in sculpture.

Was Prairie not included in the survey mounted by YSP and The Hepworth Wakefield because, to the British eye, it appears to be an outlier? Caro felt that Prairie was his most successfully abstract sculpture ever.5 Referring to nothing outside of itself, Prairie does not serve to demonstrate the patrimony of British sculpture. Even the title feels American, although it is a misnomer: not, in fact, referring to low-lying fields of golden crops, but actually pointing to the commercial name for the paint colour “Prairie Gold” that the artist had intended to use (though ultimately did not) after first painting the sculpture blue (fig. 3).6

5

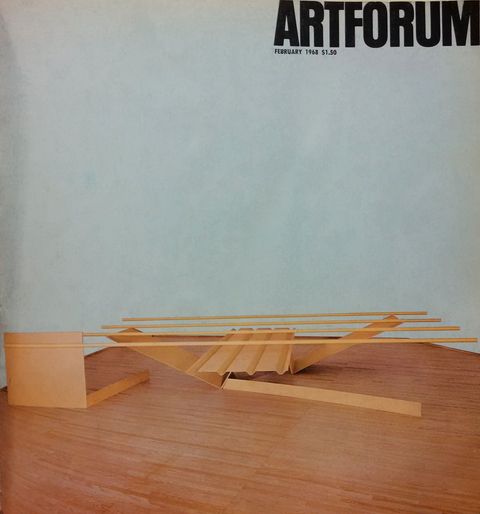

While a relatively limited number of people had the opportunity to see Prairie’s inaugural display in 1967 at Kasmin Gallery in London, a wide American audience for Prairie was cultivated just months later, in 1968, by the championing words of Michael Fried that landed the sculpture on the cover of Artforum (fig. 4).

The Eye’s Mind: Prairie and Michael Fried

The American art critic and art historian Michael Fried first met Caro in 1961 in Hampstead, London.7 There, in the artist’s courtyard, Fried had an epiphany of sorts, claiming to have seen two of the most groundbreaking abstract sculptures he had ever seen: Midday (1960) and Sculpture Seven (1961).8 Six years later, Fried would again be impressed by the progressive abstraction of two more Caro sculptures. After seeing Caro’s Deep Body Blue (1967) and Prairie at Kasmin Gallery, Fried wrote a compelling (and now oft-cited) review titled “Two Sculptures by Anthony Caro” for Artforum’s February 1968 issue (figs. 6–10).9 Both sculptures were displayed in one room, but Prairie caught Fried’s eye most of all:

710More explicitly than any previous sculpture, Prairie compels us to believe what we see rather than what we know, to accept the witness of the senses against the constructions of the mind.10

Fried’s review put Prairie on the map in America, bolstered by the fact that it made the cover of Artforum, making it the top model for abstract sculpture in the US, despite its English birth. Following the popular review in Artforum, Caro wrote two letters to Fried (29 February and 24 March 1968):

11I am delighted that the sculptures meant so much to you—your description of Prairie is the first accurate one . . . except that, believe it or not—thanks to Charlie (Hendy)!—the poles are steel . . . The way you saw just exactly what the upright rectangle that supported the pole in Prairie was doing, and it gives me a real thrill of pleasure to have my work so accurately grasped.11

Fried’s review had not pointed to the lineage of sculpture that came before Prairie. Instead, he pointed to philosophy and even briefly to architecture when describing the 1967 work by Caro. Fried celebrated Prairie’s “extraordinary marriage of illusion and structural obviousness”, feeling no need to add significance to the work by weaving it within a history of sculpture and influences.12 Fried cast a purely American eye (or a purifying American eye) upon Prairie that allowed for a new generation of painters and sculptors to accept it as their own new way forward. It is fitting that a steel sculpture praised for its defiance of gravity would grant a certain amount of levity to young sculptors who were encouraged to feel unburdened by the history of building and shaping mass in their sculptures.

12

In the spring of 1967, Caro would publicly protest against the Tate’s proposal to permanently display (by facilitation of public funds) a large gift of Henry Moore’s work. Along with about forty other British artists, Caro signed an open letter to the Times to declare, among other firm points, that:

13Whoever is picked out for this exceptional place will necessarily seem to represent the triumph of modern art in our society. The radical nature of art in the twentieth century is inconsistent with the notion of an heroic and monumental role for the artist and any attempt to predetermine greatness for an individual in a publicly financed form of permanent enshrinement is a move we as artists repudiate.13

Ultimately, Moore made a major gift of original plasters to the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO) in Toronto, which built a permanent gallery with Moore’s input on the architecture of the purpose-built space.

Prairie in the USA

Caro had expressed his enthusiasm for Prairie to Lewis Cabot, a Boston-based connoisseur of Modernist art who would become a longtime supporter of Caro.14 Remaining in the United States, Cabot purchased Prairie sight unseen from its 1967 London debut at Kasmin Gallery.15 Cabot made the purchase with the understanding that he was building a careful repository of works by Caro, and waited several years before shipping Prairie to his own storage in the US. Before taking physical possession of the sculpture, Cabot lent Prairie to important exhibitions, including the X Bienal de Sao Paulo and London’s Hayward Gallery in 1969.

14By 1975, when Prairie was shown in the artist’s first American retrospective, which toured widely,16 Prairie had changed hands to the collection of Lois and Georges de Menil, who were also based in the USA.17 In 1977, the de Menils placed Prairie on long-term loan with the National Gallery of Art (NGA) in Washington, DC, where it resides today (figs. 12, 15, 16) The accession file on the sculpture and its history in the custody of the NGA is chock-full of firm letters from the de Menils, who consistently, and successfully, argue for the near-constant public display of Prairie at the gallery.18 While in the custody of the NGA, Prairie has continued to be shown far and wide, including Rome in 1992, Tokyo in 1995, and back to its birthplace in London, for Tate Britain’s Caro retrospective in 2005. It is notable that Prairie was included in Tate’s Caro retrospective but not in the most recent in-depth survey in Yorkshire. Posthumous large-scale exhibitions are, of course, quite a different thing from a major show during an artist’s lifetime—when curators and museums must respect what the artist points to as being important. After death, alternate stories are much easier to articulate.

16

After Prairie: Kenneth Noland and Cadence

If not looking too hard, Cadence might be understood as an icon, serving to harken back thoughts of Prairie, yet held in equal reverie by onlookers. In 1967, Rosalind Krauss issued some critical pushback that could have served as a preemptive strike to anyone claiming to see Cadence as pale by comparison:

Caro was close to the best formalist writers but certainly did not think twice about looking back in his work. Fried called Prairie “a touchstone for future sculpture”, lending it a superlative power that might have made other artists freeze up with the pressure of having reached a high watermark.21 Caro recalled:

2122I hoped at the time I made [Prairie] that I would be able to go even more abstract. But in the end I wanted to put something of the real world in my sculptures. Indeed, since Prairie, all my sculptures have a part that is directly linked to the world around.22

The link that Cadence made to the world was to point back at Prairie. By definition, “cadence” may refer to a slight change or inflection in one’s voice, or expression. Cadence is a variation on Prairie. It was also made with Noland in mind (fig. 14). Cadence remained in Noland’s possession for the rest of his life and now resides in a private collection in Canada.

The View

As addressed at the outset of this article, the exhibition Caro in Yorkshire, shared between the YSP and The Hepworth Wakefield in 2015, nestled the artist firmly within a British context. In the midst of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, Prairie holds court with a variety of masterful works of art from around the world (fig. 15). In the context of the NGA, Prairie is seen as a triumphant Modernist sculpture—displayed without narrative, but simply in conversation with other select works of art. If it were displayed at the National Gallery, London, would it be framed as a chapter within a wider history of sculpture?

Reviewing the photographs throughout this essay, it is apparent that Prairie looks different from every angle. The viewer has a similar experience in “walking” this sculpture (fig. 16). Round and round, and round again, Prairie takes up one’s entire field of vision at one moment and then effortlessly slips away with virtually no sense of mass from another view. For now, photographs will have to suffice, as Prairie has just come off display at the NGA. A “Caro in America” show may be due, or even overdue, lest Prairie remains sight unseen.

Acknowledgements

This essay would not have been possible without the generous support of Barford Sculptures Limited (including insights from Olivia Bax), John Kasmin, and Harry Cooper with the National Gallery of Art, who all generously approved or provided images. For their insights as dedicated patrons of the artist, I would like to sincerely thank Lewis Cabot, David Mirvish, and Lois and Georges de Menil. I would also like to thank the artist’s son, Paul Caro. A debt of gratitude is also due to the subject of my essay, Anthony Caro, who had always accepted interviews with me and was truly a kind and generous man.

About the author

-

Dr Stanners completed her PhD in art history at the University of Toronto (2009), as well as a SSHRC Postdoctoral Fellowship at the University of British Columbia (2009–11). Her dissertation, Going British and Being Modern in the Visual Art Systems of Canada, 1906–76, focused on the impact of British authority on the founding collections and exhibition practices of museums across Canada. She has published extensively on the topic of Henry Moore and Canada, as well as Color Field art, and co-curated the major Jack Bush retrospective at the National Gallery of Canada (Nov. 2014—Feb. 2015) with their Director and CEO, Marc Mayer, which toured to the Art Gallery of Alberta (May—Aug. 2015). Dr Stanners is the author of the forthcoming Jack Bush Paintings: A Catalogue Raisonné, and regularly delivers talks on her research and experience in compiling a major catalogue raisonné. She is currently Director, Curatorial & Collections, at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection, Kleinburg, Ontario.

Footnotes

-

1

Caro in Yorkshire, The Hepworth Wakefield/ Yorkshire Sculpture Park, 18 July–1 Nov. 2015. ↩︎

-

2

Adrian Searle, “Anthony Caro in Yorkshire review—Sculpture that can take your breath away”, The Guardian, 16 July 2015. ↩︎

-

3

Henry Moore: Back to a Land, Yorkshire Sculpture Park, 7 March–6 Sept. 2015. ↩︎

-

4

Anthony Caro in interview with Patrick Le Nouëne, Dec. 2007, Anthony Caro Association of Museum Curators in the Nord Pas-de Calais Region (2008), 30, quoted in Caro in Yorkshire, exh. cat. (Yorkshire Sculpture Park/ The Hepworth Wakefield, 2015), 23. ↩︎

-

5

Anthony Caro, Caro, ed. Amanda Renshaw (New York: Phaidon, 2014), 168. ↩︎

-

6

Caro, Caro, ed. Renshaw, 170. ↩︎

-

7

Michael Fried, Art and Objecthood: Essays and Reviews (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1998), 7. ↩︎

-

8

Fried, Art and Objecthood. ↩︎

-

9

Michael Fried, “Two Sculptures by Anthony Caro”, Artforum 6, no. 6 (Feb. 1968): 24–25. ↩︎

-

10

Fried, “Two Sculptures by Anthony Caro”, 25. ↩︎

-

11

Excerpts provided to author by Barford Sculptures Limited, 20 Feb. 2016. ↩︎

-

12

Fried, “Two Sculptures by Anthony Caro”, 24–25. ↩︎

-

13

Open letter from Craigie Aitchison and others, “Henry Moore’s Gift”, Times, 26 May 1967, 11. ↩︎

-

14

Author in conversation with Lewis Cabot, 11 Jan. 2016. ↩︎

-

15

Author in conversation with Cabot, 11 Jan. 2016. ↩︎

-

16

The exhibition Anthony Caro: A Retrospective was shown at Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1975, before touring to Walker Art Center, Minneapolis; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; and Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. ↩︎

-

17

Lewis Cabot recalls selling Prairie around 1973 or 1974 at the time of his divorce. Author in conversation with Cabot, 11 Jan. 2016. ↩︎

-

18

Prairie was just recently taken off public display at the NGA in May 2016. ↩︎

-

19

Author in conversation with Lewis Cabot, 11 Jan. 2016; and author in conversation with David Mirvish, 17 June 2016. ↩︎

-

20

Rosalind Krauss, “On Anthony Caro’s Latest Work”, Art International 11, no. 1 (Jan. 1967): 26–29. ↩︎

-

21

Fried, “Two Sculptures by Anthony Caro”, 25. ↩︎

-

22

Caro, Caro, ed. Renshaw, 168. ↩︎

Bibliography

Caro in Yorkshire, exh. cat. Yorkshire Sculpture Park/ The Hepworth Wakefield, 2015.

Caro, Anthony. Caro. Ed. Amanda Renshaw. New York: Phaidon, 2014.

Fried, Michael. Art and Objecthood: Essays and Reviews. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1998.

– – –. “Two Sculptures by Anthony Caro.” Artforum 6, no. 6 (Feb. 1968): 24–25.

Krauss, Rosalind. “On Anthony Caro’s Latest Work.” Art International 11, no. 1 (Jan. 1967): 26–29.

Imprint

| Author | |

|---|---|

| Date | 18 July 2016 |

| Category | Article |

| Review status | Peer Reviewed (Editorial Group) |

| License | Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) |

| Downloads | PDF format |

| Article DOI | https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-03/sstanners |

| Cite as | Stanners, Sarah. “Sight Unseen: Anthony Caro’s Prairie, 1967.” In British Art Studies: British Sculpture Abroad, 1945 – 2000 (Edited by Penelope Curtis and Martina Droth). London and New Haven: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art and Yale University Press, 2016. https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-03/sstanners. |