Pilgrim Souvenir

Pilgrim Souvenir: Hood of Cherries

By Amy Jeffs

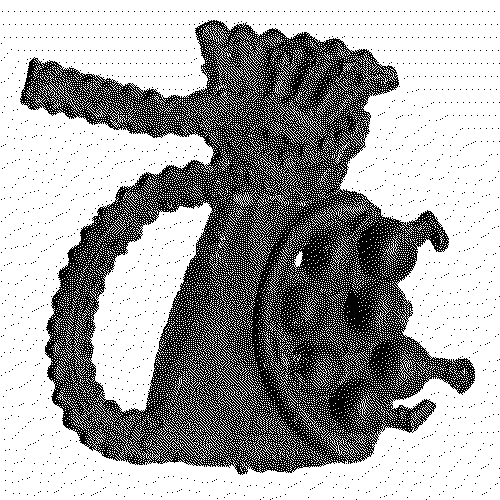

This lead alloy badge from the British Museum represents a medieval hood repurposed as a sack for a harvest of cherries (fig. 2).1 It measures 38 by 30 millimetres and was cast integrally with its pin and clasp in a three-part mould.2 When first made, it would have shone like silver. Badges were purchased in their millions by pilgrims between the late twelfth and early sixteenth centuries, as attractive, wearable and cheap souvenirs of their visits to holy sites (fig. 3). By the later Middle Ages badges were also worn as general symbols of devotion, as livery insignia, and as humorous or amorous tokens; which of these categories the “hood of cherries” badge falls into is debatable. Five of them have been found: three in Salisbury, and another in London (fig. 4), while the provenance of the fifth is unknown.3 Their cataloguers reluctantly associate them with the cult of St Dorothy, whose emblem is a basket of fruit, although Spencer expressed concern that, “a fashionable hood seems far removed from her story.”4 There are also possible alternative explanations to its meaning, which will be explored here.

1

A fifteenth-century date can be suggested based on the style of the hood.5 It has a gorget (a collar for the neck) and a tippet (the long band of fabric that replaced the tubular liripipe). These are both decoratively dagged and the hole for the face has a rolled rim, suggesting that it may represent a kind of hood called a chaperon, which was worn on the head: the fifteenth-century descendant of the fourteenth-century gorget, hood, and liripipe.

5

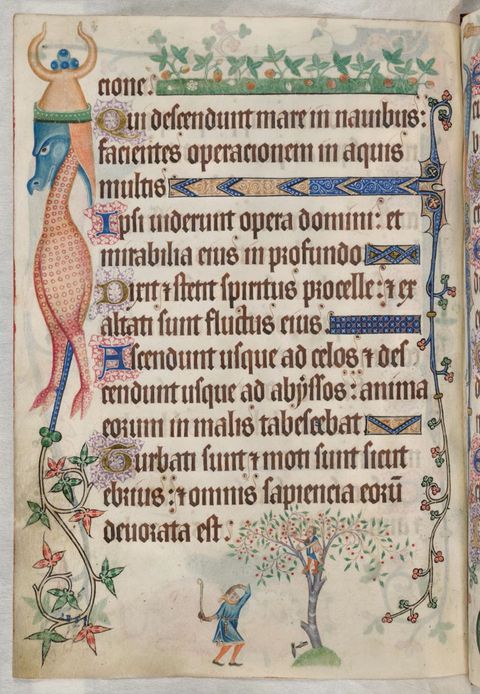

On all the surviving examples, the seven fruits can be tentatively identified as cherries from their long, sometimes paired, stems. A separate source exists to support this conclusion. On folio 196v of the early fourteenth-century Luttrell Psalter, alongside other familiar or popular scenes of country life (fig. 4), a thief is shown scrumping from a cherry tree. He is depicted in the tree with his liripipe hood back-to-front, filling it with cherries. The illuminator is careful to render the tree’s leaves, bark, and ripening fruit identifiable. The hood of cherries on the badge may therefore be interpreted as visually referencing a spontaneous harvest of cherries.

Just such a harvest was a motif central to a story that enjoyed a short burst of popularity during the second half of the fifteenth century, when all five of these badges were probably made. It features at the beginning of the N-Town mystery play for the Nativity (lines 24–44).6 In the story, Joseph and the pregnant Mary are travelling to Bethlehem. They notice a tree miraculously bearing cherries out of season. She asks Joseph to pick some for her but he responds irritably that the one who got her pregnant should harvest them, not him (this line also becomes the refrain in the derivative “Cherry Tree Carol”). At God’s command, therefore, the cherry tree bends and Mary is able to gather her fill of the fruit.

6The motif of the Virgin’s unexpected glut of cherries was popular in England during the period of this badge-type’s production, and appeared in other visual and literary works.7 Whether or not it furnished the imagery of this badge, the scrumped harvest of cherries is an effective natural metaphor for unexpected wealth, as the rare four-leaf clover is for good luck. As new research explores the many mysterious iconographies borne by medieval pilgrims’ souvenirs and secular badges, the “hood of cherries” badge is a testament to how much may be learned from their study alongside the elite art and popular literature of the Middle Ages.

7About the author

-

Amy Jeffs is a PhD candidate at the University of Cambridge. Her research focusses on a 14th-Century English illustrated manuscript of histories and romance (BL Egerton 3028). She is co-convenor of the Digital Pilgrim Project.

Footnotes

-

1

London, British Museum, objects nos. 1856,0923.7; 1856,0701.2114. That the orientation of the badge as depicted above is correct is shown by the direction of the pin on the reverse (the clasp is always at the bottom when the pin is vertical). ↩︎

-

2

The casting process can be seen in this video clip shot by the Digital Pilgrim Project in collaboration with Colin Torode of Lionheart Replicas.. ↩︎

-

3

The find-spot of 1856,0923.7 is unknown, but the other was found in London. The other three surviving examples were all found in Salisbury. As well as the two at the British Museum, see B. Spencer, Pilgrim Souvenirs and Secular Badges (London: HMSO, 1998), 102, cat. nos. 170–71 (142/1978 & 190w/1987, Salisbury & South Wiltshire Museum); M. Mitchiner, Medieval Pilgrims and Secular Badges (London: Hawkins, 1986), 96, cat. no. 219. ↩︎

-

4

Mitchiner, Medieval Pilgrims, 96; Spencer, Pilgrim Souvenirs, 102, cat. no. 171; http://www.kunera.nl/ (accessed 11 August 2016), two badges depicting baskets full of fruit have been found in London and one in Salisbury. On these badges, the fruits are very numerous and there is no consistency in the type or number of fruits depicted. ↩︎

-

5

I. Brooke, Illustrated Handbook of Western European Costume: Thirteenth to Mid-Nineteenth Century (Mineola, NY: Dover, 2003), 19–20; K. M. Lester and B. V. Oerke, Accessories of Dress: An Illustrated Encyclopedia (Mineola, NY: Dover, 2004), 12. ↩︎

-

6

S. T. Carr, “The Middle English Nativity Cherry Tree: The Dissemination of a Popular Motif”, *Modern Language Quarterly *36, no. 2 (1975): 140. ↩︎

-

7

The cherry tree motif in medieval English art will be explored by the author in a future article. ↩︎

Bibliography

Primary Sources

London, British Museum, objects nos.: 1856,0923.7; 1856,0701.2114

London, British Library, Cotton Vitellius D VIII (The N-Town Plays)

London, British Library, Add MS 421430 (The Luttrell Psalter)

Secondary Sources

Brooke, I. Illustrated Handbook of Western European Costume: Thirteenth to Mid-Nineteenth Century. Mineola, NY: Dover, 2003.

Carr, S. T. “The Middle English Nativity Cherry Tree: The Dissemination of a Popular Motif.” Modern Language Quarterly 36, no. 2 (1975): 133–47.

Lester, K. M., and B. V. Oerke. Accessories of Dress: An Illustrated Encyclopedia. Mineola, NY: Dover, 2004.

Mieszkowksi, G. Medieval Go-Betweens and Chaucer’s Pandarus. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006.

Mitchiner, M. Medieval Pilgrims and Secular Badges. London: Hawkins, 1986.

Spencer, B. Pilgrim Souvenirs and Secular Badges. London: HMSO, 1998.

Imprint

| Author | |

|---|---|

| Date | 29 June 2017 |

| Category | One Object |

| Review status | Peer Reviewed (Editorial Group) |

| License | Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) |

| Downloads | PDF format |

| Article DOI | https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-06/cherries-badge |

| Cite as | Jeffs, Amy. “Pilgrim Souvenir: Hood of Cherries.” In British Art Studies: Invention and Imagination in British Art and Architecture, 600–1500 (Edited by Jessica Berenbeim and Sandy Heslop). London and New Haven: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art and Yale University Press, 2017. https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-06/cherries-badge. |