Women in Fur

Women in Fur: Empire, Power, and Play in a Victorian Photography Album

By Sarah Parsons

Abstract

The craze for carte-de-visite portraits in the early 1860s established photography as an intensely social practice. As cartes were bought, gifted, traded, archived, and displayed, they captured and created social networks. This article asks what we can learn about the social language and networks of early photography by turning instead to amateur photography, specifically women’s amateur efforts. In 1863, a group of elegant women gathered in a makeshift photography studio at Pitfour, a huge country house outside Aberdeen. Using curios from the estate as props, they created playful staged photographs. Two of the most striking ones involve a huge fur blanket inventively deployed as a symbol of sensuality and power. In their collaborative creation and circulation in various albums made by the participants, the photographs offer an early example of women’s use of photography to create and archive a shared language and experience. However, the presence of this huge bear fur at a Scottish estate is a reminder that the images, the albums, and the women who created them must also be considered in the wider imperial context. This article maps the social production and circulation of the Pitfour photographs in order to consider the tension between progressive early uses of photography and the often-repressive contexts that shaped that work. This article is accompanied by a digital facsimile, produced for British Art Studies by the Archive of Modern Conflict, of a photographic album assembled by Georgina Ferguson at Pitfour Estate in the 1860s. It appears in the Conclusion (fig. 33).

Introduction

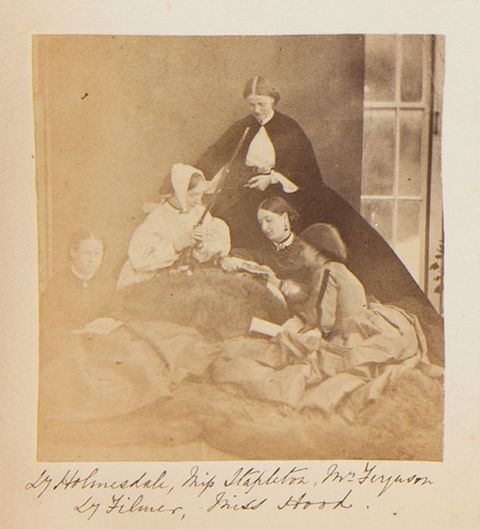

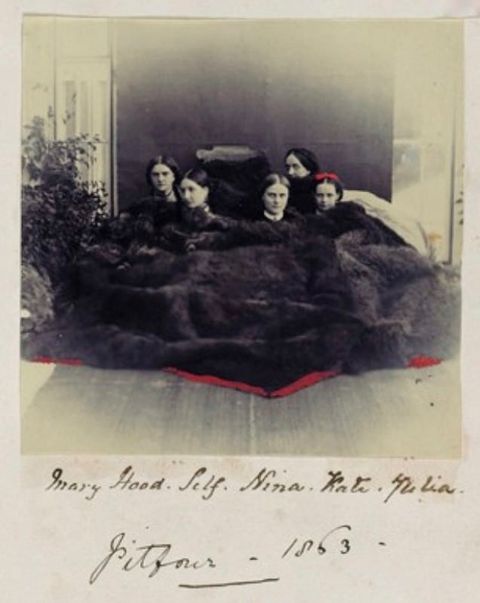

In a strikingly intimate photograph, five women gather on a floor under an enormous cascade of fur (fig. 1). The fur has been pulled up to their necks, or in one case over the bottom of her face, bodies nestled as close as their Victorian dresses would allow. The precarious arrangement of bodies is supported by a simple wooden chair at the centre. Not everyone looks comfortable and two women look off to the left. The youngest two women flank the group and they look dutifully, if warily, at the photographer. Only the woman in the centre stares confidently ahead, head held high. Another image of the same group has a more relaxed feel (fig. 2). Three of the women sit on the now splayed-out fur with books in hand while a fourth sits on the chair, white kerchief on her head and holding a long-barrelled gun resting on top of the fur draped across her lap. As in the first image, the figure at the centre is Nina Ferguson (b. 1842), who stands above the group looking down with a faint smile.

The unusual photographs were produced in 1863 in an early, makeshift home studio in a fifty-two-room mansion on a sprawling Scottish country estate owned by Nina’s in-laws, an estate her husband, George Arthur Ferguson, would soon inherit (fig. 3).1 Like most society families of the era, the Fergusons’ main residence was in London—a large house on Berkeley Square. Only when parliament was not sitting would the social activities of high society move to country estates. During the seasons when elegant visitors made their way to remote Pitfour, north of Aberdeen, the studio served as an invitation of sorts, a space to play. The production of these images and dozens of others in the Fergusons’ own domain means they would not have been subject to the time constraints or norms of a commercial studio or even the aesthetic and conceptual demands of art. The resulting Pitfour images were not intended for public display, but nor were they completely private. Instead, they were objects to be shared with participants as tokens of friendship, added to albums which would, in turn, be shared with family and friends.

1In their creation and circulation in albums, the Pitfour images offer an early example of photography as a collaborative, social, and creative activity. Many amateur and art photographers of the era, including Lewis Carroll and Julia Margaret Cameron, encouraged sitters to act out literary or historical scenes for the camera. In the fur images, Nina, her sister Mary Hood (b. 1846), and their friends Lady Julia Holmesdale (b. 1844), Miss Katie Stapleton, and Lady Mary Filmer (b. 1838) appear to be forging their own more inventive narratives using props drawn from imperial curios found at Pitfour. In the second fur image, the women mimic, and perhaps mock, appropriate Victorian pursuits for women: reading, caretaking, and instructing. Sequestered away in a country house studio, the women stage an intimate, playful performance for the camera that seems to undermine the limited roles assigned to them by gender and class. The fur photographs suggest efforts to not only push back against the expectations of Victorian femininity, but also to find new ways to represent the more repressed aspects of women’s lives. The sessions served as a leisure activity as well as a form of self-expression for the participants and the results appear to have been aimed at their wider social circle. The fur images and others from Pitfour sessions were archived in at least three separate albums created by women: Lady Filmer and Katie Stapleton, both pictured, and Nina’s sister-in-law Georgina Ferguson.

In one sense, these images and the albums that hold them are rich and novel evidence of these women’s creative and even progressive use of photography. At the same time, the images must be read within a wider imperial context. For instance, in a somewhat risqué connotation, the composition and tactile closeness of the women in the fur photographs might bring to mind John Lewis’s watercolours of harems in Egypt (fig. 4). The Pitfour photographs also make use of guns and the remains of animals killed as a result of an insatiable European market for fur. The studio itself was housed in a mansion on a vast estate funded in part by slavery. These facts are not, in themselves, unusual. A great deal of Victorian culture was facilitated by and made reference to signs of class privilege and empire. However, the Pitfour images provide a particularly rich context in which to consider the tension between progressive uses of photography, particularly by women, and the often-repressive contexts that shaped that work.

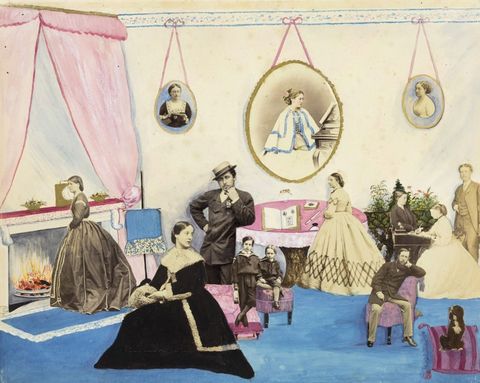

Photography at Pitfour

The Fergusons moved in the circles around Queen Victoria, whose fascination with photography and its myriad social uses is well established.2 Nina’s father, Alexander Hood, Viscount of Bridport, was the queen’s equerry at Windsor Palace and lived with his family at Cumberland Lodge on the estate. The queen had allowed Nina and George to marry at the chapel at Windsor Palace in 1860 and later Nina would go on to serve as a maid of the bedchamber. Lady Mary Filmer was closely associated with the Prince of Wales and is now celebrated for her elaborately adorned and socially adept photo-collages (fig. 5).3 Katie Stapleton’s identity is less clear, but a portrait of a Lady Stapleton appears along with the fur images and others from Pitfour in an album she created for the Duffs (Lord and Lady Fife). As a group, the participants involved in creating the fur photographs were well versed in the medium. It remains unclear exactly who took the photographs at Pitfour, but the women in these photographs were voracious commissioners and creative consumers of the medium.

2

The most complete collection of Pitfour images is found in an album created by Nina’s sister-in-law, Georgina Harriet Ferguson (b. 1829). Georgina did not marry and had no children of her own. She was close to her older sister Frances and, when their father died in 1867, they lived and travelled together until Frances’s death in 1874. In her foundational text on Victorian illustrated and collaged photographic albums, Elizabeth Siegel cautions that albums tempt biographical readings, but they are better understood “as a practice based in Victorian feminine society and visual culture”.4 Most albums of the 1860s were designed to map out the creator’s specific social world and to highlight her place within it. In contrast to many who collected and compiled albums in her day, Georgina’s has no images of British royalty, actors, or other celebrities (with the exception of a photograph of the Prince of Wales with a horse, but it is an amateur shot and was taken at Cumberland Lodge). As Patrizia Di Bello notes, “Upper-class society was a fairly close and interconnected community in the 1860s, and ideas about photographs and album making would have travelled easily across drawing rooms.”5 Within the higher echelons, the norm for albums in the 1860s was to steer clear of pre-made albums and to artfully arrange and adorn the images. This practice was exemplified by Lady Filmer, Princess Alexandra, and even by Lady Jocelyn, who also took her own photographs. Katie Stapleton’s album for the Fifes gestures at this expectation by cutting some of the pictures into interesting shapes and adding some pen decorations. Georgina’s album maps a social world, but it does so through often highly creative photographs—a focus on personal expression over convention. The album is a rich catalogue, a visual collection in large and small, of objects, places, and people who are woven together in a way that is more than a sum of its parts.

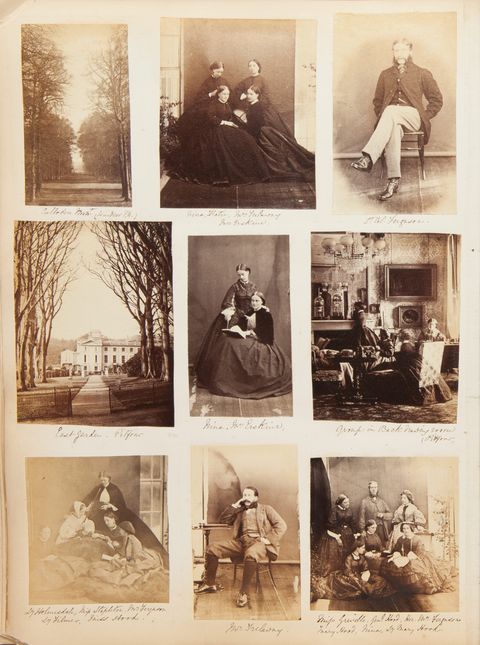

4The first half of Georgina’s album mostly comprises photographs taken either in the Pitfour home studio or on the estate (ca. 1862–1867) interspersed with commercial carte-de-visite portraits, professional landscape views, and amateur images from elsewhere that were gifted or purchased. The pages of the album comprise neat grids of carefully trimmed photographic prints, but the pages include none of the decorative flourishes of some Victorian albums, such as artistically trimmed photographs or decorative watercolour borders. It was not unusual for albums to include various photographic genres, from portraits to landscape. However, Georgina’s carefully composed pages almost always mix photographic genres. The page that includes the second playfully posed fur photograph sits alongside more traditional portraits, a landscape, an exterior view of the estate, and a rare interior image of a room at Pitfour (fig. 6). As a result, each page and the album as a whole suggest an integral and complex relationship between people and place. At the core is Pitfour, whose lavish buildings and grounds, servants and domesticated animals are catalogued in encyclopaedic detail, each photograph accompanied by a careful caption, but without dates or added commentary.6 The outdoor photographs made at Pitfour also include images of the familiar British social rituals that played out on those lands from hunting parties to picnics to choir performances.7 Most of the people pictured are members of Georgina’s family and guests of Pitfour, many of whom were also relations of some sort. The second half of Georgina’s album reflects her break from Pitfour after her father’s death and an inheritance that allowed the unmarried sisters to live independently. This post-1867 half of the album comprises largely commercial images purchased on a long European Grand Tour.

6

Georgina, Lady Filmer, and Katie Stapleton dutifully inscribed the names of sitters in the Pitfour images, but none identify the photographer or provide a clear indication of whether she or he was a skilled amateur or a hired professional. While easier and more flexible than either the calotype or daguerreotype, wet collodion plates still had to be laboriously sensitized just ahead of taking a photograph and then developed within ten minutes, necessitating a portable darkroom—if not a permanent one. Photography was a popular hobby among the Upper Ten Thousand of British society, but even those with interest and experience sometimes hired help.8 In late summer 1863, a month before the fur images were made, the London-based photographer Victor Albert Prout arrived in Aberdeenshire. Prout was hired by Katie Stapleton’s friends, Lord and Lady Fife (the Duffs), to document the annual Braemar Gathering of the Clans. The event was held at Mar Lodge, their country estate, and served as the first official visit to Scotland by the newly married and popular Prince and Princess of Wales. Prout’s task was to photograph a range of elaborate parties and social events including an evening of short plays and tableaux vivants, coordinated by Lewis Wingfield, a London theatre director.9 The performers in the tableaux vivants were amateurs drawn from prominent local families and Prout and Wingfield secured photographs by restaging the tableaux in a makeshift studio outdoors after the fact. Miss Stapleton appears in one of these images as a maid named Bobbin in a contemporary parlour comedy, “Popping the Question” looking particularly playful in a calf-length skirt with ankles exposed (fig. 7). Within the Pitfour circle of family and friends, photography was emerging as an important aspect of social activities and as a liminal space of possibility for Victorian women.

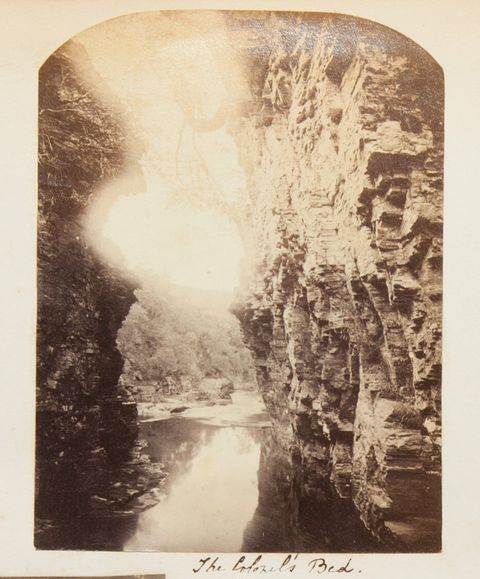

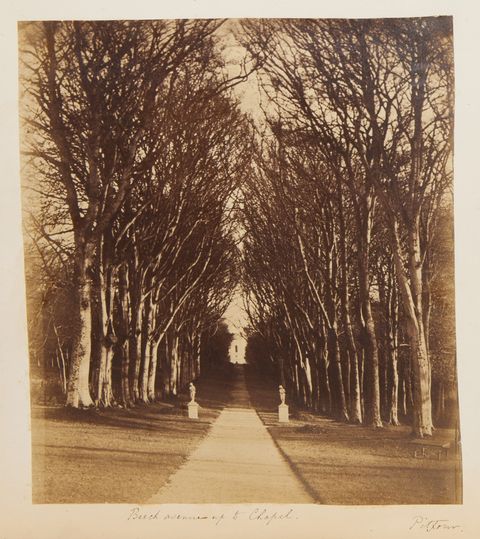

8Beyond Stapleton’s album, there are additional associations between Prout’s work in Scotland and photography at Pitfour. A panoramic photograph of Pitfour in Georgina’s album is similar in lighting and composition to those made by Prout. Knowing that the noted photographer Prout was nearby, the Fergusons may have seized the opportunity to have him make a panorama of their estate.10 Georgina’s album also includes several touristic landscape views of Scotland by Prout, including The Colonel’s Bed (fig. 8).11 However, it appears that Prout’s contribution to the Pitfour album was more in terms of ideas about photography than as author of the images, especially since the images at Pitfour date from 1862–1867 and cover a wide range of seasons, visits, and events. Among these, many are technically competent, but not quite professionally composed. In an image of the Chapel, we can see neither the woman in the foreground nor the chapel well and the fence is captured flat on instead of creating a diagonal sightline through the image as per aesthetic convention (fig. 9). Similarly, we cannot quite see the stables in the snow, but the chance to capture the effect of snow on so many objects in the garden would have been calling to anyone onsite with a camera (fig. 10). A number of the landscape views in the Pitfour album suggest the photographer was honing their craft by looking at the work of professionals like Prout and Aberdeen’s own George Washington Wilson. The many images of the long tree-canopied roads at Pitfour echo the way Prout and Wilson often photographed through some kind of restricted space into light (fig. 11). Copying successful photographers was a popular means of learning both what was worth photographing and how to photograph. An obituary for Wilson suggested that his views were so famous that others would regularly try to place their tripods on the same spot.12 In a similar vein, Stapleton’s experience with Prout at Mar Lodge may have led her, a month later, to encourage her friends to create scenes for the camera at Pitfour.

10

As for who might have served as the amateur family photographer at Pitfour, Georgina and Frances, the unmarried sisters, are the most likely candidates. Nina’s husband and his father were away from Pitfour when a number of photographs were made. Nina’s husband served as a colonel with the British Grenadier Guards in Montreal from 1862–1864 and, when he was at Pitfour, he appeared in many of the images. Furthermore, when the contents of Pitfour were auctioned off in 1926 after his bankruptcy and death, no nineteenth-century photographic equipment was among more than 1,300 lots that included items from kitchen supplies to furniture to saddles. The Fergusons’ social circle included women photographers. Lady Frances (Fanny) Jocelyn was a close friend and Lady of Bedchamber to Queen Victoria and friend of Lady Filmer. Jocelyn took up photography in earnest after her husband died, exhibited her work as an amateur, was elected to the Royal Photographic Society in 1859, and gave the occupation of photographer on the 1861 census, despite being the widow of an Irish aristocrat.13 The Ferguson sisters had the time and scope to practise the craft, but it is Georgina who indicated a clear interest in the medium through her album. She appears in only one of the Pitfour images, a staid portrait in which her body is turned away from the camera and her face is rendered only in profile.14 Katie Stapleton includes this same portrait in her own album for the Duffs. Rather than embedding Georgina’s portrait with others as part of a social circle, Stapleton placed her on a page with two wintery landscapes images of Pitfour and two prints of devotional religious figures, suggesting her importance to the album may lie beyond the social (fig. 12).

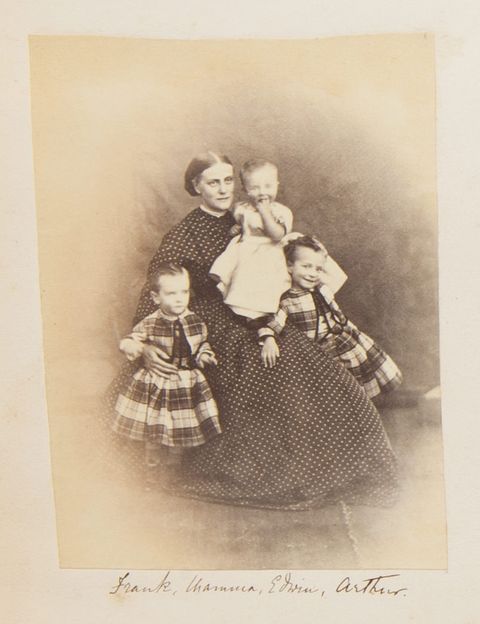

13Whoever took the fur photographs and others at Pitfour was an adaptable and patient practitioner. The outdoor photographs range from small to large groups, animals and children, in full sun and in more protected spots. The makeshift indoor studio would have allowed longer sessions in winter and somewhat more control over light conditions but was created with little more than a tarp mounted in a section of a windowed arcade along one length of the house. The Pitfour photographer must also have been comfortable working in a collaborative way or in taking direction. Nina’s consistent appearances among the Pitfour photographs, as well as what was recorded of her strong personality, suggest that she was likely one of the driving forces behind the use of the studio and outdoor photography. The Pitfour photographs begin shortly after her arrival in the family and she appears in them more than any other figure. The resulting photographs often dwell, as Anne Higonnet suggests of Victorian women’s albums, “on the places of feminine sociability” and even press at the constraining boundaries of Victorian femininity.15 Nina is pictured in traditional Victorian feminine activities: in keeping with the ideal of the “angel in the house”, she is frequently posed with her children but she is also pictured in the act of painting or absorbed in a photo album (figs. 13–15).

15

Power and play are consistent themes throughout other Pitfour photographs and in Georgina’s album. Although the photographs are casual, they are necessarily staged whether in the home studio or outside. The sense of performativity around gender roles and tools of power in the Pitfour photographs seems underlined when “active” masculine roles are recreated, often awkwardly, in the home studio. Unlike most men of his class, Lady Filmer’s husband, Edmund, was known to dislike hunting and refused to partake even to please the Prince of Wales.16 In the Pitfour studio, he poses seated on the floor with his rifle pointed at an unseen target (fig. 16). In many of the photographs, Nina performs traditional femininity, however, as in the fur photographs, there are significant moments where she seems to be playing with the boundaries. In one group portrait in the home studio, she is the only woman sitting at the table with men playing cards while their wives hover behind (fig. 17). In an outdoor group shot of a hunting party, Nina is one of few women and she holds a gun (fig. 18). As James Ryan notes “hunting was frequently characterized as an activity in which women were not fit to participate”.17 Nina may well have been a regular participant in these masculine and homosocial activities, but it is particularly notable that she made a point of being photographed doing so.

16

Photography, Fur, and Empire

In many of the Pitfour studio photographs, the sitters employ props, material objects chosen and deployed to help craft meaning within the image. Nina’s recent travels to Canada were likely the source of both the fur and its generative possibilities as a prop. In less than two years in Montreal, the Fergusons appear to have visited the portrait studio of William Notman on at least six occasions. The famed photographer had himself arrived from Scotland less than a decade earlier and was keenly attuned to creating a uniquely Canadian experience and souvenirs for sitters. Notman regularly incorporated fur rugs and throws as props.18 One of Notman’s most popular standard tourist portraits offered visitors the opportunity to be pictured outside in a winter sleigh under his studio sign which read “Photographer to the Queen”. George and Nina availed themselves of this set-up and the resulting image in the Pitfour album pictures Nina with a voluminous fur sleigh robe across her lap (fig. 19). Notman also photographed Baby George Arthur nestled in fur (fig. 20). The Fergusons even made use of Notman’s indoor “winter scenes” studio, where they posed with a sled and snowshoe with lambswool on the floor to simulate snow, sporting fashionable fur coats and hats made from a variety of animals (fig. 21).

18

Fur carries long-standing associations with animality, sensuality, and power. In her cultural history of fur, Julia Emberley argues that it is an even “more complex sign of symbolic power” than historians have acknowledged. Emberley notes that fur cannot be extricated from its imperial context and its circulation as a “multi layered object, sought after for both its desirability and profitability”.19 The historian John Richards posits that, for Canadian Indigenous peoples, the dangerous and difficult to hunt black bear was “the most respected of their prey animals”. This value pre-dates contact with Europeans and the high value placed on bearskins was further amplified by the trade in which animals become commodities.20 That is to say that fur has acquired many of its abstract associations as the object of centuries of imperial incursions. Fur was the primary driver for European interests in North America and the fur trade continued to significantly shape the development of Canada through the nineteenth century. Notman’s prolific use of furs at his studio was always more than a natural souvenir because fur was already a laden commodity. The fashion historian Jana Bara suggests that in 1860s Canada, fur signified the successful, if necessarily violent, pioneering spirit: “the shaggy fur overcoat became the symbol of many a man who had carved his empire out of the wilderness with his own two hands”.21 The gender studies scholar Chantal Nadeau extends this analysis arguing that fur served as a “as political marker of imperialist domination over defeated armies and populations”.22

19The associations of bearskin with both imperialism and nationalism were made more explicit in 1815. After the British victory at Waterloo, the Grenadier Guards adopted the French military fashion for bearskin hats, a fashion that requires an entire Canadian black or brown bear pelt for each hat. As other units added the bearskin to their uniforms, the British military became a major driver of the market for bear pelts while adding to the cultural association of bear fur and power. Beaver was the anchor and driver of the North American fur trade, but by the mid-nineteenth century, tens of thousands of bear pelts had been harvested and sold to Europe for men’s and women’s hats, coats, and collars, as well as rugs and robes. By the mid-nineteenth century, overhunting led to a drop in bear populations and scarcity in the market, further enhancing the desirability of bearskin as a commodity and a symbol.23 When the Grenadier Guards were sent to Quebec in 1861, their mission was to protect British holdings in Canada from American incursion during the American Civil War. The Grenadier Guards did not see military action in Canada, but when George Ferguson donned a bearskin in Montreal, he did so specifically in defence of the British Empire. The huge bear sleigh robe the Fergusons brought home made a fitting, if extravagant, souvenir of their time spent serving the empire, although the couple appear to have imported to Pitfour an entire Canadian sleigh in which to replay their colonial experience (fig. 22). When Nina and her family and friends brought the bear robe into the Pitfour studio, they necessarily brought along all this interrelated imperial and mercantile history, especially when the fur was paired with a gun. The long-barrelled rifle in Katie Stapleton’s hands connects the fur images to others that play with gendered associations of hunting and military service. However, by the 1860s, the traditional fur trade was dwindling and animal rights activism was taking shape in Britain.24 Fur still carried powerful symbolic resonance, but Nadeau traces a shift from the “manly fur culture” of the nineteenth century towards emerging cultural associations between fur and femininity.

23

The preponderance of maternal images of Nina in Georgina’s album raises suggestive supplementary possibilities for interpreting the fur photographs, especially when we circle back to Nina’s recent Canadian sojourn. The longhaired fur Notman used for baby George not only marked the image as a Canadian souvenir, but also served as a tool to conceal the adult required to hold the baby still enough to be photographed, a genre now referred to as “hidden mother” photos. In Montreal, Nina posed for Notman under the fur to make her baby visible to the camera. Back at Pitfour, Nina posed with her sister and friends under the fur, barely visible themselves except as a multi-headed creature, perhaps in allusion to the inescapably animalistic process of childbearing. Lady Filmer and Nina both gave birth to their first sons in 1862. By October 1863, Nina had delivered her second child and Lady Filmer’s baby son had died.25 The visceral, corporeal, and psychic effect of pregnancy, childbirth, and infant mortality would seem to invite some contemplation, even if the contours are not entirely legible to us now. In her analysis of Julia Margaret Cameron’s photographs on the theme of Madonnas, Carol Mavor turns to theorist Julia Kristeva’s 1977 essay “Stabat Mater”. Mavor draws on Kristeva’s text to try to make sense of the odd look and feel of Cameron’s Madonna pictures, to mine their tactile materiality as well as their sensuous representations of touch. Mavor argues that Cameron’s photographs explore how subjectivity is “violated by pregnancy and subverted by lactation and nurturance”.26 Kristeva writes forcefully and extensively about the pre-verbal space in which mother and child connect through touch, smell, and colour, but she also notes the difficulty in rendering and communicating these aspects of the maternal experience, despite how visceral and meaningful they may be. Ultimately, Mavor’s efforts to read Cameron through Kristeva offers a possible explanation for the fur photographs, both in terms of the desire to try to visually represent the maternal experience and the awkward result in which five women nestle together, under, or on a huge, musky, long-haired animal hide.

25Several years after the Pitfour image was produced, Leopold von Sacher-Masoch published his hugely successful and defining story, Venus in Fur (1870). Sacher-Masoch spawned the term masochist and his story, inspired by a Titian painting, cemented associations between fur, sensuality, and power. Drawing on the long-standing and imperially heightened symbolism of fur, Sacher-Masoch wants nothing more than for a woman to don the fur cloak of power and then to debase him. When the narrator is asked about his fondness for fur, he responds:

27furs have a stimulating effect on all highly organized natures … It is a physical stimulus which sets you tingling, and no one can wholly escape it … The torrid zone produces more passionate characters, a heated atmosphere stimulation … That is my explanation of the symbolic meaning which fur has acquired as the attribute of power and beauty.27

Lady Filmer’s version of the women under the fur blanket seems to point to this more sensual reading of the first fur photograph in her album. The bottom edge of the robe in her copy has been trimmed in bright red paint, an anointment she also adds to the hair bow on the teen, newly-wed Lady Holmesdale (fig. 23).28 This addition gestures to a more visceral and possibly erotic connotation for fur, which was used in the Victorian era to create merkins—pubic wigs used mainly by prostitutes. Many years later, Freud would codify this connection between fur and pubic hair in the Interpretation of Dreams: “the male dream of sexual excitement makes the dreamer find in the street … The clarinette and tobacco pipe represent the approximate shape of the male sex organ, while the fur represents the pubic hair”.29

28While the specific referents remain opaque, the women used this photography session in the Pitfour studio to engage in coded visual play around power, sensuality, and perhaps maternity—topics that occupied a complicated and even taboo place among upper-class Victorian women. In this sense, we might connect Nina and the other subjects to the Countess Castiglione, who commissioned an elaborate and subversive series of self-portraits from Pierre-Louis Pierson’s Parisian studio. As Abigail Solomon-Godeau notes, “women have rarely been the authors of their own representations, either as makers or models. Prior to the twentieth century there are a few exceptions and letters, fewer in the visual arts, and virtually none in photography.”30 Although there may be few comparative examples of individual women creating their own self-representation, the Pitfour photographs fit within a slightly wider category. Cameron’s Madonnas and Clementina Hawarden’s often playful and sometimes erotically charged images of her adolescent daughters remind us that groups of women in varying power relationships were using photography to explore new visual representations.31 Like Castiglione’s self-portraits, the fur photographs necessarily read as ambiguous oddities. However, Solomon-Godeau argues that “the singularity of the countess’s photographs intersects with the problem of feminine self-representation”.32 There is no traditional iconography for the representation of women’s experience of childbirth, new motherhood, and sexuality. Within this context, the fur images suggest a sustained and collective desire to devise and capture a shared, even modern, visual language of female power.

30Album of Empire

The visual language of female power that Nina, Georgina, and the others explored through photography was frequently incisive and inventive, but it was not intersectional. In her ground-breaking text on Victorian women’s albums, Di Bello was careful to draw attention to the scope of creativity accessible by class and her insights are certainly relevant to Pitfour:

33women like Lady Filmer were less restricted by prescriptive feminine ideas than middle-class women, and never expected to confine their lives to the care of husband and children, as women from the upper classes would usually be involved in managing estate business, and domestic staff and accounts.33

This freedom and the exciting visual work it produced enable us to write rich histories of Victorian women’s engagement with photography around women like Lady Filmer, Julia Margaret Cameron, Clementina Hawarden, and even the critic Lady Eastlake. What often remains occluded is the extent to which their class privilege was founded on or enhanced by the spoils of empire.

The photographs of imperial travels and keepsakes, like the fur robe, are only the most noticeable of the many ways Pitfour and its inhabitants were shaped by empire. Georgina’s grandfather helped create his family’s fortunes in Trinidad and Tobago leading to a post as Lieutenant-Governor of Tobago by the time he was in his early thirties (he was known as the governor to distinguish him from the other Lairds of Pitfour also named George). In the late eighteenth century, the governor was one of the island’s largest landowners and his vast sugar plantations made him a fortune through slave labour. At the end of his life, he moved back to Scotland and split his time between Edinburgh and Pitfour where, along with his brother, he used those profits to expand and build up the Pitfour estate. The governor never married, but he had fathered a son and daughter with a woman in Edinburgh and openly acknowledged them in his 1820 will in which he passed his vast estate to his illegitimate son. The heir was Georgina’s father, known as the Admiral, in light of his military career.34 At that time, his property included about 30,000 acres of land acquired over many years to create the Pitfour estate as well as the West Indian sugar plantations and slaves. By the time the Admiral became the fifth Lord Pitfour in 1820 at the age of 31, he was already in significant debt. Over his lifetime, he did an impressive job of further eroding the wealth built up by the four Lairds who preceded him through a combination of high living, gambling, and constant and elaborate building activity at Pitfour. After inheriting the estate and its vast fortune in 1820, Georgina’s father completely reworked the mansion house adding, as one local historian described it, “an imposing entrance above which was built a large Studio, with glass frontage, which housed a number of pieces of sculpture” (see fig. 3).35 In addition to the usual outbuildings such as the stables and chapel, he built an engineered race course running for miles through the grounds, an observatory, a riding school that could double as a ballroom, multiple lakes stocked with fish, fountains, and even a scaled-down replica of a Greek temple where he is said to have kept alligators (fig. 24).36

34

The only significant sources of income the Admiral added to his household came through marriage and the sale of people and land. His first wife was a wealthy heiress from Hereford whose father had provided an annual annuity as part of her dowry. After she died giving birth to their first daughter, the Admiral married Georgina’s mother, Elizabeth, who also brought significant wealth to Pitfour. The Admiral sought out further compensation in anticipation of the abolition of slavery. In May 1836, he received £5,724 when the British government settled his claim regarding 299 slaves in Tobago.37 The Tobago estate was not profitable without slavery and Georgina’s father, and later her brother, let it fall to ruin before it was sold in the 1870s. At his death in 1867, the Admiral left his son, Nina’s husband George, with £250,000 in debts against the property and little in the way of skill or temperament to turn the tide. Pitfour would eventually fall to ruin as well.

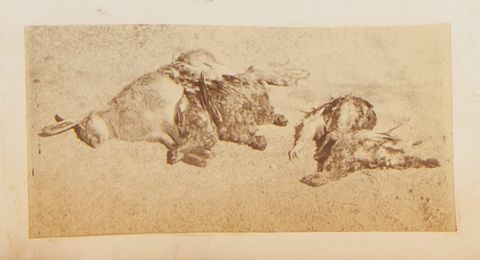

37There are no photographs of the West Indies in Georgina’s album. However, Edward Said’s method of “contrapunctual reading” suggests the importance of understanding British culture through the structural lens of empire.38 In this framework, the Ferguson album serves as a transatlantic photographic representation of the after-effect of sugar and slavery. It serves as a catalogue of the spoils of empire well beyond the fur robe. While the album’s landscape views of the estate strive for aesthetic effect, they also serve as an extensive record of the family’s land holdings. The photographs that picture sport and social activities over top of these lands remind us that owning land is an entitlement to do as one wishes in that place. At Pitfour, as on many Victorian British estates, that meant exerting power on a regular basis through hunting and fishing. Georgina’s album archives these acts by including not just pictures of hunting parties, but also of their bounty including photographs of a dead fox, rabbit, and birds, and an image of two male guests reclining with deer carcasses (figs. 25–27).

38

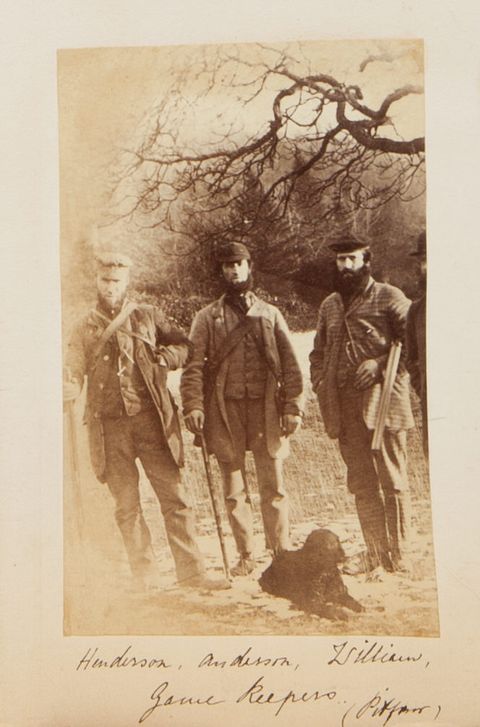

In her analysis of photography post-slavery in nineteenth-century Jamaica, Krista Thompson traces the prevalence of images best described as indulging in a touristic enjoyment of labour. She notes that these photographs recast hard physical labour as beatific, a perspective made possible by the time and space land owners and visitors had to observe this labour.39 Across the Atlantic, the Ferguson album also presents labour in a similar light. The local Aberdeenshire historian Duncan Harley estimates that in the mid-nineteenth century, Pitfour must have required more than 100 employees, in addition to the hundreds of tenants farming the land. Georgina’s album includes a number of photographs of individual workers, although never the scale of support that must have been used. In some images, they are abstract figures who form part of the landscape such as the single groundskeeper basked in light as he works along the road towards the Chapel or the figure working in snow (Figs 28 and 29). Under both these images, Georgina has inscribed the location on the estate but not the name of the worker. However, more specialized labourers are individualized and identified in the album. Keepers pose with their gear and rough clothes in the studio or with hunting parties (figs. 30 and 18). Nannies stand with the children and their donkey, Solomon, in the gardens (fig. 31). Workers are either pictured as part of the landscape or framed as part of the family circle. Nina poses in front of the chapel with the choir, presumably composed of the staff and tenants (fig. 32). Representing hired labour photographically, as either aesthetically pleasing or within the leisure activity of posing for the camera, whitewashes the vast scale of labour required and the source of the wealth so lavishly mapped in the album. The former Tobago plantation run by enslaved labour is part of the missing memory that explains and historicizes this Pitfour album and the family story it tells.

39

Like the images of labour, the fur photographs point back to empire, resource extraction, and hubristic efforts to display mastery over nature. As extravagant as the fur robe might have been outside of the frigid and long Quebec winters, the colonial bounty that appears in the Pitfour photographs was just a tiny fraction of the trophies found at the estate. The “curios” section of the 1926 Pitfour sale catalogue includes not just the Canadian souvenirs seen in the album, but also a stuffed alligator, armadillo, snakes, lizards, rhinoceros’ horns, twelve sets of multiple mounted deer horns, at least twelve cases of stuffed birds, along with dozens of unidentified mounted heads and horns. The weapons used to arrest these animals were also on display. There were dozens of African spears and shields, swords, “native” arrows and spears, Turkish knives, guns, and “aboriginal” weapons. Beyond the time in Montreal and regular winter trips to the south of France, there is little evidence that the Fergusons travelled, which renders this violent display of imperial might entirely performative. In turn, the house décor provides an even darker frame for the deployment of the fur as a symbol of power in the studio photographs. At Pitfour, domesticated animals were under control, as the photographs of the children’s donkey and Captain Byng’s dog attest, and wild animals were trophies of power.

From the giant fur to the enormous scale of the mansion and the estate, the Pitfour photographs provide lasting evidence of voracious consumption on the local level. In turn, the documentation and even celebration of voracious consumption in the photographs suggest how the decisions seen at Pitfour echoed across the Atlantic. Almost all the wooden furniture at Pitfour—enormous wardrobes, dressers, washstands—were made of mahogany. Jamaica was the source of most of the nineteenth-century mahogany brought to Britain—a trade that decimated the mahogany forests by the end of the nineteenth century. In both Tobago and Scotland, Georgina’s family sucked all the capital they could from their lands. When the other inhabitants called for a fairer share of the bounty, whether they were enslaved peoples in Tobago or the tenants on the Scottish estate, the Fergusons, like so many in power, never shifted course from extractivism to find a sustainable solution in a new economic framework. In Tobago, they took the government handout for the sale of their slaves, did not reinvest in the estate, and eventually abandoned it completely. As their debts grew and lease rates fell in Scotland, they just sold off the land to sustain their lifestyle but not to pay down their debts. The mansion house was destroyed shortly after the 1926 contents sale and, according to local lore, the stones were transported to Aberdeen to construct a housing estate.40 After 30,000 acres and a 52-room stone mansion, the most tangible surviving records of the Ferguson family legacy are the thin albumen print photographs lodged in women’s albums. Far from being a sideline observer to these destructive trends, Nina’s gambling debts are said to have led her to direct estate staff to clear-cut an entire small forest at Pitfour in order to sell the timber. Georgina likely had little say in decisions about Pitfour and its rapidly diminishing fortunes, but she lived there in season until her father died and then she received an annuity from the estate that enabled her to live a long, comfortable, and independent life. Her album likely passed through the family in the twentieth century before being acquired by the Archive of Modern Conflict at auction.

40Conclusion

The Pitfour photographs provide an invitation to weave together these seemingly disparate histories and places (fig. 33). Their production and circulation can enrich and complicate our understanding of women’s engagement with photography in mid-nineteenth century Britain.41 As the fur photographs demonstrate, domestic studios offered a space for creative play that, in turn, catalysed and documented complex relationships between people, objects, and places. Furthermore, the archiving practices of Georgina, Lady Filmer, and Katie Stapleton served as efforts to assert power and authorship and to articulate the relationship between a modern sense of self and wider society. In this sense, the Pitfour photographs foreshadow the use of the handheld camera at the end of the nineteenth century, the photo booth of the mid-twentieth century, and eventually social media. The challenge now is to develop our understanding and appreciation of these photographs and their collection into albums in ways that are cognisant of their global, imperial formation.

41Acknowledgements

This research would not have been possible without the kind assistance and generous insights of Lizzie Powell and Timothy Prus at the Archive of Modern Conflict in London. In Scotland, Judith Legg in the Local Studies Collection of the Aberdeenshire libraries and Jan Smith in Special Collections at the University of Aberdeen helped me locate what remains of the Pitfour estate and Ferguson family legacies. I would also like to extend my thanks to the anonymous reviewers and editors of British Art Studies, whose suggestions significantly strengthened this article.

About the author

-

Sarah Parsons is Associate Professor and Chair of the Department of Visual Art and Art History at York University, Toronto. Her research focuses on gender, race, and ethics in relation to photography. Most recently, Parsons is the author of “Site of Ongoing Struggle: Race and Gender in Studies of Photography”, in Gil Pasternak (ed.), Handbook of Photography Studies (Bloomsbury, 2020), editor of Photography after Photography: Gender, Genre and History (Duke University Press, 2017) and co-editor of the journal, Photography and Culture. Her current research focuses on the interconnected early histories of privacy and photography and is funded by a grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

Footnotes

-

1

Lady Filmer dates the image to October 1863. Although Nina and George Ferguson were posted with the Grenadier Guards in Montreal from 1862–1864, it seems as though at least Nina returned to Pitfour in the spring of 1863. Georgina’s album includes a portrait dated 1863 taken in the Pitfour studio of Nina with a very young baby Frank who was born in Montreal in June 1863 (see fig. 13). ↩︎

-

2

See Anonymous, The Private Life of the Queen by a Member of her Household (New York: D. Appleton & Co, 1897), 119. In the tell-all, published shortly before Queen Victoria’s death, her purported former staff member reports the queen’s insistence on being photographed in every activity from sitting in a favourite chair to eating outside. He or she also reports on the queen’s rather quirky predilection for having every possession in her homes photographed and set in albums, albums she is said to have revisited often. This activity was centred at Windsor Castle, where her main photographic studio and developing rooms were located, but also extended to Balmoral. ↩︎

-

3

See Patrizia Di Bello, Women’s Albums and Photography in Victorian England: Ladies, Mothers and Flirts (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2007), especially Chapter 5. See also Geoffrey Batchen, Photography’s Objects (Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico, 1995), and Elizabeth Siegel et al. Playing with Pictures: The Art of Victorian Photocollage (Chicago, IL: Art Institute of Chicago, 2009). ↩︎

-

4

Siegel, Playing with Pictures, 22. Martha Langford has also argued that photographic albums are closely aligned with oral traditions of storytelling. See Martha Langford, Suspended Conversations: The Afterlife of Memory in Photographic Albums (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2001). ↩︎

-

5

Di Bello, Women’s Albums and Photography in Victorian England, 117. ↩︎

-

6

Christopher Simon Sykes’ survey of British country house photography suggests the types and range of photographs taken at Pitfour were entirely in keeping with the norms of the day. These norms were stoked by the tight social and family connections between the inhabitants of such homes and the regular circulation of people, images, and albums. See Christopher Simon Sykes, Country House Camera (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1980), 17–19. ↩︎

-

7

Beginning in the mid-1850s, the queen used photography to document the buildings, grounds, and vistas of her estates including Windsor Castle and Balmoral. See Anne M. Lyden et al., A Royal Passion: Queen Victoria and Photography. (Los Angeles, CA: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2014). ↩︎

-

8

Lord and Lady Kinnaird of the Roissi Priory, Scotland, became interested in photography in its earliest phase, experimenting with the help of scientifically inclined friends with modest success. In 1861, they hired the photographer Thomas Cummings for what was likely a season of house parties. In their history of Scottish photography, Sara Stevenson and Alison Morrison-Low report that when Cummings accepted the Kinnaird’s offer, he stipulated his “charge for 26 working days would be 25 pounds” with the employers providing all the chemicals. See Sara Stevenson and Alison D. Morrison-Low, Scottish Photography: The First Thirty Years (Glasgow: National Museum of Scotland, 2015), 186. Queen Victoria and Prince Albert instructed their sons’ tutor, Dr Ernest Becker, to learn photography and to oversee photographic activities for them and to step in as a photographer when needed. ↩︎

-

9

See Marta Weiss, “The Page as Stage”, in Elizabeth Siegel, Playing with Pictures: The Art of Victorian Photocollage (Chicago, IL: Art Institute of Chicago, 2009), 37. ↩︎

-

10

Joan Osmond indicates that Prout received only one other commission from his work at Mar Lodge and does not mention Pitfour, but she acknowledges that documentation of Prout’s work is limited. See Joan Osmond, Victor Albert Prout: A Mid-Victorian Photographer (1835–1877) (Essex: J&J Osmond, 2013). ↩︎

-

11

The image in Georgina’s album appears to be one half of a stereograph given the small size and curved upper corners. Prout not only adapted a camera to create panoramic images but he also converted a boat into a darkroom in order to produce a handsome book of landscape scenes taken from the Thames. ↩︎

-

12

“Obituary: George Washington Wilson”, British Journal of Photography 40 (17 March 1893): 165–166. ↩︎

-

13

Isobel Crombie, “The Work and Life of Viscountess Frances Jocelyn: Private Lives”, History of Photography 22, no. 1 (March 1998): 40–51. ↩︎

-

14

Lest we wonder why Georgina would not have exhibited or otherwise connected her name to these photographs, the experience of “The Ladies Nevill” may have given her pause. Henrietta, Caroline, and Augusta made portraits of their aristocratic family. In the 1854 exhibition of the Photographic Society in London, the sisters exhibited jointly and must have been stung by the review in the Athenaeum, which sniped that their portraits “report to us the improved employment of their leisure by some members of the aristocracy of the present day”. Quoted in Grace Seiberling and Carolyn Bloore, Amateurs, Photography, and the Mid-Victorian Imagination (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1986), 139. ↩︎

-

15

Anne Higonnet, “Secluded Vision: Images of Feminine Experience in Nineteenth-Century Europe”, Radical History Review 38 (1987), 25. See also Carol Mavor, Pleasures Taken: Performances of Sexuality and Loss in Victorian Photographs (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1995) particularly the chapter on Julia Margaret Cameron, at 43–70. ↩︎

-

16

See Patrizia Di Bello, “Photocollage, Fun, and Flirtations”, in Elizabeth Siegel, Playing with Pictures: The Art of Victorian Photocollage (Chicago, IL: Art Institute of Chicago, 2009), 49–62. ↩︎

-

17

James R. Ryan, Picturing Empire: Photography and the Visualization of the British Empire (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1997), 110. ↩︎

-

18

See Jana Bara, “Cradled in Furs: Winter Fashions in Montreal in the 1860s”, Dress 16 (1990), 40; and Anthony W. Lee’s discussion of the relationship between empire and Notman’s staged hunting photographs in The Global Flows of Early Scottish Photography: Encounters in Scotland, Canada, and China (Montreal: Queen’s-McGill University Press, 2019), 144–160. ↩︎

-

19

Julia Emberley, “The Libidinal Politics of Fur”, University of Toronto Quarterly 65, no. 2 (1996), 438. ↩︎

-

20

John F. Richards. The World Hunt: An Environmental History of the Commodification of Animals (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2014), 9. ↩︎

-

21

Bara, “Cradled in Furs”, 41. For a discussion of the way nineteenth-century capitalism and colonialism changed human–animal relations, see John Berger, “Why Look at Animals?” About Looking (London: Writers and Readers, 1980), 1–26. ↩︎

-

22

Chantal Nadeau, Fur Nation: From the Beaver to Brigitte Bardot (London: Routledge, 2001), 36. ↩︎

-

23

Nadeau, Fur Nation, 49–50. ↩︎

-

24

For an analysis of the important role visual images played in this movement, see J. Keri Cronin, Art for Animals: Visual Culture and Animal Advocacy, 1870–1914 (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2018). ↩︎

-

25

Edmund Beversham Filmer was born on 9 August 1862 and died in February 1863. The Filmers remained childless until 1869. ↩︎

-

26

Mavor, Pleasures Taken, 61. ↩︎

-

27

Leopold Von Sacher-Masoch, Women in Furs (1870). Digital version produced by Avinash Kothare, Tom Allen, Tiffany Vergon, Charles Aldarondo, Charles Franks, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team: (http://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/6852/pg6852-images.html)[http://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/6852/pg6852-images.html]. ↩︎

-

28

Mary Filmer, “My Book”, Harvard University Museums, P1982.359. See Di Bello, Women’s Albums and Photography in Victorian England. ↩︎

-

29

Sigmund Freud, Interpretation of Dreams (London: G. Allen & Unwin, 1922), 72. ↩︎

-

30

Abigail Solomon-Godeau, “The Legs of the Countess”, October 39 (1986), 72. ↩︎

-

31

See Carol Mavor, Becoming: The Photographs of Clementina, Viscountess Hawarden (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1999). ↩︎

-

32

Solomon-Godeau, “The Legs of the Countess”, 72. ↩︎

-

33

Di Bello, Women’s Albums and Photography in Victorian England, 125. ↩︎

-

34

In 2008, it was estimated that massive transfer of wealth to Georgina’s father in 1820 was equivalent to about £30 million in modern terms. A.R. Buchan and Buchan Field Club, Pitfour: “The Blenheim of the North” (Peterhead: Buchan Field Club, 2008). ↩︎

-

35

See J. Wilson Smith, Pictures of Pitfour: Being a History of the Fergusons, Lairds of Pitfour. 4 vols, unpublished manuscript, 1942, Aberdeen Library. According to Wilson Smith, Georgina’s father built the studio and some of the supporting columns of wood rather than iron. As a result, they rotted away by the end of the century, contributing to the miserable state of the house which was rendered uninhabitable by the early twentieth century. ↩︎

-

36

Duncan Harley, “Pitfour: ‘The Blenheim of Buchan’. Part One: The Improvement”, Leopard Magazine (July–August 2016): 62–64. ↩︎

-

37

“George Ferguson”, Legacies of British Slave Ownership, University College London, (https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/person/view/27795)[https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/person/view/27795]. ↩︎

-

38

Edward Said, Culture and Imperialism (New York: Vintage Books, 1993), 66. ↩︎

-

39

Krista Thompson, “The Evidence of Things Not Photographed: Slavery and Historical Memory in the British West Indies”, Representations 113, no. 1 (2011), 53. See also Gillian Forrester, “Noel B. Livingston’s Gallery of Illustrious Jamaicans”, in Timothy Barringer and Wayne Modest (eds), Victorian Jamaica (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2018), 357–394. Forrester offers an insightful case study of use of portrait photography to map a colonial social structure. ↩︎

-

40

According the 1855 Scottish valuation rolls, Admiral George Ferguson owned approximately 320 parcels of land in the county of Aberdeen. By 1865, this had fallen to 140 parcels. By 1875, his son held 115 parcels. Some parcels shifted in size over this time but as a whole the rolls support the story told in other documents that the Fergusons divested significantly through the mid-nineteenth century. ↩︎

-

41

See Seiberling and Bloore, Amateurs, Photography, and the Mid-Victorian Imagination; and Siegel et al., Playing with Pictures. ↩︎

Bibliography

Anon. (1983) “Obituary: George Washington Wilson”. British Journal of Photography 40 (17 March): 165–166.

Anon. (1897) The Private Life of the Queen by a Member of her Household. New York: D. Appleton & Co.

Bara, J. (1990) “Cradled in Furs: Winter Fashions in Montreal in the 1860s”. Dress 16: 39–47.

Batchen, G. (1997) Photography’s Objects. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico.

Berger, J. (1980) “Why Look at Animals?” About Looking. London: Writers and Readers, 1–26.

Buchan, A.R. and Buchan Field Club (2008) Pitfour: “The Blenheim of the North”. Peterhead: Buchan Field Club.

Crombie, I. (1998) “The Work and Life of Viscountess Frances Jocelyn: Private Lives”. History of Photography 22, no. 1 (March): 40–51.

Cronin, J.K. (2018) Art for Animals: Visual Culture and Animal Advocacy, 1870–1914. University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press.

Di Bello, P. (2007) Women’s Albums and Photography in Victorian England: Ladies, Mothers and Flirts. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Di Bello, P. (2009) “Photocollage, Fun, and Flirtations”. In Elizabeth Siegel, Playing with Pictures: The Art of Victorian Photocollage. Chicago, IL: Art Institute of Chicago, 49–62.

Emberley, J. (1996) “The Libidinal Politics of Fur”. University of Toronto Quarterly 65, no. 2: 437–443.

Filmer, M. (n.d.) “My Book”. Harvard University Museums, P1982.359.

Forrester, G. (2018) “Noel B. Livingston’s Gallery of Illustrious Jamaicans”. In Timothy Barringer and Wayne Modest (eds), Victorian Jamaica. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 357–394.

Freud, S. (1922) Interpretation of Dreams. London: G. Allen & Unwin.

Harley, D. (2016) “Pitfour: ‘The Blenheim of Buchan’. Part One: The Improvement”. Leopard Magazine (July–August): 62–64.

Higonnet, A. (1987) “Secluded Vision: Images of Feminine Experience in Nineteenth-Century Europe”. Radical History Review 38: 17–36.

Langford, M. (2001) Suspended Conversations: The Afterlife of Memory in Photographic Albums. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Lee, A.W. (2019) The Global Flows of Early Scottish Photography: Encounters in Scotland, Canada, and China. Montreal: Queen’s-McGill University Press.

Lyden, A.M. et al. (2014) A Royal Passion: Queen Victoria and Photography. Los Angeles, CA: J. Paul Getty Museum.

Mavor, C. (1995) Pleasures Taken: Performances of Sexuality and Loss in Victorian Photographs. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Mavor, C. (1998) Becoming: The Photographs of Clementina, Viscountess Hawarden. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Nadeau, C. (2001) Fur Nation: From the Beaver to Brigitte Bardot. London: Routledge.

Osmond, J. (2013) Victor Albert Prout: A Mid-Victorian Photographer (1835–1877). Essex: J&J Osmond.

Reith and Anderson (1926) Catalogue of the Appointments of Pitfour House and Offices To be sold by auction on Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday 2nd, 3rd and 4th August, 1926. Aberdeen, Reith and Anderson. University of Aberdeen Special Collections.

Richards, J.F. (2014) The World Hunt: An Environmental History of the Commodification of Animals. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Ryan, J.R. (1997) Picturing Empire: Photography and the Visualisation of the British Empire. London: Reaktion Books.

Said, E. (1993) Culture and Imperialism. New York: Vintage Books.

Seiberling, G. and Bloore, C. (1986) Amateurs, Photography, and the Mid-Victorian Imagination. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Siegel, E. et al. (2009) Playing with Pictures: The Art of Victorian Photocollage. Chicago, IL: Art Institute of Chicago.

Smith, J.W. (1942) Pictures of Pitfour: Being a History of the Fergusons, Lairds of Pitfour. 4 vols, unpublished manuscript. Aberdeen Library.

Solomon-Godeau, A. (1986) “The Legs of the Countess”. October 39: 65–108.

Stevenson, S. and Morrison-Low, A.D. (2015) Scottish Photography: The First Thirty Years. Glasgow: National Museum of Scotland.

Sykes, C.S. (1980) Country House Camera. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

Thompson, K. (2011) “The Evidence of Things Not Photographed: Slavery and Historical Memory in the British West Indies”. Representations 113, no. 1: 39–71.

University College London (n.d.) “George Ferguson”, Legacies of British Slave Ownership, https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/person/view/27795.

Von Sacher-Masoch, L. (1870) Women in Furs. Digital version produced by Avinash Kothare, Tom Allen, Tiffany Vergon, Charles Aldarondo, Charles Franks, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team: http://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/6852/pg6852-images.html.

Weiss, M. (2009) “The Page as Stage”. In Elizabeth Siegel, Playing with Pictures: The Art of Victorian Photocollage. Chicago, IL: Art Institute of Chicago, 37–48.

Imprint

| Author | |

|---|---|

| Date | 30 November 2020 |

| Category | Article |

| Review status | Peer Reviewed (Double Blind) |

| License | Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) |

| Downloads | PDF format |

| Article DOI | https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-18/sparsons |

| Cite as | Parsons, Sarah. “Women in Fur: Empire, Power, and Play in a Victorian Photography Album.” In British Art Studies. London and New Haven: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art and Yale University Press, 2020. https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-18/sparsons. |