Hybrid Sculpture of the 1960s

Hybrid Sculpture of the 1960s

By John J. Curley

Abstract

In 1965–66, British artists Gerald Laing and Peter Phillips exhibited their sculpture Hybrid in New York City. This object was the result of gathering and tabulating the artistic preferences of over 130 critics, collectors, curators, and gallerists, mostly in New York and London. Considering Hybrid’s international scope, its origin as dematerialized data, and its participation in the mid-1960s penchant for confusing notions of painting and sculpture, it questions the very parameters implied by the term “British Sculpture”.

This special issue of British Art Studies is focused upon international notions of “British sculpture” in the postwar period. I want to begin this short essay by questioning the stability of this descriptive category. With a networked world of international exhibitions and art magazines in the 1950s and 1960s (at least among the United States and Western Europe), do national categorizations still make sense? Medium distinctions are equally unstable, as major figures at this moment were producing paintings that aspired to the condition of objects and vice-versa.

The work of Anthony Caro demonstrates the problems with the label “British sculpture”. While he is, of course, a British sculptor, his works—especially his painted steel sculptures from the 1960s—were until recently most often discussed in relation to American painters like Morris Louis and Kenneth Noland, as well as the American critics Clement Greenberg and Michael Fried.1 By this logic, his Early One Morning from 1962 is as “American” as it is “British”, considering its discursive position in the 1960s. Furthermore, Caro’s work during the decade was sometimes shown with paintings in major international exhibitions, whether British or American, and not always with other sculpture. In the British Pavilion at the 1966 Venice Biennale, he was the lone sculptor showing alongside four painters, for example.2 Noland, Louis, Caro, an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1968, demonstrates the fluidity of both national and medium designations. Caro’s work from this period, especially in international exhibitions, thus expressed two variants of hybridity: a transnational, Anglo-American hybridity and a transmedial one, residing between painting and sculpture. Thus, in an international context, Caro’s work can question the singularity of both the terms “British” and “sculpture”. This blurring of national and medium-specific distinctions in the 1960s was by no means unique to Caro; in fact, the important exhibition Primary Structures at New York’s Jewish Museum in 1966 brought together artists from both Britain and the United States under the rubric of reappraising “the inherent nature of a painting or a sculpture”.3 For a further discussion of Caro’s work abroad, see Sarah Stanners’s essay in this special issue.

1It is fitting that it took two British painters, temporarily residing in the United States in the mid-1960s, to create an object that fully encapsulates this hybridity and charts its implications. The artists were Gerald Laing (1936–2011) and Peter Phillips (b. 1939), and the sculpture is, almost too perfectly, entitled Hybrid from 1965–66 (fig. 1). In the early 1960s, Laing and Phillips had been loosely grouped with the second generation of British Pop painters such as David Hockney, Derek Boshier, and Pauline Boty. Both Laing and Phillips explored themes and motifs associated with the mass media, including starlets and car culture. What clearly interests Laing in his painting Brigitte Bardot from 1963 is the translation of the French starlet into a halftone newspaper image; as he said later, “We don’t know Brigitte Bardot—we know her through the newspaper image.”4 As a handmade object resembling a mass-produced one, Laing’s mediated technique thematizes the image as information to be distributed. Choosing Bardot as his subject emphasizes the globalized nature of the image, since she was among the most famous faces in the Western world at this moment. Phillips, on the other hand, gained renown in the early 1960s for his paintings that incorporated the subject matter of machines and games. In The Entertainment Machine (1961), viewers see circuits and what appears to be an encryption apparatus in the lower right quadrant. In part, the painting suggests a correlation between the numbers and squares of colour visible on the spindle.

4

Both Laing and Phillips, like many American and European Pop artists such as Andy Warhol, Gerhard Richter, and Sigmar Polke, were thus interested in paintings that thematized the translation of found, pre-existing images into code or information, whether a transformation of Bardot into a halftone screen or depictions of playful encryption machines.5 And when these two painters made a sculpture in the mid-1960s while residing in the US, they addressed, among other things, thorny questions about how such an approach to art making could be applied to three-dimensional objects. In what ways can a sculpture be transformed into information, into data? How can one make an object that addresses notions of image transmission, a theme so important to many Pop painters? Can the very process of cultural export and expectations create a work of art? Put simply, Hybrid is a transnational sculpture that can be reduced to transmittable information. And, furthering the implication of the title, the information was a tabulation of averaged Anglo-American artistic tastes.

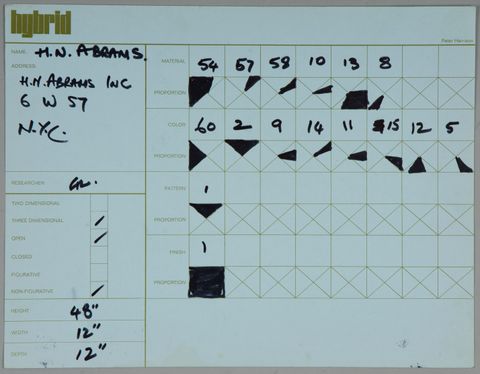

5Laing and Phillips set out, methodically, to make an ideal work of art based on market research. The painters first constructed two sample kits with numbered examples of different colours, materials, and finishes, reminiscent of the kind of boxes taken door-to-door by the era’s salesmen (fig. 2). Laing and Phillips then spent ten months questioning 137 critics, curators, art publishers, and collectors, mostly from New York and London (although some were based in Los Angeles and Paris). Respondents included Lawrence Alloway, Ryner Banham, John Canaday, Leo Castelli, Max Kozloff, Norbert Lynton, and Robert Fraser.6 The only parameter the artists outlined was that the object would be for a “sitting room”.7 As we can see in the completed questionnaire of Harry Abrams, the art publisher based in New York, respondents chose the quantity and type of variables within four categories for their ideal work: material, colour, pattern, and finish (fig. 3), using the corresponding number from the sample kit. Then, respondents coloured-in a percentage of a diamond-shape to indicate the desired proportion for each of the selected varieties. For instance, Abrams’s wishes dictated a sculpture comprised of 25 percent of two colours and diminishing percentages of six more. On the left side of the questionnaire, there were simpler tick-the-box questions: two-dimensional or three-dimensional? Open or closed? Figurative or non-figurative? Finally, respondents could indicate the ideal size of the object. Each questionnaire, therefore, gathered a detailed account of the respondent’s aesthetic preferences; in total, the 137 completed forms represent an overwhelming amount of data to process.

6

The first page from a Life magazine article on the project captures the endless possibilities available for the work of art: "How do you want it to look? What format: Two-dimensional? Three-dimensional? What style: Figurative? Abstract? Pointillist? Pop? What material: Bronze? Plastic? Rubber? Feathers?"8The data on each of the standardized forms was then fed into IBM computers at Bell Laboratories to come up with the parameters for the consensus object, which ended up, for example, as 28.6 percent aluminium, 30 percent Plexiglas, and 23.6 percent brass.9 Laing and Phillips made two full-size models (priced at US$1,100 each) and ten maquettes (US$150 each). These were exhibited at New York’s Kornblee Gallery in 1966, with the large ones “rotat[ing] on turntables like new cars on display”.10 The artists also mounted a marketing campaign with badges and a poster that, in the words of Phillips, mimicked the look and attitude of the now-classic Volkswagen ads from the period, even naming their company “Hybrid Enterprises”.11 With coverage in national magazines such as Life and Time, as well as a cover story in Arts Magazine, such publicity methods were clearly effective. While it was reported as a novelty story in the mass press, Hybrid nevertheless exposed in clear and explicit ways the repressed links between fashion trends, marketing, and the seemingly rarefied realm of contemporary art. And if the American press can be considered its own space of exhibition, perhaps no sculpture was more visible in 1966 than that of Laing and Phillips.

8Of course, the finished sculpture did not materialize from the data alone. Lawrence Alloway reported on the unavoidable arbitrariness of the process: “Laing and Phillips made drawings from the collated statistics, translating the results into visual form, and of course there were many possible variables of interpretation.”12 As Alex Taylor has recently noted, the realization of the sculpture was “laboriously manual”, involving numerous sketches by the artists.13 Phillips himself remembers that the computer calculations did not supply guide images.14 As with the translation of an object, portrait, or environment into a photograph, then into newsprint, and finally into a Pop painting (like a Warhol or Laing), the voyage from compiled survey data to finalized sculpture involves the friction and “noise” of mediation and artistic choices. Laing and Phillips could have realized Hybrid in many different configurations.

12Hybrid functions on many levels—notably anticipating Hans Haacke’s and Komar and Melamid’s later work based upon polling data.15 For the purposes of this essay, however, it raises two crucial issues about British sculpture in an international context in the 1960s. First, we see an explicit attempt to give form to mid-1960s Anglo-American tastes, especially with the project’s focus on critics, curators, publishers, and collectors—those involved in what Phillips called the “business of art”, its marketing.16 What is particularly intriguing, as David Mellor has noted, is that Hybrid resembles the look of British New Generation sculpture, like examples by William Tucker, Phillip King, and David Annesley.17 Along these lines, Hybrid was on view in New York at the exact time of the opening of Primary Structures, the important show curated by Kynaston McShine at the Jewish Museum that I referenced at the start. The exhibition is best known for placing these New Generation sculptors alongside more hard-edged American artists that came to be associated with Minimalism. Hybrid and Primary Structures thus exemplify a brief, fleeting transatlantic consensus about what contemporary sculpture should look like in the mid-1960s.

15Laing and Phillips each had sculptures on view in Primary Structures. Laing’s Trace (1965) is a ribbon-like form shown against a wall where optically it can appear flat ; Phillips’s Tricurvular (1965–66) is a curved form that starts on the wall and then cascades to the floor. Both of these works, therefore, deal with the confusion between painting and sculpture, or between flatness and three-dimensionality. According to the Primary Structures catalogue, this was the point of the show: “Depending upon the way in which space is used and occupied by a form, the material means, and the artist’s intention, as we may understand it, we name the work a ‘painting’ or a ‘sculpture’.”18 The exhibition posited that medium distinctions were thus largely arbitrary. Primary Structures was full of transmedial works, and Hybrid, on view in New York at the same time less than a mile away, addressed these same issues in a different way.

18Which leads me to the second important issue Hybrid raises about British sculpture abroad: it easily travels. It demonstrates one way that even a sculpture can be broken into a code and transmitted. If Pop paintings, like silk screens by Warhol (and the canvases of Laing and Phillips themselves), thematized the ability for media images to travel—whether by satellite, telephone lines, or an encryption apparatus—Hybrid is a sculpture that can be reduced to mere information, the tabulated results of a market survey. One could pack the computed aggregates of the survey in a folder and mail them anywhere for the consensus object to be produced, albeit with different results with each reconstitution. The project as a whole effects the dematerialized translation of an object into a code and then its realization back into an object. If the easily transportable materials of Conceptual art—its index cards, snapshots, and binders—would soon make international exhibitions easier to assemble, then Hybrid maintained a dialectical tension between a physical object and the weightless abstraction of data.

In 1966, the same year as Primary Structures and the exhibition of Hybrid, Anthony Caro turned to making his table sculptures, such as Table Piece XXII from 1967 (fig. 4). While different, might we view such a work as a similar, albeit less conceptual, gesture? After getting the suggestion from the American critic Michael Fried in 1966, Caro began to make sculptures that were not maquettes of larger works, but rather small, autonomous sculptures. But crucially, they can literally be carried and easily transported for global exhibitions, as well as for overseas collections. Table Piece XXII even has a handle to make such portability explicit. Like Laing and Phillips’s Hybrid, Caro’s table piece is an Anglo-American sculpture aspiring to the portable conditions of painting."

About the author

-

John J. Curley is Associate Professor of Art History in the Department of Art at Wake Forest University. He has published widely on American and European postwar art and photography. He is the author of A Conspiracy of Images: Andy Warhol, Gerhard Richter, and the Art of the Cold War (Yale University Press, 2013) and is currently at work on two new book projects: Art and the Global Cold War: A History and Hybrid Objects: Postwar British Sculpture between America and Europe. His research has been supported by the Getty Research Institute, the Yale Center for British Art, the Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst (DAAD), and the Henry Moore Institute, among others.

Footnotes

-

1

See Bernard Cohen, Harold Cohen, Robyn Denny, Richard Smith, Anthony Caro: XXXIII Venice Biennale 1966 British Pavilion (London: British Council, 1966). ↩︎

-

2

See Bernard Cohen, Harold Cohen, Robyn Denny, Richard Smith, Anthony Caro: XXXIII Venice Biennale 1966 British Pavilion (London: British Council, 1966). ↩︎

-

3

Kynaston McShine, “Introduction”, in Primary Structures: Younger American and British Sculptors (New York: Jewish Museum, 1966), np. ↩︎

-

4

Gerald Laing (1993), quoted in David Mellor, The Sixties Art Scene in London (London: Phaidon, 1993), 139. ↩︎

-

5

For a discussion of Andy Warhol and Gerhard Richter in these terms, see John J. Curley, A Conspiracy of Images: Andy Warhol, Gerhard Richter, and the Art of the Cold War (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2013). ↩︎

-

6

The completed surveys, as well as the sample kits, the realized sculpture, and other materials are in the collection of the Harvard Art Museums, gift of John and Kimiko Powers in 1977. Alex Taylor describes the sample kits in informative detail in “Reconsidering the Average Object of Art”, delivered at the “Pop Art and Beyond” conference on 20 March 2014 at University College London. Text of paper is online at https://popartandbeyond.wordpress.com/2014/04/21/reconsidering-the-average-object-of-art-1965-1966/. ↩︎

-

7

“Hybrid”, The New Yorker, 30 April 1966, 35. ↩︎

-

8

“Market Research Art”, Life, 20 May 1966, 51. ↩︎

-

9

“Everybody’s Object”, Time, 29 April 1966, 85. ↩︎

-

10

“Everybody’s Object”, 85. ↩︎

-

11

Peter Phillips, quoted in “Hybrid”, 35. ↩︎

-

12

Lawrence Alloway, “Hybrid”, Arts Magazine 40, no. 7 (May 1966): 41. For another perspective from the art press, see Gene Swenson, “Hybrid: A Time of Life”, Art and Artists 1, no. 2 (June 1966): 62–65. ↩︎

-

13

Taylor, “Reconsidering the Average Object of Art.” ↩︎

-

14

Peter Phillips, interview with author via Skype, 18 June 2015. ↩︎

-

15

Hans Haacke famously asked visitors to the Museum of Modern Art in New York their thoughts on New York Governor (and MoMA board member) Nelson Rockefeller’s opinion on the Vietnam War in 1969. Komar and Melamid polled people in various countries to figure out aesthetic tastes; see America’s Most Wanted Painting from 1994, for example. http://awp.diaart.org/km/usa/usa.html. ↩︎

-

16

Phillips, interview with author. ↩︎

-

17

Mellor, Sixties Art Scene in London, 114. ↩︎

-

18

McShine, “Introduction,” np. ↩︎

Bibliography

Alloway, Lawrence. “Hybrid.” Arts Magazine 40, no. 7 (May 1966): 41.

British Council, London. Bernard Cohen, Harold Cohen, Robyn Denny, Richard Smith, Anthony Caro: XXXIII Venice Biennale 1966 British Pavilion. London: British Council, 1966.

Curley, John J. A Conspiracy of Images: Andy Warhol, Gerhard Richter, and the Art of the Cold War. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2013.

Fried, Michael. “Art and Objecthood.” Artforum 5 (June 1967): 12–23.

McShine, Kynaston. Primary Structures: Younger American and British Sculptors. New York: Jewish Museum, 1966.

Mellor, David. The Sixties Art Scene in London. London: Phaidon, 1993.

Swenson, Gene. “Hybrid: A Time of Life.” Art and Artists 1, no. 2 (June 1966): 62–65.

Imprint

| Author | |

|---|---|

| Date | 18 July 2016 |

| Category | Article |

| Review status | Peer Reviewed (Editorial Group) |

| License | Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) |

| Downloads | PDF format |

| Article DOI | https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-03/jcurley-1960s |

| Cite as | Curley, John J. “Hybrid Sculpture of the 1960s.” In British Art Studies: British Sculpture Abroad, 1945 – 2000 (Edited by Penelope Curtis and Martina Droth). London and New Haven: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art and Yale University Press, 2016. https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-03/jcurley-1960s. |