Super-size Caricature

Super-size Caricature: Thomas Rowlandson’s Place des Victoires at the Society of Artists in 1783

Kate Grandjouan

Abstract

This article re-examines an ambitious caricature of the French that Thomas Rowlandson (1757–1827) exhibited in London in 1783. Recent research has confirmed that the artist undertook training at the Académie Royale in Paris while still a student at the Royal Academy in London. In the following essay, I argue that this double professional route into comic art can be related to his conception of the Place des Victoires. The broader context for this discussion is provided by several ideas that have been important to recent histories of British art, notably the rise of the public exhibition and the vigorous market for caricature prints. As what I call a “super-size” caricature, the drawing highlights how comic art could take on dimensions and appearances that suited exhibition contexts.

The Exhibition

In the late eighteenth century, comic art was a minor yet regular feature of London exhibitions. Its historic presence can be difficult to detect, however, because humour has a tendency to hide in other genres: the title of an exhibited work is not always indicative of its pictorial content or of the visual idioms deployed to render its subject. Nevertheless, there are some well-documented examples of a tradition that was initiated by William Hogarth (1697–1764) when he showed his satirical painting of Calais Gate at the second exhibition of the Society of Artists in 1761, long after it had been published as a print.1 Thereafter, John Collet (c. 1725–1780) established a reputation as a regular exhibitor of comic art, but there were certainly other artists too.2 Even at the Royal Academy humour could be included at the annual exhibition: Henry Bunbury (1750–1811) exhibited “caricaturas” of the French in the early 1770s, and the successful commercialization of these drawings as large satirical prints enabled the designs to reach a broader public.3 Ten years later, the theme was taken up by Thomas Rowlandson (1757–1827). His submissions to the Royal Academy included a pair of comic drawings comparing the English with the French, each of which was nearly a metre wide.4 As David Solkin and others have shown, the rise of public exhibitions in London encouraged artists to experiment and to diversify, and this was facilitated in turn by the evolution of the print market. Recent studies have explored how these changes impacted the development of the main exhibition categories (portraiture, landscape, and history painting), yet have given less attention to caricature, even though the facts indicate that the arrival of public exhibitions influenced the production and circulation of comic images too. Artists working with humour exploited new print markets, used exhibitions to advertise their skills, and embraced experimentation. Thomas Rowlandson’s Place des Victoires offers an interesting case in point (fig. 1).5

1

The drawing is of considerable size for a caricature (it measures 34.9 by 53.4 cm) and was exhibited by the Society of Artists in the spring of 1783. However, it is listed in their exhibition catalogue as a “stained drawing” and with a title, “La Place Victoire à Paris”, that suggests a carefully observed depiction of a celebrated square in France.6 The subject would have been instantly recognizable to an English viewer who had crossed the Channel. The Place des Victoires was distinguished by its elegant curved facades and a towering sculpture of “Louis le Grand”, depicting the French King being crowned by Victory. The statue had been designed by Martin Desjardins (1640–1694) and it was erected in the centre of a purpose-built square permanently illuminated by four gas lanterns.7 The King was cast in bronze and elevated on a large stone plinth decorated with medallions and long, laudatory inscriptions. Further down, around the base, four chained slaves visually referenced Louis XIV’s military victories over the “enemies of France”. This magnificent structure, inaugurated in 1686 in celebration of the Peace of Nijmegen, was both admired and reviled. In France it was reputed to be the largest royal monument ever made; for critics, however, it exemplified the idolatry of the Sun King, and from the late seventeenth century, both in Paris and further afield, the Place des Victoires had become a familiar target for anti-absolutist jokes.8

6Rowlandson’s stained drawing was one of four that he exhibited with the Society of Artists that year. This group of works pointed to heightened ambitions, for it was the largest number of drawings he had ever exhibited together.9 It was now just over ten years since he had entered the Royal Academy in 1772 to train as a painter, a professional commitment that he reinforced in 1775 when he moved to Paris to start a parallel course of training at the Académie Royale.10 By 1777, he was back in London and from 1778 he became a regular exhibitor of portrait sketches at the Royal Academy, albeit without much success. At a time when portraits accounted for nearly half of all exhibits and it was crucial to develop a distinguishing style or visual formula, Rowlandson’s submissions seem to have passed unnoticed. The only critical comment he managed to attract in the press was in 1780 for a Landscape and Figures, which was praised by a critic of the Morning Chronicle for containing “much humour”. The next time he exhibited was at the Society of Artists in 1783; the switch to an alternative venue and a sizeable comic drawing like Place des Victoires, suggests a new and consciously adopted strategy for public recognition.11

9As a professionally trained artist who was already an exhibitor at the Royal Academy, the Society’s exhibition offered Rowlandson a less prestigious venue for presenting art to the public, although in 1783 it may have presented key advantages for showing works on paper. The Society had been founded in 1760 as an independent association of artists, architects, sculptors, and engravers, and it quickly developed a reputation as London’s premier exhibiting society. But this was prior to the arrival of the Royal Academy and by the early 1780s it had difficulty competing, or even existing, as an alternative venue for the promotion of contemporary British art.12 There had been no exhibitions in 1779, 1781, or 1782, so 1783 marked the Society's return to the London scene. For the occasion the Directors rented the “Great Exhibition Room” in the Strand which had, when inaugurated in 1772, provided artists with the first purpose-built exhibiting venue in the capital.13 Consequently, all submissions would be displayed together in a spacious gallery that was well lit from above. These arrangements contrasted starkly with the Royal Academy’s: since its move to Somerset House in 1780, works on paper had been separated from the oils and relegated to a ground floor “Exhibition Room”, which artists had started to criticize for its poor lighting.14

12That the Society of Artists was offering a promising location to show drawings is suggested by their catalogue, in which works on paper accounted for at least a third of all exhibits, mostly “stained”, “tinted”, or “tinged” drawings as well as a mixture of pastels, chalks, bistres, and prints.15 In theory, stained or tinted drawings (the terms were interchangeable) were drawn in pen and monochromatic inks, and their lack of colour distinguished them from watercolours. In practice, however, the “stained drawing” was a loosely defined category: they were submitted to exhibitions by architects, engravers, and painters, and could present a variety of subjects.16 Stained or tinted drawings exhibited by the Society in 1783 included designs relating to architectural projects, numerous views of picturesque locations, Sketches, Ideas, a Landscape, and some genre pieces.17

15In the late eighteenth century, therefore, stained and tinted drawings depicted a range of subjects and were exhibited with varying degrees of finish. They were often displayed in public spaces because they had a commercial value as specimens which were shown to the public to convey accurate information about a forthcoming project, to invite collaborations, or to stimulate a sale. These purposes are confirmed by the additional information that some of the exhibitors supplied in the catalogue, such as notices that printed copies of the drawings would be available by subscription.18 The commercial functions of exhibited drawings, as market-oriented consumables that were shown to be bought, have been discussed by Greg Smith. As Smith notes, the final format of the intended reproduction (which was usually an aquatint) dictated the size of the prototype submitted for display. Furthermore, if the exhibited piece was destined to be copied, one of the purposes of a prominent black outline in a stained drawing or watercolour was to facilitate its replication: the line was the “matrix” that enabled the design to be traced, this linear method being just one of several used in late eighteenth-century London.19

18Place des Victoires evinces many of these standard functions. Looking closely, we find that a uniform grey tint has been applied to the topographical and figural elements, and that this tonal wash unifies the design. On the architecture it has been used to suggest clarity and accuracy and to provide for the appearance of identifiable edifices, like the towers of Notre Dame. On the figures, however, the monochromatic stain is combined with watercolour and the additional use of pen and black ink to draw over the top of the tint and colour with a pen. This strong black line gives the image its startling vitality and immediacy. Moreover, as it is applied to the sculpture and figures in the foreground, and not to the background, the King joins the lively procession of people who cross the square while the architectural facades look blank and undifferentiated.

Rowlandson’s tonal painting is used to map two graphic modes together: caricature sketching and topographic drawing, whose functions and values seem antithetical. Caricature signifies as a disruptive and imaginative line that forces satirical characterizations on the people depicted. It exaggerates facial features (noses, eyebrows, upturned noses), gives direction to hair and contour to bodies. As some of the figures are more caricatured than others and as their contours are never complete, their partial rendering in ink can produce passages of extreme sketchiness.20 The result is that the prominent black lines in Place des Victoires have not only become the reproductive cues for a print shop, but the signal to iconographies associated with caricature prints. At the same time, a degree of neat and careful observation has been used in the presentation of a grand Parisian square and its remarkable monument, or enough to conjure a convincing French setting for the caricatured depiction of a national group. In addition, the use of perspective, tonal modelling and carefully controlled coloured tints ask that this exhibition drawing be considered in relation to a set of aesthetic codes which were not typically applied to caricature sketches.21

20The following year Thomas Rowlandson started to exhibit similar drawings at the Royal Academy. In 1784 his submissions included Vauxhall and The Serpentine and in 1786 the enormous English and French Reviews (fig. 2). They were executed using the same pictorial formula: pen and black ink supplied caricature sketching while a combination of monochromatic stain and colour tints filled in the painted areas with alternative representational effects, helping to confer a level of finish consistent with their grand size and exhibited status.22 As the earliest of these comic drawings, Place des Victoires has been marginalized. Art historians usually describe it as a watercolour, which tends to diminish its humour. Rarely discussed and seldom exhibited, its significance as the first such piece to survive has been eclipsed.23

22

Arguably, however, it achieved some modest success because Place des Victoires was copied twice to produce three identical drawings. The image was also published as an expensive aquatint of slightly larger dimensions. William Holland sold one to the Prince of Wales for 10s. 6d., at a time when the average price for a caricature was 2s. to 7s., rising to a guinea for more complex works.24

24The existence of these reproductions suggests that the original exhibit fulfilled some of the commercial functions noted above. We could surmise that Rowlandson attracted a sale from a patron interested in acquiring a drawing for a portfolio, or an amateur with a taste for humour, in addition to its success in the print trade.25 Note that Rowlandson made Place des Victoires before he had established a professional reputation, even though he had started to publish satirical prints. Only a handful of dated designs predate the Society of Artists’ exhibition, yet thirty-three were issued in the year that followed, and more might reasonably be assigned to this period. The prints were issued by a range of London dealers, many during the Westminster Election (April 1784) when they were published as often as one per day.26 In addition to the stream of political satires, Rowlandson produced imitations and adaptations of Hogarth’s works. He published The Rhedarium, A New Book of Horses and Carriages in 1784, and started the Imitations of Modern Drawings, a collection of etchings after the drawings of modern masters that he would eventually publish as a set.27 In retrospect, we can see that the Society’s exhibition preceded the publication of greater numbers and varieties of designs which, over the course of a single year and within the dynamics of a busy print market, enabled the artist to establish a reputation as a versatile draughtsman and a sought-after copyist.

25Graphic Repertories

One of the few scholars to consider Place des Victoires in relation to the caricature print is Diana Donald. She described it in passing as an “inventive variation” of a type of “national subject” that she associated with William Hogarth and Henry Bunbury.28 In considering the relationship between Place des Victoires as an exhibited caricature and the satirical prints that it references, it is worth noting how its public display coincided with the rehabilitation of Hogarth as an important comic artist. By the 1780s “Hogarthomania” was in full swing, both fuelled by and reflected in a stream of publications. New editions of Hogarth’s engravings were circulating, some of his drawings were being published as prints, and at sales and auctions rare states of the artist’s work were reaching previously unheard of sums.29 One of the most important revisions of the painter’s reputation was provided by The Right Honorable Horace Walpole (1717–1797) in his Anecdotes of Painting in England, which had reached its third edition by 1782. Walpole did not consider Hogarth to be a great painter in the traditional sense but rather “a writer of comedy with a pencil” who had managed to catch “the manners and follies of an age living as they rise”.30

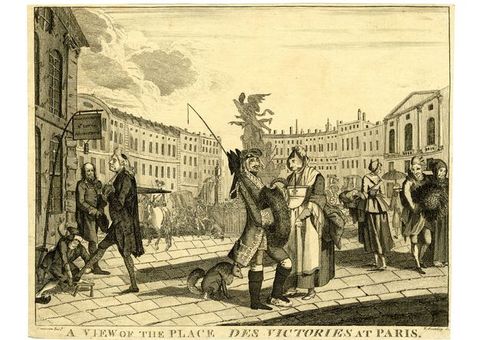

28“Hogarthomania” stimulated artists too. Among those renewing and updating the master’s comic legacies were the amateur artists, John Collet and Henry Bunbury, and professionals, some of whom were foreigners, such as Michel Vincent Brandoin (1733–1807) and his Swiss countryman, Samuel Hieronymus Grimm (1733–1794) and Philippe de Loutherbourg (1740–1812) the celebrated French academician active in London from 1772.31 De Loutherbourg published his Caricatures of the English (fig. 3) in 1776 and some of the paintings he exhibited at the Royal Academy injected caricature into colourful landscape settings. His “happy stile” was still much in evidence in the 1780s. Indeed, his submissions to the Royal Academy in 1784 prompted one critic to congratulate him as a “foreigner [who had] succeeded in expressing English humour. Excepting Mr Bunbury we have had no artist who made any figure with laughable subjects since Hogarth’s death.”32

31

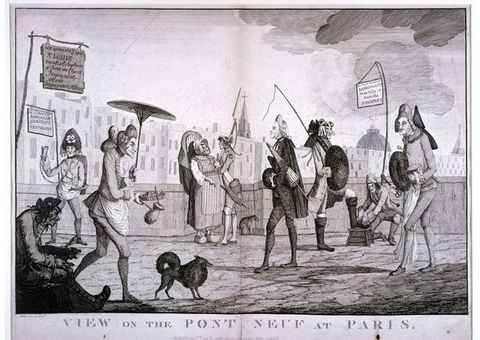

On the back of Hogarthomania, Henry Bunbury had risen to the height of his fame, and by the early 1780s he was considered to be the leading gentleman caricaturist. Walpole even advertised his Anecdotes with the promise of an essay on the “living etchings of Mr. Henry Bunbury”, describing the artist as “the second Hogarth . . . the first imitator who ever fully equalled his original”.33 Back in 1770, when Walpole had seen the original drawing of Bunbury’s La Cuisine de la Poste at the Royal Academy, he had annotated his exhibition catalogue with complimentary remarks about Bunbury’s French “characters” who he found “most highly natural”. “This drawing”, he noted, “perhaps excels the Gate of Calais by Hogarth, in whose manner it is composed.”34 The Cuisine de la Poste and View on the Pont Neuf (figs. 4, 5) which Bunbury exhibited in 1771 circulated in print throughout the 1770s, whereas in the 1780s Bunbury’s exhibition caricatures depicted English locations: Richmond Hill was shown at the Royal Academy in 1780 and Hyde Park in 1781. The drawings were issued as substantial prints. Hyde Park was published as a black-and-white caricature frieze composed of three printed sheets, each measuring half a metre in width.35

33

The appearance of Bunbury’s caricature drawings at the Royal Academy immediately precedes the presentation of Rowlandson’s Place des Victoires at the Society of Artists, and their large size and the urban themes they depict make them complementary. As publicly exhibited works that were destined for the print market the drawings indicate how resourceful caricaturists could be in adapting their materials for exhibition in London's fashionable West End. A drawn caricature usually meant a fast but ingenious sketch of a single figure or a simple group. These works, on the contrary, offered multi-figural comic narratives.36 Furthermore, if Rowlandson's French subject was modelled on a type of humour that had started with Calais Gate (fig. 6), the national subject had proliferated in print culture since Hogarth’s death. Collet, Brandoin, Grimm, and de Loutherbourg are among the better-known artists producing paintings, drawings, and prints with national themes, and their designs (like Bunbury’s too) diversified the sort of comic scenarios that could be meaningfully formulated for British viewers. Rather then starvation, invasion, and war, their subjects related to “genteel mania” and were frequently stimulated by the cross-Channel tourism that the Treaty of Paris of 1763 had made possible.37 Yet, if the activities of an eclectic group of artists point to a distinct vogue for national satire in the decade following Hogarth’s death, scattered remarks indicate how this type of subject was considered “low”. Francis Grose described national jokes as “stage tricks, [that] will always ensure the suffrages of the vulgar” in his Essay on Comic Painting (1780).38 This opinion even extended to Hogarth’s Calais Gate, for Walpole had made it clear in his Anecdotes that he considered Hogarth’s satires of the French to be examples of the artist’s unfortunate lapse in taste: “Sometimes too, to please his vulgar customers he stooped to low images and national satire, as in the two prints of France and England and that of the Gates of Calais. The last indeed has great merit though the caricatura is carried to excess.”39

36

For artists though, engaging creatively with “Hogarthomania” meant building on a well-known graphic legacy. Bunbury’s strategy was to reframe national humour as caricature sketching, a voguish activity that at the time was associated with the elite and the Grand Tour.40 The appeal of caricature lay in its humorous artlessness, the ironic “deskilling” of the professional skills that Royal Academy exhibitions were designed to showcase.41 In a similar manner, Rowlandson cross-fertilizes pictorial genres, but his mapping of humour onto foreign topography highlights, on the contrary, an ability to compose, use colour, and manipulate stain. As a caricature of a national group, it belongs to a vibrant local graphic culture and operates referentially, in the manner of a graphic satire.42 Yet as a sophisticated satire about a foreign square, Place des Victoires displays cosmopolitan credentials and the artistic skills on which it depends are closer to the virtuosity of the continentals. Brandoin, Grimm, and de Loutherbourg had trained in Paris yet they had emigrated to London where they operated across different artistic registers: sending drawings and paintings to exhibitions, inventing comic landscape subjects, designing graphic satires, and exploiting national humour. Understood within broader European pictorial legacies of the “national subject” therefore, Rowlandson’s Place des Victoires attached itself to a repertoire of national forms while demonstrating the new uses to which they could be put, “aestheticizing” them, a point that will become clearer when we confront Rowlandson’s comic view with its immediate graphic heritage.43

40This particular Parisian square had previously been the target of British graphic satire: it was the subject of a print designed by Charles Brandoin and published in July 1771 by two London dealers. A third was published by Matthew Darly the following year, although this brought minor changes to the artist’s name (fig. 7). The latter publisher issued the print again in 1776 in a bound edition of Darly’s Comic Prints. At the time, he was also selling one of the printed versions of Bunbury’s View on the Pont Neuf (fig. 5), and his simultaneous commercialization of the prints could only have enhanced their striking visual duplications.44 In both designs, the French settings are used simply, and are only recognizable by the printed titles. Indeed, in Brandoin’s rendering the comic sabotage starts with the anglification of the name—“Victoire” has become “Victories”—and as the sculpture, like the architectural facades, recedes into the distance, the square is no more than a scratched out setting for the principal focus: the set of louche French characters distributed across the shallow foreground, who signify the alien qualities of a foreign land.

44

At first glance, the differences seem too significant for us to align Rowlandson’s Place des Victoires with the earlier satiric view: in place of Brandoin’s rough approximations, Rowlandson’s drawing features a degree of topographic accuracy. This starts with the correction of the name, and continues with the appearance of recognizable architecture; scale has become significant (the drawing is nearly double the size of the print) and colour has been introduced. Along with the more convincing depiction of a Parisian square is the greater diversity of national types that overall produces a French crowd. On close examination, however, we find identical characters that connect the two designs. The lawyer, for instance, who is dressed in black and seen on the left of Brandoin’s satirical print reappears in Rowlandson’s drawing. He still carries a folded umbrella but also an over-sized muff, a detail which in the print belongs to the coachman and to the hairdresser on the far right, standing close to a bare-footed friar. This particular visual reference to the church has been retained by Rowlandson, while the coachman has been moved to the left, close to the statue of the King.

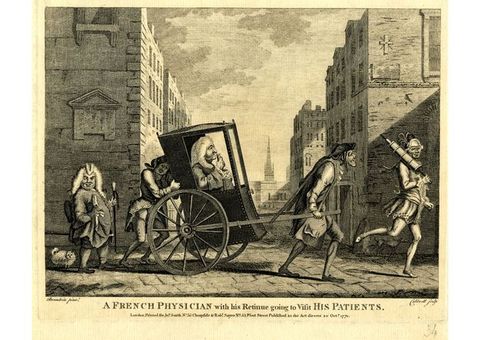

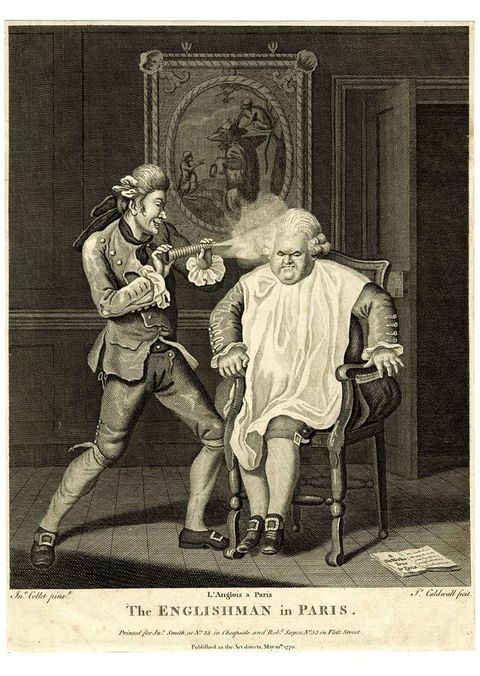

The recycling of existing printed sources extends to other graphic satires too. Rowlandson’s spindly servant taking comically large strides resembles the postilion in Bunbury’s La Cuisine de la Poste (fig. 4) although his actions are more closely related to a figure in Brandoin’s A French Physician (fig. 8).45 Even the dogs are borrowed from other sources, as is the couple on the far right who have paused to take in the square. This man’s corpulence along with the particular style of his hair makes him immediately reminiscent of Collet’s Englishman in Paris (fig. 9).46 In Rowlandson’s drawing, this visual code is reinforced by the appearance of the woman at his side wearing riding dress, turning the two into an English pair. Prints of French and English tourists had become a subject of graphic satire in the early 1770s, so it is not surprising that the appearance of an English couple on the right is matched by the French couple on the left; the “French Lady” even turns to look back in their direction, adjusting her hat, or touching her hair.47

45At the most explicit level of meaning, this visual referencing becomes a source of pleasure, in that the accumulation of nationally specific material furnishes a variety of mini-narratives. As the raiding of existing prints produces new episodes for familiar characters, the complexity of the recycled image plays upon recognition and an awareness of visual displacement. Viewing is undirected and freely creative for it operates in a way that flatters the viewer, encouraging him or her to find new connections and to recognize witty transformations. Furthermore, if the image is sharing a set of nationally specific forms at a more general level the design is repeating some of the tropes that were a feature of eighteenth-century nationalist texts, and their appearance together helps explain the organization of the imagery. Thus we see the predictable reference to a symbol of Catholic authority (in the looming towers of Notre Dame), or to the association of absolutism and slavery (in the statue of the King), or to the intertwined and mutually dependent figures of the French state (the throngs of soldiers and the processions of monks). Even “apishness” (the dog who dances like his master), “airiness” (the effeminate King), and “trampled under foot” provide visual cues to contemporary national jokes, their visual repetition reinforcing the stability of local English stereotypes for the French.

One way of understanding the process we are witnessing here—the selection and adaptation of existing sources and their transformation into an ambitious caricature of the French—would be in terms of Rowlandson’s academic training, as a display of skills that have been acquired in one type of pictorial practice and which have been transferred to another.48 The artist’s passage through the Académie Royale in Paris has recently been confirmed with a date, stimulating fresh scrutiny of the social and professional networks to which he may have belonged.49 Rowlandson's publicly exhibited drawings encourage fresh scrutiny too. Caricature was not just an amateur practice dominated by gentlemen artists, but a cosmopolitan mode of witty draughtsmanship with deep roots in Academy circles.50 In addition, a double professional training by two national Academies, where the teaching programmes converged, gave him privileged access to royal and private collections. It took him to conférences, life classes and méthodes de dessin, and to a curriculum where drawing was considered to be the foundation of an artist’s training, and where “rule” and “theory” were looked upon as one’s carte fidèle.51

48More specifically, at the Academy “invention” meant the interpretation of established sources, and this idea is illustrated in one of the central texts of academic doctrine in the eighteenth century, and on both sides of the Channel, Alphonse du Fresnoy’s De L’Art Graphique. The text was translated into English in 1715 and reissued in Britain on several occasions, notably in 1769 and in 1783. The novelty of the latter translation was that it incorporated annotations by the President of the Royal Academy, Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792). His comments were subsequently translated into French and published in 1787. In addition, a new version of Du Fresnoy’s text sponsored by the Académie Royale would be published in Paris in 1789.52

52According to Du Fresnoy, the first task of the enterprising artist was to find a suitable subject for painting. His “chief business” was then to execute the subject in a manner that would arouse the appropriate response in the spectator, not by copying from nature but by “culling” the most perfect forms from “the sublime arts of the past”. For “there is no better course”, adds Reynolds in the notes to this section, but that “the Artist may avail himself of the united powers of all his predecessors. He sets out with an ample inheritance, and avails himself of the selection of ages.”53 Of course in the Academy, this understanding of artistic invention as the reinterpretation of established subjects realized by copying from a stock of the best artistic examples of the past was an intellectual process, conceived in relation to history painting. What Rowlandson seems to be doing is transferring the method to the invention of an alternative subject. He has adopted two idioms suitable to the execution of his theme (stained drawing and caricature) and has accumulated a stock of satirical images which will provide the general idea of things—the postures, traits, and types—that were required to produce a comic image of a French group. As he moves down from the “general store” to find the particulars he wants to express, he is selecting, combining, and inventing to “new-cast the whole”, or, to quote Reynolds again, “passing them [i.e. the borrowed forms] through his creative imagination [and] Transforming, for he is bound to follow the ideas that he has received, [and] translate[s] them (if I may use the expression) into another art. In this translation the Painter's Invention lies.”54

53French Jokes

In her detailed study of the caricature print market in late eighteenth-century Britain, Diana Donald drew attention to the appearance in the early 1780s of a new type of political satire that responded to the patronage of elite social groups. The designs in question dispensed with some of the traditional paraphernalia of the caricature print such as the textual annotations and verbal keys that facilitated comprehension. Instead, the prints looked more pictorial, their humour was framed through intellectual allusions (to history or to literature) or via formats that parodied Academy paintings.55 As the decade progressed, this type of sophisticated graphic satire would become increasingly associated with James Gillray (1756–1815) and his burlesques of the “high stile” of British painting. Indeed, Mark Hallett has described a “counter-culture” developed around the Academy composed of professionally trained artists whose “complex and technically assured images” offered “an ironic echo of the artistic hierarchies in place at the Academy”.56 It is this contemporary trend that provides a broader context for understanding the appearance of an ambitious caricature at the Society of Artists, wherein humour—specifically achieved via the recognition of visual incongruity—is generated in a similar way, via intertextual allusion and parody.

55By incongruity I mean not just the impossible view of Notre Dame immediately behind the Place des Victoires, or the abrupt switches in scale which make the English man and woman on the right seem enormous in relation to the French monks behind, but also the incongruity that comes from the expansion in scale of a pen and ink caricature sketch. The large size of Place des Victoires suggests that it is a parody, a “play upon form”, where the artist has appropriated a pictorial idiom that was printed and widely available and turned it into a commodity more precious and rare.57

57Of course, the comic resonance of parody depends on a “consciousness of style”, on the recognition that visual idioms that were familiar in one context could be displaced and recast for another.58 If we can see the exhibition drawing as a giant caricature sketch, we could also understand its humour the other way around and in relation to an alternative category of imagery altogether; as a pictorial joke on the iconography of military victory, or a comic Triumph cast in a Parisian setting that was celebrated for its commemorative functions. In the late eighteenth century, London had a famous set of Triumphs (1484–82), which had been painted by Andrea Mantegna (c. 1431–1506) and were kept on permanent public display in the Queen’s Drawing Room at Hampton Court Palace. A contemporary guide-book carried a full description and considered them to be among “the best” of Mantegna’s works (fig. 10).59

58

To reread Rowlandson’s Place des Victoires as a parody of a “Triumph” is to see Rowlandson’s characters comically trapped within its circular architectural space and condemned to travel endlessly around the statue of their King, who is dressed like Mantegna’s Caesar, à l’antique, and is likewise crowned by Victory, although not for the defeat of Gallica. This playful allusion would also allow us to retrieve the topical appearance of a national subject at the Society of Artists in the spring of 1783. Peace with France had only recently been declared, putting an end to the American war that had started in 1778. The definitive Treaty of Versailles would not be signed until September, although a provisional agreement had been ratified in January 1783, halting hostilities and stimulating the return of more peaceful ones. Borders had reopened and travel to Europe was possible again.60

60Conclusion

I have used Place des Victoires to explore the pictorial status of a comic drawing in a public exhibition and in relation to some of the themes that have been important in recent histories of British art. On the one hand, there is the exhibition and its contexts of “competitive individuation” and emulation.61 On the other, there is the vigorous market for caricature prints, although scholarship has mostly been concerned with the social and political implications of their status as a widely disseminated form.62 By the 1780s, caricature featured prominently in the print shops yet it was less visible in the exhibition catalogues of the period—or at least, hard to detect—and this is one of the reasons why Place des Victoires is so interesting. The very act of placing a “super-size” caricature in a Society exhibition, of seeing it framed and displayed on the wall, means that it was defined (for its initial audiences at least) as a public painting. To investigate its status as exhibited art highlights the contemporary elasticity of the “stained drawing” category; to consider it as a humorous image emphasizes its flexibility, as well as the ability of caricature to fuse with alternative representational effects. The national subject may have been considered “low” and “vulgar”, nonetheless Rowlandson’s drawing suggests that if the modality of inscription was changed, a comic image of the French could actually become the means for displaying a set of acquired artistic skills. By taking a set of recognizable national characters and demonstrating the new uses to which they could be put, an unknown artist might seek to establish his hand and become a name.

61% contributors context=pageContributors format=‘bio’ align=‘left’ %}

Acknowledgements

A big thank you to the anonymous readers for their helpful suggestions on an earlier draft and to the editors at the Paul Mellon Centre for their help in preparing the essay for publication. The material in this essay was first presented at a Research Seminar at the Courtauld Institute of Art and I am grateful to the participants—professors and students—for their input.

About the author

-

Kate Grandjouan is currently working as an independent scholar and writing a book provisionally entitled Anglo-French Encounters: National Identity and Graphic Satire 1688-1815. Her research interests mostly focus on satire, humour and national jokes; on early modern print culture, material culture and cross-channel exchange. She gained her doctorate from the Courtauld Institute in 2010. She was a visiting lecturer and is now a summer school lecturer for eighteenth-century British art. For her publications of articles, book reviews in Eighteenth-Century Studies and reviews for the British Society of Eighteenth-Century Studies.

Footnotes

-

1

Painted in 1748, published in 1749, and exhibited as no. 44, The Gate of Calais. See A Catalogue of the Pictures, Sculptures, Models, Drawings and Prints &c, Exhibited by the Society of Artists of Great-Britain (London, 1761). The painting is now in Tate Britain; see http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/hogarth-o-the-roast-beef-of-old-england-the-gate-of-calais-n01464. For a copy of the print in the British Museum (hereafter “BM”), see BM3050. For an account of this first exhibiting society, see Matthew Hargraves, Candidates for Fame: The Society of Artists of Great Britain, 1760–1791 (New Haven and London: Yale Univ. Press, 2006). ↩︎

-

2

Collet exhibited over forty pieces between 1760 and 1783 with the Free Society. See Caitlin Blackwell, “John Collet (ca 1725–1780): A Commercial Comic Artist” (PhD, University of York, 2013), Appendix III. A trawl through the exhibition catalogues yields suggestive titles prior to 1783. At the Society of Artists, for example: “The Italian and British Quack Doctors” (1769), “The Amorous Old Beau” (1772), and “The Procuress” (1775). At the Free Society: “The Hen peckt husband after Mr Dawes” (1768), “The French Hairdresser Discovered” (1771), “The Frenchman’s Arrival at Dover in Aqua Tinta” and “The Amorous Admiral, on a Look-out Cruize” (1783). Photocopies of the catalogues are kept by the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, London. ↩︎

-

3

Some of the drawings, including a La Cuisine de la Poste are held by the Lewis Walpole Library in Connecticut. It measures 44.5 x 44.7 cm (sheet) and may correspond to the drawing exhibited in 1771, see http://images.library.yale.edu/walpoleweb/oneitem.asp?imageId=lwlpr15204. John Harris issued one of the prints (see BM4764; 41.1 x 44 cm, sheet). Other French subjects exhibited by this artist included A Courier François (1769), A View of the Pont Neuf at Paris (1771), and A Tour to Foreign Parts (1777). For printed versions, see BM4737, BM4918, and BM4732. The contemporary reference to “caricaturas” is from John C. Riely, “Horace Walpole and ‘the Second Hogarth’”, Eighteenth-Century Studies 9, no. 1 (Autumn 1975): 28–44. ↩︎

-

4

The Reviews were exhibited in 1786 and are reproduced by Kate Heard in High Spirits: The Comic Art of Thomas Rowlandson (London: Royal Collection Trust, 2015), cat. nos. 16 and 17. Each sheet measures c. 50 x 90 cm. Algernon Graves, The Royal Academy of Arts: A Complete Dictionary of Contributors and their Work from its Foundation in 1769 to 1904 (Bath: Kingsmead Reprints, 1970), lists twelve Rowlandson submissions between 1784 and 1787. They included An Italian Family, A French Family, and The French Barracks, all of which were published. The Serpentine and Vauxhall remain the best known of these works. For details, see John Hayes, The Art of Thomas Rowlandson (Alexandria, VA: Art Services International, 1990), cat. nos. 19 and 20. Between Bunbury and Rowlandson there were other comic pieces; among the French subjects were A French Kitchen (1777), A French Family (1778), and probably some of the works inspired by Laurence Sterne’s A Sentimental Journey through France and Italy (1768), such as Le Patessier or Patty-man vid. Yorrick’s Sentimental Journey in 1775. ↩︎

-

5

For developments stimulated by the arrival of the public exhibition, see David Solkin, Painting for Money: The Visual Arts and the Public Sphere in Eighteenth-Century England (New Haven and London: Yale Univ. Press, 1992), 247–76, and the different essays in David Solkin, ed., Art on the Line: The Royal Academy Exhibitions at Somerset House, 1780–1836 (New Haven and London: Yale Univ. Press, 2001). The field has since broadened and a comprehensive list of relevant studies can be found in the bibliography to David Solkin, Art in Britain, 1660–1815 (New Haven and London: Yale Univ. Press, 2015) accessible at https://issuu.com/yalebooks/docs/solkin_biblio_and_index__1_ . In addition to the works mentioned above, this essay draws on the scholarship of Greg Smith, The Emergence of the Professional Watercolourist: Contentions and Alliances in the Artistic Domain, 1760–1824 (Farnham: Ashgate, 2002); Hargraves, Candidates for Fame; David Solkin, ed., Turner and the Masters (London: Tate Publishing, 2009); Rosie Dias, Exhibiting Englishness: John Boydell’s Shakespeare Gallery and the Formation of a National Aesthetic (New Haven and London: Yale Univ. Press, 2013); Sarah Monks, John Barrell, and Mark Hallett, eds., Artistic Ideals and Experiences in England, 1768–1848, (Farnham: Ashgate, 2013) and Mark Hallett, Reynolds: Portraiture in Action (New Haven and London: Yale Univ. Press, 2014). For an important early discussion of Rowlandson’s comic drawings in the context of the public sphere, see John Barrell, “The Private Comedy of Thomas Rowlandson”, Art History 6, no. 4 (1983): 422–41, reprinted in The Birth of Pandora and the Division of Knowledge (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1992), 1–25. ↩︎

-

6

The drawing is at the Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, where it is catalogued under its more familiar name, Place des Victoires, pen, stain, and watercolour over pencil, 34.9 x 53.4cm (sheet): http://collections.britishart.yale.edu/vufind/Record/1670067. I will use the YCBA version of the title throughout this essay. Three are known to have existed. Hayes, Art of Rowlandson, cat. no. 17, dates this one to 1783 and on the basis of style suggests that it may have been the exhibited piece. For the exhibition listing, see A Catalogue of the Pictures, Sculptures, Models, Designs in Architecture, Prints &c (London, 1783), no. 223. By the 1780s, the average size of a caricature print was c. 25 x 35 cm. Heard, High Spirits, provides plenty of examples. ↩︎

-

7

The iconographic scheme is described in François Souchal, French Sculptors of the 17th and 18th Centuries: The Reign of Louis XIV, Vol. 1 (London: Cassirer, 1977), cat. no. 44. For a lavishly illustrated account of the monument’s construction and reception, see Hendrik Ziegler, Louis XIV et ses Ennemies: Image, Propagande et Contestation, translated into French by Aude Virey-Wallon (Paris: Centre allemande d’histoire de l’art, 2013), 94–147. The monument was largely destroyed during the Revolution. ↩︎

-

8

See Zeigler, Louis XIV et ses Ennemies, 123–28, with an emphasis on its critical reception in Protestant countries and Huguenot literature. The “anti-absolutist” joke is noted by Malcolm Baker in The Marble Index: Roubiliac and Sculptural Portraiture in Eighteenth-Century Britain (New Haven and London: Yale Univ. Press, 2014), 28. ↩︎

-

9

The other three were An Inn Yard at Stratford Upon Avon, Country People Regaling after Work, and The Prodigal. They were grouped together as stained drawings and remain untraced today. ↩︎

-

10

For the biographical detail in these years, see Matthew Payne and James Payne, Regarding Thomas Rowlandson, 1757–1827: His Life, Art and Acquaintance (London: Hogarth Arts, 2010), 19–70. ↩︎

-

11

Seven submissions were made between 1777 and 1781 of which five were portraits. None survive, although their numbering in the catalogues suggests that they were works on paper. For a wide-ranging discussion of the small number of extant drawings that precede the Place des Victoires, see John Riely, “Rowlandson’s Early Drawings”, Apollo 117, no. 251 (Jan. 1983): 30–39, and John Hayes, The Art of Thomas Rowlandson (Alexandria, VA: Art Services International, 1990), cat. nos. 1–16. The competitive dimensions of portraiture in this context are discussed by Marcia Pointon in “Portrait! Portrait! Portrait!”, in Art on the Line, ed. Solkin, 93–109, and in Hallett, Reynolds, 253–83. The critical appraisal is quoted in Payne and Payne, Regarding Thomas Rowlandson, 42. ↩︎

-

12

On this bitter rivalry, see Solkin, Painting for Money, 259–76; for a detailed account of their subsequent demise and the difficult context surrounding the 1783 exhibition, see Hargraves, Candidates for Fame, 151–61; on the foundation of the Academy in 1769 and its organization, see Holger Hoock, The King’s Artists: The Royal Academy of Arts and the Politics of British Culture, 1760–1840 (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 2003), 19–51. ↩︎

-

13

It had actually been built by the Society, but for financial reasons they were forced to sell it in 1776. For a description with illustrations, see Hargraves, Candidates for Fame, 117–26. ↩︎

-

14

Prior to 1780, the Academy’s exhibitions were held in a single room in Pall Mall, see Solkin, Painting for Money, 257, for a contemporary reproduction. On the tensions generated among artists by new arrangements, see Dias, Exhibiting Englishness, 17–63, and for the implications of this relocation for works on paper, see Greg Smith, “Watercolourists and Watercolours at the Royal Academy, 1780–1836”, in Art on the Line, ed. Solkin, 194–200; and Smith, Emergence of the Professional Watercolourist, 23–33. ↩︎

-

15

See Catalogue (1783), where 102 of the 345 works are described in these terms; there were possibly more because the medium is not always designated. ↩︎

-

16

For definitions and uses in the period, see Smith, Emergence of the Professional Watercolourist, 17–23. ↩︎

-

17

Examples from the Catalogue (1783) include: nos. 4–8: Mr John Melchor Barralet, five “stained drawings” of Scenes in Surry [>sic.]; no. 34: Mr Backhouse, “Design for a Villa, stained drawing”; nos. 55–68: Mr R. Cooper, a group of “tinted drawings” that included six Views of Italy; nos. 84–89: Mr C. Ebdon, a group of “stained drawings” including Design for a Temple, Remains of the Temple of Jupiter Stator, and Designs for Lodges to Tehidy Park, Seat of Sir Francis Basset, Bart; and nos. 126–28: Mr S. Howitt, Stag Hunting and Fox Hunting, listed as “stained drawings”. ↩︎

-

18

See Catalogue (1783), nos. 109–14, for drawings relating to “the Publication of the Antiquities of Great Britain”, or no. 286, a drawing from the “Picturesque Beauties of Shakespeare . . . now publishing by Subscription”. Exhibition functions are discussed in Smith, Watercolourists and Watercolours, 195–200. For an account of “finished” and presentation drawings and their operation in a public space, see Deanna Petherbridge, The Primacy of Drawing: Histories and Theories of Practice (New Haven and London: Yale Univ. Press, 2010), 50–85. ↩︎

-

19

The term is used by Smith in his discussion of the different copying methods in use in Emergence of the Professional Watercolourist, 51–71. ↩︎

-

20

“Subversive” from Deanna Petherbridge’s chapter on caricature, “Charged Lines and Vernacular Bodies”, 347–77 in The Primacy of Drawing. The author gives a historical overview of caricature, effectively highlighting the values that have been attached to it as “ephemeral satirical commentary, or as an expression of the grotesque and the carnivalesque” (348). ↩︎

-

21

The dimensions of the Place des Victoires are the same as those of tinted drawings with genre or topographical subjects displaying a high degree of finish. For contemporary examples, see Scott Wilcox, ed., The Line of Beauty: British Drawings and Watercolors of the Eighteenth Century (New Haven: Yale Center for British Art, 2000), cat. no. 91 (Francis Wheatley, Donnybrook Fair, 1782, 32.2 x 54.6 cm); no. 95 (William Marlow, Nîmes from the Tour Magne, c. 1765–68, 36.5 x 53.3 cm); and no. 100 (William Pars, A View of Rome, 1776, 38.4 x 53.7 cm). The stylistic dichotomy in the drawing is noted as an unresolved tension between the “pretty” or “elegant” and “the comic” or “exaggerated” that would later be resolved. See André Paul Oppé, Thomas Rowlandson: His Drawings and Water-colours (London: The Studio, 1923), 7; Hayes, Art of Rowlandson, 16–17, cat. no. 17; and Riely, “Rowlandson’s Early Drawings”, 37. ↩︎

-

22

For a discussion of this Academy period, see Payne and Payne, Regarding Thomas Rowlandson, 71–109. There were three submissions in 1784, five in 1786, and four in 1787, although the authors suggest more were presented under pseudonyms. Some of the drawings exist as multiples and the published aquatints are of similar dimensions, see Hayes, Art of Rowlandson, cat. nos. 19, 20, and 33. The most substantial were Vauxhall, The Serpentine, and the Reviews. There are also large comic drawings that were not exhibited: George III and Queen Charlotte Driving through Deptford (c. 1785, 41.9 x 70.5 cm), reproduced in Hayes, Art of Rowlandson, cat. no. 22; or The Prize Fight (c. 46 x 69.5 cm), in Wilcox, ed., Line of Beauty, cat. no. 89. For the Reviews, see Heard, High Spirits, note 4 above. ↩︎

-

23

See mainly John Hayes, Thomas Rowlandson: Drawings and Watercolours (London: Phaidon, 1972), 32, and Hayes, Art of Rowlandson, 16 and cat. no. 17 and Riely, “Rowlandson’s Early Drawings”. Hayes situated the drawing in a “transitional period” which he found difficult to reconstruct because of the lack of biographical information, but which paved the way for the “great watercolours” like Vauxhall that followed at the Royal Academy. Riely connected the work to British drawings but not to satirical prints. For the direction of satiric print culture, see mainly Diana Donald, The Age of Caricature: Satirical Prints in the Reign of George III (New Haven and London: Yale Univ. Press, 1996), 132. Donald, Hayes and Riely were writing at a time when the Parisian training had become a rumour; if French “influences” are acknowledged, they prioritize Rowlandson’s stylistic affinities with British artists. Different versions of the drawing have been occasionally exhibited: in 1984, see Richard Godfrey, English Caricature: 1620 to the Present (London: Victoria & Albert Museum, 1984), cat. no. 83; in 1990, see Hayes, Art of Rowlandson, cat. no. 17; and in 2000 by the Yale Center for British Art, see Wilcox, ed., Line of Beauty, cat. no. 86. ↩︎

-

24

Hayes, Art of Rowlandson, cat. no. 17 reproduces one of the other drawings. The aquatint was published in November 1789 (see BM9679). The reference to the Prince of Wales comes from Heard, High Spirits, cat. no. 110, which reproduces a copy: 44 x 61.5 cm (print, plate) to 34.9 x 53.4 cm (drawing, sheet). For prices of caricature prints, see Timothy Clayton, “The London Printsellers and the Export of English Graphic Prints”, in Loyal Subversion? Caricatures from the Personal Union between England and Hanover (1714–1837), ed. Anorthe Kremers and Elisabeth Reich (Gottingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2014), 152. ↩︎

-

25

Amateurs collaborated with professionals to get their drawings published and generally played an important role in turning caricature into a fashionable printed medium; see Donald, Age of Caricature, 14, 35, 60–67. That Rowlandson instructed amateurs in drawing and frequently engraved their designs is noted by Payne and Payne in Regarding Thomas Rowlandson, 87, 92–93. See Smith, Emergence of the Professional Watercolourist for an analysis of drawings in relation to patrons and commercial markets. Caricature drawings could also be given as gifts. Donald, Age of Caricature, 221, note 133, records how Bunbury gave his humorous drawing of Richmond Hill, exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1780, to Horace Walpole. ↩︎

-

26

Heard discusses the early printmaking in High Spirits, 13–24, and gives examples: see cat. nos. 1–14. I am grateful to Nicholas J. S. Knowles who is compiling a catalogue raisonné of Thomas Rowlandson’s works, for the figures quoted above. He estimates that sixty-five could be assigned to this period (simply indicative, running from the end of the Society’s exhibition to the beginning of the Academy’s). The majority are non-satirical and some belong to projects that would continue for several years, so a cautious number would be lower. By 1784 the publishers included Elizabeth Bull, Thomas Corneille, Elizabeth d’Archery, Samuel Fores, William Humphrey, Hannah Humphrey, John Hanyer, and John Raphael Smith. Payne and Payne, Regarding Thomas Rowlandson, 71–95, give a good sense of the artist’s busy life immediately after the Society’s exhibition. ↩︎

-

27

For a Hogarth adaptation, A Sketch from Nature, published in 1784, see BM6719. Rowlandson’s Tour in a Post Chaise, carried out in the spirit of Hogarth's Peregrination (1732) in April 1784, generated sixty-eight drawings, although they were never published; see Robert Wark, Rowlandson’s Drawings for a Tour in a Post Chaise (San Marino, CA: Huntington Museum and Art Gallery, 1963). He had already copied Hogarth’s Peregrination drawings in 1781, possibly in connection with one of the projects to bring them to publication; see Payne and Payne, Regarding Thomas Rowlandson, 57. For the Rhedarium and the Imitations see Payne and Payne, Regarding Thomas Rowlandson, 79 and 82–86; 127–28. ↩︎

-

28

Donald, Age of Caricature, 130, 132 with a reproduction. The catalogue description for this drawing notes how the design is “repeating national stereotypes”: http://collections.britishart.yale.edu/vufind/Record/1670067. ↩︎

-

29

“Hogarthomania” is a contemporary term, and is quoted by Sheila O’Connell in “Hogarthomania and the Collecting of Hogarth”, in David Bindman, Hogarth and his Times (London: British Museum Publications, 1997), 58–60. Two drawings (Mr Gabriel Hunt and Mr Ben Read) were published by Jane Hogarth in November 1781 and an edition of the Peregrination was published in 1782. For sales, see Timothy Clayton, The English Print, 1688–1802 (New Haven and London: Yale Univ. Press, 1997), 232–33. On the development of Hogarthian prints, books, ceramics, and so on, see David Brewer, “Making Hogarth Heritage”, in Representations 72 (Autumn 2000): 21–63, a subject that has been revisited recently in Cynthia Ellen Roman, ed., Hogarth’s Legacy (New Haven and London: Yale Univ. Press, 2016). ↩︎

-

30

Quoted from Bindman, Hogarth, 13–14. On the significance of this reappraisal, see also Donald, Age of Caricature, 34. ↩︎

-

31

For Brandoin and Grimm, see William Hauptman, “Beckford, Brandoin and the ‘Rajah’: Aspects of an Eighteenth-Century Collection”, Apollo 143, no. 411 (May 1996): 30–39, and Hauptman, Samuel Hieronymus Grimm (1733–1797): A Very English Swiss (Bern: Kunstmuseum, 2014). Both had trained as topographical artists in Paris before moving to London in the 1760s. Also, both exhibited landscapes at the Society of Artists and the Royal Academy, and Grimm’s were occasionally humorous. They published satirical prints with Anglo-French subjects, some of which are noted below. A recent account of de Loutherbourg’s activities in England is provided in Iain McCalman, “Conquering Academy and Marketplace: Philippe de Loutherbourg’s Channel Crossing”, in Living with the Royal Academy, ed. Monks, Barrell, and Hallett, 76–88. ↩︎

-

32

From the Haymarket, hand-coloured etching from the Caricatures of the English, see BM5361. The set was composed of six prints, three of which are reproduced in Constance C. McPhee and Nadine M. Orenstein, eds., Infinite Jest: Caricature and Satire from Leonardo to Levine (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2012), cat. nos. 33–35. For the comic paintings (some of which were copied into print), see Olivier Lefeuvre, Philippe-Jacques de Loutherbourg (Paris: Athena, 2012), cat. nos. 128, 132, 136 and 138 (quote, 242); although Anne Puetz, “Foreign Exhibitors and the British School at the Royal Academy, 1768–1823”, in Art on the Line, ed. Solkin, 229–43, notes how, as a foreigner, his critical reputation would soon decline. ↩︎

-

33

Riely, “Horace Walpole”, 36. ↩︎

-

34

Riely, “Horace Walpole”, 32. ↩︎

-

35

La Cuisine was published by several dealers in different editions and sizes; see BM4764 and the Lewis Walpole Library, Connecticut, for examples. The View on the Pont Neuf was published in two sizes in 1771 (see BM4763 and BM4918). Figures from both designs were issued as individual prints (see BM4782 and BM4679). On seeing Richmond Hill displayed at the Royal Academy, Horace Walpole described it as “a most capital drawing” (Riely, “Horace Walpole”, 36). It is now at the Lewis Walpole Library, Connecticut. For the print measuring 46.5 x 75 cm, see BM6143 (1782); Hyde Park, see BM5925–7 (1781), each sheet c. 52 x 61.5 cm. A large burlesque of St James’s Park was published in 1783 (see BM6344). ↩︎

-

36

See Dias, Exhibiting Englishness, 23–24, for emphasis on the fashionable locations of the different venues. Petherbridge, Primacy of Drawing, 348, notes how caricature drawings fall into one or other of these categories (i.e. as sketches of single figures that were “speedily produced . . . by the deliberate adoption of strategies of deskilling and infantilism” or as “more complex and public narratives that parody social or political situations and personalities”), but what seems to be happening in England around 1780 is that they were merging. ↩︎

-

37

On the importance of the 1770s and the contribution of Brandoin and Grimm, see my “Close Encounters: French Identities in English Graphic Satire, c.1730–1790” (PhD thesis, Courtauld Institute of Art, 2010). There were also a considerable number of anonymous designs with French or Anglo-French subjects published during the period. See Donald “‘Struggles for Happiness’: The Fashionable World” in her Age of Caricature, 75–93 for the broader context in satirical print publishing to which they belong. ↩︎

-

38

Francis Grose, Rules for Drawing Caricaturas with an Essay on Comic Painting (London, 1788), 32. ↩︎

-

39

Horace Walpole, Anecdotes of Painting in England, Vol. 4, 4th edn. (London, 1796), 157. “France” and “England” refer to a pair of satirical etchings published soon after the outbreak of war with France in 1756 (see BM3446 and BM3454). By the time the Anecdotes was published, Hogarth’s national satires had become familiar as black-and-white illustrations that were bound into books and given extensive commentaries that reinforced their moral functions. See, for example, John Trusler’s Hogarth Moraliz’d (London, 1768) and Brewer, “Making Hogarth Heritage” on this development. ↩︎

-

40

For an account of the aristocratic and foreign roots of British caricature and the important role that amateur artists played in maintaining this association, see Donald, Age of Caricature, 9–18, 35, 94–95. Mary Darly had recommended caricaturing to ladies and gentlemen as an entertaining and leisurely diversion in A Book of Caricaturas on 60 Copper Plates in that Droll and Pleasing Manner (London, 1762), 117. Bunbury completed his Grand Tour in 1769–70 and this included studying drawing in Rome, see Riely, “Horace Walpole”, 31. ↩︎

-

41

See Petherbridge, Primacy of Drawing, 348 for “deskilling” in relation to normative drawing practice. ↩︎

-

42

On visual satire’s allusiveness, see Mark Hallett, “James Gillray and the Language of Graphic Satire”, in James Gillray: The Art of Caricature, ed. Richard Godfrey (London: Tate Publishing, 2001), 23–39. ↩︎

-

43

“Aestheticizing” here meaning “taking it out of moral discourse (the low, mean, judgemental) and placing it within an aesthetics of pleasurable response, of sympathetic laughter and comedy”; see Ronald Paulson, Don Quixote in England: The Aesthetics of Laughter (Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, 1998), xii. Rowlandson has frequently been presented as a close imitator of Bunbury, notably by Hayes, Drawings and Watercolours, 48–49; Riely, “Horace Walpole”, 42–44; and Donald, Age of Caricature, 35, 94–95. The ability to colour was considered a professionally acquired skill: see Smith, Emergence of the Professional Watercolourist for the evolution of distinctive practices by professional draughtsmen and watercolourists in their bid to distinguish themselves from amateurs in the late eighteenth century. ↩︎

-

44

The first state is clearly signed “Brandoin invt” and was published on 29 July 1771 by W. Darling and J. Roberts; a copy is now in the Pierpont Morgan Library, New York. Darly reissued the print on 1 May 1772. He kept the title but changed the signature to “B- invt”, although this version is now ascribed to Bunbury (see BM4919). The reference to the 1776 edition is taken from the catalogue entry to BM4919. For the View on the Pont Neuf, see BM4918 (251 x 357 mm). A larger design in reverse was being sold by John Harris (BM4763; 46.8 x 61.8 cm). ↩︎

-

45

BM4932, published 20 October 1771. ↩︎

-

46

BM4478, published 10 May 1770. ↩︎

-

47

Donald, Age of Caricature, 138, notes how Englishness signified as women in riding dress in graphic satire of the 1780s: it was about being dressed down rather than up, and could “signify shameless sexual forwardness and female dominance”. For satirical prints of English and French tourists, see John Collet’s Frenchman in London (BM4477) and Englishman in Paris (BM4478); Samuel Grimm’s The French Lady in London (BM4784) and The English Lady in Paris (BM4785) and Brandoin’s English Lady in Paris (BM4931) all published between May 1770 and November 1771. For a satirical print with nationally specific dogs, see BM5612, published in 1779. ↩︎

-

48

The same method—selection and adaptation of thematically related sources—is used by Rowlandson to burlesque the monument. His version is a copy of a small marble depicting Louis XIV dressed à l’antique. It belonged to the Royal Collection and was displayed in the Orangerie at Versailles. It preceded the public monument, for which Desjardins added a coronation robe and baton, neither of which Rowlandson depicts. For the relationship between the two works, see Souchal, French Sculptors, cat. no. 45, and Ziegler, Louis XIV, 99 and Figure 59. ↩︎

-

49

Payne and Payne, Regarding Thomas Rowlandson, 24–34, although suggesting that was was training as a sculptor. His name appears once on the register for foreign students now held at the Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris, and is one of only six British (or Irish) students enrolled in the 1770s. See Manuscript no. 45, Microfilm no. 30: “Liste des élèves britanniques et irlandais à l’Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture de 1758 à 1793”, Folio 138: “Thomas Rolanson, d’Angleterre, âgé de 17 ans, Protégé par M. Pigalle, demeure rue d’Autefeuille à l’Hôtel d’Angleterre [?] le 11 mars 1775”. His admission was supported by a Professor of Sculpture, Jean-Baptiste Pigalle (1714–1785) although being “sponsored by” (“protégé par”) a professor was distinct from being their pupil (“élève de”): it was simply a requirement that was necessary to gain access to the academic curriculum. See Isabelle Frère, “L’Enseignement de la sculpture à Paris entre 1740–1770” (Thesis, Ecole du Louvre, 1995). ↩︎

-

50

For the preponderance of the amateur, see notes 40 and 43 above. For a discussion of caricature's complex relationship with the Academy, see Petherbridge, Primacy of Drawing, 347–77, and more specifically in mid-eighteenth-century France, Laurent Baridon and Martial Guédron, L’Art et L’histoire de la Caricature (2006; Paris: Citadelles & Mazenod, 2015), 67–121. For examples of caricatures produced in these contexts, see McPhee and Orenstein, eds., Infinite Jest, cat. nos. 7–9, 19–23, 24, 95, and 112–13. ↩︎

-

51

For education in London and the Academy’s cosmopolitan outlook, see Hoock, King’s Artists, 52–62; 109–14. For the Paris Académie, see Jacqueline Lichtenstein and Christian Michel, eds, Les Conférences de l’Académie royale de Peinture et de Sculpture, Tome VI, Vol. 3 1752-1792 (Paris, 2014), highlighting tradition and the use of repetitive procedures like the rereading of older lectures. The reference to the “carte fidèle” meaning a student’s “faithful card” of internalized methodologies, comes from Frère, L’Enseignement, 18, quoting an Académie lecture, “Droits et devoirs de l’Artiste”, read out to the students on 4 May 1748. ↩︎

-

52

For the publishing history of Du Fresnoy in France in the late eighteenth century, see Lichtenstein and Michel, eds, Les Conférences, Annexe II, 1166–67; for the British reception of French art theory and theories of “invention” as interpretation, see Carol Gibson-Wood, Jonathan Richardson: Art Theorist of the English Enlightenment (New Haven and London: Yale Univ. Press, 2000), 143–79. ↩︎

-

53

The Art of Painting of C. A. Fresnoy . . . with Annotations by Sr Joshua Reynolds, President of the Royal Academy (London, 1783), 7 and Note IV, 69. ↩︎

-

54

Du Fresnoy, Art of Painting, Note IV, 69. Of course, the same ideas informed the Discourses that Reynolds delivered annually to the students. For an early exposition of his “Theory of Art”, see Seven Discourses Delivered in the Academy by the President (London, 1778), the second in particular, delivered December 1769, 29–63. ↩︎

-

55

See Donald, Age of Caricature, 60–74, with an emphasis on the contribution of the amateur caricaturists like James Boyne (c. 1750–1810) in the early 1780s. ↩︎

-

56

See Hallett, “James Gillray”, 30–31 who extends the discussion to Rowlandson but for prints like A Covent Garden Nightmare, a parody of an Academy painting that he published in 1784 (BM6543), rather than the exhibited caricatures. ↩︎

-

57

Around 1783/84, the average size of a caricature print was 25 x 35 cm, whereas the drawing is 34.9 x 53.4 cm and was even larger when published as a print: 44 x 61.5 cm. On jokes as a “play upon form” that depend on the recognition that an accepted practice can change, see Mary Douglas, Implicit Meanings: Essays in Anthropology (London: Routledge, 1975), 96, quoted in Simon Critchley, On Humour (Abingdon and New York: Routledge, 2002), 10. These ideas are discussed as parody and intertextuality in caricature in Donald, Age of Caricature, 67–73. For incongruity as a stimulus to laughter, see James Beattie, “On Laughter, and Ludicrous Composition”, in Essays (Edinburgh, 1776). ↩︎

-

58

Donald, Age of Caricature, 28. ↩︎

-

59

See George Bickham, Deliciae Britannicae, or the Curiosities of Kensington, Hampton Court and Windsor Castle (London, 1755), 103–04, for a description. The “Triumphs” referred to nine separate paintings hung around the walls of a single room: “the whole is a Triumph of Julius Caesar, consisting of a long Procession of Soldiers, Priests, Officers of State &c, at the End of which, that Emperor appears in his triumphant Chariot, with Victory over his Head, crowning him with Laurel. It is painted in Water-colours upon Canvas.” For a more recent account, see Christopher Lloyd, Andrea Mantegna: The Triumphs of Caesar: A Sequence of Nine Paintings in the Royal Collection (London: HMSO, 1991). ↩︎

-

60

For the jubilant reception, see The New Annual Register or General Repository of History, Politics and Literature for the year 1783 (London, 1784), chapter 2, 12. ↩︎

-

61

See David Solkin, “‘The Great Mart of Genius’: The Royal Academy Exhibitions at Somerset House, 1780–1836”, in Art on the Line, 3, for “individuation” in this context; see also David Solkin, ed., Turner and the Masters (London: Tate Publishing, 2009), 99–141, on “Education and Emulation”. ↩︎

-

62

Recent studies concentrating on caricature as a printed visual culture include: Vic Gatrell, The City of Laughter: Sex and Satire in Eighteenth-Century London (London: Atlantic Books, 2006); Amelia Rauser, Caricature Unmasked: Irony, Authenticity, and Individualism in Eighteenth-Century English Prints (Cranbury, NJ: Univ. of Delaware Press, 2008); Todd Porterfield, ed., The Efflorescence of Caricature, 1759–1838 (Farnham: Ashgate, 2011); Ian Haywood, Romanticism and Caricature (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2013); Joseph Monteyne, From Still Life to the Screen: Print Culture, Display and the Materiality of the Image in Eighteenth-Century London (New Haven and London: Yale Univ. Press, 2013); and Kremers and Reich, eds., Loyal Subversion? ↩︎

Bibliography

Primary Materials

Manuscript no. 45, Microfilm no. 30: “Liste des élèves britanniques et irlandais à l’Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture de 1758 à 1793”: Folio 138.

A Catalogue of the Pictures, Sculptures, Models, Drawings and Prints &c, Exhibited by the Society of Artists of Great-Britain. London, 1761.

A Catalogue of the Pictures, Sculptures, Models, Designs in Architecture, Prints, &c Exhibited by the Society of Artists of Great Britain. London, 1783.

The Art of Painting of C A Fresnoy . . . with Annotations by Sr Joshua Reynolds, President of the Royal Academy. London, 1783 (Eighteenth Century Collections Online, ECCO).

Anon. The New Annual Register or General Repository of History*, Politics and Literature for the year 1783*. London, 1784. Chapter II, 12 (ECCO).

Beattie, James. “On Laughter, and Ludicrous Composition.” In Essays. Edinburgh, 1776 (ECCO).

Bickham, George. Deliciae Britannicae, or the Curiosities of Kensington, Hampton Court and Windsor Castle. London, 1755 (ECCO).

Darly, Mary. A Book of Caricaturas on 60 Copper Plates in that Droll and Pleasing Manner. London, 1762.

Grose, Francis. Rules for Drawing Caricaturas with an Essay on Comic Painting. London, 1788.

Reynolds, Sir Joshua. Seven Discourses Delivered in the Academy by the President. London, 1778.

Trusler, John. Hogarth Moraliz’d. London, 1768.

Walpole, Sir Horace. Anecdotes of Painting in England, Vol. 4. 4th edn. London, 1796.

Secondary Materials

Baker, Malcolm. The Marble Index: Roubiliac and Sculptural Portraiture in Eighteenth-Century Britain. New Haven and London: Yale Univ. Press, 2014.

Baridon, Laurent, and Martial Guédron. L’Art et L’histoire de la Caricature. Paris: Citadelles & Mazenod, [2006], 2015.

Barrell, John. “The Private Comedy of Thomas Rowlandson.” In The Birth of Pandora and the Division of Knowledge. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1992, 1–25.

Blackwell, Caitlin. “John Collet (ca 1725–1780): A Commercial Comic Artist.” PhD thesis, University of York, 2013.

Brewer, David. “Making Hogarth Heritage.” Representations 72 (Autumn 2000): 21–63.

Clayton, Timothy. The English Print, 1688–1802. New Haven and London: Yale Univ. Press, 1997.

– – –. “The London Printsellers and the Export of English Graphic Prints.” In Loyal Subversion? Caricatures from the Personal Union between England and Hanover (1714–1837). Ed. Anorthe Kremers and Elisabeth Reich. Gottingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2014, 140–62.

Critchley, Simon. On Humour. Abingdon and New York: Routledge, 2002.

Dias, Rosie. Exhibiting Englishness: John Boydell’s Shakespeare Gallery and the Formation of a National Aesthetic. New Haven and London: Yale Univ. Press, 2013.

Donald, Diana. The Age of Caricature: Satirical Prints in the Reign of George III. Newhaven and London: Yale Univ. Press, 1996.

Douglas, Mary. Implicit Meanings: Essays in Anthropology. London: Routledge, 1975.

Frère, Isabelle. “L’Enseignement de la sculpture à Paris entre 1740–1770.” Thesis, Ecole du Louvre, 1995.

Gatrell, Vic. The City of Laughter: Sex and Satire in Eighteenth-Century London. London: Atlantic Books, 2006.

Gibson-Wood, Carol. Jonathan Richardson: Art Theorist of the English Enlightenment. New Haven and London: Yale Univ. Press, 2000.

Godfrey, Richard. English Caricature: 1620 to the Present. London: Victoria & Albert Museum, 1984.

Grandjouan, Kate. “Close Encounters: French Identities in English Graphic Satire, c. 1730–1790.” PhD thesis, Courtauld Institute of Art, 2010.

Graves, Algernon. The Royal Academy of Arts: A Complete Dictionary of Contributors and their Work from its Foundation in 1769 to 1904. Bath: Kingsmead Reprints, 1970.

Hallett, Mark. “James Gillray and the Language of Graphic Satire.” In James Gillray: The Art of Caricature. Ed. Richard Godfrey. London: Tate Publishing, 2001, 23–39.

– – –. Reynolds: Portraiture in Action. New Haven and London: Yale Univ. Press, 2014.

– – –. The Spectacle of Difference: Graphic Satire in the Age of Hogarth. New Haven and London: Yale Univ. Press, 1999.

Hargraves, Matthew. Candidates for Fame: The Society of Artists of Great Britain, 1760–1791. New Haven and London, Yale Univ. Press, 2006.

Hauptman, William. “Beckford, Brandoin and the ‘Rajah’: Aspects of an Eighteenth-Century Collection.” Apollo 143, no. 411 (May 1996): 30–39.

– – –. Samuel Hieronymus Grimm (1733–1794): A Very English Swiss. Bern: Kunstmuseum, 2014.

Hayes, John. The Art of Thomas Rowlandson. Alexandria, VA: Art Services International, 1990.

– – –. Thomas Rowlandson: Drawings and Watercolours. London: Phaidon, 1972.

Haywood, Ian. Romanticism and Caricature. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2013.

Heard, Kate. High Spirits: The Comic Art of Thomas Rowlandson. London: Royal Collection Trust, 2015.

Hoock, Holger. The King’s Artists: The Royal Academy of Arts and the Politics of British Culture, 1760–1840. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 2003.

Kremers, Anorthe, and Elisabeth Reich, eds. Loyal Subversion? Caricatures from the Personal Union between England and Hanover (1714–1837). Gottingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2014.

Lefeuvre, Olivier. Philippe-Jacques de Loutherbourg. Paris: Athena, 2012.

Lichtenstein, Jacqueline, and Christian Michel, eds. Les Conférences de l’Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture, Tome VI, Vol. 3: 1752–1792. Paris: Ecole des Beaux Arts, 2014.

Lloyd, Christopher. Andrea Mantegna: The Triumphs of Caesar: A Sequence of Nine Paintings in the Royal Collection. London: HMSO, 1991.

McCalman, Iain. “Conquering Academy and Marketplace: Philippe de Loutherbourg’s Channel Crossing.” In Living with the Royal Academy: Artistic Ideals and Experiences in England, 1768–1848. Ed. Sarah Monks, John Barrell, and Mark Hallett. Farnham: Ashgate, 2013, 75–88.

McPhee, Constance C., and Nadine M. Orenstein, eds. Infinite Jest: Caricature and Satire from Leonardo to Levine. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2012.

Monks, Sarah, John Barrell, and Mark Hallett, eds. Living with the Royal Academy: Artistic Ideals and Experiences in England, 1768–1848. Farnham: Ashgate, 2013.

Monteyne, Joseph. From Still Life to the Screen: Print Culture, Display and the Materiality of the Image in Eighteenth-Century London. New Haven and London: Yale Univ. Press, 2013.

Oppé, André Paul. Thomas Rowlandson: His Drawings and Water-colours. London: The Studio, 1923.

Paulson, Ronald. Don Quixote in England: The Aesthetics of Laughter. Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, 1998.

Payne, Matthew, and James Payne. Regarding Thomas Rowlandson, 1757–1827: His Life, Art and Acquaintance. London: Hogarth Arts, 2010.

Petherbridge, Deanna. The Primacy of Drawing: Histories and Theories of Practice. New Haven and London: Yale Univ. Press, 2010.

Pointon, Marcia. “Portrait! Portrait! Portrait!” In Art on the Line: The Royal Academy Exhibitions at Somerset House, 1780–1836. Ed. David Solkin. New Haven and London: Yale Univ. Press, 2001, 93–111.

Porterfield, Todd, ed. The Efflorescence of Caricature, 1759–1838. Farnham: Ashgate, 2011.

Puetz, Anne. “Foreign Exhibitors and the British School at the Royal Academy, 1768–1823.” In Art on the Line: The Royal Academy Exhibitions at Somerset House, 1780–1836. Ed. David Solkin. New Haven and London: Yale Univ. Press, 229–43.

Rauser, Amelia. Caricature Unmasked: Irony, Authenticity, and Individualism in Eighteenth-Century English Prints. Cranbury, NJ: Univ. of Delaware Press, 2008.

Riely, John. “Horace Walpole and ‘the Second Hogarth’”, Eighteenth-Century Studies 9, no. 1 (Autumn 1975): 28–44.

– – –. “Rowlandson’s Early Drawings.” Apollo 117, no. 251 (Jan. 1983): 30–39.

Roman, Cynthia Ellen, ed. Hogarth’s Legacy. New Haven and London: Yale Univ. Press, 2016.

Sloan, Kim. A Noble Art: Amateur Artists and Drawing Masters, c. 1600–1800. London: British Museum Press, 2000.

Smith, Greg. The Emergence of the Professional Watercolourist: Contentions and Alliances in the Artistic Domain, 1760–1824. Farnham: Ashgate, 2002.

– – –. “Watercolourists and Watercolours at the Royal Academy, 1780–1836.” In Art on the Line: The Royal Academy Exhibitions at Somerset House, 1780–1836. Ed. David Solkin. New Haven and London: Yale Univ. Press, 2001, 189–200.

Solkin, David. Art in Britain, 1660–1815. New Haven and London: Yale Univ. Press, 2015.

– – –. “‘The Great Mart of Genius’: The Royal Academy Exhibitions at Somerset House, 1780–1836.” In Art on the Line: The Royal Academy Exhibitions at Somerset House, 1780–1836. Ed. Solkin. New Haven and London: Yale Univ. Press, 2001, 1–8.

Solkin, David, ed. Art on the Line: The Royal Academy Exhibitions at Somerset House, 1780–1836. New Haven and London: Yale Univ. Press, 2001.

– – –. Turner and the Masters. London: Tate Publishing, 2009.

Souchal, François. French Sculptors of the 17th and 18th Centuries: The Reign of Louis XIV: Vol. 1. London: Cassirer, 1977.

Wark, Robert. Rowlandson’s Drawings for a Tour in a Post Chaise. San Marino, CA: Huntington Museum and Art Gallery, 1963.

Wilcox, Scott, ed. The Line of Beauty: British Drawings and Watercolors of the Eighteenth Century. New Haven: Yale Center for British Art, 2000)

Ziegler, Hendrik. Louis XIV et ses Ennemies: Image, Propagande et Contestation. Translated into French by Aude Virey-Wallon. Paris: Centre allemand d’histoire de l’art, 2013.

Imprint

| Author | |

|---|---|

| Date | 28 November 2016 |

| Category | Article |

| Review status | Peer Reviewed (Double Blind) |

| License | Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) |

| Downloads | PDF format |

| Article DOI | https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-04/kgrandjouan |

| Cite as | Grandjouan, Kate. “Super-Size Caricature: Thomas Rowlandson’s Place Des Victoires at the Society of Artists in 1783.” In British Art Studies. London and New Haven: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art and Yale University Press, 2016. https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-04/kgrandjouan. |