Imagining Place and Moralizing Space

Imagining Place and Moralizing Space: Jerusalem at Medieval Westminster

By Laura Slater

Abstract

Monuments and landscape ensembles across medieval Europe recreated the Christian holy places of Jerusalem for local devotees. Contemporary legends surrounding the death of King Henry IV in 1413, who died in the Jerusalem Chamber in the abbot’s house at Westminster Abbey, place the room firmly within this cultural tradition. In the sixteenth century, a neighbouring Jericho Parlour was built. This paper highlights the political significances of such “recreated Jerusalem” sites: in contrast to the religious and demographic diversity found in the earthly city, and in connection with European crusading and imperial ambitions. Exploring the “death in Jerusalem” topos in detail, it argues that the Jerusalem Chamber should not be understood as a recreated holy place. Instead, the links to the Holy Land found in the abbot’s house form part of an imaginative reinvention of space within medieval Westminster, deliberately intended to provoke moral admonition and self-scrutiny in its users.

Death, Kings, and Jerusalem: A Medieval Topos

In one of the first accounts of a scene later immortalized by Shakespeare,1 written almost contemporaneously in 1413–14, Adam Usk recorded that on 20 March 1413, “after fourteen years of powerful rule . . . the infection which for five years had cruelly tormented Henry IV with festering of the flesh, dehydration of the eyes, and rupture of the internal organs, caused him to end his days, dying in the sanctuary of the abbot’s chamber at Westminster, whereby he fulfilled his horoscope that he would die in the Holy Land”.2 The author of the Brut, writing about 1430, expanded the scene further.3 Henry had ordered the construction of galleys of war in which to sail to Jerusalem and end his life in the Holy Land.4 Struck by illness, the king:

1

“King. Doth any name particular belong

Unto the lodging where I first did swoon?

Warwick. 'Tis called Jerusalem, my noble

lord.

King. Laud be to God! even there my life must

end.

It hath been prophesied to me many years,

I should not die but in Jerusalem;

Which vanity I supposed the Holy Land:

But bear me to that chamber, there I’ll lie,

In that Jerusalem shall Henry die.”

“King. Doth any name particular belong

Unto the lodging where I first did swoon?

Warwick. 'Tis called Jerusalem, my noble

lord.

King. Laud be to God! even there my life must

end.

It hath been prophesied to me many years,

I should not die but in Jerusalem;

Which vanity I supposed the Holy Land:

But bear me to that chamber, there I’ll lie,

In that Jerusalem shall Henry die.”

5was yn Bedde at Westmynstre yn a faire Chaumbre; and as he lay abedde, he axed his Chaumbirleyn what he callyd that Chaumbyr þ[th]at he lay-ynne; he answarde and sayde “Ierusalem”. [Th]þanne he sayde, his prophecie sayde “he schulde make an ende and deye yn Ierusalem.” And þ[th]an he made hym redy unto God, & disposed alle his wille, and sone aftir he deyed . . .5

As Anthony Bale has noted, to die in Jerusalem was to die well, with crusading or eschatological return to Jerusalem forming part of the famous medieval “good death”.6 The twisted fulfilment of prophecies of death in Jerusalem subverted this idea. The tale forms a commentary on princely ambition, stressing the transience and limits of worldly power and glory. It was a medieval topos concerned with the fall of the mighty: Pope Sylvester II had his death in Jerusalem foretold by a devil and died at Santa Croce in Gerusalemme in Rome.7 Anna Comnena’s Alexiad, written about 1148, describes how Robert Guiscard’s death in Cephalonia was hastened by learning of a nearby town named Jerusalem: “many years before some soothsayers had prophesied to him the kind of thing flatterers are wont to tell princes, ‘As far as Ather you shall bring all countries under your sway, but from there you shall depart for Jerusalem and pay your debt to nature.’”8 According to John Barbour’s 1370s Bruce, a wicked spirit led Edward I to expect his death “in the burgh” of Jerusalem before the king died at Burgh-by-Sands near Carlisle in 1307.9 We can imagine the satisfaction for both authors in narrating such bathetic and frustrated ends to the lives of their foes.

6By spring 1414, when Adam Usk may have written the section of his chronicle on Henry IV’s death, he was not an unqualified supporter of the king.10 The schadenfreude with which he adapted the trope can only be guessed at, but restaging the anecdote reiterates its conventional themes, implying Henry’s limitless ambition and, in his leprous illness, the just judgement of God on the king for usurping and murdering his cousin, Richard II. Usk’s reference to Henry IV “dying in the sanctuary of the abbot’s chamber at Westminster” is factual: the abbot’s house at Westminster lay well within the boundaries of the monastic precinct, and the ancient legal right of sanctuary that residence within it entailed.11 But its mention may also obliquely comment on the sins of the king, who might well want to seek sanctuary at Westminster if involved in Richard’s murder. On the same theme, John Hardyng’s chronicle of about 1440 particularly stresses the king’s repentance for his sins on his deathbed.12

10Usk’s version of the tale may equally reflect the greater legitimacy that Henry enjoyed after over a decade of rule. By the fifteenth century, there was an especially strong link between the death of kings and Jerusalem. Louis IX of France was believed to have murmured “We will go unto Jerusalem” the night before his death.13 A contemporary elegy on the death of Edward I had the king bequeath his heart to the Holy Land, to accompany fourscore battle-hardened knights fighting against the heathen and winning the Cross, deeds that “myself ycholde gef that y myhte.”14 At his death in 1329, Edward’s enemy Robert the Bruce desired his heart to be buried at the Holy Sepulchre, and the ancient Saxon king Offa was believed to have died on his return from Jerusalem.15 The Anglo-Saxon holy king, Edward the Confessor, was also given notice of his forthcoming death from two English pilgrims. Lost in “Syria’” on their way to the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, they were rescued by St John the Evangelist, who guided them safely back to England to inform the king of his demise and salvation.16 Aelred of Rievaulx’s twelfth-century narrative has the pilgrims magically transported to Jerusalem, while Matthew Paris in the thirteenth century only implies the success of their journey.17 Westminster is the true goal of the pilgrims’ journey in both accounts, but the link between Jerusalem and a royal deathbed remains.

13This article begins by exploring the Jerusalem Chamber at Westminster and the royal deathbed legend surrounding it in the context of the enduring European tradition of recreating the Christian holy places in monumental form. Such sites were first and foremost places of devotion, designed to provoke the same complex nexus of memoria and affectio that characterized all Christian pilgrimages.18 I argue that European recreations of Jerusalem were also politically symbolic, embodying European aspirations to sovereignty over the Holy Land and closely related to medieval concepts of imperium.19 Yet the Jerusalem Chamber does not entirely conform to this tradition. Rather than being a site of “virtual pilgrimage”, I argue that the room was linked to Jerusalem by an imaginative reinvention of space within medieval Westminster, deliberately intended to provoke moral admonition and self-scrutiny in its visitors.

18The Political Meanings of Recreated Jerusalems

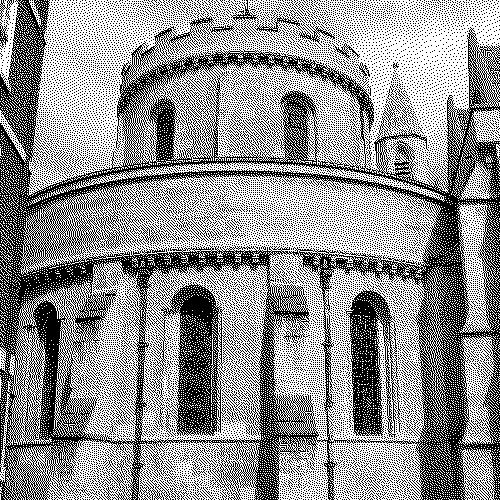

As a biblical relic, future site of the events of Revelation, and symbol of the heavenly city, Jerusalem defied all medieval distinctions of space, place, and time.20 Yet the “death in Jerusalem” topos plays on its uniquely translatable nature in quite a different way. The trap of the deceitful prophecies supposedly accepted by Robert Guiscard, Edward I, and Henry IV all relied on the frequency with which Jerusalem was multiplied through European place names, church dedications to the Holy Sepulchre or Holy Cross, and more ambitious monumental and topographical reproductions of its holy sites.21 Exemplified in England by famous surviving recreations of the Anastasis Rotunda, such as in the Cambridge Round Church (fig. 1), and in Scotland by the ruined circular-naved church of St Nicholas Orphir, on the Orkney island of Mainland, recreated Jerusalems have been understood primarily as sites of virtual or imagined pilgrimage.22 Local translations of the Holy Land provided a way of re-experiencing Christ’s Passion in a safe and familiar environment.23

20

I argue that these sites were laden with political meaning. Medieval visitors to the earthly Jerusalem arrived at a religiously, ethnically, and culturally diverse “global city” housing Christian, Islamic, and Jewish populations.24 In pilgrimage accounts, observation on the varietas of the city is a rhetorical commonplace. Around 1170, John of Würzburg noted the “great many chapels and churches . . . which hold people of every race and tongue”, that were too numerous for inclusion in his detailed description of the city.25 The pilgrim Theodoric, travelling c.1169–74, discussed the different Christian liturgies performed in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre by “the Latins, the Syrians, the Armenians, the Greeks, the Jacobins and the Nubians”.26 Thietmar, travelling c.1217–18, “began my journey with certain Syrians and Saracens through the land of Zebulun and Naphtali [Galilee]”.27 Burchard of Mount Sion recorded himself about 1274 “diligently questioning” the “Syrians, Saracens and other inhabitants of the land” to find out as much accurate information as possible.28 Syncretic religious sites encompassed all three Abrahamic faiths: twelfth-century Jewish pilgrimage accounts record Christian and Muslim visits to holy tombs, miracle stories involving Gentiles, and a possible visit to the Holy Sepulchre by the pilgrim Jacob b. Nathanel.29 At the tomb of the Prophet Jonah at Kfar Kana, R. Petaḥyah of Regensburg, writing c.1174–87, was welcomed and offered fruit by its Gentile guardian.30

24These encounters had little effect on the inter-faith tolerance of Western visitors. For example, the composite chronicle of Ernoul-Bernard, written about 1231 but using earlier, pre-1187 texts, refuses to discuss the Christians and Christian churches not in obedience to Rome.31 And while pilgrim accounts noted restricted access to the holy places after 1187, Willbrand of Oldenburg is exceptional in recording the conversion of the Church of the Ascension into a mosque in his 1211–12 account.32 Yet the range and variety of cross-cultural encounters in Palestine clearly constituted one of the most striking and memorable features of the pilgrimage experience, rippling through successive accounts of visits to Jerusalem.33However partially and reluctantly, textual representations of the Holy Land acknowledged the shared nature of Jerusalem loca sancta. The Latin settlers in the crusader kingdoms, the so-called pullani, were forced into a degree of practical co-existence with other faiths.34 Of necessity, even for a brief period, Latin visitors had to do the same.

31In texts, people may have acknowledged the shared and syncretic nature of Jerusalem and its holy places, but in images and monuments they did not. Architectural reproductions of the holy places in Europe did not recognize, much less incorporate, commemorate, or seek to recreate this devotional and religious diversity. As a result of medieval English demographics and of active ecclesiastical prohibitions against non-Christian visitors, no English churches of any type welcomed Islamic visitors, and after the Fourth Lateran Council, few, if any, Jews. As early as 1179 in England, the bishop of Worcester forbade Jews from storing goods in churches.35 The Oxford church synod of 1222, presided over by Stephen Langton, banned Jews from entering churches altogether.36 Visited overwhelmingly by Latin Christians, and celebrating only the Latin Christian mass, Jerusalem recreations guaranteed entry to an environment of doctrinal orthodoxy and liturgical familiarity. Performing no syncretic functions, they were places of religious uniformity and could act as affirmations of Christian unity, centred on obedience to papal Rome. Visiting Jerusalem at a local reinvention of the holy places thus involved deliberately marginalizing non-European and non-Christian worlds.

35After the fall of Jerusalem in 1187, and the loss of the final crusader kingdom of Acre in 1291, entry into European Jerusalem sites also allowed one to imaginatively return to political primacy in the Holy Land. Felix Fabri’s Sionpilger of about 1491–92, a day-by-day mental pilgrimage to Jerusalem, Rome, and Compostela composed for the sisters of the nunneries of Medingen and Medlingen in Ulm, Germany, put it thus:

37the Syon [imaginative] pilgrim has much more freedom than the knightly [physical] pilgrim. The knightly pilgrim visits Jerusalem as in a heathen city, but the Syon pilgrim visits Jerusalem as a Christian city, as though Christians possess the Holy Sepulchre. And thus all churches are open, without hindrance of the heathen . . . [the Syon pilgrim] goes in the Holy Land where he will, without care, and remains as long as he likes in the Holy Sepulchre, in Bethlehem, in Nazareth and wherever he wishes in the Holy Land.37

The European visitor to a local monumental recreation of Jerusalem could recall a now lost era of Latin Christian sovereignty over the holy places, and in much greater cultural and religious completeness than had ever actually existed. Recreations of Jerusalem in Europe were selective translations. They can be partly understood as sites of exclusionary political fantasy that established a devotional monopoly over the holy city.

Recreated Jerusalems and Concepts of Empire

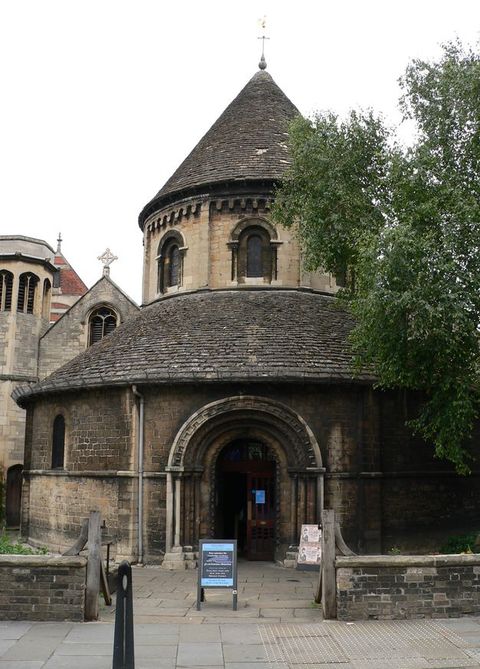

When returning crusader and newly established Norman landowner Simon de Senlis built the Holy Sepulchre Church at Northampton (fig. 2) at the caput of his new estates in the early twelfth century, with its circular nave modelled on the Anastasis Rotunda, he did more than proclaim his piety and commemorate his recent defence of the Holy Land. He was also publicly following in the footsteps of the Emperor Constantine: the exemplary Christian ruler, generous Christian patron, and original builder of the Holy Sepulchre complex. Simon would have been well aware of the precedent: mosaic depictions of Constantine and Helena decorated the eleventh-century Anastasis, facing each other on the north and south sides of the rotunda amidst the twelve apostles and twelve prophets respectively.38 Simon de Senlis’s Holy Sepulchre offers a small-scale, even provincial, example of the co-option of Jerusalem and its holy places into medieval notions of the translatio imperii, or the successive transfer of imperial power from East to West.39 As a means of communicating Simon’s power and Christian virtue to the locality, the Northampton Holy Sepulchre formed a powerful vehicle of local political propaganda.

38

By the twelfth century, the use of Jerusalem to support claims to political authority was an established European and Byzantine tradition. One of the ways in which Charlemagne asserted the status of the Carolingians as the new Israelites, the spiritual nature of Carolingian imperium, and his own religious authority as emperor, was by presenting himself as a renovatio of the Emperor Constantine.40 Michael McCormick has explored Charlemagne’s benefactions to holy sites in Jerusalem, as well as the comprehensive survey made by two Carolingian envoys between 808 and 810 of the people, buildings, and finances of Christian churches in the Holy Land.41

40Imperial or universal rulers by definition enjoyed sovereignty over Jerusalem and the power to relocate its holy places elsewhere through the transfer of relics. In Constantinople, the Church of the Virgin of the Pharos within the imperial palace served from 864 until 1204 as a storehouse for the most precious imperial Passion relics.42 Alexei Lidov suggests that many of the relics found in the Pharos chapel were originally housed in the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem and relocated to Constantinople in the late ninth century, a time of renewed Byzantine sensitivities regarding the translatio imperii.43 Accounts of Charlemagne’s imperial coronation in 800 narrated “global” recognition of his authority over the holy places in Jerusalem, supposedly acknowledged by both the Byzantine emperor and the Abbasid caliph Harun al-Rashid.44 Scholars have explored the connections between Charlemagne’s palace chapel at Aachen and Jerusalem in detail, with potential spolia from the Holy Sepulchre even reused in the chapel’s furnishings and decoration.45 Later medieval perceptions of Charlemagne as liberator of the Holy Land and generous donor of Passion relics made him an exemplary model for the crusading kingship of Louis IX of France.46 Louis’s construction of the Sainte-Chapelle in Paris to house the Passion relics acquired from Emperor Baldwin II in Constantinople formed another notable instance of translatio imperii.

42Death and Burial in Recreated Jerusalems

The “death in Jerusalem” topos provides a further key to interpreting buildings that recreated the holy places, as it both challenges and reaffirms the interchangeability of Jerusalems in Europe with the original across the Mediterranean Sea. Henry IV and Robert Guiscard assume they will die in Palestine, with Henry even preparing galleys of war to sail there. Presented as privileging the Jerusalem of the Holy Land over its multiple but evidently forgotten presences in Europe, the trope implies that not all Europeans could accept that a local copy of the Holy Sepulchre carried the same spiritual charge as the exact location of Christ’s Passion and Resurrection. The prestige and glamour attached to the First Crusaders, as chivalric Christian heroes, would naturally make a ruler wishing to prove his divine right and military worth contemplate a glorious crusading death in Palestine.47

47Yet the topos characterizes this distinction between original and copy as a mistake motivated by vain worldly ambition. Demons and soothsayers speak in “dowbill-undirstanding”: all Jerusalems are the same to these tricksters.48 Henry IV’s realization that he will die in the Jerusalem Chamber at Westminster is a moment of moral revelation. Led by his pride into misinterpreting the prophecy as a promise of martial glory, emphasis returns to the king’s personal failings. The story implies that, as both a physical place and a universal spiritual destination, permanently accessible to all Christians, Jerusalem really is—and always was—nearby. So too is death: expected “in Jerusalem”, but in fact an ever-present possibility to be constantly prepared for. Although the topos appears to tacitly accept the veracity of horoscopes, prophetic signs, and demonic foreknowledge, all that these soothsayers and astrologers ever truly “promised” to Henry IV and his literary peers was that death would one day arrive. As Henry IV belatedly recognizes, the virtuous Christian should celebrate his continuous spiritual proximity to Jerusalem, and be aware that death can come at any moment. He must humbly accept that entry into the holy city may never involve physical arrival in the East. It may instead come only with entry into the heavenly Jerusalem of Revelation 21 at the end of time. Death in the Jerusalem Chamber at Westminster offers Henry a flimsy, this-worldly foretaste of what is to come at the Last Judgement. And yet by doing so, the tale returns us to the hierarchical division between true and false Jerusalems; between the primary spiritual place and the secondary European replica, which the legend initially seems to undercut.

48In practice, European Jerusalem sites regularly incorporated relics from the Holy Land, creating a substitutional relationship between the original site and its European satellites. Santa Croce in Gerusalemme, supposedly the site of Pope Sylvester II’s death, contained several relics believed to have been brought to Rome by the Empress Helena, for example, including earth from Golgotha soaked in Christ’s blood.49 The polysemous quality of relic-stocked Jerusalem recreations also made them particularly attractive as burial places. The practice was widespread on the continent from an early date. At Konstanz Cathedral, Bishop Conrad built a model of the Holy Sepulchre, the Mauritius Rotunda, in the east end of the cathedral cemetery in the tenth century.50 A veteran traveller to Jerusalem, the bishop was buried in the western outer wall of his model, probably alongside the white stones thought to be relics of Christ’s tomb discovered later in the Rotunda, itself reconstructed in the thirteenth century.51 The Domburg built at Paderborn by Bishop Meinwerk about 1009–36 included an imitation of the Anastasis Rotunda and tomb aedicule to the east, planned according to measurements taken in Jerusalem in 1033 by Abbot Wino of Helmarshausen.52 Completion of the chapel was rushed in order to dedicate it before the bishop’s death. Jerusalem replicas and their relics were understood as crucial aids to the salvation of those buried nearby. As the Resurrection and Last Judgement were due to begin on the Mount of Olives, dying “in Jerusalem” helped ensure one’s rapid passage to the heavenly city.53

49Yet there is limited evidence for such sites in England acting as burial places, particularly for their known founders. Early Templar churches seem to have held to a strict prohibition on internal burials (both for members of the Order and for the laity) until the late twelfth century.54 There were burials in the new Temple Church in London (fig. 3), beginning with the possible reburial of its founder-figure, Geoffrey de Mandeville (d.1144) in its elaborate porch. This was followed by the famous series of eight thirteenth-century military effigies now in the nave, one of which commemorates the renowned knight and crusader, William Marshal, Earl of Pembroke (d.1219), but these are exceptional.55 After departing for Jerusalem a second time, Simon de Senlis died in France and was buried at his ancestral foundation of La Charité-sur-Loire. His son was buried at the new family foundation of St Andrew’s Priory, Northampton.56 Neither monastery sought to recreate the holy places.

54The “death in Jerusalem” topos thus exploited the existence of a multifaceted European tradition of reinvented holy places, in order to emphasize the importance of constant preparation for the hereafter. Death can strike at any time, and the good Christian should be constantly ready to meet it. Reinforcing the strong association between death and Jerusalem first established by Revelation 20–21 and expressed most clearly in relation to the imagined deaths of monarchs, the widespread medieval desire for burial within or nearby Jerusalem, via relics and/or replicas of the Holy Land, would have given the topos further contemporary meaning and power. Yet while the legends surrounding Henry IV’s death link the Jerusalem Chamber firmly with an enduring tradition of monumental reproduction, how far the room actually conforms to this type can be questioned. Despite the political possibilities of these sites, amplified in a location as resonant for Plantagenet power as Westminster, presumed connections with recreations of Jerusalem such as Northampton may in fact obscure the original intended significances of the room and its decorations.

The Jerusalem Chamber at Westminster

The conventual buildings at Westminster were located on the south side of the church, connected to the south aisle of the nave by two doors on the east and west sides of the cloister.57 As was standard for Benedictine monasteries, the abbot’s lodgings were located further to the west of the cloister.58 The abbot stood at the head of a large and mainly lay household, institutionally separate from the convent and their domestic staff.59 His house was not an enclosed monastic space, but a secular arena furnished with every necessity for aristocratic domestic life and the hosting of lay visitors. The Monk of Westminster’s Chronicle records the celebration of the feast of the Translation of St Edward the Confessor at the abbey by Richard II on 13 October 1392. At the conclusion of High Mass, celebrated in the presence of the king, “he [Richard II] passed into the abbot’s hall, where, with utmost magnificence, the lords and ladies then at court, as well as the whole convent, or the greater part of it, were brilliantly and elegantly entertained.”60 After collapsing from illness at the shrine of the Confessor, it would have been insulting for Henry IV to be taken anywhere else than the abbot’s lodgings.61

57

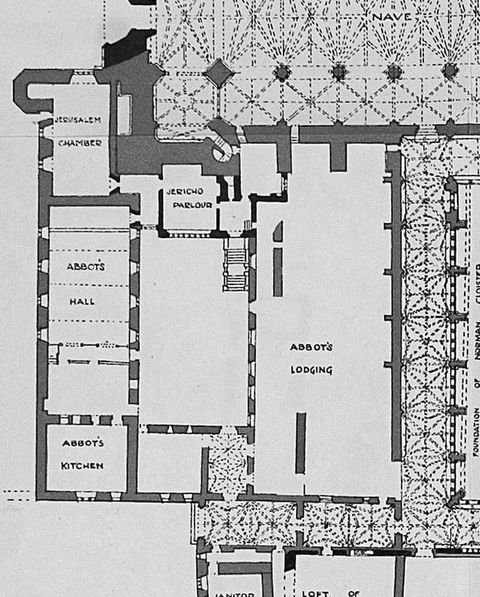

Comprehensively rebuilt by Abbot Nicholas Litlyngton from 1362, the abbot’s house centred on a courtyard with what is now the Deanery located to its east, a room belonging to the Cellarer’s buildings on its south side and on the west, the abbot’s hall.62 The Jerusalem Chamber was a large room located to the north, opening on one side into the hall and on the other into the abbot’s yard or garden (fig. 4).63 With the dais of the hall located at its north end and the kitchens hidden behind a screen at the south end of the hall, the Jerusalem Chamber formed a useful private apartment for the abbot and his favoured guests from which to proceed to high table, or to withdraw into after meals.64 Due to the convenience of having a chamber adjoining the north of the hall, the Jerusalem Chamber may have been a straightforward replacement of an earlier building, constructed on broadly the same site and for the same purpose.65 Litlyngton’s construction work was well underway by 1371–72, when canvas for the windows of “my lord’s new chamber” was purchased.66 After 1379, payments for “the new work” cease.67 Between 1383 and 1384, foundations were laid for the construction of a gallery allowing the abbot to reach the Jerusalem Chamber without entering the hall: this ran along the southern side of the courtyard, to the east end of the base of the new nave tower.68 To the north of the central courtyard of the abbot’s house, partly swallowing elements of the gallery or “little cloister”, is the Jericho Parlour. This room was built between 1500 and 1532 by Abbot John Islip, the last abbot of Westminster before the Reformation. The Jericho Parlour formed a vestibule or antechamber to the Jerusalem Chamber, making both rooms very much part of the abbot’s domestic quarters.69 The furnishings of both Jerusalem and Jericho as recorded in Dissolution inventories of 1541 confirm their secular and domestic use.70

62Today, the Jerusalem Chamber (fig. 5) consists of a large and much-restored oblong, eleven metres (thirty-six feet) in length by five-and-a-half metres (eighteen feet) in width.71 Adjoining what is now termed College Hall, a polygonal tower protrudes from its north-west corner.72 The room is dominated by a grand chimney piece with an elaborate, seventeenth-century cedar overmantel supported on Doric columns.73 It is lined with modern panelling, and decorated with fragments of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century tapestries.74 The Jericho Parlour, separated from the Jerusalem Chamber by a small, windowed lobby, is lined with early sixteenth-century linenfold panelling, and has a stone fireplace set into its east wall.75

71

By tradition, the Jerusalem Chamber gained its name from its interior decorations, either tapestry hangings or painted frescoes probably depicting a Christological sequence.76 Further visual allusions have been proposed by Anthony Bale: he suggests that the row of crenellations on the exterior of the chamber may allude to the walls of Jerusalem, while its polygonal tower refers to the Holy Sepulchre (fig. 6).77 The early fifteenth-century pseudo-Ingulf describes the chamber as one “which had been from ancient times called ‘Jerusalem’” (camera ab antique Jerusalem nuncupata).78 While suggestive of an existing building on the site, he may still be referring in this context to Litlyngton’s chamber. Combined with Usk’s 1414 reference to a Jerusalem Chamber in the abbot’s house, Ingulf’s notice indicates that Litlyngton’s chamber was known from inception as “Jerusalem”.

76

Yet the Jerusalem and Jericho rooms resist interpretation as monumental reproductions of the holy places. First, there is the problem of exactly what these rooms were replicating, for they are not translating specific cult sites to Westminster. Questions can be raised about exactly which holy place or places a circular-naved building referred to: at the London Temple Church (fig. 3) the polygonal form of the crusader Templum Domini (the Dome of the Rock) may have been as important as the Holy Sepulchre for the military order formally titled the Order of the Temple of Solomon and allotted space in the Templum for their own services.79 The Temple Church may have simultaneously referenced multiple sites in Jerusalem, evoking an equally multiple set of impressions and associations within those who encountered it. Yet reference at the London Temple Church was still being made to distinct and easily separable holy places, whereas the Jerusalem Chamber and Jericho Parlour referred to entire cities with a continuous biblical history. Their generalized reference to the Holy Land sets them apart from the conventions of the “Holy Landscapes” tradition.

79It also hinders determining how far any genuine process of reproduction was in evidence at Westminster. As Richard Krautheimer famously showed, medieval architectural imitation involved following a generalized symbolic pattern rather than exactly reproducing a model.80 The selective transfer of a building’s perceived primary characteristics, reassembled and reshuffled if need be, enabled a building with little formal or structural resemblance to its prototype to be recognized as a reproduction of the charismatic original. The key features of a building could include its proportions, measurements, dedication, plan or orientation, and notable architectural elements.81 Although validating a vague likeness, such flexibility appears to have discouraged subtle or nuanced visual reference to Jerusalem, especially when directed at an audience unlikely to have seen the city at first hand.

80In this context of conscious architectural simplification for pious commemorative ends, how far might crenellated walls and a polygonal corner tower have indicated “Jerusalem”, even if the Jerusalem Chamber had been regularly accessed by a monastic audience attuned to the holy city’s omnipresence, and cognizant of its varied visual iconography? Jerusalem could be represented as a walled city with a circular or square form, the circle alluding to its position as the centre of the world (Ezekiel 5:5; Psalm 73:12) and sometimes divided into four parts. The square-walled city invoked Revelation 21:6. In both cases, the city walls were frequently shown, topped by crenellations and interspersed with gates and towers.82 Matthew Paris’s maps of the Holy Land combine the square walls of the apocalyptic Jerusalem with some of the landmarks included on topographic maps of the contemporary city.83 One can see why the crenellated city walls, a fairly stable element of an otherwise fluid iconography, might have been referenced at Westminster. Yet even to a sympathetic audience, it is unlikely that crenellations would have been understood primarily as symbols of the holy city.

82Crenellations were above all symbols of lordship, the architectural expression of noble rank.84 When featured on churches, they invoked the triumphant ecclesia militans and its combined spiritual and seigneurial authority. The exterior crenellations of the Jerusalem Chamber appear in their current form to date from its 1867–73 restoration, but even if medieval in origin, they were not unusual or visually striking architectural features. Nor would they have provided the Jerusalem Chamber with special status within the monastic precinct: the abbey itself was crenellated since 1245, perhaps in an echo of Reims Cathedral, and between 1367 and 1368, a wall with battlements was built between the abbot’s chamber and the gatehouse-prison of Tothill.85 The Jerusalem Chamber fortifications further harmonize the building with the structures around it, underlining the combined spiritual and seigneurial authority of the abbey to those collected in the open space of the monastic precinct. This interpretation is further supported by the position of the chamber at the west front of the abbey church, where crowds of the London poor gathered for the regular distribution of monastic alms.86 More elite visitors could be ceremonially welcomed to the abbey at its north transept entrance, but this did not put the Tothill Gate on the west side of the abbey out of use.87 The Monk of Westminster records Richard II making a barefoot procession with the convent of Westminster “going out at the Tothill Gate” in October 1392.88 Similarly, in December 1389, “the abbot and convent of Westminster, wearing their frocks, walked in procession to the Tothill gate of the monastery” to meet the Duke of Lancaster and an assembly of civic dignitaries before conducting them into the church.89

84It is therefore unlikely that crenellations would have signified “Jerusalem” with the clarity and simplicity required. The quotidian oblong form of the Jerusalem Chamber resists an iconographic reading, while its five-sided corner tower can be read as another pseudo-military decorative feature, crowded out by the larger forms of the west front. Externally and internally, there appears to have been no carefully choreographed orchestration of space designed to guide the viewer towards recognizing a typological likeness to the holy city. Finally, we can consider the title of the chamber itself. The dedication of a church was one of its most significant characteristics, enacting translatio through the transfer of relics to its high altar. Yet in the Jerusalem Chamber at Westminster, its “dedication” remains a name only, contingent on the decoration of the interior and given no backing by the physical presence of relics or liturgical performance. Visual invocation and deliberate monumental replication remain quite different things, whatever inspiration they provided for Usk’s tale. It should also be emphasized that while the name “Jerusalem” probably referred or related to now-lost decorations, there is no surviving evidence for the medieval appearance of the interior.90

90It is even more unlikely that the later Jericho Parlour belongs to the genre of architectural recreations. Jerusalem was at least frequently represented in maps and manuscripts. It is much more difficult to identify, beyond further tapestry hangings depicting Mark 10:46–52 (the healing of blind Bartimaeus at Jericho), Luke 19:1–10 (the repentance of Zaccheus at Jericho), or Joshua 6:1–27 (the Battle of Jericho), what simple visual or architectural shorthands could have been formulated to unambiguously translate “Jericho” to a medieval audience. Even in the heyday of the crusader kingdoms, Jericho was described variously as a small but fertile Saracen village surrounded by trees and fruits,91 or as a place ruined by warfare with “all traces of the holy places in it . . . completely destroyed”.92 While we do not see in the Jerusalem Chamber or Jericho Parlour a deliberate monumental translation of the holy places of Palestine, such nomenclature is neither a unique way of referring to events and places in the Holy Land, nor an unusual means of treating domestic space. The 1541 inventories refer to other chambers in the abbot’s house named after their occupants (Mr Morres Chamber, Syr Radulphis Chamber, Tytleys Chamber), including a “Gabriels chamber” containing a bedstead, two “course cubberdis and ij little forms”.93 If denoting a personal name or surname, the chamber may refer to a frequent occupant, or its name may be based on the Annunciation. Lady Anne Clifford’s diaries refer in April 1617 to “lying in Judith’s Chamber” at her house in Knole.94 Westminster Palace contained a “Marcolf’s chamber”, probably named after King Solomon’s irreverent rustic joker.95 It hosted the 1389 royal council at which Richard II dramatically declared his majority.96

91The “Antioch” chambers painted at Westminster Palace, Clarendon Palace, and Winchester Castle, with a further cycle planned for the Tower of London, have been well known to art historians since Tancred Borenius published on them in 1943.97 In 1250, the master of the Templars in England, Roger de Sandford, was ordered to pass his French book containing “gesta Antiochie et regum etc. aliorum” for use in the painting of the queen’s low room at Westminster, a room later referred to as the Antioch Chamber.98 In 1251, the king ordered the depiction of “historium Antioch” in the room of the king’s chaplains in the Tower of London, although this commission was later cancelled.99 In June 1251, the king ordered that Rosamund’s Chamber in Winchester Castle, named after the mistress of Henry II, be painted with the “story [historium] of Antioch”.100 In July 1251, Henry commanded the sheriff of Wiltshire to have the king’s chamber under the chapel at Clarendon Palace painted with “the story [historium] of Antioch and the duel of king Richard”.101 Tancred Borenius suggested the painting of historia, at least at Clarendon, would mean exactly that: a history of the Third Crusade, evidently including depiction of Nur-al-Din’s attack on Antioch, and the resulting massacre of Christians and the capture of Bohemond III.102 Paul Binski suggests Henry’s image cycles may also have drawn from the mid-twelfth-century epic Chanson d’Antioche, a history of the First Crusade.103

97Laura J. Whatley places these rooms “in the tradition of mental pilgrimage or devotional crusading”, arguing that Henry’s monumental painted cycles “had the potential to foster imagined travel—virtual crusades—to the Holy Land”.104 This is certainly possible, but I would urge caution as to how far an internal and perhaps luxuriously furnished and staffed domestic space encouraged the viewer to transport themselves in their imagination, whether in the form of idle crusading fantasies or the sustained religious meditation that virtual pilgrimage required. Arthur Stanley refers to the existence of a Galilee Chamber at Westminster Palace, apparently located in between its Great and Little Halls.105 Such a busy thoroughfare between, in the case of a Great Hall, a space lined with interior shops and hosting the three royal law courts, was unlikely to foster quiet opportunities for imaginative travel to the East.

104Moralizing about Jerusalem

Instead of seeking to place rooms named after Jerusalem or Antioch within the tradition of mental pilgrimage, it may be helpful to consider the pedagogic significance of secular spaces featuring extended biblical narratives and Holy Land settings in their decorative imagery. Under Edward I, the Painted Chamber at Westminster Palace was redecorated with a large frieze of Old Testament narratives depicting scenes from 1 and 2 Maccabees, separated by a cycle derived from 2 Kings.106 The presentation of Judas Maccabees as a heroic warrior and model for rulership contrasted with scenes depicting the deaths of archetypical biblical tyrants such as Sennacherib, Antiochus, or Abimelech. Binski has explored how one of the overriding themes of the Painted Chamber imagery was the just downfall of evil rulers, its walls depicting a litany of royal misdeeds followed by divine punishment.107 He connects this with an enduring theme of English political writing, “a pattern of politically reflective thought about kingship in the Bible”, later translated into polemical commentary and part of a “longstanding practice of moral engagement through narrative”.108 The Painted Chamber was very much a public space: from 1259, parliaments opened in the Painted Chamber, having first been proclaimed in the Great Hall at Westminster, and the Commons regularly assembled here.109 In addition, the chamber was a regular venue for royal almsgiving.110 Its explicitly “proclamatory and hortatory” biblical imagery addressed a public far wider than the royal or court circle.111 Two Irish friars visiting the chamber in 1322 referred to it as “illa vulgata camera”, that well-known room.112

106The narratives of the Painted Chamber can be closely analysed to reveal their emphasis on the fall of tyrants, while more precise details of the decoration of the Jerusalem Chamber and Jericho Parlour are lost to us. However, I wish to stress here the moral and pedagogic intentio that informed such image-making at Westminster, and not only in the secular arena of Westminster Palace. Around 1400, broadly the same period of Litlyngton’s construction of the Jerusalem Chamber, a ninety-six-scene Apocalypse cycle was painted in the arcades of Westminster Abbey’s octagonal chapter house. Positioned below windowsill level, it was at least in part financed by a monk of the house, John of Northampton.113 On the eastern bay wall, behind the prior or president’s seat where errant monks would kneel to publicly acknowledge faults and receive correction, is an image of a semi-naked Christ as the Son of Man, presented as the eternal and merciful Judge.114 At Christ’s left in the adjoining bay is a seraph or cherub, its wings marked with inscriptions taken from a twelfth-century treatise on penance attributed to Alan of Lille, “On the Six Wings of the Cherub”, a commentary on Isaiah 6.115 The image forms a didactic chart on the subject of the confessional, drawing the painted cycle into the monastic disciplinary and pedagogic processes carried out in the chapter house.116 Westminster Abbey’s chapter house was also regularly used for royal councils and parliaments, during which the king would address his subjects from the president’s seat.117 As parliament was the highest court in the land, the monastic imagery remained fitting whenever the chapterhouse was used as a place of secular deliberation and judgement.

113I suggest that the overtly didactic and moralizing tone of the painted image cycles found in Westminster Palace and Abbey is an interpretation that can be extended to the organization and conceptualization of space within the abbot’s house. I noted above that Litlyngton’s initial construction of the Jerusalem Chamber in the later fourteenth century was followed by Islip’s sixteenth-century building of the Jericho Parlour. This eventually allowed one to move within the space of the abbot’s lodgings from “Jerusalem” to neighbouring “Jericho” (and of course vice versa). Moving from Jerusalem to Jericho retraces the road taken by the man attacked by robbers in Luke 10:30, the parable of the Good Samaritan. Jacqueline Jung highlights a thirteenth-century sermon by the Cistercian monk Caesarius of Heisterbach, preached immediately after the murder of the notably worldly archbishop of Cologne, Engelbert, in 1225.118 Taking Luke 10:30 as his text, Caesarius lamented the archbishop’s journey in life from Jerusalem to Jericho, stating that: “Through Jerusalem, in which the temple was and therefore true religion, are indicated things spiritual; through Jericho, things worldly and secular.”119

118This opens up a new perspective on the significance of these rooms. To move between Jerusalem and Jericho was to move between two states of Christian mind and action: particularly apt for an abbot’s house located within a monastic precinct, but explicitly designed for secular purposes. What today we would consider a liminal complex of buildings could have been understood on an allegorical level as a space moving between Jerusalem and Jericho. A tradition surrounding the nickname of the priory of St Laurence at Blackmore in Essex suggests the contemporary currency of this idea when Abbot Islip built the Jericho Parlour. Henry VIII’s mistress Elizabeth Blount was sent to Blackmore, a quiet Augustinian house close to London, for her confinement before the 1519 birth of Henry Fitzroy. In the words of a 1770 account of the “manor-house of Blackmore, otherwise called Jericho . . . Tradition says, this was one of the houses of pleasure to which King Henry the Eighth used to retire: so that when this lasivious [sic] prince chose to retreat from public business, and indulge himself in the embraces of his courtezans, the cant phrase among the courtiers was, He was gone to Jericho.”120 While the gossip amongst Henry VIII’s courtiers may be historically irrecoverable, the nickname of Blackmore Priory seems to have stuck. A 1529 lease of the manor, lordship, and rectory of Blackmore refers to a tenement “called Jericho”.121 The house built on the remains of the priory site by John Smyth, granted the estate in 1540, is referred to as Jericho Priory or Jericho Priory House.122 A house of about 1600 on Church Street, originally intended as a vicarage adjoining the converted priory church of St Laurence, is known as “Little Jericho” or “Jericho Cottage”.123

120Sandy Heslop highlights the typological resonance of the two locations once paired in this way at Westminster, with Joshua’s victory at Jericho prefiguring the triumph of the First Crusaders in Jerusalem in 1099. As both cities fell to the armies of God’s people, biblical history established a sequential logic in moving from one space to the other at Westminster.124 Such typology may well have found a receptive pre-modern audience: the epitaph on the tomb of Baldwin I of Jerusalem in the Holy Sepulchre compared him to Joshua, and reference is made to Joshua’s deeds in the final sections of Fulcher of Chartres’s account of the 1099 capture of the holy city.125 Fulcher also records the custom of pilgrims returning to Europe cutting or collecting palm branches from Jericho (classed as the “city of palm trees” in Deuteronomy 34:3 and Judges 1:16), before beginning their journey home.126 In the abbot’s house at Westminster, one could also depart “from Jerusalem” via Jericho, perhaps in a post-prandial parody of the pilgrim’s journey.

124While such a specific reading of space could only be made in the sixteenth century, when Islip built the Jericho Parlour, the transition between Jerusalem and Jericho at Westminster may have been a more enduring monastic concern. John Flete’s fifteenth-century history records how Lucius, the first Christian king of Britain and founder of the abbey, was crowned, buried, and stored his regalia at Westminster, before its conversion into a temple of Apollo.127 Assumed since ancient times to have been a location for royal ceremonial, the abbey’s position in the grounds of a royal palace also led to its frequent use as a place for government business. Since the twelfth century, the abbey chapter house, refectory, infirmary chapel, and St Catherine’s chapel were routine locations for meetings of the royal council and later for parliament.128 By 1300, the lower storey of the abbey’s chapter house had been appropriated as a royal treasury, royal archive, and regalia store.129 All such uses of Westminster’s buildings would have been highly disruptive to the monastic life, with secular visitors and royal clerks passing daily through the cloister, and taking short cuts through monastic buildings such as the infirmary.130 Concern about the monastery’s metaphorical position on the road between Jerusalem and Jericho might have been a permanent background worry for its monastic residents, consistently inviting allegorical and typological musings on the theme. And when the Jerusalem Chamber stood alone, we can also appreciate the paradox and joke involved in arriving “at Jerusalem” at Westminster when entering the secular space of the abbot’s lodgings, perhaps after enjoying a great feast in the hall. The abbey church, after all, housed an extensive collection of relics from Jerusalem and the Holy Land, objects that would provide more enduring spiritual “nourishment” for any visitor.131

127Ultimately, entry to the Jerusalem Chamber would have forced medieval visitors to recognize the Jerusalems they had not reached: demonstrably, they had not entered the Jerusalem of Palestine or the heavenly Jerusalem of Revelation 21. The room poses an admonitory question to its inhabitants, and encourages a moral stocktaking of one’s life and conscience. The later construction of Jericho extended such moral and conceptual problems, or perhaps made longstanding monastic concerns more spatially explicit. If not in these Jerusalems, then where are you? Where do you currently stand on the road between Jerusalem and Jericho, between sacred and secular things? Death is an unspoken spectre at this intellectual feast of moral reasoning. Jerusalem is both presence and absence in the chamber: a destination physically arrived at, and a city still spiritually and morally far away, as images of the life of Christ might well underline. As in the downfall of rulers depicted in the Painted Chamber, the “death in Jerusalem” topos articulates a universal lesson and challenge in relation to a specific mighty individual. We may all become Henry IV. Or we may recognize, before it is too late, how close and yet how far we are from Jerusalem.

Acknowledgements

The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013)/ERC grant agreement no. 249466. My thanks to Professor Paul Binski, Dr Hanna Vorholt and the editors for their comments and feedback on this paper. My thanks to Dr Elizabeth Biggs for taking photographs of the Jerusalem Chamber on my behalf, and to Dr Hanna Vorholt for kind permission to use her photograph of the Cambridge Round Church.

About the author

-

Laura Slater completed her AHRC-funded PhD in History of Art at King’s College, University of Cambridge. She is currently an ERC-funded Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the University of Oxford. In 2015-2016, she held a Postdoctoral Fellowship from The Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, London, to complete her monograph, Art and Political Thought in Medieval England. She has held postdoctoral teaching or research positions at the University of Cambridge, University College London, Trinity College Dublin and the University of York. A volume of essays co-edited with Dr Joanna Bellis, Representing War and Violence 1250-1600, was published in 2016 by Boydell & Brewer.

Footnotes

-

1

The Works of Shakespeare: The Second Part of the History of Henry IV, ed. John Dover Wilson (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1968), 4.5, 95:

“King. Doth any name particular belong

Unto the lodging where I first did swoon?

Warwick. 'Tis called Jerusalem, my noble lord.

King. Laud be to God! even there my life must end.

It hath been prophesied to me many years,

I should not die but in Jerusalem;

Which vanity I supposed the Holy Land:

But bear me to that chamber, there I’ll lie,

In that Jerusalem shall Henry die.” ↩︎ -

2

The Chronicle of Adam Usk, 1377–1421, ed. and trans. Chris Given-Wilson (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1997), 242–43. For the dating of the chronicle and its composition, see xlvii–lvii and lxviii. ↩︎

-

3

Antonia Gransden, Historical Writing in England, Vol. 2: c.1307 to the Early Sixteenth Century (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1982), 222–23, 245, 276. Henry’s death at Westminster was noted by chroniclers such as Thomas Walsingham, but the Jerusalem Chamber legend is not included in the Chronica Majora, Historia Anglicana, or Ypodigma Neustriae. A fifteenth-century continuation of the Polychronicon printed in Charles Lethbridge Kingsford, English Historical Literature in the Fifteenth Century (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1913), 284, notes only his death at Westminster, as does a fifteenth-century Latin Brut, 315, and John Hardyng’s c.1440 chronicle: John Hardyng and Richard Grafton, The chronicle of Ihon Hardyng: from the firste begynnyng of Englande, vnto the reigne of kyng Edward the fourth wher he made an end of his chronicle. And from that tyme is added a continuacion of the storie in prose to this our tyme, now first imprinted, gathered out of diuerse and sondery autours y thaue write of the affaires of Englande (London, 1543), fol. cc.vii. The story was repeated in Fabyan’s Chronicle, which ends in 1485: Robert Fabyan, The new chronicles of England and France . . . named by himself the Concordance of histories, repr. from Pynson’s ed. of 1516 . . ., ed. Henry Ellis (London: Longman, 1811), 756–57: “whyle he was makynge his prayers at Seynt Edwardes shrine [. . .] he became so syke [. . .] they, fore his comforte, bare hym into the abbottes place, & lodged hym in a chamber [. . .] named Iherusalem. Than sayd the kynge, ‘louynge be to the Fader of heuen, for nowe I knowe I shall dye in this chambre, according to y prophecye of me beforesayd, that I shulde dye i[n] Ierusalem.’” ↩︎

-

4

The late fourteenth- or early fifteenth-century pseudo-Ingulph’s account of Henry’s death casts him as “putting faith in a deceitful prophecy, [he was] determined to set out for the holy city of Jerusalem. But . . . he died at Westminster in a certain chamber which had been from ancient times called ‘Jerusalem’, thus fulfilling the above idle prophecy.” Henry T. Riley, trans. Ingulph’s Chronicle of the Abbey of Croyland (London: George Bell & Sons, 1908), 364. ↩︎

-

5

Friedrich W. D. Brie, ed., The Brut or The Chronicle of England, Early English Text Society Vol. 2 (London: K. Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co, 1908), 372. For the construction of ships: “he lete make galaieȝ of warre, for he hadde hopid to haue past þe grete se, and so forth to Ierusalem, and þere to haue endid his lyf.” ↩︎

-

6

Anthony Bale, Feeling Persecuted: Christians, Jews and Images of Violence in the Middle Ages (London: Reaktion Books, 2010), 120. Bale discusses the Jerusalem Chamber (118–120) but suggests the legend of Henry IV’s death originated with the French chronicler Enguerrand de Monstrelet (d.1453), 119. ↩︎

-

7

Bale, Feeling Persecuted, 120; Arthur Penrhyn Stanley, Historical Memorials of Westminster Abbey (London: John Murray, 1868), 404. ↩︎

-

8

Elizabeth A. S. Dawes, trans., The Alexiad of the Princess Anna Comnena: Being the History of the Reign of her Father, Alexius I, Emperor of the Romans, 1081–1118 A.D. (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1967), 147, Book VI. ↩︎

-

9

Bale, Feeling Persecuted, 120; John Barbour, Selections from Barbour’s Bruce . . . edited by Prof Skeat for the Early English Text Society (Bungay: R. Clay & Sons, 1900), 83–87, ll. 203–15 and 308–9, Book IV. ↩︎

-

10

Chronicle of Adam Usk, ed. Given-Wilson, xlvii. Between 1406 and 1411, Usk was in exile on the continent and in contact with Henry IV’s enemies. Although pardoned, on his return to Britain he never regained the positions he enjoyed c.1395–1402 as a trusted administrative servant of the crown (xxvii–xxxiv). ↩︎

-

11

Gervase Rosser, Medieval Westminster, 1200–1540 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1989), 67. ↩︎

-

12

Hardyng and Grafton, Chronicle of Ihon Hardyng, fol. cc.vii. ↩︎

-

13

Jacques Le Goff, Saint Louis, trans. G. E. Gollard (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2009), 226. ↩︎

-

14

London, British Library MS Harley 2253, fol. 73r, printed in Thomas Wright’s Political Songs of England: From the Reign of John to that of Edward II, ed. Peter Coss, rev. ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 247: “Ich biquethe myn herte aryht,/ That hit be write at mi devys,/ Over the see that hue be diht,/ With fourscore knyhtes al of prys/ In were that buen war ant wys/ Ageyn the hethene for te fyhte,/ To wynne the croiz that lowe lys; Myself ycholde gef that y myhte”; Michael Prestwich, Edward I (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1997), 557. ↩︎

-

15

Bale, Feeling Persecuted, 120. ↩︎

-

16

Henry Richards Luard, ed., Lives of Edward the Confessor, Rolls Series Vol. 3 (London: Longman, 1858), 123, 277; Matthew Paris, The History of Saint Edward the King, trans. Thelma S. Fenster and Jocelyn Wogan-Browne (Tempe, AZ: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 2008), 98–100; Paul Binski, Westminster Abbey and the Plantagenets: Kingship and the Representation of Power, 1200–1400 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1995), 54–55. Medieval pilgrims used the terms Syria and Palestine routinely in travel accounts, probably derived from Pliny the Elder, see his Natural History, Volume II: Books 3–7, trans. Harris Rackham, Loeb Classical Library 352 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1942), 270–3, 280–1, Book 5. For example, see Burchard of Mount Sion: “After Fourth Syria, that is to say Phoenician Syria, there follows Palestine, which is properly called the land of the Philistines, because there are three Palestines, as will be seen, but they are all part of Greater Syria. First Palestine, whose capital is Jerusalem, extends with all its mountains as far as the Dead Sea, the desert and Kadesh-barnea. The Second, whose capital is Caesarea of Palestine, or Caesarea Maritima, with the whole land of the Philistines, begins at the above-mentioned Petra incisa or Pilgrims’ Castle and extends as far east as Bashen (Basan). The Third, whose capital is Beth-shean (Bethsan) is sited below Mount Gilboa beside the Jordan. This was formerly called Scythopolis. That Palestine is properly called Galilee or the great plain of Esdraelon” in Denys Pringle, Pilgrimage to Jerusalem and the Holy Land, 1187–1291 (Ashgate: Farnham, 2012), 244; see also 109, 133, 261, 277, 307, 319, 326, 349, 351; for pilgrimage accounts using the term, in John Wilkinson, Joyce Hill, and W. F. Ryan, Jerusalem Pilgrimage, 1099–1185 (Hakluyt Society: London, 1988), 14, 112, 165, 177, 190, 267, 307, 309, 313–15, 319. Syria (Sulie) was a standard vernacular term for the Holy Land, with Palestine understood as a province within it, again following Roman usage: Matthew Paris, The Life of Saint Alban, trans. Thelma S. Fenster and Jocelyn Wogan-Browne (Tempe, AZ: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 2010), 13, n.44. ↩︎

-

17

Aelred of Rievaulx, Aelred of Rievaulx: The Historical Works, ed. Marsha L. Dutton, trans. Jane Patricia Freeland (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 2005), 198–200; Matthew Paris, La Estoire de Seint Aedward le Rei, ed. Kathryn Young Wallace (London: Anglo-Norman Text Society, 1983), 101; Paris, History of Saint Edward, 100. ↩︎

-

18

Mary Carruthers, The Craft of Thought: Meditation, Rhetoric, and the Making of Images, 400–1200 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 42–44; Alexander Nagel and Christopher S. Wood, Anachronic Renaissance (New York: Zone Books, 2010), 51–61. ↩︎

-

19

For the political as well as emotional logic of “memory work”, see Neil Gregor, Haunted City: Nuremberg and the Nazi Past (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2008), 9–10. ↩︎

-

20

Bianca Kühnel, From the Earthly to the Heavenly Jerusalem: Representations of the Holy City in Christian Art of the First Millennium (Freiburg: Herder, 1987), 74–78; Sylvia Schein, Gateway to the Heavenly City: Crusader Jerusalem and the Catholic West (1099–1187) (Aldershot: Ashgate 2005), 2–5, 109–41. ↩︎

-

21

For a particularly ambitious site, replicating the Holy Sepulchre, the Mount of Olives, the Church of the Ascension, the Valley of Josephat, the Pool of Siloam and the Field of Aceldama, see Robert G. Ousterhout, “The Church of Santo Stefano: A ‘Jerusalem’ in Bologna”, Gesta 20, no. 2 (1981): 311–21. ↩︎

-

22

Bianca Kühnel, “Virtual Pilgrimages to Real Places: The Holy Landscapes”, in Imagining Jerusalem in the Medieval West, ed. Lucy Donkin and Hanna Vorholt, Proceedings of the British Academy 175 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 243–64; Robert G. Ousterhout, “‘Sweetly Refreshed in Imagination’: Remembering Jerusalem in Words and Images”, Gesta 48, no. 2 (2009): 153–68, especially 162–66; Carruthers, Craft of Thought, 42–44; Nagel and Wood, Anachronic Renaissance, 51–61. For round churches in England, see Barney Sloane and Gordon Malcolm, Excavations at the Priory of the Order of the Hospital of St John Jerusalem, Clerkenwell, London (London: Museum of London Archaeology Service, 2004), 4; Michael Gervers, “Rotundae Anglicanae”, in Evolution générale et développements régionaux en histoire de l’art: Actes du XXIIe Congrès International d’Histoire de l’Art, ed. György Rózsa (Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó, 1972), 359–76. Templar round churches may well have been reproducing the Dome of the Rock, the dimensions of which are identical to the Anastasis Rotunda: see the discussion below. ↩︎

-

23

Bale, Feeling Persecuted, 121. ↩︎

-

24

Crusader prohibitions on the settlement of the city by non-Christians were relaxed as early as c.1120 under Baldwin II: see Joshua Prawer, The Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem: European Colonialism in the Middle Ages (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1972), 40, 238–45; Prawer, The History of the Jews in the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988). ↩︎

-

25

Wilkinson, Hill, and Ryan, Jerusalem Pilgrimage, 273. ↩︎

-

26

Wilkinson, Hill, and Ryan, Jerusalem Pilgrimage, 282. ↩︎

-

27

Pringle, Pilgrimage, 96. The reference is to Matthew 4:13. See also 102, 114, 130–32 for his interactions with and further descriptions of non-European Christians including the Bedouin, who “lead the kind of life that the routiers are accustomed to follow in France” (132). ↩︎

-

28

Pringle, Pilgrimage, 242. ↩︎

-

29

Prawer, History of the Jews, 185–91. ↩︎

-

30

Prawer, History of the Jews, 206, 211. ↩︎

-

31

Pringle, Pilgrimage,163. ↩︎

-

32

Pringle, Pilgrimage, 92: “In it at the present time a certain infidel Saracen has laid out his place of prayer in honour of Muhammad.” Willbrand of Oldenburg was a keen observer of the demographic variety of Jerusalem, stating that the city “contains many very rich inhabitants: Franks and Latins, Greeks and Syrians, Jews and Jacobites [. . .] And it should be known that this name ‘Franks’ is widely applied in Outremer to all those who observe Roman law. Those are called ‘Syrians’ who are born in Syria and use Saracen [Arabic] for everyday speech and Greek for Latin”: Pringle, Pilgrimage, 62–63. Thietmar also notes that the “Saracens have converted the Temple of the Lord [the Dome of the Rock] [. . .] into their mosque, so that no Christian ever presumes to enter it”: Pringle, Pilgrimage, 112. ↩︎

-

33

Inter-faith encounters also took place in secular contexts. Theodoric confesses how when on a road outside Jerusalem: “we saw a crowd of Saracens, who were all beginning to plough with their oxen and asses a very well-kept field. And they uttered a horrid cry, which is not unusual for them when they start any work, but they filled us with great terror!”: Wilkinson, Hill, and Ryan, Jerusalem Pilgrimage, 310–11. ↩︎

-

34

Christopher Tyerman, England and the Crusades, 1095–1588 (Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press, 1988), 37–39. ↩︎

-

35

John Edwards, “The Church and the Jews in Medieval England”, in The Jews in Medieval Britain: Historical, Literary and Archaeological Perspectives, ed. Patricia Skinner (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2003), 90–91. ↩︎

-

36

Edwards, “Church and the Jews”, 90–91. ↩︎

-

37

Kathryne Beebe, “Reading Mental Pilgrimage in Context: The Imaginary Pilgrims and Real Travels of Felix Fabri’s ‘Die Sionpilger’”, Essays in Medieval Studies 25 (2008): 39–40, 52, quotation on 44. When guiding his readers to Rome, Fabri goes even further in reshaping earthly boundaries. As he conducts his female audience to the tomb of St John Lateran, he remarks: “In the church is also St John’s chapel, into which no woman may enter. However, the pope has given a dispensation for the Syon pilgrims [to enter]” (51). ↩︎

-

38

Gustav Kühnel, “Heracles and the Crusaders: Tracing the Path of a Royal Motif”, in France and the Holy Land: Frankish Culture at the End of the Crusades, ed. Daniel H. Weiss and Lisa J. Mahoney (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004), 64–68; Denys Pringle, The Churches of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: A Corpus, Vol. 3: The City of Jerusalem (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 25. ↩︎

-

39

Janet Nelson, “Kingship and Empire”, in The Cambridge History of Medieval Political Thought, c.350–1450, ed. James Henderson Burns (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988), 249. ↩︎

-

40

Stephen G. Nichols, Romanesque Signs: Early Medieval Narrative and Iconography (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1983), 77–86. ↩︎

-

41

Michael McCormick, ed. and trans., Charlemagne’s Survey of the Holy Land (Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks, 2011), 77–91, 185, 187–91, 193 also interprets a columnar building on Charlemagne’s “portrait” or “temple” silver penny as a schematic representation of the Holy Sepulchre, and notes eighth-century copying of an eschatological treatise prophesying how the last Roman emperor would travel to Jerusalem, regain control of Golgotha, place his crown on the True Cross, and commit his kingdom to God before his death marked the beginning of the Apocalypse. As the end of the world was due to start on the Mount of Olives, Carolingian interest in this text adds a new dimension to Charlemagne’s foundation of a monastery on the Mount of Olives dedicated to the archetypal Roman saints, Peter and Paul. ↩︎

-

42

Alexei Lidov, “A Byzantine Jerusalem: The Imperial Pharos Chapel as the Holy Sepulchre”, in Jerusalem as Narrative Space: Erzählraum Jerusalem, ed. Annette Hoffmann and Gerhard Wolf (Leiden: Brill, 2012), 63, 67. ↩︎

-

43

Lidov, “Byzantine Jerusalem”, 78–79; Donald M. Nicol, “Byzantine Political Thought”, in The Cambridge History of Medieval Political Thought, c.350–1450, ed. James Henderson Burns (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988), 59. ↩︎

-

44

Nichols, Romanesque Signs, 81–82; Rosamond McKitterick, Charlemagne: The Formation of a European Identity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), 51, 116–17, 159, 37; Thomas F. X. Noble, ed. and trans., Charlemagne and Louis the Pious: The Lives by Einhard, Notker, Ermoldus, Thegan, and the Astronomer (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2009), 35. ↩︎

-

45

The marble paving, plinths, and four steps of the stairway to the royal throne at Aachen may have been spolia from Jerusalem, while a round oil lamp representing the walls and towers of Jerusalem hung from the decorated ceiling. See Gustav Kühnel, “Aachen, Byzanz und die frühislamische Architektur im Heiligen Land”, in Studien zur byzantinischen Kunstgeschichte: Festschrift für Horst Hallensleben, ed. Birgitt Borkopp et al. (Amsterdam: Hakkert, 1995), 40, 44, 49; McCormick, ed. and trans., Charlemagne’s Survey, 192, n.28; Sven Schütte, “Der Aachener Thron”, in Krönungen Könige in Aachen-Geschichte und Mythos: Katalog der Ausstellung in zwei Bänden, ed. Mario Kamp (Mainz: P. von Zabern, 2000), 218; Bianca Kühnel, “Jerusalem Between Narrative and Iconic”, in Jerusalem as Narrative Space, ed. Hoffmann and Wolf, 115. ↩︎

-

46

Edina Bozoky, “Saint Louis, Ordonnateur et Acteur des Rituels Autour des Reliques de la Passion”, in La Sainte-Chapelle de Paris: Royaume de France ou Jérusalem céleste? Actes du Colloque (Paris, Collège de France, 2001), ed. Christine Hediger (Turnhout: Brepols, 2007), 19–34; Clark Maines, “The Charlemagne Window at Chartres Cathedral: New Considerations on Text and Image”, Speculum 52, no. 4 (1977): 801–23. Relics donated by Charlemagne formed an essential element of the foundation histories of numerous French monasteries. For the significance of the acquisition and distribution of relics by rulers, see also Julia M. H. Smith, “Rulers and Relics c.750–c.950: Treasure on Earth, Treasure in Heaven”, Past and Present 206, Supplement 5 (2010): 74–77, 84–90; Bernard Flusin, “Les reliques de la Sainte-Chapelle et leur passé impérial à Constantinople”, in Le trésor de la Sainte-Chapelle, ed. Jannic Durand and Marie-Pierre Laffitte (Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 2001), 20–31. ↩︎

-

47

Tyerman, England and the Crusades, 22–24, 27–28. ↩︎

-

48

Barbour, Bruce, l. 236, 84–85. ↩︎

-

49

Nagel and Wood, Anachronic Renaissance, 194. ↩︎

-

50

Xenia Stolzenburg, “Bestattungen ad sanctissimum: Die Heiligen Gräber von Konstanz und Bologna im Zusammenhang mit Bischofsgräbern”, in Bischöfliches Bauen im 11. Jahrhundert, ed. Jörg Jarnut, Ansgar Köb, and Matthias Wemhoff, Mittelalter Studien 18 (Munich: W. Fink, 2009), 92, 96. ↩︎

-

51

Stolzenburg, “Bestattungen ad sanctissimum”, 96–101. ↩︎

-

52

Kühnel, “Jerusalem Between”,115–17. ↩︎

-

53

Bale, Feeling Persecuted, 120. ↩︎

-

54

David Park, “Medieval Burials and Monuments”, in The Temple Church in London: History, Architecture, Art, ed. Robin Griffith-Jones and David Park (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2010), 73. ↩︎

-

55

In addition to David Park’s full enumeration of the medieval burials in the Temple Church, see also Philip J. Lankester, “The Thirteenth-Century Military Effigies in the Temple Church”, in The Temple Church in London, ed. Griffith-Jones and Park, 93–134. ↩︎

-

56

Francisque Xavier Michel, ed. Chroniques Anglo-Normandes: Recueil d’extraits et d’écrits relatifs à l’histoire de Normandie et d’Angleterre pendant les XIe et XIIe siècles / publié, pour la première fois, d’après les manuscrits de Londres, de Cambridge, de Douai, de Bruxelles et de Paris, Vol. 2 (Rouen: Et imprimées par Nicétas Periaux, pour Édouard Frére,1836), 126. ↩︎

-

57

John George Noppen, Westminster Abbey and its Ancient Art (London: Country Life, 1926), 36–37. Although parts of the cloister were finished as early as 1249–50 in Henry III’s rebuilding of the abbey, the whole was not completed until c.1345 by Abbot Simon Byrcheston, and it was rebuilt again by 1365. ↩︎

-

58

Michael B. Thompson, Cloister, Abbot and Precinct in Medieval Monasteries (Stroud: Tempus, 2001), 66–69. What is now the Deanery was significantly rebuilt in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries: see Joseph Armitage Robinson, The Abbot’s House at Westminster (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1911), 10–11, 13–15; Royal Commission on Historical Monuments (England), An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in London, Vol. 1: Westminster (London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1924), 86. Henceforth RCHM. ↩︎

-

59

Thompson, Cloister, 75, 78, 86, 97–99; Julie Kerr, Monastic Hospitality: The Benedictines in England, c.1070–c.1250 (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2007), 60–61, 124, 126. ↩︎

-

60

Leonard Charles Hector and Barbara F. Harvey, ed. and trans., The Westminster Chronicle, 1381–1394 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1982), 510–11: “perrexit in aulamabbatis, ubisplendide in maximoapparatusuos dominos etdominas qui tunc cum eopresentesextiterunt et conventumtotum pro majori parte lauterefecit.” ↩︎

-

61

Ian Mortimer, The Fears of Henry IV: The Life of England’s Self-Made King (London: Jonathan Cape, 2007), 348. ↩︎

-

62

Noppen, Westminster Abbey, 39; Francis Bond, Westminster Abbey (London: H. Frowde, 1909), 300; Stanley, Historical Memorials, 400; RCHM, 86. ↩︎

-

63

Stanley, Historical Memorials, 402. ↩︎

-

64

Noppen, Westminster Abbey, 39; RCHM, 86; Alfred John Kempe, “Some Account of the Jerusalem Chamber in the Abbey of Westminster and of the Painted Glass Remaining Therein”, Archaeologia 26 (1836): 432–40, suggests possible use as an oratory, as a niche in its entrance passage contains a receptacle for holy water, but this seems unlikely: Litlyngton’s building accounts record a “camera” rather than a “capella” and later recorded furnishings of the room certainly suggest a secular use. Thomas Hugo, “The Jerusalem Chamber”, in George Gilbert Scott, Gleanings from Westminster Abbey (Oxford and London: John Henry and James Parker, 1863), 216, suggests it was either “the withdrawing room to the abbot’s hall . . . [or] a Guesten Hall for the constant influx of strangers who enjoyed the abbot’s hospitality”, and considered it to be in the wrong position to be an abbot’s chapel. ↩︎

-

65

RCHM, 76: “There are probable remains of 12th-century work to the W. of the cloister and in the Abbot’s lodging”: see also 86–88; see too Robinson, Abbot’s House, 7,12. ↩︎

-

66

Robinson, Abbot’s House, 11. ↩︎

-

67

Robinson, Abbot’s House, 16. ↩︎

-

68

Robinson, Abbot’s House, 11. ↩︎

-

69

Noppen, Westminster Abbey, 39–40. ↩︎

-

70

Robinson, Abbot’s House, 37–38. ↩︎

-

71

Kempe, “Jerusalem Chamber”, 432; Hugo, “Jerusalem Chamber”, 216. ↩︎

-

72

E. D. Morris, “The Jerusalem Chamber”, Presbyterian and Reformed Review 7 (1896): 595–610, suggests (597) that the tower formerly provided entry to the chamber, although access was closed at the time of writing. There is a 1745 order in Westminster Abbey Muniment 34517, fol. 35 for the battlements at the north end of the Jerusalem Chamber to be renewed, a wall built, and the door under the north window to be filled up with stone. However, I have not come across this suggestion elsewhere and the RCHM ground plan does not indicate any doorway in the tower. ↩︎

-

73

RCHM, 87. ↩︎

-

74

RCHM, 87. ↩︎

-

75

RCHM, 88. ↩︎

-

76

Bale, Feeling Persecuted, 118. ↩︎

-

77

Bale, Feeling Persecuted, 118. ↩︎

-

78

Kempe, “Jerusalem Chamber”, 434; Riley, trans., Ingulph’s Chronicle, 364; David Roffe, “The Historia Croylandensis: A Plea for Reassessment”, English Historical Review 110, no. 435 (1995): 93–108. ↩︎

-

79

Virginia Jansen, “Light and Pure: The Templars’ New Choir”, in The Temple Church in London, ed. Griffith-Jones and Park, 59–60, 65. ↩︎

-

80

Richard Krautheimer, “Introduction to an ‘Iconography of Medieval Architecture’”, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 5 (1942): 1–33; Paul Crossley, “Medieval Architecture and Meaning: The Limits of Iconography”, The Burlington Magazine 130, no. 1019 (1988): 116–21; Nagel and Wood, Anachronic Renaissance, 59–61. ↩︎

-

81

Krautheimer, “Introduction”, 15–16, 19–21. ↩︎

-

82

Martine Meuwese, “Representations of Jerusalem on Medieval Maps and Miniatures”, Early Christian Art 2 (2005): 140–43; Paul D. A. Harvey, Medieval Maps of the Holy Land (London: British Library, 2012). ↩︎

-

83

Daniel K. Connolly, “Imagined Pilgrimage in the Itinerary Maps of Matthew Paris”, The Art Bulletin 81, no. 4 (1999): 600, n.13. ↩︎

-

84

Charles Coulson, “Hierarchism in Conventual Crenellation: An Essay in the Sociology and Metaphysics of Medieval Fortification”, Medieval Archaeology 26 (1982): 72. ↩︎

-

85

Binski, Westminster Abbey, 36; Robinson, Abbot’s House, 11; Rosser, Medieval Westminster, 233–34; Stanley, Historical Memorials, 384–85; Coulson, “Hierarchism”, 89–91. ↩︎

-

86

Barbara F. Harvey, Living and Dying in England, 1100–1540: The Monastic Experience (Oxford: Clarendon Press,1993), 27. ↩︎

-

87

Harvey, Living and Dying, 27. ↩︎

-

88

Hector and Harvey, ed. and trans., Westminster Chronicle, 508–9: “exeundo per protam de Toothull”. ↩︎

-

89

Hector and Harvey, ed. and trans., Westminster Chronicle, 408–9: “Abbas vero et conventus Westmon’ in suis froccis usque ad portam monasterii versus Toothull’ processionaliter exierunt et in ecclesiam”. ↩︎

-

90

Bale, Feeling Persecuted, 118: “The room seems to have been named after now-lost decorations, either wall-hangings or frescoes, depicting scenes of Jerusalem and inscribed with Biblical verses about Jerusalem.” ↩︎

-

91

Saewulf, travelling c.1101–1103, refers to it as: “a country very rich in trees, all kinds of palms, and all fruit-trees”; Daniel the Abbot, travelling c.1106–1108, describes “a Saracen village . . . [containing] the house of Zacchaeus and . . . the stump of that tree on which he climbed to see Jesus”; and Theodoric, c.1169–1174, notes “a small village [. . .] where every fruit is first to ripen. It is a place full of roses”: Wilkinson, Hill, and Ryan, Jerusalem Pilgrimage, 109, 138, 305. ↩︎

-

92

The quotation is from Burchard of Mount Sion, c.1274–1285: “Once famous, it now has scarcely eight houses. There are the remains of a squalid township and all traces of the holy places in it have been completely destroyed.” Other thirteenth-century pilgrims tell a similar story. For Wilbrand of Oldenburg, travelling c.1211–12, Jericho is “a small castle, its walls destroyed, inhabited by Saracens”; Philip of Savona, writing in c.1280–1289, stated it to be “formerly a very large city”; and for Riccoldo of Monte Croce, c.1288–1289, it was “more or less deserted”: Pringle, Pilgrimage, 282, 293, 347, 368. ↩︎

-

93

Robinson, Abbot’s House, 37–39. ↩︎

-

94

David J. H. Clifford, ed., The Diaries of Lady Anne Clifford (Stroud: Sutton, 1990), 53. ↩︎

-

95

Jan M. Ziolkowski, Solomon and Marcolf (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2008). ↩︎

-

96

Hector and Harvey, ed. and trans., Westminster Chronicle, 390–91, n.2. ↩︎

-

97

Tancred Borenius, “The Cycle of Images in the Palaces and Castles of Henry III”, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 6 (1943): 40–50; Laura J. Whatley, “Romance, Crusade, and the Orient in King Henry III of England’s Royal Chambers”, Viator 44 (2013): 175–98. There are other recorded princely chambers named after exotic places: in 1313, the salle d’Inde, or Indian Chamber in Hesdin, principal residence of the counts of Artois, was cleaned in preparation for a visit by Edward II of England. Highlighted in Malcolm Vale, The Princely Court: Medieval Courts and Culture in North-West Europe (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 280. ↩︎

-

98