Theology and Threshold

Theology and Threshold: Victorian Approaches to Reviving Choir and Rood Screens

By Ayla Lepine

Abstract

In 1851, A. W. N. Pugin published an influential treatise on rood screens, intending in his irrepressible polemical style to create further Gothic Revival momentum for inserting these iconographically complex and liturgically vital elements into Roman Catholic and Anglican churches throughout Britain and its empire. In the decades that followed, debates regarding ritual, aesthetics, materials, and Eucharistic theology surrounded the design, presence, and indeed absence of these screens. This interdisciplinary article on the borderlands between architectural history and theology explores what was at stake in the religious symbolism of a small number of diverse screens designed by George Gilbert Scott, George Frederick Bodley, and Ninian Comper, considering them in light of the key writing produced by Pugin at the mid-point of the nineteenth century, as well as by priest–architect Ernest Geldart in the century’s end. This study, together with its three short films that explore the screens’ meanings and histories in situ, charts shifts in theology and style as each architect offered innovative views through delicate latticework of stone, paint, and wood towards the Christian sacred epicentre of the Incarnation and the sacrifice of the Eucharist.

A constellation of viewpoints on the virtues, challenges, and controversies surrounding the revival of choir and rood screens emerged in Victorian Britain. By focusing on the unique importance of screens within the Gothic Revival as a whole, this essay considers the perspectives of Victorian and early twentieth-century British architects and designers A. W. N. Pugin, George Frederick Bodley, Ernest Geldart, and John Ninian Comper, to illuminate how leading Gothic Revival designers informed and learned from George Gilbert Scott’s groundbreaking collaborations with Francis Skidmore. The distinctiveness of Scott and Skidmore’s work for their trio of cathedral screens at Lichfield, Salisbury, and Hereford—and the Hereford Screen in particular—marked a turning point in the use of materials as well as the theological implications of a set of iconographic strategies offered as an ensemble within a monumental choir screen. Victorian architectural histories of sacred spaces can easily be done a disservice by not sufficiently considering their theological contexts. This essay outlines what was at stake in the relationship between seeing, liturgical interaction, and belief across a varied half-century of rood and choir screens. It notes the modern distinctions between these two approaches to the partitioning of churches and cathedrals, each of which invoked new ideas as much as referencing medieval ones.

Designs for nineteenth-century rood and choir screens were diverse and daring, and in many cases invited new ways of experiencing the beauty and wonder of sacramental life, particularly the Eucharist. As a way of bringing the Passion—and the Crucifixion in particular—into the heart of Christian worship in modern Britain, the rood’s traditional inclusion of Christ’s crucified body, attended and worshipped by the Virgin Mary and St John the Evangelist, was more strikingly visceral and, indeed, more Roman Catholic-leaning than the choir screen, which often had a simple cross or an image of Christ in majesty, resurrected and ascended into heaven. Scott and Skidmore’s cathedral screens are all of this latter choir-screen type. They were erected amidst an ongoing religious debate regarding screens, liturgical activity, and representations of Christ’s death and resurrection in sacred spaces focused on sacramental life and faith.

Victorian perceptions of and controversies over the revival of rood and choir screens were complex, and today their nuances can be clarified with reference to the modern philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s ideas about seeing and existence. These assist in shaping an approach to embodied vision, whereby the liturgical aspects of the rood and choir screen act as an invitation into greater wholeness with Christ through the preciousness of the Eucharistic sacrifice, rather than merely being an ornate barrier between the proper place of the laity and that of the clergy and sacred ministers. Merleau-Ponty wrote of what he called “that little verb” to see: “Vision is not a certain mode of thought or presence to self; it is the means given me for being absent from myself, for being present at the fission of Being from the inside—the fission at whose termination, not before, I come back to myself.”1 In his view, seeing is necessarily relational, and necessarily a vehicle of connectivity with the divine through multi-sensory stimulation.

1Similar dynamics of looking are articulated both in contemporary accounts of Victorian screens and by their interpreters in later eras. Regarding the Victorian revival of screens, Pugin’s recent biographer, Rosemary Hill, observes:

2A screen, partially veiling the sanctuary, attracts the gaze and at the same time resists it, emphasising both the centrality and the impenetrable mystery of the Mass. It is medieval but also picturesque, creating the views between “unequal varieties of space, divided but not separate” that Payne Knight defined as the essence of the picturesque in Gothic buildings.2

To see partially, and to mediate seeing through a threshold of imagery connected to what is seen and what is hidden, is the primary function of a rood or choir screen. How that gaze towards the altar, and therefore the gaze directed towards the Eucharist, is inflected by devotion and liturgical process in the Victorian era, depends on the medievalist–modern programme assembled by the screen designer. This contemporary practice of interweaving references from past and present created particular effects within and upon the worshipping community on both sides of this potent architectural sculpture.

Despite attending to numerous voices in the Gothic Revival screen debate, this study is in no way exhaustive. Because little academic attention has been paid to screens as a liturgical and visual cultural phenomenon in their own right, I instead place key historic points of reference into conversation with the Hereford Screen before and after its production. The reception of Victorian screens has not always been positive: over the past couple of generations many were destroyed or removed like the Hereford Screen itself, as the Church shifted its liturgical, theological, and therefore architectural views. The enduring consequence of the screen debates, which centred on whether they were obstructive or conducive to worship and liturgical development, as well as their general status as signs of the Gothic Revival’s reworking of pre-Reformation theological themes, has been often to perceive rood and choir screens as an inhospitable barrier rather than a holy threshold. They became less manifestations of wonder and more expressions of division.

Rood and choir screens have a significant place within the ongoing and rich discourses surrounding the survival of Victorian sculpture and sacred interiors. The exhibition Sculpture Victorious: Art in an Age of Invention, 1837–1901 (2014–15) and its landmark catalogue, explored Christian art extensively and discussed monuments in fresh new ways. But this is an exception—more often the scholarship has been limited to George Gilbert Scott’s Albert Memorial and descriptions of the major figures of the Gothic Revival movement, without sufficient attention paid to religious contexts. Broadly, church interiors and the unique architectural sculpture of rood and choir screens have been overlooked.3

3In the Gothic Revival, there was no intention to replicate an object from the Middle Ages with exact precision. The screens presented here, and the Hereford Screen in particular, are resurrections and reconsiderations of the vast histories of European rood and choir screens rather than exercises in copying and reconstruction. Architects used a medieval architectural toolkit to create spaces that suited Victorian understandings of God, devotion, and the crucial role of Christian art and architecture in framing worship. These points are illustrated in three short films that accompany this study, which were produced at St Cyprian’s, Clarence Gate in London; All Saints’, Jesus Lane in Cambridge; and at the Hereford Screen itself in the V&A.

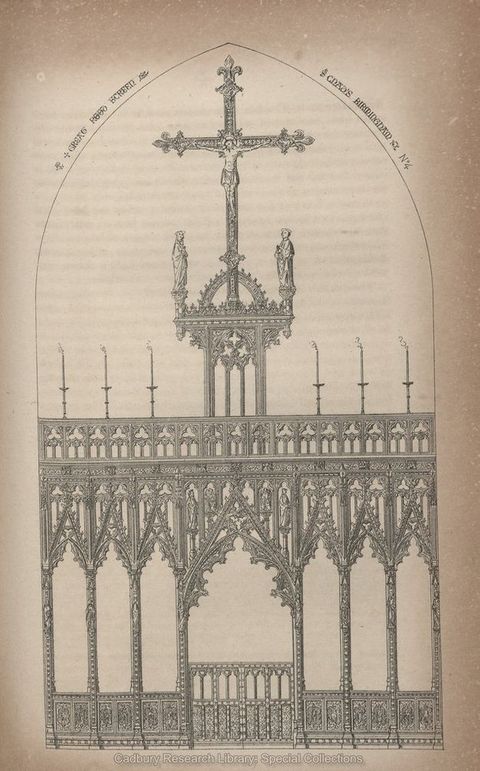

Pugin wrote the Present State of Ecclesiastical Architecture in England in 1843. Within this book he illustrated one of his most prominent rood screen designs, explaining its combination of older and newer elements into a single whole. Drawing medieval and Victorian designs together into an ideal composite, the screen constituted a kind of manifesto for the prospect of their revival as a type of liturgical, sacred architectural sculpture, drawing on medieval models and allowing them to speak afresh to a Victorian Christian public. Of this screen, for St Chad’s in Birmingham (fig. 1), Pugin wrote:

The great rood was certainly one of the most impressive features of a Catholic Church; and a screen surmounted with its lights and images, covered with gold and paintings of holy men, forms indeed a glorious entrance to the holy place set apart for sacrifice. We have here introduced an etching of the great screen and rood lately erected in the Cathedral Church of St. Chad, Birmingham, and which will afford a tolerable idea of the sublime effect of the ancient roodscreens, before their mutilation under Edward the Sixth. The images are all ancient and were procured from some of the suppressed continental abbeys; the crucifix itself is of the natural size, and carved with wonderful art and expression; the images of our blessed Lady and St. John are less in proportion, which is quite correct. Immediately under tracery panels in front of the loft, are a series of ancient sculptures; the centre of which represents the consecration of St. Chad, patron of the church, the other refers to the life and glories of St. John the Baptist. On the mullions between the open panels, on foliated corbels, are eight images of prophets. The rood is richly gilt and painted, and it is proposed to continue the same decoration over the screen itself.4

4

St Giles’, Cheadle (fig. 2) also gives a flavour of Pugin’s ideals for rood screens in the 1840s, at the height of his short career. One of his final publications before his death in 1852 was a treatise on Chancel Screens and Rood Lofts. Here, Pugin laid out his beliefs regarding best design practice by taking the reader on a geographical tour of European screens across Germany, France, and Britain. The book concludes, delightfully, with a polemical discussion of four types of iconoclasts and their screen-breaking motivations, based on Pugin’s perception (from his Gothic Revival and stridently Catholic point of view) of their own distorted ideology and its violent results. He names them as Calvinist, Pagan, Revolutionary, and Modern. Regarding the latter, Pugin wrote:

5The principal characteristics of modern ambonoclasts may be summed up as follows:—Great irritability at vertical lines, mutations of screens, or transverse beams and crosses; a perpetual habit of abusing the finest works of Catholic antiquity and art . . . they require great excitement in the way of lively, jocular, and amatory tunes at divine service, and exhibit painful distress at the sound of solemn chanting or plain song . . . unlike their predecessors, [they] confine their attacks to strokes of the pen; and we do not believe that they have hitherto succeeded in causing the demolition of a single screen.5

One of Pugin’s most impactful projects was the design for the Medieval Court at the Great Exhibition in 1851. Screens played a key role in it, and his Caen stone rood screen for the chapel of St Edmund’s College in Ware, Hertfordshire, was something of a manifesto, matching his beliefs as laid out in his publications on chancel screens and rood lofts. The screen is seven bays long and houses two altars. It combines stone and wood, with the rood itself being carved of pine and polychromed.6

6For Pugin, as many historians have observed, the Gothic Revival was no mere stylistic architectural endeavour, but a moral imperative, and a personal passion that spread out through Church and civic commissions to become a national conviction. The Gothic Revival itself was also far from monolithic and could be selectively shaped and instrumentalized by those designers who understood that Gothic was a style across hundreds of years and myriad cultures that one could combinatively deploy with dexterity and historically informed care. Not everyone saw it that way, however. There was also a tendency, among Gothic’s detractors as well as its promoters, to view the Gothic Revival as a fixed entity which one either complied with or digressed from, only to be found lacking. A challenge to Pugin’s role in its promotion, and an insight into the Revival more broadly, came from John Henry Newman, who wrote:

7Mr Pugin is notoriously engaged in a revival—he is disentombing what has been hidden for centuries amid corruptions; and, as, first one thing, then another is brought to light, he . . . modifies his first views, yet he speaks as confidently and dogmatically about what is right and what is wrong, as if he had gained the truth from the purest and stillest founts of continuous tradition . . . Gothic is now like an old dress, which fitted a man well twenty years back but must be altered to fit him now . . . I wish to wear it, but I wish to alter it, or rather I wish him to alter it.7

Alteration, adjustment, and “refinement” (the latter the term preferred by the late Victorian architect George Frederick Bodley) both defined and problematized the Gothic Revival’s pull on attention for sacred British architecture.8 For George Frederick Bodley, Scott’s first architectural pupil and one of his most successful, as well as a co-founder of the furnishings and fittings firm Watts and Company, rood screens were a key element of church interiors. This is exemplified by the screen in All Saints’, Jesus Lane in Cambridge—a church project largely regarded as Bodley’s turning point towards the values of the Aesthetic Movement as well as the attractions of fourteenth-century English Gothic. The screen adheres to multiple aspects of Pugin’s preferred approach but does not go so far as to create a rood. It is a choir screen, with a bare cross featuring emblems of the Four Evangelists at its ends. The life of Christ revealed through scripture is the focus of this liturgical sacred sculpture.

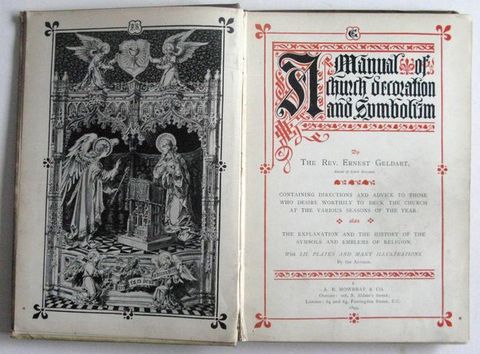

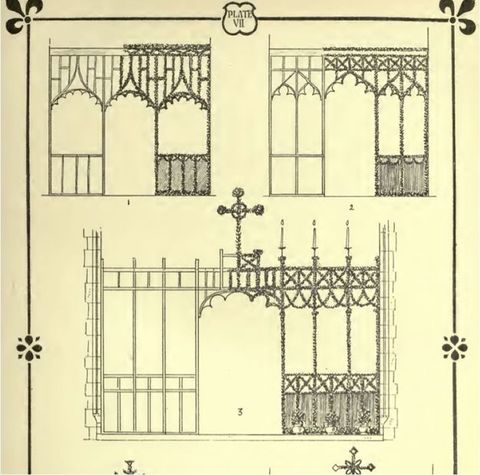

8A significant Gothic Revivalist who, like Bodley and Pugin, was also closely involved in a vast range of designs for sacred decorative arts and furnishings, was the priest–architect Ernest Geldart.9 In his Manual of Church Decoration and Symbolism (fig. 4) published in 1899 as a practical guide, with its own share of Anglo-Catholic polemic, Geldart suggested that the screen was an opportunity to bring into play temporary rood decorations that conveyed the eschatological vision of the Eucharist. Aware of the regular appearance of choir screens without roods (fig. 5), Geldart ventured that it could work well to include

910a tentative cross, whether hung at the chancel arch, or placed upon a screen that lacks its Rood. Here, since a screen does not inevitably imply a Rood, the occasional or periodic introduction of a temporary cross need not indicate a hesitating or temporizing policy. But it is a perfectly fair trial to see if it looks well, and if, in the best sense of the word, “it pleases the people.”10

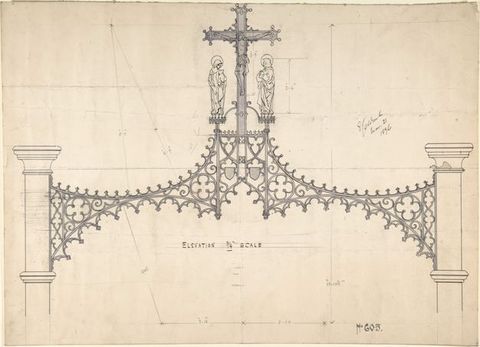

Geldart’s own designs included rood beams rather than full screens, and in 1896 he designed one which could have been produced either in wood or metal, high above the steps between chancel and nave. It was never built.11

11

Variations on rood and choir screens continued into the twentieth century. A handbook published in 1932 by the Warham Guild furnishings company provides a window onto how the debate developed: “At the present time there is a reaction against the erection of any kind of barrier or screen between the altar and congregation. Nevertheless it should not be assumed that a screen should never be erected.”12 The handbook offers a brief history of screens and concludes that gilt and colour should be used wherever possible. The text expresses strong admiration for East Anglian late medieval screens like the ones so highly regarded by William Morris and Bodley, as well as by Comper, particularly in his designs for St Cyprian’s, Clarence Gate. These late Gothic survivors had often been subject to iconoclastic attacks in history too, and the melancholic and indeed violent slashes through painted faces of saints and angels, exposing the grainy ancient wood beneath, served as a stark reminder to Victorian and later screen designers about the power of these liturgical artistic objects to provoke.

12Iconoclasm, restoration, and medievalism formed a tripartite foundation for the debates that raged across the long nineteenth century regarding the blending of old and new Gothic material and the manner in which this might be done. A dedication plaque in Winchester Cathedral attests to one method of recollection mixed with innovation:

13The great altar screen of this cathedral church was erected in the course of the XVth Century. In the year 1538 it was grievously mutilated and despoiled of the figures which adorned it. In succeeding ages it was subjected to various tasteless alterations until its original beauty was almost entirely effaced. In the year 1885 the restoration of the central portion was begun . . . The work thus far accomplished . . . on the vigil of the annunciation, the figure of our blessed Lord together with the enrichments of the cross . . . were dedicated, thus completing as far as possible the restoration of the screen to its original condition of glory and beauty.13

The desire to return to a medieval ideal, albeit with a Victorian twist, resulted in rood and choir screens being carefully studied from around the mid-nineteenth century onwards for aspects of detail in colour, materials, decorative forms, and geometry as well as in their general principles and dominant iconography. An 1875 drawing by Walter Lewis Spiers (fig. 6) demonstrates the interest in East Anglian colour at St Agnes Church at Cawston in Norfolk, which could be transferred not only to new designs in painted wood but into fuller and more diverse schemes for the Victorian church, from painted ceilings to palettes for ecclesiastical textiles.

The Scottish architect John Ninian Comper made careful study of these rood screens—and Ranworth in particular—blending their dominant characteristics with his own unique way of combining classicism and Gothic, and earlier and later periods of church design. A near-contemporary of his work, inspired by East Anglian Gothic at St Cyprian’s, Clarence Gate in London, is at All Saints at St Ives in Cambridgeshire, where the rood is uniquely (to the best of my knowledge) integrated with the organ (fig. 8). Comper’s study of rood screens also encompassed Spanish traditions of rejas. His inter-war metalwork screens looked back less to Scott and Skidmore than to Early Modern Spanish metalwork, as at St John’s, Stockcross, completed in 1933. Comper was perhaps the most experimental, if not the most politically controversial of the rood screen designers considered here. At St Mary’s, Wardleworth, Comper combined a detailed approach to a Gothic English rood screen, complete with sculptures of saints in niches below the rood, with an unusual placement of a Pantokrator figure on the beam directly above the screen. In doing so, he was directly inspired by rood beams (where the rood sits on the beam but there is no screen), though instead of the crucified Christ he reinvented the form, answering the suffering of Jesus on the rood with the triumph of Christ in heaven on the additional beam. At St Cyprian’s, Clarence Gate, the rood screen, the chancel arch’s Christ in majesty, and the further imagery of Christ as Pantokrator above the altar, all inserted into the church by Comper across a period that spanned decades, creates a programme that charts Christ’s Passion through to his resurrection across a concentrated space between the nave and the altar, with the relatively unadorned chancel between. Christ on the cross of the rood as entry-point to Christ as victorious over all creation is regarded as an opportunity for meditation: in the words of the Lenten Triodion, “Today He who hung the earth upon the waters is hung on the Cross. He who clothes himself in light as in a garment stood naked at the judgement.”14

14Where does this leave Scott’s own theological context for the development of the choir screen at Hereford Cathedral? The image of the Pantokrator-type Christ in blessing allowed for a depiction of triumph and resurrection that avoided Catholic-leaning theology which might dominate the screen’s Anglican message, but it was not necessarily drawing upon Eastern Orthodox Greek visual culture in the way that Comper’s Pantokrator figures eventually would. Rather, it is the language of cathedral portals, and thresholds between exterior and interior in western Europe that Scott seemed to channel most closely in his translation from stone to metalwork leading up to the 1862 International Exhibition. In Scott’s autobiographical Personal and Professional Recollections he wrote little about screens despite encountering a great number of medieval and modern examples across a long career. One of the few mentions he makes of rood screens in his autobiography concerns a restoration project undertaken in Chesterfield, in which he “found the rood screen to have been pulled down and sold, but we protested, and it was recovered”.15 Similarly, he praised German churches in which roods had been retained.16 As a rule, in Scott’s church and cathedral restoration work, he would leave existing screens in place. Regarding his own work at Hereford, he outlined the tensions between his design and Skidmore’s execution, concerned that Skidmore’s “eccentricity” had allowed for the final product to deviate from its historicist purpose. He worried that the screen represented innovative decoration for its own sake rather than applying new techniques and materials to reinterpreted medieval models.17 Not everyone was convinced by the effort, particularly the sharply critical minor architect J. T. Emmett, who believed that “the screens at Lichfield and Hereford are sufficient monumental records of the audacity of an architect and of the simplicity of his employers.”18

15In her 2014 study of Scott, Claudia Marx pointed out that in Scott and Skidmore’s collaborations at Lichfield, Salisbury, and Hereford, the insertion of ironwork screens was at sites “wherever an ancient pulpitum was missing”.19 This is an interesting light in which to view these screens: their ironwork lattice creates nothing like a pulpitum replacement, but rather a distinctively Victorian medievalist echo, not only asserting Scott and Skidmore’s own unique modern medievalist design language in motifs, iconography, and—crucially—materials and techniques, but also going about this task such that the particularly skeletal qualities of ironwork created a kind of gloriously luminous aesthetic that echoed earlier iterations of heftier medieval screens in stone and wood. This effect may in part be Scott and Skidmore’s way of referencing the monumental architectural thresholds created by older pulpitum formations in these cathedrals and elsewhere in Europe (such as those explored by Jacqueline Jung in her contribution to this One Object project).

19The presence of a crucified Christ in a Victorian space in the form of a rood screen demanded different theological responses from Christian worshippers than the image of a resurrected one, or indeed of a cross upon a screen alone. Indeed, the elements in these screens were also combined in different ways with additional symbolism, such as in the screen at All Saints’, Jesus Lane in Cambridge, in which the cross on the uppermost portion of the screen is surrounded by emblems of the Bible and Christian tradition in the form of the symbols of the four Evangelists. This was an alternative for choir screens, in place of a medieval rood sculptural group that focused upon the specific biblical account of Christ’s mother and the Beloved Disciple as mourning witnesses of Christ’s death. In his 2009 work on modern imagery of crucifixion and resurrection, the theologian George Pattison writes: “The new creation to which Christian theology bears witness, the new creation brought about in and by ‘Christ and him crucified’ . . . is a new creation of a world and a history that has been degraded and diminished by suffering, violence and every possible manifestation of sin.” Pattison believes that concentrating of artistic attention on the cross is a key element of meditating upon its status as a kind of hinge—an event through which all this suffering is utterly redeemed, transformed, and recollected into the dying (and subsequently rising) Son of God. As he explains, the cross “is the reversal of the quantitative accumulation of nothingness that has so long overwhelmed our individual and collective aspirations to something better”.20

20Seeking to contemplate the Passion through a medieval lens with renewed clarity for a modern world, the Victorian period also saw a rise in medieval revivals of devotional poetry and hymnody. The two most relevant to the revival of rood screens are the late eighth-century The Dream of the Rood and the sixth-century hymns of Venantius Fortunatus, translated by John Mason Neale for the English Hymnal in the early 1850s. The latter’s Vexilla Regis Prodeunt focuses on the dazzling beauty and light of the cross as a living, fruitful source of life for all, paradoxically weaving together the suffering of the Passion and the promise of salvation for all through Christ. In The Dream of the Rood, the cross itself speaks: “I tower/ High and mighty beneath the skies, having power to heal/ Whosoever shall bow to me.” As liturgist Christopher Irvine explains, “Because the cross in this Old English poem represents the bloody scene of Christ’s victory, so it is transmuted into a tree of beauty, a tree that bore the king in his dazzling splendour.”21 This connects with Merleau-Ponty’s stance of vision as an experience of proceeding forth, a journeying outwards, in order to attend afresh to what he calls the “Being within”.

21Representations of Christ’s crucified body remind worshippers that transformation is imminent through the divine nexus of profound love and horrendous suffering. The presence of a Christ in majesty, in the act of blessing—as in the Hereford Screen—provides a slightly different Christological message, that the ascended Christ protects and cares for all God’s people, promising God’s glory and the bodily resurrection to the faithful. In Scott’s case, the re-introduction of choir screens allowed for a renewed expression of medievalism to come into contact with modern needs in the Church and in industrial and artistic processes. This was different from the motivations of Pugin, Bodley, or Comper, though somewhat closer to Geldart’s view regarding materials and details in the embellishment of screens. Most significantly, for all three architects innovation in design came through stylistic and iconographic means. The emphasis on the modern, the fresh, and the invigorating for new outlooks on art and religion was captured in the praise of the Illustrated London News when the Hereford Screen was exhibited at South Kensington in 1862: it was “the most noble work of modern times . . . a monument of surpassing skill of our land and our age.”22 For Scott in his work with Skidmore in particular, the chief innovating factor rested with the deployment of materials, despite his concern that novel eccentricities had resulted from losses in translation. For each of these architects who created rood and choir screens, and inserted sacred thresholds declaring Christ’s presence in the Eucharist and in the heart of the worshipper in a variety of text and image combinations, the role of the screen—whether depicting the crucified or the risen Christ—was a foundational element in the many iterations of modern British medievalism."

22About the author

-

Ayla Lepine is an art and architectural historian whose work focuses on the Gothic Revival and intersections of theology and the arts. Following her PhD at the Courtauld Institute of Art, she held fellowships at the Courtauld Research Forum and Yale’s Institute of Sacred Music. Her publications include Revival: Memories, Identities, Utopias (2015) and Gothic Legacies (2012), as well as articles on the reception of the Middle Ages in modern Britain in Architectural History and Visual Resources. She is completing a book on expressions of medievalism in modern transatlantic cities. She is Arts Editor for Marginalia Review of Books and a trustee of Art and Christianity Enquiry and David Parr House in Cambridge. She is a Fellow in Art History at the University of Essex and an Ordinand at Westcott House.

Footnotes.

Bibliography

Bettley, James. “The Reverend Ernest Geldart and Late Nineteenth-Century Church Decoration.” PhD Thesis, Courtauld Institute of Art, London, 1999.

Brown, Ingrid. “The Hereford Screen.” Ecclesiology Today 47/48 (July 2013): 3–44.

Droth, Martina, Jason Edwards, and Michael Hatt. Sculpture Victorious: Art in an Age of Invention, 1837–1902. New Haven, CT, and London: Yale University Press, 2015.

Geldart, Ernest. A Manual of Church Decoration and Symbolism. Oxford and London: A. R. Mowbray & Co., 1899.

Hall, Michael. George Frederick Bodley and the Late Victorian Gothic Revival in Britain and America. New Haven, CT, and London: Yale University Press, 2014.

Hill, Rosemary. God’s Architect: Pugin and the Building of Romantic Britain. London: Allen Lane, 2007.

Irvine, Christopher. The Cross and Creation in Christian Liturgy and Art. London: SPCK, 2013.

The Lenten Triodion. Ed. Mother Maria and Bishop Diokleia Kallistos. Waymart, PA: St Tikhon’s Seminary Press, 2002.

Marx, Claudia. “Scott and the Restoration of Major Churches.” In Sir George Gilbert Scott, 1811–1878, ed. P. Barnwell, G. Tyack, and W. Whyte. Donington: Shaun Tyas, 2014.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. “Eye and Mind.” In The Primacy of Perception, ed. James Edie. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1964, 159–90.

Newman, John Henry. The Letters and Diaries of John Henry Newman, Vol. 12: Rome to Birmingham, ed. C. S. Dessain. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1962.

Pattison, George. Crucifixions and Resurrections of the Image: Christian Reflections on Art and Modernity. London: SCM, 2009.

Pugin, A. W. N. A Treatise on Chancel Screens and Rood Lofts. London: Charles Dolman, 1851.

– – –. The Present State of Ecclesiastical Architecture. London: Charles Dolman, 1843.

“Roman Catholic Chapel of St Edmund’s College”, Historic England https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1308305 (accessed 5 Jan. 2017).

Scott, George Gilbert. Personal and Professional Recollections. Ed. G. Gilbert Scott. London: Sampson Low, 1879.

Stamp, Gavin. Gothic for the Steam Age: An Illustrated Biography of George Gilbert Scott. London: Aurum, 2015.

The Warham Guild Handbook. London: Mowbrays, 1932.

-

1

Maurice Merleau-Ponty, “Eye and Mind”, in The Primacy of Perception, ed. James Edie (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1964), 186. ↩︎

-

2

Rosemary Hill, God’s Architect: Pugin and the Building of Romantic Britain (London: Allen Lane, 2007), 201. ↩︎

-

3

Martina Droth, Jason Edwards, and Michael Hatt, Sculpture Victorious: Art in an Age of Invention, 1837–1902 (New Haven, CT, and London: Yale University Press, 2015). ↩︎

-

4

A. W. N. Pugin, The Present State of Ecclesiastical Architecture (London: Charles Dolman, 1843), 78. ↩︎

-

5

A. W. N. Pugin, A Treatise on Chancel Screens and Rood Lofts (London: Charles Dolman, 1851), 98–99. ↩︎

-

6

“Roman Catholic Chapel of St Edmund’s College”, Historic England https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1308305 (accessed 5 Jan. 2017). ↩︎

-

7

John Henry Newman to Ambrose Philipps, in The Letters and Diaries of John Henry Newman, Vol. 12: Rome to Birmingham, ed. C. S. Dessain (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1962), 221–22. ↩︎

-

8

For a full account of Bodley’s career, see Michael Hall, George Frederick Bodley and the Late Victorian Gothic Revival in Britain and America (New Haven, CT, and London: Yale University Press, 2014). ↩︎

-

9

For a full account of Ernest Geldart, see James Bettley, “The Reverend Ernest Geldart and Late Nineteenth-Century Church Decoration”, PhD Thesis, Courtauld Institute of Art, 1999. ↩︎

-

10

Ernest Geldart, A Manual of Church Decoration and Symbolism (Oxford and London: Mowbray & Co., 1899), 45. ↩︎

-

11

My thanks to James Bettley for confirming this. ↩︎

-

12

The Warham Guild Handbook (London: Mowbrays, 1932), 50–52. ↩︎

-

13

Inscription at Winchester Cathedral next to the screen. ↩︎

-

14

Mother Maria and Bishop Diokleia Kallistos, eds., The Lenten Triodion (Waymart, PA: St Tikhon’s Seminary Press, 2002), 582. ↩︎

-

15

George Gilbert Scott, Personal and Professional Recollections, ed. G. Gilbert Scott (London: Sampson Low, 1879), 96. ↩︎

-

16

Scott, Personal and Professional Recollections, 139. ↩︎

-

17

Scott, Personal and Professional Recollections, 216. ↩︎

-

18

Quoted in Gavin Stamp, Gothic for the Steam Age: An Illustrated Biography of George Gilbert Scott (London: Aurum, 2015), 18. ↩︎

-

19

Claudia Marx, “Scott and the Restoration of Major Churches”, in Sir George Gilbert Scott, 1811–1878: An Architect and His Influence, ed. P. Barnwell, G. Tyack, and W. Whyte (Donington: Shaun Tyas, 2014), 98. ↩︎

-

20

George Pattison, Crucifixions and Resurrections of the Image: Christian Reflections on Art and Modernity (London: SCM, 2009), 54. ↩︎

-

21

Christopher Irvine, The Cross and Creation in Christian Liturgy and Art (London: SPCK, 2013), 119. ↩︎

-

22

Illustrated London News, quoted in Ingrid Brown, “The Hereford Screen”, Ecclesiology Today 47 & 48 (July 2013): 3. ↩︎

Imprint

| Author | |

|---|---|

| Date | 10 April 2017 |

| Category | One object |

| Review status | Peer Reviewed (Editorial Group) |

| License | Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) |

| Downloads | PDF format |

| Article DOI | https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-05/alepine |

| Cite as | Lepine, Ayla. “Theology and Threshold: Victorian Approaches to Reviving Choir and Rood Screens.” In British Art Studies. London and New Haven: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art and Yale University Press, 2017. https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-05/alepine. |