Resonance and Reuse

Resonance and Reuse: The Fifteenth-Century Transformation of a Late Romanesque Vita Christi

By Kirsten Collins

Abstract

This article explores the fifteenth-century reinvention of Getty Ms. 101, a late Romanesque picture book that was reconfigured as a devotional manual. The fifteenth-century additions included rosary prayers and the only surviving image of Robert of Bury, one of the child saints said to have been murdered by Jews in the twelfth century. The article examines the ways in which changes to the manuscript, including a number of adjustments to the Infancy narrative, not only reflect an evolving and widespread devotional practice, but also how the book was attuned to its local environment.

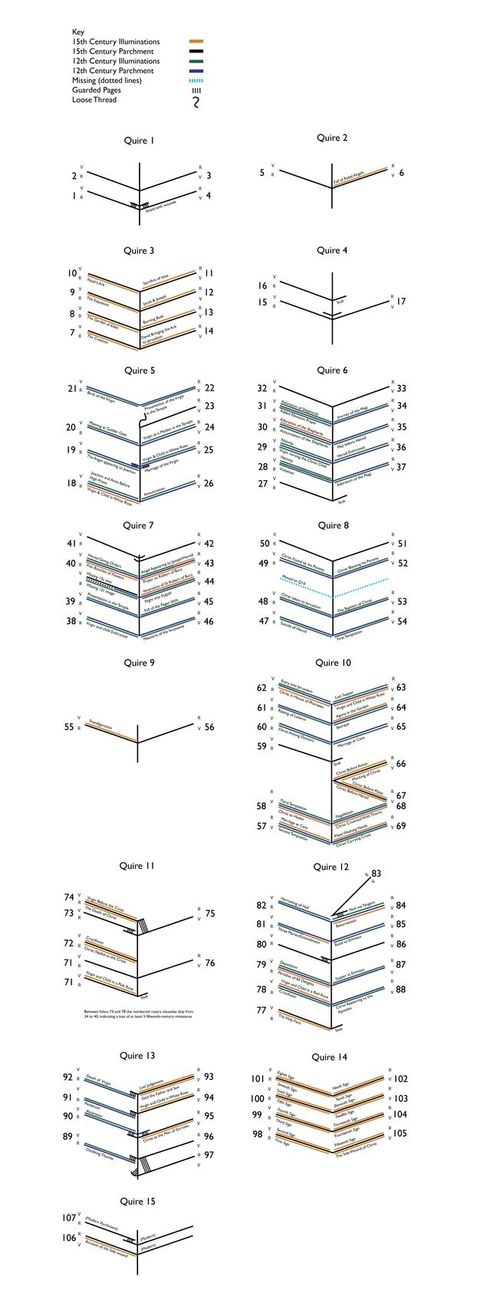

Sometime toward the close of the fifteenth century a late Romanesque picture cycle was reconfigured as a devotional miscellany and rosary manual (fig. 1).1 The fragmentary codex, consisting of seven quires with over fifty illuminations, was interleaved with new images and prayers (fig. 2). Manuscript history is in large part a history of such accretive processes. We would be hard-pressed to find a manuscript that had not been added to, corrected, or improved in some small way. Yet Getty Ms. 101 (also known as the Getty Vita Christi) offers a case study not only in intervention but also in the nature of concentrated, focused response. Unlike other medieval manuscripts that changed gradually, through interventions over the years, this manuscript was decisively transformed around 1480–90.2

1The three-hundred-year gap between the creation of the Romanesque pictures and the late medieval additions invites a series of questions about the fifteenth-century reception of the twelfth-century object. How do the changes to the twelfth-century pictures signal points of emphasis for its early modern reader? What value did the Romanesque pictures hold for the fifteenth-century patron? To what degree did the retention of the older illuminations reflect consideration or memory of a twelfth-century cult? This transformed manuscript offers valuable insights about the role that the past played in artistic invention in late medieval England.

The manuscript includes more than one hundred images and numerous prayers; this article will focus on a series of images depicting the infancy of Christ. Changes and additions to this section of the manuscript offer clues to the resonances that the older programme may have had for its fifteenth-century users.

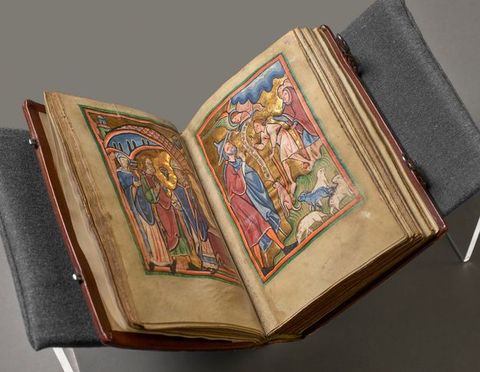

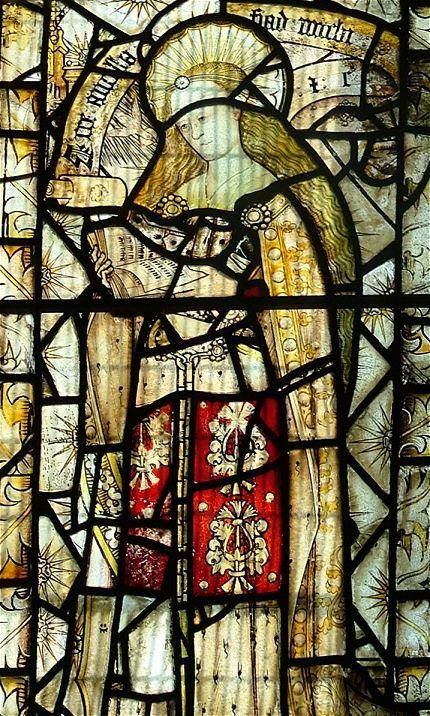

The Twelfth-Century Manuscript and its Fifteenth-Century Transformation

In order to appreciate the changes that shaped the fifteenth-century manuscript it is necessary to understand the volume’s original twelfth-century structure. Painted on one side of the bifolia and arranged in facing pairs, the Romanesque book once contained over fifty miniatures providing an expansive visual chronicle of the life of Christ and the Virgin (fig. 3).3 The Getty Vita Christi’s twelfth-century illuminations may have once served as the prefatory cycle for a psalter or as a devotional picture book. The tradition of prefacing luxury psalters with pure pictorial programmes became a hallmark of English manuscript painting in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Such Christological programmes may have promoted meditation, prayer, or discussion while establishing the link between Old Testament prophecy (present in the text of the Psalms) and its perceived fulfilment in Christ. However, at 17.6 by 12.8 centimetres, the Getty manuscript is considerably smaller than surviving English psalters from this period. Its lack of accompanying text has led to speculation that it might have been a devotional picture book, but there is no definitive evidence for such books until the thirteenth century.4 The picture cycle is unusual both for the scope of its programme and for its iconography. With fifty-one surviving images, it is lengthier than any earlier known examples. The twelfth-century programme particularly emphasized childhood, with scenes of the early life of Mary and Jesus. It began with seven episodes dedicated to the early life of the Virgin, including images of her as both a child and a maiden in the temple, and featured a number of scenes with King Herod, including the rare image of his suicide.5 It is unclear whether the blank backs of the folios had been glued together, as in the twelfth-century Life and Miracles of St Edmund, King and Martyr,6 but in any case they were not conceived of as a space for text, as in a northern English psalter now in Oxford.7 Rather, this cycle was conceived of as a purely pictorial invitation to contemplation or prayer.8

3

In the fifteenth century, the formerly textless picture cycle became a prayer book. Its core served as a manual designed to lead the reader through the fifty meditations on the life of Christ that also featured in one of the emerging forms of the rosary prayer. The manuscript’s Romanesque bifolia were interleaved with new parchment (fig. 2). Prayers and illuminations were added to these pages as well as to the backs of existing illuminations. Although where and by whom these changes were made is unknown, the style of the fifteenth-century illuminations is East Anglian. Throughout the book, gold was scraped away and inscriptions and speech banderoles were added, embedded among the older illuminations and uniting them with the new.9

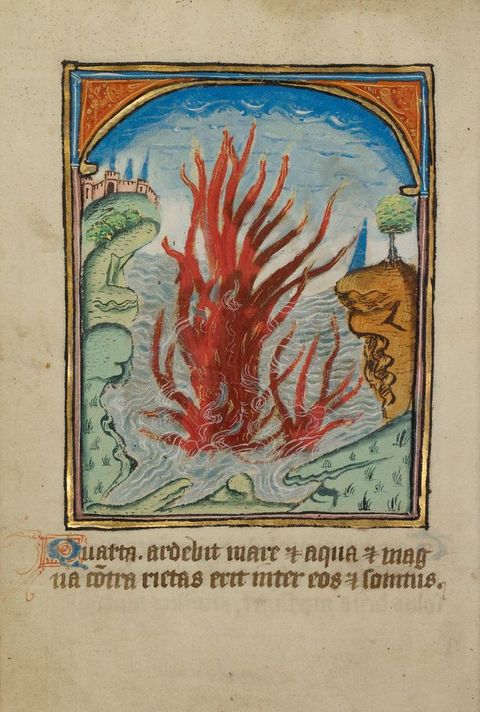

9The transformed book begins with a list of the eight ages of the world and a fifteenth-century illumination of the Fall of Rebel Angels on folio 6 (fig. 4). Additional texts include biblical readings from the Gospel of John, Genesis, Exodus, and Samuel, as well as the penitential psalms, a litany, and various prayers to Mary and Christ. A concluding section contains miniatures with the rare iconography of the Fifteen Signs before the Day of Judgement (see, for example, fig. 5).10 While the choice of prayers is not standard, the additions of Old Testament and apocalyptic material stretch the original programme from its previous Christological focus to an all-encompassing history of salvation.11

10

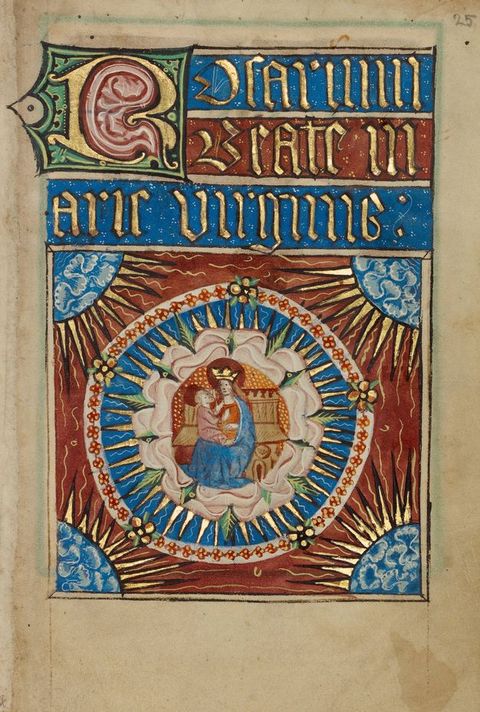

The Rosary Prayers

Throughout the book, the original narrative cycle of vita Christi illuminations was also expanded, with fifteenth-century images being interspersed among the earlier pictures.12 Within the newly elaborated Christological section of the manuscript, rosary prayers served as an organizational spine uniting most of its illuminations. A series of numbered clausulae (abbreviated Ave prayers and references to moments in Christ’s life) were added to the bottom of the illuminations, new and old, to mark the fifty meditations on the life of Christ associated with the rosary (fig. 6).13 A lengthy preface underscored the ultimate reward to be gained through these devotions. It mentions a Carthusian monk near Trier who was rewarded with a vision of the Virgin and angels singing the rosary in heaven, and promises indulgences to those who similarly repeated the rosary.14 The anonymous monk was probably a reference to Dominic of Prussia, a Carthusian who had served at the Abbey of St Alban in Trier. Writing in the early fifteenth century, Dominic had composed a series of fifty meditations on the life of Christ that were intended to be recited with the rosary.15 The rosary in the Getty Vita Christi is structured as fifty clausulae that for the most part correspond with those composed by Dominic sometime between 1409 and 1415. Where the Getty manuscript’s rosary diverges slightly from his text, it corresponds to a similar rosary from the Cologne Charterhouse.16 The preface goes on to promise full forgiveness of sins for contrition and recitation of the rosary, and varying years of indulgences for membership in the Confraternity of the Rosary, as well as instructions for saying the rosary with these images. The preface specifies that before each picture the devotee was meant to recite an Ave and then read the meditation. The clausulae were punctuated at regular intervals with images of the Virgin and Child, set within a rose and accompanied by devotions (fig. 7). Just as strings of beads had long been used to mark one’s progress through groups of Pater Nosters and Aves, each turn of the page guided the reader through this increasingly complex form of the rosary prayer.

12

The addition of luxurious images to the numbered meditations was by no means a standard feature of rosary books at this time. The Getty Vita Christi is unique among other contemporary illustrated rosaries, not only for its highly individualized reuse of an older manuscript, but also for its comprehensive synthesis of text and image. The first printed version of an illustrated rosary appeared in 1483 and consisted of fifteen woodcuts, each depicting five scenes from the life of Christ and the Virgin. While appearing in a book with several other printed rosary prayers, the images themselves were not glossed and were intended to function independently of the printed prayers.17 In the Getty manuscript, each of the narrative images of the life of Christ added in the fifteenth century (with just one exception) corresponds to a rosary prayer, demonstrating the degree to which this particular devotional practice drove the fifteenth-century illustrative campaign.18

17In recycling the Romanesque images, the fifteenth-century patron took these formerly flexible stimuli to prayer, meditation, and contemplation and embedded them in a choreographed devotional practice. And yet, even as the old images were subsumed by the new, scripted content, the patron chose to preserve Romanesque images that were not necessary for the rosary prayer. Lacking numbered prayers, these miniatures are nevertheless interspersed in the appropriate chronological order, as can be seen at the beginning of the rosary section. The white rose marking the prologue to the rosary appears on folio 18 and is followed by several uninscribed twelfth-century images of the life of the Virgin. A second rose announces the beginning of the rosary itself (fig. 7) and is followed by an uninscribed image of the Marriage of the Virgin and then by the Annunciation (fig. 6), below which is written the first clausula. While the life of the Virgin pictures did not mark points in the prescribed meditation, they clearly amplified the spirit of the prayer and materially enhanced the value of the book.

The fifteenth-century iconography more generally echoes elements of contemporary church decoration. The rose-en-soleil motif that punctuates the rosary prayers (fig. 8) is widespread, often in fragmentary form, in fifteenth-century windows across Norfolk and Suffolk. This is seen in several fifteenth-century quarries found in the restored church at Foulsham (fig. 9) and, demonstrating the association of this formerly heraldic device with the Virgin, in a border around one of the Annunciation windows at Bale (fig. 10). Such architectural correspondences are seen as well in the Fifteen Signs miniatures at the end of the manuscript (fig. 5). The design elements in the upper corners appear to echo the decorative cornicing found in the windows of the same subject in York (fig. 11). The incorporation of imagery found in the architectural spaces of contemporary churches speaks to the kind of environmental response that informed the creation of the new devotional book and suggests that the book functioned as a virtual liturgical space one entered through private reading. The rosary preface clearly indicates that the individual using the book was not an isolated reader. As beneficiary of all the prayers of the other members of the far-flung Confraternity of the Rosary, the reader was participating in an imagined community performance. In this respect, the manuscript echoed both the physical and symbolic elements of the material church.

Reinscribing Herod

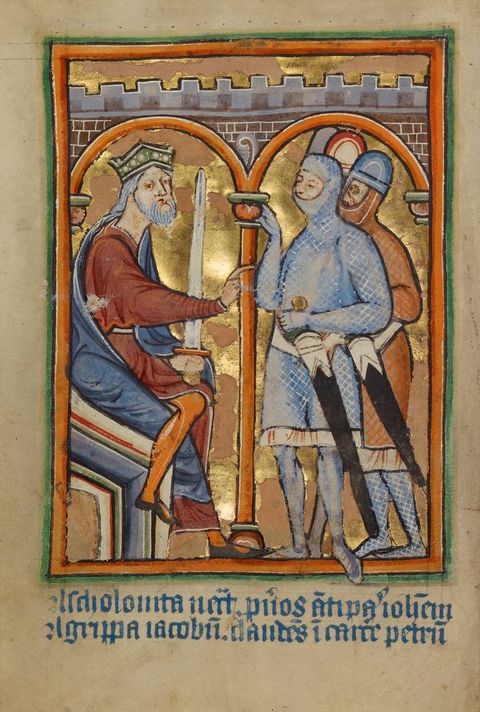

The rosary formed the framework for the fifteenth-century vita Christi programme, and the captioning of the twelfth-century pictures for the most part served to integrate the older pictures into the fifteenth-century devotional practice. Several miniatures deviating from this system invite closer examination. Three images of Herod (or in one instance an image that became Herod) were enhanced with captions and embellishments that draw particular attention to the massacre narrative. The Herod pictures were reinscribed, textually and pictorially. Unlike the rosary prayers, the texts in these instances serve as explanatory captions, with passages either excerpted from or informed by the Golden Legend of Jacobus de Voragine.

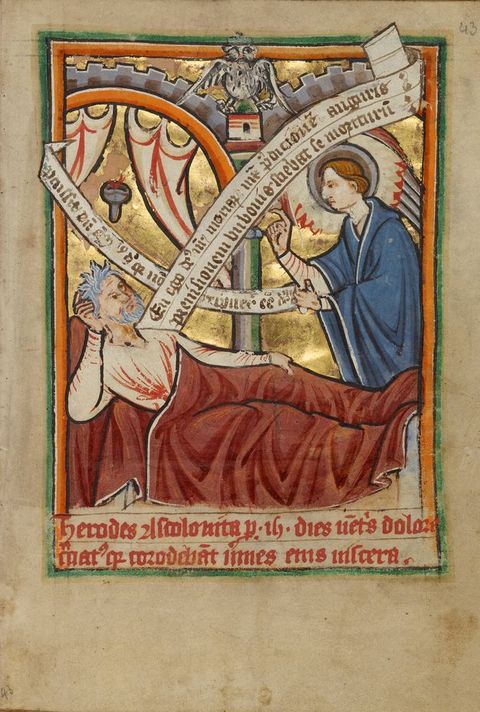

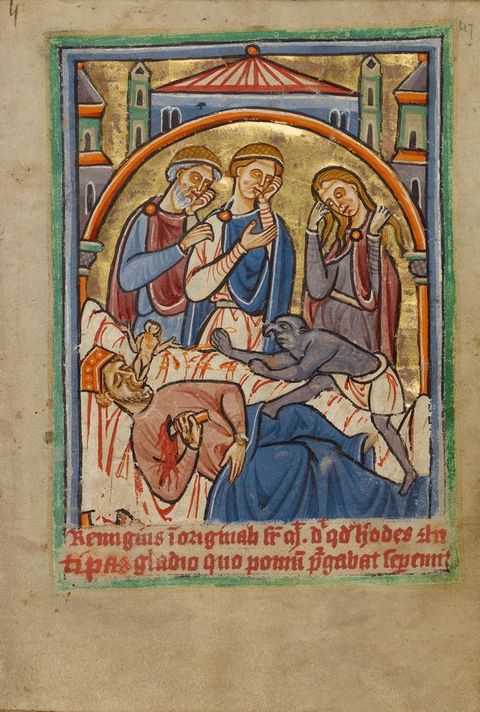

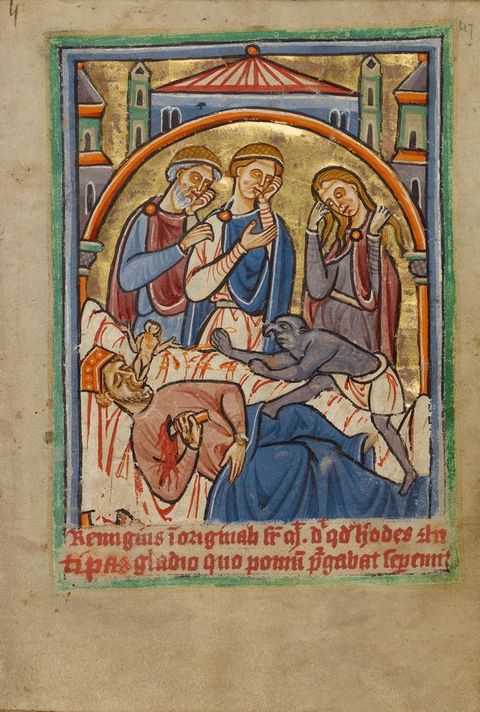

The first addition, to the image of Herod giving orders to his soldiers, specifies the evil deeds of the various kings who shared the name of Herod: Herod Ascalon, Herod Antipas, and Herod Agrippa (fig. 12).19 Jacobus de Voragine identifies them by their evil deeds. Herod of Ascalon, also known as Herod the Great, was the ruler to whom the murder of the Innocents was ascribed. Antipas was his son, and Agrippa his grandson. Antipas was the cruel tyrant to whom Pilate sent Christ and who was also responsible for the murder of John the Baptist. Agrippa executed St James and imprisoned St Peter.20 The caption added to the image of Herod and his soldier specifies Herod Ascalon’s killing of the Innocents. The second captioned image constitutes both a textual and a pictorial intervention. Formerly a twelfth-century image of the Dream of Joseph, in which Joseph is warned by an angel to flee, the reclining figure here has been transformed into Herod (fig. 13). A caption explains that “Herod of Ascolon was tortured with a sickness of the stomach for fifteen days because worms ate away at his entrails” (Herodes Ascolonita per. 15. dies uentris dolore cruciatus quia corodebant uermes eius uiscera).21 The text in the banderoles however, along with the addition of the owl, relate events from the death of his grandson Herod Agrippa, who had been warned that the owl would be a portent of his death, which would occur within five days: “Behold I our god, will die according to the prediction of the Augur. According to the appearance of the owl, he knew he was going to die” (En ego deus noster moriar iuxta predicionem auguris preuisionem bubonis sciebat se moriturum).22

19The decision to transform the image and the story, eradicating Joseph and borrowing text about Herod Agrippa’s impending death to describe the death of Herod Ascalon, may have been an attempt to build momentum to the rare suicide image that appears several folios later, on folio 47 (fig. 14). The story of Herod’s suicide has its roots in Josephus’s Jewish Antiquities, according to which the king was so overcome by an excruciating, and apparently disgusting illness that he took an apple and called for a knife with which to pare it. He then lifted a hand to stab himself, but was prevented by his cousin Achiab.23 He died from his illness five days later, although subsequent retellings abridged the account from an attempted suicide and later death to a conclusive suicide. The image in the Getty manuscript lacks the apple but has an added caption, also from the Golden Legend, that reads: “In his original (commentary) on the Gospel of Matthew, Remigius said that Herod Antipas killed himself with a knife with which he was peeling an apple” (Remigius in originali super mattheum . dicit quod herodes antipas gladio quo pomum purgabat se peremit).24 Rather than adding clarity, these inscriptions once again scramble Herods. The caption connects the suicide story of Herod Ascalon to his son and heir Herod Antipas. This confusion is puzzling, but not without precedent. Such conflation was a characteristic of the English mystery plays performed for the feast of Corpus Christi.25 Herod, who had a leading role in the Epiphany plays from the twelfth century onward, came to have more pronounced dramatic presence in the fifteenth century; Herod’s successful suicide is first documented in this medium during this period. In the Corpus Christi plays, one Herod’s deeds were merged with the others in order to maximize the evil qualities of the protagonist.26 In the Vita Christi manuscript, the amplification of Herod by similar means and the addition of the captions can be seen as a contemporaneous attempt to achieve this kind of villainous concentrate, while working with the existing images in the book.

23The fifteenth-century manipulation of the Herod images comprises the most emphatic series of interventions in the earlier pictures. They are the only illuminations to receive explanatory captions—all other captions are related to the rosary prayers or to a prayer on the Seven Last Words of Christ.27 While the captions ultimately introduce as much confusion as clarity, they do highlight and draw attention to this potion of the book, physically underscoring the importance of the infancy cycle, and particularly to the massacre narrative.

27

Robert of Bury

The key to the added emphasis on the Herod images appears in the pages that directly follow the image of Herod and the Owl. The manuscript contains the only extant image of Robert of Bury, along with a prayer to the saint. Robert was a young child said to have been murdered by Jews in 1181.28 Like the better-known ritual murder cults of William of Norwich and Harold of Gloucester, Robert’s cult was created in the twelfth century, during a period of growing anti-Judaism that included mob violence and the curtailment of legal rights.29 In 1190 there was a riot in Bury in which fifty-seven Jews were massacred. Later that year, all of Bury’s Jewish residents were driven from the town by the order of the abbot. A hundred years later England’s Jewish population was driven from the country.

28The ritual murder accusations involved stories of Christian children who were “sacrificed” by Jews for use in blood rites. The story of William of Norwich’s mock crucifixion at the hands of the Jews was invented by his determined hagiographer, Thomas of Monmouth, several years after William’s body was found in the woods outside Norwich.30 Elements from Thomas’s own account make it apparent that not all believed the story, but this particular manifestation of anti-Jewish behaviour was to have a lasting impact on Jewish–Christian relations for centuries to come.

30As Emily Rose has demonstrated, not all ritual murder cults were driven by the same motivations.31 While certainly fuelled by anti-Jewish sentiment, Robert’s cult initially seems to have been a calculated and top-down operation initiated as part of Samson’s bid for the abbacy of Bury St Edmunds. His competitor for the abbacy, William the Sacristan, was maligned for his purported friendships with Jewish money lenders, who he was said to have allowed into the abbey church during the Mass.32 However, the expulsion had much to do with a larger power struggle, namely Samson’s assertion of jurisdictional independence from royal justices in the Liberty of St Edmund. The Jews, who were deemed “king’s men” (possessing recourse to hearings by the king’s justices) were forced from the community, leaving behind property and debts owed to them.33 Robert’s cult therefore began with the politically motivated actions of the community’s leader, and unlike that of William of Norwich or the later Little Hugh of Lincoln, it left few traces.34 Writing in the mid-1190s, the monk Jocelin of Brakelond recorded the child’s death in 1181.35 Jocelin’s chronicle alludes to a vita, unfortunately now lost, and a burial within the abbey church.36 Gervase of Canterbury supplied the additional details that the child was murdered at Easter and by Jews—a key element in the ritual murder myth was that Christian children were used for Jewish rituals that mocked the crucifixion.37 The death of William of Norwich was regarded in this way, while Robert’s death occurred at Easter.38 Although this is the only image of St Robert to survive, an eighteenth-century description of a now-lost panel painting on a rood screen in Erpingham indicates a wider diffusion of his cult outside of Bury.39 A prayer appearing in a late fifteenth-century prayer book in Oxford attests to the persistence of the cult in the late Middle Ages, as does an early sixteenth-century record of payments to cantors in Robert’s chapel on his feast day.40

31In the Getty Vita Christi, the image with scenes related to Robert’s martyrdom represent not only the sole pictorial record of the child saint, but also the one hagiographic illumination in the book. A prayer to the saint appears on the facing page. The miniature and its preceding prayer were added to the backs of a twelfth-century Dream of Joseph (now Herod) and the Flight into Egypt. All of these images were embedded within the miscellany’s litany among the martyrs, effectively casting Robert as one of the Holy Innocents (fig. 15). Robert, interestingly, is not named in the manuscript’s litany.

Several scenes relating to the martyrdom of the child saint unfold across the upper register. To the left, a veiled woman lowers Robert into a well. A scroll issues from her with the words, “the woman wished but was not able to hide this lamp of God” (voluit set non potuit anus abscondere lucernam dei). The language of the accompanying prayer is general, offering scant clues to the events depicted, but more can be deduced by a poem written by John Lydgate (1370–c. 1449/1450?), a poet and monk at Bury St Edmunds.41 Lydgate wrote that Robert, a suckling infant, was far from his nurse when the murder occurred. The woman is thus perhaps his nurse, a figure who in European accounts of child murder was often cast as the accomplice.42 The body of Little Hugh of Lincoln was said to have been hidden in a well after his death, and the woman at the top-left corner of the Vita Christi’s miniature may be engaged in similarly clandestine activity.43 Lydgate also wrote that Robert was scourged and nailed to a tree, a martyrdom much like that suffered by William of Norwich, whose body was found in a forest. At the right of the picture an archer draws his bow with his left hand, facing a tree under which lies the child’s body. A golden sun blazes overhead. One line in Lydgate’s poem refers to Bury’s eponymous saint as a bright sun with whom Robert’s star would shine. Given that Edmund was martyred by being shot with arrows and then beheaded by the Danes, this image may have attempted to align the child saint with the abbey’s primary saint. Between and above the two scenes with the woman and archer, Robert’s soul is lifted to heaven.44

41A red-robed and tonsured supplicant kneels in the miniature’s lower register before a crimson scroll, which shows a red-breasted robin on a document with a seal. Christopher De Hamel has suggested that the book was assembled for a private owner, possibly a devout layman, although not necessarily the patron.45 Both the added prayer and the miniature were painted on the backs of twelfth-century miniatures, making it clear that these elements were part of the wholesale reconceptualization of the manuscript. Whether the person who commissioned the manuscript or the person for whom it was intended, the figure individualizes the sole hagiographic miniature in the manuscript. While contemporary print culture provides examples of generic images of kneeling devotees (see, for example, a pasted-in print of a Carthusian kneeling before Christ in a contemporary manuscript in the British Library), this image was created specifically for the reworked manuscript.46 A banderole issues from the robed figure with the words: “May he have mercy on me by the merits of St Robert, now and forever” (Meritis sancti Roberti hic et in euum misereatur mei). The object he kneels in front of is ambiguous. While often described as a scroll representing the Liberty of St Edmund, the properties over which the abbey had been granted independent jurisdiction by King Edward the Confessor in 1044, the object is not easily categorized. Warner first described it as drapery in the shape of a sail, while De Hamel described it as a textile wall hanging.47 Its long rectangular shape curls upward at the bottom of the miniature, framing a charter, rendered as a parchment-coloured square with dangling seal, against a swathe of dark crimson. However, its looped edges appear to be supported by a blue shaft. This may be simply a compositional device meant to divide the zones of the image, but could be intended as a staff with a pennon bearing a badge.48 The red-breasted robin has been interpreted generically as a reference to Christ, who shed blood for humanity, and also as a play on Robert’s name.

45Two inscriptions on the manuscript’s flyleaves indicate that the book was in the possession of Robert Themilthorpe, age forty-two, in 1594.49 Anthony Bale has suggested that the painted figure is an earlier family member, also called Robert Themilthorpe, a deputy steward for the crown, and that his tonsure was an expression of piety rather than an indication of clerical status.50 Building on Warner’s earlier note that Roger Themilthorpe had presented to the rectory of Themilthorpe, near Foulsham, in 1586, Bale pointed out that the church at Foulsham was dedicated to the Holy Innocents, who were the religious precursors of the ritual child murder saints of the twelfth century.51 The earlier Robert Themilthorpe of Foulsham died in 1505. His will records a generous bequest to the Guild of the Holy Innocents there, as well as to the Guild of the Virgin Mary, and this image of the donor praying before the child saint would have had added significance for him as a member of this congregation.52 The fact that this dedication was shared by only four other churches in England makes it a particularly compelling association, although one of the other churches was that of Great Barton, Suffolk, located only a few miles from Bury. The language of the prayer accompanying the images has been recognized for its local aspect: “Hail sweet boy, blessed Robert, you who flowered in the martyr’s palm in the time of infancy, pray for us to God that we may rejoice in your own town.”53 As already noted, the child Robert is not listed in the accompanying litany, but, as Bale emphasizes, the cult was apparently informal in nature. Four animals—a stag or an antelope, a collared bear, a cat, and an ox—march across the page, under the prayer. They have alternately been proposed as bestiary symbols, a rebus, or with the bear, as a pun on Bury, and may yet provide clues to the manuscript’s provenance.54 More work on the guilds of the Holy Innocents, in Norfolk and Suffolk, may yet lend insight into this puzzling imagery and the manuscript’s fifteenth-century provenance.

49I have suggested elsewhere that the twelfth-century portion of this manuscript (frequently associated on the basis of style and iconography with a group of psalters from the north of England)55 might have been commissioned for an inhabitant of Bury St Edmunds, perhaps even the abbot.56 Abbot Samson had actively promoted the cult of the child saint Robert of Bury through the establishment of a shrine in the abbey church at Bury and by commissioning a vita. This manuscript’s twelfth-century programme, which had a particularly pronounced focus on Herod and the Massacre of the Innocents, as well as the childhood of the Virgin and Christ, would have mirrored the central theme of the new cult dedicated to a murdered child. While little is known of Robert, he was said to have been just a suckling child, distinguishing him from the older William of Norwich (said to have been twelve at the time of his death). Whether or not the twelfth-century book was an artefact of the earlier cult, the fifteenth-century amplification of the Herodian narrative (and implicitly the story of the Massacre of the Innocents) through alterations to the earlier illuminations, speaks to the resonance this narrative had in the region.

55Response, Resonance, and Retrospection in the Getty Vita Christi

The Getty manuscript is distinguished by its remarkable synthesis of old and new images. Ultimately the identity of the tonsured supplicant remains unknown, but the emphasis on an obscure cult and the amplification of the Herod images were clearly meaningful. First created during a period of intense anti-Jewish activity, including mob violence, murder, and accusations in the twelfth century, the child murder cults experienced a resurgence in the fifteenth century, when Jews had been absent from England for two hundred years. The appeal of the twelfth-century child saints’ cults in fifteenth-century England constituted its own form of hagiographic and cultural response, which has generated a large field of study in recent years.57 Lisa Lampert has argued that the fifteenth-century Croxton Play of the Sacrament, with its anti-Semitic tale of Jewish host desecrators/Christ killers, enabled viewers simultaneously to engage with biblical and local history. She argues that the play, which refers to little Robert’s death, overlaid Christ’s murder with that of Robert, thus bringing biblical history into the “eternal present”.58 The Getty manuscript, with its reuse of the older Romanesque illuminations, does much the same. Through captioning and the insertion of the Robert miniature into the Herod programme, the Holy Innocents were brought forward into the environment of the early modern reader, just as valued images from Robert’s own era were embedded in a contemporary book.

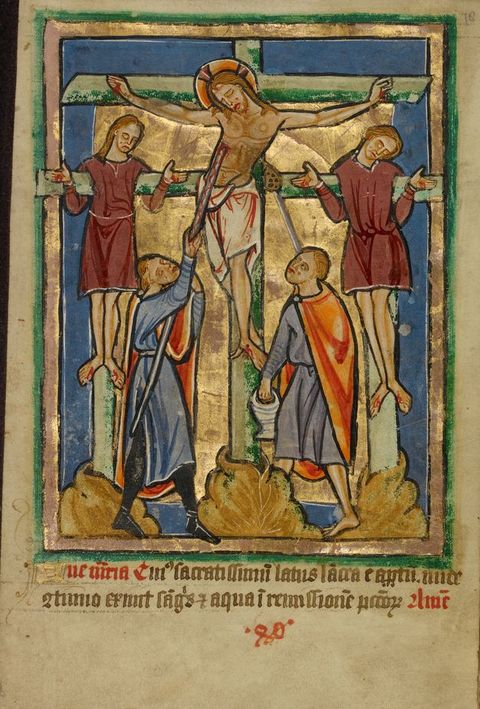

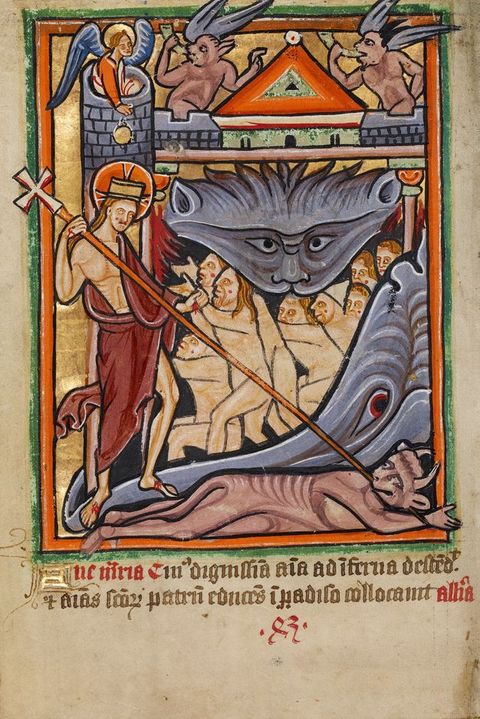

57The preservation of pictures in the prayer book is not in itself unusual, but the comprehensive inclusion of the earlier Romanesque illuminations does suggest that they held symbolic and material value for the fifteenth-century patron. This kind of repurposing proliferated throughout the Middle Ages: one need think only of Abbot Suger, who describes the Carolingian foundations of his new church as “stones like relics”.59 What is striking is the degree to which this book’s makers synthesized new and old. The reuse of medieval manuscripts is often an accretive process, but in this case the makers accommodated the older elements both structurally and aesthetically into one campaign. The late medieval makers wove new texts and images throughout the book, using the blank backs of the older illuminations but preserving the existing quire structures where possible. The care taken to preserve the older miniatures is seen particularly in one instance, where the fifteenth-century artists went so far as to re-gild losses to the twelfth-century golden backgrounds.60 These artists also aesthetically softened the distinctions between the two campaigns. The later illuminations echo the size and dimensions of the earlier works, although the fifteenth-century illuminations are squarer in shape. Several different artists worked on the fifteenth-century additions, and one noticeably echoed the elongated forms of the Romanesque figures, as seen in several images of Christ on the Cross (figs 16 and 17). Although gold was used less freely in the later works, in certain miniatures, such as those of the Crucifixion, the artist echoed the golden backgrounds of the earlier miniatures, clearly bringing the newer images into line with the Romanesque cycle. Linear gold frames, quite unlike the foliate frames used on the Old Testament subjects at the beginning of the manuscript, were used around the fifteenth-century miniatures in this section. The golden frames resemble those seen on the Romanesque Crucifixion (fig. 17) and Deposition, further synthesizing old and new. A possible nod to the Romanesque Hellmouth appearing on folio 82v, moreover, is seen as well in the fifteenth-century Fall of the Rebel Angels on folio 6 (fig. 18 and see fig. 4).

59

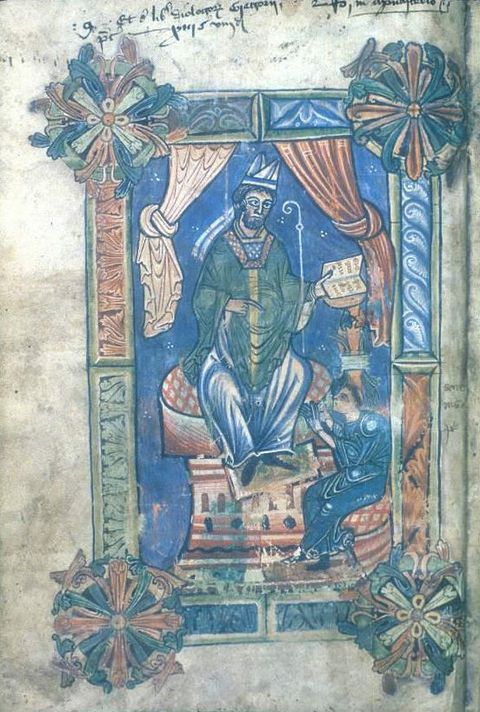

This pronounced effort to bring the older image into line with new devotional practice invites consideration of the ways the Romanesque pictures may have evoked Bury’s past. A similar example of artistic synthesis is seen in the redrawing of an image of Gregory the Great in an Anglo-Saxon copy of his Dialogues (fig. 19). The figure was retraced by a later artist who nevertheless left visible the lines of the earlier illumination. Catherine Karkov discusses the process of tracing as “an act of historical remembering”, binding present and past.61 Similarly, Larry Nees has discussed the motivations of Ottonian illuminators who embellished Carolingian Gospel books; prized for their association with missionaries, small-format Gospel books evoked a significant period in Christian conversion and served as a material link to that aspect of Christian history.62 Historical remembering is an essential concept when considering the motivations for the Getty Vita Christi’s renewal. The reuse of images speaks not only to a sense of general retrospection in late medieval manuscript culture but also marries this book to a significant period for Robert’s cult.

61acknowledgements: "I am grateful to the staff at the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art for jointly organising the Invention and Imagination conference, and for the support that led to this publication; as well as to the circle of colleagues who have read and commented on this manuscript over the past several years, especially especially Peter Kidd, Richard Leson, and Nancy Turner. The visualisation of the Getty manuscript’s quire structure presented in the the essay (fig. 2) would not have been possible without Nancy Turner’s collaboration. I am particularly grateful to Sandy Heslop and Jessica Berenbeim for their close reading of this essay and their insightful suggestions for its improvement.

About the author

-

Kristen Collins is Curator of Manuscripts at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles. She has co-curated numerous exhibitions including *Holy Image, Hallowed Ground: Icons from Sinai (2006) and Canterbury and St Albans: Treasures from Church and Cloister (2013). Her recent work in the field of twelfth-century English manuscript illumination will appear in the forthcoming 2017 symposium proceedings volume, St Albans and the Markyate Psalter: Seeing and Reading in Twelfth-Century England, for which she is also co-editor. Recurring themes in both exhibitions and scholarship have been issues of reuse and retrospection in manuscript illumination.

Footnotes

-

1

Fundamental bibliography on the manuscript includes detailed catalogue entries by Sir George Warner, Descriptive Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts in the Library of C. W. Dyson Perrins, D.C.L., F.S.A. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1920), 1–8; Nigel Morgan, Early Gothic Manuscripts, 1190–1250: A Survey of Manuscripts Illuminated in the British Isles, Vol. 4 (London: Harvey Miller, 1982), 50–53; Christopher De Hamel, Western and Oriental Manuscripts, Sotheby’s Sale Catalogue, 4 December 2007, lot 45, 66–87. For a discussion of the manuscript’s twelfth-century programme, see Kristen Collins, “Madness and Innocence: Reading the Infancy Cycle in a Romanesque Vita Christi”, in St Albans and the Markyate Psalter: Seeing and Reading in Twelfth-Century England, ed. Collins and Matthew Fisher (Kalamazoo, MI: Medieval Institute Publications, 2017). Full bibliography can be found on the Getty Museum website: http://www.getty.edu/art/collection/objects/243710. ↩︎

-

2

The additions to the book have been dated to around 1480–90 on the basis of style. An indulgence for those who pray the rosary dated to 1479 establishes the terminus post quem for the reconstituted miscellany. ↩︎

-

3

A reconstruction of the original twelfth-century quire structure is published as an appendix to Collins, “Madness and Innocence”. A stub between fols 39 and 40 indicates the loss of one miniature following the Presentation in the Temple. Despite Warner’s suggestion that more miniatures were missing around fol. 68, there are no other obvious losses to the twelfth-century quires, which are all eights except the final quire, which was a four. Its two bifolia were separated into singletons in the fifteenth-century rebinding. Although it is conceivable that the end of the programme could have contained additional material, the quire structure does not indicate this. ↩︎

-

4

For a discussion of the twelfth-century context, see Kristen Collins “Madness and Innocence”. Two examples of so-called “picture bibles” dating to the thirteenth century can be found in the John Rylands Library and in the Chicago Art Institute: John Rylands Library, Ms. French 5 (first quarter of the thirteenth century, France or Flanders, 18.5 x 14.5 cm), see Caroline Hull, “Rylands MS French 5: The Form and Function of a Medieval Bible Picture Book”, Bulletin of the John Rylands University Library of Manchester 77 (1995): 3–24; Chicago Art Institute 1915.533 (mid-thirteenth-century, northern France or Flanders, 17 x 12 cm), see Exhibition of Illuminated Manuscripts, Burlington Fine Arts Club (London, 1908), cat. no. 57; William Noel, The Oxford Bible Pictures: Ms. W.106: The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore and the Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris (Baltimore and Luzern: The Walters Art Museum and Faksimile Verlag Luzern, 2004). ↩︎

-

5

For the Marian scenes, see Jacqueline Lafontaine-Dosogne, Iconographie de l’Enfance de la Vierge dans l’Empire Byzantin et en Occident, Vol. 2 (Brussels: Royal Academy of Belgium, 1965), 25, 64, 75, 82, 87, 106, 120, and 161. For more on the twelfth-century emphasis on childhood scenes and the Herodian narrative, see Collins, “Madness and Innocence”. ↩︎

-

6

New York, Morgan Library and Museum, Ms. M.736, Bury St Edmunds, c. 1130. C. M. Kauffmann, Romanesque Manuscripts, 1066–1190 (London: Harvey Miller, 1975), no. 34; Elizabeth Parker McLachlan, The Scriptorium of Bury St Edmunds in the Twelfth Century (New York: Garland, 1986), 74–119, 330–32; Cynthia Hahn, “Peregrinatio et Natio: The Illustrated Life of Edmund, King and Martyr”, Gesta 30, no. 2 (1991): 119–39. ↩︎

-

7

Oxford, Bodleian Library Ms. Gough Liturg. 2. Falconer Madan, A Summary Catalogue of Western Manuscripts in the Bodleian Library at Oxford, Vol. 4: Collections Received during the First Half of the 19th Century (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1897), no. 18343; Otto Pächt and J. J. G. Alexander, Illuminated Manuscripts in the Bodleian Library Oxford, Vol. 3: British, Irish, and Icelandic Schools (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1973), no. 290; C. M. Kauffmann, Romanesque Manuscripts, cat. no. 97, 120–21; Elizabeth Solopova, Latin Liturgical Psalters in the Bodleian Library: A Select Catalogue (Oxford: Bodleian Library, 2013), 63–71; Martin Kauffmann, “Praying With Pictures in the Gough Psalter”, in St Albans and the Markyate Psalter, ed. Collins and Fisher. ↩︎

-

8

A single elevation prayer was added to fol. 31 in the first half of the thirteenth century, about fifty years after the manuscript was first illuminated, see Collins “Madness and Innocence” for the dating of the script. ↩︎

-

9

Warner, Descriptive Catalogue, 3. Warner notes the fifteenth-century addition of text on the scrolls but more often, the speech scrolls themselves were added in the fifteenth century. The Annunciation to Joachim (fol. 19), the Annunciation to the Virgin (fol. 26), and the Annunciation to the Shepherds (fol. 30) likely had uninscribed twelfth-century speech scrolls, which were subsequently reshaped and inscribed in the fifteenth century. As, for example, in the Annunciation to the Shepherds (fol. 30) and the Dream of Joseph/ Angel Appearing to Herod (fol. 43), additional scrolls were added as well. The manuscript contains only two examples of text added between the first campaign and the fifteenth century: the early thirteenth-century prayer to Christ on fol. 31 mentioned in note 8, and a paste-down with the word “Alleluya” on burnished gold in fourteenth-century script appearing on fol. 24v. ↩︎

-

10

William W. Heist, The Fifteen Signs Before Doomsday (East Lansing, MI: Michigan State College Press, 1952). ↩︎

-

11

The manuscript consists of fifty-one twelfth-century and fifty-five fifteenth-century leaves. Various prayers and fifty-seven full-page miniatures were added to both twelfth- and fifteenth-century portions. See fig. 2. ↩︎

-

12

Warner, Descriptive Catalogue, 1–2. ↩︎

-

13

The Getty cycle now lacks images and meditations number thirty-five through thirty-nine, an indication that a least five fifteenth-century images (perhaps more that were not connected to rosary devotions) have been lost. The missing rosary meditations in Getty Ms. 101 would have addressed Christ’s final hours on the Cross. ↩︎

-

14

Fol. 18v: “For in the year of our lord 1431, there was a devout Carthusian father in the monastery previously mentioned who, after his departure from this life, left in writing that a brother of his order was accustomed to pray with great devotion by reciting contritely that rosary of the Virgin Mary recorded unchanged below” (Nam anno domini . 1431 . fuit in monasterio iam dicto deuotus pater carthusiensis qui post vite huius decessum scripto reliquit . quod frater quidam sui ordinis se exercere consueuit cum magna deuocione in marie uirginis rosa-rie illud immodum infra scriptum compunc-te legendo). ↩︎

-

15

For the fifty clausulae of Dominic of Prussia, see K. J. Klinkhammer, Adolf von Essen und seine Werke: Der Rosenkranz in der geschichtlichen Situation seiner Entstehung und in seinem bleibenden Anliegen. Eine Quellenforschung, Frankfurter Theologische Studien 13 (Frankfurt: Josef Knecht, 1972), 198–201. Credit for the invention of this particular form of the rosary remains a disputed topic. See Dennis D. Martin, “Behind the Scene: The Carthusian Presence in Late Medieval Spirituality”, in Nicholas of Cusa and his Age: Intellect and Spirituality: Essays Dedicated to the Memory of F. Edward Cranz, Thomas P. McTighe and Charles Trinkaus, ed. Thomas M. Izbicki and Christopher M. Bellitto (Leiden, Boston, and Cologne: Brill, 2002), 29–62. On 53–55, Martin credits Adolf of Essen (d. 1439), a Trier monk whose work preceded Dominic’s (and indeed, whom Dominic credits as the originator of this prayer) as well as Dominic with the creation of a form of rosary that integrated vita Christi meditations with vocal Aves. Winston-Allen also argues against Dominic as inventor: Ann Winston, “Tracing the Origins of the Rosary: German Vernacular Texts”, Speculum 68 (1993): 627. For the purpose of this discussion, the “Carthusian Rosary” is used to refer to the form of the prayer structured around fifty life of Christ meditations rather than to the specific version attributed to Dominic. ↩︎

-

16

Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek Darmstadt, HS.1830. Thomas Esser, “Beitrag zur Geschichte des Rosenkranzes: Die ersten Spuren von Betrachtungen beim Rosenkranz”, Der Katholik 77 (1897): 346–60, 409–22, 515–28; Andreas Heinz, “Die Entstehung des Leben-Jesu-Rosenkranzes”, in Der Rosenkranz: Andacht, Geschichte, Kunst, ed. Fredy Bühler and Urs-Beat Frei (Bern: Verlag Benteli/ Museum Bruder Klaus Sachseln, 2003), 23–47. ↩︎

-

17

Ann Winston-Allen, Stories of the Rose: The Making of the Rosary in the Middle Ages (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1997), 22. Unser lieben frauen Psalter was published in Ulm by Conrad Dinckmut in 1483. It was issued in about seven editions by 1503. This manual offered seven different versions of the rosary along with fifteen woodcuts constituting the first picture rosary. Only several decades later does one find another example with the scope of illustration seen in the Getty Vita Christi. The Antwerp printer Lanspergius printed The Mystic Sweet Rosary of the Faithful Soul in 1533; it was printed in English with full-page woodcuts illustrating each meditation. See Jan Rhodes, “The Rosary in Sixteenth-Century England”, Mount Carmel: A Quarterly Review of the Spiritual Life 31, no. 4 (1983): 6–7. ↩︎

-

18

An image of the Transfiguration appears on fol. 55v, accompanying a prayer in praise of the Passion. ↩︎

-

19

Getty Ms. 101, fol. 40v. ↩︎

-

20

The Golden Legend of Jacobus de Voragine, trans. Granger Ryan and Helmut Ripperger (New York: Arno Press, 1969). ↩︎

-

21

Getty Ms. 101, fol. 43. ↩︎

-

22

Warner, Descriptive Catalogue, 4, notes the confusion of Herods. From Josephus, Jewish Antiquities 19:8:2, 343–61, Acts 12, 23, and the Golden Legend 110. ↩︎

-

23

Josephus, Jewish Antiquities 17:184. ↩︎

-

24

Getty Ms. 101, fol. 47. ↩︎

-

25

Miriam Anne Skey, “Herod the Great in Medieval European Drama”, Comparative Drama 13, no. 4 (1979–80): 330–64, esp. 332–33. ↩︎

-

26

Scott Colley, “Richard III and Herod”, Shakespeare Quarterly 37, no. 4 (1986): 451–58, 452; S. S. Hussey, “How Many Herods in the Middle English Drama?”, Neophilologus 48 (1964): 252–59. ↩︎

-

27

This caption appears above an image of the crucified Christ on fol. 72v, with the numerals 1–7 appearing above the words of the rosary meditation below. ↩︎

-

28

Warner, Descriptive Catalogue, 6; Rev. H. Copinger Hill, “S. Robert of Bury St. Edmunds”, Proceedings of the Suffolk Institute of Archaeology and Natural History 21 (1932): 98–105; Anthony Bale, The Jew in the Medieval Book: English Antisemitisms, 1350–1500 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006); Bale, “‘House Devil, Town Saint’: Anti-Semitism and Hagiography in Medieval Suffolk”, in Chaucer and the Jews: Sources, Contexts, Meanings, ed. Sheila Delany (New York: Routledge, 2002), 185–210; Emily Rose, The Murder of William of Norwich: The Origins of the Blood Libel in Medieval Europe (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), 186–206. ↩︎

-

29

Gavin Langmuir, Toward a Definition of Antisemitism (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1990). See Langmuir for a discussion of anti-Judaism and anti-Semitism. Since Langmuir’s seminal studies, the body of work treating the subject of ritual child murder has grown over the past decades. See Joe Hillaby, “The Ritual-Child-Murder Accusation: Its Dissemination and Harold of Gloucester”, Jewish Historical Studies 34 (1994–96): 69–109; Gavin Langmuir, “The Knight’s Tale of Young Hugh of Lincoln”, Speculum 47, no. 3 (1972): 459–82; John M. McCulloh, “Jewish Ritual Murder: William of Norwich, Thomas of Monmouth, and the Early Dissemination of the Myth”, Speculum 72, no. 3 (July 1997): 698–740; Sheila Delany, “Chaucer’s Prioress, the Jews, and the Muslims”, in Chaucer and the Jews: Sources, Contexts, Meanings, ed. Delany (New York and London: Routledge, 2002), 43–58; Rose, Murder of William of Norwich. ↩︎

-

30

Thomas of Monmouth, The Life and Miracles of St William of Norwich, ed. Augustus Jessopp and M. R. James (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1896), 15. ↩︎

-

31

Rose, Murder of William of Norwich. Rose cautions against a blanket reading of the motivations behind these various cults and Christian-Jewish relations. ↩︎

-

32

Jocelin of Brakelond wrote that under William’s protection, the Jews of Bury “had free entrance and exit, and went everywhere throughout the monastery, wandering by the altars and about the feretory, while masses were being sung, and their money was kept in our treasury, under the Sacrist’s custody” (“et liberum ingressum et egressum habebant, et passim ibant per monasterium, uagantes per altaria et circa feretrum, dum missarum celebrarentur sollemnia; et denarii eorum in thesauro nostro sub custodia sacriste reponebantur”). The Chronicle of Jocelin of Brakelond, trans. H. E. Butler (London: Thomas Nelson and Sons Ltd, 1949), 10; Daniel Gerard, “Jocelin of Brakelond and the Power of Abbot Samson”, Journal of Medieval History 40, no. 1 (2014): 1–23. ↩︎

-

33

Rose, Murder of William of Norwich, 203. Rose argues that the operative tensions leading to the Bury expulsion were those between the community of Bury and the crown, with the Jewish population serving as scapegoats in the larger power struggle. See also Gerard, “Jocelin of Brakelond”, 1–23; Michael Widner, “Samson’s Touch and a Thin Red Line: Reading the Bodies of Saints and Jews in Bury St Edmunds”, Journal of English and Germanic Philology 3, no. 3 (July 2012): 339–59, esp. 341–42. ↩︎

-

34

Anthony Bale suggests that the cult may have survived in fits and starts rather than as a flourishing practice over the centuries. Bale, Jew in the Medieval Book, 111–12; Bale, “‘House Devil, Town Saint’”, 185–210. ↩︎

-

35

Jocelin de Brakelond, The Chronicle of Jocelin of Brakelond, Concerning the Acts of Samson, Abbot of the Monastery of St. Edmund, trans. Diana Greenaway and Jane Sayers (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989), 15. ↩︎

-

36

Copinger Hill, “S. Robert of Bury”, 99. Copinger Hill mentions a later account of the chapel, noting that it is not marked on any of the Abbey’s plans. ↩︎

-

37

Bale, Jew in the Medieval Book, 108, n. 10; Heather Blurton, “Egyptian Days: From Passion to Exodus in the Representation of Twelfth-Century Jewish-Christian Relations”, in Christians and Jews in Angevin England: The York Massacre of 1190, Narratives and Contexts, ed. Sarah Rees Jones and Sethina Watson (York: York Medieval Press, 2013), 224. ↩︎

-

38

Thomas of Monmouth, Life and Miracles, 15. ↩︎

-

39

Copinger Hill, “S. Robert of Bury”, 99–100. The screen showed a patron kneeling before a child identified by inscriptions as St Robert. Ann Eljenholm Nichols, The Early Art of Norfolk: A Subject List of Extant and Lost Art including Items Relevant to Early Drama, Early Drama, Art, and Music Series 7 (Kalamazoo, MI: Medieval Institute Publications, 2002), 226. The Chapel of St Anne in St Peter Mancroft in Norwich was also said to serve as a pilgrimage destination for devotees to Robert’s cult. ↩︎

-

40

The prayer appears in Oxford Bodleian Library Ms. Laud misc. 683 and is published as Appendix 2 in Bale, Jew in the Medieval Book, 173–74. ↩︎

-

41

Copinger Hill, “S. Robert of Bury”, 98–105. Both Bale, Jew in the Medieval Book, and Rose, Murder of William of Norwich, offer a close reading of this image in relation to the Lydgate poem. ↩︎

-

42

Bale, Jew in the Medieval Book, 114. ↩︎

-

43

Langmuir, “Knight’s Tale”, 466. ↩︎

-

44

Copinger Hill, 100. Copinger Hill notes that on an abbey seal (of unknown date) St Edmund is shown similarly lifted to heaven in a cloth. ↩︎

-

45

De Hamel, Western and Oriental Manuscripts, 67. He suggests the hermit Robert Leake of Blytheborough, Suffolk, as a possible candidate. ↩︎

-

46

British Library, Egerton Ms. 1821, fol. 9v, c. 1480–90. Francis Aidan Gasquet, “An English Rosary Book of the 15th Century”, Downside Review 12 (1893): 215–28. ↩︎

-

47

Warner, Descriptive Catalogue, 6. De Hamel, Western and Oriental Manuscripts, 81. ↩︎

-

48

Warner, Descriptive Catalogue, 6. ↩︎

-

49

His name appears on fols 4 and 4v. Two other sixteenth-century inscriptions, Susanna Flint and John Pinchbeck, appear on fol. 1. ↩︎

-

50

Warner first connected the signature to Robert Themilthorpe, who had presented to the rectory of Themilthorpe, near Foulsham in 1586. Warner, Descriptive Catalogue, 8. Bale suggested that the figure’s costume of fur-lined robe could identify the figure as an employee of the crown. A 1363 statute decreed that fur could only be worn by royals and those serving in royal office. Royal clerks had a dispensation allowing the wearing of fur. Bale, Jew in the Medieval Book, 119. ↩︎

-

51

Bale, Jew in the Medieval Book, 119. ↩︎

-

52

Norwich, Norfolk Record Office, 182:Ryxe, MF 35. I thank Peter Kidd for assistance with this document. ↩︎

-

53

Bale, Jew in the Medieval Book, 121. Although the cult seems to have languished in the centuries following its establishment, an early sixteenth-century record of payments to cantors in Robert’s chapel on his feast day attests to its slight resurgence in the late Middle Ages, as does a Lydgate prayer appearing in a late fifteenth-century manuscript now Oxford, Bodleian Library, Ms. Laud Misc. 683, fols 22v–23. See Bale, Jew in the Medieval Book, 112–18, for a discussion of the Lydgate prayer, and 173–74 for a transcription. ↩︎

-

54

De Hamel, Western and Oriental Manuscripts, 81. ↩︎

-

55

These manuscripts include Oxford, Bodleian Library, Ms. Gough Liturg. 2, Oxford, Bodleian Library, Ms. Douce 293 and Copenhagen, Royal Library Ms. Thott. 143 2̊. See C. M. Kauffmann, Romanesque Manuscripts, 120–21, 117, 118–20, nos. 97, 94, and 96. C. M. Kauffmann suggests a common model for the Gough Psalter and the Copenhagen Psalter on the basis of their strong iconographic and compositional similarities. The two manuscripts have thirteen scenes in common. Nigel Morgan has also noted the probability of a shared iconographic prototype for Getty Ms. 101 and the Gough Psalter. ↩︎

-

56

Collins, “Madness and Innocence”. Despite brief mentions of a possible Bury provenance, no attention has been given to a consideration of this context for the twelfth-century manuscript. Warner first suggested the connection of the manuscript, or at least the fifteenth-century additions, to Bury St Edmunds; Warner, Descriptive Catalogue, 6. Nigel Morgan attributed the manuscript to the north of England, to the same workshop as the Leiden Louis Psalter; Morgan, Early Gothic Manuscripts, 63. Nicholas Rogers indicated a Suffolk provenance for the manuscript; Nicholas Rogers, “Fitzwilliam Museum MS3-1979: A Bury St Edmunds Book of Hours and the Origins of the Bury Style”, in England in the Fifteenth Century: Proceedings of the 1986 Harlaxton Symposium, ed. Daniel Williams (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 1987), 237 and n. 38. De Hamel ascribed the twelfth-century cycle to Bury St Edmunds in 1996 and then to the north of England in the 2007 Sotheby’s sale catalogue. De Hamel, Cutting Up Manuscripts for Pleasure and Profit: The 1995 Sol. M. Malkin Lecture in Bibliography (Charlottesville, VA: Book Arts Press, 1996), 7; De Hamel, Western and Oriental Manuscripts, 66–87. ↩︎

-

57

Gavin Langmuir wrote that “projections of ritual murder, host desecration, and well poisoning inevitably assumed a religious coloration, but in fact they owed more to tensions within the majority society and the psychological problems of individuals than to the real conflict between Christianity and Judaism.” Langmuir, Toward a Definition of Antisemitism, 62. For an overview of such responses throughout the Middle Ages, see Jeremy Cohen, Living Letters of the Law: Ideas of the Jew in Medieval Christianity (Berkeley, CA, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press, 1999). For a discussion of the fifteenth-century context for the anti-Semitic ritual child murder claims in England, see Bale, Jew in the Medieval Book; Sheila Delany, ed., Chaucer and the Jews: Sources, Contexts, Meanings (New York and London: Routledge, 2002); Geraldine Heng, “Jews, Saracens, ‘Black Men’, Tartars: England in a World of Racial Difference”, in A Companion to Medieval English Literature and Culture, c. 1350–c. 1500, ed. Peter Brown (Oxford: Blackwell, 2007), 247–70. ↩︎

-

58

Lisa Lampert, “The Once and Future Jew: The Croxton ‘Play of the Sacrament’, Little Robert of Bury and Historical Memory”, Jewish History 15 (2001): 235–55. ↩︎

-

59

“to respect the very stones, sacred as they are, as though they were relics” (ipsis sacratis lapidibus tanquem reliquiis deferremus): Abbot Suger, On the Abbey Church of St.-Denis and its Art Treasures, ed. and trans. Erwin Panofsky (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1946), 100–1. ↩︎

-

60

Fol. 25v was fully re-gilded and the bole is consistent with that of the fifteenth-century miniatures. Nancy K. Turner, “Reflecting a Heavenly Light: Gold and other Metals in Medieval and Renaissance Manuscript Illumination”, in Illuminating Manuscripts: Art, Science, Conservation, Meaning: Proceedings from the Conference at the Fitzwilliam Museum, 8–10 December 2016, ed. Stella Panayotova (Turnhout: Brepols, 2017), forthcoming. ↩︎

-

61

Catherine E. Karkov, The Art of Anglo-Saxon England (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2011), 287–89. ↩︎

-

62

Larry Nees, “Aspects of Antiquarianism in the Art of Bernward and its Contemporary Analogues”, in 1000 Jahre St. Michael in Hildesheim: Kirche-Kloster-Stifter, ed. Gerhard Lutz and Angela Weyer (Petersberg: Michael Imhof Verlag, 2012), 168. ↩︎

Bibliography

Bale, Anthony. “‘House Devil, Town Saint’: Anti-Semitism and Hagiography in Medieval Suffolk.” In Chaucer and the Jews: Sources, Contexts, Meanings, ed. Sheila Delany. New York: Routledge, 2002, 185–210.

– – – . The Jew in the Medieval Book: English Antisemitisms, 1350–1500. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Blurton, Heather. “Egyptian Days: From Passion to Exodus in the Representation of Twelfth-Century Jewish-Christian Relations.” In Christians and Jews in Angevin England: The York Massacre of 1190, Narratives and Contexts, ed. Sarah Rees Jones and Sethina Watson. York: York Medieval Press, 2013, 222–37.

Cohen, Jeremy. Living Letters of the Law: Ideas of the Jew in Medieval Christianity. Berkeley, LA,

and London: University of California Press, 1999.

Colley, Scott. “Richard III and Herod.” Shakespeare Quarterly 37, no. 4 (1986): 451–58.

Collins, Kristen. “Madness and Innocence: Reading the Infancy Cycle in a Romanesque Vita Christi.” In St Albans and the Markyate Psalter: Seeing and Reading in Twelfth-Century England, ed. Collins and Matthew Fisher. Kalamazoo, MI: Medieval Institute Publications, 2017.

Copinger Hill, H. “S. Robert of Bury St Edmunds.” Proceedings of the Suffolk Institute of Archaeology and Natural History 21 (1932): 98–107.

Delany, Sheila. Chaucer and the Jews: Sources, Contexts, Meanings. New York and London: Routledge, 2002

– – – . “Chaucer’s Prioress, the Jews, and the Muslims.” In Chaucer and the Jews: Sources, Contexts, Meanings, ed. Delany. New York and London: Routledge, 2002, 43–58.

Esser, Thomas. “Beitrag zur Geschichte des Rosenkranzes: Die ersten Spuren von Betrachtungen beim Rosenkranz.” Der Katholik 77 (1897): 346–60, 409–22, 515–28.

Exhibition of Illuminated Manuscripts. Burlington Fine Arts Club. London, 1908.

Gasquet, Francis Aidan. “An English Rosary Book of the 15th Century.” Downside Review 12 (1893): 215–28.

Gerard, Daniel. “Jocelin of Brakelond and the Power of Abbot Samson.” Journal of Medieval History 40, no. 1 (2014): 1–23.

Hahn, Cynthia. “Peregrinatio et Natio: The Illustrated Life of Edmund, King and Martyr.” Gesta 30, no. 2 (1991): 119–39.

De Hamel, Christopher. Cutting Up Manuscripts for Pleasure and Profit: The 1995 Sol. M. Malkin Lecture in Bibliography. Charlottesville, VA: Book Arts Press, 1996.

— — —. Western and Oriental Manuscripts. Sotheby’s, London. 4 December 2007, lot 45, 66–87.

Heinz, Andreas. “Die Entstehung des Leben-Jesu-Rosenkranzes.” In Der Rosenkranz: Andacht, Geschichte, Kunst, ed. Fredy Bühler and Urs-Beat Frei. Bern: Verlag Benteli/ Museum Bruder Klaus Sachseln, 2003, 23–47.

Heist, William W. The Fifteen Signs Before Doomsday. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State College Press, 1952.

Heng, Geraldine. “Jews, Saracens, ‘Black Men’, Tartars: England in a World of Racial Difference.” In A Companion to Medieval English Literature and Culture, c. 1350–1550, ed. Peter Brown. Oxford: Blackwell, 2007, 247–70.

Hillaby, Joe. “The Ritual-Child-Murder Accusation: Its Dissemination and Harold of Gloucester.” Jewish Historical Studies 34 (1994–96): 69–109.

Hull, Caroline. “Rylands MS French 5: The Form and Function of a Medieval Bible Picture Book.” Bulletin of the John Rylands University Library of Manchester 77 (1995): 3–24.

Hussey, S. S. “How Many Herods in the Middle English Drama?” Neophilologus 48 (1964): 252–59.

Jacobus de Voragine. The Golden Legend of Jacobus de Voragine. Trans. Granger Ryan and Helmut Ripperger. New York: Arno Press, 1969.

Jocelin de Brakelond. The Chronicle of Jocelin of Brakelond. Trans. H. E. Butler. London: Thomas Nelson and Sons Ltd, 1949.

– – – . The Chronicle of Jocelin of Brakelond, Concerning the Acts of Samson, Abbot of the Monastery of St Edmund. Trans. Diana Greenaway and Jane Sayers. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989.

Kauffmann, C. M. Romanesque Manuscripts, 1066–1190. London: Harvey Miller, 1975.

Kauffmann, Martin. “Praying With Pictures in the Gough Psalter.” In St Albans and the Markyate Psalter: Seeing and Reading in Twelfth-Century England, ed. Kristen Collins and Matthew Fisher. Kalamazoo, MI: Studies in Iconography and Medieval Institute Publications, 2017.

Karkov, Catherine E. The Art of Anglo-Saxon England. Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2011.

Klinkhammer, K. J. Adolf von Essen und seine Werke: Der Rosenkranz in der geschichtlichen Situation seiner Entstehung und in seinem bleibenden Anliegen. Eine Quellenforschung. Frankfurter Theologische Studien 13. Frankfurt: Josef Knecht, 1972.

Lafontaine-Dosogne, Jacqueline. Iconographie de l’Enfance de la Vierge dans l’Empire Byzantin et en Occident, Vol. 2. Brussels: Royal Academy of Belgium, 1965.

Lampert, Lisa. “The Once and Future Jew: The Croxton ‘Play of the Sacrament’, Little Robert of Bury and Historical Memory.” Jewish History 15 (2001): 235–55.

Langmuir, Gavin. “The Knight’s Tale of Young Hugh of Lincoln.” Speculum 47, no. 3 (1972): 459–82.

— — —. Toward a Definition of Antisemitism. Rev.edn. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1990.

Madan, Falconer. A Summary Catalogue of Western Manuscripts in the Bodleian Library at Oxford, Vol. 4: Collections Received during the First Half of the 19th Century. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1897.

Martin, Dennis D. “Behind the Scene: The Carthusian Presence in Late Medieval Spirituality.” In Nicholas of Cusa and his Age: Intellect and Spirituality: Essays dedicated to the Memory of F. Edward Cranz, Thomas P. McTighe and Charles Trinkaus, ed. Thomas M. Izbicki and Christopher M. Bellitto. Leiden, Boston, and Cologne: Brill, 2002, 29–62.

McCulloh, John M. “Jewish Ritual Murder: William of Norwich, Thomas of Monmouth, and the Early Dissemination of the Myth.” Speculum 72, no. 3 (1997): 698–740.

McLachlan, Elizabeth Parker. The Scriptorium of Bury St Edmunds in the Twelfth Century. New York: Garland, 1986.

Morgan, Nigel. Early Gothic Manuscripts, 1190–1250: A Survey of Manuscripts Illuminated in the British Isles, Vol. 4*.* London: Harvey Miller, 1982.

Nees, Lawrence. “Aspects of Antiquarianism in the Art of Bernward and its Contemporary Analogues.” In 1000 Jahre St Michael in Hildesheim: Kirche-Kloster-Stifter, ed. Gerhard Lutz and Angela Weyer. Petersberg: Michael Imhof Verlag, 2012, 153–70.

Nichols, Ann Eljenholm. The Early Art of Norfolk: A Subject List of Extant and Lost Art including Items Relevant to Early Drama. Early Drama, Art, and Music Series 7. Kalamazoo, MI: Medieval Institute Publications, 2002.

Noel, William. The Oxford Bible Pictures: Ms. W.106: The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore and the Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris. Baltimore and Luzern: The Walters Art Museum and Faksimile Verlag Luzern, 2004.

Pächt, Otto, and J. J. G. Alexander. Illuminated Manuscripts in the Bodleian Library Oxford, Vol. 3: British, Irish, and Icelandic Schools. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1973.

Rhodes, Jan. “The Rosary in Sixteenth-Century England.” Mount Carmel: A Quarterly Review of the Spiritual Life 31, no. 4 (1983): 4–17.

Rogers, Nicholas. “Fitzwilliam Museum MS3-1979: A Bury St Edmunds Book of Hours and the Origins of the Bury Style.” In England in the Fifteenth Century: Proceedings of the 1986 Harlaxton Symposium, ed. Daniel Williams. Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 1987, 229–43.

Rose, Emily. The Murder of William of Norwich: The Origins of the Blood Libel in Medieval Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.

Skey, Miriam Anne. “Herod the Great in Medieval European Drama.” Comparative Drama 13, no. 4 (1979–80): 330–64.

Solopova, Elizabeth*. Latin Liturgical Psalters in the Bodleian Library: A Select Catalogue*. Oxford: Bodleian Library, 2013.

Abbot Suger. On the Abbey Church of St.-Denis and its Art Treasures. Ed. and trans. Erwin Panofsky. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1946.

Thomas of Monmouth. The Life and Miracles of St William of Norwich. Ed. Augustus Jessopp and M. R. James. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1896.

Turner, Nancy K. “Reflecting a Heavenly Light: Gold and other Metals in Medieval and Renaissance Manuscript Illumination.” In Illuminating Manuscripts: Art, Science, Conservation, Meaning: Proceedings from the Conference at the Fitzwilliam Museum, 8–10 December 2016, ed. Stella Panayotova. Turnhout: Brepols, 2017, forthcoming.

Warner, George. Descriptive Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts in the Library of C. W. Dyson Perrins, D.C.L., F.S.A. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1920.

Widner, Michael. “Samson’s Touch and a Thin Red Line: Reading the Bodies of Saints and Jews in Bury St Edmunds.” Journal of English and Germanic Philology 3, no. 3 (2012): 339–59.

Winston, Ann. “Tracing the Origins of the Rosary: German Vernacular Texts.” Speculum 68, no. 3 (1993): 619–36.

Winston-Allen, Ann. Stories of the Rose: The Making of the Rosary in the Middle Ages. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1997.

Imprint

| Author | |

|---|---|

| Date | 29 June 2017 |

| Category | Article |

| Review status | Peer Reviewed (Double Blind) |

| License | Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) |

| Downloads | PDF format |

| Article DOI | https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-06/kcollins |

| Cite as | Collins, Kirsten. “Resonance and Reuse: The Fifteenth-Century Transformation of a Late Romanesque Vita Christi.” In British Art Studies: Invention and Imagination in British Art and Architecture, 600–1500 (Edited by Jessica Berenbeim and Sandy Heslop). London and New Haven: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art and Yale University Press, 2017. https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-06/kcollins. |