Liturgy and Music in Hereford Cathedral in the Time of Queen Victoria and Beyond

Liturgy and Music in Hereford Cathedral in the Time of Queen Victoria and Beyond

By Tessa Murdoch

Abstract

The Victorian Gothic Revival and its focus on liturgical neo-medievalism inspired the 1860s restoration of the medieval Hereford Cathedral. In this restoration, the new screen played a central part. Designed by George Gilbert Scott and manufactured by the firm of Francis Skidmore in Coventry, the screen was commissioned in order to re-unite the choir with the nave. The symbolism and colours decorating the screen harmonized with the medieval and later features of the cathedral, including the high altar reredos, organ pipes, and floor tiles. Hereford Cathedral Library preserves historical accounts of the interior and original music manuscripts by Edward Elgar and Frederick Ouseley that illustrate, with the musical inserts provided, the rich tradition of choral music and liturgy which continues to this day with key liturgies and the annual Three Choirs Festival linking Gloucester, Hereford, and Worcester. Memorials and stained-glass windows dedicated to successive precentors embellish the musical vocabulary of the interior. In focusing on the musical culture connected with Hereford Cathedral, this article seeks to enrich the interpretation of the restored Hereford Screen in its secular setting at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Introduction

The Church of England’s ceremonial and liturgical revival in the mid-nineteenth century, prompted by the Ecclesiological Society which was founded in 1839, reinstated traditional Catholic worship and musical traditions. The Ecclesiological Society was a group of laity and clergy who had been inspired by the Oxford Movement in Anglican theology. As High Anglicans, sometimes also called “ritualists” or “Puseyites” because of the principles and church figures they followed, the Ecclesiologists were determined to return the Church of England to its pre-Reformation roots through careful attention to the revival of medieval art, architecture, music, symbolism, and particularly liturgy. By 1860 the fabric of Hereford Cathedral urgently needed restoring and adapting in order to accommodate such liturgical renewal, but the cathedral Chapter were opposed to anything that emulated the Roman Catholic practice. A programme of restoration was begun that included the replacement of an existing stone screen with a new one. In 1862, responding to an appeal from the Dean and Chapter of Hereford Cathedral for the restoration of the cathedral, the architect George Gilbert Scott provided an estimate of £1,500 for a new choir screen. Scott explained that

1instead of extending the Choir westward, through the Tower as formerly, and severing it from the remainder of the Church by a solid Screen of stone thus limited in length to its more natural position, the eastern arm of the Cathedral; an open unobstructed screen (has been) substituted for the close structure of stone, an arrangement already carried out with great practical advantage at Ely and Lichfield. When the screen is placed in its proper position beneath these glorious Norman Arches which support the Tower, it will be satisfactory to see that productions of modern art may be made to blend harmoniously with the types of beauty furnished by the taste and science of former ages.1

The Dean and Chapter responded that “The refitting of the Choir and the introduction of a magnificent open Screen of Metal-work, in lieu of the ancient Stone Screen” would have the effect of “opening out the Choir to the Nave and rendering nearly the entire church available for public worship, an alteration of the greatest practical importance”. But they also noted that “the casing and decoration of the organ” was “as yet unprovided for”.2 The subsequent list of subscribers for the restoration was headed by Queen Victoria at £100.3

2The 1863 Guide to the “Restored Portion” of the Cathedral Church of Hereford contains details of “the Metallic Rood Screen, Corona, [and] Stained Windows” and notes that the “Use of Metallic art in ancient Churches and Cathedrals, and its fitness in a restoration” is evident from descriptions in various ancient treatises including William of Malmesbury’s records of Winchester and Coventry and Laud’s on Glastonbury and Waltham Abbey, which describe works of “gold, silver, precious stones, copper, brass of great magnitude, which were rendered into plaques of gold and applied to surfaces, capitals of columns, altars, and various other uses unapplied in the present day . . . it is a correct revival of ancient art. The metallic idiom is further developed by the colours of the illumination being derived from the oxides of the metals used in the construction of the screen” with the exception of the green.4 Green was chosen, as for the floor tiles, as the liturgical colour dominant throughout the church calendar between Epiphany and Lent and between Trinity Sunday and Advent (excluding those two Sundays when white is used); as the colour of plants, green is the symbol of new life.5

4An article published in The Times in May 1862, when the screen was exhibited in London at the International Exhibition at South Kensington, noted that “The colouring and the gilding have been applied only with a view to the effect of the whole piece when shown in the subdued light of a Cathedral interior.” Furthermore, the article noted that “the passion and everlasting flowers especially have been much used, and with admirable effect.” The brass work was “intermixed with broad masses of vitreous mosaic”, which were composed of “over 50,000 pieces of ironstone, marble etc involving 70 workmen over a period of 5 weeks from the end of March to May”.6 The passion flower (Passiflora) had been adopted as a symbol of Christ’s Passion by Spanish Christian missionaries from the fifteenth century. Its physical structure was interpreted as representing Christ’s last days and crucifixion. The pointed tips of the leaves recalled the Holy Lance; the tendrils, the whips used in the flagellation of Christ; the ten petals and sepals, the ten faithful apostles; the radial filaments, the crown of thorns; the chalice-shaped ovary with its receptacle, the Holy Grail; the three stigmata, the three nails; and the five anthers below them, the five wounds (four inflicted by the nails and one by the lance). The blue and white colours of the flower came to represent Heaven and Purity.7

6The description in Murray’s Handbook, produced for visitors to Hereford Cathedral and first published in 1864, endorses the newly installed Skidmore screen. “It may safely be said that this screen is the finest and most complete work of its class which has been produced in recent times.” It

8affords a complete vindication of the advantage and beauty of metal-work for the purpose of which it is here applied. While the screen forms a sufficient division between the nave and the choir, its extreme lightness permits the use of both tower and transept for congregational purposes. The heads of the arches and the spandrels between them are enriched with elaborate tracery, chiefly formed by flowers and leafage; and the design of the cornice and cresting is of similar character. Single figures of angels, holding up instruments of music, are placed on brackets, at the termination of the screen, North and South.8

They correspond to the angels with instruments of the Passion which surmount the reredos of the high altar (fig. 1). “Coloured mosaics have also been employed. The variety of metals are the source of colour; but the hammered ironwork forming the whole of the foliage has been painted throughout. No colours have been used, however, but those of the oxides of iron and copper—the metals employed in the work.”9

9

Ten years earlier, George Gilbert Scott had in fact voiced doubts about the removal of the stone pulpitum at Hereford Cathedral, which he regarded as a diocesan loss and an error from an antiquarian perspective. He explained that the metal screen came about because Skidmore “was anxious to have some great work in the exhibition of 1862 and offered to make the screen at a very low price. I designed it on a somewhat massive scale, thinking that it would thus harmonize better with the heavy architecture of the choir. Skidmore followed my design but somewhat aberrantly. It is a fine work, but too loud and self-asserting for an English church.”10

10Murray’s Handbook notes that the screen’s “projecting branches for lights, are unusual and picturesque”.11 The standard gas lamps were lit with more than fifty jets of gas, and with the great corona lucis designed by Scott and executed by Skidmore which was suspended from the centre of the tower, the effect was

1112of more than Oriental magnificence . . . the circlet of the crown sheds a soft and diffused light down upon the screen, and the standards surrounding the circle, which consist of groups of light enveloping a mass of crystals, produce a singular and gem-like appearance, suggestive of jewels on a crown, whilst serving the practical purpose of illuminating the upper part of the tower. Beyond all question, the time when the entire building appears to the greatest advantage is Sunday evening, when the Corona and Standards are lighted.12

Beyond the chancel screen, the focal point was provided by the earlier altar screen with its reredos of Caen marble and oolite Bath stone designed by Nockalls Johnson Cottingham and carved by W. Boulton of Lambeth. It was paid for by public subscription and created in memory of Joseph Bailey, Member of Parliament for Hereford, who died in 1852.14 Above the altar the stained glass in the east window in the Lady Chapel was commissioned in memory of Dean Merewether, who died in 1850.15 After the installation of the Skidmore screen, the new 1876 altar frontal, marking the 1,200th anniversary of the foundation of the cathedral, was embroidered with figures representing twelve saints particularly linked to Hereford Cathedral.16 The elaborate tiled floor with its liturgical colours dominated by greens and reds harmonizes with the metallic colours used to decorate the screen. The tile pavement covers the whole of the interior eastward of the nave and includes a roundel depicting St Ethelbert (fig. 2), who is also represented in the altar frontal. The pavement was provided at a cost of £600 by William Godwin of Lugwardine, whom Gilbert Scott complimented by remarking that their tiles were closer to the medieval prototypes than those produced by Minton and Company (fig. 3).17

14

The Choral Revival at Hereford

At Hereford Cathedral in the 1840s a choral revival drew on earlier musical traditions using manuscripts in the cathedral library. But in 1849 the condition of the choir left much to be desired. There were only eight members, most of whom lived outside Hereford.18

18

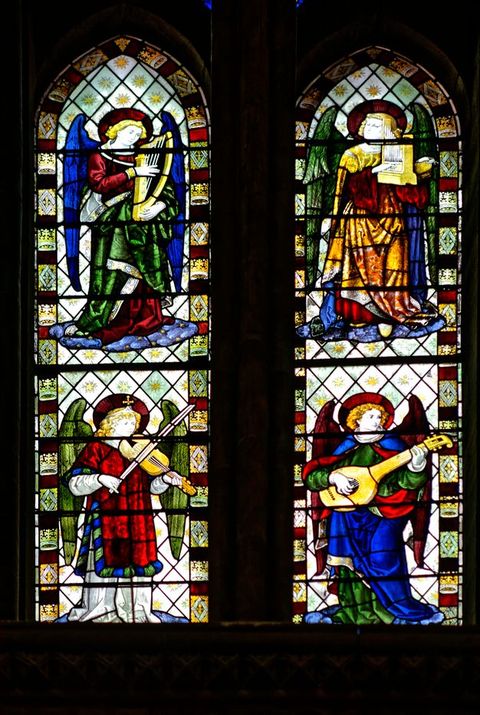

Sir Frederick Ouseley (1825–1889), who was ordained priest in 1855 and was professionally trained as a musicologist, resolved “to raise the music in the Sanctuary”. Ouseley was determined to build on the musical foundations laid by the cathedral prebendary John Jebb (1805–1886), former rector of the parish of Peterstow, Herefordshire. Jebb was an important liturgist who had been appointed in 1858 and later became a canon. The window dedicated to Jebb’s memory in the choir clerestory shows four angels playing musical instruments, a harp, a portative organ, a violin, and a citole (fig. 4); it was designed by John Burlison and Thomas Grylls, who had trained in the studio of Clayton and Bell.19 Jebb was inspired by the singing of German choirs and wrote from Dresden: “I think every Precentor and Choir Master ought to come and hear the boys here, both in the Roman Catholic and in the Lutheran Church I never heard anything equal or approaching to the excellence of their voices I wish I could catch a Saxon lad and import him! But I fear this is impossible. I assure you I am all agog about the matter.”20

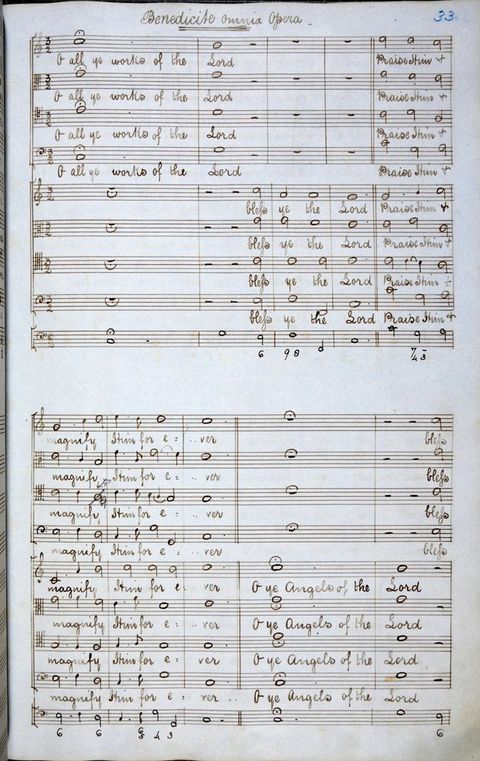

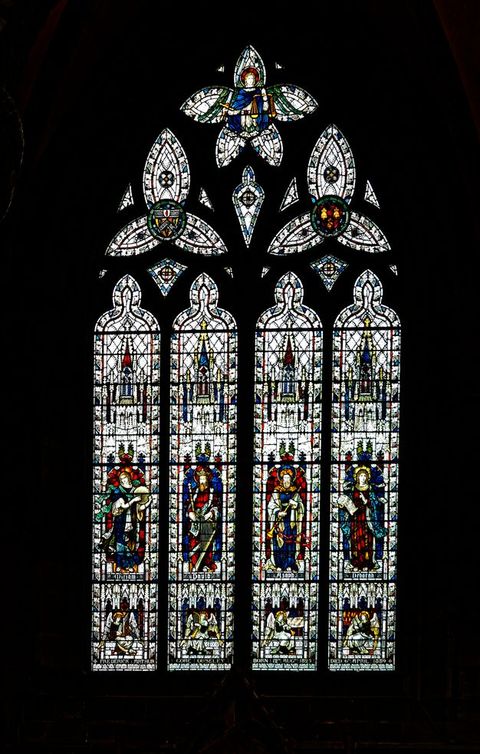

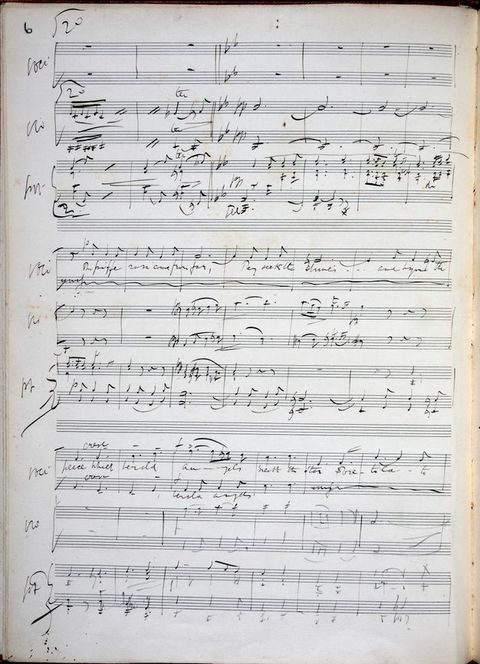

19Ouseley insisted on daily choral services and a model choir. In order to realize this ambition he founded the College of St Michael at Tenbury, Worcestershire, for training choristers. The college was inaugurated in 1856. That same year Ouseley formed a double choir. His Te Deum, Benedictus, Kyrie, Credo, Sanctus, Gloria in Excelsis, Magnificat, and Nunc Dimittis (fig. 5) were performed under his supervision at the reopening of the cathedral after its great restoration, on 30 June 1863. A window in Ouseley’s memory in the south nave aisle, made by Powell & Sons, Whitefriars, London (fig. 6), shows the four Old Testament musicians: Miriam with a timbrel, David with a harp, Asaph with a trumpet, and Deborah singing. At the foot are angels playing a portative organ, a harp, a shawm, and chime bells.21 Ouseley’s legacy extended far beyond the major role he had at the cathedral. Indeed, historian Owen Chadwick has suggested that Ouseley did more than any other individual to raise the standards of Victorian church music. Ouseley admitted Percy Hull to the cathedral choir, who later served at Hereford Cathedral as organist from 1918 to 1949, and was responsible for the first Three Choirs Festival after the Second World War. The festival is both unique and culturally significant as it is the oldest non-competitive classical music festival in the world, established for the love of collaborative performance between cathedral choirs and the enjoyment of sacred music in itself to the greater glory of God, rather than for the pleasures of competing.

21

Though the cathedral archives do not contain a full run of all Victorian service sheets, those which do survive from the 1860s and 1880s demonstrate the range of sacred music performed that drew on English musical traditions, including anthems by Attwood, Boyce, Byrd, Croft, Gibbons, Goss, Handel, Purcell, Stainer, Tallis, and Wesley. This shows that the cathedral was fashionable in choosing works from diverse musical styles and periods, and had a part to play in the revival of early church music in the late Victorian period.22 The Gothic Revival ideals of the Ecclesiologists were alive at Hereford not only in Scott and Skidmore’s screen, but in the choral repertoire as well. In 1832 Samuel Sebastian Wesley, organist at Hereford from 1832 to 1835, wrote The Wilderness for the rebuilt Renatus Harris organ;23 and for Easter Day in 1834 Wesley composed Blessed be the God and Father24 at the Dean’s request (fig. 7).25 The Harris organ was then taken down from the crossing screen in 1841. Following the temporary re-siting of the instrument at floor level at the eastern end of the north aisle of the nave after the pulpitum was removed, a new instrument (incorporating some elements of the old organ) was built by Gray and Davison. Used for the first time in June 1864, the organ was placed in the westernmost bay of the south choir aisle. Scott designed a wrought-iron framework to display the visible pipes rather than create a more substantial case, but had those pipes elaborately painted and gilded, at a cost of £154. The organ immediately proved unsatisfactory for a number of reasons, and less than ten years later the leading organ builder, Henry Willis, recommended a complete rebuilding (including lifting the whole case 1.5 metres higher up), for which work £1,300 was raised by public subscription (fig. 8). The organ therefore became a key element of the chancel renovation together with the Hereford Screen. In order to understand the aesthetic and symbolic aspects of the screen, it needs to be considered together with the 1860s Gray and Davison organ, for which Scott also designed decoration deliberately in keeping with the colours and patterns of the Hereford Screen.

22

Performing the Sacred

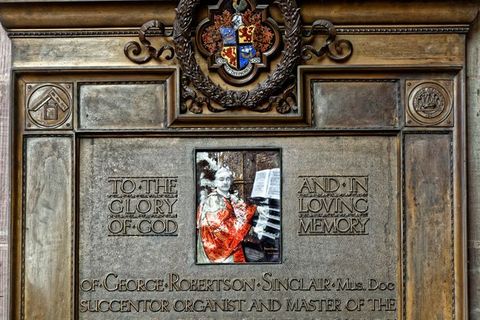

Musical treasures in the cathedral library include the original manuscript of Edward and Alice Elgar’s A Christmas Greeting26 of 1907, dedicated to the Hereford Cathedral choristers (figs. 9 and 10).27 A song for boys’ voices, two violins, and a piano, it was specially composed for Dr G. R. Sinclair, who was the cathedral organist from 1889–1917. Sinclair was a chorister at Ouseley’s College of St Michael in Tenbury for six years—so he was firmly part of the local tradition.28 Elgar lived in Hereford from 1904 to 1911, and his friendship with Sinclair perhaps influenced his move to the cathedral city. Parts of Elgar’s oratorio The Apostles were composed in Sinclair’s house (in Church Street, almost under the shadow of the cathedral tower), and he dedicated Pomp and Circumstance March No. 4 to Sinclair (who celebrated by promptly arranging a transcription for organ).

26

Sinclair died unexpectedly at the age of fifty-three in 1917. An enamelled bronze memorial by Fanny Bunn, with a relief showing Sinclair at the organ console, was placed at the entrance to the south choir aisle (fig. 11).29 He had already been immortalized as the bulldog in Variation XI of Elgar’s Enigma Variations.30 The words for A Christmas Greeting were written by Lady Elgar in Rome in December 1907 and sent to their friends instead of Christmas cards; these lines mark the re-emergence of Alice as a poet.31

29Bowered on sloping hillsides rise

In sunny glow, the purpling vine;

Beneath the greyer English skies,

In fair array, the red-gold apples shine.

. . .

On and on old Tiber speeds,

Dark with the weight of ancient crime;

Far north, thr’ green and quiet meads,

Flows on the Wye in mist and silv’ring rime

. . .

The pifferari wander far,

They seek the shrines, and hymn the peace

Which herald angels, 'neath the star;

Foretold to shepherds, bidding strife to cease.

. . .

Our England sleeps in shroud of snow,

Bells, sadly sweet, knell life’s swift flight,

And tears, unbid, are wont to flow,

As “Noel! Noel!” sounds across the night.

To those in snow,

To those in sun,

Love is but one!

Hearts beat and glow,

By oak and palm.

Friends, in storm or calm.

The setting is for high voices, with optional tenor and bass parts, and is in G minor and G major like the Enigma theme. The reference to pipers wandering far is a quotation from the “Pastoral Symphony” in Handel's Messiah.32 It had been a difficult five months for the composer who was suffering from depression.33 A Christmas Greeting was first performed at the Choristers’ Concert in Hereford Town Hall on 1 January 1908. The original manuscript was given to the cathedral by the composer’s daughter, Mrs Carice Irene Blake, before 1945, and it was performed again at the Three Choirs Festival on 26 August 1982.

32

On 3 September 1933, Elgar opened the Three Choirs Festival by conducting the London Symphony Orchestra playing the Imperial March, originally written for the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria, and the Civic Fanfare composed for the Hereford Festival thirty years later. The performance was illuminated by lights attached to the top of the Skidmore Screen (fig. 12). The photograph recording this event shows Sir Edward conducting quietly from his seat, his snow-white hair contrasting with the black velvet of full court dress, with the scarlet robes of his Oxford doctorate put off momentarily from his back.34 He died less than six months later.

34

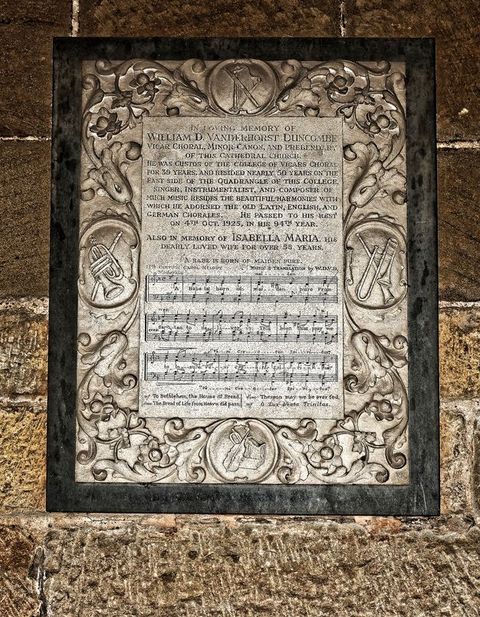

The archives retain orders of service that demonstrate the connections between the cathedral and the wider civic and county communities. The service on Hospital Sunday, 23 November 1913, lists the civic procession that graced the cathedral nave. Another records the service celebrating the 1,250th anniversary of the cathedral in 1926. The continuation of this musical tradition through the twentieth century and beyond is marked by the oak screen at the entrance to the organ loft in the north choir aisle which was erected in 1969 as a memorial to Sir Percy Hull, Sinclair’s pupil and successor—and dedicatee of Elgar’s Pomp and Circumstance March No. 5.35 There is a handsome monument to William Duncombe, Vicar Choral (fig. 13), whose long life and dedication to the cathedral as minor canon and prebendary is celebrated with trophies of musical instruments and the words and music of a fifteenth-century carol, “A Babe is born of Maiden Pure”:

35A Babe is born of maiden pure

From Satan to deliver us

This boon thus pray we to insure

Veni Creator Spiritus

To Bethlehem, The House of Bread

Thereon may we be overfed

The Bread of Life from Heaven did pass

O Lux beata Trinitas.

Hereford Cathedral continues musical celebrations when its choir joins those of Gloucester and Worcester for the Three Choirs Festival. The restored Skidmore screen, displayed above the main entrance hall in the Victoria and Albert Museum, also continues to function as a setting for musical performance. Evoking the liturgical and musical context of its earlier cathedral home, it still provides a setting for sacred music. A choir formed of staff from the South Kensington museums perform a cappella carols there every Christmas.

The Hereford Screen epitomizes the juxtaposition of tradition and innovation in mid-nineteenth-century architectural practice. Its exquisite colouring and jewel-like detail capture the symbolism and variety of tone associated with the liturgical calendar. Its lace-like tracery indicates the world beyond the screen. In Hereford Cathedral, the screen provided a prelude to the Eucharist at the heart of musical and liturgical celebration. At the Victoria and Albert Museum, its presence underlines this great museum’s foundation in the Victorian era, and its superb condition, following intensive conservation, anticipates the V&A’s restoration of the North and South Courts as a setting for nineteenth-century art and design of Europe, America, and beyond.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the following for advice and encouragement: Alicia Robinson, Ayla Lepine, at Hereford Cathedral, Canon Chancellor Christopher Pullin, Chapter Clerk and Chief Executive Glyn Morgan, the Librarian and Archivist Charlotte Berry and Rosemary Firman, also the Rt Revd John Oliver and Sir Roy Strong for facilitating introductions, and Christine Lloyd for her hospitality in Hereford.

About the author

-

Tessa Murdoch is Deputy Keeper, Sculpture, Metalwork, Ceramics and Glass, and the Senior Curator responsible for the Rosalinde and Arthur Gilbert Collection, at the Victoria and Albert Museum, which she joined in 1990. She is also Head of Metalwork and Expert Adviser on Metalwork and Silver to the Reviewing Committee on the Export of Works of Art. She was lead curator for the V&A’s 2005 Sacred Silver and Stained Glass Galleries and the 2009 Rosalinde and Arthur Gilbert Galleries. She was also lead curator for the 2012/2013 exchange of exhibitions between the V&A and the Moscow Kremlin Museums. In 2015 she co-edited and contributed to Burning Bright: Essays in Honour of David Bindman published by UCL press.

Footnotes

-

1

Hereford Cathedral, Appeal from the Dean and Chapter for Aid towards Completion of the Restoration of their Hereford Cathedral . . . with a letter from the architect George Gilbert Scott, 1862, 6. ↩︎

-

2

Appeal from the Dean and Chapter, 9. ↩︎

-

3

Appeal from the Dean and Chapter, 11. Other contributors included Lord Saye and Sele, Canon Residentiary at Hereford, who contributed £333. Local nobility included Lord Bateman and Earl Somers, both subscribing £200, as well as the Earl of Powys and the Hon Robert Clive, across the Welsh border; and local landowners included Mr Arkwright, Mr Bulmer, Messrs Bodenham, Edward Foley (who also subscribed £200), and the celebrated antiquary Sir Samuel Meyrick; clergy were headed by the Archbishop of Canterbury at £50 and included the Rev. John Croft. ↩︎

-

4

Guide to the “Restored Portion” of the Cathedral Church of Hereford, 2nd edn (Hereford, 1863), 11. ↩︎

-

5

J. W. Legg, Notes on the History of Liturgical Colours (London: John S. Leslie 1882); W. St John Hope and E. G. C. F. Atchley, English Liturgical Colours (London: SPCK, 1918); “colours, Liturgical”, in F. L. Cross and E. A. Livingstone, eds., The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996), 379. ↩︎

-

6

The Times, May 1862. ↩︎

-

7

Beverley Seaton, The Language of Flowers: A History (Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia, 1995). ↩︎

-

8

Hereford Cathedral Archive, RES H 274 2446 KIN. ↩︎

-

9

Hereford Cathedral Archive, RES H 274 2446 KIN. ↩︎

-

10

Gerard Aylmer and John Tiller, eds., Hereford Cathedral: A History (London: Hambledon Press, 2000), 276, quoting George Gilbert Scott, Personal and Professional Recollections (London: Sampson Low, 1879), 280 ff. ↩︎

-

11

Hereford Cathedral Archive, RES H 274 2446 KIN. ↩︎

-

12

Anon., Hereford Cathedral, City and Neighbourhood (Hereford, 1867), 26–27. ↩︎

-

13

Aylmer and Tiller, eds., Hereford Cathedral, 276, quoting Scott, Personal and Professional Recollections, 162. ↩︎

-

14

Aylmer and Tiller, Hereford Cathedral, 273. ↩︎

-

15

The window is designed in the thirteenth-century style to match the date of the architecture of the chapel. ↩︎

-

16

Flanking the figure of Christ in Glory on the left are represented St Margaret, St Anne, and St Catherine, with, below, St Mary Magdalene, St Agnes, the Virgin, and Baby Jesus. On Christ’s right are St John the Baptist, St Stephen, and St Thomas of Hereford, with, below, St Ethelbert, St Nicholas, and St George. For a detailed description, see Daphne Nicholson, Symbolism, Colour and Embroidery in Hereford Cathedral (Hereford: Friends of Hereford Cathedral, 1983), 18–19. The altar frontal was repaired in 1987–90 and redisplayed in 1993. ↩︎

-

17

Aylmer and Tiller, eds., Hereford Cathedral, 276. ↩︎

-

18

Aylmer and Tiller, eds., Hereford Cathedral, 421–22. ↩︎

-

19

Aylmer and Tiller, eds., Hereford Cathedral, 320; Hereford Cathedral Stained Glass (Norwich: Jarrold, 2007). ↩︎

-

20

H. G. Pitt, “Sir Frederick Ouseley and St. Michael’s College, Tenbury”, The Three Choirs Festival Programme (1982), 29–30 and 28. ↩︎

-

21

Aylmer and Tiller, eds., Hereford Cathedral, 320; Hereford Cathedral Stained Glass. ↩︎

-

22

Bernarr Rainbow, The Choral Revival in the Anglican Church, 1839–1872 (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2001). ↩︎

-

23

Renatus Harris, master organ builder (c. 1652–1724). ↩︎

-

24

Samuel Sebastian Wesley, Blessed be the God & Father, 1834, featured in My Beloved's Voice: Sacred Songs of Love, Choir of Jesus College, Cambridge, led by Mark Williams, Signum Records. Courtesy of Signum Records ↩︎

-

25

Hereford Cathedral Library holds Wesley’s autographs (and the earliest sources) of both Blessed be and The Wilderness (both in HCL C.9.12). ↩︎

-

26

Edward Elgar, A Christmas Greeting, 1978, by Roy Massey. Courtesy of the Archive of Recorded Church Music ↩︎

-

27

Hereford Cathedral Library, R.9 xxii L5 3890 (HCL R.9.22). ↩︎

-

28

Christopher Pullin notes that Elgar and Sinclair considered Ouseley to have been very hidebound and unimaginative as far as composition was concerned. For his DMus at Oxford in 1855 he submitted an oratorio, The Martyrdom of St Polycarp, which has sunk without trace. But when Elgar had a holiday in Turkey he visited the tomb of St Polycarp at Smyrna and picked a wildflower; he sent the dried flower “from the tomb of St Polycarp” to Sinclair. I think it was a little joke at Ouseley’s expense. The dried flower and Elgar’s covering letter to Sinclair are preserved in the cathedral archives. ↩︎

-

29

Aylmer and Tiller, Hereford Cathedral, illustrated at 359. ↩︎

-

30

Sinclair’s bulldog Dan attended every Choral Society rehearsal and one member immortalized him with a caricature, “The Metamorphosis of Dan”, which is illustrated in Timothy Day, The Hereford Choral Society: An Unfinished History (Hereford Choral Society, 2013), 35. ↩︎

-

31

Percy M. Young, Alice Elgar: Enigma of a Victorian Lady (London: Dobson, 1978), 162–63. ↩︎

-

32

From notes by Michael Kennedy © 1987 on Hyperion Records http://www.hyperion-records.co.uk/dw.asp?dc=W12218_GBAJY8727206. ↩︎

-

33

Young, Alice Elgar, 163. ↩︎

-

34

Jerrold Northrop Moore, Elgar: A Life in Photographs (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988), 100. ↩︎

-

35

Thanks to Christopher Pullin for this information. ↩︎

-

36

The cathedral library has W. D. V. Duncombe’s A Collection of Old English Carols as sung at Hereford Cathedral, mostly traditional melodies harmonized, First Series, and numbers 2, 3, 5, 7, and 10 from the Second Series, 1894 (ref. R.15.12). There are also MS part books of carols collected by him (R.11.24-40). ↩︎

Bibliography

Anon. Hereford Cathedral, City and Neighbourhood. Hereford, 1867.

Aylmer, Gerard, and John Tiller, eds. Hereford Cathedral: A History. London: Hambledon Press, 2000.

Cross, F. L., and E. A. Livingstone, eds. The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996.

Day, Timothy. The Hereford Choral Society: An Unfinished History. Hereford Choral Society, 2013.

Guide to the “Restored Portion” of the Cathedral Church of Hereford. 2nd edn. Hereford, 1863.

Hereford Cathedral. Appeal from the Dean and Chapter for Aid towards Completion of the Restoration of their Cathedral . . . with a letter from their architect George Gilbert Scott, 7 November 1862.

Hope, W. St John, and E. G. C. F. Atchley. English Liturgical Colours. London: SPCK, 1918.

Legg, J. W. Notes on the History of Liturgical Colours. London: John S. Leslie, 1882.

Moore, Jerrold Northrop. Elgar: A Life in Photographs. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988.

Rainbow, Bernarr. The Choral Revival in the Anglican Church, 1839–1872. Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2001.

Scott, George Gilbert. Personal and Professional Recollections. London: Sampson Low, 1879.

Seaton, Beverley. The Language of Flowers: A History. Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia, 1995.

Nicholson, Daphne. Symbolism, Colour and Embroidery in Hereford Cathedral. Hereford: Friends of Hereford Cathedral, 1983.

Young, Percy M. Alice Elgar: Enigma of a Victorian Lady. London: Dobson, 1978.

Imprint

| Author | |

|---|---|

| Date | 10 April 2017 |

| Category | One object |

| Review status | Peer Reviewed (Editorial Group) |

| License | Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) |

| Downloads | PDF format |

| Article DOI | https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-05/tmurdoch |

| Cite as | Murdoch, Tessa. “Liturgy and Music in Hereford Cathedral in the Time of Queen Victoria and Beyond.” In British Art Studies. London and New Haven: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art and Yale University Press, 2017. https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-05/tmurdoch. |